Abstract

Background

A study from the University College Hospital, Ibadan, Southwest, Nigeria on bladder cancers had described an increase in the frequency of urothelial carcinoma compared to the earlier reported preponderance of squamous-cell carcinoma.

Aim

To provide an update on the histopathologic pattern of bladder cancers in our community and to explore its implications for future health system policies.

Methods

The records of the Ibadan Cancer Registry from January 1997 to December 2014 were reviewed and the data analyzed for the histologic subtypes of bladder cancers diagnosed in the hospital.

Results

Two hundred and sixteen bladder tumours were recorded during this period with a male to female ratio of 3.2:1. Complete information was available in 195 cases of which 181 (96.8%) were bladder carcinomas whilst 14 were sarcomas. Of the bladder carcinomas, 68.5%, 19.9% and 11.6% were urothelial carcinomas, squamous cell carcinomas, and adenocarcinomas (AC) respectively. Urothelial carcinoma was more common in all age groups and its peak age of occurrence was in the 51-60 year age group. The peak age for squamous cell carcinoma was in the 41-50 year age group. Mean and median age of occurrence was significantly lower in females in the urothelial and squamous cell carcinomas, but lowest in squamous cell carcinoma [P = < 0.0001].

Conclusion

This population study has confirmed urothelial carcinoma as the predominant histotype of bladder cancer in Ibadan, Southwest Nigeria currently and that both urothelial and squamous cell carcinomas occur earlier in women.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Bladder carcinoma, Urothelial carcinoma, Squamous cell carcinoma, Schistosomiasis, Ibadan, Nigeria

Introduction

Bladder cancer is the 7th most common cancer worldwide, accounting for 3.2% of all cancers1. It is considerably more common in males than in females, , with an estimated 260,000 new cases occurring each year in men and 76,000 in women giving a worldwide male to female ratio of 3.5:11.

In developed nations such as the United States, France and Italy, urothelial carcinoma (UC) constitutes more than 90% of the bladder cancers1. In these countries, cigarette smoking and occupational exposure to chemicals such as aniline dyes and aromatic amines which predispose to UC are important risk factors for bladder cancer1,2,3 .Regions such as Eastern and Northern Europe, Africa, and Asia however, show a prevalence of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) which is thought to be due to the endemicity of chronic schistosomal cystitis in these areas4,5,6 .

Bladder cancer is the second most common malignancy of the urogenital system after prostate cancer in Nigeria7. Reports from Nigeria on the histological pattern are however conflicting with an earlier study from the Southwest and most studies from Northern Nigeria8-11reporting a higher incidence of SCC than UC. On the other hand, studies from the middle belt and south-eastern regions of the country8,12,13had reported a higher frequency of UC. A later study from our centre reported a change in the relative distribution of UC and SCC in bladders diagnosed between 1979-198014, with SCC becoming less common than had been described in the earlier study (1963-1973)8. The authors suggested that this might be due to a reduction in the role of chronic schistosomal cystitis as a causative risk factor for bladder cancer in the community along with increased exposure to UC-risk factors due to urbanization and industrialization.

This study aimed to determine the current histologic pattern of bladder cancer in Ibadan, Southwestern, Nigeria, over a seventeen-year period.

Materials and Methods

This is a retrospective review of bladder cancers diagnosed at the University College Hospital (UCH), Ibadan, Nigeria from January 1997 to December 2014. The demographic data and histopathological findings for the patients were retrieved from the records of the Ibadan Cancer Registry. The indices evaluated were age, gender, and the histological diagnosis. The data obtained were analyzed with SPSS Version 15.0. The data were asymmetrical and therefore the medians and the interquartile ranges were compared rather than means using the Chi-square Test and the level of significance was P = < 0.05.

Results

A total of 216 bladder tumours were recorded in the Ibadan Cancer Registry during the period of the study. Twenty-one (9.7%) of the 216 cases were excluded on account of incomplete information. Of the remaining 195 cases, 181(96.8%) were bladder carcinomas while 14 (3.2%) were sarcomas. The 14 sarcomas comprised of 10 cases of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma, 1 case of pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma, 1 case of leiomyosarcoma, and 2 cases of undifferentiated sarcoma (one of which was diagnosed as rhabdomyosarcoma by immunohistochemistry). All the embryonal rhabdomyosarcomas occurred in patients less than 5 years except for 2 cases in a 13 and a 15 year old.

The male to female ratio for all bladder tumours in our study was 3.2:1, and within bladder cancers, the overall male to female ratio was 3.1:1. This ratio however varied amongst the different histotypes and was significantly lower in AC (2.0:1), than UC (3.3:1) and SCC (3.5:1) with p = 0.0001 as shown in Table 1. Due to the small numbers of sarcomas, only the bladder carcinomas were evaluated further in this study.

Table 1. Sex distribution of the different histological types of bladder carcinoma.

| Total Number (% Total) | Male (M) (% Total) | Female (F)(% Total) | M:F Ratio | |

| Total | 181 (100) | 137 (75.7) | 44 (24.3) | 3.1 |

| Urothelial carcinoma | 124 (68.5) | 95 (76.6) | 29 (23.4) | 3.3 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 36 (19.9) | 28 (77.8) | 8 (22.2) | 3.5 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 21 (11.6) | 14 (66.7) | 7 (33.3) | 2.0 |

Of the 181 carcinomas, 122 (68.5%) were UC, 36 (19.9%) were SCC whilst 21(11.6%) were AC. Eight (38%) of the AC were primary tumours and 13 (62%) were metastatic. Four cases (2.2%) that were initially diagnosed as mixed carcinoma were re-classified as UC on further evaluation as they included urothelial components.

The age range of all patients with bladder carcinoma was 20 to 90 years whilst the mean and median ages of occurrence were 58.6± 14.2 years and 59 years respectively. The overall peak age of occurrence was in the 51-60 year age range. When each of UC and SCC were considered separately, UC and SCC showed peak occurrence in the 51-60 and the 41-50 year age ranges respectively with p = 0.0001) as indicated in Table 2. The peak incidence of adenocarcinomas straddled both 41-50 and 51-60 age groups. The mean and median ages of occurrence also varied between the histotypes and were highest and lowest in UC and adenocarcinoma respectively (Table 3). Additional analyses revealed that the mean and median ages of occurrence were lower in females than males in the UC and SCC (P=0.0002 and 0.008 respectively), with difference being greater in SCC (P = 0.004) (Table 3).

Table 2. The age distribution of the different histological types of bladder carcinoma.

| Age-group | UC (% of Total) | SCC (% of Total) | AC (% of Total) | Total (% of Total) |

| 11-30 | 4 (3.23) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.76) | 5 (2.76) |

| 31-50 | 28 (22.58) | 16 (44.44) | 7 (33.33) | 51 (28.18) |

| 51-70 | 60 (48.39) | 15 (41.67) | 9 (42.86) | 84 (46.41) |

| 71-90 | 32 (25.81) | 5 (13.89) | 4 (19.05) | 41 (22.65) |

| Total | 124 (100.00) | 36 (100.00) | 21 (100.00) | 181 (100.00) |

Table 3. Comparison of medians and interquartile ranges of the different histological types of bladder carcinoma.

| Overall | Median | |||||

| Median | Interquartile Ranges | Male | Female | p value | ||

| Urothelial carcinoma | 60 | 65 | 62 | 53 | 0.0002 | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 54 | 47 | 55 | 50 | 0.0075 | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 52 | 54 | 52 | 52 | 0.163 | |

Discussion

Our study shows that urothelial carcinoma is now the most common bladder cancer in our locality whilst squamous cell carcinoma is the second most common with peak occurrences in the sixth and fifth decades of life respectively. Additionally, we found that although bladder cancer is more common in males in our community, the peak age of occurrence is lower in females and especially in SCC.

Accurate incidence and prevalence figures for bladder cancer are not available for Nigeria 1. However, available evidence shows that the hospital incidence for bladder tumours varies from one geopolitical zone of Nigeria to the other, with an average of 2 to 20 cases per year 7,8, 12,14, 16. This study is the largest population study on bladder tumours from Nigeria thus far, and it shows that the incidence of the disease in the Ibadan Cancer Registry has increased over the years. The earlier study from our centre by Thomas and Onyemenen reported 71 bladder cancers over a period of 10 years (an average of 7 cases per year), whilst we found 216 cases over 18 years (an average of 12 cases per year). Researchers from Sokoto also described a 4.7 fold increase in the incidence of this malignancy 17.

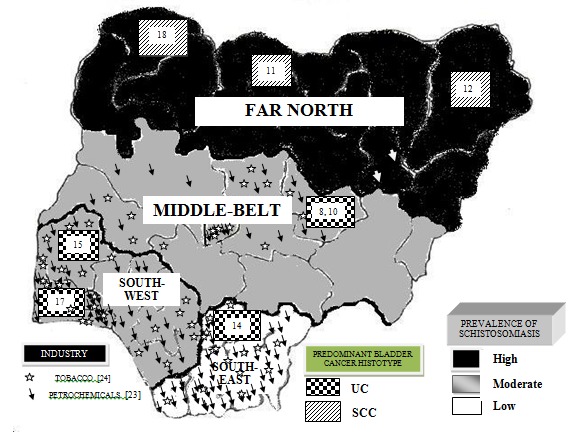

Our study also found UC as the predominant bladder cancer diagnosed in Ibadan and its environs in all age-groups and confirms the changing trend in the region earlier observed by Thomas 14. This finding is in keeping with reports from studies done in other centres in the southern region of the country 11,14 (Table 4. Although, schistosomal infection is also recognized as a risk-factor for UC and AC 5,6, these studies suggest changes in the epidemiology of bladder cancers in the middle belt and southern Nigeria which is likely due to a combination of a decrease in schistosomal infections and the increased the exposure to non-schistosomal cystitis and other carcinogenic agents associated with urbanization and the proliferation of industries (especially tobacco and petrochemical factories) implicated in the causation of UC in these zones of the country (Figure1 and Table 5) 4. The decrease in schistosomal infections is due to general and specific measures directed at the control of the parasite and treatment of the disease 5, 18. Causes of non-schistosomal cystitis include chronic infections, urinary bladder stones, chronic indwelling catheters, spinal cord injury, and bladder diverticula 3, 5, 17. Interestingly, Khaled had anticipated that, with the eradication of schistosomiasis, other risk factors for bladder cancer would play more important roles in the development of this disease in Africa 6.

Table 4. The relative frequencies of different histological types of bladder carcinoma from various studies (The relative frequencies of these carcinomas among bladder tumours in general are shown in parentheses where the figures are available).

| Aghaji AE et al, 1989 14n = 103 cases | Obafunwa JO, 199110n = 38 cases | Thomas and Onyemenen, 199515n =71 cases | Mandong et al, 20008n = 97 cases | Ochicha O et al, 200311n = 89 cases | Mungadi IA et al, 2007 18 | Eni UE et al, 200812n = 65 cases | Anunobi CC et al, 201017n = 39 cases | This study n = 181cases | |

| UCSCC AC*Undiff. Ca/ Small Cell Ca/ Anaplastic CaOthers | 56.3%38.8%1.9%Leiomyosarcoma: (1.9%) leiomyoma 1% | 26.3%52.6%5.3%15.8% | 49.9% 46.5% 2.2% 1.4% | 52.1% (50.5%)44.7% (43.3%)3.2% (3.0% )3.2% (3.0%) | 35%53%4%8%2% | 65.1% | 23%70.8% 6.2% | 66.7% (61.5%) 22.2% (20.5%)5.5% (5.1%)5.5% (5.1%)Embryonal rhabdo: (7.8%) | 68.5% (56.5%)19.9% (16.7%)11.6% (9.7%)Embryonal rhabdo: (2.8%)Dermoid tumour: (1.4%) |

Figure 1. Prevalence of Schistosomiasis and Predominant Bladder Histotypes and the distribution of Tobacco and Petrochemical Industries in Nigeria.

Table 5. Causative factors for Urothelial Carcinoma [4].

| Inhalation | Cigarette Smoke* |

| Cooking Fumes* | |

| Industrial Carcinogens* | |

| Coal tar pitch volatiles (CTPVs)* | |

| Diesel and Gasoline Exhausts* | |

| Methenamine vapor* | |

| Insecticides and pesticides* | |

| Drugs | Cyclophosphamide |

| Chloronaphazine | |

| Phenacetin* | |

| Nitrosamines* | |

| Herbal remedies especially those containing aristolochic acid (AA) | |

| Contact | Chlorinated water* |

| Hair dyes* | |

| Clothing dyes* | |

| Diet | Chemical contaminants especially Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) including benz[a]anthracene, banzo[b]fluoranthene, benzo[k] fluoranthene, benzo[g, h, i]perlene, benzo[α]pyrene, benzo[e]pyrene, dibenz[a,h]anthracene and indenol[1,2,3-c,d]pyrene |

| Bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum) | |

| Coffee and alcohol* | |

| Arsenic | |

| Endogenous Carcinogens | Tryptophan Metabolites |

| Infections | Viruses e.g. polyomaviruses (BKV and JCV), human pappilomas virus (HPV)* |

| Cystitis | |

| Schistosomiasis* | |

| Hereditary Factors | NAT1 and NAT2 acetylator genotypes |

| Mutations in the H-ras gene | |

| OncogenecerbB- 2 | |

| Mutation in p53 | |

| Tumor suppressor genes, cdkn2 and Rb | |

| bcl-2, c-myc, and EGFR | |

| ki-67 | |

| Xanthine oxidase (XO), fructsoamine, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), hydroxyproline, immnuoglobin E (IgE), and TNF-α | |

| Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3), CNKN2A, PIK3CA, Rb1and TP53 mutations | |

| Note * - Denotes factors that may play a role in the development of urothelial carcinomas in Nigeria. | |

In our cohort of bladder cancers the male to female ratio was 3.1:1. This is similar to the findings from several previous studies from Nigeria 9-11, 13,14, 16, 17 and the worldwide ratio of 3.5:1 1. Despite this, the disease occurred at a significantly younger age in females as compared to males in UC and SCC. Although other studies have previously reported that SCC occurs at a younger age in women 5, this is the first report of a similar finding in UC and suggests the possibility of additional female risk-factors for bladder cancers in our locality. Factors previously considered are poorer treatment of the disease in women and increased susceptibility to schistosoma-induced bladder cancers 5. Also important are the poor nutritional and health status of African women 19 which would reduce their immune resistance generally, and the exposure African women to several of the identified domestic and environmental causative factors of UC when cooking and at work as petty traders (selling insecticides, pesticides e.t.c.) and in the clothing dye industry (handling aniline dyes) 20,21. We postulate that these factors, and others presently unknown, are relevant in the early development of both SCC and UC in women in Southwest Nigeria.

In the United States, approximately 80% of newly diagnosed cases of bladder cancers occur in people aged 60 years and older, and the incidence increases with age 12. In contrast, 80% of new cases in our series were diagnosed from the 5th decade onwards. The mean ages of occurrence in our patients (in the sixth decade) were also lower but were comparable to findings described by most previous studies from Nigeria 10, 11, 14, 16, 18. Studies from Egypt have consistently reported that the peak age of occurrence for schistosoma-associated SCC is significantly lower than those for non schistosoma- associated cancers 3, 5,17,22, whilst in South Africa, SCC is reportedly more common among African patients who were a mean of more than 20 years younger than Caucasians 23. We found similarly that the peak, mean and median ages of occurrence was significantly lower for SCC than it was for the entire cohort. Importantly, other studies from Nigeria with relatively lower overall peak age range for bladder cancer also showed a higher frequency of SCC relative to UC 9-11, 14.

It has been recommended that tumours with any identifiable urothelial element be classified as UC, with the diagnosis of SCC and AC being reserved for pure lesions without any identifiable urothelial element, including urothelial carcinoma-in-situ 1. However, with small cell carcinoma, the finding of even focal small cell differentiation is known to be associated with a poor prognosis and has different therapeutic ramifications, and thus should be diagnosed as small cell carcinoma. In this study a small proportion of the bladder carcinomas in this study (2%) that had initially been diagnosed as mixed carcinoma were re-classified as UC on further evaluation as they included urothelial components. This differs from an earlier study from the Middle Belt region of Nigeria 9 where 15.8% of the cases studied were mixed carcinomas that would require re-classification which could further increase the high incidence of UC recorded in that study.

Of interest is the fact that AC accounted for 11.6% of bladder carcinomas in our study, with the majority being mestatatic in keeping with established epidemiology 1.This is higher than that (2.2%) found in the earlier study from our centre 15 but similar to that reported of Zaghloul et al 24 who had reported that AC of the bladder occurs more frequently in schistosoma-endemic areas. Groeneveld et al 23 had also suggested an association between AC of the bladder and schistosomiasis. We are therefore of the opinion that, along with the relatively high prevalence of SCC, this finding may be further evidence of the persistence of low level schistosoma endemicity in our environment.

Implications of our study for prevention and treatment of bladder cancer in Nigeria

Ibadan is the third largest city in Nigeria 15 and along with its environs has the largest homogenous population of native Africans in the sub-Sahara. The Ibadan Cancer Registry sub-serves the city and its environs and thus provides reliable information on cancers diagnosed in a sizeable portion of the population of southwest Nigeria. Accordingly, the findings of this study can be expected to be representative of the indigenous population southwestern region of the country. The findings of this study contribute to knowledge about bladder cancers in Nigeria with significant implications for strategies directed at the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of the malignancy, and the training of health professionals in the country. These include:

-

1

Bladder cancer epidemiology and the geography of schistosoma endemicity and control in Nigeria – Taken along with reports from other parts of the country, our findings confirm the presence of two distinct geography-dependent histologic patterns for bladder cancer in Nigeria with UC being predominant in the middle belt and southern regions whilst SCC is the more common in the far north of the country (Figure1) 25,26. Following Fergusson’s first report of the possibility of a causal relationship between urinary schistosomiasis and bladder cancer in Egypt in 1911 27 the pathogen is now classified as a class 1 oncogen 28. Similarly, smoking and home and industrial carcinogens are recognized as pathogens for UC and SCC 3,6. Expectedly, our findings mirror the distribution of schistosomiasis and urban and industrial development in the country with SCC predominating in the north where the prevalence of schistosmiasis is highest 29, and UC predominating in the middle belt and southern regions where control of the schistosomiasis is more effective (thus reducing long-term complications such as SCC) and urbanization and the concentration of carcinogen producing factories is highest.

-

2

Strategies for prevention and treatment of bladder cancer – The two-zone bladder cancer epidemiology and schistosoma endemicity described above indicates that policies/guidelines for bladder cancer control have to be geographic area specific to be effective. In this regards, measures such as public enlightenment and health education, improved water supply and sanitation, and more specific measures such as the elimination of the parasite by snail control, early detection and mass therapy of infected populations 22 are required in the North. In the middle-belt and southern regions however, public health strategies for the control of tobacco distribution and smoking, and for limiting contact with environmental and other carcinogens whilst maintaining policies directed at schistosoma control, are more important. Nation-wide strategies aimed at the prevention, early diagnosis and treatment of bladder cancers in women are of prime importance to reduce the higher relative morbidity and mortality of the disease in this gender. Further, research efforts are also required urgently to identify the factors responsible for the lower ages of occurrence of all bladder cancer histotypes in women in our community.

-

3

Strategies for the pathological diagnosis of bladder cancer – Schistosoma-associated SCC is more likely to present late and at advanced stages with detrusor muscle invasion than non-schistosoma associated bladder cancer (NSABC) 3 which are more likely to be superficial at presentation. As such, whilst both types of bladder cancer can be diagnosed by biopsies which are invasive, NSABC are more exfoliative and are more readily diagnosed with non-invasive urine cytology. Pathologists therefore need to be trained in, and the pathology laboratories equipped for, urine cytology. This should be in addition to upscaling the laboratories to enable them make histological diagnosis from samples obtained with the smaller biopsy forceps currently being used to reduce the morbidity associated with the procedure.

Strategies for the clinical diagnosis and treatment of bladder cancer – Currently 70-80% of patients presenting with newly diagnosed bladder cancer in developed nations present with non muscle-invasive cancer, most patients in developing nations present with advanced disease30. Since UC is more likely to present early and at a potentially curable stage, it is important that health-care professionals in Sub-Saharan Africa be trained to recognize its early symptoms (especially haematuria) and therefore refer affecteds immediately for specialist evaluation. This is particularly important in women who are often treated empirically for urinary tract infections and discharged only to represent later with more advanced disease. Further, patients presenting with early/non-invasive disease are best treated with bladder-sparing regimes (i.e. endoscopic or rarely partial cystectomy) (or partial cystectomy) with adjuvant intra-vesical chemo/immune-therapy with good outcomes 31. This treatment modality, with without neo-adjuvant radiotherapy may also be suitable in selected patients with muscle-invasive disease 32. As such, emphasis should be placed on training urologists in endoscopy and the necessary equipment made available in hospitals in the country. Also, chemo/immunotherapeutic agents which are currently scarce and very expensive in Nigeria, need to be made available at least in major centres to enable these surgeons offer best practice to their patients.

Strengths and limitations of our study

This study reports on the largest cohort of bladder cancer in sub-Saharan Africa collected systematically over the longest duration to date. This, along with the fact that the data was collected prospectively, strengthens the validity of the findings. Despite this, the retrospective analysis of the data and the lack of clinical details for correlation with the histopathological indices limited the epidemiological conclusions (particularly as regards natural biology and prognosis) that could be drawn from the study.

Significantly, we were unable to explain our novel finding of a lower median age of occurrence of UC in females. Although a lower age of occurrence of SCC in males and more so in females have previously been reported in SCC 5, no definitive reason was given. Whilst similar factors may be at play in both carcinomas, we believe further studies are required to delineate these clearly.

Conclusions

This is the largest series on bladder cancer from Nigeria and it shows that UC has become significantly more common than SCC overall across all age groups and in both gender. Also, both UC and SCC occur earlier in women. Public health initiatives should be directed at reducing smoking habits, the use of pesticides/insecticides and exposure to petrochemicals in Southern Nigeria whilst maintaining efforts to control schistosomiasis which remains the primary focus in Northern Nigeria. Efforts should also be made to identify and address the factors responsible for the lower ages of occurrence of UC and SCC in women. These findings also have implications for the training of relevant health professionals to enable them diagnose and treat this malignancy in its early stages and thus reduce the high morbidity and mortality associated with advanced disease.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge with appreciation the efforts of Dr. C.A. Okolo (Department of Pathology, UCH) with the retrieval of the data from the Ibadan Cancer Registry. Also the efforts of Mr. Temitope Adedeji, Research Fellow, PIUTA Ibadan Centre, Department of Surgery, University of Ibadan for his assistance with preparing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Grant support: None

References

- 1.World Health Organization Geneva. Chapter II, Tumours of the Urinary System. In: Eble JN, Sauter G, Epstein JI, and Sesterhenn IA, editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours,Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rambau PF, Chalya PL, Jackson K. Schistosomiasis and urinary bladder cancer in North Western Tanzania: a retrospective review of 185 patients. Infect Agent Cancer. 2013;8(1):19–24. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-8-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung KT. The Etiology of Bladder Cancer and its Prevention. J Cancer Sci Ther. 2013;5:343–361. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parkin DM, Whelan SL, Ferlay J, Teppo L, Thomas DB. IARC Scientific Publications. Vol. 155. Lyon: IARC Press; 2003. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng Y-L, Amr S, Saleh DA, Dash C, Ezzat S, Mikhail NN, Loffredo CA. Urinary bladder cancer risk factors in Egypt: a multi-center case-control study. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention : A Publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, Cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2012;21(3):537–546. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khaled H. Schistosomiasis and cancer in Egypt: review. J Adv Res. 2013 Sep;4(5):461–466. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mandong BM, Iya D, Obekpa PO, Orkar KS. Urological tumours in Jos University Teaching Hospital (a Hospital-based Histopathological study). Nig J of Surg Res. 2000;2(3):108–113. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Attah EB, Nkposong EO. Schistosomiasis and carcinoma of the bladder: a critical appraisal of causal relationship. Trop Geogr Med. 1976;28:268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Obafunwa JO. Histopathological study of vesical carcinoma in Plateau State, Nigeria. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1991;17(5):489–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ochicha O, Alhassan S, Mohammed AZ, Edino ST, Nwokedi EE. Bladder cancer in Kano- a histopathological review. West Afr J Med. 2003;22(3):202–204. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v22i3.27949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eni UE, HU Na’aya., Nggada HA, Dogo D. Carcinoma of the urinary bladder in Maiduguri: The Schistosomiasis Connection. Inter J of Oncol. 2008;5(2):1. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Society American. Cancer Facts and Figures 2002. 2002. http://www.uhmsi.com/docs/CancerFacts&Figures2002.pdf http://www.uhmsi.com/docs/CancerFacts&Figures2002.pdf

- 13.Aghaji AE, Mbonu OO. Bladder tumours in Enugu, Nigeria. Br J Urol. 1989;64(4):300–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1989.tb06051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas JO, Onyemenen NJ. Bladder carcinoma in Ibadan, Nigeria: a changing trend? East Afr Med J. 1995;72(1):49–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Federal Republic of Nigeria Official Gazette . 4. Vol. 94. Lagos: 2007. Jan 19, p. B52. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anunobi CC, Banjo AA, Abdulkareem FB, Daramola AO, Akinde OR, Elesha SO. Bladder cancer in Lagos: a 15 year histopathologic review. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2010;17(1):40–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mungadi IA, Malami SA. Urinary bladder cancer and schistosomiasis in North-Western Nigeria. West Afri J Med. 2007;26(3):226–229. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v26i3.28315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaaban AA, Orkubi SA, Said MT, Yousef B, Abomelha MS. Squamous cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Ann Saudi Med. 1997;17(1):115–119. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1997.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ene-Obong HN, Enugu GI, Uwaegbute AC. Determinants of health and nutritional status of rural Nigerian women. J Health Popul Nutr. 2001;19(4):320–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Little PD. A Research Paper prepared for the Broadening Access and Strengthening Input Market Systems-Collaborative Research Support Program (BASIS-CRSP). New York.: Institute for Development Anthropology Binghamton,; 2000. Selling to eat: petty trade and traders in per-urban areas of sub-Saharan African. ; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skinner C. Street trade in Africa: a review. Women in informal employment globalizing and organizing (WEIGO) Working Paper. 2008. pp. 1–25.

- 22.Abdulamir AS, Hafidh RR, Kadhim HS, Abubakar F. Tumor markers of bladder cancer: the schistosomal bladder tumors versus non-schistosomal bladder tumors. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2009;25(28):27. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-28-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Groeneveld AE, Marszalek WW, Heyns CF. Bladder cancer in various population groups in the greater Durban area of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Br J. Urol. 1996;78(2):205–208. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1996.09310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zaghloul MS, Abdel Aziz S, Nouh A, Mohran TZ, El-ShazelySand Saber A. Primary Adenocarcinoma of the Urinary Bladder: Risk Factors and Value of Postoperative Radiotherapy. J. Egypt. Nat. Cancer Inst. 2003;15(3):193–200. [Google Scholar]

- 25.2015. Aug 21, http://vconnect.com/nigeria/list-of-petrochemical-industry_c481 http://vconnect.com/nigeria/list-of-petrochemical-industry_c481

- 26.2015. Aug 21, http://vconnect.com/nigeria/list-of-tobacco-company-qsearch http://vconnect.com/nigeria/list-of-tobacco-company-qsearch

- 27.Ferguson AR. Associated bilharziasis and primary malignant disease of the urinary bladder with observations on a series of forty cases. J Path Bact. 1911;16(76):94. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ray D, Nelson TA, Fu C-L, Patel S, Gong DN, Odegaard JI, Hsieh MH. Transcriptional Profiling of the Bladder in Urogenital Schistosomiasis Reveals Pathways of Inflammatory Fibrosis and Urothelial Compromise. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2012;6(11):e1912. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oladejo SO, Ofoezie IE. Unabated schistosomiasis transmission in Erinle River Dam, Osun State, Nigeria: evidence of neglect of environmental effects of development projects. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11(6):843–850. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zaghloul MS. Bladder cancer and schistosomiasis. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2012;24(4):151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jnci.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharma S, Ksheersager P, Sharma P. Diagnosis and treatment of bladder cancer. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80(7):717–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hafeez S, Horwich A, Omar O, Mohammed K. Selective organ presentation with neo-adjuvant chemotherapy for the treatment of muscle invasive transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Br J. Canc. 2015 Dec;112(10):1626–1635. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]