Abstract

Background

Globalisation is having profound impacts on health and healthcare. We solicited the views of a wide range of stakeholders in order to develop core global health competencies for postgraduate doctors.

Methods

Published literature and existing curricula informed writing of seven global health competencies for consultation. A modified policy Delphi involved an online survey and face-to-face and telephone interviews over three rounds.

Results

Over 250 stakeholders participated, including doctors, other health professionals, policymakers and members of the public from all continents of the world. Participants indicated that global health competence is essential for postgraduate doctors and other health professionals. Concerns were expressed about overburdening curricula and identifying what is ‘essential’ for whom. Conflicting perspectives emerged about the importance and relevance of different global health topics. Five core competencies were developed: (1) diversity, human rights and ethics; (2) environmental, social and economic determinants of health; (3) global epidemiology; (4) global health governance; and (5) health systems and health professionals.

Conclusions

Global health can bring important perspectives to postgraduate curricula, enhancing the ability of doctors to provide quality care. These global health competencies require tailoring to meet different trainees' needs and facilitate their incorporation into curricula. Healthcare and global health are ever-changing; therefore, the competencies will need to be regularly reviewed and updated.

Keywords: Diversity and health, Global health, Health promotion, Medical education, Postgraduate education, Workforce development

Introduction

In our increasingly interdependent world, global health is relevant to all health professionals. There is a complex interplay between wider determinants of health, population movement, and shifting patterns of health and disease. Health professionals are required to deliver high quality care to patients with diverse needs and backgrounds.1 Postgraduate education must evolve to prepare health professionals to address the health challenges that globalisation brings.2

The potential benefits of health systems adopting a global health perspective in healthcare practice and management are well recognised.3–7 Global health education aims to awaken health professionals to the interplay between local and global health, health systems and globalisation. Reduction of health inequalities and improvement of health and well-being can only be realised if health professionals understand the global arena in which they are working.

The need for appropriate global health training for doctors has been repeatedly raised,8 and UK medical Royal Colleges have responded to this call with conferences,9 position statements10 and strategies.4,11 Despite this, the Commission on Medical Education for the twenty-first century noted ‘a mismatch between present professional competencies and the requirements of an increasingly interdependent world.’2 A review of eleven UK postgraduate medical and surgical curricula found that only six contained any specific global health competencies, but all curricula contained generic competencies for which a global perspective could be advantageous.12

In undergraduate medical education, global health learning outcomes have been proposed.13 The General Medical Council includes the learning outcome: ‘Discuss from a global perspective the determinants of health and disease and variations in health care delivery and medical practice’ for UK medical undergraduates.14 Global health competencies have also been explored for UK paediatricians15 and North American postgraduate health professionals.16 However, there is no current consensus on the minimum global health competencies required of UK postgraduate doctors, and current curricula vary significantly in terms of global health coverage.12,17

This study aimed to develop core global health competencies relevant to all UK postgraduate health professionals. As the study progressed, it was recognised that the learning needs and training pathways of doctors and other health professionals are sufficiently diverse that this could not be achieved to a good standard within the constraints of the timeframe and given the lack of representation of other health professionals among the author group. Hence, the scope of the study was narrowed after round one to the development of core competencies for postgraduate doctors in the UK and provision of a framework for global health education that may inform curricula in other countries and for other health professionals.

Methods

We carried out a modified policy Delphi consultation to gather and incorporate wide-ranging views of stakeholders. Consultation took place between March and June 2015 and allowed broad consultation (round one), followed by indepth discussions with experts (round two), and then further consultation with all participants (round three).

The authors formed the committee for the consultation. We reviewed published literature and existing postgraduate medical curricula and proposed seven key global health competencies. A draft competency document was developed as a basis for consultation in round one (Supplementary file 1), which represents the main modification from the standard policy Delphi.

Round one

An online questionnaire was circulated to patient, health professional, educator and academic groups who were asked to cascade the questionnaire through their networks and on social media (Supplementary file 2). The questionnaire included information about the study and the anonymous use of responses. It invited multiple choice and free text responses about the relevance and feasibility of the competencies for UK doctors as well as for other health professionals. Participants were invited to offer ideas of how each competency may link to training or work of health professionals in the UK. Consent to participation was deemed implicit in taking the survey. To incentivise participation, we offered participants the chance to win a book token. The survey remained open for 2 weeks.

To inform revision of the competency document for round two, one author compiled descriptive statistics from quantitative results and two authors independently identified themes arising from the qualitative data. Not all suggestions could be accommodated, with the most common reasons for exclusions being conflicting opinions from participants and suggested additions that were beyond the scope of the document. Where there were conflicting opinions, we reached consensus through discussion and reference to published literature, then explored the topic further in round two.

Round two

In round two, we interviewed key stakeholders, including patient representatives, global health educators, clinical leaders and trainee representatives. We sought comments on the updated competency document and contentious areas in round one. We developed a participant information sheet and structured interview proforma. Telephone or face-to-face interviews were each carried out by one researcher, who took notes during the interview. Participants were offered a book token to reward their participation. Round two lasted 3 weeks.

Interview notes were compiled and used to explore themes, including areas of disagreement, drawing on advice from experts (e.g. in economics and ethics) and reference to published literature. We achieved consensus and updated the competencies for round three.

Round three

In round three, we invited all first-round participants who had provided a contact address and all second-round participants to comment on the competency document and verify whether their comments had been adequately addressed. Comments were solicited via an online questionnaire, which was emailed to participants with the updated document. The survey remained open for 1 week, with a reminder sent after 4 days.

We compiled responses and used them to inform the development of the final competencies. We noted areas of ongoing disagreement between participants as discussion points.

Results

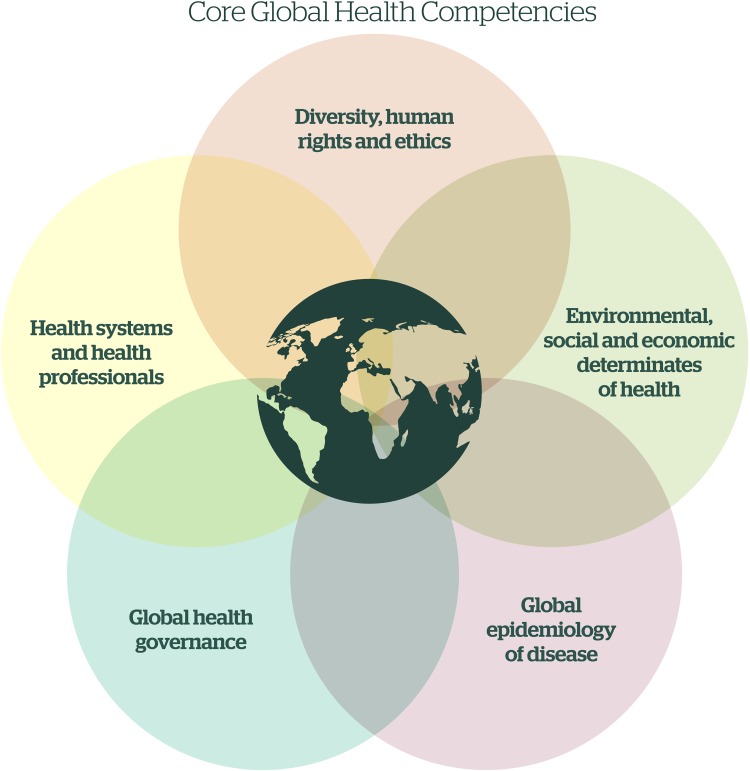

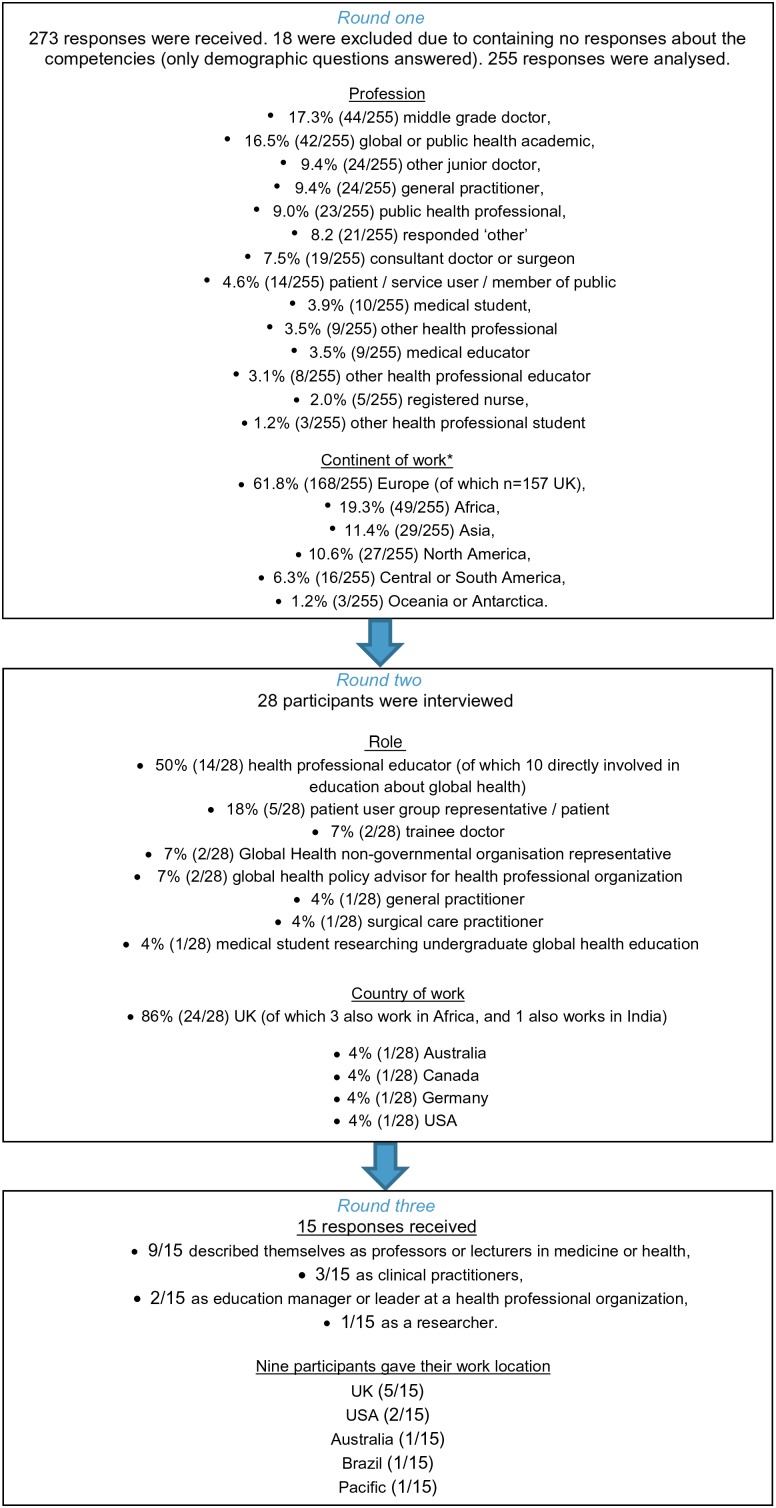

Five inter-related competencies were defined (Figure 2 and Supplementary file 3) after contribution from over 250 individuals (Figure 1).

Figure 2.

Global health competencies for medical professionals.

Figure 1.

Consultation participants. *Participants were able to select more than one continent of work for those that work across more than one location, therefore the total number of responses for continent of work exceeds 255. Number of participants not providing any information on continent of work was one.

In rounds two and three, over 60% of participants indicated that all of the proposed competencies were relevant to doctors. Participants provided wide-ranging examples of how they relate to training and practice.

Participants felt that the level of detail to which a trainee would need to address each competency would vary depending on their profession and speciality. In round one, participants deemed that the competencies were less relevant to and demonstrable by non-medical health professionals. We addressed this feedback by narrowing the aim of the research to the development of competencies for postgraduate doctors. Participants in all rounds suggested that the competencies may yet have relevance for other health professionals, but may require tailoring. We expanded the range of knowledge areas and practice examples provided within each competency to represent the diversity of focuses that may be needed. We also added an acknowledgement in the introduction of the competencies document that educators will need to tailor these competencies to trainees' learning needs and the setting in which the competency is being assessed.

In all rounds, concerns were expressed by participants about overburdening curricula. In response, we amalgamated inter-related competencies and refined competencies such that global health topics can be incorporated into curricula by expanding (rather than adding to the number of) existing competencies. For example to ‘demonstrate an awareness of equity in healthcare access and delivery’18 is a competency frequently encountered in training curricula, which can be enhanced by including a global health perspective, such as ‘consider barriers faced by asylum seekers, undocumented migrants, and survivors of torture’.

Participants called for clarity of language, terms and intended audience (for example, doctors versus all health professional), which we addressed by adding definitions and revising the document for clarity. Alignment of the competencies with an established learning taxonomy was suggested and we did this using Bloom's taxonomy.19

Participants felt that the competencies should reflect a person-centred approach to healthcare, focusing on the patient experience. We refined the competencies to this effect. It is recommended that a person-centred approach is taken to reflect that global health education ultimately aims to improve patient care.

Whether global health should be taught through a global health framework, or structured according to existing health professional competencies, was discussed. Some participants felt that an ecological model (from population-level down to individual-level topics) should structure learning in global health; others felt that the competencies would appear more relevant if they began with competencies focused on interaction with individuals. Further conflicting perspectives emerged regarding the relative importance and relevance of each competency. In response, a statement and diagram to clarify that all competencies are inter-related and equally important has been included in the final document (Figure 2). Integration of the competencies into curricula and approach to learning should be tailored as appropriate within each professional field.

Competency one: diversity, human rights and ethics

For round one, competencies included ‘Human rights and ethics’ and ‘Cultural diversity and health’, which, respectively, 92% and 93% of participants thought were appropriate and feasible competencies for doctors. After round one, we amalgamated these competencies into ‘diversity, human rights and ethics’.

Competency two: environmental, social and economic determinants of health

Competencies before round one included ‘Socioeconomic determinants of health’ and ‘Environmental determinants of health’, which were deemed appropriate and feasible for doctors by 88% and 72% of participants, respectively. In all rounds, comments about environmental determinants of health were at two extremes: some participants stated that understanding environmental issues and their transnational nature is essential for doctors; others felt that addressing environmental issues is beyond their remit. Attempting to respect both views, we included environmental determinants of health within a competency on socioeconomic determinants, and developed tangible practice examples to highlight how environmental issues may fall within the role of health professionals.

Competency three: global epidemiology

In round one, 85% of participants thought that ‘global burden of disease’ was an appropriate and feasible competency for doctors. Some participants felt that the examples given were too specific to be relevant to all doctors regardless of specialty; therefore, we replaced specific disease examples with broader examples and concepts.

Some participants suggested that there should be more focus on certain disease areas (mainly non-communicable diseases and mental health), and certain patient groups (older people, refugees, asylum seekers and undocumented migrants). We added more attention to these disease groups and people.

Participants commented that there should be a shift of focus from disease and its treatment to health and its promotion. We made changes throughout the competency (including referencing demographic transition rather than problems of ageing populations), and changed the title of the competency to ‘global epidemiology’.

Competency four: global health governance

This competency was deemed appropriate and feasible for doctors by 83% of participants. Some participants commented that this competency is beyond the learning needs of doctors. We revised the competency to ensure clarity and focus on the relationship of the roles and duties of doctors.

Participants suggested many additions, such as health impact assessment, transnational health threats and international resources for health (e.g. transplant organs). To avoid being directive and overburdening, we included only overarching and commonly-used concepts.

Competency five: health systems and health professionals

In round one, the competency ‘health systems’ was rated appropriate and feasible for doctors by 82% of participants. Many participants felt that doctors lack an understanding of their own health system; therefore, understanding other health systems is not feasible; others felt that understanding the components of a health system with examples from other countries could aid comprehension of the local health system.

In round two, participants highlighted the importance of understanding how health system configuration and healthcare workers' roles affect population health; therefore, we added further reference to health professionals' roles, migration and work abroad.

Relevance of the competencies to other health professionals

In round one, for each of the seven proposed competencies, the majority of participants indicated that it was relevant and feasible for all health professionals, with a proportion of participants selecting agree or strongly agree that it is relevant and feasible as follows: ‘human rights and ethics’ 86%, ‘cultural diversity and health’ 89%, ‘socioeconomic determinants of health’ 68%, ‘environmental determinants of health’ 54%, ‘global burden of disease’ 56%, ‘global health governance’ 58% and ‘health systems’ 60%. These findings suggest that global health education is relevant and feasible to all health professionals, with particular relevance seen for competencies relating to diversity, ethics and human rights. Where fewer respondents agreed that the competency was relevant to all health professionals, comments suggested that this may be due to the competency being too specific or written using language and concepts that are ‘too medical’ and not accessible enough.

Findings from rounds two and three, including comments from non-medical health professionals and health educators, also suggested that the global health competencies arising from this document have some relevance to, and may benefit, wider health professional education. It was suggested that these topics could be effectively taught in interprofessional educational settings.

Discussion

This is the first large scale consultation on global health competencies for UK doctors, consulting over 250 diverse stakeholders with discussion and reflection on global health competencies for postgraduate medical training. The resulting five core competencies provide an achievable minimum level of core global health competence, required by all postgraduate doctors.

The findings of the consultation demonstrate a perceived difference in the topics and approach to learning of global health required by doctors versus other health professionals. The breadth of the five competencies and the accompanying examples, as well as the input from and endorsement by a range of health professionals, suggest that the competencies may also inform curriculum development for other postgraduate health professionals. Attainment of these competencies by a medical workforce would help to ensure that health services are equipped to care for diverse populations, deal with global influences on health and meet health challenges of the future.

The consultation process evoked discussion and controversy. Analysis of participants' responses confirmed that learning needs are diverse and views of which topics are relevant and what is essential learning vary amongst stakeholders. For example, participants had varying views on whether doctors need to learn about the structure and function of different health systems, environmental issues or laws applying to migration; all of which are determinants of health and bear some relationship to healthcare provision. An individual's views on the relevance of global health competencies may be subject to the individual's type of work, location, level of responsibility, previous exposure to this subject area or conceptualisation of professionalism, social accountability and the roles of health professionals.

As more doctors opt to spend time working in different and diverse healthcare settings, postgraduate education leads may wish to support the design of educational tools to aid doctors intending to work overseas with the clinical knowledge, skills and attitudes required to work effectively in unfamiliar settings. Although the global health competencies proposed here may serve as a building block for this, they are designed with a focus on what a doctor working in the UK needs to know.

The five main learning areas that need to be addressed according to this study are supported by previous work, such as that developing global health learning outcomes for medical undergraduates,14 competencies for UK postgraduate paediatricians16 and competencies for USA health professionals,17 and by forthcoming competencies from the UK Department for International Development;21 all of which identify similar competency areas. The attempt to incorporate global health within core curricula is advocated in previous literature on internationalisation.22

The findings of this study diverge from previous studies in a number of ways, highlighting the evolving nature of global health and medical education dialogues. Examples of these areas of divergence include the incorporation of ethics within a competency addressing diversity and human rights; the equal attention to environmental determinants of health alongside social and economic determinants; the more indepth exploration of global health governance and health systems as they impact on the design and delivery of services locally; and a step away from global burden of disease towards a focus on health promotion by using the term ‘global epidemiology’. This reinforces the importance of ongoing review and update of health professional curricula to reflect the changing nature and understanding of health and healthcare in our ever more globalised world.

Strengths of this study include the number of participants and diversity of their backgrounds, which allowed the combination of perspectives from a variety of health professionals, key health leaders and lay people. Although the majority of respondents worked in the UK, we also gleaned the opinion of those working in other parts of the world, including low and middle income countries.

Limitations included resource constraints affecting study design and the representativeness of the sample surveyed. We encouraged participants to cascade the survey via their networks and social media, and the response rate for round one cannot be calculated. Although the study involved a large number of participants and multiple interactions with study coordinators, the addition of face-to-face group discussions could have generated further ideas and indepth discussion of contentious issues. Furthermore, resource limitations prevented us from recording and transcribing interviews; therefore, there was risk of loss of depth of findings in round two. The identification of participants was dependent on health groups, networks and experts identified by, known to or recommended to the authors; therefore, the population sampled may not represent the full diversity of stakeholders.

Recommendations

In the UK, the need for improved global health training of health care professionals and creation of healthcare environments that support global health initiatives has been identified.4,22 Based on the findings of this study, we recommend that:

all postgraduate medical education bodies identify how these competencies relate to their trainees' learning needs and incorporate global health into their existing curricula,

non-medical health professional educators explore how these competencies can be adapted and incorporated into curricula for their trainees and postgraduates, guided by consultation with trainees, health professionals and other stakeholders,

new learning, teaching and assessment mechanisms to address these competencies are developed, delivered and evaluated, and

regular review of global health competencies is undertaken.

Conclusions

Postgraduate medical education can better prepare doctors for work in our increasingly globalised world through the inclusion of a global health perspective in training. In order to incorporate these competencies into existing speciality curricula without overburdening trainees, it will be important for educators in each speciality to tailor the competencies to the educational needs of their trainees. Incorporation of core global health competencies into existing postgraduate health professional education may ensure that health systems are equipped to care for diverse populations, deal with global influences on health and meet the health challenges of the future. As healthcare and global health are ever changing, these competencies will require regular review and updates, and novel approaches to their integration and delivery.

Supplementary data

Acknowledgments

Authors' contributions: The design and conduct of the project and reporting of the results was undertaken by all of the authors. JH, CB, JW and LP developed the concept for the project. CS, JW, LP, MD, CB, SA and JH designed a protocol and secured funding. SW designed the revised protocol and coordinated the project. The final draft for consultation had contributions from all authors. AM and SW wrote information for participants. CS, MvS, AM, JE, LO, CB, JH and SW carried out thematic analysis after round one. JW contacted interviewees and coordinated interviews. CS, MvS, LO, MD, CB, JW, JH, LP and SW conducted interviews. SW and MvS compiled results from round three. All authors carried out analysis and editing of the document following rounds two and three. SW wrote the first draft of this article, which was reviewed and edited by all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. SW is the guarantor for this paper.

Acknowledgements: Thank you to all participants.

Funding: Funding for this study was provided by the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, who did not influence the design, conduct or reporting of the study. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: All participants were provided with full information about the nature of the study, and were asked to give consent to participation (either implicitly by completing the form or email in rounds 1 and 3 or verbally in round 2). No harm could be anticipated to participants, therefore ethical approval was not sought.

References

- 1.Wagner K, Jones J. Caring for migrant patients in the UK: how the migrant health guide can help. Brit J Gen Pract 2011;61:546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet 2010;376:1923–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health. The Framework for NHS involvement in International Development. London: DH; 2010. http://www.thet.org/health-partnership-scheme/resources/the-framework-for-nhs-involvement-in-international-development-1 [accessed 21 March 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crisp N. Global health partnerships: The UK contribution to health in developing countries: The “Crisp Report”. London: CIO; 2007. http://www.thet.org/health-partnership-scheme/resources/publications-old/lord-crisp-report-2007-1 [accessed 21 March 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health. Health is Global: Proposals for a UK Government-wide strategy. London: DH; 2007. http://graduateinstitute.ch/files/live/sites/iheid/files/shared/summer/GHD%202009%20Summer%20Course/donaldson%20and%20banatvala.pdf [accessed 21 March 2016]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tooke J, Ashtiany S, Carter D. Aspiring to excellence. Findings and final recommendations of the independent inquiry into Modernising Medical Careers. London: MMC Inquiry; 2008. http://www.medschools.ac.uk/AboutUs/Projects/Documents/Final%20MMC%20Inquiry%20Jan2008.pdf [accessed 21 March 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Gold Guide. A Reference Guide for Postgraduate Specialty Training in the UK (4th Edition). London: UK Scrutiny Group; 2014. http://specialtytraining.hee.nhs.uk/files/2013/10/A-Reference-Guide-for-Postgraduate-Specialty-Training-in-the-UK.pdf [accessed 21 March 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 8.House of Lords. Table of contents for Monday 20 December 2010 - NHS: global health. Question for short debate. London: Parliament; 2010. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201011/ldhansrd/text/101220-0002.htm - 10122019000667 [accessed 4 May 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Royal College of Physicians. Building institutions through equitable partnerships in Global Health: A two day global health conference held at the Royal College of Physicians. 14–15 April 2011. https://www.acmedsci.ac.uk/viewFile/53d79ed38b19a.pdf [accessed 21 March 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. RCOG IO Statement on Health is Global. A UK Government Strategy 2008–2013. 2008. https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/news/rcog-io-statement-on-health-is-global.-a-uk-government-strategy-20082013/ [accessed 21 March 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Royal College of General Practitioners. Transforming our approach to international affairs - a 10-year strategy. 2011. http://www.rcgp.org.uk/rcgp-nations/rcgp-international/∼/media/Files/RCGP-Faculties-and-Devolved-Nations/International/2015/Landing-Page/International%20-10yr-international-strategy-2011.ashx [accessed 21 March 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall J, Brown C, Pettigrew L et al. Fi. for the future? The place of global health in the UK's postgraduate medical training: a review. JRSM short reports 2013;4:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson O, Bailey SL, Willott C et al. Global health learning outcomes for medical students in the UK. Lancet 2012;379:2033–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.General Medical Council. Tomorrow's Doctors. London: GMC; 2009. http://www.gmc-uk.org/Outcomes_for_graduates_Jul_15.pdf_61408029.pdf [accessed 21 March 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams B, Morrissey B, Goenka A et al. Global child health competencies for paediatricians. Lancet 2014;384:1403–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jogerst K, Callender B, Adams V et al. Identifying interprofessional global health competencies for 21st-Century health professionals. Ann Glob Health 2015;81;239–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harmer A, Kelley L, Petty N. Global health education in the United Kingdom: a review of university undergraduate and postgraduate programmes and courses. Public Health 2015;129:797–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.AoMRC, & NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. Medical Leadership Curriculum. Coventry, 2009. http://www.aomrc.org.uk/doc_view/133-medical-leadership-competency-curriculum [accessed 21 March 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bloom BS. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: the Classification of Educational Goals: Handbook I. Cognitive Domain. Green, New York: Longmans; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Department for International Development. Technical Competencies- Health Advisers, London: DfID; 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/236438/health.pdf [accessed 10 March 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murdoch-Eaton D, Redmond A, Bax N. Training health care professionals for the future – internationalism and effective inclusions of global health? Med Teach 2011;33:562–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hasan N, Curran S, Jhass A et al. The UK's Contribution to Health Globally: Benefiting the Country and the World. London: All-Party Parliamentary Group on Global Health; 2015. http://www.appg-globalhealth.org.uk/reports/4556656050 [accessed 18 September 2015]. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.