Abstract

Hedera helix L., a member of Araliaceae family, has antiproliferative, cytotoxic, antimicrobial, antifungal, antiprotozoal and anti-inflammatory effects, and is used in cosmetics. The aim of the present study was to investigate the effect of treatment with extracts of leaves and unripened fruits of H. helix on rat prostate cancer cell lines with markedly different metastatic potentials: Mat-LyLu cells (strongly metastatic) and AT-2 cells (weakly metastatic). The effects of the extracts on cell kinetics and migration were determined. Tetrodotoxin was used to block the voltage-gated sodium channels (VGSCs) associated specifically with Mat-LyLu cells. Cell proliferation was detected spectrophotometrically using the 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide assay. The mitotic index was determined using the Feulgen staining method. Lateral motility was quantified by wound-healing assays. The results of the present study demonstrated that cell kinetics (proliferation and mitotic activity) and motility were inhibited by ethanolic leaf extract of H. helix. The ethanolic extract of H. helix fruit suppressed Mat-LyLu cell migration, with no effect on proliferation. The opposite effects were observed in AT-2 cells; migration was not affected but proliferation was inhibited. In conclusion, the ethanolic fruit extract of H. helix may inhibit the cell migration of Mat-LyLu cells by blocking VGSCs. However, the effect of ethanolic leaf extract of H. helix treatment on the lateral motility of the cancer cells is unclear.

Keywords: prostate cancer, Hedera helix, Mat-LyLu cells, voltage-gated sodium channel, cell proliferation, cell migration

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the second most common cause of cancer-associated mortality among men worldwide (1). By the time prostate cancer is diagnosed, metastasis has occurred in the majority of men, as early prostate cancer has no symptoms. Metastatic diseases are a significant public health problem affecting cancer patients and their families (2). Metastasis occurs when malignant cells leave the primary tumor, migrate via the circulatory system, localize in distant areas and lead to the development of secondary tumors. It is a multistep process, and the steps are similar in all tumors. Mobilization of tumor cells is an important step in metastasis (3). Ion channels regulate, and stimulate numerous behavioral changes in cells that are associated with cancer and metastasis, including cell movement (elongation and lateral motility) (4,5), migration, galvanotaxis (6) and invasion (7,8). A number of in vitro (9–11) and in vivo (12) studies performed using tetrodotoxin (TTX), which specifically blocks voltage-gated sodium channels (VGSCs) (13), have suggested that the plasma membrane of prostate cancer cells may gain a more excitable phenotype due to increased VGSC expression, and thus malignancy is able to progress. Bennett et al (11) demonstrated that VGSC expression was ‘necessary’ and ‘enough’ for the invasiveness of prostate cancer cells. Prostate cancer tends to invade the bones, lungs and lymph nodes (14). Combating metastasis formation and growth are important for successfully treating the disease (2). Various studies have revealed targeted pharmacological agents aiming to prevent metastasis and inhibit proliferation (5,6). However, serious side effects of chemotherapy have encouraged people to request treatment by using natural agents. Therefore, alternative and complementary treatments for combating illnesses have increased in popularity. Investigation of novel and effective therapeutics obtained from natural sources, including plants and other organisms, is necessary.

The leaves and fruits of Hedera helix L. (common name, ivy; family, Araliaceae) mainly contain triterpenoid saponins (15,16). Saponin derivatives obtained from Hedera spp. have numerous biological activities, including antiproliferative, cytotoxic (17,18), antibacterial (19), antifungal (20), anthelmintic (21), antileishmanial (22), anti-elastase and anti-hyaluronidase (23) effects. de Medeiros et al (24) demonstrated that H. helix spp. canariensis exhibits strong antithrombin activity, and suggested that there may be a correlation between the antithrombin activity and a reduction in tumor cell spread. However, to the best of our knowledge, no investigation into the potential effects of H. helix on tumor cell migration has been conducted.

The main aims of the present study were as follows: i) To investigate whether ethanolic extracts from H. helix leaves and unripened fruits (HLE and HFE, respectively) have antiproliferative effects on rat prostate cancer cell lines and, ii) to investigate how lateral cell motility is affected by these extracts to reveal the potential effects on cell migration.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The present study used the highly metastatic Mat-LyLu cell line and the weakly metastatic AT-2 cell line, which were derived from the same Dunning rat prostate tumor (25). These cell lines were obtained from Imperial College, London (UK), and were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 1% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum, 1% l-glutamine and 0.5% dexamethasone. The cells were maintained under cell culture conditions of 37°C and 5% CO2 in a humidified chamber. All chemicals for the cell culture were purchased from Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

Preparation of extracts

H. helix L. (family, Araliaceae) was collected in winter from rural areas of Mersin, located in the Mediterranean region of Turkey. The plant samples were identified by Professor Tuna Ekim from Istanbul University (Istanbul, Turkey). Voucher specimens of the plant were stored in the Herbarium of the Faculty of Science at the University of Istanbul (ISTF Herbarium number, 40074). Following identification, shiny, light green H. helix leaves and unripened fruits were washed and dried in a chamber at 40°C for 24 h. The dry samples (500 g) were powdered mechanically and extracted using ethanol (>98%; Honeywell Riedel-de Haën AG, Seelze, Germany; 1:10 w/v) in an orbital shaker at room temperature for at least 24 h. These extracts were filtrated using Whatman filter paper no. 4. Following filtration, the supernatant was lyophilized at −40°C under a vacuum (Edwards, Crawley, UK). Following lyophilization, the weight of crude extracts was 11 and 7 g for H. helix leaves and fruits, respectively.

Preparation of test medium

Stock solutions (10 mg/ml) of the extracts were prepared using RPMI medium with the aforementioned supplements. Stock solutions were filtered using 0.45- or 0.20-µm-diameter disposable filters. The final concentrations of the HLE were 25, 50 and 75 µg/ml and the final concentrations of the HFE were 18, 20 and 22 µg/ml. The extracts were diluted in conditioned RPMI medium. The concentrations were selected as result of preliminary toxicity assays (described below). TTX was prepared according to the manufacturer's protocol (Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel). Briefly, 1 mg TTX was dissolved in 1 ml sterile distilled water. The stock solution (3,132 µM) of TTX was frozen in aliquots and stored at −20°C until use. The test concentration of TTX (200 nM) was diluted in conditioned RPMI medium.

Toxicity assay

Trypan blue exclusion assays, which are based on living cells excluding trypan blue dye (4), were performed to determine whether the ivy extracts and TTX had toxic effects on the cell lines. After treatment of the cell lines with the ivy extracts or TTX for 48 h, trypan blue dye (4%; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added into the cell culture dishes (Greiner BioOne GmbH, Frickenhausen, Germany). The live/dead cell number was counted by using an inverted microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) (40X objective).

Proliferation assay

The effects of the HLE and HFE on the proliferation of Dunning model rat prostate cancer cell lines were assayed spectrophotometrically using the 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) reagent (Sigma-Aldrich), as described previously (5). A total of 3×104 cells per dish were plated into 35-mm-diameter cell culture dishes. The cells were left to incubate for 24 h undisturbed, and following this, the medium was replaced daily for 2 days while incubation continued. In the control dishes, fresh supplemented RPMI medium was used. In the test dishes, fresh test medium of various concentrations was used. To determine the cell proliferation, spectrophotometric measurements were performed using the MTT assay 48 h subsequent to the addition of the test medium. Absorbance of MTT was measured at 570 nm. The cell counts were normalized using the absorbance values of the test groups compared with the control group. Additionally, the cell inhibition rates were calculated proportionally on the basis of the absorbance value of the control group.

Mitotic activity

The mitotic index (MI) was determined by observing the effects of the extracts on the mitotic activity of prostate cancer cell lines. The cells were plated on coverslips and treated with control or test media for 48 h. The cells were then fixed using Clarke's fluid (ethanol:acetic acid, 3:1) and stained using the Feulgen method (26). The number of cells in the mitotic phases (including the late prophase, metaphase, anaphase and telophase; n) per total cells (4,000–6,000; C) was determined by the same person. The MI (%) was calculated using the following formula: MI=(n/C)×100.

Migration assay

The effect of H. helix extracts on cell motility was evaluated using wound healing assays (5). Cells were plated in 35-mm-diameter cell culture dishes at an initial concentration of 15×104 cells per dish. Following 24 h of incubation at 37°C, three parallel scratches per dish were made using a sterile pipette tip. The initial widths (mm) of these wounds (W0) were measured using a graticule on an inverted microscope (Olympus) (10X objective). A total of 24–48 h after the initial measurement, the widths of the wounds were measured again (Wt). The control and test media were replaced at 24 and 48 h following plating. Motility index (MoI) was calculated using the formula: MoI=1-(Wt/W0).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard error. Student's t-test, the comparison test of two ratios and the Pearson correlation test were used to compare the data. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. Statistical tests were performed using Microsoft Office Excel 2007 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and SPSS version 11.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Initial findings

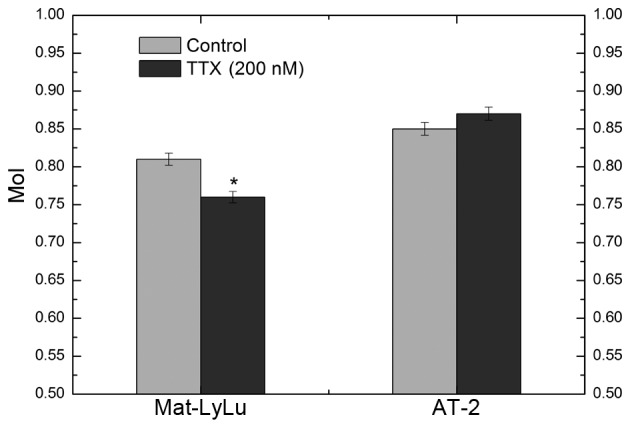

In the present study, an initial evaluation was performed to determine the non-toxic concentrations of HLE and HFE on the two cell lines (Mat-LyLu and AT-2) by using a trypan blue exclusion assay. HLE (25, 50 and 75 µg/ml) and HFE (18, 20 and 22 µg/ml) were not toxic against the cells following 48 h of incubation. Thus, these non-toxic concentrations were used in the subsequent experiments. In addition, 200 nM TTX did not demonstrate toxicity against the two cell lines. Metastatic properties of Mat-LyLu and AT-2 cells are closely associated with VGSCs, as has been demonstrated in studies on TTX, which specifically blocks VGSCs (4,7,8,11). In the present study, 200 nM TTX was used as the positive control, as it has been previously reported that TTX does not produce changes in the proliferation of either cell line even at higher doses (600 nM and 6 µM) than 200 nM (5,7,27). TTX reduced the movement distance of Mat-LyLu cells in a lateral direction, and this effect was found to be statistically significant. The MoI was 0.81±0.02 and 0.76±0.02 for the control (non-treated) and test (TTX-treated) groups, respectively (P<0.01). The MoI for AT-2 cells was 0.85±0.01 in the control and 0.87±0.03 in the test groups. No significant difference was observed between the control and TTX-treated groups in AT-2 cells (P>0.05; Fig. 1). The aforementioned data revealed that the cell lines maintained their metastatic properties (Mat-LyLu strongly metastatic and AT-2 weakly metastatic) associated with VGSCs.

Figure 1.

MoI of Mat-LyLu and AT-2 cell lines following 48 h of treatment with 200 nM TTX. TTX decreased the movement distance of the Mat-LyLu cell line, but not of the AT-2 cell line. MoI, motility index; TTX, tetrodotoxin. *P<0.01 vs. the control.

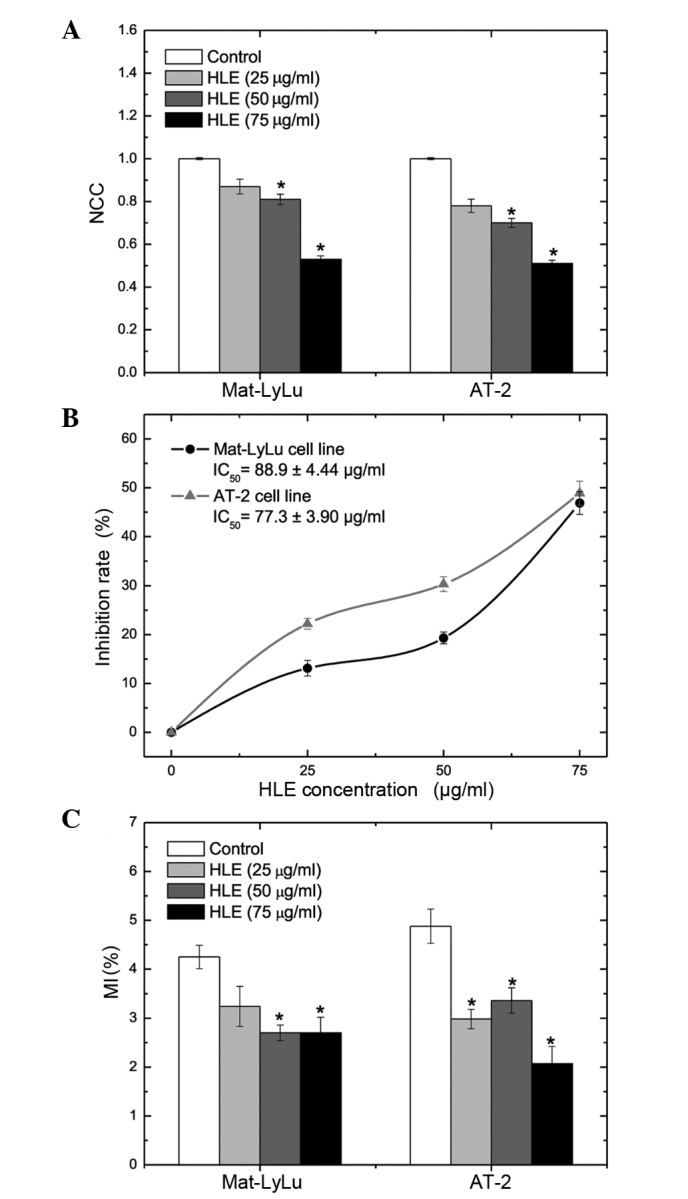

Cell kinetics

HLE treatment of Mat-LyLu and AT-2 cells for 48 h resulted in significant inhibition of cell proliferation at 50 and 75 µg/ml (P<0.01). Normalized cell counts (NCCs) of Mat-LyLu cells were 0.87±0.03, 0.81±0.02 and 0.53±0.02 following treatment with 25, 50 and 75 µg/ml of HLE for 48 h, respectively. Following 48 h of incubation, the NCCs of AT-2 cells were 0.78±0.03, 0.70±0.02 and 0.51±0.02 for 25, 50 and 75 µg/ml HLE, respectively (Fig. 2A). The inhibition rates (%) of Mat-LyLu cell proliferation were 19.3±1.20 for 50 µg/ml and 46.9±2.34 for 75 µg/ml HLE. HLE treatment for 48 h produced increased rates of inhibition on AT-2 cell proliferation compared with Mat-LyLu cells. The inhibition rates (%) for AT-2 cells were 30.3±1.51 and 48.9±2.44 for 50 and 75 µg/ml HLE, respectively. The half-maximal (50%) inhibitory concentration (IC50) of HLE on cell growth at 48 h was 88.9±4.44 µg/ml for Mat-LyLu cells and 77.3±3.90 µg/ml for AT-2 cells (Fig. 2B). Following HLE treatment, mitotic activity decreased in both cell lines. The MI (%) was 4.25±0.24 in the Mat-LyLu cell control group. The Mat-LyLu cell MI (%) decreased to 3.24±0.41, 2.70±0.16 and 2.70±0.32 as result of treatment with 25, 50 and 75 µg/ml HLE for 48 h, respectively. In a similar manner, the MI (%) of AT-2 cells decreased from 4.88±0.35 (control group) to 2.07±0.35 (75 µg/ml HLE treatment; Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Effects of HLE on cell kinetics (proliferation and mitotic activity) of Mat-LyLu and AT-2 cell lines. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error. (A) NCCs of Mat-LyLu and AT-2 cell lines following treatment with HLE for 48 h. Cell proliferation was suppressed by treatment with the extract, in a dose-dependent manner. (B) The inhibition rates (%) of cell proliferation at 48 h. The IC50 values were 88.9 and 77.3 µg/ml for Mat-LyLu and AT-2 cells, respectively. (C) MI (%) values for Mat-LyLu and AT-2 cells. Mitotic activity and cell proliferation were suppressed by HLE treatment in both cell lines. *P<0.05 vs. the control. HLE, Hedera helix leaf extract; NCC, normalized cell count; IC50, half-maximal (50%) inhibitory concentration; MI, mitotic index.

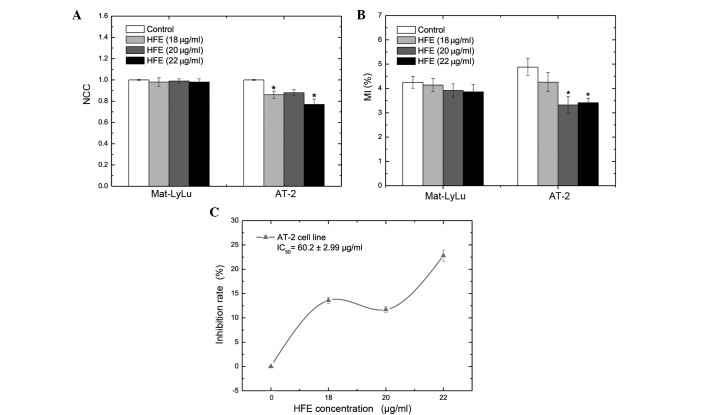

HFE did not produce a significant change in proliferation (Fig. 3A) or mitotic activity (Fig. 3B) in the Mat-LyLu cell line. However, HFE significantly suppressed proliferation and mitotic activity of AT-2 cells at 18 and 22 µg/ml concentrations, with inhibition rates (%) of 13.6±0.68 and 22.8±1.14, respectively (Fig. 3A-C). The MI (%) of AT-2 cells was 3.41±0.19 following treatment with 22 µg/ml HFE for 48 h, while the MI (%) was 4.88±0.35 in the control group (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Effects of HFE on kinetic parameters (proliferation and mitotic activity) of Mat-LyLu and AT-2 cell lines. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error. (A) NCCs of Mat-LyLu and AT-2 cell lines following treatment with HFE for 48 h. The proliferation of Mat-LyLu cells was not affected by HFE treatment. However, HFE treatment suppressed the proliferation of AT-2 cells. (B) The IC50 value was 60.2 µg/ml for AT-2 cells. (C) MI% values are presented in the figure. HFE treatment did not affect the mitotic activity of Mat-LyLu cells. However, HFE treatment suppressed the mitotic activity of AT-2 cells. *P<0.01 vs. the control. HFE, Hedera helix fruit extract; NCC, normalized cell count; IC50, half-maximal (50%) inhibitory concentration; MI, mitotic index.

Cell migration

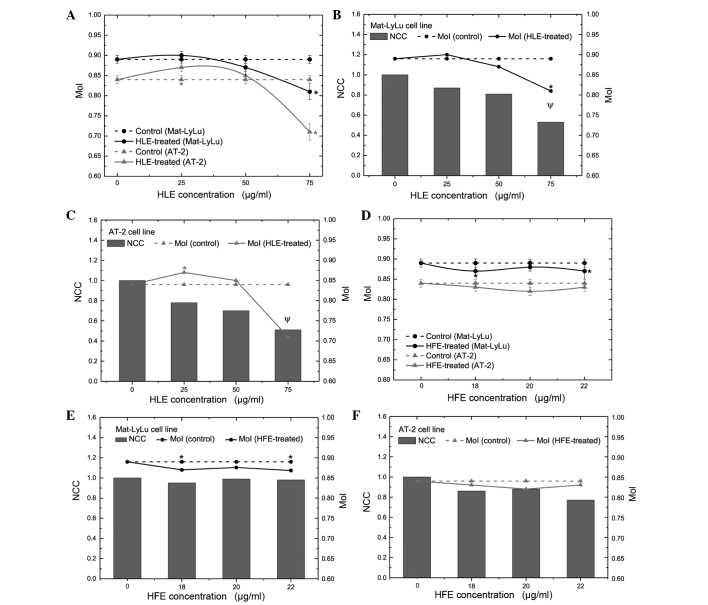

In the present study, the effect of HLE and HFE on lateral motility of both cell lines was investigated using wound healing assays. HLE reduced the distance of movement in a lateral direction in both cell lines (Table I; Fig. 4A). MoI was 0.89±0.01 in the Mat-LyLu cell control group. Following 75 µg/ml HLE treatment for 48 h, the MoI of Mat-LyLu cells reduced to 0.81±0.02 (P<0.01). The MoI of the AT-2 cells was 0.84±0.01 and 0.71±0.02 in the control and 75 µg/ml HLE test groups, respectively. It was determined that the difference between the control and test groups was statistically significant (P<0.01). The MoI decreased by 8.83 and 15.7% in the Mat-LyLu and AT-2 cell lines, respectively. Considering the changing MoI and rate of inhibition of cell proliferation, it was suggested that the MoI may decrease due to the inhibition of proliferation in the investigated cell lines (Fig. 4B and C). A strong positive correlation was noted between the decrease of MoI and proliferation (r2=0.97; P<0.01). In addition, HFE treatment reduced the movement distance of Mat-LyLu cells, but not AT-2 cells (Table II; Fig. 4D). The MoI for Mat-LyLu cells was 0.89±0.01 and 0.87±0.02 in the control and 22 µg/ml test groups, respectively (P<0.05). However, no difference in MoI was observed between the control and test groups for the AT-2 cells. Notably, HFE treatment did not affect the kinetic parameters (proliferation and mitotic activity) of Mat-LyLu cells, while suppressing the growth of AT-2 cells. Additionally, no significant correlation was observed between the decrease of MoI and proliferation of Mat-LyLu cells (r2=0.05; P>0.05). Due to this, the present study concluded that HFE treatment reduced the motility of Mat-LyLu cells without affecting their proliferation (Fig. 4E and F).

Table I.

Initial MoI and change in MoI in Mat-LyLu and AT-2 cell lines following treatment with ethanolic extract of HLE for 48 h.

| MoIa | Change in MoI, %b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Mat-LyLu | AT-2 | Mat-LyLu | AT-2 |

| Control | 0.89±0.01 | 0.84±0.01 | – | – |

| HLE, 25 µg/ml | 0.90±0.01 | 0.87±0.01c | −0.77 (↑) | −3.96 (↑)c |

| HLE, 50 µg/ml | 0.87±0.02 | 0.85±0.01 | 2.98 (↓) | −0.48 (↑) |

| HLE, 75 µg/ml | 0.81±0.02c | 0.71±0.02c | 8.83 (↓)c | 15.72 (↓)c |

MoI=1-(second measurement of width of wounds/initial width of wounds).

(↓), indicates a decrease in motility index; (↑), indicates an increase in motility index.

Statistically significant (P<0.01 vs. control). MoI, motility index; HLE, Hedara helix leaves.

Figure 4.

MoI vs. NCC following treatment with HLE and HFE extract for 48 h. Bars symbolize NCCs and lines represent MoI. (A) Movement distances of both cell lines in a lateral direction decreased in the test (HLE-treated) group compared to the control (non-treated) group. MoI vs. NCC for (B) Mat-LyLu and (C) AT-2 cells. Motility indices co-varied with alteration of proliferation in both cell lines following 48 h of treatment with HLE. Positive correlation was observed between the MoI and cell proliferation (P<0.01). (D) Movement distances of Mat-LyLu cells in a lateral direction decreased in the test (HFE-treated) group compared to the control (non-treated) group. No change was observed in the motility index of AT-2 cells. (E) HFE reduced Mat-LyLu cell movement distance in a lateral direction, but not cell proliferation. No significant correlation was observed between the decrease of MoI and Mat-LyLu cell proliferation (P>0.05). (F) The motility index of AT-2 cells was not affected by HFE treatment, but cell proliferation was inhibited. *P<0.05 vs. the control. ΨPositive correlation between MoI and cell proliferation of Mat-LyLu or AT-2 cell lines following treatment with HLE (P<0.01). MoI, motility index; NCC, normalized cell count; HLE, Hedera helix leaf; HFE, Hedera helix fruit.

Table II.

Initial MoI and change in MoI of Mat-LyLu and AT-2 cell lines following treatment with ethanolic extract of HFE for 48 h.

| MoIa | Change in MoI, %b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Mat-LyLu | AT-2 | Mat-LyLu | AT-2 |

| Control | 0.89±0.01 | 0.84±0.01 | – | – |

| HFE, 18 µg/ml | 0.87±0.01c | 0.83±0.01 | 2.51 (↓)c | 1.64 (↓) |

| HFE, 20 µg/ml | 0.88±0.01 | 0.82±0.01 | 1.87 (↓) | 2.38 (↓) |

| HFE, 22 µg/ml | 0.87±0.02c | 0.83±0.01 | 2.69 (↓)c | 1.55 (↓) |

MoI=1-(second measurement of width of wounds/initial width of wounds).

(↓), indicates a decrease in motility index; (↑), indicates an increase in motility index.

Statistically significant (P<0.05 vs. control). MoI, motility index; HFE, Hedara helix fruit.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study showing the effects of crude H. helix extracts on the growth and migration of rat prostate cancer cell lines (Mat-LyLu and AT-2) of different metastatic potential. Previously, researchers have been focused on in vitro and in vivo studies using saponins and their derivatives obtained from various parts (including, leaves or fruits) of herbal sources, and certain Hedera species (18,28–30). Triterpenoid saponins such as α-hederin, β-hederin, δ-hederin, hederacosides A-I, hederacolchisides (A, A1 and B) and hederagenin are the primary phytochemical components in Hedera spp. (15,16,18). Saponin derivatives isolated from Hedera spp. (18,28) and other plants (29,30) produce antiproliferative, antitumor and cytotoxic effects (18,28), as well a range of other biological activities [including, antimicrobial (19), antifungal (20), anthelmintic (21) and antileishmanial (22)]. In the present study, crude extracts of H. helix leaves and fruits were used. It was determined that the growth of Mat-LyLu and AT-2 cell lines was inhibited by HLE. The inhibition of cell proliferation increased with increasing concentration and application time of HLE. In addition, it was demonstrated that the mitotic activity of these two cell lines was suppressed. Danloy et al (17) reported that α-hederin isolated from H. helix was cytotoxic against B16 mouse melanoma and 3T3 fibroblast cell lines. α-hederin isolated from H. helix leaves potentiated the antitumor activity of 5-fluorouracil in the HT-29 human colon adenocarcinoma cell line (28). Researchers have isolated α-hederin or hederagenin from various plants (29,30). α-Hederin and hederagenin produced weak and strong cytotoxic effects on human bladder carcinoma cell lines (including, J82 and T24), respectively (29). Swamy and Huat (30) reported that α-hederin induces apoptosis and suppresses DNA, RNA and protein synthesis of P388 murine leukemia cells. Barthomeuf et al (18) isolated certain saponin derivatives, including α-hederin, β-hederin, δ-hederin, hederacolchiside (A and A1) and hederagenin, from H. colchica fruits and used them for treating 6 human cancer cell lines (PC-3, DLD-1, PA1, A549, MCF7 and M4Beu) and a human fibroblast cell line. It was observed that hederacolchiside A1 and β-hederin had the highest inhibitory activity on cancer cell lines (18). It was also observed that these two compounds were cytotoxic against fibroblast cells, but that the concentration producing this cytotoxicity was increased compared with the dose required for inhibiting the proliferation of cancer cell lines (18). The present study revealed that HFE inhibited the proliferation and mitosis of only the AT-2 cell line and not Mat-LyLu cells.

The most important step for metastatic spread is the ability to migrate (31). Mat-LyLu and AT-2, from Dunning model rat prostate cancer cell lines, have strong and weak metastatic abilities, respectively (32). Therefore, these cell lines are excellent experimental models for studying the effects of various agents on cell motility and invasion. No previous studies investigating the effect of H. helix on the motility of these cancer cell lines could be identified in the relevant literature. There are a small number of studies showing the effect of H. helix extract(s) on cell migration. de Medeiros et al (24) reported that H. helix spp. canariensis exhibited antithrombin activity and that certain compounds from this plant may prevent blood clotting, thus, blocking tumor cell spread. The results of the present study have demonstrated that HFE is able to inhibit Mat-LyLu cell migration, but has no effect on cell proliferation. By contrast, migration was not affected but proliferation was inhibited in the AT-2 cells. HLE, however, inhibited cell kinetics (proliferation and mitotic activity), as well as motility in Mat-LyLu and AT-2 cell lines.

The initial results indicated that the cell lines used in the present experiments conserved their metastatic properties (Mat-LyLu remained strongly metastatic, and AT-2 remained weakly metastatic) that were closely associated with VGSCs. Therefore, HFE may inhibit cell migration of Mat-LyLu cells by blocking VGSCs. To clarify the underlying mechanism of inhibition and to contribute to research on preventing prostate cancer metastasis, further molecular investigations are required. Our future studies will focus on explaining the phytochemical content of H. helix fruits and investigating the underlying mechanism(s) of their effects on prostate cancer and its metastasis.

Acknowledgements

The present study was partially supported by The Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TUBITAK) [grant no., TBAG-2422 (104T031)]. The authors would like to thank Professor Mustafa B.A. Djamgoz (Department of Life Sciences, Sir Alexander Fleming Building, Imperial College London, South Kensington Campus, London, UK) for supplying the cell lines and his contributions.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- HFE

ethanolic extract of Hedera helix fruits

- HLE

ethanolic extract of Hedera helix leaves

- MI

mitotic index

- MoI

motility index

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide

- NCCs

normalized cell counts

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

- VGSC

voltage-gated sodium channel

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sleeman J, Steeg PS. Cancer metastasis as a therapeutic target. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1177–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arya M, Bott RS, Shergill IS, Ahmed HU, Williamson M, Patel HR. The metastatic cascade in prostate cancer. Surg Oncol. 2006;15:117–128. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fraser SP, Ding Y, Liu A, Foster CS, Djamgoz MB. Tetrodotoxin suppresses morphological enhancement of the metastatic MAT-LyLu rat prostate cancer cell line. Cell Tissue Res. 1999;295:505–512. doi: 10.1007/s004410051256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fraser SP, Salvador V, Manning EA, Mizal J, Altun S, Raza M, Berridge RJ, Djamgoz MB. Contribution of functional voltage-gated Na+ channel expression to cell behaviors involved in the metastatic cascade in rat prostate cancer: I. Lateral motility. J Cell Physiol. 2003;195:479–487. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Djamgoz MBA, Mycielska M, Madeja Z, Fraser SP, Korohoda W. Directional movement of rat prostate cancer cells in direct-current electric field: Involvement of voltage-gated Na+ channel activity. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2697–2705. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.14.2697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grimes JA, Fraser SP, Stephens GJ, Downing JE, Laniado ME, Foster CS, Abel PD, Djamgoz MB. Differential expression of voltage-activated Na+ currents in two prostatic tumour cell lines: Contribution to invasiveness in vitro. FEBS Lett. 1995;369:290–294. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00772-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laniado ME, Lalani EN, Fraser SP, Grimes JA, Bhangal G, Djamgoz MB, Abel PD. Expression and functional analysis of voltage-activated Na+ channels in human prostate cancer cell lines and their contribution to invasion in vitro. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:1213–1221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith P, Rhodes NP, Shortland AP, Fraser SP, Djamgoz MB, Ke Y, Foster CS. Sodium channel protein expression enhances the invasiveness of rat and human prostate cancer cells. FEBS Lett. 1998;423:19–24. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdul M, Hoosein N. Voltage-gated sodium ion channels in prostate cancer: Expression and activity. Anticancer Res. 2002;22:1727–1730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennett ES, Smith BA, Harper JM. Voltage-gated Na+ channels confer invasive properties on human prostate cancer cells. Pflugers Arch. 2004;447:908–914. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1205-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yildirim S, Altun S, Gumushan H, Patel A, Djamgoz MB. Voltage-gated sodium channel activity promotes prostate cancer metastasis in vivo. Cancer Lett. 2012;323:58–61. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cestèle S, Catterall WA. Molecular mechanisms of neurotoxin action on voltage-gated sodium channels. Biochimie. 2000;82:883–892. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9084(00)01174-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ritchie CK, Andrews LR, Thomas KG, Tindall DJ, Fitzpatrick LA. The effects of growth factors associated with osteoblasts on prostate carcinoma proliferation and chemotaxis: Implications for the development of metastatic disease. Endocrinology. 1997;138:1145–1150. doi: 10.1210/en.138.3.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bedir E, Kırmızıpekmez H, Sticher O, Caliş I. Triterpene saponins from the fruits of Hedera helix. Phytochemistry. 2000;53:905–909. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(99)00503-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demirci B, Goppel M, Demirci F, Franz G. HPLC profiling and quantification of active principles in leaves of Hedera helix L. Pharmazie. 2004;59:770–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Danloy S, QuetinLeclercq J, Coucke P, De Pauw-Gillet MC, Elias R, Balansard G, Angenot L, Bassleer R. Effects of alpha-hederin, a saponin extracted from Hedera helix, on cells cultured in vitro. Planta Med. 1994;60:45–49. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-959406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barthomeuf C, Debiton E, Mshvildadze V, Kemertelidze E, Balansard G. In vitro activity of hederacolchisid A1 compared with other saponins from Hedera colchica against proliferation of human carcinoma and melanoma cells. Planta Med. 2002;68:672–675. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-33807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cioacá C, Margineanu C, Cucu V. The saponins of Hedera helix with antibacterial activity. Pharmazie. 1978;33:609–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MoulinTraffort J, Favel A, Elias R, Regli P. Study of the action of α-hederin on the ultrastructure of Candida albicans. Mycoses. 1998;41:411–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1998.tb00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Julien J, Gasquet M, Maillard C, Balansard G, Timon-David P. Extracts of the ivy plant, Hedera helix, and their antihelminthic activity on liver flukes. Planta Med. 1985;3:205–208. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-969457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MajesterSavornin B, Elias R, DiazLanza AM, Balansard G, Gasquet M, Delmas F. Saponins of the ivy plant, Hedera helix, and their leishmanicidic activity. Planta Med. 1991;57:260–262. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Facino MR, Carini M, Stefani R, Aldini G, Saibene L. Anti-elastase and anti-hyaluronidase activities of saponins and sapogenins from Hedera helix, Aesculus hippocastanum, and Ruscus aculeatus: Factors contributing to their efficacy in the treatment of venous insufficiency. Arch Pharm (Weinheim) 1995;328:720–724. doi: 10.1002/ardp.19953281006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.deMedeiros JM, Macedo M, Contancia JP, Nguyen C, Cunningham G, Miles DH. Antithrombin activity of medicinal plants of the Azores. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;72:157–165. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(00)00226-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tennant TR, Kim H, Sokoloff M, Rinker-Schaeffer CW. The Dunning model. Prostate. 2000;43:295–302. doi: 10.1002/1097-0045(20000601)43:4<295::AID-PROS9>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bancroft JD, Stevens A, editors. Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques. 3rd edition. Churchill Livingstone; Edinburgh, UK: 1990. Proteins and nucleic acids; pp. 148–188. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fraser SP, Grimes JA, Djamgoz MB. Effects of voltage-gated ion channel modulators on rat protastic cancer cell proliferation: Comprarison of strongly and weakly metastic cell lines. Prostate. 2000;44:61–76. doi: 10.1002/1097-0045(20000615)44:1<61::AID-PROS9>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bun SS, Elias R, Baghdikian B, Ciccolini J, Ollivier E, Balansard G. Alpha-hederin potentiates 5-FU antitumor activity in human colon adenocarcinoma cells. Phytother Res. 2008;22:1299–1302. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park HJ, Kwon SH, Lee JH, Lee KH, Miyamoto KI, Lee KT. Kalopanaxsaponin A is a basic saponin structure for the anti-tumor activity of hederagenin monodesmosides. Planta Med. 2001;67:118–121. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-11516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swamy SM, Huat BT. Intracellular glutathione depletion and reactive oxygen species generation are important in alpha-hederin-induced apoptosis of P388 cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;245:127–139. doi: 10.1023/A:1022807207948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.StetlerStevenson WG, Aznavoorian S, Liotta LA. Tumor cell interactions with the extracellular matrix during invasion and metastasis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1993;9:541–573. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.002545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Isaacs JT, Isaacs WB, Feitz WF, Scheres J. Establishment and characterization of seven Dunning rat prostatic cancer cell lines and their use in developing methods for predicting metastatic abilities of prostatic cancers. Prostate. 1986;9:261–281. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990090306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]