We assessed the frequency and severity of adverse events (AEs) in 53 patients with Chagas disease treated with nifurtimox in a US clinic. There were 435 AEs, but 93.8% were mild. Moderate/severe AEs were associated with premature treatment cessation.

Keywords: Chagas disease, Trypanosoma cruzi, nifurtimox, benznidazole, side effects

Abstract

Background. Nifurtimox is 1 of only 2 medications available for treating Chagas disease (CD) and currently the only drug available in the United States, but its safety and tolerance have not been extensively studied. This is the first study to evaluate tolerance of nifurtimox in US patients with CD.

Methods. This investigation assessed side effects in a sample of 53 patients with CD, all Latin American immigrants, who underwent treatment with nifurtimox (8–10 mg/kg in 3 daily doses for 12 weeks) from March 2008 to July 2012. The frequency and severity of adverse events (AEs) was recorded.

Results. A total of 435 AEs were recorded; 93.8% were mild, 3.0% moderate, and 3.2% severe. Patients experienced a mean of 8.2 AEs; the most frequent were anorexia (79.2%), nausea (75.5%), headache (60.4%), amnesia (58.5%), and >5% weight loss (52.8%). Eleven patients (20.8%) were unable to complete treatment. Experiencing a moderate or severe AE (odds ratio [OR], 3.82; P < .05) and Mexican nationality (OR, 2.29; P < .05) were significant predictors of treatment discontinuation, but sex and cardiac progression at baseline were not. Patients who did not complete treatment experienced nearly 3 times more AEs per 30-day period (P = .05).

Conclusions. Nifurtimox produces frequent side effects, but the majority are mild and can be managed with dose reduction and/or temporary suspension of medication. The high frequency of gastrointestinal symptoms and weight loss mirrors results from prior investigations. Special attention should be paid during the early stages of treatment to potentially severe symptoms including depression, rash, and anxiety.

Nearly 6 million people worldwide are infected with Trypanosoma cruzi, the protozoan that causes Chagas disease (CD) [1]. Once predominantly confined to rural areas of Latin America, CD has spread in step with migration to urban centers and nonendemic countries in Europe, North America, and the Pacific [2]. An estimated 300 000 Latin American immigrants in the United States currently live with the infection, up to 45 000 with cardiomyopathy [3]. The vast majority are undiagnosed and untreated [4]. Moreover, due to high costs of procedures for treating cardiac complications in the United States, estimated annual CD healthcare expenses are nearly $120 million, second only to Brazil [5].

Clinically, CD is characterized by a brief acute phase with variable, usually mild symptoms, followed by an asymptomatic indeterminate phase that is lifelong in the absence of treatment. However, 30%–50% of those in the indeterminate phase progress to the chronic stage of CD, which is most often characterized by cardiomyopathy associated with apical aneurysms, ventricular tachycardia, and sudden cardiac death. CD can also take a gastrointestinal or cardiodigestive form, particularly among people originally infected in the Southern Cone of South America [6, 7]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends offering antitrypanosomal treatment to patients with acute or indeterminate CD. For patients aged >50 years, the merits of treatment should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis [8].

Currently, the only medications effective against T. cruzi are benznidazole and nifurtimox. Both are most effective in young patients at early stages of infection. Cure rates approach 100% for congenitally infected newborns and surpass 60% for acute cases [8–10]. For patients in the indeterminate phase, treatment success is difficult to measure with serologic assays; seroreversion may not be evident for years following treatment. Whereas development of chronic CD was once attributed to the body's autoimmune response, the current consensus is that parasite persistence is key to triggering this stage of the disease [11]. Evidence suggests there is significantly less progression toward chronic symptoms for patients who undergo treatment, and a cure, defined as conversion to negative serology, can be achieved in a substantial portion of patients in the indeterminate phase [12, 13]. Contraindications include pregnancy, advanced cardiac progression, and hepatic or renal complications. The Benznidazole Evaluation for Interrupting Trypanosomiasis trial, which found no advantage to treating patients in the chronic phase who exhibited moderate cardiomyopathy [14], underscores the importance of treating patients before significant complications develop.

Both benznidazole and nifurtimox produce adverse events (AEs) that increase in frequency and intensity with the age of the patient [10, 15]. Benznidazole is the preferred treatment because of its lower incidence of AEs and shorter treatment duration [6, 16]. Nonetheless, allergic dermatitis is a frequently observed side effect of benznidazole capable of disrupting treatment completion [17, 18]. Additionally, due to supply issues, benznidazole is currently unavailable in the United States [19]. Few studies have evaluated the tolerance of nifurtimox in adult patients, but they indicate that gastric, psychiatric, and neurological complications are the most common AEs [15, 20, 21].

Little is known about the tolerance of CD medications among patients in the United States. The only prior study found that 93% of patients treated with benznidazole had multiple AEs, with 40% suffering moderate to severe AEs; rash was the most frequent outcome [18]. In the present study, we examine the tolerance of nifurtimox for treatment of CD in a sample of adult Latin American immigrants in Los Angeles, California. This is of utmost importance because (1) nearly all people with CD in the United States are undiagnosed and untreated [4]; (2) nifurtimox is a viable treatment alternative for patients who cannot tolerate benznidazole [22]; and (3) the supply of benznidazole is subject to disruption [23].

METHODS

Setting

The Center of Excellence for Chagas Disease (CECD) at the Olive View–University of California, Los Angeles Medical Center is the only institution wholly dedicated to the systematic treatment of CD in the United States. Olive View Medical Center is a public, academically affiliated facility serving the County of Los Angeles, home to nearly 2.5 million Latin American immigrants [24]. It is a safety-net facility providing care to the underserved population in Los Angeles County, regardless of income or insurance status. The CECD emerged from a growing recognition that the US public health system is largely unaware of (and unprepared to cope with) CD [25]. Through a combination of community outreach/screening, patient referral of family members, and referrals from blood banks, the CECD has thus far identified approximately 300 patients living with T. cruzi infection among the Latin American immigrant population in Los Angeles.

Participants and Procedures

All patients who were positive for T. cruzi infection and treated with nifurtimox at CECD between March 2008 and July 2012 were asked to participate in this prospective cohort study. We stopped data collection in 2012 when CECD was able to obtain benznidazole from the CDC. Positive diagnosis was ascertained through enzyme immunoassay with confirmation via either a Chagas radioimmune precipitation assay (n = 24) or immunofluorescent antibody titer ≥1:32 (n = 29). Patients aged >60 years or with advanced cardiac progression, impaired renal or hepatic functions, or other serious comorbidities were ineligible for treatment. All eligible patients received risk-benefit consultation and signed informed consent prior to treatment. The study received ethical approval from the institutional review board of the Olive View-UCLA Education and Research Institute.

Nifurtimox was obtained from the CDC through a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) investigational protocol. We administered nifurtimox at 8–10 mg/kg divided into 3 daily doses for 12 weeks, per CDC recommendations at the time [8]. We encouraged patients to contact investigators in case of medical problems during the treatment period. If patients experienced significant discomfort from side effects, we temporarily suspended treatment. At the discretion of the medical team, and depending on the severity of each case, we modified the regimen for these patients by reducing the daily dosage by 50%, and extending the treatment period accordingly to allow for completion of the full regimen of medication.

Data Collection

At baseline, we administered a clinical evaluation, chest radiograph, electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, and 24-hour Holter test to each patient. We collected medical histories from patients and reviewed charts to detect prior conditions. Patients were evaluated biweekly during the treatment period, and at 30 days and 1 year postcompletion. Evaluations consisted of a physical examination and monitoring of hepatic function, blood count, and serum chemistries. Investigators reviewed a checklist of common adverse reactions with each patient to gauge frequency of occurrence, and asked patients to report any reactions not included on the checklist. If patients missed a follow-up visit, we reviewed AEs via telephone. For each AE recorded, we assigned a severity level based on the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.03 (1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe, 4 = life threatening) [26].

Statistical Analysis

Computations included mean age, median length of treatment, and mean number of AEs per patient. Because of the varying treatment durations, the number of AEs was divided by total days of treatment and multiplied by 30 to get an idea of the mean number of AEs experienced per month. We compared different factors impacting treatment completion by calculating odds ratios (ORs) with confidence intervals and analyzing Kaplan–Meier survival curves. We tested for correlations between age and total number of AEs, AEs per 30 days, and number of moderate or severe AEs. To test for significance, we used, as appropriate, χ2 or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables, Mann–Whitney U tests or Spearman rank-order correlations for continuous variables, and log-rank tests for survival analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 23.0 (IBM SPSS, Armonk, New York).

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

One eligible patient refused participation, and 2 were treated but excluded from this analysis because they were <18 years of age. The remaining 53 patients met the inclusion criteria. Most patients were female (n = 37 [69.8%]), which mirrors the patient composition of the CECD (Table 1). This is driven by the CECD's outreach efforts, which have involved churches and other community organizations with preponderantly female participation. All patients were Latin American immigrants; the largest proportion was born in El Salvador (n = 29 [54.7%]), followed by Mexico (n = 16 [30.2%]), Guatemala (n = 4 [7.5%]), Honduras (n = 2 [3.8%]), and Argentina (n = 2 [3.8%]). At baseline, 9 patients had right bundle branch block (17.0%) while 3 (5.7%) exhibited mild cardiomyopathy (ejection fraction 45%–50%).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 37 | 69.8 |

| Male | 16 | 30.2 |

| Age | ||

| 26–39 | 15 | 28.3 |

| 40–49 | 12 | 22.6 |

| ≥50 | 26 | 49.1 |

| Nationality | ||

| Salvadoran | 29 | 54.7 |

| Mexican | 16 | 30.2 |

| Guatemalan | 4 | 7.5 |

| Honduras | 2 | 3.8 |

| Argentina | 2 | 3.8 |

| Cardiac progression at baseline | ||

| Right bundle branch block | 9 | 17.0 |

| Mild cardiomyopathy | 3 | 5.7 |

| None | 41 | 77.4 |

Types of AEs

All 53 patients in the study experienced AEs, with 435 total AEs recorded (Table 2). The majority (n = 33 [62.3%]) reported symptom onset within the first 2 weeks of treatment. All but 2 patients (96.2%) experienced multiple AEs; the other 2 only experienced 1 AE, but in each case it was severe enough to force discontinuation of treatment. In all, 11 patients (20.8%) were unable to complete treatment: 10 due to AEs and 1 because of loss to follow-up. The most frequently occurring AEs were anorexia (79.2% of patients), nausea (75.5%), headache (60.4%), and amnesia (58.5%). Psychiatric AEs were also common; nearly half of patients experienced anxiety and insomnia. Eight patients reported rash, including nonitchy pinpoint (n = 3), nonitchy erythematous (n = 1), and 2 severe cases of maculopapular rash requiring immediate cessation of treatment, and in 1 case admission to the ER.

Table 2.

Type, Frequency, Severity, Onset, and Duration of Adverse Events

| Adverse Event | Frequency (AEs, % of Patients Reporting) | Severity (Frequency, % Within AE Category) |

Time of Onset, d, Median (Range) | Duration, Median | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: Mild | 2: Moderate | 3: Severe | ||||

| Gastrointestinal | ||||||

| Anorexia | 43 (79.2) | 40 (93.0) | 3 (7.0) | 0 | 21 (1–119) | 29.5 (6–90) |

| Nausea | 40 (75.5) | 37 (92.5) | 2 (5.0) | 1 (2.5) | 21 (1–119) | 40.5 (6–91) |

| Abdominal pain | 26 (49.1) | 25 (96.2) | 1 (3.8) | 0 | 34 (1–84) | 23.5 (1–113) |

| Vomiting | 19 (35.8) | 19 (100) | 0 | 0 | 27 (1–94) | 22.5 (3–71) |

| Neurological | ||||||

| Headache | 33 (60.4) | 31 (94.0) | 1 (3.0) | 1 (3.0) | 21 (1–144) | 28 (4–109) |

| Amnesia | 31 (58.5) | 31 (100) | 0 | 0 | 27 (14–93) | 30 (8–123) |

| Somnolence | 17 (32.1) | 15 (88.2) | 0 | 2 (11.8) | 18 (1–119) | 20 (7–65) |

| Blurry vision | 15 (28.3) | 14 (100) | 0 | 0 | 42 (14–80) | 33 (13–77) |

| Hand tremor | 14 (26.4) | 14 (100) | 0 | 0 | 29 (13–80) | 27.5 (14–65) |

| Paresthesia | 8 (15.1) | 8 (100) | 0 | 0 | 60 (18–83) | 49 (14–77) |

| Peripheral neuropathy |

6 (11.3) | 5 (83.3) | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 80 (14–99) | 28 (21–63) |

| Disorientation | 4 (7.5) | 4 (100) | 0 | 0 | 34 (23–84) | 28 (18–41) |

| Psychiatric | ||||||

| Anxiety | 26 (49.1) | 23 (88.9) | 1 (3.7) | 2 (7.4) | 28 (8–70) | 49 (6–94) |

| Insomnia | 26 (49.1) | 23 (88.5) | 2 (7.7) | 1 (3.8) | 22 (7–93) | 43 (7–133) |

| Depression | 14 (26.4) | 11 (78.6) | 0 | 3 (21.4) | 28 (14–97) | 25 (11–48) |

| Musculoskeletal | ||||||

| Arthralgia | 26 (49.1) | 24 (92.3) | 2 (7.7) | 0 | 28 (1–119) | 32 (4–94) |

| Myalgia | 17 (32.1) | 16 (94.1) | 1 (5.9) | 0 | 18 (1–64) | 31.5 (8–155) |

| Dermatological | ||||||

| Rash | 8 (15.1) | 6 (75.0) | 0 | 2 (25.0) | 11 (1–42) | 10 (1–24) |

| Constitutional | ||||||

| >5% weight loss | 28 (52.8) | 24 (85.7) | 4 (14.3) | 0 | 27 (18–52) | 60 (50–70)a |

| Fatigue | 22 (41.5) | 19 (86.4) | 1 (4.5) | 2 (9.1) | 28 (8–80) | 34 (7–88) |

| Other (dry mouth = 4, diarrhea = 3, night sweats = 2, weakness = 2, vertigo = 1) | 12 (18.7)b | 12 (100) | 0 | 0 | 41 (14–68) | 21 (14–70) |

| All AEs | 435 (100) | 408 (93.8) | 13 (3.0) | 14 (3.2) | 27 (1–144) | 28.5 (1–155) |

Abbreviation: AE, adverse event.

a Data only available for 2 patients.

b These 12 AEs occurred in 10 patients.

Only 1 patient had prior depression at baseline; the other 13 cases of depression developed during the treatment period. No patient reported prior history of amnesia. However, 1 individual was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease 2 years after completing treatment, so this patient's mild amnesia during the study period could have been an early sign/symptom of Alzheimer's disease.

Animal and experimental studies have demonstrated both laboratory evidence of nifurtimox's mutagenicity and an increase in solid tumors in animal models treated with this agent [27, 28]. Therefore, we reviewed each patient's chart for any cancer-related diagnoses. One patient developed peritoneal carcinomatosis in 2013, 18 years after mastectomy for breast cancer and 3 years after completing nifurtimox treatment in 2010. Another patient developed breast ductal carcinoma in situ in 2013, 4 years after completing nifurtimox treatment in 2009. Otherwise, no incident cancers were observed during the study follow-up period.

Severity

The majority of AEs (93.8%) were mild (Table 2). Only 3% were moderate and 3.2% severe, while no one experienced life-threatening or fatal AEs. Moderate and/or severe AEs affected 14 patients (26.4%). The most serious, requiring immediate discontinuation of treatment, involved 1 case of severe depression and another of maculopapular rash. Depression affected 26.4% of patients, but was the most frequently observed severe AE (n = 3 [5.7%]). Anxiety, somnolence, and rash were severe in 2 patients each (3.8%). More than 5% weight loss occurred in nearly half of patients (mean weight loss, 9.0 pounds), and in 4 individuals exceeded 10%.

Frequency

Patients experienced a mean of 8.2 AEs (Table 3), with a mean length of treatment of 79 days. Age was not significantly correlated with total AEs or AEs per 30 days, and the presence of moderate or severe AEs was not significantly associated with age. Although females and those with cardiac progression (cardiomyopathy or bundle branch block) had slightly more AEs, the differences were not significant. To compare relative frequency of AEs, we examined the number experienced per 30 days. Those who did not complete treatment experienced more AEs per 30 days (8.54 vs 2.95; P = .05). There was also a trend toward more frequent AEs in Mexican patients, but the difference was not significant.

Table 3.

Frequency of Adverse Events, by Patient Group

| Category | Mean Age, y | Mean AEs | Mean Length of Treatment, d | P Value | Mean AEs per 30 d | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 48.3 | 8.20 | 79.09 | 4.11 | ||

| Completed treatment (n = 42) | 48.2 | 8.52 | 91.26 | .082 | 2.95 | .05 |

| Did not complete treatment (n = 11) | 48.9 | 6.27 | 32.64 | 8.54 | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male (n = 16) | 48.4 | 7.13 | 73.38 | .600 | 3.73 | .362 |

| Female (n = 37) | 48.7 | 8.65 | 81.57 | 4.28 | ||

| Cardiac progression | ||||||

| Right bundle branch block or mild cardiomyopathy (n = 12) | 53.8 | 8.83 | 77.92 | .543 | 3.63 | .603 |

| No cardiac progression (n = 41) | 46.7 | 8.00 | 79.44 | 4.25 | ||

| Mexican nationality (n = 16) | 48.1 | 7.50 | 68.63 | .460 | 5.89 | .389 |

| Other nationality (n = 37) | 48.4 | 8.49 | 83.62 | 3.34 | ||

Abbreviation: AE, adverse event.

Treatment Completion

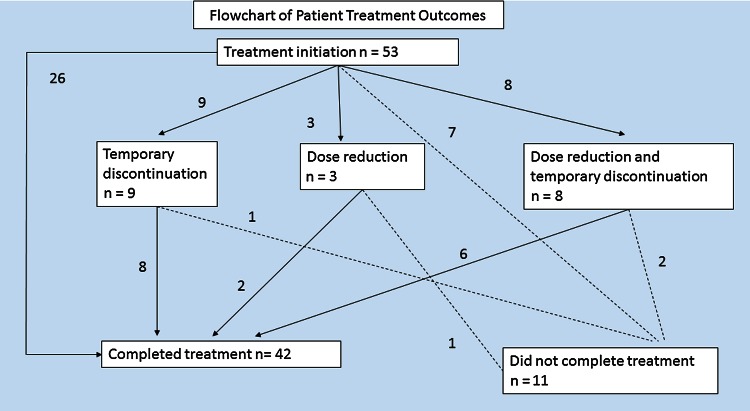

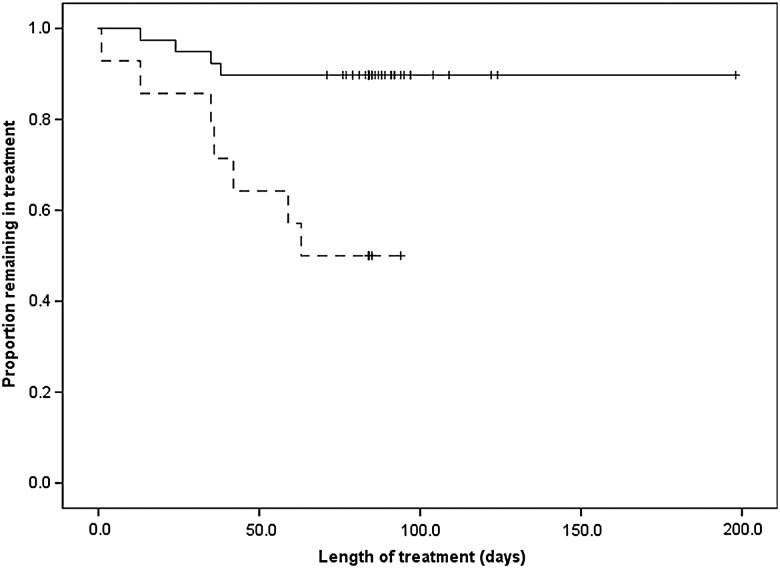

Of the 42 patients who completed treatment, 2 required dose reductions, 8 underwent temporary suspension of treatment, and 6 had both (Figure 1). Five of the 14 interruptions in this group were due to AEs and 9 were from other factors such as running out of medication. Four patients required dose reduction (n = 1), temporary suspension of treatment (n = 1), or both (n = 2), but were still unable to complete the regimen. Although overall number of AEs was not associated with prematurely terminating treatment, experiencing moderate or severe AEs was a significant risk (OR, 3.82; P = .004; Table 4). In a survival analysis, the difference in completion between patients with and without moderate/severe AEs was significant in a log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test (P = .001). Mexican patients were more likely to stop treatment (OR, 2.29; P = .05), and 3 times as likely to experience moderate or severe AEs (Table 4), although the difference was only significant at P < .1.

Figure 1.

Patient treatment outcomes. = Patients moving toward premature termination.

= Patients moving toward premature termination.  = Patients moving toward treatment completion.

= Patients moving toward treatment completion.

Table 4.

Risk Analysis

| Risk Factor | Odds Ratio | Confidence Interval | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment discontinuation | |||

| Male sex | 0.72 | .51–3.2 | .72 |

| Mexican nationality | 2.29 | 1.07–4.92 | .05 |

| Cardiac progressiona | 1.27 | .41–3.92 | .70 |

| Moderate or severe AEs | 3.82 | 1.70–8.59 | .004 |

| Moderate or severe AEs | |||

| Male sex | 0.55 | .13–2.30 | .51 |

| Mexican nationality | 3.33 | .92–12.06 | .09 |

| Cardiac progressiona | 0.91 | .21–3.99 | 1.0 |

Abbreviation: AE, adverse event.

a Right bundle branch block or mild cardiomyopathy.

We did not find a relationship between dosage and AEs. Initial dosage was not correlated with total AEs or AEs per 30 days. Mean starting dosage was actually higher (600.8 mg) in patients who did not experience moderate or severe AEs compared with others (580.7 mg), and the difference was not significant.

DISCUSSION

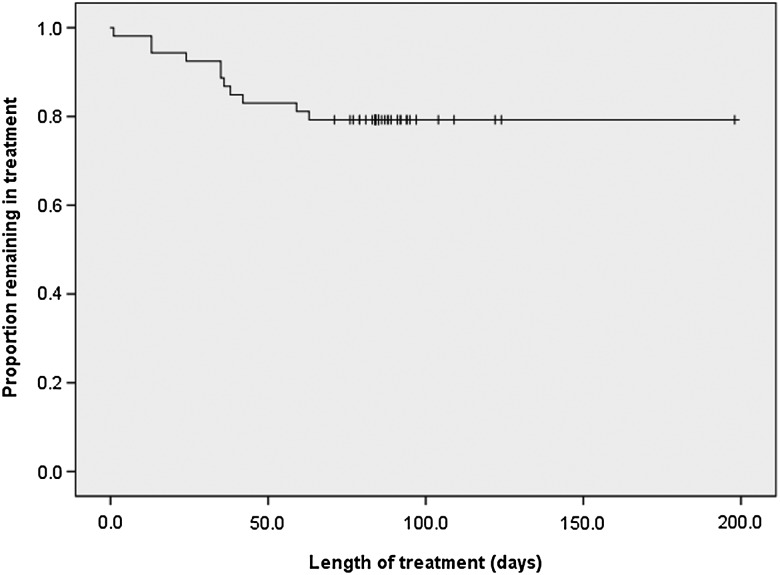

This is the first study to assess the safety and tolerance of nifurtimox for treatment of adults with CD in the United States. Nifurtimox produces frequent AEs in adult patients, but the bulk of these (93.8%) are mild and can be managed through temporary discontinuation of treatment or dose reduction. Moderate to severe symptoms, occurring in 26.4% of patients, and more frequent AEs per 30 days predicted premature termination of treatment. Nonetheless, 79.2% of patients completed the full 90-day course of medication. By comparison, 70% of patients in a separate study at CECD were able to complete a full regimen of benznidazole [18].

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curve showing the proportion of patients successfully completing treatment.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curve showing severity of adverse events (AEs) and proportion of patients completing treatment. Solid line is patients with mild AEs only; dotted line is patients with moderate or severe AEs.

Patients in our study frequently suffered from gastrointestinal complications, especially nausea and anorexia, which mirrors findings from prior investigations of nifurtimox tolerance in adults [15, 20, 21]. Valencia et al observed weight loss in 80.6% of 60 adult patients treated with nifurtimox in Chile [20], compared with 49.1% in our study who had >5% weight loss. Similarly, loss of appetite is a common symptom for children treated with nifurtimox [29]. Unlike prior studies, we assessed the impact of psychiatric symptoms, including anxiety (49.1%) and depression (26.4%), which in 3 cases was severe and resulted in treatment disruption. Two of the patients with severe depression also experienced severe anxiety. This suggests a need for mental health screening and support for patients who undergo treatment with nifurtimox.

Whereas Jackson et al found that completion rates were lower for patients who experienced >3 AEs [15], we only observed this effect when we compared mean number of AEs per 30 days. This is because patients who dropped out of treatment early had less of an opportunity to experience new AEs than those who took the full regimen of nifurtimox, and early but significant AEs caused 10 patients to terminate treatment. Similar to Olivera et al, we observed a higher premature termination rate in response to increasing severity of AEs [21]. Although we did not detect a relationship between starting dosage and frequency or severity of AEs, this does not exclude the possibility that current dosages of nifurtimox need adjustment to improve tolerance, as has been suggested for benznidazole [30, 31]. More research is needed to determine the mechanisms and processes contributing to the toxicity of the drug and the associated high incidence of AEs.

Despite frequent AEs, the majority of patients (79.2%) were able to complete the full 90-day course of medication. This is remarkably similar to the completion rate (79%) observed by Olivera et al [21], and much higher than that (43.8%) reported by Jackson et al [15]. More than 90% of AEs observed by Jackson et al were mild, but the authors attributed the high attrition rate to patients experiencing several AEs simultaneously. The different completion rates may reflect the migratory and social contexts affecting the experience of each patient group. Olivera et al studied Colombians in Colombia and Jackson et al enrolled mostly Bolivian patients in Switzerland. Our study found that rates of premature termination and moderate or severe AEs were higher among Mexican patients. However, we suspect that other explanatory variables that were not collected as part of our study, such as income or occupation, could be the underlying cause of this disparity. Notably, we did not detect significant differences in frequency or severity of AEs based on age or sex.

Although benznidazole is the preferred treatment for CD, at the time this article was written, its availability was in question. Benznidazole and nifurtimox both lack FDA approval, and are only available through investigational protocols from the CDC, yet the CDC does not have a current contractual agreement with the lone functional supplier of benznidazole [19]. (The CDC's usual supplier in Brazil recently promised to resume production.) Existing supplies of benznidazole are dwindling, making nifurtimox the only viable medication in the United States for treating CD in the near future. Similarly, a shortage of benznidazole from 2010 to 2012 caused delays or suspension of treatment in several countries [23]. The nifurtimox supply is more stable. In 2004, Bayer Laboratories, which had halted production of nifurtimox in 1997 due to lack of profitability, signed an agreement with the World Health Organization guaranteeing provision of 500 000 tablets of nifurtimox annually free of charge. In a new agreement in 2011, Bayer increased this to 1 million tablets annually [32].

There were limitations to this study. Although this study is the largest of its type in the United States, it was conducted at a single center with a specific geographical selection bias, and the scope and granularity of data collected were limited by resources available. The only demographic information we collected was age, sex, and nationality. This and the small sample size prevented us from performing multivariate analysis or accounting for potential confounders, thus constraining our ability to explain differences between groups.

In sum, nifurtimox produces frequent AEs in adult patients, but the bulk of AEs are mild and can be managed through temporary discontinuation of treatment or dose reduction. Severe AEs are most likely to appear in the first month of treatment, making vigilance especially important during this phase, particularly for dermatological and psychiatric disorders. With benznidazole's availability limited by supply constraints and regulatory barriers, carefully controlled administration of nifurtimox remains essential for current CD eradication efforts in the United States and worldwide. Registration of both nifurtimox and benznidazole would greatly facilitate the much-needed expansion of treatment of CD in the United States, which should occur at a primary care level to improve patient access. With 99% of US patients untreated, there is an immense need for national strategies and additional facilities dedicated to Chagas treatment. Development of safer, effective drugs for CD is still years away [30], and treatment with nifurtimox can potentially halt the progression of chronic CD symptoms. This can substantially reduce healthcare costs involved in managing heart failure and other potential outcomes of chronic CD. A further and more fundamental goal is extending the lives of patients.

Supplementary Material

Notes

Acknowledgments. We are deeply grateful to the patients who participated in the study. We also thank the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for help with testing patients, for providing medication, and for guiding us on how to measure adverse events. Finally, we thank the Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative and Doctors Without Borders (MSF) USA for their support.

Financial support. While working on this article, C. J. F.'s position was funded jointly by the Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative and Doctors Without Borders/MSF USA.

Potential conflicts of interest. M. I. T. reports a consultancy relationship with Merck for separate research on Chagas disease within 36 months of being involved in this study. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Chagas disease in Latin America: an epidemiological update based on 2010 estimates. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmunis GA, Yadon ZE. Chagas disease: a Latin American health problem becoming a world health problem. Acta Trop 2010; 115:14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bern C, Montgomery SP. An estimate of the burden of Chagas disease in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49:e52–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manne-Goehler J, Reich MR, Wirtz VJ. Access to care for Chagas disease in the United States: a health systems analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2015; 93:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee BY, Bacon KM, Bottazzi ME, Hotez PJ. Global economic burden of Chagas disease: a computational simulation model. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13:342–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rassi AJ, Rassi A, Marin-Neto JA. Chagas disease. Lancet 2010; 375:14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ribeiro AL, Nunes MP, Teixeira MM, Rocha MO. Diagnosis and management of Chagas disease and cardiomyopathy. Nat Rev Cardiol 2012; 9:576–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bern C. Antitrypanosomal therapy for Chagas’ disease. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coura JR, de Castro SL. A critical review on Chagas disease chemotherapy. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2002; 97:21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cançado JR. Long-term evaluation of etiological treatment of Chagas disease with benznidazole. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2002; 44:8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Viotti R, Alarcon de Noya B, Araujo-Jorge T et al. . Towards a paradigm shift in the treatment of chronic Chagas disease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58:635–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Viotti R, Vigliano C, Bertocchi G et al. . Long-term outcomes of treating chronic Chagas disease with benznidazole versus no treatment. Ann Intern Med 2006; 144:10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fabbro DL, Streiger Ml, Arias ED, Bizai ML, del Barco M, Amicone NA. Trypanocide treatment among adults with chronic Chagas disease living in Santa Fe City (Argentina), over a mean follow-up of 21 years: parasitological, serological, and clinical evolution. Revista de Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical 2007; 40:10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morillo CA, Marin-Neto JA, Avezum A et al. . Randomized trial of benznidazole for chronic Chagas’ cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:1295–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson Y, Alirol E, Getaz L, Wolff H, Combescure C, Chappuis F. Tolerance and safety of nifurtimox in patients with chronic Chagas disease. Clin Infect Dis 2010; 51:e69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bern C, Montgomery SP, Herwaldt BL et al. . Evaluation and treatment of Chagas disease in the United States: a systematic review. JAMA 2007; 298:10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Viotti R, Vigliano C, Lococo B, Alvarez MG, Bertocchi G, Armenti A. Side effects of benznidazole as treatment in chronic Chagas disease: fears and realities. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2009; 7:7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller DA, Hernandez S, Rodriguez De Armas L et al. . Tolerance of benznidazole in a United States Chagas disease clinic. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60:1237–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coming together on Chagas disease. NewsBites: Spotlight on CDC's Parasitic Disease Work Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valencia CN, Mancilla M, Ramos D et al. . Tratamiento de la enfermedad de Chagas crónica en Chile. Efectos adversos de nifurtimox [in Spanish]. Rev Ibero-Laintoam Parasitol 2012; 71:11. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olivera MJ, Cucunuba ZM, Alvarez CA, Nicholls RS. Safety profile of nifurtimox and treatment interruption for chronic Chagas disease in Colombian adults. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2015; 93:1224–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perez-Molina JA, Sojo-Dorado J, Norman F et al. . Nifurtimox therapy for Chagas disease does not cause hypersensitivity reactions in patients with such previous adverse reactions during benznidazole treatment. Acta Trop 2013; 127:101–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manne J, Snively CS, Levy MZ, Reich MR. Supply chain problems for Chagas disease treatment. Lancet Infect Dis 2012; 12:173–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pew Research Center. Hispanic population in select US metropolitan areas, 2011. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stimpert KK, Montgomery SP. Physician awareness of Chagas disease, USA. Emerg Infect Dis 2010; 16:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.03. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010.

- 27.Castro JA, Montalto de Mecca M, Bartel LC. Toxic side effects of drugs used to treat Chagas’ disease (American trypanosomiasis). Hum Exp Toxicol 2006; 25:8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teixeira AR, Silva R, Cunha Neto E, Santana JM, Rizzo LV. Malignant, non-Hodgkin's lymphomas in Trypanosoma cruzi-infected rabbits treated with nitroarenes. J Comp Pathol 1990; 103:11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bianchi F, Cucunubia Z, Guhl F et al. . Follow-up of an asymptomatic Chagas disease population of children after treatment with nifurtimox (Lampit) in a sylvatic endemic transmission area of Colombia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015; 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bermudez J, Davies C, Simonazzi A, Pablo Real J, Palma S. Current drug therapy and pharmaceutical challenges for Chagas disease. Acta Trop 2016; 156:1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Molina I, Salvador F, Sanchez-Montalva A et al. . Toxic profile of benznidazole in patients with chronic Chagas disease: risk factors and comparison of the product from two different manufacturers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59:6125–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bayer AG. Chagas disease. Available at: http://pharma.bayer.com/en/commitment-responsibility/neglected-diseases/chagas-disease/ Accessed 13 May 2016.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.