Summary

Background

Translational research is the direct application of basic and applied research to patient care. It is estimated that there are at least 2,000 different skin diseases, thus there are considerable challenges in seeking to undertake research on each of these disorders.

Objective

This eDelphi exercise was conducted in order to generate a list of translational dermatology research questions which are regarded as a priority for further investigations.

Results

During the first phase of the eDelphi, 228 research questions were generated by an expert panel which included clinical academic dermatologists, clinical dermatologists, non-clinical scientists, dermatology trainees and representatives from patient support groups. Following completion of the second and third phases, 40 questions on inflammatory skin disease, 20 questions on structural skin disorders / genodermatoses, 37 questions on skin cancer and 8 miscellaneous questions were designated as priority translational dermatology research questions (PRQs). In addition to PRQs on a variety of disease areas (including multiple PRQs on psoriasis, eczema, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and melanoma), there were a number of cross-cutting themes which identified a need to investigate mechanisms / pathogenesis of disease and the necessity to improve treatments for patients with skin disease.

Conclusion

It is predicted that this list of PRQs will help to provide a strategic direction for translational dermatology research in the UK and that addressing this list of questions will ultimately provide clinical benefit for substantial numbers of subjects with skin disorders.

Introduction

Skin disease is extremely common and it is estimated that at least 2,000 different dermatological disorders exist1. In the UK, approximately 54% of the population are affected by dermatological conditions each year2. These skin conditions vary in presentation, prevalence, and impact. For example, 2% of the population suffer from psoriasis, while up to 32% of children have atopic eczema and nearly all teenagers develop acne vulgaris3–5. In addition, skin cancer is the most common cancer in the UK, as well as globally, despite evidence of under-reporting of skin cancer in national databases6,7. As might be expected, skin disease can impact significantly on patients’ and their relatives’ quality of life, with a recent study on global burden of disease indicating that skin conditions are the fourth leading cause of nonfatal disease burden worldwide8–10.

While there is a clear need to develop laboratory-based research to better understand the underlying causes of these skin conditions, to date there has been a lack of a strategic focus within dermatological research that aims to ‘translate’ new findings and discoveries into new drugs, diagnostic aids, devices and treatment options for patients, and to make sure that these new principles actually impact on patient care and public health. Indeed, while the rate of basic research ensures that the scientific knowledge base is constantly increasing, there is a substantial lag with respect to the rate at which this is translated into improved health and wellbeing. Translational research seeks to bridge this gap, applying basic science concepts to solve ‘real world’ problems; as such, translational research takes a patient-centred or patient-oriented approach and is in-keeping with recent developments in health policy11. In addition to this lag between basic research and the clinical implementation of findings, the ability to undertake translational research on the full range of skin disorders is limited at the present time. This limitation raises important issues regarding how best to improve patient care for skin disorders.

Given the large number of heterogeneous dermatological conditions and limited resources with which to fund translational research in dermatology, the UK Translational Research Network in Dermatology (UK TREND) was established by the British Association of Dermatologists (BAD) in order to “support, facilitate and further develop internationally-leading, translational research in skin biology and skin disease across the UK for the direct benefit of patient care”12. As part of this mandate, a translational research prioritisation exercise was undertaken, with the goal of identifying and prioritising important research questions for translational advances that can be achieved in order to provide practical steps that will help to expedite the basic to translational step within the research pipeline.

The Delphi approach is a method for structuring a group communication process to enable a group of individuals, as a whole, to deal with a complex problem13,14. This technique, first reported in 1963, has been employed for over half a century to gain consensus opinion in multiple situations, ranging from views on transformative drugs developed by the pharmaceutical industry to forecasting population migration15–17. Likewise, the Delphi has been used to assist in the planning of education, including the dermatological content of the undergraduate medical curriculum18–20. More recently, the Delphi has been utilised to prioritise research in various medical specialties, including occupational medicine, respiratory medicine, and mental health21–23.

In the current study, members of UK TREND conducted an electronic Delphi (e-Delphi) exercise to help prioritise translational research in dermatology. The results highlight many translational research questions which are important, practical and feasible to address at the current time, and from which the results are ultimately likely to lead to substantial benefits for patients with skin diseases.

Materials and methods

UK TREND was established by the BAD as a company limited by guarantee (not for profit organisation). The e-Delphi project was directed by the steering group of UK TREND which has full academic freedom.

Participants in the survey

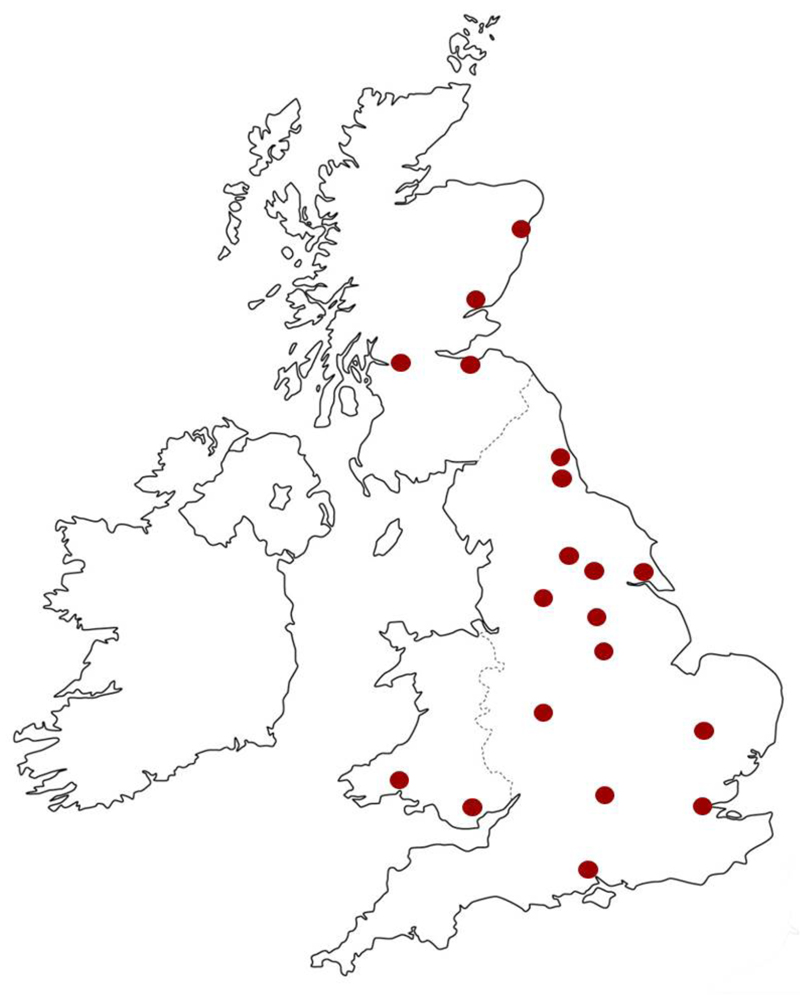

Participants were eligible for inclusion if they were stakeholders in the translation lifecycle of dermatological research. This included researchers, clinicians and knowledge users (patients and policy makers). Individuals were identified by the steering group of UK TREND and invited to participate in the Delphi expert panel because they had extensive experience in clinical dermatology and translational research (17 senior clinical academic dermatologists), clinical dermatology (4 NHS consultant dermatologists), or in translational research in dermatology (3 senior non-clinical scientists). Patients with skin disease were also invited to participate (3 representatives from broad-based patient support groups dealing with all types of skin disease), as well as representatives from primary care (1 clinical academic general practitioner who also sought input from the Dermatology Specialist Interest Group, Society for Academic Primary Care), two senior members of the British Association of Dermatologists (i.e. members of the BAD Executive Committee) and clinical trainees (2 trainees in dermatology). As the Delphi process is an exploratory technique, and not intended to generate statistically representative samples nor identify differences between groups, sample size calculations to determine the number of expert panel members were not performed. Given the geographic dispersion of the expertise within the UK, invitations were made via email. This approach achieved an expert panel with representation that covered a wide geographical area within the UK (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Geographical distribution of participants on the eDelphi expert panel.

Surveys

As per the Delphi structure, the translational dermatological research eDelphi was conducted in three phases. In the first phase participants provided open-text responses detailing important research questions. This was followed by consolidation of responses that were subsequently rated for importance. Following the initial ratings, a second round of rating was undertaken in order to achieve a final list of “priority translational dermatology research questions” (PRQs).

During phase 1, participants were asked to provide up to 15 questions about translational research topics covering the breadth of dermatology across the following four categories; (i) inflammatory skin disease, (ii) structural skin disorders / genodermatoses, (iii) skin cancer and (iv) miscellaneous. Participants were encouraged to request input from colleagues within their departments in order to ensure that there was broad input into the generation of the questions. The definition of translational research provided to participants was that used by UK TREND, i.e. “the direct application of basic and applied research to patient care; this may encompass diagnostics, biomarkers, disease mechanisms and the development of new therapies that then impact on clinical practice”12. To assist with the production of questions, participants were informed that questions could deal with disease processes such as aetiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis (including biomarkers), treatment, and burden of disease, but it was highlighted that questions on any aspect of translational dermatology research were encouraged.

In the second phase, a consolidated list of research questions produced in the first phase, maintained under the same four headings, was circulated via Survey Monkey® to all participants on the expert panel. Participants were asked to score each question in each section on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 to 5, where 5 indicated a very important research question and 1 indicated a least important question. Again, participants were encouraged to complete the scoring of questions with input from members of their department. In addition, participants were informed that the scores would subsequently be collated and that they would each be provided, during phase 3, with the average score and with their own score for each question, with the ability to modify their score at that stage if they wished.

In the third phase, and in order to facilitate the consensus process and minimise participant burden, participants who took part in phase 2 were provided the top questions (mean score ≥ 3.0) identified in each of the four categories and asked to review the mean and median scores for each of these higher ranking questions together with their own score. Participants were informed that they could modify their score, if they wished to do so, using the same 5-point Likert-style scale as the previous round. During phase 3, these higher scoring questions were left in the same original order in each of the categories so as to minimise any bias when the questions were recirculated to participants (i.e. ranking by mean or median score was not provided).

Data Analysis

Following phase 1, duplicate or closely duplicated questions were received in some cases, therefore these were reviewed and combined by members of the eDelphi study group (EH, SJB, ST, KS, SML, NJR) in a manner to preserve all components of the original questions. In certain cases, where statements rather than questions were received, the participants who had provided these statements were asked to convert them into questions. When questions potentially related to more than one category, their designated category was that deemed to be the primary focus as determined by the members of the eDelphi study group. As such, although the research questions were listed in one of the four categories, the groupings were not mutually exclusive and PRQs relevant to some skin disorders may have appeared under different categories.

Quantitative data were summarised using the mean and median score for each question. In order to achieve consensus on a manageable number of research priorities, a pre-defined criterion of consensus was established. It was considered that if at least 70% of participants scored a question as ≥ 3.0 during the third phase, this would be deemed to be indicative that consensus had been achieved that the question should be regarded as being of high priority by the majority of the panel. Questions meeting this criterion were designated as “priority translational dermatology research questions (PRQs)”.

Results

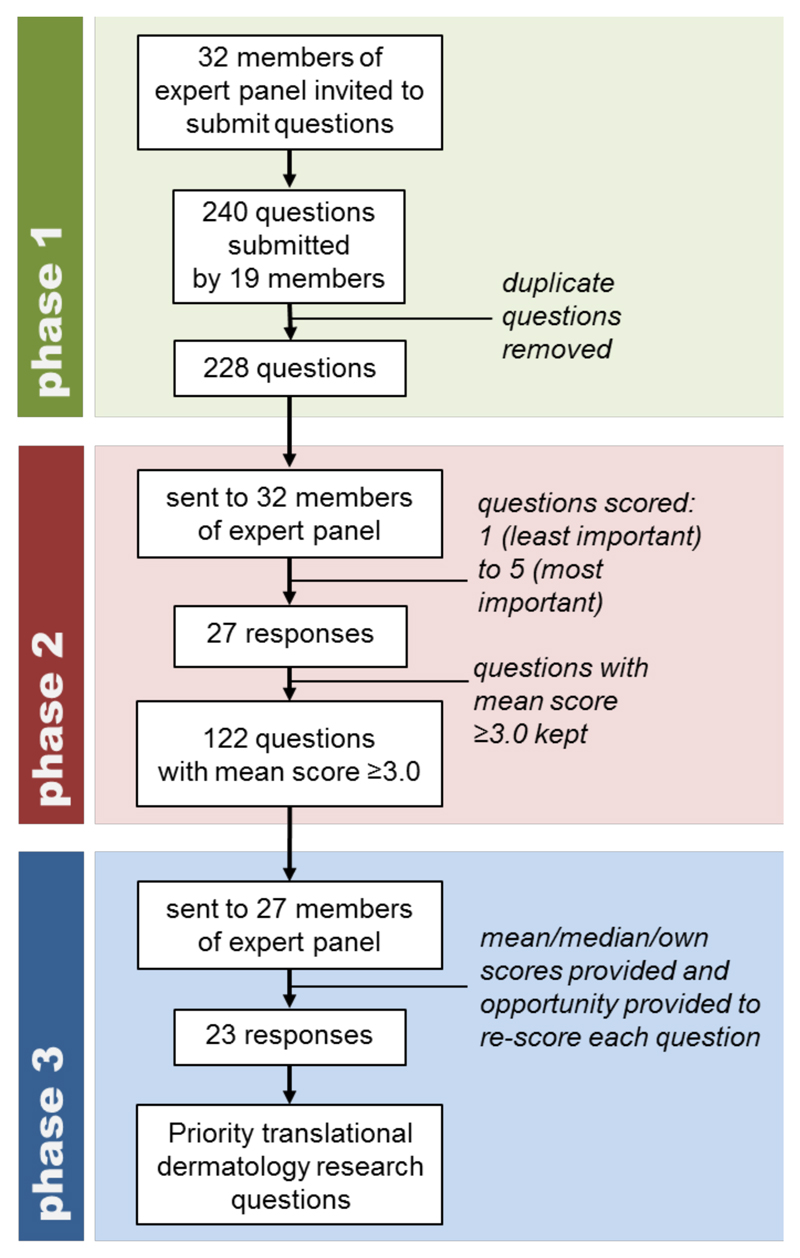

During phase 1, a total of 240 questions were provided by 19 members of the expert panel (Fig. 2). Following removal of duplicate questions, a consolidated list of 228 research questions remained. These included 68 on inflammatory skin disease, 44 on structural skin disorders / genodermatoses, 68 on skin cancer and 48 under the miscellaneous category. The 228 questions were sent to the 32 members of the expert panel during phase 2 and completed scores for all questions were returned by 27 members of the expert panel (response rate 84.4%). Mean and median scores were calculated for all questions, with 122 questions attaining a mean score of ≥ 3.0; this comprised 47 inflammatory skin disease, 22 structural skin disorders / genodermatoses, 41 skin cancer and 12 miscellaneous category questions.

Fig 2.

Flow diagram illustrating the process used to conduct the eDelphi on translational dermatology research priorities.

Phase 3 was completed by 23 participants (response rate 23/27 = 85.2%), with a total of 105 questions achieving consensus (which we defined as 70% of respondents scoring the question ≥ 3.0). These comprised 40 questions on inflammatory skin disease, 20 on structural skin disorders / genodermatoses, 37 on skin cancer and 8 miscellaneous questions, i.e. a total of 105 PRQs (supplementary table 1).

In the inflammatory skin disease component, PRQs on inflammatory skin diseases in general as well as on eczema/dermatitis (including atopic eczema) and psoriasis were common, but those on other specific disorders included hidradenitis suppuritiva, lichen planus, cutaneous lupus (erythematosus), toxic epidermal necrolysis and drug allergy (table1 and supplementary table 1).

Table 1.

Top 10 priority translational dermatology research questions on inflammatory skin disease (listed in alphabetical order).

| Can we develop a reliable test for identifying the culprit drug in drug allergy? |

| Can we identify novel systemic treatments for adult eczema? |

| Can we predict (from genotype and/or phenotype) which patients will respond to which second/third line treatments for eczema and which patients will not respond? |

| Can we stratify systemic/biological treatments on the basis of genotype and/or phenotype and predict treatment outcome in psoriasis? |

| Do biological therapies for major inflammatory skin diseases have long-term side effects? |

| Does restoration of barrier function in atopic dermatitis prevent immune activation, disease persistence/progression, and/or the atopic march? |

| Does therapeutic increase in filaggrin expression associate with improvement in atopic disease? |

| How does the environment, the microbiome and epigenetics influence inflammatory skin disease? |

| What genetic factors other than filaggrin are important in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis? |

| What mechanism underlies children growing out of eczema? |

Many of the PRQs in the structural skin disorders / genodermatoses category were related to the underlying genetics of common and rare skin disorders or to the development of genetics-based technological approaches to treating a variety of skin diseases (table 2 and supplementary table 1). Indeed, treatments emerged strongly as cross-cutting themes in each of the four categories, as did mechanisms / pathogenesis of disease (which can inform development of novel therapies), and these mechanism / treatment themes were also noted in the PRQs on ulceration and wound healing which were present in the structural skin disorders / genodermatoses category.

Table 2.

Top 10 priority translational dermatology research questions on structural skin disorders / genodermatoses (listed in alphabetical order).

| Can the understanding of genetic mechanisms be used to develop novel therapeutics for skin disease? |

| Can topical formulation deliver siRNA and small molecules to genetically impaired skin? |

| Can we improve our mechanistic understanding for acute and chronic wound healing? |

| Does early effective skin care prevent or postpone leg ulceration in chronic venous insufficiency? |

| How can we best correct the effects of genetic alterations which lead to disease (e.g. treatment of epidermolysis bullosa, correction of filaggrin deficiency)? |

| Is there a single most efficient and safest method for delivery of siRNA gene therapy to the skin independent of the condition? |

| What angiogenic factors in leg ulcer healing can be exploited therapeutically? |

| What are the mechanisms involved in impaired wound healing that can be used to improve treatment- diabetic ulcers, venous ulcers? |

| What insight do novel genes in the genodermatoses give regarding the molecular mechanisms of more common skin disease? |

| Does bone marrow transplantation for genetic skin diseases such as RDEB give long term persistence of graft cells in the skin and structural repair without immune response? |

In the skin cancer component, PRQs tended to focus more on SCC and melanoma, however, basal cell carcinoma, cutaneous lymphoma, dermatofibromasarcoma protuberans and Merkel cell carcinoma also featured (table 3 and supplementary table 1).

Table 3.

Top 10 priority translational dermatology research questions on skin cancer (listed in alphabetical order).

| Can the oncogenome of cutaneous SCC be used to predict response to novel targeted therapies? |

| Can we identify biomarkers of melanoma recurrence / tumour load to assist in the early detection of metastases and selecting patients for interventions such as vemurafenib and ipilimumab? |

| Can we identify novel systemic treatments for SCC? |

| Can we identify stratified therapies for melanoma? |

| Does the treatment of precancerous skin lesions i.e. actinic keratoses lead to a reduction in the development of squamous cell carcinoma? |

| What are the critical determinants of the tumour microenvironment that drive aggressive cutaneous SCC? |

| What are the genetic/molecular drivers for cutaneous SCC? |

| What are the predictive biomarkers of melanoma relapse? |

| What are the specific biomarkers associated with progress of dysplastic nevi to primary melanoma to metastatic melanoma in the same individual? |

| What factors drive the survival of melanoma cells that are apparently dormant and that lead to metastases, in some cases, decades after excision of the primary lesion? |

Some of the PRQs in the miscellaneous section dealt with inflammatory skin disease, genetic aspect of disease or skin cancer, but research questions on vitiligo and itch were also considered as priorities by the participants (supplementary table 1).

Discussion

The focus of this eDelphi was on the prioritisation of translational dermatology research questions. In the case of dermatology, there are challenges in prioritising research while, at the same time, avoiding discrimination between common and rare diseases. It is also recognised that prioritising research is likely to influence not only the focus of current investigations but also the future direction of research, as well as having the potential to inform future funding directions. Whereas not all participants provided questions, all members of the expert panel were invited to score the questions during phase 2, thus ensuring that the scoring was broadly representative of the panel membership. Although the total number of questions submitted by the participants may appear limited in comparison with the total number of skin disorders that exist, there were several cross-cutting themes (e.g. genetics, molecular, immune, therapeutic, biomarkers) in the original questions supplied by members of the expert panel and in the final list of PRQs. Indeed, noticeable themes that ran through each of the pre-determined categories was the potential for treatment, and for translational research to build upon information obtained from the molecular and cellular pathogenesis of skin disease (e.g. genomic, immunological, etc.) in order to generate biomarkers and develop new therapies. In addition, there was a strong emphasis on personalised medicine (also referred to as precision or stratified medicine)24,25 related to patient outcome in terms of treatment efficacy or risk of disease complications. Recent research to classify scleroderma patients on the basis of gene expression profiles is consistent with this stratified medicine approach26.

Interestingly, many PRQs have relevance to other clinical specialties, for example psoriasis is a multisystem disease and translational advances in this skin disorder are potentially applicable to psoriatic arthritis and other arthritides, including rheumatoid arthritis. Similarly, progress in the translational aspects of atopic eczema may impact clinically on the atopic march, asthma and hay fever as well as understanding how environmental allergens can modify innate / acquired immune function at various epithelial surfaces. Likewise, translational advances in skin cancer may provide insight into genetic and immunological factors which determine clinical outcome from cancer, and from precancerous lesions, in general. Moreover, the relevance of the PRQs to other disciplines and the benefits of interactions with scientists in other disciplines highlight the advantages of a multidisciplinary approach in addressing these PRQs.

Within each of the pre-determined categories, important trends were notable. In the inflammatory skin disease group, PRQs on eczema and psoriasis were common, which may reflect the research interests of invited and contributing participants. The interest in psoriasis is despite the fact that significant translational improvements have already been made in psoriasis over the past 15 years27, with the PRQs demonstrating that there remains a need for further progress, and a view that progress is feasible, in the bench-to-bedside impact of research on this disorder. That eczema features prominently may relate to the limited treatment options, high prevalence and significant morbidity of atopic eczema and other forms of dermatitis. The frequent PRQs on this condition may also be influenced by the fact that dermatologists have recently seen gains in the understanding and treatment of psoriasis and thus wish to see similar advances in eczematous disorders. These PRQs on eczema also complement the prioritized treatment uncertainties reported by Batchelor et al. as part of an eczema priority setting partnership28. Furthermore, recent progress in understanding the genetic basis of the skin barrier defect as an underlying mechanism in atopic eczema has stimulated interest in the translation of this for development of therapy and clinical trial stratification29,30. The structural skin disorders / genodermatoses grouping of PRQs exhibit an important underlying theme which is applicable to each of the four categories, namely the relevance to all skin diseases of understanding the impact of genetic alterations on disease phenotype and the development of novel therapeutic genetic / cellular approaches to improve patient care. Indeed, some early promising results have recently been seen with the use of genetic and cellular-based therapies for certain monogenic skin diseases, forming a strong translational foundation upon which to build future advances31,32.

In the skin cancer category, PRQs on melanoma and SCC were most common, which may relate to the increasing burden of disease in terms of mortality and long-term clinical follow-up for higher risk cases with these tumours33,34. There is also recognition that, whereas surgery remains an important therapeutic option for many skin cancers, there is a need for alternative and additional treatments for precancerous lesions and more aggressive cancers respectively35,36. While recent advances have been observed with novel pharmacological therapies for metastatic melanoma37, these are generally not curative; in addition, limited progress has been made in the treatment of SCC over the past few decades38,39. Not surprisingly, the need for a stratified medicine approach to skin cancer, similar to the strategy for treatment of inflammatory skin diseases, was noted. In contrast to skin cancers, inflammatory skin diseases and structural skin disorders / genodermatoses, it is difficult to categorise many other skin diseases under these terms. For example, although genetic and immunological factors are involved in the development of vitiligo40, this disease is not generally viewed as a classical inflammatory or genetic skin disorder. Thus, the use of the miscellaneous category for a number of the questions in the eDelphi was helpful because it ensured that PRQs could be generated on any type of skin disease and that all dermatological disorders were covered by the prioritisation process.

We are aware that any attempt to conduct a detailed analysis of the results of this eDelphi is fraught with difficulty. In addition, the findings of this exercise must be considered within the limitations of the eDelphi approach. Given the limited number, and select group of participants, there is the potential for bias due to the research interests of the participants and/or their departments. To mitigate this we purposively sought expertise and input from a wide range of individuals and from across a wide geographical area and we actively encouraged participants to seek input from colleagues at each centre / institution. Although we did not specifically ask the panel members to report on this issue, we are aware from verbal feedback that a number of the panel members did seek input from several colleagues (including medical and nursing colleagues) in their department. The exercise is also open to the vagaries of current areas of interest that are in vogue. Indeed, as translational research progress is made on the above PRQs, it is probable that translational research priorities will change and it is recognised that this eDelphi reports on current PRQs and that updating the eDelphi exercise in the future will ensure that translational dermatology research remains strategically focussed in the long-term.

The results of this eDelphi are likely to impact on several areas relevant to improving patient care. Firstly, it is recognised that the existence of at least 2,000 different dermatological disorders makes it difficult for research funding organisations to determine priorities for research funding in this discipline, thus it is anticipated that the list of PRQs will assist in this process. Secondly, the eDelphi can be employed to facilitate the development of strategic translational dermatology research clusters within the UK (for example on eczema, SCC, etc.) akin to the BADBIR cluster on psoriasis which has been instrumental to improving many aspects of patient care41. Thirdly, the direction of translational research provided by the PRQs will impact on research training in dermatology, both for those wishing to train as clinical academics and for those who plan to work primarily in the NHS in future years. Fourthly, it is probable that the PRQs will be useful to the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries in their role of developing new therapeutics and biomarkers for skin disease.

In conclusion, the results of this eDelphi highlight a number of translational research questions which are considered priority areas, because they have the potential to bridge the gap between basic laboratory research and enhancing patient care, thus improving the health and wellbeing of individuals with skin disease.

Supplementary material

Supplementary table 1 containing full list of questions with 70% respondents ranking as ≥ 3.0 (i.e. priority translational dermatology research questions).

What’s already known about this topic?

Translational research aims to advance patient care by bridging the gap between laboratory-based science and clinical dermatology, leading to greater understanding of disease, the identification of biomarkers and development of novel therapies.

There is a need for a co-ordinated approach to translational research in dermatology in order to make the best use of limited resources.

The Delphi (or eDelphi; electronic Delphi) technique is used to help develop consensus opinion on a topic, and is a useful approach to assist with prioritisation of research questions in translational dermatology.

What does this study add?

This eDelphi has prioritised a number of translational dermatology research questions which are considered by professional and lay experts to be relevant, important and urgent priorities.

It is anticipated that the knowledge generated through pursuing these research questions will lead to significant benefits for individuals affected by skin disease.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Kasia Kmieckowiak and Catherine Thums at the British Association of Dermatologists for administrative support, to Stephen Holgate in the University of Southampton for helpful advice, and to the British Association of Dermatologists for financial support underpinning the administrative component of UK TREND.

Funding sources

The administrative support for the UK Translational Research Network in Dermatology (UK TREND) is provided by the British Association of Dermatologists (BAD). S.J.B. holds a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Clinical Fellowship (WT086398MA), S.L. is in receipt of a National Institute for Health Research Clinician Scientist Fellowship, S.G.N is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Postdoctoral Fellowship (122403), and K.S. is a Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Fellow (WT100119/Z/12/Z).

List of abbreviations

- BAD

British Association of Dermatologists

- eDelphi

electronic Delphi technique

- PRQs

priority translational dermatology research questions

- UK TREND

United Kingdom Translational Research Network in Dermatology

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

E.H., S.L., K.S. and N.J.R. undertake translational dermatology research which is funded by a variety of sources, including research councils, charitable trusts and industry. S.J.B. conducts translational dermatology research funded by charitable trusts.

References

- 1.Burns DA, Cox NH. Chapter 1: Introduction and historical bibliography. In: Burns T, Breathnack S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rooks textbook of Dermatology. 8th edition. Wiley-Blackwell; Oxford, UK: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schofield JK, Grindlay D, Williams HC. Skin conditions in the UK : a health care needs assessment. Centre of Evidence Based Dermatology, University of Nottingham; UK: 2009. Metro Commercial Printing Ltd, Hertfordshire, UK. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nestle FO, Kaplan DH, Barker J. Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:496–509. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wadonda-Kabondo N, Sterne JAC, Golding J, et al. A prospective study of the prevalence and incidence of atopic dermatitis in children aged 0 - 42 months. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:1023–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2003.05605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhate K, Williams HC. Epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:474–85. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. http://publications.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/statsreports/dtincmortrates.html.

- 7.Lucas R, McMichael T, Smith W, Armstrong B. Solar ultraviolet radiation: Global burden of disease from solar ultraviolet radiation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. Environmental burden of disease series, No. 13. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basra MK, Fenech R, Gatt RM, et al. The Dermatology Life Quality Index 1994-2007: a comprehensive review of validation data and clinical results. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:997–1035. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basra MK, Sue-Ho R, Finlay AY. The Family Dermatology Life Quality Index: measuring the secondary impact of skin disease. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:528–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1527–34. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. http://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/gov/research-dev-strategy/

- 12. http://www.uktrend.org/home/4587271444.

- 13.Linstone HA, Turoff M, editors. The Delphi method: Techniques and Applications. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company Inc; Reading, Massachusetts: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delphi: somewhere between Scylla and Charybdis? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E4284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415425111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalkey N, Helmer O. An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Management Sci. 1963;9:458–67. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kesselheim AS, Avorn J. The most transformative drugs of the past 25 years: a survey of physicians. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2013;12:425–31. doi: 10.1038/nrd3977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wisniowski A, Bijak J, Shang HL. Forecasting Scottish migration in the context of 2014 constitutional change debate. Popul Space Place. 2014;20:455–64. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harder A, Place NT, Scheer SD. Towards a competency–based extension education curriculum: a Delphi study. J Agri Edu. 2010;51:44–52. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Porta M, Mas-Machuca M, Martinez-Costa C, et al. A Delphi study on technology Enhanced Learning (TEL) applied on Computer Science (CS) skills. Int J Educ Dev Inform Comm Tech. 2012;8:46–70. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clayton R, Perera R, Burge S. Defining the dermatological content of the undergraduate medical curriculum: a modified Delphi study. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:137–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrington JM. Research priorities in occupational medicine: a survey of United Kingdom medical opinion by the Delphi technique. Occup Environ Med. 1994;51:289–94. doi: 10.1136/oem.51.5.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheikh A, Major P, Holgate ST. Developing consensus on national respiratory research priorities: key findings from the UK Respiratory Research Collaborative's e-Delphi exercise. Respir Med. 2008;102:1089–92. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins PY, Patel V, Joestl SS, et al. Grand challenges in global mental health. Nature. 2011;475:27–30. doi: 10.1038/475027a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicholls SG, Wilson BJ, Castle D, et al. Personalized medicine and genome-based treatments: why personalized medicine ≠ individualized treatments. Clin Ethics. 2014;9:135–44. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khoury MJ, Gwinn ML, Glasgow RE, Kramer BS. A population approach to precision medicine. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42:639–45. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pendergrass SA, Lemaire R, Francis IP, et al. Intrinsic gene expression subsets of diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis are stable in serial skin biopsies. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1363–73. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmitt J, Rosumeck S, Thomaschewski G, et al. Efficacy and safety of systemic treatments for moderate-to-severe psoriasis: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:274–303. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Batchelor JM, Ridd MJ, Clarke T, et al. The Eczema Priority Setting Partnership: a collaboration between patients, carers, clinicians and researchers to identify and prioritize important research questions for the treatment of eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:577–82. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leung DY, Guttman-Yassky E. Deciphering the complexities of atopic dermatitis: shifting paradigms in treatment approaches. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:769–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stout TE, McFarland T, Mitchell JC, et al. Recombinant filaggrin is internalized and processed to correct filaggrin deficiency. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:423–9. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uitto J, Christiano AM, McLean WH, McGrath JA. Novel molecular therapies for heritable skin disorders. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:820–8. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wagner JE, Ishida-Yamamoto A, McGrath JA, et al. Bone marrow transplantation for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:629–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brantsch KD, Meisner C, Schönfisch B, et al. Analysis of risk factors determining prognosis of cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma: a prospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:713–20. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marsden JR, Newton-Bishop JA, Burrows L, et al. Revised U.K. guidelines for the management of cutaneous melanoma 2010. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:238–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bath-Hextall FJ, Matin RN, Wilkinson D, Leonardi-Bee J. Interventions for cutaneous Bowen's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6:CD007281. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007281.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sullivan RJ, Flaherty KT. Major therapeutic developments and current challenges in advanced melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:36–44. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Griewank KG, Scolyer RA, Thompson JF, et al. Genetic alterations and personalized medicine in melanoma: progress and future prospects. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:djt435. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lansbury L, Bath-Hextall F, Perkins W, et al. Interventions for non-metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: systematic review and pooled analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 2013;347:f6153. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wollina U. Update of cetuximab for non-melanoma skin cancer. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2014;14:271–6. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2013.876406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spritz RA. Six decades of vitiligo genetics: genome-wide studies provide insights into autoimmune pathogenesis. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:268–73. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burden AD, Warren RB, Kleyn CE, et al. The British Association of Dermatologists' Biologic Interventions Register (BADBIR): design, methodology and objectives. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:545–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.