Abstract

Anastomotic leakage is an unfortunate complication of colorectal surgery. This distressing situation can cause severe morbidity and significantly affects the patient’s quality of life. Additional interventions may cause further morbidity and mortality. Parenteral nutrition and temporary diverting ostomy are the standard treatments of anastomotic leaks. However, technological developments in minimally invasive treatment modalities for anastomotic dehiscence have caused them to be used widely. These modalities include laparoscopic repair, endoscopic self-expandable metallic stents, endoscopic clips, over the scope clips, endoanal repair and endoanal sponges. The review aimed to provide an overview of the current knowledge on the minimally invasive management of anastomotic leaks.

Keywords: Minimally invasive surgery, Anastomotic leak, Colorectal surgery

Core tip: Anastomotic leakage is the most feared complication of colorectal surgery, leading to significant patient morbidity and mortality. Its incidence is 3%-6%, even in experienced hands. Despite the high prevalence of this condition, there is no consensus on the proper management of anastomotic leaks. In this review, we summarize and discuss the current knowledge on minimally invasive treatment strategies for anastomotic leakage after colorectal surgery.

INTRODUCTION

Anastomotic leak (AL) following colorectal surgery is a feared complication with an incidence of 3%-6%, even in experienced hands[1]. ALs can cause severe morbidity, cost, and affect the patient’s quality of life. Moreover, major additional interventions may lead to further morbidity and mortality (with of 10%-20%)[2]. Currently, technological developments in minimally invasive treatment modalities for ALs have caused them to be used widely. These modalities include laparoscopic repair, endoscopic self-expandable metallic stents (SEMS), endoscopic clips, over the scope clips (OTSCs), endoanal repair and endoanal sponges.

In this review, we summarize and discuss the current knowledge on minimally invasive treatment strategies for ALs after colorectal surgery.

LAPAROSCOPIC REPAIR AND MANAGEMENT

In the last two decades, there have been significant developments in the field of minimally invasive surgical procedures, including laparoscopy. Despite these advances in laparoscopic instrumentation and techniques, the laparoscopic management of AL after colorectal surgery is still under debate.

A retrospective study by Cuccurullo et al[3] reported that AL was the most common finding (57.1%) at laparoscopic re-intervention. In this study, 91.7% of cases were managed by anastomotic repair, peritoneal lavage and temporary diverting ostomy. Only 8.3% of ALs required a Hartmann’s procedure because of gross fecal contamination. The conversion rate to open surgery was 5.6%, because of extensive colonic ischemia and generalized peritonitis. Lee et al[4] also reported an 8.2% conversion rate, and all ALs were treated with ileostomy/colostomy, with or without anastomotic repair. They compared the results of open and laparoscopic management, and observed significantly shorter hospital stay, lower 30-d postoperative morbidity and complication, and improved stoma closure rate in the laparoscopic group. In other studies by Wind et al[5] and Vennix et al[6], the morbidity rate, hospital stay, intensive care unit admission, and incisional hernia rate were reduced in the laparoscopic re-intervention group. Furthermore, re-laparoscopy can be used as a diagnostic tool if clinical concerns exist, despite an adjunctive diagnostic imaging with reported diagnostic accuracy between 93% and 100%[7].

Laparoscopic re-intervention is a safe, feasible and effective technique, and can also be considered as a diagnostic option as the first therapeutic approach for evaluating suspected postoperative complications. Today, many studies encourage the use of laparoscopy for the treatment of complications following minimally invasive colorectal surgery in skilled hands.

ENDOSCOPIC SEMS, AND OTHER STENTS

The use of colonic stents has significantly evolved over the last decades as an alternative method of converting emergency surgery for obstructing colorectal cancers to safer definitive elective surgery or as palliative treatment for inoperable malignant colorectal strictures, with high success rates[8]. Moreover, the application of colonic stents has gained increasing attention in recent years for postoperative complications following colorectal surgery, including ALs, fistulas and perforations (Figure 1). In particular, smaller ALs that are not associated with severe sepsis might benefit from colonic stenting after laparoscopic peritoneal lavage and drainage, and fashioning of stoma[9]. By contrast, some authors considered that endoscopic stenting could be utilized in patients with or without a stoma, in combination with percutaneous drainage of infected intraabdominal collections[10].

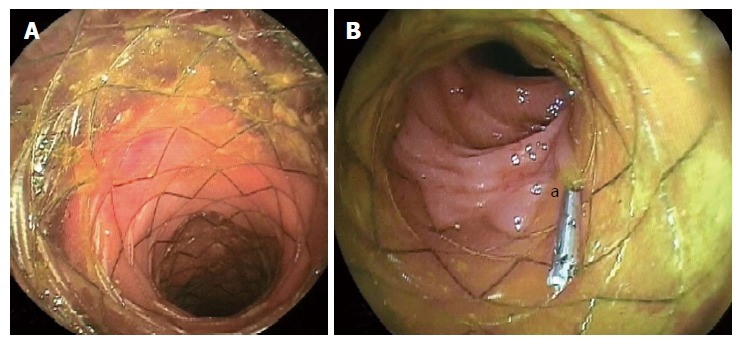

Figure 1.

Self-expanding metal stent for anastomosis leakage. A: Endoscopic image after deployment of the stent; B: Stent with clip (a) at the proximal end.

Several types of intestinal stent are available, such as a SEMS (uncovered, partially or fully covered), a self-expanding plastic stent, and a biodegradable stent. Colonic stent-related complications include stent migration, anorectal pain, incontinence, perforation, rectal bleeding and stent obstruction[9,11]. The stent can only be placed across an end-to-end anastomosis, and the distal end of the stent must be no less than 5 cm proximal to the anal verge[10-12]. Stents placed very distally in the rectum may cause increased rectal pain, tenesmus or fecal incontinence[11-13].

The risk of stent migration is high in the lower gastrointestinal tract because of the increased intestinal motility, and has been reported in 25% to 40% of patients[14-16]. This rate is lower in uncovered or partially covered stents than in biodegradable and fully covered stents[9,10,12]. Migration has been also described when large-diameter stents have been used[11,14]. However, the use of a partially covered SEMS prevents migration and allows for tissue in-growth; however, its removal is technically difficult[11,12]. Clips or endoscopic suturing are alternative methods to anchor the stent in place and to reduce migration risk[14] (Figure 1B). Optimal timing of stent removal is controversial. If possible, stents should be removed after adequate healing of the dehiscence is confirmed endoscopically and following resolution of clinical signs and symptoms[16].

A recent study found that SEMS application was successful in 86% of 22 patients with ALs following colorectal surgery[13]. In that study, fully covered SEMS were used in 19 patients and uncovered SEMS in three patients. Stent migration occurred in only one of the 22 patients (4.5%); this patient was in the covered stent group and stent migrated 6 mo after placement. Most of the patients complained of incontinence after placement of the stent, which regressed spontaneously after an average of 14 wk.

Recent advances and innovations in stent technology have led to the development expandable polydioxanone biodegradable stents as an effective alternative treatment of AL following colorectal surgery. The biodegradable stent does not to be removed, which can decrease mucosal hyperplastic reactions and adverse events associated with stent removal, compared with metal stents[9,10,12,14].

Based on limited data, stent placement appears to be an alternative therapeutic option for selected patients with AL after colorectal surgery when performed by skilled endoscopists. Migration and cost are the major limitations of these stents.

ENDOSCOPIC CLIPS

Application of clips to approximate the edges of the leaking anastomosis is one of the endoscopic management techniques. Standard endoclips, which are used to control small perforations and bleeding, may be used to close an AL; however, the low closure of force of these clips limit their use for more scarred, fibrotic and irradiated tissues.

The first clip was manufactured by the Olympus Corporation (Japan) in 1995. Thereafter, a disposable preloaded version of this clip, known as Quickclips® (Olympus Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), has gained popularity. Thereafter, OTSC (Ovesco Endoscopy, endoscopy, Tubingen, Germany) were introduced; and in 2011, Cook Medical from United States produced the Instinct™ Endoscopic Hemoclip.

The OTSC is the most preferred clips to control AL. This clip is made of super-elastic nitinol, which is a biocompatible and magnetic resonance imaging-safe material, and has the benefit of a larger clip area with increased compression. Firstly, Kirschniak et al[17] published their successful results using OTSC in 11 patients with bleeding or iatrogenic perforations. Application of OTSCs for leaks has since become popular. Weiland et al[18] reported a general success rate of 84.6%. Arezzo et al[19] used OTSCs for colorectal surgery on 14 patients with leaks no larger than 15 mm (maximum diameter), and without luminal stenosis and abscess. Their success rate was also 86%. Occasionally, the first attempt fails, but repeated attempts will be successful in order to close the dehiscence of AL[20].

Favorable results with OTSCs are obtained in the absence of fibrotic tissue. Closure of chronic leaks and fistulas seems to be a considerable challenge and may decrease the success rate[21]. Contrastingly, OTSCs have significant cost benefits compared with ileostomy, and achieve full-thickness wall closure. Moreover, they require a shorter hospital stay and avoid temporary ileostomy[19]. OTSCs can close defects up to 30 mm[22]. Application of multiple clips may be possible for larger defects; however, there is limited experience of it[23,24].

ENDOSCOPIC VACUUM-ASSISTED CLOSURE

Negative pressure wound therapy or vacuum-assisted closure is now a well-established treatment modality for chronic and difficult to heal wounds. Recently, this minimally invasive method has been proposed as an effective approach to manage ALs after colorectal surgery, with success rates ranging from 56.6% to 100%[25-29]. In the original technique, after the presence of the abscess cavity is confirmed by diagnostic colonoscopy, the enteric and purulent contents are aspirated and then irrigated. Finally, an open pored, polyurethane sponge with an attached evacuation tube connected to a drainage sys–tem is inserted via an introducer sleeve that is fitted over an endoscope and placed through the dehiscence and into the pelvic cavity[10,12,16,25].

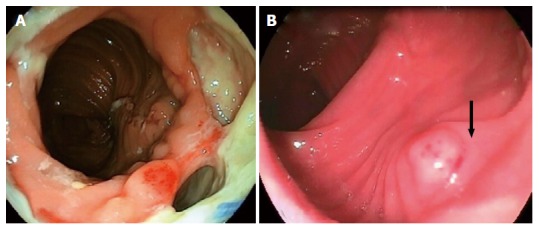

The endo-sponge continuously removes secretions, improves microcirculation, and therefore induces granulation formation in the defect. It also aids closure of the pelvic cavity by the application of negative pressure of 125 mmHg[26] (Figure 2). One disadvantage of this method is the requirement to change the sponge every 2-4 d until the abscess cavity has regressed[25,28,29]. However, this treatment is more effective at shrinking cavities, especially when used within 6 wk after the AL[10,30]. It should be noted that generalized peritonitis is not an indication for endo-sponge therapy[12,25,29]; and the overall complication rates are around 20%, mainly comprising anastomosis stenosis, recidivate abscess and fistula[26].

Figure 2.

Endoscopic appearance of anastomotic leakage. A: Anastomotic leak with a cavity before endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure therapy; B: The same cavity covered with granulation tissue (black arrow) three weeks after vacuum therapy was initiated.

In 2008, a large series of endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure therapy cases was reported by Weidenhagen et al[25]. In that study, definitive closure of the cavity was achieved in 28 of the 29 patients (96.6%) over a mean treatment period of 34 d (range 4-79 d). In a recent review, Strangio et al[26] found that complete healing of the cavity was achieved in near 95% of cases overall, following a median of 30 d of treatment and the performance of a median of 11 sessions. The authors emphasized that endo-sponge applications might be safely performed in patients with or without a diverting ileostomy. Weidenhagen et al[25] reported that four patients were treated without the construction of a diverting stoma. Similarly, Glitsch et al[28] reported successful endoscopic transanal vacuum-assisted rectal drainage for AL after rectal resection in 16 of 17 patients (94.1%). They also found that the closure time was directly dependent on the cavity size, distance from anastomosis to the anal verge and the patient’s age. Patients with anastomoses that were 6 cm or less from the anal verge, who were elderly (aged over 62 years), and had a cavity measuring 5 cm × 6 cm or more had considerably longer healing times.

Endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure therapy seems a safe and useful therapeutic option for the local and minimally invasive management of AL after colorectal surgery, with high success rates. However, further prospective clinical studies with randomized data and larger numbers of patients are needed to clarify the beneficial effects of endo-sponge therapy in patients with anastomotic insufficiency.

TRANSANAL REPAIR

Transanal repair is another preferred method for treatment of delayed ALs. Candidates for this method should have a documented persistent sinus or cavity diagnosed by contrast enema, without any evidence of recurrence and co-morbidity. Transanal repair uses a primary repair or repair with flap, especially for sinus formation of AL. The flap should be prepared with skin or mucosa, although there is limited supporting data concerning this in the literature. Endorectal flap advancement is well described in ileorectal anastomotic sinuses. Blumetti et al[31] published their two-center study in 2012 and reported six transanal repairs for five patients with an 80% success rate.

In 2015, Brunner et al[32] reported two consecutive patients managed by transanal primary repair and irrigation of the abdominal cavity for AL after single incision laparoscopic sigmoid resection for stage II/III diverticulitis. They mentioned no residual leaks, no anastomotic strictures and normal rectal functions.

A summary of some recent successful studies managed minimally invasively after anastomotic leakage and the outcomes in SEMS, OTSC, vacuum-assisted closure and transanal repair is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Recent successful studies managed minimally invasively after acute or chronic anastomotic leak

| Ref. | Year | Cases | Procedure | Gender (F/M) | Age (yr) | Previous diagnose or treatment | Success n (%) | Failure or complications n (%) | Follow-up |

| Lamazza et al[13] | 2015 | 22 | SEMS | 11/11 | 68 | Anterior resection (all) Neoadjuvant (21) | 19 (86.4) | Failure: 3 (13.6) Stent migration: 1 (4.5) | 18-42 mo |

| Arezzo et al[19] | 2012 | 14 | OTSC | 8/6 | 68.5 | Anterior resection (12) Colostomy closure (1) Right hemicolectomy (1) | 12 (85.7) | 1 patient needed further surgery | 4 mo |

| Sulz et al[20] | 2014 | 6 | OTSC | 1/5 | 66.5 | Colorectal resection | 5 (83.3) | Failure: 1 (Succeeded with 2nd OTSC) | N/A |

| Weidenhagen et al[25] | 2008 | 29 | VAC | 5/24 | 66.7 | Rectal cancer (22) Rectosigmoidal cancer (3) Large rectal adenoma (2) Diverticulitis (1) Endometrial cancer infiltration (1) | 28 (96.6) | 1 (Hartmann’s procedure) | VAC duration: 34.4 ± 19.4 d |

| Blumetti et al[31] | 2011 | 5 | Transanal repair | N/A | 52 | Coloanal anastomosis (4) Colorectal anastomosis (1) | 4 (80) | Failure: 1 (20) | Time to repair: 8-15 mo |

F/M: Female/male; SEMS: Self-expandable metallic stent; OTSC: Over the scope clip; N/A: Data not available; VAC: Vacuum-assisted closure.

CONCLUSION

Anastomotic leaks continue to be critical and life-threatening events, with considerable morbidity and mortality. Patients with ALs are often critically ill, and non-operative management strategies should be the preferred first-line approach. Currently, minimally invasive treatment options are a promising alternative to surgical treatment, with satisfactory outcomes for the management of ALs. Nevertheless, there is a need for further, large, high quality, randomized, controlled trials on the long-term outcome, function and clinical efficacy of these different techniques.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Turkey

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Peer-review started: May 4, 2016

First decision: July 4, 2016

Article in press: July 22, 2016

P- Reviewer: Segre D, Tebala GD, Virk JS S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Stewart G E- Editor: Li D

References

- 1.Kingham TP, Pachter HL. Colonic anastomotic leak: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:269–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slieker JC, Komen N, Mannaerts GH, Karsten TM, Willemsen P, Murawska M, Jeekel J, Lange JF. Long-term and perioperative corticosteroids in anastomotic leakage: a prospective study of 259 left-sided colorectal anastomoses. Arch Surg. 2012;147:447–452. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuccurullo D, Pirozzi F, Sciuto A, Bracale U, La Barbera C, Galante F, Corcione F. Relaparoscopy for management of postoperative complications following colorectal surgery: ten years experience in a single center. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:1795–1803. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3862-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee CM, Huh JW, Yun SH, Kim HC, Lee WY, Park YA, Cho YB, Chun HK. Laparoscopic versus open reintervention for anastomotic leakage following minimally invasive colorectal surgery. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:931–936. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3755-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wind J, Koopman AG, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Slors JF, Gouma DJ, Bemelman WA. Laparoscopic reintervention for anastomotic leakage after primary laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1562–1566. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vennix S, Abegg R, Bakker OJ, van den Boezem PB, Brokelman WJ, Sietses C, Bosscha K, Lips DJ, Prins HA. Surgical re-interventions following colorectal surgery: open versus laparoscopic management of anastomotic leakage. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2013;23:739–744. doi: 10.1089/lap.2012.0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirshtein B, Domchik S, Mizrahi S, Lantsberg L. Laparoscopic diagnosis and treatment of postoperative complications. Am J Surg. 2009;197:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Hooft JE, van Halsema EE, Vanbiervliet G, Beets-Tan RG, DeWitt JM, Donnellan F, Dumonceau JM, Glynne-Jones RG, Hassan C, Jiménez-Perez J, et al. Self-expandable metal stents for obstructing colonic and extracolonic cancer: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2014;46:990–1053. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1390700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kabul Gürbulak E, Akgün İE, Öz A, Ömeroğlu S, Battal M, Celayir F, Mihmanlı M. Minimal invasive management of anastomosis leakage after colon resection. Case Rep Med. 2015;2015:374072. doi: 10.1155/2015/374072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blumetti J, Abcarian H. Management of low colorectal anastomotic leak: Preserving the anastomosis. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;7:378–383. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v7.i12.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DiMaio CJ, Dorfman MP, Gardner GJ, Nash GM, Schattner MA, Markowitz AJ, Chi DS, Gerdes H. Covered esophageal self-expandable metal stents in the nonoperative management of postoperative colorectal anastomotic leaks. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:431–435. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.03.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smallwood N, Mutch MG, Fleshman JW. In: Steele SR, Maykel JA, Champagne BJ, Orangio GR. Complexities in colorectal surgery: Decision-making and management. New York: Springer, 2014: 277-304 In: Steele SR, Maykel JA, Champagne BJ, Orangio GR, editors. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamazza A, Sterpetti AV, De Cesare A, Schillaci A, Antoniozzi A, Fiori E. Endoscopic placement of self-expanding stents in patients with symptomatic anastomotic leakage after colorectal resection for cancer: long-term results. Endoscopy. 2015;47:270–272. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1391403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dabizzi E, De Ceglie A, Kyanam Kabir Baig KR, Baron TH, Conio M, Wallace MB. Endoscopic “rescue” treatment for gastrointestinal perforations, anastomotic dehiscence and fistula. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2016;40:28–40. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manta R, Caruso A, Cellini C, Sica M, Zullo A, Mirante VG, Bertani H, Frazzoni M, Mutignani M, Galloro G, et al. Endoscopic management of patients with post-surgical leaks involving the gastrointestinal tract: A large case series. Unit Euro Gastroenterol J. 2016:1–8. doi: 10.1177/2050640615626051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rogalski P, Daniluk J, Baniukiewicz A, Wroblewski E, Dabrowski A. Endoscopic management of gastrointestinal perforations, leaks and fistulas. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:10542–10552. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i37.10542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirschniak A, Kratt T, Stüker D, Braun A, Schurr MO, Königsrainer A. A new endoscopic over-the-scope clip system for treatment of lesions and bleeding in the GI tract: first clinical experiences. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:162–167. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiland T, Fehlker M, Gottwald T, Schurr MO. Performance of the OTSC System in the endoscopic closure of gastrointestinal fistulae--a meta-analysis. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2012;21:249–258. doi: 10.3109/13645706.2012.694367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arezzo A, Verra M, Reddavid R, Cravero F, Bonino MA, Morino M. Efficacy of the over-the-scope clip (OTSC) for treatment of colorectal postsurgical leaks and fistulas. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:3330–3333. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sulz MC, Bertolini R, Frei R, Semadeni GM, Borovicka J, Meyenberger C. Multipurpose use of the over-the-scope-clip system (“Bear claw”) in the gastrointestinal tract: Swiss experience in a tertiary center. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16287–16292. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i43.16287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dişibeyaz S, Köksal AŞ, Parlak E, Torun S, Şaşmaz N. Endoscopic closure of gastrointestinal defects with an over-the-scope clip device. A case series and review of the literature. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012;36:614–621. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.von Renteln D, Schmidt A, Vassiliou MC, Rudolph HU, Caca K. Endoscopic full-thickness resection and defect closure in the colon. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1267–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seebach L, Bauerfeind P, Gubler C. “Sparing the surgeon”: clinical experience with over-the-scope clips for gastrointestinal perforation. Endoscopy. 2010;42:1108–1111. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manta R, Manno M, Bertani H, Barbera C, Pigò F, Mirante V, Longinotti E, Bassotti G, Conigliaro R. Endoscopic treatment of gastrointestinal fistulas using an over-the-scope clip (OTSC) device: case series from a tertiary referral center. Endoscopy. 2011;43:545–548. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weidenhagen R, Gruetzner KU, Wiecken T, Spelsberg F, Jauch KW. Endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure of anastomotic leakage following anterior resection of the rectum: a new method. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1818–1825. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9706-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strangio G, Zullo A, Ferrara EC, Anderloni A, Carlino A, Jovani M, Ciscato C, Hassan C, Repici A. Endo-sponge therapy for management of anastomotic leakages after colorectal surgery: A case series and review of literature. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:465–469. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riss S, Stift A, Kienbacher C, Dauser B, Haunold I, Kriwanek S, Radlsboek W, Bergmann M. Recurrent abscess after primary successful endo-sponge treatment of anastomotic leakage following rectal surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4570–4574. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i36.4570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glitsch A, von Bernstorff W, Seltrecht U, Partecke I, Paul H, Heidecke CD. Endoscopic transanal vacuum-assisted rectal drainage (ETVARD): an optimized therapy for major leaks from extraperitoneal rectal anastomoses. Endoscopy. 2008;40:192–199. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuehn F, Janisch F, Schwandner F, Alsfasser G, Schiffmann L, Gock M, Klar E. Endoscopic Vacuum Therapy in Colorectal Surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20:328–334. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-3017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Srinivasamurthy D, Wood C, Slater R, Garner J. An initial experience using transanal vacuum therapy in pelvic anastomotic leakage. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17:275–281. doi: 10.1007/s10151-012-0911-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blumetti J, Chaudhry V, Prasad L, Abcarian H. Delayed transanal repair of persistent coloanal anastomotic leak in diverted patients after resection for rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:1238–1241. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.02932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brunner W, Rossetti A, Vines LC, Kalak N, Bischofberger SA. Anastomotic leakage after laparoscopic single-port sigmoid resection: combined transanal and transabdominal minimal invasive management. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:3803–3805. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4138-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]