Abstract

Efferocytosis has been suggested to promote macrophage resolution programs that are dependent on motility and emigration, however, few studies have addressed directed migration in resolving macrophages. In this report, we hypothesized that efferocytosis would induce differential chemokine receptor expression. Polarized macrophage populations, including macrophages actively engaged in efferocytosis, were characterized by PCR array and traditional transwell motility assays. We identified specific up-regulation of chemokine receptor CXCR4 on both mouse and human macrophages and characterized in vivo expression of CXCR4 in a resolving model of murine peritonitis. Using adoptive transfer and AMD3100 blocking, we confirmed a role for CXCR4 in macrophage egress to draining lymphatics. Collectively these data provide an important mechanistic link between efferocytosis and macrophage emigration.

Keywords: Efferocytosis, Macrophage Activation, Resolution of Inflammation, Chemotaxis, Peritonitis

Introduction

Chemokine and chemokine receptor interactions have long been appreciated for orchestrating leukocyte trafficking in innate and adaptive immunity. Chemokine receptor expression can specifically correlate to activation state and differential expression is perhaps best described in polarized T-cell populations [1–3]. The accumulation of monocyte derived macrophages within inflammatory foci is often a defining feature of chronic inflammation and an extensive amount of research has been performed to characterize monocyte chemokine receptor expression and monocyte trafficking [4–7]. In contrast, little is known regarding chemokine receptor expression in mature differentiated macrophages and few studies have attempted to characterize directed migration as it relates to macrophage resolution.

Macrophages are highly plastic and can change their polarization and functional state in response to a variety of environmental stimuli [8, 9]. Recent studies have emphasized the significance of heterogeneous macrophages to drive either the propagation or resolution of inflammation. Two mechanisms have been proposed to explain macrophage clearance: local cell death and emigration to draining lymphatics [10, 11]. The latter mechanism, which suggests motility-dependent resolution, provides significant motivation to characterize directed migration in resolving macrophages. Nonphlogistic clearance of apoptotic cells, or efferocytosis, is recognized as a key signaling event in resolution that mediates a switch toward anti-inflammatory or deactivated polarization [12–14]. In this report, we examine chemokine receptor expression in macrophages actively engaged in efferocytosis. We identify differential expression of chemokine receptor CXCR4 on mouse and human macrophages and demonstrate functional participation in the resolution of murine peritonitis.

Results and discussion

Chemokine receptor expression on polarized macrophages

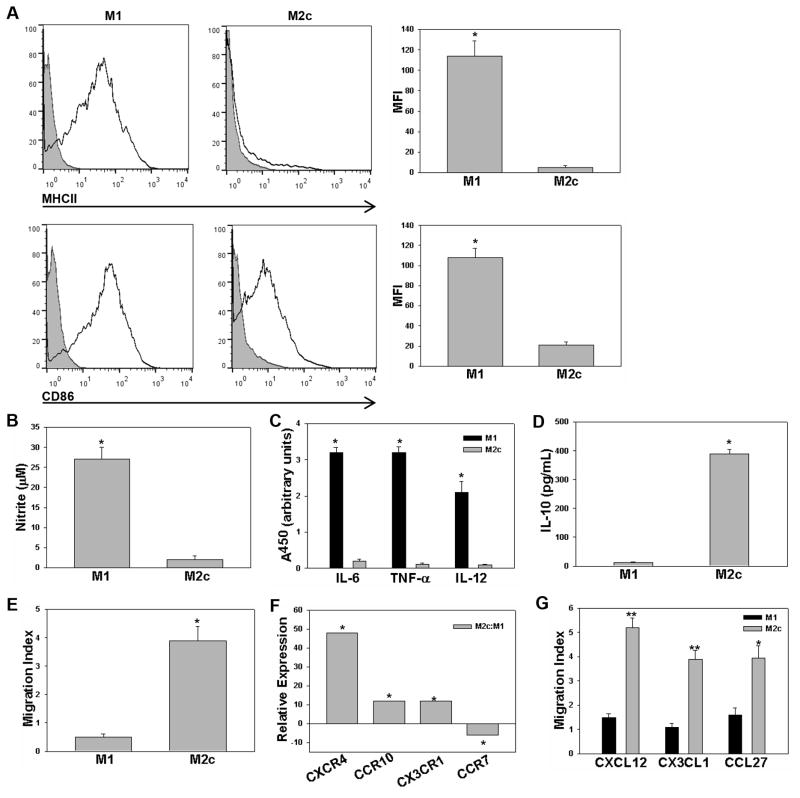

Macrophages display significant phenotypic heterogeneity, an attribute consistent with their role in seemingly opposing physiological processes, including, inflammation, repair, and resolution. Activation can be generically divided into two categories: classically activated and pro-inflammatory M1 and alternatively activated M2. M2 activation represents a broad spectrum that includes M2a (IL-4 or IL-13 activation), M2b (immune complex and Toll-like receptor activation), and M2c (IL-10 or adenosine activation) [15, 16]. Although such categories provide a framework to examine macrophage phenotype, they are limited in their ability to reflect the continuum of polarization that occurs in vivo. Moreover, within the scientific literature, there exists a lack of consensus in nomenclature that has spurred recent efforts at standardization [17, 18]. Given limited studies characterizing directed migration in resolving macrophages, we initiated this study with particular interest in the chemokine receptor expression of M2c macrophages which are immunosuppressive (IL-10+) and deactivated (MHCII−), consistent with a resolution phenotype. We chose to investigate adenosine treated M2c macrophages, as we and others have previously characterized high intrinsic motility with adenosine treatment [19, 20]. Thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal macrophages were utilized to generate M1 or M2c macrophages and polarization was confirmed by cell surface marker expression, biochemical signature, and motility. M1 macrophages displayed characteristically high expression of MHCII and CD86 and inflammatory mediators, including iNOS, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-12, correlative expression in M2c macrophages was significantly reduced (Fig. 1A–C and Supporting Information Fig. 1). M2c macrophages were characterized by IL-10 production and higher intrinsic motility (Fig. 1D–E and Supporting Information Fig. 2). After establishing defined M1 and M2c populations, we next investigated the chemokine receptor gene expression profile using PCR array. Analysis of chemokine receptor expression, normalized to GAPDH, revealed significantly increased expression of three chemotaxis receptors in M2c macrophages: CXCR4, CX3CR1, and CCR10 and significantly decreased expression in one receptor, CCR7 (Fig. 1F). A traditional Boyden chamber assay was used to confirm CXCR4-, CX3CR1-, and CCR10-dependent chemotaxis of M2c polarized macrophages toward their appropriate chemokine ligands: CXCL12, CX3CL1, and CCL27, respectively (Fig. 1G and Supporting Information Fig. 3). These results confirm differential chemokine receptor expression in M2c vs. M1 macrophages and suggest a functional role for CXCR4, CX3CR1, and CCR10 in M2c macrophages.

Figure 1.

Chemokine receptor expression on polarized macrophages from C57BL6 mice. (A) Murine thioglycollate-elicited M1 (IFN-γ/LPS) and M2c (adenosine) populations from C57BL6 mice were examined for surface expression of MHCII and CD86. Data is displayed in histogram format against the IgG control (grey) and presented as mean fluorescent intensity (MFI). (B) M1-induced iNOS activity was characterized by the Griess reaction. (C) Cytokine profile measured with ELISArray and results are reported as arbitrary units of absorbance according to manufacturer protocol. (D) IL-10 was measured in conditioned media using ELISA. (E) Boyden chamber migration to DMEM + 10% serum was characterized for M1 and M2c macrophages. (F) Chemokine receptor expression was screened using mouse chemokines and receptors RT2 PCR array. GAPDH normalized expression levels of M2c are expressed as fold difference relative to GAPDH normalized M1 macrophages according to manufacturer protocol. Genes that displayed at least a five-fold difference in expression with p < 0.05 are reported. (G) Polarization-dependent chemotaxis was examined against CXCL12, CX3CL1, and CCL27. Results are reported as migration index relative to motility without the addition of a chemoattractant in the lower well. Data shown are mean ± SEM from n = 3–5 independent experiments, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 (Student’s t-test).

Efferocytosis regulates chemokine receptor expression

Efferocytosis, or the nonphlogistic clearance of apoptotic cells, is often characterized as the physiologic switch to deactivate macrophage inflammatory responses and drive resolution. Many studies have characterized engulfment-dependent release of soluble anti-inflammatory mediators, including IL-10, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), adenosine, and prostaglandin E2 [21–23]. Although we observed differential chemokine receptor expression with adenosine, we postulated that efferocytosis would represent the most relevant switching signal, thus, we elected to investigate the impact of efferocytosis on chemokine receptor expression in macrophages (M2EFF). Apoptotic macrophages were generated by exposure to UV light and annexin v/propidium iodide (PI) was used to confirm an enriched population of apoptotic cells with limited necrotic events (Fig. 2A). Apoptotic cells were incubated with macrophages (15:1) for 2 h and then removed with subsequent wash steps. We confirmed the anti-inflammatory nature of our engulfment protocol by monitoring the production of TGF-β and the suppression of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) (Fig. 2B–C). Chemokine receptor expression was examined in M2EFF and M1 populations. Remarkably, we observed a similar pattern of chemokine receptor expression to that of adenosine treated M2c macrophages, with upregulation of CXCR4, CCR10, CX3CR1 and downregulation of CCR7 (Fig. 2D). Transwell migration was used to confirm chemotaxis in M2EFF macrophages. We observed significant migration toward the CXCR4 chemokine CXCL12, however, polarization-dependent migration was not observed toward CX3CL1 or CCL27 (Fig. 2E). With CXCR4 identified as a target of interest on both M2c and M2EFF, subsequent studies directed focus towards characterizing the expression of this receptor. Flow cytometry confirmed CXCR4 expression on both murine M2EFF (Fig. 2F) and, significantly, human M2EFF (Fig. 2G). No CXCR4 expression was observed on murine and human M1 polarized macrophages (Supporting Information Fig. 4). Collectively, these data confirm CXCR4 expression in both mouse and human M2EFF populations suggesting that CXCR4 may hold functional significance in macrophage resolution.

Figure 2.

Efferocytosis regulates chemokine receptor expression. (A) Apoptotic RAW macrophages were generated by exposure to UV and limited necrosis was confirmed with annexin v+ (apoptotic) and prodidium iodide− (necrotic) staining. (B) TGF-β was measured by ELISA in the conditioned media of macrophages actively engaged in efferocytosis (M2EFF) as compared to control. (C) Efferocytosis suppresses M1 TNF-α expression. Macrophages polarized to M1 with or without subsequent exposure to apoptotic macrophages were subjected to qPCR, results are reported as fold difference in TNF-α expression levels. (D) Chemokine receptor expression was screened using mouse chemokines and receptors by RT2 PCR array. GAPDH normalized expression levels of M2EFF are expressed as fold difference relative to GAPDH normalized M1 macrophages according to manufacturer protocol. Genes that displayed at least a five-fold difference in expression with p < 0.05 are reported. (E) M1- and M2EFF- dependent chemotaxis was examined against CXCL12, CX3CL1, and CCL27. Results are reported as migration index relative to motility without addition of a chemoattractant in the lower well. (F–G) Mouse M2EFF (F) or human M2EFF (G) were examined for CXCR4 expression by flow cytometery. Data is displayed in histogram format against the IgG control (grey) and presented as mean fluorescent intensity (MFI). Data shown are mean ± SEM from n = 3–5 independent experiments, *p < 0.05 (Student’s t-test).

CXCR4 expression in murine peritonitis

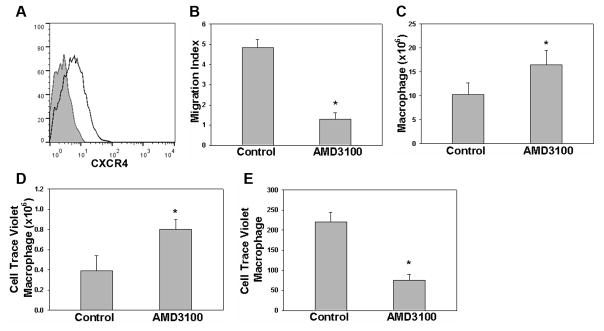

Given the association between efferocytosis and macrophage CXCR4 expression, we chose to investigate CXCR4-dependent responses in a murine model of peritonitis. Macrophages were collected at 18 h post-thioglycollate induction and examined for CXCR4 expression using flow cytometry. We observed up-regulated expression of macrophage CXCR4 protein (Fig. 3A) compared to resident control macrophages where no detectable CXCR4 was observed (data not shown). To determine if CXCR4 is actively involved in macrophage migration during peritonitis, CXCR4 blockade was analyzed using AMD3100, an antagonist to CXCR4. While AMD3100 inhibitory effects on CXCR4-mediated chemotaxis of hematopoietic stem cells and tumor cells has been well documented [24, 25], the blocking effect of AMD3100 on CXCR4-mediated macrophage chemotaxis has not been previously characterized. Thus, the ability of AMD3100 to inhibit macrophage migration toward CXCL12 was initially analyzed using a transwell migration assay, where it was found to effectively limit macrophage chemotaxis toward CXCL12 (Fig. 3B). To examine the significance of CXCR4 on macrophage migration in vivo, AMD3100 or PBS was administered to mice intraperitoneally 18 h after thioglycollate injection. Flow cytometry of peritoneal exudates obtained 6 h post-AMD3100 injection revealed that the macrophage count was increased as compared to those mice receiving PBS (Fig. 3C and Supporting Information Fig. 5). This result suggests that CXCR4 regulates macrophage peritoneal migration and inhibition leads to macrophage retention at sites of inflammation. To determine if CXCR4 plays a role in macrophage emigration to draining lymph nodes, we utilized an adoptive transfer model in which Cell Trace Violet fluorescently labeled macrophages were injected into the peritoneal cavity of mice in the same stage of peritonitis with or without prior in vitro treatment with AMD3100 [10]. Ten hours after adoptive transfer, the peritoneal cavity was lavaged. A greater quantity of labeled macrophages was observed in the AMD3100 treatment group (Fig. 3D). Mesenteric lymph nodes were harvested from both control and the AMD3100 treatment group and flow cytometry used to quantify fluorescently labeled macrophages. Significantly, the number of labeled macrophages recovered from mesenteric lymph nodes was lower in the AMD3100 treatment group consistent with a role for CXCR4 in macrophage emigration (Fig. 3E).

Figure 3.

CXCR4 expression in murine peritonitis. (A) Peritoneal macrophage CXCR4 expression was examined by flow cytometery 18 h after thioglycollate induction. Data is displayed in histogram format against the IgG control (grey) (n=3). (B) AMD3100 inhibition of macrophage CXCR4-CXCL12 chemotaxis was characterized using a Boyden chamber assay. Migration index to CXCL12 is reported with or without inhibitor (Control vs. AMD3100, n=5). (C) AMD3100 or vehicle control were delivered IP 18 h after thioglycollate injection and 6 hours later peritoneal macrophages were lavaged and counted (n=6). (D–E) Cell Trace Violet labeled macrophages were adoptively transferred 18 h after thioglycollate injection and 10 h later, violet+ peritoneal cells were lavaged and counted (D) and mesenteric lymph nodes (E) were harvested for enumeration of violet+ macrophages (n= 10). Data shown are mean ± SEM and represent independent experiments, *p < 0.05 (Student’s t-test).

Concluding remarks

Macrophage accumulation is a defining feature of chronic inflammatory disease. While many efforts have focused on understanding monocyte recruitment into sites of inflammation, recent findings have suggested that both efferocytosis and macrophage egress can have a profound effect on inflammation outcome. In the context of acute peritonitis, efferocytosis programs are likely driven through clearance of apoptotic neutrophil and macrophage populations. A 1996 study from Bellingan et al utilized murine thioglycollate-initiated peritonitis to describe inflammatory macrophage resolution via emigration to efferent lymph however this study also suggested that local apoptosis is limited to the neutrophil population [10]. Subsequent studies employing murine zymosan-induced peritonitis have reported a role for both neutrophil and macrophage apoptosis/engulfment [26] and macrophage emigration [13] and a recent report from Gautier et al confirms that both neutrophil and macrophage apoptosis and macrophage emigration are also active in murine thioglycollate peritonitis [11]. Despite recent focus on macrophage resolution programs, the link between efferocytosis and macrophage migration is not well understood. In this study, our investigations have identified enhanced expression of CXCR4 on adenosine-induced M2c macrophages. Moreover, we provide evidence that macrophage CXCR4 expression can be triggered by efferocytosis and that CXCR4 is involved in macrophage egress to draining lymph nodes. CXCR4-CXCL12 signaling is known to participate in dendritic cell migration to secondary lymphoid organs, which would suggest a similar role in macrophage emigration [27]. In contrast, CCR7, which is often suggested to participate in macrophage lymphatic emigration [28, 29], was strongly associated with the more sessile M1 inflammatory macrophages. To our knowledge, this is the first report detailing chemokine receptor expression in M2EFF and the first characterization of CXCR4 in macrophage clearance.

Materials and methods

Peritonitis

Murine peritonitis was induced on C57BL6 mice by intraperitoneal (IP) injection of 0.5 mL of 6% sterile thioglycollate (TG) broth. All experimental procedures were performed according to a protocol approved by Emory University and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Macrophage culture and biochemical assays

All endpoints were collected using murine thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal macrophages or human monocyte derived macrophages. Murine macrophages were cultured in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). M1 activation was induced by culturing macrophages overnight in the presence of IFN-γ (100 U/mL) and LPS (100 ng/mL). M2c activation was induced by culturing macrophage overnight with adenosine (375 μM). M2a activation was induced overnight in the presence of IL-4 (20 ng/mL). Human monocyte derived macrophages were generated according to standard protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Briefly, peripheral blood mononuclear cells were prepared from the buffy coat of whole citrated venous blood and plated in complete RPMI 1640 culture medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 100U/mL penicillin/streptomycin. Nonadherent cells were removed at 12 h and remaining cells were cultured for 7 days in the presence of 50 ng/mL M-CSF to support macrophage differentiation. Polarization was performed as described above. Generation of nitrites was measured using the Griess reagent kit (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer protocol. Arginase activity was monitored in 4×105 cells lysed with 0.1% Triton X-100, MnCl2 was added to lysates at a final concentration of 1 mM. Agrinase was activated by heating the mixture to 55°C for 10 min with 50 mM L-arginine. Mixtures were then incubated at 37°C for 60 min and reactions stopped with the addition of H2SO4/H3PO4. Absorbance was measured at 540 nm after addition of α-isonitrosopropiophenone at 100°C for 30 min. Chemokine profile was obtained from the conditioned media of M1 or M2c macrophages. Serum free DMEM was added after initial M1 or M2c stimulation and conditioned medium collected after 12 h and analyzed for interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-12 using the Mouse Inflammatory Cytokine ELISArray (SA Biosciences). IL-10 and TGF-β were measured using a standard ELISA kit (R&D Systems). Trypan blue exclusion was used routinely to ensure equivalent viability in all in vitro endpoints.

PCR array

mRNA expression analysis was performed using mouse chemokines and receptors RT2 profiler PCR array (SABiosciences). RNA was extracted from M1, M2c, or M2EFF with TRIzol reagent and purified using RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer protocol. A total of 1 μg of RNA from each sample was converted to cDNA using the RT2 first strand kits (SABiosciences) and then subjected to PCR array analysis on the Applied Biosystems 7900 using RT2 qPCR Master Mix, according to manufacturer’s protocol (SABiosciences). mRNA expression level for each gene was normalized to the expression level of glyceraldehydes-3-phosphage dehydrogenase (GAPDH) using the equation 2-(Ct[gene of interest]-Ct[GAPDH], where Ct is the threshold cycle. Normalized gene expression levels of experimental samples (M2c or M2EFF macrophages) were obtained by comparing the gene expression level to control (M1) using software provided by SABiosciences. For array data, genes that displayed at least a five-fold difference in expression with p < 0.05 are reported.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed on a Becton Dickinson LSRII four laser benchtop analyzer equipped with a solid state 488 nm laser, a JDSU uniphase 633 nm helium-neon laser, a Lightwave mode lock 355 nm UV laser, and a Coherent Vioflame 404 nm violet laser. The antibodies used for cell staining included anti-F4/80 (BM8), anti-I-A/I-E (M5/114.15.2), anti-CD86 (GL1), and anti-CD184/CXCR4 (2B11 and 12G5). Negative controls with isotype IgG were included for each marker.

Efferocytosis experiments

Apoptotic cells were generated by exposure of plated macrophages to ultraviolet (UV) light. Macrophages were plated at 10×106 cells per 100×20 mm tissue culture dish and were then placed 5 inches from the UV (254 nm) source and exposed for 5 min with the culture dish lid off in a cell culture hood. Irradiated macrophages were then cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 humidified incubator for 2 h. Early apoptotic events were confirmed with annexin v/PI staining using flow cytometry. To investigate macrophage CXCR4 expression following efferocytosis, apoptotic RAW 264.7 cells were added to peritoneal macrophages (15:1 ratio) and cultured in DMEM with 0.5% FBS for 2 h. Excess apoptotic cells were removed with PBS washing followed by overnight incubation. To investigate human CXCR4 expression following efferocytosis, a similar protocol was followed with apoptotic human THP1 cells added to human monocyte derived macrophages (15:1 ratio) and culture performed in RPMI with 0.5% FBS.

Macrophage chemotaxis

Chemotaxis was analyzed by loading 100 μL (1×106/mL) of peritoneal macrophages in DMEM with 0.5% FBS into the upper well of 24-well 8 μm transwell permeable supports (Corning). DMEM containing 0.5% FBS was added into the lower well. Prior to initiation of chemotaxis, adherent cells were incubated with M1, M2c, or apoptotic cells. After 4 h, the media and stimulus was removed and fresh DMEM containing 0.5% FBS added into both chambers. The chemokines CXCL12 (200 ng/mL), CX3CL1 (400 ng/mL), CCL27 (250 ng/mL), or CCL2 (100 ng/mL) were added into the lower chambers of the experimental group, without addition of chemokines in control groups. Intrinsic motility was characterized as migration to DMEM with 10% FBS. After 18 h, macrophages that migrated onto the lower well surface of the membrane were fixed with 10% formalin in PBS for 10 min and the top surface of the membrane scrapped prior to analysis. For each replicate, three separate wells containing peritoneal macrophages obtained from separate mice were included. The numbers of macrophages in three independent fields of view were counted in each well and averaged. Migration was quantified as migration index by dividing the number of macrophages in experimental groups compared to respective control groups.

CXCR4 blocking

AMD3100 blocking was confirmed in vitro by the addition of 25 μg/mL to CXCL12 chemotaxis experiments described above. In vivo, ADM3100 or vehicle control was delivered IP (200 μL of a 625 μg/mL solution in PBS) 18 h after TG injection. Mice were lavaged 6 h later and the macrophage count confirmed by F4/80 staining using flow cytometry.

Adoptive transfer

Peritonitis was induced in both donor and recipient mice. Macrophages were obtained by lavage 18 h after the induction of peritonitis and labeled with 3 μM CellTace Violet (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer instruction. Labeled macrophages were counted and re-suspended in sterile PBS. AMD3100 (25 μg/mL) or vehicle control was added to the cells and incubated at 4°C in the dark for 30 min. Cell suspensions were then injected into the peritoneal cavity of recipient mice at the same stage of peritonitis (18 h post-TG). Recipient mice also received AMD3100 (200 μL of a 625 μg/mL solution in PBS, IP) or vehicle control. Recipient mice were sacrificed 10 h post-adoptive transfer, lavaged, and the mesenteric lymph nodes were harvested and processed for flow cytometry.

Statistical Analysis

Mean and SEM were calculated for each parameter. All data were analyzed via two-tailed Student’s t-test. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NIH grant HL060903 (E.L. Chaikof) and a fellowship from the American Heart Association (J. Angsana).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Griffith JW, Sokol CL, Luster AD. Chemokines and chemokine receptors: positioning cells for host defense and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:659–702. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krummel MF, Macara I. Maintenance and modulation of T cell polarity. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1143–1149. doi: 10.1038/ni1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viola A, Contento RL, Molon B. T cells and their partners: The chemokine dating agency. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:421–427. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strauss-Ayali D, Conrad SM, Mosser DM. Monocyte subpopulations and their differentiation patterns during infection. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:244–252. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0307191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tacke F, Alvarez D, Kaplan TJ, Jakubzick C, Spanbroek R, Llodra J, Garin A, Liu J, Mack M, van Rooijen N, Lira SA, Habenicht AJ, Randolph GJ. Monocyte subsets differentially employ CCR2, CCR5, and CX3CR1 to accumulate within atherosclerotic plaques. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:185–194. doi: 10.1172/JCI28549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas G, Tacke R, Hedrick CC, Hanna RN. Nonclassical patrolling monocyte function in the vasculature. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:1306–1316. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ziegler-Heitbrock L, Ancuta P, Crowe S, Dalod M, Grau V, Hart DN, Leenen PJ, Liu YJ, MacPherson G, Randolph GJ, Scherberich J, Schmitz J, Shortman K, Sozzani S, Strobl H, Zembala M, Austyn JM, Lutz MB. Nomenclature of monocytes and dendritic cells in blood. Blood. 2010;116:e74–80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-258558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinez FO, Sica A, Mantovani A, Locati M. Macrophage activation and polarization. Front Biosci. 2008;13:453–461. doi: 10.2741/2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sica A, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and polarization: in vivo veritas. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:787–795. doi: 10.1172/JCI59643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bellingan GJ, Caldwell H, Howie SE, Dransfield I, Haslett C. In vivo fate of the inflammatory macrophage during the resolution of inflammation: inflammatory macrophages do not die locally, but emigrate to the draining lymph nodes. J Immunol. 1996;157:2577–2585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gautier EL, Ivanov S, Lesnik P, Randolph GJ. Local apoptosis mediates clearance of macrophages from resolving inflammation in mice. Blood. 2013;122:2714–2722. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-478206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ariel A, Serhan CN. New Lives Given by Cell Death: Macrophage Differentiation Following Their Encounter with Apoptotic Leukocytes during the Resolution of Inflammation. Front Immunol. 2012;3:4. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schif-Zuck S, Gross N, Assi S, Rostoker R, Serhan CN, Ariel A. Saturated-efferocytosis generates pro-resolving CD11b low macrophages: modulation by resolvins and glucocorticoids. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:366–379. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Voll RE, Herrmann M, Roth EA, Stach C, Kalden JR, Girkontaite I. Immunosuppressive effects of apoptotic cells. Nature. 1997;390:350–351. doi: 10.1038/37022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Vecchi A, Locati M. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:677–686. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valledor AF, Comalada M, Santamaria-Babi LF, Lloberas J, Celada A. Macrophage proinflammatory activation and deactivation: a question of balance. Adv Immunol. 2010;108:1–20. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-380995-7.00001-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray PJ, Allen JE, Biswas SK, Fisher EA, Gilroy DW, Goerdt S, Gordon S, Hamilton JA, Ivashkiv LB, Lawrence T, Locati M, Mantovani A, Martinez FO, Mege JL, Mosser DM, Natoli G, Saeij JP, Schultze JL, Shirey KA, Sica A, Suttles J, Udalova I, van Ginderachter JA, Vogel SN, Wynn TA. Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity. 2014;41:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinez FO, Gordon S. The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activaiton: time for reassessment. F1000Prime Rep. 2014 doi: 10.12703/P6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Angsana J, Chen J, Smith S, Xiao J, Wen J, Liu L, Haller CA, Chaikof EL. Syndecan-1 modulates the motility and resolution responses of macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:332–340. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim C, Wilcox-Adelman S, Sano Y, Tang WJ, Collier RJ, Park JM. Antiinflammatory cAMP signaling and cell migration genes co-opted by the anthrax bacillus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:6150–6155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800105105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fadok VA, Bratton DL, Konowal A, Freed PW, Westcott JY, Henson PM. Macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells in vitro inhibit proinflammatory cytokine production through autocrine/paracrine mechanisms involving TGF-beta, PGE2, and PAF. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:890–898. doi: 10.1172/JCI1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koroskenyi K, Duro E, Pallai A, Sarang Z, Kloor D, Ucker DS, Beceiro S, Castrillo A, Chawla A, Ledent CA, Fesus L, Szondy Z. Involvement of adenosine A2A receptors in engulfment-dependent apoptotic cell suppression of inflammation. J Immunol. 2011;186:7144–7155. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freire-de-Lima CG, Xiao YQ, Gardai SJ, Bratton DL, Schiemann WP, Henson PM. Apoptotic cells, through transforming growth factor-beta, coordinately induce anti-inflammatory and suppress pro-inflammatory eicosanoid and NO synthesis in murine macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:38376–38384. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605146200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kessans MR, Gatesman ML, Kockler DR. Plerixafor: a peripheral blood stem cell mobilizer. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30:485–492. doi: 10.1592/phco.30.5.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uy GL, Rettig MP, Cashen AF. Plerixafor, a CXCR4 antagonist for the mobilization of hematopoietic stem cells. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2008;8:1797–1804. doi: 10.1517/14712598.8.11.1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kolaczkowska E, Koziol A, Plytycz B, Arnold B. Inflammatory macrophages, and not only neutrophils, die by apoptosis during acute peritonitis. Immunobiology. 2010;215:492–504. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ricart BG, John B, Lee D, Hunter CA, Hammer DA. Dendritic cells distinguish individual chemokine signals through CCR7 and CXCR4. J Immunol. 2011;186:53–61. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Gils JM, Derby MC, Fernandes LR, Ramkhelawon B, Ray TD, Rayner KJ, Parathath S, Distel E, Feig JL, Alvarez-Leite JI, Rayner AJ, McDonald TO, O’Brien KD, Stuart LM, Fisher EA, Lacy-Hulbert A, Moore KJ. The neuroimmune guidance cue netrin-1 promotes atherosclerosis by inhibiting the emigration of macrophages from plaques. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:136–143. doi: 10.1038/ni.2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trogan E, Feig JE, Dogan S, Rothblat GH, Angeli V, Tacke F, Randolph GJ, Fisher EA. Gene expression changes in foam cells and the role of chemokine receptor CCR7 during atherosclerosis regression in ApoE-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3781–3786. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511043103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.