Highlights

-

•

Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis is the 3rd indication for liver transplantation.

-

•

Obese transplanted patients have higher morbidity and mortality rates.

-

•

Bariatric surgery decreases morbidity and mortality in obese patients.

-

•

Combined liver transplant and sleeve gastrectomy can be safely performed.

Keywords: Liver transplantation, Obesity, Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis cirrhosis, Bariatric surgery, Sleeve gastrectomy, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Obesity is a contributor to the global burden of chronic diseases, including non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). NASH cirrhosis is becoming a leading indication for liver transplant (LT). Obese transplanted patients have higher morbidity and mortality rates. One strategy, to improve the outcomes in these patients, includes bariatric surgery at the time of LT. Herein we report the first European combined LT and sleeve gastrectomy (SG).

Case presentation

A 53 years old woman with Hepatocellular carcinoma and Hepatitis C virus related cirrhosis, was referred to our unit. She also presented with severe morbid obesity (BMI 40 kg/m2) and insulin-dependent diabetes. Once listed for LT, she was assessed by the bariatric surgery team to undergo a combined LT/SG. At the time of transplantation the patient had a model for end-stage liver disease calculated score of 14 and a BMI of 38 kg/m2.

The LT was performed using a deceased donor. An experienced bariatric surgeon, following completion of the LT, performed the SG. Operation time was 8 h and 50 min. The patient had an uneventful recovery and is currently alive, 5 months after the combined procedure, with normal allograft function, significant weight loss (BMI = 29 kg/m2), and diabetes resolution.

Conclusion

Despite the ideal approach to the management of the obese LT patients remains unknown, we strongly support the combined procedure during LT in selected patients, offering advantages in terms of allograft and patient survival, maintenance of weigh loss that will ultimately reduce obese related co-morbidities.

1. Introduction

The current obesity epidemic is one of the greatest public health concerns of our century [1]. In Europe, obesity has reached epidemic proportions [2]. The prevalence of obesity, defined as body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2, varies between 6% and 20%, with higher prevalence in Central and Eastern Europe [3]. If the observed trends of increasing prevalence of obesity persist, by 2030 the absolute number of obese individuals could rise to a total of 1.12 billion, accounting for 20% of the world’s adult population [4].

Obesity is a major contributor to the global burden of chronic diseases and disabilities, including non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

NAFLD encompasses a spectrum of liver injuries that range from benign steatosis to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). NASH cirrhosis marks the final stage within the spectrum of NAFLD, and is becoming a leading indication for liver transplant (LT) in the United States [5], being currently the third most common indication for liver transplantation, and it is expected to become the most common indication for LT within the next 1–2 decades.

A high proportion of obese patients are a priori excluded from LT because of co-morbidities. Obesity is in fact strongly associated with diabetes, heart disease and cancer, which are leading causes of morbidity and mortality post-LT [6]. One strategy, aiming to improve the outcomes in this category of patients, includes bariatric surgery at the time of LT as described for the first time by Heimbach et al. [7], reporting their experience of combined LT and gastric sleeve resection (SG) in 7 patients with BMI greater than 35 kg/m2.

The benefits of combined surgery are that it involves a single operation and recovery for the patient, and therefore avoids a potentially harsher re-operative field, as well as avoiding delays due to complications such as rejection, infection, renal insufficiency or disease recurrence or other barriers to weight loss surgery such as insurance coverage and patient hesitation to undergo yet another invasive procedure.

Herein we report to the best of our knowledge the first European combined LT and SG.

2. Case report

A Caucasian 53 years old woman was referred to our Transplant Unit with Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), inside Milan criteria, which was assessed with whole body CT scan and bone scintigraphy excluding the presence of metastasis. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1b infection was diagnosed 6 years earlier; at the time of listing the patient presented a sustained viral response (SVR12) after 24 weeks combination of sofosbuvir and ledipasvir plus ribavirin.

The patient presented grade 2 oesophageal varices at endoscopy. Her medical history also included a long-standing severe morbid obesity with a BMI of 40 kg/m2 with type 2 diabetes (insulin-dependent) and no other comorbities.

A multidisciplinary team (including dietician, psychologist and bariatric surgeon) assessed the patient, who had a dietary pattern of “big eater”, therefore with a great risk of failure to maintain weigh loss after transplant, thus she was listed for LT with a combined SG. Nevertheless a dietary education was provided by an experienced transplant dietician during the first evaluation, requiring the patient to follow a calorie-restricted diet to reduce the BMI before surgery.

A month later she was listed for LT, we proceeded to a combined LT plus SG. At the time of transplantation the patient had a model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) calculated score of 14 and a BMI of 38 kg/m2.

The LT/SG was performed using a whole liver (1754 gr) from a 54 years old deceased donor, using a right subcostal incision, with a caval sparing hepatectomy (briefly clamping the portal vein without the need for a temporary porto-caval shunt) and a duct to duct biliary anastomosis. The SG was performed by an experienced bariatric surgeon following completion of the LT. The greater curvature of the stomach was mobilised up to the left diaphragmatic crus. Subsequently the resection was done with a combination of 45-mm and 60-mm Endo-GIA staple loads from the antrum up to the fundus, utilizing a 32 Fr orogastric tube placed along the lesser curve of the stomach.

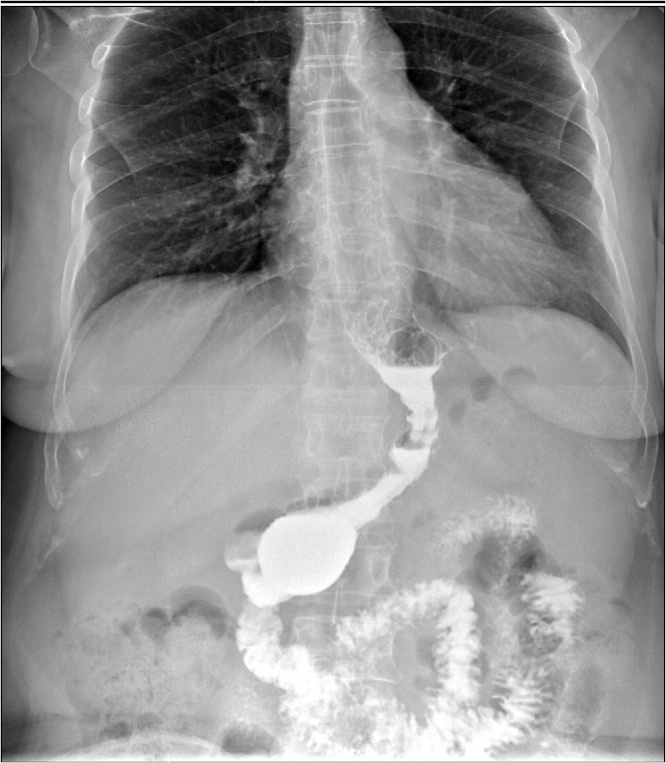

A methylene blue test was performed to assess the staple line, with no evidence of leakage. Operation time was 8 h and 50 min, requiring transfusions with 2 units of blood and 10 units of fresh frozen plasma. The patient received standard immunosuppression consisting of tacrolimus once daily and everolimus, with the target levels of 5–8 ng/mL and 3–8 ng/mL respectively, as per our centre protocol. The patient had an uneventful recovery, with no evidence of leak from the gastric staple line (Fig. 1) and she was discharged 2 weeks after the combined procedure. Histological findings of the tumour were of a moderately differentiated hepatocellularcarcinoma (Edmonson grade 2), single nodule of 3 × 2.4 × 1.6 cm, on a background of hepatic cirrhosis.

Fig. 1.

Gastrografin study following sleeve gastrectomy showing absence of leakage.

The patient is currently alive, 5 months after the combined procedure, with normal allograft function, non detectable HCV RNA level, showing significant weight loss (BMI = 29 kg/m2, BMI trend is shown in Fig. 2), no longer requiring insulin or oral hypo-glycemic treatment; she is actually only on immunosuppression drugs (pre and post-LT patient and donor details are showed in Table 1). In addition, there is no evidence of steatosis based on protocol ultrasound performed during the follow-up.

Fig. 2.

BMI Trend.

Table 1.

Patient and Donor details.

| Before LT | Day1 | Day7 | 1 Month | 3 Months | 5 Months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AST U/L | 22 | 4382 | 102 | 37 | 26 | 18 |

| ALT U/L | 21 | 2145 | 106 | 27 | 32 | 23 |

| Bilirubin mg/dl | 1,17 | 2,8 | 5 | 0,99 | 0,87 | 0,52 |

| GGT UI/L | 35 | 133 | 644 | 190 | 78 | 44 |

| ALP UI/L | 159 | 125 | 216 | 116 | 75 | 59 |

| Creatinine mg/dl | 0,75 | 1,3 | 1,16 | 0,65 | 0,39 | 0,96 |

| INR | 1,82 | 3,9 | 2,85 | 2,43 | 1,61 | 1,62 |

| HbA1c mmol/mol | 55 | – | 51 | 45 | 37 | 28 |

| αfetoproteine UI/ml | 11,5 | – | – | 3,4 | 2,9 | 2,2 |

|

Donor HLA typing Recipient HLA typing |

A2 A23 B44 B57 Cw5 Cw7 DR7 DR13 DQ7 DQ9 A11 A25 B13 B18 Cw7 DR7 DR11 DQ2 DQ7 |

|||||

AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: alanine transaminase; GGT: gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; HbA1c: glycated haemoglobin; HLA: human leukocyte antigens.

3. Discussion

NAFLD and NASH are increasingly relevant public health issues owing to their close association with the worldwide epidemic of obesity. As seen in our patient, it is recognized that NAFLD/NASH can occur together with other chronic liver diseases, namely HCV [8], and that in some cases, this can exacerbate liver damage [9]. Notably, the burden of NAFLD related cirrhosis may be under-estimated, as the histological signs of steatohepatitis may no longer be present at the cirrhotic stage of disease [10], like in this report with a patient with long-standing morbid obesity. Moreover, obese or diabetic patients have an increased risk of HCC [11], [12] even in association with other chronic liver diseases [13]. NAFLD and NASH, either de novo or recurrent, are commonly seen also after LT [14], [15] with BMI prior and following LT, diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension and hyperlipidaemia as the major risk factors for post-LT NAFLD/NASH.

Actually there are not specific recommendation regarding prevention and treatment of NAFLD/NASH in LT recipients, except to avoid excessive weight gain.

Moreover, obese transplanted patients have higher morbidity and mortality rates compared to those performed in patients with normal BMI. This has been described clearly in a recent series of 306 obese liver transplant recipients over 11 years where patient and graft survival, blood product transfusion, intensive care unit length of stay, and biliary complications requiring intervention were all higher in the obese patients [16].

The clinical features of metabolic syndrome, in particular type 2 diabetes, obesity, dyslipidaemia and arterial hypertension, either alone or in combination contribute to late post-operative morbidity and mortality too. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome lies between 50 and 60% in the LT population [15]. Due to the high prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its different clinical features, LT recipients have a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular events and mortality compared to an age and gender-matched general population [17]. Therefore, cardiovascular disease accounts for almost a quarter of deaths in the long-term follow-up after LT [18].

These apprehensions over outcomes in the obese LT recipient have led to the advent of weight reduction surgery. Data from case series and database reviews have reasonably demonstrated that weight reduction surgery in the LT recipient is a feasible attempt. However, several questions have been raised regarding the type of weight reduction surgery, timing of surgery in relation to LT, patient and allograft survival and post-LT maintenance of weight loss. Early approaches towards combined LT with weight reduction surgery have focused on the use of SG as the weight reduction procedure of choice. Roux-en-Y-bypass and bilio-pancreatic diversion have largely been eliminated from the armamentarium in the LT recipient because of increased complexity with this technique as well as the malabsorption associated that may adversely affect early post-transplant immunosuppression levels [15], [16]; moreover Roux-en-Y gastric bypass has been described to cause hyperammonemia-induced encephalopathy in few cases [19], which could be harsher in the transplant setting. Furthermore, a SG is a procedure that does not interfere with future access to the biliary system should post-transplant complications arise.

In carefully selected patients who have failed a rigorous weight loss program, or that, despite a possible weight loss prior to LT, have a greater risk for weight gain following transplant with the associated metabolic complications, a SG at the time of LT is feasible, efficient and can be performed with minimal additional operative time. Our patient was assessed by a multidisciplinary team and believed to be at high risk for weight gain, and the decrease of BMI in a limited period of time was mainly achieved because she was hospitalised for the transplant evaluation. Our decision was also supported by Heimbach’s series, where, over 3 years of follow-up, 60% of patients who underwent dietary modification and LT alone were not able to sustain the weight loss after transplant.

Weight loss in our patient undergoing combined LT/SG has been steady and gradual, because SG is only a restrictive procedure. Whether the weight loss will be maintained will require long-term follow-up, which is not yet available. We also managed to maintain adequate immunosuppression levels, without the difficulties encountered in malabsorptive procedures. Moreover, the ab initio introduction of everolimus, a proliferation–signal inhibitor with anti-proliferative and immunosuppressive activity [20], has not determined a leak from the gastric staple line, as we adopt a lower dose of mTORi to achieve a trough level of 3–8 ng/mL without an initial loading dose, that can avoid, or at least decrease well-known mTORi-related adverse events, namely dyslipidaemia, wound healing complications, incisional hernia and leucopoenia [21]. The timing of SG in the LT setting, has been also discussed elsewhere [22]. A greater advantage of weight reduction surgery can potentially come in the pre-transplant setting. However, at this stage, there is an increased risk of progressing to decompensated liver failure, and we also must take into consideration the effect of SG on the technical aspects of the future LT. Namely, adhesion formation subsequent to SG can potentially impact the mobilisation of the left lobe of the liver due to strong adhesions between the left lobe of the liver and the staple line of the stomach, and may significantly impact porta hepatis dissection. On the other hand, a SG in the post-transplant scenery, will increase the risk of a more adverse operative field, or could determine delays to weight loss surgery due to post-LT complications like rejection, infection or disease recurrence.

In conclusion, despite the ideal approach to the management of the obese LT patient remains unknown, we strongly support the combined procedure during LT in cautiously selected patients, with benefits that involve a single operation and recovery for the patient, and may offer advantages in terms of allograft and patient survival preventing NASH manifestation, maintenance of weigh loss that will ultimately reduce obese related co-morbidities.

However, well-designed prospective clinical trials that focus on the issues highlighted are needed to guide the transplant community in the care of these difficult patients who will soon account for the majority of the patients in our clinics.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical approval

The patient received an explanation of the procedures and possible risks, and gave written informed consent.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant form funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Laura Tariciotti (performed the transplant and wrote the report); Stefano D’Ugo (critical review, and approval of final draft of the report); Tommaso Maria Manzia (assisted the transplant, critical review, and approval of final draft of the report); Valeria Tognoni (assisted the Sleeve Gastrectomy, critical review, and approval of final draft of the report); Giuseppe Sica (performed the Sleeve Gastrectomy; critical review, and approval of final draft of the report); Paolo Gentileschi (performed the Sleeve Gastrectomy; critical review, and approval of final draft of the report); Giuseppe Tisone (conception of the study, critical review, and approval of final draft of the report).

Guarantor

Laura Tariciotti.

References

- 1.Swinburn B.A., Sacks G., Hall K.D., McPherson K., Finegood D.T., Moodie M.L. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet. 2011;378:804–814. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60813-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berghofer A., Pischon T., Reinhold T., Apovian C.M., Sharma A.M., Willich S.N. Obesity prevalence from a European perspective: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:200. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabin B.A., Boehmer T.K., Brownson R.C. Cross-national comparison of environmental and policy correlates of obesity in Europe. Eur. J. Public Health. 2007;17:53–61. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelly T., Yang W., Chen C.S., Reynolds K., He J. Global burden of obesity in 2005 and projections to 2030. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 2008;32:1431–1437. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agopian V.G., Kaldas F.M., Hong J.C., Whittaker M., Holt C., Rana A., Zarrinpar A., Petrowsky H., Farmer D., Yersiz H., Xia V., Hiatt J.R., Busuttil R.W. Liver transplantation for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: the new epidemic. Ann. Surg. 2012;256:624–633. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826b4b7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watt K., Pedersen R.A., Kremers W.K., Heimbach J.K., Charlton M.R. Evolution of causes and risk factors for mortality post liver transplant: results of the NIDDK long term follow-up study. Am. J. Transplant. 2010;10:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heimbach J.K., Watt K.D., Poterucha J.J., Ziller N.F., Cecco S.D., Charlton M.R., Hay J.E., Wiesner R.H., Sanchez W., Rosen C.B., Swain J.M. Combined liver transplantation and gastric sleeve resection for patients with medically complicated obesity and end-stage liver disease. Am. J. Transplant. 2013;13:363–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moucari R., Asselah T., Cazals-Hatem D., Voitot H., Boyer N., Ripault M.P. Insulin resistance in chronic hepatitis C: association with genotypes 1 and 4, serum HCV RNA level, and liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:416–423. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Powell E.E., Jonsson J.R., Clouston A.D. Steatosis co-factor in other liver diseases. Hepatology. 2005;42:5–13. doi: 10.1002/hep.20750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang R.C., Beilin L.J., Ayonrinde O., Mori T.A., Olynyk J.K., Burrows S. Importance of cardiometabolic risk factors in the association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and arterial stiffness in adolescents. Hepatology. 2013;58:1306–1314. doi: 10.1002/hep.26495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Serag H.B., Hampel H., Javadi F. The association between diabetes and hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review of epidemiologic evidence. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006;4:369–380. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caldwell S.H., Crespo D.M., Kang H.S., Al-Osaimi A.M. Obesity and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(5 Suppl. 1):S97–S103. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veldt B.J., Chen W., Heathcote E.J., Wedemeyer H., Reichen J., Hofmann W.P. Increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with hepatitis C cirrhosis and diabetes mellitus. Hepatology. 2008;47(6):1856–1862. doi: 10.1002/hep.22251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patil D.T., Yerian L.M. Evolution of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease recurrence after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2012;18:1147–1153. doi: 10.1002/lt.23499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watt K.D., Charlton M.R. Metabolic syndrome and liver transplantation: a review and guide to management. J. Hepatol. 2010;53:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LaMattina J.C., Foley D.P., Fernandez L.A., Pirsch J.D., Musat A.I., D’ Alessandro A.M., Mezrich J.D. Complications associated with liver transplantation in the obese recipient. Clin. Transplant. 2012;26:910–918. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2012.01669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Madhwal S., Atreja A., Albeldawi M., Lopez R., Post A., Costa M.A. Is liver transplantation a risk factor for cardiovascular disease? A meta-analysis of observational studies. Liver Transpl. 2012;18:1140–1146. doi: 10.1002/lt.23508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desai S., Hong J.C., Saab S. Cardiovascular risk factors following orthotopic liver transplantation: predisposing factors, incidence and management. Liver Int. 2010;30:948–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kromas M.L., Mousa O.Y., John S. Hyperammonemia-induced encephalopathy: a rare devastating complication of bariatric surgery. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:1007–1011. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i7.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunn C., Croom K.F. Everolimus a review of its use in renal and cardiac transplantation. Drugs. 2006;66:547–570. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200666040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manzia T.M., Angelico R., Toti L., Belardi C., Cillis A., Quaranta C., Tariciotti L., Katari R., Mogul A., Sforza D., Orlando G., Tisone G. The efficacy and safety of mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors ab initio after liver transplantation without corticosteroids or induction therapy. Dig. Liver Dis. 2016;48:315–320. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reino D.C., Weigle K.E., Dutson E.P., Bodzin A.S., Lunsford K.E., Busuttil R.W. Liver transplantation and sleeve gastrectomy in the medically complicated obese: new challenges on the horizon. World J. Hepatol. 2015;7:2315–2318. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i21.2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]