Abstract

OLA1, an Obg-family GTPase, has been implicated in eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2)-mediated translational control, but its physiological functions remain obscure. Here we report that mouse embryos lacking OLA1 have stunted growth, delayed development leading to immature organs—especially lungs—at birth, and frequent perinatal lethality. Proliferation of primary Ola1−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) is impaired due to defective cell cycle progression, associated with reduced cyclins D1 and E1, attenuated Rb phosphorylation, and increased p21Cip1/Waf1. Accumulation of p21 in Ola1−/− MEFs is due to enhanced mRNA translation and can be prevented by either reconstitution of OLA1 expression or treatment with an eIF2α dephosphorylation inhibitor, suggesting that OLA1 regulates p21 through a translational mechanism involving eIF2. With immunohistochemistry, overexpression of p21 protein was detected in Ola1-null embryos with reduced cell proliferation. Moreover, we have generated p21−/− Ola1−/− mice and found that knockout of p21 can partially rescue the growth retardation defect of Ola1−/− embryos but fails to rescue them from developmental delay and the lethality. These data demonstrate, for the first time, that OLA1 is required for normal progression of mammalian development. OLA1 plays an important role in promoting cell proliferation at least in part through suppression of p21 and organogenesis via factors yet to be discovered.

INTRODUCTION

OLA1 belongs to the translation-factor-related (TRAFAC) class, Obg family, and YchF subfamily of P-loop GTPases (1–3). The TRAFAC GTPases include not only translation factors and ribosome-associated proteins but also proteins that are involved in signal transduction, intracellular transport, and stress responses (1, 2). The YchF/OLA1 proteins are highly conserved from bacteria to humans, and unlike other Obg family members, they possess both GTPase and ATPase activities (4–6). We recently revealed that human OLA1 is a eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2)-regulatory protein that suppresses protein synthesis and enhances the integrated stress response (ISR) by binding eIF2 and interfering with the formation of the eIF2-GTP-Met-tRNAiMet (ternary) complex (6).

It is currently unclear whether YchF/OLA1 proteins are essential for life. Whereas most null mutations of the YchF homologue in yeasts are nonlethal (7), inactivation of TcYchF by RNA interference (RNAi) in trypanosomes (Trypanosoma cruzi) inhibited the protozoan's growth (4). We (6) and others (8) reported that OLA1 knockdown (KD) in human cells under normal culture conditions had, depending on the origin of the cell lines used, either a negative effect or no effect on cell proliferation. However, under multiple cellular stresses, including oxidative stress, OLA1 KD promoted cell survival (9) by “gating” ISR and the expression of downstream proapoptotic factors, such as CHOP (6). These paradoxical findings suggest that OLA1 plays multiple roles in the regulation of cell proliferation and cell survival. This provides a compelling rationale for additional study using a more robust and relevant model, such as null mutation, to characterize OLA1 function in a higher mammalian organism.

We present here the first analysis of Ola1-null mice, showing that they are small for their gestational age (SGA), with high perinatal lethality due to lung immaturity. This phenotype, which is related to growth retardation and development delay, was mediated by a reduced rate of cell proliferation. The underlying cause was an impaired cell cycle progression, which at the molecular level was associated with reduced G1/S-specific cyclins and increased cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor (CKI) p21. We further demonstrated that the accumulation of p21 was caused by the increased translation of p21 mRNA through an eIF2-dependent mechanism. These findings point to OLA1 as a novel translational regulator of p21 and as a pivotal player in cell proliferation and in the growth and development of the whole organism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of mouse strains carrying Ola1 null mutations.

All mice were housed in the vivarium facility at the Houston Methodist Research Institute (HMRI). The animals were allowed access to food and water ad libitum and maintained in a 12-h/12-h light/dark cycle. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of HMRI. The first Ola1 mutant strain, which was bred in a mixed 129/Sv × C57BL/6 genetic background, was constructed using a gene trapping strategy and obtained from the Texas A&M Institute for Genomic Medicine (TIGM; Houston, TX). A gene trap retroviral vector (Omni Bank VICTR48) (10) was inserted at the 6th exon or the 5th coding exon of the Ola1 gene (Fig. 1A). Gene disruption was verified using PCR and sequencing. Mice were genotyped using a standard PCR method with the following primers: wild-type (WT) forward (Fwd1), 5′-TTAGGATACGCCCCATTTCATACT-3′; mutant forward (Fwd2), 5′-AAATGGCGTTACTTAAGCTAGCTTGC-3′; and reverse (Rev), 5′-TCCAGTCATGATAGAAGCGAACAG-3′. The heterozygous mutant mice were backcrossed with C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) for 10 successive generations, which resulted in an Ola1+/− congenic strain. A third Ola1 knockout strain was generated using a Cre-loxP strategy. Based on a C57BL/6 mouse BAC genomic clone that contained the Ola1 locus (RP23-20B20), a targeting vector was constructed to introduce one loxP site into intron 1 and another loxP site that was linked to an FRT-PGK-neo-FRT cassette (neomycin resistance gene expressed from the PGK promoter; FRT is the Flp recombination target) into intron 2 (Fig. 1B). Embryonic stem (ES) cells with a C57BL/6 origin were targeted with the vector and selected using neomycin. Correct targeting events were confirmed using Southern blot analysis with 5′ and 3′ external probes, and the presence of the 5′ loxP site was further verified by PCR of the nearby region and digestion of the PCR product to determine the presence of Afl2, a rare-cutting cloning site that was fused to the loxP sequence (Fig. 1B). After confirmation of germ line transmission, offspring that were heterozygous for the loxP-flanked Ola1 allele containing the PGK-neo cassette were bred with ACTB-Flp transgenic mice (11) to remove the neo cassette. Mice heterozygous for an Ola1 floxed allele that did not contain the neo cassette are referred to as Ola1f/+. By breeding these mice to wild-type C57BL/6 mice, the Flp transgene was eliminated. Removal of neo and Flp was confirmed using PCR. The Ola1f/+ mice were intercrossed to generate Ola1f/f mice. The Ola1f/f mice were then bred with EIIa-Cre mice (Jackson Laboratory; no. 3724), which express widespread Cre recombinase under the control of the adenovirus EIIa promoter, to induce germ line deletion of the floxed allele resulting in the Ola1f/− mice, which were heterozygous for the deletion of exon 2 (12). The Ola1f/− mice were backcrossed with the Ola1f/f mice to select Ola1f/− offspring that were negative for the EIIa-Cre transgene. Genotyping of the Ola1f/f, Ola1f/−, Ola1−/− mice was performed using PCR with the following primers: either 20189 forward (5′-AGTTCCTCGTAGGTTCCTGTTGCAGTG-3′) or 20999 forward (5′-GGAGGAGATGGAATTAAACCGCCTCCAA-3′) and the common 22031 reverse primer (5′-GTGAGCGTCATAAACCCATGCTGTGTC-3′). For the generation of Ola1−/−/p21−/− double knockout (DKO) mice, the Ola1+/− (C57BL/6) mice were bred with p21−/− mice [B6.129S6(Cg)-Cdkn1atm1Led/J; Jackson Laboratory; no. 016565] to produce the double heterozygous Ola1+/−/p21+/− mice. These were intercrossed to produce F2 mice (with a theoretical rate of 1/16 to be a DKO). The Ola1+/−/p21−/− mice were further interbred to generate F3 mice (with a theoretical rate of 1/4 to be a DKO). The Ola1f/f mice are available at The Jackson Laboratory as stock no. 029493.

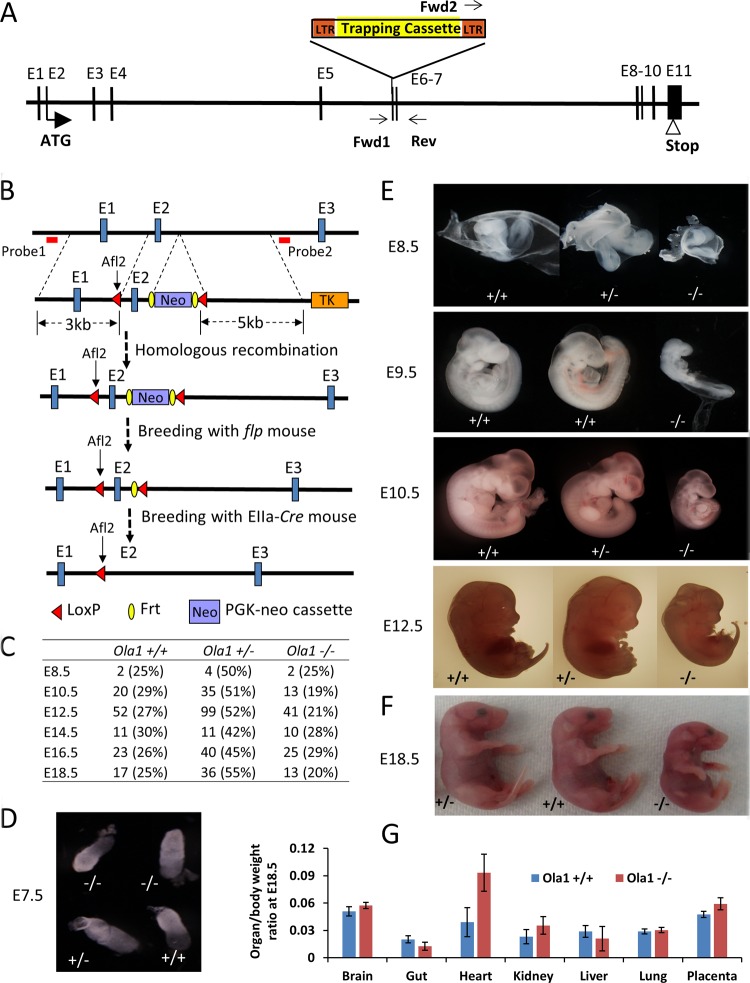

FIG 1.

Targeted disruption of Ola1 causes growth retardation and developmental delay. (A) Gene trapping at the Ola1 locus. A retroviral vector (Omni Bank VICTR48) was inserted at exon 6 (E6, or the 5th coding exon) of the Ola1 gene. This insertion was identified using PCR with primers Forward 1, Forward 2, and Reverse, as indicated. LTR, long terminal repeat. (B) Deletion of exon 2 (E2) using a Cre-loxP strategy. A targeting construct was designed to introduce a loxP site to intron 1 and a PGK-neo cassette flanked by FRT that was linked to the 2nd loxP (top). It also contained a 3-kb 5′ homology arm, a 5-kb 3′ arm, and the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (TK) gene, which was used as a negative selection marker. The positions of the 5′ and 3′ external probes that were used for Southern blot analysis are shown as red bars. The first loxP was fused with a rare-cutting restriction enzyme site (Alf2), and the presence of this site was identified using Southern blot analysis or PCR followed by Alf2 digestion. The FRT-PGK-neo-FRT cassette served as the positive selection marker. The correctly targeted ES cells, carrying the knock-in allele, were used to produce mice heterozygous for the allele (2nd panel). By breeding these mice with flpe transgenic mice, the neo gene was deleted, resulting in floxed mice (Ola1f/+) (3rd panel). Finally, by breeding Ola1f/f mice with EIIa-Cre mice, mice heterozygous for the Cre-recombined allele (Ola1f/−) were generated (bottom panel). (C) Genotypes of the progeny of Ola1 heterozygous intercrosses. Shown are the numbers of embryos observed, with the percentages shown in parentheses. (D to F) Morphological examination of Ola1+/+, Ola1+/−, and Ola1−/− embryos at E7.5 (D), from E8.5 to E12.5 (E), and at E18.5 (F). (G) Ratios of organ weight to body weight are shown for various internal organs and the placenta for E18.5 Ola1+/+ and Ola1−/− fetuses. The data are presented as the means ± SEMs (n = 8 to 16).

Animal and embryo studies.

Timed matings were set up by housing a single male with one or two females. At the designated embryonic age, pregnant females were euthanized using CO2 asphyxiation and the embryos were dissected for morphological and histopathological analyses. Yolk sacs or tail tissues were recovered at the same time to assess genotypes. To assess the incorporation of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU), females were injected with BrdU (50 mg/kg of body weight) 2 h before they were euthanized. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were isolated from embryonic day 12.5 (E12.5) or E14.5 embryos as previously described (13) and immortalized using a serial subculturing method (for >30 passages). To analyze postnatal growth, littermates from Ola1+/− matings were weighed at weaning age (21 days) and every 2 weeks afterward. Adult mouse skin fibroblasts (MSFs) were obtained from age-matched (6 to 12 weeks) and gender-matched Ola1+/+ and Ola1−/− mice. A piece of skin approximately 0.5 cm in diameter was surgically removed from the back of each animal, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), minced into small pieces, and seeded in a collagen IV-coated plate (BD Biosciences) containing Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). When the outgrowth of the fibroblasts reached 85% confluence (usually in 7 to 10 days), the cultures were trypsinized, and the isolated fibroblasts were reseeded in collagen IV-coated plates and allowed to grow to approximately 90% confluence (P1).

Histology and IHC.

Embryonic tissues were fixed in a 10% formalin–PBS solution, dehydrated, paraffin embedded, sectioned, and subjected to hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, immunohistochemistry (IHC), or special staining with the assistance of the HMRI Research Pathology Core. For IHC, the following antibodies were used: p53 (catalog number ab131442; Abcam), SP-C (C-19) (catalog number sc-7705; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), p21 (catalog number ab80635; Abcam), or BrdU (catalog number 5292; Cell Signaling Technology). To evaluate glycogen levels, sections were stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) reagent (catalog number 395B; Sigma-Aldrich). To detect apoptosis, a terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay kit (Roche) was used according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Cell growth and cell cycle analysis.

To generate growth curves, 5 × 104 MEFs (P2-P3) or 1 × 105 MSFs (P2) were seeded in 6-well plates and counted every 24 h using an automated cell counter (Nexcelom Bioscience). To analyze cell cycles, MEFs (P2-P3) were first cultured in serum-free medium for 72 h to induce cell cycle arrest and then released via incubation in full medium (containing 10% FBS) for the desired times. Cells were collected, washed with PBS, and fixed in 70% ethanol at −20°C for at least 2 h. The fixed cells were washed twice with PBS, stained with a propidium iodide (PI) solution (BD Pharmingen) for 15 min, and analyzed using flow cytometry (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed using the Multicycle AV feature in FCS Express 4 (DeNovo Software). For cell size measurements, fixed MEFs were washed, resuspended in 1 g/ml of PI in PBS, and then subjected to flow cytometry. Cell sizes were estimated using a forward light scatter (FSC) parameter.

BrdU incorporation assay.

MEFs (P2-P3) were seeded in 96-well plates, deprived of serum, and restored in serum-containing medium for 16 h. Cells were labeled with BrdU for 2 h. The incorporation of BrdU was analyzed using a colorimetric BrdU incorporation immunoassay (catalog number QIA58; EMD Millipore) according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer.

Immunoblotting analysis.

Immunoblotting analyses were performed as previously described (6). Briefly, equal amounts of protein were loaded in a 4 to 20% gradient polyacrylamide gel (Invitrogen) and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. The membrane was blocked with a 5% nonfat milk solution and sequentially incubated with a primary antibody and an enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody. Bands were visualized using a chemiluminescence system according to the manufacturer's guidelines (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The antibodies used in these analyses were purchased from the following suppliers: OLA1 (catalog number HPA035790), β-actin (catalog number A1978), and α-tubulin (catalog number T8328) from Sigma-Aldrich; cyclin D1 (catalog number sc-20044), cyclin E1 (catalog number sc-481), anti-goat IgG, and peroxidase-linked whole antibody (catalog number sc-2922) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; eIF2α (catalog number 5324), p-eIF2α (S51) (catalog number 3398), ATF4 (catalog number 11815), cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2; catalog number 2546), CDK6 (catalog number 3136), p21Waf1/Cip1 (catalog number 2947), p53 (catalog number 2524), p-Rb (S780) (catalog number 8180), and Rb (catalog number 9303) from Cell Signaling Technology; cyclin B1 (catalog number ab18219) from Abcam; and anti-rabbit (catalog number NA934) and anti-mouse IgG (catalog number NXA931) peroxidase-linked whole antibodies from GE Healthcare. Relative band intensities were estimated using densitometric quantification in ImageJ (NIH).

qRT-PCR.

Total cellular RNA was isolated from MEFs using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen). One microgram of RNA was reverse transcribed using amfiRivert Platinum cDNA synthesis master mix (GenDEPOT). Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using iTaq Universal SYBR green Supermix (Bio-Rad) in a C1000 Touch thermal cycler (Bio-Rad). mRNA levels were analyzed using the relative quantification method based on the threshold cycle (CT) values that were obtained for the genes of interest and the internal control (β-actin or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase [GAPDH]). The following primers were used: p21 forward (5′-CCAGTTGGGGTTCTCAGTGACTTC-3′) and reverse (5′-TCAGCCATTGCTCAGTGTCCTG-3′), p53 forward (5′-ACATGACGGAGGTCGTGAGA-3′) and reverse (5′-TTTCCTTCCACCCGGATAAG-3′), ccnd1 forward (5′-TGTTCGTGGCCTCTAAGATGAAG-3′) and reverse (5′-AGGTTCCACTTGAGCTTGTTCAC-3′), β-actin forward (5′-AGTGTGACGTTGACATCCGT-3′) and reverse (5′-TGCTAGGAGCCAGAGCAGTA-3′), and GAPDH forward (5′-AAGGTCATCCCAGAGCTGAA-3′) and reverse (5′-CTGCTTCACCACCTTCTTGA-3′).

Polysome profiling analysis.

Briefly, Ola1+/+ and Ola1−/− MEFs were cultured in full or serum-deprived medium overnight. A solution of 100 μg/ml of cycloheximide was added to the cells 10 min before cell lysis. Cell lysates were analyzed using polysome profiling as previously described (6). Total RNA was precipitated from the fractions in ethanol and purified using an RNA minikit (Qiagen). Relative amounts of p53, p21, ccnd1, and β-actin mRNAs from each fraction were measured using qRT-PCR. The primers used for these assays are described above.

Cell transfection.

The restoration of Ola1 expression in Ola1−/− MEFs was performed by transfecting Ola1 mRNA. Briefly, 1 × 105 Ola1−/− MEFs were seeded in 6-well plates and allowed to grow overnight. Cells were then transfected with modified mRNAs (mmRNAs) encoding human full-length human Ola1 (NM_013341) and/or mmRNAs encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP) using a TransIT-mRNA transfection kit (Mirus Bio) according to the manufacturer's instructions. mmRNAs, carrying a modified 5′ untranslated region (UTR), 3′ UTR, and a poly(A) tail (14), were synthesized in the RNA Core of HMRI. Cells were harvested 24 h after transfection for protein analysis.

Statistical analysis.

All in vitro data were analyzed using two-tailed Student's t tests. Animal body weight curves were analyzed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni posttests. A P value of <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Ola1-null mutation causes embryonic growth retardation and incomplete perinatal lethality.

The first Ola1-targeting mouse line was made possible by the insertion of a retroviral vector at the 5th coding exon of the Ola1 gene (Fig. 1A). These mice were bred in a 129sv × C57BL/6 genetic background. Mice heterozygous for Ola1 disruption (Ola1+/−) are viable, fertile, and indistinguishable from Ola1+/+ (WT) mice. However, a large majority (80%) of the Ola1−/− mice was found dead within 24 h of birth (P0) (Table 1). All of the dead Ola1−/− pups were smaller than their Ola1+/+ and Ola1+/− littermates and had cyanosis, which is suggestive of respiratory distress. To define the time and cause of the lethality, embryos obtained from timed matings of heterozygous parents were genotyped and examined. Ola1−/− embryos were found at the expected ratio up through E18.5 of gestation (Fig. 1C), indicating that death occurred perinatally. From E8.5 onward, Ola1−/− embryos were significantly smaller than their Ola1+/+ and Ola1+/− littermates (Fig. 1D and E), and as measured on E18.5, they showed a decrease in body weight by 35% (Fig. 1F). At E18.5, various organs, including the brain, heart, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, and kidneys, as well as the placenta, were dissected and weighed (Fig. 1G). The resulting ratios of organ (or placenta) weight to body weight were comparable between the Ola1+/+ and Ola1−/− fetuses, except that hearts of the latter trended toward a higher weight. However, this trend was not statistically significant. Therefore, the small-size phenotype represented a proportionate restriction in growth.

TABLE 1.

Genotype analysis of offspring from Ola1 heterozygous intercrosses

| Genetic background | Actual no. of mice (%) | Theoretical no. of mice (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Aa | ||

| Ola1+/+ | 545 (30) | 458.5 (25) |

| Ola1+/− | 1,196 (65) | 917 (50) |

| Ola1−/− | 93 (5) | 458.5 (25) |

| Bb | ||

| Ola1+/+ | 70 (38) | 46 (25) |

| Ola1+/− | 109 (60) | 92 (50) |

| Ola1−/− | 4 (2) | 46 (25) |

| Cc | ||

| Ola1f/f | 9 (31) | 7.25 (25) |

| Ola1f/− | 20 (69) | 14.5 (50) |

| Ola1−/− | 0 (0) | 7.25 (25) |

129sv × C57BL/6; targeting strategy, gene trapping.

C57BL/6 (backcrossed from mice of genetic background A).

C57BL/6; targeting strategy, Cre-loxP.

Ola1-null embryos have delayed progression of development.

Ola1−/− embryos not only were small but also looked “younger” than their littermates (Fig. 1E). At E7.5, embryos of all genotypes were indistinguishable (Fig. 1D). Starting on E8.5, developmental hallmarks of the homozygous mutants exhibited a uniform and constant delay of 0.75 to 1.0 day. These included a lack of branchial arches at E8.5, deficiency in somite pairs at E9.5, the absence of hind limb buds and lens plates at E10.5, and the absence of a liver bud and retinal pigmentation at E12.5 (Fig. 1E).

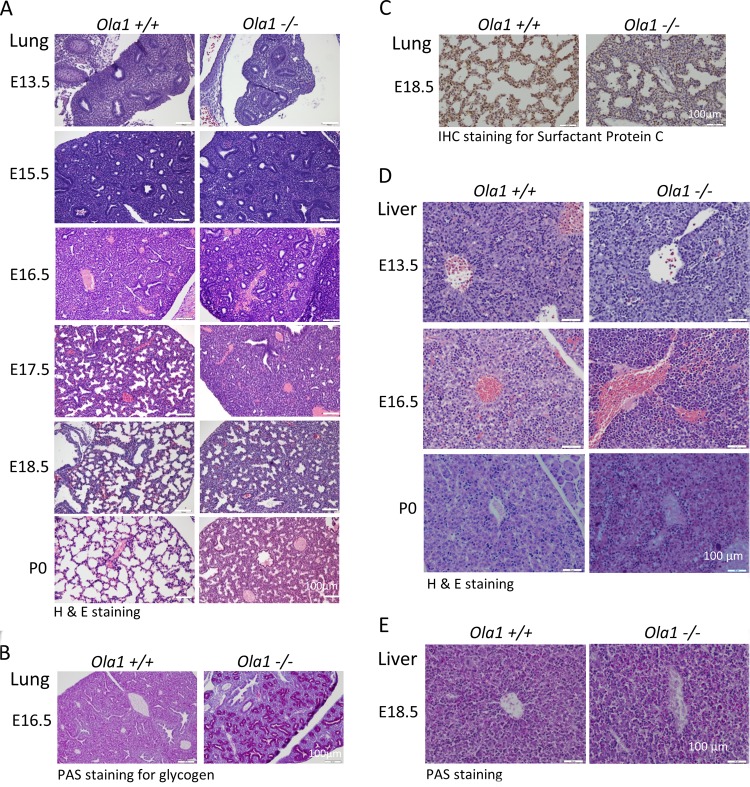

To further characterize the developmental abnormalities in these mice, histological analyses were performed on various stages of fetuses and neonates. H&E-stained lung sections were first examined (Fig. 2A). At E13.5, both Ola1+/+ and Ola1−/− lungs showed features of the pseudoglandular stage of embryonic lung development with no obvious differences. However, at E15.5, when Ola1+/+ lungs entered the late pseudoglandular stage and gained many small epithelial tubes, which represent the development of a finer brachial architecture, Ola1−/− lungs displayed fewer and larger epithelial tubes and had a more sponge-like appearance. Over the next 3 days, the lungs of Ola1+/+ controls sequentially advanced to the canalicular and saccular stages, during which they showed the maturation of terminal airspaces (precursors of alveoli) from sporadic canal-like openings (E16.5) into sac-like structures, in addition to the widening of the airspace and the thinning of the surrounding mesenchyme (primary septae) (E17.5 to E18.5). Strikingly, the morphology of Ola1−/− lungs at E16.5, E17.5, and E18.5 was essentially identical to that of control lungs at E15.5, E16.5, and E17.5, respectively, suggesting that the mutants were 1.0 day behind in lung development (Fig. 2A). The differences at E16.5 were even more distinctive in periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining: while Ola1+/+ lungs were homogeneously stained, Ola1−/− lungs showed highlighted epithelial tubes lined with bronchial epithelial cells that were strongly positive for glycogen (Fig. 2B). Moreover, immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of E18.5 Ola1−/− lungs showed a decreased proportion of cells that were positive for surfactant protein C (SP-C), indicating a decrease in mature type II pneumocytes (Fig. 2C). Between E18.5 and birth (P0), no obvious “catch-up” was observed in the maturation of distal saccules in Ola1−/− mice. Compared to those of euthanized wild-type pups, all of the dead Ola1−/− pup lungs failed to inflate and exhibited markedly reduced saccular space and thicker interstitial mesenchyme (Fig. 2A). This lung immaturity may explain the respiratory distress and neonatal death that were frequently observed in the Ola1−/− pups.

FIG 2.

Phenotypic analysis of Ola1+/+ and Ola1−/− embryos. (A) H&E staining of Ola1+/+ and Ola1−/− lungs from E13.5 to E18.5 embryos and pups on the day of birth (P0). (B) Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining of lungs sections from E16.5 embryos. (C) Immunohistochemical staining with the antibody against SP-C in lung sections from E18.5 embryos. The nuclei were counterstained using eosin. (D) H&E-stained histological sections of livers obtained from Ola1+/+ and Ola1−/− embryos at E13.5 and E16.5 and from neonates (P0). (E) PAS staining of liver sections of embryos obtained at E16.5.

Retardation of organogenesis was not limited to the lungs. When liver sections were evaluated at various embryonic stages, a delay in hepatic hematopoiesis was observed in developing Ola1−/− livers (Fig. 2D). In E13.5 WT livers, the hematopoietic compartment, predominantly the erythroblasts, made up more than half of the total volume, demonstrating that this is the peak stage of hematopoiesis. Nucleated erythrocytes (RBCs) were observed within vessels and throughout the liver. In the Ola1−/− livers, however, hematopoietic cells were significantly less prevalent, and there were only a few scattered RBCs. Three days later (E16.5), in the WT livers, while the hematopoietic population declined, hepatocytes came into more contact with one another. However, E16.5 Ola1−/− livers were still dominated by hematopoietic cells, such as erythroblasts and megakaryocytes. Unlike the RBCs observed in WT livers, which had extruded their nuclei, the RBCs in the Ola1−/− livers were still nucleated. At birth (P0), Ola1−/− livers displayed less maturity than the livers in the controls, as demonstrated by a higher number of hematopoietic cells, including megakaryocytes, and the poor formation of hepatic cords from contacted hepatocytes (Fig. 2D). However, this liver phenotype may not cause neonatal death. As assessed at E18.5, Ola1−/− hepatocytes have glycogen storage at a level comparable to that of the control cells (Fig. 2E). In E18.5 Ola1−/− fetuses, no obvious developmental abnormalities were observed in the other organs that were examined, including the brain, heart, digestive system, and kidneys, except that they were reduced in size.

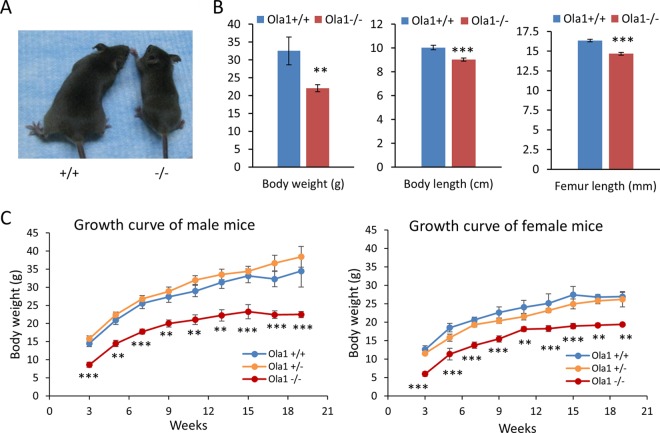

Ola1-null mice that survive to adulthood are small.

We also observed that a small proportion of Ola1−/− mice were viable and lived to adulthood. If these mice survived the first day after birth, they displayed a viability comparable to those of their WT and Ola1+/− littermates and lived up to 2 to 2.5 years. However, almost all surviving Ola1−/− mice were notably smaller (Fig. 3A and B). At weaning age (3 weeks), their average body weight was about half the weight of the WT mice (Fig. 3C). They appeared to have a comparable growth rate in terms of gaining both body weight and length until they reached their maximal adult body sizes at 3 to 4 months. At the end of a 19-week observation period, the average weights of male and female Ola1−/− mice were 65% and 72% those of their gender-matched WT controls, respectively (Fig. 3C). However, both male and female Ola1−/− mice showed gains in body lengths of up to 90% of the gains observed in controls. They had a femur length that was 10% shorter than the length in controls (Fig. 3B). Hence, they did not meet the criteria to be classified as dwarfs. In addition, fertility was analyzed in 3 male and 3 female Ola1−/− mice. All of them were fertile; however, they displayed a possible reduction in productivity in terms of litter size.

FIG 3.

Growth retardation in Ola1−/− mice. (A) Shown is an image of representative male mice at 5 weeks old. (B) Body weight, length, and femur length measurements were taken from 5- to 8-month-old mice (equal numbers of males and females). Data are presented as the means ± SEMs; n = 8 to 16 for each genotype and each measurement. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (C) Growth curves for male and female Ola1+/+, Ola1+/−, and Ola1−/− mice from 3 to 19 weeks of age. Body weights were measured for 3 to 8 mice at each time point for each genotype. Error bars represent the SEMs. Two-way ANOVA for the effect of genotype on body weight: F(2,125) = 128.18 and P < 0.0001 (male mice); F(2,109) = 93.70 and P < 0.0001 (female mice). **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 (compared to value for Ola1+/+ mice; Bonferroni posttests.

To rule out variations that could be caused by genetic background or gene targeting approaches, the above-described 129sv × C57BL/6 mice were backcrossed with C57BL/6 mice. The resulting Ola1+/− mice in the theoretically pure C57BL/6 background were then intercrossed. Among their offspring, only 10% of the expected Ola1−/− mice were viable at birth, and these lived to adulthood (Table 1). All surviving Ola1−/− mice were small: they had body weight that was one-third of the weight of controls at weaning age and one-half of the weight of controls at adulthood. Finally, using a Cre-loxP strategy, we generated another line of C57BL/6 mice, which we here refer to as Ola1f/− (Fig. 1B), in which the first coding exon (containing the ATG codon) of the Ola1 gene was flanked by loxP sites and excised by EIIa-promoted Cre from one of the alleles (see Materials and Methods). The initial breeding cycle of these Ola1f/− mice produced 29 live pups without an Ola1−/− mouse, whereas 2 dead P0 pups were confirmed to be Ola1−/− (Table 1). We concluded that perinatal lethality is a consistent phenotype of Ola1-null mutations.

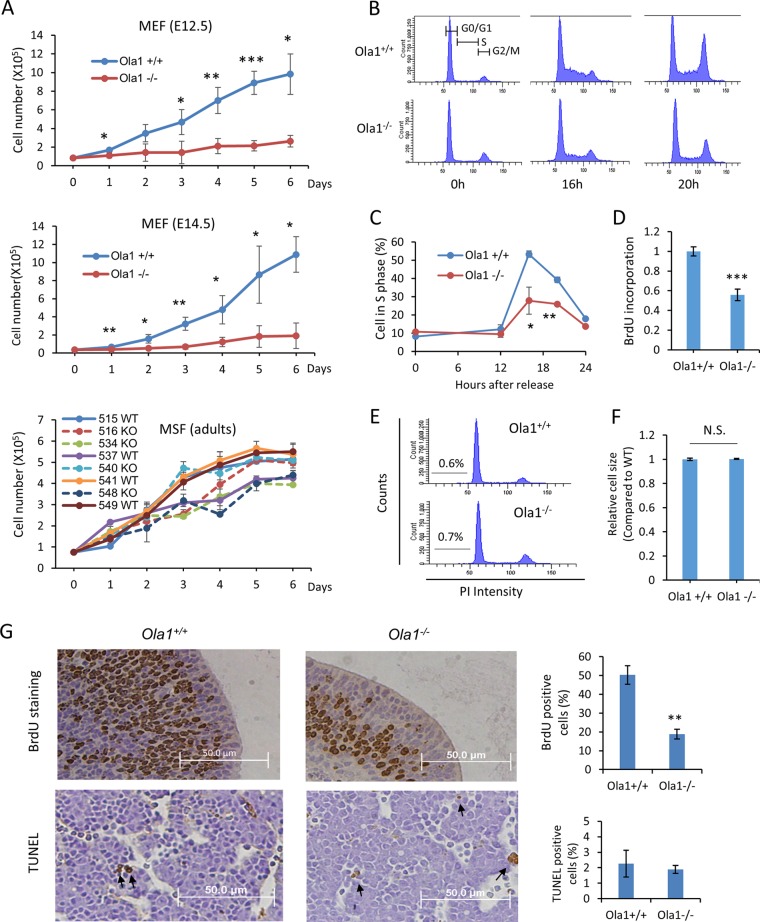

Ola1-null MEFs and embryos have decreased cell proliferation.

To interpret the growth retardation phenotype observed in the knockout embryos, we generated primary MEFs from E12.5 and E14.5 Ola1−/− embryos and their littermate controls. We analyzed growth curves in early-passage (P2-P3) MEFs that were prepared from E12.5 and E14.5 (Fig. 4A) embryos and found that Ola1−/− cells from both preparations showed severe impairments in growth (cell numbers) compared to Ola1+/+ cells. Next, cell cycle profiles were analyzed using flow cytometry (Fig. 4B). MEFs were synchronized in G0/G1 phase by serum starvation and released at 0 h. The Ola1−/− MEFs showed significantly decreased G1-to-S transition (Fig. 4B). At 16 h after serum restoration, while 53% of the Ola1+/+ MEFs entered S phase, only 28% of the Ola1−/− MEFs did so (Fig. 4C). The reduced number of Ola1−/− MEFs in S phase was corroborated by analysis of BrdU incorporation at 16 h post-serum stimulation (Fig. 4D). The Ola1−/− MEFs also showed increased G2/M cells at 0 h and decreased G2/M cells at 20 h, indicating additional defects in the G2/M phases (Fig. 4B). In parallel with these experiments, we estimated cell apoptosis by measuring the sub-G1 population using flow cytometry and found that both the Ola1+/+ and Ola1−/− MEFs underwent very low levels of apoptosis. There was no difference between the two populations (Fig. 4E). These data suggest that the reduced growth in Ola1−/− cells resulted from reduced cell proliferation due to impaired cell cycle progression rather than increased apoptosis. We also assessed cell size and failed to find a difference in the mean values of cell diameters between Ola1+/+ and Ola1−/− MEFs (Fig. 4F).

FIG 4.

Effects of OLA1 knockout on cell proliferation, cell cycle progression, cell death, and cell size. (A) Growth of primary cultures of Ola1+/+ and Ola1−/− fibroblasts. MEFs were derived from E12.5 (top) or E14.5 (middle) littermates, and mouse skin fibroblasts (bottom) were isolated from adult mice. The MEF data are presented as the means ± SDs (n = 4). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Growth curves for Ola1−/− MSFs are drawn as broken lines, while those for Ola1+/+ MSFs are shown as solid lines. Note that animals with identification numbers of 515/516, 534/537, 540/541, and 548/549 were gender- and age-matched pairs. (B) Cell cycle analysis of E12.5 MEFs. Ola1+/+ (top) and Ola1−/− (bottom) MEFs were synchronized at G0-G1 by serum deprivation for 72 h. After serum stimulation at the indicated times, DNA levels were analyzed using flow cytometry. (C) Percentages of cells in S-phase at indicated times post-serum stimulation. Error bars show SDs (n = 3). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. (D) Cell proliferation in Ola1+/+ and Ola1−/− MEFs was assessed using BrdU incorporation. Cells were restored with serum for 16 h and labeled with BrdU for 2 h. The results are presented as fold differences relative to the Ola1+/+ group. Data are shown as the means ± SDs from three independent experiments. ***, P < 0.001. (E) Apoptosis in Ola1+/+ and Ola1−/− MEFs was assessed by analyzing the proportion of cells in the sub-G1 population, as shown in a flow cytometry histogram. (F) Relative cell sizes in Ola1+/+ and Ola1−/− MEFs were estimated using forward light scatter (FSC) and flow cytometry. Data are presented as the means ± SDs. N.S., no statistical significance. (G) Analyses of cell proliferation and apoptosis in E12.5 embryos in vivo. Cell proliferation was assessed using BrdU incorporation in forebrain sections (top), and apoptosis was assessed using TUNEL in liver sections (bottom). The percentages of cells staining positive using each labeling method are shown as bar graphs. Data are presented as the means ± SEMs. **, P < 0.01.

Moreover, cell proliferation in vivo was evaluated in E12.5 embryos using BrdU incorporation. The number of BrdU-positive cells in every tissue, e.g., the forebrain, was significantly smaller in the Ola1−/− embryos than the number observed in Ola1+/+ embryos (Fig. 4G). However, no difference was observed in apoptosis, as assessed using TUNEL staining, between the same two groups of embryos. Apoptotic cells were detected sporadically throughout the embryos of both genotypes (Fig. 4G). Finally, to analyze cell proliferation in the surviving adult mice, primary mouse skin fibroblasts (MSFs) were cultured ex vivo. Three of the four lines of Ola1−/− MSFs showed growth retardation compared to growth in gender- and aged-matched Ola1+/+ MSFs (Fig. 4A).

Cell cycle regulators are altered in Ola1-null cells.

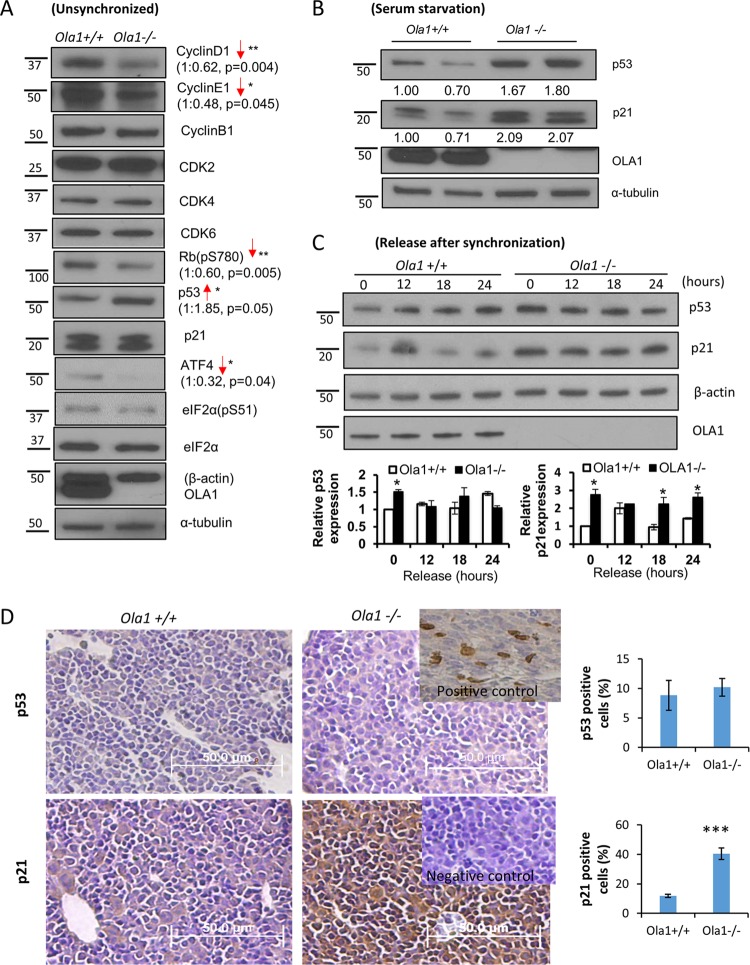

To determine the molecular mechanisms underlying the delayed cell cycle progression observed in the Ola1-null mice, we examined various cell cycle regulators, including cyclins, CDKs, Rb, the CDK inhibitor p21cip1, and p53. We first analyzed asynchronously growing MEFs (E12.5). Compared to the Ola1+/+ MEFs, Ola1−/− cells showed markedly decreased levels of the cyclin D1 and E1 proteins and decreased Rb phosphorylation (Ser-780), which represents the molecular basis underlying cell cycle arrest at G1/S (Fig. 5A). However, no notable difference was found on the G2/M phase-specific cyclins, such as cyclin B1. Of the upstream negative regulators of the cell cycle, the p53 protein was found to be increased in the Ola1−/− MEFs, whereas p21 levels were either unchanged (Fig. 5A) or increased (Fig. 5B). However, after the MEFs were serum starved overnight, both the p53 and p21 proteins were consistently elevated in the Ola1−/− cells (Fig. 5B). In the next set of experiments, MEFs were serum starved for 24 h to further synchronize the cells at the G0-G1 phase (15) and then analyzed to observe the dynamics of p53 and p21 levels following serum restoration (0 ∼ 24 h). Both p53 and p21 were markedly increased in the Ola1−/− cells at time zero, and unlike the Ola1+/+ cells, which exhibited a sharp drop in p21 between 12 h and 18 h (a prerequisite for the G1-to-S transition), the Ola1−/− cells did not display a downregulation of p21 (Fig. 5C). These data were interpreted to indicate that the accumulation of p53 and/or p21 may contribute to the cell cycle arrest observed in primary Ola1−/− MEFs.

FIG 5.

Alterations in cell cycle regulators in OLA1 knockout MEFs. (A) Levels of cell cycle regulators and related proteins in Ola1+/+ and Ola1−/− MEFs were analyzed using immunoblotting. α-Tubulin was used as the loading control. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (n = 3). (B) Levels of p53, p21, and OLA1 proteins in Ola1+/+ and Ola1−/− MEFs following overnight serum starvation were evaluated using immunoblotting. α-Tubulin was used as the loading control. (C) Levels of p53 and p21 proteins in Ola1+/+ and Ola1−/− MEFs that were serum starved for 24 h and restored with serum at the indicated times are shown. β-Actin was used as the loading control. Quantitative analyses of the relative band intensities are shown as bar graphs (means ± SDs) under the gel images. *, P < 0.05 (n = 3). Numbers on the left in panels A to C are molecular masses, in kilodaltons. (D) Expression of the p53 and p21 proteins in E12.5 embryos as shown by IHC staining of liver sections with a p53 antibody (top) or a p21 antibody (bottom). (Upper right inset) Positive control showing p53 staining in a liver section obtained from an E18.5 WT embryo. (Lower right inset) Negative control showing p21 staining in an adjacent section stained without the primary antibody. The percentages of cells staining positive for p53 or p21 are shown as bar graphs. Error bars show SEMs. ***, P < 0.001 (n = 6).

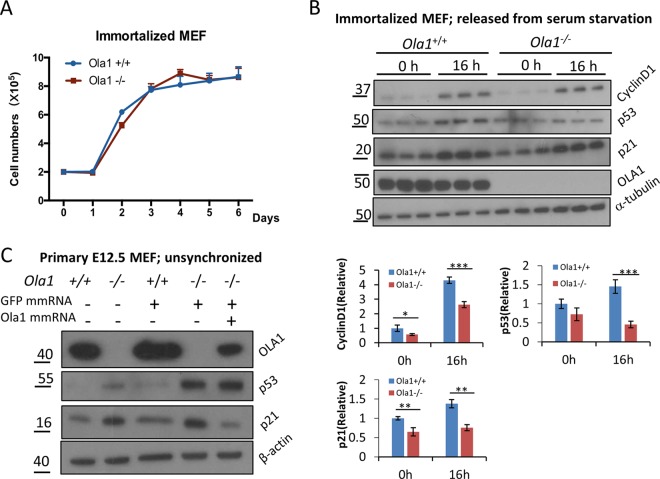

To further test the linkage between p53 and p21 accumulation and cell cycle phenotypes, we tested a pair of spontaneously immortalized MEF lines (see Materials and Methods), in which the Ola1−/− line showed the same growth rate as the Ola1+/+ control line (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, in these mutant cells, the accumulation of p53 and p21 was no longer observed at either time zero of the cell cycle or in S phase (16 h) (Fig. 6B). Instead, at the latter time point, both proteins were markedly reduced in the Ola1−/− MEFs (Fig. 6B). We reasoned that the Ola1−/− MEFs had been rescued from growth retardation because they acquired an adaptive mechanism that blocked the accumulation of p53 and p21.

FIG 6.

Analysis of cell growth and levels of cyclin D1, p53, and p21 in immortalized MEFs. (A) Growth curves for immortalized Ola1+/+ and Ola1−/− MEFs. Data are presented as the means ± SDs (n = 3). (B) Analysis of cyclin D1, p53, and p21 levels in immortalized MEFs. The levels of cyclin D1, p53, p21, and Ola1 proteins in a pair of immortalized Ola1+/+ and Ola1−/− MEFs that were serum starved overnight and then restored using serum for 0 h and 16 h were analyzed using immunoblotting analysis. α-Tubulin was used as the loading control. Quantitative analyses of the relative band intensities for each protein are shown as bar graphs under the gel images. Data are presented as the means ± SDs. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 (n = 3). (C) Restoration of Ola1 expression reverses the accumulation of p21 but not the accumulation of p53. Ola1−/− MEFs were transfected with Ola1 mmRNA and/or GFP mmRNA, and the levels of the p53 and p21 proteins were detected using immunoblotting analysis.

Furthermore, the expression of p53 and p21 in E12.5 embryos was evaluated using IHC. While very low levels of p53 expression were detected in liver sections obtained from both Ola1+/+ and Ola1−/− mice (with no appreciable difference), the number of p21-positive cells markedly increased in the liver sections obtained from Ola1−/− embryos compared to those obtained the Ola1+/+ littermate controls (Fig. 5D). These data suggest that the accumulation of p21, which is likely independent of p53, underlies the growth retardation phenotype observed in the Ola1 knockout embryos. Finally, to validate that OLA1 is a negative regulator of p53 and/or p21 expression, we attempted to “rescue” OLA1 expression in the primary knockout MEFs by transfecting a modified mRNA encoding human OLA1. At best, we were able to express OLA1 at a level equivalent to approximately 20% of that observed in wild-type MEFs (Fig. 6C). Interestingly, these partially rescued cells showed a marked decrease in p21 compared to the results when the same Ola1−/− MEFs were transfected with a control protein (GFP). However, there was no significant change in p53 levels. We therefore demonstrated that OLA1 is at least an upstream suppressor of the expression of p21.

OLA1 regulates the expression of p53 and p21 via different mechanisms.

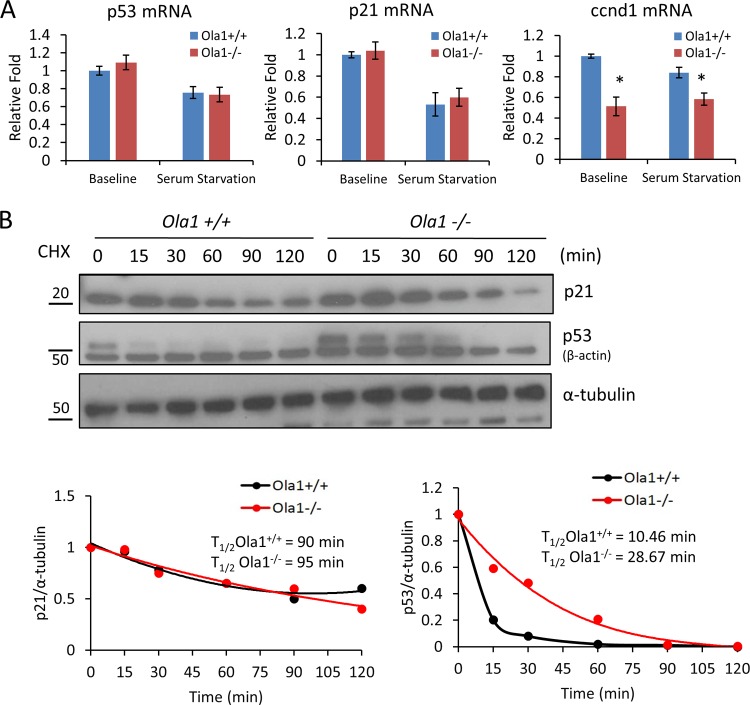

To determine the mechanisms by which OLA1 regulates the protein levels of p53 and p21, we first measured the levels of the mRNAs encoding p53 and p21 in primary MEFs (E12.5) using qRT-PCR. We found no significant difference in these mRNAs between the Ola1+/+ and Ola1−/− cells under either regular culture or overnight serum starvation conditions (Fig. 7A). Therefore, the observed baseline elevation of p53 protein levels and the serum starvation-induced accumulation of p53 and p21 could not be explained by activation at the transcriptional level. In contrast, ccnd1 mRNA levels were clearly decreased, which is consistent with the changes observed in its encoding protein (cyclin D1) (Fig. 5A). Next, we measured the level of protein degradation of p53 and p21 following treatment with cycloheximide. Interestingly, the half-life of p53 in the Ola1−/− MEFs (29 min) was significantly increased compared to the half-life in the Ola1+/+ cells (10 min), whereas the half-life of p21 remained relatively unchanged (95 min versus 90 min) (Fig. 7B).

FIG 7.

Effects of Ola1 knockout on p53 and p21 mRNA abundance and protein stability. (A) qRT-PCR analysis of p53, p21, and ccnd1 mRNAs in Ola1+/+ and Ola1−/− MEFs. The cells were cultured in full medium (baseline) or serum starved overnight before RNA isolation. Relative mRNA levels are presented as a fold change relative to the Ola1+/+ baseline control. Data are presented as the means ± SDs from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05. (B) Protein degradation of p53 and p21 in Ola1+/+ and Ola1−/− MEFs. MEFs were treated with cycloheximide (CHX) for the indicated times and then analyzed using immunoblotting with p53 or p21 antibodies (top). α-Tubulin was used as the internal control. The percentage of protein that remained was plotted as a function of time, and the resulting decay curve was fitted and calculated to determine the half-life (bottom). Data are representative of those from three independent experiments.

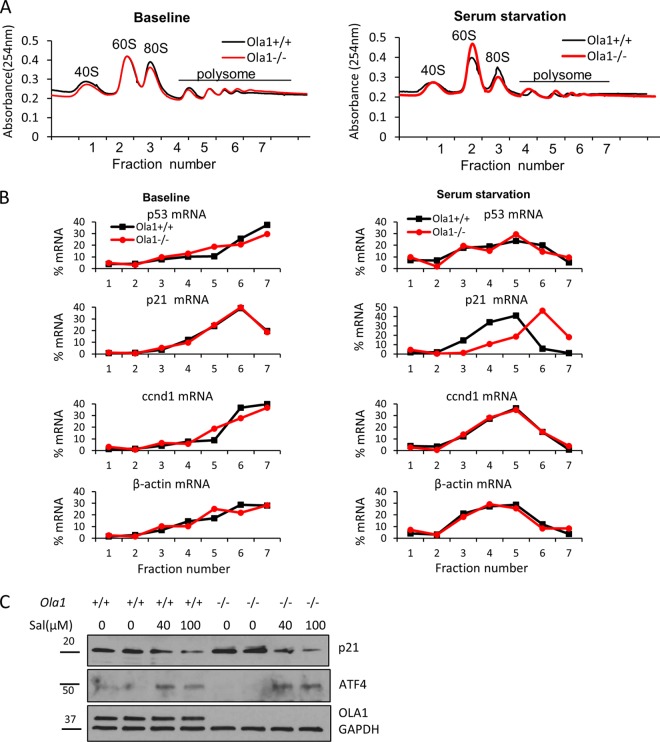

Because OLA1 was recently characterized as an eIF2-interating protein that is involved in translational control (6), we used polysome profiling to examine mRNA translation in Ola1 knockout MEFs. No significant differences were observed in global mRNA translation, as judged by comparing the profiles of polysome gradient fractions, between the Ola1+/+ and Ola1−/− MEFs under either basal or serum starvation conditions (Fig. 8A). Overnight serum starvation caused the loss of heavy polysomes in both cell types (Fig. 8A). We then used qRT-PCR to determine the levels of individual mRNAs, including p53, p21, ccnd1, and β-actin, in the fractions. Translational efficiency was estimated by calculating the proportion of the mRNA that was affiliated with heavy polysomes. When we cultured the cells in full medium, none of the tested mRNAs displayed differences in translational efficiency between the Ola1+/+ and Ola1−/− cells. However, following serum starvation, p21 mRNA showed an increased association with heavy polysomes in Ola1−/− but not Ola1+/+ MEFs, indicating that p21mRNA was more actively translated in the former cells than in the latter (Fig. 8B). All other mRNA species analyzed in the two cell sources were found to be similarly “left-shifted” (from heavy to light polysomes) in the profiles. These data suggest that at the absence of Ola1 p21 mRNA is selectively translated under serum starvation conditions, which mimic growth factor and nutrient insufficiency. Together, these three analyses lead us to conclude that knockout of Ola1 promotes the mRNA translation of p21 and enhances the protein stability of p53, which results in their accumulation. Finally, we tested if the overtranslation of p21 mRNA is associated with an increased abundance of eIF2 ternary complex, as in the case of Ola1 KD cancer cells (6). Ola1−/− MEFs under serum starvation were treated with salubrinal, an eIF2α dephosphorylation complex inhibitor that causes eIF2α phosphorylation and expression of ATF4, a surrogate marker for depletion of the ternary complex (16). The salubrinal treatment was able to totally block the accumulation of p21 protein (Fig. 8C).

FIG 8.

Translational regulation of cell cycle regulators by OLA1. (A) Polysome profiling of Ola1+/+ and Ola1−/− MEFs under baseline and overnight serum starvation conditions. For each profile, 7 fractions of gradient samples were collected. Free ribosomal subunits (40S and 60S), monosomes (80S), and polysomes are indicated. (B) Percentage distributions of individual mRNAs in the polysome profiles. Total RNAs were isolated from each fraction, and the levels of p53, p21, ccnd1, and β-actin mRNAs were measured using qRT-PCR. (C) Prevention of p21 protein accumulation by the eIF2-selective inhibitor salubrinal. Ola1+/+ and Ola1−/− MEFs were serum deprived overnight and subsequently treated or not with salubrinal (Sal) for 6 h. Immunoblotting was used to evaluate the levels of p21 and ATF4, with GAPDH used as the loading control.

Knockout of p21 partially rescues Ola1-null embryos' growth defects.

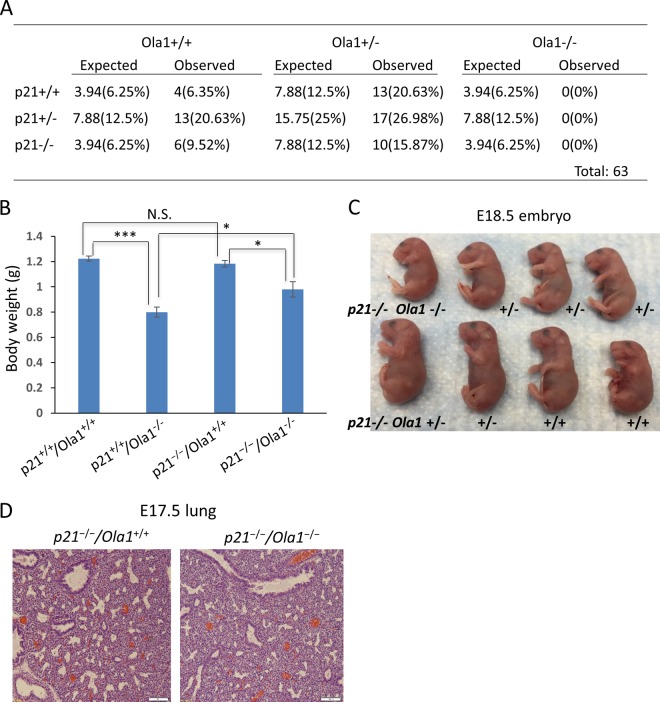

To verify if p21 plays an essential role in contributing to the phenotypes observed in our Ola1−/− mice, we generated p21−/−/Ola1−/− mice. First, we found no viable double-knockout mice among the offspring of the double heterozygous (Ola1+/−/p21+/−) parents (Fig. 9A). Next, we compared body weights of E18.5 fetuses with the following four genotypes: p21+/+/Ola1+/+ (WT), p21+/+/Ola1−/− (Ola1 single KO), p21−/−/Ola1+/+ (p21 single KO), and p21−/−/Ola1−/− (DKO). As shown in Fig. 9B, p21 single-KO fetuses had a mean body weight similar to that of the WT mice. Both Ola1 single-KO and DKO fetuses showed decreased body weights compared to those of their WT and p21 single-KO littermates, respectively. However, the extent of body weight reduction between the DKO mice and the p21 single-KO mice (17.1%) is much lower than the reduction between the Ola1 single-KO and WT mice (35%). This means that knockout of p21 significantly improved the growth of the Ola1-null mutants. This partial rescue of body size could be evidenced by visual inspection as well (compare Fig. 9C and 1F). Finally, by histological analyses, we found that knockout of p21 failed to improve Ola1−/− embryos' lung maturity (Fig. 9D). These data suggest that p21 inactivation can partially rescue Ola1-null embryos' growth retardation defects but not the perinatal death and developmental delay.

FIG 9.

Partial rescue of Ola1-null embryos' growth defects by p21 knockout. (A) Genotypic analysis of offspring from Ola1/p21 double heterozygous intercrosses. Listed are theoretical and observed numbers of mice with different genotypes, with the frequencies shown in parentheses. (B) Body weights of p21+/+/Ola1+/+, p21+/+/Ola1−/−, p21−/−/Ola1+/+, and p21−/−/Ola1−/− embryos at E18.5. Data are presented as means ± SEMs (n ≥ 4). N.S., no statistical significance. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001 (Student's t test). (C) Photograph of a litter of E18.5 fetuses from Ola1+/−/p21−/− parents. All animals are p21−/−, however, with three Ola1 genotypes as annotated. (D) Histological analysis of embryonic lung sections prepared from E17.5 fetuses (H&E staining). Scale bars: 100 μm.

DISCUSSION

It is estimated that approximately 30% of all single-gene knockout lines lead to embryonic or perinatal lethality (17–19). Our Ola1−/− mice represent an uncommon form of partial perinatal lethality that results from intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) coupled with developmental delays rather than a particular developmental error (Fig. 1E; Table 1). IUGR is defined as the failure of a fetus to reach its growth potential. In humans, it occurs in 3 to 7% of births and is associated with adverse consequences, including neonatal death and respiratory distress syndrome (20–22). Ola1−/− fetuses demonstrated proportionate growth restriction that resembled human symmetric IUGR. A growth retardation phenotype can result from decreased cell proliferation (23, 24), increased apoptosis (25, 26), or reduced cell size (27, 28). Our analyses of Ola1−/− embryos and primary MEFs failed to identify alterations in either apoptosis or cell size (Fig. 4E and F). Instead, the data pointed to a defect in cell proliferation due to a delay in cell cycle progression (Fig. 4B). The mutant embryos undergo fewer proliferation cycles and are therefore smaller than their non-null littermates of the same gestational age.

By examining gross morphology (≥E7.5) and histological sections (from E13.5 to P0), we determined that Ola1−/− embryos trailed behind in their gestation stage by 1 day starting on E8.5 (Fig. 1E and 2A). To our knowledge, this is the first documented case of an early-onset developmental delay that does not necessarily lead to embryonic lethality. In contrast, Bloom's syndrome gene (Blm)−/− mice, for example, show signs of developmental delay on E9.5 and die by E13.5 (26). In many other cases, developmental delay is combined with developmental defects in the heart, hematopoietic system, or multiple organs, and all of the mutants die at prenatal stages (19, 29, 30). We reasoned that our Ola1−/− mice survived to perinatal stages because they displayed a moderate delay (of ∼1 day) that was not associated with an adverse developmental defect, except for lung immaturity. Because the lungs are the last fetal organ system to mature, it is very common to find lung immaturity in fetuses that display global development delays. Indeed, at late gestational stages, the Ola1−/− fetuses displayed lungs with poor terminal sacculation, thicker alveolar septae, and defective type II pneumocytes (Fig. 2A), resembling the characteristics observed in the lungs of SGA babies. By chance, a small number of the mutants developed relatively more mature lungs, allowing them to survive birth and live to adulthood (Table 1).

In mammalian cells, the G1-to-S phase transition requires the expression of the G1 cyclins D and E and the formation and activation of the cyclin D-Cdk4/6 and cyclin E-Cdk2 complexes, which phosphorylate (and inactivate) Rb to release E2F, allowing E2F-mediated transcriptional activity, which drives entry into S-phase (24, 31). G2-to-M transition requires the activation of the cyclin B-Cdk1 complex by the CDC25-mediated dephosphorylation of CDK1 (32). The G1/S and G2/M transitions are also negatively regulated by cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CKIs), such as p21, and by p53, which is known to be the transcriptional activator of p21 (33). Ola1−/− MEFs displayed both G1/S and G2/M transition retardation associated with deficiencies in cyclins D1 and E1 (but not cyclin B1) and more importantly, the accumulation of the upstream cell cycle inhibitors, p53 and p21 (Fig. 4B and 5A and B). Our subsequent studies have revealed that the accumulation of p53 results from increased protein stability, and that of p21 is mainly due to enhanced mRNA translation (Fig. 7 and 8). The exact mechanism by which OLA1 knockout lengthens the half-life of p53 needs to be further explored. OLA1 knockout may alter cellular stress response pathways, which, in turn, stabilize p53 as a common outcome (34).

On the other hand, we present details that may explain the translational upregulation of p21 in Ola1 knockout cells. We show that in Ola1−/− MEFs, while no global changes in mRNA translation were identified, p21 mRNAs are more actively translated than the mRNAs for p53, cyclin D1, and the β-actin housekeeping gene (Fig. 8A and B). According to our recent studies, OLA1 is an eIF2-interacting protein that suppresses the de novo formation of the ternary complex (6). Indeed, we observed a decrease in the baseline expression of ATF4 in knockout MEFs without a concurrent change in eIF2α phosphorylation (Fig. 5A and 8C). Lower ATF4 expression is indicative of more abundant ternary complexes (35, 36). Based on the finding that an eIF2-selective inhibitor could prevent p21 total protein accumulation in serum-starved Ola1-null cells (Fig. 8C), we postulate that the overtranslation of p21 is due to overactivation of eIF2 at the absence of its suppressor OLA1 (6). However, we are not certain how many other mRNA species are also affected by this mechanism. Quantitation of translation in vivo by ribosome profiling or polysome profiling followed by transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) may help to screen for more OLA1-targeted genes (37, 38). Further studies are needed to identify common cis and trans elements that may contribute to the differential translation of these mRNAs.

OLA1 is likely a multifunctional molecular switch-like GTPase. Besides its role in mRNA translation revealed by our group (6) and others (39), OLA1 has been implicated in DNA damage response (8), oxidative response (9), cell adhesion (40), and heat shock (13). In one recent report, OLA1 has been shown to localize not only in cytoplasm but also in the centrosome and spindle poles. OLA1 is found to interact with BARD1, BRCA1, and γ-tubulin and works together with BRCA1 in regulation of the centrosome. Knockdown of OLA1 in breast cancer cells caused centrosome amplification, however, without apparent changes in cell cycle (41). Further in-depth studies of Ola1−/− MEFs, especially on the G2/M phases, would help determine if loss of OLA1 could result in delayed mitosis and/or centrosome abnormalities. Because the OLA1 gene has been identified as a DNA damage-regulated gene (8), and its binding partner BRCA1 is a major regulator of DNA repair, our Ola1-null mutant systems may serve as a tool to identify the role of OLA1 in DNA damage repair.

In a few previous studies, accumulation of p21 and/or p53 has been suggested to cause growth failure during early embryonic development. For example, p21 was found increased in Brca1 knockout embryos (42), and p53 was observed to accumulate in embryos lacking Tsg101 (43). However, in the present study, p53 accumulation could not be confirmed in Ola1-null embryos, nor could it be reversed by OLA1 reconstitution in vitro (Fig. 6C). We therefore concentrated on testing if the increase of p21 is causative to the OLA1 knockout phenotypes. Knockout of p21 showed a partial but significant rescue of the growth retardation defects of the Ola1−/− embryos, suggesting that p21 may mediate, at least in part, the cell proliferation-related phenotype (Fig. 9). However, because the double-knockout mice continued to have lung immaturity and perinatal lethality, the development delay-related phenotypes are apparently independent of accumulation of p21. Rather, we should further explore possible contributing factors among other OLA1-targeted genes or among other pathways within or beyond protein synthesis. In summary, our studies have established novel essential functions for OLA1 during cell proliferation, embryonic development, and adult animal growth. OLA1 facilitates the cell cycle progression to maintain a high rate of cell proliferation under certain conditions, such as embryonic development. Our OLA1 knockout mice and OLA1 knockout-derived cell lines may provide unique models which can be used to increase our understanding of human health conditions, including developmental delays and IUGR.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Roberto Barrios for his advice during the histology studies. We thank Jiawei Zhang, Huarong Chen, and Prince Jeyabal for their assistance during some of the experiments. We also thank Aaron Shi for editing the manuscript.

This study was supported by an NIH grant (R01CA155069) (to Z.-Z. Shi) and a HMRI Cornerstone Award (to Z.-Z. Shi).

REFERENCES

- 1.Leipe DD, Wolf YI, Koonin EV, Aravind L. 2002. Classification and evolution of P-loop GTPases and related ATPases. J Mol Biol 317:41–72. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verstraeten N, Fauvart M, Versées W, Michiels J. 2011. The universally conserved prokaryotic GTPases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 75:507–542. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00009-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teplyakov A, Obmolova G, Chu SY, Toedt J, Eisenstein E, Howard AJ, Gilliland GL. 2003. Crystal structure of the YchF protein reveals binding sites for GTP and nucleic acid. J Bacteriol 185:4031–4037. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.14.4031-4037.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gradia DF, Rau K, Umaki ACS, de Souza FSP, Probst CM, Correa A, Holetz FB, Avila AR, Krieger MA, Goldenberg S, Fragoso SP. 2009. Characterization of a novel Obg-like ATPase in the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi. Int J Parasitol 39:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koller-Eichhorn R, Marquardt T, Gail R, Wittinghofer A, Kostrewa D, Kutay U, Kambach C. 2007. Human OLA1 defines an ATPase subfamily in the Obg family of GTP-binding proteins. J Biol Chem 282:19928–19937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700541200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen H, Song R, Wang G, Ding Z, Yang C, Zhang J, Zeng Z, Rubio V, Wang L, Zu N, Weiskoff AM, Minze LJ, Jeyabal PVS, Mansour OC, Bai L, Merrick WC, Zheng S, Shi Z-Z. 2015. OLA1 regulates protein synthesis and integrated stress response by inhibiting eIF2 ternary complex formation. Sci Rep 5:13241. doi: 10.1038/srep13241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qian W, Ma D, Xiao C, Wang Z, Zhang J. 2012. The genomic landscape and evolutionary resolution of antagonistic pleiotropy in yeast. Cell Rep 2:1399–1410. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun H, Luo X, Montalbano J, Jin W, Shi J, Sheikh MS, Huang Y. 2010. DOC45, a novel DNA damage-regulated nucleocytoplasmic ATPase that is overexpressed in multiple human malignancies. Mol Cancer Res 8:57–66. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J, Rubio V, Lieberman MW, Shi Z-Z. 2009. OLA1, an Obg-like ATPase, suppresses antioxidant response via nontranscriptional mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:15356–15361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907213106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zambrowicz BP, Friedrich GA, Buxton EC, Lilleberg SL, Person C, Sands AT. 1998. Disruption and sequence identification of 2,000 genes in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nature 392:608–611. doi: 10.1038/33423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farley FW, Soriano P, Steffen LS, Dymecki SM. 2000. Widespread recombinase expression using FLPeR (flipper) mice. Genesis 28:106–110. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lakso M, Pichel JG, Gorman JR, Sauer B, Okamoto Y, Lee E, Alt FW, Westphal H. 1996. Efficient in vivo manipulation of mouse genomic sequences at the zygote stage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93:5860–5865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mao R-F, Rubio V, Chen H, Bai L, Mansour O, Shi Z-Z. 2013. OLA1 protects cells in heat shock by stabilizing HSP70. Cell Death Dis 4:e491. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramunas J, Yakubov E, Brady JJ, Corbel SY, Holbrook C, Brandt M, Stein J, Santiago JG, Cooke JP, Blau HM. 2015. Transient delivery of modified mRNA encoding TERT rapidly extends telomeres in human cells. FASEB J 29:1930–1939. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-259531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamura K, Sakaue H, Nishizawa A, Matsuki Y, Gomi H, Watanabe E, Hiramatsua R, Tamamori-Adachi M, Kitajima S, Noda T, Ogawa W, Kasuga M. 2008. PDK1 regulates cell proliferation and cell cycle progression through control of cyclin D1 and p27Kip1 expression. J Biol Chem 283:17702–17711. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802589200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyce M, Bryant KF, Jousse C, Long K, Harding HP, Scheuner D, Kaufman RJ, Ma D, Coen DM, Ron D, Yuan J. 2005. A selective inhibitor of eIF2alpha dephosphorylation protects cells from ER stress. Science 307:935–939. doi: 10.1126/science.1101902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong MD, Maezawa Y, Lerch JP, Henkelman RM. 2014. Automated pipeline for anatomical phenotyping of mouse embryos using micro-CT. Development 141:2533–2541. doi: 10.1242/dev.107722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turgeon B, Meloche S. 2009. Interpreting neonatal lethal phenotypes in mouse mutants: insights into gene function and human diseases. Physiol Rev 89:1–26. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00040.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ward JM, Elmore SA, Foley JF. 2012. Pathology methods for the evaluation of embryonic and perinatal developmental defects and lethality in genetically engineered mice. Vet Pathol 49:71–84. doi: 10.1177/0300985811429811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romo A, Carceller R, Tobajas J. 2009. Intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR): epidemiology and etiology. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev 6(Suppl 3):S332–S336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernstein IM, Horbar JD, Badger GJ, Ohlsson A, Golan A. 2000. Morbidity and mortality among very-low-birth-weight neonates with intrauterine growth restriction. The Vermont Oxford Network. Am J Obstet Gynecol 182:198–206. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(00)70513-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yung H, Calabrese S, Hynx D, Hemmings BA, Cetin I, Charnock-Jones DS, Burton GJ. 2008. Evidence of placental translation inhibition and endoplasmic reticulum stress in the etiology of human intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Pathol 173:451–462. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.071193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klammt J, Pfäffle R, Werner H, Kiess W. 2008. IGF signaling defects as causes of growth failure and IUGR. Trends Endocrinol Metab 19:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ciemerych MA, Sicinski P. 2005. Cell cycle in mouse development. Oncogene 24:2877–2898. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen WS, Xu PZ, Gottlob K, Chen ML, Sokol K, Shiyanova T, Roninson I, Weng W, Suzuki R, Tobe K, Kadowaki T, Hay N. 2001. Growth retardation and increased apoptosis in mice with homozygous disruption of the Akt1 gene. Genes Dev 15:2203–2208. doi: 10.1101/gad.913901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chester N, Kuo F, Kozak C. 1998. Stage-specific apoptosis, developmental delay, and embryonic lethality in mice homozygous for a targeted disruption in the murine Bloom's syndrome gene. Genes Dev 12:3382–3393. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.21.3382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawlor MA, Mora A, Ashby PR, Williams MR, Murray-Tait V, Malone L, Prescott AR, Lucocq JM, Alessi DR. 2002. Essential role of PDK1 in regulating cell size and development in mice. EMBO J 21:3728–3738. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruvinsky I, Sharon N, Lerer T, Cohen H, Stolovich-Rain M, Nir T, Dor Y, Zisman P, Meyuhas O. 2005. Ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation is a determinant of cell size and glucose homeostasis. Genes Dev 19:2199–2211. doi: 10.1101/gad.351605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akhter S, Lam YC, Chang S, Legerski RJ. 2010. The telomeric protein SNM1B/Apollo is required for normal cell proliferation and embryonic development. Aging Cell 9:1047–1056. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00631.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tominaga K, Kirtane B. 2005. MRG15 regulates embryonic development and cell proliferation. Mol Cell Biol 25:2924–2937. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.8.2924-2937.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joklik WK. 1999. Collaborative role of E2F transcriptional activity and G 1 cyclin-dependent kinase activity in the induction of S phase. Biochemistry 96:6626–6631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seki A, Coppinger J, Jang C. 2008. Bora and Aurora A cooperatively activate Plk1 and control the entry into mitosis. Science 320:1655–1658. doi: 10.1126/science.1157425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jung Y-S, Qian Y, Chen X. 2010. Examination of the expanding pathways for the regulation of p21 expression and activity. Cell Signal 22:1003–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ashcroft M, Taya Y, Vousden KH. 2000. Stress signals utilize multiple pathways to stabilize p53. Mol Cell Biol 20:3224–3233. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.9.3224-3233.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu PD, Harding HP, Ron D. 2004. Translation reinitiation at alternative open reading frames regulates gene expression in an integrated stress response. J Cell Biol 167:27–33. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200408003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barbosa C, Peixeiro I, Romão L. 2013. Gene expression regulation by upstream open reading frames and human disease. PLoS Genet 9:e1003529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ingolia NT. 2014. Ribosome profiling: new views of translation, from single codons to genome scale. Nat Rev Genet 15:205–213. doi: 10.1038/nrg3645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spangenberg L, Shigunov P, Abud APR, Cofre AR, Stimamiglio MA, Kuligovski C, Zych J, Schittini AV, Costa ADT, Rebelatto CK, Brofman PRS, Goldenberg S, Correa A, Naya H, Dallagiovanna B. 2013. Polysome profiling shows extensive posttranscriptional regulation during human adipocyte stem cell differentiation into adipocytes. Stem Cell Res 11:902–912. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Samanfar B, Tan LH, Shostak K, Chalabian F, Wu Z, Alamgir M, Sunba N, Burnside D, Omidi K, Hooshyar M, Galvá I, Rquez M, Jessulat M, Smith ML, Babu M, Azizi A, Golshani A. 2014. A global investigation of gene deletion strains that affect premature stop codon bypass in yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol BioSyst 10:916–924. doi: 10.1039/c3mb70501c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jeyabal PVS, Rubio V, Chen H, Zhang J, Shi ZZ. 2014. Regulation of cell-matrix adhesion by OLA1, the Obg-like ATPase 1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 444:568–574. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.01.099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsuzawa A, Kanno S ichiro, Nakayama M, Mochiduki H, Wei L, Shimaoka T, Furukawa Y, Kato K, Shibata S, Yasui A, Ishioka C, Chiba N. 2014. The BRCA1/BARD1-interacting protein OLA1 functions in centrosome regulation. Mol Cell 53:101–114. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hakem R, de la Pompa JL, Sirard C, Mo R, Woo M, Hakem A, Wakeham A, Potter J, Reitmair A, Billia F, Firpo E, Hui CC, Roberts J, Rossant J, Mak TW. 1996. The tumor suppressor gene Brca1 is required for embryonic cellular proliferation in the mouse. Cell 85:1009–1023. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81302-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ruland J, Sirard C, Elia A, MacPherson D, Wakeham A, Li L, de la Pompa JL, Cohen SN, Mak TW. 2001. p53 accumulation, defective cell proliferation, and early embryonic lethality in mice lacking Tsg101. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:1859–1864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]