Abstract

The mechanisms underlying the effects of neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) induced repetitive limb movement therapy after incomplete spinal cord injury (iSCI) are unknown. This study establishes the capability of using therapeutic NMES in rodents with iSCI and evaluates its ability to promote recovery of interlimb control during locomotion. Ten adult female Long Evans rats received thoracic spinal contusion injuries (T9; 156 ± 9.52 Kdyne). 7 days post-recovery, 6/10 animals received NMES therapy for 15 min/day for 5 days, via electrodes implanted bilaterally into hip flexors and extensors. Six intact animals served as controls. Motor function was evaluated using the BBB locomotor scale for the first 6 days and on 14th day post-injury. 3D kinematic analysis of treadmill walking was performed on day 14 post-injury. Rodents receiving NMES therapy exhibited improved interlimb coordination in control of the hip joint, which was the specific NMES target. Symmetry indices improved significantly in the therapy group. Additionally, injured rodents receiving therapy more consistently displayed a high percentage of 1:1 coordinated steps, and more consistently achieved proper hindlimb touchdown timing. These results suggest that NMES techniques could provide an effective therapeutic tool for neuromotor treatment following iSCI.

1. Introduction

Several rehabilitative therapy approaches have been utilized to promote plasticity of the nervous system after incomplete spinal cord injury (iSCI) for improved recovery of locomotor function [1–3]. These include partial body weight supported treadmill training, robotic assist and electrical stimulation assisted gait training. These approaches aim to enhance spinal plasticity below the level of the injury, not by promoting regeneration of nerve fibers through the damaged cord, but by enhancing use-dependent synaptic plasticity in the lumbar regions [1, 4]. However, the mechanisms that underlie these therapeutic approaches are not yet well understood, the procedures for selecting the best time window for administering the therapeutic intervention are yet to be determined, and the efficiency of combined pharmacological and physical interventions is uncertain.

During neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES), low levels of electrical current are used to stimulate nerves that innervate specific muscles to cause active contraction. The volumetric electric field produced by the stimulation excites the nerve and, depending on the stimulation characteristics, activates both the sensory and motor fibers. NMES has been used after SCI to decrease the fatigability of muscles [5], reverse muscle atrophy and increase bone density [6, 7]. It has also been used to assist walking in people with iSCI to improve their functional mobility and walking speed [8, 9]. The use of direct electrical stimulation of the common peroneal nerve in combination with a partial body weight supported treadmill walking therapy paradigm has been shown to improve intralimb coordination during overground walking [10]. A pilot study utilizing this combination therapy after acute iSCI reports accelerated recovery [11]. One study suggests that electrical stimulation of sensory afferents could contribute to recovery after iSCI [12].

As most of the recent studies involving the therapeutic use of electrical stimulation after SCI have been done in humans, lack of non-invasive diagnostics and adequate advances in neuroimaging hinder our ability to investigate the neuroantaomical and molecular mechanisms of neuroplasticity following NMES therapy in spinal cord injured subjects. The use of an appropriate animal model for NMES therapy after iSCI would enable investigations across scales from the gene to the system level. Well-characterized rodent models for iSCI that mimic contusion injury in humans have been developed [13, 14]. We have previously implemented the ability to perform NMES-assisted hindlimb movement in paraplegic rodents [15–17]. In rodents with complete spinal cord transection, passive cyclic exercise training has shown preservation of the lumbar motoneuronal dendritic arbor that integrates multiple inputs and is usually reduced after the injury [18, 19]. We hypothesized that similarly, even non-weight bearing NMES therapy which produces active contraction of muscles would have a favorable influence on spinal plasticity. Additionally, a non-weight bearing intervention, if demonstrated to produce sufficient improvements, could be more readily translated for the widespread use for treatment after incomplete spinal cord injury. Here, we present for the first time a contusion rodent injury model for NMES-assisted hindlimb movement in which we specifically test the hypothesis that NMES movement therapy after iSCI leads to improved recovery of locomotor control as reflected by interlimb coordination during locomotion.

2. Methods

2.1. Study groups

The study was conducted on adult female Long Evans rats (Charles River, 250–300 g). Ten rats received thoracic spinal contusion injuries and were assigned to one of two groups: those receiving hindlimb movement therapy using NMES (iSCITNS, n = 6) or those receiving no training (iSCINT, n = 4). Prior to surgery, animals were preconditioned to walking on a treadmill and to quietly sit on a platform such that the head, forelimbs and midline of the torso were supported and their hindlimbs were hanging freely. For comparison, data were also analyzed from an additional six uninjured (intact) rats that were part of a previous study [20]. Rats were individually housed in an AALAC accredited university animal care facility with a 12 h light/dark cycle, with access to food and water ad libitum. All procedures listed were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. Surgical procedures

Previously, we have recorded electromyogram (EMG) activity during treadmill walking using implanted electrodes from multiple hindlimb muscles in intact rodents [20], developed techniques for implanting stimulation electrodes at the motor points of hindlimb muscles [15], examined the ability to chronically maintain these electrodes in paraplegic rodents [17, 21] and established stimulation paradigms for providing hip movement NMES therapy using adaptive control algorithms [16]. The electrode implantation and contusion injury procedures utilized in the current study followed this prior established methodology. Briefly, rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (40–45 mg kg−1 i.p.) and isoflurane gas (2–4%) was used as a supplement. Toe pinch and visual monitoring of respiration were used as indicators of adequate anesthesia. Under aseptic conditions, gas-sterilized, custom, monopolar intramuscular stimulating electrodes were implanted close to the motor points of flexor and extensor muscles of the hip (iliacus (IL) and biceps femoralis anterior head (BFh), respectively) of the iSCITNS rats. The choice of the muscles was guided by their contributions to joint movements during locomotion.

The stimulating electrode assembly was custom made from Teflon-coated stainless steel coiled lead wire (Cooner Wire, pn#AS632) with a 1–2 mm bare tip and a nylon suture connected near the bare tip. 1.5–2 mm circular retaining disks were threaded through the nylon sutures for anchoring the electrode to the muscles and in-line connectors soldered on the free lead end of the electrode wire. The helical coil provided stress relief and the retaining disks helped promote implant stability. Head connectors were fashioned by securing a custom-made female electrical connector with wire leads (Omnetics, Inc.) to the end of a polyethylene 1 ml syringe plunger using dental cement. The head connector was adhered to the skull between the lamboidal and coronal sutures and on either side of the sagittal suture using stainless steel screws and dental cement. The bundle of lead wires from the head connector was routed subcutaneously to the back of the animal through an incision in the lumbar region. A 1 cm circular ground connector made from 0.003″ stainless steel shim stock was sutured to the muscles on the back. Incisions were also made in the dorsal and ventral aspects of the hindlimbs to gain access to the BFh and IL muscles, respectively. The stimulating electrodes were implanted at the motor points in these muscles and their lead wires routed subcutaneously to the incision on the back where they and the ground connector lead were connected to the leads from the head connector (figure 1). The inline connections were ensheathed in 2 mm silicone tubing and the ends of the tubing were sealed with silicone adhesive. All materials were tunneled subcutaneously thereby reducing the possibility of infection. To test for proper implant placement, twitch threshold currents (minimum current required to elicit visible muscle activation) were obtained using a hand-operated stimulator (200 μs cathodic pulse bursts, 1 Hz). Electrodes were considered to have good placement at the muscle motor point when minimum pulse amplitude was attained. The average twitch threshold for the electrodes implanted was 0.31 ± 0.18 mA.

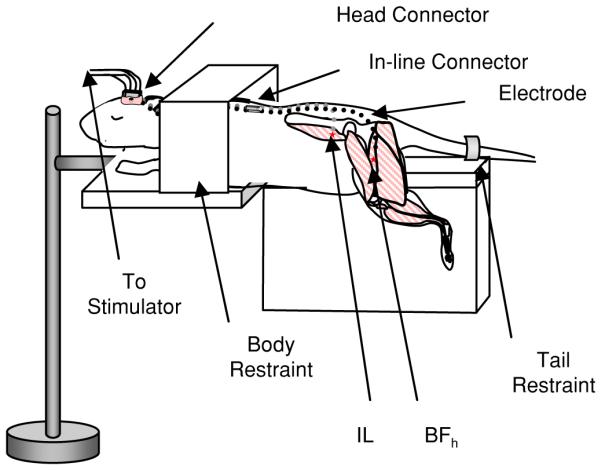

Figure 1.

NMES therapy paradigm experimental setup. Awake rats were restrained but hindlimbs were allowed to move freely. Electrodes were implanted into the biceps femoralis anterior head (BFh) and iliacus (IL), positioned at the motor points for those muscles.

During the same surgical session, the spinal cord at thoracic level T9 was exposed by dorsal laminectomy of the T7 and T8 vertebrae. An incomplete spinal contusion injury was performed at the T9 spinal level using standardized force application (Infinite Horizon Impactor, 156 ± 9.52 Kdyne, mean ± 1SD). The injury site was rinsed with an isotonic saline solution and absorbable 5-O sutures were used to suture musculature surrounding the injury site. The outer skin incision was closed with surgical staples, which were removed 7 days post-surgery. Rodents belonging to the non-therapy injury group only underwent contusion injury. Animals were allowed to recover on heating pads and body core temperature monitored until awake. All iSCI animals received daily doses of cefazolin antibiotic (33.3 mg kg−1 s.c.) and buprenorphine analgesic (0.02–0.05 mg kg−1 s.c.) for the first 7 days post-injury. Bladders were expressed twice daily for the duration of the study. Regular weight checks and urinalysis were also performed and if necessary supplemental Nutrical™for weight maintenance or antibiotic regimen for bladder infection treatment utilized.

2.3. NMES therapy

Starting on day 7 post-injury, rats assigned to the iSCITNS group received electrical stimulation therapy for 15 min/day, 5 days/week until 14 days post-injury. The introduction of iSCITNS 1 week after injury allowed early intervention of therapy. The iSCINT group received no stimulation. On day 7 and day 14, rats from both groups walked on a treadmill at the fastest speed they were able, not to exceed 21 m min−1.

To perform NMES therapy, awake animals were placed on a platform such that the head, forelimbs and midline of the torso were supported. The platform was designed to restrain excessive movement of the head and forelimbs, while the unloaded hindlimbs were allowed to move freely (figure 1). The animal’s head connector was engaged with a male connector (Omnetics, Inc.). Electrical stimulation of the hip flexor and extensor muscles was administered to attain hip flexion and extension. The goal of NMES was to obtain muscle contraction in the correct sequence and with sufficient strength such as to simulate periodic reciprocal hip flexion and extension of the left and right hindlimbs as seen during walking. Hip flexion/extension alone is incapable of simulating normal gait; it does however recruit the muscles most heavily involved in locomotion.

A computer-controlled stimulator (FNS16-CWE, Inc.) provided cyclic trains of electrically isolated biphasic (cathodic first) current pulses at 75 Hz (pulse width of 40 μs/phase and pulse amplitude current at 1.5× twitch threshold amplitude at the 40 μs/phase pulse width) repeated every 0.5 s for a total duration of 15 min. Twitch threshold is defined here as the minimum current required to elicit visible muscle twitch and was determined individually per electrode prior to a NMES session. The fixed pattern of stimulation was applied to induce muscle activation in left–right hindlimbs in reciprocal order such that initiation of left hip flexion occurred 0.25 s after initiation of right hip flexion. This resulted in flexion on one side overlapping with extension on the contralateral side as it occurs during walking in rodents [20]. The duration of the stimulation burst during each cycle of stimulation for each muscle was chosen to match the EMG activity we have previously recorded from these muscles during treadmill walking by intact, adult, female Long Evans rats [20]. These durations were 130 ms for the IL for hip flexion and 200 ms for the BFh for hip extension. The choice of stimulation parameters was guided by earlier studies [15], such that fused muscle contractions with sufficient hip joint torque and joint angle excursion occurred at initiation of NMES. Lower frequencies (50 Hz or less) do not yield fused contractions in the fast twitch muscles of Long Evans rodents [15].

To analyze the range of movement produced by NMES of the unloaded hindlimbs, 3D kinematic analysis was performed during the initial NMES session based on motion capture methods previously described by Thota et al [20]. Briefly, for each hindlimb, 2 mm reflective marker cones made from retro-reflective tape (3M) were carefully placed on the bony protrusions of the pelvis (anterior rim), hip (head of the greater trochanter) and knee (lateral head of femoral condyle). During NMES, the Peak Motus® motion analysis system (Vicon Peak, Lake Forest, CA) with an array of four CCD video cameras with infrared light source was used to capture the video of the hindlimb movements at 60 frames s−1 from a 360°field of view. Calibration of 3D space was performed using a custom rectangular calibration cube. Peak Motus® software was used to compile the video and construct a computer model based on the marker locations. The range of movement (ROM°) of the hip joint was calculated as the difference between the maximum hip angle during extension and the minimum hip angle during flexion. The average range of movement was calculated from four consecutive cycles per animal. These data were compared with the range of motion of the hip angle for intact non-injured rats walking on a treadmill.

2.4. Assessment of locomotor coordination recovery

2.4.1. Limb coordination during treadmill walking using joint angle kinematic analysis.

3D kinematic measures during treadmill walking were used to characterize intralimb and interlimb coordination [20, 22]. The analysis provided joint angle trajectories during the stance and swing phases, as well as touchdown and lift-off events during multiple gait cycles. The trajectories provide continuous measures of intra- and interlimb joint coordination, while the footfall patterns provide information on quadruped gait coordination on a cycle-by-cycle basis. These measures were compared amongst the injured therapy, injured non-therapy and intact rats. Prior to surgery, all rats were trained to walk on a single lane treadmill (Columbus Instrument, Inc.) 15 min/day for 4 days and given a fruit loop reward. 3D kinematic analysis of treadmill walking gait was performed once on all intact rats after these 4 days of walking training. The injured rodents did not perform any treadmill walking post-surgery prior to data collection. Kinematic gait analysis was performed on the iSCI rats on days 7 and 14 post-injury.

As described in detail by Thota et al [20], reflective markers were affixed to the bony protrusions of the pelvis, hips, knees, ankles, shoulders, elbows and wrists as well as the fifth metatarsal of the hindlimb feet and the treadmill belt, and tracked during treadmill walking using a Peak Motus® video-based motion analysis system as described above. In each session, the animal began walking at a treadmill speed of 2 m min−1. The speed was increased at approximately 1 m min−1 every 10 s in order to reach the target speed of 21 m min−1 or the speed at which the animal was able to walk comfortably at a constant pace without sliding on the treadmill in the middle of the lane. Partial body weight support was provided as necessary to the iSCI rats on day 7 to facilitate stepping. Treadmill walking sessions did not exceed 5 min and were long enough to obtain a minimum of five consecutive gait cycles. The markers were tracked automatically offline and corrections performed manually. Joint angle data imported into Matlab® (Mathworks, Natick, MA) were analyzed using custom analysis software [20].

2.4.2. Intralimb and interlimb joint angle coordination

Angular trajectories for the hip, knee, ankle, shoulder and elbow joints were obtained, and average joint angle trajectories determined for each animal by averaging up to 13 cycles (normalized to 100%, represented by 201 sample points). Limb lift-off and touchdown were defined as the first video frame in which toe contact with the surface is clearly visualized as ceasing and initiating, respectively. From these angular data, maximum extension during stance (STMaxE°), maximum flexion during swing (SWmaxF°), range of movement (SROM° = STMaxE° − SWmaxF°), joint angle at limb lift-off (LOVal°), and joint angle at limb touchdown (TDVal°) were determined.

Joint angle–angle plots between the knee and hip (KH), ankle and knee (AK), ankle and hip (AH) and elbow and shoulder (ES) joint angles were used for qualitative assessment of intralimb coordination. Interlimb coordination was also qualitatively assessed using plots for the left hip and right hip (LHRH), left knee and right knee (LKRK), left ankle and right ankle (LARA), left shoulder and right shoulder (LSRS) and left elbow and right elbow (LERE) joint angles. For each rat an average joint angle trajectory was obtained by averaging five gait cycles (normalized to 100%).

Left–right symmetry during gait was quantitatively analyzed using the interlimb angle–angle plots. The predicted value of hindlimb–hindlimb phase is approximately 0.5; hence, the angular trajectories of the right hindlimb should be roughly equivalent to the angular trajectories of the left hindlimb half a cycle later. This phenomenon can be visualized through the symmetric nature of interlimb angle–angle plots about the line y = x (figure 6). Since gait cycle length is normalized to 201 sample points, a right hip joint angle at any given point within a cycle, i, (θ RHi) can be used to predict the left hip joint angle at i + 101 (θ LHi +101) for all points in the data set (the first 100 points from the first cycle of the right joint and the last 100 points from the last cycle of the left joint are discarded). If the remaining corresponding points are plotted on interlimb angle–angle plots, they tend to cluster adjacent to the line y = x. The difference between the points and the line can then be calculated to find symmetry error, and root mean square (RMS) error can be calculated to characterize the entire normalized data by a symmetry index as

| (1) |

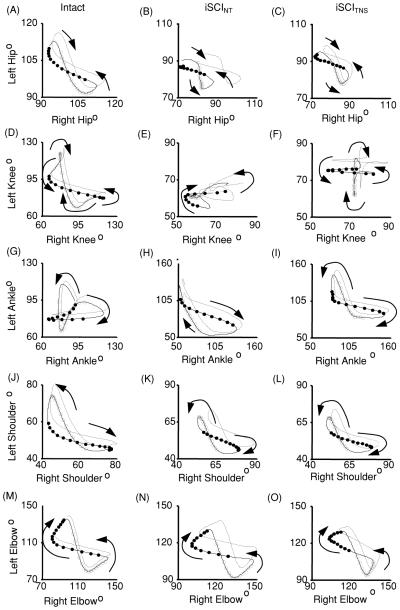

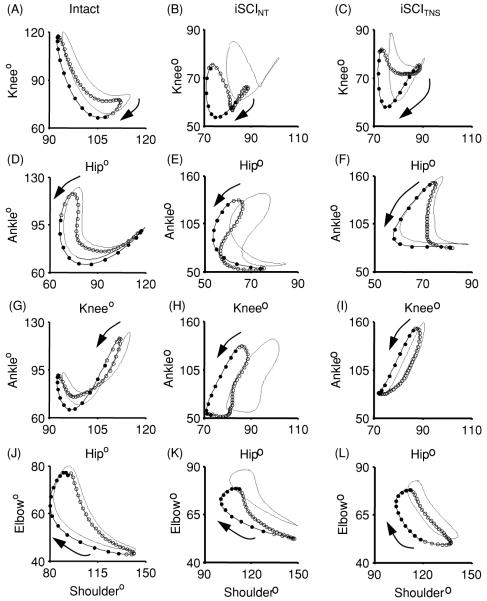

Figure 6.

Group average contralateral interlimb coordination for rats with no injury (Intact) and injured rats receiving no therapy (iSCINT) or receiving NMES therapy (iSCITNS) at 14 days post-injury. Angle–angle plots show coordination between contralateral hips (A–C), knees (D–F), ankles (G–I), shoulders (J–L), and elbows (M–O). Dark lines depict averages while the dotted lines represent the standard error of the means. Averaged traces indicate the swing phase of the left limb (open circles) and the swing phase of the right limb (filled circles). Each circle is separated by 8.33 ms. Arrows indicate the direction of the curves over time.

2.4.3. Interlimb gait coordination from foot fall patterns

Quantitative assessment of interlimb gait coordination was done to determine consistency of 1:1 correspondence between forelimb cycles and hindlimb cycles and between left and right hindlimbs, and to establish the relative phase of each limb touchdown with respect to another within a gait cycle. If the time points of right hindlimb touchdown are defined as τ rhi , i = 0, 1, 2, … , N, and the time points of ipsilateral forelimb touchdown are defined as τ rfk , k = 0, 1, 2 … , M, then the phase of the kth cycle of the right forelimb with respect to the right hindlimb is calculated as [20, 23]

| (2) |

The phase varies between 0 and 1 and is defined at discrete moments of time. A phase value of 0 or 1 indicates two touchdown events being completely in-phase while a value of 0.5 indicates the events being completely out-of-phase. Intact rats have a 1:1 correspondence between ipsilateral forelimb–hindlimb touchdowns. In injured animals, multiple ipsilateral forelimb touchdowns or no forelimb touchdowns can exist per hindlimb cycle.

The same equation can be used to determine the phase relationship between the right and left hindlimb touchdown events (ΦRHLH). While intact rats have a 1:1 correspondence between the left and right hindlimb touchdowns, in injured rats multiple left (right) hindlimb touchdowns or no touchdowns can occur per right (left) hindlimb cycle. In each animal, after approximately 1 min of treadmill walking, a fixed time period of 30 s, regardless of the number of gait cycles incurred during that time, was analyzed for assessing consistency of normal 1:1 interlimb coordination and calculating the relative phase values. To assess the consistency of 1:1 hindlimb left–right interlimb coordination, the proportion of hindlimb gait cycles with only one phase value per cycle was calculated by dividing the number of hindlimb cycles displaying 1:1 interlimb coordination by the total number of hindlimb cycles recorded. Only gait cycles with 1:1 coordination during the 30 s were used for calculating the phase values as per equation (2) above. Similar calculations were made to assess consistency of ipsilateral 1:1 forelimb–hindlimb coordination.

2.4.4. Overground walking locomotor score

The assessment of generalized locomotor recovery of overground walking after iSCI was performed using the Basso, Beattie and Bresnehan (BBB) locomotor rating scale [24]. The BBB forced choice 21-point open-field locomotor assessment scale has been utilized extensively for observational analysis of single joint movement, dorsal versus plantar stepping, weight bearing and hindlimb–forelimb coordination. However, hindlimb–hindlimb coordination and intralimb coordination do not affect the BBB rating unless the gait pattern is near normal (i.e. these are the implicit components of quadruped coordinated gait for ratings of 20 or 21 on the 21-point BBB scale). Rats were allowed to walk freely over a 4 ft × 4 ft flat level area for 4 min and the locomotor ability scored by two observers on days 1–6 following injury, and again on day 14. The severity of the iSCI produced and consequent time course of recovery as assessed by the BBB score have previously been shown to be related to the impactor force [14].

2.5. Statistical analysis

Stability of the electrodes implanted for NMES was assessed by performing a two-way repeated measures ANOVA of the recorded twitch threshold values. Independent variables were time and implantation site. Data were blocked by electrode—each electrode served as one data block. Stability during the NMES therapy period was assessed by normalizing twitch threshold currents (dependent variable) to those obtained at day 7. Ability of the stimulation to elicit sufficient angular movement was assessed by performing a one-way repeated measures ANOVA of the recorded range of movement of the hip joint (dependent variable) during the first NMES session. The independent variable here was time, and each animal served as one data block.

To analyze the joint-angle kinematics during walking on day 14 post-injury, a one-way ANOVA was performed for each of the hip, knee, ankle, shoulder and elbow-angle measures. In each case, the dependent variables were SWMaxF°, STMaxE°, SROM°, LOVal° and TDVal°. The independent variable was group (iSCITNS versus iSCINT versus Intact). Multiple comparisons were made with a Tukey test. Symmetry error was also analyzed using a one-way ANOVA, with the dependent variables being SYM E values for the hip, knee and ankle, and independent variable being group. An F-test was used to compare the variance in the proportion of gait cycles with 1:1 interlimb coordination between the two injury groups. A one-way ANOVA was used to compare the means of the phase values obtained from the sub-set of gait cycles with 1:1 coordination across the three groups, and variability in the phase values was assessed by a one-way ANOVA on the standard deviation of the phase values obtained for each rat in each of the groups. To analyze BBB scores, a two-way repeated measures ANOVA was performed with the independent variables being time post-injury and group (iSCITNS versus iSCINT). All results were considered significant for p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Electrode stability

The threshold current to elicit a muscle twitch increased from the day of the implant surgery to day 7 post-implant for all electrodes. Two electrodes implanted in the BFh were found to be non-functional (i.e. did not produce a muscle twitch at any current on day 7). The mean threshold currents for the functional BFh group implants were significantly lower than those in the IL group (p < 0.0001). One of the non-functional BFh electrodes was re-implanted and re-tested 10 days post-injury at which time it was functional and was used subsequently for 4 days of NMES therapy. From day 7 to 14 post-injury, three more electrodes became unstable. One electrode in the IL became non-functional after 3 days of therapy and one became non-functional after 4 days of therapy. One BFh electrode remained functional but had very high twitch threshold values (exceeding 200% of that at day 7). The remaining 19 out of 24 electrodes exhibited a twitch threshold current of 94.36% ± 17.63% of the original value on the final day of NMES. A two-way repeated measures ANOVA indicated that all other electrodes (BFh (n = 9) and IL (n = 10)) remained stable with no significant change in normalized twitch threshold over time (p = 0.65). Thus, 20/24 of the electrodes (one with high threshold) remained viable for the entire time.

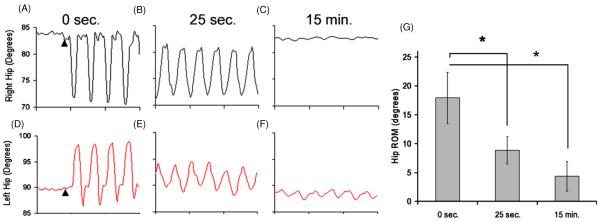

3.2. Hip joint angle movement during NMES

The ability of the stimulation to elicit muscle contractions is dependent on the proximity of the electrode to the motor point and the stimulation parameters used. For each animal, kinematic analysis of data captured during the first NMES therapy session (7 days post-injury) was used to ascertain the range of joint movement produced by the stimulation. Figures 2(A) and (D) depict typical joint angle trajectories obtained from the right and left hip joints during one stimulation trial at the beginning of the stimulation period. Figures 2(B) and (E) depict the same joint angle trajectories 25 s later; figures 2(C) and (F) depict those 15 min later. The data show successful implementation of NMES to produce periodic alternating hip flexion and extension. Figure 2(G) shows summary data for all hindlimbs with two functional electrodes implanted on the first day of stimulation (n = 10). During the first ten cycles of stimulation, the average hip ROM° observed was 17.9° ± 4.5°. After 25 s of NMES, the range decayed to 8.8° ± 2.4°, representing a significant decrease (p < 0.0001). Average hip ROM° remains greater than zero until the completion of the NMES session; however, significant decay continues (ROM° at 15 min = 4.0° ± 2.7°, p < 0.0001).

Figure 2.

Hip angles during NMES therapy. Panels A, D depict the right and left hip joints, respectively, at the beginning of the stimulation period. Arrowheads indicate start of stimulation. Panels B, E depict the same joints 25 s later, and panels C, F show them at the end of a NMES therapy session. Sustained periodic alternating hip movement can be observed. Panel E shows that there was a significant decay in joint angular excursion during NMES therapy after 25 s (∗ signifies p < 0.01). Panel G shows that the hip range of motion (ROM°, averaged from four cycles per animal at each time point (mean ± SEM)) decay continues until the end of stimulation at 15 min.

3.3. Recovery of locomotor coordination

3.3.1. Intralimb and interlimb joint angle coordination

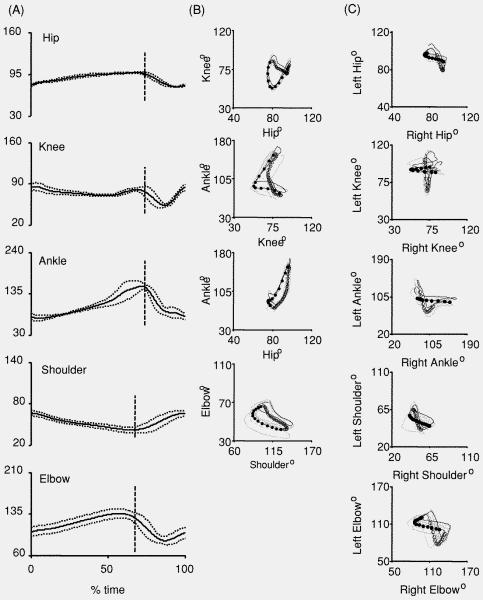

Kinematic analysis during treadmill walking was used to quantitatively assess coordination. Prior to NMES therapy on day 7 post-injury, three of six animals in the iSCITNS group and two of four animals in the iSCINT group displayed no hindlimb stepping. The animals which did display hindlimb stepping did so infrequently. Therefore, reliable quantitative 3D kinematic analysis of interlimb coordination could not be conducted on day 7. Analyses of data from day 14 when all animals were able to step on the treadmill without body-weight support are reported. Figure 3(A) shows the average joint angle trajectories for a representative injured animal receiving NMES therapy (normalized to 100% per gait cycle, touchdown to touchdown). The plot shows the average (solid line) ±1SD (dashed line) angle trajectory of the hip, knee, ankle, shoulder and elbow. The vertical dotted line represents limb lift-off. Here, an upward excursion of a plot indicates joint extension and a downward excursion represents joint flexion. Figures 3(B) and (C) show angle–angle plots generated from the representative animal, illustrating intralimb and interlimb coordination, respectively. Each plot shows all of the gait cycle trajectories and the averaged trajectory. The stance phase is indicated by open circles and the swing phase by filled circles in all the plots.

Figure 3.

Characteristic joint angle data for an iSCI NMES therapy rat at 14 days post-injury. (A) Normalized joint angle trajectories for the hip, knee, ankle, shoulder, and elbow. Shown are the average (solid line) and standard deviation (dotted line). (B) Angle–angle plots showing intralimb coordination between the knee and hip, ankle and knee, ankle and hip, and elbow and shoulder. Averaged traces indicate the stance phase (open circles) and the swing phase (filled circles). (C) Angle–angle plots showing interlimb coordination between the left and right hip, knee, ankle, shoulder, and elbow. Angle–angle plots display the average (black line) and individual cycles (gray lines). Averaged traces indicate the swing phase of the left limb (open circles) and the swing phase of the right limb (filled circles). Each circle is separated by 8.33 ms.

When analyzing the joint angles recorded during treadmill walking, we assessed whether the kinematics of iSCITNS animals who had at least one unstable or non-functional electrode implanted were any different from those with all stable, functional electrodes. Data from rats with all ‘good’ electrodes (n = 3) were compared to those with at least one ‘bad’ electrode (n = 3). It was found that rats from the good (bad) group displayed ankle SWmaxF°, STMaxE°, SROM°, LOVal° and TDVal° angles of 73.7° ± 6.2° (67° ± 3.6°), 149.3° ± 8.5° (166.0° ± 3.6°), 75.6° ± 3.2° (98.5° ± 5.7°), 143.4° ± 11.5° (162.2° ± 4.6°) and 79.4° ± 6.0° (76.9° ± 6.0°), respectively. There were no differences identified to be statistically significant. Hence, the data for all iSCITNS rats (n = 6) were utilized and compared to those from iSCINT and intact rats.

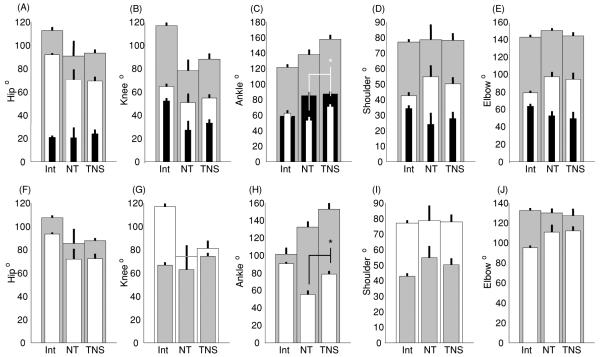

As illustrated in figure 4, there are essentially no differences in shoulder and elbow joint angle measures calculated for the three groups. Compared to intact rats, statistically significant differences were observed in some of the hindlimb joint angle measures for the injured rats. Thus, in the injured rats, there was less flexion at the hip and ankle joints during swing (SWmaxF°), and there was less extension of the hip and knee joints and over extension of the ankle joint during stance (STmaxE°). The values of joint angles at the hip at lift-off (LOVal°) and the values for the hip, knee and ankle joints at touchdown (TDVal°) were smaller for the injured rats. The ankle joint angle at lift-off for the injured animals was significantly larger. Although no statistically significant differences were observed in hip and knee joint angles in the two groups of injured rats, the NMES therapy rats showed reduced variance in the joint angles throughout the gait cycle. At the ankle joint, the NMES therapy rats had significantly reduced flexion during swing and much larger joint angle at touchdown compared to the non-therapy rats.

Figure 4.

Average joint angles during treadmill walking. Data are compared amongst three groups: intact (Int; n = 6), iSCI rats given NMES therapy (iSCITNS, n = 6) and iSCI rats with no therapy (iSCINT, n = 4) for the hip (A, F), knee (B, G), ankle (C, H), shoulder (D, I) and elbow (E, J) (mean ± SEM). Top row: maximum during stance (gray), minimum during swing (white), and the range of movement (black). Bottom row: joint angles at lift-off (gray) and touchdown (white). (∗ signifies p < 0.05 for post hoc multiple comparisons between the injured group of rats). See text for detailed comparisons of injury versus intact rats.

Figure 5 illustrates angle–angle plots showing qualitative relationships between joint angles for intact, iSCINT and iSCITNS animals. The plots show group average data (black line)±SEM (gray line). The stance phase is indicated by open circles and the swing phase by filled circles in all the plots. Intralimb angle–angle plots of the iSCITNS group, specifically the knee–hip (KH) and ankle–knee (AK) plots (figures 5(C), (F)), exhibit the crescent shape similar to that for intact rats (figures 5(A), (D)). The corresponding plots for the iSCINT group (figures 5(B), (E)) exhibit slightly different shapes [20]. On comparing figures 5(G)–(I), we observe that the ankle–hip (AH) plots for both the iSCINT and iSCITNS groups have positive slopes similar to those for the intact rats indicating in-phase coordination throughout the cycle; the ankle, however, has extensive plantar flexion in injured animals. In intact animals, the ankle joint flexed during both the swing and stance phases, which produced a distorted figure-of-eight pattern of the AH plot, and the overall extension of the ankle was less than that observed after injury. ES plots for both the iSCINT and iSCITNS groups (figures 5(K), (L)) display shapes that are similar to the intact rats (figure 5(J)). After iSCI, animals showed higher variability in joint angle coordination. Analysis of the variability within rats is presented below.

Figure 5.

Group average intralimb joint angle coordination for rats with no injury (Intact) and injured rats receiving no therapy (iSCINT) or receiving NMES therapy (iSCITNS) at 14 days post-injury. Angle–angle plots show coordination between ipsilateral knees and hips (A–C), ankles and knees (D–F), ankles and hips (G–I), and elbows and shoulders (J–L). Dark lines depict averages while the dotted lines represent the standard error of the means. Averaged traces indicate the stance phase (open circles) and the swing phase (filled circles). Each circle is separated by 8.33 ms. Arrows indicate the direction of changes in the curves over time.

There are even larger differences in interlimb coordination between the iSCINT and iSCITNS rats. Figure 6 illustrates the average interlimb joint angle–angle plots for the intact, iSCINT and iSCITNS groups. From this figure it is evident that the left hip–right hip (LHRH) plot of the iSCITNS group at 14 dpi (figure 6(C)) shows a similar size and shape to the corresponding plot of the iSCINT group (figure 6(B)). However, the corners of the iSCITNS group plot are rounded while those of the iSCINT group plot are sharp. Rounded corners indicate smooth interlimb coordination for part of the gait cycle, as seen in the plot for the intact rats (figure 6(A)).

The left knee–right knee (LKRK) plot of the iSCINT group (figure 6(E)) displays no real discernable pattern and has a large standard error, while that of the iSCITNS group (figure 6(F)) displays an easily recognizable cruciform pattern. The left ankle–right ankle (LARA) plots of the two experimental groups (figures 6(H), (I)) do appear similar; however, it is apparent that the iSCITNS group plot is more symmetric about a y = x diagonal. However, after iSCI neither of the groups show the butterfly pattern observed in intact rats (figure 6(G)). The interlimb angle–angle plots for the shoulder and elbow are similar in size, shape and variation (figures 6(K), (L), (N), (O)), and are similar to those for intact rats (figures 6(J), (M)).

As seen in the angle–angle plots (5–6 gait cycle average—thick lines; 1 SEM—dashed line) in figure 6, for intact animals the contours are symmetric about the diagonal reflecting the 180° out-of-phase left–right coordination. The shapes and symmetry of these contours are considerably altered after injury in the absence of NMES therapy. With therapy, even though impairments remain, the contours are more symmetric and closer in form to those of the intact animals.

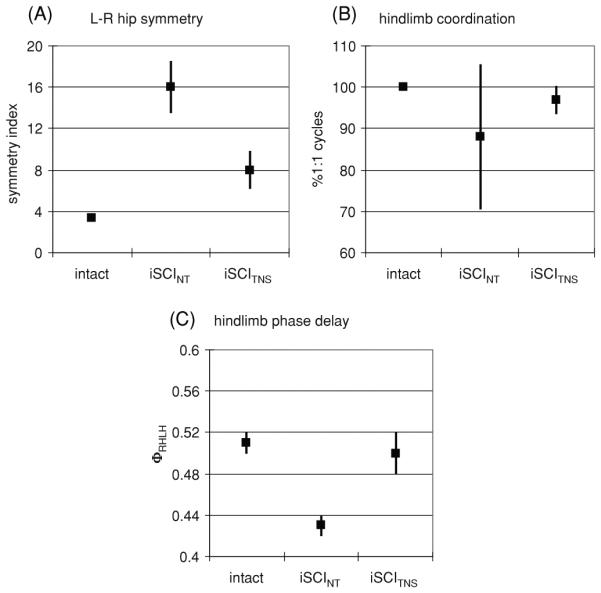

Quantitative assessment of the symmetry error indicated that the hip joint symmetry error was significantly lower in the iSCITNS rats receiving NMES therapy than the iSCINT rats not receiving therapy (8.0° ± 1.8° versus 16.7° ± 2.5°; p = 0.03). A similar trend of lower symmetry error was present for the knee (10.8° ± 1.2° versus 15.8° ± 2.7°) and ankle (18.3° ± 3.3° versus 21.5° ± 2.8°). For all three joints, the intact rats had a significantly higher symmetry and hence lower error (hip: 3.4° ± 0.3°, knee: 7.6° ± 1.3°, ankle: 10.2° ± 0.8°) than the injured rats (p < 0.05). Symmetry error (mean ± SEM) for the hip joints of all three groups is presented in figure 7(A).

Figure 7.

Interlimb coordination during treadmill walking for rats with no injury (Intact), injured rats receiving no therapy (iSCINT) and those receiving NMES therapy (iSCITNS). (A) left–right symmetry error at the hip, (B) % of gait cycles with 1:1 left–right hindlimb coordination, (C) relative phase delay between left and right hindlimb touchdown. All indices of interlimb coordination indicate significant impairment with injury. NMES therapy results in recovery of interlimb coordination.

3.3.2. Interlimb gait coordination

The consistency of interlimb coordination and the relative phase delays between left and right hindlimb touchdown was assessed. In intact rats, a 1:1 left–right and forelimb–hindlimb coordination was maintained for all (100%) of the gait cycles. In the injured animals, this 1:1 coordination was disrupted and multiple touchdown events occurred during several gait cycles. As illustrated in figure 7(B) (mean ± SEM), in the group of rats not receiving therapy only 88% ± 17.5% of gait cycles displaying 1:1 left–right hindlimb coordination. The group receiving NMES therapy showed considerable improvement with 97% ± 3.4% of gait cycles displaying 1:1 left–right hindlimb coordination. Thus, there was a significantly lower variability in achieving left–right 1:1 coordination in animals receiving the NMES therapy (p = 0.002). The impairment in 1:1 ipisilateral forelimb–hindlimb coordination was similar in the non-therapy and NMES therapy groups; 62% ± 22.4% and 56% ± 22.4% of the gait cycles showed 1:1 coordination, respectively.

The values of the phase delay between left–right hindlimb touchdowns and ipsilateral forelimb–hindlimb touchdown in those gait cycles in which a single-phase event occurred were also calculated. As illustrated in figure 7(C) (mean ± SEM), intact rats displayed left–right phase delays of 0.51 ± 0.01. The left–right phase values for the non-therapy rats (0.43 ± 0.04) tended to be lower than those receiving therapy (0.50 ± 0.02) and the intact rats (p = 0.07). The phase delays in rats receiving NMES therapy were similar to those in intact rats. The ipsilateral forelimb–hindlimb phase delays for both injury groups (0.60 ± 0.05 for iSCINT and 0.52 ± 0.08 for iSCITNS) were similar but significantly different from those of the intact animals of 0.84 ± 0.01, p < 0.002.

3.3.3. Overground walking locomotor score

The BBB score significantly improved in the first week following iSCI in both groups. It tended to be lower for the non-therapy rodents in the first week post-injury with the values on day 6 post-injury being 7.8 ± 3.3 and 10.5 ± 1.75 (mean ± SD) for the iSCITNS and iSCINT groups, respectively. However, the two groups converged by 14 days post-injury at which time the scores were 14.5 ± 3.1 and 14.5 ± 0.48 for the iSCITNS and iSCINT groups, respectively.

4. Discussion

This study is the first to establish the capability of using neuromuscular electrical stimulation based repetitive limb movement therapy in rodents with spinal contusion injury to promote recovery of interlimb coordination during locomotion. This experimental model provides a preparation that can be used to develop and test stimulation strategies for limb coordination and control and, more importantly, provides a preparation that can be used for long-term longitudinal studies to evaluate the efficacy of specific NMES therapies in a well-characterized and widely used model of spinal cord injury.

The therapeutic paradigm used in this study utilized NMES of a small set of muscles (2/side) to drive a simple movement pattern (reciprocal swinging legs) during a small number (5) of short sessions (15 min) distributed over several days (7). Other implementations of NMES therapy could provide a more intense intervention by stimulating more muscles, performing a more complex movement pattern (such as locomotion) or by increasing session duration, the total number of sessions or the duration of the intervention [16, 25]. The details of the intervention used in this study were selected to facilitate implementation of this initial investigation of NMES therapy in a rodent model while retaining some key features: sufficient contraction to induce movement, sufficient intensity to induce fatigue, a reciprocal movement pattern and a sufficient duration of intervention to allow some degree of recovery of voluntary motor function. The demonstrated effects of this ‘mild’ intervention, in particular the effects on interlimb coordination during locomotion, testify to the potential utility of NMES for neuromotor therapy. More intense forms of this intervention may provide further benefits. Future studies may provide information regarding the tradeoffs between complexity/cost and functional outcomes that will be useful in the clinical prescription of NMES therapy.

The results of this initial investigation of NMES therapy demonstrate that it can improve interlimb coordination during locomotion following spinal cord injury. Interlimb coordination requires bilateral activation of muscles acting at the hip joint in a reciprocal manner, which was the specific target of this implementation of NMES therapy. The calculation of symmetry error indicates significant improvement in left–right symmetry in these animals. Additionally, the injured rodents receiving therapy tended to more consistently display a high percentage of 1:1 coordinated steps than their non-therapy counterparts did, and they more consistently achieved proper hindlimb touchdown timing with respect to the other hindlimb. The selective improvement in hindlimb coordination observed in this study is consistent with results from previous studies in spinal cats in which improved motor function was related to the therapy that was administered (step or stand) [19]. It is possible that NMES therapy, that also targets other components of locomotion, such as intralimb coordination, movement scaling, body weight support or stride length, may provide additional benefits that would result in significant improvements in generalized locomotor assessments such as the BBB.

These data demonstrate a clear and favorable influence of NMES therapy on the processes that bring about neuroplasticity in the circuits involved in interlimb coordination, which is a process believed to be mediated in the spinal cord and/or through the brain–spinal interaction. These results, therefore, suggest that NMES techniques could provide an effective therapeutic tool for neuromotor treatment following iSCI. In the sections that follow, we discuss different aspects of the implementation of the NMES system and the implications for its promise as a therapeutic tool.

4.1. Kinematic evidence for locomotor recovery

Kinematic measurements, such as used in this study, are necessary to assess coordination in a detailed manner [26]. The kinematic assessment of treadmill gait indicates that NMES can influence recovery of locomotion. Intralimb coordination, as interpreted from angle–angle plots, moves more toward ‘normal’ in iSCITNS rats. The KH and AK angle–angle plots show a crescent shape in intact animals. Similar plots from the therapy group show a more pronounced crescent shape than those from the non-therapy group, suggesting improved coordinated intralimb movement in the group receiving NMES therapy. Improved intralimb coordination post-functional electrical stimulation assisted gait training has also been shown to occur in human subjects following SCI [10].

Comparison of the angle–angle plots of analogous joints of the two hindlimbs indicates that interlimb coordination in the rodents receiving NMES therapy also appears more like that in intact animals. While the left hip–right hip angle–angle plots (figures 6(A)–(C)) are similar in size and shape for the therapy and non-therapy groups, the plots for the therapy group show rounded corners, indicating smoother transitions from one step to the next [27]. All of the angle–angle plots tend to indicate better symmetry in the iSCITNS group. In the left knee–right knee angle–angle plots (figures 6(D)–(F)), a difference between the therapy and non-therapy groups is apparent. While no discernable pattern exists for the contours of the non-therapy group, the contours for the therapy group animals show a regular, recognizable pattern of interlimb coordination. This pattern is different from that observed in intact animals, but has considerably improved symmetry and regularity when compared to the non-therapy group. The predominant pattern that consists of mostly vertical and horizontal segments indicates that knee movement occurs one leg at a time. While the relative lack of diagonal and curved lines may indicate compromised joint coordination, when compared to the non-therapy group, it represents better joint angle integrity from phase to phase. Such integrity suggests that gross limb movement during stance is achieved through precise hip movement rather than overcompensation during gait from other joints. A significantly lower Sym E at the hip in this group (figure 7) further supports the occurrence of more precise hip movement and increased degree of control over the hip joint in the rats receiving therapy. In the animals in the NMES therapy group, a higher proportion of gait cycles exhibited 1:1 left–right hindlimb coordination, and the 1:1 coordination occurred more consistently, therefore providing further indication of improved interlimb control during locomotion after therapy.

4.2. Overground locomotor score to assess locomotor recovery

The BBB scores for both the injury groups do follow the profile expected under moderate levels of contusion injury [14]; at the final measurement point, both groups had average BBB scores of 14.5. In the first week post-injury, the BBB scores for iSCITNS rats were consistently lower than iSCINT rats, but this difference was not statistically significant. The iSCITNS rats had undergone intramuscular implantation whereas their iSCINT counterparts had not. The slight discrepancy in locomotor ability during this first week post-injury may reflect hindlimb muscle and wound healing and not necessarily a difference in neural function.

Although the quantitative analysis of interlimb coordination and symmetry of joint angle movement demonstrated a significant effect of NMES therapy, these changes were not reflected in the more general measure of overground walking using the BBB score. This is not surprising, because the BBB score does not take into account specific information on joint angle kinematics and hindlimb–hindlimb coordination. Each score also reflects multiple indicators, e.g. a score of 12 indicates frequent to consistent weight supported plantar steps and occasional forelimb–hindlimb coordination. Scores of 14–19 indicate that the animal can have consistent weight supported steps and have forelimb–hindlimb coordination. Improved scoring in this range is related to paw usage during locomotion. Only scores of 20 and 21 indicate coordinated overall gait patterns. Since the final BBB scores obtained by either group were approximately equal to 14, they had not reached a level at which improved hindlimb coordination would have an effect on the BBB score.

4.3. Electrode stability

A critical consideration in the design of a therapy that utilizes implanted electrodes is the long-term stability of the neural–electrode interface. It has been suggested that rehabilitative training in humans initiated soon after incomplete SCI results in improved functional outcomes [28, 29]. The early weeks post-injury are also the time period during which the endogenous nervous system has reparative molecular changes [30]. With these considerations in mind, we utilized a contusion injury rodent model and early intervention of NMES 1 week post-injury. In paraplegic rodents, intramuscular NMES electrodes were stabilized by 2–3 weeks post-implantation [17, 21]. In this study, the electrodes were implanted in contused animals for only one week prior to initiation of NMES. Contused rodents are nearly sedentary soon after injury, but their voluntary movements increase in intensity and frequency over the first week. This type of activity can affect electrode stability, as reflected by the higher twitch threshold currents that were recorded seven days post implantation. However, between 7 and 14 days post implantation, twitch threshold currents effectively stabilize. Thus, commencing NMES-based movement therapy 1 week after injury is viable. The primary factor in implant instability appears to be movement, therefore hindlimb immobilization could have been utilized during the first 7 days. However, in a clinical environment this type of immobilization would be contraindicated due to concerns regarding neuromotor, vascular and dermatological health. Similar concerns exist for the chronic rodent injury model. For this reason, we chose not to immobilize the rodent limbs even though it may have improved the stability of the neural–electrode interface.

We observed a systematic difference between the twitch threshold values of iliacus and biceps femoralis muscles, therefore indicating that the surgical placement of electrodes into the iliacus was not as precise as the placement into biceps femoralis. The iliacus lies much deeper, covered by other musculature and surrounded by bone, when compared to the biceps femoralis and hence the surgical approach to the motor point presents more challenges. These factors may have contributed to the quality of surgical placement. Additionally, during walking the rodent hip flexor undergoes significant movement, which may also have affected electrode stability.

4.4. Possible mechanisms of recovery

Use-dependent learning in the incomplete injured spinal cord can occur because of synaptic plasticity [1, 4] that ultimately results in improved voluntary locomotion. Up-regulation of TrkB receptors and BDNF has been implicated in spinal learning and hence mechanisms that lead to up-regulation of BDNF in the lumbar motoneurons are likely to influence locomotor recovery [19]. This up-regulation is not related to repair of the damaged area by regenerating neurons. There are three general mechanisms through which electrical stimulation therapy could induce synaptic plasticity to improve the pattern of recovery: movement-induced sensory activation, movement-induced exercise response and direct stimulation of afferents. Each of these is briefly discussed below.

The first putative mechanism is that electrical stimulation of motor fibers generates movement that produces a coordinated pattern of sensory activity, which is conducive to sensorimotor reorganization. Hip stretch proprioceptors, ankle load receptors, muscle spindle afferents and plantar cutaneous afferents are all considered to play an important role in determining hindlimb movement coordination and play an important role in the recovery of locomotion after spinal cord injury [31–37]. In the current study, NMES therapy was applied to the unloaded hindlimb and therefore did not activate plantar cutaneous receptors and did not activate sensors of limb loading. Hence, if the observed plasticity was due to movement-induced sensory activation, it is most likely due to activation of hip proprioceptors and/or activation of spindle afferents in stimulated muscles. The H-reflex, which affects contralateral limb coordination via reciprocal Ia inhibition [38] and is impaired after SCI in rodents [39] and humans [36], can be favorably altered by therapy [39]. In the animals in the NMES therapy group, a higher proportion of gait cycles exhibited 1:1 left–right hindlimb coordination, and the 1:1 coordination occurred more consistently. The observed improvements in interlimb coordination in the NMES therapy group may reflect modification of the H-reflex by the intervention.

The second putative mechanism is that electrical stimulation of motor fibers strengthens muscles in a manner that facilitates voluntary usage and induces a generalized exercise response that is conducive to plasticity. Exercise induced by electrical stimulation of muscles can strengthen muscles or prevent disuse atrophy [3, 5]. Exercise can also up-regulate plasticity-related neurotrophins such as BDNF in the muscle [40], from where they can be retrogradely transported to the spinal cord. Neurotrophins in the spinal cord or their receptors can also be upregulated in a manner that is activity dependent and activity specific [41, 42]. Thus, patterned NMES therapy may have had an exercise related activity-specific effect on neuromuscular plasticity and thereby influenced sensorimotor reorganization supportive of locomotor control.

The third putative mechanism is that direct electrical stimulation of afferents in a repetitive manner induces sensorimotor reorganization and/or promotes up-regulation of neurotrophic factors resulting in sensorimotor reorganization [12]. In rodents, tonic stimulation of peripheral nerves has been shown to promote up-regulation of plasticity-associated genes, including BDNF [43–45]. In the current study, phasic electrical activation that targeted motoneurons is likely to have directly activated sensory fibers in the vicinity of the electrode. Thus, direct activation of sensory fibers (or motor fibers) may have triggered molecular mechanisms that underlie synaptic plasticity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health R01-HD40335.

References

- [1].Lynskey JV, Belanger A, Jung R. Activity dependent plasticity in spinal cord injury. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2008;45:229–40. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2007.03.0047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ramer LM, Ramer MS, Steeves JD. Setting the stage for functional repair of spinal cord injuries: a cast of thousands. Spinal Cord. 2005;43:134–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ragnarsson KT. Functional electrical stimulation after spinal cord injury: current use, therapeutic effects and future directions. Spinal Cord. 2008;46:255–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3102091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bradbury EJ, McMahon SB. Spinal cord repair strategies: why do they work? Nat. Rev. 2006;7:644–53. doi: 10.1038/nrn1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Martin TP, Stein RB, Hoeppner PH, Reid DC. Influence of electrical stimulation on the morphological and metabolic properties of paralyzed muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 1992;72:1401–6. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.4.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Belanger M, Stein RB, Wheeler GD, Gordon T, Leduc B. Electrical stimulation: can it increase muscle strength and reverse osteopenia in spinal cord injured individuals? Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2000;81:1090–8. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2000.7170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Mohr T, Podenphant J, Biering-Sorensen F, Galbo H, Thamsborg G. Increased bone mineral density after prolonged electrically induced cycle training of paralyzed limbs in spinal cord injured man. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1997;61:22–5. doi: 10.1007/s002239900286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Stein RB, Chong SL, James KB, Kido A, Bell GJ, Tubman LA, Belanger M. Electrical stimulation for therapy and mobility after spinal cord injury. Prog. Brain Res. 2002;137:27–34. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(02)37005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Barbeau H, Ladouceur M, Mirbagheri MM, Kearney RE. The effect of locomotor training combined with functional electrical stimulation in chronic spinal cord injured subjects: walking and reflex studies. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 2002;40:274–91. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00210-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Field-Fote EC, Tepavac D. Improved intralimb coordination in people with incomplete spinal cord injury following training with body weight support and electrical stimulation. Phys. Ther. 2002;82:707–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Postans NJ, Hasler JP, Granat MH, Maxwell DJ. Functional electric stimulation to augment partial weight-bearing supported treadmill training for patients with acute incomplete spinal cord injury: a pilot study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2004;85:604–10. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.08.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dobkin BH. Do electrically stimulated sensory inputs and movements lead to long-term plasticity and rehabilitation gains? Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2003;16:685–91. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000102622.38669.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Metz GA, Curt A, van de Meent H, Klusman I, Schwab ME, Dietz V. Validation of the weight-drop contusion model in rats: a comparative study of human spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2000;17:1–17. doi: 10.1089/neu.2000.17.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Scheff SW, Rabchevsky AG, Fugaccia I, Main JA, Lumpp JE., Jr Experimental modeling of spinal cord injury: characterization of a force-defined injury device. J. Neurotrauma. 2003;20:179–93. doi: 10.1089/08977150360547099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ichihara K, Venkatasubramanian G, Abbas JJ, Jung R. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation of the hindlimb muscles for movement therapy in a rodent model. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2009;176:213–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kim S-J, Fairchild MD, Iarkov A, Abbas JJ, Jung R. Adaptive control of movement for neuromuscular stimulation-assisted therapy in a rodent model. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2009;56:452–61. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2008.2008193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Jung R, Ichihara K, Venkatasubramanian G, Abbas JJ. Chronic neuromuscular electrical stimulation of paralyzed hindlimbs in a rodent model. J Neurosci. Methods. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gazula VR, Roberts M, Luzzio C, Jawad AF, Kalb RG. Effects of limb exercise after spinal cord injury on motor neuron dendrite structure. J. Comp. Neurol. 2004;476:130–45. doi: 10.1002/cne.20204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Edgerton VR, et al. Training locomotor networks. Brain Res. Rev. 2008;57:241–54. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Thota AK, Watson SC, Knapp E, Thompson B, Jung R. Neuromechanical control of locomotion in the rat. J. Neurotrauma. 2005;22:442–65. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Venkatasubramanian G, Ichihara K, Kanchiku M, Mukherjee M, Belanger A, Abbas JJ, Jung R. Abstract: functional neuromuscular stimulation in a paraplegic rodent model: electrode design, implantation and assessment. J. Neurotrauma. 2004;21 [Google Scholar]

- [22].Thota AK, Carlson S, Jung R. Recovery of locomotor function after treadmill training of incomplete spinal cord injured rats. Biomed. Sci. Instrum. 2001;37:63–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Jung R, Brauer EJ, Abbas JJ. Real-time interaction between a neuromorphic electronic circuit and the spinal cord. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2001;9:319–26. doi: 10.1109/7333.948461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Basso DM, Beattie MS, Bresnahan JC. A sensitive and reliable locomotor rating scale for open field testing in rats. J. Neurotrauma. 1995;12:1–21. doi: 10.1089/neu.1995.12.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Maladen RD, Perumal R, Wexler AS, Binder-Macleod SA. Effects of activation pattern on nonisometric human skeletal muscle performance. J. Appl. Physiol. 2007;102:1985–91. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00729.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Metz GA, Merkler D, Dietz V, Schwab ME, Fouad K. Efficient testing of motor function in spinal cord injured rats. Brain Res. 2000;883:165–77. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02778-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Winstein CJ, Garfinkel A. Qualitative dynamics of disordered human locomotion: a preliminary investigation. J. Mot. Behav. 1989;21:373–91. doi: 10.1080/00222895.1989.10735490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Norrie BA, Nevett-Duchcherer JM, Gorassini MA. Reduced functional recovery by delaying motor training after spinal cord injury. J. Neurophysiol. 2005;94:255–64. doi: 10.1152/jn.00970.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Scivoletto G, Morganti B, Molinari M. Early versus delayed inpatient spinal cord injury rehabilitation: an Italian study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2005;86:512–6. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Bareyre FM, Schwab ME. Inflammation, degeneration and regeneration in the injured spinal cord: insights from DNA microarrays. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:555–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Dietz V, Harkema SJ. Locomotor activity in spinal cord-injured persons. J. Appl. Physiol. 2004;96:1954–60. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00942.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Conway BA, Hultborn H, Kiehn O. Proprioceptive input resets central locomotor rhythm in the spinal cat. Exp. Brain Res. 1987;68:643–56. doi: 10.1007/BF00249807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hiebert GW, Whelan PJ, Prochazka A, Pearson KG. Contribution of hind limb flexor muscle afferents to the timing of phase transitions in the cat step cycle. J. Neurophysiol. 1996;75:1126–37. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.3.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Rossignol S, Bouyer L, Langlet C, Barthelemy D, Chau C, Giroux N, Brustein E, Marcoux J, Leblond H, Reader TA. Determinants of locomotor recovery after spinal injury in the cat. Prog. Brain Res. 2004;143:163–72. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(03)43016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Chapman CE, Sullivan SJ, Pompura J, Arsenault AB. Changes in hip position modulate soleus H-reflex excitability in man. Electromyogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1991;31:131–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Knikou M. Effects of hip joint angle changes on intersegmental spinal coupling in human spinal cord injury. Exp. Brain Res. 2005:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0046-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Cote MP, Gossard JP. Step training-dependent plasticity in spinal cutaneous pathways. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:11317–27. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1486-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Tanaka R. Reciprocal Ia inhibition during voluntary movements in man. Exp. Brain Res. 1974;21:529–40. doi: 10.1007/BF00237171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Reese NB, Skinner RD, Mitchell D, Yates C, Barnes CN, Kiser TS, Garcia-Rill E. Restoration of frequency-dependent depression of the H-reflex by passive exercise in spinal rats. Spinal Cord. 2006;44:28–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Gomez-Pinilla F, Ying Z, Roy RR, Molteni R, Edgerton VR. Voluntary exercise induces a BDNF-mediated mechanism that promotes neuroplasticity. J. Neurophysiol. 2002;88:2187–95. doi: 10.1152/jn.00152.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Skup M, Dwornik A, Macias M, Sulejczak D, Wiater M, Czarkowska-Bauch J. Long-term locomotor training up-regulates TrkBFL receptor-like proteins, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, and neurotrophin 4 with different topographies of expression in oligodendroglia and neurons in the spinal cord. Exp. Neurol. 2002;176:289–307. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Hutchinson KJ, Gomez-Pinilla F, Crowe MJ, Ying Z, Basso DM. Three exercise paradigms differentially improve sensory recovery after spinal cord contusion in rats. Brain. 2004;127:1403–14. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Geremia NM, Gordon T, Brushart TM, Al-Majed AA, Verge VM. Electrical stimulation promotes sensory neuron regeneration and growth-associated gene expression. Exp. Neurol. 2007;205:347–59. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Al-Majed AA, Brushart TM, Gordon T. Electrical stimulation accelerates and increases expression of BDNF and trkB mRNA in regenerating rat femoral motoneurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2000;12:4381–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Al-Majed AA, Tam SL, Gordon T. Electrical stimulation accelerates and enhances expression of regeneration-associated genes in regenerating rat femoral motoneurons. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2004;24:379–402. doi: 10.1023/B:CEMN.0000022770.66463.f7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]