Abstract

Background

During the first postnatal weeks infants have abrupt changes in fluid weight that alter serum creatinine (SCr) concentration, and possibly, the evaluation for acute kidney injury (AKI).

Methods

We performed a prospective study on 122 premature infants to determine how fluid adjustment (FA) to SCr alters the incidence of AKI, demographics, outcomes and performance of candidate urine biomarkers. FA-SCr values were estimated using changes in total body water (TBW) from birth; FA-SCR = SCr x [TBW + (current wt. − BW)]/TBW; where TBW = 0.8 x wt in kg). SCr-AKI and FA-SCr AKI were defined if values increased by ≥ 0.3 mg/dl from previous lowest value.

Results

AKI incidence was lower using the FA-SCr vs SCr definition [(23/122 (18.8%) vs (34/122 (27.9%); p< 0.05)], with concordance in 105/122 (86%) and discordance in 17/122 (14%). Discordant subjects tended to have similar demographics and outcomes to those who were negative by both definitions. Candidate urine AKI biomarkers performed better under the FA-SCr than SCr definition, especially on day 4 and day 12–14.

Conclusions

Adjusting SCr for acute change in fluid weight may help differentiate SCr rise from true change in renal function from acute concentration due to abrupt weight change.

Keywords: Acute Kidney Injury, Urinary Biomarkers, Very low birth weight

Introduction

Although tremendous strides have been made to improve outcomes in extremely premature infants, mortality and long-term morbidity continue to be high [1]. Events that cause renal damage appear to have important implications on short and long-term outcomes [2, 3]. Using empiric definitions that use an acute rise in serum creatinine (SCr) to define acute kidney injury (AKI), we [7–9] and others [10–17] have begun to describe the epidemiology of neonatal AKI. Consistently, this data suggest that neonates hospitalized in intensive care units commonly have AKI, and those with AKI have worse outcomes.

The most widely accepted AKI definition was published in 2012 by Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) [18]. This definition evolved from the Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN) [19] definition proposed in 2007, which evolved from the Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss and End-stage (RIFLE) [20] definition published in 2005. The RIFLE definition was an attempt to standardize the definition, knowing that this first iteration was almost arbitrary. Importantly, the changes made to AKIN and then KDIGO evolved based on critically-evaluated evidence by leaders in the field of AKI. Objective evaluations of neonatal AKI definitions based on large observational multicenter studies in premature infants have not been performed; however, many researchers have adapted a neonatal AKI definition adapted from KDIGO [21]. At this time, its use is empiric with the understanding that refinement may be necessary as evidence grows.

One potentially important factor which may influence how AKI is defined in neonates is the physiologic diuresis that happens over the first days of life. This diuresis, as documented by steady drop in an infant’s body weight, in and of itself will increase the concentration of SCr. Alternatively, if acute fluid accumulation occurs, the SCr will be diluted, making it more difficult to document a rise in SCr. In premature infants, fluid provision is dictated by the clinician, and it is not uncommon to allow premature neonates to lose up to 15% of their weight in the first 4 days of life, as some have suggested that this degree of fluid loss can improve clinical outcomes [22, 23]. These changes in fluid status can have an important effect on SCr concentrations, and thus, the neonatal AKI definition. Studies in pediatric [24] and adult [25, 26] cohorts show that adjusting the SCr for acute changes in fluid status can improve the ability of SCr-based AKI definitions to improve outcomes. To our knowledge, neither the effect of changes in fluid status on SCr concentration, nor the impact that such changes have on the definition of AKI have been explored in detail in premature infants during the first weeks of life.

To improve our understanding on how acute changes in fluid status affect SCr and the definition of AKI, we performed a prospective cohort study on 122 very low birth weight infants. The following three aims were addressed: a) determine how fluid adjustment of SCr (FA-SCR) affects incidence of AKI, b) describe the demographics and outcome differences between those with and without AKI (according to SCr and FA-SCr AKI classification), and c) determine whether candidate urine biomarkers perform better under the FA-SCr AKI definition vs. the traditional SCr-based definitions.

Methods

Study population

The study was approved by the UAB Institutional Review Board, informed parental consent was obtained, and VLBW infants eligible for the study were enrolled. The clinical and research activities being reported are consistent with the Principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

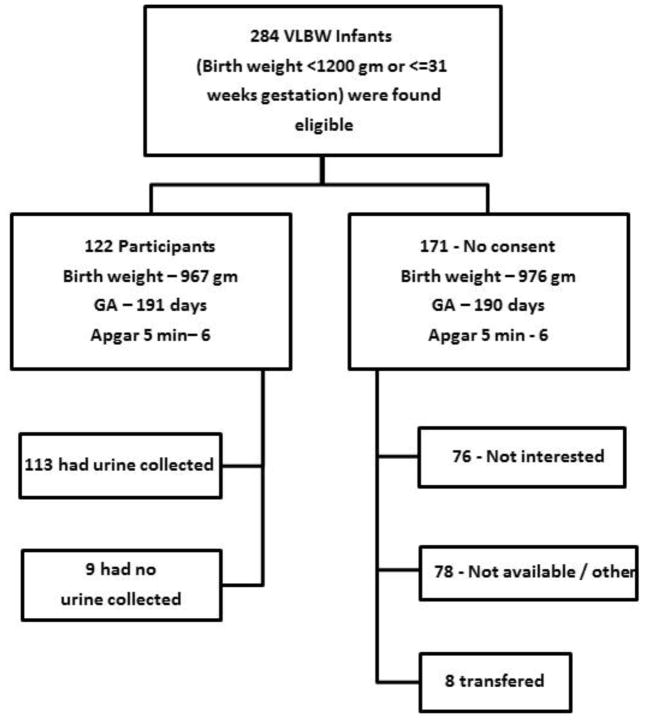

Very low birth weight (VLBW) infants with birth weight (BW) ≤1200 grams and/or ≤31 weeks gestational age admitted to the regional NICU at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) between February 2012 and June 2013, were enrolled in this prospective cohort study. Newborns were excluded if they had known congenital kidney disease, or if they did not survive beyond the first 48 hours of life. We followed enrolled infants from the time of birth until 36 weeks post-menstrual age (PMA) or hospital discharge, whichever occurred first, as it is commonly done to explore hospital outcomes in VLBW infants. There were 284 VLBW eligible infants of which 122 (43%) were enrolled in the study. The reasons for non-enrolment included that parents did not wish to participate (n=76), they were not available (n=78), or they were transferred to other hospital (n=8). Overall, there was no difference between those who agreed to be in the study and those who did not in regards to BW, GA, and 5 minute Apgar scores. Over a 2 week period, nine patients did not have urine collected appropriately, thus, only 113 infants had urine collected for biomarker analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Enrollment and reasons for non-participation in those who met inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study. Birth weight, Apgar scores, and gestational age were not different between consented and non-consented groups.

Exposure and Outcome Definitions

Acute Kidney Injury

In order to ascertain whether a child developed AKI within the first 2 weeks of life, we measured SCr at postnatal days 1, 2, 3, 4, and 12–14 on most infants, in addition to any clinically measured values. The mean number of SCr values obtained for each patient during the first 2 weeks of life was 5 (range 2–14). Neonatal AKI was defined according to a contemporary definition modified for neonates, similar to the KDIGO AKI definition by which, as previously described, a SCr rise ≥0.3 mg/dl defines AKI [21]. The main modification from KDIGO definition concerns how the baseline SCr is obtained. Each SCr from a specific time point is compared to the lowest previous SCr value until that time point. This is necessary because SCr at birth reflects maternal SCr, which decreases steadily over the first weeks of life. We did not include urine output criteria as it is often difficult to measure urine output in babies, and many premature infants with AKI are non-oliguric because of poor tubular function.

We used changes in weight from birthweight to represent fluid status changes. Fluid adjustment SCr values were estimated using changes in total body water (TBW) using the following equation: SCr x [TBW + (current wt. − BW)]/TBW, as previously described by Liu et al. [25]. and Basu et al. [24, 27] Because % TBW is about 80% of weight in premature infants [27–28], we used 0.8 x weight (kg) to define TBW (Liu et al. and Basu et. al used 0.6 for their adult and pediatric cohorts). FA-SCr AKI was defined as a rise in FA-SCr by ≥0.3 mg/dl from previous lowest value.

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD)/Mortality

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia was defined — as per the National Institute of Health (US) criteria for BPD — if an infant was oxygen dependent at 36 weeks post-menstrual age (PMA) [29]. We report survival if the infant survived until 36 weeks PMA or hospital discharge, whichever occurred first, as commonly done to explore hospital outcomes in VLBW infants. We combined BPD/death as a composite because they represent competing outcomes and are the most common method of analysis for chronic lung disease in neonates [30–32]. Intra-ventricular hemorrhage (IVH) was assessed by routine clinical head ultrasounds.

Biomarker Analysis

Urine was collected daily during the first 4 days of life using cuddle buns™ (Small Beginnings, Hersperia, CA, USA) diapers placed at the perineum. Most infants [60/113 (53%)] had samples for all 4 days; 32% (n=35) for 3 days, 12% (n=13) for 2 days, and 4% (n=5) for only 1 day. The moist part of the diaper was cut out and placed in a syringe. Urine was squeezed into a centrifuge tube using the syringe plunger, and centrifuged for 10 minutes to separate urine. The supernatant was aliquoted and frozen at −70° C until evaluation. Urine biomarker analysis was performed by electrochemiluminescence on multi-array plates using the Sector Imager 2400 (Meso Scale Discovery (MSD); Gaithersburg, MD). Albumin, Beta-2-Microglobulin (B2M), Cystatin C, epithelial growth factor (EGF), neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), osteopontin (OPN), and uromodulin (UMOD) were measured in urine using MSD Human Kidney Injury Panel 5 Kit assay, while Alpha Glutathione S-Transferase (αGST), Calbindin, Clusterin, KIM-1, Osteoactivin, Trefoil factor 3 (TFF3), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) were measured using MSD Human Kidney Injury Panel 3 Kit Assay. Samples in Panel 3 were diluted 10-fold before being added to the plate. Samples in Panel 5 were diluted 500-fold before being added to the plate. Samples were added to plates and prepared as stated in the manufacturer’s protocol and analyzed on Sector Imager. All markers detected in the samples were within range of the standard curve. Inter-run %CV (coefficient of variance) and intra-run %CV, as well as variability of samples and standards between and in runs, was below 10% in all cases, and below 5% in most sample/standard comparisons.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics were performed to determine demographic differences between those infants whose family consented to the study and those who did not (Figure 1). Subjects enrolled in the study were categorized by AKI status for SCr (− vs +) and FA-SCr (− vs +) definitions, and significant differences were assessed using Fisher’s exact test (Table 1). Demographic and outcome differences by AKI were compared for four groups categorized by AKI status for SCr (− vs +) and FA-SCr (− vs +) definitions (Table 2 and 3, respectively). Normally distributed continuous variables were compared using student t test, and non-normally distributed variables were analyzed using Kruskal-Wallis test. Cochran–Mantel-Haenszel chi square statistic was used to analyze stratified categorical data. Univariate crude analysis was performed to assess association between those who had AKI by both definitions vs. those who were negative by both definitions. Logistic linear regression was performed to determine the association of clinical outcomes by groups (with those who were negative by both definitions acting as reference) and controlling for 5 minute Apgar scores, maternal pre-eclampsia and gestational age. These variables were chosen as we have shown that there are substantive differences between those with and without AKI in this population [8].

Table 1a.

Distribution of AKI outcomes for ALL infants

| AKI (FA-SCr) | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| − | + | |||

| AKI (SCr) | − | 85 | 3 | 88 |

| + | 14 | 20 | 34 | |

| Total | 99 | 23 | 122 | |

| p-value <0.001 | ||||

AKI – acute kidney inury, FA-SCr – fluid adjustment serum creatinine

Table 2.

Demographic and outcomes by AKI categories (N=122)

| SCr (−) FA-SCr (−) (N=85) |

SCr (+) FA-SCr (−) (N=14) |

SCr (−) FA-SCr (+)(N=3) |

SCr (+) FA-SCr (+)(N=20) |

P-value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infant Demographics | |||||

| Birth weight § | 1000 (450) | 1060 (610) | 940 (325) | 742 (400)** | 0.23 |

| GA weeks § | 28 (3) | 27 (5) | 28 (0.5) | 26 (3.5)** | 0.05 |

| Apgar 1 minute § | 5 (4) | 5 (5) | 5 (6) | 4(5) | 0.59 |

| Apgar 5 minute § | 7 (1) | 7 (3) | 7 (6) | 7 (2) | 0.09 |

| Male (N, %) | 46 (54) | 6 (3) | 2 (66) | 8 (40) | 0.27 |

| Race (N, %) | 0.76 | ||||

| White | 33 (38) | 9 (64) | 0 | 5 (25) | |

| Black | 44 (52) | 5 (35) | 3 (100) | 15 (75) | |

| Other | 8 (10) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| UAC (N, %) | 31 (36) | 5 (35) | 1 (33) | 14 (70) | 0.01 |

| Maternal Demographics (N,%) | |||||

| Prenatal Care | 79 (93) | 13 (92) | 3 (100) | 18 (90) | 0.67 |

| Preeclampsia | 32 (38) | 0 | 1(33) | 2(10) | 0.006 |

| Diabetes | 9 (11) | 1 (7) | 0 | 2 (10) | 0.78 |

| Hypertension | 24 (28) | 5 (35) | 1 (33) | 5 (25) | 0.76 |

| Smoking | 12 (14) | 2 (14) | 0 | 3 (15) | 0.86 |

| Multiparity | 22 (25) | 9 (64) | 1 (33) | 4 (20) | 0.88 |

GA - gestational age; LOS - lengths of stay; UAC- umbilical artery catheter, AKI – acute kidney injury; SCr – serum creatinine; FA – fluid adjustment; GA – gestational age;

P-values from Kruskal-Wallis Test where medians are given, else from Mantel-Haenszel chi-square.

Median (IQR)

p<0.01 for SCr(+)/FA-SCr (+) vs. other 3 groups

Table 3.

Outcomes by AKI categories (N=122)

| SCr (−) FA-SCr (−) (N=85) |

SCr (+) FA-SCr (−) (N=14) |

SCr (−) FA-SCr (+) (N=3) |

SCr (+) FA-SCr (+) (N=20) |

P-value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes (N,%) | |||||

| Survival | 76 (89) | 13 (93) | 3 (100) | 15 (75) | 0.13 |

| BPD | 18 (23) | 4 (30) | 1 (33) | 7 (46) | 0.06 |

| BPD/Mortality | 27 (31) | 5 (35) | 1 (33) | 12 (60)* | 0.02 |

| IVH | 23 (28) | 1 (7) | 0 | 11 (55)** | 0.06 |

GA = gestational age; LOS = lengths of stay; UAC = umbilical artery catheter; IVH = intra-ventricular hemorrhage; BPD = bronchopulmonary dysplasia; AKI = acute kidney injury; SCr = serum creatinine; FA = fluid adjustment

P-values from Kruskal-Wallis Test where medians are given, else from Mantel-Haenszel chi-square.

Median (IQR)

p<0.05;

p< 0.01 for SCr(+)/FA-SCr (+) vs. other 3 groups

Logistic regression was used to construct the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) and calculate the area under the curve (AUC) for each biomarker on days 1, 2, 3, 4, and 12–14, as well as its predictive characteristic for the two AKI definitions. We controlled for gestational age because we and others have shown that urine biomarker significantly vary by gestational age. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for all statistical analysis.

Results

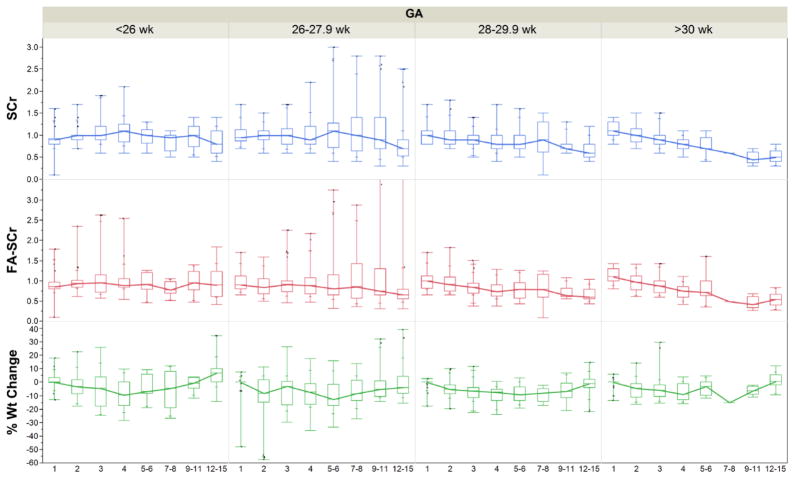

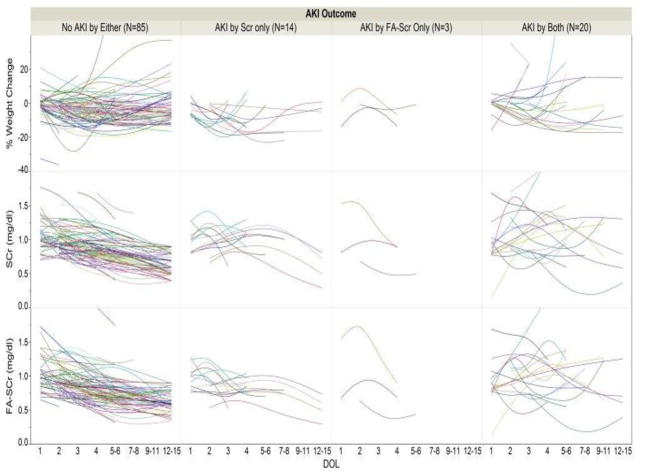

Following the SCr AKI definition, 34 out of 122 (28 %) premature infants had AKI; while using the FA-SCr definition, 23 out of 122 (19 %) infants had AKI. There was agreement in 105/122 (86%) subjects (i.e., 85 were negative using both definitions, and 20 were positive with both). On the other hand, there was discordance for the two definitions in 17/122 (14%) [i.e., 14 were SCr (+) but FA-SCr (−), while three were SCr (−) but FA-SCr (+); two-sided p<0.001] (Table 1a). We also show this distribution stratified by gestational age categories (Tables 1b, 1c and 1d). Infants who were <27 weeks, 2730 weeks, and those ≥30 weeks had discordant cells (i.e., positive by one definition and negative by the other) of 5/41 (12%); 10/58 (17%) and 2/22 (9%), respectively. Figure 2 shows changes in SCr, % weight change and fluid adjusted SCr grouped by gestational age. Figure 3 shows changes in SCr, % weight and fluid adjusted SCr for those individuals who were negative for both AKI definitions, positive for one of them, and positive for both.

Table 1b.

Distribution of AKI outcomes in <27 weeks GA

| AKI (FA-SCr) | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| − | + | |||

| AKI (SCr) | − | 25 | 0 | 25 |

| + | 5 | 11 | 16 | |

| Total | 30 | 11 | 41 | |

| p-value <0.01 | ||||

AKI – acute kidney inury, FA-SCr – fluid adjustment serum creatinine, GA – gestational age

Table 1c.

Distribution of AKI outcomes for ≥27 and <30 weeks

| AKI (FA-SCr) | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| − | + | |||

| AKI (SCr) | − | 40 | 3 | 43 |

| + | 7 | 8 | 15 | |

| Total | 47 | 11 | 58 | |

| p-value <0.01 | ||||

AKI – acute kidney inury, FA-SCr – fluid adjustment serum creatinine

Table 1d.

Distribution of AKI outcomes for ≥30 weeks and

| AKI (FA-SCr) | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| − | + | |||

| AKI (SCr) | − | 19 | 0 | 19 |

| + | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| Total | 21 | 1 | 22 | |

| p-value <0.01 | ||||

AKI – acute kidney inury, FA-SCr – fluid adjustment serum creatinine

Figure 2. SCr, FA-SCr, and % weight change over time by gestational age (GA).

Distribution of % weight change, serum creatinine (SCr) (mg/dl) and fluid adjustment (FA)-SCr according to gestational age groups.

Figure 3. Distribution of % weight change, SCr and FA-SCr according to AKI definitions.

Distribution of % weight change, serum creatinine (SCr) (mg/dl) and flluid adjustment (FA)-SCr according to acute kidney injury (AKI) definitions (negative for both defintions vs. AKI by SCr definition only vs. AKI by FA-SCr definition only or both)

Demographic differences by AKI status in the four groups are shown in Table 2. Gestational age was lowest in those with both SCR and FA-SCR positive AKI (p< 0.05). Infants that were positive for both SCr and FA-SCr AKI were more likely to have an umbilical artery catheter (UAC). Infants whose mothers had pre-eclampsia were more likely to be AKI negative by both definitions. There were no other statistically significant differences on infant or maternal demographics.

Outcome differences between groups are shown in Table 3. Those with both SCr(+) and FA-SCr (+) AKI had worse outcomes than all others combined, while those who were AKI positive for either SCr or FA-SCr had similar outcomes to those who were negative for both definitions. Table 4 shows the crude and adjusted odds ratio (OR) for clinical outcomes stratified for those who had SCr AKI only, FA-SCr AKI only, and those who had AKI by both definitions; subjects who were negative by both definitions serve as the reference group. Those with both SCr and FA-SCr AKI had 3.2 higher odds of BPD/mortality (95%CI 1.2–8.7; p< 0.05) and 3.1 higher odds of IVH (85% CI 1.1–8.4; p< 0.05) than those without AKI. Controlling for maternal pre-eclampsia, 5 minute Apgar and gestational age decreased the estimate odds ratio, but likely because of sample size, the effect was no longer statistically significant. Because of small sample size there were very wide confidence intervals for crude and adjusted OR for those with SCr only, or FA-SCr only.

Table 4.

Association between AKI and Clinical Outcomes

| Mortality (N=15) | BPD/Mortality (N=45) | IVH N=35 (missing =4) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AKI | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR† (95% CI) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR† (95% CI) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR‡ (95% CI) |

|

SCr (−) FA- SCr (−) (n=85) |

-- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

|

SCr (−) FA- SCr (+) (n=14) |

0.65 (0.07, 5.56) | 0.6 (0.06, 5.95) | 1.19 (0.36, 3.9) | 1.67 (0.38, 7.32) | 0.19 (0.02, 1.59) | 0.15 (0.01, 1.32) |

|

SCr (+) FA- SCr (−) (n=3) |

<0.001 (<0.01, >99.9) | <0.001 (<0.01, >99.9) | 1.07 (0.09, 12.36) | 1.98 (0.15, 26.14) | <0.001 (<0.01, >99.9) | <0.001 (<0.01, >99.9) |

|

SCr (+) FA-SCr (+)(N=20) |

2.8 (0.81, 9.54) | 1.8 (0.53, 7.31) | 3.2* (1.22, 8.73) | 2.98 (0.85, 10.45) | 3.1* (1.11, 8.42) | 2.15 (0.72, 6.41) |

adjusted for maternal preeclampsia, 5 minute Apgar, and gestational age

P< 0.05

AKI = acute kidney injury; FA = fluid adjustment; SCr = serum creatinine; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval

Biomarker analysis

The incidence of AKI in the 113 infants with urine collected was 29/113 (26%) and 19/113 (17%) for SCr and FA-SCr based definition, respectively. Table 5 shows the ability of biomarkers to predict AKI for five biomarkers at four time points. We show the ROC AUC for AKI according to the SCr and the FA-SCr for days 1–4 and day 14, controlled for gestational age. Compared to the performance of these biomarkers using the SCr definition, the performance of the biomarker increased with the FA-SCr AKI definition, particularly for days 4 and 14. Of all biomarkers for all days and definitions, NGAL on day 4 for FA-SCr AKI performed best (AUC adjusted for GA = 0.86).

Table 5.

Performance of 7 urine biomarkers by date for SCr and FA-SCr based definitions

| Area under the curve (AUC) for receiver operating characteristic (ROC): Urine biomarkers by day controlled for gestational age | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| AUC day1 | AUC day 2 | AUC day 3 | AUC day 4 | AUC day 14 | |||||||

| SCr AKI | FA-SCr AKI | SCr AKI | FA-SCr AKI | SCr AKI | FA-SCr AKI | SCr AKI | FA-SCr AKI | SCr AKI | FA-SCr AKI | ||

| Cystatin C | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.62 | 0.68 | |

| NGAL | 0.66 | 0.62 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.86 | 0.72 | 0.75 | |

| OPN | 0.66 | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.70 | 0.68 | 0.74 | 0.81 | 0.69 | 0.76 | |

| Clusterin | 0.66 | 0.64 | 0.69 | 0.72 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.76 | 0.81 | 0.65 | 0.76 | |

| KIM1 | 0.69 | 0.64 | 0.68 | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.70 | 0.72 | 0.85 | 0.59 | 0.72 | |

| VEGF | 0.64 | 0.62 | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.71 | 0.68 | 0.76 | 0.62 | 0.68 | |

| αGST | 0.67 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.76 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.76 | 0.58 | 0.66 | |

SCr = serum creatiine; FA = fluid adjustment; AKI = acute kidney injury

Discussion

We hypothesized that adjustment of SCr for acute changes in fluid status could have a significant impact on the definition of AKI in premature infants, as many can lose more than 15% of their weight over the first week of life. Our data suggest that a fluid adjusted SCr AKI definition would lower the incidence of AKI substantially, may be more closely associated with clinical outcomes, and may improve the precision performance of candidate urine biomarkers.

To our knowledge, there are no other studies exploring how the fluid changes that occur over the first week of life affect SCr and AKI definition in premature infants. Studies performed in adults by Liu et al. [25] and Thongprayoon et al. [26], and in children by Basu et al. [24], showed that a SCr adjustment for acute fluid changes improves the ability to predict clinical outcomes. There are several important differences between their studies and the current study. We used a higher % TBW in our cohort to reflect the TBW in premature infants. Whereas they found a higher incidence of AKI when applying a fluid correction, the incidence of AKI in our cohort was reduced when SCr was adjusted for acute changes in fluid. The likely reason for this is that in our cohort most premature infants lost weight over the first few days of life, whereas subjects in the other studies primarily were gaining weight due to fluid overload during acute critical illness. In those who are acutely gaining fluid weight SCr becomes more diluted, which increases the needed threshold for AKI diagnosis. On the contrary, for those who are losing fluid weight acutely, increases in SCr may give a false impression that the actual renal function was worsening, when in fact, it may simply represent a concentration effect seen with acute fluid losses.

In premature infants there are a few reasons why acute changes in fluid balance occur. These include: acute losses via the skin, particularly in open cribs that are not humidified [4], low provision of fluid; and high output of the urinary tract, gastrointestinal tract, chest tubes or other sites. SCr changes in premature infants during the first weeks of life, are not only due to changes in renal function, which are different according to gestational age; but also to the acute changes in volume status and the influence of maternal serum creatinine. Infant creatinine mirrors maternal creatinine at birth, but when maternal creatinine is excreted the baby’s body must find a new equilibrium. This is analogous to why after a successful kidney transplant, despite excellent urine output and GFR, it may take days to equilibrate SCr to a true estimate of GFR.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to compare the performance of urine biomarkers against the standard SCr definition and FA-SCr definition in any population. It is possible that one of the reasons why urine biomarkers have not performed as successfully as hoped, may have more to do with the gold standard definition with which the biomarkers are being compared to. If the FA-SCr AKI definition indeed is better at predicting clinical outcomes, it would be reasonable that future studies to determine the validity of urine biomarkers use this better “gold standard” definition to determine biomarker accuracy. Evaluation of biomarker performance in premature infants need to be evaluated in context of gender, postnatal day, and gestational age, which can affect urine biomarker levels independently of AKI.[5, 6]

Our data suggest that if one accounts for the concentration/dilution effects that abrupt fluid changes can produce on SCr values, then the classification of AKI would differ and the true incidence of AKI would be lower than using a conventional SCr approach. If a FA-SCr definition is more closely associated with clinical outcomes and known urine biomarkers of kidney damage, it could have important implications on our understanding of the epidemiology, the care of these babies, and future research endeavors in this and other ICU cohorts who have abrupt changes to fluid status.

Strengths of the study include a relatively large homogenous cohort of premature infants with a high number of SCr measurements during protocol-driven sample collections. We show not only how fluid adjustment affects clinical outcomes, but also how misclassifying AKI could have an important impact on clinical outcomes and biomarker performance. Despite these strengths, we acknowledge several limitations. This was a single center study, and our findings need to be replicated in larger multicenter cohorts. Although it appears that those who only had AKI by SCr definition (but were FA-SCr negative) had demographical, outcome and biomarker characteristics more closely related to those without AKI by either definition, we do not have adequate power to provide definitive conclusions. Future studies with larger cohorts will be needed to validate these relationships. Although this study had many SCr and urine biomarkers measurements, we did not have daily SCr on every infant for the duration of the evaluations. The TBW estimate that we used assumes similarities across all infants and across days. It is possible that further refinement (according to gestational age and day of life) may be needed. Although we show how adjustment in weight affects all gestational age groups, we acknowledge that different gestational age groups may require different AKI definitions. Finally, we acknowledge that the impact of urine output on the definition of AKI cannot be determined from this study, because most of the babies did not have strict intake and output performed as part of clinical care.

In conclusion, acute fluid changes during the first week of life affect SCr levels, thereby questioning how we define AKI. Incorporation of acute change in fluid status to SCr values may define which infants have a rise in SCr simply as a reflection of changes in fluid weight, and which infants have true renal functional changes. Large multi-center studies will be needed to further corroborate our novel findings in this and other cohorts. Adjustment for severity of illness scoring will enhance our ability to make proper inferences. A better understanding of how the abrupt changes in fluid status impacts SCr values could have an important influence on the interpretation of epidemiologic/biomarkers/interventions studies in AKI. In addition, these data suggest that the response to changes in SCr must be examined in the context of changes in fluid balance, as it will help clinicians better distinguish the etiology of changes in SCr and assist in making clinical decisions regarding fluid provision.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Statement of financial support: Research reported in this publication was supported by the Norman Siegel Career Development Award from the American Society of Nephrology. Dr. Askenazi receives funding from the NIH (R01 DK13608-01) and the Pediatric and Infant Center for Acute Nephrology (PICAN), which is sponsored by Children’s of Alabama and the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s School of Medicine, Department of Pediatrics and Center for Clinical and Translational Science (CCTS) under award number UL1TR00165. Dr. Ambalavanan receives funding from NIH (grant # U01 HL122626; R01 HD067126; R01 HD066982; U10 HD34216). Dr. Griffin receives funding from UAB CCTS, and PICAN.

Footnotes

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, as well all with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Informed Consent: Informed parental consent was obtained for all individual participants included in the study.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: Dr. Askenazi is a speaker for The National Kidney Foundation.

References

- 1.Patel RM, Kandefer S, Walsh MC, Bell EF, Carlo WA, Laptook AR, Sanchez PJ, Shankaran S, Van Meurs KP, Ball MB, Hale EC, Newman NS, Das A, Higgins RD, Stoll BJ Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child H, Human Development Neonatal Research N. Causes and timing of death in extremely premature infants from 2000 through 2011. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:331–340. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1403489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coca SG, Yusuf B, Shlipak MG, Garg AX, Parikh CR. Long-term risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:961–973. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chawla LS, Eggers PW, Star RA, Kimmel PL. Acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease as interconnected syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:58–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1214243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim SM, Lee EY, Chen J, Ringer SA. Improved care and growth outcomes by using hybrid humidified incubators in very preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e137–145. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saeidi B, Koralkar R, Griffin RL, Halloran B, Ambalavanan N, Askenazi DJ. Impact of gestational age, sex, and postnatal age on urine biomarkers in premature neonates. Pediatr Nephrol. 2015;30:2037–2044. doi: 10.1007/s00467-015-3129-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Askenazi DJ, Koralkar R, Levitan EB, Goldstein SL, Devarajan P, Khandrika S, Mehta RL, Ambalavanan N. Baseline values of candidate urine acute kidney injury biomarkers vary by gestational age in premature infants. Pediatr Res. 2011;70:302–306. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182275164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Askenazi DJ, Griffin R, McGwin G, Carlo W, Ambalavanan N. Acute kidney injury is independently associated with mortality in very low birthweight infants: a matched case-control analysis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24:991–997. doi: 10.1007/s00467-009-1133-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koralkar R, Ambalavanan N, Levitan EB, McGwin G, Goldstein S, Askenazi D. Acute kidney injury reduces survival in very low birth weight infants. Pediatric Res. 2011;69:354–358. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31820b95ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Askenazi DJ, Koralkar R, Hundley HE, Montesanti A, Patil N, Ambalavanan N. Fluid overload and mortality are associated with acute kidney injury in sick near-term/term neonate. Pediatric Nephrol. 2013;28:661–666. doi: 10.1007/s00467-012-2369-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gadepalli SK, Selewski DT, Drongowski RA, Mychaliska GB. Acute kidney injury in congenital diaphragmatic hernia requiring extracorporeal life support: an insidious problem. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:630–635. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaur S, Jain S, Saha A, Chawla D, Parmar VR, Basu S, Kaur J. Evaluation of glomerular and tubular renal function in neonates with birth asphyxia. Ann Trop Paediatr. 2011;31:129–134. doi: 10.1179/146532811X12925735813922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alabbas A, Campbell A, Skippen P, Human D, Matsell D, Mammen C. Epidemiology of cardiac surgery-associated acute kidney injury in neonates: a retrospective study. Pediatr Nephrol. 2013;28:1127–1134. doi: 10.1007/s00467-013-2454-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Selewski DT, Jordan BK, Askenazi DJ, Dechert RE, Sarkar S. Acute kidney injury in asphyxiated newborns treated with therapeutic hypothermia. J Peidatr. 2013;162:725–729. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zwiers AJ, de Wildt SN, Hop WC, Dorresteijn EM, Gischler SJ, Tibboel D, Cransberg K. Acute kidney injury is a frequent complication in critically ill neonates receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a 14-year cohort study. Crit Care. 2013;17:R151. doi: 10.1186/cc12830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rhone ET, Carmody JB, Swanson JR, Charlton JR. Nephrotoxic medication exposure in very low birth weight infants. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27:1485–1490. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.860522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morgan CJ, Zappitelli M, Robertson CM, Alton GY, Sauve RS, Joffe AR, Ross DB, Rebeyka IM. Risk factors for and outcomes of acute kidney injury in neonates undergoing complex cardiac surgery. J Pediatr. 2013;162:120–127. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carmody JB, Swanson JR, Rhone ET, Charlton JR. Recognition and Reporting of AKI in Very Low Birth Weight Infants. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9:2036–2043. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05190514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khwaja A. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Acute Kidney Injury. Nephron Clin Pract. 2012;120:c179–184. doi: 10.1159/000339789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, Levin A. Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN): report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11:R31. doi: 10.1186/cc5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abosaif NY, Tolba YA, Heap M, Russell J, El Nahas AM. The outcome of acute renal failure in the intensive care unit according to RIFLE: model application, sensitivity, and predictability. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:1038–1048. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jetton JG, Askenazi DJ. Update on acute kidney injury in the neonate. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2012;24:191–196. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32834f62d5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oh W, Poindexter BB, Perritt R, Lemons JA, Bauer CR, Ehrenkranz RA, Stoll BJ, Poole K, Wright LL. Association between fluid intake and weight loss during the first ten days of life and risk of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in extremely low birth weight infants. J Pediatr. 2005;147:786–790. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bell EF, Acarregui MJ. Restricted versus liberal water intake for preventing morbidity and mortality in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;12:CD000503. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Basu RK, Andrews A, Krawczeski C, Manning P, Wheeler DS, Goldstein SL. Acute kidney injury based on corrected serum creatinine is associated with increased morbidity in children following the arterial switch operation. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14:e218–224. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182772f61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu KD, Thompson BT, Ancukiewicz M, Steingrub JS, Douglas IS, Matthay MA, Wright P, Peterson MW, Rock P, Hyzy RC, Anzueto A, Truwit JD. Acute kidney injury in patients with acute lung injury: Impact of fluid accumulation on classification of acute kidney injury and associated outcomes. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:2665–2671. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318228234b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thongprayoon C, Cheungpasitporn W, Srivali N, Ungprasert P, Kittanamongkolchai W, Kashani K. The impact of fluid balance on diagnosis, staging and prediction of mortality in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. J Nephrol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s40620-015-0211-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson HL, 3rd, Coran AG, Drongowski RA, Ha HJ, Bartlett RH. Extracellular fluid and total body water changes in neonates undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Pediatr Surg. 1992;27:1003–1007. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(92)90547-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hartnoll G, Betremieux P, Modi N. Randomised controlled trial of postnatal sodium supplementation on body composition in 25 to 30 week gestational age infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2000;82:F24–28. doi: 10.1136/fn.82.1.F24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jobe AH, Bancalari E. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;13:1723–1729. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.2011060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shima Y, Kumasaka S, Migita M. Perinatal risk factors for adverse long-term pulmonary outcome in premature infants: comparison of different definitions of bronchopulmonary dysplasia/chronic lung disease. Pediatr Int. 2013;55:578–581. doi: 10.1111/ped.12151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Groothuis JR, Makari D. Definition and outpatient management of the very low-birth-weight infant with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Adv Ther. 2012;29:297–311. doi: 10.1007/s12325-012-0015-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Natarajan G, Pappas A, Shankaran S, Kendrick DE, Das A, Higgins RD, Laptook AR, Bell EF, Stoll BJ, Newman N, Hale EC, Bara R, Walsh MC. Outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia: impact of the physiologic definition. Early Hum Dev. 2012;88:509–515. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.