Abstract

DNA methylation is a fundamental feature of genomes and is a candidate for pharmacological manipulation that might have important therapeutic advantage. Thus, DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) appear to be ideal targets for drug intervention.

By focusing on interactions existing between DNMT3A and DNMT3A-binding protein (D3A-BP), our work identifies the DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction such as a biomarker whose the presence level is associated with a poor survival prognosis and with a poor prognosis of response to the conventional chemotherapeutic treatment of glioblastoma multiforme (radiation plus temozolomide). Our data also demonstrates that the disruption of DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interactions increases the efficiency of chemotherapeutic treatment on established tumors in mice.

Thus, our data opens a promising and innovative alternative to the development of specific DNMT inhibitors.

Keywords: DNMT, epigenetic, DNA methylation, DNMT, DNMT inhibitor, glioma, GBM.

Introduction

DNA methylation patterns are frequently aberrant in cancer cells 1. Thus, hypomethylation of intergenic regions can occur, leading to tumorigenesis via the activation of transposable elements and increased genomic instability 2-4. Local hypomethylation of genes promoters can promote oncogene expression, while local hypermethylation of the genes promoters can lead to loss of tumor suppressor function in cancer cells 5. Based on this last point, drug development has focused on DNA methylation inhibitors with the goal of activating tumor suppressor genes (TSG) silenced by DNA methylation. But in absence of specificity, a DNMT inhibitor can promote the demethylation of TSG but also of oncogenes and transposable elements. Thus, the use of unspecific DNMT inhibitors can be anti-tumorigenic or pro-tumorigenic. Besides, this last point is illustrated in several articles. Indeed, literature reports that 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine treatment (an unspecific DNMT inhibitor) increased the invasiveness of non-invasive breast cancer cell lines MCF-7 cells and ZR-75-1 and dramatically induced pro-metastatic genes 6. 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine treatment is also reported as an inducer of glioma from astrocytes and as an enhancer of tumorigenic property of glioma cells 7, 8. Nevertheless, 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine is approved by the Food and Drug Administration of the United States for the myelodysplastic syndrome treatment, where it demonstrates significant, although usually transient, improvement in patient survival 9. Despite this undoubtable clinical utility, the dual effect of the use of unspecific DNMT inhibitors provides evidence for the development of specific DNMT inhibitors. In addition, specific DNMT inhibitors could also allow targeting of tumors harboring an aberrant functionality of a particular DNMT. The development of specific DNMT inhibitors could also reduce off-target effects associated with the use of unspecific DNMT inhibitors.

At present, several molecules are developed to specifically target a particular DNMT. Thus, DNMT1 can be inhibited by using RG108, MG98 or Procainamide, DNMT3A while DNMT3B can be specifically inhibited by using Theaflavin 3, 3'-digallate or NanaomycinA, respectively 10-14. To identify these specific DNMT inhibitors, several strategies are developed: the docking-based virtual screening methods, the screening of natural products, the design and generation of derivatives of DNMT inhibitors already known, the molecular modeling of DNMT inhibitors by using crystal structure studies of DNMTs, or the design of siRNA targeting DNMTs 11, 15-19. In a recent article, we demonstrated that DNMT inhibitors can be also addressed against a specific DNMT/protein-x interaction 7.

In the present study, we asked the question to know whether the presence of interaction existing between DNMT3A and a DNMT3A-binding protein (D3A-BP) permit to identify a subpopulation of patients suffering from glioblastoma multiformes (GBM) harboring a shorter overall survival time and whose the glioma cells presented a resistance phenotype to the temozolomide/irradiation treatment. Then, we wanted to know whether it's possible to develop a strategy aiming to specifically inhibit the DNMT3A/D3A-BP interaction associated with a poor prognosis of survival and/or response to the temozolomide/irradiation treatment in order to increase the percentage of the temozolomide+irradiation-induced cell death, and the sensitivity of TMZ in a mice model of gliomagenesis.

Materials and Methods

Patient characteristics

Overall survival was measured from the date of surgical resection to the death. In each tumor grade, all patients included in this study had similar management and similar treatment (including temozolomide (TMZ) for GBM). Patient material as well as records (diagnosis, age, sex, date of death, Karnofsky performance score (KPS)) was used with confidentiality according to French laws and recommendations of the French National Committee of Ethic.

Primary cultured tumor cells (PCTC)

Fresh brain tumor tissues obtained from the neurosurgery service of the Laennec Hospital (Nantes/Saint-Herblain, France) were collected and processed within 30 min after resection. The clinical protocol was approved by the French laws of ethics with informed consent obtained from all subjects. The primary cultured tumor cells were obtained after mechanical dissociation according to the technique previously described 20. Briefly, tumor tissue was cut into pieces of 1-5 mm3 and plated in a 60 mm2 tissue culture dish with DMEM with 10% FBS and antibiotics. Additionally and in parallel, minced pieces of tumor were incubated with 200 U/ml collagenase I (Sigma, France) and 500 U/ml DNaseI (Sigma, France) in PBS during 1 hr at 37 °C with vigorous constant agitation. The single-cell suspension was filtered through a 70 mm cell strainer (BD Falcon, France), washed with PBS, and suspended in DMEM-10% FBS. Cell cultures were subsequently split 1:2 when confluent and experiments were done before passage 3-5.

Proximity Ligation In Situ Assay (P-LISA)

Cells were cultured for 24h on cover slip. Cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS pH7.4 for 15min at room temperature. Permeabilization is performed with PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 for 20min at room temperature. Blocking, staining, hybridization, ligation, amplification and detection steps were realized according to manufacturer's instructions (Olink Bioscience, Sweden). All incubations were performed in a humidity chamber. Amplification and detection steps were performed in dark room. Fluorescence was visualized by using the Axiovert 200M microscopy system (Zeiss, Le Pecq, France) with ApoTome module (X63 and numerial aperture 1.4). Preparations were mounted by using ProLong® Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Life Technologies, France). Pictures acquisition was realized in structured illumination microscopy 21. After decovolving (3.5 Huygens Essential software (SVI)), 3D view was obtained by using Amira.4.1.1 program. Finally, the images were analyzed by using the freeware “BlobFinder” available for download from www.cb.uu.se/~amin/BlobFinder. Thus, we obtained either number of signals per nuclei since nuclei can be automatically identified.

Epitope mapping

Peptides were spotted on an Amino-PEG500-UC540 membrane using a MultiPep peptide synthesizer (Intavis AG, Cologne, Germany) at a loading capacity of 400 nmol/cm2. After synthesis the membrane was dried then the capped side-chains were deprotected by cleavage for 1h with a cocktail containing 95% trifluoroacetic acid, 3% tri-isopropyl, 2% H2O. The trifluoroacetic acid was removed and the membrane rinsed with dichloromethane, followed by dimethylformaldehyde and then ethanol. The membrane was saturated before incubation with the considered recombinant protein for 2h at room temperature. After which, it was washed three times, positive peptides were revealed using antibodies coupled to a fluorochrome. Typhoon (GE Healthcare, France) was used to determine fluorescence. The binding intensities of the considered recombinant protein for the spotted peptides were determined by quantification using ImageJ software and converted to sequence-specific normalized units. The intensities obtained for each peptide covering a given amino acid were added and divided by the number of peptides.

Pull-down assay

Pull-down assays were performed by using the GST/His Tagged-Protein Interaction Pull-Down Kits (Thermo Scientific, France). Briefly, 100μg of bait protein were immobilized on column via an incubation at 4°C for 1h with gentle mixing. After washing, 1μg of prey protein was added for 1h at 4°C with gentle rocking motion on a rotating platform. After washes and elution, the “bait-prey” interaction was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot methods. Competitive pull-down experimentations were realized by pre-incubating considered peptides for 1h at 37°C.

Western blot analysis

In brief, proteins were size fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose or PVDF membrane. Saturation and blotting were realized by using SNAP i.d™ Protein Detection System (Millipore, France). The detection of proteins was performed using ECL™(Amersham Biosciences, France) and/or SuperSignal west femto Maximum Sensitivity (Thermo Scientific, France) chemilumenscence reagents. The detection of proteins was performed using the FusionX7 Imager (Fisher Scientific, France).

Transfer of peptides into cells via electroporation

For electroporation, NLS sequence was added to peptides. Cells were harvested during the exponential growth phase by trypsinization and were resuspended in their original media. They were washed in PBS, pH 7.2 (0.14 M NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 8 mM Na2HPO4 and 1.5 mM NaH2PO4) and resuspended at a concentration of 0.6x106 cells/ml in original culture medium. Next, 0.8 ml of the cell suspension was mixed with the peptides (50μg/ml), allowed to stand at room temperature for 10 min and added to a disposable 0.4 cm Bio-Rad electroporation cuvette (Bio-Rad, France). An equivalent volume of DMSO was added to a cell suspension without peptide for use as a control (also named untreated). Electroporation efficiency for each cell line was initially determined by flow cytometry by uptake of the fluorescent dye, lucifer yellow (Sigma, France). Electroporation was carried out in a Gene-Pulser (Bio-Rad, France) with cells exposed to one pulse. The following parameters were used: cuvette gap 0.4 cm, voltage 0.3 kV, time constant 35 ms, and capacitor 960 μF. Following electroporation, cells were allowed to recover by standing at room temperature for 10 min, then removed from the electroporation chamber, washed twice in PBS and resuspended in 2 ml of original culture medium.

Measure of global DNA methylation

DNA was extracted by using the QiaAmp DNA mini Kit (Qiagen, France). Next, global DNA methylation was estimated by quantifying the presence of 5-methylcytosine using Methylamp Global DNA methylation Quantification kit (Euromedex-Epigentek, France) according to the manufacturers's instructions.

Measure of Cell Death

Percentages of cell death were evaluated by using a Trypan Blue Stain 0.4%, and the Countess® Automated Cell Counter (Life Technologies, France). Cell death was induced using temozolomide (25μM) and irradtiation (2 Gy) such as previously described 7.

Proliferation assay and doubling time

Doubling time (i.e. the period of time required for a quantity to double in size) was calculated by using the Doubling Time Online Calculator website (Roth V. 2006, http://www.doubling-time.com/compute.php) and counting the proliferation of 103 cells over 120 hours. Cell number was determined, every 24h over 120h, using the Countess™ Automated Cell Counter (Life Technologies, France).

Migration assay - Scratch test

Cell migration assay was performed using a scratch technique. Cells were plated in 6-well plates at 80-90%, and were treated with 10 μg/ml mitomycin C (Sigma, Farnce) for 2 hours (in order to remove the influence of cell proliferation). Cells were then scratched. Cell migration was monitored by microscopy. The images acquired for each sample were analyzed quantitatively. For each image, distances between one side of scratch and the other were measured. By comparing the images from time 0 to the last time point (24 hours), we obtain the distance of each scratch closure on the basis of the distances that are measured.

Invasion Assay

All of the procedures were followed according to the manufacturer's instructions (QCM 24-Well Collagen-Based Cell Invasion Assay, Millipore, France). In brief, 200 μl serum-free medium containing 2×105 cells were seeded into the invasion chamber and placed into the 24 well plate containing 500 μl complete medium. After 72 h incubation at 37°C, media was removed from the chamber, and cells were stained by putting the chamber in staining solution for 20 min at room temperature. Non-invaded cells were carefully removed from the top-side of the chamber. Stained chamber was inserted into a clean well containing 200 μl of extraction buffer for 15 min at room temperature. 100 μl extracted stained solution from the chamber was transferred into the 96 well plate and optical density was measured at 560 nm with a spectrophotometer.

Tumorigenicity assay

Cultured cells were harvested by trypsinization, washed and resuspended in saline buffer. Cell suspensions were injected s.c. as 2.106 cells in 0.05 ml of PBS with equal volume of matrigel matrix (Becton Dickinson, France) in the flank of 7/8-week-old Nude NMRI-nu female mice (Janvier, France). After tumor establishment, mice were treated with temozolomide and/or peptides via intra-tumor injection (it). To obtain tumor weigh, each tumor was surgically removed and is weighed. All experimental procedures using animals were realized in accordance with the guidelines of Institutional Animal Care and the French National Committee of Ethics.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were done at least in triplicates. Significance of the differences in means was calculated using Student-t test. Survival curves were plotted according to Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the Cox proportional hazards survival regression analysis (such as indicated on the corresponding figures). Significance of correlation between two parameters was calculated using Pearson's test.

Results

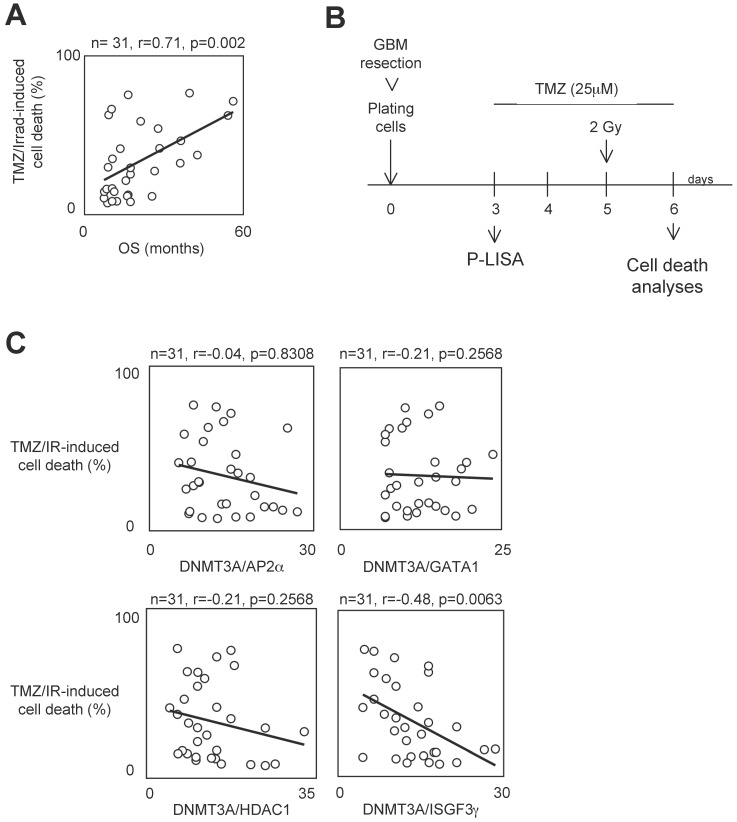

A high level of DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction correlates with a poor level of sensitivity to temozolomide/irradiation-induced cell death

To determine whether the presence of interaction between DNMT3A and a DNMT3A-binding protein (D3ABP) could permit to identify a subpopulation of GBM patients whose the glioma cells harbor a phenotype of resistance to the temozolomide/irradiation treatment, we have established 31 primary cultured tumor cells (PCTCs) from patient-derived biopsies. Then, these PCTC were used to evaluate the putative correlation between the number of certain DNMT3A/D3A-BP interactions and the temozolomide/irradiation-induced (TMZ/IR-induced) cell death percentage (Figure 1A). In our study, we focused on the DNMT3A/HDAC1, DNMT3A/AP2α, DNMT3A/GATA1 and DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction since we and other have already demonstrated their existence 22, 23. Proximity Ligation In Situ Assay (P-LISA) was used to monitor the interaction of interest. The TMZ/IR-induced cell death percentage was estimated by using trypan blue method (Figure 1B). The number of DNMT3A/D3A-BP interactions of interest and the TMZ/IR-induced cell death percentage were plotted against each other (Figure 1C). Statistical analysis using Pearson's correlation test showed a significant and inverse correlation only between the number of DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interactions and the TMZ/IR-induced cell death percentage (p=0.002) (Figure 1C). These results suggested that DNMT3A/ISGF3γ could play a crucial role in the poor response prognosis of glioma cells to the TMZ/IR treatment.

Figure 1.

A high level of DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction correlates with a poor level of sensitivity to temozolomide/irradiation-induced cell death. A. Graph illustrates the correlation existing between the overall survival (OS) of 31 GBM patients and the percentage of temozolomide/irradiation-induced cell death (TMZ/Irrad-induced cell death) of primary cultured tumor cells (PCTC) issue to the corresponding GBM. A circle represents a couple patient/PCTC issues from the considered patient. p and r values were obtained by performing a Pearson's test. B. Schematic representation of the temozolomide/irradiation-induced cell death. C. Graph illustrates the existing correlation between the percentage of temozolomide/irradiation-induced cell death and the number of DNMT3A/D3A-BP interaction of interest. The number of DNMT3A/D3A-BP interaction was estimated by P-LISA. A circle represents a PCTC. p and r values were obtained by performing a Pearson's test.

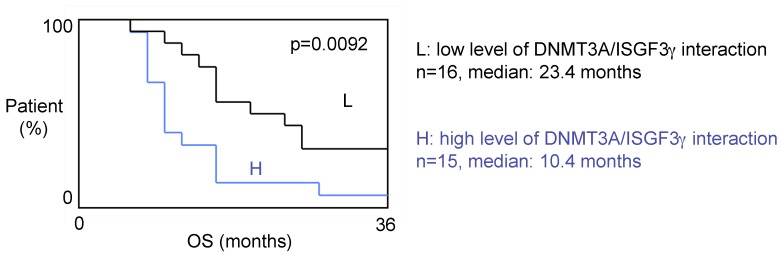

A high level of DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction is a poor prognosis factor

The 31 patients were divided into two groups based on the DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction levels found on their tumor biopsies. Tumors from 15 patients expressed high levels of DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction (higher than the median of DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction, 12.5), while 16 patients had a DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction equal to or lower than 12.5. Overall survival curves were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared with the Cox Proportional Hazards Survival Regression Analysis (Figure 2A). A significant difference was observed in overall survival (p=0.0092) between patients whose tumors had high levels of DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction and those whose tumors did not. These data indicate that a high level of DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction is a poor prognosis factor.

Figure 2.

A high level of DNMT3A/ISGF3g interaction is a poor prognosis factor. Kaplan-Meier curves illustrate the difference of overall survival (OS) between patient with high (H) and low (L) levels of DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction. p value is obtained by performing a Cox Proportional Hazards Survival Regression test.

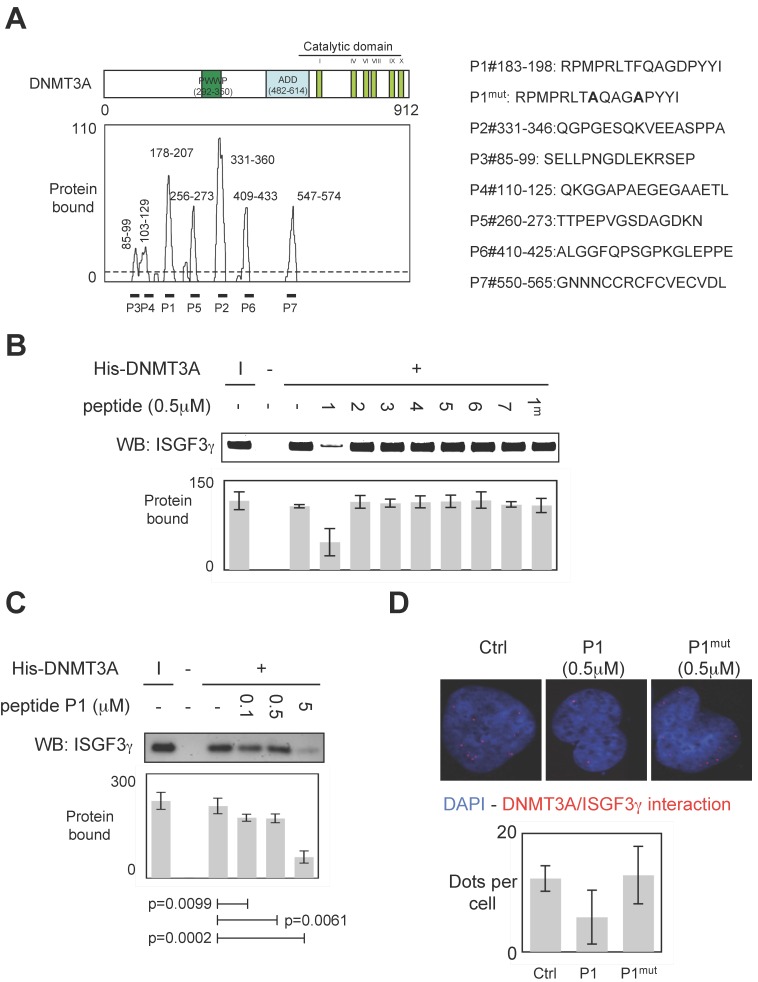

Specific disruption of DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction

The double fact that high level of DNMT3a/ISGF3γ interaction was associated with a poor response prognosis to the temozolomide/irradiation treatment and was associated with of poor prognosis of overall survival, suggest that DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction could be used as a therapeutic target.

To develop a therapeutic strategy aiming to inhibit the DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction, we performed a set of experiments aiming to characterize the DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction. In this set of experiments, epitope mapping analysis was performed to identify the amino acids region of DNMT3A interaction with ISGF3γ. Thus, the primary sequence of DNMT3A was decomposed into 12-mer peptides overlapping by 10 residues covalently bound to a nitrocellulose membrane. Two negative controls were performed to observe that neither the incubation of GST protein (2μg) nor the use of antibodies against ISGF3γ induced the detection of positive peptides (Figure S1). Then, 2μg of GST-ISGF3γ protein were incubated with the membrane. The positive peptides for an interaction with GST-ISGF3γ were then detected by using Thyphoon and antibodies directed against ISGF3γ (Figure S1). After fluorescence quantification, the sequences of amino acids of DNMT3A interacting with GST-ISGF3γ were determined (Figure 3A). Thus, we observed that the sequences 85-99, 103-129, 178-207, 235-246, 256-273, 331-360, 409-433 and 547-574 were implicated in the DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction.

Figure 3.

Specific disruption of DNMT3a/ISGF3γ interaction. A. Graph illustrates the binding intensities of GST-ISGF3γ for DNMT3A-derived peptides after quantification using ImageJ software as described in material and methods section and in figure S1. The binding regions were shown on the schematic representation of the DNMT3A protein. The sequence of DNMT3A-derived peptides used to challenge the DNMT3A /ISGF3γ interactions was here shown. B and C. Impact of peptides miming the DNMT3A/ISGF3γ binding regions on the DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction. Pictures and graphs are representatives of three independent pull-down experiments. I: input. Sequences of DNMT3A-derived peptides are shown in figure 3A. p values were obtained by performing a t test. D. Impact of peptides miming the DNMT3A/ISGF3γ binding regions on the DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction. Pictures and graphs are representatives of three independent P-LISA experiments. Red dots represent the DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interactions or close proximity. Graph illustrates three independent experiments. p values were obtained by performing a t test.

To validate the implication of these amino acid domains on the DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction, we derived peptides from these domains in order to test the ability of these peptides to inhibit the DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction in a pull-down assay (Figure 3A). We thus noted that only P1 inhibited the DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction (Figure 3B). The efficiency of P1 to inhibit the DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction was also reinforced by the fact that 1) a mutated P1 peptide (P1mut) does not inhibit the DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction (Figure 3B) and 2) DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction decreased in presence of increasing concentration of P1 peptide (Figure 3C).

Proximity Ligation In Situ Assays (P-LISA) were next used to monitor the DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interactions in cells. For these experiments, we used a PCTC (named PCTC#1). Electroporation was used to transfect P1 in cells. P-LISA were performed 12 hr after electroporation. Thus, we noted that red dots representing the DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interactions decreased when cells were treated with the P1 and not in presence of P1mut (Figure 3D).

All these results indicated that P1 peptide induced the disruption of DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interactions.

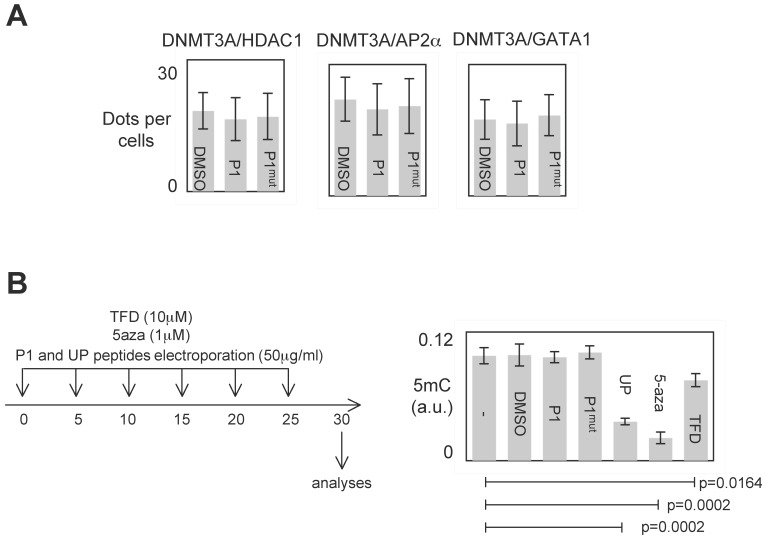

Specific effect of P1 peptide

P1 was designed to inhibit the DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interactions. However, P1 could also affect other interaction existing between DNMT3 and a D3A-BP. To investigate this point, we analyzed the effect of P1 on the DNMT3A/D3A-BP interactions of interest. As illustrated by the figure 4A, we noted that P1 has no effect on the integrity of the DNMT3A/GATA1, DNMT3A/AP2α and DNMT3A/HDAC1 interactions in PCTC#1.

Figure 4.

Specific effect of P1. A. Graph illustrates the fact that P1 did not affect the DNMT3A/AP2α, DNMT3A/GATA1 and DNΜΤ3Α/HDAC1 interactions. p values were obtained by performing a t test. B. Representation of the dose-schedule of treatments (left). Graph (right) illustrates the fact that P1 did not affect the global DNA methylation level. Global DNA methylation level was monitored by ELISA using Methylamp Global DNA methylation Quantification kit (Euromedex-Epigentek, France). p values were obtained by performing a t test.

The analysis of all interactions being impossible, we postulated that if P1 inhibited a large number of DNMT3A/D3A-BP interactions, an hypomethylation phenotype would be observable. To observe the putative P1-induced DNA hypomethylation, PCTC#1 were treated during 30days with P1 (Figure 4B). Other DNMT inhibitors (5-aza-2-deoxycytidine (5-aza), theaflavin 3,3 digallate (a DNMT3A inhibitor 14, hereafter called TFD), or peptides (UP peptide, a peptide inhibiting the DNMT1/PCNA/UHRF1 interactions, 3)) were also used as control conditions. ELISA monitoring the global level of 5-methylcytosine revealed that P1 had not effect on the global level of 5-methylcytosine, while the 5-aza, TFD and UP treatments decreased the global level of DNA methylation (Figure 4B).

Based on these data, we conclude that P1 seems to be specific for disrupting the DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction and without promoting global DNA hypomethylation.

Impact of P1 peptide on cancer hallmarks/phenotypes

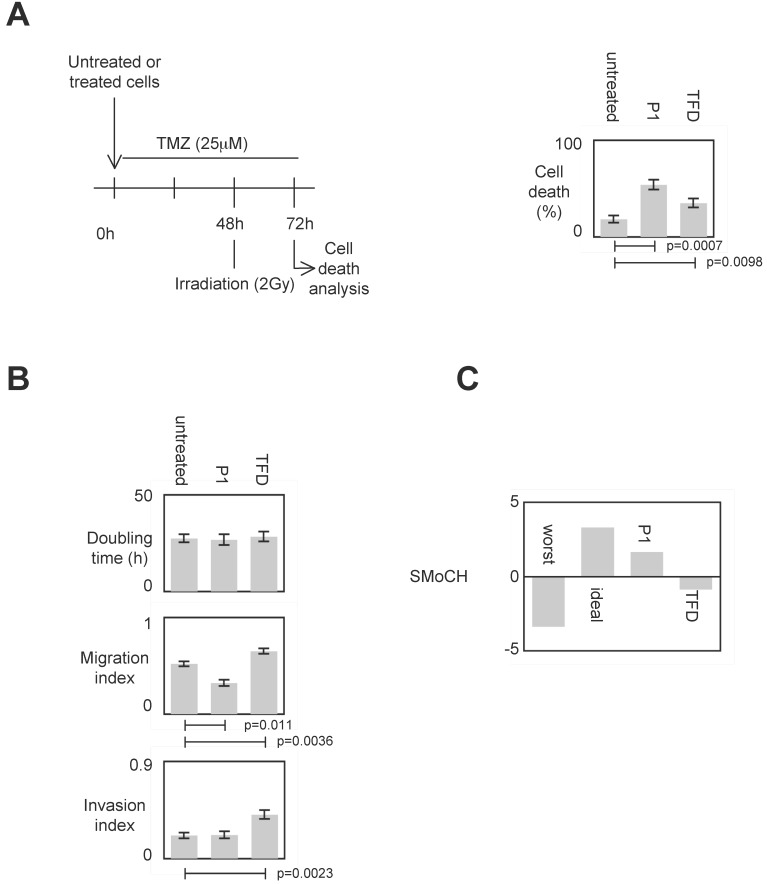

We then determined the impact of the P1-induced disruption of the DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interactions on several cancer hallmarks/phenotypes including proliferation level, invasion, migration and evasion of apoptosis (or more particularly the sensitivity of apoptosis induced by a therapeutic treatment). For this purpose, cells were treated by P1 and TDF such as previously described in figure 4B.

To evaluate the impact of the P1-induced disruption of the DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interactions on the sensitivity of apoptosis induced by a therapeutic treatment, we measured the percentage of temozolomide+irradiation-induced cell death since temozolomide (TMZ) and irradiation are conjugated in anti-GBM treatment 7, 24. Figure 5A shows that the percentage of cell death of P1 and TDF treated cells increased, and the percentage of cell death of P1treated cells was higher than the one obtained withTDF.

Figure 5.

Impact of P1 on cancer hallmarks/phenotypes. A. Schematic representation of the temozolomide/irradiation-induced cell death. Percentages of cell death were evaluated by using a Trypan Blue Stain 0.4%, and the Countess® Automated Cell Counter (Life Technology, France). p values were obtained by performing a t test. B. Doubling time (i.e. the period of time required for a quantity to double in size) was calculated by using the http://www.doubling-time.com/compute.php website and counting the proliferation of 103 cells during 120 hours. Migration index was calculated by performing a scratch test. Invasion index was estimated by using cell invasion assay according to the manufacturer's instructions (Millipore, France). Graphs illustrate the average±SD of 3 independent experiments. p values were obtained by performing a t test. C. Score of Modulation of Cancer Hallmarks (SMoCH) was calculated by attributing -1 when the peptide/treatment enhanced a cancer hallmark, 0 when peptide/treatment did not modify a cancer hallmark and +1 when the peptide/treatment inhibited a cancer hallmark. By taking into consideration 4 cancer hallmarks/phenotypes, a worst anticancer treatment theoretically obtains SMoCH=-4, while an ideal anticancer treatment theoretically obtains SMoCH=+4.

To estimate the impact of the P1-induced disruption of DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interactions on proliferation, we calculated the doubling time. We found that both P1 and TFD treatments have no effect on the doubling time of cells (Figure 5A).

Impact of the P1-induced disruption of the DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interactions on migration capability was next estimated by performing a scratch test assay. Figure 5A indicates that P1 treatment decreased cell migration while TFD treatments had no effect on cell migration.

Impact of the P1 and TFD treatments on cell invasion was next estimated by performing a collagen-based cell invasion assay. Figure 5A indicates that P1 unmodified the cell invasion characteristic, while TDF treatment promoted the cell invasion.

To summarize these data, we created and calculated the Score of Modulation of Cancer Hallmarks (SMoCH) by attributing -1 when the peptide/treatment enhanced a cancer hallmark, 0 when peptide/treatment did not modify a cancer hallmark and +1 when the peptide/treatment inhibited a cancer hallmark. Thus, a positive SMoCH suggests that the considered peptide/treatment inhibits more cancer hallmarks than it promotes them, so the benefit/risk balance is favorable for using the considered peptide/treatment in anticancer therapy. Figure 5B indicating that P1 treatment is in this situation, we concluded that P1 treatment could be efficient in anti-cancer therapy.

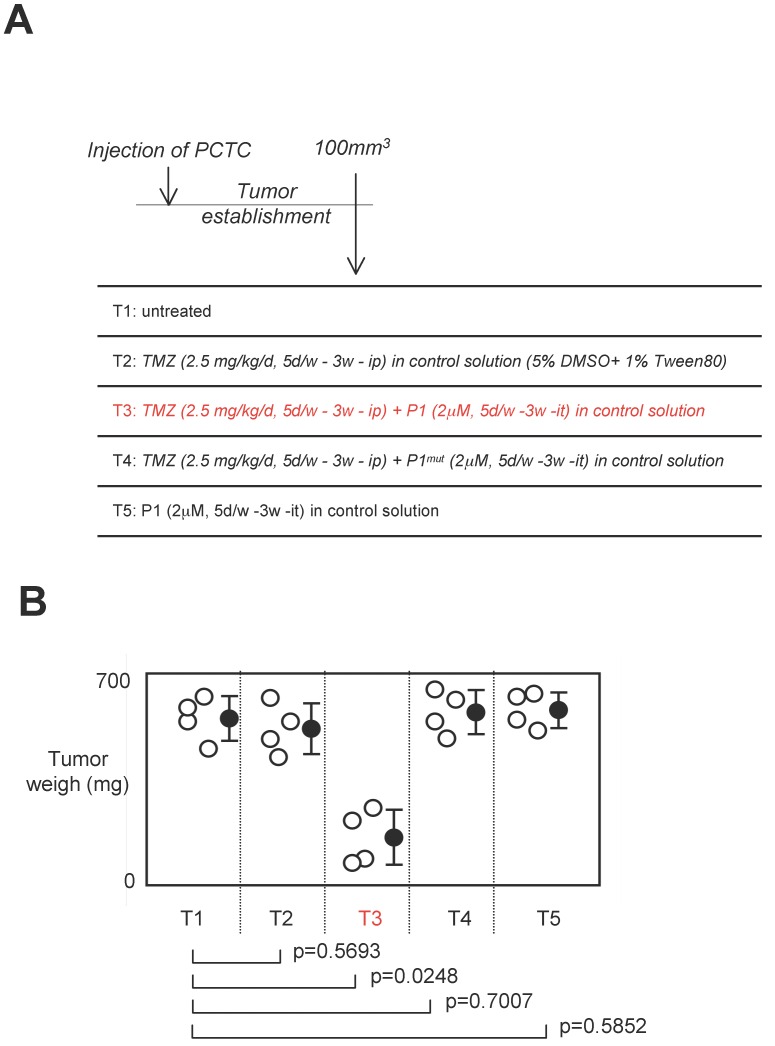

Effect of a treatment associating P1 peptide with TMZ in a swiss nude mice model of established tumors

Standard anti-GBM treatment using temozolomide as chemotherapeutic agent, we next investigated the effect of a treatment associating P1 peptide with TMZ in a swiss nude mice model of established tumors 24. For this purpose, 16 swiss Nude mice were injected subcutaneouly by 2.106 glioma cells (having high level of DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interactions (Figure 6A). Next, when the tumor volume was equal to 100mm3, 4 mice were randomly untreated, treated with TMZ, TMZ+P1, TMZ+P1mut or P1 (called T1 and T5 respectively). After 3 weeks of treatment, we noted that TMZ treatment was inefficient to limit tumor growth since no statistical difference was observed between untreated mice and mice treated with TMZ only, and between untrated mice and mice treated with P1 (Figure 6B). More interestingly, we noted that the TMZ+P1 treatment reduced tumors volumes, while the TMZ+P1mut treatment is inefficient to reduce tumor growth. Thus, our data indicated that the use of P1 with TMZ promoted the TMZ-induced reduction of tumor growth.

Figure 6.

Effect of a treatment associating the P1 peptide with TMZ in a swiss nude mice model of established tumors. A. Design of the experiment. Tumor establishment indicates that 2.106 PCTC-GBM were injected to form a tumor of which the volume was equal to 100mm3±33.3. Then, mice were treated with indicated treatment. D: day, w: week, it: intra-tumoral, ip: Intraperitoneal. B. Graph illustrates the impact of the 4 considered treatments on tumor weight of established tumors. Open circles represent mice. Black circles represent the average±standard deviation obtained for each treatment. p values were obtained by performing a t test.

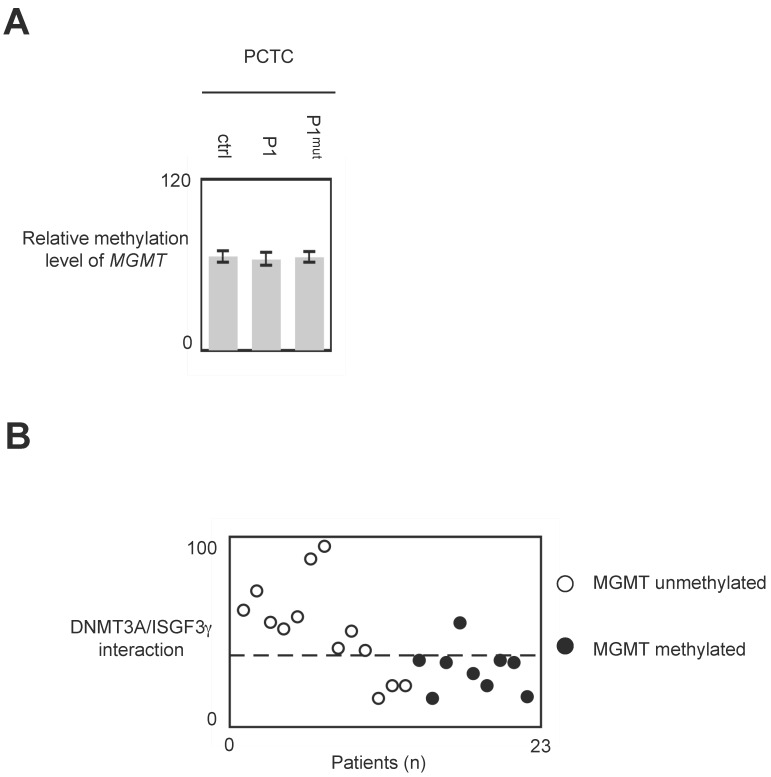

The use of P1 peptide does not promote global DNA hypomethylation and MGMT demethylation

In glioma, MGMT methylation is associated with a good responsive of anti-glioma treatment including TMZ and irradiation 25, 26. Thus, we have analyzed whether the use of P1 could modulate the methylation level of MGMT. qMSP experiment indicated that the methylation level of MGMT remains unchanged when cells were treated with P1 (Figure 7A and 7B.)

Figure 7.

Impact of P1 treatment on MGMT methylation. Cells were treated with P1 as described in figure 4. qMSP were next performed to analyze the MGMT methylation status as described previously. p values were obtained by performing a t test.

Discussion

Recent reports focused on the DNMT inhibitors (DNMTi) identification have provided meaningful progress in the strategy used to design, synthesize and use DNMTi 27-30. Indeed, the inhibition of DNA methyltransferases (DNMT) represent an interesting therapeutic challenge since aberrant hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes can be reverted by inhibition of DNMTs. However, the inadequate use of DNMTi can also induce the demethylation of oncogenes, of genes involved in therapeutic resistance, or promote the phenotype of global DNA hypomethylation that several publications defined as being an oncogenic event. Despite the undoubtable effect of certain global DNMTi in certain cancer, the unspecific action and the dual targeting of DNMTi (tumor suppressor genes and oncogenes) asked the question of the strategy to design it. Recently, we and others have begun to unveil that the use of DNMTi could promote tumorigenicity from non tumor cells and/or increase the tumorigenicity of tumor cells 6-8. Thus, an ideal DNMTi must be targeted against a DNMT-including complex 1) involved in the hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes without being involved the hypermethylation of oncogenes and DNA repeat elements (i.e. in two methylation signatures whose the loss promotes the tumorigenesis), or 2) whose the presence is associated with a pejorative prognosis of survival or response to an anti-cancer therapy. The identification, in this study, of the DNMT3A/ISGF3γ complex answers to this last point and introduce the development of DNMTi in a theranostic approach. Concerning our study, the development of DNMTi in a theranostic approach provides P1 as a therapeutic tool and the DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction level as a biomarker for diagnosis and/or patient stratification.

Among the four DNMT3A/D3A-BP interactions monitored in our study, only the DNMT3A/ISGF3γ was identified as being a biomarker associated with a poor response prognosis to TMZ-IR treatment. Consequently, this result could suggest that levels of DNMT3A/HDAC1, DNMT3A/AP2α, and DNMT3A/GATA1 interactions are not associated with the poor response of TMZ-IR-induced cell death. Our results also suggest that DNMT3A/ISGF3γ-including complex are involved in the epigenetic regulation of genes encoding for protein directly or indirectly implicated in the phenotype of resistance to the TMZ-IR-induced cell death. Preliminary data indicated that DNMT3A/ISGF3γ-including complexes are involved, in certain cells, in the hypermethylation-induced silencing of bax (data not shown) 31.

In glioma, the global DNA hypomethylation level is associated with tumor grade (i.e. the aggressiveness) and poor survival, and MGMT methylation is associated with a good responsive of anti-glioma treatment including TMZ and irradiation 3, 25, 26, 32, 33. Consequently, DNMTi promoting global DNA hypomethylation and/or MGMT demethylation appear unsuited to treat glioma. Our data indicated that P1 did not affect the global DNA and MGMT methylation status. Thus, conjugated with the fact that P1 did not promote or enhance cancer hallmark, it appears that P1 is an interesting compound to treat glioma. More interestingly, our data underline the fact that GBM patients whose PCTC have high level of DNMT3A/ISGF3γ interaction level are GBM patients having an unmethylated MGMT gene i.e. GBM patients having a poor predisposition to favorably reply to the TMZ/irradiation treatment (since it is GBM patients characterized by a methylated MGMT gene that are predisposed to reply to the TMZ/irradiation treatment). Thus, the use of P1 in therapy treating patients characterized by an unmethylated MGMT gene appears as a promising alternative to increase the sensitivity of this sub-group of patients to the TMZ/irradiation treatment.

Among the distinct strategies aiming to develop anti-GBM treatment, we have focused our work on the development of peptides able to disrupt/inhibit specific interaction existing between DNMT3A and a D3A-BP, and whose the high presence in glioma is associated with a poor survival and response prognosis to anti-glioma therapy. By establishing this strategy of DNMTi development, we are aware that this requires the identification of specific DNMT/D-BP interactions whose the presence in tumor (here, in GBM) was associated with an unfavorable prognosis for survival i.e. intensive work of translational research. However, this approach has the advantage to register in the context of personalized medicine in which the detection of the DNMT/D-BP interactions identifies a patient for a specific therapeutic prescription (P1 and TMZ, as example). Thus, better than the development of DNMT inhibitors using crystallographic structure of DNMT, molecular modeling and virtual screening of DNMT inhibitors, the synthesis of DNMTi derivates already existing, the monitoring of natural products, or the use/design of siRNA targeting DNMTs, our approach take into consideration rational biomarker issue to a pathology of interest 15-19, 28, 34, 35. For all these reasons, the development of DNMTi based on the inhibition/disruption of interaction existing between a DNMT and a DNMT-binding protein appears as a promising approach to design successful therapeutic protocols based on rational molecular targeting and on personalized medicine.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary tables and figures.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from “Ligue Contre le Cancer, committees of Loire-Atlantique, Maine et Loire and Vendée (AO2012-Subvention2013)”. MC was supported by a fellowship from Cancéropole Grand Ouest/Région Pays de la Loire. We also thank “En Avant la Vie” (an association supporting the patients suffering from gliomas and their family, and the research on glioma field) for the funding of the Bioruptor plus sonicator (Diagenode).

References

- 1.Esteller M. Epigenetics in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1148–59. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eden A, Gaudet F, Waghmare A, Jaenisch R. Chromosomal instability and tumors promoted by DNA hypomethylation. Science. 2003;300:455. doi: 10.1126/science.1083557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hervouet E, Debien E, Cheray M, Hulin P, Loussouarn D, Martin SA. et al. Disruption of Dnmt1/PCNA/UHRF1 interactions promotes tumorigenesis by inducing genome and gene-specific hypomethylations and chromosomal instability. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11333. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toraño E, Petrus S, Fernandez A, Fraga M. Global DNA hypomethylation in cancer: review of validated methods and clinical significance. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2012;50:1733–42. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2011-0902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukushige S, Horii A. DNA methylation in cancer: a gene silencing mechanism and the clinical potential of its biomarkers. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2013;229:173–85. doi: 10.1620/tjem.229.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chik F, Szyf M. Effects of specific DNMT gene depletion on cancer cell transformation and breast cancer cell invasion; toward selective DNMT inhibitors. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:224–32. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheray M, Pacaud R, Nadaradjane A, Vallette F, Cartron PF. Specific inhibition of one DNMT1-including complex influences the tumor initiation and progression. Clinical Epigenetics. 2013;5:9. doi: 10.1186/1868-7083-5-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheray M, Nadaradjane A, Bonnet P, Routier S, Vallette F, Cartron P. Specific inhibition of DNMT1/CFP1 reduces cancer phenotypes and enhances the chemotherapy effectiveness. Epigenomics. in revision. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Issa J. Optimizing therapy with methylation inhibitors in myelodysplastic syndromes: dose, duration, and patient selection. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2005;2:S24–9. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amato R, Stephenson J, Hotte S, Nemunaitis J, Bélanger K, Reid G. et al. MG98, a second-generation DNMT1 inhibitor, in the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Invest. 2012;30:415–21. doi: 10.3109/07357907.2012.675381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuck D, Singh N, Lyko F, Medina-Franco J. Novel and selective DNA methyltransferase inhibitors: Docking-based virtual screening and experimental evaluation. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18:822–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuck D, Caulfield T, Lyko F, Medina-Franco J. Nanaomycin A selectively inhibits DNMT3B and reactivates silenced tumor suppressor genes in human cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:3015–23. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee B, Yegnasubramanian S, Lin X, Nelson W. Procainamide is a specific inhibitor of DNA methyltransferase 1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40749–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505593200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rajavelu A, Tulyasheva Z, Jaiswal R, Jeltsch A, Kuhnert N. The inhibition of the mammalian DNA methyltransferase 3a (Dnmt3a) by dietary black tea and coffee polyphenols. BMC Biochem. 2011;21:12–6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-12-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Medina-Franco J, López-Vallejo F, Kuck D, Lyko F. Natural products as DNA methyltransferase inhibitors: a computer-aided discovery approach. Mol Divers. 2011;15:293–304. doi: 10.1007/s11030-010-9262-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki T, Tanaka R, Hamada S, Nakagawa H, Miyata N. Design, synthesis, inhibitory activity, and binding mode study of novel DNA methyltransferase 1 inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:1124–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoo J, Kim J, Robertson K, Medina-Franco J. Molecular modeling of inhibitors of human DNA methyltransferase with a crystal structure: discovery of a novel DNMT1 inhibitor. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2012;87:219–47. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-398312-1.00008-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoo J, Medina-Franco J. Inhibitors of DNA methyltransferases: insights from computational studies. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19:3475–87. doi: 10.2174/092986712801323289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Venza M, Visalli M, Catalano T, Fortunato C, Oteri R, Teti D. et al. Impact of DNA methyltransferases on the epigenetic regulation of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) receptor expression in malignant melanoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;441:743–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.10.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Beusechem V, Grill J, Mastenbroek D, Wickham T, Roelvink P, Haisma H. et al. Efficient and selective gene transfer into primary human brain tumors by using single-chain antibody-targeted adenoviral vectors with native tropism abolished. J Virol. 2002;76:2753–62. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.6.2753-2762.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaefer L, Schuster D, Schaffer J. Structured illumination microscopy: artefact analysis and reduction utilizing a parameter optimization approach. J Microsc. 2004;216:165–74. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2720.2004.01411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuks F, Burgers W, Godin N, Kasai M, Kouzarides T. Dnmt3a binds deacetylases and is recruited by a sequence-specific repressor to silence transcription. EMBO J. 2001;20:2536–44. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.10.2536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hervouet E, Vallette FM, Cartron PF. Dnmt3/transcription factor interactions as crucial players in targeted DNA methylation. Epigenetics; 2009. p. 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Louis D, Ohgaki H, Wiestler O, Cavenee W, Burger P, Jouvet A. et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Esteller M, Garcia-Foncillas J, Andion E, Goodman SN, Hidalgo OF, Vanaclocha V. et al. Inactivation of the DNA-repair gene MGMT and the clinical response of gliomas to alkylating agents. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1350–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011093431901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hegi M, Diserens A, Gorlia T, Hamou M, de Tribolet N, Weller M. et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:991–1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foulks J, Parnell K, Nix R, Chau S, Swierczek K, Saunders M. et al. Epigenetic drug discovery: targeting DNA methyltransferases. J Biolmol Screen. 2012;17:2–17. doi: 10.1177/1087057111421212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fahy J, Jeltsch A, Arimondo P. DNA methyltransferase inhibitors in cancer: a chemical and therapeutic patent overview and selected clinical studies. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2012;22:1427–42. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2012.729579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li K, Li F, Li Q, Yang K, Jin B. DNA methylation as a target of epigenetic therapeutics in cancer. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2013;13:242–7. doi: 10.2174/1871520611313020009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Medina-Franco J, Yoo J. Molecular modeling and virtual screening of DNA methyltransferase inhibitors. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19:2138–47. doi: 10.2174/1381612811319120002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cartron PF, Juin P, Oliver L, Martin S, Meflah K, Vallette F. Nonredundant role of Bax and Bak in Bid-mediated apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:4701–12. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.13.4701-4712.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hervouet E, Debien E, Charbord J, Menanteau J, Vallette FM, Cartron PF. Folate supplementation: a tool to limit the aggressiveness of gliomas via the re-methylation of DNA repeat element and genes governing apoptosis and proliferation. Clinical Cancer Research. 2009;15:3519–29. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zukiel R, Nowak S, Barciszewska A, Gawronska I, Keith G, Barciszewska M. A simple epigenetic method for the diagnosis and classification of brain tumors. Mol Cancer Res. 2004;2:196–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Medina-Franco J, Caulfield T. Advances in the computational development of DNA methyltransferase inhibitors. Drugs Discov Today. 2011;16:418–25. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gros C, Fahy J, Halby L, Dufau I, Erdmann A, Gregoire J. et al. DNA methylation inhibitors in cancer: Recent and future approaches. Biochimie. 2012;94:2280–96. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary tables and figures.