Abstract

Background

The objective of this study was to evaluate how different measures of adiposity are related to both arterial inflammation and the risk of subsequent cardiovascular events.

Methods and Results

We included individuals who underwent FDG PET/CT imaging for oncological evaluation. Subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) volume, visceral adipose tissue (VAT) volume and VAT/SAT ratio were determined. Additionally BMI, metabolic syndrome (MetS), and, aortic FDG uptake (a measure of arterial inflammation) were determined. Subsequent development of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events was adjudicated. The analysis included 415 patients with a median age of 55 (P25–P75: 45–65) and a median BMI of 26.4 (P25– P75: 23.4–30.9) kg/m2. VAT and SAT volume were significantly higher in obese individuals. VAT volume (r=0.290, p<0.001) and VAT/SAT ratio (r=0.208, p<0.001) were positively correlated with arterial inflammation. 32 subjects experienced CVD event during a median follow-up of 4 years. Cox proportional hazard models showed that VAT volume, and VAT/SAT ratio were associated with CVD events (hazard ratio, HR (95% CI): 1.15 (1.06–1.25, p<0.001; 3.60 (1.88–6.92), p<0.001 respectively). BMI, MetS and SAT were not predictive of CVD events.

Conclusions

Measures of visceral fat are positively related to arterial inflammation and are independent predictors of subsequent CVD events. Individuals with higher measures of visceral fat as well as elevated arterial inflammation are at highest risk for subsequent CVD events. The findings suggest that arterial inflammation may explain some of the CVD risk associated with adiposity.

Keywords: obesity, positron emission tomography, cardiovascular events, adipose tissue, atherosclerosis

The increasing prevalence of obesity and the associated complications are a major health concern.1, 2 Obesity has been linked to cardiovascular disease (CVD) morbidity and mortality.3–5 However, clinical studies demonstrated that not all obese individuals are at high-risk for CVD, and it has been postulated that a subpopulation of obese but metabolically healthy individuals have a reduced risk for CVD.6, 7 The metabolic syndrome (MetS) represents a cluster of metabolic abnormalities that are associated with a substantially increased risk of CVD.6, 8, 9 Traditionally, obesity is determined based on body mass index (BMI) which represents an important predictor of CVD. However, imaging measures of visceral adipose tissue (VAT) explain a greater part of the variation in metabolic risk factors and are more strongly associated with abnormal metabolic profile beyond BMI.10 One potential biological link between VAT and atherosclerosis relates to immune regulation.11, 12 Adipocytes and adipocyte-related macrophages release inflammatory cytokines, which induce insulin resistance, endothelial dysfunction, and hypercoagulability, all of which promote atherosclerosis.13–15 Consistent with the proposed inflammatory link, several studies have identified an association between VAT volume and elevated levels of circulating inflammatory biomarkers.16–18 In addition, the ratio between VAT and subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT), a measure of relative body fat composition, has been associated with increased cardiometabolic risk.19

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) allows for non-invasive evaluation of aortic wall inflammation, which predicts future CVD events.20–23 Accordingly, aortic FDG uptake acts as an imaging biomarker for atherosclerotic plaque inflammation. The aim of this study was to evaluate how different measures of adiposity are related to both arterial inflammation and the risk of subsequent cardiovascular events.

Methods

Study Population

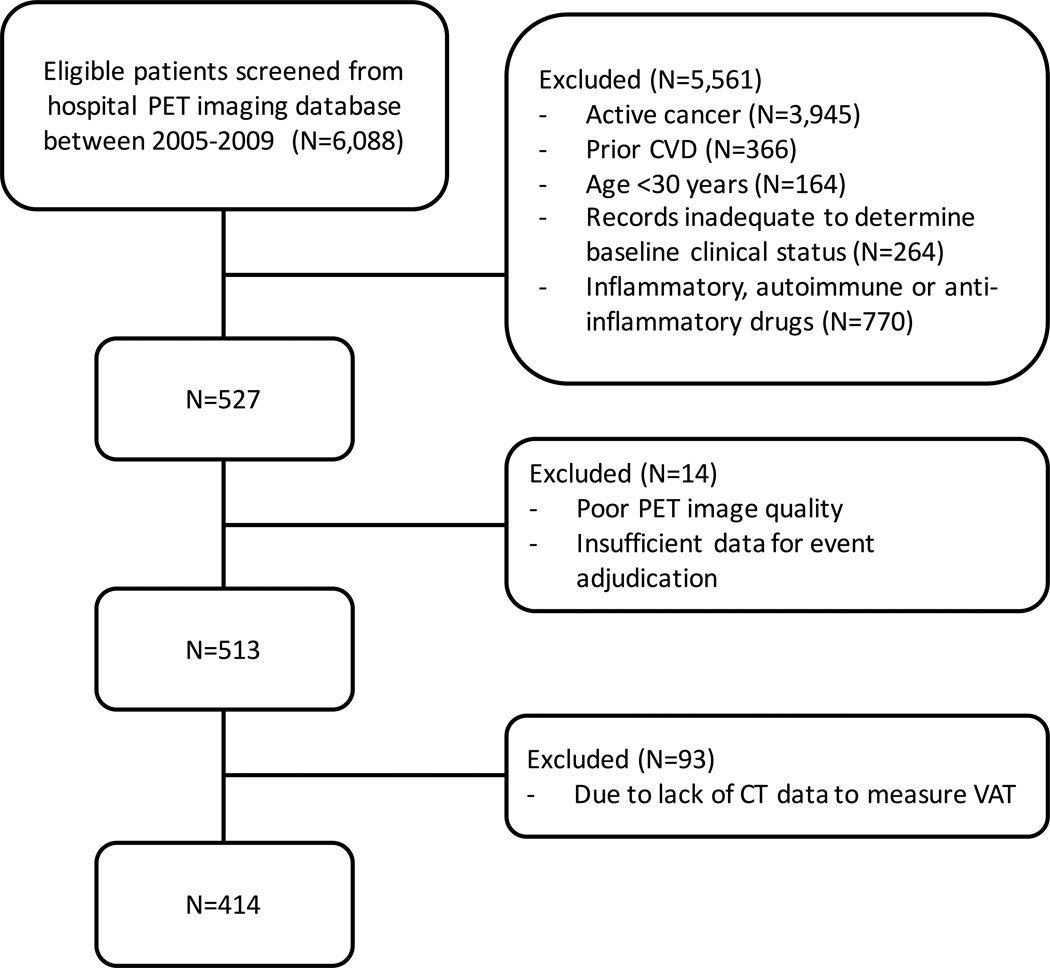

A total of 415 subjects who underwent 18F-FDG-PET and computed tomography (CT) imaging for oncological evaluation at the Massachusetts General Hospital between 2005–2008 were retrospectively identified and included in the final analysis if clinical follow-up information was available for at least 3 electronic medical records of 1 year apart (Figure 1). Pre-defined inclusion criteria included: 1) >30 years of age, 2) absence of prior cancer diagnosis or remission from cancer at the time of PET imaging and throughout the follow-up period, and 3) absence of CVD or acute or chronic inflammatory or autoimmune disease at time of imaging. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria for this population have been previously published.20 The study protocol was approved by the local human research committee.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study design

Data Collection

Review of medical records within Partners HealthCare was performed to extract patient data. Height and weight at the time of FDG-PET imaging were used to calculate BMI (kg/m2). Traditional CVD risk factors such as age, gender, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes and statin therapy were collected. High and low density lipoprotein, triglycerides, and total cholesterol were recorded. Additionally, fasting glucose (within 6 months of PET imaging) was noted. Framingham Risk Score (FRS) for 10-year general CVD risk was calculated.24 MetS was defined based on the presence of 3 or more of the following characteristics: a.) BMI>26.7 kg/m2 b.) elevated triglycerides: ≥ 150 mg/dl; c.) reduced HDL: men, < 40 mg/dl and women, <50 mg/dl; d.) elevated blood pressure: ≥ 130/85 mmHg; e.) elevated fasting glucose: ≥ 100 mg/dl, as adapted from the Adult Treatment Panel III25 using the method of Ridker et al.26.

Outcome data

CVD outcomes were defined similar to the Framingham Heart Study.24 Two cardiologists, who were blinded to all imaging data, used clinically available records to adjudicate events as follows: incident stroke or transient ischemic attack, acute coronary syndrome (unstable angina, non-ST elevation and ST elevation myocardial infarction), revascularization (coronary, carotid, or peripheral), new-onset angina, peripheral arterial disease, heart failure, or CVD death. Follow-up was measured from the subjects’ index FDG-PET imaging to the development of a CVD event or until the latest clinical follow-up recorded as of May 8, 2012.

PET/CT Imaging Protocol

FDG-PET imaging was performed using a Biograph 64 (Siemens, Forchheim, Germany) as per clinical protocol after intravenous administration of approximately 10 mCi of FDG, with patients imaged in the supine position over 15–20 minutes. PET images were acquired approximately 60 minutes after FDG administration. Prior to PET imaging a non-gated, non-contrast enhanced CT (120 kV, 50 mAs) was acquired.

Imaging Measures of Adipose Tissue Volume and Metabolism

Fat volumes were measured by an investigator (M.H.M) who was blinded to the clinical data and arterial measurements. Abdominal VAT and SAT volumes were measured as previously described using CT scans, which takes an average of 5 minutes per scan to quantify and demonstrated excellent inter- and intra-reader reproducibility (intra-class correlation coefficient=0.99).27 Patients were not analyzed if the abdomen was outside the scan range. Briefly, VAT and SAT volumes were measured using a dedicated offline workstation (Siemens Medical Solutions, Forchheim, Germany) and VAT/SAT ratio was calculated. Adipose tissue was identified using a threshold between −195 and −45 Hounsfield units (HU). The abdominal muscular wall was used as a boundary to separate VAT and SAT volumes. The volume was measured across all axial slices and was expressed as cm3.

An assessment of VAT activity (VAT FDG uptake) was performed in order to derive the metabolic activity within VAT. However, measurement of FDG uptake adjacent to the intestines was not feasible, due to substantial spill-over of activity from the intestines. Accordingly, the VAT FDG measurement could only be performed within the retroperitoneal space, far from intestinal spill-over. To obtain VAT SUV, a region of interest was drawn within a small region of VAT tissue, anterior to the aorta, (as close to the midline as possible). Subsequently, target-to-background ratio (VATTBR) was calculated by dividing VATSUV by the venous SUV. Additionally, to derive an approximation of the total biological activity of VAT, the VATSUV was multiplied by the VAT volume to generate a VAT Activity-Volume Product (VATAVP).

Imaging Measures of Arterial Inflammation by PET/CT

Analysis of the PET data for arterial activity was performed by a separate investigator (A.A) according to previously described highly reproducible methods.20, 28, 29 FDG uptake was measured within the ascending aortic wall and superior vena cava as standardized uptake value (SUV). Subsequently, target-to-background ratio (TBR) was calculated by dividing the average of SUVmax over all axial slices by the venous SUV.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous parametric variables, median (Percentile 25-Percentile 75) for continuous non-parametric data and frequency with proportions for categorical variables. Natural logarithmic transformation was performed to reduce departures from normality of VAT/SAT ratio and VATAVP. For group comparison of continuous variables, Student's t-test for independent samples was used for parametric in combination with Levene's test for equality of variances and Mann-Whitney U for non-parametric data. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves with area under the curve (AUC) were obtained to compare discriminatory strength of the variables. To assess correlation, Pearson’s Correlation was used. Kaplan-Meier estimates of event-free survival (for CVD events) were generated by dichotomizing values above or below median values and log rank tests were performed. Cox Proportional Hazards Regression was used to calculate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence interval. Proportional hazards assumption was tested based on the Schoenfeld residuals and assumptions of linearity were tested using Martingale residuals with Stata (StataCorp, version 13.1, StataCorp, College Station, Texas). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (IBM Corp, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

We included 415 patients with a median age of 55 (45–65) years and 42.7% males. Baseline characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Subjects

| Characteristics | Full cohort (n=415) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 55 (45–65) |

| Male (%) | 177 (42.7) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.4 (23.4–30.9) |

| MetS* | 63 (30.6) |

| Current smoker (%) | 42 (10.1) |

| Diabetes Mellitus (%) | 35 (8.4) |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 113 (27.2) |

| Statin use (%) | 78 (18.8) |

| Hypertension (%) | 142 (34.2) |

| Prior history of cancer | 357 (86.0) |

| Cardiovascular event (%) | 32 (7.7) |

| Framingham Risk Score** | |

| Low (10-y risk <10%) | 109 (51.7) |

| Medium (10-y risk 10%–20%) | 51 (24.2) |

| High (10-y risk >20%) | 44 (20.9) |

Values are mean (SD), median (P25–P75), or n (%). BMI denotes body mass index. MetS denotes metabolic syndrome

available in 206 patient,

available in 211 patients

BMI and MeTS

Median BMI was 26.4 (23.4–30.9) kg/m2 in our population. BMI showed a moderate correlation with aortic TBR (Table 2). Additionally, the components of MetS were evaluable in 206 (50.4%). MetS was present in 63 (15.2%) individuals. In patients with MetS, aortic TBR was significantly elevated (2.1±0.34 vs. 2.0±0.29, with vs. without MetS, p= 0.034).

Table 2.

Pearson correlation between arterial inflammation and adiposity measures

| Characteristics | Aortic TBR |

P value |

|---|---|---|

| BMI | 0.313 | <0.001 |

| SAT volume | 0.162 | <0.001 |

| VAT volume | 0.290 | <0.001 |

| VAT/SAT ratio | 0.208 | <0.001 |

| VATAVP | 0.180 | <0.001 |

SAT volume

SAT volume was greater in obese individuals (139.5±51.1 vs. 68.9±32.9, obese vs. non-obese individuals, p<0.0001) and in individuals with MetS (117.9±58.2 vs. 96.6±53.5, with vs. without MetS, p=0.011). No significant difference was observed between genders (107.9±61.4 vs. 99.3±45.7, females vs. males, p=0.105). Pearson correlation between BMI and SAT volume was significant (r=0.789, p<0.001). We also observed a weak correlation between SAT volume and aortic TBR (r=0.162, p<0.001), which did not remain significant after correcting for VAT volume (r=0.019, p=0.703). VAT and SAT volume were significantly correlated (r=0.504, p<0.001).

VAT volume

VAT volume was greater in obese individuals (78.9±36.5 vs. 34.6±22.4, obese vs. non-obese individuals, p<0.0001) and in individuals with MetS (83.5±40.0 vs. 47.6±32.3, with vs. without MetS, p<0.0001). A significant difference was observed in the amount of VAT between genders (46.5±32.2 vs. 70.8±39.6, females vs. males, p<0.001). Pearson correlation between BMI and VAT volume was significant (r=0.660, p<0.001). A modest correlation was observed between VAT volume and aortic TBR (r=0.290, p<0.001), similar to that between BMI and aortic TBR (r=0.313, p<0.001). The correlation between VAT volume and aortic TBR remained significant after adjusting for SAT volume (r=0.245, p<0.001)

VAT/SAT ratio

VAT/SAT was greater in obese individuals (0.55 (0.37–0.81) vs. 0.50 (0.30–0.70), obese vs. non-obese individuals, p=0.006) and in individuals with MetS (0.69 (0.52–0.95) vs. 0.48 (0.29–0.67), with vs. without MetS, p<0.001). Pearson correlation between BMI and VAT/SAT ratio was not significant (r=0.092, p=0.063). We also observed a weak correlation between VAT/SAT ratio and aortic TBR (r=0.208, p<0.001). VAT/SAT ratio was more strongly correlated to VAT (r=0.604, p<0.001) than SAT (r=−0.243, p<0.001).

VAT Activity

VATAVP was greater in obese individuals (43.5 (29.5–63.6) vs. 22.1 (14.1–30.2), obese vs. non-obese individuals, p<0.001) and in individuals with MetS (50.7 (31.8–65.7) vs. 27.4 (16.1–41.0), with vs. without MetS, p<0.001). There was a strong correlation between BMI and VATAVP, (r=0.639, p<0.001) and weaker one between aortic TBR and VATAVP (r=0.180, p<0.001). VATAVP was more strongly associated with VAT volume (r=0.878, p<0.001) than to VAT SUV (r=−0.234, p<0.001).

CVD Events

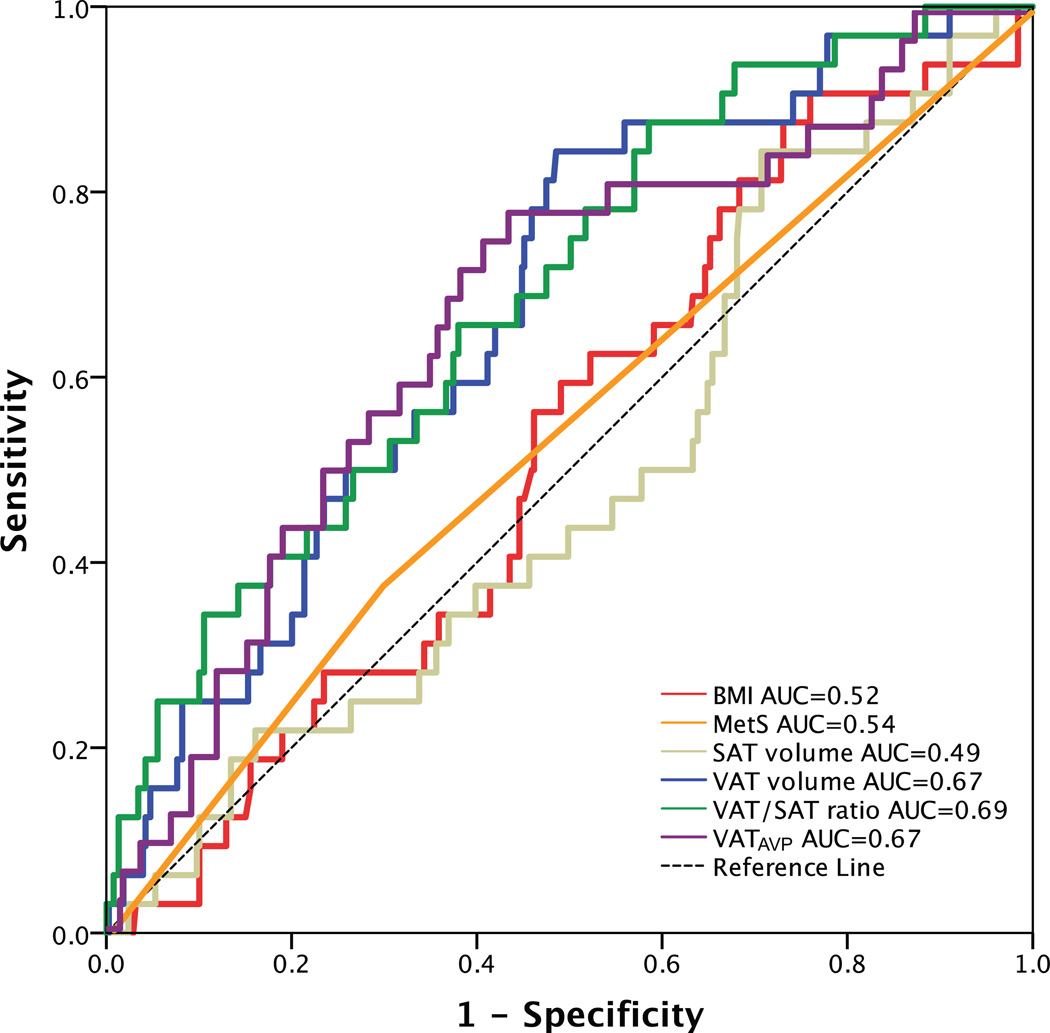

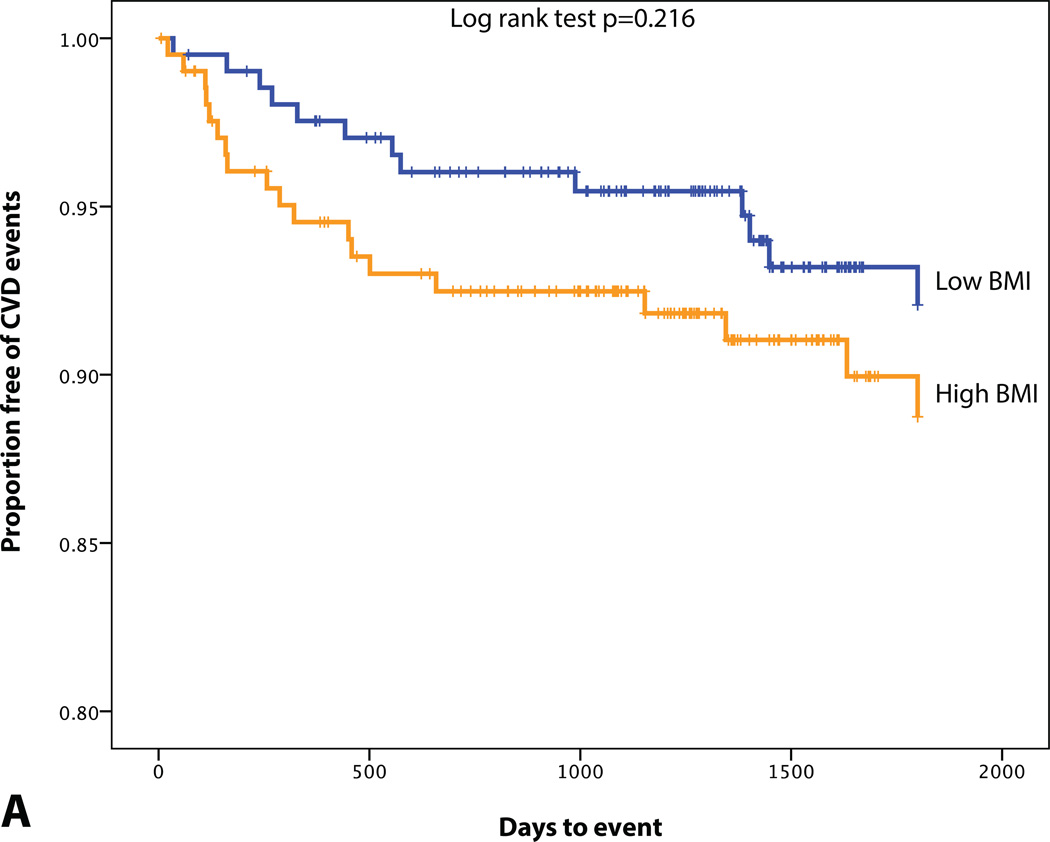

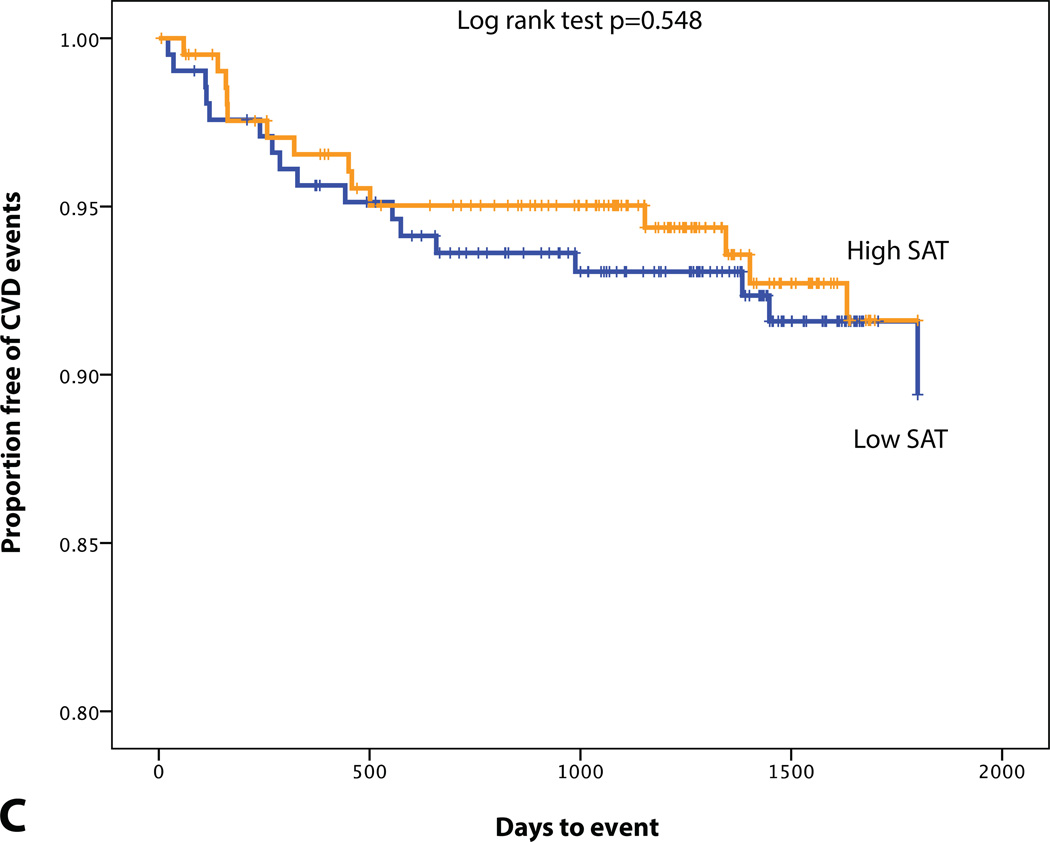

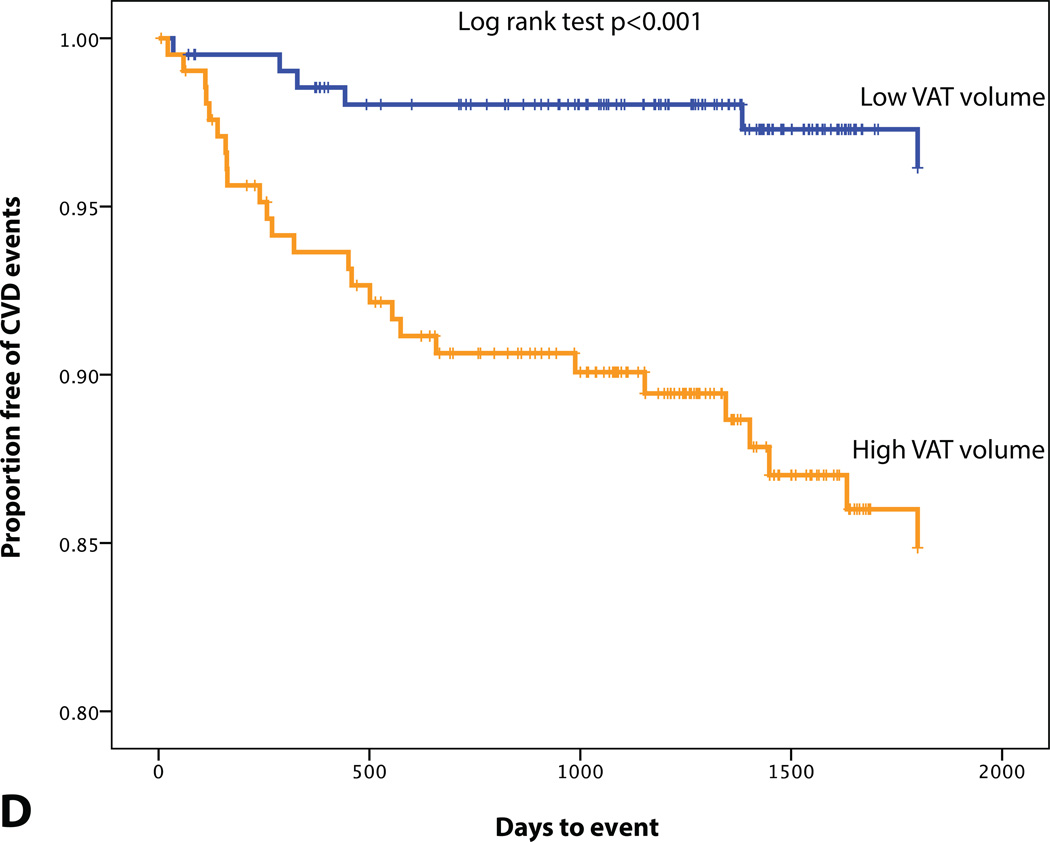

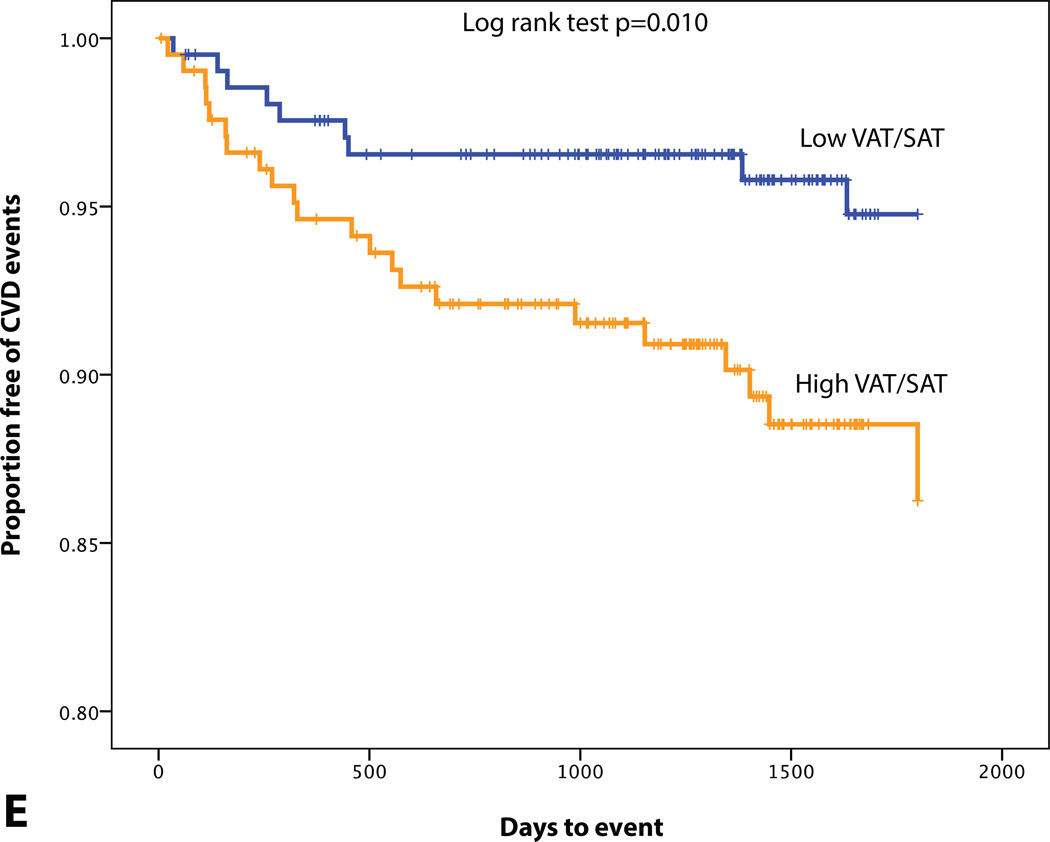

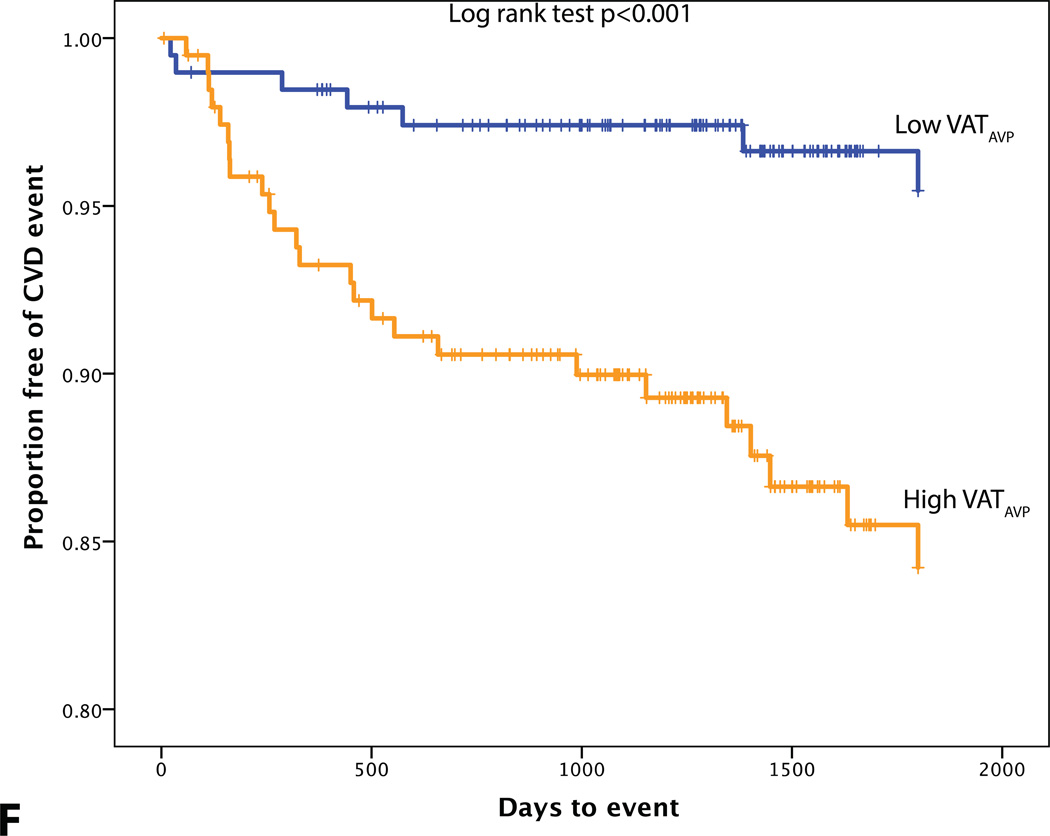

A total of 32 patients experienced CVD events over a median follow-up of 4 years. 10 developed acute coronary syndrome (8 acute myocardial infarctions and 2 unstable angina pectoris), 4 underwent percutaneous coronary revascularization, 7 had a stroke, 1 experienced a transient ischemic attack, 1 underwent carotid revascularization, 5 had new-onset angina pectoris, 3 were diagnosed with peripheral artery disease and underwent peripheral revascularization, and 1 cardiovascular death. Differences in BMI, VAT volume, VATAVP, SAT volume and aortic TBR between subjects with and without a CVD event are displayed in Table 3. ROC curve analysis also showed that VAT volume, VAT/SAT ratio and VATAVP were the strongest discriminators (Figure 2). VATTBR was found not to contain incremental prognostic information with a univariate hazard ratio of 1.10 (95% CI 0.22–5.64) and an AUC of 0.51. However, Cox proportional hazard models revealed that VAT volume, VAT/SAT ratio and VATAVP were significant predictors of subsequent CVD events (HR (95% CI): 1.15 (1.06–1.25), p<0.001; 3.60 (1.88–6.92), p<0.001, 2.38 (1.39–4.10), p<0.001 respectively). This remained significant after correcting for age, BMI and aortic TBR (all p<0.05) (Table 4). However, neither SAT volume, BMI nor the presence of MetS predicted CVD (Table 4, Figure 3). Adjusting for prior history of cancer did not have an effect on the significance of the HRs.

Table 3.

Differences in clinical parameters between subjects with and without a CVD event

| Characteristics | Full cohort (n=415) |

No CVD event (N=383) |

CVD event (N=32) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | 27.5±5.5 | 27.5±5.5 | 27.6±4.8 | 0.863 |

| SAT volume | 104.2±55.4 | 104.3±55.6 | 102.7±53.4 | 0.870 |

| VAT volume | 56.9±37.5 | 55.2±36.9 | 76.5±39.8 | 0.002 |

| VAT/SAT ratio | 0.52 (0.33–0.74) | 0.50 (0.31–0.72) | 0.69 (0.50–1.16) | <0.001 |

| VATAVP | 31.3 (20.8–49.1) | 29.6 (20.4–46.4) | 45.8 (33.2–64.6) | 0.002 |

| Aortic TBR | 2.0±0.3 | 2.0±0.3 | 2.2±0.3 | 0.001 |

Data are presented as mean±SD

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis of adiposity measures in predicting CVD events.

Table 4.

Predictors of CVD events using univariate and multivariate cox proportional hazard models

| Model covariates HR (95% CI) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Univariate | Age | Sex | FRS | BMI | MetS | Aortic TBR |

| MetS | 1.37 (0.67–2.81) |

1.07 (0.52–2.20) |

1.35 (0.66–2.79) |

1.14 (0.54–2.43) |

1.39 (0.64–3.00) |

NA | 1.20 (0.58–2.48) |

| BMI | 1.01 (0.95–1.07) |

1.02 (0.95–1.09) |

1.01 (0.95–1.08) |

0.99 (0.92–1.07) |

NA | 1.00 (0.93–1.07) |

0.97 (0.91–1.04) |

| SAT volume# | 1.00 (0.94–1.07) |

1.01 (0.94–1.08) |

1.00 (0.94–1.07) |

1.01 (0.94–1.08) |

0.98 (0.89–1.09) |

1.00 (0.94–1.07) |

0.98 (0.92–1.05) |

| VAT volume# | 1.15* (1.06–1.25) |

1.11* (1.01–1.21) |

1.16* (1.07–1.27) |

1.07 (0.97–1.18) |

1.26* (1.13–1.41) |

1.14* (1.04–1.26) |

1.12* (1.02–1.22) |

| VAT/SAT^ ratio |

3.60* (1.87–6.92) |

2.38* (1.16–4.88) |

4.13* (2.15–7.96) |

2.17* (1.04–4.50) |

3.63* (1.89–6.97) |

2.98* (1.60–5.56) |

3.11* (1.62–5.97) |

| VATAVP^ | 2.38* (1.39–4.10) |

1.81* (1.01–3.24) |

2.42* (1.41–4.16) |

1.78 (0.96–3.29) |

4.88* (2.29–10.39) |

2.36* (1.32–4.22) |

2.11* (1.23–3.61) |

| Aortic TBR | 7.33* (2.23–24.14) |

13.1* (3.62–47.04) |

8.09* (2.44–26.89) |

5.70* (1.65–19.66) |

8.80* (2.44–31.79) |

5.52* (1.68–18.14) |

NA |

Per 10 cm3P<0.05*, ^ Ln transformed.

Model covariates indicate for which variable the predictor was adjusted. Proportional hazards assumption and assumptions of linearity were met.

Figure 3.

KM plot displaying Proportion Free of CVD Events Stratified by (A) BMI (median=26.4 kg/m2), (B) MetS, (C) SAT volume (median=95.0 cm3), (D) VAT volume (median=48.4 cm3), (E) VAT/SAT ratio (median=0.52), and (F) VATAVP (median=31.3).

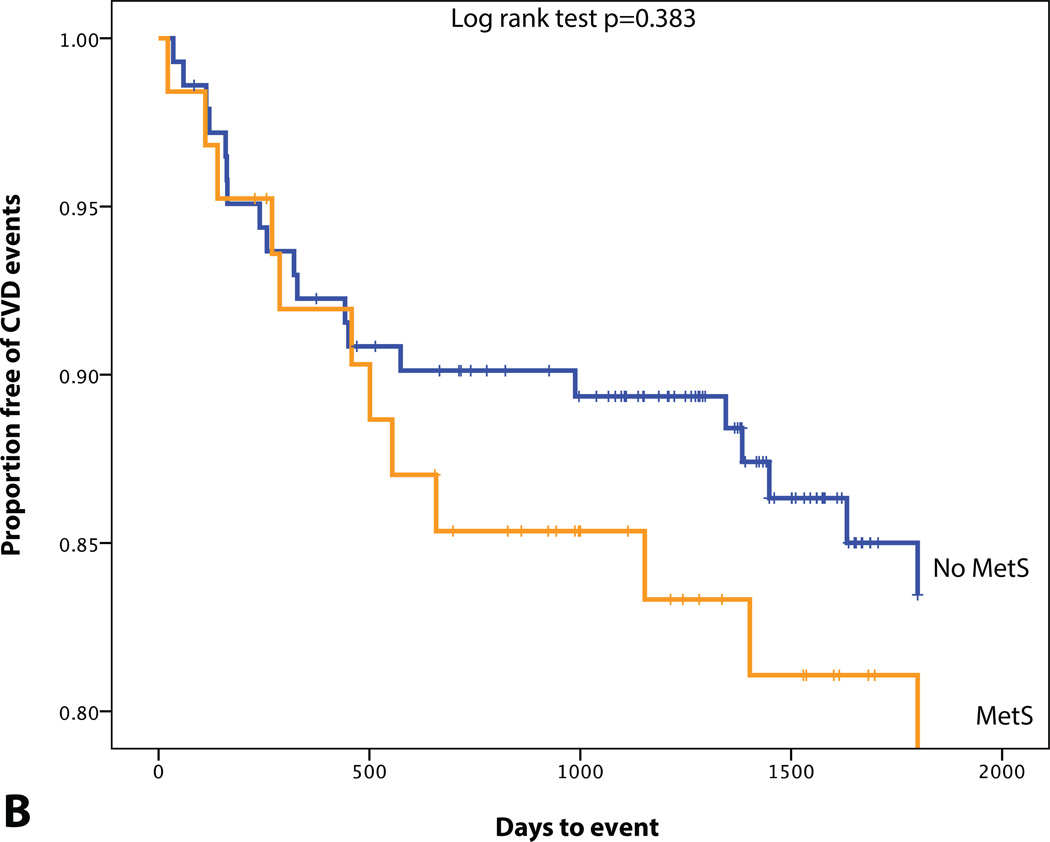

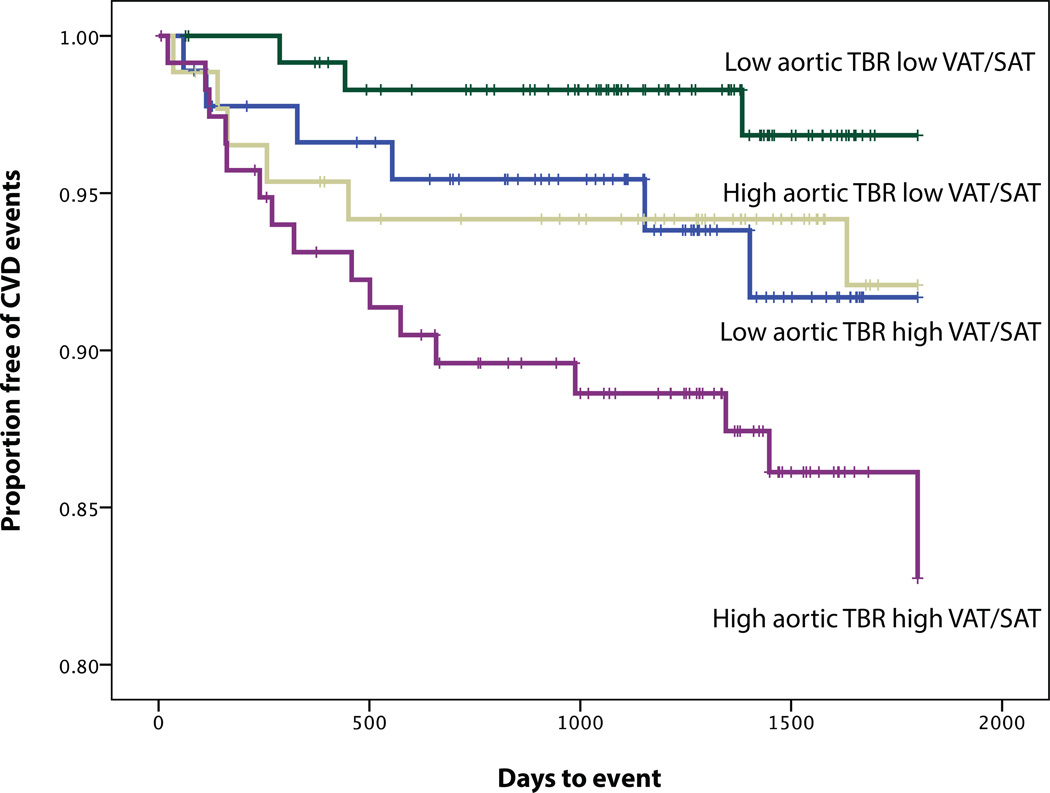

In this study, as previously noted, aortic inflammation (as TBR) was a potent predictor of CVD risk (Table 4). When evaluating both VAT volume and VAT/SAT ratio in a Cox proportional hazard model, only VAT/SAT ratio was found to be significant (HR (95% CI): 2.88 (1.30–6.40), p=0.005). Moreover, we observed that the combination of arterial inflammation and VAT/SAT ratio provided incremental risk discrimination. When individuals were classified according to high vs. low VAT/SAT ratio (dichotomized above or below median values) as well as high vs. low arterial inflammation (also dichotomized above or below median values), the subgroup with both high VAT/SAT ratio and high arterial inflammation did substantially worse than the others (Figure 4). Also when evaluating both VATAVP and VAT/SAT ratio in a Cox proportional hazard model, only VAT/SAT ratio was found to be significant (HR (95% CI): 2.62 (1.25–5.51), p=0.011).

Figure 4.

KM plot displaying Proportion Free of CVD Events Stratified by the combination of median TBR (median=2.0) and median VAT/SAT ratio (median=0.52). Pairwise log rank comparison showed that only the combination of high VAT/SAT and high aortic TBR was different from the other groups (using low aortic TBR and low VAT/SAT volume as the reference group, p=0.129, p=0.147, p=0.002).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate the association between measures of VAT, arterial inflammation and subsequent CVD events. VAT volume, VAT/SAT ratio and VATAVP correlated moderately with arterial inflammation, an independent predictor for CVD events.20 Moreover, we observed that VAT volume, VAT/SAT ratio and VATAVP were predictors for the occurrence of CVD events, independent of BMI or arterial inflammation. In addition, the observed link between VAT volume and arterial inflammation may explain some but not all of VAT's association with CVD events.

The relationship of VAT to metabolic complications is independent of the variation in total body fat, and as such, the assessment of CVD risk solely by measurement of BMI may be inadequate.10, 30–32 In our study, BMI was not found to be an independent predictor of CVD events. The potential reasons for this are multi-fold, and may be related to the distinct types of fat that might contribute to increased body mass. VAT compared to SAT is more metabolically active and regarded as pathogenic.33 VAT secretes pro-inflammatory mediators, including IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1, RANTES, MIP-1α, PAI-1.31 Fontana et al.34 detected higher IL-6 levels in the portal vein compared to peripheral artery and also observed a correlation between portal vein IL-6 concentration and systemic C-reactive protein concentrations, thus, providing evidence for a potential mechanistic link between VAT and systemic inflammation which plays an crucial role in the development of atherosclerosis.35 Though VATAVP was associated with events, it was not found to be independent of VAT/SAT ratio. This finding raises the possibility that the volume of VAT may be more important a predictor of VAT-associated diseases than the activity of VAT. However, it is also worth noting that in this study, VAT activity was measured in only a small region of interest (technical limitations due to spill-over of FDG activity from adjacent gut tissue made it infeasible to measure VAT activity throughout the entire VAT volume).

Buccerius et al.36 observed a significant correlation between adipose tissue FDG uptake and arterial FDG uptake in 173 patients with atherosclerosis. Further, Christen et al.37 demonstrated higher FDG uptake in VAT compared to SAT in humans. In a mouse model exploring the underlying mechanism, they observed higher FDG uptake in stromal tissue, which contain inflammatory cells.37 In concert with the pro-inflammatory nature of VAT, we found a moderate correlation between VAT volume and arterial inflammation (aortic TBR). Furthermore, in the current study, we found incremental prognostic value in VAT volume even after correcting for aortic TBR, thus suggesting that VAT tissue might predispose to CVD events via mechanisms that extend beyond its link to arterial inflammation.

We furthermore evaluated the relationship between VAT/SAT, arterial inflammation, and CVD events. VAT/SAT ratio reflects the propensity to store fat viscerally relative to subcutaneously. One possible theory is that excess energy is primarily stored in SAT, however when this depot is dysfunctional, energy can alternatively be stored in VAT.38 In the Framingham Heart Study VAT/SAT ratio was found to significantly correlate with cardiometabolic risk factors, beyond associations with BMI and VAT.19 In our study we observed that VAT/SAT ratio had a stronger correlation with VAT than SAT volume. Moreover, we found that VAT/SAT ratio also correlates with arterial inflammation and remained a significant predictor after correcting for FRS, beyond VAT volume.

Several limitations of the study should be noted. First, generalizability might be limited due to the highly selected nature of this patient population (primarily patients who had a prior history of treated cancer) and the relative small number of events. Though, in a previous study we found that aortic TBR contained prognostic information in both cancer survivors as well as cancer-naive individuals.20 Second, event adjudication was limited to information contained in the medical records, thus the possibility of event miss-classification exists. Third, prior research demonstrated the optimal time point for the evaluation of FDG uptake in the vascular wall is beyond 60 minutes, the arterial wall signals may be somewhat sub-optimal for assessment of arterial inflammation.39, 40 None-the-less, we and others have previously shown that circulation times such as those used in this population still result in tissue FDG uptake that provides an independent predictive value for subsequent CVD events.20, 41 Fourth, The data needed to calculate FRS and MetS was available for only half of the population, hence power to assess associations in that smaller group may have been constrained. However, despite this limitation, VAT/SAT remained a predictor of CVD events even in the smaller group who had the available data. Finally, the retrospective and observational design of this study does not allow us to infer causal relations.

In conclusion, we observed that measures of visceral fat mass and metabolism associate with arterial inflammation and predict future CVD events. These findings provide additional evidence for VAT volume and VAT/SAT ratio as imaging biomarkers for CVD risk. Further, the findings suggest that their association with arterial inflammation may explain some of the CVD risk associated with adiposity.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective.

Obesity is a major health concern due to increased risk of cardiovascular disease. However, not all obese individuals are at high-risk for cardiovascular events. Possibly a subpopulation of obese and metabolically diseased individuals are at highest risk for events and accurate identification of these patients could allow for better medical management (for example by reclassification of statin eligibility). In our study we observed that VAT volume and VAT/SAT ratio both were predictors for the occurrence of CVD events, independent of BMI or arterial inflammation. In addition, a link was observed between VAT volume and arterial inflammation, which could explain part of VAT's association with cardiovascular events.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Takx is supported by Van Leersum Grant of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. Dr Tawakol is a consultant for Actelion, Amgen, AstraZeneca, and Takeda and received research grants from Actelion, Genentech and Takeda. Dr. Grinspoon is a consultant for and received research grants from Theratechnologies, Gilead, Amgen, and served as a consultant for NovoNordisk, BMS, Merck, Navidea, Aileron.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2000;894:i–xii. 1–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. Jama. 2010;303:242–249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oda E. Obesity-related risk factors of cardiovascular disease. Circ J. 2009;73:2204–2205. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-09-0653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Logue J, Murray HM, Welsh P, Shepherd J, Packard C, Macfarlane P, Cobbe S, Ford I, Sattar N. Obesity is associated with fatal coronary heart disease independently of traditional risk factors and deprivation. Heart. 2011;97:564–568. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.211201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flint AJ, Hu FB, Glynn RJ, Caspard H, Manson JE, Willett WC, Rimm EB. Excess weight and the risk of incident coronary heart disease among men and women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:377–383. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogorodnikova AD, Kim M, McGinn AP, Muntner P, Khan U, Wildman RP. Incident cardiovascular disease events in metabolically benign obese individuals. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20:651–659. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meigs JB, Wilson PW, Fox CS, Vasan RS, Nathan DM, Sullivan LM, D'Agostino RB. Body mass index, metabolic syndrome, and risk of type 2 diabetes or cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2906–2912. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kip KE, Marroquin OC, Kelley DE, Johnson BD, Kelsey SF, Shaw LJ, Rogers WJ, Reis SE. Clinical importance of obesity versus the metabolic syndrome in cardiovascular risk in women: a report from the Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study. Circulation. 2004;109:706–713. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000115514.44135.A8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song Y, Manson JE, Meigs JB, Ridker PM, Buring JE, Liu S. Comparison of usefulness of body mass index versus metabolic risk factors in predicting 10-year risk of cardiovascular events in women. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:1654–1658. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.06.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fox CS, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, Pou KM, Maurovich-Horvat P, Liu CY, Vasan RS, Murabito JM, Meigs JB, Cupples LA, D'Agostino RB, Sr, O'Donnell CJ. Abdominal visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue compartments: association with metabolic risk factors in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2007;116:39–48. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.675355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansson GK, Libby P. The immune response in atherosclerosis: a double-edged sword. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:508–519. doi: 10.1038/nri1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsuzawa Y. Therapy Insight: adipocytokines in metabolic syndrome and related cardiovascular disease. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2006;3:35–42. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lau DC, Dhillon B, Yan H, Szmitko PE, Verma S. Adipokines: molecular links between obesity and atheroslcerosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H2031–H2041. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01058.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1685–1695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lim S, Despres JP, Koh KK. Prevention of Atherosclerosis in Overweight/Obese Patients. Circ J. 2011;75:1019–1027. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pou KM, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, Vasan RS, Maurovich-Horvat P, Larson MG, Keaney JF, Jr, Meigs JB, Lipinska I, Kathiresan S, Murabito JM, O'Donnell CJ, Benjamin EJ, Fox CS. Visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue volumes are cross-sectionally related to markers of inflammation and oxidative stress: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2007;116:1234–1241. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.710509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forouhi NG, Sattar N, McKeigue PM. Relation of C-reactive protein to body fat distribution and features of the metabolic syndrome in Europeans and South Asians. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:1327–1331. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park HS, Park JY, Yu R. Relationship of obesity and visceral adiposity with serum concentrations of CRP, TNF-alpha and IL-6. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005;69:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaess BM, Pedley A, Massaro JM, Murabito J, Hoffmann U, Fox CS. The ratio of visceral to subcutaneous fat, a metric of body fat distribution, is a unique correlate of cardiometabolic risk. Diabetologia. 2012;55:2622–2630. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2639-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Figueroa AL, Abdelbaky A, Truong QA, Corsini E, MacNabb MH, Lavender ZR, Lawler MA, Grinspoon SK, Brady TJ, Nasir K, Hoffmann U, Tawakol A. Measurement of arterial activity on routine FDG PET/CT images improves prediction of risk of future CV events. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:1250–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rominger A, Saam T, Wolpers S, Cyran CC, Schmidt M, Foerster S, Nikolaou K, Reiser MF, Bartenstein P, Hacker M. 18F-FDG PET/CT identifies patients at risk for future vascular events in an otherwise asymptomatic cohort with neoplastic disease. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1611–1620. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.065151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paulmier B, Duet M, Khayat R, Pierquet-Ghazzar N, Laissy JP, Maunoury C, Hugonnet F, Sauvaget E, Trinquart L, Faraggi M. Arterial wall uptake of fluorodeoxyglucose on PET imaging in stable cancer disease patients indicates higher risk for cardiovascular events. J Nucl Cardiol. 2008;15:209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.nuclcard.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rudd JH, Warburton EA, Fryer TD, Jones HA, Clark JC, Antoun N, Johnstrom P, Davenport AP, Kirkpatrick PJ, Arch BN, Pickard JD, Weissberg PL. Imaging atherosclerotic plaque inflammation with [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Circulation. 2002;105:2708–2711. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000020548.60110.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D'Agostino RB, Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Wolf PA, Cobain M, Massaro JM, Kannel WB. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:743–753. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–3421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ridker PM, Buring JE, Cook NR, Rifai N. C-reactive protein, the metabolic syndrome, and risk of incident cardiovascular events: an 8-year follow-up of 14 719 initially healthy American women. Circulation. 2003;107:391–397. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000055014.62083.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maurovich-Horvat P, Massaro J, Fox CS, Moselewski F, O'Donnell CJ, Hoffmann U. Comparison of anthropometric, area- and volume-based assessment of abdominal subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue volumes using multi-detector computed tomography. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:500–506. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Subramanian S, Tawakol A, Burdo TH, Abbara S, Wei J, Vijayakumar J, Corsini E, Abdelbaky A, Zanni MV, Hoffmann U, Williams KC, Lo J, Grinspoon SK. Arterial inflammation in patients with HIV. Jama. 2012;308:379–386. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rudd JH, Myers KS, Bansilal S, Machac J, Rafique A, Farkouh M, Fuster V, Fayad ZA. (18)Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging of atherosclerotic plaque inflammation is highly reproducible: implications for atherosclerosis therapy trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:892–896. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenquist KJ, Pedley A, Massaro JM, Therkelsen KE, Murabito JM, Hoffmann U, Fox CS. Visceral and subcutaneous fat quality and cardiometabolic risk. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:762–771. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee MJ, Wu Y, Fried SK. Adipose tissue heterogeneity: implication of depot differences in adipose tissue for obesity complications. Mol Aspects Med. 2013;34:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wajchenberg BL. Subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue: their relation to the metabolic syndrome. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:697–738. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.6.0415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bays HE, Gonzalez-Campoy JM, Bray GA, Kitabchi AE, Bergman DA, Schorr AB, Rodbard HW, Henry RR. Pathogenic potential of adipose tissue and metabolic consequences of adipocyte hypertrophy and increased visceral adiposity. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2008;6:343–368. doi: 10.1586/14779072.6.3.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fontana L, Eagon JC, Trujillo ME, Scherer PE, Klein S. Visceral fat adipokine secretion is associated with systemic inflammation in obese humans. Diabetes. 2007;56:1010–1013. doi: 10.2337/db06-1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spagnoli LG, Bonanno E, Sangiorgi G, Mauriello A. Role of inflammation in atherosclerosis. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1800–1815. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.038661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bucerius J, Mani V, Wong S, Moncrieff C, Izquierdo-Garcia D, Machac J, Fuster V, Farkouh ME, Rudd JH, Fayad ZA. Arterial and fat tissue inflammation are highly correlated: a prospective 18F-FDG PET/CT study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41:934–945. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2653-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Christen T, Sheikine Y, Rocha VZ, Hurwitz S, Goldfine AB, Di Carli M, Libby P. Increased glucose uptake in visceral versus subcutaneous adipose tissue revealed by PET imaging. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:843–851. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Despres JP, Lemieux I. Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nature. 2006;444:881–887. doi: 10.1038/nature05488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blomberg BA, Akers SR, Saboury B, Mehta NN, Cheng G, Torigian DA, Lim E, Del Bello C, Werner TJ, Alavi A. Delayed time-point 18F-FDG PET CT imaging enhances assessment of atherosclerotic plaque inflammation. Nucl Med Commun. 2013;34:860–867. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e3283637512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blomberg BA, Thomassen A, Takx RA, Hildebrandt MG, Simonsen JA, Buch-Olsen KM, Diederichsen AC, Mickley H, Alavi A, Hoilund-Carlsen PF. Delayed (1)(8)F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT imaging improves quantitation of atherosclerotic plaque inflammation: results from the CAMONA study. J Nucl Cardiol. 2014;21:588–597. doi: 10.1007/s12350-014-9884-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emami H, Singh P, MacNabb M, Vucic E, Lavender Z, Rudd JH, Fayad ZA, Lehrer-Graiwer J, Korsgren M, Figueroa AL, Fredrickson J, Rubin B, Hoffmann U, Truong QA, Min JK, Baruch A, Nasir K, Nahrendorf M, Tawakol A. Splenic metabolic activity predicts risk of future cardiovascular events: demonstration of a cardiosplenic axis in humans. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.