Abstract

Vancomycin remains the mainstay treatment for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bloodstream infections (BSIs) despite increased treatment failures. Daptomycin has been shown to improve clinical outcomes in patients with BSIs caused by MRSA isolates with vancomycin MICs of >1 mg/liter, but these studies relied on automated testing systems. We evaluated the outcomes of BSIs caused by MRSA isolates for which vancomycin MICs were determined by standard broth microdilution (BMD). A retrospective, matched cohort of patients with MRSA BSIs treated with vancomycin or daptomycin from January 2010 to March 2015 was completed. Patients were matched using propensity-adjusted logistic regression, which included age, Pitt bacteremia score, primary BSI source, and hospital of care. The primary endpoint was clinical failure, which was a composite endpoint of the following metrics: 30-day mortality, bacteremia with a duration of ≥7 days, or a change in anti-MRSA therapy due to persistent or worsening signs or symptoms. Secondary endpoints included MRSA-attributable mortality and the number of days of MRSA bacteremia. Independent predictors of failure were determined through conditional backwards-stepwise logistic regression with vancomycin BMD MIC forced into the model. A total of 262 patients were matched. Clinical failure was significantly higher in the vancomycin cohort than in the daptomycin cohort (45.0% versus 29.0%; P = 0.007). All-cause 30-day mortality was significantly higher in the vancomycin cohort (15.3% versus 6.1%; P = 0.024). These outcomes remained significant when stratified by vancomycin BMD MIC. There was no significant difference in the length of MRSA bacteremia. Variables independently associated with treatment failure included vancomycin therapy (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 2.16, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.24 to 3.76), intensive care unit admission (aOR = 2.46, 95% CI = 1.34 to 4.54), and infective endocarditis as the primary source (aOR = 2.33, 95% CI = 1.16 to 4.68). Treatment of MRSA BSIs with daptomycin was associated with reduced clinical failure and 30-day mortality; these findings were independent of vancomycin BMD MIC.

INTRODUCTION

Infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) continue to be a major public health threat (1). Additionally, bloodstream infections (BSIs) caused by MRSA are associated with significant morbidity and mortality (2). Timely administration of appropriate antibiotic therapy has been demonstrated to be of critical importance in the treatment of MRSA BSIs (3). Vancomycin remains the mainstay of therapy for MRSA BSIs and is currently recommended in the MRSA treatment guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) (4). Numerous reports have associated vancomycin treatment failure with elevated MICs still within the susceptible range, in particular, with a vancomycin MIC of >1 mg/liter; however, this remains an area of clinical debate (5–10).

Daptomycin has been shown to improve clinical outcomes in MRSA BSIs compared to those achieved with vancomycin. In a 2005 prospective, randomized trial of daptomycin at 6 mg/kg compared to standard care for S. aureus bacteremia and/or infective endocarditis, daptomycin was found to be noninferior (2.4%; 95% Cl, −10.2% to 15.1%) with respect to clinical success (11). In a subgroup analysis of patients with MRSA bacteremia and/or infective endocarditis, differences in clinical success also favored daptomycin, with success in complicated bacteremia reported to be 45% versus 27% in the standard care arm (12). Two retrospective matched cohort studies have directly compared vancomycin to daptomycin for the treatment of MRSA BSIs caused by isolates with elevated vancomycin MICs. Moore et al. found that vancomycin-treated patients experienced numerically higher clinical failure rates (31% versus 17%; P = 0.084) and significantly higher 60-day all-cause mortality rates than daptomycin-treated patients (20% versus 9%; P = 0.049) (13). Murray et al. reported significantly higher rates of clinical failure (48.2% versus 20.0%; P < 0.001) and 30-day all-cause mortality (12.9% versus 3.5%; P = 0.047) among vancomycin-treated patients compared to daptomycin-treated patients (14). In a quasiexperimental study by Kullar et al., the implementation of an early daptomycin treatment pathway for MRSA BSIs caused by isolates exhibiting a vancomycin MIC of >1 mg/liter demonstrated improved rates of clinical success (75.0% versus 41.4%; P < 0.001) (15). Most recently, Weston et al. reported higher clinical failure rates among vancomycin-treated patients than daptomycin-treated patients (51.0% versus 34.0%; P = 0.048) and noted that the outcomes did not change in those treated with daptomycin, regardless of renal function (16). Currently, there are few studies that have directly addressed the impact of elevated vancomycin MICs on patient outcomes when patients are treated with daptomycin for MRSA BSIs and the current literature has failed to demonstrate the same association between outcomes and elevated MIC as with vancomycin-treated patients, making daptomycin an ideal treatment alternative (17).

Many of the studies comparing the clinical efficacy of vancomycin to daptomycin for MRSA BSIs have relied on automated testing systems (ATSs) to determine the vancomycin MIC. Recently, the clinical utility of determination of vancomycin MICs by ATSs has come into question (18–20). When three commercial MIC ATSs (the MicroScan, Vitek2, and BD Phoenix systems) were compared to the current Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) standard of broth microdilution (BMD), the results were less than assuring. Overall, agreement (±0 log2 dilution) was low, ranging from 34.3% to 66.2% (21). Of importance, it was found that the MicroScan system reported the vancomycin MIC to be higher by 1 log dilution for over 60% of tested isolates, while the BD Phoenix and Vitek2 systems reported the vancomycin MIC to be 1 log dilution lower for 26.7% and 32.3% of tested isolates, respectively. Vancomycin MICs of >1 mg/liter have been associated with worse patient outcomes; however, the lack of precision of ATSs calls into question the true clinical validity of this assertion. The current study used vancomycin MICs reported by BMD in order to determine if improved clinical outcomes with daptomycin were truly dependent on vancomycin MIC being >1 mg/liter.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and population.

This was a retrospective propensity-matched cohort study of patients treated with vancomycin or daptomycin for MRSA BSIs conducted at the Detroit Medical Center (DMC), Henry Ford Hospital (HFH), and the University of Michigan Health System (UMHS) from January 2010 to March 2015. Patients were included if the culture of at least one blood sample was positive for MRSA and they received at least 72 h of MRSA-directed therapy. Only data from the index visit during the study period were included in the analysis. Patients were excluded from analysis if they were less than 18 years of age, the source of the BSI was determined to be pneumonia, they were receiving renal replacement therapy at the start of MRSA therapy, the S. aureus isolated was resistant or nonsusceptible to one or more of the study antibiotics, and/or the patient had a polymicrobial BSI. Patients were defined to be daptomycin treated if daptomycin was given within 72 h of the start of MRSA-directed therapy. The institutional review boards at WSU, HFH, and UMHS approved this study. A waiver of informed consent was obtained at all sites. Study data were collected and managed using research electronic data capture (REDCap; Vanderbilt University), hosted at Wayne State University (22).

Clinical data, outcomes assessments, and definitions.

Data were collected from the patients' electronic medical records (eMR) postdischarge. The information collected included demographic information, clinical characteristics, course of therapy, and clinical outcomes. The Charlson comorbidity score was obtained for all patients, as was the Pitt bacteremia score, within 48 h of BSI onset. Information on the length of stay (LOS; in days), intensive care unit (ICU) admission, length of stay in the ICU (ICU LOS; in days), and the length of bacteremia (in days) was also collected. The duration of bacteremia was defined as the number of calendar days from the first positive culture for MRSA. An MRSA BSI was considered complicated if the length of bacteremia was ≥5 days; the patient developed a metastatic focus of infection, including infective endocarditis; or the infection involving hardware was not removed within 4 days of BSI onset (40). Persistent bacteremia was defined as an MRSA BSI present for ≥7 consecutive days (4). The eMR was reviewed to determine the primary source of BSI, as designated by the treating physician: skin/soft tissue, bone/joint, infective endocarditis, intravenous (i.v.) catheter, or other/unknown. For patients with multiple possible sources of MRSA BSI, a dominant focus was determined according to a previously published ranking: endocarditis > bone/joint > other > skin/soft tissue > i.v. catheter (23).

The primary outcome was clinical failure, a composite endpoint which included 30-day all-cause mortality, bacteremia persistent for ≥7 days, or a change in antibiotic therapy secondary to persistent signs and symptoms of infection. Thirty-day all-cause mortality was defined as mortality from any cause within 30 days of collection of the first blood sample positive by culture. Secondary outcomes included inpatient all-cause mortality, MRSA-attributable mortality, length of bacteremia, LOS, LOS after BSI onset, ICU LOS and ICU LOS after BSI onset, and 60-day MRSA BSI-related readmission. Clinical outcomes were also determined by an adjudication committee consisting of two infectious diseases physicians (D.P.L. and K.S.K.) blinded to treatment. The definition of clinical failure used by the adjudication committee was a composite of the following metrics: 30-day MRSA-related mortality, as determined by D.P.L. or K.S.K.; new or worsening signs/symptoms of infection during the hospital stay requiring a change in antibiotic therapy; or blood cultures persistently positive for ≥7 days.

The safety assessment included documentation of all adverse events occurring while the patient was on daptomycin or vancomycin. Adverse events were recorded as follows: not related, possibly related, or related to drug therapy on the basis of documentation within the eMR. Nephrotoxicity was defined as a minimum of two consecutive documented increases in the serum creatinine concentration (an increase of 0.5 mg/dl or ≥50% from the baseline concentration) in the absence of an alternative explanation (24). Elevations in creatine phosphokinase (CPK) concentrations were defined as unexplained signs and symptoms of myopathy in conjunction with a CPK concentration of >1,000 IU/liter or an asymptomatic condition with a CPK concentration of >2,000 IU/liter (25).

Microbiological and molecular assessment.

Microbiological testing of the first available blood isolate for each patient included was performed. The susceptibility of each isolate to vancomycin and daptomycin was determined at the hospital of care by the use of ATSs; DMC utilized the MicroScan system, and HFH and UMHS utilized the Vitek2 system. Susceptibilities to vancomycin and daptomycin were also determined by BMD in duplicate according to CLSI guidelines at the Anti-Infective Research Laboratory (ARL; Detroit, MI) (26). According to the ARL protocol, if there was a 1-log-dilution discrepancy, the higher MIC was documented. If there was a >1-log-dilution discrepancy, BMD was repeated. The staphylococcal cassette mec (SCCmec), USA, and accessory gene regulator (agr) types as well as the presence of the Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) toxin gene were determined through multiplex PCR as described previously; agr dysfunction was determined phenotypically by a delta-hemolysin assay (27–29).

Statistical analysis.

If a difference in clinical failure of 20% favoring the daptomycin-treated arm, a statistical power of 80%, and a two-sided α value of 0.05 were assumed, a minimum of 100 patients was needed in each treatment arm. Patients were matched using propensity-adjusted logistic regression, which included age, Pitt bacteremia score, primary BSI source, and hospital of care. A caliper length of 0.2 without replacement was used in the propensity match. Descriptive statistics were reported as percentages, means ± standard deviations, or medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs), as appropriate. Dichotomous variables were compared using Pearson's chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. Continuous variables were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test or Student's t test, as appropriate. Variables with a P value of <0.05 were considered significant. Although the cohorts were matched using propensity matching as described above, comparisons of baseline demographics and clinical characteristics between patients treated with vancomycin and patients treated with daptomycin were made to determine if the groups were, in fact, matched appropriately. Comparisons of patients that were determined to have experienced clinical failure and those that did not were then made. Multivariable conditional backwards-stepwise logistic regression was performed to determine the variables independently associated with clinical failure. All variables associated with the outcome of interest upon univariate analysis with a P value of <0.1 or determined to be clinically relevant a priori, such as the vancomycin MIC determined by BMD, were included in the regression model. A P value of 0.05 was used as the cutoff for the variable to remain in the model. The model fit was determined by the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, with a P value of >0.05 being considered adequate. The Kaplan-Meier estimator was used to determine 30-day survival between patients treated with vancomycin and those treated with daptomycin. The log rank statistic was used to compare the two survival curves. Statistical analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS program (version 22.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

From January 2010 to March 2015, a total of 848 patients were screened for inclusion, and 563 were excluded for the following reasons: a repeat MRSA BSI (n = 39), blood cultures cleared before initiation of vancomycin or daptomycin (n = 23), receipt of renal replacement therapy at the start of therapy (n = 134), treatment with daptomycin or vancomycin for <72 h (n = 135), time to switch to daptomycin > 72 h (n = 38), <18 years of age (n = 4), pregnant (n = 4), a polymicrobial BSI (n = 38), pneumonia as the primary MRSA BSI source (n = 75), the vancomycin MIC was >2 mg/liter by testing with an ATS (n = 1), the isolate was daptomycin nonsusceptible (n = 0), and no isolate was available for BMD MIC testing (n = 72). A total of 285 patients met the inclusion criteria, and a total of 262 patients were matched (data not shown). Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics were balanced between the two cohorts (Table 1). The median Pitt bacteremia score was low at 3 (interquartile range [IQR], 2 to 3), and the patient median age was 57.0 years (IQR, 46.0 to 70.0 years). The primary source of MRSA BSI was balanced between the two groups, with no significant differences; however, patients receiving daptomycin were numerically more likely to have bone/joint as the primary source of MRSA BSI. The most common primary sources of MRSA BSI were bone/joint (n = 65, 24.8%) and skin/soft tissue (n = 63, 24.0%).

TABLE 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristicsa

| Characteristic | Result for patients receiving: |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VAN (n = 131) | DAP (n = 131) | ||

| Median (IQR) age (yr) | 57.0 (46.0–70.0) | 56.0 (43.0–61.0) | 0.095 |

| Median (IQR) Pitt bacteremia score | 3 (2–3) | 3 (2–3) | 0.933 |

| Median (IQR) baseline CRCL (ml/min) | 61.6 (37.9–84.0) | 60.4 (40.3–82.5) | 0.885 |

| No. (%) of patients with: | |||

| AKI on admission | 45 (34.4) | 44 (33.6) | 0.896 |

| History of DM | 43 (32.8) | 50 (38.2) | 0.366 |

| HIV/AIDS | 9 (6.9) | 10 (7.6) | 0.812 |

| CHD | 22 (16.8) | 20 (15.3) | 0.736 |

| i.v. drug use | 34 (26.0) | 35 (26.7) | 0.888 |

| CKD (not HD) | 16 (12.2) | 24 (18.3) | 0.169 |

| Liver disease | 21 (16.0) | 30 (22.9) | 0.160 |

| Antibiotic use in past 30 days | 33 (25.2) | 27 (20.6) | 0.262 |

| Vancomycin use in past 30 days | 12 (9.2) | 7 (5.3) | 0.341 |

| Hospitalization in past year | 66 (50.4) | 65 (49.6) | 0.902 |

| Surgery in past 30 days | 5 (3.8) | 14 (10.7) | 0.032 |

| MRSA infection in past year | 7 (5.3) | 16 (12.2) | 0.049 |

| No. (%) of patients with the following primary site of infection: | 0.572 | ||

| Bone/joint | 27 (20.6) | 38 (29.0) | |

| Skin/soft tissue | 33 (25.2) | 30 (22.9) | |

| Deep abscess | 14 (10.7) | 14 (10.7) | |

| Infective endocarditis | 23 (17.6) | 25 (19.1) | |

| i.v. catheter | 15 (11.5) | 10 (7.6) | |

| Other | 19 (14.5) | 14 (10.7) | |

AKI, acute kidney injury; DAP, daptomycin; DM, diabetes mellitus; CHD, congestive heart disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CRCL, creatinine clearance; HD, hemodialysis; IQR, interquartile range; VAN, vancomycin.

The clinical course and the interventions received were not significantly different between the two groups (Table 2). Lengths of stay, the numbers of ICU admissions, and ICU lengths of stay were all similar. The number of days of bacteremia was numerically higher in the daptomycin-treated patients (4.0 days [IQR, 2.0 to 6.5 days] days) than the vancomycin-treated patients (3.0 days [IQR, 2.0 to 6.0 days]); however, this difference was not statistically significant. When the data were adjusted for when the patients started a study antibiotic, the median number of days of bacteremia was the same for daptomycin- and vancomycin-treated patients (3.0 days [IQR, 1.0 to 6.0 days]). Patients in the daptomycin cohort were commonly started on vancomycin therapy before being switched to daptomycin (n = 106, 80.9%). Among the vancomycin-treated patients, the median initial steady-state trough level was 17.7 mg/liter (IQR, 13.2 to 22.0 mg/liter), and 72 (54.9%) had trough levels of ≥15 mg/liter. Among the daptomycin-treated patients, 68 (51.9%) received daptomycin doses of ≥8 mg/kg. Additionally, combination therapy was common in both groups (daptomycin group, 24.4%; vancomycin group, 20.6%; P = 0.6). The most common combinations used were ceftaroline (daptomycin group, 13.0%; vancomycin group, 10.7%; P = 0.802) and rifampin (daptomycin group, 6.9%; vancomycin group, 4.6%; P = 0.425). Infectious disease consults were more common in the daptomycin-treated patients (91.6% versus 75.6% for the vancomycin-treated patients; P = 0.001). Source control measures were not different between the two groups (32.8% for the daptomycin group versus 31.3% for the vancomycin group; P = 0.965). Among the patients with documented source control, the time to source control did not differ (3.0 days [IQR, 2.0 to 6.0 days] for the daptomycin group versus 2.0 days [IQR, 1.0 to 5.0 days] for the vancomycin group; P = 0.099).

TABLE 2.

Clinical course and interventionsa

| Characteristic | Result for patients receiving: |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VAN (n = 131) | DAP (n = 131) | ||

| Median (IQR) length of stayb (days) | 13.0 (9.0–19.5) | 14.0 (10.0–25.0) | 0.155 |

| No. (%) of patients with ICU admission | 96 (73.3) | 96 (73.3) | 1.000 |

| Median (IQR) length of ICU stayb (days) | 6.5 (3.0–15.3) | 8.0 (3.0–13.5) | 0.852 |

| No. (%) of patients with complicated bacteremia | 64 (48.9) | 65 (49.6) | 0.902 |

| Median (IQR) length of bacteremia (days) | 3.0 (2.0–6.0) | 4.0 (2.0–6.5) | 0.452 |

| No. (%) of patients with a secondary site of infection | 33 (25.2) | 36 (27.5) | 0.719 |

| No. (%) of patients with effective source control | 41 (31.3) | 43 (32.8) | 0.965 |

| No. (%) of patients with an infectious disease consult | 99 (75.6) | 120 (91.6) | 0.001 |

| Median (IQR) initial vancomycin trough concn (mg/liter) | 17.7 (13.2–22.0) | NT | |

| Median (IQR) dose DAP (mg/kg TBW) | 8.2 (6.4–10.0) | NT | |

| Median (IQR) time to DAP (h) | 48.4 (17.4–64.3) | NT | |

DAP, daptomycin; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; NT, not tested; TBW, total body weight; VAN, vancomycin.

Censored for inpatient mortality.

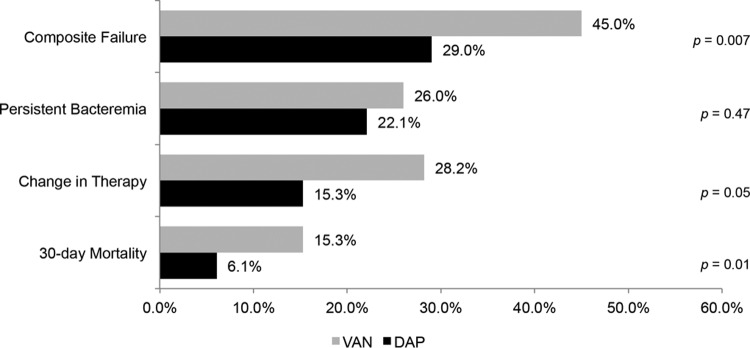

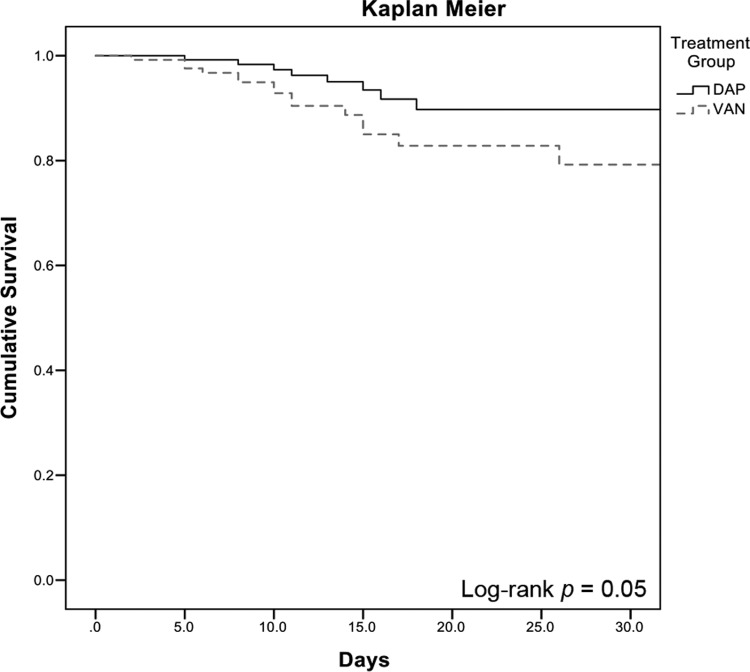

The rate of clinical failure was significantly higher in the vancomycin-treated patients than the daptomycin-treated patients (45.0% versus 29.0%; P = 0.007) (Figure 1). Additionally, the rate of clinical failure was significantly higher in the vancomycin-treated patients, as determined by the adjudication committee blinded to the treatment (59.6% versus 42.6%; P = 0.014). When the comparison of vancomycin-treated to daptomycin-treated patients with respect to the composite outcome of clinical failure was stratified by the vancomycin BMD MIC, the difference remained significant at an MIC of 0.5 mg/liter (54.5% versus 32.0%; P = 0.027). The difference in clinical outcomes was largely driven by the need to change the anti-MRSA therapy secondary to persistent or worsening signs and symptoms of infection (28.2% for vancomycin-treated patients versus 15.3% for daptomycin-treated patients; P = 0.05) and 30-day all-cause mortality (15.3% for vancomycin-treated patients versus 6.1% for daptomycin-treated patients; P = 0.01). MRSA-attributable mortality was also higher in the vancomycin-treated patients (8.4% versus 2.3%; P = 0.05). The rate of bacteremia persistent for ≥7 consecutive days was not different between the two treatment groups (26.0% for vancomycin-treated patients versus 22.1% for daptomycin-treated patients; P = 0.47). Upon univariate analysis, variables associated with clinical failure included vancomycin treatment group, ICU admission, bone/joint as the primary source of BSI, infective endocarditis as the primary source of BSI, complicated bacteremia, acute kidney injury, and a history of i.v. drug use (data not shown). Effective source control was protective against clinical failure. Complicated bacteremia was removed from the model because it was colinear with the definition of clinical failure. Vancomycin BMD MIC was forced into the model as specified a priori. The variables that remained significant in the final model were vancomycin treatment group (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 2.16, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.24 to 3.76), ICU admission (aOR = 2.46, 95% CI = 1.34 to 4.54), infective endocarditis as the primary source of MRSA BSI (aOR = 2.33, 95% CI = 1.16 to 4.68), and source control (aOR = 0.55, 95% CI = 0.30 to 1.02) (Table 3). As provided in Figure 2, the Kaplan-Meier estimate of 30-day mortality was not significant by the log rank test (P = 0.05).

FIG 1.

Clinical failure by treatment group. VAN, vancomycin; DAP, daptomycin.

TABLE 3.

Variables associated with clinical failure in multivariable analysisa

| Factor | Unadjusted OR | 95% CI for unadjusted OR | aOR | 95% CI for aOR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICU admission | 2.47 | 1.41–4.32 | 2.49 | 1.37–4.53 |

| Vancomycin group | 2.05 | 1.20–3.34 | 2.15 | 1.26–3.68 |

| Source control | 0.52 | 0.29–0.91 | 0.55 | 0.30–1.02 |

| Infective endocarditis | 2.94 | 1.55–5.59 | 2.15 | 1.26–3.68 |

| Bone/joint infection | Removed from model | |||

| Vancomycin BMD MIC | 0.87 | 0.43–1.74 | Removed from model | |

| Acute kidney injury | Removed from model | |||

| i.v. drug use | Removed from model | |||

| Complicated bacteremia | Not tested |

Hosmer-Lemmeshow, P = 0.726.

FIG 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of probability of 30-day survival for vancomycin-treated versus daptomycin-treated patients.

Adverse drug reactions were infrequent, being documented in 11.5% of patients in both treatment groups. Three patients (2.3%) in the daptomycin arm experienced elevations in the CPK concentration to >2,000 IU/liter, and two (1.5%) of these patients were reported to have myopathy. These patients were switched to alternative agents; two were switched back to vancomycin, and one was switched to linezolid. After switching to an alternative agent, CPK levels decreased. Among the vancomycin-treated patients, 12 (9.2%) were reported to have developed nephrotoxicity. One of these patients was subsequently placed on renal replacement therapy. This patient presented with an estimated creatinine clearance of 37.9 ml/min and a vancomycin trough concentration of 14.3 mg/liter.

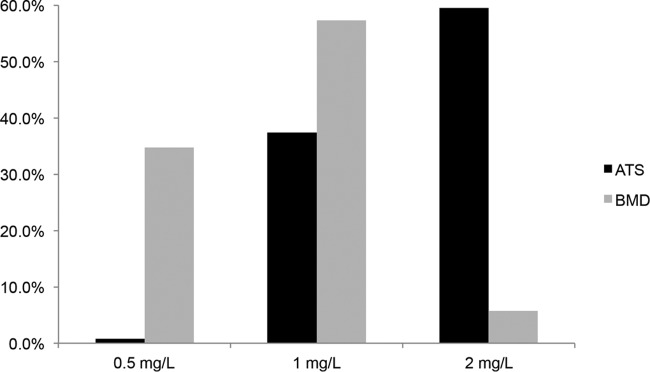

There was a high level (73.7%) of discordance between ATS MICs and BMD MICs for vancomycin (Figure 3). By the ATS methodology, 59.5% of all isolates demonstrated a vancomycin MIC of 2 mg/liter; by the BMD methodology, only 5.7% of the isolates had a vancomycin MIC of 2 mg/liter. The level of agreement between the methodologies was low (2.2%) at a vancomycin MIC of 0.5 mg/liter and increased with higher vancomycin MICs. There was a higher level of agreement between the ATS and BMD methodologies for daptomycin MICs. The majority of isolates had daptomycin MICs of ≤0.5 mg/liter by both the ATS and BMD methodologies (94.5%). There were no significant differences in molecular characteristics between isolates from the daptomycin-treated and vancomycin-treated patients, including SCCmec type IV (58.8% versus 64.9%), USA300 (43.5% versus 49.6%), the presence of PVL (42.0% versus 51.1%), and agr group I (53.4% versus 59.5%), respectively. Additionally, agr dysfunction was present in 26.0% of daptomycin-treated patients and 26.7% of vancomycin-treated patients.

FIG 3.

Vancomycin MIC distribution by ATSs versus BMD.

DISCUSSION

The current IDSA MRSA treatment guidelines recommend consideration of agents other than vancomycin in the face of persistent or worsening signs and symptoms regardless of the vancomycin MIC (4). While numerous previous studies have demonstrated a correlation between increased vancomycin MIC and treatment failure, this is still an issue of clinical debate. For instance, although previous meta-analyses have reported worse outcomes in patients with MRSA BSIs caused by isolates with elevated vancomycin MICs, the most recent meta-analysis did not find such an association (5, 9). The current study demonstrated improved outcomes in daptomycin-treated patients, including patients infected with isolates with vancomycin MICs of 0.5 mg/liter and 1.0 mg/liter by BMD. Forty-five percent of vancomycin-treated patients met the predefined criteria of clinical failure by meeting at least one of the composite metrics. This result was aligned with the results of previous studies directly comparing vancomycin to daptomycin for the treatment of MRSA BSIs, which reported vancomycin treatment failure rates of 25% to 45% (10, 13–16, 30). Overall, the 30-day all-cause mortality rate was low (15.3% versus 6.1%; P = 0.01) but aligned with the results of previous studies. In particular, it is interesting to note that in a study by Moore et al., there was no significant difference in clinical failure rates; however, the 60-day all-cause mortality rate was higher in the vancomycin-treated patients (20% versus 9% in daptomycin-treated patients; P = 0.049) (13). The current findings related to all-cause 30-day mortality, as with the clinical failure composite, were regardless of the vancomycin MIC by BMD and persisted when outcomes were stratified by vancomycin BMD MIC.

In the studies by Kullar et al. (15) and Murray et al. (14), clinical failure was largely driven by higher proportions of patients with bacteremia persistent for ≥7 days among the vancomycin-treated patients than among the daptomycin-treated patients (44.3% versus 21.0% [P < 0.001] in the study by Kullar et al. [15] and 42.4% versus 18.8% [P = 0.001] in the study by Murray et al. [14]). In the current study, the rate of persistent bacteremia was lower than that previously reported in vancomycin-treated patients and was similar between the two groups (26.0% versus 22.1%; P = 0.47). Additionally, the median length of bacteremia was 3 to 4 days (IQR, 2.0 to 6.5 days), which is shorter than that previously reported. There are several possible explanations for the current finding. To address the shortcomings of our previous studies, we included patients with i.v. catheters as the primary site of infection, as such patients frequently experience shorter durations of bacteremia. Patients with these infections represented approximately 10% of the entire study population. The increased readiness to change to an alternative agent or add therapy for potential synergy in vancomycin-treated patients more likely contributed to the shorter duration of bacteremia. The requirement for a change in anti-MRSA therapy was significantly higher in vancomycin-treated patients than daptomycin-treated patients (28.2% versus 15.3%; P = 0.05), and this occurred at a median of 136.1 h (IQR, 113.7 to 194.5 h) after the initiation of vancomycin. This readiness to switch to an alternative agent is likely secondary to advocating for more aggressive management and evidence for the use of synergistic combination therapies in patients with MRSA BSIs described in recent publications (31–35).

Additionally, in the current study, vancomycin MICs were confirmed using CLSI BMD, which is the current “gold standard” (26). This is important, as previous studies have found discrepancies between the results obtained with ATSs and BMD (21). Of particular interest, 53 of the 156 (33.9%) isolates determined to have a vancomycin MIC of 2.0 mg/liter by ATSs were determined to have an MIC of 0.5 mg/liter by BMD. Although vancomycin MICs were not determined by Etest, previous studies have demonstrated discordance between the results obtained by ATSs and Etest and a 1-fold higher dilution by Etest than by BMD (18, 20). There is considerably less information on the concordance of daptomycin MICs obtained by ATSs and BMD; however, the level of agreement seems to be higher than that seen with vancomycin (36). In the current study, daptomycin MICs demonstrated greater than 90% agreement by the two methods when the MIC was ≤0.5 mg/liter. These findings highlight the lack of precision of ATSs for determination of vancomycin MICs and the need to further evaluate how best to navigate this difficult clinical situation, as BMD is perceived to be too time intensive to be used on all patient isolates.

There are several important strengths and limitations to the current study. Although this was a multicenter study, the participating institutions were all in southeastern Michigan, which may limit external validity. Additionally, due to the retrospective nature of data collection, certain metrics may have been missed, such as readmissions to other sites. As in the study by Murray et al., only patients that were switched to daptomycin within 72 h were included in the analysis (14). This measure, along with the use of propensity analysis, was used to limit selection and prescribing bias. Among the vancomycin-treated patients, initial steady-state trough levels achieved the goal of ≥15 mg/liter in only 55% of patients. This represents a potential limitation in terms of pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamics (PK/PD) optimization of vancomycin compared to daptomycin but also represents current real-world practices. In the study by Moore et al., vancomycin trough concentrations achieved the goal of 15 mg/liter in 66% of vancomycin-treated patients (13). In the study by Weston et al. (16), the median vancomycin level was 15.3 mg/liter (range, 8.2 to 25.6 mg/liter), and Murray et al. (14) reported median trough levels of 17.6 mg/liter (IQR, 14.9 to 21.2 mg/liter), similar to the levels reported in the current study. Additionally, several studies have demonstrated that the current practice of measuring trough concentrations does not adequately correlate to the true PK/PD index of an area under the concentration-time curve (AUC)/MIC of ≥400. Of note, up to 60% of patients with a trough concentration of <15 mg/liter still achieved this PK/PD index. The inability to measure AUC in this cohort represents a limitation of the current study (37–39).

In conclusion, an early switch to daptomycin in patients with MRSA BSIs was associated with improved outcomes compared to those achieved with vancomycin regardless of the vancomycin MIC determined by BMD. Both the 30-day all-cause mortality and the MRSA infection-related mortality rates were lower in the daptomycin-treated patients. There were significant discrepancies between BMD and ATSs in terms of the vancomycin MIC, with numerous isolates reported to have a 2-log difference in MICs. The limitation of ATSs should be considered while treating MRSA BSIs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This was an investigator-initiated study funded by Merck & Co., Kenilworth, NJ. M.J.R. was partially supported by NIH grant R21 AI109266-01.

S.L.D. has received grant support from Cubist (now Merck) and Actavis and has served as a consultant for Actavis, Premier, and Pfizer. M.J.R. has received grant support, participated on speaker's bureaus, or consulted for Actavis, Bayer, Cempra, Cubist (now Merck), The Medicine Company, Sunovian, and Theravance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sievert DM, Ricks P, Edwards JR, Schneider A, Patel J, Srinivasan A, Kallen A, Limbago B, Fridkin S, National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Team and Participating NHSN Facilities. 2013. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009-2010. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 34:1–14. doi: 10.1086/668770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Hal SJ, Jensen SO, Vaska VL, Espedido BA, Paterson DL, Gosbell IB. 2012. Predictors of mortality in Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Microbiol Rev 25:362–386. doi: 10.1128/CMR.05022-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bassetti M, Trecarichi EM, Mesini A, Spanu T, Giacobbe DR, Rossi M, Shenone E, Pascale GD, Molinari MP, Cauda R, Viscoli C, Tumbarello M. 2012. Risk factors and mortality of healthcare-associated and community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. Clin Microbiol Infect 18:862–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, Daum RS, Fridkin SK, Gorwitz RJ, Kaplan SL, Karchmer AW, Levine DP, Murray BE, Rybak MJ, Talan DA, Chambers HF, Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2011. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis 52:e18–e55. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Hal SJ, Lodise TP, Paterson DL. 2012. The clinical significance of vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration in Staphylococcus aureus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 54:755–771. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacob JT, DiazGranados CA. 2013. High vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration and clinical outcomes in adults with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: a meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis 17:e93–e100. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wi YM, Kim JM, Joo EJ, Ha YE, Kang CI, Ko KS, Chung DR, Song JH, Peck KR. 2012. High vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration is a predictor of mortality in meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. Int J Antimicrob Agents 40:108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Honda H, Doern CD, Michael-Dunne W Jr, Warren DK. 2011. The impact of vancomycin susceptibility on treatment outcomes among patients with methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. BMC Infect Dis 11:335. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalil AC, Van Schooneveld TC, Fey PD, Rupp ME. 2014. Association between vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration and mortality among patients with Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 312:1552–1564. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.6364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soriano A, Marco F, Martinez JA, Pisos E, Almela M, Dimova VP, Alamo D, Ortega M, Lopez J, Mensa J. 2008. Influence of vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration on the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis 46:193–200. doi: 10.1086/524667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fowler VG Jr, Boucher HW, Corey GR, Abrutyn E, Karchmer AW, Rupp ME, Levine DP, Chambers HF, Tally FP, Vigliani GA, Cabell CH, Link AS, DeMeyer I, Filler SG, Zervos M, Cook P, Parsonnet J, Bernstein JM, Price CS, Forrest GN, Fatkenheuer G, Gareca M, Rehm SJ, Brodt HR, Tice A, Cosgrove SE, S. aureus Endocarditis and Bacteremia Study Group. 2006. Daptomycin versus standard therapy for bacteremia and endocarditis caused by Staphylococcus aureus. N Engl J Med 355:653–665. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rehm SJ, Boucher H, Levine D, Campion M, Eisenstein BI, Vigliani GA, Corey GR, Abrutyn E. 2008. Daptomycin versus vancomycin plus gentamicin for treatment of bacteraemia and endocarditis due to Staphylococcus aureus: subset analysis of patients infected with methicillin-resistant isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother 62:1413–1421. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore CL, Osaki-Kiyan P, Haque NZ, Perri MB, Donabedian S, Zervos MJ. 2012. Daptomycin versus vancomycin for bloodstream infections due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with a high vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration: a case-control study. Clin Infect Dis 54:51–58. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray KP, Zhao JJ, Davis SL, Kullar R, Kaye KS, Lephart P, Rybak MJ. 2013. Early use of daptomycin versus vancomycin for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia with vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration >1 mg/liter: a matched cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 56:1562–1569. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kullar R, Davis SL, Kaye KS, Levine DP, Pogue JM, Rybak MJ. 2013. Implementation of an antimicrobial stewardship pathway with daptomycin for optimal treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Pharmacotherapy 33:3–10. doi: 10.1002/phar.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weston A, Golan Y, Holcroft C, Snydman DR. 2014. The efficacy of daptomycin versus vancomycin for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infection in patients with impaired renal function. Clin Infect Dis 58:1533–1539. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crompton JA, North DS, Yoon M, Steenbergen JN, Lamp KC, Forrest GN. 2010. Outcomes with daptomycin in the treatment of Staphylococcus aureus infections with a range of vancomycin MICs. J Antimicrob Chemother 65:1784–1791. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bland CM, Porr WH, Davis KA, Mansell KB. 2010. Vancomycin MIC susceptibility testing of methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates: a comparison between Etest(R) and an automated testing method. South Med J 103:1124–1128. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181efb5b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsu DI, Hidayat LK, Quist R, Hindler J, Karlsson A, Yusof A, Wong-Beringer A. 2008. Comparison of method-specific vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration values and their predictability for treatment outcome of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents 32:378–385. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen SY, Liao CH, Wang JL, Chiang WC, Lai MS, Chie WC, Chang SC, Hsueh PR. 2014. Method-specific performance of vancomycin MIC susceptibility tests in predicting mortality of patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. J Antimicrob Chemother 69:211–218. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rybak MJ, Vidaillac C, Sader HS, Rhomberg PR, Salimnia H, Briski LE, Wanger A, Jones RN. 2013. Evaluation of vancomycin susceptibility testing for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: comparison of Etest and three automated testing methods. J Clin Microbiol 51:2077–2081. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00448-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. 2009. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaasch AJ, Barlow G, Edgeworth JD, Fowler VG Jr, Hellmich M, Hopkins S, Kern WV, Llewelyn MJ, Rieg S, Rodriguez-Bano J, Scarborough M, Seifert H, Soriano A, Tilley R, Torok ME, Weiss V, Wilson AP, Thwaites GE, ISAC, INSTINCT, SABG, UKCIRG, and colleagues . 2014. Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infection: a pooled analysis of five prospective, observational studies. J Infect 68:242–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rybak MJ, Lomaestro BM, Rotschafer JC, Moellering RC, Craig WA, Billeter M, Dalovisio JR, Levine DP. 2009. Vancomycin therapeutic guidelines: a summary of consensus recommendations from the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Clin Infect Dis 49:325–327. doi: 10.1086/600877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merck & Co. 2015. Cubicin. Highlights of prescribing information. Merck & Co., Whitehouse Station, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2014. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang K, McClure J-A, Elsayed S, Louie T, Conly JM. 2008. Novel multiplex PCR assay for simultaneous identification of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains USA300 and USA400 and detection of mecA and Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes, with discrimination of Staphylococcus aureus from coagulase-negative staphylococci. J Clin Microbiol 46:1118–1122. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01309-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Milheirico C, Oliveira DC, de Lencastre H. 2007. Multiplex PCR strategy for subtyping the staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec type IV in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: ‘SCCmec IV multiplex.’ J Antimicrob Chemother 60:42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schweizer ML, Furuno JP, Sakoulas G, Johnson JK, Harris AD, Shardell MD, McGregor JC, Thom KA, Perencevich EN. 2011. Increased mortality with accessory gene regulator (agr) dysfunction in Staphylococcus aureus among bacteremic patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:1082–1087. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00918-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lodise TP, Graves J, Evans A, Graffunder E, Helmecke M, Lomaestro BM, Stellrecht K. 2008. Relationship between vancomycin MIC and failure among patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia treated with vancomycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:3315–3320. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00113-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kullar R, McKinnell JA, Sakoulas G. 2014. Avoiding the perfect storm: the biologic and clinical case for reevaluating the 7-day expectation for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia before switching therapy. Clin Infect Dis 59:1455–1461. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Claeys KC, Smith JR, Casapao AM, Mynatt RP, Avery L, Shroff A, Yamamura D, Davis SL, Rybak MJ. 2015. Impact of the combination of daptomycin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole on clinical outcomes in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:1969–1976. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04141-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dhand A, Sakoulas G. 2014. Daptomycin in combination with other antibiotics for the treatment of complicated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Ther 36:1303–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moise PA, Amodio-Groton M, Rashid M, Lamp KC, Hoffman-Roberts HL, Sakoulas G, Yoon MJ, Schweitzer S, Rastogi A. 2013. Multicenter evaluation of the clinical outcomes of daptomycin with and without concomitant beta-lactams in patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and mild to moderate renal impairment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:1192–1200. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02192-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dhand A, Bayer AS, Pogliano J, Yang SJ, Bolaris M, Nizet V, Wang G, Sakoulas G. 2011. Use of antistaphylococcal beta-lactams to increase daptomycin activity in eradicating persistent bacteremia due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: role of enhanced daptomycin binding. Clin Infect Dis 53:158–163. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kruzel MC, Lewis CT, Welsh KJ, Lewis EM, Dundas NE, Mohr JF, Armitige LY, Wanger A. 2011. Determination of vancomycin and daptomycin MICs by different testing methods for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol 49:2272–2273. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02215-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pai MP, Neely M, Rodvold KA, Lodise TP. 2014. Innovative approaches to optimizing the delivery of vancomycin in individual patients. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 77:50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lodise TP, Drusano GL, Zasowski E, Dihmess A, Lazariu V, Cosler L, McNutt LA. 2014. Vancomycin exposure in patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections: how much is enough? Clin Infect Dis 59:666–675. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neely MN, Youn G, Jones B, Jelliffe RW, Drusano GL, Rodvold KA, Lodise TP. 2014. Are vancomycin trough concentrations adequate for optimal dosing? Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:309–316. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01653-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fowler VG, Olsen MK, Corey GR, Woods CW, Cabell CH, Reller LB, Cheng AC, Dudley T, Oddone EZ. 2003. Clinical identifiers of complicated Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Arch Intern Med 163:2066–2072. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.17.2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]