Abstract

With a large output of medical literature coming out every year, it is impossible for readers to read every article. Critical appraisal of scientific literature is an important skill to be mastered not only by academic medical professionals but also by those involved in clinical practice. Before incorporating changes into the management of their patients, a thorough evaluation of the current or published literature is an important step in clinical practice. It is necessary for assessing the published literature for its scientific validity and generalizability to the specific patient community and reader's work environment. Simple steps have been provided by Consolidated Standard for Reporting Trial statements, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network and several other resources which if implemented may help the reader to avoid reading flawed literature and prevent the incorporation of biased or untrustworthy information into our practice.

Key words: Allocation concealment, bias, conflict of interest, critical appraisal, randomisation, study design

INTRODUCTION

Critical appraisal

‘The process of carefully and systematically examining research to judge its trustworthiness, and its value and relevance in a particular context’

-Burls A[1]

The objective of medical literature is to provide unbiased, accurate medical information, backed by robust scientific evidence that could aid and enhance patient care. With the ever increasing load of scientific literature (more than 12,000 new articles added every week to the MEDLINE database),[2] keeping abreast of the current literature can be arduous. Critical appraisal of literature may help distinguish between useful and flawed studies. Although substantial resources of peer-reviewed literature are available, flawed studies may abound in unreliable sources. Flawed studies if used to guide clinical decisions may end up with no benefit or at worse result in significant harm. Readers can, thus, make informed decisions by critically evaluating medical literature.

STEPS TO CRITICALLY EVALUATE AN ARTICLE

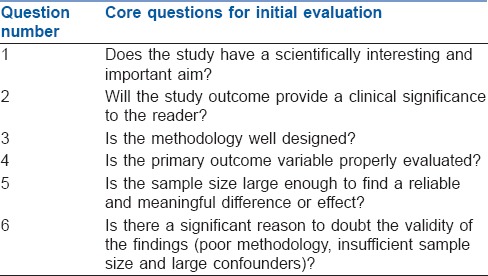

Initial evaluation of an article published in literature should be based on certain core questions. These may include querying what could be the key learning points in the article, about its clinical relevance, if the study has a robust methodology, if the results are reproducible and could there be any bias or conflict of interest [Table 1]. If there are serious doubts regarding any of these steps, the reader could skip the article at this stage itself.

Table 1.

Core questions for initial evaluation of a scientific article

Introduction, methods, results and discussion pattern of scientific literature

Introduction

Evaluate if the need (as dearth of studies on the topic in scientific literature) and the purpose of the study (attempting to find answers to one of the important unanswered queries of clinical relevance) are properly explained with scientific rationale. If the research objective and hypothesis were not clearly defined or the findings of the study are different from the objectives (chance findings), the study outcomes become questionable.

Methods

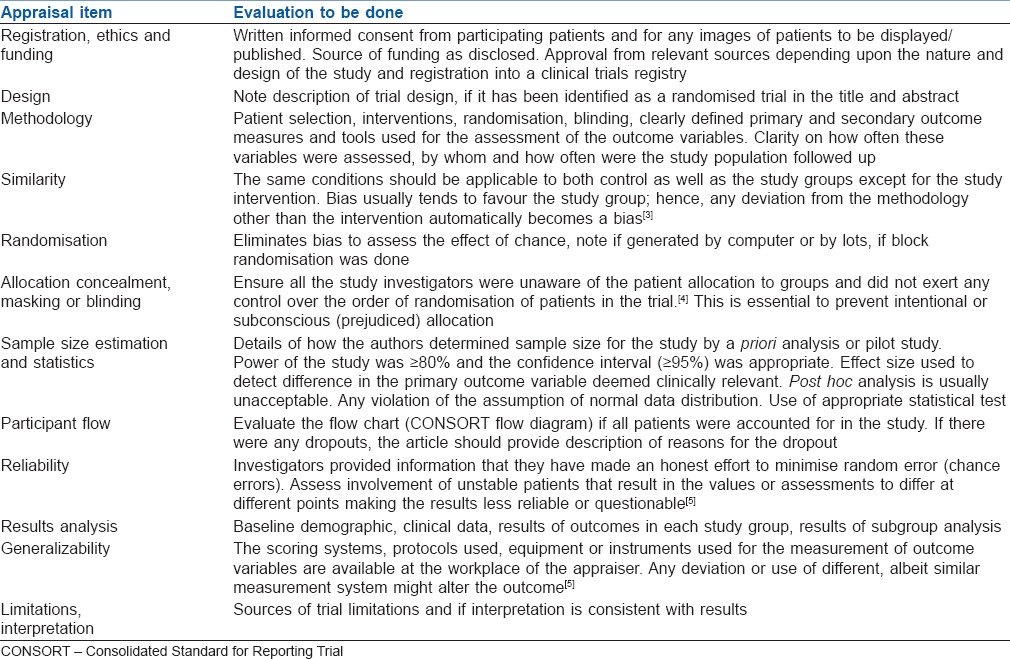

A good working scientific hypothesis backed by a strong methodology is the stepping stone for carrying out a meaningful research. The groups to be involved and the study end points should be determined prior to starting the study. Strong methodology depends on several aspects that must be properly addressed and evaluated [Table 2]. The methodology for statistical analysis including tests for distribution pattern of study data, level of significance and sample size calculation should be clearly defined in the methods section. Data that violate the assumption of normal distribution pattern must be analysed with non-parametric statistical tests. Inadequate sample size can lead to false-negative results or beta error (aide-memoire: beta error is blindness). Setting a higher level of significance, especially when performing multiple comparisons, can lead to false-positive results or alpha error (aide-memoire: alpha error is hallucination). A confidence interval when used in the study methodology provides information on the direction and strength of the effect, in contrast to P values alone, from which the magnitude, direction or comparison of relative risk between groups cannot be inferred. P value simply accepts or rejects the null hypothesis, therefore it must be reported in conjunction with confidence intervals.[6] An important guideline for evaluating and reporting randomised controlled trials, mandatory for publication in several international medical journals, is the Consolidated Standard for Reporting Trial (CONSORT) statement.[7] Other scientific societies such as the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network have devised checklists that may aid in the critical evaluation of articles depending on the type of study methodology.[8,9]

Table 2.

Appraisal elements for robust evaluation of study methodology

Results

The results section should only report the findings of the study, without attempting to reason them out. The total number of participants with the number of those excluded, dropped out or withdrawn from the study should be analysed. Failure to do so may lead to underestimation or overestimation of results.[10] A summary flowchart containing enrolment data could be created as per the CONSORT statement.[5] Actual values including the mean with standard deviation/error or median with interquartile range should be reported. Evaluate for completeness – all the variables in the study methodology should be analysed using appropriate statistical tests. Ensure that findings stated in the results are the same in other areas of the article – abstract, tables and figures. Appropriate tables and graphs should be used to provide the results of the study. Assess if the results of the study can be generalised and are useful to our workplace or patient population.

Although significant positive results from the study are more likely to be accepted for publication (publication bias), remember that high rates of falsely inflated results are demonstrated in studies that had flawed methodology (due to improper or lack of appropriate randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding and/or assessing outcomes through statistical modeling). Further, the publication bias towards studies with positive outcome leads to scientific distortions in the body of scientific knowledge.[11,12]

Discussion and conclusion

The discussion is used to account for or reason out the outcomes of the study, including dropouts and any change in methodology, to comment on the external validity of the study and to discuss its limitations. The authors should report their findings in comparison with that previously published in literature, if the study results added new information to the current literature, if it could alter patient management and if the findings need larger studies for further evaluation or confirmation. When concluding, the interpretation should be consistent with the actual findings. Evaluate if the questions in the study hypothesis were adequately addressed and if the conclusions were justified by the actual data. Authors should also provide limitations of their study and constructive suggestions for future research.

Readers may find useful resources on how to constructively read the published literature at the following resources:

Consolidated Standard for Reporting Trial 2010 for randomised trials – http://www.consort-statement.org

Sign checklists – http://www.sign.ac.uk/methodology/checklists.html

BMJ series of articles – http://www.bmj.com/about-bmj/resources-readers/publications/how-read-paper

Equator network for health research – http://www.equator-network.org

Strobe statement for observational studies – http://www.strobe-statement.org/index.php?id=strobe-home

Care for case reports – http://www.care-statement.org

PRISMA statement for meta-analytical studies and systematic reviews: http://www.prisma-statement.org

Agree – http://www.agreetrust.org

CASP – http://www.casp-uk.net

SUMMARY

Critical appraisal of scientific literature is an important skill to be mastered not just by academic medical professionals but also by those involved in clinical practice. Before incorporating changes in the management of their patients, a thorough evaluation of the current or published literature is a necessary step in practicing evidence-based medicine.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burls A. (What is...? Series) 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: University of Oxford; 2009. [Last accessed on 2016 Jun 19]. What is Critical Appraisal? Available from: http://www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/bandolier/painres/download/whatis/what_is_critical_appraisal.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glasziou PP. Information overload: What's behind it, what's beyond it? Med J Aust. 2008;189:84–5. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strite SA, Stuart ME. Getting started with critical appraisal of medical literature: It is easier than you think. Calif Pharm. 2009;LVI:52–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forder PM, Gebski VJ, Keech AC. Allocation concealment and blinding: When ignorance is bliss. Med J Aust. 2005;182:87–9. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb06584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bialocerkowski A, Klupp N, Bragge P. How to read and critically appraise a reliability article. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2010;17:114–20. [Google Scholar]

- 6.du Prel JB, Hommel G, Röhrig B, Blettner M. Confidence interval or P-value.: Part 4 of a series on evaluation of scientific publications? Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2009;106:335–9. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2009.0335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:698–702. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. [Last accessed on 2016 Jun 19]. Available from: http://www.sign.ac.uk/methodology/checklists.html .

- 9.Strobe Statement. [Last accessed on 2016 Jun 19]. Available from: http://www.strobe-statement.org/index.php?id=available-checklists .

- 10.Lachin JM. Statistical considerations in the intent-to-treat principle. Control Clin Trials. 2000;21:167–89. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(00)00046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.du Prel JB, Röhrig B, Blettner M. Critical appraisal of scientific articles: Part 1 of a series on evaluation of scientific publications. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2009;106:100–5. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2009.0100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kjaergard LL, Villumsen J, Gluud C. Reported methodologic quality and discrepancies between large and small randomized trials in meta-analyses. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:982–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-11-200112040-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]