Abstract

Developmental deficiency of somatic embryos and regeneration to plantlets, especially in the case of transformation, are major problems of somatic embryo regeneration in alfalfa. One of the ways to overcome these problems is the use of natural plant regulators and nutrients in the culture medium of somatic embryos. For investigating the influence of Cuscuta campestris extract on the efficiency of plant regeneration and transformation, chimeric tissue type plasminogen activator was transferred to explants using Agrobacterium tumefaciens, and transgenic plants were recovered using medium supplemented with different concentration of the extract. Transgenic plants were analyzed by PCR and RT-PCR. Somatic embryos of Medicago sativa L. developed into plantlets at high frequency level (52 %) in the maturation medium supplemented with 50 mg 1−1C. campestris extract as compared to the medium without extract (26 %). Transformation efficiency was 29.3 and 15.2 % for medium supplemented with dodder extract and without the extract, respectively. HPLC and GC/MS analysis of the extract indicated high level of ABA and some compounds such as Phytol, which can affect the somatic embryo maturation. The antibacterial assay showed that the extract was effective against some strains of A. tumefaciens. These results have provided a scientific basis for using of C. campestris extract as a good natural source of antimicrobial agents and plant growth regulator as well, that can be used in tissue culture of transgenic plants.

Keywords: Somatic embryo, Cuscuta campestris extract, Medicago sativa L., Embryo maturation

Introduction

Because of mass production and feeding value, alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) is one of the most important forage crops. Efficient plant regeneration, perfect regeneration ability from single or multiple cells, is one of the most important factors in successful application of plant tissue culture techniques for improvement of crops through genetic modifications (Rao and Suprasanna 1999). Somatic embryogenesis is the main pathway for many plant species regeneration (Kirkorian 2000). Somatic embryogenesis provides a valuable tool to increase the efficiency of genetic improvement of many economically important crops (Rai et al. 2010). Maturation deficiency of somatic embryos and low rate of transformation, development to plantlets are major problems of somatic embryo regeneration in many species of alfalfa. Since somatic embryos lack endosperm, which is a source of plant regulators and nutrients, providing natural plant regulators and nutrients in the culture medium could be helpful to somatic embryos. Abscisic acid improves the somatic embryo maturation and their development into normal plantlets (Vahdati et al. 2008). Culture medium can be enriched with natural organic extracts which has amino acids, vitamins and some plant regulators that can promote plant growth, regeneration and somatic embryogenesis. Some organic extracts such as yeast extract, casein hydrolysate (Joshee et al. 2007), coconut water (Ahmed et al. 2011), cyanobacterial extracts (Palikova et al. 2007) and plant-derived smoke extract (Ghazanfari et al. 2012) enhanced somatic embryogenesis and embryo maturation. Factors which promote maturation and conversion of somatic embryos might exist in C. campestris extract and active substances in this extract stimulate conversion of a somatic embryo to perfect plantlet.

Tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA), a serine protease, with 60–65 kD molecular weight in the fibrinolytic system, triggers local fibrinolysis (Teesalu et al. 2002; Nabiabad et al. 2016). Recombinant forms of tPA are used to treatment of heart attacks, stroke and pulmonary embolism. In this study, TPA gene was transformed to leaves and petioles of alfalfa and the effect of C. campestris extract was investigated on somatic embryos maturation and efficiency of transformation.

Materials and methods

Cuscuta campestris extract preparation

The plant sample (C. campestris) was collected from the Hamadan province of Iran, during June 2014. The sample was transferred to the laboratory and confirmed by plant biologist, a voucher specimen (NO: 6737) was deposited in the herbarium of Faculty of Science at Bu Ali Sina University. The sample was dried at room temperature in a shaded area away from direct sunlight. Dried samples were powdered by a cylindrical crusher. Ethanolic, aqueous and methanolic extracts were prepared by maceration method (Nedeljko et al. 2012). Powdered plant material (30.0 g) was added to 100 ml of solvents (aqueous, ethanol and methanol) and shaked for 72 h at 120 rpm. Tissue debris was removed from the extracts by filtration through a Whatman filter paper and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The top layer was transferred into the rotary evaporator and concentrated. The extracts were transferred into the oven and dried at 42 °C for 24 h. About 400 mg of dried extracts was dissolved in the distilled water, dilution series of extract (0, 25, 50. 100, 200 mg ml−1) were prepared.

Somatic embryogenesis and development of embryos

Medicago sativa Ghare yonje ecotype (naitive cultivar) was used in all experiments of this study. Because of the best regeneration of young expanded leaves and petioles, these pieces from 4 to 6 week’s old sterile seedlings were placed on MS medium containing 54 mM of proline (Mathur et al., 2008), 0.4 mg l−1 kinetin and 4 mg l−1 2-4-D followed by incubation at 25 ± 2 °C for 3–4 weeks in dim light (30–35 µE m−2 s−1). Five hormone combinations, (2,4-D + kinetin: 2.00 + 0.20 mg l−1; 4.00 + 0.40 mg l−1; 6.00 + 0.60 mg l−1; 8.00 + 0.80 mg l−1; 10.00 + 1.00 mg l−1) were used at individual steps for induction of embryogenic calli. The most effective hormone concentration for the development of subsequent callus with a high embryogenic capacity (4 mg l−1 2,4-D and 0.4 mg l−1 kinetin) was used in MS medium supplemented with 54 mM of proline (data not shown). The induced calli were lightly smashed and transferred onto modified Boi 2Y medium (Sigma-aldarich, pH 5.8, 1L, consisting of 1000 mg NH4NO3, 1000 mg KNO3, 65 mg KCl, 35 mg MgSO4·7H2O, 300 mg KH2PO4, 347 mg Ca(NO3)2, 0.8 mg KI, 1.6 mg H3BO3, 4.4 mg MnSO4·H2O, 1.5 mg ZnSO4·7H2O, 32 mg Na Fe EDTA, 100 mg myo-inositol, 0.5 mg nicotinic acid, 0.1 mg pyridoxine HCl, 0.1 mg thiamine HCl, 2.0 mg glycine, 2000 mg yeast extract, 6000 mg agar, Blaydes 1966) supplemented with different concentrations of filter-sterilized C. campestris extracts and then incubated at 16 h light period, (40 µE m−2 s−1). Numerous somatic embryos were formed after 2–3 weeks. The embryos were cultured for 6 weeks on a maturation medium which was refreshed weekly. Individual somatic embryos with enlarged cotyledons were transferred into an MMS medium (MS medium containing Nitsch vitamin) supplemented with different amounts of C. campestris extracts until shoot meristems and radicles were developed. The effects of different concentrations of C. campestris extract on some parameters of somatic embryo maturation were examined. These parameters included percentage (%) of somatic embryo per plantlet conversion, embryo size, embryo fresh weight, number of embryos produced only shoot or root and length of the shoot. Somatic embryos containing both shoot and root were considered as normal mature embryos.

Cloning of chimeric tissue type plasminogen activator

Constructed chimeric-tPA (Nabiabad et al. 2016) was cloned in T/A cloning vector. The ligation mix was transformed into competent Escherichia coli (E. coli) DH5α cells and transferred to ampicillin containing LB-agar plates. After overnight incubation colonies were screened by PCR and plasmids from the insert positive colonies were extracted and sequenced at GATC Biotech AG, Konstanz, Germany. Chimeric segment was digested with BamHI and SstI, subcloned into plant pBI121 binary vector and transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain LBA 4404.

Transformation of leave and petiole explants and plant regeneration

Agrobacterium tumefaciens was cultured in LB medium until the OD nm 600 reached about 0.6-0.7. The Agrobacterium culture was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 5 min, and pellets were resuspended in MS liquid medium. MS medium contained 50 mg l−1 kanamycin, 50 mg l−1 acetosyringone, and 50 mg l−1 rifampicin. 200 pieces of leaves and petiole from 4 to 6 week’s old sterile seedlings were co-cultured for 4 min in the bacterial suspension. The explants were then blotted dry on sterile filter paper to remove excess bacterial solution, and cultured on co-culture medium (solid MS medium containing 54 mM proline, 0.4 mg l−1 kinetin and 4 mg l−1 2, 4-D pH 5.7 with KOH) followed by incubation for 6 days at 25 ± 2 °C in the dark. Six days after co-culture, the explants were washed by soaking in sterile distilled MS, blotted on filter paper, and were then transferred to medium supplemented with 50 mg l−1 kanamycin and 200 mg l−1 cefatoxime and cultured for 2–3 weeks under 25 ± 2 °C in dim light (30–35 µE m−2 s−1). Well-developed embryogenic calli were then transferred to BOi2Y-free hormone medium containing 50 mg l−1 kanamycin and different concentrations of filter-sterilized C. campestris extract. Germinated embryos were transferred to the MMS medium still contained different amounts of filter-sterilized C. campestris extract, 50 mg l−1 kanamycin at the pH was adjusted 5.7. Individual rooted plantlets were transferred to pots containing sterile soil and sand (1:1 v/v) and grown under standard greenhouse conditions.

Histological studies

For histological investigations, calli and somatic embryos were fixed in FAA (formalin-acetic acid–ethanol, 10:5:85, v/v) for 18 h, dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol and then embedded in paraffin. 7–8 mm thick serial sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Finally, permanent slides were examined with a light microscope equipped with a camera.

Quantification of ABA by HPLC

ABA was isolated from dodder plants. Fresh plant material was extracted three times with 40 ml of 80 % aqueous methanol for 30 min at 4 °C. The mixture was filtered in a separate conical flask using Whatman filter paper No 1. Then the sample was vacuum evaporated in a lyophilizer (model Christ α-2-4, Germany) and the vacuum dried residue was re-dissolved in 10 ml of 0.5 M phosphate buffer (pH 8) by stirring for 30 min. The suspension was washed with 20 ml of light petroleum spirit. The sample pH was adjusted to 2.8 using HCl and extracted four times with ethyl acetate (4 × 10 ml). The extract was lyophilized and re-dissolved in 5 ml of 0.5 M phosphate buffer (pH 8). The sample was then purified by passing through a Sephadex G10 column. The eluted solution was again lyophilized and the residue was finally dissolved in 1 ml of acetonitrile and analyzed by HPLC system, with C18 column (25 cm × 4.6 mm) and UV detector (at 254 nm). The calibration standards of concentration 1, 5, 10 and 100 µg per ml were prepared by successive dilutions of the above working stock solution. A mixture of 0.5 % acetic acid (40 ml) and acetonitrile (60 ml) was used as mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.3 ml min−1.

Sample preparation for GC–MS analysis

About 50 μl of the extract was dissolved in 2 ml of deionized water and kept in an ultrasonic bath for 15 min, centrifuged for 10 min at 6000 rpm and the supernatant was used as GC/mass injection sample. GC–MS of methanolic extract was performed using Agilent 790A apparatus. The mass spectrum scans range was set at 30.0–510 (m/z). Compounds were separated on Agilent 1909S-433, 5 % phenyl methyl silox column (30 × 0.25 μm ID × 0.25 μm df). The oven temperature was programmed as follows: isothermal temperature of 55 °C for 3 min, then increased to 155 °C at the rate of 8 °C min−1 and held for 1.75 min, then increased to 285 °C at the rate of 10 °C min−1 and kept constantly for 7 min. The total run time was 48 min. Ionization of sample components was performed on EI mode (70 eV). The carrier gas was helium (99.999 %) at 1.0 ml min−1 flow rate. The sample was injected in split mode of 20:1. The relative percentage of each component was calculated by comparing its average peak area to the total areas. Identification of chemical compounds of the extract was based on GC retention time on capillary column and computer matching of mass spectra with those of standards (Mainlab, Replib and Tutorial data of GC–MS system).

Antibacterial activity of C. campestris extract by agar well diffusion method

The agar well diffusion method was used to determine the antibacterial activity of the crude extracts (Tayoub et al., 2012). Aqueous, ethanolic and methanolic extracts were prepared with different concentrations (50, 100 and 200 mg ml−1) and use of three strains of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. About 100 micro liter of bacterial suspension culture (1.5 × 108 cfu) was inoculated on sterile Mueller–Hinton agar plates and spread uniformly with a swab. Finally, using a sterile borer, well of 5 mm in diameter was made in the inoculated media and 50 micro liter of each concentration of extracts poured into each well. Plates were incubated at 28 °C for 24 h (Hendra et al. 2011). Standard copper oxy-chloride (10 mg ml−1) and cefatoxime antibiotic (30 µg disc−1) were used as a positive control and solvents of distilled water, methanol and ethanol used as negative control. All experiments were carried out in triplicate. The clear zones formed around each well were measured and average diameter of the inhibition zone calculated and recorded in millimeters.

Determination of (MIC) and (MBC) by serial dilution method

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) of aqueous, ethanolic and methanolic extracts were determined by serial dilution method (Kamonwannasit et al. 2013). To determine MIC, extract dilution series of 20 to 300 mg ml−1 were prepared. After preparing the dilution series, 20 µl of bacterial suspension equivalent to 0.5 Mcfarland was poured to all tubes except positive control one (medium and extract). Finally inoculation tubes were incubated at 28 °C for 24 h. The lowest dilution of extract in which turbidity wasn’t observed, considered as MIC. To determine the MBC from all tubes in which the growth inhibition was observed, a certain amount of these dilutions was cultured on the surface of Mueller–Hinton agar medium. Culture medium was incubated at 28 °C for 24 h. After incubation, the lowest concentration of extract in which no bacterial growth was observed considered as MBC.

Analysis of the transgenic plants by PCR and RT-PCR

The presence of chimeric-tPA gene in the genome of putative transformed plants was confirmed by PCR using specific primers (forward: 5′-TCTCCACCCCTGTTCGGGCGAAAGAGAA-3′ reverse: 5′-AGAGGTTGTGATGTGCAGCGGCTGG-3′). Total RNA was isolated from transgenic plants (100 mg) using RNXPlus reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (SinaClon, Iran). Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis was performed based on Nabiabad et al. (2011) method and the amplified PCR products were electrophoresed on 1 % agarose gel containing ethidium bromide and photographed.

Statistical analysis and experimental design

All experiments were arranged in a randomized complete block design with at least three replications. All data were analyzed by analysis of variance using PC SAS (version 6.03). All treatment means were subjected to least significant differences (LSD) and calculated at the 5 % level of probability.

Results

Somatic embryogenesis and histological studies of somatic embryos

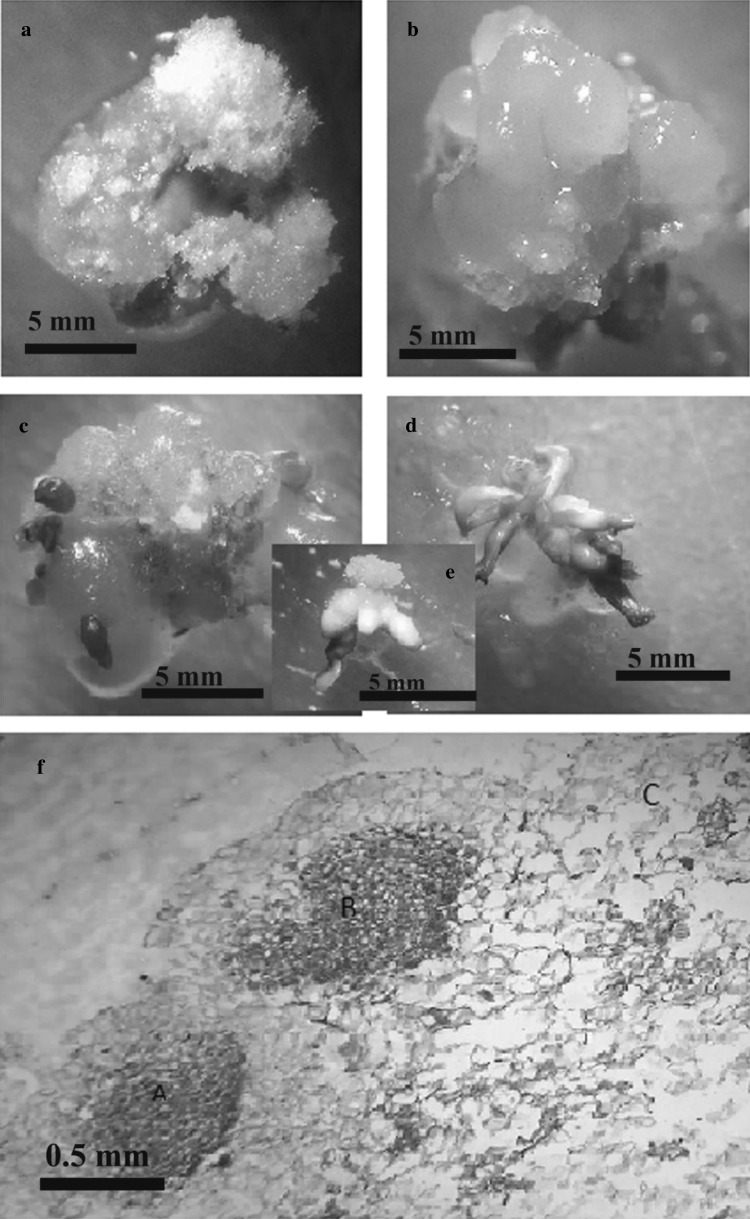

Embryogenic calli were observed 2–3 weeks after induction in MS medium supplemented with 54 mM of proline, 4 mg l−1 2,4-D and 0.4 mg l−1 kinetin. Embryogenic callus induction was inhibited in higher concentration of auxin and cytokinin in accordance with Jana and Shekhawat (2012) results. Also, results of Dhir and Shekhawat (2013) showed that increasing the cytokinins concentration in regeneration medium decreased the percentage of responding. These calli, after being transferred to hormone-free Boi2Y medium supplemented by C. campestris extract produced somatic embryos that occurred on the surface of embryogenic callus as round and smooth (nodular) structures including cytoplasmic cells. These structures without vascular connection to callus and not organogenic in nature approved as somatic embryos by histology of embryogenic callus (Fig. 1). The primary and essential symptom of embryogenesis was the appearance of globular structure that was attached to the surface of the callus by a distinct base.

Fig. 1.

Somatic embryogenesis of Medicago sativa a non-mbryogenic callus, b pre-embryogenic callus, c different developmental stages of somatic embryos, d somatic embryos germination, e somatic embryos at torpedo stage, f histology of somatic embryogenesis of Medicago sativa. A latitudinal section of embryo in globular stage on the surface of callus, B longitudinal section of somatic embryo in heart-shaped stage, C non-embryogenic cells

Determination of the plantlet formation promoting parameters

Germination of somatic embryos was affected by changing concentrations of C. campestris extract in the maturation medium (Fig. 2). The highest conversion rate (52 %) was obtained when the embryos were matured in medium containing 50 mg l−1 of the extract. The fresh weight of somatic embryos increased from 23 mg to 41 mg after exposure to 50 mg l−1 extract for 21 days. But higher concentrations of the extract showed adverse results (Table 1). The results indicate a positive correlation between fresh weight and embryo development. Growth of somatic embryos on media supplemented with the extract (50 mg l−1) increased the size of embryos, but higher concentrations of extract (200 mg l−1) had an adverse effect on embryo size. The highest transformation efficiency (29.3 %) was observed in 50 mg l−1 concentration.

Fig. 2.

Correlation between embryo development to plantlets, embryo fresh weight and extract concentration

Table 1.

Embryo maturation parameters under C. campestris extract concentrations

| Extract concentrations (mg l −1) | Percent (%) of somatic embryo to plantlet conversion | Embryo size and embryo fresh weight after 21 days (mg/10 embryo) | Somatic embryos with only shoot formation (%) | Somatic embryos with only root formation (%) | Shoot length after 2 months (cm) | Transformation efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 26cd | (1.3 mm × 0.7 mm)23c | 11.2a | 0.3d | 2.3c | 15.2 |

| 25 | 43b | (2.5 mm × 1.0 mm)32b | 8.04b | 3.06a | 2.5c | 21.8 |

| 50 | 52a | (2.9 mm × 1.3 mm)41a | 3.0c | 1.74b | 4.1a | 29.3 |

| 100 | 33c | (2.4 mm × 0.9 mm)25c | 4.11c | 2.0b | 3.2b | 18.8 |

| 200 | 10d | (1.1 mm × 0.5 mm)17d | 13.02a | 1.09c | 1.4d | 5.5 |

| LSD = 6.0 | 5.8 | 2.3 | 0.45 | 0.61 |

Same letters are not significantly different at p < 0.01

Somatic embryos without shoot or root meristem were abnormal and only embryos with both elongated roots and developed green shoots were considered as normal germinated embryos. In this study C. campestris extract at 25, 50 and 100 mg l−1 reduced the somatic embryos with only shoot formation, but enhanced the number of somatic embryos with only roots. The extract had a positive effect on shoot length and concentrations of 50 and 100 mg l−1 significantly enhanced the length of the shoot after 2 months in comparison to the control and other extract concentrations (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Panel a: Results of different-extract concentrations on shoot length of regenerated alfalfa plantlets from somatic embryo; panel b and d: plantlets regeneration from somatic embryo (0.0 mg l−1 extract); and panel c and e: plantlets regeneration from somatic embryo (50 mg l−1 extract)

Cuscuta campestris extract compounds

About 21 different compounds were identified by GC/MS analysis in dodder extract. Some of them have more important biological effects and could be used in various applications (Table 2). Phytol is an organic compound that is used to produce K1 and E vitamins. These vitamins involved in initiation of embryogenic calli and growth of early-stage somatic embryo (Pullman et al. 2006).

Table 2.

Identification of the C. Campestris extract compounds by GC/MS analysis

| S. no | Name of compound | Total peak % | RTa | Formula |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,2,3-propanetriol,1-acetate | 5 | 29 | C5H10O4 |

| 2 | Benzofuran,2,3-dihydro | 5 | 26.34 | C8H8O |

| 3 | Glycerol,1,2-diacetate | 2 | 15.20 | C7H12O5 |

| 4 | 2-methoxy-4-vinylphenol | 0.7 | 23.24 | C9H10O2 |

| 5 | Triacetin | 1.2 | 11.36 | C9H14O6 |

| 6 | Thymol | 1.9 | 13.45 | C10H14O |

| 7 | 3-aminopyrrolidine | 0.7 | 21 | C4H10N2 |

| 8 | Hexadecanoic acid, ethyl ester | 4.6 | 16 | C18H36O2 |

| 9 | 1.8 cineole | 7.8 | 30.36 | C10H18O |

| 10 | Benzo[h]quinoline,2, 4-dimethyl | 1.2 | 7 | C15H13 N |

| 11 | 6-Chloro-4-phenyl-2-propylquinoline | 6.1 | 31.24 | C18H16ClN |

| 12 | Cetane | 1.3 | 10.34 | C16H34 |

| 13 | Sarcosine, N-isobutyryl, tetradecyl ester | 1.1 | 9 | C6H11NO3 |

| 14 | 4-((1E)-3-hydroxy-1-propenyl)-2-methoxy phenol | 2.1 | 15.36 | C10H12O3 |

| 15 | 1,5-diphenyl-2H-1,2,4-triazoline-3-thione | 1.9 | 8.24 | C14H11N3S |

| 16 | 1-octadecene | 2.2 | 19 | C18H36 |

| 17 | Heptanamide, N-(1-cyclohexylethyl)-2-methyl | 1.5 | 10.18 | C16H31NO |

| 18 | Scoparone | 24 | 34 | C11H10O4 |

| 19 | 3′-Methyl-2-benzylidene-coumaran-3-one | 14.1 | 32.36 | C16H12O2 |

| 20 | Cinnamic acid | 7 | 30 | C6H5CHCHCO2H |

| 21 | 2-Propenoic acid, 3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-, methyl ester | 7 | 29.48 | C10H10O3 |

| 22 | Phytol | 1.7 | 12.10 | C20H40O |

aRetention time

Quantification of ABA by HPLC

ABA level in the extract of dodder was determined by HPLC analysis using standard ABA and retention time related to the standard. Using the retention time and standard curve, quantity of ABA was determined as 850 ng mg−1 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Chromatogram of HPLC on total ABA extracted from the C. campestris

Antibacterial activity of C. campestris extract

The antibacterial activities of the different extracts (aqueous, ethanolic and methanolic) of C. campestris were evaluated by the agar well-diffusion method (Fig. 5). Combined analysis of variance indicated significant differences between bacterial sensitivity to the type of plant extract and extract concentration levels.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of antibacterial activity of C. campestris extracts against Agrobacterium tumefaciens, using the agar well diffusion method

Methanolic extract (200 mg l−1) showed the highest inhibitory effect and bactericidal activity (Table 3). In this study, the highest antibacterial activity of methanolic extract was detected against AGLO1 strain.

Table 3.

Inhibitory clear zone diameter (mm) of aqueous, ethanolic and methanolic extracts of C. campestris and antibiotic on Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains

| Extract | conc. mg ml−1 | Bacteria | AGLO1 | GV3101 | LBA4404 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | 200 | 28.33b-c | 24.12f-i | 23.33 g-j | |

| 100 | 24f-j | 18.33 h-o | 13.33 m-q | ||

| 50 | 18i-o | 12.41n-q | 8q | ||

| Aqueous | 200 | 24.47f-i | 19.65 h-m | 16.33 k-o | |

| 100 | 12.41n-q | 15.90 k-o | 13.81 m-p | ||

| 50 | 8.51q-p | 8.72p-q | 10.33p-q | ||

| Methanol | 200 | 28.66b-c | 25.33f-h | 26.61c-f | |

| 100 | 24.33f-i | 19.67 h-m | 22.3 g-k | ||

| 50 | 19.11 h-n | 15.33 k-o | 18i-o | ||

| Cefatoxime | 30 µg/disc | 35.87a-c | 37 .88a-b | 39.12a |

The same letters are not significantly different at p < 0.01

Analysis of the transgenic plants by PCR and RT-PCR

All regenerated plant lines were screened by PCR; DNA fragment of 1.8 kb corresponding to the chimeric-tPA was amplified in transgenic plants and no amplification was observed in negative control and non-transgenic plants (Fig. 6). RT-PCR experiments were performed to reveal chimeric-tPA transcripts by using tPA-specific primers on cDNA from putatively transformed plants. The presence of the chimeric-tPA transcript (1.8 kb) in transgenic alfalfa plants confirmed the predicted expression pattern of this fragment in the transgenic plants.

Fig. 6.

Products of PCR and RT-PCR on 1 % agarose. M is 1-kb marker. Located wells on the left side of marker are PCR product (1, 2, 3 and 4 are transgenics, 5 is non-transgenic, 6 is pBI121 as positive control and 7 is negative control). Wells on the right side of ladder are RT-PCR products for tPA (8, 9, 10 and 13 are transgenics, 11 and 12 are −RNA and −RT as negative control and 14 is non-transgenic). The anticipated 1.8-kb product of t-PA transcript is amplified in transgenic plants, But not in −RNA and −RT negative controls

Discussion

Conversion of embryos into plantlets was limited by the number of factors such as low quality, defective in somatic embryos maturation and germination (Choudhary et al. 2009; Rai et al. 2009). So, only mature somatic embryos, containing enough reserved materials such as LEA proteins, fatty acid reserves and sugars, could convert into normal-shaped plants (von Arnold et al. 2002; Sharma et al. 2004). Comparison of seeds, somatic embryos of Medicago sativa L. have relatively low amounts of protein storages (Krochko et al. 1992; Lai et al. 1992) and for conversion to plantlets are dependent on some components. Phytohormones and nitrogen have a positive effect on somatic embryogenesis induction (Shekhawat et al. 2009). Protein content and accumulation of proline are important components which involved in the metabolic process that lead to somatic embryogenesis (Dhir et al. 2014; Dhir and Shekhawat 2014). Therefore, we used the C. campestris extract as supplementary agents to improve embryo maturation, plantlet recovery and transformation. In this research, 50 mg l−1 of C. campestris extract in maturation medium was desired for regeneration of normal somatic embryos and compared to previous reports increased regeneration efficiency of transgenic somatic embryos to 29.3 % (Liu et al. 2013). Matured somatic embryos in medium supplemented with dodder extract had higher fresh weight and size compared to embryos matured in control medium that resulted in higher embryo conversion rate to plantlet. Although components of C. campestris extract which affects the somatic embryo maturation is not known yet, the HPLC analysis indicated that this parasitic plant has a high level of ABA, which could be in accordance with the findings of Furuhashia et al. (2014). They have reported that the content of growth inhibitors, especially free abscisic acid, in C. reflexa is much higher than that of in the host. It has been shown that the conversion of somatic embryos to plantlet was improved by ABA (Vahdati et al. 2008; Rai et al. 2011). Exogenous ABA regulates synthesis of storage proteins in somatic embryos and inhibits the precocious germination of somatic embryos. This growth regulator also could affect the accumulation of some reserves such as total soluble sugar, starch level, and phenols during different stages of somatic embryo development. There are some important ABA-inducible genes such as DcECP31 and AtECP63 which are expressed in the mature stage of somatic embryos and encode LEA proteins (Chugh and Khurana 2002; Ikeda-Iwai et al. 2006). Cuscuta extract also contains some natural nutritional ingredients such as Phytol that may have a role in maturation of somatic embryos. Dodder attracts some proteins and secondary metabolites from host plants using haustoria and acts as a good source of proteins and amino acids. This may be another reason to assume that this extract could be involved in development of somatic embryos. Antimicrobial activity of C. campestris has not been reported till now, but research on C. reflexa extract has shown some antimicrobial activities (Inamdar et al. 2011). In this study, the results demonstrated that extract of C. campestris has an inhibitory effect against some strains of A. tumefaciens. Transformation with Agrobacterium is the prevalent method used for obtaining the genetically modified transgenic plants and Cefatoxime antibiotic is essential for this technique (Tzfira and Citovsky 2006). Use of Cefatoxim in the culture medium affects plant tissue regeneration. Dodder extract not only could act as a source of nutritional agents and plant growth regulators, but also it offers a scientific basis for using C. campestris as a good natural source of antimicrobial compounds and can be used instead of some antibiotic in tissue culture procedure of transgenic plants.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the University of Bu Ali Sina for their financial support (Award Number 19/8/94).

Authors contribution

All authors contributed equally to this work. M. Amini performed tissue culture, H. Saify performed HPLC and GC/MS and data analysis was done by A. Deljou. All authors discussed the results and implications and commented on the manuscript at all stages.

Abbreviation

- ABA

Abscisic acid

- HPLC

High performance chromatography

- GC

Gas chromatography

- MIC

Minimum inhibitory concentration

- MBC

Minimum bactericidal concentration

- LSD

Least significant difference

- tPA

Tissue type plasminogen activator

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Massoume Amini, Email: massoume_amini@yahoo.com.

Ali Deljou, Email: alideljou@yahoo.com.

Haidar Saify Nabiabad, Email: homan_saify@yahoo.com.

References

- Ahmed ABA, Rao AS, Rao MV, Taha RM. Effect of picloram, additives and plant growth regulators on somatic embryogenesis of Phyla nodiflora (L.) Greene. Braz Arch Biol Technol. 2011;54:7–13. doi: 10.1590/S1516-89132011000100002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blaydes DF. Interaction of kinetin and various inhibitors in the growth of soybean tissue. Physiol Plant. 1966;19:748–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1966.tb07060.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary K, Singh M, Rathore MS, Shekhawat NS. Somatic embryogenesis and in vitro plant regeneration in moth bean [Vigna aconitifolia (Jacq.) Marechal]: a recalcitrant grain legume. Plant Biotech Rep. 2009;3:205–211. doi: 10.1007/s11816-009-0093-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chugh A, Khurana P. Gene expression during somatic embryogenesis- recent advances. Curr Sci. 2002;83:715–730. [Google Scholar]

- Dhir R, Shekhawat GS. Production, storability and morphogenic response of alginate encapsulated axillary meristems and genetic fidelity evaluation of in vitro regenerated Ceropegia bulbosa: a pharmaceutically important threatened plant species. Ind Crops Prod. 2013;47:139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2013.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dhir R, Shekhawat GS. Ecorehabilitation and biochemical studies of Ceropegia bulbosa Roxb.: a threatened medicinal succulent. Acta Physiol Plant. 2014;36:1335–1343. doi: 10.1007/s11738-014-1512-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dhir R, Shekhawat GS, Alam A. Improved protocol for somatic embryogenesis and calcium alginate encapsulation in Anethum graveolens L.: A Medicinal Herb. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2014;173:2267–2278. doi: 10.1007/s12010-014-1032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuhashia T, Kojimab M, Sakakibarab H, Fukushimac A, Hiraia MY, Furuhashidv K. Morphological and plant hormonal changes during parasitization by Cuscuta japonica on Momordica charantia. J Plant Interact. 2014;9(1):220–232. doi: 10.1080/17429145.2013.816790. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghazanfari P, Abdollahi MR, Moieni A, Moosavi SS. Effect of plant-derived smoke extract on in vitro plantlet regeneration from rapeseed (Brassica napus L. cv. Topas) microspore-derived embryos. Int J Plant Prod. 2012;6(3):309–324. [Google Scholar]

- Hendra R, Ahmad S, Sukari A, Yunus S, Oskoueian E. Flavonoid analyses and Antimicrobial activity of various parts of Phaleria macrocarpa (Scheff.) boerl fruit. J Mol Sci. 2011;12:3422–3431. doi: 10.3390/ijms12063422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda-Iwai M, Umehara M, Kamada H. Embryogenesis- related genes; its expression and rols during somatic and zygotic embryogenesis in carrot and Arabidopsis. Plant Biotechnol. 2006;23:153–161. doi: 10.5511/plantbiotechnology.23.153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Inamdar FB, Oswal RJ, Chorage TV, Garje K. In vitro antimicrobial activity of Cuscuta reflexa ROXB. Int Res J Pharm. 2011;2(4):214–219. [Google Scholar]

- Jana S, Shekhawat GS. In vitro regeneration of Anethum graveolens, antioxidative enzymes during organogenesis and RAPD analysis for clonal fidelity. Biol Plant. 2012;56(1):9–14. doi: 10.1007/s10535-012-0009-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joshee N, Biswas BK, Yadav AK. Somatic embryogenesis and plant development in Centella asiatica L. a highly prized medicinal plant of the tropics. HortScience. 2007;42:633–637. [Google Scholar]

- Kamonwannasit S, Nantapong N, Kumkrai P, Luecha P, Kupittayanant S, Hudapongse N. Antibacterial activity of aquilariacrassna leaf extract against Staphylococcus epidermidis by disruption of cell wall. J Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2013;12(20):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-12-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkorian AD (2000) Historical insights into some contemporary problems in somatic embryogenesis. In: Jain SM, Gupta PK, Newton RJ (eds) Somatic embryogenesis in woody plants, vol 6. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, pp 17–49. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-3030-3_2

- Krochko JE, Pramanik SJ, Bewley JD. Contrasting storage protein synthesis and messenger RNA accumulation during development of zygotic and somatic embryos of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) Plant Physiol. 1992;99:46–53. doi: 10.1104/pp.99.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai FM, Senaratna T, McKersie BD. Glutamine enhances storage protein synthesis in alfalfa somatic embryos. Plant Sci. 1992;87:69–77. doi: 10.1016/0168-9452(92)90194-Q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Liang Z, Shan C, Marsolais F, Tian L. Genetic transformation and full recovery of alfalfa plants via secondary somatic embryogenesis. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant. 2013;49:17–23. doi: 10.1007/s11627-012-9463-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur S, Shekhawat GS, Batra A. Somatic embryogenesis and plantlet regeneration from cotyledon explants of Salvadora persica L. L Phytomorphol. 2008;58(1–2):57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Nabiabad HS, Yaghoobi MM, Jalali M, Hosseinkhani S. Expression Analysis and purification of human recombinant tissue type plasminogen activator (rtPA) from transgenic tobacco plants. Prep Biochem Biotechnol. 2011;41(2):175–186. doi: 10.1080/10826068.2011.547371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabiabad HS, Piri K, Amini M. Expression of active chimeric-tissue plasminogen activator in tobacco hairy roots, Identification of a DNA aptamer and purification by aptamer functionalized-MWCNTs chromatography. Protein Expr Purif. 2016;41(2):175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedeljko T, Pavle Z, Perica J, Ratomi M, Marina Z. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Daphne cneorum L. J HPLC Anal. 2012;66(5):709–716. [Google Scholar]

- Palikova M, Krejci R, Hilscherova K, Babica P, Navratil S, Kopp R, Blaha L. Effect of different cyanobacterial biomasses and their fractions with variable microcystin content on embryonal development of carp (Cyprinus carpio L.) Aquat Toxicol. 2007;81:312–318. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullman GS, Chopra R, Chase KM. Loblolly pine (Pinus taeda L.) somatic embryogenesis: improvements in embryogenic tissue initiation by supplementation of medium with organic acids, vitamins B12 and E. Plant Sci. 2006;170:648–658. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2005.10.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rai MK, Jaiswal VS, Jaiswal U. Effect of selected amino acids and polyethylene glycol on maturation and germination of somatic embryos of guava (Psidium guajava L.) Sci Hortic. 2009;121:233–236. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2009.01.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rai MK, Asthana P, Jaiswal VS, Jaiswal U. Biotechnological advances in guava (Psidium guajava L.): recent developments and prospects for further research. Trees Struct Funct. 2010;24(1):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00468-009-0384-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rai MK, Shekhawat NS, Harish Amit K, Gupta M, Phulwaria Kheta Ram U. The role of abscisic acid in plant tissue culture: a review of recent progress. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 2011;106:179–190. doi: 10.1007/s11240-011-9923-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rao PS, Suprasanna P. Augmenting plant productivity through plant tissue culture and genetic engineering. J Plant Biol. 1999;26:119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P, Pandey S, Bhattacharya A, Nagar PK, Ahuja PS. ABA associated biochemical changes during somatic embryo development in Camellia sinensis L. J Plant Physiol. 2004;161:1269–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2004.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shekhawat GS, Mathur S, Batra A. Role of phytohormones and nitrogen in somatic embryogenesis induction in cell culture derived from leaflets of Azadirachta indica. Biol Plant. 2009;53(4):707–710. doi: 10.1007/s10535-009-0127-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tayoub G, Abu Alnaser A, Shama M. Microbial inhibitory of Daphne oleifolia. Int J Med Arom Plants. 2012;20(1):161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Teesalu T, Kulla A, Asser T, Koskiniemi M, Vaheri A. Tissue plasminogen activator as a key effector in neurobiology and neuropathology. Biochem Soc Trans. 2002;30(2):183–189. doi: 10.1042/bst0300183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzfira T, Citovsky V. Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of plants: biology and biotechnology. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2006;17(2):147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahdati K, Bayat Sh, Ebrahimzadeh H, Jariteh M, Mirmasoumi M. Effect of exogenous ABA on somatic embryo maturation and germination in Persian walnut (Juglans regia L.) Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 2008;93:163–171. doi: 10.1007/s11240-008-9355-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Von Arnold S, Sabala I, Bozhkov P, Dyachok J, Filonova L. Developmental pathways of somatic embryogenesis. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2002;69:233–249. doi: 10.1023/A:1015673200621. [DOI] [Google Scholar]