Abstract

Background

Ear wax lubricates, cleans and protects the external auditory canal while ear self-cleaning can lead to ear infections, trauma and perforation of the tympanic membrane. An erroneous understanding of these facts can lead to wrong practices with grievous consequences.

Objective

To assess the knowledge on ear wax and the effects of ear self-cleaning among health workers in Nigeria.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was done on health workers in a tertiary hospital in Nigeria with administration of structured questionnaire. Knowledge of the participants on the effect of ear self-cleaning were classified as poor, fair or good based on the calculation of their knowledge score.

Results

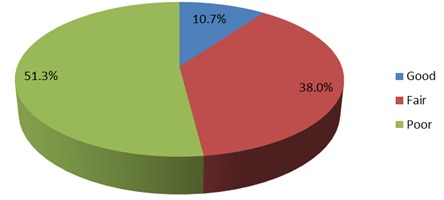

Out of 150 respondents, 10.7% of them had good knowledge of ear wax and the health effects of self-ear cleaning while 51.3% had poor knowledge. There was strong association between knowledge score and occupation (x2=24.113, P=0.007), while there was no association between knowledge score and practice of ear self-cleaning.

Conclusion

Most respondents had poor knowledge of the function of ear wax and the damage to the auditory canal associated with ear self-cleaning. There is thus, the need for public enlightenment on the complications of the practice.

Keywords: Health workers, Knowledge, Ear self-cleaning, Wax, Nigeria

Introduction

Cerumen (ear wax) is a normal secretion from the ceruminous and the sebaceous glands of the outer third of external auditory canal1,2. It is composed of glycopeptides, lipids, hyaluronic acid, sialic acid, lysosomal enzymes and immunoglobulins. Cerumen exerts a protective effect by maintaining an acidic milieu (pH of 5.2 - 7.0) in the external auditory canal whilst also lubricating the canal3,4,6. It has also been shown to have significant antibacterial and antifungal properties6.

A normal external auditory canal has a natural self-cleansing mechanism whereby the cerumen and other particulate move out of the ear canal on their own with the aid of jaw movement7,8. It is believed that ear self-cleaning interferes with this natural process and may predispose to certain diseases of the ear8,9It has been reported that most individuals consider cerumen as dirt and harmful to the human body10-12. The resultant effect of this erroneous belief is the practice of self-ear cleaning11,12. Ear self-cleaning is an act of insertion of objects into one's own ears with the aim of cleaning them7,8.

It was reported that the most preferred object for self-ear cleaning is cotton bud10-13, nevertheless, some use feathers, biro pen cover, broom stick, match sticks and finger7,12,13. This practice impairs the natural cleansing mechanism of the ear7,8. Self-ear cleaning has widely been condemned by otolaryngologists due to well documented complications which include trauma, impacted ear wax, infection and retention of the cotton bud7-16.

Generally, health care work force is responsible for provision of health care services to the people amongst which is the care of the ear. By this, they are in the position to counsel and educate the people about the care of their ear. However, for the health worker to be effective in correcting this misconception and consequent ill practice of self-ear cleaning, they must have adequate knowledge about appropriate care of the ear. Therefore, this study was aimed at assessing the knowledge of the health workers about the benefit of cerumen and side effects of ear self-cleaning.

Materials and Methods

This was a descriptive, cross-sectional study which was conducted among health workers at Babcock University Teaching Hospital, Ilisan-Remo, Southwest Nigeria between the period of April and June, 2015. The subjects comprised of 150 health workers of the institution. The study participants were selected using stratified sampling technique, the stratification was based on job category. The number of participants selected from each job category was determined using proportional allocation. The inclusion criteria was health workers that have worked in the institution for a minimum of 6 months, while those working in the ENT clinics were excluded from the study and they include ENT surgeons, residents and nurses.

Structured self-administered questionnaire was used for data collection. The questionnaire was subdivided into 3 sections:

Section1- sociodemographic characteristics of respondents

Section 2- addressed their knowledge about the health benefits of cerumen and the side effects of ear self-cleaning; this section contained 6 questions. Favorable/correct response to each question was awarded a grade of 1 point while a wrong response was awarded zero giving a maximum obtainable score of 6 and a minimum score of zero. For the purpose of analysis, knowledge score was graded and interpreted as follows: poor = 0 - 2, fair = 3 - 4, good = 5 - 6.

Section 3- addressed the perceived dangers of cerumen and the advantages of self-ear cleaning

The data obtained were analyzed using SPSS for windows version 14.0 and presented descriptively and in tables and charts. Chi-square tests were used to test for associations between variables while statistical significance was at p-value of less than 0.05.

Results

One hundred and fifty health workers were involved in this study. Their age range was 17 - 61years with a mean age 33 ± 9.12 years and majority (58.7%) were females with a male: female ratio of 1: 1.41 while 68% of them had tertiary education (Table1). In all, 10.7% of the health workers had good knowledge of ear wax and health effects of self-ear cleaning while 51.3% had poor knowledge (Figure1). The knowledge score was significantly associated with the age of the respondents (p=0.032) while the gender, educational status and religion were not associated with the knowledge score (Table 2).

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents.

| CATEGORY | FREQUENCY | PERCENTAGE | |

| Age | <20 | 5 | 3.3 |

| 20-29 | 43 | 28.8 | |

| 30-39 | 67 | 44.7 | |

| 40-49 | 26 | 17.3 | |

| 50-59 | 8 | 5.3 | |

| >60 | 1 | 0.7 | |

| Gender | Male | 62 | 41.3 |

| Female | 88 | 58.7 | |

| Occupation | Doctor | 46 | 30.7 |

| Nurse | 34 | 22.7 | |

| Pharmacist | 7 | 4.7 | |

| Physiotherapist | 6 | 4.0 | |

| Laboratory scientist | 15 | 10.0 | |

| Non clinical | 42 | 28.0 | |

| Educational status | University | 102 | 68.0 |

| Post secondary | 38 | 25.3 | |

| Secondary | 10 | 6.7 |

Figure 1. Knowledge score of respondents about cerumen and ear self-cleaning.

Table 2. Knowledge score of respondents by sociodemographic characteristics.

| Variable | Test of Significance | |||

| Knowledge Score | X2=3.467df = 2p value =0.177 | |||

| Poor | Fair | Good | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 31(50.0%) | 21(33.9%) | 10(16.1%) | |

| Female | 46(52.3%) | 36(40.9%) | 6(6.8%) | |

| Age | ||||

| X2=95.749df =72p value= 0.032 | ||||

| <20 | 3(60%) | 2(40%) | 0(0%) | |

| 21 -29 | 22(51.2%) | 17(39.5%) | 4(11.6%) | |

| 30-39 | 40(59.7%) | 20(29.9%) | 7(10.4%) | |

| 40-49 | 10(38.5%) | 11(42.3%) | 5(19.2%) | |

| 50-59 | 1(12.5%) | 7(87.5%) | 0(0%) | |

| >60 | 1(100%) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | |

| Tribe | ||||

| Yoruba | 44(46.8%) | 38(40.4%) | 12(12.8%) | X2=3.842df=6p value=0.700 |

| Ibo | 27(58.7%) | 15(32.6%) | 4(8.9%) | |

| Hausa | 3(50%) | 3(50%) | 0(0%) | |

| Others | 3(75%) | 1(25%) | 0(0%) | |

| Religion | ||||

| Christian | 72(49.7%) | 57(39.3%) | 16(11.0%) | X2=4.904df =2p value=0.08 |

| Muslim | 5(100%) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | |

| Education | ||||

| University | 46(45.1%) | 42(41.2%) | 14(13.8%) | X2= 7.268df =4p= 0.122 |

| Post-secondary | 23(60.5%) | 13(34.2%) | 2(5.2%) | |

| Secondary | 8(80%) | 2(20%) | 0(0%) | |

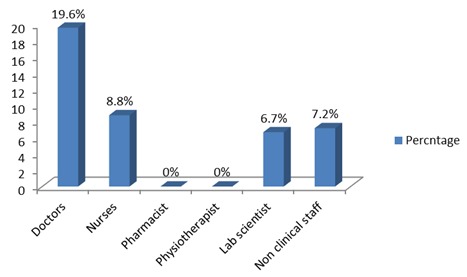

Among the doctors 19.6% had good knowledge while 34.5% of them had poor knowledge whereas, among the physiotherapist none had good knowledge while 83.3% had poor knowledge of the health effect of earwax and ear self-cleaning. The knowledge score was significantly associated with job category with p=0.007 (Table 3). Similarly, while 19.6% of doctors had good knowledge, none of the physiotherapist and pharmacist had good knowledge (Figure2).

Table 3. Relationship between the knowledge of health effects and occupation.

| Occupation | Knowledge Score | Test of significance | ||

| Poor | Fair | Good | X2=24.113df =10p value= 0.007 | |

| Doctor | 16(34.5%) | 21(45.6%) | 9(19.6%) | |

| Nurses | 12(34.3%) | 19(55.9%) | 3(8.8%) | |

| Pharmacist | 5(71.4%) | 2(28%) | 0(0%) | |

| Physiotherapist | 5(83.3%) | 1(16.7%) | 0(0%) | |

| Lab scientist | 8(53.3%) | 6(40.0%) | 1(6.7%) | |

| Non clinical staff | 31(73.8%) | 8(19.0%) | 3(7.2%) | |

Figure 2. Proportion of health workers by their profession with good knowledge of the complications of ear self-cleaning.

Table 4 shows that among those practicing ear self-cleaning 52.5% had poor knowledge of health effects of ear self-cleaning whereas among those who are not practicing ear self-cleaning 33.3% had poor knowledge. There was no significant association between the knowledge and practice of ear self-cleaning as p=0.072.

Table 4. Association between knowledge of health attributes of cerumen and complications of ear self-cleaning.

| Variable | Test of significance | |||

| Practice self-ear cleaning | Knowledge Score | X2=5.271df=2p value= 0.072 | ||

| Poor | Fair | Good | ||

| Yes | 74(52.5%) | 54(38.3%) | 13(9.2%) | |

| No | 3(33.3%) | 3(33.3%) | 3(33.3%) | |

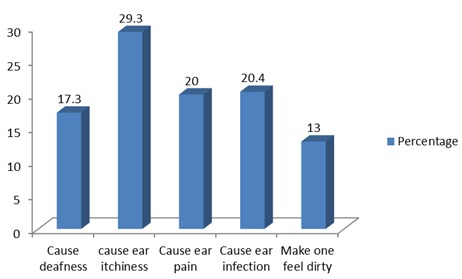

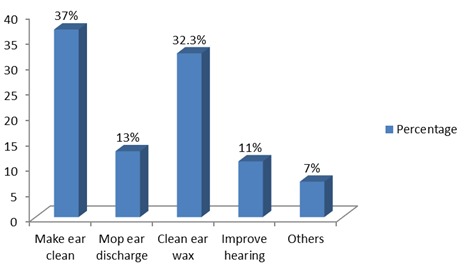

The perceived complications of cerumen (Figure3) include deafness (17.3%), ear itchiness (29.3%), ear ache (20%), ear infection (20.4%), makes one feel dirty (13%) while the perceived benefits of ear self-cleaning (Figure4) include clean ear (37%), mop ear discharge (13%), clean ear wax (32.2%), improve hearing (11%) and others (7%) as a part of daily hygiene.

Figure 3. Perceived effects of ear wax by respondents.

Figure 4. Perceived benefits of ear self-cleaning by respondents.

Discussion

The main finding of this study was that 51.3% of the health workers had poor knowledge of the functions of ear wax and complications of ear self-cleaning. Knowledge score was significantly associated with job category as doctors had highest knowledge score. It has been established that the ear does not need to be cleaned and that the cerumen (earwax) protects and lubricates the external auditory canal, thus does not need to be cleaned7-10. The normal canal has a self cleansing mechanism by which cerumen is moved outward, eventually reaching outside the ear and flaking off7,8,15. Experts believe that self ear cleaning interferes with this natural process and may predispose to trauma and ear infections7,8,10. In a previous study carried out among health workers in Nigeria, it was recorded that 94% of them practiced self ear cleaning7.

In this study, the knowledge of the respondents about the function/harm of cerumen and the health effect of self ear cleaning was determined in a bid to identify the factors responsible for high prevalence of self ear cleaning amongst them. In addition, the association of the knowledge score with the sociodemographic characteristics was also determined.

About half of the respondents (51.3%) had poor knowledge score of the functions of cerumen and the complications of ear self-cleaning even though they were health workers. The implication is that they would not advise patients against regular ear cleaning. Previous studies done (most of which were community based) revealed wrong beliefs concerning cerumen and self ear cleaning. Hobson et al12 conducted a survey on 325 individuals and observed that majority of them cleaned their ears with cotton bud regularly and were ignorant about the injurious effects. Salahuddin et al16 had a similar observation whereby 93% of their study group (hospital patients) who practice ear self-cleaning were ignorant of its harmful effects16. In a community based study in Bida, Nigeria, Olajide et al10 observed that 61.2% of their respondents had erroneous beliefs that there were benefits in self ear cleaning (using cotton bud). In addition to this, he explained that most (74.1%) of their respondents had no information on the dangers of self ear cleaning (using cotton buds)10. Olaosun noted that medical advice about the adverse effect of self ear cleaning is not widely known8. Therefore, we can infer that the reason for wrong practices among the general public is due to poor knowledge and perception of the health workers would usually give advice to their patients.

Knowledge score was found to be significantly associated with their occupation (x2=24.113, p = 0.007) as majority of people with good knowledge were doctors. Nevertheless, most of the doctors had fair and poor knowledge score, this finding may be due to the limited otolaryngology exposure during their undergraduate and postgraduate training as this has been reported in many parts of the world17-20. Surveys of undergraduate otolaryngology training in the United Kingdom revealed that, the average time spent with the otolaryngology department during medical school training is one and a half weeks. Further more in the same study, forty-two percent of students did not have a formal assessment of their clinical skills or knowledge at the end of the otolaryngology rotations and six of the 27 (22%) medical schools did not have a compulsory otolaryngology rotation17,18.

The second opportunity for training among physicians is during postgraduate medical education. A survey of Canadian family medicine residents reported that 66.7% received very little classroom instruction and 75.6% received very little clinical otolaryngology instruction19. This finding is supported by another Canadian study which showed that opportunities for formal education in otolaryngology in primary care residencies are not common1.

Furthermore, a survey of general practitioners (GPs) in England showed that 75% would like further training in otolaryngology21. Three-quarters of these GPs felt that their undergraduate training in otolaryngology was inadequate and almost half felt that their postgraduate training in otolaryngology was inadequate21. In America, a study was done to assess the otolaryngology knowledge of a group of primary care practitioners, attending an otolaryngology update course. The results of the pre-course knowledge test were not better. Mean knowledge score out of a maximum score of 12 was 4.0 +/- 1.7 (33.3% +/- 14.0%). The results were further sorted by specialty area, and again all categories scored poorly on the pre-knowledge test22.

There was a significant negative association between self-ear-cleaning and the knowledge score of respondent (x2=5.271, p = 0.072). This is comparable to the finding of Sidhartha23 who noted that there was no significant association between awareness of the complications of self-ear cleaning and cotton bud use because he observed that 52% of those practicing self-ear cleaning in his study were aware of the potential dangers and complications that can result from such practice.

This study revealed that there is low level of otolaryngology knowledge among health workers in Nigeria which could be due to limited exposure to otolaryngology during their undergraduate and postgraduate medical training hence the need for continuing medical education in otolaryngology.

The limitation of this study was that it was conducted in a single healthcare facility and the sample size also appears small to be able to make a generalized conclusion. A multi-center study is an option to widen coverage and enlist more participants.

Conclusions

This study has shown that most respondents had an inadequate knowledge of the functions of cerumen and the complications of ear self-cleaning. Public enlightenment will improve on the knowledge and perception of both health workers and patients in this environment.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Grant support: None

References

- 1.Burton MJ, Doree C. Ear drops for the removal of ear wax. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Adegbiji WA, Alabi BS, Olajuyin OA, Nwawolo CC. Earwax Impaction: Symptoms, Predisposing Factors and Perception among Nigerians. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. 20014;3(4):371–382. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.148116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carr MM, Smith RL. Ceruminolytic efficacy in adults versus children. Journal of Otolaryngology. 2001;30(3):154–156. doi: 10.2310/7070.2001.20001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keane EM, Wilson H, McGrane D, Coakley D, Walsh JB. Use of solvents to disperse ear wax. British Journal of Clinical Practice. 1995;49(2):71–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roland PS, Smith TL, Schwartz SR, Rosenfeld RM, Ballachanda B, Earll JM. Clinical practice guideline: Cerumen impaction. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;139(Suppl 2):s1–s21. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lum CL, Jeyanthi S, Prepageran N, Vadivelu J, Raman R. Antibacterial and antifungal properties of human cerumen. J Laryngol Otol. 2009;123:375–378. doi: 10.1017/S0022215108003307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oladeji SM, Adenekan AK, Nwawolo CC, Uche-Okonkwo KC, Johnson KJ. Self ear cleaning among Health workers in Nigeria. IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences. 2015;14(8):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olaosun AO. Self-Ear-Cleaning among Educated Young Adults in Nigeria. . Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. 2014;3:17–21. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.130262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olaosun A. Does Self ear cleaning increase the risk of ear disease? International Journal of Recent Scientific Research. 2014;5(6):1087–1090. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olajide TG, Usman AM, Eletta AP. Knowledge, Attitude and Awareness of Hazards Associated with Use of Cotton Bud in a Nigerian Community. International Journal of Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery. 2015;4:245–253. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Afolabi OA, Aremu SK, Alabi BS, Segun-Busari S. Traumatic Tympanic Membrane perforation: An aetiological profile. BMC Res Notes. 2009;2:323. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hobson JC, Lavy JA. Use and abuse of cotton buds. 2005;98:360–361. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.98.8.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee LM, Govindaraju R, Hon SK. Cotton bud and ear cleaning: A loose tip cotton bud? Med J Malaysi. 2005;60:85–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Macknin ML, Talo H, Medendrop SV. Effect of cotton tipped swab use on ear wax occlusion. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1994;33:14–18. doi: 10.1177/000992289403300103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alvord LS, Farmer BL. Anatomy and orientation of the human external ear. J Am Acad Audiol. 1997;8:383–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salahuddin A, Syed A, Syed M, Sibghatullah R, Tauhidul I, Bashir A. Association of Dermatological Conditions of External Ear with the Use of Cotton Buds. J Enam Med Col . 2014;4(3):174–176. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mace A, Narula A. Survey of current undergraduate otolaryngology training in the United Kingdom. . J Laryngol Otol. 2004;118:217–220. doi: 10.1258/002221504322928008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joshi J, Carrie S. A survey of undergraduate otolaryngology experience at Newcastle University Medical School. J Laryngol Otol. 2006;120:770–773. doi: 10.1017/S0022215106002131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glicksman JT, Brandt MG, Parr J, Fung K. Needs assessment of undergraduate education in otolaryngology among family medicine residents. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;37:668–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong A, Fung K. Otolaryngology in undergraduate medical education. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg . 2009;38:38–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clamp PJ, Gunasekaran S, Pothier DD, Saunders MW. ENT in general practice: training, experience and referral rates. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:580–583. doi: 10.1017/S0022215106003495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amanda H, Maya G, Tanya K. A need for otolaryngology education among primary care providers. [2016 Jan 11];http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/meo.v17i0.17350. 17350Med Educ Online. 2012 17 doi: 10.3402/meo.v17i0.17350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sidharta N. Extent of cotton bud use in ears. British Journal of General Practice. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]