Abstract

This study investigates abuse and rejection sensitivity as important correlates of risky sexual behavior in the context of substance use. Victims of abuse may experience heightened sensitivity to acute social rejection and consequently engage in risky sexual behavior in an attempt to restore belonging. Data were collected from 258 patients at a substance use treatment facility in Washington, D.C. Participants' history of abuse and risky sexual behavior were assessed via self-report. To test the mediating role of rejection sensitivity, participants completed a social rejection task (Cyberball) and responded to a questionnaire assessing their reaction to the rejection experience. General risk-taking propensity was assessed using a computerized lab measure. Abuse was associated with increased rejection sensitivity (B = .124, SE = .040, p = .002), which was in turn associated with increased risky sex (B = .06, SE = .028, p = .03) (indirect effect = .0075, SE = .0043; 95% CI [.0006, 0.0178]), but not with other indices of risk-taking. These findings suggest that rejection sensitivity may be an important mechanism underlying the relationship between abuse and risky sexual behavior among substance users. These effects do not extend to other risk behaviors, supporting the notion that risky sex associated with abuse represents a means to interpersonal connection rather than a general tendency toward self-defeating behavior.

Keywords: risky sex, abuse, substance use, social rejection, rejection sensitivity

1. Introduction

Risky sexual behavior (RSB), including sex with multiple partners, casual partners, and inconsistent condom use (Cooper, 2002), is the leading cause of HIV infection worldwide (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012). Low-income, minority substance users are particularly vulnerable to infection due to high rates of substance use and corresponding elevated rates of RSB (Baskin-Sommers & Sommers, 2006; Celentano, Latimore, & Mehta, 2008).

In an effort to understand the factors that may predispose the individual to engage in these behaviors in the context of substance use researchers have emphasized the role of physical, sexual, and psychological abuse. Indeed, victimization estimates range from 20%-62% among substance users (El-Bassel et al., 2001; Golder & Logan, 2011; Logan et al., 2002). Furthermore, individuals' history of abuse is one of the most important correlates of RSB (Arriola et al., 2005; Van Roode et al., 2009; Wilson & Widom, 2008).

Although there is no debate regarding the existence of the relationship between history of abuse and engagement in RSB, the reason for this association remains largely unknown. This relationship has often been reported as an empirical finding without substantial theoretical explanation (Rodriguez-Srednicki, 2002); the research has overemphasized the role of sexual abuse and suggested that RSB is the result of the distortion of sex-related cognitions (Browne & Finkelhor, 1986; Parillo et al., 2001). However, it is likely that victimization in general (not only sexual abuse) has a broader impact with implications for the way one forms and maintains interpersonal relationships.

The current research uses a social psychological framework and suggests that sensitivity to social rejection is an important mechanism underlying the relationship between abuse and RSB, particularly among substance users. Experiences of abuse may increase one's feelings of alienation and stigmatization and may be internalized as interpersonal rejection (Rosen, Milich, & Harris, 2009; Wölfer & Scheithauer, 2013). Over time, the person may become more sensitive to potential interpersonal rejection and more willing to engage in RSB as a way to foster social connection without the emotional intimacy (Cooper, Agocha, & Sheldon, 2000; Maner et al., 2007). This is particularly relevant in the context of substance use where RSB is often perceived as a normative behavior (Davey-Rothwell & Latkin, 2007; Kopetz et al., 2010).

1.1. Abuse and sensitivity to social rejection

The need to belong has been recognized as one of the most basic and pervasive human motivations (Baumeister & Leary, 1990; Buss, 1990; Maslow, 1968). Consequently, social rejection has been associated with devastating consequences for well-being including low self-esteem, loneliness, depression, anxiety (Boom, White, & Asher, 1979; Leary, 1990; Stillman et al., 2009; Williams, 2001), reduced immune system functioning (Cacioppo, Hawkley, & Bernston, 2003), and self-defeating behavior (e.g., Twenge, Catanese, & Baumeister, 2003).

Extensive research suggests that chronic or traumatic experiences of abuse may be perceived as interpersonal rejection and may be incorporated into individuals' social schemas (Downey & Feldman, 1996; Rosen, Milich, & Harris, 2009; Stock et al., 2013; Williams, Forgas, & Hippel, 2000). Recurring abuse may render these schemas increasingly accessible (Rosen, Milich, & Harris, 2009). As a consequence, individuals with a history of abuse expect, readily perceive, and overreact to social rejection by engaging in risk behaviors that are perceived to prevent rejection or to ensure re-connection (Downey & Feldman, 1996; Greenwald & Farnham, 2000; Iffland et al., 2014). For instance, African American individuals who had experienced racial discrimination repeatedly were more sensitive to rejection and reported increased willingness to use alcohol and engage in RSB following acute rejection relative to those who had not experienced racial discrimination (Gerrard et al., 2012; Stock et al., 2013). Women's sensitivity to social rejection is associated with willingness to engage in sexual behaviors with which they are not comfortable, tolerating abuse, and engagement in delinquent behaviors (Purdie & Downey, 2000). Furthermore, recent preliminary experimental research suggests that women in the general population who experienced interpersonal violence victimization were more likely to engage in RSB and to perceive others as wanting to have sex particularly after experiencing social rejection (Woerner, Kopetz, & Arriaga, 2016). Finally, social rejection induced through a laboratory paradigm significantly predicts RSB in the past year among women substance users (Kopetz et al., 2014).

These findings suggest that previous abuse may dramatically alter individuals' sensitivity and response to acute social rejection (Rosen, Milich, & Harris, 2009). To the extent that RSB can be considered an affiliative behavior which is perceived as normative among members of one's group, rejection may increase one's likelihood of engaging in such behavior as a way to increase social connection (Cooper, Agocha, & Sheldon, 2000; Maner et al., 2007). Another possibility is that rejection elicits a stress response and facilitates engagement in RSB as an attempt to reduce stress and negative emotionality. If this is the case, then rejection should not only increase one's likelihood of engaging in RSB, but the tendency to take risks in general (Stillman et al., 2009).

1.2. The Current Study

To test the above notions, we recruited a sample of substance users in treatment and conducted a cross-sectional study. We assessed participants' self-reported past abuse and RSB. To test the mediating role of rejection sensitivity, participants completed a social rejection task and responded to a questionnaire assessing their reaction to being rejected. We expected that individuals with a history of abuse would report stronger negative responses to social rejection and that such responses would be associated with higher rates of RSB. To test the notion that individuals' response to rejection is particularly relevant to RSB and not risk-taking in general, we assessed participants' substance use and risk-taking propensity using a computerized lab measure and explored the extent to which they were related to participants' past abuse and rejection sensitivity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Two-hundred and fifty-eight participants were recruited from an inpatient substance use treatment facility in Washington, D.C. The mean age of the sample was 43.2 years (SD = 9.6). The majority of the sample was male (65.9%), court-mandated to treatment (74%), and African American (87.2%). At the time of admission into the treatment center, participants were required to complete a detoxification program and evidence no acute pharmacological effects of drug use. Residential treatment typically ranged from 28 to 180 days. Patients were only permitted to leave the facility for scheduled appointments such as psychiatric and primary care appointments. Drug-testing occurred on a weekly basis and any use resulted in immediate removal from the center. Because patients were assessed early in their treatment, none had been removed from treatment at the time of assessment.

Intake assessments were conducted during patients' first week at the center and consisted of a structured interview assessing Axis I and II psychopathology (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV), and the history and pattern of drug use. Individuals were recruited to participate in the study if they 1) had no current symptoms of psychosis and 2) were in their 2nd to 7th day at the treatment facility (to ensure that withdrawal symptoms did not interfere with individuals' ability to complete the study and to control for the effects of time in treatment).

Eligible patients were invited to participate in a study examining factors related to drug use and sexual behavior and were compensated $25 in grocery store gift cards for their time. Interested participants were given a more detailed explanation of the procedures and asked to provide written informed consent. Participants underwent a single assessment session that took place during individuals' free time at the facility in a private room. Participants completed a procedure designed to induce social rejection, completed measures of subjective social rejection, and self-reported RSB. Additionally they completed a computerized measure of risk-taking propensity. Participation was voluntary and it was made clear that it would not influence any other aspect of patients' care. The study protocol was approved by the University of Maryland Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. History of abuse

Participants completed the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ; Bernstein & Fink, 1998), a brief 15-item self-report questionnaire that retrospectively assesses physical, emotional, and sexual abuse with statements such as: “When I was growing up someone tried to make me do sexual things or watch sexual things”. Items are assessed utilizing a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 never true to 5 very often true. Scores of each item were summed such that higher scores represent higher rates of abuse. This measure was highly internally consistent (α = .94). This is one of the most widely utilized measures of childhood abuse and has been cited over a thousand times.

2.2.2 Rejection sensitivity

Participants completed a widely used computerized behavioral task called Cyberball (Williams & Jarvis, 2006) which is designed to induce the experience of social rejection, and has been successfully implemented among substance users (Kopetz et al., 2014). Participants were led to believe that they were playing a ball toss game online with two additional participants. In actuality, the participants played alone. Social rejection is induced by leading participants to believe that the other two participants have chosen not to throw the ball to them. Following the task, participants completed the Need-Threat Questionnaire (Jamieson, Harkins, & Williams, 2000; Van Beest & Williams, 2006; Williams, 2009), a self-report measure assessing the extent to which participants experienced rejection as a result of playing Cyberball. Participants were presented with 12 statements (e.g., “I felt disconnected,” “I felt rejected”) and asked to rate how much each statement applied to them on a five-point scale ranging from 1 not at all to 5 extremely. Responses across items were averaged such that higher scores indicate stronger subjective experience of social rejection (α = .87).

2.2.3 Risky sexual behavior

A modified version of the sexual behavior subscale of the HIV Risk-Behavior Scale (Darke et al., 1991) was administered to assess RSB. The scale has been previously used to assess the number of sexual partners and condom use among substance users (Kopetz et al., 2014). Participants first reported the number of partners (regular, casual, and commercial) with whom they had had penetrative sex (vaginal or anal) in the past 12 months. Response options included: 0 (none), 1 (one), 2 (two), 3 (three to five), 4 (six to ten), and 5 (more than ten partners). Three additional questions assessed the number of times a condom was used when having sex with regular, casual, and commercial partners respectively. Response options included 0 (no sexual partners), 1 (every time), 2 (often), 3 (sometimes), 4 (rarely), and 5 (never), in the past 12 months.

Although number of sexual partners and condom use might be considered two separate dimensions of RSB, there are theoretical reasons to believe that rejection sensitivity is an important correlate of both. Sensitivity to rejection decreases women's perceived power in a relationship, which in turns increases, the frequency of unprotected sex (Berenson et al., 2015). Previous research suggests that people's willingness and likelihood to negotiate condom use might be affected by rejection sensitivity. Specifically, Young and Furman (2008) found that youths who were rejection sensitive might comply with their partner's pressures due to fear of rejection. Extending these findings, Edwards and Barber (2010) found that among both romantic and casual relationships, rejection sensitivity was associated with lower rates of condom use when participants' condom use preference was at odds with what they thought their partners wanted. We therefore suggest that both number of partners and condom use are indicators of RSB in relation to rejection sensitivity. In the current study the two dimensions were significantly correlated (r = .23, p < .01). Thus, participants' RSB score was obtained by adding their responses across the six items (Cronbach's alpha = .59) with higher scores representing higher rates of RSB.

2.2.4 Additional measures of risk-taking

To explore the notion that rejection sensitivity is uniquely relevant to RSB potentially due to participants' desires to fulfill their need for intimacy and connection, we obtained additional indices of risk behavior, namely substance use and risk-taking propensity on a computerized task.

Substance use

Participants' substance use behavior was measured utilizing a standard drug use questionnaire modeled after the Drug History Questionnaire (Sobell, Kwan, & Sobell, 1995) targeting frequency of drug use in the past 12 months. Response options ranged from: 0 never to 5 four or more times a week. Ten substances were assessed including Marijuana, Alcohol, Cocaine, Ecstasy, Methamphetamine, Sedatives, Heroin, PCP, Hallucinogens, and illegal prescription drug use. Frequency total scores were computed by summing use across the 10 assessed substances for a total possible score of 50, which would indicate that the individual used each of the 10 drugs 4 or more times per week over the past year.

Risk-taking propensity

The Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART; Lejuez et al., 2002) was utilized as a behavioral measure of risk-taking propensity. In this task participants were presented with a balloon and were prompted to “pump” the balloon to earn money. The number of points earned per pump varied on each trial; one third of balloons had low value (0.5 cents per pump), one third had a medium value (1.0 cents per pump), and one third had a high value (5.0 cents per pump). Participants were told that their earnings increased with each successive pump, but that popping a balloon would cause them to lose all money accrued for that trial. Unbeknownst to the participants, each balloon was programmed to pop between 1 and 128 pumps, with an average breakpoint of 64 pumps. Participants were able to stop pumping a balloon and choose to collect money at any point during each trial, which would then transfer to a permanent bank. If a balloon was pumped too much, the balloon image “popped”, the money in the temporary bank was lost, and the next trial began. As in previous studies, the average number of pumps across trials on balloons that did not explode (Lejuez et al., 2002) was utilized as the indication of risk-taking.

3. Results

The descriptive statistics for each measure and the first-order correlations among the measures are presented in Table 1. Previous research indicates that engagement in RSB may differ by gender (Kopetz et al., 2014). We therefore conducted preliminary analyses to determine the effect of gender on RSB. This analysis revealed that gender was significantly related to RSB. Specifically, men (n = 191, M = 9.38, SD = 4.33) reported greater RSB relative to women (n = 67, M = 7.94, SD = 3.47), t(256) = 2.45, p = .015. We therefore included gender as a covariate in all subsequent analyses.

Table 1. Demographic Information and Bivariate Correlations between Study Variables: N =258.

| Measure | Frequency (%) Total | Emotional n = 184 | Physical n = 186 | Sexual n = 88 | All 3 n = 71 | No Abuse n = 35 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age (Mean, SD) | 43.3 (9.7) | 43.3 (9.1) | 44.2 (9.1) | 42.8 (9.5) | 43.6 (8.9) | 42.3 (10.3) | |

| Male | 191 (74) | 129 (70.1) | 143 (76.9) | 50 (56.8) | 43 (60.6) | 29 (82.9) | |

| African American | 224 (86.8) | 155 (84.2) | 160 (86) | 73 (83) | 57 (80.3) | 32 (91.4) | |

| < High School | 71 (27.5) | 52 (28.3) | 50 (26.9) | 26 (29.5) | 19 (26.8) | 9 (19.1) | |

| $10k+ Income | 109 (42.2) | 74 (57.6) | 77 (41.4) | 33 (37.5) | 29 (40.8) | 19 (54.3) | |

| Unemployed | 201 (77.9) | 147 (79.9) | 147 (79) | 67 (76.1) | 53 (74.6) | 25 (71.4) | |

| Single | 214 (82.9) | 136 (73.9) | 139 (74.7) | 68 (77.3) | 57 (80.33) | 19 (54.3) | |

|

| |||||||

| Mean (SD) | Range | Bivariate Correlations | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Study Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| CTQ | 26.87 (13.98) | 5-75 | - | ||||

| WNTQ | 28.33 (9.03) | 9-45 | .192* | - | |||

| RSB | 9.00 (4.16) | 1-20 | .198* | .164* | - | ||

| Drug Use | 10.99 (6.22) | 0-50 | .267* | .083 | .172* | - | |

| BART | 37.84 (15.86) | 0-76 | -.003 | .031 | .030 | .005 | - |

Note. CTQ = Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; WNTQ = Williams' Need Threat Questionnaire; RSB = Risky Sexual Behavior; BART = Balloon Analogue Risk Task.

p < .05

A mediation analysis using bootstrapping with replacement (Preacher & Hayes, 2008) was utilized to estimate the indirect effects of abuse on RSB (model 1), drug use (model 2), and risk-taking propensity (model 3), through rejection sensitivity, on the respective dependent variable in each model. Mediation analyses were conducted using the SPSS PROCESS macro with 1000 bootstrap samples which allows for non-normality (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). This modeling technique estimates simultaneous regression analyses and generates confidence intervals that correct for bias in estimating the indirect effects.

Three sets of models were examined using this method; the first set of mediation models tested the effect of abuse on RSB via rejection sensitivity, controlling for the direct effects of gender on RSB. Four separate analyses were conducted: one for each of the three types of abuse assessed (emotional, physical, sexual) and the fourth for the three types combined. The second and third models examined the effects of abuse on substance use and general risk-taking propensity respectively. Based on the notion that people may engage in RSB as a way to experience intimacy and connection, we expected that rejection sensitivity would mediate the relationship between abuse and RSB but not the relationship between abuse and risk-taking in general assessed through drug use and BART.

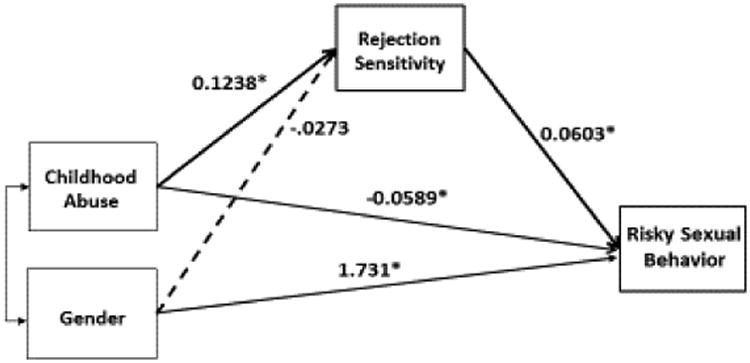

As shown in Table 2, analysis from the first model indicated that each type of abuse (emotional, physical, and sexual) was associated with rejection sensitivity, which in turn was associated with increased RSB. All three types of abuse were combined to assess the combined effect of childhood abuse on RSB via rejection sensitivity. Results showed that greater abuse was associated with increased rejection sensitivity (B = .124, SE = .040, p = .002), which, in turn, was associated with higher rates of RSB (B = .06, SE = .028, p = .03). The indirect effect of rejection sensitivity was significant (B = .0075, SE = .0043; 95% CI [.0006, 0.0178])1. These findings are presented in Figure 1.

Table 2. Effects of Each Type of Abuse on Risky Sexual Behavior through Rejection Sensitivity.

| Emotional | Physical | Sexual | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| B(SE) | p | B(SE) | p | B(SE) | p | |

| Outcome: WNTQ | ||||||

| Intercept | 25.03 (1.57) | <.001 | 26.57 (1.49) | <.001 | 26.47 (1.46) | <.001 |

| Victimization | .33 (.10) | .004 | .25 (.11) | .030 | .23 (.10) | .019 |

| Gender (cov.) | .12 (1.28) | .923 | -.60 (1.28) | .638 | -.02 (1.29) | .988 |

| Outcome: RSB | ||||||

| Intercept | 4.58 (1.00) | <.001 | 4.77 (1.00) | <.001 | 4.99 (1.00) | <.001 |

| Victimization | .14 (.05) | .002 | .14 (.05) | .007 | .10 (.04) | .026 |

| WNTQ | .06 (.03) | .037 | .07 (.03) | .017 | .07 (.03) | .016 |

| Gender (cov.) | 1.78 (.57) | .002 | 1.46 (.57) | .011 | 1.72 (.58) | .004 |

| Direct effect 95% CI [LL, UL] | .14 (.05) [.055, .235] | .002 | .14 (05) [.039, .240] | .007 | .10 (.04) [.012, .189] | .026 |

| Indirect effect* 95% CI [LL, UL] | .02 (.01) [.002,.050] | .02 (.01) [.002, .042] | .02 (.01) [.003, .042] | |||

Note. WNTQ = Williams' Need Threat Questionnaire; RSB = Risky Sexual Behavior; cov. = covariate; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit

Significant indirect effects are evidenced by confidence intervals (CI) that do not include “0”

Fig 1.

Indirect effects of Childhood Abuse on RSB via Rejection Sensitivity.

Mode 1: Indirect effects through Rejection Sensitivity=0.0075*, SE=0.0043, 95% CI [0.0006, 0.0178].

*p < .05

To test the hypothesis that the effect of abuse through rejection sensitivity is unique to RSB and does not affect risk-taking in general we ran two additional models. Consistent with our hypotheses, rejection sensitivity was specifically relevant to RSB and not to participants' risk-taking in general as measured by substance use and the BART. There were no direct or indirect effects of abuse on participants' scores on the BART (model 3: 95% CI [−.0130, 0.0345]). Although the direct effect of past abuse on drug use was significant (B = .096, SE = .0255, p < .001), this relationship was not mediated by rejection sensitivity (model 2: 95% CI [−.0032, 0.160]).

4. Discussion

This research identified rejection sensitivity as an important factor that underlies the relationship between abuse and RSB among substance users. The results show that abuse was related to increased rejection sensitivity as evidenced by a stronger negative reaction to a social rejection laboratory paradigm, which in turn was positively related to RSB. Furthermore, rejection sensitivity uniquely mediated the relationship between abuse and RSB, rather than risk-taking in general (assessed through drug use and risk-taking propensity).

The findings are consistent with previous research suggesting that building intimacy and social connection is an important motivation for engaging in RSB (Cooper, Shapiro, & Powers, 1998) and support the notion that RSB is motivated by a desire to socially reconnect, rather than to reduce stress or negative emotionality induced by rejection.

4.1. Limitations and future research

The results from this study replicate previous research emphasizing abuse as an important risk factor for RSB and extended it by exploring the nature of this relationship and the role of rejection. However, there are noteworthy limitations that suggest the need for future research to better understand the relationships among these variables. The main limitation is the cross-sectional design. Although we assessed childhood abuse and RSB in the past year, which may provide support for temporal precedence of abuse, the design restricts the ability to make causal inferences. These limitations could be potentially addressed in future longitudinal studies.

Despite encouraging support for rejection sensitivity as a mediator of the relationship between abuse and RSB, this relationship may largely depend on how the experiences of abuse were appraised and interpreted. Future research should examine the cognitive and emotional appraisals of traumatic life experiences and assess how they relate to rejection sensitivity and consequently to RSB.

Another limitation refers to our sample. We only recruited participants from treatment facilities, which limits the generalizability of the findings. However, this strategy provides a sample that eliminates most confounds related to pharmacological effects of continuous substance use. Furthermore, this study focuses on substance users as one of the most at risk for HIV infection. However, preliminary findings across several studies indicate that history of abuse and rejection sensitivity are relevant to understanding RSB in the general population as well. Specifically, these studies not only provide systematic support for the association between adult victimization and RSB, but suggest that women's tendency to internalize such experiences as a form of interpersonal loss may underlie this association, and that this relationship is stronger when threat to social belonging is experimentally manipulated (Woerner et al., 2016).

We believe that despite its limitations, this research offers a theoretical analysis and preliminary empirical findings that may stimulate future research and provide valuable insight into RSB associated with substance use. Such research has the potential to inform the development of targeted prevention strategies to reduce RSB by 1) targeting the coping processes associated with abuse and 2) facilitating the availability of less-risky options for social connection such as social support groups. For instance attributional retraining strategies (Försterling, 1985; Walton & Cohen, 2007) may allow victims of abuse to develop effective coping strategies and thus become less likely to anticipate interpersonal harm and to incorporate such experiences into their identities and social schemas. Coping with abuse in a manner that prevents sensitivity to rejection is an important step to increase the likelihood of developing long-term relationships based on emotional connection and trust rather than to relay on casual and risky sexual relationships to satisfy one's need to belong.

In addition, interventions that allow individuals to maintain a sense of self-worth by affirming one's values and cherished attributes (Cohen & Sherman, 2014) could be implemented to reduce stress and feelings of loss associated with acute social rejection. Self-affirmation may allow individuals to perceive the experience of rejection as less of a threat to one's need to belong, which in turn may decrease the likelihood of RSB in response to rejection.

Highlights.

Rejection sensitivity underlies the relationship between abuse and risky sex

Risky sex represents a means to interpersonal connection

Effects of abuse via rejection sensitivity do not extend to other risk behaviors

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Sources: This research was supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse grant R01DA19405 awarded to Carl W. Lejuez, F32DA026253 awarded to Catalina Kopetz, and DA016184 awarded to Damaris Rohsenow.

Footnotes

Correlational analyses indicated that psychiatric diagnoses (PTSD, generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, bipolar, social phobia, borderline personality disorder, alcohol, opiate, cannabis, and stimulant substance use disorders) were not significantly related to RSB which rules out the possibility that the relationship between abuse and RSB is better accounted by psychiatric disorders.

Contributors: (Jacqueline Woerner): Collaborated with the second author on the theoretical perspective and conducted a review of the literature. Wrote the first draft of the introduction and discussion sections. Edited all sections of the manuscript on subsequent drafts.

(Catalina Kopetz): Collaborated with the first author on the theoretical perspective. Edited the entire manuscript and wrote pieces throughout. Was involved with data collection and study design.

(William Lechner): Conducted all statistical analyses, wrote the initial draft of the methods and results sections of the manuscript.

(Carl Lejuez): Designed the study methodology, wrote the research protocol, and collected the data.

All authors have contributed to and approved the final version of the manuscript submitted to Addictive Behaviors.

Conflict of Interest: There are no conflicts of interest by any author.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arriola KR, Louden T, Doldren MA, Fortenberry RM. A meta-analysis of the relationship of child sexual abuse to HIV risk behavior among women. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29(6):725–746. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin-Sommers A, Sommers I. The co-occurrence of substance use and high-risk behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38(5):609–611. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117(3):497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenson KR, Paprocki C, Thomas Fishman M, Bhushan D, El-Bassel N, Downey G. Rejection Sensitivity, Perceived Power, and HIV Risk in the Relationships of Low-Income Urban Women. Women & Health. 2015;55(8):900–920. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2015.1061091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L. Childhood trauma questionnaire: A retrospective self-report: Manual. Psychological Corporation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Boom BL, White SW, Asher SJ. Marital disruption as a stressful life event. Divorce and separation: Context, causes, and consequences. 1979:184–200. [Google Scholar]

- Browne A, Finkelhor D. Impact of child sexual abuse: A review of the research. Psychological Bulletin. 1986;99(1):66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss DM. The evolution of anxiety and social exclusion. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1990;9(2):196–201. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Berntson GG. The anatomy of loneliness. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2003;12(3):71–74. [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Estimated HIV incidence among adults and adolescents in the United States, 2007–2010. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2012;17(4) [Google Scholar]

- Celentano DD, Latimore AD, Mehta SH. Variations in sexual risks in drug users: emerging themes in a behavioral context. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2008;5(4):212–218. doi: 10.1007/s11904-008-0030-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Alcohol use and risky sexual behavior among college students and youth: Evaluating the evidence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, supplement. 2002;(14):101–117. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Agocha VB, Sheldon MS. A motivational perspective on risky behaviors: The role of personality and affect regulatory processes. Journal of Personality. 2000;68(6):1059–1088. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Shapiro CM, Powers AM. Motivations for sex and risky sexual behavior among adolescents and young adults: a functional perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75(6):1528. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.6.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Hall W, Heather N, Ward J, Wodak A. The reliability and validity of a scale to measure HIV risk-taking behaviour among intravenous drug users. AIDS. 1991;5(2):181–186. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199102000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey-Rothwell MA, Latkin CA. Gender differences in social network influence among injection drug users: Perceived norms and needle sharing. Journal of Urban Health. 2007;84(5):691–703. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9215-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Feldman SI. Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70(6):1327. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.6.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards GL, Barber BL. The relationship between rejection sensitivity and compliant condom use. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010;39(6):1381–1388. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9520-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Witte SS, Wada T, Gilbert L, Wallace J. Correlates of partner violence among female street-based sex workers: substance abuse, history of childhood abuse, and HIV risks. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2001;15(1):41–51. doi: 10.1089/108729101460092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Försterling F. Attributional retraining: A review. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98(3):495–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M, Stock ML, Roberts ME, Gibbons FX, O'Hara RE, Weng CY, Wills TA. Coping with racial discrimination: The role of substance use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(3):550. doi: 10.1037/a0027711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golder S, Logan TK. Cumulative victimization, psychological distress, and high-risk behavior among substance-involved women. Violence and victims. 2011;26(4):477–495. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.26.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, Farnham SD. Using the implicit association test to measure self-esteem and self-concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79(6):1022. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.6.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iffland B, Sansen LM, Catani C, Neuner F. The trauma of peer abuse: effects of relational peer victimization and social anxiety disorder on physiological and affective reactions to social exclusion. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2014;5:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson JP, Harkins SG, Williams KD. Need threat can motivate performance after ostracism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010;36(5):690–702. doi: 10.1177/0146167209358882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopetz C, Pickover A, Magidson JF, Richards JM, Iwamoto D, Lejuez CW. Gender and social rejection as risk factors for engaging in risky sexual behavior among crack/cocaine users. Prevention Science. 2014;15(3):376–384. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0406-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopetz CE, Reynolds EK, Hart CL, Kruglanski AW, Lejuez CW. Social context and perceived effects of drugs on sexual behavior among individuals who use both heroin and cocaine. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2010;18(3):214. doi: 10.1037/a0019635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR. Responses to social exclusion: Social anxiety, jealousy, loneliness, depression, and low self-esteem. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1990;9(2):221–229. [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez CW, Read JP, Kahler CW, Richards JB, Ramsey SE, Stuart GL, et al. Brown RA. Evaluation of a behavioral measure of risk taking: the Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART) Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied. 2002;8(2):75. doi: 10.1037//1076-898x.8.2.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan TK, Walker R, Cole J, Leukefeld C. Victimization and substance abuse among women: contributing factors, interventions, and implications. Review of General Psychology. 2002;6(4):325. [Google Scholar]

- Maner JK, DeWall CN, Baumeister RF, Schaller M. Does social exclusion motivate interpersonal reconnection? Resolving the “porcupine problem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92(1):42. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslow AH. Toward a psychology of being. Start Publishing LLC; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Parillo KM, Freeman RC, Collier K, Young P. Association between early sexual abuse and adult HIV-risky sexual behaviors among community-recruited women☆. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2001;25(3):335–346. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdie V, Downey G. Rejection sensitivity and adolescent girls' vulnerability to relationship-centered difficulties. Child Maltreatment. 2000;5(4):338–349. doi: 10.1177/1077559500005004005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repetti RL, Taylor SE, Seeman TE. Risky families: family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128(2):330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Srednicki O. Childhood sexual abuse, dissociation, and adult self-destructive behavior. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2002;10(3):75–89. doi: 10.1300/j070v10n03_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen PJ, Milich R, Harris MJ. Bullying Rejection & Peer Victimization. Springer; New York, NY: 2009. Why's everybody always picking on me? Social cognition, emotion regulation, and chronic peer victimization in children; pp. 79–100. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Kwan E, Sobell MB. Reliability of a drug history questionnaire (DHQ) Addictive Behaviors. 1995;20(2):233–241. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)00071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stillman TF, Baumeister RF, Lambert NM, Crescioni AW, DeWall CN, Fincham FD. Alone and without purpose: Life loses meaning following social exclusion. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2009;45(4):686–694. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock ML, Gibbons FX, Peterson LM, Gerrard M. The effects of racial discrimination on the HIV-risk cognitions and behaviors of Black adolescents and young adults. Health Psychology. 2013;32(5):543. doi: 10.1037/a0028815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM, Catanese KR, Baumeister RF. Social exclusion and the deconstructed state: time perception, meaninglessness, lethargy, lack of emotion, and self-awareness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85(3):409. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Beest I, Williams KD. When inclusion costs and ostracism pays, ostracism still hurts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91(5):918. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.5.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Roode T, Dickson N, Herbison P, Paul C. Child sexual abuse and persistence of risky sexual behaviors and negative sexual outcomes over adulthood: Findings from a birth cohort. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009;33(3):161–172. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton GM, Cohen GL. A question of belonging: race, social fit, and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92(1):82–96. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD. Ostracism: A temporal need-threat model. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 2009;41:275–314. [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD. Ostracism: The power of silence. Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD, Forgas JP, Von Hippel W, editors. The social outcast: Ostracism, social exclusion, rejection, and bullying. Psychology Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD, Jarvis B. Cyberball: A program for use in research on interpersonal ostracism and acceptance. Behavior Research Methods. 2006;38(1):174–180. doi: 10.3758/bf03192765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson HW, Widom CS. An examination of risky sexual behavior and HIV in victims of child abuse and neglect: a 30-year follow-up. Health Psychology. 2008;27(2):149. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woerner J, Kopetz C, Arriaga A. Interpersonal victimization and sexual risk-taking among women: The role of attachment and regulatory focus. Manuscript in preparation 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Wölfer R, Scheithauer H. Ostracism in childhood and adolescence: Emotional, cognitive, and behavioral effects of social exclusion. Social Influence. 2013;8(4):217–236. [Google Scholar]

- Young BJ, Furman W. Interpersonal factors in the risk for sexual victimization and its recurrence during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37(3):297–309. [Google Scholar]