Abstract

Understanding the processes that shaped contemporary pathogen populations in agricultural landscapes is quite important to define appropriate management strategies and to support crop improvement efforts. Here, we took advantage of an historical record to examine the adaptation pathway of the rice pathogen Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) in a semi-isolated environment represented in the Philippine archipelago. By comparing genomes of key Xoo groups we showed that modern populations derived from three Asian lineages. We also showed that diversification of virulence factors occurred within each lineage, most likely driven by host adaptation, and it was essential to shape contemporary pathogen races. This finding is particularly important because it expands our understanding of pathogen adaptation to modern agriculture.

The emergence of aggressive clones of plant pathogens is a common phenomenon that threatens disease management strategies in modern agriculture. When resistance sources are available, major-effect genes are usually introgressed into elite varieties and deployed in large cropping areas. Unintentionally, these interventions also shape pathogen population structure by selecting for underrepresented virulent clones1. In this scenario, capturing the genetic pool of the pathogen population becomes essential to monitor emerging clones and drive genetic improvement efforts. Recent advances in high-throughput sequencing technologies allow us to quickly characterize contemporary genetic diversity, and to investigate relevant questions such as i) the origin of local pathogen populations and the evolutionary forces driving population dynamics, ii) the composition of virulence factors, and iii) the association between genotype and disease output. More accurate pathogen information will contribute to the formulation of better monitoring strategies and reduction of the long-term risk of local disease epidemics.

Rice is considered a major source of calories for half of the world’s population. In Asia, where rice is a staple crop and where 90% of the global rice production comes from, a major economic constraint is the widespread occurrence of bacterial blight disease caused by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo). While genetic improvement is by far the most effective way to control disease epidemics in the field, yield losses in susceptible varieties can reach as much as 50% under highly conducive environments2. A number of resistance genes (Xa) have been described in wild and cultivated accessions but only a few have been actively used in breeding programs across Asia3. Resistance appears to be mediated by a diverse set of recessive as well as dominant genes4. Compared to other race-specific rice pathosystems, only a few Xa genes appear to encode NBS-LRR domains5. In fact, biochemical functions of known Xa gene products have been frequently assigned to other groups such as transcription factors, membrane transporters, or miRNA stability-related genes6.

Expanding blight lesions on leaves or whole plant wilting are typical disease symptoms resulting from Xoo colonization which obstructs xylem vessels7. To establish a successful interaction, Xoo relies on type III secretion system-mediated translocation of effector proteins into the host cell. These proteins facilitate a parasitic lifestyle by promoting nutrient uptake and modulating immune responses8. Although type III effectors are predicted to have a variety of biochemical mechanisms to target specific host functions9, at least two families show measurable contribution to pathogenesis. The first group can be recognized as type III-secreted, Xanthomonas outer proteins (Xop), and appears to suppress the plant’s innate immunity. For instance, deletion mutants of XopZ, XopN, XopQ, or XopX compromise pathogen virulence. These proteins appear to suppress the defense response induced by the enzymatic damage of the cell wall during Xoo infection10. Other effectors such as XopAA and XopY have been shown to interact with plant receptors from different immune signaling pathways11. The second group of proteins that have major contribution to virulence is also type III-secreted (and technically Xops) but is referred to specifically as transcription activator-like effectors (TALEs) because they induce the expression of specific host susceptibility genes (S) in order to create a favorable environment for the bacteria8. For instance, members of the SWEET sucrose-efflux transporter family were identified as targets of core TALEs across Asian and African Xoo populations12. In this context, increasing sucrose within xylem vessels appears to be an essential virulence function during the rice–Xoo interaction13. Another known target of TALE-mediated activation is the rice transcription machinery itself. Sugio et al.14 showed that two different TALEs modulate the expression of general transcription factors OsTFIIAγ1 and OsTFXI, suggesting that Xoo indirectly alters the expression of a number of other genes. In general terms, rice evolved to counter the TALE-mediated virulence mechanism e.g. by selecting mutations in the promoter of the S gene, by using suicide decoy genes know as executors, or by creating allelic versions of core transcription factors14,15.

Bacterial blight has been reported attacking traditional rice cultivars in the Philippine archipelago since the 1950s16. Since then, Xoo epidemics have been characterized in this country more than anywhere else in Asia. Several decades of field surveys and collection as well as further genotypic and phenotypic characterization produced a comprehensive record of emerging races under a diversified agro-ecosystem2,17,18. The Philippines is also considered as a historical battleground for testing modern high-yielding varieties during the green revolution. In fact, from 1970 to 2009 more than 134 varieties were released19. These varieties have quickly replaced native ecotypes in most parts of the country. This dramatic change in host genotype and its impact on pathogen population structure were showcased when broadly adopted varieties carrying Xa4 were quickly overcome by emerging Xoo populations2. In the current study, we took advantage of a unique historical record to characterize the genome composition of key Xoo races in the Philippines and to provide insight into the evolutionary forces shaping pathogen populations. We provide evidence suggesting that modern Xoo races were derived from at least three ancestral genetic lineages in Asia. The diversification of effector proteins is likely to explain phenotypic adaptation of Xoo to the local rice landscape.

Materials and Methods

Xoo database mining

We accessed 1,922 records of Xoo live cultures maintained in the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). The accessions were collected across different rice-growing areas in the Philippines between 1972 and 2012. We selected a total of 1,719 records that have consistent passport data and have retained race determination (Supplementary Table S1) assigned based on pathogenicity reactions on differential cultivars, as described in Mew et al.2. Based on these criteria, the Xoo population was categorized into 10 major races. Most of the strains with the PXO (X. oryzae from the Philippines) designation have been described before in a number of studies2,18.

Genome sequencing, assembly, annotation and SNP mining

We selected one representative strain for each of the 10 Xoo races present in the Philippines. The genome sequences of PXO8620 and PXO99A 21 were retrieved from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) while the remaining eight Xoo strains were sequenced using PacBio single molecule real-time (SMRT) technology. The bacterial DNA of overnight grown Xoo cultures (30 °C) were extracted and purified using the Easy-DNA kit (Invitrogen, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. For every strain, two SMRT libraries were sequenced through P6-C4 chemistry. De novo assembly was performed as described in Booher et al.20 using HGAP v.3 and the PBX toolkit. TALE-containing reads were assembled independently and parsed using the PBX toolkit20. Annotation of all the assembled genomes was done using the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (PGAP). The finished genomes were deposited in GenBank under project accession number PRJNA304675. A summary of the genome statistics of each strain can be found in Supplementary Table S2. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were obtained from the core whole-genome alignment using the parsnp program implemented in Harvest suite tools22. For most of the analysis we included the Korean Xoo strain KACC10331 (AE013598), the Japanese Xoo strain MAFF331018 (AP008229), the African Xoo strain AXO1947 (CP013666), and the X. oryzae pv. oryzicola (Xoc) strain BLS256 (CP003057) as out group. Core SNPs were annotated using TRAMS23.

Phylogenetic, recombination, and structure analysis

The phylogenetic relationship of Philippine Xoo strains was evaluated using core SNPs inferred through the maximum likelihood method implemented in RaxML24. The confidence of the maximum likelihood tree was estimated using 1000 bootstrap replicates determined by ASC_GTRGAMMA substitution model. Along with phylogenetic reconstruction, a network reconstruction analysis to detect recombination events was performed on the concatenated core SNPs using the Splits decomposition method implemented in SplitsTree425 with statistical validation using the pairwise homoplasy index (PHI) test of recombination. We applied BRATNextGen26 to calculate for recombinant segments in the core genome alignment using a hyperparameter alpha = 2 with 10 iterations. The convergence was assessed to be sufficient since changes in the hidden Markov model parameters were negligible over the last 70% of the iterations. The estimated significance of the recombinant segments was determined with a threshold of 5% using 100 permutations. The core SNP dataset on the 10 Xoo strains was subjected to Bayesian analysis using STRUCTURE27. We chose the admixture model and the correlated allele frequencies between populations as setting option. Five independent runs were performed for each population or K result ranging from 2 to 10. We used 100,000 Markov chain Monte Carlo iterations for each run, with the first half of the run considered as burn-in. To assess the optimal number of population (K), the program estimates the log probability of data Pr (X/K) for each K. POPHELPER28 R package was also used for comparison.

Comparative genomic and positive selection analyses

Whole genome alignment for structural variation was performed in MAUVE 2.3.129 using the progressiveMAUVE method with default parameters. The pan-genome and core genome were determined using GET_HOMOLOGUES30 package using the OCML and bidirectional best hit (BDBH) algorithm with sequences having an e-value of 1e-5, a coverage of at least 75%, and a minimum identity of 70%. The core genes were aligned using MUSCLE31. Dispensable genes were filtered for transposable element and phage-related genes. An estimation of the numbers of synonymous (Ks) and nonsynonymous (Ka) substitutions per site was used to assess the selection32. The assessment of the Ka/Ks ratio (ω) for Xoo genes was done using KaKs-Calculator 2.033. The Yn00 model32 was used for determining the statistically significant ω values. Comparison of TALE and Xop effector contents were computed using Jaccard similarity coefficient.

TALE and Xop analysis

Preliminary TALE classification was based on 80% identity at the repeat variable diresidues (RVDs). Xop classification was based on local alignments to entries of the Xanthomonas database (http://www.xanthomonas.org/). Trees based on alignments of repeat regions and DNA binding probabilities were obtained using DisTAL and FuncTAL, respectively34. Target predictions for TALE were made using Talvez35 with default parameters against the promoter region of the rice Nipponbare genome version MSU7 1 Kb upstream the translation start site. The top 200 targets for each TALE were kept, and prediction scores for each TALE were normalized against the highest score obtained. Multiple prediction scores for a gene by TALEs from the same strain were added to obtain strain level predictions. Haplotype diversity (Hd) for effector loci was estimated in DNASP36.

Pathogenicity tests

We phenotypically characterized 10 Xoo strains as described in Mew et al.2 with some modifications. Essentially two-day old cultures were suspended in demineralized sterile water and the inoculum concentration was adjusted to 108 CFU/ml. Forty five-day old plants were inoculated using the leaf clipping inoculation method2. Disease was assessed 14 days post inoculation by measuring lesion length in inoculated leaves. In particular, we determined the virulence spectrum of the 10 Xoo strains on 14 near-isogenic lines (NILs) carrying single resistance genes (Supplementary Table S3). A Jaccard similarity coefficient was calculated from a qualitative phenotype dataset with the following designations: 1 = resistant, 2 = moderately resistant, 3 = moderately susceptible, and 4 = susceptible.

Results and Discussion

A historic case of emerging Xoo races

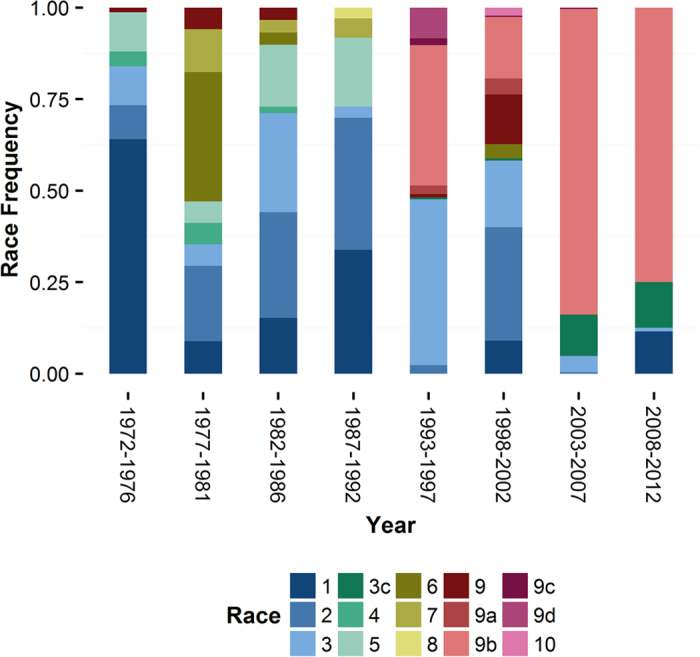

The emergence of novel pathogen populations is a common phenomenon in the agricultural landscape that can be associated with drastic events of selection37. To investigate the historical dynamics of Xoo races, we mined a well-characterized dataset spanning 40 years of bacterial blight collections in the Philippines. The database recorded 10 races and 5 derived subgroups collected between 1972 and 2012 (Supplementary Table S1). We plotted the time distribution of all major races to describe two major population shifts that coincide with the emergence of novel groups during the 70s and 90s (Fig. 1). In the first case, Race 2 replaced the prevalent type Race 1 in response to change in rice cultivars across the Philippines. The event was documented by Mew et al.2 who attributed the emergence of Race 2, a Xa4-compatible population, to the wide cultivation of modern varieties carrying this gene during the early 70s. The second case describes the emergence of Race 9b as the most prevalent group after the 1992 epidemics (Fig. 1). In contrast to what appears to drive the expansion of Race 2, it is highly unlikely that single resistance gene deployment could explain the expansion of Race 9b across the entire archipelago. Besides the apparent fitness of Race 9b, we speculate that changes in cropping patterns, fertilizer use, or environmental events may have also contributed to its expansion. To our knowledge, two major events may have played a role: 1) the eruption of the Pinatubo volcano in 1991 which might caused changes in the environmental conditions of the whole archipelago38 and 2) the sudden decrease in harvested area of the dominant variety IR64, which was estimated to be 40% in 1992 but less than 1% by 201219. This mining exercise helps us to contextualize our understanding of Xoo populations and to select representatives of key races for comparative genomics.

Figure 1. Frequency of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) races in the Philippine archipelago during a 40-year collection period (1972 to 2012).

Color blocks represent the different races described in the Xoo database. The number of Xoo entries that were collected in the following periods are: 1972–1976 = 75, 1977–1981 = 34, 1982–1986 = 59, 1986–1992 = 133, 1993–1997 = 861, 1998–2002 = 861, 2003–2007 = 237, and 2007–2012 = 104.

Xoo lineage split predates the colonization of the Philippine archipelago

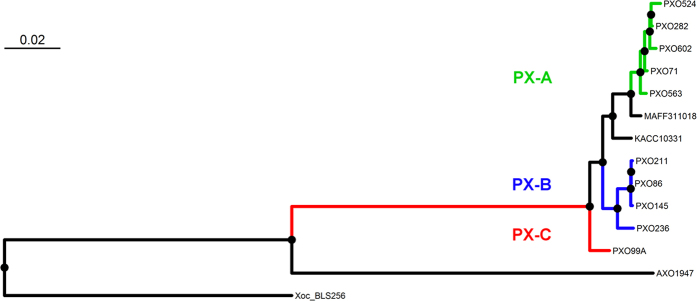

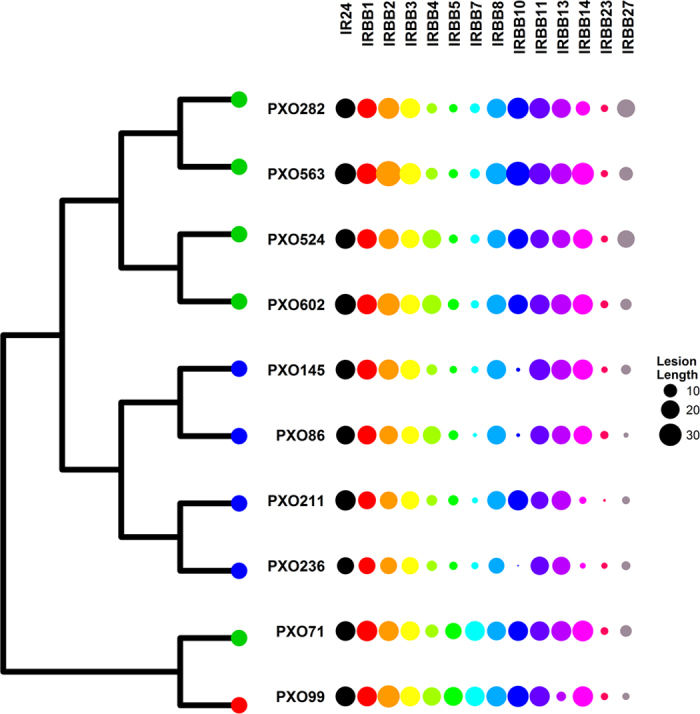

We obtained complete genome sequences for 10 major Xoo races collected in the Philippines between 1974 and 2006 (Supplementary Table S2). The assembled genomes (102-268X coverage range) represent key phenotypic groups isolated before (Races 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8) and after the 1992 epidemics (Races 3c, 9b, and 10). Using phylogenetic reconstruction (Fig. 2) and whole genome alignments (Supplementary Fig. S1) we identified three major lineages as Philippines Xanthomonas groups A, B and C (PX-A, PX-B, and PX-C). A genome-wide assessment of core SNPs (Fig. 2) clustered the strains PXO282, PXO602, PXO71, PXO524, and PXO563 (Races 1, 3c, 4, 9b, and 10, respectively) into lineage PX-A (green) and the strains PXO86, PXO236, PXO145, and PXO211 (Races 2, 5, 7, and 8, respectively) into lineage PX-B (blue). The strain PXO99A (Race 6) represents a unique genotype that was identified as lineage PX-C (red). Removing recombinant SNPs does not alter the phylogenetic signal of Fig. 2.

Figure 2. Phylogenetic relationships of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) strains from the Philippine archipelago using whole genome information.

Maximum likelihood phylogeny is based on 87,868 concatenated core SNPs. Each Philippine Xoo lineage is denoted in green = PX-A (PXO71, PXO282, PXO524, PXO563, and PXO602), blue = PX-B (PXO86, PXO211, PXO145), and red = PX-C (PXO99A). Black dots in the tree represent a bootstrap value >60. Information on the Japanese Xoo strain MAFF311018, the Korean Xoo strain KACC10331, the African Xoo strain AXO1947, and the Philippine Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzicola strain BLS256 was included.

Lineages were distinct from Xoo isolated from Africa and from Xoc. Interestingly, the Korean and Japanese strains grouped within the lineage PX-A (Fig. 2), which suggests that lineage separation predates the Xoo colonization of the Philippine archipelago. Previous studies suggest a putative ancestral population that derived into modern genetic groups in Asia 39,40. Most of these studies also linked members of these lineages with representative Asian groups. For instance, Adhikari et al.39 used two DNA repetitive probes on 308 strains to connect Philippine genotypes with at least three out of five Asian groups. More recently, Poulin et al.40 analyzed variable number tandem repeat diversity in 127 strains from 12 countries and found the same pattern of genetic distribution.

Whole genome alignment of the 10 Xoo strains reveals a series of insertions, deletions, and rearrangements resulting in 41 syntenic blocks (Supplementary Fig. S1). Structural variation is known to play a role in the diversification of Xoo and is also involved in the acquisition of important components like pathogenicity factors41. Interestingly, major events of genomic inversion followed similar patterns in members of lineages PX-A and PX-B. In particular, the genome structure within PX-A is highly conserved, suggesting that bottleneck events may be part of the recent evolutionary history of Xoo in the archipelago (Supplementary Fig. S1).

The population structure of Xoo, determined using a Bayesian algorithm according to the defined number of clusters that best fit the genetic diversity, corroborated the lineage designation. After five simulations, the number of populations has the highest likelihood when K is between 3 and 4 (Supplementary Fig. S2). Although sample size is relatively small for this type of analysis, our results are in line with previous analyses showing some level of population substructuring2,17. As reported previously21, the pattern of genetic variation found in the core genes of PXO99A was quite unique and unrelated to any native populations in the Philippines, indicating a recent colonization event. In fact, PXO99A was previously linked to Xoo genotypes isolated in Nepal and India21. Members of PX-A belong to races with broad distribution in the Philippines (Supplementary Table S1). With the exception of Race 2, most members of PX-B (Races 5, 7, and 8) belong to races restricted to a single mountainous region of central Luzon17. While Race 5 has been mostly isolated from traditional cultivars at high elevation, Races 7 and 8 have been found only in transitional zones17. Though further studies are under way to determine the presence of additional lineages, our data distinguish at least three lineages of Xoo in the archipelago. Whether PX-A and PX-B lineages are derived from ancestral Xoo populations in Asia or represent native Xoo populations from Philippines remains to be solved.

Recombination may have limited impact on shaping Xoo lineages

Recombination is one of the forces that create genetic variability and have a long-term effect on the evolution of bacteria42. To investigate whether major recombination events have shaped Xoo races in recent times, we estimated the overall contribution of mutation and recombination on the observed pattern of SNPs in the alignment. The inferred split decomposition analysis was consistent with the phylogenetic reconstruction assigning a 94.33% fit to the topology (Supplementary Fig. S3), suggesting that the impact of recombination on Xoo across Asia may be limited. Nevertheless, significant PHI values (p-value = 0.00) from 32,342 informative sites indicated some level of recombination occurring locally. To assess the distribution of recombination events within lineages PX-A and PX-B, we used the Bayesian Recombination Tracker (BRATNextGen) (Supplementary Fig. S4). Overall, we estimated that 61.11% of the 14,241 SNPs have been introduced by recombination. Similar to other Xanthomonas in which mutations and recombination appear to happen at relatively similar frequencies43,44, the ratio of recombination over point mutation (r/m) was calculated as 1.65 regardless of the exclusion or inclusion of mobile genetic elements (Table 1). Interestingly, recombinant SNPs were enriched in members of the PX-A lineage, which may explain the conflicting signal and reticulation pattern of this group as observed in Supplementary Fig. S3. Additionally, PX-A has twice the r/m ratio as PX-B (Table 1). These values are not as dramatic as estimates for sympatric populations of other plant pathogens45,46 even with the limited number of genomes analyzed. At this point we can speculate that recombination is an important source of variability in sympatric Xoo in the archipelago but still not strong enough to disrupt lineage signal and to prevent the formation of clonal populations in nature. A similar situation was reported by McCann et al.45 who described the emergence of Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae clonal lineages despite the fact that recombination persists within pathovars. Probably the strong host selection characterizing the Xoo–rice interaction is driving the evolution of the pathogens in nature and reducing the impact of gene conversion on phenotypic adaptation.

Table 1. Estimated ratio of recombination over point mutation (r/m) calculated for 10 Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae genomes including or excluding mobile genetic elements (MGE).

| Lineage | r/m with MGE | r/m without MGE |

|---|---|---|

| All* | 1.65 (m 4097, r 6765) | 1.64 (m 3960, r 6501) |

| PX-A | 3.99 (m 324, r 1294) | 3.88 (m 306, r 1189 |

| PX-B | 1.16 (m 440, r 514) | 0.937 (m 381, r 357) |

*All of the 10 Philippine strains.

Distribution of dispensable genes in Xoo lineages

The number of dispensable genes that are shared by more than one member strain is proportional to the functional diversity of a species. If environmental conditions change, these genes provide supplementary functions that may confer selective advantages47. We assumed that dispensable genes would tend to be shared by pathogen populations with similar adaptation histories. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the distribution of dispensable genes across Xoo samples from the archipelago. We first classified the 42,689 predicted ORFs into 5,516 orthologous gene clusters. We plotted 982 single-copy genes that were present in at least two strains and showed a lineage-specific distribution (Supplementary Fig. S5). All members of lineage PX-A and almost all members of PX-B appear to have similar sets of dispensable genes. The only exception was PXO86, which showed a slightly distinct array of genes compared to the rest of lineage PX-B (Supplementary Fig. S5). The presence/absence pattern in PXO99A (lineage PX-C) was unique as reported earlier20. Whether such a pattern was derived from a common ancestor or was driven by functional adaptation to the same environment is still unclear. In free-living bacteria like Escherichia coli, dispensable genes are clearly enriched in transposon-related elements48. A recent report showed that Tn3-like sequences play a key role in spreading a range of pathogenicity factors in the genus Xanthomonas49. Since Xoo retains a relatively large population of mobile elements21, we speculated that some of these sequences actually contribute to generating diversity within lineages. As expected, we found that genomes in the same lineage share similar transposases (Supplementary Fig. S5), which catalyze the movement of the transposons inside the genome. However, a number of strain-specific genes were also identified, accounting for 24.42% of the compared Xoo genomes, which suggests unique capabilities of gaining and losing genetic material among individual genomes. Overall, our data are consistent with the idea that members in the same lineage went through a similar adaptation process.

Distinct patterns of selection in different lineages of Xoo

The driving force behind adaptive evolution is the tendency of fitness alleles to be selected and to increase in the population50. Since positive selection may describe evolutionary histories, we characterized the selection pressures underlying Xoo populations on core and dispensable genes. Using a combined cutoff p-value of 95% on the alignments of 2,952 core genes, we found an average Ka/Ks ratio of 0.23. Interestingly, PX-A has significantly higher Ka/Ks ratios on average than PX-B when all the genes are compared together (Supplementary Fig. S6). This is in spite of the fact that both lineages retain similar proportions of synonymous and non-synonymous mutations (Supplementary Fig. S6). We identified 157 genes that showed signatures of positive selection in PX-A when compared to PX-B (Ka/Ks>1). To further understand the distribution of positive selection in PX-A and PX-B, we selected orthologous gene clusters that were present in both lineages. We observed the Ka/Ks ratio of 172 dispensable genes at 0.59. The comparison of the Ka/Ks ratio distribution of dispensable genes in both lineages showed a similar pattern as the distribution in core genes (Supplementary Fig. S6). Interestingly, we found genes involved in cell-wall biogenesis, cellular motility, signaling transduction, ion and amino acid transport, cellular trafficking, and secretion (Supplementary Table S4). Most of these genes mediate the bacterial interface with the environment and therefore might be targeted by selection forces during adaptation processes. Similar to other pathogenicity factors that are under rapid evolution to avoid recognition by plant defense-related surveillance systems51 some of the effector genes also showed signatures of positive selection. We find at least two plausible explanations for the observed results. First, sampling bias produced by unknown demographic patterns may have created signal artifacts. Second, differences during host adaptation are also likely to generate the observed patterns. The first explanation seems less likely since the substitution rate between lineages remained constant, suggesting that both groups were equally represented in terms of mutations. Increasing the sample size will clarify this issue in future studies. The second explanation fits with the general view that both lineages were shaped by different evolutionary forces involving local adaptation to prevalent host genotypes in the archipelago.

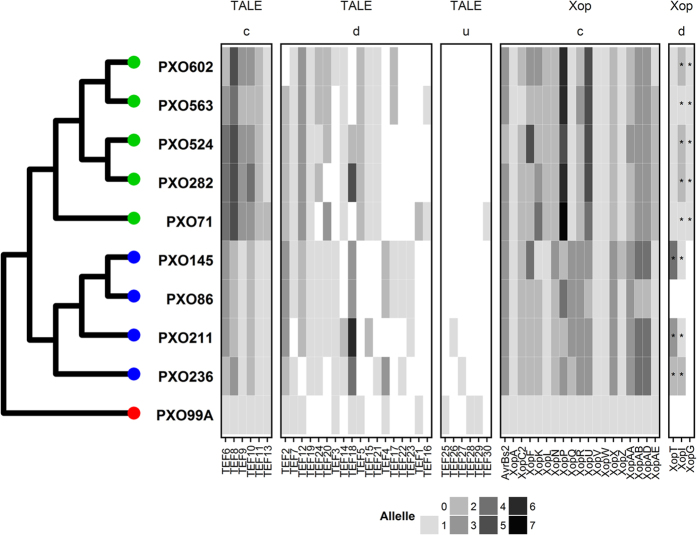

Diversification of effector repertoires following lineage split

Evolutionary divergence, as a result of host selection, is a common phenomenon in plant pathogens52. To understand the composition and distribution of effector genes, we first classified all 181 TALE protein sequences, including 15 pseudogenes, into 30 TALE families (TEFs) based on RVD configuration (Supplementary Table S5). Based on this classification, each TEF displayed up to 6 alleles with half of the TEFs carrying only one allele (Supplementary Table S5). Classification using the program DisTAL, which performs alignments based on repeat sequences34, largely reveals the same groupings (Supplementary Fig. S7). We also defined a set of TEFs representing the core (20%), dispensable (60%), and unique (20%) genes (Fig. 3). Xop families were more conserved across genomes, with core and dispensable families accounting for 86% and 14%, respectively. However, Xop sequences showed 1–7 alleles per family. Interestingly, pseudogenized XopG was found only in lineage PX-A (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Clustering of 10 Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae strains from the Philippines based on the distribution of effector genes.

Shaded blocks represent the presence of specific transcription activator-like effectors (TALEs) or Xanthomonas outer proteins (Xops) with darker grays indicating allelic variants (see Supplementary Table S4). TALE families (TEFs) and Xops are denoted at the bottom. Core (c), dispensable (d), and unique (u) effectors are highlighted at the top. Lineages are distinguished by color.

Similar to other plant pathogens that show extensive variation among type III effectors45 sympatric Xoo populations from the archipelago appear to maintain a diverse repertoire based on the number of alleles (Hd between 0.0 and 0.867). However, clustering analysis showed that TALE and Xop alleles are more likely to be shared by strains in the same lineage (Fig. 3), suggesting that diversification occurred mostly after lineage split. This inference is highly supported by the pattern of selection in PX-A vs. PX-B core genes (Supplementary Fig. S7), the composition of dispensable genes in PX-A and PX-B (Supplementary Fig. S5), and the pattern of recombination among members of the same lineage (Supplementary Fig. S4). However, other forms of variation such as recombination, repeat shuffling, or horizontal gene transfer with other taxa cannot be excluded as alternative ways to acquire effector families.

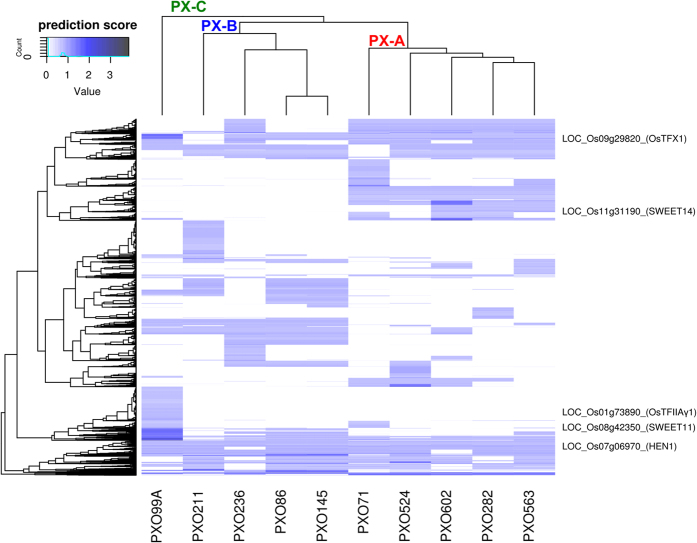

The activation of target genes by TALEs is guided by cognate effector binding elements (EBEs) in the host genome6. Based on DNA-binding specificities, TEF clustering followed the same pattern of classification as described using RVD distances (Supplementary Fig. S7). This indicates that alleles within each TEF are likely to have similar host targets. To investigate if members from the same lineage have functionally equivalent TEFs, we analyzed predicted target genes in the rice genome using the program Talvez35 and found that lineage members share more predicted targets that non-members (Fig. 4). For instance, lineage PX-A and PX-B members share 73% and 66% of the hits, respectively (Supplementary Table S6). This observation is consistent with effector diversification within genetically related groups due to environmental adaptation as observed in other plant pathogens53. In addition, the reduced number of core TEFs indicates some level of functional redundancy, a strategy that has been proposed for other pathogens with type III effectors54. For instance, Xanthomonas pathogens achieve functional redundancy by having TALEs bound to overlapping EBEs on the same promoter. The most notorious example in Xoo is the case of the SWEET14 susceptibility gene, which contains three known EBEs in its promoter12. In our data, several genes were predicted to be targets of multiple strains or have more than one putative EBE in the promoter region (Fig. 4), suggesting that functional redundancy could occur frequently. Overall, our observations reveal a unique evolutionary pathway of this pathogen in the agricultural landscape of the Philippine archipelago, in which different lineages diverged into modern Xoo races. This process was likely to be driven by diversification of effector repertoires during host adaptation.

Figure 4. Clustering of ten Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae strains from the Philippines by the predicted TALE targets in the rice genome (Nipponbare MSU7).

Targets were predicted as described in Perez-Quintero et al.35. Clustering of strains in the top follows lineage classification (green = PX-A, blue = PX-B, and red = PX-C). Clustering on the left represents rice target distribution for each TALE repertoire. Intensity of the histogram indicates normalized prediction score (1 being highest score for one TALE in the genome). Multiple prediction scores for the same gene for one strain were summed, so values higher than 1 indicate targeting by multiple TALE from the same strain. Examples of known TALE targets in the rice genome are shown on the right.

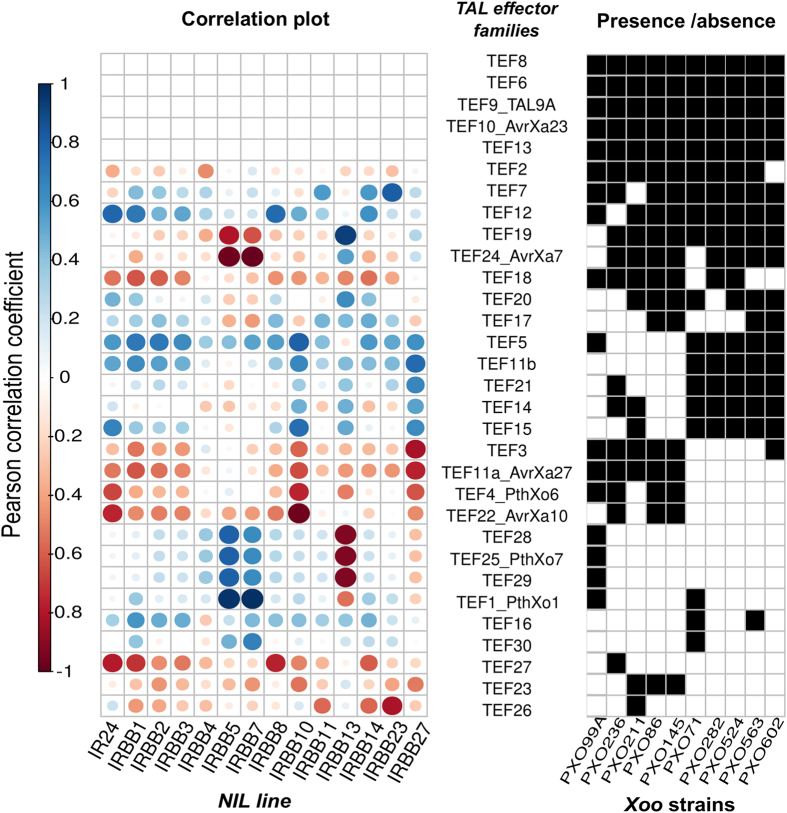

Effector repertoires underlying phenotypic differences

To assess the contribution of effector repertoires to the virulence spectrum, we measured disease symptoms on rice NILs carrying 14 known resistance genes. Interestingly, we found that members of the same lineage are more likely to have similar virulence spectra (Fig. 5). Even though the composition of TEF will not explain all the symptoms observed, phenotypic differences may be due to single major genes in some cases. We then analyzed possible correlations between the phenotypes and the effector composition of each strain. While the presence of several TEFs seemed to be associated with major effects (Fig. 6), smaller effects were observed for some Xops (Supplementary Fig. S8). A strong negative correlation between lesion length and presence of a TEF was found for known TALE/executor gene pairs, particularly evident in the case of AvrXa10/IRBB1055 and AvrXa27/IRBB2756 (Fig. 6). Curiously, the presence of TEF11b, very similar in RVD sequence to AvrXa27 (Supplementary Table S5), did not correlate with lesion length, suggesting that this variant might escape the Xa27 executor gene activation trap. No correlation was found for IRBB23/AvrXa2315 due to the absence of variation (all strains tested contained AvrXa23 and caused short lesions). This analysis also showed that AvrXa7 correlates negatively with Xa7-mediated resistance and positively to xa13-resistance (AvrXa7 can overcome xa13 resistance)57. The opposite was true for PthXo1, which highlights the importance of redundant targeting of SWEET families for Xoo pathogenicity. Both PXO99A and PXO71 appear to overcome xa5 resistance genes using PthXo1, a TALE that activates OsSWEET1158. Interestingly, members of TEF19 have a similar pattern to AvrXa7 (TEF24) for reaction on xa13, Xa7, and xa5. Since these members have different sequence specificities (Supplementary Table S5), TEF19 represents an opportunity to study targeting redundancy in the Xoo–rice interaction. Additional correlations, such as a correlation between xa8 and TEF12/TEF27, are currently being investigated. Overall, the associations of TEF with phenotype underscore the critical importance and utility of including TALE sequence analysis in any genotype-based approach to phenotyping20.

Figure 5. Clustering of 10 Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae strains from the Philippines based on lesion lengths 14 days after leaf clip inoculation to 14 near-isogenic lines (NILs) carrying single Xa genes.

Circles proportionally represent the length of the lesion averaged across 6 replicates. NILs are distinguished by color. Lineages are color-coded in the tree.

Figure 6. Correlation between presence/absence of transcription activator-like effector families (TEF) and phenotype, as measured by lesion length, on 14 near-isogenic lines in 10 Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae strains from the Philippines.

Circles proportionately (by size) indicate the Pearson correlation coefficients depicted using a color scale of blue (negative) to red (positive). The grid on the right indicates the presence (black) of at least one allele in each TEF. All alleles from one family were considered functionally similar except TEF11/AvrXa27.

Conclusions

The study of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) populations in the Philippine archipelago is particularly relevant because they have been derived from the ancestral population in Asia and represent one of the best characterized Xoo collections across the region. While the country is a natural laboratory for the deployment of improved varieties carrying large-effect genes, some of these effects on the pathogen side could be studied because the emerging populations remain isolated. We investigated isolates collected in the last four decades to understand the evolutionary forces that shape contemporary populations in the archipelago. Comparative genomics of a representative sample of races identified three genetic lineages, divergence of which predates their colonization of the islands. The patterns of positive selection, recombination, and diversification of effector genes suggest that each lineage adapted further during modern rice agriculture. Further analysis is needed if we want to understand the spatial and temporal effect of the green revolution in the archipelago.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Quibod, I. L. et al. Effector Diversification Contributes to Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae Phenotypic Adaptation in a Semi-Isolated Environment. Sci. Rep. 6, 34137; doi: 10.1038/srep34137 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Scientists at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) are partially funded by the Global Rice Science Partnership (GRiSP). The program is supported by the Consortium for International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). In addition, the work was partially funded by USAID. We want to thank Il-Ryong Choi for reviewing the manuscript. We acknowledge the technical assistance of Epifania Garcia and Ismael Mamiit.

Footnotes

Author Contributions Conceived and designed the experiments: I.L.Q., G.S.D., C.V.C., B.S., A.J.B. and R.O. Performed the experiments: I.L.Q., G.G., N.J.B., G.S.D. and A.P.-Q. Data analysis was done by I.L.Q., N.J.B., A.P.-Q. and G.S.D. Figures were prepared by I.L.Q., A.P.-Q., G.S.D. and G.G. The manuscript was written by R.O. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- McDonald B. A. & Linde C. Pathogen population genetics, evolutionary potential, and durable resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 40, 349–379 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mew T. W., Vera Cruz C. M. & Medalla E. S. Changes in race frequency of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae in response to rice cultivars planted in the Philippines. Plant Disease 76, 1029–1032 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Khan M. A., Naeem M. & Iqbal M. Breeding approaches for bacterial leaf blight resistance in rice (Oryza sativa L.), current status and future directions. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 139, 27–37 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Iyer-Pascuzzi A. S. & McCouch S. R. Recessive Resistance Genes and the Oryza sativa–Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae Pathosystem. MPMI 20, 731–739 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W. et al. The stripe rust resistance gene Yr10 encodes an evolutionary-conserved and unique CC-NBS-LRR sequence in wheat. Mol. Plant 7, 1740–1755 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boch J., Bonas U. & Lahaye T. TAL effectors-pathogen strategies and plant resistance engineering. New Phytol. 204, 823–832 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y. & Ronald P. Molecular determinants of disease and resistance in interactions of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae and rice. Microbes Infect. 4, 1361–1367 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White F. F. & Yang B. Host and pathogen factors controlling the rice-Xanthomonas oryzae interaction. Plant Physiol. 150, 1677–1686 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng F. & Zhou J. M. Plant-bacterial pathogen interactions mediated by type III effectors. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 15, 469–476 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha D., Gupta M. K., Patel H. K., Ranjan A. & Sonti R. V. Cell wall degrading enzyme induced rice innate immune responses are suppressed by the type 3 secretion system effectors XopN, XopQ, XopX and XopZ of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. PLoS One 8, e75867 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi K. et al. A receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase targeted by a plant pathogen effector is directly phosphorylated by the chitin receptor and mediates rice immunity. Cell Host Microbe 13, 347–357 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streubel J. et al. Five phylogenetically close rice SWEET genes confer TAL effector-mediated susceptibility to Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. New Phytol. 200, 808–819 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. Q. et al. Sugar transporters for intercellular exchange and nutrition of pathogens. Nature 468, 527–532 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugio A., Yang B., Zhu T. & White F. F. Two type III effector genes of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae control the induction of the host genes OsTFIIAgamma1 and OsTFX1 during bacterial blight of rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 10720–10725 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. L. et al. The broad bacterial blight resistance of rice line CBB23 is triggered by a novel transcription activator-like (TAL) effector of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. Mol. Plant Pathol. 15, 333–341 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swings J. et al. Reclassification of the Causal Agents of Bacterial Blight (Xanthomonas campestris pv. oryzae) and Bacterial Leaf Streak (Xanthomonas campestris pv. oryzicola) of Rice as Pathovars of Xanthomonas oryzae (ex Ishiyama 1922) sp. nov., nom. rev. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriol. 40, 309–311 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- Ardales E. Y. et al. Hierarchical analysis of spatial variation of the rice bacterial blight pathogen across diverse agroecosystems in the Philippines. Phytopathology 86, 241–252 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Vera Cruz C. M. et al. Predicting durability of a disease resistance gene based on an assessment of the fitness loss and epidemiological consequences of avirulence gene mutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 13500–13505 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raitzer D. A. et al. Is Rice Improvement Still Making a Difference? Assessing the Economic, Poverty, And Food Security Impacts of Rice Varieties Released from 1989 to 2010 in Bangladesh, Indonesia, and the Philippines. (CGIAR Independent Science and Partnership Council (ISPC), Rome, Italy, 2015).

- Booher N. J. et al. Single molecule real-time sequencing of Xanthomonas oryzae genomes reveals a dynamic structure and complexTAL (transcription activator-like) effector gene relationships. Microbial. Genomics 1, 1–22 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzberg S. L. et al. Genome sequence and rapid evolution of the rice pathogen Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae PXO99A. BMC Genomics 9, 204 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treangen T. J., Ondov B. D., Koren S. & Phillippy A. M. The Harvest suite for rapid core-genome alignment and visualization of thousands of intraspecific microbial genomes. Genome Biol. 15, 524 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reumerman R. A., Tucker N. P., Herron P. R., Hoskisson P. A. & Sangal V. Tool for rapid annotation of microbial SNPs (TRAMS): a simple program for rapid annotation of genomic variation in prokaryotes. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 104, 431–434 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30, 1312–1313 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huson D. H. SplitsTree: analyzing and visualizing evolutionary data. Bioinformatics 14, 68–73 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marttinen P. et al. Detection of recombination events in bacterial genomes from large population samples. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, e6 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard J. K., Stephens M. & Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155, 945–959 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis R. M. POPHELPER: An R package and web app to analyse and visualise population structure. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 10.1111/1755-0998.12509 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rissman A. I. et al. Reordering contigs of draft genomes using the Mauve aligner. Bioinformatics 25, 2071–2073 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras-Moreira B. & Vinuesa P. GET_HOMOLOGUES, a versatile software package for scalable and robust microbial pangenome analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 7696–7701 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. & Nielsen R. Estimating synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution rates under realistic evolutionary models. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17, 32–43 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Zhang Y., Zhang Z., Zhu J. & Yu J. KaKs_Calculator 2.0: a toolkit incorporating gamma-series methods and sliding window strategies. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 8, 77–80 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Quintero A. L. et al. QueTAL: a suite of tools to classify and compare TAL effectors functionally and phylogenetically. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 545 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Quintero A. L. et al. An improved method for TAL effectors DNA-binding sites prediction reveals functional convergence in TAL repertoires of Xanthomonas oryzae strains. PLoS One 8, e68464 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Librado P. & Rozas J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 25, 1451–1452 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdon J. J. & Thrall P. H. Pathogen evolution across the agro-ecological interface: implications for disease management. Evol. Appl. 1, 57–65 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen J. et al. A Pinatubo climate modeling investigation In The Mount Pinatubo Eruption: Effects on the Atmosphere and Climate (eds Fiocco G., Fua, & Visconti, ) 233–272 (Springer-Verlag, 1996). [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari T. B. et al. Genetic Diversity of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae in Asia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61, 966–971 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin L. et al. New multilocus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis tool for surveillance and local epidemiology of bacterial leaf blight and bacterial leaf streak of rice caused by Xanthomonas oryzae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 688–698 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H. et al. Acquisition and evolution of plant pathogenesis-associated gene clusters and candidate determinants of tissue-specificity in Xanthomonas. PLoS One 3, e3828 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feil E. J. & Spratt B. G. Recombination and the population structures of bacterial pathogens. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55, 561–590 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mhedbi-Hajri N. et al. Evolutionary history of the plant pathogenic bacterium Xanthomonas axonopodis. Plos one 8, e58474 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. et al. Positive selection is the main driving force for evolution of citrus canker-causing Xanthomonas. ISME J. 9, 2128–2138 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann H. C. et al. Genomic analysis of the Kiwifruit pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae provides insight into the origins of an emergent plant disease. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003503 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicker E. et al. Contrasting recombination patterns and demographic histories of the plant pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum inferred from MLSA. ISME J. 6, 961–974 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medini D., Donati C., Tettelin H., Masignani V. & Rappuoli R. The microbial pan-genome. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 15, 589–594 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daubin V. & Ochman H. Bacterial genomes as new gene homes: the genealogy of ORFans in E. coli. Genome Res. 14, 1036–1042 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira R. M. et al. A TALE of transposition: Tn3-like transposons play a major role in the spread of pathogenicity determinants of Xanthomonas citri and other Xanthomonads. M. Bio. 6, e02505–e02514 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt W. B. & Dean A. M. Molecular-functional studies of adaptive genetic variation in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 34, 593–622 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman D. S., Gropp S. J., Morgan R. L. & Wang P. W. Diversifying selection drives the evolution of the type III secretion system pilus of Pseudomonas syringae. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23, 2342–2354 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasier M. The dynamics of fungal speciation In Evolutionary Biology of the Fungi (eds Rayner A. D. M. Brasier C. M. & Moore D.) 231–260 (Cambridge University Press, 1987). [Google Scholar]

- Ma W., Dong F. F., Stavrinides J. & Guttman D. S. Type III effector diversification via both pathoadaptation and horizontal transfer in response to a coevolutionary arms race. PLoS Genet. 2, e209 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koebnik R. & Lindeberg M. Comparative genomics and evolution of bacterial type III effectors in Effectors In Plant-Microbe Interactions (eds Martin F. & Kamoun S.) 55–76 (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Tian D. et al. The rice TAL effector-dependent resistance protein XA10 triggers cell death and calcium depletion in the endoplasmic reticulum. Plant Cell 26, 497–515 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu K. et al. R gene expression induced by a type-III effector triggers disease resistance in rice. Nature 435, 1122–1125 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B., Sugio A. & White F. F. Os8N3 is a host disease-susceptibility gene for bacterial blight of rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 10503–10508 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S. et al. The broadly effective recessive resistance gene xa5 of rice is a virulence effector-dependent quantitative trait for bacterial blight. Plant J. 86, 186–194 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.