Abstract

An unexpected [4+2] cycloaddition of aryl allenes and simple acrylate derivatives is reported. This process functions well with a variety of allenes and acrylates to generate bi- and tricyclic dihydronaphthalene derivatives through a nonconventional bond disconnection.

Keywords: Cycloaddition, Diels-Alder, Lewis-acid, Allenes, Acrylates

1. Introduction

Since its discovery in 1928, the Diels-Alder cycloaddition has enjoyed widespread application in chemical synthesis.1 Despite these numerous advances, this venerable reaction appears to be seemingly endless in regards to its versatility and scope. Outlined in this article is yet another twist on the Diels-Alder cycloaddition to included aryl allenes as competent dienes.

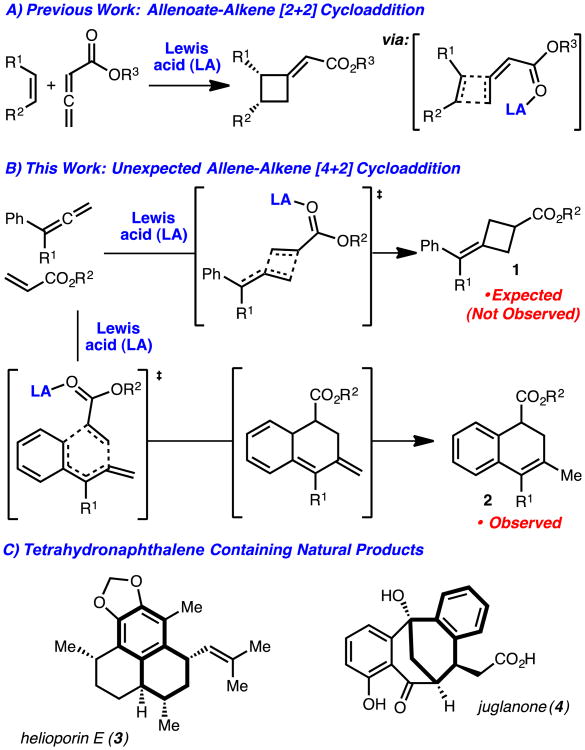

Our lab has taken an interest in the development of stereoselective [2+2] cycloadditions to access cyclobutanes.2 In the context of these efforts, we recently reported a catalytic enantioselective [2+2] cycloaddition of allenoates and alkenes (Scheme 1A).2a These reactions likely function by association of the chiral Lewis acid-catalyst with the allenoate and subsequent concerted asynchronous cycloaddition with the alkene.3 We became interested in development of a related process in which the allene would function as the nucleophilic component and operate by an ‘inverse demand’ cycloaddition to prepare methylene cyclobutanes such as 1 (Scheme 1B).4 These investigations, however, led to the unexpected discovery that aryl allenes participate in an unusual cycloaddition with acrylates to generate dihydronaphthalenes such as 2. The products generated by this method readily map onto the structures of several natural products, 3 and 4 are representative (Scheme 1C).5

Scheme 1.

Allene-based cycloadditions.

2. Background

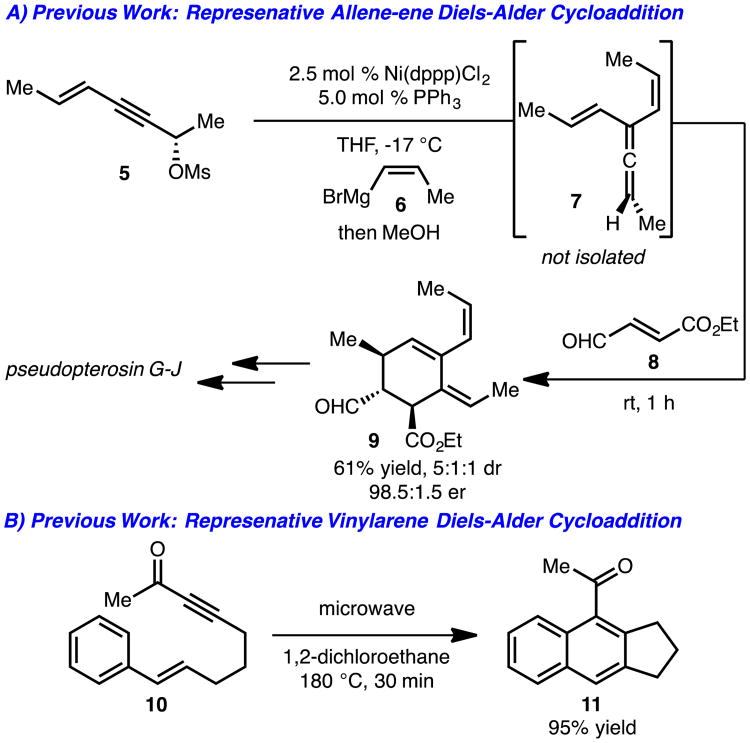

To place our unexpected results regarding Diels-Alder cycloaddition with arylallenes into context, two key pieces of background information must be discussed (Scheme 2). The first point is Diels-Alder cycloaddition with allene-enes. While not without precedent,6 the Sherburn lab has demonstrated an excellent example of an allene-ene Diels-Alder cycloaddition (7+8→9) enroute to the pseudopterosin class of natural products (Scheme 2A).7a This reaction occurs with high transfer of chirality and good diastereoselectivity. The second key literature precedent is that of Diels-Alder reactions involving styrene derivatives as the diene component.8,9 These reactions are generally limited to intramolecular variants, such as the example illustrated in Scheme 2B.8b

Scheme 2.

Relevant literature precedent.

3. Results and discussion

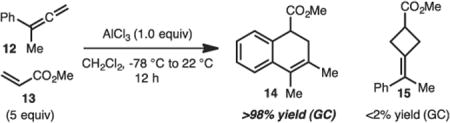

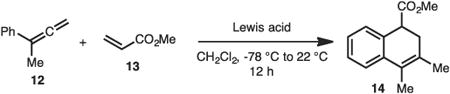

As noted previously, our initial investigations towards developing an inverse demand [2+2] cycloadditions with aryl allene 12 and methyl acrylate 13 led not to formation of the expected cyclobutane 15, but rather dihydronaphthalene derivative 14 in

|

(1) |

quantitative yield by GC analysis (Eq. 1).

With this unusual result in hand, the reaction parameters were evaluated (Table 1). While use of other strong Lewis-acids such as EtAlCl2, TiCl4 or BF3·OEt2 did not allow for formation of the desired product (Table 1, entries 2–6) catalytic amounts of AlCl3 did function well in the reaction (Table 1, entries 7–9). Finally, it was determined that the highest yields of product occurred when 3 equiv methyl acrylate (12) was used (Table 1, compare entries 8, 10–11).

Table 1. Optimization of reaction conditions.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Entry | Lewis acid | Lewis acid equiv | Acrylate equiv | Yield (%)a |

| 1 | AICI3 | 1.0 | 5 | >98 |

| 2 | EtAICI2 | 1.0 | 5 | <2 |

| 3 | TiCI4 | 1.0 | 5 | <2 |

| 4 | BF3·OEt2 | 1.0 | 5 | <2 |

| 5 | Bi(OTf)3 | 1.0 | 5 | <2 |

| 6 | Sc(OTf)3 | 1.0 | 5 | <2 |

| 7 | AICI3 | 0.5 | 5 | 84 |

| 8 | AICI3 | 0.3 | 5 | 87 |

| 9 | AICI3 | 0.1 | 5 | 73 |

| 10 | AICI3 | 0.3 | 3 | >98 |

| 11 | AICI3 | 0.3 | 1 | 78 |

Bold entry signifies the final optimized conditions.

Yield determined by GC analysis with a calibrated internal standard.

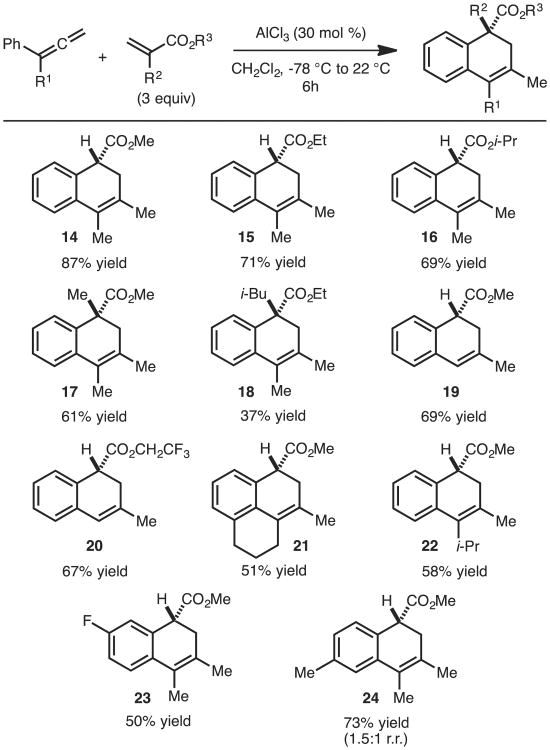

As illustrated in Scheme 3, 1,1-disubstituted allenes undergo cycloaddition with a wide range of acrylates. Products with quaternary centers can be achieved (17 and 18). The use of monosubstituted allenes (products 19 and 20) proceeds well in slightly lower yields, which can be attributed to decreased nucleophilicity of the allene nucleophile. Tricyclic cycloadduct 21 was achieved through use of the corresponding tetralone derived allenes and provided rapid access to the core structure of the pseudopterosin family of natural products such as helioporin E.5b Reaction of allenes with different electronic properties are tolerated (products 23 and 24); however, regioisomers are generated in the formation of 24.

Scheme 3.

Substrate scope.

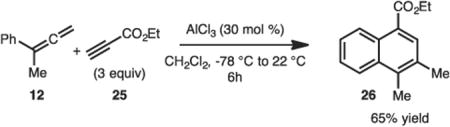

It was also demonstrated that cycloadditions with ethyl propiolate (25) led to formation of the naphthalene derivative 26 in 65% yield. This method represents an unusual strategy to access substituted naphthalenes.

|

(2) |

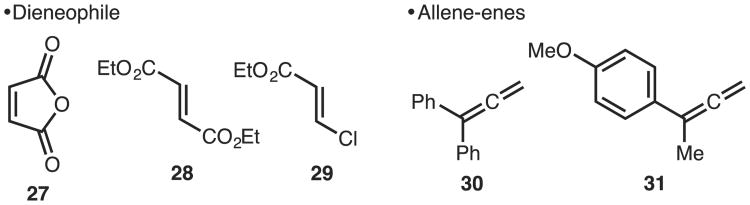

Illustrated in Chart 1 are the known limitations of the method. One of the more unusual aspects of this study is the dieneophiles that do not undergo reaction. Reactions with quintessential dieneophiles maleic anhydride (27) and dimethylfumarate (28) do not lead to product formation, but rather polymerization of the allene was observed. Surprisingly, even a β-substituent as small as chloride (e.g., 29) was not tolerated in the reaction. In addition, allene-enes bearing additional aromatic rings (e.g., 30) or electron donating groups (e.g., 31) led to polymerization prior to productive [4+2] cycloaddition.

Chart 1.

Limitations of method.

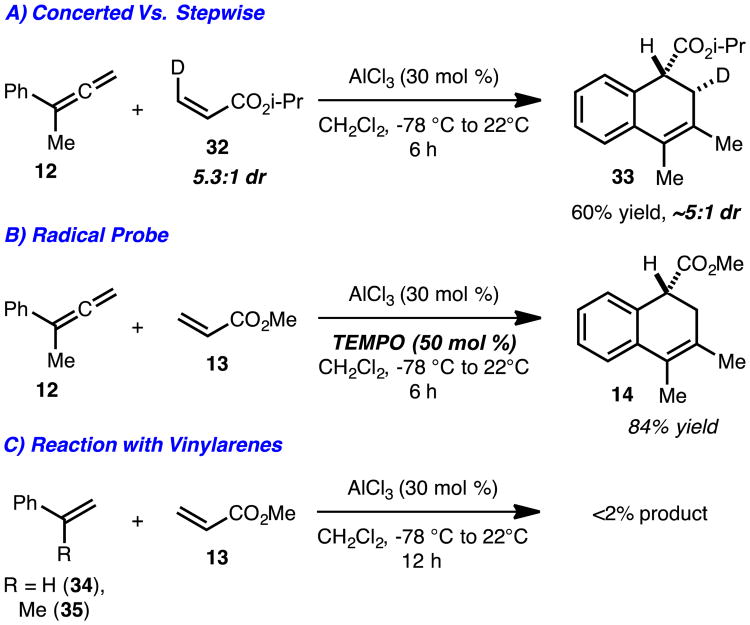

Preliminary experiments were carried out to probe the mechanism of this process. In particular, isotopically labeled acrylate 32 was used to investigate the concerted versus stepwise nature of the reactions (Scheme 4A). Since the overall process was stereospecific, a concerted yet likely asynchronous cycloaddition is proposed. However, at this time we cannot exclude a stepwise pathway with the formation of a short lived intermediate. In addition, radical intermediates are unlikely, as the addition of TEMPO (50 mol %) had no effect of the reaction yield (Scheme 4B). Finally, the reaction is specific to aryl allenes as vinyl arenes 34 and 35 did not undergo Diels-Alder cycloaddition (Scheme 4C) under the same conditions.

Scheme 4.

Mechanistic investigations.

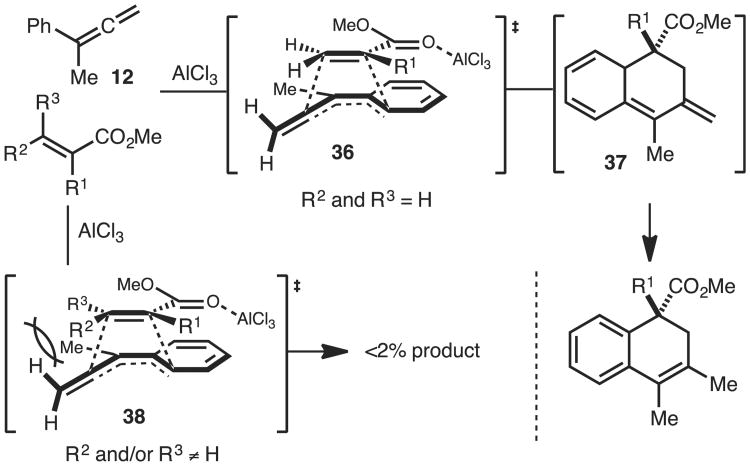

On the basis of the experiments outlined in Scheme 4 a mechanism as well as a putative transition state is proposed (36) (Scheme 5). The reaction is likely a concerted asynchronous [4+2] cycloaddition. The acrylate may approach the aryl allene according to the ‘endo rule’ (see below for further discussion). This reaction necessarily proceeds via intermediate 37. Attempts to observe this intermediate by 1H NMR spectroscopy were unsuccessful and thus we conclude that its half-life must be exceedingly short. Nevertheless, it is still likely that a [4+2] cycloadditions occurs based on the product outcome and stereospecific nature of the reaction (Scheme 4A). The transition state models can also provide a rationale why β-substituted dieneophiles fail to undergo reaction. Due to the perpendicular π-bond, the terminal hydrogen atoms of the allene projects towards the incoming dieneophile and likely causes an adverse steric interaction as illustrated in Scheme 5 (38). This likely reduces the rate of cycloaddition allowing polymerization of the allene to occur. This steric interaction is absent in typical Diels-Alder cycloadditions involving dienes. Finally, the unique reactivity of aryl allenes relative to vinyl arenes is likely due to increased stabilization of developing positive change in the T.S. from the terminal double bond.

Scheme 5.

Proposed mechanism and transition state.

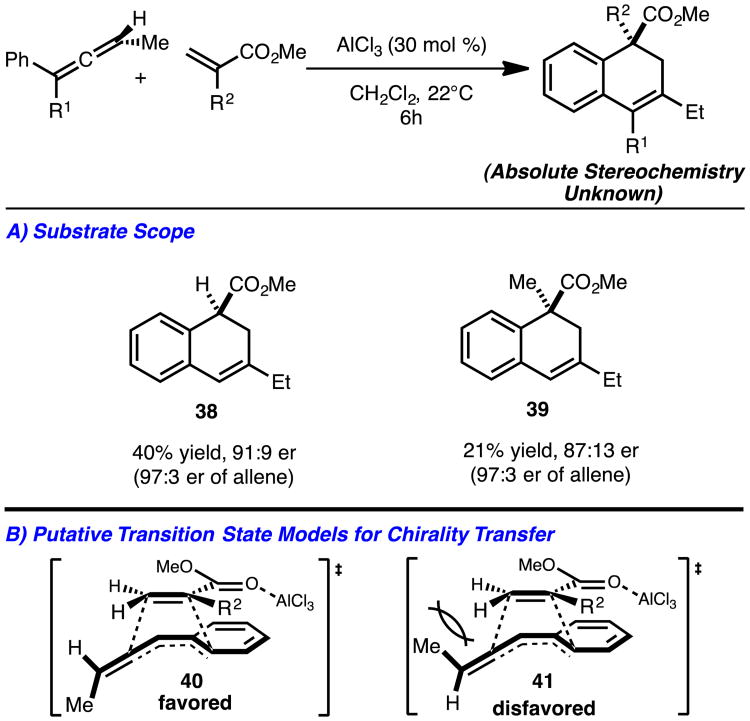

Since the reactions are likely concerted and asynchronous, chirality transfer reactions were then investigated with chiral γ-substitute allenes.10 As illustrated in Scheme 6A modest transfer of chirality and yield was observed in all cases investigated (products 38–39). The low yields with these allenes are likely due to a slower rate of cycloaddition, which allows for competing polymerization of the allene to take place. At the present time, the absolute stereochemistry of the cycloadduct is unknown which precludes a full discussion of potential transition state models for chirality transfer.11 However, illustrated in Scheme 6 are putative transition state models 40 and 41 that convey logical pathways for chirality transfer. It is proposed that the acrylate unit approaches distal to the γ-Me-substituent of the allene and the ester is position over the aryl ring in accordance with traditional [4+2] orbital considerations (i.e., ‘endo-rule’) (Scheme 6B).12

Scheme 6.

Chirality transfer reactions.

4. Summary

In conclusion, a unusual Diels-Alder cycloaddition of aryl allenes and acrylates is reported. This method provides access to dihydronaphthalene derivatives. In some cases, chirality transfer is possible. Clear limitation are present but can likely be overcome with additional investigations.

5. Experimental section

1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded at room temperature using a Varian I400 (1H NMR at 400 MHz, 13C NMR at 100 MHz, 19F at 375 MHz), Varian VXR400 (1H NMR at 400 MHz, 13C NMR at 100 MHz), Varian I500 (1H NMR at 500 MHz and 13C NMR at 125 MHz) and Varian I600 (1H NMR at 600 MHz and 13C NMR at 150 MHz). Chemical shifts are reported in ppm from tetramethylsilane with the solvent resonance as the internal standard (1H NMR CDCl3: δ 7.26 ppm 13C NMR CDCl3: δ 77.2 ppm). Data is reported as follows: chemical shift, multiplicity (s=singlet, d=doublet, t=triplet, q=quartet, p=pentet, br=broad, m=multiplet), coupling constants (Hz) and integration. Infrared spectra (IR) were obtained on an Avatar 360-FTIR E.S.P. on a NaCl salt plate and recorded in wavenumbers (cm-1). Bands are characterized as broad (br), strong (s), medium (m), and weak (w). Melting points were obtained on a Thomas Hoover capillary melting point apparatus without correction. High Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS) analysis was obtained using Electron Impact Ionization (EI), Chemical Ionization (CI) or Electrospray Ionization (ESI) and reported as m/z (relative intensity). GC–MS data was acquired using an Agilent 6890N Gas Chromatograph and 5973 Inert Mass Selective Detector. ESI was acquired using a Waters/Micromass LCT Classic (ESI-TOF). Unless otherwise noted, all reactions have been carried out with distilled and degassed solvents under an atmosphere of dry N2 in oven- (135 °C) and flame-dried glassware with standard vacuum-line techniques. Dichloromethane, diethyl ether and tetrahydrofuran were purified under a positive pressure of dry argon by passage through two columns of activated alumina. Toluene was purified under a positive pressure of dry argon by passage through columns of activated alumina and Q5 (Grubbs apparatus). All work-up and purification procedures were carried out with reagent grade solvents (purchased from Sigma–Aldrich) in air. Standard column chromatography techniques using ZEOprep 60/40–63 μm silica gel were used for purification.

5.1. Synthesis of aryl allenes

5.1.1. Propa-1,2-dien-1-ylbenzene

Prepared according to literature procedure.13

5.1.2. Buta-2,3-dien-2-ylbenzene

Prepared according to literature procedure.10

5.1.3. Buta-1,2-dien-1-ylbenzene

Prepared according to literature procedure.14

5.1.4. 1-(Buta-2,3-dien-2-yl)-4-fluorobenzene

Prepared according to literature procedure.15

5.1.5. 1-Vinylidene-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalene

Prepared according to literature procedure.16

5.1.6. (4-Methylpenta-1,2-dien-3-yl)benzene

Prepared according to literature procedure.13

5.1.7. (R)-Buta-1,2-dien-1-ylbenzene

Prepared according to literature procedure.10a

5.2. Synthesis of acrylate components

5.2.1. Isopropyl propiolate

Propiolic acid (2 mL, 32.0 mmol, 1 equiv) was added to a 50 mL flame dried round bottom flask equipped with a reflux condenser. iPrOH (20 mL, 1.70 M) was added followed by BF3OEt2 (7.90 mL, 64.0 mmol, 2 equiv) and the apparatus was heated to reflux (90 °C) for 3 h. Upon completion, the reaction was cooled to room temperature and diluted with H2O (20 mL). The aqueous phase was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3×10 mL) and the combined organics washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated. Purification by column chromatography (10% Et2O:Pentane) provides 1.80 g (50% yield) of the title compound as a clear colorless liquid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.11 (hept, J=6.2 Hz, 1H), 2.84 (s, 1H), 1.30 (d, J=6.3 Hz, 5H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 152.40, 75.29, 74.09, 70.61, 21.73.

5.2.2. Isopropyl (Z)-acrylate-3-d (32)

Procedure adapted from known literature procedure.17 D2O (20 mL, 0.700 M) was added to a 50 mL RB flask at room temperature under an atmosphere of air. Isopropyl propiolate (1.67 g, 14.9 mmol, 1.00 equiv) was added followed by anhydrous K2CO3 (210.0 mg, 1.50 mmol, 0.085 equiv), and the mixture was allowed to stir for 24 h at room temperature. Upon completion, the aqueous phase was extracted with Et2O (3×2 mL) and carefully concentrated to yield completely deuterated propiolate which was carried forward without purification. To a flame dried RB flask containing Et2O (150 mL, 0.100 M) was added Lindlar catalyst (5% w/w, 300 mg, 0.150 mmol, 0.010 equiv) followed by quinoline (265 mL, 2.24 mmol, 0.15 equiv) and the atmosphere was purged with H2. Crude 2H-isopropyl propiolate (1.69 g, 14.9 mmol, 1 equiv) was added in one portion and the reaction stirred at room temperature for 1.25 h under an atmosphere of H2. The reaction mixture was filtered through Celite and carefully concentrated. The crude brown residue was then purified by column (2% Et2O:Pentane) to yield 500 mg (30% yield) of the title compound as a clear colorless liquid (5.3:1 cis:trans). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.37 (dd, J=17.0, 6.2 Hz, minor isomer), 6.16–6.00 (m, 1H), 5.77 (d, J=10.4 Hz, 1H), 5.22–4.98 (m, 1H), 1.29 (dd, J=11.5, 6.3 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 165.93, 130.37–129.51 (m), 129.17, 70.62, 67.99, 24.45–18.62 (m).

5.3. General procedure for the [4+2] cycloaddition of aryl allenes and acrylates. 14 is representative

5.3.1. Methyl 3,4-dimethyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene-1-carboxylate (14)

AlCl3 (8.00 mg, 0.200 mmol, 0.300 equiv) was weighed out into a flame dried screw cap vial in a nitrogen filled glovebox, capped with septum and removed. CH2Cl2 (1.00 mL, 0.200 M) was added and the resulting cloudy solution was cooled to −78 °C for five minutes. Methacrylate (54.0 μL, 0.600 mmol, 3.00 equiv) was added followed quickly by buta-2,3-dien-2-ylbenzene (27.0 μL, 0.200 mmol, 1.00 equiv). The septum was quickly replaced with a screw cap and removed from the cold bath. The reaction was allowed to stir at room temperature for four hours. The reaction was then quenched with Et3N (200 μL), diluted with HCl (1 M, 2 mL) and extracted with CH2Cl2 (3×1 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over MgSO4, filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure. Purification of the resulting residue by flash chromatography (2% EtOAc:Hexanes) yields 37.6 mg (87% yield) of pure title compound as a clear colorless oil. IR (film): 2989 (w), 2949 (w), 1736 (s), 1488 (w), 1434 (w), 1275 (s), 1260 (s), 1205 (m) cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.31–7.20 (m, 2H), 7.20–7.11 (m, 2H), 3.70 (t, J=6.3 Hz, 1H), 3.67 (s, 3H), 2.68 (dd, J=16.5, 5.8 Hz, 1H), 2.53–2.43 (m, 1H), 2.01 (dt, J=2.3, 1.2 Hz, 3H), 1.96–1.90 (m, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 174.3, 136.8, 131.9, 130.5, 128.0, 127.7, 125.9, 124.9, 123.0, 52.2, 44.3, 33.0, 20.5, 14.3. HRMS (EI): Calcd for C14H16O2 (M)+: 216.1145, Found: 216.1142.

5.3.2. Ethyl 3,4-dimethyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene-1-carboxylate (15)

Utilizing ethyl acrylate and buta-2,3-dien-2-ylbenzene. Purification of the resulting residue by flash chromatography (2% EtOAc:Hexanes) yields 32.8 mg (71% yield) of pure title compound as a clear colorless oil. Clear colorless oil. IR (film): 2989 (w), 2949 (w), 1736 (s), 1488 (w), 1434 (w), 1275 (s), 1260 (s), 1205 (m) cm−1. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.31–7.20 (m, 3H), 7.20–7.08 (m, 1H), 4.21–4.05 (m, 2H), 3.68 (t, J=6.5 Hz, 1H), 2.66 (dd, J=16.3, 6.3 Hz, 1H), 2.46 (dd, J=16.5, 6.5 Hz, 1H), 2.01 (dt, J=2.3, 1.2 Hz, 3H), 1.93 (s, 3H), 1.22 (t, J=7.1 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.9, 136.9, 132.1, 130.4, 127.8, 127.6, 125.9, 124.9, 123.0, 60.8, 44.4, 33.1, 20.5, 14.3, 14.3. HRMS (EI): Calcd for C15H18O2 (M)+: 230.1301, Found: 230.1300.

5.3.3. Isopropyl 3,4-dimethyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene-1-carboxylate (16)

Utilizing isopropyl acrylate and buta-2,3-dien-2-ylbenzene. Purification of the resulting residue by flash chromatography (2% EtOAc:Hexanes) yields 33.5 mg (69% yield) of pure title compound as a clear colorless oil. Clear colorless oil. IR (film): 2989 (w), 2949 (w), 1724 (s), 1106 (s) cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.28–7.23 (m, 2H), 7.18–7.10 (m, 2H), 5.01 (hept, J=6.0 Hz, 1H), 3.65 (t, J=6.7 Hz, 1H), 2.64 (dd, J=16.4, 6.8 Hz, 1H), 2.45 (dd, J=16.5, 6.5 Hz, 1H), 2.01 (s, 3H), 1.93 (s, 3H), 1.24–1.15 (m, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.5, 136.8, 132.3, 130.3, 127.5, 127.5, 125.9, 124.9, 123.0, 68.1, 44.6, 33.1, 21.9, 20.5, 14.5. HRMS (ESI): Calcd for C16H20O2Na (M+Na)+: 267.1361, Found: 267.1356.

5.3.4. Methyl 1,3,4-trimethyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene-1-carboxylate (17)

Utilizing α-methyl methacrylate and buta-2,3-dien-2-ylbenzene. Purification of the resulting residue by flash chromatography (2% EtOAc:Hexanes) yields 28.1 mg (61% yield) of pure title compound as a clear colorless oil. IR (film): 3033 (w), 2952 (m), 1716 (s), 1674 (m), 1339 (m), 1246 (s), 1182 (s) cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.32–7.14 (m, 4H), 3.64 (d, J=1.1 Hz, 3H), 2.83 (d, J=16.1 Hz, 1H), 2.19 (d, J=16.3 Hz, 1H), 2.01 (d, J=1.7 Hz, 3H), 1.95–1.88 (m, 3H), 1.52 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 177.2, 137.3, 136.4, 130.6, 127.3, 126.2, 125.3, 124.6, 123.2, 52.4, 46.5, 41.5, 23.9, 20.6, 14.3. HRMS (EI): Calcd for C15H18O2 (M)+: 230.1301, Found: 230.1308.

5.3.5. Ethyl 1-isobutyl-3,4-dimethyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene-1-carboxylate (18)

Utilizing α-isobutyryl methacrylate and buta-2,3-dien-2-ylbenzene. Purification of the resulting residue by flash chromatography (2% EtOAc:Hexanes) yields 21.1 mg (37% yield) of pure title compound as a pale yellow oil. IR (film): 3022 (w), 2934 (s), 1731 (s), 1446 (m), 1195 (m) cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.35–7.08 (m, 4H), 4.20 (q, J=7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.87 (d, J=16.3 Hz, 1H), 2.25 (d, J=16.2 Hz, 1H), 2.18 (dd, J=7.1, 1.2 Hz, 2H), 2.04–1.98 (m, 2H), 1.95 (s, 2H), 1.80 (dt, J=13.6, 6.8 Hz, 1H), 1.30 (t, J=7.1 Hz, 3H), 0.92–0.82 (m, 8H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 172.4, 149.8, 140.5, 137.9, 136.3, 129.3, 125.8, 124.1, 121.3, 52.5, 45.9, 42.6, 41.8, 23.5, 22.8, 19.8, 12.3. HRMS (EI): Calcd for C18H24O2 (M)+: 272.1776, Found: 272.1781.

5.3.6. Methyl 3-methyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene-1-carboxylate (19)

Utilizing methacrylate and propa-1,2-dien-1-ylbenzene. Purification of the resulting residue by flash chromatography (2% EtOAc:Hexanes) yields 27.9 mg (69% yield) of pure title compound as a clear colorless oil. IR (film): 2951 (w), 1734 (w), 1458 (w), 1434 (w), 1266 (m), 1202 (m) cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.23–7.09 (m, 3H), 7.00 (dd, J=7.4, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 6.21 (s, 1H), 3.84–3.77 (m, 1H), 3.68 (s, 3H), 2.69 (dd, J=16.8, 5.7 Hz, 1H), 2.54–2.44 (m, 1H), 1.94 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 174.1, 136.4, 134.5, 130.4, 128.0, 127.6, 126.2, 125.5, 122.2, 52.1, 44.0, 31.3, 23.3. HRMS (EI): Calcd for C13H14O2 (M)+: 202.0988, Found: 202.0994.

5.3.7. 2,2,2-Trifluoroethyl 3-methyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene-1-carboxylate (20)

Utilizing 2,2,2-trifluoroethylacrylate and propa-1,2-dien-1-ylbenzene. Purification of the resulting residue by flash chromatography (2% EtOAc:Hexanes) yields 36.3 mg (67% yield) of pure title compound as a clear colorless oil. IR (film): 2972 (w), 1755 (s), 1489 (w), 1410 (w), 1277 (s), 1168 (s) cm−1. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.25–7.10 (m, 3H), 7.01 (dd, J=7.5, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 6.22 (t, J=1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.51 (dq, J=12.6, 8.4 Hz, 1H), 4.39 (dq, J=12.7, 8.4 Hz, 1H), 3.89 (dd, J=7.2, 4.9 Hz, 1H), 2.67 (dd, J=16.9, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 2.60–2.50 (m, 1H), 1.94 (d, J=1.5 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 172.2, 136.0, 134.7, 129.4, 128.3, 128.3, 126.8, 126.4, 125.9, 123.0 (q, J=277.2 Hz), 122.5, 60.7 (q, J=36.5 Hz), 43.9, 31.26, 23.4. HRMS (EI): Calcd for C14H13O2F3 (M)+: 270.0862, Found: 270.0856.

5.3.8. Methyl 3-methyl-2,4,5,6-tetrahydro-1H-phenalene-1-carboxylate (21)

Utilizing methacrylate and 1-vinylidene-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalene. Purification of the resulting residue by flash chromatography (2% EtOAc:Hexanes) yields 24.7 mg (51%yield) of pure title compound as a clear colorless oil. IR (film): 2928 (w), 1732 (m), 1276 (s), 1261 (s). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3)δ 7.05–6.96 (m, 3H), 3.67 (s, 4H), 2.75 (tt, J=11.6, 5.6 Hz, 2H), 2.67 (dd, J=16.5, 6.2 Hz, 1H), 2.48 (td, J=8.9, 7.9, 4.7 Hz, 3H), 1.87 (t, J=1.1 Hz, 3H), 1.79 (p, J=6.2 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 174.6, 135.4, 132.0, 131.4, 128.1, 127.6, 126.1, 125.9, 125.6, 52.2, 44.2, 32.8, 30.8, 26.7, 22.9, 19.6. HRMS (EI): Calcd for C16H18O2 (M)+: 274.1277, Found: 242.1279.

5.3.9. Methyl 4-isopropyl-3-methyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene-1-carboxylate (22)

Utilizing methacrylate and (4-methylpenta-1,2-dien-3-yl)benzene. Purification of the resulting residue by flash chromatography (2% EtOAc:Hexanes) yields 26.8 mg (58% yield) of pure title compound as a clear colorless oil. IR (film): 2989 (w), 2949 (w), 1724 (s), 1106 (s) cm−1. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.41 (dd, J=7.9, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.25–7.21 (m, 1H), 7.17–7.09 (m, 2H), 3.66 (s, 3H), 3.60 (t, J=5.8 Hz, 1H), 3.19 (hept, J=7.2 Hz, 1H), 2.60 (dd, J=16.2, 5.7 Hz, 1H), 2.45–2.36 (m, 1H), 1.97 (s, 3H), 1.32 (d, J=7.3 Hz, 3H), 1.27 (d, J=7.2 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 174.9, 136.7, 136.0, 134.2, 131.7, 128.6, 127.7, 126.2, 124.7, 52.7, 45.4, 34.7, 29.7, 22.4, 21.9, 21.4. HRMS (ESI): Calcd for C16H20O2 (M)+: 244.1458, Found: 244.1451.

5.3.10. Methyl 7-fluoro-3,4-dimethyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene-1-carboxylate (23)

Utilizing methacrylate and 1-(buta-2,3-dien-2-yl)-4-fluorobenzene. Purification of the resulting residue by flash chromatography (2% EtOAc:Hexanes) yields 23.6 mg (50% yield) of pure title compound as a clear colorless oil. IR (film): 2989 (w), 1736 (s), 11494 (m), 1275 (s), 1261 (s), cm−1. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.19 (dd, J=8.6, 5.6 Hz, 1H), 6.93 (td, J=8.6, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 6.90–6.86 (m, 1H), 3.69–3.64 (m, 4H), 2.66 (dd, J=16.5, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 2.46 (dd, J=16.5, 6.6 Hz, 1H), 1.99 (dt, J=2.2, 1.2 Hz, 3H), 1.92 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.7, 161.1 (d, J=244.9 Hz), 134.1 (d, J=7.6 Hz), 133.1 (d, J=3.1 Hz), 129.6 (d, J=2.2 Hz), 124.4 (d, J=8.1 Hz), 124.2, 115.1 (d, J=22.3 Hz), 114.0 (d, J=20.7 Hz), 52.3, 44.2 (d, J=1.7 Hz), 32.7, 20.4, 14.4. HRMS (EI): Calcd for C14H15O2F1 (M)+: 234.1051, Found: 234.1051.

5.3.11. Methyl 3,4,6-trimethyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene-1-carboxylate (24)

Utilizing methacrylate and 1-(buta-2,3-dien-2-yl)-3-methylbenzene. Purification of the resulting residue by flash chromatography (2% EtOAc:Hexanes) yields 33.7 mg (73% yield) of pure title compound as an inseparable mixture of regioisomers (1.5:1 rr). IR (film): 2989 (w), 1736 (s), 11494 (m), 1275 (s), 1261 (s), cm−1. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3). Mixture of isomers: δ 7.22–7.10 (m, 2H), 7.10–6.99 (m, 3H), 6.99–6.93 (m, 1H), 3.82 (dd, J=6.7, 1.8 Hz, 1H) minor isomer, 3.71–3.62 (m, 4H) major isomer, 3.59 (s, 3H) minor isomer, 2.73–2.61 (m, 2H), 2.55–2.42 (m, 2H), 2.34 (s, 6H), 2.05–1.97 (m, 6H), 1.96–1.84 (m, 6H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) Mixture of Isomers: δ 174.4, 173.8, 137.0, 136.9, 136.55, 135.6, 130.3, 130.1, 128.8, 128.1, 127.7, 127.1, 126.4, 125.2, 124.7, 123.8, 120.9, 52.0, 52.2, 43.8, 39.7, 33.0, 32.7, 21.5, 20.4, 19.7, 14.4, 14.2. HRMS (EI): Calcd for C15H18O2 (M)+: 230.1301, Found: 230.1337.

5.3.12. Ethyl 3,4-dimethyl-1-naphthoate (26)

Utilizing ethyl-propiolate and buta-2,3-dien-2-ylbenzene. Purification of the resulting residue by flash chromatography (2% EtOAc:Hexanes) yields 29.9 mg (65% yield) of pure title compound as a pale yellow oil. IR (film): 2989 (w), 2949 (w), 1724 (s), 1106 (s) cm−1. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.96–8.83 (m, 1H), 8.12–8.07 (m, 1H), 8.01 (s, 1H), 7.57–7.52 (m, 2H), 4.47 (q, J=7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.65 (s, 3H), 2.52 (s, 3H), 1.47 (t, J=7.1 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.8, 137.1, 133.2, 133.0, 132.1, 130.1, 126.2 (2C), 126.0, 125.1, 124.0, 60.9, 20.7, 15.3, 14.5. HRMS (EI): Calcd for C15H16O2 (M)+: 228.1145, Found: 228.1140.

5.3.13. Isopropyl 3,4-dimethyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene-1-carboxylate-2-d (33)

Utilizing isopropyl (Z)-acrylate-3-D and buta-2,3-dien-2-ylbenzene. Purification of the resulting residue by flash chromatography (2% EtOAc:Hexanes) yields 29.4 mg (60% yield, ∼5:1 dr) of pure title compound as a clear colorless oil. IR (film): 2928 (w), 1732 (m), 1276 (s), 1261 (s). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.31–7.20 (m, 2H), 7.20–7.10 (m, 2H), 5.09–4.92 (m, 1H), 3.64 (d, J=6.5 Hz, 1H), 2.66–2.60 (m, 0H), 2.43 (d, J=6.4 Hz, 1H), 2.01 (s, 3H), 1.93 (s, 3H), 1.21 (d J=6.4 Hz, 3H), 1.18 (d, J=6.2 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.3, 136.7, 132.2, 130.1, 127.5, 127.4, 125.7, 124.8, 122.8, 67.9, 44.4, 32.9–32.3 (m), 21.8, 20.3, 14.1. HRMS (EI): Calcd for : 245.1521, Found: 245.1521.

5.3.14. Methyl-3-ethyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene-1-carboxylate (38)

Utilizing methacrylate and (R)-buta-1,2-dien-1-ylbenzene.Purification of the resulting residue by flash chromatography (2%EtOAc:Hexanes) yields 18.2 mg (42% yield) of pure title compound as a clear colorless oil. IR (film): 2951 (w), 2350 (s), 2341 (s), 1734 (m), 1434 (w), 1266 (w) cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.24–7.09 (m, 3H), 7.03 (dd, J=7.4, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 6.20 (s, 1H), 3.80 (t, J=6.5 Hz, 1H), 3.67 (s, 3H), 2.76–2.65 (m, 1H), 2.54–2.43 (m, 1H), 2.24 (q, J=7.4 Hz, 2H), 1.13 (t, J=7.4 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3)δ 174.1, 141.9, 134.5, 130.8, 128.0, 127.6, 126.2, 125.7, 120.5, 52.0, 44.1, 30.0, 11.8. HRMS (EI): Calcd for C14H16O2 (M)+: 216.1150, Found:216.1154. The enantiomeric purity was established by HPLC analysis using a chiral column (Chiralpak IA, 22 °C, 0.5 mL/min, 99:1 Hexanes:Isopropanol, 220 nm, tminor=13.879 min, tmajor=15.880 min).

5.3.15. Methyl-3-ethyl-1-methyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene-1-carboxylate (39)

Utilizing α-methyl methacrylate and (R)-buta-1,2-dien-1-ylbenzene. Purification of the resulting residue by flash chromatography (2% EtOAc:Hexanes) yields 9.7 mg (21% yield) of pure title compound as a clear colorless oil. IR (film): 3024 (w), 2931 (s), 1734 (s), 1452 (m), 1198 (m) cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.22–7.09 (m, 3H), 7.09–6.94 (m, 1H), 6.19 (s, 1H), 3.66 (s, 3H), 2.89 (d, J=16.5 Hz, 1H), 2.32–2.10 (m, 3H), 1.53 (d, J=5.2 Hz, 3H), 1.12 (t, J=7.5 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 177.1, 141.8, 136.6, 134.1, 127.5, 126.7, 126.2, 125.6, 120.6, 52.4, 47.0, 38.8, 30.2, 24.1, 11.9. HRMS (EI): Calcd for C15H18O2 (M)+: 230.1301, Found: 230.1335. The enantiomeric purity was established The enantiomeric purity was established by HPLC analysis using a chiral column (Chiralpak IA, 22 °C, 0.3 mL/min, 99:1 Hexanes:Isopropanol, 220 nm, tminor=15.216 min, tmajor=16.372 min).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Indiana University and the National Institutes of Health (R01GM110131-01) for generous support of this work. MKB is a 2015 Sloan Research Fellow.

Footnotes

Supplementary data: Supplementary data (1H NMR and 13C NMR) associated with this article can be found in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tet.2016.02.028.

References and notes

- 1.For recent reviews see: Nicolaou KC, Snyder SA, Montagnon T, Vassilikogiannakis G. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2002;41:1668. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020517)41:10<1668::aid-anie1668>3.0.co;2-z.Heravi MM, Vavsari VF. RSC Adv. 2015;5:50890.Jiang X, Wang R. Chem Rev. 2013;113:5515. doi: 10.1021/cr300436a.

- 2.(a) Conner ML, Xu Y, Brown MK. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:3482. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b00563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rasik CM, Brown MK. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2014;53:14522. doi: 10.1002/anie.201408055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Rasik CM, Hong YJ, Tantillo DJ, Brown MK. Org Lett. 2014;16:5168. doi: 10.1021/ol5025184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Rasik C, Brown M. Synlett. 2014:760. [Google Scholar]; (e) Rasik CM, Brown MK. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:1673. doi: 10.1021/ja3103007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Snider BB, Ron E. J Org Chem. 1986;51:3643. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hoffmann H, Ismail ZM, Weber A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981;22:1953. [Google Scholar]; (c) Snider BB, Spindell DK. J Org Chem. 1980;45:5017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Modern Allene Chemistry. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2004. [Google Scholar]; (b) Okamura WH, Curtin ML. Synlett. 1990:1. [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Liu L, Li W, Sasaki T, Asada Y, Koike KJ. Nat Med. 2010;64:496. doi: 10.1007/s11418-010-0435-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lazerwith SE, Johnson TW, Corey E. J Org Lett. 2000;2:2389. doi: 10.1021/ol006192k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Looks SA, Fenical W, Jacobs RS, Clardy J. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1986;83:6238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.17.6238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Looks SA, Fenical W, Matsumoto GK, Clardy J. J Org Chem. 1986;51:5140. [Google Scholar]; (e) Tanaka JI, Ogawa N, Liang J, Higa T, Gravalos DG. Tetrahedron. 1993;49:811. [Google Scholar]

- 6.For an early example, see: Bertrand M, Grimaldi J, Waegell B. Chem Commun. 1968:1141.

- 7.(a) Newton CG, Drew SL, Lawrence AL, Willis AC, Paddon-Row MN, Sherburn MS. Nat Chem. 2015;7:82. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cergol KM, Newton CG, Lawrence AL, Willis AC, Paddon-Row MN, Sherburn MS. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2011;50:10425. doi: 10.1002/anie.201105541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.For representative examples, see: Bhojgude SS, Bhunia A, Gonnade RG, Biju AT. Org Lett. 2014;16:676. doi: 10.1021/ol4033094.Kocsis LS, Benedetti E, Brummond KM. Org Lett. 2012;14:4430. doi: 10.1021/ol301938z.Sun S, Turchi IJ, Xu D, Murray WV. J Org Chem. 2000;65:2555. doi: 10.1021/jo991956z.Chackalamannil S, Doller D, Clasby M, Xia Y, Eagen K, Lin Y, Tsai HA, McPhail AT. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:4043.Gacs-Baitz E, Minuti L, Taticchi A. Tetrahedron. 1994;50:10359. (f) For a review, see: Wagner-Jauregg T. Synthesis. 1980:769.

- 9.(a) Pedrosa R, Andrés C, Nieto J. J Org Chem. 2002;67:782. doi: 10.1021/jo010746v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ciganek E. In Organic Reactions. John Wiley & Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prepared according to the following protocols: Myers AG, Zheng B. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:4492.Uehling MR, Marionni ST, Lalic G. Org Lett. 2012;14:362. doi: 10.1021/ol2031119.

- 11.Despite numerous attempts, we were unable to obtain a single crystal suitable for X-ray crystallography of a derivative of 38 and 39 for absolute structure confirmation.

- 12.Houk KN, Strozier RW. J Am Chem Soc. 1973;95:4094. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsubara T, Takahashi K, Ishihara J, Hatakeyama S. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2014;53:757. doi: 10.1002/anie.201307835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rigby J, Laurent S, Kamal Z, Heeg J. Org Lett. 2008;10:5609. doi: 10.1021/ol802401a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ngai M, Skucas E, Krische MJ. Org Lett. 2008;10:2705. doi: 10.1021/ol800836v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jang H, Jung B, Hoveyda AH. Org Lett. 2014;16:4658. doi: 10.1021/ol5022417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Procedure adapted from: Ollis WD, Sutherland IO, Thebtaranonth Y. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 1981;1:1981.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.