Despite enormous efforts, any correlation between “intelligence” and cognitive or physiological/anatomical properties of animal brains is still poorly understood because intelligence depends on multiple factors in parallel and not a single determinant (1). The study by Wang et al. (2) is both novel and intriguing, but we believe that the experimental results presented do not directly support their conclusion. Unfortunately, a mechanistic explanation of the correlation between intelligence and the spectral properties of biophotonic emission is not given in ref. 2, raising concerns that the observed correlation does not reflect a causal relationship but rather an accidental coincidence. Based on the reported spectral characteristics of the biophotonic emission (2) we calculated the coherence length (3), given as , with in Table 1.

Table 1.

The coherence length of biophotons from different species

| Species | λavg, nm | λmin, nm | λmax, nm | Δλ, nm | λavg2, nm2 | lc, μm |

| Bullfrog | 600.3 ± 0.82 | 522.1 ± 0.74 | 691.2 ± 0.98 | 169.1 | 360,360.09 | 2.131 |

| Mouse | 646.9 ± 1.53 | 591.1 ± 2.78 | 711.8 ± 0.0 | 120.7 | 418,479.61 | 3.467 |

| Chicken | 667.3 ± 2.00 | 607.4 ± 2.97 | 739.2 ± 1.96 | 131.8 | 445,289.29 | 3.378 |

| Pig | 682.3 ± 0.68 | 604.9 ± 1.29 | 777.7 ± 0.75 | 172.8 | 465,533.29 | 2.694 |

| Monkey | 696.9 ± 0.85 | 609.8 ± 1.76 | 806.1 ± 1.49 | 196.3 | 485,669.61 | 2.474 |

| Human | 714.6 ± 1.59 | 595.6 ± 2.13 | 865.3 ± 2.74 | 269.7 | 510,653.16 | 1.893 |

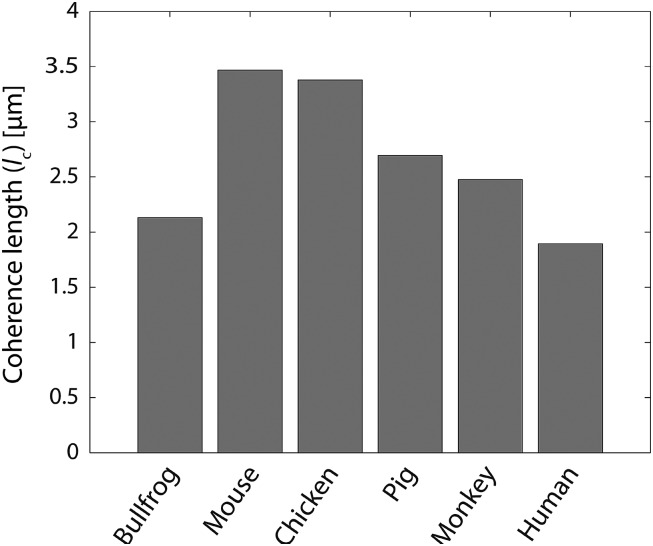

The obtained values for the coherence lengths show that the biophotons in the human brain have the shortest coherence length (i.e., 1.893 µm) among other species (Fig. 1). This is in contradiction to the expectation that the longest coherence length would be favorable for efficient information processing from which a higher degree of intelligence could emerge.

Fig. 1.

Species dependence of the coherence length values calculated according to the measurements reported by Wang et al. (2).

Interestingly, we have found a strong correlation (r = 0.86) between the values of λmax and the mass of each of the six species, indicating that intelligence may simply correlate with size. Additionally, glutamate-induced biophotonic emission does not necessarily correlate with the change in aerobic metabolism. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) can be produced by neural mitochondria as well as by the NADPH oxidase (4, 5). NADPH oxidase can produce ROS whether mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase is completely or incompletely blocked. Glutamate-induced ROS generation in neuronal presynaptic terminals is caused by the activation of the NADPH oxidase and nitric oxide synthases (6). NMDA receptor (NMDAR) activation by the glutamate increases NADPH oxidase activity, which is the key source of superoxide formation (O2·−) (4). We conclude that the glutamate-induced NMDAR activation and NADPH oxidase activity can lead to overproduction of ROS that causes an increase of biophoton in the brain (7), which seems at odds with the reasoning behind the claims made by Wang et al. (2). Finally, protein phosphatase (PP) 2A comprises a family of serine/threonine phosphatases that play roles in cell-cycle regulation, cell morphology and development, and specific signal transduction (8). However, okadaic acid can also inhibit the activity of PP1, PP2A, PP4, PP5, and PP6 phosphatases, which is an underappreciated fact (9). Hence, the claim that the inhibition of PP2A induces the hyperphosphorylation of MAP tau and interferes with the function of microtubules is highly speculative.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Dicke U, Roth G. Neuronal factors determining high intelligence. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2016;371(1685):20150180. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Z, Wang N, Li Z, Xiao F, Dai J. Human high intelligence is involved in spectral redshift of biophotonic activities in the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(31):8753–8758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1604855113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pedrotti FL, et al. Introduction to Optics. 3rd Ed Pearson; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brennan AM, et al. NADPH oxidase is the primary source of superoxide induced by NMDA receptor activation. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12(7):857–863. doi: 10.1038/nn.2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bókkon I, Antal I. Schizophrenia: Redox regulation and volume neurotransmission. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2011;9(2):289–300. doi: 10.2174/157015911795596504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alekseenko AV, Lemeshchenko VV, Pekun TG, Waseem TV, Fedorovich SV. Glutamate-induced free radical formation in rat brain synaptosomes is not dependent on intrasynaptosomal mitochondria membrane potential. Neurosci Lett. 2012;513(2):238–242. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Császár N, Scholkmann F, Salari V, Szőke H, Bókkon I. Phosphene perception is due to the ultra-weak photon emission produced in various parts of the visual system: Glutamate in the focus. Rev Neurosci. 2016;27(3):291–299. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2015-0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swingle M, Ni L, Honkanen RE. Small-molecule inhibitors of ser/thr protein phosphatases: Specificity, use and common forms of abuse. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;365:23–38. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-267-X:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Honkanen RE, Golden T. Regulators of serine/threonine protein phosphatases at the dawn of a clinical era? Curr Med Chem. 2002;9(22):2055–2075. doi: 10.2174/0929867023368836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]