ABSTRACT

Heat treatment is an important controlling factor that, in combination with other hurdles (e.g., pH, aw), is used to reduce numbers and prevent the growth of and associated neurotoxin formation by nonproteolytic C. botulinum in chilled foods. It is generally agreed that a heating process that reduces the spore concentration by a factor of 106 is an acceptable barrier in relation to this hazard. The purposes of the present study were to review the available data relating to heat resistance properties of nonproteolytic C. botulinum spores and to obtain an appropriate representation of parameter values suitable for use in quantitative microbial risk assessment. In total, 753 D values and 436 z values were extracted from the literature and reveal significant differences in spore heat resistance properties, particularly those corresponding to recovery in the presence or absence of lysozyme. A total of 503 D and 338 z values collected for heating temperatures at or below 83°C were used to obtain a probability distribution representing variability in spore heat resistance for strains recovered in media that did not contain lysozyme.

IMPORTANCE In total, 753 D values and 436 z values extracted from literature sources reveal significant differences in spore heat resistance properties. On the basis of collected data, two z values have been identified, z = 7°C and z = 9°C, for spores recovered without and with lysozyme, respectively. The findings support the use of heat treatment at 90°C for 10 min to reduce the spore concentration by a factor of 106, providing that lysozyme is not present during recovery. This study indicates that greater heat treatment is required for food products containing lysozyme, and this might require consideration of alternative recommendation/guidance. In addition, the data set has been used to test hypotheses regarding the dependence of spore heat resistance on the toxin type and strain, on the heating technique used, and on the method of D value determination used.

INTRODUCTION

Over the last few decades, there has been an increasing demand from consumers in many countries for innovative, ready-to-eat, minimally processed chilled foods such as complete meals, prepared salads and vegetables, pizza, sandwiches, sliced cooked meat, soups, and cakes (1, 2). These products have many desirable properties, such as improved taste, high nutritional value, convenience, and minimal use of additives and preservatives, but simultaneously, they also present challenges with regard to food safety. In the United Kingdom, for example, the microbiological safety of many products relies on a combination of moderate heat treatment (generally in the range of 70 to 90°C), chilled storage (at 8°C or below), a restricted shelf life (typically, a maximum of 42 days), good-quality raw materials, and hygienic manufacturing in the absence of added preservatives (1–3).

Strains of Clostridium botulinum form the highly potent botulinum neurotoxin, and consumption of food containing as little as 30 ng of preformed toxin can cause botulism, a severe paralytic disease (3–6). C. botulinum is a heterogeneous bacterial species that can be separated into four discrete groups, with strains in two groups, proteolytic C. botulinum (group I) and nonproteolytic C. botulinum (group II), being responsible for food-borne botulism (3, 5, 6). Proteolytic C. botulinum has a minimum growth temperature of 10 to 12°C (6) and is a concern for chilled foods following significant temperature abuse. Hazards arising from nonproteolytic C. botulinum are a particular concern for the safety of minimally processed chilled foods, because not only can spores of this pathogen survive mild heat treatments, but they can germinate, giving cells that multiply and form neurotoxin at 3.0 to 3.3°C in 5 to 7 weeks (6, 7). Strains of nonproteolytic C. botulinum produce a single neurotoxin of type B, E, or F, with incomplete neurotoxin gene fragments also reported (8, 9). Mass-produced, minimally processed chilled foods have a very strong safety record, but there have been occasional incidents, most frequently involving type B or E neurotoxin, that have been associated with time and/or temperature abuse during storage or with various home-prepared foods (1, 2, 10–14). The estimated cost of each food-borne botulism case in the United States is ∼$30 million (15).

Considering the increasing consumer demand for chilled foods, the potentially severe adverse health effects, and the serious commercial implications of food-borne botulism, the control of nonproteolytic C. botulinum in minimally processed chilled foods is essential. Identification and optimization of appropriate controls (e.g., effective heating time), based on sound science, as well as their consistent application and a systematic approach to inform the public concerning safety, are a priority. One approach is quantitative microbiological risk assessment (QMRA), which combines appropriate elements together in an accessible framework to calculate the associated risk (16, 17). This approach requires robust scientific data, for example, on the spore loading in raw materials (18, 19) and on spore heat resistance. In this study, we gathered and analyzed evidence that relates to the heat resistance of nonproteolytic C. botulinum spores and established a representation that can be useful in the development of full risk assessments. An appropriate consideration of uncertainty is essential in both analysis and communication, so that outcomes of this investigation are presented in terms of probability to represent quantified beliefs.

Seven other reviews concerning the heat resistance of spores of nonproteolytic C. botulinum can be identified (20–26). These studies vary in their approaches and in their coverage of heating regimens but are a valuable source of information about factors influencing spore heat resistance (e.g., the type of strain, the composition of the heating menstruum, and/or recovery conditions), as well as indicate important heterogeneity and a range of D and z values for nonproteolytic C. botulinum in different heating menstrua at different temperatures. The review by van Asselt and Zwietering (26) is a valuable and extensive collection of information relating to the heat resistance of many food-borne pathogens, but in the case of spores of nonproteolytic C. botulinum, the chosen reference temperature, T = 120°C, is very high so that it is difficult to translate the information to practical food-manufacturing processes.

We have gathered and organized data to derive probabilistic distributions for parameters of spore heat resistance models for inclusion in QMRA and other food safety quantifications that have direct relevance to food manufacture. A complementary meta-analysis was recently done by Diao et al. (27) to express the heterogeneity observed in the heat resistance properties of spores of proteolytic C. botulinum at high temperatures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Population kinetics.

A simple picture of a homogeneous spore population identifies N0 spores acting individually but each with the same properties. In this case, the population kinetics, in the presence of isothermal heat inactivation, follows a log-linear relationship so that N(t) = N010−t/D(T), where N(t) is the size of the population after time t and D(T) is the decimal reduction time (D value) at temperature T. An estimate of the D value of a population can be obtained from a log-linear plot of the population size against time. In turn, the temperature dependence of the D value is usually related to a simple temperature difference and a single parameter, z, D(T2) = D(T1)10(T1 − T2)/z, which assigns an appropriate temperature scale, i.e., the temperature difference that makes the D value change by a factor of 10 (this parameter is usually known as the z value). This relationship ensures that a D value measured at one temperature, T1, can be used to predict the heat resistance at a second temperature, T2. Many alternative forms of population kinetics have been considered in relation to the thermal inactivation of bacterial populations (e.g., see reference 28), but in a consideration of large quantities of data from many distinct sources, the two relationships above, defining the D and z values, are the most general and therefore the most appropriate. An important exception to the simple behavior above describes a single population composed of two different subpopulations. Assuming that the D values of the two subpopulations are sufficiently distinct, the population kinetics will appear as two separate line segments on a log-linear plot and it is practical to estimate two D values (one for each subpopulation).

Literature review.

Information relating to D and z values for spores of nonproteolytic C. botulinum was collected following searches of electronic databases, scientific journals, books, and technical reports in a manner similar to that described previously (18). Searches of electronic databases were conducted by using keywords that included botulinum, spores, heat, temperature, inactivation, thermal, and survival. Searches were not restricted by country or language, and non-peer-reviewed articles were included. The references of the identified articles and relevant review articles were searched for potential omissions. The information reviewed includes studies published before 2011.

Each of the identified sources was assessed against the following 10 criteria for inclusion prior to data extraction:

The major aim of the study was to measure heat resistance of nonproteolytic C. botulinum spores.

The thermal treatment was performed with a wet process but did not include high-pressure processing, a pulsed electric field process, or microwave energy.

The experiments were isothermal in a temperature range of 50 to 95°C.

The bacterial strain name or the toxin type was identified.

The heating menstruum and the heating method were adequately described.

The recovery method, media, and conditions were adequately described.

The D and z values were provided in the report, or it was possible to calculate them from data.

The period of inactivation used to determine the D value covers more than 1 order of magnitude in the population size.

No inhibitory factors (e.g., a low pH of <4.1) are included in the heating menstruum or during recovery.

Kinetic data clearly separate a heat-sensitive and a heat-resistant fraction for systems that include lysozyme in the recovery medium (see below for further details).

When the D value was not reported explicitly but the source provided a temperature at which the heat treatment was performed, the starting inoculum size, and the number of surviving spores, the D value was determined from tables or figures by fitting the best straight line. When the experiments were conducted by using a TDT (thermal death time) method that determines the time it takes to inactivate a population of spores, the D value was calculated as , where tmax is the longest heating time for which spores could be recovered, tmin is the shortest time for which no recovery was possible, and N0 is the initial number of microorganisms (e.g., see reference 29). Some z values were determined from reported or calculated D values.

Extracted data were labeled by strain and toxin types, by the heating menstruum, by the heat treatment temperature, by the D value (in minutes), by the z value (in degrees Celsius), and by the method of calculation. Additionally, each record includes notes on the heating method, the recovery medium, and the experimental conditions. Where possible, the pH, water activity, and nutrients present in the heating menstruum were also recorded. All data records are included in the supplemental material.

Previous publications indicated that the presence of lytic enzymes (notably lysozyme) during recovery has a large effect on the measured D values for spores of nonproteolytic C. botulinum (30–41). Therefore, the collected data are segmented into two major subsets; −LYS (recovery of spores in the absence of lysozyme) and +LYS (recovery of spores in the presence of lysozyme). Sometimes lysozyme is deliberately added to the recovery medium, but in other cases, both heat treatment and recovery are conducted in a food substrate where the activity of lytic enzymes has previously been observed (e.g., hen egg white, seafood, vegetables). In the presence of lysozyme, survival curves are generally biphasic (indicating two subpopulations of spores), and a D value is assigned to each part of the curve, i.e., for each subpopulation of spores (a heat-sensitive subpopulation, +LYS HS, whose spore coats are impermeable to lysozyme and a heat-resistant subpopulation, +LYS HR, whose spore coats are permeable to lysozyme). In this case, spore heat resistance values were only included for kinetic data that clearly separated the heat-sensitive and -resistant fractions.

A majority of the tests were carried out with single strains of nonproteolytic C. botulinum; however, some experiments relate to mixtures of strains, often of different toxin types (i.e., cocktails), and are referred to as mixed-strain experiments.

Representing uncertainty.

For a particular population of spores under static conditions, the D value is fixed but uncertain. In principle, the D value can have any nonnegative value, and in some cases, reported values cover a very large range so that a log-normal distribution is a natural representation of the uncertainty, p[D(T)] ∼ lognormal(μ, σ), where μ and σ are the mean and standard deviation of ln[D(T)] [the parameters are easily transformed to other statistical descriptors such as the mean and standard deviation of D(T)].

The z value is also fixed but uncertain. It is practical to assume that the z value is bounded and has quite a restricted range. A four-parameter beta distribution is suitable to represent this uncertainty (e.g., see reference 42) as p(z) ∼ Beta(a, c, α1, α2), where a and c are the limits of the range of z values and α1 and α2 are exponents that determine the shape of the distribution. The mean value, <z>, is given in terms of the parameters as follows: <z> = a + [α1/(α1 + α2)](c − a).

Distribution parameters for D(T) and z values can be obtained by simple least-squares fitting of the appropriate cumulative distribution to the empirical distribution of the data (e.g., with the add-in package Solver for Microsoft Excel [2010]). For the z value, the fitted parameters are subject to some constraints, such as, e.g., that α1 and α2 are >0, to ensure that the distribution is unimodal. Upper and lower confidence intervals for the parameter estimates, and the assessment of goodness of fit, can be calculated according to a method described by Brown (43).

The aggregated data describing D values reflect measurements at several temperatures, but since the values at different temperatures are connected by the z value, it is possible to capture this variation within a single representation at a fixed reference temperature. In this case, we use T = 80°C as a reference since it is the dominant temperature for data collection (when lysozyme is absent during recovery). Combining complex information into a single representation of thermal inactivation of nonproteolytic C. botulinum is a valuable step toward the consistent application of safety in food manufacturing environments.

The process of temperature transformation for decimal reduction time is extended to include probabilistic information about D(T) and z (in the expression above, T1 is the experimental temperature and T2 is the reference temperature). A distribution for D′(80) is obtained by direct integration of the expression that describes the transformation of D values or, more simply, by a Monte Carlo process that involves sampling a distribution of D values measured at T1, p[D(T1)], and a distribution of z, p(z), repeatedly, e.g., with @RISK software version 5.5.1 (Palisade, USA)—the parent distributions are fitted to the experimental data. A notation D′(80) is used to indicate a D value that was measured at one temperature and then expressed at 80°C to discriminate it from direct measurements. A complete distribution for D′(80), based on the full data set, can be built as a weighted sum of distributions obtained from data at distinct experimental temperatures (weights are determined by the number of D value determinations at one particular temperature).

ANOVA.

Statistical analyses were used to identify factors that influence the magnitude of parameters describing the probability distributions for D and z values. Differences between groups of logarithmically transformed D values converted to a heating temperature of 80°C, logD′(80), were examined by a standard t test and, where necessary, by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with SPSS Statistics software version 21 (IBM, USA). Where given, the z value corresponding to the same set of conditions was used; otherwise, the value of <z> estimated in this study for strains of the appropriate toxin type was used.

Two factors investigated in detail were the dependence of spore heat resistance on the toxin type (by pairwise comparisons) and comparison of the heat resistances of the +LYS HS and +LYS HR spore fractions. A comparison of D values for the −LYS and +LYS HS fractions was also included. Additionally, the significance of the heating menstruum, heating technique, method of D value determination, and strain were examined by pairwise comparison of D′(80) in a temperature range of 50 to 83°C. An unsupervised hierarchical clustering approach with a dissimilarity metric based on Euclidean distance was used to indicate a strain classification pattern based on heat resistance properties. Clustering was conducted with SPSS Statistics software.

RESULTS

Literature sources.

Searches identified 15,037 titles, of which 46 met all of the inclusion criteria, including unpublished data from the Institute of Food Research and unpublished data from J.-M. Membré, P. McClure. Heat resistance of nonproteolytic C. botulinum spores has been studied in foods, buffer, and media under different recovery conditions over a temperature range of 50 to 95°C. In total, 753 D values were extracted from the sources; 253 D values correspond to nonproteolytic C. botulinum type B, 375 correspond to nonproteolytic C. botulinum type E, 65 correspond to nonproteolytic C. botulinum type F, and 60 correspond to a mixture of nonproteolytic C. botulinum strains. There were 549 D values from −LYS studies (originating from 39 references) and 194 D values from +LYS studies (originating from 10 references). For the +LYS studies, the data set includes 89 D values for heat-sensitive (HS) subpopulations (measured in a temperature range of 75 to 93°C) and 105 D values for heat-resistant (HR) subpopulations (measured in a temperature range of 75 to 95°C). A heating temperature of 80°C was used most frequently for experiments without lysozyme (151 D values). Other dominant temperatures for determination of D values were 70, 75, 77, 79, and 82°C, corresponding to 59, 66, 51, 37, and 56 data points. When lysozyme was added to the recovery medium, the temperature at which the heat resistance of spores was determined was generally higher; 90°C was dominant (88 data points), followed by 85°C (41 data points), and 80°C (22 data points). In total, 436 z values were collected from eligible studies. The majority of the data points were recorded for −LYS studies (366 z values). The literature data on spore heat resistance are summarized in the supplemental material.

Probability distributions of z values.

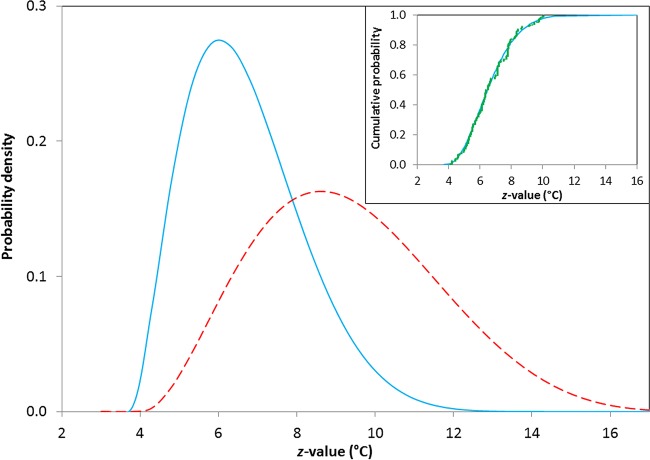

Probability distributions that represent z values from experiments with and without lysozyme are illustrated in Fig. 1. The inset represents the fitted cumulative distribution and the empirical data for z values measured in systems without lysozyme. A similar fit is obtained for systems with lysozyme (data not shown). For data collected in the absence of lysozyme (−LYS), the fitted beta distribution (blue solid line) has parameters a = 3.7°C (2.9°C, 4.5°C), c = 16.5°C (6.0°C, 27.0°C), α1 = 2.9 (0.8, 5.0), and α2 = 9.2 (0, 24.0), and for data collected in the presence of lysozyme (heat-resistant fraction; +LYS HR), z values correspond to beta parameters a = 4.0°C (0, 16.4), c = 19.6°C (0, 77.0), α1 = 3.1 (0, 20.6), and α2 = 6.0 (0, 59.0) (values in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals). There are too few data points to merit calculation of the distribution of z values for the heat-sensitive fraction (+LYS HS). Fits are obtained subject to the constraint that c is greater than or equal to the largest observed value of z. The corresponding mean values are <z> = 6.7°C (4.4°C, 10.0°C) for −LYS and <z> = 9.3°C (5.4°C, 14.3°C) for +LYS HR.

FIG 1.

Beliefs concerning z values (in degrees Celsius) for spores of nonproteolytic C. botulinum. The solid blue line represents z values measured without lysozyme in the recovery media (−LYS), <z> = 6.7°C, and the dashed red line represents z values measured for the HR fraction with lysozyme in the recovery media (+LYS HR), <z> = 9.3°C. In the inset, green squares represent the empirical distribution of the data and the blue line represents the cumulative probability for experiments conducted in the absence of lysozyme in the recovery media at temperatures between 50 and 83°C (n = 338).

Probability distributions of D values.

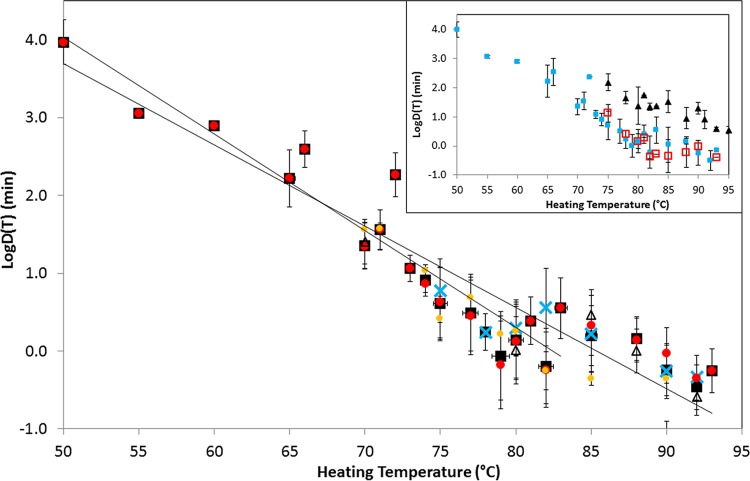

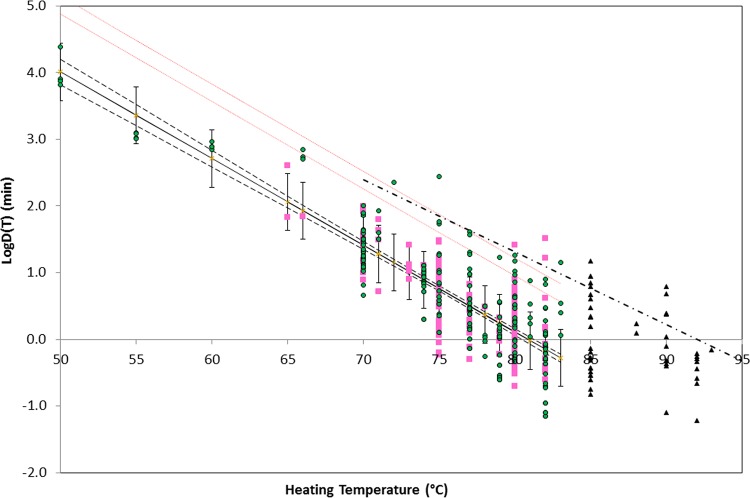

A summary of the data representing D values is shown in Fig. 2, where each data point and error bar represents the mean and standard deviation of the logarithm of the D values measured at one particular temperature (experimental temperatures were 50 to 93°C, and temperatures measured on the Fahrenheit scale were converted to the nearest whole degree Celsius). The inset in Fig. 2 shows a comparison of the D values measured in the absence and presence of lysozyme (HS and HR fractions) in recovery media. The measured spore heat resistance was similar in the absence of lysozyme and for the heat-sensitive (HS) fraction in the presence of lysozyme but was higher for the heat-resistant (HR) fraction in the presence of lysozyme (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

Summary of the heat resistance (D values) of spores of nonproteolytic C. botulinum extracted from literature sources. Data points and error bars correspond to the mean and standard deviation of all of the D values measured at a particular experimental temperature in the absence of lysozyme. Black squares correspond to all of the data, and blue crosses, red circles, orange circles, and open triangles correspond to toxin types B, E, and F and mixed toxin types. The solid lines represent the best fit to the experimental data in a temperature range of 50 to 83°C and for the whole data set. The inset compares D values measured in the absence of lysozyme (blue closed squares) and those measured in the presence of lysozyme (HS fraction, red open squares; HR fraction, closed triangles).

By considering the D values obtained in the absence of lysozyme from increasing ranges of experimental temperatures, after transformation to a reference temperature of 80°C, it is possible to identify an important property of the thermal inactivation data set. For data obtained (in the absence of lysozyme) from experiments in temperature ranges of 50 to 79°C, 50 to 80°C, 50 to 81°C, 50 to 82°C, and 50 to 83°C, an Anderson-Darling statistic (A2) is consistently in the range of 1.4 to 2.2. In contrast, the data obtained from experiments in temperature ranges of 50 to 85°C, 50 to 88°C, 50 to 90°C, and 50 to 93°C have an Anderson-Darling statistic in the range of 4.1 to 5.9. The Anderson-Darling test measures the approximate “normality” of a set of empirical values (e.g., see reference 44), and in this case, the sudden change in the value of A2 indicates a significant change in the statistics that underpin the variation of D values collected at higher temperatures. Taking account of this finding, Fig. 2 shows the line of best fit for D values measured in a temperature range of 50 to 83°C and also the line for the entire data set. A similar pattern of temperature dependence is observed for D values that correspond to the HS fraction of the +LYS data set but not for D values that correspond to the HR fraction of the +LYS data set (A2 is 1.0 to 2.2 and shows no rise at higher heating temperatures). The Anderson-Darling values do not depend strongly on the z value used for transformation of D values (where possible, the measured z value was used).

Effect of lysozyme during recovery of heated spores.

The parameters of fitted normal distributions for the decimal logarithm of the D values of spores of nonproteolytic C. botulinum are shown in Table 1. The D values measured in the absence of lysozyme (−LYS) and for the HS fraction in the presence of lysozyme (+LYS HS) are both significantly smaller than those for the HR fraction of spores in the presence of lysozyme (+LYS HR).

TABLE 1.

Parameters of fitted normal distributions corresponding to reported values of log[D(T)] (minutes) for spores of nonproteolytic C. botulinuma

| T (°C) | −LYS |

+LYS HS |

+LYS HR |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | <Log[D(T)]> | σlogD | n | <Log[D(T)]> | σlogD | n | <Log[D(T)]> | σlogD | |

| 70 | 59 | 1.35 | 0.28 | ||||||

| 75 | 66 | 0.71 | 0.49 | 4 | 1.12 | 0.30 | 5 | 2.18 | 0.28 |

| 80 | 151 | 0.16 | 0.41 | 9 | 0.16 | 0.26 | 9 | 1.37 | 0.64 |

| 85 | 27 | 0.04 | 0.60 | 18 | −0.35 | 0.57 | 22 | 1.52 | 0.38 |

| 90 | 8 | −0.24 | 0.42 | 40 | −0.03 | 0.21 | 44 | 1.29 | 0.20 |

Values correspond to measurements of the HS and HR fractions of spores in the presence (+LYS) and absence (−LYS) of lysozyme. n is the number of reported values.

By using the probabilities of the measured z values (Fig. 1), lethality measurements at different temperatures (including those in Table 1) can be transformed to establish belief about D values at 80°C. For experiments performed in the absence of lysozyme (and for the heat-sensitive fraction in the presence of lysozyme), data are restricted to temperatures in the range of 50 to 83°C. The parameters for normal distributions of log[D′(80)] are summarized in Table 2. Direct comparison of transformed D values, p[D′(80)], with those measured at 80°C, p[D(80)] (Table 1), shows that the distributions have very similar locations but the distribution of transformed values includes additional spread from uncertainties associated with the z value.

TABLE 2.

Parameters of fitted normal distributions corresponding to values of log[D(T)] (minutes), transformed to 80°C, for spores of nonproteolytic C. botulinuma

| Parameter | −LYS | +LYS HS | +LYS HR |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 503 | 27 | 105 |

| <D′(80)> | 2.23 | 1.32 | 245 |

| σD′(80) | 4.44 | 0.95 | 423 |

| <Log[D′(80)]> | 0.00 | 0.03 | 2.09 |

| σlog[D′(80)] | 0.55 | 0.28 | 0.51 |

Values correspond to measurements of the HS (75 to 83°C) and HR (75 to 95°C) fractions of spores in the presence (+LYS) and absence (−LYS; 50 to 83°C) of lysozyme. n is the number of reported values.

Recovery of heated spores of nonproteolytic C. botulinum in the presence of lysozyme (or some other lytic enzymes) results in biphasic survival curves, with HS (+LYS HS) and HR (+LYS HR) fractions (Fig. 2 and Tables 1 and 2). Analysis of the collected data indicates that there is no significant difference (t test; P = 0.07) between D values measured in a heating temperature range of 50 to 83°C and those transformed to 80°C [D′(80)] for spores recovered in the absence of lysozyme (−LYS) and the HS (+LYS HS) fraction of spores recovered in the presence of lysozyme. With recovery in the presence of lysozyme, it was estimated that, for the collected data, the +LYS HR fraction constitutes approximately 0.02 to 3.1% of the initial spore population. Statistical analysis indicates a significant difference between the measured D values of spores from the +LYS HS and +LYS HR fractions (t test; P = 0.01). There is also a significant difference between the measured D values of −LYS spores and the +LYS HR fraction (t test, P < 10−6).

Effect of toxin type.

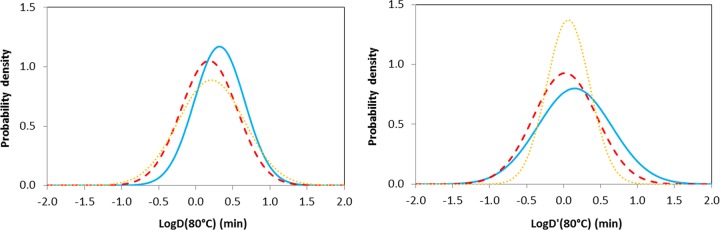

Analysis (ANOVA and paired t tests) of logD′(80) values established in the range of T = 53 to 83°C in the absence of lysozyme shows that there is a small but significant difference in the spore heat resistance of strains with different toxin types {<logD′(80)> = 0.15, 0.02, and 0.06 and σlog[D′(80)] = 0.50, 0.43, and 0.29 for types B, E, and F with P = 0.03 and <z> = 6.9, 6.9, and 6.5°C}; representative normal distributions are indicated in Fig. 3 along with corresponding isothermal distributions. It is difficult to be precise about the origin of this difference, but it may correspond to the inclusion of measurements from the lowest experimental temperatures (the difference disappears if the data are restricted to T ≥ 75°C). Strains forming type B toxin more frequently showed higher heat resistance than strains forming type E toxin. For log[D(80)], there is no significant difference (P = 0.18) in spore heat resistance for different toxin types. Similarly, there was no significant difference in heat resistance between the toxin types of spores recovered in the presence of lysozyme {<logD′(80)> = 2.01, 2.00, and 2.41 and σlog[D′(80)] = 0.53, 0.49, and 0.05 for types B, E, and F with P = 0.56}.

FIG 3.

Effect of toxin type on distributions of log[D(80)] and log[D′(80)] (min) for spores of nonproteolytic C. botulinum recovered in the absence of lysozyme. Isothermal values are measured at 80°C, and the transformed values [D′(80)] are converted from data established in a heating temperature range of 50 to 83°C. The blue solid line represents toxin type B strains, the red dashed line represents toxin type E strains, and the orange dotted line represents toxin type F strains.

Strain variation.

A total of 37 strains (types B, E, and F) were captured in eligible studies. The most common strains tested were Eklund 17B (n = 70) and Beluga (n = 52). The strains for which the D value was measured in at least 10 studies (including transformed values) are summarized in Table 3. The highest mean value of D′(80) corresponds to strain Saratoga [D′(80), ∼2.63 min], whereas the lowest value corresponds to strain Crab 25V-2 [D′(80), ∼0.23 min]. The strains with D values determined at least 20 times (Eklund 17B, Alaska, ATCC 17786, Beluga, Crab G21-5, Saratoga, and Eklund 202F) were tested for significant differences by one-way ANOVA. Strain Saratoga is significantly more heat resistant than the other strains (P < 0.01), whereas strains ATCC 17786 and Crab G21-5 have smaller D values. Interestingly, according to statistical analysis, the heat resistance of spores of strains Eklund 17B and Eklund 202F are the same (P = 0.3). Cluster analysis reveals no obvious pattern (i.e., all of the strains were identified with a single cluster) based on the heat resistance properties of the strains tested (results not presented).

TABLE 3.

Heat resistance (D values [minutes]) of spores of different strains of nonproteolytic C. botulinum measured at (or transformed to) a heating temperature of 80°Ca

| Strain | Toxin type | n | <Log[D′(80)]> | σlog[D′(80)] | n | <Log[D(80)]> | σlog[D(80)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eklund 17B | B | 70 | 0.18 | 0.49 | 33 | 0.35 | 0.36 |

| Kap B2 | B | 10 | −0.21 | 0.29 | 3 | 0.04 | 0.37 |

| 1304E | E | 13 | 0.09 | 0.20 | 3 | 0.22 | 0.05 |

| 8E | E | 14 | −0.31 | 0.39 | 2 | 0.08 | 0.25 |

| Alaska | E | 39 | 0.01 | 0.45 | 7 | 0.28 | 0.30 |

| ATCC 17786 | E | 37 | −0.21 | 0.20 | |||

| ATCC 9564 | E | 11 | 0.40 | 0.73 | 5 | 0.60 | 0.76 |

| Beluga | E | 52 | 0.10 | 0.24 | 12 | −0.04 | 0.19 |

| Crab 25 V-1 | E | 11 | −0.27 | 0.16 | |||

| Crab 25 V-2 | E | 11 | −0.64 | 0.22 | |||

| Crab G21-5 | E | 27 | −0.20 | 0.37 | |||

| Minnesota | E | 12 | 0.02 | 0.24 | |||

| Saratoga | E | 47 | 0.42 | 0.35 | 15 | 0.40 | 0.28 |

| Craig 610 | F | 11 | 0.16 | 0.28 | 1 | −0.12 | |

| Eklund 202F | F | 27 | 0.14 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.69 | |

| 190 | F | 14 | −0.19 | 0.11 |

n is the number of reports, and only strains for which D values were reported at least 10 times are included. For strains measured more than once at T = 80°C, the mean of the logarithm of reported and transformed values has a correlation coefficient of ∼0.75.

Effect of heating method.

Analysis of 503 D values measured in the absence of lysozyme in a temperature range of 50 to 83°C and transformed to a heating temperature of 80°C reveals that the greatest spore heat resistance was recorded for a single thermal death experiment performed with raw egg white with D′(80) = 32.6 min [D(83) = 14.2 min, z = 6.9] with a type E strain (Alaska). The D value was calculated on the basis of a growth/no-growth method by direct incubation of heated medium with injected tryptone peptone glucose yeast extract medium (45). As suggested by others, e.g., Chai and Liang (46), D values measured by the TDT method can be higher than those measured by using survival curves. The second highest D value was calculated by using data from four experiments conducted with cod fish as a heating menstruum at two temperatures, 75 and 80°C, with strains Eklund 17B (type B) and ATCC 9564 (type E) (47). The weakest resistance corresponds to four experiments performed with 0.03 M phosphate buffer with D′(80) = 0.5 min determined for type E strains (8E, 1304E, Minneapolis, and Saratoga) (48). However, when 39 different heating menstrua were divided into two categories assigned to media/buffer (n = 258; water, saline, phosphate buffer, and various microbiological growth media) and food matrices [n = 245; autoclaved chub fish, béchamel sauce, bolognaise sauce, broccoli puree, carrot homogenates, clam liquor, cod, corn brine, crabmeat, fine carrot, haddock slurry, meat medium, menhaden surimi, milk (evaporated), oyster homogenates, peas, potato puree, precoagulated egg white, raw egg white, salmon, sardines (in tomato sauce), shrimp, tomato homogenates, tuna, tuna (in oil), and whitefish chubs], no significant difference in D values was detected (t test, P = 0.98).

The importance of the heating technique and the method of D value determination with respect to the measured spore heat resistance was analyzed by one-way ANOVA. The analysis of D values obtained by 11 heating techniques (bottles, flasks, sealed ampoules, sealed capillaries, TDT cans, TDT tubes, unsealed TDT tubes, screw-capped vials and screw-capped tubes in a water bath, and sealed ampoules in an oil bath) indicates a significantly greater mean value of D′(80) corresponding to sealed ampules or TDT cans in a water bath (ANOVA, P < 0.01). Similarly, across five methods for the measurement of D values [labeled survivor curve, TDT, TDT/Stumbo (1948), TDT/Stumbo (1950), and TDT/Stumbo (1957)], TDT and TDT/Stumbo (1948) appear to yield significantly higher D values (ANOVA, P < 10−6). The lowest mean D values have been calculated when the spore heat resistance was measured by using a survivor curve.

DISCUSSION

On the basis of an extensive analysis of previously published information, we have constructed a quantitative representation of beliefs concerning the heat resistance of spores of nonproteolytic C. botulinum. The beliefs are represented by parameters that describe probability distributions for z values and for D values at a fixed temperature of 80°C (these parameters describe linear kinetics of thermal inactivation over a range of operating temperatures). A distinct set of parameters corresponds to information that relates to the heat resistance of spores recovered in the presence of lysozyme. The probability distributions dominantly represent uncertainty in relation to the parameter values but also include some elements of variability associated with distinct bacterial strains and experimental methods. The parameterized form facilitates the inclusion of information about the heat resistance of spores into quantitative risk assessment for food-borne botulism hazards; this is an essential element in the safety management of chilled food products. The detailed statistical representation of both D values and z values ensures that the relevant uncertainties can be combined correctly to establish an uncertain D value at other temperatures.

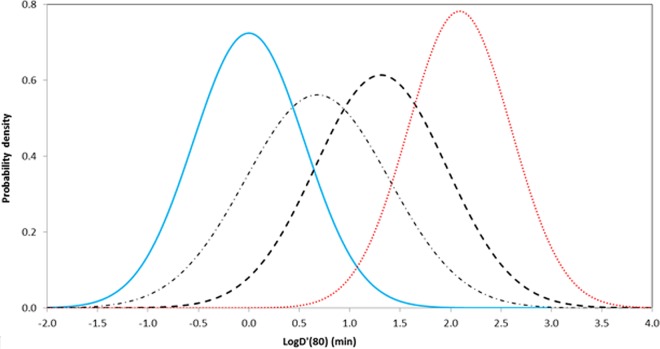

Probabilities concerning the transformed D′(80) values converted from data established over a range of heating temperatures are compared with two other representations in Fig. 4. The results of van Asselt and Zwietering (26) fall between the values associated with heat resistance measured with recovery in the presence or absence of lysozyme. Note that van Asselt and Zwietering did not segment their data with respect to lysozyme and that their chosen reference temperature (Dref = 120°C) is considerably higher than the majority of the operating temperatures that are associated with nonproteolytic C. botulinum hazards. The distribution constructed to represent the guidance given by the United Kingdom Food Standards Agency (49) covers higher (more conservative) D values than those observed for recovery in the absence of lysozyme but does not consider recovery in the presence of lysozyme explicitly (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

Distribution of log[D′(80)] for spores of nonproteolytic C. botulinum. The blue solid line represents beliefs from the present study, based on a large collection of previously published results, for the heat resistance of spores in the absence of lysozyme [<logD′(80)> = 0.00, σlog[D′(80)] = 0.55, <z> = 6.7], and the red dotted line represents beliefs for inactivation of the HR fraction of spores in the presence of lysozyme [<logD′(80)> = 2.09, σlog[D′(80)] = 0.51, <z> = 9.3]. The dotted-dashed line illustrates a probability distribution for D values estimated by van Asselt and Zwietering (26) [<logD′(80)> = 0.68, σlog[D′(80)] = 0.71, <z> = 18.6], and the dashed line represents a distribution based on the guidance of the United Kingdom Food Standards Agency of 90°C for 10 min (49) [<logD′(80)> = 1.31, σlog[D′(80)] = 0.65, <z> = 9.2; with the coefficient of variation of the logarithm of the D value taken as 0.5].

In addition to the separation of systems that involve lysozyme (Fig. 4), another important development was to exclude thermal data collected at temperatures above 83°C (when spores were recovered in the absence of lysozyme) (see above). The implication of this development was that the real D values were lower than those reported at higher heating temperatures. The origins of distinctions for D values that correspond to the higher operating temperature are unclear. Decimal reduction times at higher temperatures (∼90°C) have values in the range of 0.01 to 1 min, so that actual physical measurement may present problems. Alternatively, there may be real changes in heat resistance as the physical properties of spores (particularly the transport properties of the spore coat) change in response to higher temperatures.

Experiments involving lysozyme indicate that the heat-resistant fraction usually represents 0.02 to 3.1% of the spore population. This agrees with previous estimates and reflects the fraction of spores with coats that are permeable to lysozyme (37). This includes both situations where lysozyme is added deliberately to the recovery medium and those in which it is present in the substrate used for recovery, e.g., vegetable juices or crabmeat (50, 51). In a study by Peck et al. (35), a biphasic survivor curve, and consequently the increased number of surviving spores, was observed with a lysozyme concentration of 0.1 μg ml−1 and the maximum spore recovery corresponded to a concentration of ∼5 to 10 μg ml−1. Significantly higher D values, and z values, in systems with lysozyme indicate that this property of the substrate is an important variable in risk assessments. Lysozyme has been reported in many types of raw foods and may survive the heat treatments typically applied to chilled foods (31, 33, 35–39, 41, 51–55).

Studies of the genomic variability of nonproteolytic C. botulinum have revealed that strains forming type B and F toxins are closely related and distinct from most type E toxin-forming strains (8, 9, 14, 56–59). Physiological differences have also been described, for example, in different trends of carbohydrate utilization, with type B and F strains producing acid from amylopectin, amylose, and glycogen but not from melezitose or inositol and type E strains showing the opposite trend (14). However, although there was strain variability, there did not appear to be a clear relationship between the toxin type and the minimum growth temperature or the maximum NaCl concentration permitting growth (14). In the present study, statistical tests indicate that there is only a weak relationship between the toxin type and spore heat resistance, although some authors have reported the measured spore heat resistance of type B strains to be greater than that of type E strains (33, 37, 60). In the present study, of the seven strains (one type B, five type E, and one type F) that had been studied more than 20 times, strain Saratoga (a type E strain) had the highest measured spore heat resistance. The generation of thermal death data from a significant number of strains in a reproducible way would be of great value.

The D values collected in this report have a direct application in risk management. On the basis of the 99% upper confidence limit (UCL) of predicted D values (in the absence of lysozyme and for heating temperatures below 83°C), the time required to reduce the spore concentration by a factor of 106 at 90°C is ∼5 min (Fig. 5). This value indicates that the current guidance of the United Kingdom Food Standards Agency (49) and the Chilled Food Association (61) (Table 4) provides a suitable level of safety. Six D values, from five different studies, have values larger than that the 99% UCL for the predicted response. Two, from Scott and Bernard (60), who reported D(82) = 32.3 min and D(82) = 16.7 min, correspond to heating in 0.067 M phosphate buffer. Bohrer et al. (62) reported D(72) = 226 min for spores heated in tuna (in oil), and Alderman et al. (45) reported D(83) = 14.2 min for raw egg white. D(80) = 25.8 min can be calculated from data reported by Murrell and Scott (63), but the heating menstruum and incubation time were not reported and D(75) = 275 min can be calculated from studies by Fernández and Peck (64). Four of these D values were obtained following prolonged incubation (90 to 336 days) (60, 62, 64). It has been observed by several authors, e.g., by Lynt et al. (65), that an extended period of incubation permits germination of damaged spores and so increases the measured spore heat resistance. Such observations are important when translating relative short-term experiments into long-term shelf lives of chilled foods. Four of these values are based on the TDT method, and the actual population inactivation kinetics were not reported. The z values collected in this report have a direct application in risk management. A suitable z value of 6.7°C is indicated from the analysis of the literature data (for recovery in the absence of lysozyme) and is consistent with the z value of 7°C advocated by the Chilled Food Association, compared to the z value of 9.2°C advocated by the United Kingdom Food Standards Agency (49) (Table 4); analysis of the reported D values (Fig. 5) indicates a z value of 7.7°C, in the middle of this range.

FIG 5.

Logarithms of previously published D values and fitted models of the heat resistance of spores of nonproteolytic C. botulinum in foods (green circles) and laboratory media (pink squares) that do not contain lysozyme. Black triangles indicate data that correspond to heating at temperatures that exceed 83°C, which are not included in the model. The black solid line is the line of best fit {log[D(T)] = 10.506 − 0.1299T with r = 0.72}, and the dashed lines indicate the 95% confidence interval for the fit. Red dotted lines represent the 95% and 99% UCLs of the predicted response. The dashed-dotted line indicates the current guidance of the United Kingdom Food Standards Agency (49)/Advisory Committee on the Microbiological Safety of Food (66) for heat treatments applied to chilled foods. Data are from references 31, 33–37, 40, 41, 45–48, 50, 51, 55, 60, 62–65, and 67–90 and unpublished work by J.-M. Membré and P. McClure and at the Institute of Food Research.

TABLE 4.

Heating time required to reduce the concentration of nonproteolytic C. botulinum spores by a factor of 106a

| T (°C) | Time (min) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UKFSA 90 for 10 (z = 9.2°C) | CFA 90 for 10 (z = 7°C) | Model from current literature review |

|||

| Expected value | 95% UCL | 99% UCL | |||

| 70 | 1,675 | 155 | 1,092 | 2,019 | |

| 75 | 464 | 35 | 243 | 448 | |

| 80 | 129 | 270 | 7.8 | 54 | 100 |

| 85 | 36 | 52 | 1.8 | 12 | 22 |

| 90 | 10 | 10 | 0.4 | 2.7 | 4.9 |

Conclusions.

A large data set of previously published D values for nonproteolytic C. botulinum spore inactivation during heating provides evidence for the development of mathematical models that allow general conclusions regarding heat resistance and support quantitative risk assessment for food-borne hazards. The models express current information uncertainty, and associated analysis points to possible origins of population variability.

This review indicates that it is crucial to take care when interpreting information regarding the thermal inactivation of spores of nonproteolytic C. botulinum because experiments that involve lysozyme or heating temperatures of >83°C require independent analyses. In addition, it is important to appreciate that the models developed in this study describe the reduction of spore population size for nonproteolytic C. botulinum following heating but do not quantify the properties of survivors, such as the ability to germinate and grow, that may be relevant for risk assessment.

Current advice does not consider the influence of lysozyme present in heated food products. This review, besides describing parameter values that can be used in QMRA, is strong evidence for separate treatments of foods that include lytic enzymes. On the basis of the results of this review (using data from Table 2 and the estimate of the heat-resistant fraction), heated spores recovered in the presence of lysozyme may require ∼80 min at 90°C to reduces the spore concentration by a factor of 106.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J.-M. Membré, P. McClure, and Institute of Food Research colleagues for making unpublished data available. E.W. is most grateful to Pradeep Malakar for many helpful discussions.

This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council as part of the BBSRC Institute Strategic Programme on Gut Health and Food Safety (BB/J004529/1), by the United Kingdom Food Standards Agency, and by the Institute of Food Research.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01737-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Peck MW. 2006. Clostridium botulinum and the safety of minimally heated, chilled foods: an emerging issue? J Appl Microbiol 101:556–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.02987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peck MW, Goodburn KE, Betts RP, Stringer SC. 2008. Assessment of the potential for growth and neurotoxin formation by non-proteolytic Clostridium botulinum in short shelf-life commercial foods designed to be stored chilled. Trends Food Sci Technol 19:207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2007.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peck MW, Stringer SC, Carter AT. 2011. Clostridium botulinum in the post-genomic era. Food Microbiol 28:183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson EA. 2007. Clostridium botulinum, p 401–422. In Doyle MP, Beuchat LR (ed), Food microbiology: fundamentals and frontiers, 3rd ed ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindström M, Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Korkeala H. 2009. Molecular epidemiology of group I and group II Clostridium botulinum, p 103–130. In Gottschalk G, Br̈uggemann H (ed), Clostridia: molecular biology in the post-genomic era. Caister Academic Press, Norfolk, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peck MW. 2009. Biology and genomic analysis of Clostridium botulinum. Adv Microb Physiol 55:183–265, 320. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2911(09)05503-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graham AF, Mason DR, Maxwell FJ, Peck MW. 1997. Effect of pH and NaCl on growth from spores of non-proteolytic Clostridium botulinum at chill temperature. Lett Appl Microbiol 24:95–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765X.1997.00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter AT, Stringer SC, Webb MD, Peck MW. 2013. The type F6 neurotoxin gene cluster locus of group II Clostridium botulinum has evolved by successive disruption of two different ancestral precursors. Genome Biol Evol 5:1032–1037. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evt068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter AT, Peck MW. 2015. Genomes, neurotoxins and biology of Clostridium botulinum group I and group II. Res Microbiol 166:303–317. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carter AT, Austin JW, Weedmark KA, Corbett C, Peck MW. 2014. Three classes of plasmid (47-63 kb) carry the type B neurotoxin gene cluster of group II Clostridium botulinum. Genome Biol Evol 6:2076–2087. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.King LA, Niskanen T, Junnikkala M, Moilanen E, Lindström M, Korkeala H, Korhonen T, Popoff M, Mazuet C, Callon H, Pihier N, Peloux F, Ichai C, Quintard H, Dellamonica P, Cua E, Lasfargue M, Pierre F, de Valk H. 2009. Botulism and hot-smoked whitefish: a family cluster of type E botulism in France, September 2009. Euro Surveill 14:19394 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=19394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peck MW, Stringer SC. 2005. The safety of pasteurised in-pack chilled meat products with respect to the foodborne botulism hazard. Meat Sci 70:461–475. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stringer SC, Webb MD, Peck MW. 2011. Lag time variability in individual spores of Clostridium botulinum. Food Microbiol 28:228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stringer SC, Carter AT, Webb MD, Wachnicka E, Crossman LC, Sebaihia M, Peck MW. 2013. Genomic and physiological variability within group II (non-proteolytic) Clostridium botulinum. BMC Genomics 14:333. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Council for Agricultural Science and Technology (CAST). 1994. Foodborne pathogens: risks and consequences. Economic Research Services, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Ames, IA. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barker GC, Malakar PK, Del Torre M, Stecchini ML, Peck MW. 2005. Probabilistic representation of the exposure of consumers to Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin in a minimally processed potato product. Int J Food Microbiol 100:345–357. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malakar PK, Barker GC, Peck MW. 2011. Quantitative risk assessment for hazards that arise from non-proteolytic Clostridium botulinum in minimally processed chilled dairy-based foods. Food Microbiol 28:321–330. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barker GC, Malakar PK, Plowman J, Peck MW. 2016. Quantification of non-proteolytic Clostridium botulinum spore loads in food materials. Appl Environ Microbiol 82:1675–1685. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03630-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peck MW, Plowman J, Aldus CF, Wyatt GM, Izurieta WP, Stringer SC, Barker GC. 2010. Development and application of a new method for specific and sensitive enumeration of spores of non-proteolytic Clostridium botulinum types B, E, and F in foods and food materials. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:6607–6614. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01007-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Betts GD, Gaze JE. 1995. Growth and heat resistance of psychrotrophic Clostridium botulinum in relation to “sous-vide” products. Food Control 6:57–63. doi: 10.1016/0956-7135(95)91455-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.International Commission of Microbiological Specifications for Foods (ICMSF). 1996. Microbiological specifications of food pathogens, p 66–111. In Roberts TA, Baird-Perker AC, Tompkin RB (ed), Microorganisms in foods 5. Blackie Academic & Professional, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindström M, Kiviniemi K, Korkeala H. 2006. Hazard and control of group II (non-proteolytic) Clostridium botulinum in modern food processing. Int J Food Microbiol 108:92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lund BM, Notermans SHW. 1993. Potential hazards associated with REPFEDS, p 279–303. In Hauschild AHW, Dodds KL (ed), Clostridium botulinum ecology and control in foods, vol 238 Marcel Dekker, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silva FVM, Gibbs PA. 2010. Non-proteolytic Clostridium botulinum spores in low-acid cold-distributed foods and design of pasteurization processes. Trends Food Sci Technol 21:95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2009.10.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stringer SC, Peck MW. 2008. Foodborne clostridia and the safety of in-pack processed foods, p 251–276. In Richardson P. (ed), In-pack processed foods: improving quality. Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Asselt ED, Zwietering MH. 2006. A systematic approach to determine global thermal inactivation parameters for various food pathogens. Int J Food Microbiol 107:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diao MM, André S, Membré JM. 2014. Meta-analysis of D-values of proteolytic Clostridium botulinum and its surrogate strain Clostridium sporogenes PA 3679. Int J Food Microbiol 174:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peleg M, Cole MB. 1998. Reinterpretation of microbial survival curves. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 38:353–380. doi: 10.1080/10408699891274246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Townsend CT, Esty JK, Baself FC. 1938. Heat-resistance studies on spores of putrefactive anaerobes in relation to determination of safe processes for canned foods. J Food Sci 3:323–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1938.tb17065.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sebald M, Ionesco H. 1972. Lysozyme-proteolytic enzyme dependent germination of type E Clostridium botulinum spores. C R Acad Sci Hebd Seances Acad Sci D 275:2175–2177. (In French.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alderton G, Chen JK, Ito KA. 1974. Effect of lysozyme on recovery of heated Clostridium botulinum spores. J Appl Microbiol 27:613–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hauschild AHW, Hilsheimer R. 1977. Enumeration of Clostridium botulinum spores in meats by a pour plate procedure. Can J Microbiol 23:829–832. doi: 10.1139/m77-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smelt JPPM. 1980. Heat resistance of Clostridium botulinum in acid ingredients and its signification for the safety of chilled foods. Ph.D. thesis. University of Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scott VN, Bernard DT. 1985. The effect of lysozyme on the apparent heat resistance of non-proteolytic type E Clostridium botulinum. J Food Saf 7:145–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4565.1985.tb00537.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peck MW, Fairbairn DA, Lund BM. 1992. The effect of recovery medium on the estimated heat-inactivation of spores of non-proteolytic Clostridium botulinum. Lett Appl Microbiol 15:146–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.1992.tb00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peck MW, Fairbairn DA, Lund BM. 1992. Factors affecting growth from heat-treated spores of non-proteolytic Clostridium botulinum. Lett Appl Microbiol 15:152–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.1992.tb00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peck MW, Fairbairn DA, Lund BM. 1993. Heat resistance of spores of non-proteolytic Clostridium botulinum estimated on medium containing lysozyme. Lett Appl Microbiol 16:126–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.1993.tb01376.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lund BM, Peck MW. 1994. Heat resistance and recovery of spores of non-proteolytic Clostridium botulinum in relation to refrigerated, processed foods with an extended shelf-life. Symp Ser Soc Appl Microbiol 23:115S–128S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fernández PS, Peck MW. 1999. A predictive model that describes the effect of prolonged heating at 70 to 90°C and subsequent incubation at refrigeration temperatures on growth from spores and toxigenesis by non-proteolytic Clostridium botulinum in the presence of lysozyme. Appl Environ Microbiol 65:3449–3457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stringer SC, Haque N, Peck MW. 1999. Growth from spores of non-proteolytic Clostridium botulinum in heat-treated vegetable juice. Appl Environ Microbiol 65:2136–2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lindström M, Nevas M, Hielm S, Lähteenmäki L, Peck MW, Korkeala H. 2003. Thermal inactivation of non-proteolytic Clostridium botulinum type E spores in model fish media and in vacuum-packaged hot-smoked fish products. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:4029–4036. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.7.4029-4036.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vose D. 2008. Risk analysis: a quantitative guide, 3rd ed John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, England. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brown AM. 2001. A step-by-step guide to non-linear regression analysis of experimental data using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 65:191–200. doi: 10.1016/S0169-2607(00)00124-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kendall MK, Stuart A. 1979. The advanced theory of statistics, vol.2 Charles Griffin & Company, High Wycombe, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alderman GG, Sugiyama H, King GJ. 1972. Factors in survival of Clostridium botulinum type E spores through the fish smoking process. J Milk Food Technol 35:163–166. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chai TJ, Liang KT. 1992. Thermal resistance of spores from 5 type E Clostridium botulinum strains in eastern oyster homogenates. J Food Prot 55:18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gaze JE, Brown GD. 1990. Determination of the heat resistance of a strain of Clostridium botulinum type B and a strain of type E, heated in cod and carrot homogenate over the temperature range 70 to 90°C. Technical memorandum no. 592. Campden Food and Drink Research Association, Chipping, Campden, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ito KA, Seslar DJ, Mercer WA. 1967. The thermal and chlorine resistance of Clostridium botulinum type A, B and E spores, p 108–112. In Ingram M, Roberts TA (ed), Botulism 1966. Chapman and Hall, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Food Standards Agency (FSA). 2008. Food Standards Agency guidance on the safety and shelf-life of vacuum and modified atmosphere packed chilled foods with respect to non-proteolytic Clostridium botulinum. Food Standards Agency, London, United Kingdom: http://www.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/multimedia/pdfs/publication/vacpacguide.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peterson ME, Pelroy GA, Poysky FT, Paranjpye RN, Dong FM, Pigott GM, Eklund MW. 1997. Heat pasteurization process for inactivation of non-proteolytic types of Clostridium botulinum in picked Dungeness crabmeat. J Food Prot 60:928–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stringer SC, Peck MW. 1996. Vegetable juice aids the recovery of heated spores of non-proteolytic Clostridium botulinum. Lett Appl Microbiol 23:407–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.1996.tb01347.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cunningham FE, Proctor VA, Goetsch ST. 1991. Egg-white lysozyme as a food preservative: an overview. World Poultry Sci J 47:141–163. doi: 10.1079/WPS19910015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peck MW, Fernández PS. 1995. Effect of lysozyme concentration, heating at 90°C, and then incubation at chilled temperatures on growth from spores of non-proteolytic Clostridium botulinum. Lett Appl Microbiol 21:50–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.1995.tb01005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Proctor VA, Cunningham FE. 1988. The chemistry of lysozyme and its use as a food preservative and a pharmaceutical. Crit Rev Food Sci 26:359–395. doi: 10.1080/10408398809527473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stringer SC, Fairbairn DA, Peck MW. 1997. Combining heat treatment and subsequent incubation temperature to prevent growth from spores of non-proteolytic Clostridium botulinum. J Appl Microbiol 82:128–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1997.tb03307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Derman Y, Lindström M, Selby K, Korkeala H. 2011. Growth of group II Clostridium botulinum strains at extreme temperatures. J Food Prot 74:1797–1804. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-11-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hielm S, Björkroth J, Hyytiä E, Korkeala H. 1999. Ribotyping as an identification tool for Clostridium botulinum strains causing human botulism. Int J Food Microbiol 47:121–131. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(99)00024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hill KK, Smith TJ, Helma CH, Ticknor LO, Foley BT, Svensson RT, Brown JL, Johnson EA, Smith LA, Okinaka RT, Jackson PJ, Marks JD. 2007. Genetic diversity among botulinum neurotoxin-producing clostridial strains. J Bacteriol 189:818–832. doi: 10.1128/JB.01180-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Keto-Timonen R, Heikinheimo A, Eerola E, Korkeala H. 2006. Identification of Clostridium species and DNA fingerprinting of Clostridium perfringens by amplified fragment length polymorphism analysis. J Clin Microbiol 44:4057–4065. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01275-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Scott VN, Bernard DT. 1982. Heat resistance of spores of non-proteolytic type B Clostridium botulinum. J Food Prot 45:909–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chilled Food Association (CFA). 2006. Best practise guidelines for the production of chilled foods. The Stationery Office, Norwich, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bohrer CW, Cleve BD, Modesto GY. 1973. Thermal destruction of type E Clostridium botulinum: final report. National Canners Association Research Foundation, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Murrell WG, Scott WJ. 1966. The heat resistance of bacterial spores at various water activities. J Gen Microbiol 43:411–425. doi: 10.1099/00221287-43-3-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fernández PS, Peck MW. 1997. Predictive model describing the effect of prolonged heating at 70 to 80°C and incubation at refrigeration temperatures on growth and toxigenesis by non-proteolylic Clostridium botulinum. J Food Prot 60:1064–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lynt RK, Kautter DA, Solomon HM. 1983. Effect of delayed germination by heat-damaged spores on estimates of heat resistance of Clostridium botulinum types E and F. J Food Sci 48:226–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1983.tb14829.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Advisory Committee on the Microbiological Safety of Food (ACMSF). 1992. Report on vacuum packaging and associated processes. Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, United Kingdom: http://www.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/mnt/drupal_data/sources/files/multimedia/pdfs/acmsfvacpackreport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Angelotti R. 1970. The heat resistance of Clostridium botulinum type E in food, p 404–409. In Herzberg M. (ed), Proceedings of the First U.S.-Japan Conference on Toxic Microorganisms: Mycotoxins and Botulism Honolulu, HI, 7–10 October 1968 UJNR Joint Panel on Toxic Microorganisms and U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Appleyard J, Gaze JE. 1993. The effect of exposure to sublethal temperatures on the final heat resistance of Listeria monocytogenes and Clostridium botulinum. Technical memorandum no. 683. Campden Food and Drink Research Association, Chipping Campden, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bucknavage MW, Pierson MD, Hackney CR, Bishop JR. 1990. Thermal inactivation of Clostridium botulinum type E spores in oyster homogenates at minimal processing temperatures. J Food Sci 55:372–373, 429. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1990.tb06766.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Crisley FD, Peeler JT, Angelotti R, Hall HE. 1968. Thermal resistance of spores of five strains of Clostridium botulinum type E in ground whitefish chubs. J Food Sci 33:411–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1968.tb03640.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.De Pantoja CAO. 1986. Determination of the thermal death time of Clostridium botulinum type E in crawfish (Procambarus clarkii) tailmeat. Ph.D. thesis. Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Baton Rouge, LA. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Duh Y, Ren T. 1995. Determination of the heat resistance of strain of non-proteolytic Clostridium botulinum type E. Food Sci Taipei 22:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Eklund MW, Poysky FT, Wieler DI. 1967. Characteristics of Clostridium botulinum type F isolated from the Pacific Coast of the United States. Appl Microbiol 15:1316–1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Graikoski JT, Kempe LL. 1964. A study of the effect of ionizing radiation on resistance, germination, and toxin synthesis of Clostridium botulinum spores, types A, B, and E. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI: https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/5195/bac3029.0001.001.pdf?sequence=5&isAllowed=y. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Grecz N, Tang T. 1970. Relation of dipicolinic acid to heat resistance of bacterial spores. J Gen Microbiol 63:303–310. doi: 10.1099/00221287-63-3-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ito KA, Seeger ML, Bohrer CW, Denny CB, Bruch MK. 1970. The thermal and germicidal resistance of Clostridium botulinum types A, B and E spores, p 410–415. In Herzberg M. (ed), Proceedings of the First U.S.-Japan Conference on Toxic Microorganisms: Mycotoxins and Botulism Honolulu, HI, 7 to 10 October 1968 UJNR Joint Panel on Toxic Microorganisms and U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Juneja VK, Eblen BS, Marmer BS, Williams AC, Palumbo SA, Miller AJ. 1995. Thermal resistance of non-proteolytic type B and type E Clostridium botulinum spores in phosphate buffer and turkey slurry. J Food Prot 58:758–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kralovic RC. 1973. Clostridium botulinum type E spores: increased heat resistance through lysozyme treatment, abstr G91, p 41. Abstr 73rd Annu Meet Am Soc Microbiol. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Licciardello JJ. 1983. Botulism and heat processed seafoods. Mar Fish Rev 45:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lynt RK, Solomon HM, Lilly T, Kautter DA. 1977. Thermal death time of Clostridium botulinum type E in meat of the blue crab. J Food Sci 42:1022–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1977.tb12658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lynt RK, Kautter DA, Solomon HM. 1979. Heat resistance of non-proteolytic Clostridium botulinum type F in phosphate buffer and crabmeat. J Food Sci 44:108–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1979.tb10018.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mann JB. 1966. Heat resistance of Clostridium botulinum type E and the effect of nisin on heat damaged spores of Clostridium botulinum type E. Ph.D. thesis Department of Food Science and Technology, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 83.National Canners Association (NCA). 1966. Thermal destruction of Clostridium botulinum type E. National Canners Association, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Notermans S, Dufrenne J, Lund BM. 1990. Botulism risk of refrigerated, processed foods of extended durability. J Food Prot 53:1020–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ohye DF, Scott WJ. 1957. Studies in the physiology of Clostridium botulinum type E. Aust J Biol Sci 10:85–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rhodehamel EJ, Solomon HM, Lilly T, Kautter DA, Peeler JT. 1991. Incidence and heat resistance of Clostridium botulinum type E spores in menhaden surimi. J Food Sci 56:1562. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1991.tb08640.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Roberts TA, Ingram M, Skulberg A. 1965. The resistance of spores of Clostridium botulinum type E to heat and radiation. J Appl Bacteriol 28:125–141. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Solomon HM, Lynt RK, Lilly T, Kautter DA. 1977. Effect of low temperatures on growth of Clostridium botulinum spores in meat of blue crab. J Food Prot 40:5–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Stringer SC, Peck MW. 1997. Combinations of heat treatment and sodium chloride that prevent growth from spores of non-proteolytic Clostridium botulinum. J Food Prot 60:1553–1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schmidt CF. 1964. Spores of Clostridium botulinum: formation, resistance, germination. Botulism: Proceedings of a Symposium Cincinnati, OH, 13–15 January 1964 Public Health Service, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.