Abstract

Collaborative partnerships between community-based clinicians and academic researchers have the potential to improve the relevance, utility, and feasibility of research, as well as the effectiveness of practice. Collaborative partnership research from a variety of fields can inform the development and maintenance of effective partnerships. In this paper we present a conceptual model of research-community practice partnership derived from literature across disciplines and then illustrate application of this model to one case example. The case example is a multi-year partnership between an interdisciplinary group of community-based psychotherapists and a team of mental health researchers. This partnership was initiated to support federally funded research on community-based out-patient mental health care for children with disruptive behavior problems, but it has evolved to drive and support new intervention studies with different clinical foci. Lessons learned from this partnership process will be shared and interpreted in the context of the presented research-practice partnership model.

Keywords: Collaboration, Partnership, Community-based care

Broad awareness and concern about the gap between research and practice in mental health care has driven calls for more bi-directional or multi-directional knowledge exchange involving active collaboration and partnership between researchers and community providers at all stages of research and practice implementation (Addis, 2002; Beutler, Williams, Wakefield, & Entwistle, 1995; Bradshaw & Haynes, 2012; Sobell, 1996; Wells & Miranda, 2006;). The papers in this special issue contribute to a growing literature examining such partnerships and how they can advance and improve both mental health research and practice (e.g., Bradshaw & Haynes, 2012; Chorpita & Mueller, 2008; Chorpita et al., 2002; Lindamer et al., 2009; McMillen, Lenze, Hawley, & Osborne, 2009; Southam-Gerow, Hourigan, & Allin, 2009; Wells, Miranda, Bruce, Alegria, & Wallerstein, 2004). This growing literature highlights how partnerships between mental health providers (hereinafter referred to as therapists) and researchers can promote the relevance, feasibility, and utility of research, as well as the potential effectiveness of care, but it also highlights challenges in building and sustaining these types of partnerships. More explicit study of partnership processes is needed to capitalize on all the tacit knowledge that partnership participants have gained through varied collaborative efforts and to ultimately advance collaborative practice (Bradshaw & Haynes, 2012; Kellam, 2012; Reimer, Kelley, Casey, & Haynes, 2012).

A variety of disciplines offer useful theoretical and empirical examinations of collaboration processes and factors that influence the success of collaborative partnerships. In this paper, we present a conceptual framework for research-community practice partnership (RCPP) informed primarily by the business organizational management and public health literature, as well as other collaborative partnership research and our own ongoing work (e.g., Brookman-Frazee, Stahmer, Lewis, Feder & Reed, 2012). This framework can be used to inform decisions on the development and maintenance of partnerships in community-based psychotherapy research, as well as to interpret variable success in partnership efforts. We begin with a brief overview of the literature that influenced the development of this framework. We then use a case study to illustrate the components of the framework as it is applied specifically for community psychotherapy research. The case example is a multi-year research-practice partnership developed in one large county to support community-based research on publicly-funded out-patient psychotherapy for children and families. We highlight lessons learned regarding the development, maintenance, benefits, and challenges of research-practice partnerships.

Background in Collaboration Models from Different Disciplines

Literature addressing knowledge exchange, collaboration, and partnership in disciplines outside mental health provides valuable theoretical models, practical strategies, and emerging empirical support for effective collaborative partnership processes. In particular, relevant literature from the fields of business management and public health is summarized below; this literature provides the background for the conceptual model of Research-Community Practice Partnership presented at the end of this section.

Sources of Literature on Collaboration

Business Management

Two broad areas in organizational science namely, (1) collaborative management research and (2) inter-organizational relationships, are particularly applicable to RCPP in the mental health services context. Collaborative management research examines how researchers and organizations work together to increase competence of organizations and systems, and increase the relevance of research (Pasmore, Woodman, & Simmons, 2008). Research in the second area of inter-organizational relationships addresses interactions between organizations (e.g., strategic alliances, joint ventures, networks), seeking better understanding of relationship structures, functions, and consequences (Cropper, Huxham, Ebers, & Ring, 2008). Both these areas of inquiry are linked to action research which strives to develop practical knowledge through participatory processes, and to generate pragmatic solutions to practical problems (Bradbury, 2008).

Organizational learning and knowledge management

The two related areas of management science described above share a common focus on organizational and individual learning processes. Terms such as knowledge transfer (both unidirectional and bi-directional) and knowledge creation have been used to describe collaborative learning processes (Huxham & Hibbert, 2008; Muthusamy & White, 2005). Knowledge transfer is certainly very relevant to current efforts in mental health to implement evidence-based practices in community settings. Relatedly, implementation science also examines how knowledge or technology is exchanged across organizations and the extent to which this exchange results in sustainable change in the capacity or performance of the organizations involved. Qualitative research suggests that knowledge exchange in a collaborative partnership can range from strategic (and potentially selfish) acquisition of beneficial knowledge to more reciprocal sharing of knowledge and collaborative explorations of innovative solutions to specific problems (Huxham & Hibbert, 2008). The literature on learning and knowledge management has important implications for the process of knowledge exchange in research-community partnerships. One of the major challenges in mental health research-community practice partnerships is the extent to which the knowledge transfer is intended to be reciprocal (i.e., knowledge exchange) or unidirectional. One of the criticisms of traditional models of evidence-based practice dissemination was that it was not a reciprocal knowledge exchange process (Garland, Hurlburt, & Hawley, 2006a)

Community health partnerships

Public health also has a rich history in research-practice collaboration. In order to address key factors associated with behavioral and environmental health risk, poor health and well-being (e.g., substance abuse, teenage pregnancy, HIV, environmental pollution), and the resulting overburdened healthcare system, many communities have formed multi-sector collaborative partnerships to work on strategies to reduce risk (Alexander, Comfort, Weiner, & Bogue, 2001). Partners may include hospitals, service organizations, insurers, government agencies, community interest groups, school districts, academic institutions, and individual citizens who join together to address social issues of importance to the community (Alexander et al., 2001; Daley, Roberts, Hahn, O'Flaherty, & Reznik, 1999; Suarez-Balcazar, Harper, & Lewis, 2005). The literature on community health partnerships in public health provides case examples and empirical studies on the key characteristics of successful (i.e., sustainable with intended outcomes) collaborative partnerships (Alexander et al., 2003), and methods to evaluate the processes and impacts of partnerships (Shortell et al., 2002). The extensive theoretical, empirical, and practical literature on public health research-community partnerships (Lasker & Weiss, 2003; Lasker, Weiss, & Miller, 2001) can be applied to RCPP in mental health.

Community-based participatory research (CBPR)

CBPR is a model of community health partnership that is relatively common in public health. The literature on CBPR is replete with conceptual and increasingly empirical work addressing the functions, processes, and outcomes of collaborative health partnerships. It is strongly linked to, if not often defined by, efforts to reduce health care disparities through active involvement of community members, organizations, and researchers in all aspects of the research process (Israel, Schultz, Parker, & Becker, 1998). Core principles of CBPR dictate that it: (1) is participatory and cooperative, involving a joint, equitable decision making process; (2) is a co-learning process based on a mutually respectful partnership between researchers and community members; and (3) involves system development and local capacity building, ideally achieving a balance between research and action (Minkler, 2004; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003). CBPR provides an important framework for research-practice partnership efforts in mental health services (Wells & Miranda, 2006). The lessons learned from CBPR can provide direction for practical considerations of developing, sustaining, and evaluating research-community partnerships. Some of the greatest challenges include equitable decision-making regarding work expectations, resource generation and allocation, as well as the challenge of balancing research and action priorities. The CBPR model has been adapted by mental health researchers and community providers to select and test psychosocial interventions in the community (Blumenthal et al., 2006).

Rationale for Collaboration

There are a number of reasons why groups or organizations may decide to partner with others. In business, organizations can achieve desired outcomes through a “collaborative advantage” process when they partner with other organizations that have complementary resources and/or expertise (Huxham, 2003; Huxham & Vangen, 2005). They can build capacity in each collaborating organization which could not be achieved working in isolation (Hardy, Phillips, & Lawrence, 2003). Partnerships can also be formed for the more explicit purpose of specific knowledge transfer, in which partners acquire new skills or technologies from another (e.g., evidence-based practices in mental health), or for knowledge creation, in which innovation grows out of the process of social interactions that occur in ongoing collaborations (e.g., identification of practice-based evidence) (Hardy et al., 2003). These reasons for collaborating are not mutually exclusive and, to some extent, each are often present in collaborative partnerships.

In the context of mental health research specifically, RCPPs have the potential to increase the relevance and impact of mental health services research (Wells et al., 2004) by improving the ecological validity and clinical utility of research. Further, they can improve the efficiency of community-based research by improving access to service data (McMillen et al., 2009). Lastly, RCPPs have the potential to facilitate implementation of EBPs in usual care mental health services (Garland, Plemmons, & Koontz, 2006b; McMillen et al., 2009; Sobell, 1996), and bridge the gap between research and usual care practice, thus improving care.

Conceptual Framework for Research-Community Partnerships

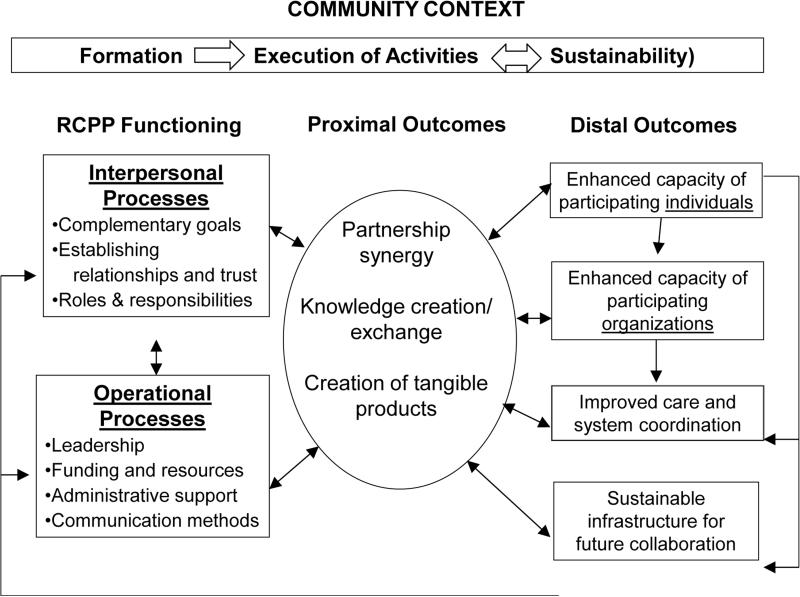

Figure 1 outlines an RCPP framework based on the conceptual and theoretical literature as well as “lessons learned” from case studies. This framework was adapted from the research community partnership framework outlined in Brookman-Frazee, Stahmer and colleagues (2012). The framework illustrates the iterative and dynamic process of RCPP development and the potential outcomes of these efforts. It highlights the multiple dynamic phases of RCPPs and the collaborative processes which occur in the community context of the RCPP. It posits that RCPP functioning (including both interpersonal and operational functioning) can lead to partnership synergy (proximal outcome), which can then lead to a variety of potential distal outcomes, including benefits to the individuals, organizations and communities. Following the presentation of the framework, we provide a brief description of the case example RCPP and then illustrate components of the framework with examples from this RCPP.

Figure 1.

Model of research-community practice partnerships.

Adapted from Brookman-Frazee, Stahmer et al. (2012)

Case Example: “Practice & Research: Advancing Collaboration” (PRAC) Project

The aims of the PRAC project were to rigorously examine the psychotherapeutic treatment processes and outcomes of community-based care for children with disruptive behavior problems and their families (Garland et al., 2006a, 2006b, 2010). Table 1 provides an outline of key aspects of this project. Prior to initiating the research study, the study PI identified the largest contracted providers of publicly-funded mental health services in the county and invited agency leaders to identify one well-respected representative from each program (an “opinion leader”) to join a partnership group with a team of researchers. Thus, a collaborative group of community-based therapists and researchers was formed and this group met monthly to refine the research questions and methods, and maximize feasibility of the study (including development of participant recruitment procedures strategies to minimize data collection burden). The study design required collecting videotapes of all therapy sessions for therapists and families who consented to participate. This descriptive study offered no training to therapists nor any significant resources beyond video recording equipment for their offices. The study was being initiated in the context of broader national and local tensions in the field regarding pressure to implement evidence-based practices and some criticism of community-based care; thus there were significant potential challenges to achieving high rates of voluntary participation in a study designed to rigorously examine “usual care” practice. Active involvement of key opinion leaders in each of the six participating clinics was thus essential for building the trust necessary to achieve high rates of voluntary participation and for assuring that study methods fit well within the usual care context. For example, therapist partners’ input was essential in refining the methods of characterizing psychotherapy processes to maximize relevance (i.e., ecological validity) to community practice.

Table 1.

Case Example: Practice and Research: Advancing Collaboration (PRAC)

| Funding source(s) | NIMH R01 University Academic Senate Research Grant |

| Purpose of research study | Phase 1: To characterize community-based psychotherapy process and outcome Phase 2: To develop supervision tools to improve the use of evidence-based strategies in community-based psychotherapy |

| Applying Model of Research Community Partnership | |

| Phase of partnership | Sustainability (execution of revised activities and new RCPPs) |

| RCP functioning: Interpersonal Processes – Role of community partners | Phase 1: To advise the research team on measure development, data collection and interpretation of findings Phase 2: Work with the research team to generate supervision tools Participate in data collection related to characterizing supervision practice Advise on new studies relevant to practice (see AIM Study) |

| RCP functioning: Operational Processes | Bi-weekly meetings with CASRC/ UCSD researchers and community therapists Regular email communication Coordinator as “hub” of partnership information and activities Meetings held at CASRC |

| Proximal outcomes | Developed sustained relationships (as evidenced by retention of RCPP members) Generated new topic of mutual interest, revised purpose, and identified new members Publications reporting observational data of psychotherapy process (e.g., Brookman-Frazee, Garland, Taylor, & Zoffness, 2009; Brookman-Frazee, Haine, Baker-Ericzen, Zoffness, & Garland, 2010; Garland et al., 2010; Garland, Haine-Schlagel, Accurso, Baker-Ericzen, & Brookman-Frazee, 2012; Haine-Schlagel, Brookman-Frazee, Fettes, Baker-Ericzen, & Garland, 2012 & Haine-Schlagel, Fettes, Garcia, Brookman-Frazee, & Garland, 2013) Published qualitative study on partnership process (Garland et al., 2006b) Coordinated joint research-practice conference to share research findings and discuss topics of mutual interest to researchers and clinicians |

| Distal outcomes | Developed sustainable infrastructure for revised partnership goals (e.g., Supervision Pilot study) Built capacity in CASRC and community clinics new studies using RCPPs (e.g., AIM study) Improved capacity in community services Improved community-based care for children with disruptive behavior disorders (anticipated) |

As discussed below, trust-building was a critical early step in building this collaborative relationship. A qualitative study of the development of this partnership was conducted and revealed that all participants emphasized the importance of trust-building, as well as the need to develop shared meanings around key concepts (Garland et al., 2006b). These themes are common across partnership efforts (Bradshaw & Haynes, 2012; Sobell, 1996). The partnership was ultimately successful in supporting the completion of the study, including collection of over 3000 videotaped therapy sessions. Upon completion of data collection, the partnership group participated actively in interpretation and dissemination of the findings. This PRAC RCPP has since evolved into a few new RCPPs addressing specific clinical research issues described later. The partnership processes and factors affecting its success are outlined below based on the different components of the conceptual model of research-practice partnership – its developmental phases, processes, and benefits (Figure 1).

Dynamic Phases of Partnerships: Formation, Execution, Sustainability

Formation (Initiation)

Initiation of an RCPP should be based on shared interests or complementary goals. The literature on partnership functioning suggests that forming and establishing successful RCPPs requires consideration of the following key issues:

What is the purpose of the RCPP?

There are a number of potential reasons why an RCPP might be initiated for mental health services research:

1. To facilitate the efficiency or feasibility of a specific research project when community stakeholders have knowledge or information that is particularly relevant to the research

The PRAC RCPP was initiated to facilitate data collection and maximize relevance of the PRAC research project, including specifically assistance with participant recruitment, refinement of the observational coding system used to characterize observed psychotherapy process, and reinforcement of the focus on “usual care” practice throughout the project.

2. To identify practice-relevant research questions

The purpose of the PRAC RCPP evolved over several years from a supportive mechanism to facilitate the initial PRAC observational study to a more equitable forum to identify new practice-relevant research questions (e.g., clinical supervision methods) to be explored in future research.

3. To increase opportunities for funding

Some partnerships may be initiated specifically for the purpose of qualifying for and/or identifying new funding opportunities. When the initial funding that supported the PRAC RCPP ended, the group volunteered to work together to identify future research and practice funding initiatives.

4. To improve practice

Virtually all research-practice partnerships likely have the implicit, if not explicit goal of ultimately improving the quality of care. Research-practice knowledge exchange and specifically efforts to encourage the integration of research-derived knowledge and practice are designed to improve care and to improve research. The PRAC RCPP sought to “bridge the gap” between research and practice by strengthening working relationships between researchers and therapists, implicitly building more interest in research-based knowledge in the practice community and building improved knowledge and appreciation of practice realities in the research community (Sobell, 1996).

Who will participate?

Setting the foundation for a successful RCPP requires that stakeholders make a commitment to collaborate. This can be particularly challenging on top of already busy professional commitments. Careful attention needs to be paid to with whom and with what organizations one collaborates, including decisions about representation at different levels of an organization (i.e., upper management, front-line staff, etc.). The appropriate partners will largely depend on the purpose of the RCPP. Given that the PRAC study was focused on individual therapist practice, the partners were active therapists, as opposed to administrators or policy-makers.

Literature suggests that members should possess complementary, but non- redundant knowledge and experiences that can be combined and contextualized to facilitate knowledge creation and innovation (Levin & Cross 2004). In our studies, we have found that it is also important that participants demonstrate an openness to and respect for new ideas and perspectives, as well as enthusiasm and optimism about the potential for the collaborative process. In the PRAC RCPP researchers clearly communicated how and why community therapists were critical to driving and refining the most important research questions, facilitating data collection procedures, interpreting findings, and planning next steps. One of the themes that emerged from the qualitative self-study of the PRAC RCPP formation was that initially, some of the therapists felt somewhat skeptical about their role, expressing concern that their participation would be superficial or perfunctory (Garland et al., 2006b). This is a potential risk for research-practice partnerships (Sobell, 1996) and thus, it was critical to demonstrate early on that input from all participants would be taken seriously and would drive real changes in the project.

How will the RCPP operate?

Initial considerations for operational processes are discussed below.

Execution of Activities

Once a new RCPP is formed, specific project tasks need to be accomplished but there must also be flexibility to shift priorities based on partnership evolution and knowledge exchange. In the PRAC partnership, there was sometimes a tension between the need to complete specific project tasks (such as revising and pilot-testing the observational coding measurement system used to characterize psychotherapy process), and partners’ desire for more open-ended exploratory dialogue about psychotherapy processes and challenges, relevant research, etc. This was particularly true as trust and mutual respect grew and partners recognized the value of sharing ideas. Open dialogue, in and of itself, can foster a stronger integration of science and practice (Sobell, 1996), but, in our experience, it needs to be complemented by task focused work. The section on “RCPP Functioning” below describes some of the operational supports or processes used to support completion of project tasks.

Sustainability

There has been more research on strategies for initiating collaborative partnerships than there has been on strategies to sustain and grow partnerships. However, public health scholars have highlighted the importance of attention to sustainability, as well as many of the challenges (Lasker & Weiss, 2003; Shortell et al., 2002). Sustainability should be considered a phase in the evolution of partnership and an indicator of partnership success (Cropper, 1996). Sustainability will likely be required to achieve a long term impact on community practice outcomes as well as research. The following issues are critical to maintenance of collaborative relationships and partnership infrastructure:

What should be sustained?

As RCPPs achieve their initial goals and/or the funding for a specific project ends (if applicable), frank discussions need to occur about whether the partnership will continue and if so, how it will be supported and what the goals will be. Once the initial aims of the PRAC RCPP were achieved and the research funding that provided infrastructure support ended, the RCPP group debated next steps. The members decided to continue meeting without compensation for their time and without staffing support. Members reported that the collaboration experience and dialogue were intellectually stimulating and professionally valuable. The group then worked to identify new potential funding initiatives and it has served as a forum for broad discussions about research questions of interest to clinicians and researchers. The initial PRAC RCPP has now evolved into a few specific special interest groups addressing different clinical foci such as mental health treatment for Autism Spectrum Disorders and strategies to improve parents’ participatory engagement in psychotherapy.

Resources

For RCPPs like PRAC's that are initiated for the purpose of a particular grant or project, the end of funding represents a critical crossroads. In a study of characteristics of successful partnerships, Shortell and colleagues (2002) found that those most successful demonstrated an “ability to patch” (p. 64), referring to efforts to reposition competencies and assets in order to address changing needs and priorities (Shortell et al., 2002). “Patching” resources may require that participating organizations donate resources in the absence of external funding. The necessary process of blending and repositioning resources likely requires planning before the end of funding. As the PRAC RCPP has evolved into multiple special interest RCPs, there has been significant patching from different funding mechanisms and staffing resources. Flexibility and ongoing negotiation of goals and resources has been identified as essential to effective partnership (Reimer et al., 2012).

RCPP Functioning

In this section we describe the essential interpersonal and operational processes of collaboration, followed by the proximal and distal outcomes that can be achieved.

Managing Interpersonal Processes

Complementary goals

Collaborative partnerships usually need to address multiple mutually rewarding goals, including specific goals of the collaborative partnership, as well as those of the participating individuals and organizations (Bradshaw & Haynes, 2012; Huxham, 2003; Spoth & Greenberg, 2005) We have found that it is not necessary for individual/organizational goals to be the same for all partners, however, these goals should be complementary and combined to form a shared vision and a mutually rewarding purpose for the collaborative activities. For example, when the initial PRAC project was completed, the RCPP members continued to work together and one of the mutual interests (among researchers and therapists) was to learn more about “usual” clinical supervision practices in publicly-funded out-patient clinics. The research and therapist representatives had distinct, but complementary goals motivating pursuit of this activity. The researchers were highly motivated to describe usual supervision methods to learn about this mechanism as a potential vehicle for the implementation of evidence-based practices in these clinics. The therapists were interested in learning more about supervision in order to identify resources needed to improve supervision and to identify useful supervision methods, but implementation of EBP was not the primary focus for them.

Establishing interpersonal relationships, trust and shared language

As noted previously and mentioned across all areas of partnership study, building interpersonal trust and a shared language are essential for successful collaboration. An empirical investigation of strategic alliances found that reciprocal commitment, trust, and mutual influence between collaborative partners were all factors positively associated with successful knowledge exchange (Muthusamy & White, 2005). While not surprising, these findings highlight the importance of explicit attention to the role of interpersonal relationships and interaction in partnership. Given some historical tensions between those who research and those who practice mental health care, mutual trust is not a given and needs to be fostered over time (Garland et al., 2006b; Sobell, 1996). Overall, there needs to be some level of basic trust between both individuals and organizations to initiate the relationship; ideally, trust grows as the collaborative group engages in mutually rewarding activities (Huxham, 2003; Vangen & Huxham, 2003). As in other relationships, trust between collaborative partners grows when members demonstrate responsiveness to each party's needs and willingness to go above and beyond an agreed scope of work (Becker, Israel, & Allen, 2005; Pan et al., 2006).

Qualitative research on behaviors that build interpersonal trust suggests that common language and terminology is important in social exchanges (Abrams, Cross, Lesser, & Levin, 2003). Like others, (e.g., Bradshaw & Haynes, 2012), we have found that developing a common language is a critical communication need to advance partnership between researchers and therapists. It has been particularly helpful to avoid using jargon that may be unknown or may hold different meanings for different stakeholders. It is also important to be aware that certain words/terms can be interpreted differently. For example, the term “directive” (in reference to psychotherapeutic techniques) has evoked discussions of varied interpretations and affective reactions between researchers and therapists in our partnership group.

Roles and responsibilities

Individual participants in an RCP enter the partnership with a conferred “status” reflecting their specific professional identity (e.g., Counselor, Psychologist, Professor, Intern, Graduate Student). Power differentials will likely impact the process of collaboration and knowledge exchange and therefore there needs to be explicit attention given to how power is distributed among members of the collaborative for decision-making. Overall, it may be important to address members’ expected roles and unique contributions, and the distribution of power at the outset, as well as explicitly establishing norms for working together (Becker et al., 2005). Then, any changes in power or responsibilities can be discussed with more ease.

Managing Partnership Operations

Unlike formal organizations, or even organized community groups, RCPPs develop their own operational procedures in order to execute the collaborative activities. Although this can be challenging due to limited resources, it also provides great flexibility in how the partnership is managed. The following are practical considerations to address as operational procedures are developed:

Leadership and Power

Leader(s) of RCPPs may be in unique positions in that they may be facilitating the collaborative process without any real resources or power over the individual partners (Alexander et al., 2001). Therefore, effective RCPP leaders may differ from effective leaders of traditional organizations. In a qualitative study of leadership in public-private health partnerships, Alexander and colleagues (2001) found that effective leaders of collaborative partnerships find an optimal balance between power sharing and control, process and results, continuity and change, and interpersonal trust and formalized procedures (Alexander et al., 2001). These themes are consistent with other observations of successful partnerships in mental health contexts (e.g., Reimer et al., 2012).

In the PRAC RCPP, the balance of power between partners depended on the nature of the task. While the goals of CBPR, for example, include egalitarian leadership, we have found that it is important to acknowledge differences in skills for certain tasks, and match leadership responsibilities to skill sets. For example, while preparing a grant application, the research members of the partnership in PRAC led the agenda and had more influence than community therapists. Alternatively, when the task was to engage therapist colleagues in an experiential workshop regarding application of research findings to community practice, therapist partners led given their credibility among community therapists. Overall, we have found that the balance of influence between partners and stakeholders shifts naturally given the nature of the task and the respective skills of different partners.

Administrative support

If possible, it may be beneficial to have someone who is employed by the collaborative rather than by one of the partnering organizations to provide administrative coordination. Further, it is potentially helpful to hire staff members who represent community stakeholder groups, especially if they will be interfacing with the broader community (Pan et al., 2006). In the PRAC RCPP however, the administrative support has primarily been linked to our research center given that the original funding came from a research grant to center investigators. While this approach facilitates central coordination, it also has the relative disadvantage of being largely managed by researcher stakeholders. In other collaborative projects at our center, we have shared staff with community-based organizations, which has resulted in increased communication and mutual understanding of each organization's contexts and priorities.

Communication methods

Just like for any group, effective and efficient communication is critical for a collaborative partnership. It is important to consider how RCPP activities will be recorded and shared within the group and externally to broader constituencies. This is particularly important, as there may be turnover in individual participants and members of participating organizations. While web-based communications methods such as Google Groups can greatly facilitate communication, we have found that face-to-face meetings are essential for partnership development, particularly early in the groups’ development as trust is building. Reimer and colleagues (2012) similarly emphasize the importance of face-to-face meetings to build collaboration and explicitly to acknowledge ongoing cultural differences. Although efficient, one of the challenges to using alternative web-based communication methods is the variability in familiarity with these applications across all potential partnership groups.

Proximal (Process) Outcomes

Demonstrating positive impacts of partnerships can be challenging (Butterfoss & Francisco, 2004) and there are few established methods to empirically examine RCPP outcomes. The most obvious proximal outcome of an RCPP is establishing the collaborative relationships. In fact, some suggest that the greatest value of collaboration may be the development of the relationships, rather than achieving specific goals (Huxham & Vangen, 2003).

“Partnership synergy,” refers to a process whereby the knowledge and skills of diverse partners are combined to (a) foster new and better ways to achieve goals, (b) plan innovative, comprehensive programs, and (c) strengthen the relationship with the broader community (Lasker et al., 2001; Weiss, Anderson, & Lasker, 2002). Scholars are working on operationalizing the important construct of partnership synergy and developing measures to assess the extent to which collaborative groups are achieving it (Daley et al., 1999; Weiss et al., 2002).

Knowledge creation and exchange

Knowledge exchange and creation is a reflection of successful partnership synergy. In the business management context, one of the primary goals of a strategic alliance collaboration is for each of the partners to learn from the other. Organizational scholars have therefore adapted measures of collaboration to assess knowledge exchange (Muthusamy & White 2005). Knowledge exchange was a primary goal of the PRAC RCPP. Our qualitative investigation of the partnership process found ample evidence of such exchange. Researchers reported shifts in their understanding of “real world” practice challenges and greater respect for the immediate and often risky clinical challenges therapists faced. They reported greater respect for therapists’ skills based on the partnership experience. Likewise, therapists reported significant shifts in their attitudes about research, with greater appreciation for the rigor of the research process and the ultimate aim of improving care (Garland et al., 2006b). One of the benefits of research-practice collaboration is improved understanding and mutual respect across roles (Sobell, 1996).

Creation of tangible products

Typically, the most concrete and measurable outcome of a collaborative partnership is the extent to which the stated goals and objectives are achieved. These outcomes will likely be tied to grant funding and/or service provision, either of which requires regular monitoring of progress in activities. On this basis, the PRAC RCPP met its proximal outcome goals. Participation in the research study was strong (approximately 80% of therapists who were randomly selected for recruitment agreed to participate) and data collection was completed successfully. We attribute this success to the PRAC RCPP members (opinion leaders) serving as study champions within each of the clinics throughout the study.

Distal Outcomes

There are many potential distal outcomes of RCPPs. Some are more direct, and easier to quantify than others, and they can occur at individual, organizational and community levels.

Positive impacts of participating members

The most direct distal outcomes include the new skills that individuals develop to apply in their respective settings, and their ability to collaborate and communicate with others from different backgrounds and perspectives. In the PRAC RCPP, one of the best examples of this type of a desirable distal outcome was the fact that one of the therapist partners began leading presentations about evidence-based practices for therapist colleagues and trainees based largely on his partnership experience. Other therapist members are now serving as expert consultants on a variety of federally funded research projects. In addition, recognizing the value of therapist partnership, the original research participants have forged new collaborative relationships with an expanded network of therapist participants in our community and beyond, and have extended some partnerships to include parents, administrators and other key stakeholders (Brookman-Frazee, Drahota, & Stadnick, 2012; Brookman-Frazee, et al., 2012))

Across a few RCPPs in our research center, we have found that community members’ (therapists, administrators, and family members) interpretation of research findings have been particularly valuable and have guided how we discuss our findings in publications and presentations. Participants have told us that the partnership experience has been very intellectually stimulating – at times challenging – but overall very enriching, personally and professionally. Participants come away with new perspectives that reportedly enhance their abilities to succeed within their own organizations, participate in new collaborative ventures, and communicate more effectively with other stakeholder groups to strengthen the integration of research and practice.

Positive impacts on participating organizations

The potential positive organizational impacts include organizational learning, improved culture, and capacity-building for innovative new partnerships. Research confirms that organizations learn from collaborative experiences and develop improved collaborative skills (Simonin, 1997). This collaborative “know how” can build an organization's capacity to participate in future collaborative efforts. As the PRAC RCP has evolved into different collaborative pursuits, the lessons learned from each iteration informs the next. For example, we have learned to acknowledge that the goals of researchers and community members may not always be aligned and need to be continually negotiated. Additionally, we have learned the importance of including opinion leaders in RCPPs to maximize the impact of the RCPP on partnering organizations. Partnering community organizations have benefited from developing relationships with our research center which facilitate future collaborative efforts. They have learned the value of research to their organizations, and the benefits of having their clinicians participate in research studies.

Sustainability of partnership infrastructure

As discussed above, it takes time and resources to develop an infrastructure for RCPs. This infrastructure, which includes willing participants and effective communication mechanisms, is an important product of the RCPP. An established infrastructure improves efficiency and potential effectiveness of future collaborations because relationships are already built and operational processes are already established. We've experienced this as new RCPPS have capitalized on the initial infrastructure developed by the PRAC RCPP, including the trust built between researchers and community practitioners.

Improved community-based care or system capacity

The ultimate distal goals of research-community partnership are to improve care and to improve the utility of research toward that end. Indicators of improved care would include reduced disparities in access to care and improved clinical effectiveness of care. Unfortunately, we do not yet have data to test the extent to which the PRAC RCPP and its subsequent evolutions have improved care in the system overall. The baseline clinical effectiveness of usual care is limited, and many different interventions are needed to improve care (Garland et al., 2013), but our belief, based on experience, is that fostering collaborative partnership between researchers and therapists provides a fertile environment for improvement efforts.

Challenges to Collaboration

Despite the multiple potential benefits of RCPPs, there are many challenges to collaboration that potentially limit achievement of desired outcomes. Collaborative groups can experience “collaborative inertia” resulting in slow progress and minimal productivity (Huxham, 2003). Although a comprehensive discussion of challenges is beyond the scope of this paper, it is important to acknowledge that there are several key potential obstacles to successful collaboration that are particularly relevant for RCPPs in mental health. For the sake of brevity, some of these key challenges and potential solutions are outlined in Table 2. Many of these challenges were encountered in our case example and are mentioned above. For example, communication challenges related to different interpretations of key terms (e.g., “evidence,” and “directive” approaches to psychotherapy) were encountered early on in our partnership process. The broad challenge of building trust and the time required to do so is also a consistent theme in our experience. We offer brief suggestions for potential solutions to the array of key partnership challenges to reinforce the fact that despite some challenges, partnerships can be sustained and the potential benefits outweigh the challenges.

Table 2.

RCP challenges and potential solutions

| Challenge | Description/ examples | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of consensual aims | Researchers and practitioners may have differing goals that reflect the tension between relevance and rigor. | Get started on some mutually agreed upon action that can be decided upon without full consensus on overall goals (Huxham, 2003; Huxham & Vangen, 2003) |

| Communication | Stakeholders may use different language inhibiting clear communication with other stakeholders (Garland et al., 2006b; Huxham & Vangen, 2003) | Identify terms that evoke strong reactions from partners that may have different meaning to different stakeholder groups. Provide specific definitions how terminology is used. |

| Time | Trusting relationships take time to develop. Stakeholders may operate on different time tables. |

Researchers build time into their proposed funding periods and research plans to develop relationships with partners (Frazier, Formoso, Birman, & Atkins, 2008). |

| Managing interpersonal relationships | People make up RCPs, and have idiosyncrasies and personal agendas.(Sink, 1996) Personality issues are not insignificant in their impact on process and outcome. This may include personalities of individual participants or of those in member organizations (Daley et al., 1999). | Develop roles, expectations and processes, and norms to deal with inevitable conflicts that will arise (Becker et al., 2005). |

| Lack of understanding of partnering organizations | Stakeholders may not understand context (demands, expectations, culture) or others’ organizations. | Individuals invest effort into understanding the world as perceived by the other participant (Huxham & Vangen, 2003). |

| Lack of organizational support | Stakeholders may have competing demands and expectations from their organizations (e.g., academic institutions may have few incentives for participating in community work) (Reznik, Hahn, Morris, & Daley, 2000). | Communication with organizations about the value and potential benefit of collaboration, emphasizing the products of the RCPP. |

| Balancing methodological rigor and relevance | Some may be concerned that conducting research in collaboration with the community may somehow reduce the methodological rigor of the science due to “compromises” that need to be made to satisfy all partners (e.g., choosing designs that do not include random assignment or selecting outcome measures that are less reliable). | Reframe rigor and relevance as overlapping concepts that reinforce each other (Pasmore, Stymne, Shani, Mohrman, & Adler, 2008) Conduct scientifically rigorous and clinically relevant research through the use of mixed qualitative and quantitative data and a combination of descriptive and experimental research. |

Conclusions

Given increased national attention to the gap between research and community practice and encouragement for stronger collaboration between researchers and community stakeholders, more scholarly attention to the complexities of collaborative processes and potential outcomes is warranted. The RCPP framework presented here is based on the conceptual literature, case studies and emerging empirical research on collaboration from multiple disciplines, as well as our own practical experience. It highlights the dynamic phases of RCPPs, the complex processes that make up their functioning, and the potential proximal and distal outcomes. We illustrated the framework constructs using practical examples from our multi-year RCPP experience. Not only has collaboration between researchers and other stakeholders in our work been particularly enriching for the individuals and organizations involved, we have directly experienced how these partnerships facilitate bridging the ubiquitous gap between research and practice, ultimately enhancing both enterprises.

Our field is poised to advance beyond strong rhetoric about the value of interdisciplinary research-practice partnerships to increased operational support and study of such partnerships. This shift requires greater explicit attention to partnership development in graduate training, grant funding, academic review and promotion priorities, and scientific publication avenues. We need to move beyond valuing the ideal of partnership to producing empirical evidence of the impact of partnerships on mental health care effectiveness to reinforce the cost-benefit of investment in partnership development and maintenance. Psychotherapy researchers and practitioners are poised to lead these efforts given their expertise in the interpersonal processes essential to such collaborative endeavors.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R01MH66070, K23MH077584, and P30 MH074778. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes 905 of Health. The authors thank Drs. Sandra Daley, Sheila Broyles, Barry Hill and Robin Taylor.

References

- Abrams LC, Cross R, Lesser E, Levin DZ. Nurturing Interpersonal Trust in Knowledge-Sharing Networks. The Academy of Management Executive (1993) 2003;17:64–77. [Google Scholar]

- Addis ME. Methods for Disseminating Research Products and Increasing Evidence-Based Practice: Promises, Obstacles, and Future Directions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2002;9:367–378. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JA, Comfort ME, Weiner BJ, Bogue R. Leadership in Collaborative Community Health Partnerships. Nonprofit Management and Leadership. 2001;12:159–175. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JA, Weiner BJ, Metzger ME, Shortell SM, Bazzoli GJ, Hasnain-Wynia R, et al. Sustainability of collaborative capacity in community health partnerships. Medical Care Research and Review. 2003;60:130S–160S. doi: 10.1177/1077558703259069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker AB, Israel BA, Allen AJ. Strategies and techniques for effective group process in CBPR partnerships. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Beutler LE, Williams RE, Wakefield PJ, Entwistle SR. Bridging scientist and practitioner perspectives in clinical psychology. American Psychologist. 1995;50:984–994. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.50.12.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal RN, Jones L, Fackler-Lowrie Ellison, M., Booker T, Jones F, Wells KB. Witness for Wellness: Preliminary Findings from a Community-Academic Participatory Mental Health Initiative. Ethnicity & Disease. 2006;16(Supplement 1):18–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury H. Quality and “actionability”: What action researchers offer from the tradition of pragmatism. In: Shani AB, Mohrman SA, Pasmore WA, Stymne B, Adler N, editors. Handbook of Collaborative Management Research. 1 ed. Sage Publications, Inc.; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2008. pp. 583–600. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw CP, Haynes KT. Building a scince of partnership-focused research: Forging and sustaining partnerships to support child mental health prevention and services research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2012;39:221–224. doi: 10.1007/s10488-012-0427-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookman-Frazee LI, Drahota A, Stadnick N. Training community mental health therapists to deliver a package of evidence-based practice strategies for school-age children with autism spectrum disorders: A pilot study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42(8):1651–1661. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1406-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookman-Frazee L, Garland AF, Taylor R, Zoffness R. Therapists' attitudes towards psychotherapeutic strategies in community-based psychotherapy with children with disruptive behavior problems. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2009;36:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10488-008-0195-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookman-Frazee L, Haine RA, Baker-Ericzen M, Zoffness R, Garland AF. Factors associated with use of evidence-based practice strategies in usual care youth psychotherapy. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2010;37:254–269. doi: 10.1007/s10488-009-0244-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookman-Frazee L, Stahmer AC, Lewis K, Feder JD, Reed S. Building a research-community collaborative to improve community care for infants and toddlers at-risk for autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Community Psychology. 2012;40:715–734. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterfoss FD, Francisco VT. Evaluating community partnerships and coalitions with practitioners in mind. Health Promotion Practice. 2004;5:108–114. doi: 10.1177/1524839903260844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Mueller CW. Toward new models for research, community, and consumer partnerships: Some guiding principles and an illustration. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2008;15:144–148. [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Yim LM, Donkervoet JC, Arensdorf A, Amundsen MJ, McGee C, Morelli P. Toward large-scale implementation of empirically supported treatments for children: A review and observations by the Hawaii Empirical Basis to Services Task Force. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2002;9:165–190. [Google Scholar]

- Cropper S. Collaborative working and the issue of sustainability. In: Huxham C, editor. Creating collaborative advantage. Sage; London: 1996. pp. 80–100. [Google Scholar]

- Cropper S, Huxham C, Ebers M, Ring PS. Oxford Handbook of Inter-organizational Relations. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Daley SP, Roberts C, Hahn H, O'Flaherty V, Reznik V. The San Diego New Beginnings Collaborative: Principles and assessment of a community-government-university partnership. NHSA Dialog: A Research-to-Practice Journal for the Early Intervention Field. 1999;3:98–127. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier SL, Formoso D, Birman D, Atkins MS. Closing the research to practice gap: Redefining feasibility. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2008;15:125–129. [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Brookman-Frazee L, Hurlburt MS, Accurso EC, Zoffness R, Haine RA, Ganger W. Mental health care for children with disruptive behavior problems: A view inside therapists’ offices. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61:788–795. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.8.788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Haine-Schlagel R, Accurso EC, Baker-Ericzen MJ, Brookman-Frazee L. Exploring the effect of therapists’ treatment practices on client attendance in community-based care for children. Psychological Services. 2012;9:74–88. doi: 10.1037/a0027098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Haine-Schlagel R, Brookman-Frazee L, Baker-Ericzen MJ, Trask EV, Fawley-King K. Improving community-based mental health care for children: Translating knowledge into action Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services. 2013;40:6–22. doi: 10.1007/s10488-012-0450-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Hurlburt MS, Hawley KM. Examining psychotherapy processes in a services research context. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2006a;13:30–46. [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Plemmons D, Koontz L. Research-practice partnership in mental health: Lessons from participants. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2006b;33(5):517–528. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haine-Schlagel R, Brookman-Frazee L, Fettes DL, Baker-Ericzén MJ, Garland AF. Therapist focus on parent involvement in community-based youth psychotherapy. Journal of Child & Family Studies. 2012;21:646–656. doi: 10.1007/s10826-011-9517-5. NIHMS326709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haine-Schlagel R, Fettes DL, Garcia AR, Brookman-Frazee L, Garland AF. Consistency with evidence-based treatments and perceived effectiveness of children's community-based care. Community Mental Health Journal. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10597-012-9583-1. NIHMS433673. DOI: 10.1007/s10597-012-9583-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy C, Phillips E, Lawrence TB. Resources, knowledge and influence: The organizational effects of interorganizational collaboration. Journal of Management Studies. 2003;40:321–347. [Google Scholar]

- Huxham C. Theorizing collaboration practice. Public Management Review. 2003;5 [Google Scholar]

- Huxham C, Hibbert P. Manifested attitudes: Intricacies of inter-partner learning in collaboration. Journal of Management Studies. 2008;45:502–529. [Google Scholar]

- Huxham C, Vangen S. Researching organizational practice through action research: Case studies and design choices. Organizational Research Methods. 2003;6:383–403. [Google Scholar]

- Huxham C, Vangen S. Managing to Collaborate: The Theory and Practice of Collaborative Advantage. Routledge; London: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. [Review]. Annual Review of Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellam SG. Developing and maintaining partnerships as the foundation of implemenation and implementation science: Reflections over a half century. Administration and policy in Mental Health. 2012;39:317–320. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0402-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasker RD, Weiss ES. Broadening participation in community problem solving: a multidisciplinary model to support collaborative practice and research. Journal of Urban Health-Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2003;80:14–47. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasker RD, Weiss ES, Miller R. Partnership synergy: A practical framework for studying and strengthening the collaborative advantage. Milbank Quarterly. 2001;79:179. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin DZ, Cross R. The strength of weak ties you can trust: The mediating role of trust in effective knowledge transfer. Management Science. 2004;50:1477–1490. [Google Scholar]

- Lindamer LA, Lebowitz BD, Hough RL, Garcia P, Aquirre A, Halpain MC, Jeste DV. Improving care for older persons with schizophrenia through an academic-community partnership. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59:236–239. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.3.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindamer L, Lebowitz B, Hough R, Garcia P, Aguirre A, Halpain M, Jeste D. Establishing an implementation network: Lessons learned from community-based participatory research. Implementation Science. 2009;4:17. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillen CJ, Lenze SL, Hawley KM, Osborne VA. Revisiting practice-based research networks as a platform for mental health services research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2009;36:308–321. doi: 10.1007/s10488-009-0222-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M. Ethical challenges for the “outside” researcher in community-based participatory research. Health Education & Behavior. 2004;31:684–697. doi: 10.1177/1090198104269566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community based participatory research in health. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Muthusamy SK, White MA. Learning and knowledge transfer in strategic alliances: A social exchange view. Organization Studies. 2005;26:415–441. [Google Scholar]

- Pan A, Daley S, Rivera L, Williams K, Lingle D, Reznik V. Understanding the role of culture in domestic violence: The ahimsa project for safe families. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2006;8:35–43. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-6340-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasmore WA, Stymne B, Shani AB, Mohrman SA, Adler N. The promise of collaborative management research. In: Shani AB, Mohrman SA, Pasmore WA, Stymne B, Adler N, editors. Handbook of Collaborative Management Research. 1 ed. Sage Publications, Inc.; Thousand Oaks: 2008. pp. 7–32. [Google Scholar]

- Pasmore WA, Woodman RW, Simmons AL. Toward a more rigorous, reflective, and relevant science of collaborative management research. In: Shani AB, Mohrman SA, Pasmore WA, Stymne BN, Adler N, editors. Handbook of collaborative management research. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2008. pp. 567–582. [Google Scholar]

- Reimer M, Kelley SD, Casey S, Haynes KT. Developing effective research-practice partnerships for creating a culture of evidence-based decision making. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2012;39:248–257. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0368-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reznik VM, Hahn H, Morris E, Daley S. Community-university partnerships: Policy and legacy. California Western Law Review. 2000;36:403–416. [Google Scholar]

- Shortell SM, Zukoski AP, Alexander JA, Bazzoli GJ, Conrad DA, Hasnain-Wynia R, et al. Evaluating partnerships for community health improvement: Tracking the footprints. Journal of Health Politics Policy and Law. 2002;27:49–92. doi: 10.1215/03616878-27-1-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonin BL. The importance of collaborative know-how: An empirical test of the learning organization. The Academy of Management Journal. 1997;40:1150–1174. [Google Scholar]

- Sink D. Five obstacles to community-based collaboration and some thoughts on overcoming them. In: Huxham C, editor. Creating collaborative advantage. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1996. pp. 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC. Bridging the gap between scientists and practitioners: The challenge before us. Behavior Therapy. 1996;27:297–320. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southam-Gerow MA, Hourigan SE, Allin RB., Jr Adapting evidence-based mental health treatments in community settings: Preliminary results from a partnership approach. Behav Modif. 2009;33:82–103. doi: 10.1177/0145445508322624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth RL, Greenberg MT. Toward a comprehensive strategy for effective practitioner-scientist partnerships and larger-scale community health and well-being. Am J Community Psychol. 2005;35:107–126. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-3388-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Balcazar Y, Harper GW, Lewis R. An interactive and contextual model of community-university collaborations for research and action. Health Educ Behav. 2005;32:84–101. doi: 10.1177/1090198104269512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vangen S, Huxham C. Enacting leadership for collaborative advantage: Dilemmas of ideology and pragmatism in the activities of partnership managers. British Journal of Management. 2003;14:S61–S76. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss ES, Anderson RM, Lasker RD. Making the most of collaboration: exploring the relationship between partnership synergy and partnership functioning. Health Educ Behav. 2002;29:683–698. doi: 10.1177/109019802237938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells KB, Miranda J. Promise of interventions and services research: Can it transform practice? Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2006;13:99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Wells KB, Miranda J, Bruce ML, Alegria M, Wallerstein N. Bridging community intervention and mental health services research. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:955–963. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.6.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]