Abstract

In this paper we report on a new qualitative instrument designed to study the intersection of identities related to sexuality and race/ethnicity, and how people who hold those identities interact with social contexts. Researchers often resort to using separate measures to assess race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and other target identities. But this approach can miss elements of a self-system that stem from the intersection of identities, the interactions between identities and social contexts, related shifts in identity over time, and related changes in the prominence and valence of identities. Using a small sub-sample, we demonstrate how our instrument can help researchers overcome these limitations. Our instrument was also designed for economy in administration and analysis, so that it could be used as a qualitative complement in large survey research

Keywords: identity, stress, mental health, minorities, race, ethnicity, sexuality, gay, lesbian, intersectionality, qualitative method

Identity researchers have recently turned to describe the intersection of social identities, and the crosscutting of identity statuses, roles, and labels (Stewart & McDermott, 2004; Ashmore, Deaux, & McLaughlin-Volpe, 2004). Stewart and McDermott (2004) have suggested three basic premises underlying the intersectionality of identities: “(a) no social group is homogenous, (b) people must be located in terms of social structures that capture the power relations implied by those structures, and (c) there are unique, nonadditive effects of identifying with more than one social group” (p. 531). Intersectionality becomes especially important when researchers study the crossroads of racial/ethnic and sexual minority identities and how these identities relate to social contexts. At stake is not only the merging of identities but also the emergence of unique, self-constructs resulting from such intersections.

Although researchers have recognized that identities related to race/ethnicity, gender, and sexuality need to be considered in conjunction, they have rarely looked at the intersection of identities as a distinct new category. Rather, they have tended to add multiple identities. As Glenn noted in the case of gender, “If we begin with gender separated out, we have to ‘add’ race in order to account of the situation of women of color. This leads to an additive model in which women of color are described as suffering from ‘double’ jeopardy” (Glenn, 2000, p. 3-4). By contrast, with respect to sexual orientation and race, Crenshaw (1996) has described a nonadditive model. She noted that an African American lesbian identity is distinctively different from both African American and lesbian identities, and that the intersection creates a new entity that must be viewed as unique. Thus African American lesbians face social and psychological concerns that are different than those faced both by heterosexual African American women and White lesbians and therefore can only be captured at the intersection of race and sexual identity.

Crenshaw’s legal theory suggests that accounting for nonadditive effects of intersected identities is important not only theoretically, but also because of the possible social and psychological conflicts that intersectionality can carry. Consider, for example, an African American lesbian respondent quoted in Rust (2003, p. 232): “When I came out, it was made clear to me that my being queer was in some sense a betrayal of my ‘blackness.’ … I spent a lot of years thinking that I could not be me and be ‘really’ black too.” A Mexican American woman in the same study said: “[I] felt like … a traitor to my own race when I acknowledge my love of women. I have felt like I’ve bought into the white ‘disease’ of lesbianism” (p. 232). Similarly, Crawford, Allison, Zamboni, and Soto (2002) see in gay Black men’s identities a conflict between two cultural poles, racial and sexual, which have unique and sometimes stressful implications for the person and the group.

The interactions among various components that constitute one’s intersectional identities are complex. For example, for a man who identifies as gay, Latino, and Colombian, self-descriptors can become more or less significant, functional, or active depending on the contexts such as time, place, and institutional settings. The person with intersectional minority identities may thus experience psychological and social demands that are unique to the specific constellation of minority identities and related power structures. Intersectionality, therefore, sheds a new light on racism, sexism, and homophobia because the person with intersectional identities is faced not with each of such “isms” in isolation but with a fluid and contextual sexualization of race/ethnicity and racialization of sexuality. These theoretical perspectives call for new ways of thinking about race/ethnicity, sexuality, and gender. But although intersectionality holds promise for minority identity and health research, intersectional identities have not been sufficiently studied. This is, in part, because intersectionality is an emerging conceptual framework, and, in part, because instruments for the assessment of intersectional identities are yet to be developed.

The Measurement of Identity

Quantitative approaches

By and large, existing identity measures are limited in that they assess identity constructs in isolation rather than at the intersection. For example, identity measures typically assess race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and gender as separate constructs. Racial/ethnic identities are often measured as relatively isolated from other identities, and measures typically focus on strength of identity through ideological positions and feelings of affirmation and bonding to an individual’s ethnic or racial groups (Sellers, Ashmore, Deaux, & McLaughlin-Volpe, 2001; Contrada, et al., 2001; Phinney, 1992; Sellers, Smith, Shelton, Rowley, & Chavous, 1998). Attitudes towards, and interactions with other ethnic groups are also typically measured. Phinney, for instance, included in her Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure items such as, “I have a strong sense of belonging to my own ethnic group” and, “I enjoy being around people from ethnic groups other than my own” (1992, p. 172-3).

Measures of gay and lesbian identities often target certainty or uncertainty of self-identification as well as identity development via coming out stages (Mohr & Fassinger, 2000; Savin-Williams & Diamond, 2000). Savin-Williams and Diamond (2000) used semi-structured interviews to assess gender-based differences in the sequencing of sexual identity milestones such as first same-sex attraction, first same-sex sexual activity, labeling of sexual identity, and first disclosure of non-heterosexual identity to another person. Whereas racial and sexual minority identity measurements often focus on strength of identity, gender models and related quantitative assessments often focus on formation of gender roles, political identities (Gurin & Townsend, 1986), and related ideological positioning (Henderson-King & Stewart, 1994; Henley, Meng, O’Brien, McCarthy, & Sockloskie, 1998; Zucker, 2003). For example, Henderson-King and Stewart (1994) examined the relationship between group identity and feminist consciousness by asking women about their identification with group labels such as “women” and “feminist.”

These examples show that quantitative measures typically position race/ethnicity, gender and sexual orientation identities as parallel rather than intersectional; they therefore miss unique social and psychological elements that exist at the intersection of these identities. Though these kinds of measures can usefully uncover an overall sense of belonging to one’s ethnic/racial group, they do not allow respondents to report on how such ethnic attachments interact with attachments related to gay or lesbian identities. These approaches can thus limit our understanding of the complexity of identity and attachment because they obscure how respondents conceive of and navigate multiple collective identities.

An exception is Hierarchical Classes Analysis (DeBoeck & Rosenberg, 1988; Rosenberg & Gara, 1985), which measures interrelationships, differential hierarchization, commonalities and distinctions in the elaboration of various identity constructs (Stirratt, Meyer, Ouellette, & Gara, unpublished). But while providing strength on interrelationships of identities, the quantitative approach of this and other measures is limited in assessing context and identity processes over time that are specific to each individual. These are better captured by qualitative approaches.

Qualitative approaches

Open-ended qualitative approaches have strength when assessing processes and temporality and allowing respondents to talk about idiosyncratic identity constellations (see Denzin & Lincoln, 2002). Group-oriented techniques, such as focus groups, and individualized techniques, such as in-depth interviews, life histories, personal narrative, and autoethnography can capture, overall, the intersection of identities and their relationship to context (Denzin & Lincoln, 2002). However they are also limited in various ways. For example, focus groups can be used to assess how social groups collectively understand identity, particularly among marginalized communities, or on topics that are often silenced such as sex and sexuality (Frith, 2000; Madriz, 2002). But focus groups are limited in the exploration of intersectionality. Because of the strong group influence on how group members construct the task, and what identities members express and discuss, focus groups often discourage self-referential thinking. In contrast, questions of intersectionality require that individuals process their own thoughts about identity and about how their identities are individually organized and lived.

Self-referentiality is better elicited by one-on-one approaches such as in-depth interviewing and life histories (Dowsett, 1996). However, such approaches typically aim at comprehensively assessing many areas of life and not at targeting specific spheres, such as interesectionality of identities and its relationship to social institutions. Similarly, other approaches such as participant observation, personal narrative, and classic or critical ethnography can help researchers understand both individual and collective identity processes (e.g., Angrosino, 1992; Ellis and Bochner, 2002; Krieger, 1983; Wolf, 1992). Such approaches are comprehensive but they are limited by their lack of precision and are cumbersome for analysis. Also, because these approaches often require large amounts of time and other resources, they are not a reasonable tool for survey research.

A New Qualitative Assessment of Intersectionality

This paper presents a new qualitative approach for the study of the intersection of identities. We designed an instrument to address the methodological limitations outlined above. In addition to providing data on the intersectionality of minority identities, we aimed to assess the social dimensions of stress related to minority identities. Finally, the instrument was designed to be used effectively and economically in survey research. We report on the design and testing of this qualitative component.

Methods

Qualitative data on identity was collected as part of a larger longitudinal study on stress, identity, and health called Project [Name]. The project aims to study prejudice and discrimination as stressors related to sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, and gender; assess their impact on mental health; and describe the role of identity in moderating the relationship of stress and mental illness ([Author], 2003). 528 individuals were interviewed for the larger study with a sub-sample (n = 61) given an additional qualitative component. We report on the design and testing of this qualitative component. The qualitative interview lasted 40 minutes on average, and was conducted as the final component in a comprehensive face-to-face interview. The mean length of time to complete the full assessment battery was 3 hours and 49 minutes (SD = 1.0 hour).

Sample

Respondents were recruited through a purposive sampling strategy (Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002) from diverse venues in New York City, such as coffee houses, public parks, bars, bookstores, special events, social or interest groups, and community organizations. Respondents were eligible if they met the following criteria: New York City resident for 2 years or more; 18 to 59 years old; sufficient spoken English to engage in casual conversation; and self identification along discrete categories of gender (male or female), sexual orientation (gay, lesbian, bisexual, or other terms indicating same-sex orientation, such as “queer”), and race/ethnicity (Black/African American, Latino/Hispanic, White, or other terms referring to these categories). For the current report, 16 narratives (one from a pilot test) were selected (Table 1). The purpose of selecting this small sub-sample was to illustrate how our instrument performed, so as to suggest a strategy for researchers to better understand intersectionality, and how people who hold multiple minority identities interact with social structures.

Table 1.

Description of participants Demographics (N=16)

|

Men

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | Age |

Annual Household

Income |

Education | Selected Self-Descriptors |

| African American |

45 | $50,000-74,999 | HS diploma | Black; gay; just being me; male. |

| African American |

34 | $45,000-49,999 | HS diploma | African American; gay; all male; religious principles; uncle/father figure. |

| African American |

28 | $1-999 | HS diploma | Black (African American); (bisexual); male on the outside female on the inside. |

| Latino | 19 | $6,000-6,999 | HS diploma | Latino; gay; male; 19. |

| Latino (Pilot) | 34 | Not recorded | Doctoral student |

Latino; gay; 30’s; male; New Yorker. |

| Latino | 22 | $10,000-10,999 | Less than HS diploma |

Hispanic; bi-sexual; strong male; erotic; un- inhibited; 22; 67. |

| White | 58 | $35,000-39,999 | Some postgraduate |

Caucasian/Jewish; gay; self-employed; theater-lover; cyclist. |

|

| ||||

|

Women

| ||||

| African American |

28 | $2,000-2,999 | HS diploma | Native American; Jamaican; futch (female butch); generation X; honest; spiritual. |

| African American |

38 | $45,000-49,999 | Some college | Gay; love women; out spoken; leader; love take care people. [No Race/Ethnicity written.] |

| African American |

59 | $20,000-24,999 | Bachelor’s degree |

Black; gay woman; Black aggressive gay woman angry at times; honest; mediator. |

| Latina | 21 | $20,000-24,999 | Some college | Mexican-American; Chicana; brown; queer; non- label; fluid; dyke; lesbo; female; genderqueer; musical activist. |

| Latina | 50 | $35,000-39,999 | Some college | Hispanic; bisexual; mother; poet; lover; responsible person. |

| White | 26 | $30,000-34,999 | Bachelor’s degree |

White; queer/lesbian; female; single; middle- class; sexual. |

| White | 28 | $20,000-24, 999 | Master’s degree |

French; lesbian; butch/boi; pothead; bilingual. |

| White | 32 | $75,000-99,999 | Some postgraduate |

White girl; white bitch; lesbian; dyke; feminist; chick; teacher; woman; rock/stable. |

| White | 42 | $100,000-149,000 | Doctoral level degree |

Southerner; white; lesbian; androgynous woman; worrier; adventure lover. |

Instrument Development

The instrument was developed by Project [Name] investigators because we found that no existing measures were able to capture our constructs of identity and stress at the intersection of sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, and gender. Our approach aimed at eliciting self-referential narratives about identity and stress without confining the respondents to singular identities. We aimed for an instrument that would allow respondents to describe their sense of their identities within socio-cultural contexts and over time. At the same time, we strove for precision in getting answers to the research questions and efficiency in the data analysis. We opted for an approach that incorporated semi-structured interviews directed by the interviewer. The instrument was piloted in two phases between June 3, 2003 and December 23, 2003. In the first phase there were 8 pilot participants and we tested initial open-ended questions, probes, and visual cues. These items were evaluated and modified for the second pilot. After the second pilot, we again made corrections to our questions, probes, and visual cues to make them more easily understandable. This became the working version with which we collected the 16 study interviews discussed in this report. After we collected these data, we made very slight edits to the instrument, which are reflected in this paper.

We aimed to design an instrument that would: (a) elicit personal definitions of identity and narratives about interrelations among identities, statuses, and roles; (b) provide narratives about the interaction between identity and institutional settings such as work, family, and community life; and (c) describe social stressors associated with these identities and institutions.

Instrument Administration and Content

Following the pilot iterations, the final instrument we used has four parts that were administered as described below. Notwithstanding the recommended order of administration, interviewers were allowed to alter either the order of questions or their specific content depending on the flow of the interview. Interviewers were instructed to probe narratives following standard guidelines to qualitative interviewing (Denzin & Lincoln, 2000), but we devised specific instructions and probes concerning possible biases relevant to the questions about identity and social stress. Three taped interviews were randomly selected every month for the first four months for monitoring. One investigator ([Author]) reviewed them and wrote memoranda that were reviewed by a second investigator ([Author]).

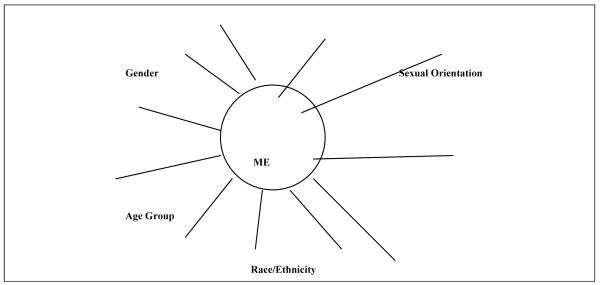

Part 1. Labeling of identities and roles

At the beginning of the assessment the respondent is presented with a visual cue (Figure 1) and asked to write any number of identity and role labels that he or she sees as self-descriptive. The visual cue shows 12 arms protruding out of a circle with open spaces around them. It includes four pre-typed categories that are of interest to the study (gender, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, and age), to which respondents may add their own labels, though they are not required to enter any labels for these categories. The purpose of the figure is to depict to the respondent the open-ended nature of the exercise. The blank arms as well as any area on the page can be used to fill in the identity labels that the respondent associates with him or herself. The respondent can enter as many identities as he or she wishes, and can write them in any spatial design he or she chooses. The instructions for eliciting these identity labels read as follows:

Please write down any identities and roles that you think best describe who you are on this sheet of paper. You can include identities or roles that you find challenging or problematic. You can use this diagram to arrange the identities and roles in any way you want. If you want you can look at the identities and roles you’ve listed earlier, but you don’t have to. [This refers to a “Who Am I” questionnaire that the respondent had filled out as part of the quantitative portion of the interview (Kuhn & McPartland, 1954).] This time you can list as many identities and roles as before, or fewer, or more. You can use the pre-written categories on this diagram or not. It is important that you think of this as a completely separate task, as if I did not see your answers to the identity questions earlier or anything else we discussed during the interview. Please describe who you are in terms of roles and identities as best as you can.

Figure 1.

Identities and roles visual clue

Interviewers are instructed to use probes to determine the respondent’s engagement with identity constructs. If a respondent has not provided any label under a category of main interest to the study (sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, gender, and age group), the interviewer probes by asking, for example, “You did not write anything under race, can you talk about that?” The goal here is not to force participants to nominate these identities, but to understand why such categories were left unstated. Often, these probes bring forth interesting narrations about why such categories as race/ethnicity were unimportant for the respondent. Also, the interviewer can probe identity labels that were not sufficiently elaborated by the respondent. Some labels, such as gay, lesbian, or Latino, may seem to the respondent as obvious and beyond the need for clarification. A possible probe in such instances is: “If I were from another culture, how would you explain to me what you mean by ‘Latino’ so that I understand what it means to you today?” The interviewers are instructed to notice unusual narratives and probe them as an opportunity to get clarifications and personal meanings. For example, one respondent wrote “22-67” under the age category. When probed, the respondent explained that “22” stands for his biological age and “67” for his “experience in life.” In general, interviewers follow and trace the respondents’ own logic, so that narratives convey how respondents subjectively make sense of, and ascribe meanings and values to, their identities.

Part 2: Relationships among identities

After identity labels are elicited, respondents are asked to talk about them—for example, to describe how important they are and whether different identities fit or compete with one another. For example, a respondent might discuss how his “Latino” identity relates to his “gay” identity, and in which settings these identities might be in harmony or in conflict. The guidelines for this exercise read:

This diagram shows all of your identities in a circle, almost as though they were evenly balanced. What I’m interested in is whether these identities tie in with one another or not. So, first, can you tell me in what ways these identities fit or don’t fit together? In what ways do they compete with one another or are in harmony?

After the diagram is filled in with identities and labels, the interviewers are instructed to probe, “Is there anything on this sheet that does not capture how you think of yourself?” in order to segue into the narrative portion of the interview.

Part 3: Relationships between identities and social institutions

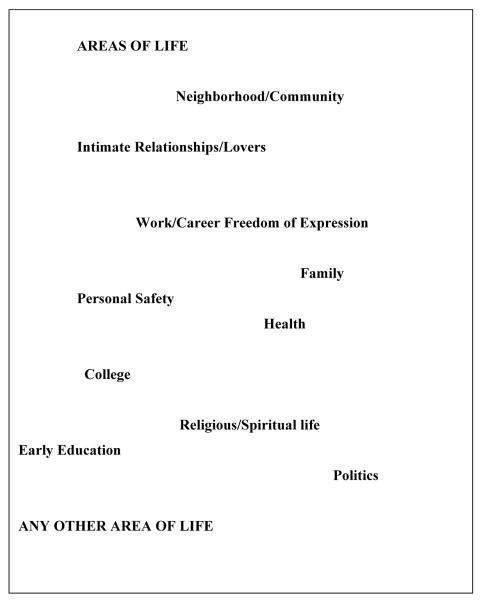

After discussing identities, respondents are asked to talk about stressors or strengths related to these identities. For example, respondents can discuss a gay identity with respect to work, a Black identity with respect to church, etc. This discussion focuses on whether conflict or harmony arose from such interactions in the respondent’s daily life, and if so to what degree. To help the respondent a visual cue shows labels of various areas of life scattered on a sheet of paper in no apparent order (Figure 2). Areas of life were identified during the pilot period, including neighborhood/community, intimate relationships/lovers, work/career, freedom of expression, family, personal safety, health, college, religious/spiritual life, early education, and politics. The guidelines for this section are:

We talked before about different parts of your identity and about different roles. We want to know how these parts of your identity and these roles might have affected certain areas of your life, and about good and bad experiences related to these areas of life. You can think of the areas of life described here [Figure 2] or any others.

Figure 2.

Relationships between identities and institutions visual clue

Respondents discuss experiences related to any of these areas and/or can introduce areas of life that were not listed in Figure 2. Interviewers watch for and discourage any narrative about social stressors that takes an impersonal tone, for example generic political statements, if such responses abstract elements of the respondent’s personal story and eliminate personal significance. Though respondents may experience their identities politically, interviewers probe to understand how respondents themselves, in their own everyday life, experience the world politically. For example, impersonal statements such as “in this society people are homophobic” are rendered personal by probing for concrete examples, anecdotes, or stories that depict specific situations in specific settings. An interviewer may ask: “Can you give me some examples of how this has affected your own life?” By probing for concrete examples, anecdotes, or stories, the interviewer helps the respondent provide a more personal narrative.

Part 4: Narratives about “non-events”

We defined “non-events” as conditions that are stressful because of their absence not their occurrence (Williams, Jackson, & Neighbors, 2003). They relate to experiences and resources that were withheld from or not achieved by the person (e.g., the denial of a state-recognized marriage to a gay person). In piloting the instrument we found that such experiences are often captured throughout the narrative but they can also elude notice and/or awareness. To capture non-events we added a final question to the exercise that elicits conditions related to homophobia, racism, and sexism. This question read: “How do you think your life would be like without homophobia, racism, and sexism?” Although this question seems indirect and somewhat vague, we found in the pilot interviews that it has allowed respondents to reflect on experiences and resources that are unavailable to them.

Data Analysis

Our reading of the interviews was guided by an awareness of the need to create a new approach to assess identity and the relationship between individual identity systems and social systems. The goal of the following analysis is not to draw conclusions about constructs, but to test this qualitative instrument and demonstrate its effectiveness and economy in obtaining rich detail on intersectional identities. One researcher ([Author]) provided an abridged transcription from the 16 interviews, along with a commentary. The quotes and commentaries were then discussed by the investigators and differences were resolved through iterative group discussions. Our interpretations were not constrained by the interpretive prescriptions of existing identity models as these have little to relay, overall, about how people who hold interacting minority identities relate to social contexts.

Three questions guided our interpretation: How did respondents understand, organize, and script their identities? How did they understand the interactions among self-descriptors (identities, statuses, and roles) and the interactions between self-descriptors and social contexts? How did respondents, through these interactions, create norms and behaviors that allowed them to cope with or contest the scripts implied by mainstream social environments (such as work, family, and church)? The instrument also elicited self-descriptors and narratives that were not associated with sexuality or ethnicity, but this paper focuses primarily on meanings related to sexuality and ethnicity.

Results

Respondents provided a rich variety of self-descriptors in a wide range of identity and role areas. Three central themes from the theoretical perspective of our parent study emerged in this data: (a) identity prominence, that is, how important an identity is in the person’s overall identity hierarchy, (b) identity valence, that is, whether identities are subjectively seen as positive or negative, and (c) stress and resilience, that is, the psychosocial burden on the person related to minority status and identity and the degree to which the minority person adapts to, copes with, or contests majority cultural and psychological demands. Finally, we described interactions among identities and between identities and social contexts. Our instrument illuminated these themes in unique ways, improving upon the methodological limitations of quantitative measures (discussed in the previous section).

Identity Prominence

We explored the theme of prominence of identities within the respondent’s identity structure. We examined which identities are important—in that they are invested with stronger commitments—and which are less important. For example, a 28-year-old White lesbian wrote “French” under race/ethnicity on the visual cue. During the narrative she discussed this in comparison with a White identity: “I know that I am [White] …but it, because… I’m never reminded of it, I kind of forget that that’s what I am. So I tend to forget to put it as a strong part of my identity.” In contrast to this description of race/ethnicity as peripheral in terms of prominence, the same respondent described a prominent “butch lesbian” identity, which, the narrative further suggests, has gained prominence in recent years as a result of interactions with the “butch-lesbian community.”

As a masculine woman, I was never made to feel attractive by people around me because it’s not conventional, and rather than sort of flaunt it, you know, of course my reaction was to hide it, and to not know what to do with it. So to meet someone who says not only do I find you sexy but you belong to this community of people and they find you sexy too, and you know, you have this place … really made me capable of exploring that side of me.

A special strength of our instrument is that it is able to show how identity prominence can adapt to social contexts and change accordingly. One 34-year-old Latino gay man described his gay identity as prominent in the context of gay friends and intimate relationships, but described the same identity as suppressed in the context of work and church. The change in prominence was so distinct that it was accompanied by changes in physical presentation:

I think in the public face I don’t think I indicate that I am gay. And pretty much people will assume I am straight and I don’t make any effort to correct that. And that’s sort of how I want it … I act in a different sort of way with my friends than I would be with colleagues and coworkers or anyone outside my gay friends. So maybe the jokes that we would tell or the reference to a show or something that I did that would label me as gay. So yeah, I would act totally different. Oh yeah, church as well, the concept is that I am straight … when I talk on the phone with a church member my voice gets deeper and louder so there almost two personalities.

The instrument also detected shifts in prominence of identities that resulted from maturation. For example, a White, 42-year-old lesbian, for example, demonstrated that racial/ethnic identity became less prominent and a sexual identity became more prominent along with a shift from negative to positive sexual identity valence. In response to the visual cue that asks for identity labels, she composed a label that incorporates these historical shifts in her self-identity, describing herself as a “southerner, former Christian/Baptist, White, small town girl turned urbanite [in] exile.” The narrative elaborated on this label, showing that during the respondent’s childhood and adolescence her identity revolved around a racial/ethnic identity (“white southerner”). Her move to New York City, precipitated in part by her parents’ discovery and termination of her relationship with her girlfriend, triggered important life changes, “All the main pillars of my identity, until I was twenty-one … sort of got just knocked out from under me, rapidly, kind of in an acute way, and I came here [to New York City] and had to put it all back together again.” After 20 “traumatic” years of “exile” in New York City—where many changes in her self-perception and affiliation occurred—her identity has come to be avowed mostly in sexual orientation terms (“lesbian”). “Trying to deal with coming out and all that … I feel like a lot of it [being a lesbian] really became much more prominent.”

Identity Valence

Valence relates to the extent to which identities are perceived as positive, negative, or neutral. Similar to what we observed with prominence, the respondents’ narratives showed variations in valence of sexual and ethnic identities and important contextual and temporal shifts in identity valence. For example, a 22-year-old Puerto Rican bisexual man described the recursive relationship of his self-evaluation and his perceptions of social attitudes toward homosexuality around him:

When I was younger, I was always afraid, ashamed of being, you know, of being attracted to members of my sex … And, you know, I was just very, I always felt wrong because that’s what society instilled in me, you know, and my father, and all that stuff.

He described how this shame pervaded “just everything, everybody, everything,” and was “my deepest, darkest secret, my biggest shame.” As with prominence, which showed variation over time and context, our instrument captured variations in valence. This respondent described how that sense of shame has changed “dramatically” since his adolescence: “[Now I] got no problems with anything.… My family, everybody, everything’s cool [with my bisexuality]. And this is the way I am, and I like me, I accept me.”

Stress and Resilience Related to Minority Identities

Our measure also allowed us to examine how identities interacted with different areas of life. The question about areas of life provided a context that can place more or less demands for adaptation and that can be more or less supportive of the person or of certain aspects of the self. The church has often been described as a source of stress related to LGB identities. As one 34-year-old Puerto Rican gay man said: “[The church] is currently a huge stress right now because my church does not accept homosexuality.” Several narratives described the church as a source of struggle, as their sexual identities were rejected by, and often hidden from, the church.

At the same time, the church can be an important source of support. One African American male respondent in his early twenties learned from his church that, “You’d go to hell if you are anything but straight. What am I doing that’s so wrong? … Why is God not happy with this [homosexuality]?” But he later moved to a more tolerant church, where “You can be who you are.” Although the new church became the most important source of social support for him, it was not an easy process:

I started going to an openly gay church. Then I stopped going there because I felt guilty, then I started going to, like, this other one that I’ve been going to for a while now, and I’m starting slowly going back… . You can just come to church and know that you’re going to be loved and respected and cared for and, you know, nobody’s going to think less of you or more of you just because, you know, you believe what you believe, or you live the life the way you do.

Others learned to accept their sexuality even within their religion and reframed their religiosity accordingly. A Puerto Rican lesbian, age 50, explained, “Now when I pray, I don’t say I’m sorry that I sinned because I slept with [Maria] again today. I say, ‘Thank you for this day, and thank you for giving me [Maria].’”

Family was also important as both a source of stress and support. A first generation Hispanic gay male, age 19, described the difficulties that family rejection posed:

Us Hispanic people, our family … if your family knows your sexual orientation in the Latino community, they’re very … they can’t accept that you’re gay… . It’s difficult to say that you are gay, to accept that, sometimes you think that you are bisexual, you think that you are doing wrong because that’s a sin.

Similarly, an African American gay man, age 45, from the South Bronx:

I get more flack for being gay from my family and stuff than I do from friends… . I mean, they [family members] call me names. My brother doesn’t really like me being around his, well, my nephew, and everything… Before I was OK, that I was babysitting, but once he found out I was gay, you can’t baby sit, and … if I take my other nephews out to the movies or something, I can’t take them to the movies unless I got somebody else, another adult with me and stuff.

But families also change and become supportive, as a Puerto Rican gay man, age 34, described:

When I first came out it was a big problem [for my family] but over the years things have improved. Every once in a while you hit a bump in the road where something might come up, where someone in the family might say something that might hurt. But then my defense mechanism is “They are still adjusting to this” something that I have lived with my whole life—they have only had a few years to adjust.

The 22-year-old Puerto Rican bisexual respondent who described shame that pervaded “just everything, everybody, everything,” explained that his family became a major source of support after he overcame the initial fear of disappointing them because of his bisexuality:

Matter of fact, my mother’s got a gay friend that lives down the hall. He’s got a crush on me for a while. My mother’s always trying to get me, hook me up with this guy … She was always telling me, you know, why don’t you? He’s a nice guy, you should try, you know, get together with him.

As social contexts shift so do stressors and demand for adaptation. The 34-year-old Puerto Rican gay man quoted above explained how he economizes on the need for adaptation depending on the social context.

When I refer to “public,” it’s any environment where people don’t know who I am or don’t know me very well, and where, I guess, I am sort of being evaluated in some sense, and where that evaluation might have an influence on my life. Because, if I go to the store or pharmacy to buy something and I do something where I am flagged as gay or whatever, I could really care less, and that’s sort of in the public. But in church or at work, where people don’t know me very well, and their evaluation or opinion of me may somehow affect my working relationship with them, then I need to have certain safeguards.

Resilient adaptation to broader contexts, such as immigration to a new city, was also captured by our instrument (Puerto Rican gay man, age 34):

I came to this country at the age of six I didn’t speak English at all … And so there was a lot of insecurities that developed as a child due to that … And that has, for instance, caused me at some point in my life turn my back on my heritage. And then later on in life realizing that my ethnicity is who I am, and had to sort of reinvent myself … and retract all those things that I’ve tried to change in myself.

Our instrument also showed how identities evoke internalized stressors, described in narratives as negative self-regard or anger. An example of the former—the internal turmoil over sexuality—was described earlier by a respondent who described his attraction to other men as “my biggest, darkest secret, my biggest shame.” But negative attitudes can be directed outward too. Another respondent, age 59, described herself as “Black aggressive gay woman angry at times” and a “disillusioned gay woman,” where anger and disillusionment were inherent in the self-label and immanent to the notion of self.

Interactions Among Identities and Between Identities and Social Contexts

One of our main aims in designing the instrument was to capture different ways that identities interact with one another and with social contexts: we describe these relationships as conjunct vs. disjunct. Our measure provided rich narratives that convey this. To illustrate this, we present descriptions of three of respondents in more extended form than we did above.

Conjunct identities

The first respondent is a White lesbian woman in her thirties who lives with her African American girlfriend in a middle/working class neighborhood and works in the public sector. This case illustrates a self-system that revolves around a main axis of the respondent’s sexual-political identity as a “lesbian,” the predominant feature of the respondent’s self-system. The sexual identity in the visual cue elicited the vernacular “lesbian” and “dyke.” The respondent expressed a heightened prominence of the sexual identity: “Yeah, I’m very out [as a lesbian]. I’m out to people on the streets.” The respondent called herself a “lesbian” as “a political move,” even though this “may not be an exact identifier,” given that she has had previous relationships with men. From the point of view of her sexual preference, she falls “somewhere in between the straight – lesbian scale.” But from the point of view of her sexual identity she is committed to a lesbian identity, which is at once sexual and political. This prominent political-sexual identity implied as well an “infinite opposition” against the majority establishment. Her sexual identity, overall, is prominent and has a positive valence. The respondent’s identity presentation does not vary depending on context: “I meet you for thirty seconds and I am out to you… in the supermarket… I don’t care.” As she feels “like an ambassador to my people,” she feels “acutely” aware of her actions, behavior, and speech “everywhere I go.”

Other identities, whether prominent or secondary, seem to be conjunct with her sexual orientation identity. For example, the race/ethnicity identity in the visual cue elicited the vernaculars “white girl” and “white bitch.” An important factor of this highlighted awareness is that the respondent has lived in an ethnic/racial minority community. “That has been a big part of my identity and the one that strikes me as the most obvious.” The respondent said she feels “very conscious of [being White]. Not that it is a bad thing, but I’m aware of it.” The respondent’s White identity was reported as neutral or negative; for example, she had been made highly “conscious of the privilege, White privilege.” Also, to be in “infinite opposition” against the mainstream seemed to imply a rather negative appraisal of whiteness, insofar as whiteness was included in the respondent’s understanding of the mainstream. The other self-descriptors provided in the visual cue (“progressive,” “feminist,” “rock-stable,” “writer,” etc.) are also “very fitting,” positive, and are mostly conjunct with the predominant sexual-political axis. Only in one place does she prefer not to be outspoken about her lesbian identity: “In most of my neighborhood [my girlfriend and I] we’d hold hands and be affectionate with each other, but we’ll drop hands when passing by [a straight, male-oriented bar where groups of men hang out outside].” This is self-protective ego-dystonic behavior, not a reflection of the true self as she perceived it, a result of knowing that a passer by was shot with a pistol by a man coming out from this bar. In every other “area of life” her identity self-descriptors are conjunctly presented and revolve around the sexual-political identity.

The notion that the respondent’s self-system overall implied a conjunct identity that revolved around a predominant feature of the identity was further suggested by the following response to the non-events query:

I completely identify with the angst of rebelling against the norm and … wanting things to be different, and I spend a lot of my energy, my time, my conversations, the music that I listen to, the movies I go to, the kind of parties that I go to, the kind of friends that I have, the kind of stuff I like to do is all connected somehow to the isms [homophobia, racism, and sexism]. [Otherwise] I can’t imagine what would be important to me. I don’t know what would be important to me [respondent’s verbal emphasis].

Disjunct identities

The second respondent is an African American lesbian woman in her late fifties with a history of incarceration and heroin use. Both the respondent’s racial and sexual identities were described as prominent and positive. But unlike the prior example, the two identities were disjunct. The respondent described this in her own words in response to the first question, when she was asked whether the self-descriptors she had entered on the visual cue “fit or don’t fit together”:

“Okay, say like [race/ethnicity], there’s no balance in that particular category, because, being a Black, and being a Black aggressive female … because there’s so much homophobia in my culture … so there’s no balance with being a Black and gay, and just being Black. It’s like total [pause, raising voice for emphasis] two separate entities! Like, Black [pause] even in my culture there’s a lot of things that I don’t like, as far as [being] a Black woman … even as a heterosexual Black woman, there’s too many responsibilities [respondent’s verbal emphasis]”

The respondent suggested that “in my culture” there is a divide between what is expected from males and females. This is exacerbated from the point of view of gay women:

Is just not enough of this compatibility between the sexes. So as a Black gay female is even less: more isolation, more disillusion about how we [both genders] are supposed to come together.… So there’s no balance as far as race [and sexual orientation].

In the previous example, the White lesbian respondent suggested that her lesbian identity implied meanings, values, and behaviors that were central to her sense of self and self-worth. Her lesbian identity, reportedly more positive and hence dominant over her White identity, thus provided a main existential domain for her, which was devoid of conflict between both identities. By contrast, in the present example both the racial/ethnic (“Black”) and the sexual (“gay”) identities were prominent and positive. Neither one was secondary. Additionally, the respondent thought that the institutional context (“the ideology of my culture”) was in conflict with one of her identities, “gay woman”—an identity that, given its importance, the respondent could not disown or render secondary. Here, the perceived external conflict between “gay community” and “Black community” was experienced as an internal conflict where being a “gay woman” clashed with being a “Black woman.”

On one hand, the respondent reported a positive identity as a “strong Black woman,” which, according to the narrative, was inherited from her culture and her mother (“a strong protective Black woman”). On the other hand, the respondent reported having “always” been “against [her] culture,” because her culture was in conflict with her sexual identity. Her Black culture, she explained, teaches to be “secretive about your personal business” and therefore places obstacles against having an open gay identity. As a result, the respondent reported feeling neither strongly connected to the gay nor to the Black community. She has been always “playing against the whole world … Never knew how to plug in … always been on the outside.” Yet, the respondent referred to a past sense of connection with the Black community, when she could be “very proud” of her culture’s “vision” and “[civil rights] politics,” to which she feels indebted.

Despite the disjunction between sexual orientation and race/ethnicity, there were some areas of conjunction. First, in at least one area, her “spiritual life,” the respondent has been able to find harmony between her race/ethnic and sexual orientation identities. After much searching, she found an African American church that teaches to be “peaceful and happy with yourself wherever you are at,” including her sexual identity.

Second, there was conjunction around other self-descriptors that connected with either the Black or gay identities or both. These identities included, as entered on the visual cue: “Educator,” “mediator,” “organizer,” and “caretaker.” All those “go together,” and were “connected” to her “Black” identity. The respondent felt that as a Black woman of her generation, she had to learn to be a caretaker from a very early age. “Black women,” she explained, have a strong culture as care givers—a culture that in her case ebbs into her identity as “Educator,” “mediator,” and “organizer.” These secondary positive and conjunct identities are also tangentially related to her identity as a gay woman. Being an “organizer,” implies at the same time an avowal of her cultural roots and a contestation against the “ideology of my race” in that as a “strong, aggressive Black gay woman,” and an “Educator” and “organizer,” she has been active against what she perceived as unfair heterosexist demands from institutional life. The “biggest part of me is being a Black, gay, aggressive woman,” where “aggressive” means always facing adversity and having to make choices “as well as being disillusioned. Those are the things that I repeat here.”

The third respondent is a Puerto Rican bisexual 22-year-old male briefly quoted above. He is HIV-positive, self-employed, and agnostic. His narrative also demonstrates themes of disjunctive identities. The narrative redounded around two themes that closely related to ethnic and the sexual identities: first, the respondent’s bisexuality “clashes” with his “Hispanic” identity. Second, bisexuality is also described in conflict with developing a stable relationship with women.

Similar to the Black woman described before, this respondent sensed that his “Hispanic culture” is not accepting of his bisexuality. In this case, there were intersections of gender and masculinity, Hispanic culture and heritage, and the gay community. Even the gay community clashes with his bisexual identity, a part of which is being a “strong male.” Gay culture is not consistent with his “Hispanic” [and masculine] appearance on account of the fact that, “I guess I portray… a straight guy from South Bronx, from the ghetto.” For example, the respondent recalls being questioned about his sexuality by a bouncer upon entering a gay bar (“Are you gay?”). He answered: “Listen, I’m just as gay as anybody here.” More generally, the gay “style” is very different than his style. He finds that gay clothing stores display tight-fitting nylon shirts but he wears loose cotton shirts. “The sneakers that they wear are different.” Some “gay people think that you have to be either gay or straight but I am neither—just because you don’t like women, that doesn’t mean that I don’t like women, you know. I like them as much as I like men.” “It is really annoying and frustrating, especially when you want to be a part of it [the gay community].”

The respondent also described conflicts between his identity as a bisexual man who is “bisexually active” and his desired role as a boyfriend to a woman. These conflicts are related to his conception of gender (“women are more nurturing”) as well as his conception of “gay” and “straight.” The conflict revolves around wanting to have sex with men and wanting an intimate relationship with a woman. The respondent does not “want to lose” his girlfriend but at the same time does not want to give up being “actively bisexual.” He feels that “gay men do not offer emotional [support], can’t have the kind of intimacy with them that you can have with a woman.” Men are better sexually, but women have “more emotional substance.” As a result he has had difficulty having a “real” relationship with a man – he feels that he has been “used” by gay men. In contrast, “women are more nurturing that way.” He has only had one steady relationship with a gay man, but broke up with him because he “couldn’t accept the girls.” Therefore, the respondent feels “all the time” that he has to make choices between being a “gay guy or totally straight.” But he cannot “be two people,” that is, he cannot separate his sexual needs for women and men. He has tried to be “straight” with a girlfriend but realized that he will always be bisexual. “I do have that need, that desire to have sex with a man.” Responding to the cue about non-events the respondent said that in “the ideal world” without homophobia or sexism, he would be married but his wife would be able to accept his bisexuality—she would take him to a gay strip club and give him money to put in the go-go boy’s jockstrap.

Discussion

We described a qualitative instrument of identity and related stressors. The instrument provides a new approach to studying intersectionality of minority identities. In this paper we set out to demonstrate that interviews using this instrument yield rich information describing minority identities and interactions of these identities with other identities, roles, and social contexts. Researchers who want to assess identity often resort to using separate measures for race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and other target identities and roles. But these can miss elements of a self-system that stem from the intersection of identities, interactions between identities and social contexts, and related shifts in identity over time. Our approach to measuring identity overcomes problems related to studying minority identities as decontextualized, parallel, additive constructs.

Stewart and McDermott (2004) suggested that researchers have to locate people contextually, “in terms of social structures that capture the power relations implied by those structures” (p. 532). Using a small sub-sample we demonstrated that our instrument can help researchers better understand how people who hold multiple minority identities interact with social structures involved in institutions such as family and work. First, our approach enabled us to show how identities are stamped by power relations implied by these institutions; for example, the respondents who, to varying degrees, deactivated their gay identities in contexts such as church or work. Second, our instrument allowed us to show how people recapture power relations endorsed by the same structures; for example, the respondent who in the past prayed for forgiveness for her lesbianism and now thanked God for it. Third, the instrument allowed us to show how people move away from social structures, detach themselves from their symbolic demands, and actively participate in alternative settings, thereby recapturing alternative allocations of social or cultural capital. For example, the respondent who in the past tended to hide her “masculine woman” presentation and now, after “discovering” the “butch community,” discovered as well new social and sexual self-worth. We demonstrated how the instrument can help assess prominence and valence of minority identities and show how these dimensions can vary longitudinally, as seen through the respondents who came to terms with identities after years of self-rejection, or shift along with the individual’s actions and reactions related to social environments. We also demonstrated how the rich narratives allowed us to analyze the intersection of identities along a continuum of conjunction or disjunction in the self system, and how they are related to stress and resilience.

By allowing respondents to describe the intersection of identities, the instrument can help researchers find patterns that could not be revealed using traditional methods that assess each identity independently and outside social contexts. Respondents such as the Black woman with strong positive Black and gay identities might look differently on measures that assess race/ethnicity and sexual orientation independently. Using our instrument, we were able to examine the intersection of and compatibility between these identities. The positive and strong character of each identity appeared different when reflected through other identities (Deaux & Perkins, 2001). Also, unlike measures that provide snapshots of identity, devoid of context and temporality, our approach allowed us to examine the identity’s contextual and temporal dimensions. Significantly, unlike most qualitative approaches, which require lengthy interviewing and time-consuming analysis of narratives, our instrument provides economy in administration and analysis, which makes it feasible for use in large survey research as a complement to quantitative measures.

The instrument also has limitations. Importantly, unconscious elements of self-systems such as those captured by the notion of habitus (Bourdieu, 1990), which imply pre-reflective disposition related to the intersection of bodily, mental, and social schemata, fall outside this instrument. Also, the instrument is not suitable to all populations. It calls for a minimum of affective and cognitive investment in the task. The respondent is asked to disclose subjective notions about the self and to reflect on the relevance and relative weight of different identities. The respondent is also asked to search for identity labels and relatively quickly identify their relevance to the self-system. Some command of language is necessary to produce figures of speech (synecdoche, metaphor, simile) and the ability to use the visual cue to produce an illustrative narrative. The respondent—and, with him or her, the interviewer—thus construct identities that are subjective, metaphorical, and reflexive. The quality of data is dependent on the respondent’s and the interviewer’s ability to engage in the task.

Future studies can apply our strategy to examine how minority individuals and groups—by adopting, negotiating, and creating identities—thus craft their experience within larger cultural contexts and over time. The instrument can throw light, as well, on how social institutions—through impingements, tensions, constraints, and/or support—can be a means through which individual and collective identities are activated, performed, and lived.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health, grant number MH066058 (Ilan H. Meyer, Principal Investigator). The authors thank Rebecca Young, Michael Roguski, and Danielle Beatty for their contribution to the development of the qualitative assessment reported here.

References

- Angrosino MV. Metaphors of Stigma: How Deinstitutionalized Mentally Retarded Adults see Themselves. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography. 1992;21:171–199. [Google Scholar]

- Ashmore RD, Deaux K, McLaughlin-Volpe T. An Organizing Framework for Collective Identity: Articulation and Significance of Multidimensionality. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130(1):80–114. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. In: The Logic of Practice. Nice R, translator. Stanford University Press; Stanford, CA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Contrada RJ, Gary ML, Coups E, Egeth JD, Sewell A, Ewell K, et al. Measures of Ethnicity-Related Stress: Psychometric Properties, Ethnic Group Differences, and Associations with Well-Being. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2001;31(9):1775–1820. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford I, Allison KW, Zamboni BD, Soto T. The Influence of Dual-Identity Development on the Psychosocial Functioning of African-American Gay and Bisexual Men. Journal of Sex Research. 2002;39(3):179–189. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw KW. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color. In: Crenshaw KW, Gotanda N, Peller G, Thomas K, editors. Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings that Formed the Movement. New Press; New York: 1996. pp. 357–383. [Google Scholar]

- Deaux K, Perkins TS. The Kaleidoscopic Self. In: Sedikides C, Brewer MB, editors. Individual Self, Relational Self, Collective Self. Taylor & Francis; Philadelphia: 2001. pp. 299–313. [Google Scholar]

- DeBoeck P, Rosenberg S. Hierarchical Classes: Model and Data Analysis. Psychometrika. 1988;53(3):361–381. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research. 2nd ed Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dowsett GW. Practicing Desire: Homosexual Sex in the Era of AIDS. Stanford University Press; Stanford, CA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis C, Bochner AP. Autoethnography, Personal Narrative, Reflexivity: Researcher as Subject. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2000. pp. 733–768. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn NE. The Social Construction and Institutionalization of Gender and Race. In: Ferree M. Marx, Lorber J, Hess BB., editors. Revisioning Gender. AltaMira Press; Walnut Creek, CA: 2000. pp. 3–43. [Google Scholar]

- Gurin P, Townsend A. Properties of Gender Identity and their Implications for Gender Consciousness. British Journal of Social Psychology. 1986;25(2):139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson-King DH, Stewart AJ. Women or Feminists? Assessing Women’s Group Consciousness. Sex Roles. 1994;31(9-10):505–516. [Google Scholar]

- Henley NM, Meng K, O’Brien D, McCarthy WJ, Sockloskie R. Developing a Scale to Measure the Diversity of Feminist Attitudes. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1998;22(3):317–348. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn MH, McPartland TS. An Empirical Investigation of Self-Attitudes. American Sociological Review. 1954;19:68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Madriz E. Focus Groups in Feminist Research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2000. pp. 835–850. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, Social Stress and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations: Conceptual Issues and Research Evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(3):674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr J, Fassinger R. Measuring dimensions of lesbian and gay male experience. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development. 2000;33:66–90. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure: A New Scale for Use with Diverse Groups. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1992;7(2):156–176. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg S, Gara MA. The multiplicity of personal identity. In: Shaver P, editor. Review of Personality and Social Psychology. Vol. 4. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1985. pp. 87–113. [Google Scholar]

- Rust PC. Garnets LD, Kimmel DC, editors. Finding a Sexual Identity and Community: Therapeutic Implications and Cultural Assumptions in Scientific Models of Coming Out. Psychological Perspectives on Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Experiences. (2nd Edition) 2003:227–269. [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC, Diamond LD. Sexual Identity Trajectories Among Sexual Minority Youths: Gender Comparisons. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2000;29(6):607–627. doi: 10.1023/a:1002058505138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Smith MA, Shelton JN, Rowley SAJ, Chavous TM. Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity: A Preliminary Investigation of Reliability and Construct Validity. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 1998;2:18–39. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference. Houghton Mifflin Company; Boston, MA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AJ, McDermott C. Gender in Psychology. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:519–544. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirratt M, Meyer I, Ouellette SC, Gara M. Measuring Identity Multiplicity and Intersectionality: Hierarchical Classes Analysis (HICLAS) of Sexual, Racial, and Gender Identities. (N.d. unpublished)

- Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/Ethnic Discrimination and Health: Findings From Community Studies. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:200–208. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf M. A Thrice-Told Tale: Feminism, Postmodernism, and Ethnographic Responsibility. Stanford University Press; Stanford, CA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Zucker AN. Disavowing Social Identities: What it Means When Women Say, ‘I’m a feminist, but…’. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2003;28:423–435. [Google Scholar]