Abstract

OBJECTIVES

In the absence of a reliable biomarker, clinical decisions for a functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorder like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) depend on asking patients to appraise and communicate their health status. Self-ratings of health (SRH) have proven a powerful and consistent predictor of health outcomes, but little is known about how they relate to those relevant to IBS (e.g., quality of life (QOL), IBS symptom severity). This study examined what psychosocial factors, if any, predict SRH among a cohort of more severe IBS patients.

METHODS

Subjects included 234 Rome III-positive IBS patients (mean age = 41 years, female = 78%) without comorbid organic GI disease. Subjects were administered a test battery that included the IBS Symptom Severity Scale, Screening for Somatoform Symptoms, IBS Medical Comorbidity Inventory, SF-12 Vitality Scale, Perceived Stress Scale, Beck Depression Inventory, Trait Anxiety Inventory, and Negative Interactions Scale.

RESULTS

Partial correlations identified somatization, depression, fatigue, stress, anxiety, and medical comorbidities as variables with the strongest correlations with SRH (r values = 0.36–0.41, P values < 0.05). IBS symptom severity was weakly associated with SRH (r = 0.18, P < 0.05). The final regression model explained 41.3% of the variance in SRH scores (F = 8.49, P < 0.001) with significant predictors including fatigue, medical comorbidities, somatization, and negative social interactions.

CONCLUSIONS

SRH are associated with psychological (anxiety, stress, depression), social (negative interactions), and extraintestinal somatic factors (fatigue, somatization, medical comorbidities). The severity of IBS symptoms appears to have a relatively modest role in how IBS patients describe their health in general.

INTRODUCTION

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic, painful, often disabling gastrointestinal (GI) disorder characterized by abdominal pain associated with an alteration in bowel habits (diarrhea, constipation, or both in an alternating pattern). Lacking a reliable biomarker, IBS symptoms are best understood from the patient’s perspective and most directly (1,2) accessed through self-report methods such as questionnaires and face-to-face interviews.

Because of their subjective nature, self-report data have been derided as having limited validity and meaning (3). The notion that self-report data are inherently flawed has been challenged by research that highlights the empirical and clinical value of appraisals that patients make about their health and well-being. Empirically, a single measure of health that asks respondents to rate their overall health as excellent, good, fair, or poor (or some variant thereof) is a consistent predictor of subsequent health outcomes (e.g., mortality, morbidly, disability, health care use, etc.) even after controlling for present disease or dysfunction (4). For these reasons, many major studies (such as the National Health Interview Study) include global self-evaluations as an efficient, affordable, and informative way of gauging health status. Clinically, patients’ judgments of their health are the basis by which decisions are made to seek, modify, and suspend treatment. Further, patient self-reports of health, like other patient-reported outcomes, have the potential to improve clinical outcomes (5–7) whose importance will, with the passage of the Affordable Care Act, increase in a value-driven health-care environment.

Despite their established value, relatively little (8) is known about how patients with GI disorders in general and IBS in particular make judgments about their health. This is a significant void in the scientific literature given the burden that GI diseases inflict (9) and the predictive value of self-ratings of health (SRH). Studies that have measured how individuals generate health appraisals indicate that global health status is a multidimensional construct that involves judgments across multiple domains (4,10,11). In addition to specific physical health problems (e.g., limitations in physical functioning, coexisting medical conditions, symptom complaints), individuals use psychosocial factors as referents to describe their health. Particularly influential factors can include patients’ mental well-being, illness behaviors (physician and hospital utilization), and aspects of their social environment. Whether this pattern of data extends to IBS patients is unknown. What research has been conducted comes mostly from studies that have included SRH as a component measure for gauging quality of life (QOL) impairment due to IBS (12,13). IBS patients’ SRH was significantly poorer than healthy controls and those of patients with other functional GI disease and comparable to patients with diabetes and depression (12).

This study sought to assess clinical factors associated with SRH in a cohort of moderate-to-severe IBS patients. Consistent with previous research showing that physical health is a strong predictor of SRH, we predicted that the severity of IBS symptoms would account for a significant amount of variance in SRH after controlling for confounding factors. Because health perceptions appear to involve components other than physical health and are often based on psychosocial factors, we expected that they would also predict SRH for IBS patients.

METHODS

Participants

Participants included 234 consecutively evaluated IBS patients recruited primarily through local media coverage and community advertising and referral by local physicians to tertiary-care clinics at two academic medical centers in Buffalo, NY and Chicago, IL. To be eligible to participate in the study, all participants must have met the Rome III diagnostic criteria (14) as determined by a board-certified gastroenterologist. Because this study was conducted as part of a clinical trial for patients with IBS (15), participants must have also reported IBS symptoms of at least moderate severity (i.e., symptom occurring at least two times weekly for a minimum of 6 months and causing life interference). Patients were excluded if they presented with a comorbid organic GI disease that would adequately explain GI symptoms; mental retardation; current or past diagnosis of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders; current diagnosis of depression with suicidal ideation; and current diagnosis of psychoactive substance abuse. Institutional review board approval and written (UB, 19 May 2009; NU, 19 December 2008), signed consent were obtained before the study began. This study was completed in full compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Procedure

After a brief telephone interview to determine whether participants were likely to meet basic inclusion criteria, participants were scheduled for a medical interview to confirm a diagnosis of IBS (16) and psychometric testing, which for the purposes of this study included the test battery described below. In addition to SRH, the test battery was drawn from psychometrically validated measures that reflect three distinct domains (i.e., somatic, psychological, and social) of well-being.

Measures

Self-rated health

We adopted the practice (17,18) of measuring SRH by asking subjects “In general, would you say your health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” (1 = excellent, 5 = poor). Lower scores signify better perceived health.

Somatic measures

IBS symptom severity

The IBS Symptom Severity Scale (IBS-SSS) (19) is a five-item instrument used to measure severity of abdominal pain, frequency of abdominal pain, severity of abdominal distension, dissatisfaction with bowel habits, and interference with QOL, each on a 100-point scale. For four of the items, the scales are represented as continuous lines with end points 0 and 100%, with different descriptors at the end points and adverb qualifiers (e.g., “not very,” “quite”) strategically placed along the line. Respondents mark a point on the line between the two end points reflecting the extremity of their judgment. The proportional distance from zero is the score assigned for that scale (hence, scores range from 0 to 100). The end points for the severity items are “no pain” and “very severe,” for satisfaction, the end points are “not at all satisfied” and “very satisfied,” and for interference they are “not at all interferes” to “completely interferes”. A final item asks the number of days out of 10 the patient experiences abdominal pain and the answer is multiplied by 10 to create a 0 to 100 metric. The items are summed and thus the total score can range from 0 to 500.

Quality of life

QOL was assessed using the 34-item IBS-QOL measure (20), which was constructed specifically to evaluate QOL impairment due to IBS symptoms. Each item is scored on a five-point scale (1 = not at all, 5 = a great deal) that represents one of eight dimensions (dysphoria, interference with activity, body image, health worry, food avoidance, social reaction, sexual dysfunction, and relationships). Items are scored to derive an overall total score of IBS related QOL. To facilitate score interpretation, the summed total score is transformed to a 101-point scale ranging from 0 (poor QOL) to 100 (maximum QOL).

Somatization

Somatization (medically unexplained symptoms) was measured using the Screening for Somatoform Symptoms-7 (SOMS-7) (21). The SOMS-7 includes a total of 53 physical symptoms (e.g., dry mouth, heart palpitations), drawn from the DSM-IV and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) definitions for somatization disorder and somatoform autonomic dysfunction. Subjects are instructed to report only complaints for which physicians have found no underlying physical pathological cause. Respondents are asked to report the symptoms that have been present during the past 7 days (21). The total number of endorsed unexplained somatic symptoms yields a somatization symptom count, which has been found to discriminate patients with somatoform disorders from those with other forms of mental disorders.

Medical comorbidity

Medical comorbidity was assessed using a psychometrically validated (22) comorbidity checklist that covers 112 medical conditions organized around 12 body systems (musculoskeletal, digestive, kidney/genitourinary, endocrine, respiratory, circulatory, cardiovascular, oral, central nervous system, dermatological, ear, nose, throat (ENT), cancer). Respondents were asked whether a doctor had ever diagnosed them with a condition and, if so, whether the condition was present in the past 3 months. Persons were counted as current cases if the diagnosed condition was reported as present in the past 3 months. A total comorbidity score was based on the number of medical comorbidities a patient reported as present over the previous 3 months.

Abdominal pain

Abdominal pain intensity over the previous 7 days was measured with an 11-point numerical rating scale, where 0 = no pain and 10 = worst possible pain (23). Patients circled the number from 0 to 10 that best described their average abdominal pain over the past 7 days.

Fatigue

Fatigue was measured using the vitality scale of the SF-12 Health Survey (24,25), an abbreviated measure of the SF-36 Health survey. The SF-12 Vitality Scale requires respondents to indicate how much of the time during the past 4 weeks they had a lot of energy. Possible responses ranged from 1 (all of the time) to 6 (none of the time), with a lower score indicating higher vitality (greater energy/lower fatigue). The SF-12 Vitality Scale has been used in previous research assessing fatigue in IBS patients (26).

Psychological measures

Perceived stress

The four-item version of the Perceived Stress Scale (1988)(27) measures the degree to which situations in one’s life are appraised as uncontrollable, unpredictable, and overloading. These three factors are regarded as central components of the stress experience. Items are rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often).

Depression

The presence and severity of depressive symptoms were measured using the 21-item Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) (28). The scale includes 21 items rated on a four-point Likert scale ranging from an intensity of “0” to “3.”

Anxiety

Trait anxiety was measured using the abbreviated Trait scale of the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (29). In responding to the 10 items of the T-Anxiety scale, subjects indicate how they generally feel by rating the frequency of their feelings of anxiety on a four-point scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always).

Anxiety sensitivity

Fear of anxiety and arousal symptoms in general was measured using the Anxiety Sensitivity Inventory (30). This self-report measure reflects fear of anxiety (e.g., “It scares me when I am anxious”), arousal-related bodily sensations (“It scares me when my heart beats rapidly”), and their consequences (e.g., “When I notice my heart is beating rapidly, I worry that I might have a heart attack”). The 16 items of the Anxiety Sensitivity Inventory are rated on a six-point scale (0 = very little, 5 = very much) and yield a range of scores ranging from 0 to 64 with higher scores signifying greater fear of anxiety/arousal symptoms.

Visceral sensitivity

Fear of visceral sensations was assessed using the 15-item Visceral Sensitivity Index (31). Items are rated on a six-point scale, reverse scored, yielding a range of scores from 0 (no GI-specific anxiety) to 75 (severe GI-specific anxiety).

Social measures

Negative interactions

The negative quality of social relationships was measured with the five-item Negative Interactions Scale that assesses social interactions characterized by conflict, excessive demands, and/or criticism (32,33). The frequency of negative social exchanges with a spouse, family members, friends, neighbors, and in-laws are rated on a five-point scale ranging from 1 = never to 4 = very often. Additional information concerning the Negative Interactions Scale can be found elsewhere (34).

Social support

The positive quality of social relationships was measured with the short form of the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (35). The Interpersonal Support Evaluation List consists of a list of 12 statements concerning the perceived availability of social support. A total score of all items (after reverse coding six items) yields an index of the patient’s general perception of social support. Items are rated on a four-point scale with anchors ranging from “definitely true” to “definitely false”.

Data analysis plan

Data analyses were carried out in three steps. First, the sample was characterized using means, s.d.’s, or percentages. Then, we conducted partial correlations to describe the magnitude of the relationships among clinical variables and SRH after controlling for potentially confounding variables (i.e., age, gender, education level, illness duration, bowel type, etc.). Because correlations do not account for overlap among variables, the third step involved multiple regression analyses to determine if a significant proportion of variance in SRH was accounted for by control and clinical variables. To accomplish this, hierarchical multiple regression analyses were performed. Conceptually distinct blocks of variables (demographic, somatic, psychological, social) were entered sequentially with demographics entered first followed by somatic, psychological, and social variables. All α levels were set at P < 0.05. All data analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the sample

Table 1 displays the demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample. The sample was predominately young, educated, female, and chronically ill (average duration of IBS symptoms = 16.2 years). Of 234 subjects, 29% (N = 69) described their health as very good or excellent, 48% (N = 114) described their health as good, and 21% (N = 51) described their health as fair or poor. The mean total score of 284.8 on the IBS Symptom Severity Scale for the sample falls in the high moderate range of IBS symptom severity (severe > 300). The mean score for the IBS-QOL was 56.5, which suggests that our cohort had significant QOL impairment due to IBS symptoms (20). Patients reported an average of nearly eight (M = 7.8) physician-diagnosed comorbid medical conditions. The most commonly reported medical conditions were seasonal allergies (50.4%), gastroesophageal reflux disease (37.2%), chronic low back pain (28.6%), migraine headache (25.6%), and tension head-ache (25.2%).

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics (N =234)

| M (s.d.) | N ( % ) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 41.0 (14.9) | |

|

| ||

| Gender (% female) | 183 (78.2) | |

|

| ||

| Race (% white) | 208 (88.9) | |

|

| ||

| Education | ||

|

| ||

| High school or less | 47 (20.1) | |

|

| ||

| College degree | 100 (42.7) | |

|

| ||

| Post-college degree | 68 (29.1) | |

|

| ||

| Other | 19 (8.1) | |

|

| ||

| Income | ||

|

| ||

| < 15,000 | 21 (9.0) | |

|

| ||

| 15,001 – 30,000 | 26 (11.1) | |

|

| ||

| 30,001 – 50,000 | 45 (19.2) | |

|

| ||

| 50,000 – 75,000 | 39 (16.7) | |

|

| ||

| 75,001 – 100,000 | 18 (7.7) | |

|

| ||

| 100,001 – 150,000 | 26 (11.1) | |

|

| ||

| > 150,000 | 23 (9.8) | |

|

| ||

| Don’t know/not sure | 11 (4.7) | |

|

| ||

| Prefer not to answer | 25 (10.7) | |

|

| ||

| Duration of IBS (years) | 16.2 (14.0) | |

|

| ||

| IBS subtype | ||

|

| ||

| IBS-constipation | 68 (29.1) | |

|

| ||

| IBS-diarrhea | 97 (41.5) | |

|

| ||

| IBS-alternating | 69 (29.5) | |

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; M, mean.

Associations between clinical variables and SRH

Partial correlations were conducted to assess the magnitude of the relationships between SRH and clinical variables while controlling for possible confounding variables (e.g., age, gender, education level, illness duration, bowel type, etc.). As seen in Table 2, all significant correlations were in the expected manner (lower scores signify better health). SRH was positively associated with fatigue, the number of medical comorbidities, and the number of medically unexplained somatic complaints (r values = 0.36–0.41, P values < 0.05). SRH was negatively associated with QOL impairment because of IBS symptoms, such that patients who rated their global health as poorer reported worse QOL because of IBS symptoms. SRH was weakly, albeit significantly, correlated with overall IBS symptom severity (r = 0.18, P < 0.05) and QOL impairment because of IBS symptoms (r = − 0.17, P < 0.05). Abdominal pain intensity did not significantly correlate with SRH.

Table 2.

Partial correlations between self-rated health and clinical variables (controlling for confounding variables)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | M ± s.d. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SRH | – | 2.9 ± 0.92 | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 2. IBS-SSS | 0.18 | – | 284.8 ± 76.9 | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 3. IBS-QOL | − 0.17 | − 0.46 | – | 56.5 ± 18.9 | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 4. SOMS-7 | 0.36 | 0.26 | − 0.37 | – | 4.7 ± 4.4 | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 5. CoMO | 0.36 | 0.08 | − 0.14 | 0.46 | – | 7.8 ± 6.2 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 6. SF-Fatigue | 0.41 | 0.27 | − 0.41 | 0.35 | 0.24 | – | 4.2 ± 1.1 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 7. PSS | 0.38 | 0.18 | − 0.46 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.44 | – | 6.9 ± 3.3 | |||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 8. BDI-II | 0.37 | 0.22 | − 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.31 | 0.47 | 0.70 | – | 12.5 ± 9.5 | ||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 9. STAI-T | 0.37 | 0.15 | − 0.46 | 0.29 | 0.19 | 0.37 | 0.67 | 0.79 | – | 20.5 ± 6.2 | |||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 10. VSI | 0.21 | 0.44 | − 0.61 | 0.26 | 0.02 | 0.26 | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.41 | – | 44.7 ± 14.2 | ||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 11. NIS | 0.23 | 0.17 | − 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.53 | 0.57 | 0.47 | 0.18 | – | 10.1 ± 3.2 | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| 12. ISEL | − 0.20 | − 0.08 | 0.27 | − 0.17 | − 0.20 | − 0.20 | − 0.36 | − 0.37 | − 0.37 | − 0.20 | − 0.26 | – | 39.5 ± 6.6 |

BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; CoMO, IBSOS Medical Comorbidity Inventory; IBS-QOL, IBS-quality of life; IBS-SSS, IBS-symptom severity scale; ISEL, Interpersonal Support Evaluation List; M, mean; NIS, Negative Interactions Scale; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; SF-Fatigue, SF-12 Vitality Scale; SOMS-7, Screening for Somatoform Symptoms-7; SRH, self-rated health; STAI-T, Stait-Trait Anxiety Inventory-Trait Scale; VSI, Visceral Sensitivity Index.

Note : Numbers that are in bold are signifi cant, P < 0.05.

SRH was also associated with cognitive (perceived stress, anxiety sensitivity, visceral sensitivity) and emotional (depression, anxiety) factors, as well as social (negative social interactions, social support) variables. Of psychosocial factors, the strongest correlations with SRH were with depression, trait anxiety, and stress (r values = 0.37–0.38, P values < 0.05). SRH was also positively and significantly associated with other psychological variables, including visceral sensitivity and anxiety sensitivity, although the magnitude of these correlations was slightly lower (r values = 0.25 and 0.21, P values < 0.05) than the correlations with psychological well-being variables. Similarly, SRH was positively and significantly associated with negative social interactions such that IBS patients who reported poorer health characterized their close relationships as having more negative aspects such as conflict and adverse exchanges. SRH was significantly and negatively associated with social support.

Clinical predictors of SRH

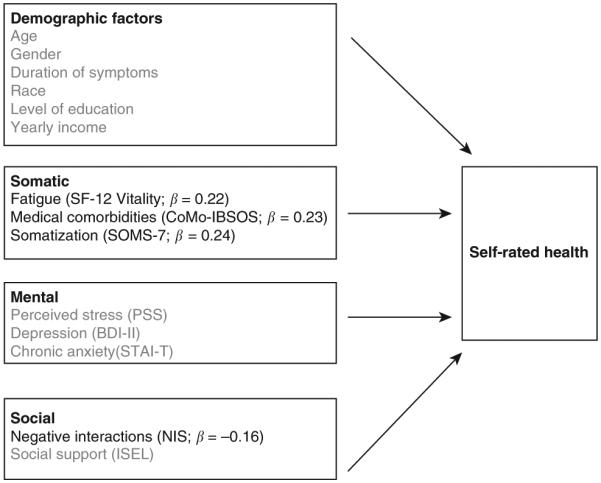

To examine the unique contributions of psychosocial factors in the explanation of SRH, hierarchical multiple regression analyses were performed. As a first step, we conducted tests for multicollinearity because of the intercorrelations among many of the predictor variables. The results showed that the variance inflation factors ranged from 0.22 to 4.43, suggesting that standard errors of the coefficients were not inflated by multicollinearity. In carrying out regressions, we selected the variables from each conceptual domain (somatic, psychological, social) with the two strongest correlations with SRH and then entered them. If the correlation coefficient value was shared by two variables, we entered both into the regression model. Demographic variables were entered into the regression equation in the first step; somatic variables were entered in the second step; the third step introduced psychological variables; and the fourth step introduced social variables. Entering the variables in steps allows us to determine the incremental variance attributed to each conceptually distinct block of variables. The results of the regression analyses are shown in Table 3 and provide partial confirmation for research hypotheses. In step 1, demographic variables explained 6.6% of the variance (R2) in SRH (F = 2.43, P < 0.05). Yearly income was the only statistically significant independent variable. In step 2, somatic illness variables explained an additional 29.6% of the variance in SRH (ΔF = 31.25, P < 0.001). At this step, fatigue, medical comorbidities, and somatization emerged as significant predictors of SRH. However, yearly income did not retain its statistical significance. The addition of psychological variables at step 3 only explained an additional 1.2% of the variance in SRH (ΔF = 1.24, P = NS). At step 3, fatigue, medical comorbidities, and somatization retained their predictive significance but no additional significant predictors emerged. Step 4 introduced social relationship variables, which explained an additional 3.9% of the variance in SRH (ΔF = 2.57, P < 0.05). The final model, as represented in Figure 1, explained 41.3% of the variance in SRH scores (F = 8.49, P < 0.001) with significant predictors including fatigue (t = 3.21, P < 0.01), medical comorbidities (t = 3.47, P < 0.01), somatization (t = 3.22, P < 0.01), and negative social interactions (t = − 2.29, P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Results of multiple linear regressions with self-rated health as dependent variable

| Estimate | s.e. | β | R 2 | Δ R 2 | Adj. R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | 0.066 | 0.039 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Age | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Gender | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.05 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Duration of symptoms | − 0.00 | 0.01 | − 0.02 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Race | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.09 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Level of education | − 0.09 | 0.06 | − 0.11 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Yearly income | − 0.00 | 0.00 | − 0.21 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Step 2 | 0.362 | 0.296 | 0.334 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Age | − 0.00 | 0.01 | − 0.01 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Gender | − 0.02 | 0.13 | − 0.01 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Duration of symptoms | − 0.01 | 0.01 | − 0.08 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Race | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.04 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Level of education | − 0.04 | 0.05 | − 0.04 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Yearly income | − 0.00 | 0.00 | − 0.05 | |||

|

| ||||||

| SF-12 – vitality | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.26 | |||

|

| ||||||

| CoMo-IBSOS | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.24 | |||

|

| ||||||

| SOMS-7 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.30 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Step 3 | 0.374 | 0.012 | 0.336 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Age | − 0.00 | 0.01 | − 0.01 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Gender | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.00 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Duration of symptoms | − 0.01 | 0.01 | − 0.08 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Race | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.05 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Level of education | − 0.04 | 0.05 | − 0.04 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Yearly income | − 0.00 | 0.00 | − 0.04 | |||

|

| ||||||

| SF-12 – vitality | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.22 | |||

|

| ||||||

| CoMo-IBSOS | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.23 | |||

|

| ||||||

| SOMS-7 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.24 | |||

|

| ||||||

| PSS | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.05 | |||

|

| ||||||

| BDI-II | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | |||

|

| ||||||

| STAI-trait | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.08 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Step 4 | 0.413 | 0.039 | 0.378 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Age | − 0.00 | 0.01 | − 0.02 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Gender | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.01 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Duration of symptoms | − 0.01 | 0.01 | − 0.08 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Race | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.05 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Level of education | − 0.04 | 0.05 | − 0.05 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Yearly income | − 0.00 | 0.00 | − 0.03 | |||

|

| ||||||

| SF-12 – vitality | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.22 | |||

|

| ||||||

| CoMo-IBSOS | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.23 | |||

|

| ||||||

| SOMS-7 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.24 | |||

|

| ||||||

| PSS | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.06 | |||

|

| ||||||

| BDI-II | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.04 | |||

|

| ||||||

| STAI-T | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.08 | |||

|

| ||||||

| NIS | − 0.03 | 0.02 | − 0.16 | |||

|

| ||||||

| ISEL | − 0.01 | 0.01 | − 0.03 | |||

BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; CoMo-IBSOS, IBSOS Medical Comorbidity Interview; ISEL, Interpersonal Support Evaluation List; NIS, Negative Interactions Scale; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; SF-12 Vitality, SF-12 Vitality Scale; SOMS-7, Screening for Somatoform Symptoms-7; STAI-T, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-Trait Scale.

Note : Numbers that are in bold are significant, P < 0.05.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of predictors of self-rated health. Nonsignificant predictors in final regression model are grayed out. BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; CoMO, IBSOS Medical Comorbidity Inventory; ISEL, Interpersonal Support Evaluation List; NIS, Negative Interactions Scale; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; SOMS-7, Screening for Somatoform Symptoms-7; STAI-T, Stait-Trait Anxiety Inventory-Trait Scale.

DISCUSSION

We sought to characterize the correlates of self-assessed health in a sample of Rome III-diagnosed IBS patients. This is an important topic for multiple reasons. First, SRH is known to be a robust predictor of future health outcomes (disability, health-care use) relevant to IBS. The importance of SRH was summarized by Idler and Benyamni (4) who wrote that: “Global self-ratings, which assess a currently unknown array of perceptions and weight them according to equally unknown and varying values and preferences, provide the respondents’ views of global health in a way than nothing else can” (p 34). Second, asking patients to describe their health in general is descriptively similar to the introductory question a physician asks patients during a clinic visit. Our data suggest that when judging their own health, IBS patients’ perceived health is a complex concept that captures physical, psychological, and social factors. In this respect, their SRH dovetails with the view of health embodied in biopsychosocial models of functional GI disorders (36,37).

Particularly strong correlates of SRH were distress variables (stress, depression, trait anxiety). Patients who characterized ongoing life circumstances as more stressful reported worse health as did patients who reported higher levels of depression. Patients who rated their health as worse scored higher on a measure of neuroticism (38), a personality style that reflects a general disposition to experience a wide range of negative emotions, particularly in stressful situations (39). This is a notable finding because neuroticism is higher in patients with IBS (40) and represents a risk factor for medically unexplained pain in IBS (41). In an effort to understand the biological substrate of neuroticism in patients with functional GI disorders, Coen et al. (42) recently conducted an imaging study and found that higher neuroticism is associated with greater activity in limbic areas governing cognitive–emotional processing during anticipation of visceral pain but suppressed activity in the same brain regions during pain. These data suggest a biologically mediated tendency among functional GI patients toward heightened arousal in anticipation of pain and ineffective coping (avoidance) strategies during pain episodes. Alternatively, the relationship between neuroticism and SRH may reflect an information-processing style (negative response bias) that exaggerates health problems independent of actual physical impairment (43).

Contrary to predictions, we found only a modest relationship between IBS variables and SRH. Neither global IBS symptom severity nor QOL impairment due to IBS symptoms was strongly associated with SRH in our cohort. This surprised us because our sample included severely affected IBS patients who were prompted to seek treatment for relief of GI symptoms that caused significant life interference. We expected that the day-to-day burden of more severe IBS symptoms would factor more strongly in patients’ health appraisals. Instead, our data suggest that the severity of GI symptoms, even when most severe and disruptive, play a relatively modest role in how IBS patients appraise their health in general. Although seemingly counterintuitive, these findings echo previous research that finds that primary symptom–complaint measures comprise only a small portion of the way individuals define health. In one study (44), for example, “biomedical” variables (e.g., symptom complaints) accounted for relatively little variance in SRH. Instead, most of variability in SRH was accounted for by psychosocial variables such as illness beliefs, mood, and vitality. Similarly, we found that fatigue was a relatively strong correlate of SRH and was one of four significant predictors of SRH. This finding is in line with previous research showing that energy level and fatigue is a critical factor in defining patients’ perception of health and illness and predicting future health outcomes (11,45).

It is worth considering why coexisting extraintestinal somatic complaints (fatigue, somatization, medical comorbidities) are more strongly associated with SRH than the severity of IBS symptoms. One explanation comes from the Common Sense Model of Illness Cognition (46). Synthesizing biomedical and cognitive science research (47), the Common Sense Model of Illness Cognition is the predominant conceptual framework for understanding how people perceive and interpret health problems such as asthma, heart disease, cancer, fibromyalgia, low back pain, HIV, medication adherence, and diabetes (48). A central postulate of the Common Sense Model of Illness Cognition is that people are active problem solvers who do not just think about symptoms in terms of their severity. Across multiple disease states, individuals construct a “common sense” understanding of a health problem or illness (49) by formulating answers to five well-defined questions: What is it? What caused it? How long will it last? What can be done to control or cure it? How will it impact me? Answers to these questions forms a “mental model” that defines patients’ perception of their illness, what it means for their lives, and their coping response. Because they are drawn from personal experience, sociocultural influences, and interactions with others (e.g., family, health-care providers), illness perceptions are not necessarily rooted in medical reality and often at odds from those of health-care professionals (50). For example, when asked to describe what is regarded as a highly abstract concept like “health” (or respond to the clinically ubiquitous and abstract question of “how are you feeling?), individuals turn to more immediately available somatic stimuli in an effort to concretize (i.e., make sense of) what “health” means (51). Patients rely on somatic symptoms like fatigue because they are highly salient perceptual experiences (52) that have “detection advantage” over potentially more severe symptoms (e.g., abdominal pain, urgency, diarrhea) that are quiescent during a brief physician visit. Because of their “real-time” salience, extraintestinal symptoms and their functional limitations have the strongest influence in lowering SRH and predicting future health outcomes (53). This means that patients’ SRH are based on a far wider set of factors than those of their treating clinicians (54) focused on severity of presenting complaints. Patient beliefs may be objectively “far flung” (10) and lacking medical foundation but they just as objectively drive health behavior that has been characterized as the “central outcome in health care” for chronic disease (55).

Because IBS lacks a reliable biomarker (56,57), it can best be understood from the patient’s subjective experience. Patient beliefs and perceptions provide a window into the patient experience. It is tempting to dismiss patient beliefs and other subjective data because of their variability across patients and limited veridicality. A more constructive exercise is to understand better just what patients mean when they describe how they are feeling because these beliefs are fundamental to treatment delivery and illness outcomes (e.g., patient satisfaction, reassurance following medical testing, health-care use) relevant to IBS and other GI diseases. Efforts to understand the type of information patients use to form SRH can help physicians align their characteristically more narrow view of health (58) to patients’ broader self-assessments. This stands to improve the quality of patient–physician relationship, which is, of course, health care’s touchstone (59,60). Otherwise, the gulf between physicians’ assessments of their patients’ health and patients’ health perceptions can “lead patients to feel misunderstood or to misunderstand their doctor, which in turn can lead to low adherence to the physicians recommendations” (Benyamini et al. (53), p 1666). This exercise need not open a Pandora’s box of messy biobehavioral issues but should function as a way of flushing out the reasons for which patients seek treatment, establishing expectations of both patients and physicians, reconciling the expectations that may conflict, and empowering each to do what they realistically can (and cannot) do to control complaints with the resources at their disposal. Whether gastroenterologists choose not to ask patients’ about their illness beliefs does not suspend their impact on health outcomes important to both parties. Because patients are reluctant to disclose their illness beliefs, health-care professionals often assume that their patients share an understanding of their illness. This is not necessarily true and may increase the already high burden IBS imposes on physicians. Drilling down the composition of patients’ beliefs can reduce the IBS burden on physicians by helping them develop a clearer picture of their patients’ health problems, their influences, and more realistic treatment goals that can foster delivery of more effective, satisfying and efficient health care. Even the most robust of treatments are likely to fall short of therapeutic expectations if they do not mesh with how a person views his condition.

For the gastroenterologist and other health-care professionals treating IBS patients, our findings create a potential conundrum. On the one hand, physicians are rightly encouraged (60) to use open-ended general queries (e.g., “Can you tell me how you have been feeling?”) much like the global health question use in this study. Open-ended questions have advantages over close-ended ones in eliciting exploration of topics and facilitating patient engagement. Open-ended questions are sufficiently broad so as to give the patient maximum latitude in responding without restricting the disclosure of personally relevant information. Our data suggest that a potential downside of a relatively open-ended question tapping an abstract construct like health is the elicitation of “noise” that may be tangential to the core problem for which a patient seeks care or the physician has expertise. In other words, while SRH is a more inclusive and accurate measure of global health status (4) from the patient’s perspective, it may be less clinically useful for a physician targeting a circumscribed problem. This is reflected in the observed relationship between SRH and social factors. This pattern of results echoes the results of previous SRH research, which have been attributed to the psychological process of social comparison (10). Whenever people want to gain an accurate appraisal of themselves on some dimension (e.g., health status), they do so by comparing their own characteristics to those of others (61). In light of these data, our data suggest that the social comparison process that patients rely on to evaluate their health status may be influenced by the encounters IBS patients have outside of a physician’s office. Patients whose close relationships are marked by conflict describe themselves as unhealthier. It is possible that individuals with whom patients have negative encounters “stand out” when making the social comparisons that help form health self-appraisals. That they introduce “noise” into a medical encounter does not diminish the value of open-ended questions, which along with other communication skills (60) clearly play an important role in promoting both a quality patient–physician alliance. Our data simply call for well-timed use of open-ended questions in a way that maximizes their strategic value, recognizes their potential limitations, and integrate their answers with more targeted patient-reported symptom measures. As Spiegel writes (1), when collected in the right place at the right time, patient-reported clinical data can effectively aid in detection and management of conditions, improve patient satisfaction, and enhance their relationship with patients.

Results should be interpreted in light of study limitations. Because our data are cross-sectional, we do not intend to suggest that the findings demonstrate causal relationships between clinical variables and SRH. At best, our data can be construed as suggestive of a possible causal relationship between SRH and clinical variables that could be confirmed through longitudinal analyses. This study focused on a limited number of variables believed to influence SRH. Future studies should expand the scope to include such variables as health-care use (current drug regimen, number of diagnostic tests), lifestyle factors such as smoking, diet, or activity level, mental–physical comorbidity, and so on. Although patients’ perceptions of their health are essential for managing a disorder like IBS, we are not convinced that SRH obtained through testing are a perfect proxy for health appraisals revealed in a clinical setting. It is possible that gastroenterologists elicit more targeted perceptions of digestive (vs. global) health status in which case the impact of psychosocial and somatic factors may differ from our findings. We also believe that the line of research could benefit from a measure of self-rated GI health. Because of the relative demographic homogeneity of our select sample of patients enlisted in a behavioral trial (mostly white, female, chronically ill and educated patients seeking non-drug treatment for more severe symptoms), our results may not generalize to a broader, more diverse population such as patients with more mild symptoms that may very well correlate more strongly with SRH. We did not obtain physiological measures of gut or brain function. This is an innovative area of future study that stands to clarify what biological mechanisms underlie patients’ health perceptions and their efforts to manage chronic GI disease.

In sum, the way IBS patients describe how they feel in both clinical and research settings is complex and captures social, psychological, and physical factors including both GI and particularly non-GI somatic complaints. Data suggest that patient’s health beliefs are the product of a constructive appraisal process influenced to some extent by extraintestinal and psychosocial factors and not simply a straightforward projection of a person’s actual digestive health. This creates a potential “mismatch” between physicians’ narrower perceptions of patients’ health focused on underlying disease and symptom severity and their broader health perceptions. Aligning their health perceptions stands to improve the quality of physician–patient relationship, treatment adherence, and patient satisfaction, all of which will be increasingly important in a value-based, data -driven, patient-centered health-care environment.

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS CURRENT KNOWLEDGE

✔ Self-ratings of health (SRH) are powerful predictors of outcomes (e.g., mortality, health-care use, disability).

✔ Little is known about how SRH influences irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) outcomes (e.g., IBS symptom severity).

WHAT IS NEW HERE

✔ SRH among IBS patients is a complex, multidimensional phenomenon based on IBS and non-IBS factors.

✔ SRH are most strongly associated with extraintestinal complaints and psychosocial functioning.

✔ The severity of IBS symptoms plays a minor role in shaping health appraisals among IBS patients.

✔ Aligning physicians’ perception of patients’ health status with their own health perceptions may improve care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr Frank Hamilton (NIDDK Project Scientist, IBS Outcome Study (IBSOS)) for his constructive comments on a previous draft of this manuscript as well as members of the IBSOS Research Group (Jason Bratton, Rebecca Firth, Darren Brenner, Leonard Katz, Laurie Keefer, Susan Krasner, Sarah Quinton, Christopher Radziwon, Michael Sitrin) for their assistance on various aspects of the research reported in this manuscript.

Financial support: This study was funded by NIH grant DK77738.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Guarantor of the article: Jeffrey M. Lackner, PsyD.

Specific author contributions: Jeffrey Lackner participated in study design, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript preparation; Elyse Thakur, data analysis and manuscript preparation; Gregory Gudleski, data analysis and manuscript preparation; Travis Stewart, manuscript preparation; Gary Iacobucci, manuscript preparation; and Brennan Spiegel, manuscript preparation.

Potential competing interests: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Spiegel BM. Patient-reported outcomes in gastroenterology: clinical and research applications. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;19:137–48. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2013.19.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lackner JM, Jaccard J, Baum C, et al. Patient-reported outcomes for irritable bowel syndrome are associated with patients’ severity ratings of gastrointestinal symptoms and psychological factors. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:957–964. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.06.014. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, et al. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88:879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38:21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Improving outcomes in chronic illness. Manage Care Q. 1996;4:12–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74:511–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marshall S, Haywood K, Fitzpatrick R. Impact of patient-reported outcome measures on routine practice: a structured review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;12:559–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorn SD, Hernandez L, Minaya MT, et al. Psychosocial factors are more important than disease activity in determining gastrointestinal symptoms and health status in adults at a celiac disease referral center. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3154–63. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1342-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1179–87. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.002. e1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krause NM, Jay GM. What do global self-rated health items measure? Med Care. 1994;32:930–42. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199409000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benyamini Y, Idler EL, Leventhal H, et al. Positive affect and function as influences on self-assessments of health: expanding our view beyond illness and disability. J Gerontol Ser B. 2000;55:P107–16. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.2.p107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spiegel BM, Gralnek IM, Bolus R, et al. Clinical determinants of health-related quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1773–80. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.16.1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hahn BA, Yan S, Strassels S. Impact of irritable bowel syndrome on quality of life and resource use in the United States and United Kingdom. Digestion. 1999;60:77–81. doi: 10.1159/000007593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Talley NJ, et al. The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Diagnosis, Pathophysiology and Treatment: A Multinational Consensus. 2nd Degnon Associates; McLean, VA: 2006. Rome III. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lackner JM, Keefer L, Jaccard J, et al. The Irritable Bowel Syndrome Outcome Study (IBSOS): rationale and design of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial with 12 month follow up of self-versus clinician-administered CBT for moderate to severe irritable bowel syndrome. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:1293–310. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480–91. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M. SF-36 Health Survey and Interpretation Guide. QualityMetric Incoporated; Lincoln, RI: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drossman DA, Morris CB, Schneck S, et al. International survey of patients with IBS: symptom features and their severity, health status, treatments, and risk taking to achieve clinical benefit. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:541–50. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318189a7f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Francis CY, Morris J, Whorwell PJ. The irritable bowel severity scoring system: a simple method of monitoring irritable bowel syndrome and its progress. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:395–402. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.142318000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patrick DL, Drossman DA, Frederick IO. A Quality of Life Measure for Persons with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS-QOL): User’s Manual and Scoring Diskette for United States Version. University of Washington; Seattle, WA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rief W, Hiller W. A new approach to the assessment of the treatment effects of somatoform disorders. Psychosomatics. 2003;44:492–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.44.6.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lackner JM, Ma CX, Keefer L, et al. Type, rather than number, of mental and physical comorbidities increases the severity of symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1147–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turk DC, Dworkin RH, Burke LB, et al. Developing patient-reported outcome measures for pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2006;125:208–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–33. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kosinski M, Zhao SZ, Dedhiya S, et al. Determining minimally important changes in generic and disease-specific health-related quality of life questionnaires in clinical trials of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1478–87. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200007)43:7<1478::AID-ANR10>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lackner JM, Gudleski GD, Dimuro J, et al. Psychosocial predictors of self-reported fatigue in patients with moderate to severe irritable bowel syndrome. Behav Res Ther. 2013;51:323–31. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen S, Williamson G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapam S, Oskamp S, editors. The Social Psychology of Health: Claremont Symposium on Applied Social Psychology. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beck AT, Steer R, Brown G. Beck Depression Inventory-II Manual. Harcourt Assessment; San Antonio, TX: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spielberger CD. State-Trait Personality Inventory (STPI) Mind Garden; Redwood City, CA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peterson RA, Reiss S. Anxiety Sensitivity Index: Revised Test Manual. IDS Publishing Corporation; Worthington, OH: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Labus JS, Bolus R, Chang L, et al. The visceral sensitivity index: development and validation of a gastrointestinal symptom-specific anxiety scale. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:89–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krause N. Negative interaction and heart disease in late life—exploring variations by socioeconomic status. J Aging Health. 2005;17:28–55. doi: 10.1177/0898264304272782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schuster TL, Kessler RC, Aseltine RH., Jr Supportive interactions, negative interactions, and depressed mood. Am J Community Psychol. 1990;18:423–38. doi: 10.1007/BF00938116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lackner JM, Gudleski GD, Firth R, et al. Negative aspects of close relationships are more strongly associated than supportive personal relationships with illness burden of irritable bowel syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74:493–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarck T, et al. Measuring the functional components of social support. In: Sarason IG, Sarason B, editors. Social Support: Theory, Research and Applications. Martinus Nijhoff; The Hague: 1985. pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Drossman DA. A Biopsychosocial Approach to Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Improving the Physician–Patient Relationship. Zancom International; Ontario, Canada: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Naliboff B, Lackner JM, Mayer E. Psychosocial factors in the care of patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders. In: Yamada T, editor. Principles of Clinical Gastroenterology. Wiley; New York, NY: 2008. pp. 20–37. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lackner JM, Jaccard J, Blanchard EB. Testing the sequential model of pain processing in irritable bowel syndrome: a structural equation modeling analysis. Eur J Pain. 2005;9:207–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Costa P, McCrae RR. Neuroticism, somatic complaints, and disease: is the bark worse than the bite? J Person. 1987;55:229–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1987.tb00438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spiller RC. Role of infection in irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42(Suppl 17):41–7. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1925-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gwee KA, Leong YL, Graham C, et al. The role of psychological and biological factors in postinfective gut dysfunction. Gut. 1999;44:400–6. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.3.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coen SJ, Kano M, Farmer AD, et al. Neuroticism influences brain activity during the experience of visceral pain. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:909–17. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.008. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watson D, Clark LA. Negative affectivity: the disposition to experience aversive emotional states. Psychol Bull. 1984;96:465–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andersen M, Lobel M. Predictors of health self-appraisal: what’s involved in feeling healthy? Basic Appl Soc Psychol. 1995;16:121–36. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benyamini Y, Idler EL. Community studies reporting association between self-rated health and mortality: additional studies, 1995 to 1998. Res Aging. 1999;21:392–401. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leventhal H, Brissette I, Leventhal EA. The common-sense model of self-regulation of health and illness. In: Cameron LD, Leventhal H, editors. The Self-Regulation of Health and Illness Behaviour. Routledge, Chapman & Hall; New York, NY: 2003. pp. 42–65. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leventhal H, Leventhal EA, Breland JY. Cognitive science speaks to the “common-sense” of chronic illness management. Ann Behav Med. 2011;41:152–63. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9246-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kapstein AA, Scharloo M, Helder DI, et al. The Self-Regulation of Health and Illness Behaviour. Routledge; New York, NY: 2003. Representations of chronic illnesses; pp. 97–118. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brownlee S, Leventhal H, Leventhal E. Hand-book of Self-Regulation. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2000. Regulation, self-regulation, and construction of the self in the maintenance of physical health; pp. 369–416. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Diefenbach MA, Leventhal EA, Leventhal H, et al. Negative affect relates to cross-sectional but not longitudinal symptom reporting: data from elderly adults. Health Psychol. 1996;15:282–8. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.4.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leventhal H, Leventhal EA, Contrada RJ. Self-regulation, health, and behavior: a perceptual–cognitive approach. Psychol Health. 1998;13:717–33. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Benyamini Y, Leventhal EA, Leventhal H. Self-assessments of health: what do people know that predicts their mortality? Res Aging. 1999;21:477–500. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Benyamini Y, Leventhal EA, Leventhal H. Elderly people’s ratings of the importance of health-related factors to their self-assessments of health. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:1661–7. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00175-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Petrie KJ, Weinman J. Patients’ perceptions of their illness: the dynamo of volition in health care. Curr Direct Psychol Sci. 2012;21:60–5. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kaplan RM. Behavior as the central outcome in health care. Am Psychol. 1990;45:1211–20. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.11.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Food and Drug Administration. US Department of Health and Human Services. 2012 May; [Google Scholar]

- 57.Burke LB, Kennedy DL, Miskala PH, et al. The use of patient-reported outcome measures in the evaluation of medical products for regulatory approval. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:281–3. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hall JA, Epstein AM, McNeil BJ. Multidimensionality of health status in an elderly population. Construct validity of a measurement battery. Med Care. 1989;27:S168–77. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Johns Hopkins, American Healthways Defining the patient–physician relationship for the 21st century. Dis Manage. 2004;7:161–79. doi: 10.1089/dis.2004.7.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Drossman DA. 2012 David Sun lecture: helping your patient by helping yourself—how to improve the patient–physician relationship by optimizing communication skills. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:521–8. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Festinger L. A theory of social comparison processes. Hum Relat. 1954;7:117–40. [Google Scholar]