Abstract

Successful human pregnancy requires the maternal immune system to recognize and tolerate the semi-allogeneic fetus. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), which are capable of inhibiting T-cell responses, are highly increased in the early stages of pregnancy. Although recent reports indicate a role for MDSCs in fetal–maternal tolerance, little is known about the expansion of MDSCs during pregnancy. In the present study, we demonstrated that the trophoblast cell line HTR8/SVneo could instruct peripheral CD14+ myelomonocytic cells toward a novel subpopulation of MDSCs, denoted as CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells, with suppressive activity and increased expression of IDO1, ARG-1, and COX2. After interaction with HTR8/SVneo cells, CD14+ myelomonocytic cells secrete high levels of CCL2, promoting the expression of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3. We utilized a neutralizing monoclonal antibody to reveal the prominent role of CCL2 in the induction of CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs. In combination, the results of the present study support a novel role for the cross-talk between the trophoblast cell line HTR8/SVneo and maternal CD14+ myelomonocytic cells in initiating MDSCs induction, prompting a tolerogenic immune response to ensure a successful pregnancy.

Keywords: CCL2, MDSCs, tolerance in pregnancy, trophoblast cells

INTRODUCTION

The key events during early pregnancy are successful embryo implantation and the establishment of fetal–maternal tolerance1. There is a diverse population of maternal leukocytes that not only mediate the implantation and promotion of trophoblast differentiation but also regulate the maternal immune response to promote tolerance of the fetal semi-allograft. As major leukocyte subsets, CD14+ myelomonocytic cells increase after embryo implantation and closely contact fetal trophoblast cells. Owing to their remarkable plasticity, cytokine production, and functional properties, different subtypes of maternal CD14+ myelomonocytic cells perform multiple disparate functions during early pregnancy2,3,4,5. Maternal CD14+ myelomonocytic cells have gained increasing attention, as these cells play a multifaceted role during early pregnancy; however, the definition of new subsets and the contribution of each population to the immunological microenvironment of pregnancy are just beginning to emerge.

CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells, a subset of CD14+ myelomonocytic cells, exhibit potent suppressive activity6, and these cells are monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MO-MDSCs)7,8, which have emerged as key immune modulators orchestrating lymphocyte responses. There is increasing interest in the role of MDSCs as tolerance-inducing cells during pregnancy9,10. Although studies have suggested that isolated myeloid cells or MDSCs from the peripheral blood of pregnant women could efficiently suppress T-cell proliferation, information concerning the mechanisms governing MDSCs mobilization, particularly during the implantation and invasion of trophoblast cells, is lacking.

As key mediators, chemokines coordinate the complicated cellular migration or interactions between trophoblast cells and immunocytes at the maternal–fetal interface11,12. As the first identified chemokine C-C motif ligand, CCL2 was markedly increased at the fetomaternal interface during blastocyst implantation13. This chemokine has been shown to mediate the local recruitment of CD14+ myelomonocytic cells, T cells and natural killer (NK) cells into various tissues14. Notably, studies have shown that CCL2 also promotes the development of polarized Th2 responses and mediates immune tolerance15,16. Although some studies have shown that both the existence of MDSCs and the increasing production of CCL2 significantly promote immunotolerance toward embryonic tissues, limited evidence is available concerning an association between MDSCs and CCL2 during the early stages of pregnancy. Trophoblast cells might be potential candidates for immunotolerance, as these cells recruit and activate CD14+ myelomonocytic cells and, upon appropriate stimulation, produce CCL217. Trophoblast cells educate and induce maternal leukocytes toward differentiation, thereby promoting a tolerogenic immune response to ensure a successful pregnancy17,18,19. Thus, the functional programs of CD14+ myelomonocytic cells are probably activated and mobilized upon cross-talk with trophoblast cells.

To determine the role for trophoblast cells in the education of maternal CD14+ myelomonocytic cells, the establishment of an in vitro coculture system is necessary. In the current study, the trophoblast cell line HTR8/SVneo20,21 and CD14+ myelomonocytic cells, isolated from peripheral blood, were employed in a coculture system. We investigated the interaction between these cells for the potential expansion of CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells and examined the role of CCL2 during this process.

Materials and Methods

Donor recruitment and blood sample preparation

A total of 21 healthy nonpregnant women and 13 healthy pregnant women at the early stages of pregnancy participated in the present study after providing consent in accordance with the Ethics Committee of Qilu Hospital. Peripheral blood was collected from pregnant (20–35 years of age), and nonpregnant females of similar age distributions served as controls. White blood cells (WBC) were obtained from these donors and used for cytometry analysis. In coculture experiments, PBMCs or other isolated cells were collected from healthy nonpregnant donors.

Reagents and antibodies

The fluorescently labeled anti-human mAbs against CD14-FITC, CD14-PE, HLA-DR-PE-Cy7, and CD4-APC and isotype antibodies used for flow cytometric analysis and the Annexin V/APC kit used for cell apoptosis analysis were obtained from Becton-Dickinson Biosciences (San Diego, CA, USA). Red blood cell (RBC) lysis buffer was purchased from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA, USA). The CellTrace CFSE Cell Proliferation Kit for proliferation assays was obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA). CD14 and CD4 Microbeads were obtained from Miltenyi Biotech (Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany). The anti-human CD3ε mAb, anti-human CD28 mAb, mouse anti-human CCL2 neutralizing antibody and isotype antibodies were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). For western blot analysis, rabbit anti-human STAT3 and anti-human phosphor-STAT3 mAbs were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Boston, MA, USA), and the mouse anti-human β-actin mAb was purchased from Jingmei (Beijing, China).

Cell isolation and sorting

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated through centrifugation over Ficoll Histopaque-1077 gradients (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) using the peripheral blood of healthy nonpregnant female volunteers. To isolate CD14+ myelomonocytic cells, the PBMCs were suspended in MACS buffer (0.5% bovine serum albumin) and incubated with CD14 MicroBeads at 4°C for 15 minutes. The cell suspension was applied onto an MS separation column (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) attached to a magnetic field. After washing the column three times, the labeled CD14+ myelomonocytic cells were collected according to manufacturers' instructions. To isolate CD4+ T cells, PBMCs were purified using CD4 Microbeads and an MS separation column according to the manufacturers' instructions. The isolated CD14+ myelomonocytic cells and CD4+ T cells was>95% pure, assessed using flow cytometry. In some coculture experiments, CD14+ myelomonocytic cells were sorted into CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells and CD14+HLA-DR+ cells using the BD Influx cell sorting system (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA). The purity of the cells was>98% after sorting.

Coculture system studies

The trophoblast cell line HTR8/SVneo was a kind gift from Dr. Charles Graham (Queens University, Kingston, ON, Canada). These cells were acquired from human explant cultures obtained from the first trimester placenta and immortalized through transfection using a cDNA construct encoding the SV40 large T antigen22. These non-tumorigenic and metastatic cells are highly invasive in vitro and exhibit various markers of extravillous trophoblasts in situ21,22. HTR8/SVneo cells were seeded (1 mL/well, 5 × 105/mL) onto a 6-well culture plate (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and incubated for 4 hours to facilitate attachment. The CD14+ myelomonocytic cells (1 mL, 1 × 106/mL) were subsequently plated onto culture plates. In transwell coculture experiments, 0.4 μm transwell inserts (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) were used to separate CD14+ myelomonocytic cells and HTR8/SVneo cells. CD14+ myelomonocytic cells (1 mL, 1 × 106/mL) were removed using 0.4 μm culture inserts and subsequently transferred into the wells containing HTR8/SVneo cells. These cells were cocultured in complete RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco-Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at 37°C for 40 hours. Next, the cell extracts and cell-free supernatants were collected. In some experiments, 10 μg/mL anti-CCL2 neutralizing mAb was added to the coculture system for 40 hours, and then the cell-free supernatants and cells were collected.

Flow cytometric analysis

To detect the frequency of CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells in peripheral WBC and coculture systems, whole-blood samples or further isolated cells were stained with fluorescently labeled Abs for 30 minutes in the dark at room temperature. To detect CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells among WBC populations, 1 mL of RBC lysis buffer (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA) was added to a 200-μL aliquot of the peripheral blood sample for 10 minutes. Cell acquisition was performed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA), and the data were analyzed using the CellQuest software program (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA).

T-cell suppression assay

To detect the suppressive capability of MDSCs, CD14+ myelomonocytic, CD14+HLA-DR−/low, or CD14+HLA-DR+ cells (100 μL, 5 × 105/mL) were sorted from the coculture system and subsequently cultured with isolated allogeneic CD4+ T cells according to the methods described above for “cell isolation and sorting”, using different CD14+ cell/T-cell ratios (1:1, 1:2, and 1:4) in complete RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS at 37°C for 40 hours. The autologous CD4+ T cells were stained with CFSE according to the manufacturer's instructions, absorbed onto 96-well microtiter plates (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and activated with αCD3 (1 μg/mL), αCD28 (5 μg/mL) and rhIL-2 (20 U/mL) for 3, 5, or 7 days. The CFSE signal of CD4+ T cells was determined using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer.

Cytokine and chemokine analysis

The supernatant obtained from different culture groups was centrifuged at 2000g and immediately stored in liquid nitrogen until further use. The amount of human cytokines and chemokines, including CCL2, TGF-β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10, in the coculture system and control supernatant was measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (R&D Systems, UK) according to the manufacturer's instructions. All measurements were performed in triplicate to avoid technical errors and intra-assay variants.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR (RTQ-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from CD14+ myelomonocytic, CD14+HLA-DR−/low, and CD14+HLA-DR+ cells sorted from the coculture system using the Qiagen RNeasy mini kit (Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was reverse-transcribed to complementary DNA using RevertAid M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase (Fermentas, Burlington, Ontario, Canada) with Oligo dT primers (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). IDO1, arginase-1 (ARG-1), IL-4Rα (CD124), NOS2, and COX2 were amplified through RTQ-PCR using the SYBR Green I (Bio-Rad, München, Germany) method in 10 μL reactions (5 μL of 2X TaqMan Master mix, 1 μL of each primer, 1 μL of cDNA, and 2 μL of H2O). All procedures were conducted according to the manufacturer's guidelines. RTQ-PCR was performed using a LightCycler 2.0 Instrument (Roche, Penzberg, Germany). The primer sequences are shown in Table 1. The relative gene expression was normalized to GAPDH mRNA levels and expressed as a fold change for each relative gene reaction among the samples.

Table 1. Primer pairs used for real-time quantitative RT-PCR.

| Genes | Primers | Products (bp) |

| GAPDH | For: 5′-GGGGAGCCAAAAGGGTCATCATCT-3′ | 235 |

| Rev: 5′-GAGGGGCCATCCACAGTCTTCT-3′ | ||

| IDOl | For: 5′-TCTCATTTCGTGATGGAGACTGC-3′ | 130 |

| Rev: 5′-GTGTCCCGTTCTTGCATTTGC-3′ | ||

| ARGl | For: 5′-TGGACAGACTAGGAATTGGCA-3′ | 102 |

| Rev: 5′-CCAGTCCGTCAACATCAAAACT-3′ | ||

| NOS2 | For: 5′-AGGGACAAGCCTACCCCTC-3′ | 168 |

| Rev: 5′-CTCATCTCCCGTCAGTTGGT-3′ | ||

| IL-4R α | For: 5′-TCATGGATGACGTGGTCAGT-3′ | 147 |

| Rev: 5′-GTGTCGGAGACATTGGTGTG-3′ | ||

| COX2 | For: 5′-CCCTTGGGTGTCAAAGGTAA-3′ | 121 |

| Rev: 5′-GCCCTCGCTTATGATCTGTC-3′ |

Western blotting

A total of 50 μg of protein from each treatment group was separated on an 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel for STAT-3, pSTAT-3, and β-actin, respectively. The proteins were transferred to polyvinyl difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA), which were subsequently blocked and immunoblotted with the appropriate primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The membranes were washed, and the bounded antibodies were visualized using peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA). The results were visualized through chemiluminescence detection using an ECL Kit (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) on an Image Station 4000 MM Pro (Carestream Health Inc., USA).

Statistical analysis

Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, CA, USA) was used for statistical analysis. We used the Shapiro–Wilk's test to analyze the normality of the data. When the data were normally distributed, we used a two-tailed Student's t-test and Pearson's test. Non-normally distributed data were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test. For all statistical tests, p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The data from independent experiments are presented as the mean values ± standard error of the mean (mean ± SEM) for percentages.

Results

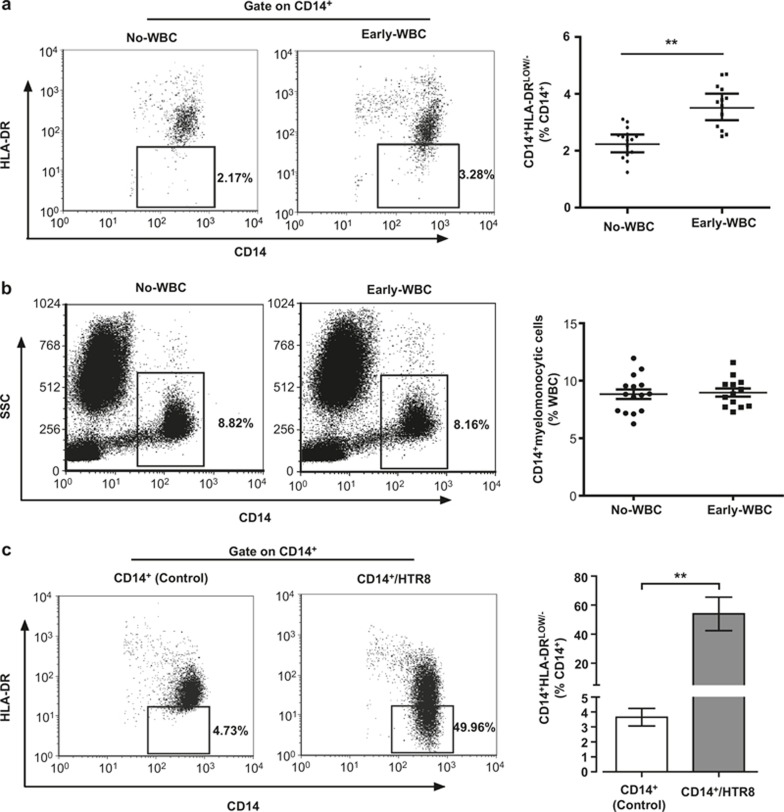

CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells are increased in the peripheral blood of women during early pregnancy and can be induced through trophoblast cells in vitro

Recent studies indicated that increased CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells in peripheral blood and placental tissue contributed to immune tolerance as MO-MDSCs. Therefore, we examined the abundance of peripheral blood CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells. As shown in Figure 1A, the percentage of CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells in circulating CD14+ myelomonocytic cells among the total WBC population was significantly higher in pregnant women during early pregnancy (3.586 ± 0.211%) as compared with non-pregnant female volunteers (2.295 ± 0.136%) (p <0.001). However, no significant difference (p = 0.4353) in the percentage of CD14+ myelomonocytic cells among the total WBC population was observed (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells are increased in the peripheral blood of women during early pregnancy and can be induced through trophoblast cells in vitro. Flow cytometry showed that the percentage of CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells in CD14+ myelomonocytic cells (A) was increased in Early-WBC (early pregnant women peripheral blood white blood cells; n = 13) versus No-WBC (non-pregnant women peripheral blood white blood cells; n = 15). (B) The percentage of CD14+ cells in white blood cells from 15 non-pregnant women and 13 early-pregnant women were analyzed. (C) A total of 1 × 106 CD14+ myelomonocytic cells, isolated from the PBMCs of the participants, were cocultured with 5 × 105 HTR8/SVneo cells (gray bar) or culture alone (white bar) for 40 hours and analyzed for the proportion of CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells in nine different experiments (i.e., using CD14+ myelomonocytic cells derived from nine different non-pregnant healthy female donors). The bars indicate the mean percentage ± SEM of CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells assessed in coculture or control; *p <0.001. The numbers represent the percentage of cells in the indicated boxes.

Increasing attention has been paid to the complex immunoregulatory function of trophoblast cells in close contact with immunocytes. Therefore, we investigated whether circulating CD14+ myelomonocytic cells develop into CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells after contact with trophoblast cells. A coculture system was employed to partially monitor the interactions between CD14+ myelomonocytic and trophoblast cells. As shown in Figure 1C, after coculture with the trophoblast cell line HTR8/SVneo cells for 40 hours, the percentage of CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells in CD14+ myelomonocytic cells was significantly increased as compared with the control group (53.94 ± 3.639% and 3.436 ± 0.430%, p <0.001). The gating strategies for representative dot plots are shown in the supplementary information (Supplementary Figure 1A and B). To eliminate the downregulation of HLA-DR, potentially occurring during the early apoptosis stage of CD14+ myelomonocytic cells, we examined the apoptosis of CD14+ myelomonocytic cells using a coculture system. The data indicated that the percentage of apoptotic CD14+ myelomonocytic cells in the coculture system was less than 6.5% (Supplementary Figure 2A). In summary, HTR8/SVneo cells were probably involved in the expansion of CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells.

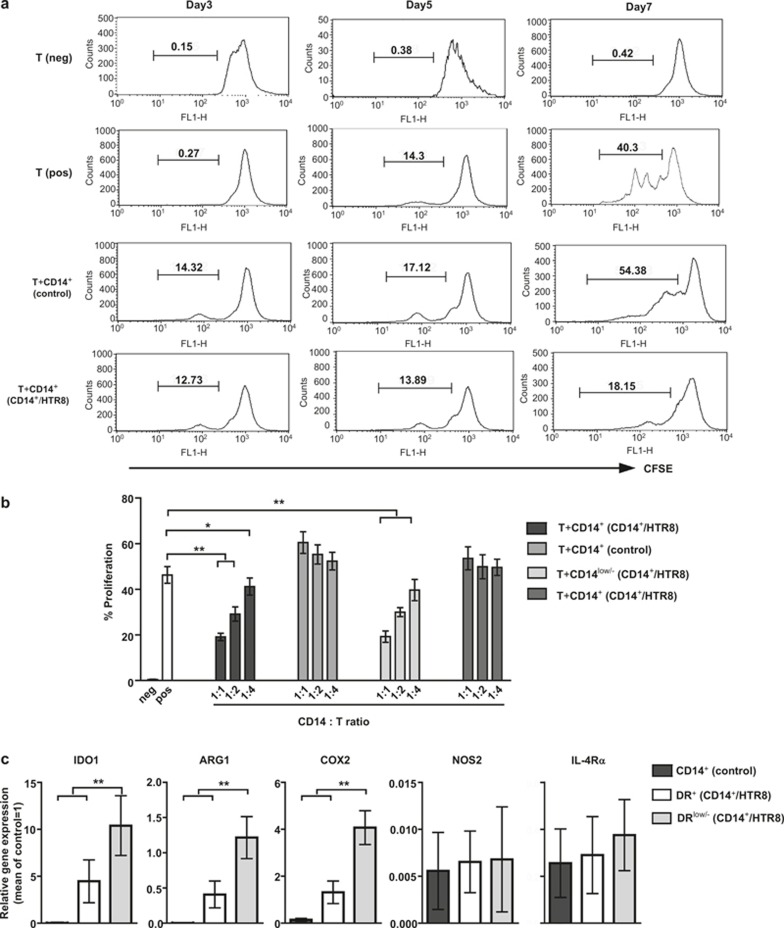

CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells from coculture system are MDSCs that inhibit autologous T-cell proliferation

To determine whether the CD14+ myelomonocytic cells in coculture system possess MDSC functions, we examined the ability of these cells to inhibit CD4+ T-cell proliferation activated via anti-CD3/CD28 mAbs as described in Materials and Methods section. CFSE-labeled autologous CD4+ T cells were used as responders. As shown in Figure 2A, the percentage of expanding CD4+ T cells did not show significant changes in various groups in the first 5 days. However, only CD14+ myelomonocytic cells isolated from coculture system lead to significant CD4+ T cell suppression after day 7. By contrast, CD14+ myelomonocytic cells alone showed no inhibitory effect. Thus, these data suggested that trophoblast cells might educate circulating CD14+ myelomonocytic cells as suppressor cells with inhibitory activity on T-cell proliferation.

Figure 2.

CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells isolated from the coculture system exhibited suppressive activity on T-cell proliferation with high levels of MDSC-associated suppressive molecules. The circulating CD14+ myelomonocytic cells from normal non-pregnant female donors cultured with (CD14+/HTR8) or without (control) HTR8/SVneo cells. CD14+ myelomonocytic cells were harvested after 40 hours of coculture as described in the Materials and Methods section. (A) CD14+ myelomonocytic cells sorted from different groups, mixed with allogeneic CFSE-labeled CD4+ T cells plated onto anti-CD3/CD28-coated 96-well plates (1:1 CD14+:CD4+ ratio) for 3, 5, and 7 days to assess the inhibition of T-cell ←proliferation. T (pos) represents wells with CD4+ cells and anti-CD3/CD28, but without CD14+ myelomonocytic cells, and T (neg) represents wells with CD4+ cells, but without anti-CD3/CD28 and CD14+ myelomonocytic cells. The percent CD4+ T-cell proliferation was measured after assessing CFSE dilution using flow cytometry. The images were obtained from one experiment representing nine independent experiments. The numbers represent the percentages of cells in the indicated boxes (B) CD14+ myelomonocytic cells were flow sorted for CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells and CD14+HLA-DR+ cells after 40 hours of coculture. The resorted CD14+HLA-DR−/low and CD14+HLA-DR+ cells were cocultured with autologous-stimulated CD4+ T cells for 24 hours at different ratios. The cumulative results from nine independent experiments are shown. *p <0.05; **p <0.001. (C) Freshly isolated CD14+ myelomonocytic cells cultured without HTR8/SVneo cells for 40 hours (Figure 2A) or sorted for CD14+HLA-DR−/low and CD14+HLA-DR+ cells after 40 hours of coculture with HTR8/SVneo cells (Figure 2B) were analyzed for IDO1, ARG1, COX2, NOS2, IL-4Rα mRNA expression. RTQ-PCR was performed using primers specific for IDO1, ARG1, COX2, NOS2, IL-4Rα, and GAPDH as a positive control. The relative gene expression was normalized to GAPDH mRNA levels and expressed as a fold increase. The cumulative results from nine independent experiments are shown. **p <0.001 for each comparison. The data are presented as the means ± SEM.

To directly assess whether CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells generated in vitro after colculture with CD14+ myelomonocytic cells with HTR8/SVneo cells could indeed exert the suppressor functions of MO-MDSCs, as previously reported in other nonpregnancy systems8. CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells sorted from coculture systems were added to activated autologous CD4+ T cells at different ratios, and proliferation was analyzed. As shown in Figure 2B, CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells efficiently inhibited autologous CD4+ T-cell proliferation, with maximal inhibition at a 1:1 effector–target ratio. Therefore, the cells were cocultured at ratios of 1:1 to dissect the suppressive mechanism in the following experiments. As expected, control CD14+HLA-DR+ myelomonocytic cells sorted from coculture systems failed to suppress the proliferation of the responding autologous CD4+ T cells at any ratio. Thus, the main population of suppressor CD14+ myelomonocytic cells in coculture system was CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells. The gating strategies, including representative dot plots, for all flow cytometric and sorting experiments are shown in supplementary information (Supplementary Figure 1C and Figure 2B).

To determine whether CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells from coculture systems were MDSCs, we analyzed the expression of several typical MDSC-associated mediators of suppressive function, including IDO1, arginase-1 (ARG-1), IL-4Rα (CD124), NOS2, and COX2, using RTQ-PCR. As expected, the results indicated that CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells expressed high levels of IDO1, ARG-1, and COX2 (Figure 2C); CD14+HLA-DR+ cells from coculture systems and CD14+ myelomonocytic cells cultured alone were used as controls. Taken together, these data were consistent with the definition of MO-MDSCs, indicating that HTR8/SVneo cell-induced CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells from circulating CD14+ myelomonocytic cells were MO-MDSCs with highly suppressive activity.

Trophoblast cells regulated CCL2 production in CD14+ myelomonocytic cells

CCL2 is upregulated in the human placenta during early pregnancy and might influence the activation and maturation of CD14+ myelomonocytic cells. To explore the involvement of CCL2 in HTR8/SVneo cell-induced CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs from circulating CD14+ myelomonocytic cells, we investigated CCL2 levels in the coculture system using ELISA. As shown in Figure 3, neither CD14+ myelomonocytic cells nor HTR8/SVneo cells secreted high levels of CCL2, whereas CCL2 levels increased>100-fold upon coculture for 40 hours (Figure 3A). To ascertain whether the elevated levels of CCL2 and expansion of CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells in coculture were specific for trophoblast cells, we also utilized HUVECs and the endothelial cell line ECV304 in coculture with CD14+ myelomonocytic cells. Flow cytometric analysis and ELISA detection showed that neither of these cell lines was involved in the expansion of CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells. Furthermore, there was no significant difference between the levels of CCL2 in these coculture systems and CD14+ myelomonocytic cell culture alone (Supplementary Figure 3). Furthermore, we examined the expression of cytokines, including IL-4, IL-8, IL-6, IL-10, and TGF-β, which also play an important role in contributing to fetal–maternal tolerance during the first trimester of pregnancy. As shown in Figure 3A, the level of secreted TGF-β was slightly increased in the supernatants of coculture systems, but no significant changes in the levels of other cytokines were observed.

Figure 3.

HTR8/SVneo cells induce CCL2 secretion in cocultured CD14+ myelomonocytic cells. CD14+ myelomonocytic cells cocultured with HTR8/SVneo cells (CD14+/HTR8) for 40 hours (prepared as described in Materials and Methods section). CD14+ myelomonocytic cells or HTR8/SVneo cells cultured alone were used as control groups. (A) The graphs show the secretion of CCL2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and TGF-β in the supernatants of coculture system and control groups using ELISA. *p <0.05; **p <0.001. (B) In transwell coculture experiments, CD14+ myelomonocytic and HTR8/SVneo cells were cultured in two-chambered wells (TW) for 40 hours (prepared as described in Materials and Methods section). The supernatants of CD14+ myelomonocytic cells alone or cultured with HTR8/SVneo cells (CD14+/HTR8) were used as a control. The data are presented as the means ± SEM. (C) The comparison of CCL2 gene expression levels in CD14+ myelomonocytic cells or HTR8/SVneo cells from coculture systems (CD14+/HTR8) or control (CD14+ and HTR8). **p <0.001. (D) Dynamic changes in CCL2 expression in the supernatants was detected every 2 hours in the coculture system (CD14+/HTR8) using ELISA. The supernatants of CD14+ myelomonocytic cells or HTR8/SVneo cells were used as control. The data are presented as the means ± SEM.

We utilized transwell cultures to assess whether the increased CCL2 secretion depended on cell–cell contact. As shown in Figure 3B, there was no significant increase in CCL2 levels when CD14+ myelomonocytic cells were cultured in transwell cultures with HTR8/SVneo cells, shown in the figure as CD14+/HTR8 (TW). These results showed that the ability of coculture systems to promote CCL2 secretion depended on cross-talk between CD14+ myelomonocytic cells and HTR8/SVneo cells.

We also determined the source of CCL2 secretion in the supernatant of coculture systems. For this purpose, we sorted CD14+ myelomonocytic cells and HTR8/SVneo cells from coculture systems, and the RTQ-PCR results showed that only CD14+ myelomonocytic cells expressed high levels of CCL2 (Figure 3C). Further analysis indicated that there was no substantial difference in the CCL2 expression between CD14+HLA-DR−/low and CD14+HLA-DR+ cells (data not shown). Furthermore, no CCL2 mRNA could be detected in HTR8/SVneo cells. These data indicate that the primary source of CCL2 is CD14+ myelomonocytic cells, and trophoblast cells promote this process in a cell-to-cell contact manner. To further examine this effect, we also examined the changes in CCL2 secretion in the supernatant. As shown in Figure3 D, there was no visible increase until 6 hours, and the growth rate stabilized after a significant peak at 20 hours.

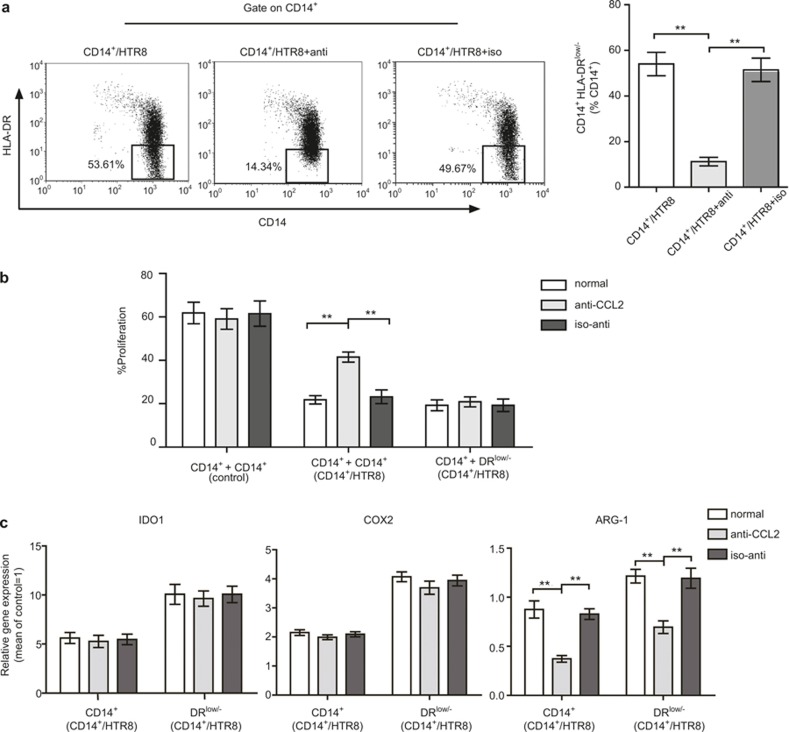

HTR8/SVneo cells expand CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs via CCL2

Increased evidence has shown that CCL2 is gradually over expressed in the tumor site, and this expression is involved in the progression of cancer. Host MDSCs cocultured with tumor cells in the tumor microenvironment also closely connected with CCL223. Given these correlative data, the substantial changes in CCL2 expression in the coculture system indicated that this chemokine was probably an important mediator of the induction of HTR8/SVneo cells on CD14+HLA-DR−/low MO-MDSCs.

To explore the potential role of CCL2 in the experimental setting used in the present study, an anti-CCL2 neutralizing mAb (10 μg/mL) was added to the media of the coculture system at the beginning, and the isotype antibody (10 μg/mL) also served as a negative control. We observed that CD14+ myelomonocytic cells obtained from coculture using isotype antibodies or no antibodies showed a similar frequency of CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs. By contrast, when anti-CCL2 was added to the media, a significant decrease in the percentage of CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs was observed (Figure 4A). Suppression assay showed that the ability of CD14+ myelomonocytic cells to suppress CD4+ T-cell expansion was significantly decreased when CCL2 was neutralized; however, the isotype antibody had no effect (Figure 4B). To further analyze whether the neutralization of CCL2 influences the inhibitory function of CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs, we sorted these cells from different groups (with anti-CCL2, isotype antibody, or no antibody), and suppression assay showed that there was no significant difference in the capacity of these cells to suppress T-cell expansion (Figure 4B). These results showed that the suppression ability of CD14+ myelomonocytic cells decreased, probably reflecting a reduction in the percentage of CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs in coculture systems.

Figure 4.

CD14+ myelomonocytic cell-derived CCL2 was involved in the induction of CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs. Anti-CCL2 neutralizing mAb (10 μg/mL) and the isotype antibody (10 μg/mL) were added to the media of coculture systems as described in Figure. 2 for 40 hours; and CD14+ myelomonocytic cells were harvest or sorted for CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells. (A) Flow cytometric analysis to analyze the frequency of CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs from different treatment groups. The data represent nine independent experiments (means ± SEM), and the images were obtained from one experiment representing nine independently conducted experiments. **p <0.001. The numbers represent the percentages of cells in the indicated boxes. (B) CD14+ myelomonocytic cells from coculture system (CD14+/HTR8) or sorted CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells from coculture system (CD14+/HTR8), and CD14+ myelomonocytic cells cultured alone (control) were added to anti-CD3/CD28 mAb-) Flow cytometric analysis to analyze the frequency of CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs from different treatment groups. The data represent nine independent experiments (means ± SEM), and the images were obtained from one experiment representing nine independently conducted experiments. **p <0.001. The numbers represent the percentages of cells in the indicated boxes. (B) CD14+ myelomonocytic cells from coculture system (CD14+/HTR8) or sorted CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells from coculture system (CD14+/HTR8), and CD14+ myelomonocytic cells cultured alone (control) were added to anti-CD3/CD28 mAb-–stimulated allogeneic CFSE- labeled CD4+ T cells. The inhibitory capability of these cells was analyzed in a 7-day culture assay. T cells were added at a 1:1 (inhibitor: responder) ratio. The percentage of prolife rating CFSE-labeled T cells is indicated. The data are representative of three independent experiments. **p <0.001. (C) The comparison of gene expression levels of candidate suppressive molecules in CD14+ myelomonocytic cells and CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells from coculture systems treated as (A). Relative gene expression was normalized to the GAPDH mRNA levels and expressed as a fold increase. The results are representative of nine independent experiments. All data shown are expressed as the means ± SEM. **p <0.001.

We further explored the expression of several MDSC-associated mediators in CD14+ myelomonocytic cells from different groups. As shown in Figure 4C, compared with isotype antibody or no antibody groups, only ARG-1 was significantly decreased when treated with anti-CCL2. It is unclear whether this reduction reflected a decrease in the number of CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs or the downregulation of ARG-1 expression. To examine this question, we sorted and analyzed CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs from different groups. Consistent with CD14+ myelomonocytic cells, the expression of ARG-1 in CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs also decreased.

Therefore, these results clearly showed that CCL2 plays a substantial role in trophoblast cell-mediated expansion of CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs. In addition, CCL2 also regulates the expression of ARG-1 in MDSCs.

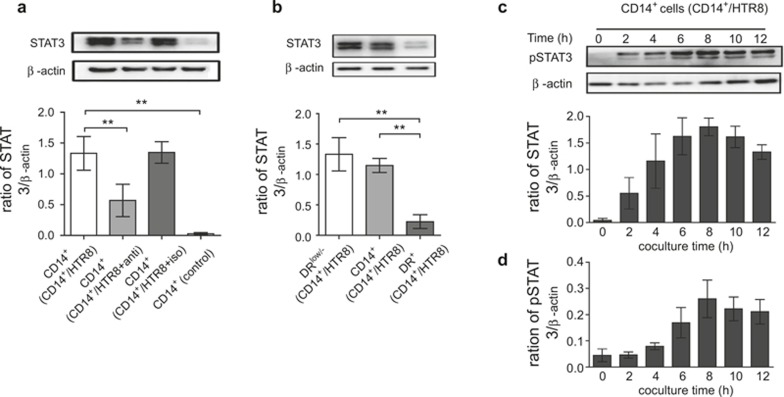

CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells express STAT3 and pSTAT3 associated with increased CCL2

A previous study showed that STAT3 signaling plays an important role in CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs expansion24. We examined whether STAT3 signaling was also involved in the expansion of CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs through cross-talk between CD14+ myelomonocytic cells and trophoblast cells and whether CCL2 mediates this process. CD14+ myelomonocytic cells were sorted from different groups, and the expression of STAT3 was detected through western blot analysis. After culturing for 40 hours, we observed statistically higher STAT3 protein expression in CD14+ myelomonocytic cells from coculture systems (MH) compared with CD14+ myelomonocytic cells cultured alone (M) (Figure 5A). In addition, we also detected the STAT3 expression in sorted CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs and CD14+HLA-DR+ myelomonocytic cells. Figure 5B shows the increased expression of STAT3 protein in CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs compared with other cells.

Figure 5.

CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs express STAT3 and pSTAT3, associated with CCL2. The cells were treated with anti-CCL2 neutralizing mAb or isotype antibody as described in Figure 4</figref>. (A) The effect of CCL2 on STAT3 protein expression in CD14+ myelomonocytic cells from the coculture system (CD14+/HTR8) at 40 hours was detected through western blot analysis, and the respective density was analyzed. (B) STAT3 protein in CD14+ myelomonocytic cells or sorted CD14+HLA-DR−/low and CD14+HLA-DR+ cells from the coculture system was detected using western blotting. (C) CD14+ myelomonocytic cells were cocultured with HTR8/SVneo cells, and the cells were harvested at 0 hours, and every 2 hours for an additional 12 hours thereafter. The expression of phospho-STAT3 (pSTAT3) in CD14+ myelomonocytic cells was detected through western blotting. (D) The protein expression of pSTAT3 in CD14+ myelomonocytic cells sorted from coculture system using an anti-CCL2 neutralizing mAb was detected at the same time points as indicated in (C). All respective bands densities were normalized to β-actin. All images represent nine independent experiments, and all data are shown as the means ± SEM. **p <0.001.

To determine the role of CCL2 in regulating STAT3 signaling, the experiments described in the previous section were performed using CD14+ myelomonocytic cells in an HTR8 coculture system in the absence of CCL2. Accordingly, the STAT3 protein levels were detected through western blotting. As shown in Figure 5A, we observed significantly lower levels of STAT3 expression in a coculture system in the absence of functional CCL2 (MH anti-CCL2 group). To further confirm whether CCL2 exerts an effect on MDSC differentiation via STAT3 signaling, we sorted CD14+ myeloid cells from the coculture system at different time points, and phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3) was detected through western blotting. We observed low levels of pSTAT3 protein expression in CD14+ myelomonocytic cells as early as 2 hours after coculture with HTR8; pSTAT3 expression was sustained, increasing at subsequent time points and peaking after 8 hours (Figure 5C). In contrast, the neutralization of CCL2 suppressed pSTAT3 detection until 6 hours, and this expression was subsequently maintained at a lower level (Figure 5D). In conclusion, these findings demonstrated that STAT3 signaling was involved in the expansion of CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs, and this effect was partially influenced through CCL2.

Discussion

In the present study, we utilized the well-characterized human trophoblast cell line HTR8/SVneo to demonstrate the notable role of these cells in educating CD14+ myelomonocytic cells, resulting in the expansion of immunosuppressive CD14+HLA-DR−/low monocytic MDSCs (MO-MDSCs). To our knowledge, this study presents novel findings suggesting that CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs could be induced using a unique maternal–fetal coculture system, and a positive regulatory loop might exist between trophoblast cells and maternal immune cell subsets to promote to the induction of maternal–fetal immunotolerance.

During the early stages of pregnancy, numerous maternal immune cells, including CD14+ myelomonocytic cells, NK cells, and Tregs, should tolerate invading trophoblast cells to facilitate adequate placental growth and development for the success of pregnancy25,26. Reflecting remarkable plasticity, CD14+ myelomonocytic cells efficiently respond to various environmental stimuli, particularly the semi-allograft, which might induce the differentiation of these cells in a tissue-specific manner for immune regulation and host defense responses2,27–29. Studies have shown that CD14+ myelomonocytic cells, which intimately contact the embryo allograft, displayed a unique ability to promote immunotolerance via the induction of Tregs2. Previous studies have shown that decidual CD14+ myelomonocytic cells express markers associated with alternative activation;30 however, by contrast, a recent report suggests that there are two unique CD14+ myelomonocytic cell subtypes in human decidua, which secrete both anti-inflammatory and proinflammatory cytokines4. Thus, the diverse inhibitory and stimulatory roles of different subtypes of CD14+ myelomonocytic cells imply that the fate determination of these subtypes might be an important mechanism underlying the development of a unique immune microenvironment at the maternal–fetal interface. In this context, we identified an increase in a subpopulation of CD14+ myelomonocytic cells with low or no expression of HLA-DR in the PBMCs of pregnant women during early pregnancy, and these cells can be induced through HTR8/SVneo cells in vitro (Figure 1). Here, we proposed that increased CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells should be associated with the development of successful pregnancy, and trophoblast cells might be involved in the induction of this subpopulation of CD14+ myelomonocytic cells.

Trophoblast cells represent another cell type abundantly present at the maternal–fetal interface. As these cells encounter various maternal immune cells, particularly CD14+ myelomonocytic cells, interactive cross-talk between the cellular compartments is critical for maternal–fetal tolerance17,18,19,31. Previous studies have shown that trophoblast cells express a wide range of chemokines and cytokines, which induce CD14+ myelomonocytic cell differentiation into special subtypes with higher levels of IL10 and increased capacity for phagocytosis31,32. We have performed several functional analyses, revealing that HTR8/SVneo cell-induced CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells effectively inhibited the expansion of CD3/CD28-activated autologous CD4+ T cells (Figure 2). Supporting these data, CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells have recently been identified as a new subpopulation of MDSCs in melanoma patients6.

The robust inhibitory capacity of MDSCs has generated significant interest in the generation and activation of these specialized immunocytes. Human MDSCs can be divided into monocytic (CD14+, MO-MDSCs) and granulocytic (CD14− CD15+, GR-MDSCs) cells based on cell surface markers. Until recently, the different roles of the two MDSC subpopulations have been poorly understood33. In human pregnancy, myeloid cells and highly increased granulocytic-MDSCs (GR-MDSCs) isolated from peripheral blood are more strongly inhibitory toward T-cell proliferation9,10. By contrast with the present study, these authors observed unchanged numbers of peripheral MO-MDSCs in normal pregnant female;10 however, it was not determined whether MDSCs contribute to maternal–fetal tolerance during implantation. These studies did not detect changes in MO-MDSCs numbers, probably reflecting the analysis of the abundance of CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells in all peripheral leukocytes, and an analysis of the percentage of the peripheral CD14+ myelomonocytic cells would be more reasonable. Additionally, it has been proposed that MDSCs exert suppressive activity through an extensive range of mechanisms both in vitro and in vivo. Several key molecules, such as IDO1, arginase-1 (ARG-1), IL4Rα, NOS2, and COX2, mediate these suppressive modalities33. We analyzed the expression of these key molecules and observed that the levels of IDO1, ARG-1, and COX2 expression in CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells in coculture were significantly higher compared with control. These data also implied that HTR8/SVneo cells mediate immunoregulation via the induction of CD14+HLA-DR−/low MO-MDSCs and upregulate IDO1, ARG-1, and COX2 expression in these cells.

The data obtained from in vitro studies showed that various cytokine cocktails could induce MDSC expansion from myeloid cells34. In the present study, a number of associated cytokines were assayed. Compared with other modulatory cytokines, CCL2 expression is profoundly upregulated in CD14+ myelomonocytic cells after culturing with HTR8/SVneo cells, depending on cell–cell contact. As a pleiotropic CC chemokine, CCL2 plays an important role in the migration and differentiation of lymphoid cells14,15,35. In the reproductive system, CCL2 is secreted from decidual, endometrial, and myometrial cells, and this chemokine is elevated on the first day of pregnancy in the mouse uterus13. Recombinant human CCL2 promotes Th2 cytokine production and inhibits the secretion of Th1 cytokines36. Based on the abundant expression of CCL2 at the fetomaternal interface during trophoblast cell invasion, and the efficient recruitment and education of lymphoid cells for the establishment of fetomaternal immune tolerance, we speculated that the sharp increase in CCL2 expression could play an important mediator role in the cross-talk between HTR8/SVneo cells and CD14+ myelomonocytic cells. Indeed, the results of the present study provide clear evidence that CCL2 plays a remarkable role in HTR8/SVneo cell-induced CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs (Figure 4). These data are important as it remains unclear whether CCL2 participates in the induction of MDSCs. The ability of CCL2 to promote CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSC differentiation from peripheral CD14+ myelomonocytic cells is a positive regulatory loop. After secreting considerable amounts of CCL2 at the maternal–fetal interface, CD14+ myelomonocytic cells attract and stimulate themselves in an autocrine manner, leading to the expanding of MDSCs and contributing to maternal–fetal tolerance.

Previous studies have established an important role for signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) in MDSC expansion in mice37,38. These results were further supported by an in vivo study employing the tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib, which inhibited MDSC proliferation in tumor-bearing mice via the inhibition of the STAT3 signaling pathway in myeloid cells39. Recently, an association has been demonstrated between increased STAT3/pSTAT3 activity and MDSC expansion in melanoma patients6. Consistently, these results reveal that both STAT3 and pSTAT3 expression in CD14+ myelomonocytic cells, particularly in CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs, are upregulated through coculture with HTR8/SVneo cells. We also showed that an anti-CCL2 neutralizing antibody remarkably inhibits STAT3 and pSTAT3 expression (Figure 5). This finding indicates that STAT3 signaling is closely associated with the levels of CCL2 expression during HTR8/SVneo cell-induced MDSC expansion.

Notably, anti-CCL2 neutralizing antibodies diminish the frequency of CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs and downregulate the expression of ARG-1 in coculture (Figure 4C). However, there is no significant difference in the capacity to inhibit T-cell proliferation (Figure 4B). Thus, we inferred that the soluble mediator CCL2 plays a substantial role in the induction of CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs, but there are probably other molecules involved in the inhibitory activities of CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs. Further research is required to reveal this potential pathway.

In conclusion, the findings presented here provide substantial evidence for a better understanding of the molecular and cellular mechanisms involved in the establishment and maintenance of maternal–fetal tolerance during the early stages of pregnancy in humans. Indeed, the cross-talk and feedback between the trophoblast HTR8/SVneo cells and CD14+ myelomonocytic cells might play a crucial and positive regulatory role in the expansion of CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs, and this effect is mediated through CCL2. However, the role of MDSCs in the establishment and maintenance of maternal–fetal tolerance has not been clarified. By contrast, the immunocyte-mediated suppression of the maternal immune system also increases the risk of infection during pregnancy. For instance, this suppression might increase the susceptibility to toxoplasmosis and listeriosis and increase mortality rates from influenza and varicella infections. It seems paradoxical to be both tolerant of the embryo and defensive against infection. However, how suppressive immunocytes precisely regulate the maternal immune system in response to various pathological and physiological circumstances requires further study.

Overall, these findings might provide a potential alternative pathway to obtain a better understanding of the maternal immunomodulatory mechanism during pregnancy. Furthermore, the elucidation of the molecular and cellular mechanisms of expanding MDSCs in the establishment of immune tolerance might not only provide a new strategy to overcome immunosuppression mediated through MDSCs in the therapy of cancer patients but also provide new opportunities for inducing tolerance in transplantation.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Dr Charles H. Graham (Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, Queen's University, Kingston, ON, Canada) for providing the HTR8/SVneo cell line. This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 31470885, 31270971, 81300510, 31300752, and 31100650).

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Cellular & Molecular Immunology's website (http://www.nature.com/cmi).

Supplementary Information

References

- Cha J, Sun X, Dey SK. Mechanisms of implantation: strategies for successful pregnancy. Nat Med 2012; 18: 1754–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacca P, Cantoni C, Vitale M, Prato C, Canegallo F, Fenoglio D et al. Crosstalk between decidual NK and CD14+ myelomonocytic cells results in induction of Tregs and immunosuppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2010; 107: 11918–11923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntire RH, Ganacias KG, Hunt JS. Programming of human monocytes by the uteroplacental environment. Reprod Sci 2008; 15: 437–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houser BL, Tilburgs T, Hill J, Nicotra ML, Strominger JL. Two unique human decidual macrophage populations. J Immunol 2011; 186: 2633–2642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagamatsu T, Schust DJ. The contribution of macrophages to normal and pathological pregnancies. Am J Reprod Immunol 2010; 63: 460–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poschke I, Mougiakakos D, Hansson J, Masucci GV, Kiessling R. Immature immunosuppressive CD14+HLA-DR-/low cells in melanoma patients are Stat3hi and overexpress CD80, CD83, and DC-sign. Cancer Res 2010; 70: 4335–4345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höchst B, Schildberg FA, Sauerborn P, Gäbel YA, Gevensleben H, Goltz D et al. Activated human hepatic stellate cells induce myeloid derived suppressor cells from peripheral blood monocytes in a CD44-dependent fashion. J Hepatol 2013; 59: 528–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoechst B, Ormandy LA, Ballmaier M, Lehner F, Krüger C, Manns MP et al. A new population of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in hepatocellular carcinoma patients induces CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells. Gastroenterol 2008; 135: 234–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bitoux M-A, Waeber S, Stamenkovic I. Myeloid cells display immunosuppression activities during pregnancy, participating to the establishment of pre-metastatic niches. Cancer Res 2013; 73: 4980. [Google Scholar]

- Köstlin N, Kugel H, Spring B, Leiber A, Marmé A, Henes M et al. Granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells expand in human pregnancy and modulate T-cell responses. Eur J Immunol 2014; 44: 2582–2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Red-Horse K, Drake PM, Gunn MD, Fisher SJ. Chemokine ligand and receptor expression in the pregnant uterus: reciprocal patterns in complementary cell subsets suggest functional roles. American J Pathol. 2001; 159: 2199–2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayisli UA, Mahutte NG, Arici A. Uterine chemokines in reproductive physiology and pathology. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2002; 47: 213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shynlova O, Tsui P, Dorogin A, Lye SJ. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (CCL-2) integrates mechanical and endocrine signals that mediate term and preterm labor. J Immunol 2008; 181: 1470–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood CJ, Matta P, Krikun G, Koopman LA, Masch R, Toti P et al. Regulation of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression by tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1β in first trimester human decidual cells: implications for preeclampsia. Am J Pathol 2006; 168: 445–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu L, Tseng S, Horner RM, Tam C, Loda M, Rollins BJ. Control of TH2 polarization by the chemokine monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. Nature 2000; 404: 407–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpus WJ, Kennedy KJ, Kunkel SL, Lukacs NW. Monocyte chemotactic protein 1 regulates oral tolerance induction by inhibition of T helper cell 1-related cytokines. J Exp Med 1998; 187: 733–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fest S, Aldo PB, Abrahams VM, Visintin I, Alvero A, Chen R et al. Trophoblast-macrophage interactions: a regulatory network for the protection of pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol 2007; 57: 55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du M-R, Guo P-F, Piao H-L, Wang S-C, Sun C, Jin L-P et al. Embryonic trophoblasts induce decidual regulatory T cell differentiation and maternal–fetal tolerance through thymic stromal lymphopoietin instructing dendritic cells. J Immunol 2014; 192: 1502–1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo P-F, Du M-R, Wu H-X, Lin Y, Jin L-P, Li D-J. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin from trophoblasts induces dendritic cell-mediated regulatory TH2 bias in the decidua during early gestation in humans. Blood 2010; 116: 2061–2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon T, Chakraborty C, Gleeson LM, Chidiac P, Lala PK. Stimulation of human extravillous trophoblast migration by IGF-II is mediated by IGF type 2 receptor involving inhibitory G protein (s) and phosphorylation of MAPK. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001; 86: 3665–3674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen G, Basak S, Weedon-Fekjaer M, Staff A, Duttaroy A. Docosahexaenoic acid stimulates tube formation in first trimester trophoblast cells, HTR8/SVneo. Placenta 2011; 32: 626–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving J, Lysiak J, Graham C, Hearn S, Han V, Lala P. Characteristics of trophoblast cells migrating from first trimester chorionic villus explants and propagated in culture. Placenta 1995; 16: 413–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Patel L, Pienta KJ. CC chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) promotes prostate cancer tumorigenesis and metastasis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2010; 21: 41–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez-Dunddel D, Pan F, Zeng Q, Gorbounov M, Albesiano E, Fu J et al. STAT3 regulates arginase-I in myeloid-derived suppressor cells from cancer patients. J Clin Investig 2013; 123: 1580–1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kämmerer U, Eggert AO, Kapp M, McLellan AD, Geijtenbeek TB, Dietl J et al. Unique appearance of proliferating antigen-presenting cells expressing DC-SIGN (CD209) in the decidua of early human pregnancy. Am J Pathol 2003; 162: 887–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croxatto D, Vacca P, Canegallo F, Conte R, Venturini PL, Moretta L et al. Stromal cells from human decidua exert a strong inhibitory effect on NK cell function and dendritic cell differentiation. PLoS One 2014; 9: e89006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler-Heitbrock L, Ancuta P, Crowe S, Dalod M, Grau V, Hart DN et al. Nomenclature of monocytes and dendritic cells in blood. Blood 2010; 116: e74–e80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntire RH, Ganacias KG, Hunt JS. Programming of human monocytes by the uteroplacental environment. Reprod Sci 2008; 15: 437–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa N. IDO expression on decidual and peripheral blood dendritic cells and monocytes/macrophages after treatment with CTLA-4 or interferon-γ increase in normal pregnancy but decrease in spontaneous abortion. Mol Hum Reprod 2006; 11: 865–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cupurdija K, Azzola D, Hainz U, Gratchev A, Heitger A, Takikawa O et al. Macrophages of human first trimester decidua express markers associated to alternative activation. Am J Reprod Immunol 2004; 51: 117–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atay S, Gercel-Taylor C, Suttles J, Mor G, Taylor DD. Trophoblast-derived exosomes mediate monocyte recruitment and differentiation. Am J Reprod Immunol 2011; 65: 65–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldo PB, Racicot K, Craviero V, Guller S, Romero R, Mor G. Trophoblast induces monocyte differentiation into CD14+/CD16+ macrophages. Am J Reprod Immunol 2014; 72: 270–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talmadge JE, Gabrilovich DI. History of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Nat Rev Cancer 2013; 13: 739–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Highfill SL, Rodriguez PC, Zhou Q, Goetz CA, Koehn BH, Veenstra R et al. Bone marrow myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) inhibit graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) via an arginase-1-dependent mechanism that is up-regulated by interleukin-13. Blood 2010; 116: 5738–5747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luther SA, Cyster JG. Chemokines as regulators of T cell differentiation. Nature Immunol 2001; 2: 102–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y-Y, He X-J, Guo P-F, Du M-R, Shao J, Li M-Q et al. The decidual stromal cells-secreted CCL2 induces and maintains decidual leukocytes into Th2 bias in human early pregnancy. Clin Immunol 2012; 145: 161–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nefedova Y, Huang M, Kusmartsev S, Bhattacharya R, Cheng P, Salup R et al. Hyperactivation of STAT3 is involved in abnormal differentiation of dendritic cells in cancer. J Immu: 464–474. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nefedova Y, Nagaraj S, Rosenbauer A, Muro-Cacho C, Sebti SM, Gabrilovich DI. Regulation of dendritic cell differentiation and antitumor immune response in cancer by pharmacologic-selective inhibition of the janus-activated kinase 2/signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 pathway. Cancer Res 2005; 65: 9525–9535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin H, Zhang C, Herrmann A, Du Y, Figlin R, Yu H. Sunitinib inhibition of Stat3 induces renal cell carcinoma tumor cell apoptosis and reduces immunosuppressive cells. Cancer Res 2009; 69: 2506–2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.