Abstract

Clinicians commonly incorporate adolescents’ self-reported suicidal ideation into formulations regarding adolescents’ risk for suicide. Data are limited, however, regarding the extent to which adolescent boys’ and girls’ reports of suicidal ideation have clinically significant predictive validity in terms of subsequent suicidal behavior. This study examined psychiatrically hospitalized adolescent boys’ and girls’ self-reported suicidal ideation as a predictor of suicide attempts during the first year following hospitalization. A total of 354 adolescents (97 boys; 257 girls; ages 13–17 years) hospitalized for acute suicide risk were evaluated at the time of hospitalization as well as 3, 6, and 12 months later. Study measures included the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-Junior, Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children, Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised, Beck Hopelessness Scale, Youth Self-Report, and Personal Experiences Screen Questionnaire. The main study outcome was presence and number of suicide attempt(s) in the year after hospitalization, measured by the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children. Results indicated a significant interaction between suicidal ideation, assessed during first week of hospitalization, and gender for the prediction of subsequent suicide attempts. Suicidal ideation was a significant predictor of subsequent suicide attempts for girls, but not boys. Baseline history of multiple suicide attempts was a significant predictor of subsequent suicide attempts across genders. Results support the importance of empirically validating suicide risk assessment strategies separately for adolescent boys and girls. Among adolescent boys who have been hospitalized due to acute suicide risk, low levels of self-reported suicidal ideation may not be indicative of low risk for suicidal behavior following hospitalization.

Keywords: Suicidal ideation, Suicide risk assessment, Adolescence, Gender differences in suicide risk

Introduction

Recent nationally representative data indicate that 6.3% of high school students have attempted suicide in the preceding year (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2011). These suicide attempts are associated with psychiatric disorder and substantial psychosocial impairment; they are also well-established risk factors for suicide (Brent et al. 1988; Kotila 1992; Marttunen et al. 1992; Motto 1984). No one disputes the importance of preventing suicide and the morbidity associated with suicide attempts; unfortunately, it can be challenging to ascertain accurately an adolescent’s risk for suicidal behavior and suicide.

Suicidal thoughts are not uncommon during adolescence (Evans et al. 2005), particularly if one considers the broad range of such thoughts—from vague and fleeting thoughts to specific plans accompanied by suicidal intent. Suicide attempts occur less frequently, however, and suicide is relatively rare, which increases the likelihood of false positives when trying to identify those at elevated risk. The challenges of risk formulation and clinical decision-making are further compounded because suicidal thoughts and intent may vary across time and reflect changing mood states or interpersonal circumstances (King 1997).

Clinical guidelines converge in recommending that the formulation of a youth’s suicide risk be based on information from multiple sources. A clinical interview with the adolescent has been recommended as one essential component; however, information from a parent/guardian interview, standardized assessments, and ancillary sources (e.g., previous clinical provider) are also important (Huth-Bocks et al. 2007; Shaffer and Pfeffer 2001). A careful risk assessment is the foundation for clinical decision-making and care management, including decisions about whether to hospitalize or discharge recently suicidal youth from inpatient care, and decisions regarding the allocation of resources for appropriately intensive services and treatments.

Self-report instruments are often used to assess suicidal thoughts and related phenomena in adolescents. In a study of several commonly used instruments, Huth-Bocks et al. (2007) found that the Beck Hopelessness Scale (Steer et al. 1993), Suicide Probability Scale (Bagge and Osman 1998; Tatman et al. 1993), and Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-Junior High School version (SIQ-JR; Reynolds 1988) were moderately to highly sensitive as predictors of suicide attempt across a 6-month period. Nevertheless, increased sensitivity was obtained at the price of false positives or the substantial over-identification of adolescents as being at risk (i.e., decreased specificity). Such issues are particularly important given scarce mental health resources and the loss of freedom and continuity of outpatient care that may accompany psychiatric hospitalization.

In addition to the importance of identifying adolescents at risk while minimizing false positives when assessing suicide risk, there may be important gender considerations. Specifically, given the marked gender differences in suicidal phenomena among adolescents, information about the predictive validity of suicidal ideation in boys versus girls is important. Among American adolescents ages 15 to 19 years, suicide is 3.6 times more prevalent among males than females (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2011). However, the 2009 Youth Risk Behaviors Surveillance Survey indicated that, among high school students (9th–12th grade), males less often reported having seriously considered attempting suicide (10.5 %) and having attempted suicide (4.6 %) than did females (17.4% and 8.1 %, respectively; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2010). In addition to these marked differences, results from a large-scale, community-based prospective study of suicide attempts from adolescence to young adulthood (Lewinsohn et al. 2001) suggest that gender may moderate the value of self-reported suicidal ideation in risk assessments of adolescent boys. Specifically, Lewinsohn et al. (2001) found that females who attempted suicide in young adulthood had significantly higher rates of suicidal ideation and suicide attempt during adolescence than other females, but neither of these patterns held for males. Unfortunately, studies of the continuity of suicide risk across wide spans of development among community participants may not be directly relevant to the question of shorter-term risk assessment.

Finally, studies of clinical and school-based samples of adolescents indicate that youth who have made multiple suicide attempts are at higher risk for subsequent suicide attempt than those with histories of a single attempt or no attempt (Brent et al. 2009; Miranda et al. 2008); furthermore, this risk is not fully explained by more significant symptoms and more serious suicidal ideation. Of note, prior studies of hospitalized adolescents have not controlled for multiple attempt history or considered it as a moderator of the predictive validity of risk assessment (Huth-Bocks et al. 2007).

The purpose of this study was to examine the predictive validity of self-reported suicidal ideation for suicide attempt (as well as the number of attempts) among hospitalized and acutely suicidal boys and girls during a one-year follow-up. Self-reported suicidal ideation, measured by the SIQ-JR, is studied within the context of other risk factors for suicide attempts, including history of multiple suicide attempts and psychiatric symptoms. It is hypothesized that self-reported suicidal ideation will be a stronger predictor of suicide attempts in adolescent girls than in adolescent boys.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 354 adolescents who were psychiatrically hospitalized for acute suicide risk. These adolescents represent 79% of the total sample of 448 adolescents originally recruited for a randomized clinical trial of a post-hospitalization support intervention [name removed for blind review]. Study inclusion was based on adolescent or parent report of (a) recent (within past month) suicidal ideation that was unrelenting or accompanied by a specific plan, or (b) recent (within past month) suicide attempt, both from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV; Shaffer et al. 1998). Exclusion criteria included severe cognitive impairment, direct transfer to a medical unit or residential placement, distance of more than one hour’s drive, and unavailability of a legal guardian.

Adolescents were included in this study if they had 12-month outcome data in addition to baseline data for sex, history of suicide attempt, and suicidal ideation. This study was approved by the authors’ Institutional Review Board. Parents or guardians of participating adolescents provided written informed consent and adolescents provided informed assent.

Participants were assessed at baseline [within a week of hospitalization, M (SD)=1.3 (2.5) days], and again 3 months [mean (SD)=3.5 months (0.8)], 6 months [mean (SD)= 6.4 months (1.0)], and 12 months [mean (SD)=12.6 months (1.8)] later. Participation rates varied at assessments: 346 (98 %) at 3-months, 325 (92 %) at 6 months, and 356 (77 %) at 12 months. Reasons for subject loss were reported previously [reference name removed for blind review]. Participants with and without 12-month follow-up data did not differ significantly on gender, age, race, baseline SIQ-JR scores (described below), or history of multiple suicide attempts (yes, no). Furthermore, youth assigned to [study name], versus to usual care only, did not show a significantly different rate of suicide attempt during the 12-month follow-up.

This study sample was predominantly comprised of girls (73 %) and Caucasian (85 %) adolescents (Black: 8 %; Other/Biracial: 7 %). Adolescents’ mean age was 15.6 years (SD=1.3). The annual income of adolescents’ families ranged from less than $15,000 (6 %) to more than $100,000 (19 %), with a median annual family income between $40,000 and $59,000. More than half of participants’ mothers and fathers had completed at least some college.

Participating adolescents’ diagnoses, measured by the KSADS-PL (Kaufman et al. 1997), were distributed as follows: depressive disorder, 87.9 %; posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or acute stress disorder, 25.2 %; other anxiety disorder, 28.7 %; disruptive behavior disorder, 41.5 %; alcohol or substance use disorder, 20.8 %. Information about the diagnostician training and inter-rater reliability has been reported (removed for blinding).

Measures

Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempts

Baseline Suicidal Ideation

The SIQ-JR (Reynolds 1987) is a 15-item self-report questionnaire that assesses suicidal thoughts on a 7-point scale (I never had this thought to almost every day). Scores range from 0 to 90, with a published clinical cut-off score of 31. Initially developed as a screening tool for school settings, the SIQ-JR has been used in many clinical studies including several recent NIMH-funded trials with adolescents who are depressed and/or suicidal (King et al. 2009; Treatment for Adolescent Depression Study Team 2004). Its convergent validity has also been established, evidenced by significant relationships between SIQ-JR scores and lifetime history of suicidal behavior (King et al. 1993), as well as between SIQ-JR scores and both youth report of suicidal behaviors and clinician ratings of suicidal ideation (Prinstein et al. 2001). Finally, King et al. (1997) found that higher SIQ-JR scores among adolescent inpatients were associated with an increased probability of suicide attempt several months later, lending some support for the scale’s predictive validity. Internal consistency was strong within the sample (α=0.92).

Baseline and Follow-up Suicide Attempt(s)

Items from the Mood Disorders module of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV; Shaffer et al. 1998) were used to assess lifetime history of multiple suicide attempts at baseline (yes, no) and number of suicide attempts during follow-up. The time frame was adapted at each assessment to assess suicide attempts since the previous assessment. The kappa was 0.81 [se (kappa)=0.06] for these data.

Other Baseline Psychiatric Symptoms

Hopelessness

The Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS; Beck and Steer 1988) is a 20-item, true/false self-report questionnaire that assesses negative attitudes about the future (Goldston et al. 2001). Scores range from 0 to 20. It has been shown to predict eventual suicides in adult psychiatric patients and has demonstrated strong psychometric properties in adolescent samples (Goldston et al. 2001). In this study, 45.3% of boys and 47.5% of girls scored above a commonly used cutpoint of 9 (based on predictive validity shown in Beck et al. 1985). Internal consistency in this sample was 0.91.

Depressive Symptoms

The Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R; Emslie et al. 1997; Poznanski and Mokros 1996; Shain et al. 1990) is a semi-structured interview measuring depressive symptoms within the previous two weeks. It assesses 17 symptom domains. Items are rated on a 5- or a 7-point scale, with scores ranging from 17 to 113. The measure has strong psychometric properties with adolescent samples (Emslie et al. 1997; Shain et al. 1990). In this sample, 93% of boys and 96% of girls scores were greater than 40, which is commonly considered a clinical cutpoint and corresponds to a T score of 63 (possible depressive disorder warranting further evaluation). Inter-interviewer reliability for total scores assessed prior to data collection was high (mean alpha across raters=0.98). Internal consistency in this sample was 0.77.

Anxiety Symptoms

The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC; March 1997) is a 39-item self-report scale assessing a broad spectrum of anxiety symptoms. The MASC total score can range from 0 to 117. In this study, 21.2% of boys and 12.8% of girls scored above a t-score of 65 (based on sex and age), which is considered a clinical cutoff. Internal consistency for the total score in the [study name] sample was 0.92.

Internalizing and Externalizing Symptoms

The Youth Self-Report (YSR; Achenbach 1991) is a 119-item questionnaire assessing emotional and behavioral problems. Response choices range from 0 (not true) to 2 (very true or often true). The two scales (internalizing and externalizing) have strong psychometric properties, including internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and criterion and construct validity (Achenbach 1991; Thurber and Hollingsworth 1992). In this study, the mean scores for boys on YSR internalizing and externalizing scales corresponded to t-scores of 68 (± 1 SD: 56 to 77) and 61 (+ 1 SD: 52 to 72), respectively. The mean scores for girls on internalizing and externalizing scales corresponded to t-scores of 68 (+ 1 SD: 58 to 78) and 66 (+ 1 SD: 54 to 75), respectively. Internal consistency for this sample was 0.86 for the internalizing and 0.86 for the externalizing scale.

Substance use

The Personal Experiences Questionnaire (PESQ; Winters 1991, 1992) is a 41-item self-report questionnaire used to screen for abuse of alcohol or other substances in adolescents. The 18-item problem severity scale assesses the frequency with which adolescents engage in abuse behaviors using a four-point scale (never to often); scores range from 18 to 72. The PESQ has shown adequate reliability and validity for identifying problem substance use (Winters 1992). In this study, 32.3% of boys and 30.0% of girls scored above the recommended cutoff (for drug abuse assessment referral). In the overall study sample, the internal consistency for the problem severity scale was 0.94.

Statistical Analysis

Primary analyses examined the extent to which baseline suicidal ideation scores (SIQ-JR), demographic variables, and clinical covariates related to suicide attempts during the 12-months following hospitalization, and if the relation between suicidal ideation and the number of suicide attempts differed for boys and girls. A zero-inflated negative binomial (ZINB) model was selected because the outcome was zero-inflated (83% of adolescents did not make a suicide attempt during follow-up) and overdispersed (α=1.97, P = 0.014). ZINB is a mixture of two sub-models, the zero model for predicting the probability of no risk of suicide attempt and the negative binomial (NB) model for predicting the probability of any number of suicide attempts (0, 1, 2, 3,..). Using ZINB, the predicted proportion of adolescents who did not make a suicide attempt during follow-up was 0.84 (SD=0.08), whereas the observed proportion was 0.83. Similarly, the predicted average number of suicide attempts for this population is 0.270 (SD=0.17), which is close to the observed sample mean of 0.268 (SD=0.87).

The ZINB procedure involves entering covariates for each submodel (zero and negative binomial). We began with demographic characteristics (age, gender, race—black/white, parent education), three-level history of suicide attempts (none, single attempt and multiple attempt), intervention group, other possible psychiatric risk factors (Table 1), and two interactions (SIQ-JR score separately with gender and multiple attempt history). To achieve the most parsimonious model, nonsignificant variables (P ≥0.05) were removed one at a time, beginning with the most non-significant variable. Because there was no significant difference in outcome between adolescents with histories of single attempts or no attempts (ideation only), and because previous research points to the specific importance of multiple suicide attempt histories, the three-level history of suicide attempt variable was recoded into a two level variable (history of multiple suicide attempt, yes/no) for increased power. The logistic and negative binomials (with variance μi+αμi2) were chosen as the link function and distribution in submodels. Standardized coefficients were used for the continuous SIQ-Jr scores. Data were analyzed using the SAS 9.3 CountReg procedure.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics of the total sample and subsamples of boys and girls

| Clinical Characteristics | Total Sample (N = 354) Mean (SD) (Range) |

Boys (N=97) Mean (SD) (Range) |

Girls (N = 257) Mean (SD) (Range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SIQ-JR | 46.5 (21.0) (3.0–90.0) | 43.4 (20.7) (7.0–84.0) | 47.7 (21.1) (3.0–90.0) |

| BHS | 8.7 (5.8) (0–20) | 8.3 (5.9) (0–20) | 8.9 (5.7) (0–20) |

| CDRS-R* | 60.8 (13.0) (21–91) | 56.8 (12.2) (21.0–87.0) | 62.2 (13.1) (22.0–91.0) |

| PESQ | 28.3 (11.6) (18.0–66.0) | 28.6 (11.6) (18.0–63.0) | 28.2 (11.6) (18.0–66.0) |

| MASC | 46.4 (18.4) (0.0–101.0) | 43.9 (19.6) (0.0–87.0) | 46.9 (18.0) (4.0–101.0) |

| YSR- Internal | 28.5 (10.8) (4.0–58.0) | 25.4 (10.7) (4.0–58.0) | 29.7 (10.6) (4.0–55.0) |

| YSR- External | 21.4 (9.5) (0–50) | 20.9 (9.3) (0.0–49.0) | 21.6 (9.6) (1.0–50.0) |

SIQ-JR Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-Junior; BHS Beck Hopelessness Scale; CDRS-R Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised; PESQ Personal Experience Screening Questionnaire; MASC Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; YSR Youth Self-Report

girls>boys; t (353)=3.54, p<0.0005; No other significant difference is detected at p <0.05

Results

Baseline Clinical Characteristics

The baseline clinical characteristics of participating adolescents, provided in Table 1 (means and standard deviations), reflect significant impairment. In particular, the mean SIQ-JR score at baseline was 46.5 (SD=21.0); 74% of participants had scores at or above the clinical cutoff. The baseline CDRS-R raw score was nearly 61 (SD=13), which is well above the clinical cutoff score of 40 that is indicative of a possible depressive disorder; 94% of adolescents reached or exceeded this cutoff at baseline. As shown in Table 1, adolescent girls had significantly higher depressive symptom scores but other indices of psychopathology did not differ by gender.

At baseline, 37% of adolescents had a history of a single suicide attempt, and 39% had a history of two or more suicide attempts. Regarding the most lethal method, 77% of boys and 92% of girls with histories of one or more suicide attempts reported a most lethal method of cutting/slashing or ingestion (with positive intent); 23% of boys and 8% of girls reported a most lethal method of firearm, suffocation, jumping or different potentially immediate high lethality method. As reported in Table 2, 21% of adolescents with histories of multiple suicide attempts re-attempted during the follow-up, compared to 14% of other adolescents. Fisher exact tests indicated no gender differences between adolescents with and without histories of multiple suicide attempts with respect to reattempts during follow-up.

Table 2.

Observed number of suicide attempts among adolescents during 12-month follow-up

| Number of Post-hospitalization Suicide Attempts |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | >1 | |

| Baseline History of Multiple Suicide Attempts | |||

| No | 186 (86 %) | 27 (12 %) | 4 (2 %) |

| Yes | 108 (79 %) | 20 (15 %) | 9 (6 %) |

| Sex | |||

| Girls | 213 (83 %) | 34 (13 %) | 10 (4 %) |

| Boys | 81 (84 %) | 13 (13 %) | 3 (3 %) |

No significant difference in distribution of suicide attempts is detected at p <0.05 level by the Fisher exact test

Prediction Model Building: Zero, Negative Binomial, and Final ZINB Models

Zero Model: Predicting Probability of no Suicide Attempt During Follow-up

Estimates from the zero model are shown in Table 3. The gender by SIQ-JR estimate was significant, with a coefficient for the interaction of β3=−0.11, p = 0.03, indicating differences in the strength of prediction of suicide attempt from SIQ-JR scores for adolescent boys and girls. Follow-up analyses of this interaction indicate that the probability of making no attempt was inversely associated with SIQ-JR scores for girls (p = 0.03). That is, higher SIQ-JR scores were associated with increased risk for later suicide attempt for girls. There was no significant association for boys (p = 0.28). For each one point increase in SIQ-JR total score for girls, there was a 7% reduction in the probability of no attempt during the follow-up period.

Table 3.

Parameter estimates of ZINB model for predicting the number of suicide attempts during one-year follow-up (N = 354)

| Covariates | Coefficients Estimates |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient Estimate |

Standardized coefficient |

SE | t | p-value | |

| Zero Model (Predicting probability of no attempt) | |||||

| Intercept | −3.28 | −3.28 | 0.99 | −3.30 | 0.0009 |

| Baseline SIQ-JR | 0.04 | 0.86 | 0.04 | 1.09 | 0.28 |

| Sex (girls vs. boys) |

−0.01 | −0.01 | 0.96 | −0.01 | 0.99 |

| Baseline SIQ-JR*sex, |

−0.11* | −2.35 | 0.05 | −2.14 | 0.03 |

| Negative Binomial Model (Predicting # attempts) | |||||

| Intercept | −3.90 | −3.90 | 0.28 | −13.90 | <0.0001 |

| Multiple Attempt Hx (yes/no) |

0.93** | 0.93 | 0.29 | 3.20 | 0.002 |

N = 354;

p <0.05,

p <0.01

Gender coded boys (0), girls (1); multiple attempt history coded no (0), yes (1). When depression severity (CDRS-R scores) is kept in the zero model as a covariate, the SIQ-JR*sex interaction remains significant, p <0.05

Negative Binomial Model: Predicting Number of Suicide Attempts During Follow-up

As shown in Table 3, the only predictor that reached significance in the NB model was baseline history of multiple suicide attempts. Adolescents with a baseline history of multiple suicide attempts had a significantly higher risk of any suicide attempt during the one-year follow-up than did adolescents with histories of one or no suicide attempt. Gender did not significantly moderate this association.

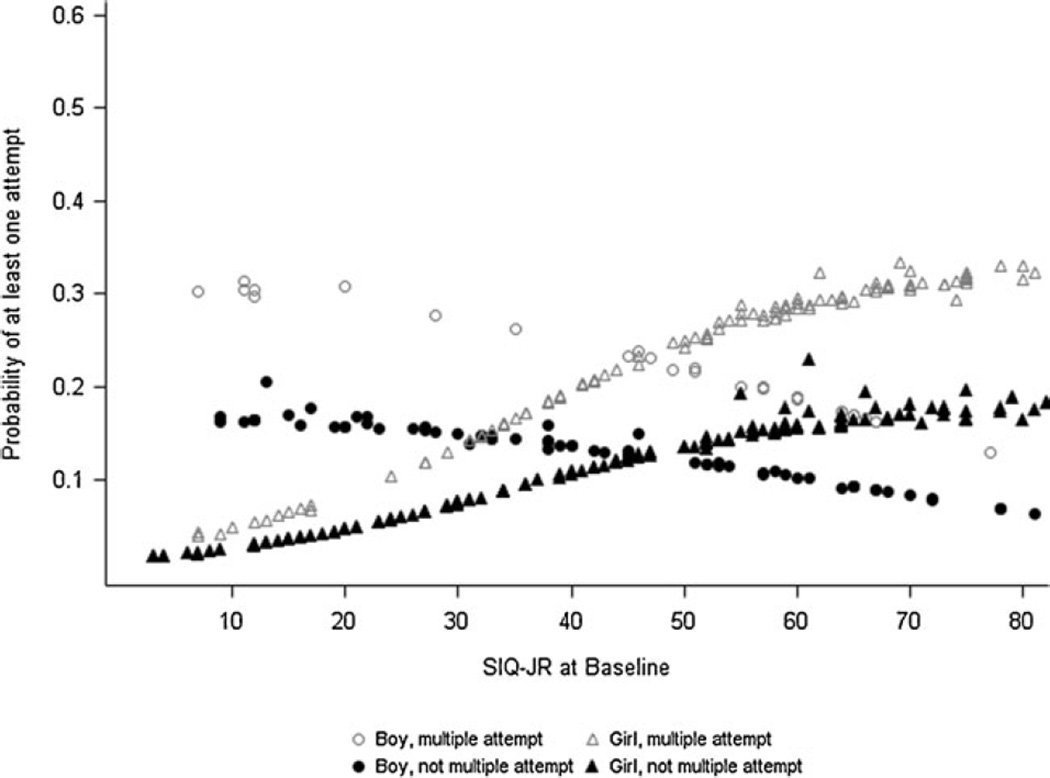

Final ZINB Prediction Model

The final ZINB model is the ‘weighted’ sum of results from the zero and NB models. Since the final probability is conditional on SIQ-JR score, sex, and lifetime suicide attempt history, the effects of these covariates (including interaction) are carried forward to the final result. The observed proportions and predicted probabilities for at least one suicide attempt (≥1) during the follow-up period are portrayed in Figs. 1 and 2. Results indicate that the probability of making more than one suicide attempt is higher for those adolescents with a history of multiple suicide attempts, holding other covariates fixed. In addition, gender modifies the effect of SIQ-JR on the risk of suicide attempt. For adolescent girls, the probability of suicide attempt increases when the SIQ-JR score increases whereas this pattern is not observed for boys (as shown in Table 3 and Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Observed proportion of adolescents making at least one suicide attempt (N = 354)

Fig. 2.

Probability of at least one suicide attempt as a function of SIQ-JR score, gender, multiple attempt history (N = 354)

Discussion

This study examined the predictive validity of self-reported suicidal ideation in a large clinical sample of acutely suicidal adolescent boys and girls. Self-reported suicidal ideation was assessed with the SIQ-JR (Reynolds 1988), which has been used frequently in clinical research with depressed and suicidal adolescents (Treatment for Adolescent Depression Study Team 2004). A primary finding was that total SIQ-JR scores had significant predictive validity for suicide attempts among adolescent girls, but not boys. In addition, adolescent girls and boys with a baseline history of multiple suicide attempts were more likely than other adolescents to make a subsequent attempt during the 1-year follow-up period.

The finding that self-reported suicidal ideation did not significantly predict suicide attempts for boys in this relatively large sample of 97 acutely suicidal adolescent boys is both clinically important and particularly disheartening. Males account for nearly 80% of suicides (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2011). Thus, any challenge to identifying and assessing suicide risk factors in adolescent boys poses a substantial barrier to the overall goal of suicide prevention. These gender-moderated findings are consistent with results from a large-scale, community-based prospective study of suicide attempts from adolescence to young adulthood (Lewinsohn et al. 2001), wherein higher rates of suicidal ideation during adolescence were associated with suicide attempts among girls but not boys. Although these researchers defined suicidal ideation as endorsement of one or more of three questions on the K-SADS diagnostic interview (thoughts of death or dying, wishing to be dead, thinking about hurting or killing self) rather than by the SIQ-JR, findings are consistent in demonstrating that suicidal ideation lacks predictive validity for males. This suggests that this pattern may reflect a consistent gender difference rather than idiosyncratic characteristic of the SIQ-JR or K-SADS.

There are at least three possible explanations for why SIQ-JR scores predicted suicidal behavior in adolescent girls but not boys. First, it is possible that differences between girls and boys in the nature or severity of psychopathology could help explain the gender difference in predictive validity. Of note, however, we did not find gender differences in multiple psychiatric covariates, including externalizing behaviors, alcohol and substance abuse, multiple suicide attempt history, and functional impairment. Further, our findings did not differ appreciably when depressive symptoms, which did differ by gender, were included as covariates in models. However, we did not adjust for psychiatric diagnosis, and we did not assess personality factors, such as borderline features, which may differ in prevalence by gender, be associated with increased suicide risk, and inform or complicate risk assessment (see review by Miller et al. 2008; Muehlenkamp et al. 2011).

It is also possible that the gender difference in predictive validity relates to gender differences in ruminative tendencies that may be relevant to suicidal ideation. Rumination is commonly conceptualized as a stable trait characterized by repetitive thinking about the causes and consequences of one’s negative emotional state (Smith and Alloy 2009). A study of early adolescent coping styles found that girls displayed higher levels of ruminative responding to stressful situations whereas boys relied more on distraction and problem-solving (Broderick 1998). Rumination is associated with longer and more severe depressed mood and increases in suicidal ideation (Smith and Alloy 2009). Thus, one hypothesis is that girls’ reports of suicidal ideation were more likely to reflect a vulnerability to prolonged negative mood and depressive rumination with or without rumination regarding suicidal thoughts.

Finally, it is possible that girls might have been more accurate and willing reporters of their suicidal ideation at the baseline assessment. For one, the fact that adolescent girls tend to ruminate about their distress more than boys may enable them to recall this distress, including their suicidal ideation, with more accuracy when completing assessment measures. Secondly, previous studies have shown that girls tend to share personal information and distress with others, such as friends and parents, more than boys (Hamza and Willoughby 2011; Landoll et al. 2011). Girls may have been more willing to share their thoughts of suicide in the context of this clinical study. There is an inherent problem with relying on self-report measures to assess suicide risk given that some individuals may not wish to disclose these internal experiences (King et al. 2012). Instruments that explicitly inquire about suicidal thoughts and behaviors, such as the SIQ-JR, are prone to this problem, but implicit measurement approaches may not be. For example, suicidal adolescents may be less guarded when reporting their attraction toward and repulsion by life and death (Osman et al. 1994), or on implicit cognition tasks that measure response latencies to associations between self and death or suicide (Nock et al. 2010). Future research should continue to examine how implicit measures contribute to the predictive validity of suicide risk assessment, and, given the present findings, whether such approaches are especially relevant when assessing boys.

Gender differences in the impulsivity of suicide attempts are unlikely to be a strong explanation for why the SIQ-JR was not found to be a good predictor of suicidal behavior for adolescent boys. Previous studies examining the role of gender in impulsive suicide attempts—generally conceptualized as involving a limited amount of planning prior to the attempt—have yielded mixed results. While some studies found that males are more likely than females to attempt suicide impulsively (Simon et al. 2001; Weyrauch et al. 2001), other studies (Conner et al. 2006) found the opposite effect. The majority of studies including adult and adolescent samples, however, suggest that gender does not differentiate impulsive from non-impulsive suicide attempters (Brown et al. 1991; Jeon et al. 2010; Lewinsohn et al. 1996; Simon and Crosby 2000; Wojnar et al. 2009; Wyder and De Leo 2007).

History of Multiple Suicide Attempts

A history of multiple suicide attempts was found to be a robust predictor of subsequent suicide attempt across the one-year follow-up. This is consistent with other studies of adolescents involving both clinical samples of adolescents (e.g., Brent et al. 2009) and a non-referred school-based sample of adolescents (Miranda et al. 2008). In the school-based sample, Miranda et al. found that adolescents with histories of multiple attempts were more likely to make a subsequent attempt across a four to six year follow-up than those with histories of a single attempt (odds ratio 4.6) or suicidal ideation only (odds radio 4.0). The same pattern was evident in the present study in which all adolescents were hospitalized for acute suicide risk. Perhaps this is not surprising given the converging evidence indicating that adolescents (e.g., Esposito et al. 2003; Miranda et al. 2008) and adults (e.g., Rudd et al. 1996) who have made multiple suicide attempts are characterized by more severe psychopathology and psychosocial impairment than individuals who have made one suicide attempt or who present with suicidal ideation only. For instance, Miranda et al. (2008) reported that adolescents who with a history of multiple suicide attempts were more likely to meet diagnostic criteria for a psychiatric disorder than adolescents who reported a single suicide attempt or ideation only. In a community study of 16,644 adolescents, multiple attempters were characterized by more health behavior risks, including heavy alcohol use, hard drug use, sexual assault and violence, than both single attempters and nonattempters (Rosenberg et al. 2005). Because of this well-documented pattern, multiple suicide attempt status is commonly used as a covariate or predictor in research related to adolescent suicide risk.

Repeated suicidal behavior cannot be dismissed as non-lethal, non-serious “attention seeking.” Indeed, Miranda et al. (2008) found that multiple attempting adolescents less often timed their attempts so that intervention was possible, more often reported wanting to die from their attempt, and more frequently reported regretting recovery compared to youth who attempted once or who reported ideation only. Multiple attempt status may reflect the presence of an additional vulnerability (e.g., impulsive aggression; Brent and Mann 2005) that allows only some suicidal individuals to act on severe ideation, and/or the opponent process and habituation to pain and fear that underlie (T. E. Joiner 2005) the notion of “acquired capacity.” An inherent weakness of multiple suicide attempt status as a key factor in risk assessment for adolescents is that all “multiple attempters” were at some point non-or single attempters.

Assessment of Suicidal Ideation

Very few scales have demonstrated clinically meaningful levels of predictive validity for future suicide attempts in clinical samples. As noted earlier, Huth-Bocks et al. (2007) examined the predictive validity of several commonly used assessment instruments, including the SIQ-JR, in a sample of acutely suicidal, hospitalized adolescents. They examined different clinical cutoff points and found that even moderately high levels of sensitivity were obtained at the price of relatively limited specificity. SIQ-JR items cover a broad range of content, with respondents indicating the frequency with which they had each thought during the past month. It is possible that stronger predictive validity would be evident for measures that assess longer time periods (including “worst point” ideation) and that assess not just thoughts, but also plans and active preparatory behaviors (e.g., collecting pills, writing a suicide note; Joiner et al. 1997; Joiner et al. 2003).

Two scales warrant consideration for their assessment of active preparatory behaviors. Beck’s Scale for Suicide Ideation (SSI; Brown et al. 2000) assesses plans or preparation for attempt, and both current (SSI-C) and worst-point in lifetime (SSI-W) versions have been tested (Beck et al. 1979; Beck and Steer 1991). In a large study of 3,701 adult outpatients, the SSI-W had a sensitivity rate of 80 %, a specificity rate of 78 %, and an odds ratio of nearly 14 in predicting eventual suicide deaths four years after initial assessment (Beck et al. 1999). Although the SSI-C, which is more similar to the SIQ-JR in terms of time frame, did not perform as well in identifying high risk for suicide in this study, SSI-C scores above a specific cutpoint were associated with a nearly 7-fold increase in the likelihood of a suicide in another 20-year prospective study of adult outpatients (G. K. Brown et al. 2000). A second scale that deserves further consideration for its assessment of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, including preparatory behaviors, is the Columbia—Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS; Posner et al. 2007). Though further research is needed to ascertain its sensitivity and specificity in predicting suicide attempts, Posner (2011) have documented favorable preliminary psychometric properties of the C-SSRS in adult and adolescent samples.

Study Limitations

The study sample was primarily Caucasian and recruited from the Midwestern region of the United States, which limits the generalizability of findings. In addition, although this study provides much information about the SIQ-JR as a predictor of future suicide attempts in acutely suicidal and psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents, this information may or may not generalize to outpatient samples of adolescents. It also may not generalize to the broad population of adolescent inpatients because discharge to residential placement was an exclusion criterion in the present study. It is also important to note that, although we consider a broad range of psychiatric symptoms and behavioral problems as predictors of suicide attempts in this study, we do not have data on personality disorders or non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), each of which may be important to the prediction of suicide attempts. For example, both prospective and retrospective studies have shown a relationship between NSSI and suicide attempts (e.g., Nock et al. 2006; Wilkinson et al. 2011). Finally, the large gender imbalance in this study is a limitation. Despite the inclusion of 96 boys in the study sample, there are substantially more girls in the sample, such that the likelihood of significant effects for girls is somewhat higher than for boys. This study also has notable strengths including its large clinically ascertained sample, its unique sample of acutely suicidal adolescents, and a prospective design.

Conclusions and Clinical Implications

Results suggest that adolescents’ self-reported suicidal thoughts, as measured by the SIQ-JR, are appropriately integrated into the multi-factorial clinical assessment of risk for girls only in the psychiatric inpatient setting. The integration of information about adolescent boys’ scores, particularly if these are low, could mistakenly lead the clinician to forego or shortcut a comprehensive risk assessment and formulation, and to minimize the boy’s possible risk. Although this finding warrants replication with other psychiatric inpatient samples and with samples of adolescents recruited from outpatient and other clinical settings, this study included a relatively large sample of boys and identified no trend toward prediction for these boys. It is possible that adolescent boys who engage in suicidal behavior, as a group, are less introspective than girls who engage in suicidal behavior, less willing to report emotional and cognitive distress, and/or characterized by a somewhat different set of characteristics and developmental trajectories toward suicidal behavior. It will likely be necessary to focus carefully on other risk factors—such as previous suicidal behavior, NSSI, impulsivity and aggressive tendencies, or alcohol abuse—to achieve meaningful predictive power for suicidal behavior among boys who are psychiatrically hospitalized.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the adolescents who participated in this study; and the support of the physicians, nurses, social workers, and administrative staff of the University of Michigan Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Inpatient Program. We also thank the study coordinators, independent evaluators, and research assistants. We especially thank Anne Kramer, Barbara Hanna, Ken Guire, Kristin Chadha, Alissa Huth-Bocks, Elisa Berger, Jeff Ammons, and Kiel Opperman, who contributed as University of Michigan staff members, and Lois Weisse, Cheryl McManus, and Tracy Laichalk, who contributed as Havenwyck Hospital staff members. This work was supported by a NIMH grant (R01 MH63881) and K24 career development award to Dr. Cheryl King.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Cheryl A. King, Email: kingca@umich.edu, Departments of Psychiatry and Psychology, University of Michigan Depression Center, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MN, USA; Department of Psychiatry, University of Michigan, 4250 Plymouth Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA.

Qingmei Jiang, Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MN, USA.

Ewa K. Czyz, Departments of Psychiatry and Psychology, University of Michigan Depression Center, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MN, USA

David C. R. Kerr, School of Psychological Science, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA Oregon Social Learning Center, Eugene, OR, USA.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the youth self-report and 1991 profile. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bagge CL, Osman A. The Suicide Probability Scale: Norms and factor structure. Psychological Reports. 1998;83(2):637–638. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1998.83.2.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Brown GK, Steer RA, Dahlsgaard KK, Grisham JR. Suicide ideation at its worst point: A predictor of eventual suicide in psychiatric outpatients. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1999;29(1):1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1979;47(2):343–352. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck hopelessness scale manual. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the beck scale for suicide ideation. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Kovacs M, Garrison B. Hopelessness and eventual suicide: a 10-year prospective study of patients hospitalized with suicidal ideation. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1985;142(5):559–563. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.5.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Greenhill LL, Compton S, Emslie G, Wells K, Walkup JT, Turner JB. The treatment of Adolescent Suicide Attempters Study (TASA): Predictors of suicidal events in an open treatment trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48(10):987–996. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b5dbe4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Mann JJ. Family genetic studies, suicide, and suicidal behavior. American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part C, Seminars in Medical Genetics. 2005;133C(1):13–24. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Perper JA, Goldstein CE, Kolko DJ, Allan MJ, Allman CJ, Zelenak JP. Risk factors for adolescent suicide. A comparison of adolescent suicide victims with suicidal inpatients. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1988;45(6):581–588. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800300079011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick PC. Early adolescent gender differences in the use of ruminative and distracting coping strategies. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 1998;18(2):173–191. [Google Scholar]

- Brown GK, Beck AT, Steer RA, Grisham JR. Risk factors for suicide in psychiatric outpatients: A 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(3):371–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LK, Overholser J, Spirito A, Fritz GK. The correlates of planning in adolescent suicide attempts. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1991;30(1):95–99. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199101000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance - United States, 2009. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2010;59(SS-5) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) 2011 Retrieved September 13, 2011 from http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html.

- Conner KR, Hesselbrock VM, Schuckit MA, Hirsch JK, Knox KL, Meldrum S, Soyka M. Precontemplated and Impulsive Suicide Attempts Among Individuals With Alcohol Dependence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67(1):95–101. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emslie GJ, Rush J, Weinberg WA, Kowatch RA, Hughes CW, Carmody T, Rintelmann J. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine in children and adolescents with depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54(11):1031–1037. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230069010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito C, Spirito A, Boergers J, & Donaldson D. Affective, behavioral, and cognitive functioning in adolescents with multiple suicide attempts. Suicide Life Threat Beh. 2003;33:389–399. doi: 10.1521/suli.33.4.389.25231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans E, Hawton K, Rodham K, Deeks J. The prevalence of suicidal phenomena in adolescents: a systematic review of population-based studies. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 2005;35(3):239–250. doi: 10.1521/suli.2005.35.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldston DB, Daniel SS, Reboussin BA, Reboussin DM, Frazier PH, Harris AE. Cognitive risk factors and suicide attempts among formerly hospitalized adolescents: A prospective naturalistic study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40(1):91–99. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200101000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamza CA, Willoughby T. Perceived parental monitoring, adolescent disclosure, and adolescent depressive symptoms: A longitudinal examination. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40(7):902–915. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9604-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huth-Bocks AC, Kerr DCR, Ivey AZ, Kramer AC, King CA. Assessment of psychiatrically hospitalized suicidal adolescents: Self-report instruments as predictors of suicidal thoughts and behavior. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46(3):387–395. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31802b9535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon HJ, Lee J-Y, Lee YM, Hong JP, Won S-H, Cho S-J, Cho MJ. Unplanned versus planned suicide attempters, precipitants, methods, and an association with mental disorders in a Korea-based community sample. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010;127(1–3):274–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE. Why people die by suicide. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Jr, Rudd MD, & Rajab MH. The modified scale for suicidal ideation: Factors of suicidality and their relation to clinical and diagnostic variables. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106(2):260–265. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.2.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Jr, Steer RA, Brown G, Beck AT, Pettit JW, Rudd MD. Worst-point suicidal plans: A dimension of suicidality predictive of past suicide attempts and eventual death by suicide. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2003;41(12):1469–1480. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(03)00070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent DA, Rao U. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King CA. Suicidal behavior in adolescence. In: Maris R, Silverman M, Canetto S, editors. Review of suicidology. Guilford Press; 1997. pp. 61–95. [Google Scholar]

- King CA, Hill EM, Naylor MW, Evans T, & Shain BN. Alcohol consumption in relation to other predictors of suicidality among adolescent inpatient girls. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32(1):82–88. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199301000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King CA, Hill RM, Wynne HA, Cunningham RM. Adolescent suicide risk screening: The effect of communication about type of follow-up on adolescents’ screening responses. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2012;41(4):508–515. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.680188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King CA, Hovey JD, Brand E, & Ghaziuddin N. Prediction of positive outcomes for adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(10):1434–1442. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199710000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King CA, O’Mara RM, Hayward CN, Cunningham RM. Adolescent suicide risk screening in the emergency department. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2009;16(11):1234–1241. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00500.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotila L. The outcome of attempted suicide in adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1992;13(5):415–417. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(92)90043-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landoll RR, Schwartz-Mette RA, Rose AJ, Prinstein MJ. Girls’ and boys’ disclosure about problems as a predictor of changes in depressive symptoms over time. Sex Roles. 2011;65(5–6):410–420. [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Adolescent suicidal ideation and attempts: Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1996;3(1):25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Baldwin CL. Gender differences in suicide attempts from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40(4):427–434. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March JS. Manual for the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC) Toronto Multi-Health Systems. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- Marttunen MJ, Aro HM, Lonnqvist JK. Adolescent suicide: Endpoint of long-term difficulties. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1992;31(4):649–654. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199207000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AL, Muehlenkamp JJ, Jacobson CM. Fact or fiction: Diagnosing borderline personality disorder in adolescents. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(6):969–981. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda R, Scott M, Hicks R, Wilcox HC, Munfakh JLH, Shaffer D. Suicide attempt characteristics, diagnoses, and future attempts: Comparing multiple attempters to single attempters and ideators. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47(1):32–40. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31815a56cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motto JA. Suicide in males adolescents. In: Sudak HS, Ford AB, Rushforth NB, editors. Suicide in the young. 227–244. Boston: John Wright PSG; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenkamp JJ, Ertelt TW, Miller AL, Claes L. Borderline personality symptoms differentiate non-suicidal and suicidal self-injury in ethnically diverse adolescent outpatients. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52(2):148–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Joiner TE, Jr, Gordon KH, Lloyd-Richardson E, Prinstein MJ. Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: Diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Research. 2006;144(1):65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Park JM, Finn CT, Deliberto TL, Dour HJ, Banaji MR. Measuring the suicidal mind: Implicit cognition predicts suicidal behavior. Psychological Science. 2010;21(4):511–517. doi: 10.1177/0956797610364762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman A, Barrios FX, Panak WF, Osman JR, Hoffman J, Hammer R. Validation of the Multi-Attitude Suicide Tendency Scale in adolescent samples. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1994;50(6):847–855. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199411)50:6<847::aid-jclp2270500606>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K. The Columbia-suicide severity rating scale: Initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168(12):1266–1277. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K, Oquendo MA, Gould M, Stanley B, Davies M. Columbia classification algorithm of suicide assessment (C-CASA): Classification of suicidal events in the FDA’s pediatric suicidal risk analysis of antidepressants. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164(7):1035–1043. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.164.7.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poznanski EO, Mokros HB. Children’s depression rating scale - revised (CDRS-R) Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Nock MK, Spirito A, Grapentine WL. Multimethod assessment of suicidality in adolescent psychiatric inpatients: Preliminary results. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40(9):1053–1061. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200109000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM. Suicidal ideation questionnaire—junior. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM. Suicidal ideation questionnaire: Professional manual. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg HJ, Jankowski MK, Sengupta A, Wolfe RS, Wolford GL, Rosenberg SD. Single and multiple suicide attempts and associated health risk factors in New Hampshire adolescents. Suicide Life Threat Beh. 2005;35:547–57. doi: 10.1521/suli.2005.35.5.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd MD, Joiner T, Rajab MH. Relationships among suicide ideators, attempters, and multiple attempters in a young-adult sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105(4):541–550. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.4.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas C, Board NDE, editors. DISC-IV. Diagnostic interview schedule for children (Youth informant and parent informant interviews): Epidemiologic version. New York: Joy and William Ruane Center to Identify and Treat Mood Disorders, Division of Child Psychiatry, Columbia University; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Pfeffer CR. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with suicidal behavior. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:24S–51s. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200107001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shain BN, Naylor M, Alessi N. Comparison of self-rated and clinician-rated measures of depression in adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;147(6):793–795. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.6.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon TR, Crosby AE. Suicide planning among high school students who report attempting suicide. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 2000;30(3):213–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon TR, Swann AC, Powell KE, Potter LB, Kresnow M-j, O’Carroll PW. Characteristics of impulsive suicide attempts and attempters. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 2001;32:49–59. doi: 10.1521/suli.32.1.5.49.24212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JM, Alloy LB. A roadmap to rumination: A review of the definition, assessment, and conceptualization of this multifaceted construct. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29(2):116–128. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steer RA, Kumar G, Beck AT. Hopelessness in adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Psychological Reports. 1993;72(2):559–564. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1993.72.2.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatman SM, Greene AL, Karr LC. Use of the suicide probability scale (SPS) with adolescents. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 1993;23(3):188–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurber S, Hollingsworth DK. Validity of the achenbach and edelbrock youth self-report with hospitalized adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1992;21(3):249–254. [Google Scholar]

- Treatment for Adolescent Depression Study Team T. Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: Treatment for adolescents with depression study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292(7):807–820. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.7.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyrauch KF, Roy-Byrne P, Katon W, Wilson L. Stressful life events and impulsiveness in failed suicide. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2001;31(3):311–319. doi: 10.1521/suli.31.3.311.24240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson P, Kelvin R, Roberts C, Dubicka B, & Goodyer I. Clinical and psychosocial predictors of suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the adolescent depression antidepressants and psychotherapy trial (ADAPT) The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168(5):495–501. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10050718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC. Personal experience screen questionnaire (PESQ) manual. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC. Development of an adolescent alcohol and other drug abuse screening scale: Personal Experience Screening Questionnaire. Addictive Behaviors. 1992;17(5):479–490. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90008-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojnar M, Ilgen MA, Czyz E, Strobbe S, Klimkiewicz A, Jakubczyk A, Brower KJ. Impulsive and non-impulsive suicide attempts in patients treated for alcohol dependence. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;115(1–2):131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyder M, De Leo D. Behind impulsive suicide attempts: Indications from a community study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;104(1–3):167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]