Abstract

Lumbar disk herniation (LDH) is a degenerative pathology. Although LDH generally occurs without migration of the fragment to the levels above or below, in 10% of the cases, this circumstance might happen. In these cases, the standard interlaminar approach, described by Caspar cannot be performed without laminotomies, interlaminectomies, or partial or total facetectomies. The translaminar approach is the only “tissue-sparing” technique viable in cases of cranially migrated LDH encroaching on the exiting nerve root in the preforaminal zones, for the levels above L2-L3, and in the preforaminal and foraminal zones, for the levels below L3-L4 (L5-S1 included, if a total microdiscectomy is unnecessary). This approach is more effective than the standard one, because it resolves the symptoms; it is associated with less postoperative pain and faster recovery times without the risk of iatrogenic instability, and it can also be used in cases with previous signs of radiographic instability. The possibility to spare the flavum ligament is one of the main advantages of this technique. For these reasons, the translaminar approach is a valid technique in terms of safety and efficacy. In this article the surgical technique will be extensively analyzed and the tips and tricks will be highlighted.

Keywords: Translaminar approach, microdiscectomy, minimally invasive approach, hidden zone, lumbar disc hernia (LDH)

Introduction

Lumbar disk herniation (LDH) is a degenerative pathology. Approximately, the 3% of the Italian population suffers from it (male-to-female ratio 2:1.6) (1,2). It was estimated that about the 90% of the adult population will be affected during their lifetime (1,3). Although LDH generally occurs without migration of the fragment to the levels above or below, in 10% of the cases, this circumstance might happen (1,3,4) (Figures 1,2). In these cases, the standard interlaminar approach, described by Caspar cannot be performed without laminotomies, interlaminectomies, or partial or total facetectomies (1,5). These techniques (specifically the facetectomies) may produce an iatrogenic instability and in these circumstance a fusion becomes mandatory (1,6). In the case of cranially extruded LDH (1,7,8) a minimally invasive approach, able to preserve the anatomy and the biomechanics of the spine becomes the most suitable technique.

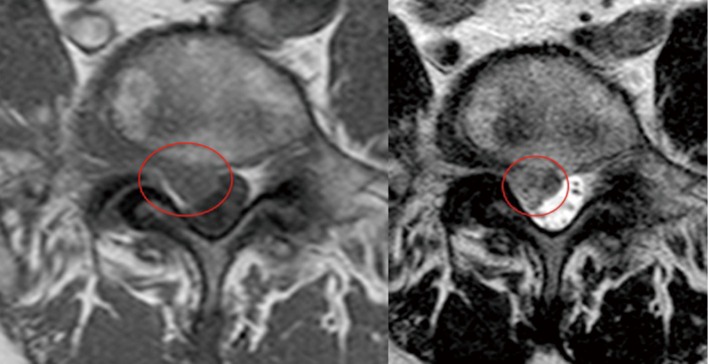

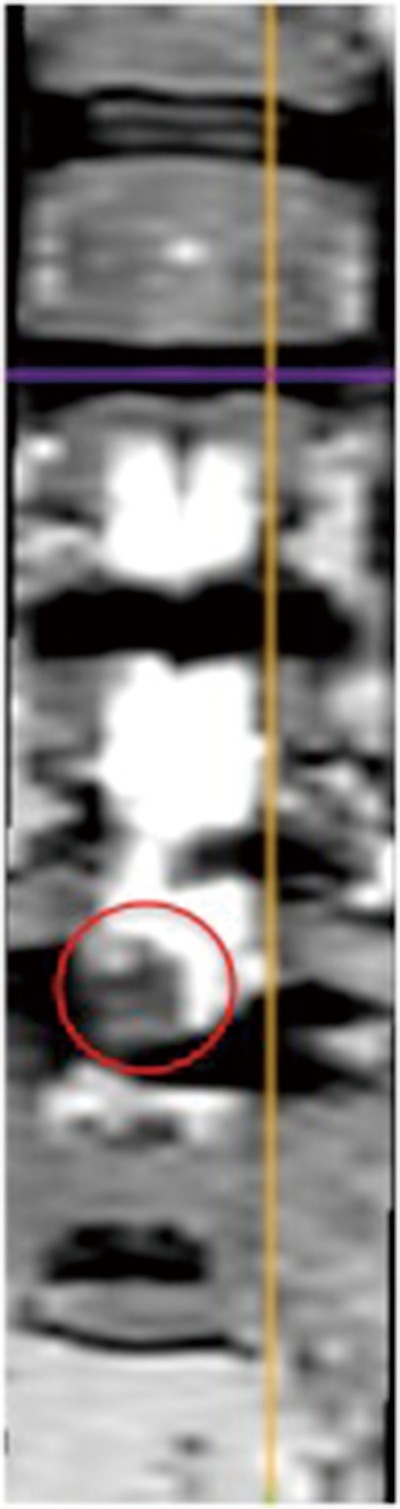

Figure 1.

Migrated LDH- nuclear magnetic resonance (sagittal view).

Figure 2.

Migrated LDH- nuclear magnetic resonance (axial view).

Surgical technique

After the induction of general anesthesia, the patient is placed in a prone position on the surgical table. A positioning device for spinal surgery is used that avoids abdominal compression to prevent the congestion of the perivertebral venous plexus and to reduce the intraoperative bleeding. Under fluoroscopy, the intervertebral space to treat is located by a 25-gauge spinal needle. A precise preoperative planning is fundamental. Using a three-dimensional CT reconstruction, it is feasible to accurately identify the position of the fragment, which is mandatory to exactly place a translaminar hole, just above the fragment. After the subcutaneous infiltration of a local anesthetic, a paramedian skin incision is performed. The infiltration is done not for analgesic aim, but to decrease the capillary bleeding during the skin incision and especially to reduce the risk of skin hyperpigmentation, telangiectasia, and hematomas after surgery.

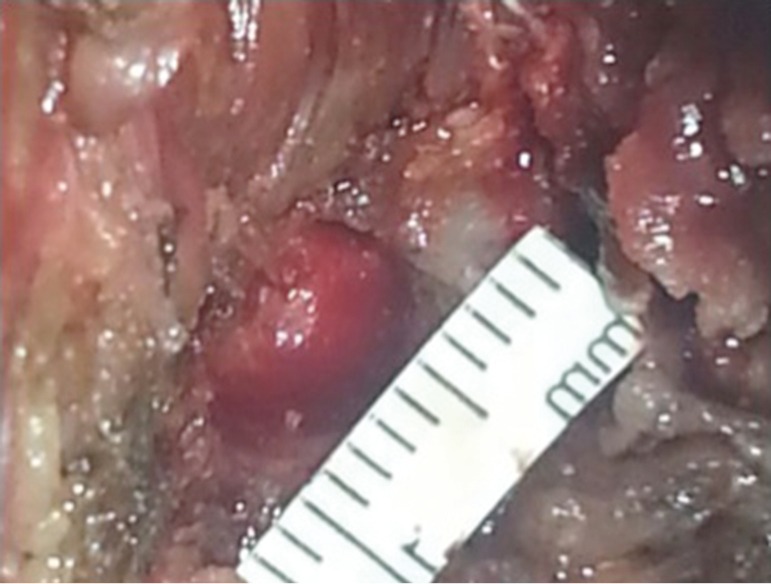

Through a miniaturized Caspar-type speculum-counter-retractor system (Piccolino; Medicon, Tuttlingen, Germany), a mini-invasive approach is performed (skin incision average length: 1 cm) in order to reduce the dissection and the denervation of the paravertebral muscles. Afterwards, the muscular fascia is cut 5 mm from the midline and the fascial splitting is completed in a semicircular way. The paraspinal muscles are elevated subperiosteally and then the lamina and the flavum ligament are exposed. Through a 4 mm diamond dust-coated burr, a translaminar hole (8±2 mm) is accomplished, exposing the involved root (Figures 3,4). The position of the hole must respect Reulen parameters (Figure 5) (1,9): the average width of the isthmus (x1) in L3 is 15.4 mm; in L4 is 18.2 mm; and in L5 is 22 mm; the average distance from lateral margin of the isthmus to lateral border of the vertebral body (x2) in L3 is 6.3 mm; in L4 is 4.8 mm; and in L5 is 2.8 mm; and the average height of the lamina (y) in L3 is 23.1 mm; in L4 is 21.2 mm; and in L5 is 17.3 mm. In fact, the width of the lamina gradually decreases in a cranial-caudal direction, whereas that of the isthmus increases (1,9).

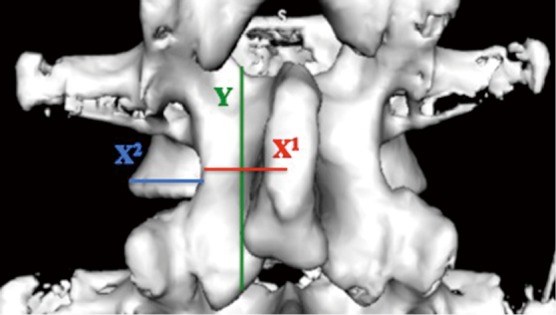

Figure 3.

Circular translaminar hole (circular).

Figure 4.

Circular translaminar hole (circular).

Figure 5.

Reulen’s criteria.

Therefore, the translaminar hole must be more medial and oval-shaped, in the caudal-cranial direction (Figures 6,7). This is mandatory to avoid fractures of the pars interarticularis. Progressively, the epidural space is achieved and the root must be carefully dissected away. The disk fragment can be removed (Figure 8), with care taken to avoid shattering it in small pieces.

Figure 6.

Oval-shaped translaminar hole.

Figure 7.

Oval-shaped translaminar hole.

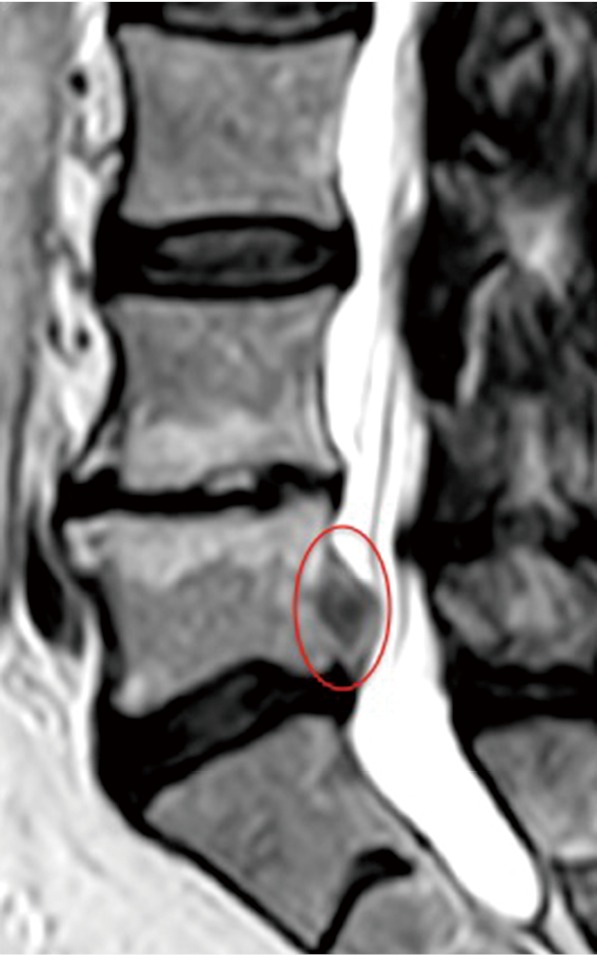

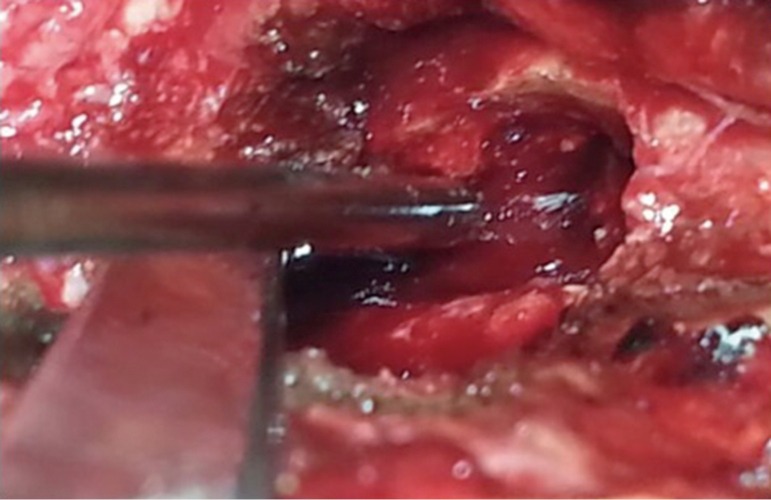

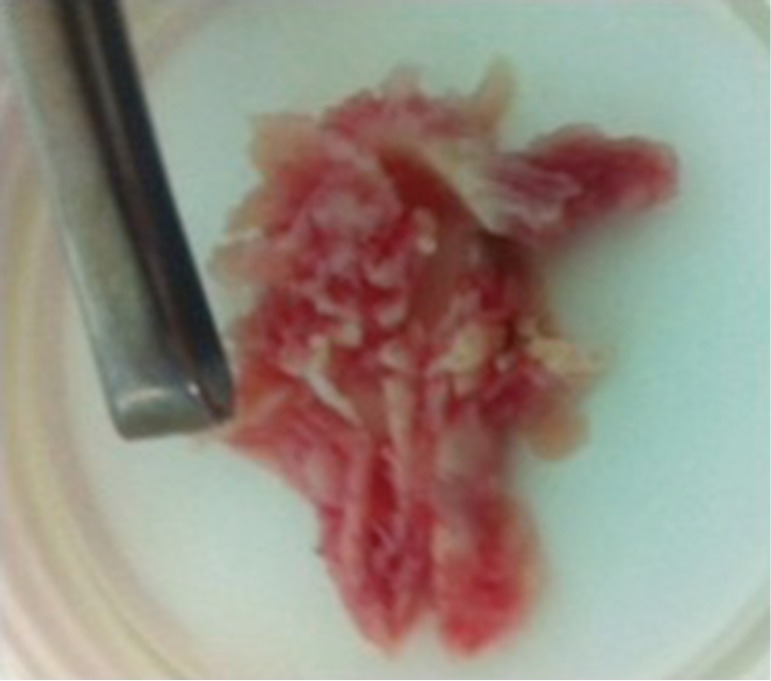

Figure 8.

Herniated disk fragment.

Through a Caspar rongeurs with angulated up-biting or down-biting jaws (jaw size 3 mm), the lateral recess must be explored and any other small disk fragments must be removed. With this approach, facetectomies, laminectomies, laminotomies, and flavectomies are not necessary (1). If the disk fragment is too large to pass through the fenestration, it is possible to gradually cut it outside of the translaminar hole. Epidural bleeding may typically occur after the extraction of the fragment, in which case a fibrin glue can be used. The affected root must be evaluated in each the patient, in order to cautiously dissect it from the herniated fragment. Above all, the integrity of the root must be always verified, especially after the removal of the fragment (1). In fact any adhesions or residual small fragments must be removed even with the help of a carefully washing. According to this surgical approach, partial or total facetectomies, laminectomies, laminotomies, or flavectomies are unnecessary. Severe intraoperative bleeding is very rare (mean risk about 5%) and it is avoidable by the use of local hemostatic agents. When it occurs, it is generally the result of the involvement of the epidural veins. However, this complication did not prolong the surgical time significantly, in generale (mean time: 60±10 minutes) (1).

The patients show a gradual resolution of the back pain and a progressive resolution of the radicolar pain and neurologic deficits (if present) (1). The translaminar approach is a mini-invasive but above all a tissue-sparing technique (1,10,11). In 1998, Di Lorenzo et al. described a different technique, founded on a fenestration at the level of the pars interarticularis (1,12). Correct selection of patients and accurate preoperative planning are mandatory. Therefore, the MRI is necessary to identify the herniated fragment that cranially migrated in the preforaminal or foraminal zone, called the “second window of McCulloch” (1,13).

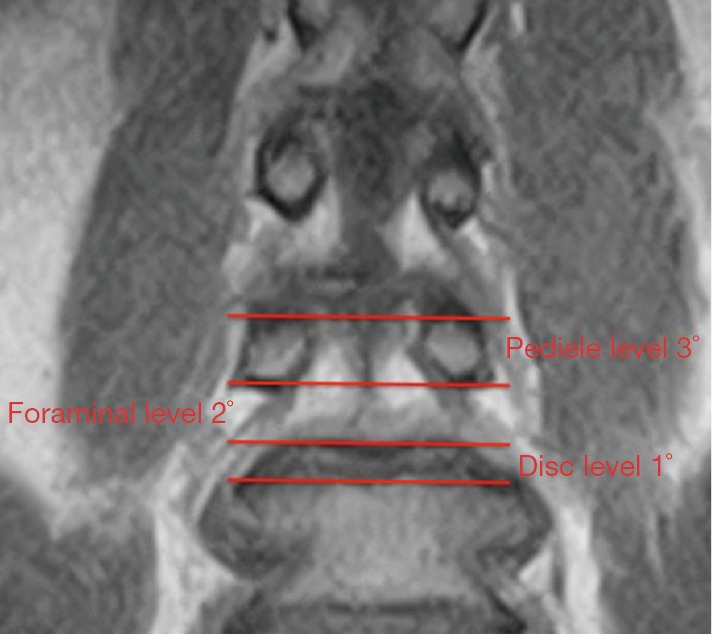

The lumbar spine is made up by the vertebral body and the disk below. According toMcCulloch (1,13), a “three-story anatomic house” is formed (Figure 9). The first story is the disk level. The second story, between the upper rim of the disk space and the lower border of the cephalad pedicle, is the foraminal level and is covered by the lamina. The third story is the pedicle level (1,10). The coronal scans are useful to characterize the fragment position and to identify any compression of the roots (Figures 10,11). The translaminar approach is not indicated in cases of disk herniations located in the first or third window of McCulloch (1,13). Finally, the CT examination is useful to exclude boney abnormalities (congenital or acquired) that contraindicate this approach (i.e., lateral recess stenosis and foraminal spondylosis). As the fenestration is placed a few millimeters from the pars interarticularis, the fracture risk is considerably reduced compared with the technique of Di Lorenzo et al. (1,12).

Figure 9.

McCulloch’s windows.

Figure 10.

Migrated LDH- nuclear magnetic resonance (coronal view). LDH, lumbar disc hernia.

Figure 11.

Migrated LDH- nuclear magnetic resonance (coronal view). LDH, lumbar disc hernia.

In our experience, none of patients complained of low back pain, and the dynamic radiograph showed no fracture or sign of instability. For the preoperative planning, it is mandatory to consider the lamina and isthmus width, which vary depending on the lumbar intervertebral space. The width of the lamina gradually decreases in a cranial-caudal direction, whereas the width of the isthmus increases (according to Reulen et al.), (1,9-14). According to Ikuta et al. (1,15), this implies that in the levels above L2-L3, the overlapping space between the lamina and the intervertebral disk progressively increases, whereas the degree of the foramen coverage by the lamina decreases. In the levels below L3-L4, the opposite occurs (1,15). For these reasons, the fenestration should be more medial and ovalshaped, in the caudocranial direction.

Surgical microdiscectomy allows the successful treatment of patients affected by LDH. When possible, the surgical treatment of LDH should always be done conservatively. According to the standard approach, in case of disk herniations in the hidden zone, this is rarely possible. In these cases, a minimally invasive approach able to respect the spine anatomy and biomechanics becomes the gold standard. The translaminar approach is the only “tissue-sparing” technique viable in cases of cranially migrated LDH encroaching on the exiting nerve root in the preforaminal zones (1,12-16), for the levels above L2-L3, and in the preforaminal and foraminal zones, for the levels below L3-L4 (L5-S1 included, if a total microdiscectomy is unnecessary) (1,16).

Tips and tricks

Infiltration must be performed in order to decrease the capillary bleeding;

The position of the hole must respect Reulen parameters;

The translaminar hole must be more medial and oval-shaped, in the caudal-cranial direction;

The translaminar hole must be placed a few millimeters from the pars interarticularis, in order to avoid fractures;

It is mandatory to consider the lamina and isthmus width, which vary depending on the lumbar intervertebral space;

If the disk fragment is too large to pass through the fenestration, it is possible to gradually cut it outside of the hole;

Residual small fragments can be removed also with a carefully washing;

MRI identifies that the migrated fragment is in the “second window of McCulloch”;

The translaminar approach is not indicated in cases of disk herniations in the “first or third window of McCulloch”;

CT excludes boney abnormalities that can contraindicate this approach.

Conclusions

This approach is more effective than the standard one, because it resolves the symptoms; it is associated with less postoperative pain and faster recovery times without the risk of iatrogenic instability, and it can also be used in cases with previous signs of radiographic instability. The possibility to spare the flavum ligament is one of the main advantages of this technique (1,10). For these reasons, the trans laminar approach is a valid technique in terms of safety and efficacy (1).

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Vanni D, Sirabella FS, Guelfi M, et al. Microdiskectomy and translaminar approach: minimal invasiveness and flavum ligament preservation. Global Spine J 2015;5:84-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kamper SJ, Ostelo RW, Rubinstein SM, et al. Minimally invasive surgery for lumbar disc herniation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Spine J 2014;23:1021-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma D, Liang Y, Wang D, et al. Trend of the incidence of lumbar disc herniation: decreasing with aging in the elderly. Clin Interv Aging 2013;8:1047-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schultz A, Andersson G, Ortengren R, et al. Loads on the lumbar spine. Validation of a biomechanical analysis by measurements of intradiscal pressures and myoelectric signals. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1982;64:713-20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garrido E, Connaughton PN. Unilateral facetectomy approach for lateral lumbar disc herniation. J Neurosurg 1991;74:754-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdullah AF, Wolber PG, Warfield JR, et al. Surgical management of extreme lateral lumbar disc herniations: review of 138 cases. Neurosurgery 1988;22:648-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fankhauser H, de Tribolet N. Extreme lateral lumbar disc herniation. Br J Neurosurg 1987;1:111-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faulhauer K, Manicke C. Fragment excision versus conventional disc removal in the microsurgical treatment of herniated lumbar disc. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1995;133:107-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reulen HJ, Pfaundler S, Ebeling U. The lateral microsurgical approach to the "extracanalicular" lumbar disc herniation. I: A technical note. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1987;84:64-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Papavero L, Langer N, Fritzsche E, et al. The translaminar approach to lumbar disc herniations impinging the exiting root. Neurosurgery 2008;62:173-7; discussion 177-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Askar Z, Wardlaw D, Choudhary S, et al. A ligamentum flavum-preserving approach to the lumbar spinal canal. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003;28:E385-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Lorenzo N, Porta F, Onnis G, et al. Pars interarticularis fenestration in the treatment of foraminal lumbar disc herniation: a further surgical approach. Neurosurgery 1998;42:87-9; discussion 89-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCulloch JA, Young PH. eds. Essentials of spinal microsurgery. Philadelphia: Lippincott Raven, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reulen HJ, Müller A, Ebeling U. Microsurgical anatomy of the lateral approach to extraforaminal lumbar disc herniations. Neurosurgery 1996;39:345-50; discussion 350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikuta K, Tono O, Senba H, et al. Translaminar microendoscopic herniotomy for cranially migrated lumbar disc herniations encroaching on the exiting nerve root in the preforaminal and foraminal zones. Asian Spine J 2013;7:190-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tessitore E, de Tribolet N. Far-lateral lumbar disc herniation: the microsurgical transmuscular approach. Neurosurgery 2004;54:939-42; discussion 942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]