Abstract

3-mercaptopropionate dioxygenase from Azotobacter vinelandii (Av MDO) is a non-heme mononuclear iron enzyme that catalyzes the O2-dependent oxidation of 3-mercaptopropionate (3mpa) to produce 3-sulfinopropionic acid (3spa). With one exception, the active site residues of MDO are identical to bacterial cysteine dioxygenase (CDO). Specifically, the CDO Arg-residue (R50) is replaced by Gln (Q67) in MDO. Despite this minor active site perturbation, substrate-specificity of Av MDO is more relaxed as compared to CDO. In order to investigate the relative timing of chemical and non-chemical events in Av MDO catalysis, the pH/D-dependence of steady-state kinetic parameters (kcat and kcat/KM) and viscosity effects are measured using two different substrates [3mpa and L-cysteine (cys)]. The pL-dependent activity of Av MDO in these reactions can be rationalized assuming a diprotic enzyme model in which three ionic forms of the enzyme are present [cationic, E(z+1); neutral, Ez; and anionic, E(z−1)]. The activities observed for each substrate appear to be dominated by electrostatic interactions within the enzymatic active site. Given the similarity between MDO and the more extensively characterized mammalian CDO, a tentative model for the role of the conserved ‘catalytic triad’ is proposed.

Keywords: Non-heme mononuclear iron, Thiol dioxygenase, Solvent isotope effects, Proton inventory, Viscosity effects

1. Introduction

Thiol dioxygenase enzymes utilize a mononuclear non-heme iron site to catalyze the O2-dependent oxidation of thiol bearing substrates without the need for an external reductant or cofactor. Among this class of enzymes, the mammalian cysteine dioxygenase (CDO) is the best characterized [1–5]. Imbalances in L-cysteine (cys) metabolism have also been identified in a variety of neurological disease states (motor neuron, Parkinson and Alzheimer) [5–7]. These observations suggest a potential correlation between impaired sulfur metabolism, oxidative stress and neurodegenerative disease [8,9]. For this reason, enzymes involved in sulfur-oxidation and transfer are increasingly being recognized as potential drug targets for development of antimicrobials, therapies for cancer and inflammatory disease [10–13].

Multiple high-resolution crystal structures have been solved highlighting the conserved Fe-coordination sphere among confirmed thiol dioxygenase enzymes. The typical non-heme mononuclear oxidase/oxygenase iron coordination sphere is comprised of two protein-derived neutral His residues and one monoanionic carboxylate ligand, provided by either an Asp or Glu residue. By contrast, the mononuclear iron site in all known thiol dioxygenase enzymes is coordinated by three protein derived histidine residues resulting in a neutral 3-His facial triad.

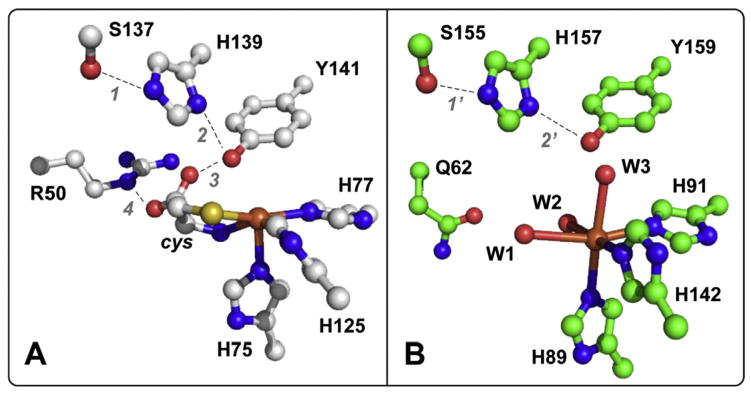

Structural comparison of annotated bacterial thiol dioxygenases suggest at least two subclasses of enzymes, which differ in a single outer Fe-coordination sphere residue (Arg or Asn) [14]. To illustrate, Fig. 1 shows the active site coordination for the ‘Arg-type’ bacterial cysteine dioxygenase (CDO) isolated form Bacillus subtilis (PDB code 4QM8) as compared to the ‘Gln-type’ enzyme cloned from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PDB code 4TLF) [15]. Of note, the 3-His facial triad motif in both enzymes is conserved; however, the outer-sphere Arg-residue (R50) involved in electrostatic stabilization of the cys substrate is replaced by Gln (Q62). The spatial orientations of all other conserved residues (S137, H139 and Y141) within the active site ‘catalytic triad’ remain invariant. The primary difference between the eukaryotic and bacterial ‘Arg-type’ CDO enzymes is a post-translational modification adjacent (3.3 Å) to the mononuclear Fe-site in which spatially adjacent Cys93 and Tyr157 residues are covalently cross linked to produce a C93-Y157 pair. This feature is unique to eukaryotic enzymes [16,17].

Fig. 1.

Crystal structure of the substrate-bound ‘Arg-type’ Bacillus subtilis active site (A, PDB code 4QM8) as compared to the annotated ‘Gln-type’ MDO isolated from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (B, PDB code 4TLF) [14,15]. Solvent waters are designated W1-W3. Selected distances A: 1 (2.59 Å); 2 (3.30 Å); 3 (2.14 Å); 4 (2.65 Å); B: 1′ (2.56 Å); 2′ (2.95 Å).

Previously, both ‘Arg-’ and ‘Gln-type’ enzymes were annotated as bacterial CDO enzymes [14]. However, recent spectroscopic and kinetic investigations performed independently demonstrated that the ‘Gln-type’ class of thiol dioxygenase enzymes are more accurately designated as a 3-mercaptopropionic acid dioxygenase (MDO) [15,18]. Remarkably, these ‘Gln-type’ enzymes have vastly relaxed substrate-specificity as compared to CDO [16]. Indeed, at saturating substrate concentration, MDO isolated from the soil bacteria Azotobacter vinelandii (Av MDO) demonstrated comparable activity (kcat) toward three different thiol-bearing substrates [3-mercaptopropionic acid (3mpa), L-cysteine (cys) and cysteamine (ca)] [18]. Despite similar maximal velocities, the ‘Gln-type’ Av MDO exhibits a catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) for 3mpa nearly two orders of magnitude greater than cys and ca. Thus, 3mpa appears to be the preferred substrate for this enzyme. Similar behavior was reported for the ‘Gln-type’ enzyme isolated from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Pa) [15].

While the mammalian ‘Arg-type’ CDO isolated from Mus musculus (Mm CDO) has been extensively characterized, no information is available regarding the relative timing of chemical and nonchemical steps in ‘Gln-type’ MDO catalyzed reactions. Comparing the kinetic mechanisms for various thiol dioxygenase enzymes is critical to identifying common mechanistic behavior among this class of enzymes. To this end, the influence of pH, solvent isotope and viscosity effects were evaluated for Av MDO steady-state kinetic parameters (kcat and kcat/KM) obtained using two different substrates (3mpa and cys). Proton-inventory experiments were performed to determine the number of exchangeable protons in flight during chemical and non-chemical steps. The relative timing of diffusional steps was investigated by measuring the influence of solvent viscosity on enzyme kinetics. Collectively, these results provide greater insight into the role of conserved outer Fe-coordination sphere residues and the nature of substrate coordination to the mononuclear iron active site.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Expression and purification of Av MDO

The isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) inducible T7 vector for Av MDO (designated pRP42), was a generous gift from Professor Tim Larson (Virginia Tech, Department of Biochemistry). Sequence verification of the plasmid was performed by Sequetech (Mountain View, CA, http://sequetech.com/). The pRP42 vector was transformed into chemically competent BL21(DE3) E. coli (Novagen Cat. no. 70236-4) by heat-shock [42 °C for 45 s] and grown overnight at 37 °C on a lysogeny broth (LB) [19] agar plate in the presence of 100 mg/L ampicillin (Amp). The following day, a single colony was selected for growth in liquid LB (Amp) media for training on antibiotic prior to inoculation of 10-L BF-110 fermentor (New Brunswick Scientific) at 37 °C. Cell growth was followed by optical density at 600 nm (OD600). Induction was initiated by addition of 1.0 g IPTG, 78 mg ferrous ammonium sulfate and 20 g casamino acids at an OD600 ~4. At the time of induction, the temperature of the bioreactor was decreased from 37 °C to 25 °C and agitationwas set to maintain an O2 concentration of 20% relative to air-saturated media. After 4 h, the cells were harvested and pelleted by centrifugation (Beckman-Coulter Avanti J-E, JA 10.5 rotor) at 18,600 × g for 15 min. The resulting cell paste was stored at −80 °C.

In a typical purification, ~20 g frozen cell paste was added to 150 mL extraction buffer (20 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, pH 8.0). Lysosyme, ribonuclease and deoxyribonuclease were added to the slurry for a final concentration of 10 μg/mL each and stirred slowly on ice for 30 min. The resulting suspension was pulse sonicated (Bronson Digital 250/450) for 15 s on/off at 60% amplitude for a total time of 15 min. The insoluble debriswas removed from the cell free extract by centrifugation at 48,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C. The supernatant was diluted 1:1 with extraction buffer and then loaded onto a DEAE sepharose fast flow anion exchange column [7 cm W × 20 cm L] (GE Life Sciences #17070901) pre-equilibrated with 20 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, pH 8.0. The column was washed with three column volumes of extraction buffer prior to elution in a linear NaCl gradient (50 mM–350 mM). Fractions (~10 mL) were collected overnight and pooled based on enzymatic activity as described elsewhere [18,20]. SDS PAGE was also used to verify the presence of the recombinant protein (~23 kDa) within each fraction. Broad range protein molecular weight markers utilized in SDS PAGE experiments were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI) Cat. No. V8491. The pooled fractions were concentrated to approximately 5–10 mL using an Amicon stir cell equipped with an YM-10 ultrafiltration membrane. Thrombin protease (Biopharma Laboratories) was added to cleave the C-terminal His-tag from Av MDO. In a typical reaction, ~0.3 molar equivalents of thrombin per Av MDO (based on UV–visible absorbance at 280 nm) was added to batches of purified protein for overnight cleavage at 4 °C in HEPES buffer. The remaining thrombin and free (His)6-tag was removed from Av MDO by size exclusion chromatography using a sephacryl S100 column. For all batches of Av MDO used in these experiments, spectrophotometric determination of ferrous and ferric iron content was measured using 2,4,6-tripyridyl-s-triazine (TPTZ) as described elsewhere [18,20]. For clarity, the concentrations reported in enzymatic assays reflect the concentration of ferrous iron within samples of Av MDO (FeII-MDO). Protein content was determined by Bio-Rad protein assay. NOTE: Although the expressed Av MDO has a C-terminal His-tag, as compared to the DEAE AX method described above, use of immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) results in substantially lower enzymatic activity and yields due to loss of iron and protein denaturation.

2.2. Enzyme assays

3-sulfinopropionic acid (3spa), cysteine sulfinic acid (csa) and hypotaurine (ht) were assayed using the HPLC method described previously [18,21,22]. Instrumental conditions: column, Phenomenex C18 (100 mm × 4.6 mm); mobile phase, 20 mM sodium acetate, 0.6% methanol, 1% (v/v) heptaflurobutyric acid, pH 2.0. Analytes were detected spectrophotometrically at 218 nm. Reactions (1 mL) were prepared in a buffered solution at the desired pH to obtain a final concentration from 0.1 to 10 mM 3mpa (0.1–60mMcys). Each reaction was initiated by addition of Av MDO (typically 0.5–1.0 μM) at 20 ± 2 °C. Sample aliquots (250 μL) were removed from the reaction vial at selected time points and quenched by addition of 10 μL 1 N HCl (final pH 2.0). Prior to HPLC analysis, each sample was spin-filtered through a 0.22 μm cellulose acetate membrane (Corning, Spin-X). Product concentration was determined by comparison to calibration curves as described elsewhere [16,18]. The rate of dioxygen consumption in activity assays was determined polarographically using a standard Clark electrode (Hansatech Instruments, Norfolk, England) in a jacketed 2.5 mL cell. Calibration of O2-electrode is described in detail elsewhere [22,23]. All reactions were initiated by addition of 1.0 μM Av MDO under identical buffer conditions as described for HPLC assays. Reaction temperatures were maintained at 20 ± 2 °C by circulating water bath (ThermoFlex 900, Thermo Scientific).

2.3. Synthesis of the dianionic 3-sulfinopropionic acid

The salt of 3-sulfinopropionic acid (3spa) was prepared by saponification of the commercially available methyl ester [sodium 1-methyl 3-sulfinopropanoate; Sigma Aldrich 7,78,168]. Briefly, sodium 1-methyl-3-sulfinopropanoate (100 mg, 0.57 mmol) was dissolved in 5 mL of deionized water. To this solution, LiOH (70 mg, 2.9 mmol) was added prior to overnight reflux under constant stirring on an oil bath (~110 °C). The solution was then cooled to ~4 °C, filtered and the filtrate was dried by rotary evaporation. The resulting solid was dissolved in 2 mL of cold ethanol and filtered again to remove inorganic salts. Evaporation of the ethanol filtrate gave the desired compound as a white solid (68 mg, 0.45 mmol, 79%). Both 1H and 13C {1H} NMR were measured to verify the identity and relative purity of the 3spa product. 1H NMR (500 MHz, D2O) δ 2.49 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 2.37 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H). 13C {1H} NMR (126 MHz, D2O) δ 181.2, 57.3, 30.1 ppm. Additional confirmation of 3spa standard was performed by mass spectrometry as described elsewhere [18] with instrumentation from the Shimadzu Center for Advanced Analytical Chemistry (The University of Texas Arlington).

2.4. Solvent kinetic isotope effects and proton inventory

For pH/D-profiles (collectively pL) and solvent isotope studies, the buffer components were prepared directly in D2O and adjusted by direct addition of NaOD. Each pD value was obtained from the pH-electrode reading using the relationship [pD = pH + 0.4]. The composition of reaction buffers for all pL-profile experiments consisted of 20 mM Good’s buffer and 50 mM NaCl. 2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid (MES) was used to buffer reactions over the pL range of 5.5–6.9, 2-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazin-1-yl] ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) was used to buffer reactions over the pH/D range of 7.0–8.4 and 2-(cyclohexylamino)-ethanesulfonic acid (CHES) was used to buffer reactions over the pL range of 8.5–10. For proton inventory experiments, the mole fraction of D2O (n) was calculated based on combining appropriate ratios of buffer prepared in D2O and H2O.

2.5. Viscosity studies

For solvent viscosity studies the steady-state kinetic parameters (kcat and kcat/KM) were determined for Av MDO catalysis using both oxygen electrode and HPLC at pH 8.0 (20 °C) as described above. Sucrose was used to increase the buffer viscosity within reaction mixtures. The viscosity (η) of buffers containing sucrose were measured using an Ostwald viscometer relative to 20 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, pH 8.2 (20 °C). The values obtained represent the average of triplicate measurements. In these experiments, addition of sucrose up to 35% (w/v) was used to increase the relative viscosity of the buffer (ηrel) up to ~3-times that of the control buffer.

2.6. Data analysis

Steady-state kinetic parameters were determined by fitting data to the Michaelis-Menten equation using the program SigmaPlot ver. 11.0 (Systat Software Inc., Chicago, IL). From this analysis, both the kinetic parameters (kcat and KM) and error associated with each value were obtained by non-linear regression. For reactions where kcat- or kcat/KM-pH data exhibits limiting nonzero plateaus at low (YL) and high (YH) pH, followed by transition region and subsequent decrease beyond YH, the results were fit to equation (1) [24]. Here, Y is defined by either kcat or kcat/KM, and the variables [H], K1 and K2 represent the hydrogen ion concentration and the two observable dissociation constants for ionizable groups involved in catalysis, respectively.

| (1) |

For results in which kcat- or kcat/KM-pH profiles decreased only at low pH, the data were fit to equation (2) [25–27]. This expression is scaled by a constant scalar quantity (C) which represents the maximum kinetic rate (kcat or kcat/KM). The error associated with each parameter (kcat, kcat/KM, pKa1 and pKa2) determined from fits to equations (1) and (2) is reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of pL-dependent steady-state kinetic parameters determined for MDO in reactions utilizing 3-mercaptopropionic acid and L-cysteine.

| Av MDO kinetic parameter | Substrate

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

3mpa

|

cys

|

|||

| H2O | D2O | H2O | D2O | |

| log(kcat)-pL | ||||

| maximum kcat (s−1) | 0.45 + 0.06 | 0.45 + 0.03 | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 0.26 ± 0.02 |

| pKa1 | 7.8 ± 0.2 | 7.9 ± 0.1 | 6.3 ± 0.1 | 7.1 ± 0.1 |

| pKa2 | 9.2 ± 0.1 | 9.3 ± 0.1 | – | – |

| SKIE | 1.01 ± 0.11 | 1.08 ± 0.10 | ||

| log(kcat/KM)-pL | ||||

| maximum kcat/KM (M−1 s−1) | 27,000 ± 3000 | 10,000 ± 1100 | 41.5 ± 0.7 | 40.8 ± 0.5 |

| pKa1 | 7.4 ± 0.2 | 7.8 ± 0.2 | 6.2 ± 0.1 | 7.2 ± 0.1 |

| pKa2 | 9.1 ± 0.1 | 9.2 ± 0.1 | – | – |

| SKIE | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 1.02 ± 0.09 | ||

| Proton inventory | ||||

| pL 6.0 | y = 1 | n/a | ||

| pL = 8.2 | y = 1 | n/a | ||

| (2) |

Proton inventory results were fit to equation (3) where n is the mol fraction of D2O in the reaction chamber and E0 and En are the kinetic parameters (either kcat or kcat/KM) in H2O and the mol fraction of D2O, respectively. The measured solvent kinetic isotope effect is defined as SKIE and the integer value y describes the number of protons that contribute to the isotope effect.

| (3) |

The effect of solvent viscosity on the steady-state parameters were fit using equation (4). In this equation, Y0 represents each kinetic parameter determined in the absence of viscogen whereas Yη is the value obtained at each specific relative viscosity measured. All viscosities measured are normalized to reaction buffer in the absence of viscogen (ηrel). The slope of the line (m) represents the extent of diffusion limitation.

| (4) |

3. Results

3.1. Solvent kinetic isotope effects

It has been previously observed that Av MDO catalyzes the O2-dependent oxidation of thiol-bearing substrates 3-mercaptopropionic acid (3mpa), L-cysteine (cys) and cysteamine (ca) to yield the corresponding sulfinic acid products 3-sulfinopropionic acid (3spa), cysteine sulfinic acid (csa) and hypotaurine (ht), respectively [18]. In order to probe the rate-limiting chemical and non-chemical steps in Av MDO catalysis, the pH/D-dependent solvent kinetic isotope effects (SKIE) for these reactions were interrogated. However, before these experiments can be presented, it is necessary to discuss some fundamental control experiments first.

For dioxygenase reactions, oxygen is a co-substrate and thus it is important to verify that atmospheric O2-concentration is sufficient to saturate enzyme kinetics for all substrates utilized in solvent isotope experiments. This control was performed previously at pH 7.5 for all substrates (3mpa, cys and ca) [18]. As an addition control for these studies, this was repeated at pH 5.5, 7.5 and 10 for both 3mpa and cys to verify that pH does not influence O2-saturation. As before, steady-state rates for Av MDO at saturating substrate concentration are independent of oxygen within the range of 25–400 μM. These observations indicate that (regardless of pH) the apparent (for both substrates) must be substantially lower (~10×) than the lowest value of oxygen used (25 μM) [21,28]. Therefore, any differences observed in Av MDO reactivity cannot be attributed to incomplete O2-saturation. This also means that under these conditions, the reaction of the substrate-bound Av MDO with oxygen can be considered irreversible.

An additional factor to consider is the ‘coupling efficiency’ of the enzyme. The efficiency at which an oxygenase enzyme incorporates one mol of O2 into the product is commonly referred to as ‘coupling’. As kcat represents the zero-order limit of catalysis, the coupling efficiency for a dioxygenase can be obtained from the ratio of the kcat as measured from product formation divided by the kcat obtained from O2-consumption. It was previously reported that Av MDO reactions using either 3mpa (102 ± 8%) or cys (97 ± 6%) as a substrate were nearly fully coupled over the accessible pH range of the enzyme [6 < pH < 9] [18]. By contrast, reactions utilizing ca as a substrate exhibited significantly lower coupling (40 ± 9%). Regardless of substrate, the coupling efficiency of Av MDO was not influenced by D2O. Uncoupled reactions can result in the promiscuous release of reactive oxygen species such as H2O2, O2·− and ·OH, which can complicate interpretation of these experiments. For this reason, the pH/D-dependent solvent isotope studies are focused on Av MDO substrates 3mpa and cys, which exhibit stoichiometric coupling.

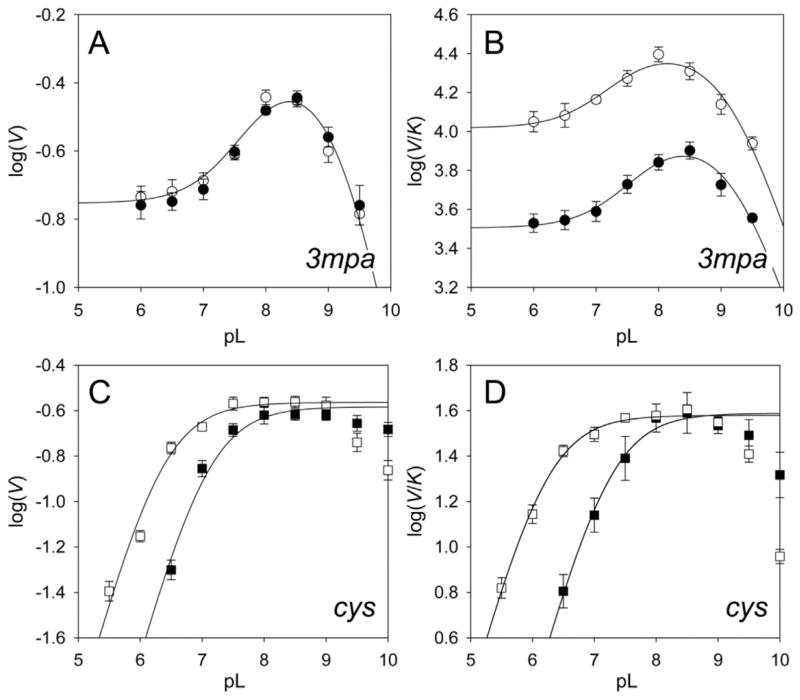

Insight into ionizable groups involved in catalysis can be obtained by measuring solvent isotope effects on the pH/D-dependence of both kcat and kcat/KM. The influence of pH on Av MDO catalysis was measured over the accessible pH range of the enzyme (6 < pH < 9). Fig. 2 illustrates the log(kcat)-pH (A) and log(kcat/KM)-pH profiles (B) obtained from the initial rate data of Av MDO reactions using 3mpa (H2O, white circle) as a substrate. For comparison the log(kcat)-pD and log(kcat/KM)-pD profiles obtained for 3mpa reactions are also included (black circles). Each point within these data sets was obtained by fitting the steady-state kinetic results observed at a fixed pL-value to the standard Michaelis- Menten equation. The error in each kinetic parameter obtained (kcat and kcat/KM) from these fits is indicated graphically using error bars.

Fig. 2.

pL-dependence of steady-state kinetic parameters of MDO using 3-mercaptopropionic acid (circle, A/B) and L-cysteine (square, C/D) as substrates. For both substrates, log(V) and log(V/K) pL-profiles were collected in H2O (white) and D2O (black) and fit to equations. (1) and/or (2). A summary of the results obtained from these fits are summarized in Table 1.

In reactions using 3mpa as substrate, both pH-profiles [kcat-pH and kcat/KM-pH] exhibit a skewed ‘bell shaped’ curve with two apparent pKa values. Within the acidic branch of this profile [6 < pH < 8], both data sets exhibit sigmoidal behavior bracketed by limiting nonzero plateaus at low and high pH. Following a short transition, kcat and kcat/KM values decrease beyond with a unitary slope. Over the entire pH range utilized in these experiments, both data sets (kcat and kcat/KM) can be reasonably fit to equation (1) (solid line). The limiting values of kcat spans 0.17 ± 0.01 s−1 (YL) to 0.45 + 0.06 s−1 (YH) at 20 °C. Likewise, the limiting values for kcat/KM within the sigmoidal region lie between 10,000 ± 1100 M−1 s−1 and 27,000 ± 3000 M−1 s−1, respectively. Relative to H2O reactions, the observed kcat values are unaffected for Av MDO assays carried out in D2O (Fig. 2A). By contrast, a significant decrease in kcat/KM is observed for 3mpa reactions carried out in D2O (Fig. 2B). The sigmoidal limits of kcat/KM-values in D2O lie between 3200 ± 200 M−1 s−1 and 9600 ± 1200 M−1 s−1, respectively.

For each pH-profile, the two ionizable groups (pKa1 and pKa2) were determined by fitting data to equation (1). From this analysis, the pKa values (pKa1, 7.8 ± 0.2) and (pKa2, 9.2 ± 0.1) were obtained from the 3mpa kcat-pH profile in H2O. Similarly, two pKa values (pKa1, 7.4 ± 0.2) and (pKa2, 9.1 ± 0.1) were obtained from the 3mpa kcat/KM–pH profile. As with H2O reactions, two ionizable groups are also observed in Av MDO D2O assays using 3mpa as a substrate. In fact, the log(kcat)-pD profile obtained is essentially super imposable with the results obtained in H2O. Thus, within experimental error, the presence of D2O has no influence on the pKa-values obtained from kcat data. By contrast, the value of pKa1 obtained from log(kcat/KM)-pD fits (7.8 ± 0.2) is shifted more basic by ΔpKa1 = + 0.4, whereas the value of pKa2 (9.2 ± 0.1) remains largely unperturbed. The increased in pKa1 is consistent with ionizable groups involved with catalysis [29,30].

The pL-profile for Av MDO catalyzed reactions utilizing cys as substrate (Fig. 2C and D) exhibits a ‘bell shaped’ curve suggesting two ionizable groups. However, the second pKa-value is predicted to fall outside of the pH range of the experimental data set (>10). Therefore, kcat- and kcat/KM results obtained in either H2O or D2O were fit to equation (2) to obtain pKa1. In this analysis, data collected beyond pH 9 was neglected. In cys reactions carried out in H2O, a pKa value of 6.3 ± 0.1 was obtained from log(kcat)-pH fits. As with 3mpa reactions, no significant perturbation is observed in the value of kcat in H2O (0.28 ± 0.02 s−1) as compared to that obtained in D2O (0.26 ± 0.02 s−1). However, the observed pKa-value is shifted up to 7.1 ± 0.1 (ΔpKa1=+0.8) in D2O. Similarly, the observed pKa-value (pKa1) obtained from log(kcat/KM)-pL fits of cys reactions in H2O are shifted upward to from 6.2 ± 0.1 to 7.2 ± 0.1 (ΔpKa1=+1.0) in D2O. Regardless, no solvent isotope effect is observed on either kcat or kcat/KM for Av MDO catalyzed reactions with cys. A summary of the all pH/D-dependent kinetic results is provided in Table 1.

For each substrate utilized (3mpa and cys), the solvent kinetic isotope effect (SKIE) on each steady-state kinetic parameters (kcat and kcat/KM) was determined within the pH/D-independent region of each pL-profile. For example, the kcat/KM-pL-profile for 3mpa (Fig. 2B) exhibits two pH-independent regions (pL ~ 6.0 and 8.2), both of which exhibit a solvent kinetic isotope effect of 2.7 ± 0.4. This value is significantly larger than possible if solely attributed to differences in the relative viscosity of a D2O solution as compared to H2O. Nevertheless, additional viscosity experiments are presented below to determine if the attenuation of the kcat/KM-values obtained with 3mpa in D2O has contributions from viscosity effects. Alternatively, as illustrated in Fig. 2C and D, neither kcat-pL nor kcat/KM-pL profiles for Av MDO catalyzed cys reactions exhibit solvent isotope effects beyond experimental error. Similarly, while the full pD-dependence was not determined for Av MDO catalyzed ca reactions; solvent isotope effects were not observed for either kcat or kcat/KM in assays using ca as a substrate at pL 6.0 or 8.2.

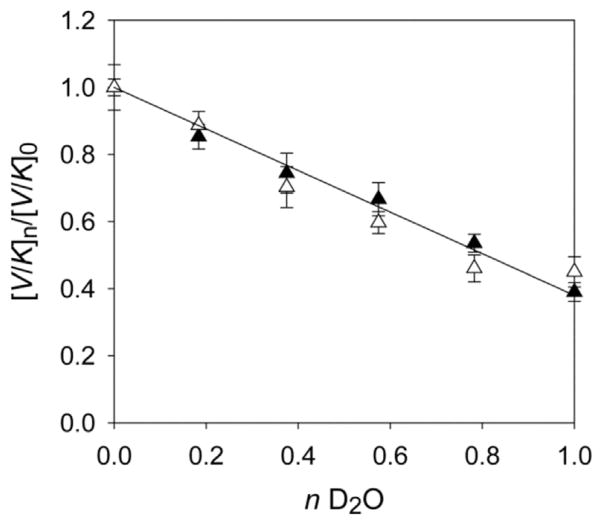

3.2. Proton inventories

Proton inventory experiments were performed to provide greater insight into the observed solvent isotope effect on kcat/KM for Av MDO catalyzed 3mpa reactions. In these experiments, both steady-state kinetic parameters (kcat and kcat/KM) were determined for various molar ratios of H2O and D2O at both pH/D-independent points (pL ~ 6.0 and 8.2). For each mole fraction of D2O measured, the value of kcat/KM observed ([V/K]n) is normalized for the value obtained in pure H2O ([V/K]0). As illustrated in Fig. 3, the relative change in kcat/KM ([V/K]0/[V/K]n) decreases with increasing D2O mole fraction. Proton inventory experiments performed at pL 6.0 (black triangles) and pL 8.2 (white triangles) exhibit nearly equivalent behavior indicating that there is no change in the number of rate limiting protonation steps at either the low or high branch of the pL-profile. Assuming a single proton in flight (solid line, y = 1), the best fit the observed proton inventory data to equation (3) was obtained for a solvent isotope effect of 2.63 ± 0.68 (R2 = 0.966). Within error, this is in good agreement with the value determined from the kcat/KM-pL profile (2.7 ± 0.4). This observation suggests a single solvent exchangeable proton is in flight prior to the first irreversible step. Further, the equivalence of proton inventories within each pL-independent limb (6.0 and 8.2) implies that the ionizable group associated with pKa1 is not the source of the rate-limiting proton.

Fig. 3.

Proton inventory of MDO catalyzed formation at pL 6.0 (black triangle) and 8.2 (white triangle). Plot of normalized V/K ([V/K]n/[V/K]0) versus mole fraction D2O (n). Experimentally determined SKIE values for kcat/KM were used to fit data to equation (3). Proton inventory data were fit assuming a single proton in flight (solid line, y = 1). Fitting results: D2OV/K = 2.63 ± 0.68, y = 1, R2 = 0.966.

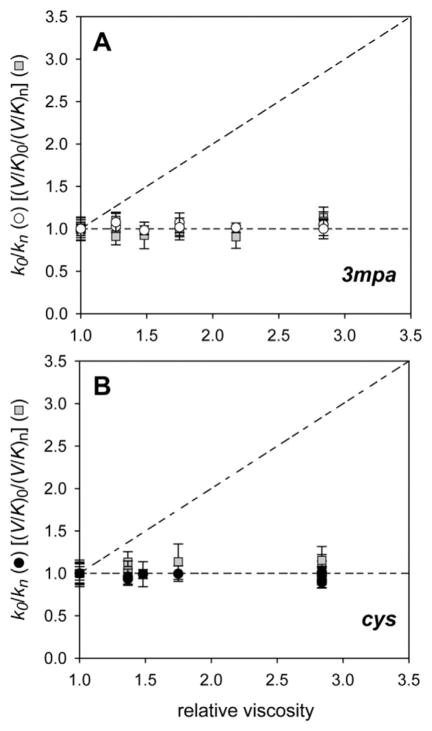

3.3. Viscosity effects

The possibility that diffusion controlled events such as substrate and/or product movement into and out of the active site limit the rate of catalysis was evaluated by measuring the perturbation of steady-state parameters (kcat and kcat/KM) as a function of solvent viscosity. Measurements were made at pH 8.2 as described in Material and Methods. For each assay, sucrose was added to increase the relative viscosity of the reaction buffer and the results were fit to equation (4). Fig. 4 illustrates the relative perturbation to kcat (or kcat/KM) obtained for reactions in the absence of viscosigen (k0) normalized for the values obtained at selected relative viscosities (kn). Assays using 3mpa and cys as a substrate for Av MDO are shown in Fig. 4 panels A and B, respectively. The dashed lines represent the theoretical limits of this experiment. A positive slope of 1.0 is expected if catalysis is fully diffusion-limited by nonchemical steps in catalysis. Alternatively, the horizontal line represents the expected result in the absence of any diffusional limitation [31]. The absence of any appreciable influence of solvent viscosity on kcat or kcat/KM for either substrate (3mpa or cys) clearly demonstrates that Av MDO catalysis is not limited by either substrate binding or product release. Moreover, this result verifies that the increased viscosity of D2O buffers does not contribute to the observed SKIE for Av MDO kcat/KM data obtained in 3mpa reactions.

Fig. 4.

Effect of solvent viscosity on the maximal rate (v0/[E]) of MDO catalyzed 3spa and csa formation. A. The effect of solvent viscosity on kcat (k0/kn) and kcat/KM [(V/K)0/(V/K)n] for 3spa formation is designated by circles (white) and squares (gray), respectively. B. For comparison, the effect of solvent viscosity on kcat [(k0/kn), black circle] and [(V/K)0/(V/K]n, gray square) for csa formation was also measured as a function of viscosity. The dashed lines represent the theoretical limits for diffusion-limited product release.

4. Discussion

Among thiol dioxygenase enzymes, the mammalian ‘Arg-type’ CDO has been extensively characterized spectroscopically [32–35], crystallographically [36–38] and kinetically [16,22,23]. However, almost no information is available regarding the relative timing of chemical and non-chemical steps in ‘Gln-type’ MDO catalyzed reactions. A significant point of divergence between CDO and MDO is with respect to substrate coordination to the mononuclear Fe-site. EPR spectroscopic studies indicate that substrate coordination to the Av MDO Fe-site is via thiolate-only [18]. By contrast, all known ‘Arg-type’ CDO enzymes bind cys via bidentate coordination of substrate-thiolate and neutral amine. This difference in Fe-coordination likely explains the relaxed substrate specificity reported among ‘Gln-type’ thiol dioxygenase enzymes [15,18]. Therefore, this subset of enzymes offers a unique point of comparison to better understand the significance of the first- and outer Fe-coordination sphere on catalysis and substrate-specificity among thiol dioxygenase enzymes.

For diffusion-controlled reactions in which product release is rate-limiting, kcat would be attenuated by increased solvent viscosity. Since addition of D2O to reaction buffers increases the relative viscosity of reaction mixtures, it is possible that viscosity effects contribute to the apparent solvent isotope effect. However, the results shown in Fig. 4 clearly demonstrate that, regardless of substrate, solvent viscosity has no impact on either kcat or kcat/KM. These experiments verify that non-chemical diffusional steps (product release and/or substrate binding) are not rate-limiting for Av MDO catalyzed reactions with 3mpa or cys. By contrast, product release in Mm CDO is partially rate-limiting [21]. However, substrate (and potentially product) coordination for CDO is bidentate, the resulting chelate effect likely stabilizes both the ES- and EP-complex. By contrast, substrate binding to the Av MDO Fe-site is believed to be via thiolate only, and thus product release is expected to be faster by comparison.

Within the experimental pH range of 6 < pH < 8.5, both kcat- and kcat/KM-pH profiles for Av MDO reactions using 3mpa as a substrate exhibit nonzero limiting values. Only at pH values beyond ~9 does the activity of Av MDO decrease linearly toward zero. By contrast, both kcat-pH profiles for enzymatic reactions using substrates bearing an amino functional group (cys and ca) decrease to zero within the acidic limb of the profile [18]. These observations are key to the development of a MDO kinetic model.

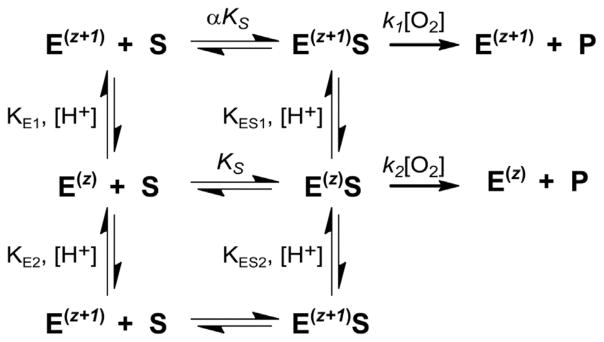

The pH-dependent behavior observed in 3mpa reactions can be rationalized assuming a diprotic model in which three ionic forms of the enzyme are present but only two of them are catalytically active [39,40]. As illustrated in Scheme 1, three ionic forms of the enzyme are produced by either protonation of the neutral enzyme (designated Ez) to form the cationic E(z+1) enzyme or deprotonation to yield the anionic E(z−1) form. The pH-dependent profile for 3mpa reactions suggest that both Ez and E(z+1) are catalytically active with rates reflected by the asymptotic limits of kcat within the acidic branch of the pH-profile (27,000 and 10,000 M−1 s−1, respectively). However, the doubly deprotonated enzyme is either unable to bind 3mpa or cannot reductively activate oxygen to generate product. Either way, the E(z−1) ionic form is catalytically inactive in 3mpa assays.

Scheme 1.

Proposed kinetic mechanism for Av MDO catalyzed 3mpa reaction.

In the context of the reaction scheme proposed, the observed pKa values in kcat- [pKa1 =7.4 ± 0.2; pKa2 = 9.1 ± 0.1] and kcat/KM-pH profiles [pKa1 = 7.8 ± 0.2; pKa2 = 9.2 ± 0.1] are attributed to catalytically essential ionizable amino acids within the free enzyme [27]. Further, the significant solvent isotope effect (2.7 ± 0.4) observed for 3mpa kcat/KM data suggests that proton-dependent steps play an important role in the initial reversible steps leading up to O2 binding.

Unambiguous identification of the specific ionizing amino acid residue associated with each pKa-value is not possible without direct comparison to Av MDO active site variants. While such experiments are currently ongoing, a reasonable mechanistic hypothesis can be formulated based on: (1) the pKa-values observed in kcat- and kcat/KM-data, (2) steady-state results obtained previously for H155A and Y157F Mm CDO variants, (3) and computationally validated EPR and CD/MCD studies [41,42].

The crystal structure for Av MDO is not available; however, structural comparisons can be made to the Pseudomonas aeruginosa ‘Gln-type’ MDO (PDB code 4TLF) which shares 69.5% sequence identity (84.8% similarity) with Av MDO [15]. As noted previously, the active site of Mm CDO is essentially equivalent to MDO with the notable exception of the C93-Y157 pair and R60 (replaced by Q62 in MDO). The pKa-values observed in 3mpa kcat- and kcat/KM-pL profiles (7.4–7.8), along with the ΔpKa (+0.4) observed in D2O reactions, is consistent with values reported for catalytically essential histidine residues [29,43]. As illustrated in Fig. 1, all known thiol dioxygenase enzymes have four conserved histidine residues within the active site. Three of which compose the Fe-coordination site (H89, H91 and H142 for Pa MDO, Fig. 1B). Protonation of any of these residues would result in loss of iron and inactivation of the enzyme. Since activity is not abolished below pKa1 in 3mpa reactions, it can be concluded that these residues are not protonated. This leaves only the conserved His-residue (H157) for further consideration.

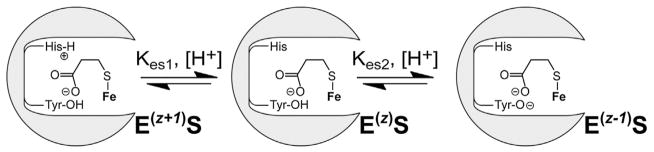

The hypothesis that pKa1 corresponds to H157 is attractive since it has been demonstrated previously that the equivalent residue in Mm CDO (H155) is critical for enzymatic activity. Indeed, despite comparable ferrous iron incorporation, the specific activity of the H155A Mm CDO variant is decreased by ~ 2-orders of magnitude relative to the wild-type enzyme [22]. Furthermore, recent spectroscopic (CD/MCD), crystallographic and computational studies of the Mm CDO H155A variant suggests that H155 serves as a hydrogen bond donor for the Y157 phenol group, thereby positioning the Y157 hydroxyl group of the C93-Y157 pair optimally to donate a hydrogen bond to the Fe-bound cys-carboxylate [42]. Assuming a similar function in the bacterial enzyme, the conserved H157 residue in Pa MDO would be expected to donate a hydrogen bond to the O-atom of the Y159 hydroxyl group to promote interaction with the substrate-carboxylate. This hypothesis presents an attractive explanation for the role of the ‘catalytic triad’ of Ser-His- Tyr residues universally conserved among thiol dioxygenases [44]. In this model, the hydroxyl group of S155 donates a hydrogen bond to the Nε-atom of H157 to align the opposite Nδ-atom for hydrogen bond donation to the O-atom of the Y159 phenol group. Protonation of H159 would disrupt this hydrogen bond network and result in formation of a positive charge within the enzymatic active site pocket resulting in attenuation of enzymatic activity below pKa1.

By extension, the basic pKa2-value observed in 3mpa reactions is close to values typically associated with tyrosine residues (pKa ~10). Furthermore, despite stabilizing a ferrous iron resting state, the Y157F (equivalent to Y159 of Pa MDO) variant of Mm CDO is catalytically inactive, thereby establishing that this residue is also essential for native catalysis [22]. Computational studies validated by EPR spectroscopy confirm that the hydroxyl-group of Y157 within the Mm CDO active site directly interacts with the carboxylate-group of the Fe-bound substrate (cys) [22]. It is therefore reasonable to expect that Y159 of MDO is the second ionizable group observed in 3mpa pL-profiles. A schematic representation summarizing the proposed substrate-bound ionic enzymes forms [E(z+1)S, EzS and E(z−1)S] is shown in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2.

Proposed substrate-bound ionic enzymes forms [E(z+1)S, EzS and E(z−1)S].

Since both pKa-values are observed in kcat- and kcat/KM-pH profiles, it can also be argued that a proton-dependent step is involved in the chemical steps [27]. However, this can also be rationalized in the context of the proposed ionic enzyme forms produced as a function of pH.

As with most non-heme oxidase/oxygenase enzymes, binding and reductive activation of molecular oxygen is gated by substrate coordination to the Fe-site [18]. While the precise mechanism remains a matter of considerable debate, it has been proposed that the coordination of substrate to the Fe-site alters the FeII/FeIII redox couple and/or induces key conformational changes that facilitate direct O2-coordination and activation [45–47]. Thus, charge stabilization and geometry of the substrate-bound Fe-site are critical for enzymatic activity.

In the doubly deprotonated E(z−1) form, electrostatic repulsion between the Y159-tyrosinate and 3mpa-carboxylate group would significantly inhibit substrate binding to the opposite face of the 3-His facial triad. For perspective, the distance separating Y159 O-atom and the Fe-bound solvent W3 is 2.67 Å [Fig. 1B]. The short distance separating two negative charges would produce a significant columbic force, likely resulting in both geometric and electrostatic distortions at the substrate-bound Fe-site. Whether the anionic E(z−1) form cannot bind 3mpa or the E(z−1)S complex is unable to activate oxygen; the result is the same, abolishment of enzymatic activity beyond pKa2. This hypothesis also provides an explanation for the absence of a basic pKa in kcat-pH profiles obtained in assays using ca as a substrate [18]. Unlike 3mpa and cys, cysteamine lacks a carboxylate group. Since there is no electrostatic repulsion between the substrate and the anionic E(z−1) enzyme, neither substrate-binding nor subsequent O2-activation are attenuated under basic conditions. Furthermore, the retention of E(z−1) activity in reactions utilizing ca demonstrates that the second protonation step does not irreversibly inactivate MDO.

Similarly, the differential pH-dependent behavior exhibited within the acidic limb of 3mpa reactions as compared to substrates bearing a positively charged quaternary amine (cys and ca) can also be explained by this kinetic mechanism. As noted previously, both kcat and kcat/KM decrease for Av MDO catalyzed 3mpa reactions, but activity is not abolished within the acidic limb of the pH profile. Conversely, steady-state parameters approach zero for cys and ca enzymatic reactions below pKa1. Protonation of H157 would produce a cationic E(z+1) enzyme form. The positive charged imidazole ring of H157 is positioned along the substrate-binding face of the 3-His facial triad (3.90 Å distance from the Fe-bound solvent molecule W3). Therefore, cationic substrates such as cys and ca would experience considerable electrostatic repulsion under acidic conditions. Finally, the zwitterionic cys substrate has both amine- and carboxylate-groups, thus only the neutral Ez enzyme form retains activity, whereas the ionic E(z+1) and E(z−1) forms are inactive. As expected, this results in an inverted ‘bell shaped’ curve in kcat-pH profiles.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (CHE) 1213655 (B.S.P.) and National Institute of Health (NIGMS) 1 R15 GM117511-01 (B.S.P.). The authors acknowledge NSF financial support (CRIF:MU CHE-0840509) for the purchase of the JEOL ECA500 500 MHz FT-NMR spectrometers and The University of Texas at Arlington Shimadzu Center for Advanced Analytical Chemistry for the use of HPLC and LC-MS/MS instrumentation. We would also like to acknowledge Professor Tim Larson, Virginia Tech (Department of Biochemistry) for the IPTG inducible Azotobacter vinelandii MDO expression vector.

Abbreviations

- CDO

cysteine dioxygenase

- MDO

3-mercaptopropionic acid dioxygenase

- 3mpa

3-mercaptopropionic acid

- cys

L-cysteine

- ca

cysteamine (2-aminoethanethiol)

- 3spa

3-sulfinopropionic acid

- csa

cysteine sulfinic acid

- ht

hypotaurine

- Mm

Mus musculus

- Av

Azotobacter vinelandii

- Pa

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- SKIE

solvent kinetic isotope effect

References

- 1.Stipanuk MH. Sulfur amino acid metabolism: pathways for production and removal of homocysteine and cysteine. Annu Rev Nutr. 2004;24:539–577. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.012003.132418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ewetz L, Sorbo B. Characteristics of the cysteinesulfinate-forming enzyme system in rat liver. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1966;128:296–305. doi: 10.1016/0926-6593(66)90176-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sorbo B, Ewetz L. The enzymatic oxidation of cysteine to cysteinesulfinate in rat liver. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1965;18:359–363. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(65)90714-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lombardini JB, Singer TP, Boyer PD. Cysteine oxygenase. J Biol Chem. 1969;244:1172–1175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dominy JE, Jr, Simmons CR, Karplus PA, Gehring AM, Stipanuk MH. Identification and characterization of bacterial cysteine dioxygenases: a new route of cysteine degradation for eubacteria. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:5561–5569. doi: 10.1128/JB.00291-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordon C, Emery P, Bradley H, Waring H. Abnormal sulfur oxidation in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lancett. 1992;229:25–26. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90144-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heafield MT, Fearn S, Steventon GB, Waring RH, Williams AC, Sturman SG. Plasma cysteine and sulfate levels in patients with motor neurone, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 1990;110:216–220. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90814-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.James SJ, Cutler P, Melnyk S, Jernigan S, Janak L, Gaylor DW, Neubrander JA. Metabolic biomarkers of increased oxidative stress and impaired methylation capacity in children with autism. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:1611–1617. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deth R, Muratore C, Benzecry J, Power-Charnitsky VA, Waly M. How environmental and genetic factors combine to cause autism: a redox/methylation hypothesis. NeuroToxicology. 2008;29:190–201. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reddie KG, Carroll KS. Expanding the functional diversity of proteins through cysteine oxidation. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2008;12:746–754. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winyard PG, Moody CJ, Jacob C. Oxidative activation of antioxidant defence. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:453–461. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trachootham D, Alexandre J, Huang P. Targeting cancer cells by ROS-mediated mechanisms: a radical therapeutic approach? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:579–591. doi: 10.1038/nrd2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Behave DP, Muse WB, Carroll KS. Drug targets in mycobacterial sulfur metabolism. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2007;7:140–158. doi: 10.2174/187152607781001772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Driggers CM, Hartman SJ, Karplus PA. Structures of Arg- and Gln-type bacterial cysteine dioxygenase homologs. Protein Sci. 2015;24:154–161. doi: 10.1002/pro.2587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tchesnokov EP, Fellner M, Siakkou E, Kleffmann T, Martin LW, Aloi S, Lamont IL, Wilbanks SM, Jameson GNL. The Cysteine dioxygenase homologue from pseudomonas aeruginosa is a 3-mercaptopropionate dioxygenase. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:24424–24437. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.635672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li W, Pierce BS. Steady-state substrate specificity and O2-coupling efficiency of mouse cysteine dioxygenase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2015;565:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Easson LH, Stedman E. Studies on the relationship between chemical constitution and physiological action: molecular dissymmetry and physiological activity. Biochem J. 1933;27:1257–1266. doi: 10.1042/bj0271257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pierce BS, Subedi BP, Sardar S, Crowell JK. The “Gln-Type” thiol dioxygenase from azotobacter vinelandii Is a 3-mercaptopropionic acid dioxygenase. Biochemistry. 2015;54:7477–7490. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Notomista E, Lahm A, Di Donato A, Tramontano A. Evolution of bacterial and archaeal multicomponent monooxygenases. J Mol Evol. 2003;56:435–445. doi: 10.1007/s00239-002-2414-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pierce BS, Gardner JD, Bailey LJ, Brunold TC, Fox BG. Characterization of the nitrosyl adduct of substrate-bound mouse cysteine dioxygenase by electron paramagnetic resonance: electronic structure of the active site and mechanistic implications. Biochemistry. 2007;46:8569–8578. doi: 10.1021/bi700662d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crawford JA, Li W, Pierce BS. Single turnover of substrate-bound ferric cysteine dioxygenase with superoxide anion: enzymatic reactivation, product formation, and a transient intermediate. Biochemistry. 2011;50:10241–10253. doi: 10.1021/bi2011724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li W, Blaesi EJ, Pecore MD, Crowell JK, Pierce BS. Second-sphere interactions between the C93-Y157 cross-link and the substrate-bound Fe site influence the O(2) coupling efficiency in mouse cysteine dioxygenase. Biochemistry. 2013;52:9104–9119. doi: 10.1021/bi4010232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crowell JK, Li W, Pierce BS. Oxidative uncoupling in cysteine dioxygenase is gated by a proton-sensitive intermediate. Biochemistry. 2014;53:7541–7548. doi: 10.1021/bi501241d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emanuele JJ, Fitzpatrick PF. Mechanistic studies of the flavoprotein tryptophan 2-monooxygenase. 1. Kinetic mechanism. Biochemistry. 1995;34:3710–3715. doi: 10.1021/bi00011a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Denu JM, Fitzpatrick PF. pH and kinetic isotope effects on the oxidative halfreaction of D-amino-acid oxidase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:15054–15059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cleland WW. [22] the use of pH studies to determine chemical mechanisms of enzyme-catalyzed reactions. In: Daniel LP, editor. Methods Enzymol. Academic Press; 1982. pp. 390–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cook PF, Cleland WW. Enzyme Kinetics and Mechanisms. Garland Science; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smitherman C, Gadda G. Evidence for a transient peroxynitro acid in the reaction catalyzed by nitronate monooxygenase with propionate 3-nitronate. Biochemistry. 2013;52:2694–2704. doi: 10.1021/bi400030d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quinn DM, Sutton LD. Theoretical basis and mechanistic utility of solvent isotope effects. In: Cook PF, editor. Enzyme Mechanism from Isotope Effects. CRC Press; 1991. pp. 73–126. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Venkatasubban KS, Schowen RL. The proton inventory technique. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1984;17:1–44. doi: 10.3109/10409238409110268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gadda G, Fitzpatrick PF. Solvent isotope and viscosity effects on the steady-state kinetics of the flavoprotein nitroalkane oxidase. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:2785–2789. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tchesnokov EP, Wilbanks SM, Jameson GNL. A strongly bound high-spin iron(II) coordinates cysteine and homocysteine in cysteine dioxygenase. Biochemistry. 2011;51:257–264. doi: 10.1021/bi201597w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blaesi EJ, Fox BG, Brunold TC. Spectroscopic and computational investigation of iron(III) cysteine dioxygenase: implications for the nature of the putative superoxo-Fe(III) intermediate. Biochemistry. 2014;53:5759–5770. doi: 10.1021/bi500767x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gardner JD, Pierce BS, Fox BG, Brunold TC. Spectroscopic and computational characterization of substrate-bound mouse cysteine dioxygenase: nature of the ferrous and ferric cysteine adducts and mechanistic implications. Biochemistry. 2010;49:6033–6041. doi: 10.1021/bi100189h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pierce BS, Gardner JD, Bailey LJ, Brunold TC, Fox BG. Characterization of the nitrosyl adduct of substrate-bound mouse cysteine dioxygenase by electron paramagnetic resonance: electronic structure of the active site and mechanistic implications†. Biochemistry. 2007;46:8569–8578. doi: 10.1021/bi700662d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCoy JG, Bailey LJ, Bitto E, Bingman CA, Aceti DJ, Fox BG, Phillips GN., Jr Structure and mechanism of mouse cysteine dioxygenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:3084–3089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509262103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ye S, Wu XA, Wei L, Tang D, Sun P, Bartlam M, Rao Z. An insight into the mechanism of human cysteine dioxygenase: key roles of the thioether-bonded tyrosine-cysteine cofactor. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:3391–3402. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609337200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Driggers CM, Cooley RB, Sankaran B, Hirschberger LL, Stipanuk MH, Karplus PA. Cysteine dioxygenase structures from pH 4 to 9: consistent Cyspersulfenate formation at intermediate pH and a Cys-bound enzyme at higher pH. Mol Microbiol. 2013;425:3121–3136. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Segel IH. Enzyme Kinetics: Behavior and Analysis of Rapid Equilibrium and Steady-state Enzyme Systems. Wiley; New York: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Czerwinski RM, Harris TK, Johnson WH, Legler PM, Stivers JT, Mildvan AS, Whitman CP. Effects of mutations of the active site arginine residues in 4-oxalocrotonate tautomerase on the pKa values of active site residues and on the pH dependence of catalysis. Biochemistry. 1999;38:12358–12366. doi: 10.1021/bi9911177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li W, Blaesi EJ, Pecore MD, Crowell JK, Pierce BS. Second-Sphere Interactions between the C93–Y157 cross-link and the substrate-bound Fe site influence the O2 coupling efficiency in mouse cysteine dioxygenase. Biochemistry. 2013;52:9104–9119. doi: 10.1021/bi4010232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blaesi EJ, Fox BG, Brunold TC. Spectroscopic and computational investigation of the H155A variant of cysteine dioxygenase: geometric and electronic consequences of a third-sphere amino acid substitution. Biochemistry. 2015;54:2874–2884. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schowen KB, Schowen RL. [29] Solvent isotope effects on enzyme systems. In: Daniel LP, editor. Methods in Enzymology. New York: 1982. pp. 551–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simmons CR, Liu Q, Huang Q, Hao Q, Begley TP, Karplus PA, Stipanuk MH. Crystal structure of mammalian cysteine dioxygenase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:18723–18733. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601555200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Solomon EI, Brunold TC, Davis MI, Kemsley JN, Lee SK, Lehnert N, Neese F, Skulan AJ, Yang YS, Zhou J. Geometric and electronic structure/function correlations in non-heme iron enzymes. Chem Rev. 2000;100:235–349. doi: 10.1021/cr9900275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Solomon EI, Decker A, Lehnert N. Non-heme iron enzymes: contrasts to heme catalysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3589–3594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0336792100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Costas M, Mehn MP, Jensen MP, Que LJ. Dioxygen activation at mononuclear nonheme iron active sites: enzymes, models, and intermediates. Chem Rev. 2004;104:939–986. doi: 10.1021/cr020628n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]