Abstract

Gene expression profiling via quantitative real-time PCR is a robust technique widely used in the life sciences to compare gene expression patterns in, e.g., different tissues, growth conditions, or after specific treatments. In the field of plant science, real-time PCR is the gold standard to study the dynamics of gene expression and is used to validate the results generated with high throughput techniques, e.g., RNA-Seq. An accurate relative quantification of gene expression relies on the identification of appropriate reference genes, that need to be determined for each experimental set-up used and plant tissue studied. Here, we identify suitable reference genes for expression profiling in stems of textile hemp (Cannabis sativa L.), whose tissues (isolated bast fibres and core) are characterized by remarkable differences in cell wall composition. We additionally validate the reference genes by analysing the expression of putative candidates involved in the non-oxidative phase of the pentose phosphate pathway and in the first step of the shikimate pathway. The goal is to describe the possible regulation pattern of some genes involved in the provision of the precursors needed for lignin biosynthesis in the different hemp stem tissues. The results here shown are useful to design future studies focused on gene expression analyses in hemp.

Keywords: gene expression, reference genes, Cannabis sativa, cell wall, lignification

1. Introduction

The identification of appropriate reference genes used for normalization and whose expression is not affected by the experimental factors is a crucial step in gene expression studies performed using real-time PCR (a.k.a. quantitative PCR, or RT-qPCR). The choice of unsuitable reference genes can compromise the results and may lead to wrong interpretations of biological phenomena.

The literature is constellated by studies focusing on the selection of reference genes in different plant species, tissues, conditions [1,2,3,4]; a list of potential candidates whose orthologs can be tested in the plant/tissue of choice is usually provided. Several types of software are available to assess the stability of a set of candidate reference genes [5,6,7,8] and a ranking is provided to show those most stable. The comparison of expression patterns in plants subjected to a combination of abiotic stresses [9], or tissues showing strong differences in terms of composition and developmental stage, poses a challenge when data have to be normalized. In these circumstances, if a tissue maximization design is used [10], then reference genes suitable for all the conditions/tissues studied need to be identified. This might require the screening of several candidates, given the heterogeneity of the experimental conditions tested.

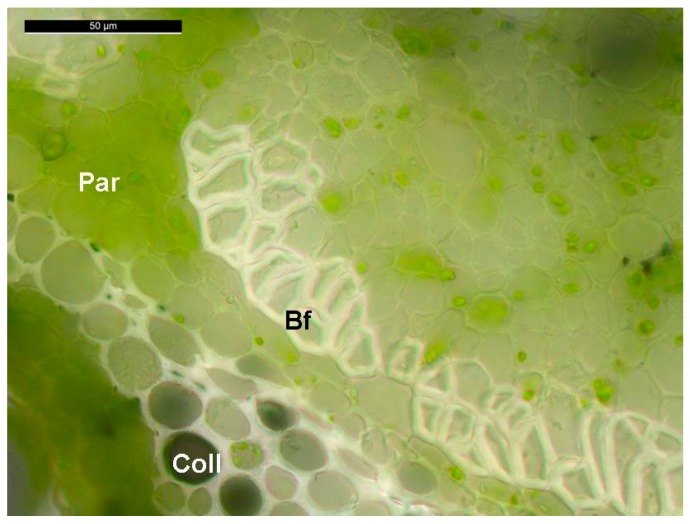

One example of experimental heterogeneity is the study of gene expression in the stems of fibre crops, like textile hemp (Cannabis sativa L.), since they are characterized by tissues differing dramatically in their composition [11]. The stems of hemp are composed of cortical tissues harbouring cellulose-rich sclerenchyma fibres (which mechanically support the phloem, a.k.a. bast fibres) and a woody core (often referred to as hurd or shiv). These tissues can be easily isolated, since the cortex can be peeled off and subsequently processed to separate the bast fibres from the epidermis/parenchyma/collenchyma. While the core fibres are lignified and characterized by the typical secondary cell wall layers S1-S2-S3, bast fibres possess a gelatinous layer (G-layer; Figure 1) composed of crystalline cellulose which is similar to that found in tension wood [12]. The G-layer of bast fibres, however, does not exert the same contractile function as in tension wood [13]. It should be noted that hemp stems, unlike the other fibre crop flax (Linum usitatissimum), possess also secondary bast fibres which are shorter and more lignified than primary fibres and originate from the cambium [11].

Figure 1.

Representative cross section of the stem of an adult hemp plant (1.5 months) showing the bast fibres with the typical G-layer. Bf: bast fibres; Par: parenchyma; Coll: collenchyma.

Besides the differences in tissue composition, hemp stems additionally show a basipetal lignification gradient: younger internodes at the top are indeed rapidly elongating and the bast fibres show a relatively thin cell wall, while older internodes at the base of the stem cease elongation, synthesize a thick secondary cell wall and are more lignified. The transition from elongation to cell wall thickening is marked by an empirically-determined point, called the “snap point” [14].

The heterogeneous lignification of its stem tissues makes hemp very interesting as a model to study cell wall-related processes: the inner/outer tissues of the same internode, as well as those collected from younger/older internodes along the stem, can be studied to carry out high-throughput gene expression profiling. Such studies allow addressing molecular questions on, e.g., the regulation of bast fibre cell wall formation and maturation.

Some studies are available on the identification of reference genes in other fibre crops, notably flax (Linum usitatissimum) [15], kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus) [16] and jute (Corchorus capsularis) [17]. These studies on one hand show that care should be taken when choosing the reference genes, as their stability might change depending on the tissue analysed and the treatment studied, and on the other hand they highlight that the different algorithms available for the evaluation of reference genes may not generate an identical ranking list (see Section 2.2).

No specific study focused on reference genes for RT-qPCR data normalization in hemp is yet available to our knowledge. Given the importance of hemp as a multi-purpose crop for different industrial applications, it is desirable to identify candidate reference genes to perform gene expression analyses. In this work we fill this gap by providing a list of candidates suitable for RT-qPCR data normalization in hemp stem tissues (i.e., bast fibres and shivs). Additionally, we validate them by performing an expression profiling of genes involved in the provision of precursors for lignin biosynthesis. More specifically, we chose genes coding for transaldolase isoforms of the pentose phosphate pathway, TRA1 and TRA2, which synthesize erythrose 4-phosphate, and 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase (DHS) 1 and 2, diverting C-skeletons towards the shikimate pathway.

Given the importance of hemp woody and bast fibres in the textile and biocomposite sectors [18], our study is a useful guide for future molecular studies centred on this economically important fibre crop.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Stability of Candidate Reference Genes in C. sativa Stem Tissues

In this study the stability of 12 potential reference genes from textile hemp was studied for RT-qPCR data normalization (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of candidate reference genes used in the study. The details concerning the primer sequences, amplicon length and Tm, PCR efficiency and regression coefficient are given.

| Name | Sequence (5′→3′) | Amplicon Length (bp) | Amplicon Tm (°C) | PCR Efficiency (%) | Regression Coefficient (R2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ActinFwd | TTGCTGGTCGTGATCTTACTG | 148 | 83 | 90.8 | 0.993 |

| ActinRev | GTCTCCATCTCCTGCTCAAAG | ||||

| eTIF4EFwd | AGTGGGAAGATCCTGAATGTGC | 150 | 81 | 95.1 | 0.997 |

| eTIF4ERev | TTGCGACCACACCACAAATC | ||||

| EF2Fwd | ACGCAACAGCTATCAGGAAC | 113 | 80.3 | 92.3 | 0.998 |

| EF2Rev | TGCAAAGACACGACCAAAGG | ||||

| GAPDHFwd | AATCGCAACCCAAACTCTGC | 123 | 81.1 | 99.4 | 0.995 |

| GAPDHRev | AGTGGCCGTTGCTTTAATGG | ||||

| CycloFwd | ACAACATGTCGAACCCCAAG | 106 | 81.4 | 93.8 | 0.998 |

| CycloRev | TCAGCGGTTTTTGGCGTAAC | ||||

| RANFwd | TTTGGAGACTTCAGCACTGG | 129 | 81.8 | 97.8 | 0.998 |

| RANRev | GCAGGGTTACCATTTCCTTG | ||||

| F-boxFwd | TATCGGCGGAGAGATTTGAG | 77 | 78.4 | 99.5 | 0.975 |

| F-boxRev | TAAGCCCTTCCCTTGATTCC | ||||

| ClathrinFwd | TGTCAGTTTTGTGCCACCAG | 139 | 80.3 | 98.3 | 0.998 |

| ClathrinRev | TCCATGCGTGTTCTACCAAG | ||||

| Histone3Fwd | TGAAGAAGCCTCATCGGTTC | 127 | 82.9 | 96.1 | 0.998 |

| Histone3Rev | TCTTGAGCGATTTCCCTGAC | ||||

| TIP41Fwd | TGAACAGTGGGGAGAAAAGC | 144 | 80.3 | 100.2 | 0.989 |

| TIP41Rev | GCTTCCTGTTTCCATCCAAG | ||||

| TubulinFwd | ATAACTGTACTGGGCTTCAAGG | 110 | 84 | 97.5 | 0.999 |

| TubulinRev | CCTGTGGAGATGGGTAAACTG | ||||

| CDPKFwd | GGTGGCTTTGCTTCTCTTTG | 86 | 78.7 | 97 | 0.986 |

| CDPKRev | GTCAAACCCCTTTTCACACC | ||||

| TA1Fwd | TTCGAGAAGTTCCCTCCAAC | 118 | 81.5 | 92.8 | 0.999 |

| TA1Rev | AGCCATATCCACAGCATTCC | ||||

| TA2Fwd | CTAGCAACCCAGCGATTTTC | 126 | 81.3 | 97 | 0.998 |

| TA2Rev | ACCACAAGCTCCCAATATGC | ||||

| DHS1Fwd | TGAGACTTTCCCTCCGATTG | 144 | 84.6 | 96.8 | 0.998 |

| DHS1Rev | TCAGCACAATCTCCACCTTG | ||||

| DHS2Fwd | TATCAAGGCTGTTCGTGGAG | 129 | 81.8 | 103 | 0.997 |

| DHS2Rev | AGGTGCTTTGATGGTGTTCC |

These candidates comprise both well-known, widely-used reference genes (e.g., tubulin, actin, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase GAPDH, the translation elongation factor EF2, the eukaryotic translation initiation factor eTIF4E, cyclophilin Cyclo, the tonoplast intrinsic protein TIP41) and less frequent ones (notably the clathrin adaptor complex, histone3, the small GTP-binding protein RAN, the calcium-dependent protein kinase CDPK and the F-box gene). An analysis of the stability of the 12 candidate reference genes in hemp fibres and shivs was performed with different methods, namely geNormPLUS [5], NormFinder [6], BestKeeper [7], RefFinder [8] and the comparative delta-Ct method [19]. As can be seen in Table 2, the ranking of the candidate reference genes varied among the methods, which is dependent upon the different algorithms used.

Table 2.

Ranking of the 12 candidate reference genes according to the different methods used.

| GeNormPLUS | NormFinder | BestKeeper | Comparative delta-Ct | RefFinder | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Stability Coeff. | Gene | Stability Coeff. | Gene | Stability Coeff. | Gene | Stability Coeff. | Gene | Stability Coeff. |

| Histone3 | 1.22 | Histone3 | 0.812 | Histone3 | 1.58 | Histone3 | 1.678 | Histone3 | 12 |

| EF2 | 1.135 | EF2 | 0.743 | RAN | 1.085 | EF2 | 1.549 | EF2 | 10.462 |

| Actin | 1.061 | Tubulin | 0.579 | Tubulin | 1.059 | Actin | 1.343 | Actin | 8.409 |

| Cyclo | 1.028 | Cyclo | 0.523 | EF2 | 0.926 | GAPDH | 1.335 | Cyclo | 6.701 |

| GAPDH | 0.959 | Actin | 0.518 | Clathrin | 0.926 | Clathrin | 1.33 | Clathrin | 6.447 |

| eTIF4E | 0.857 | Clathrin | 0.504 | eTIF4E | 0.888 | Cyclo | 1.319 | Tubulin | 5.948 |

| TIP41 | 0.798 | TIP41 | 0.502 | F-box | 0.885 | RAN | 1.302 | GAPDH | 5.635 |

| Tubulin | 0.703 | GAPDH | 0.462 | Actin | 0.87 | Tubulin | 1.299 | RAN | 4.461 |

| CDPK | 0.599 | RAN | 0.453 | Cyclo | 0.718 | TIP41 | 1.241 | eTIF4E | 3.742 |

| RAN | 0.503 | Fbox | 0.452 | CDPK | 0.699 | F-box | 1.234 | TIP41 | 2.913 |

| Clathrin | 0.47 | CDPK | 0.272 | GAPDH | 0.681 | eTIF4E | 1.155 | F-box | 2.913 |

| F-box | 0.45 | eTIF4E | 0.257 | TIP41 | 0.601 | CDPK | 1.091 | CDPK | 1.861 |

To identify the most appropriate subset of genes for RT-qPCR data normalization in hemp stem tissues, the rankings generated by the five methods were compared and we looked for genes classified among the four most stable by at least three different computational techniques. As can be seen in Table 2, CDPK ranked among the four most stable genes with all the methods used. TIP41 had among the lowest values according to NormFinder, Bestkeeper, the comparative delta-Ct method and RefFinder. F-box ranked among the most stable genes by geNormPLUS, the comparative delta-Ct method and RefFinder; likewise, eTIF4E ranked as one of the most stable according to NormFinder, the comparative delta-Ct method and RefFinder.

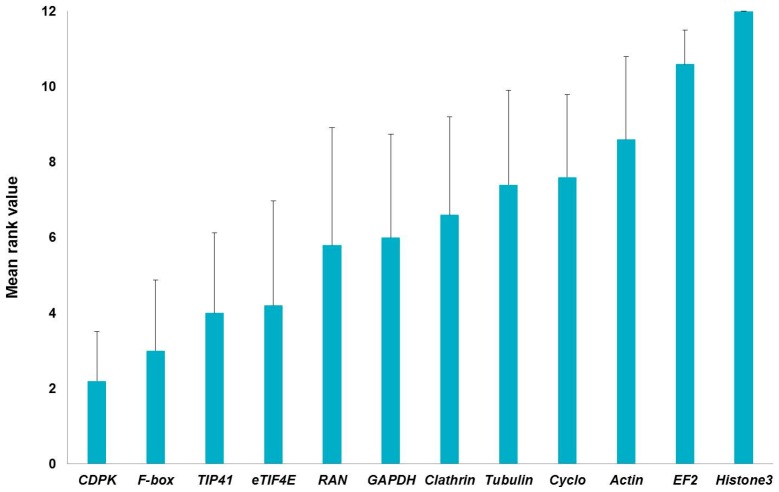

Interestingly, all the methods used to determine the stability of the 12 candidate reference genes agreed in ranking histone3 and EF2 among the four least stable genes; actin and Cyclo were likewise assigned higher scores by three independent methods (Table 2). EF2 was found to be amongst the least stable genes in the stems of another fibre crop, i.e., flax [15]: this might indicate that great variability in its expression is present in the different stem tissues (bast fibres and shivs) of fibre crops. We generated a graph (Figure 2) showing the global stability values by assigning a number (from 1 to 12, where 1 is the most stable and 12 the least stable) to the stability coefficients of Table 2 and by averaging them. As can be seen in Figure 2, the higher stabilities of CDPK, F-box, TIP41, eTIF4E are confirmed, when both stem tissues are considered together.

Figure 2.

Global ranking of the reference genes relative to hemp hurds and bast fibres generated by assigning a number (from 1 to 12) to the stability coefficients (shown in Table 2) and by averaging them. Error bars refer to the standard deviation.

On the basis of the above-mentioned stability rankings, it is here proposed to include CDPK, TIP41, F-box and eTIF4E in the screening of reference genes for expression studies focused on hemp stem tissues. Clearly, their suitability in a given experimental set-up has to be checked prior to performing data normalization.

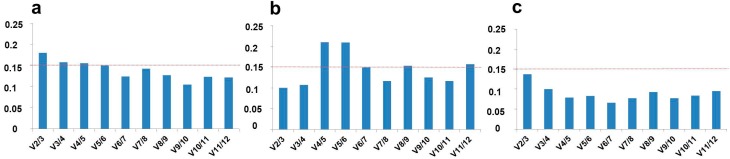

2.2. Optimal Number of Reference Genes in C. sativa Stem Tissues

Hemp stem tissues are characterized by evident differences in composition: the core is woody, while the bast fibres are cellulosic and poor in lignin [11]. It should be underlined that, particularly in expression studies on different tissues, it is necessary to determine the appropriate number of reference genes for a correct normalization. The software geNormPLUS estimates the optimal number of reference genes to use in a specific experimental set-up: this is quite important in studies focused on hemp stem tissues, in the light of their heterogeneity of cell types and of cell wall composition. We therefore used geNormPLUS to calculate the pairwise variation (Vn/Vn+1) between two consecutive normalization factors (NFn and NFn+1) and thus determine the optimal number (and best combination) of reference genes for the normalization of data obtained from hemp stem tissues. The software geNormPLUS recommended the use of five reference genes, namely tubulin, CDPK, RAN, clathrin and F-box for normalization (Figure 3a). The V value falls indeed below the cut-off threshold of 0.15 when all the five reference genes are taken together. These five genes showed the highest expression stability in the different hemp stem tissues (Figure S1).

Figure 3.

Optimal number of reference genes in hemp stem tissues as computed by geNormPLUS. Pairwise variation (Vn/Vn+1) for (a) stem tissues; (b) bast fibres only; and (c) core only. The red dotted line represents the threshold (0.15).

The high heterogeneity of cell types (core with a parenchymatic pith, xylem vessels and fibres; cortex with extraxylary phloem fibres) and cell wall composition most likely explains the need of using five reference genes to normalize the RT-qPCR data. To verify this, the pairwise variation for the two tissues was calculated separately. As can be seen in Figure 3b,c, in both cases two reference genes (EF2/actin for the bast fibres and CDPK/tubulin for the shivs) were sufficient to normalize the data. It should be noted that EF2, actin and tubulin ranked among the least stable genes in the global ranking (Figure 2). In this respect it is not surprising that less stable genes in total stem tissues perform better when a specific tissue type is considered. For example a study on flax revealed that five Eukaryotic translation initiation factor genes were less stable when several tissues were considered together (stems, leaves, roots, flowers), but ranked among the most stable when specific tissue types were taken into account [15]. These results and ours highlight that, when working with heterogeneous biological samples (as is the case of fibre crop stems), it may be necessary to select different reference genes.

2.3. Validation of the Reference Genes in Hemp Stem Tissues

In order to validate the hemp stem tissues reference genes, as suggested by geNormPLUS, the expression of four genes belonging to pathways providing metabolic precursors for the biosynthesis of aromatic amino acids and, more comprehensively, for important plant secondary metabolites, was analysed. These genes are transaldolase 1 and 2 (TRA1, TRA2, hemp orthologs of At1g12230 and At5g13420) and 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase 1 and 2 (DHS1, DHS2, hemp orthologs of At4g45420 and At4g33510). These genes have been chosen because of their connection with lignin deposition and their reported roles in regulatory aspects of the lignification process (a STRING network analysis, showing the putative interactions in biological processes, is shown in Figure S2).

TRA1 and TRA2 are involved in the regenerative phase of the pentose phosphate pathway: they catalyse the formation of erythrose 4-phosphate, a central metabolite in its turn shunted to the production of aromatic amino acids via the shikimate pathway [20].

In Arabidopsis thaliana two genes coding for TRA are present, TRA1-At1g12230 and TRA2-At5g13420; in C. sativa two orthologs are present as well (contig numbers in Table S1). Although located quite early in the metabolic branch leading to the provision of C-skeletons for aromatic acid biosynthesis, TRA2 was shown to have a specific role in lignification [21]: the stems of Arabidopsis tra2 mutants had indeed lower lignin content and showed a higher S/G ratio.

DHS catalyses the first step of the shikimate pathway, which is crucial in shunting a relevant portion of fixed C towards the synthesis of different important metabolites [22]. The enzyme performs a condensation of phosphoenolpyruvate with erythrose 4-phosphate to produce 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate. Three isoforms are present in Arabidopsis (DHS1-At4g39980, DHS2-At4g33510 and DHS3-At1g22410), however in hemp only two contigs were retrieved (Table S1). Notably, two isoforms were also found in jute (Corchorus capsularis), one of which (called CcDAHPS2) was upregulated at early growth stages in the bast fibres of a developmental mutant (deficient lignified phloem fibre, dlpf) [23]. In A. thaliana, DHS1 was shown to be induced by wounding and Pseudomonas syringae attack [24], which are processes involving changes in lignin deposition (“defence lignin” synthesis for example) [25].

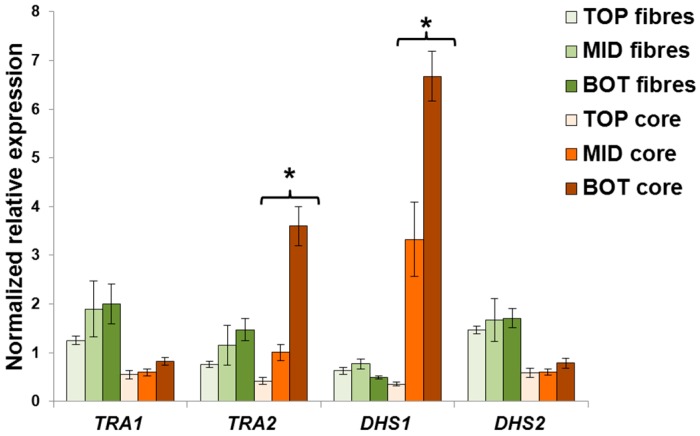

In C. sativa a differential expression of TRA2 and DHS1 was observed in the core tissue collected at the top, middle and bottom of the stems (Figure 4), while no statistically relevant changes in these genes were obtained in the bast fibres. TRA1 and DHS2 show a more constitutive-level of expression among the different stem heights for each tissue considered, although their expression in bast fibres was higher as compared to the core (Figure 3; the difference between the bottom region of the fibres and the core was however not significant for TRA1). Intriguingly, TRA2 and DHS1 genes were strongly upregulated in the bottom region of the stem. This is expected, since a higher shunt of C-skeletons for the synthesis of secondary metabolites linked to lignification is required in the older regions of the hemp stem. Therefore, these results show that two different clusters of genes involved in stem tissue development exist in hemp and that they are differentially regulated in order to play different functions.

Figure 4.

Expression analysis of TRA1, TRA2, DHS1 and DHS2 in the different stem tissues of C. sativa. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean (n = 4). Stars indicate statistically significant values at the one-way ANOVA test (* p < 0.05).

It is possible to propose a role in lignification for TRA2 and DHS1 and a potential bast fibre-related function for TRA1 and DHS2 (their expression is higher in the bast fibres as compared to the hurds, Figure 4). This hypothesis is supported by previous studies in which the maize TRA1 ortholog was shown to sustain basal metabolism and starch synthesis [26], but the total occurrence and presence of TRA activity is related to plant defence mechanisms involving the synthesis of secondary metabolites. It is worth noting that one of the fastest responses to pathogen attack in plants is programmed cell death and lignification of wounded tissues [27].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

A fibre-variety of hemp (Cannabis sativa cv. Santhica 27) was studied in this work. Plants were grown as described in [25]. Four biological replicates, each composed of a pool of 13 plants, were used in this study. After six weeks of growth, samples were taken along three stem regions localized at different heights with respect to the snap point. The “TOP” segment corresponds to the internode right below the apex of the plants, the “MID” (middle) segment is the internode which contains the snap point and the “BOT” (bottom) segment is located two internodes below the “MID” sample. A segment of 2.5 cm was collected from the middle of each internode to avoid too much variation in gene expression, due to the varying developmental stages of the cell types. Fibres were separated from the parenchyma/collenchyma cortical tissues by gently pressing the collected stem peels in 80% ethanol with a pestle, as described in [28]. The fibres were then quickly blotted dry using autoclaved wipers (WypAll, Kimberley-Clark, Muller & Wegener, Luxembourg, Grand Duchy of Luxembourg) and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. The core of the stem segments was directly plunged in liquid nitrogen.

3.2. Gene Identification and Primer Design

The twelve reference genes were retrieved at the Medicinal Plant Genome Resource (http://medicinalplantgenomics.msu.edu/index.shtml; Table S1) by blasting the reported nucleotide sequences in other plant species. Specific gene primers were designed using Primer3Plus (http://www.bioinformatics.nl/cgi-bin/primer3plus/primer3plus.cgi) and checked using the OligoAnalyzer 3.1 tool from Integrated DNA technologies (http://eu.idtdna.com/calc/analyzer). Primer efficiencies were calculated by RT-qPCR using six serial dilutions of cDNA (25, 5, 1, 0.2, 0.04, 0.008 ng/μL). The primer sequences, their corresponding amplicon length and Tm, the amplification efficiencies and regression coefficients are indicated in Table 1. The alignment of the selected reference genes (Figure S3) with the orthologs from hop (Humulus lupulus) [29], marijuana (Purple Kush) [30] and flax (L. usitatissimum) was carried out using ClustalOmega (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/). The hop sequences were retrieved by blasting (BLASTN) the hemp nucleotide sequences at http://hopbase.cgrb.oregonstate.edu/blast. The flax sequences were obtained by blasting (BLASTX) the hemp nucleotide genes at https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html. The C. sativa (Purple Kush, marijuana) sequences were obtained by carrying out a BLAT analysis at http://genome.ccbr.utoronto.ca/cgi-bin/hgBlat?command=start&org=C.+sativa& db=canSat3&hgsid=78813.

3.3. RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis and RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted using a modified CTAB extraction protocol combined with the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Leusden, The Netherlands) [28] according to the manufacturer’s instructions (including digestion with DNase). The RNA concentration and quality were measured for each sample by using a Nanodrop ND-1000 (Thermo Scientific, Villebon-sur-Yvette, France) and a 2100 Bioalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA), respectively. In case of 230 nm contamination, samples were cleaned with a precipitation using ammonium acetate (NH4OAc) and a subsequent wash in ethanol (1/10 volume of NH4OAc in 2.5 volumes of 100% cold ethanol, incubation 60 min at −20 °C, centrifugation at 12,000× g for 20 min at 4 °C, wash with 1.5 mL 75% cold ethanol, centrifugation at 12,000× g for 5 min at 4 °C, air-drying and re-suspension of the pellet in 20 μL of RNase-free water).

The extracted RNA was retrotranscribed into cDNA using the ProtoScript II reverse transcriptase (New England Biolabs, Leiden, The Netherlands) and random primers, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The synthesized cDNA was diluted to 2 ng/μL and used for the RT-qPCR analysis in 384-well plates. An automated liquid handling robot (epMotion 5073, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) was used to prepare the 384-well plates. The RT-qPCR reactions were set up and run according to [31]. To check the specificity of the amplified products, a melt curve analysis was performed. The expression of the TRA1, TRA2, DHS1, DHS2 genes was calculated using qBasePLUS [10] (version 2.5, Biogazelle, Ghent, Belgium) by using the reference genes indicated by the geNormPLUS analysis. Statistics were performed using a one-way ANOVA, as implemented in qBasePLUS.

4. Conclusions

In this study, 12 candidate reference genes were analysed to test their stability and we validate their use in data normalization on hemp stems. The data shown highlight that it may be necessary to select different reference genes when heterogeneous biological samples are studied, as is the case of the contrasting hemp stem tissues. The studied reference genes can not only be used on textile hemp varieties, but also represent candidates to test on oil and drug Cannabis varieties. Additionally, the 12 reference genes here reported can eventually be tested in expression studies focused on close plant species, as for example the Cannabaceae member H. lupulus, given the overall sequence homology (Figure S3). The expression analysis of genes involved in the non-oxidative phase of the pentose phosphate pathway and the shikimate pathway, notably TRA1 and TRA2, DHS1 and DHS2 have also been studied. It was possible to identify isoforms potentially involved in lignification. Further investigations are required to define the roles of other genes playing in the different cell wall-related processes of the hemp stem: lignification requires a complex network of metabolic pathways and signals, different to those required for bast fibre synthesis. It will be interesting in the future to study them functionally. For example, our study opens up the way to future studies centred on the pentose phosphate pathway, which is a central metabolic pathway for both the primary and secondary plant metabolism. The role of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, a central player in the pathway [32,33,34,35], can be addressed to understand its contribution to the shunt of precursors needed for lignin biosynthesis.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Aude Corvisy and Laurent Solinhac for their technical support. The Fonds National de la Recherche, Luxembourg, (Project CANCAN C13/SR/5774202), is gratefully acknowledged for financial support.

Abbreviations

| RT-qPCR | Real-Time PCR |

| G-layer | Gelatinous layer |

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials can be found at www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/17/9/1556/s1.

Author Contributions

Gea Guerriero conceived and designed the experiments; Lauralie Mangeot-Peter performed the experiments; Gea Guerriero, Lauralie Mangeot-Peter, Sylvain Legay, Sergio Esposito and Jean-Francois Hausman analyzed the data; Gea Guerriero, Lauralie Mangeot-Peter, Sylvain Legay, Sergio Esposito and Jean-Francois Hausman wrote the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

References

- 1.Wu Z.-J., Tian C., Jiang Q., Li X.-H., Zhuang J. Selection of suitable reference genes for qRT-PCR normalization during leaf development and hormonal stimuli in tea plant (Camellia sinensis) Sci. Rep. 2016;6:1556. doi: 10.1038/srep19748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang M., Lu S. Validation of suitable reference genes for quantitative gene expression analysis in Panax ginseng. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:1556. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.01259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peng Y.-L., Wang Y.-S., Gu J.-D. Identification of suitable reference genes in mangrove Aegiceras corniculatum under abiotic stresses. Ecotoxicol. Lond. Engl. 2015;24:1714–1721. doi: 10.1007/s10646-015-1487-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schliep M., Pernice M., Sinutok S., Bryant C.V., York P.H., Rasheed M.A., Ralph P.J. Evaluation of reference genes for RT-qPCR studies in the seagrass Zostera muelleri exposed to light limitation. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:1556. doi: 10.1038/srep17051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vandesompele J., de Preter K., Pattyn F., Poppe B., van Roy N., de Paepe A., Speleman F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3:RESEARCH0034. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersen C.L., Jensen J.L., Ørntoft T.F. Normalization of real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR data: A model-based variance estimation approach to identify genes suited for normalization, applied to bladder and colon cancer data sets. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5245–5250. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pfaffl M.W., Tichopad A., Prgomet C., Neuvians T.P. Determination of stable housekeeping genes, differentially regulated target genes and sample integrity: BestKeeper—Excel-based tool using pair-wise correlations. Biotechnol. Lett. 2004;26:509–515. doi: 10.1023/B:BILE.0000019559.84305.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xie F., Xiao P., Chen D., Xu L., Zhang B. miRDeepFinder: A miRNA analysis tool for deep sequencing of plant small RNAs. Plant Mol. Biol. 2012;80:75–84. doi: 10.1007/s11103-012-9885-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guerriero G., Legay S., Hausman J.-F. Alfalfa cellulose synthase gene expression under abiotic stress: A hitchhiker’s guide to RT-qPCR normalization. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:1556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hellemans J., Mortier G., de Paepe A., Speleman F., Vandesompele J. qBase relative quantification framework and software for management and automated analysis of real-time quantitative PCR data. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R19. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-2-r19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guerriero G., Sergeant K., Hausman J.-F. Integrated -omics: A powerful approach to understanding the heterogeneous lignification of fibre crops. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013;14:10958–10978. doi: 10.3390/ijms140610958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guerriero G., Sergeant K., Hausman J.-F. Wood biosynthesis and typologies: A molecular rhapsody. Tree Physiol. 2014;34:839–855. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpu031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mellerowicz E.J., Gorshkova T.A. Tensional stress generation in gelatinous fibres: A review and possible mechanism based on cell-wall structure and composition. J. Exp. Bot. 2012;63:551–565. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gorshkova T.A., Sal’nikov V.V., Chemikosova S.B., Ageeva M.V., Pavlencheva N.V., van Dam J.E.G. The snap point: A transition point in Linum usitatissimum bast fiber development. Ind. Crops Prod. 2003;18:213–221. doi: 10.1016/S0926-6690(03)00043-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huis R., Hawkins S., Neutelings G. Selection of reference genes for quantitative gene expression normalization in flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:1556. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niu X., Qi J., Chen M., Zhang G., Tao A., Fang P., Xu J., Onyedinma S.A., Su J. Reference genes selection for transcript normalization in kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus L.) under salinity and drought stress. PeerJ. 2015;3:1556. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niu X., Qi J., Zhang G., Xu J., Tao A., Fang P., Su J. Selection of reliable reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR gene expression analysis in Jute (Corchorus capsularis) under stress treatments. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:1556. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guerriero G., Hausman J.-F., Strauss J., Ertan H., Siddiqui K.S. Lignocellulosic biomass: Biosynthesis, degradation, and industrial utilization. Eng. Life Sci. 2016;16:1–16. doi: 10.1002/elsc.201400196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silver N., Best S., Jiang J., Thein S.L. Selection of housekeeping genes for gene expression studies in human reticulocytes using real-time PCR. BMC Mol. Biol. 2006;7:1556. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-7-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herrmann K.M. The shikimate pathway as an entry to aromatic secondary metabolism. Plant Physiol. 1995;107:7–12. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vanholme R., Storme V., Vanholme B., Sundin L., Christensen J.H., Goeminne G., Halpin C., Rohde A., Morreel K., Boerjan W. A systems biology view of responses to lignin biosynthesis perturbations in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2012;24:3506–3529. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.102574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tohge T., Watanabe M., Hoefgen R., Fernie A.R. Shikimate and phenylalanine biosynthesis in the green lineage. Plant Metab. Chemodivers. 2013;4:62. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chakraborty A., Sarkar D., Satya P., Karmakar P.G., Singh N.K. Pathways associated with lignin biosynthesis in lignomaniac jute fibres. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2015;290:1523–1542. doi: 10.1007/s00438-015-1013-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keith B., Dong X.N., Ausubel F.M., Fink G.R. Differential induction of 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase genes in Arabidopsis thaliana by wounding and pathogenic attack. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:8821–8825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moura J.C., Bonine C.A., de Oliveira Fernandes Viana J., Dornelas M.C., Mazzafera P. Abiotic and biotic stresses and changes in the lignin content and composition in plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2010;52:360–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.00892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dieuaide-Noubhani M., Raffard G., Canioni P., Pradet A., Raymond P. Quantification of compartmented metabolic fluxes in maize root tips using isotope distribution from 13C- or 14C-labeled glucose. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:13147–13159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.13147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caillau M., Paul Quick W. New insights into plant transaldolase. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2005;43:1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guerriero G., Mangeot-Peter L., Hausman J.-F., Legay S. Extraction of high quality RNA from Cannabis sativa bast fibres: A vademecum for molecular biologists. Fibers. 2016;4:1556. doi: 10.3390/fib4030023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Natsume S., Takagi H., Shiraishi A., Murata J., Toyonaga H., Patzak J., Takagi M., Yaegashi H., Uemura A., Mitsuoka C., et al. The draft genome of hop (Humulus lupulus), an essence for brewing. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015;56:428–441. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Bakel H., Stout J.M., Cote A.G., Tallon C.M., Sharpe A.G., Hughes T.R., Page J.E. The draft genome and transcriptome of Cannabis sativa. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R102. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-10-r102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Behr M., Legay S., Hausman J.-F., Guerriero G. Analysis of cell wall-related genes in organs of Medicago sativa L. under different abiotic stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015;16:16104–16124. doi: 10.3390/ijms160716104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Esposito S., Guerriero G., Vona V., di Martino Rigano V., Carfagna S., Rigano C. Glutamate synthase activities and protein changes in relation to nitrogen nutrition in barley: The dependence on different plastidic glucose-6P dehydrogenase isoforms. J. Exp. Bot. 2005;56:55–64. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cardi M., Castiglia D., Ferrara M., Guerriero G., Chiurazzi M., Esposito S. The effects of salt stress cause a diversion of basal metabolism in barley roots: Possible different roles for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase isoforms. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2015;86:44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Castiglia D., Cardi M., Landi S., Cafasso D., Esposito S. Expression and characterization of a cytosolic glucose 6 phosphate dehydrogenase isoform from barley (Hordeum vulgare) roots. Protein Expr. Purif. 2015;112:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2015.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Landi S., Nurcato R., de Lillo A., Lentini M., Grillo S., Esposito S. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase plays a central role in the response of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) plants to short and long-term drought. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016;105:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.