Abstract

BACKGROUND

Cardiac surgery requiring cardiopulmonary bypass is associated with platelet activation. Since platelets are increasingly recognized as important effectors of ischemia and end-organ inflammatory injury, we explored whether postoperative nadir platelet counts are associated with acute kidney injury (AKI) and mortality after coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery.

METHODS

We evaluated 4,217 adult patients who underwent CABG surgery. Postoperative nadir platelet counts were defined as the lowest in-hospital values, and were used as a continuous predictor of postoperative AKI and mortality. Nadir values in the lowest 10th percentile were also used as a categorical predictor. Multivariable logistic regression and Cox proportional hazard models examined the association between postoperative platelet counts, postoperative AKI, and mortality.

RESULTS

The median postoperative nadir platelet count was 121 × 109/L. The incidence of postoperative AKI was 54%, including 9.5% (215 patients) and 3.4% (76 patients) who experienced stages II and III AKI, respectively. For every 30×109/L decrease in platelet counts, the risk for postoperative AKI increased by 14% (odds ratio [OR], 1.14; 95% CI, 1.09 – 1.20; P < 0.0001). Patients with platelet counts in the lowest 10th percentile were 3 times more likely to progress to a higher severity of postoperative AKI (adjusted proportional OR, 3.04; 95%CI, 2.26 – 4.07; P < 0.0001), and had associated increased risk for mortality immediately after surgery (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 5.46; 95%CI, 3.79 – 7.89; P < 0.0001).

CONCLUSIONS

We found a significant association between postoperative nadir platelet counts, and AKI and short-term mortality after CABG surgery.

Keywords: coronary artery bypass grafting surgery, thrombocytopenia, acute kidney injury, mortality

TOC Statement

The authors performed a retrospective observational study of the association between postoperative nadir platelet counts, AKI and mortality in CABG surgery. The authors found a significant independent association between postoperative nadir platelet counts, AKI and mortality after CABG surgery. The work suggests potential platelet related ischemic events during CABG surgery warrant further investigation.

INTRODUCTION

In the setting of cardiac surgery, postoperative acute kidney injury (AKI) remains a common and a serious postoperative complication that affects 30%–51% of patients, with up to approximately 3% requiring renal replacement therapy.1–3 The physiopathology of postoperative AKI is complex, and involves multiple factors such as advanced age, preexisting kidney injury, diabetes mellitus, ischemia-reperfusion injury, altered regional blood flow with vasomotor dysfunction, and inflammatory responses.2,4–8 If the injury progresses to acute renal failure, the survival rate is markedly reduced,9 resource utilization is quadrupled,1 and the quality of life for both patients and their families is often significantly diminished.10

Platelet activation during cardiac surgery is well recognized, and several studies have shown its role in bleeding, postoperative procoagulable state, and in resultant macrothrombotic complications such as perioperative stroke or myocardial infarction.11 Nevertheless, cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) has also been shown to promote formation of microemboli consisting of fibrin, activated leukocytes, and aggregated platelets. Consequently, the resulting microvascular plugging with leukocytes and activated platelets may be pivotal in the pathogenesis of postoperative AKI,12 similarly as it has been observed in sepsis-induced kidney injury. In addition, recent evidence supports the role of platelets as potent and ubiquitously present sources of inflammatory activation,13,14 in defining endothelial responses and neutrophil recruitment in ischemia/reperfusion injury including distant organ injury15 and postischemic renal failure.16

It is noteworthy that thrombocytopenia is one of the most common laboratory abnormalities in critically ill patients, and has been attributed in this setting to increased platelet destruction (immune and non-immune), hemodilution, platelet sequestration, or decreased production. Importantly, such thrombocytopenia is closely associated with prolonged ICU length of stay, reduced survival and increased incidence of AKI.17,18

While a significant drop in platelet counts is prevalent after CPB, the implications of this finding have never been comprehensively examined in a cardiac surgical patient cohort. Therefore, in the present study, we characterized the incidence and course of postoperative thrombocytopenia in a cohort of patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery. Our objective was to determine whether a decrease in platelet count after CABG surgery is independently associated with increased risk for postoperative AKI and mortality.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Study Population

After approval by the Institutional Review Board for Clinical Investigations, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA, we conducted this retrospective observational study on patients over 18 years of age who underwent CABG surgery with CPB at Duke University Medical Center (Durham, North Carolina) from January 1, 2001 to November 30, 2009. From this group of 5,339 patients, we excluded patients who had off-pump CABG (n = 759), emergency surgery (n = 308), a concomitant procedure other than CABG (n = 2), a second cardiac surgery during the same hospital stay (n = 43), missing platelet counts (n = 7), or missing pre- and postoperative serum creatinine values (n = 3). The remaining 4,217 were included in the present study.

Data Collection

A standard set of perioperative data were collected from the Duke University Medical Center databases, including the Duke Perioperative Electronic Database (Innovian® Anesthesia; Draeger Medical Inc., Telford, PA), Cardiac Surgery Quality Assurance Database, Duke Databank for Cardiovascular Diseases, and the patients’ electronic medical records. Two independent investigators (MDK and WDW) verified the data quality by performing regular crosschecks for completeness and consistency between the data set assembled and the information available from the Duke databases.

Clinical Risk Factors

The clinical risk factors for postoperative AKI and all-cause mortality included patient characteristics, preoperative and intraoperative cardiovascular medication use, the European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation score (EuroSCORE),19 CPB and aortic cross-clamp time, insertion of intraoperative balloon pump, intraoperative and postoperative blood transfusions, pre- and postoperative serum creatinine values, and platelet counts. According to institutional practice, preoperative antiplatelet therapy with aspirin was maintained until the day before surgery; clopidogrel was discontinued for ≥ 7 days before surgery; and warfarin was discontinued 4 days before surgery and “bridged” with intravenous heparin infusion.

Serum creatinine was measured preoperatively in the Duke Clinical Pathology Laboratory and for the first 10 days postoperatively per institutional protocol, as described by Sickeler et al.20 The normal range was 0.4–1.0 mg/dL (31–76 μmol/L) for women, and 0.6–1.3 mg/dL (46–99 μmol/L) for men. Preoperative serum creatinine values were recorded during the week before the index CABG procedure, on the day that was closest to, but not on the day of, surgery.20

Per institutional protocol, platelet counts were also measured preoperatively in the Duke Clinical Pathology Laboratory and for the first 10 days postoperatively or until discharge, whichever came first. Minimum (nadir) platelet counts were defined as the lowest in-hospital values measured for the first 10 postoperative days or until the day of hospital discharge, and were subsequently used as a continuous predictor of postoperative AKI and mortality. Further, postoperative nadir values in the lowest 10th percentile were used as a categorical predictor, and as a threshold for clinical characterization of those patients with the most profound postoperative thrombocytopenia.

Similarly, serum hemoglobin concentrations were measured per institutional protocol preoperatively and for the first 10 days postoperatively or until discharge, whichever came first. Minimum (nadir) serum hemoglobin concentrations were defined as the lowest in-hospital values measured over the first 10 postoperative days or to day of hospital discharge, and were subsequently used as adjustment variables in our analyses of postoperative AKI and mortality.

Classification of Outcomes

The primary outcome chosen was acute kidney injury (AKI), ascertained and categorized according to the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Clinical Practice Guidelines21 with modification due to the absence of urine output data. In brief, postoperative AKI was defined using preoperative serum creatinine values (baseline) that were collected 3 days prior to surgery and all available serum creatinine values that were measured for the first 10 days postoperatively or until discharge, whichever came first. The presence of postoperative AKI was ascertained when there was postoperative serum creatinine rise ≥ 50% in the first 10 postoperative days, or 0.3 mg/dL (26.5 μmol/L) increase detected using a rolling 48-hour window across the 10-day postoperative period. A staging characterization of postoperative AKI was also generated as follows: (1) stage I – risk: those meeting the AKI criteria but not as severe as stages II and III; (2) stage II – injury: those with 2.0–2.9-fold rise of serum creatinine (ie, 100%–200% increase) within 10 days; (3) stage III – failure: those with ≥ 3.0-fold rise of serum creatinine (ie, ≥ 200% increase) within 10 days or ≥ 4 mg/dL [353.6 μmol/L] increase in a rolling 48-hour window. The secondary outcome was long-term all-cause mortality. Survival information for the secondary outcomes was obtained from Duke Clinical Research Institute Follow-up Services Group, which is responsible for collecting annual follow-up data on death for the Duke Databank for Cardiovascular Diseases.22

STATISTICS

Summary statistics are presented as means (± SD) or medians (interquartile range) for continuous variables, or as group frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Kruskal-Wallis or chi-square tests were used for descriptive group comparisons of those with and without thrombocytopenia.

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models were applied to evaluate the association between clinical risk factors, as described under “Clinical Risk Factors,” and postoperative AKI. Univariable associations with P < 0.10 were evaluated by means of a forward stepwise technique to derive the final multivariate logistic regression model containing variables with P < 0.05. Continuous variables (ie, age, serum creatinine values, hemoglobin and platelet counts, EuroSCORE, duration of cardiopulmonary bypass time) were evaluated for nonlinearity using empirical logit plots on the deciles of these continuous variables, and transformations were performed if warranted. The fit of the final multivariable logistic regression analysis was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test, and the discriminatory power was quantified by the c-index. The c-index, which equals the area under the receiver operating characteristics curve, ranges from 0.5 (performance at chance) to 1.0 (optimal performance).23

We assessed the degree of overoptimism of the final multivariable logistic regression analysis by using the bootstrap method. First, covariates in the final regression models were fitted for each bootstrap sample. The original dataset was then fitted using coefficients of the bootstrap sample model. Subsequently, a c-index statistic was generated from this fit on the original dataset, and the degree of overoptimism was then estimated as the difference in the c-index statistic from the bootstrap sample and from the bootstrap model fit on the original sample. These differences were averaged across 1,000 bootstrapped samples, and the difference in the original model c-index statistic and the average optimism provided the model c-index corrected for overoptimism.24,25

In a subsequent analysis, a stepwise proportional odds model (ordinal logistic regression) was conducted to determine the association between postoperative nadir platelet counts and the different stages of postoperative AKI, adjusted for clinical characteristics. A stepwise multivariable proportional odds model (ordinal logistic regression) testing variables with P < 0.05 from the final multivariable logistic regression model was conducted to determine the association between postoperative nadir platelet counts and the different stages of postoperative AKI, respectively. The proportional odds assumption was assessed with a score test.

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to describe the unadjusted prognostic importance of nadir platelet counts and postoperative AKI with respect to event-free survival. Differences between survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. The Cox model proportional hazards assumption was evaluated using the Kolmogorov-type supremum test on 1,000 simulated score process patterns. For variables with supremum test P < 0.5, we plotted the hazard ratio over time against the weighted Schoenfeld residuals. If a variable demonstrated significant non-proportional effects, we introduced time-varying covariates with cut points determined by maximizing the model partial log likelihoods, and then fit separate hazard functions before and after the cut points.26 Linearity of continuous variables was assessed via plots of Martingale residuals; and if a violation was identified, transformations were performed. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression models were then applied to assess the association of postoperative thrombocytopenia and AKI with mortality. If there is a potential for using time-varying covariates for variables that may have violated the proportional hazards assumption, the discriminatory ability and calibration of the final multivariable Cox regression model cannot be assessed because the hazard is not constant over time. In such instances, a multivariable regression model using a full set of clinical variables can be considered to adjust for all variables that may bias the estimate of the association between platelet counts and mortality.

A series of sensitivity analyses were also performed to determine whether the observed association between thrombocytopenia and outcomes was affected by changing the cut-off value for the definition of postoperative thrombocytopenia from the lowest 10th percentile to the standard clinical definition of < 100 × 109/L,27 by excluding patients with preoperative serum creatinine > 2 mg/dL (> 180 μmol/L) and preoperative platelet counts ≤ to the lowest 10th percentile, by excluding patients from the association analysis for postoperative AKI who died within 10 days of surgery, and by excluding patients with HIT (heparin-induced thrombocytopenia). The presence of HIT was ascertained from reviewing the electronic medical recordkeeping system for postoperative progress notes for the diagnosis of HIT, and by searching and identifying the results of laboratory screening tests for a positive test result for detecting human platelet factor 4/heparin complex antibodies using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Odds ratios or hazard ratios, and corresponding 95% confidence limits are reported. All analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

The 4,217 patients studied were separated into 2 groups according to postoperative platelet counts: 1) the lowest 10th percentile, or thrombocytopenic cohort, (platelet counts ≤ 74 × 109/L; n = 428), and 2) remaining patients (n = 3,789). The 25th and the 50th percentile (median) for postoperative nadir platelet counts were 96 × 109/L and 121 × 109/L, respectively. Figure 1, Supplemental Digital Content shows daily mean minimum postoperative platelet counts. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the 2 groups are compared in Table 1. There were several notable differences between the groups, including age, female sex, medical history, comorbidities, previous and intraoperative cardiovascular medication use, and intraoperative characteristics.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population, n = 4,217

| Characteristics | Patients with nadir platelet ≤ 74 × 109/L (n = 428) | Patients with nadir platelet > 74 × 109/L (n = 3789) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Demographics | |||

| Age categories, years | < 0.0001 | ||

| <55 | 44 (10.3) | 810 (21.4) | |

| 55–64 | 105 (24.5) | 1186 (31.3) | |

| 65–74 | 147 (34.4) | 1200 (31.7) | |

| 75–84 | 115 (26.9) | 551 (14.5) | |

| >84 | 17 (3.9) | 42 (1.1) | |

| Race | 0.771 | ||

| White | 329 (76.9) | 2900 (76.5) | |

| African American | 74 (17.3) | 706 (18.6) | |

| Hispanic | 3 (0.7) | 20 (0.5) | |

| Asian | 6 (1.4) | 32 (0.8) | |

| American Indian | 16 (3.7) | 127 (3.4) | |

| Other | 0 | 4 (0.1) | |

| Female sex | 153 (35.8) | 1020 (26.9) | 0.0001 |

|

| |||

| Medical history* | |||

| EuroSCORE-related variables | |||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 74 (17.3) | 550 (14.5) | 0.126 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 87 (20.3) | 618 (16.3) | 0.035 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 43 (9.7) | 366 (10.1) | 0.798 |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 7 (1.6) | 31 (0.8) | 0.089 |

| Serum creatinine > 2 mg/dL | 36 (8.4) | 191 (5) | 0.003 |

| Critical preoperative state | 14 (3.3) | 53 (1.4) | 0.003 |

| Unstable angina pectoris | 50 (11.7) | 415 (10.9) | 0.648 |

| Left ventricular function | < 0.0001 | ||

| Normal | 168 (39.2) | 1918 (50.6) | |

| Moderate dysfunction | 192 (44.9) | 1526 (40.3) | |

| Severe dysfunction | 68 (15.9) | 345 (9.1) | |

| Recent myocardial infarction | 113 (26.4) | 950 (25.1) | 0.548 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 7 (1.6) | 22 (0.6) | 0.012 |

| Emergency cardiac surgery | – | – | – |

| Post-infarct septal rupture | – | – | – |

| Average logistic EuroSCORE, % | 5.0 [2.7–10.1] | 3.0 [1.6–5.8] | < 0.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 162 (37.4) | 1416 (37.8) | 0.846 |

|

| |||

| Laboratory tests results | |||

| Preoperative: | 1.1 [0.9–1.4] | 1.0 [0.9–1.2] | < 0.0001 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | |||

| Platelet count, 109/L | 170.7 ± 58.2 | 227.8 ± 69.3 | < 0.0001 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 12.7 ± 1.9 | 13.1 ± 1.9 | 0.007 |

| Postoperative | |||

| Nadir platelet count, 109/L | 59.9 ± 12.9 | 134.7 ± 41.9 | < 0.0001 |

| Nadir hemoglobin, g/dL | 8.7 ± 1.1 | 8.9 ± 1.2 | < 0.0001 |

|

| |||

| Preoperative medications† | |||

| Acetylsalicylic acid | 277 (66.3) | 2432 (65.1) | 0.649 |

| Alpha-receptor blockers | 24 (5.7) | 221 (5.9) | 0.883 |

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors | 180 (43.1) | 1578 (42.3) | 0.756 |

| Angiotensin II receptor antagonist | 38 (9.1) | 348 (9.3) | 0.877 |

| Beta-receptor blockers | 254 (60.8) | 2166 (58) | 0.281 |

| Calcium-channel blockers | 76 (18.2) | 710 (19) | 0.679 |

| Clopidogrel | 65 (15.6) | 499 (13.4) | 0.217 |

| Diuretics | 157 (37.6) | 1108 (29.7) | 0.0009 |

| Nitrates | 150 (35.9) | 1123 (30.1) | 0.015 |

| Statins | 213 (51) | 1949 (52.2) | 0.627 |

| Warfarin | 27 (6.5) | 139 (3.7) | 0.007 |

|

| |||

| Intraoperative characteristics | |||

| Year of surgery | 0.046 | ||

| 2001 | 97 (22.7) | 655 (17.3) | |

| 2002 | 77 (18) | 605 (16) | |

| 2003 | 44 (10.3) | 480 (12.7) | |

| 2004 | 36 (8.4) | 376 (9.9) | |

| 2005 | 48 (11.2) | 353 (9.3) | |

| 2006 | 30 (7) | 361 (9.5) | |

| 2007 | 34 (7.9) | 331 (8.7) | |

| 2008 | 34 (7.9) | 313 (8.3) | |

| 2009 | 28 (6.5) | 315 (8.3) | |

| Duration of cardiopulmonary bypass, minutes | 146.7 ± 55.6 | 122.2 ± 39.9 | < 0.0001 |

| Duration of aortic cross clamp, minutes | 76.4 ± 32.3 | 67.6 ± 27.9 | < 0.0001 |

| Intraoperative insertion of intra-aortic balloon pump | 97 (22.7) | 259 (6.8) | < 0.0001 |

|

| |||

| Intraoperative medications | |||

| Aminocaproic acid | 297 (69.4) | 2981 (78.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Aprotinin | 106 (24.8) | 648 (17.1) | < 0.0001 |

| Epinephrine | 269 (62.9) | 1682 (44.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Norepinephrine | 51 (11.9) | 169 (4.5) | < 0.0001 |

| Vasopressin | 84 (19.6) | 404 (10.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Nitroprusside | 187 (43.7) | 1506 (39.8) | 0.114 |

| Nitroglycerin | 304 (71) | 2745 (72.4) | 0.534 |

| Esmolol | 15 (3.5) | 106 (2.8) | 0.406 |

| Metoprolol | 278 (64.9) | 2624 (69.3) | 0.069 |

|

| |||

| Perioperative blood product use within 2 days, unit | |||

| Red blood cells | 5 [3–8] | 2 [0–4] | < 0.0001 |

| Fresh frozen plasma | 1 [0–4] | 0 [0–1] | < 0.0001 |

| Platelets | 1 [0–3] | 0 [0–1] | < 0.0001 |

| Cryoprecipitate | 0 [0–0] | 0 [0–0] | 0.0004 |

Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, median [interquartile range], or n (%).

The definitions of these risk factors were based on the definitions used by the European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation (EuroSCORE) scoring system.19

Due to missing numbers (%), preoperative medication use was computed for n = 418 patients in the 10th percentile group with a nadir platelet count ≤ 74 × 109/L, and for n = 3733 patients with a nadir platelet count > 74 × 109/L.

Postoperative Acute Kidney Injury

Given the definition we used for AKI, which had to occur within 10 days after surgery, 8 patients who died within 10 days before developing AKI were excluded from our subsequent analysis for postoperative AKI. According to KDIGO criteria,21 the overall incidence of postoperative AKI was 54% (n = 2,267), of which 87% (n = 1,976), 9.5% (n = 215), and 3.4% (n = 76) met criteria for stages I, II, and III AKI, respectively. In the thrombocytopenic cohort (n = 428), the incidence was 51% (n = 219), 13% (n = 57), and 7% (n = 30); whereas, in the remaining population (90th percentile; n = 3,781), the incidence was 46% (n = 1,757), 4% (n = 158), and 1% (n = 46), respectively, for stages I, II, and III postoperative AKI. Figure 2, Supplemental Digital Content compares nadir platelet counts and estimated risk for postoperative AKI. Several preoperative and intraoperative variables in the univariable analysis were significantly associated with an increased risk for postoperative AKI (Table 2). Testing the assumption of linearity revealed that the only non-linear continuous variable was preoperative serum creatinine. Postoperative nadir platelet counts, defined as platelet counts ≤ 74 × 109/L (univariable OR, 2.33; 95% CI, 1.87–2.90; P < 0.0001) or as a continuous variable, for every 30 × 109/L decrease (univariable OR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.17–1.27; P < 0.0001), were also associated with postoperative AKI. According to multivariable analysis, the following predictors emerged as independent risk factors for postoperative AKI: age, female sex, race, severity of left ventricular dysfunction, diabetes mellitus, preoperative serum creatinine values > 2 mg/dL, preoperative platelet count, preoperative hemoglobin, preoperative calcium-channel blockers, duration of CPB, intraoperative use of aprotinin, postoperative nadir hemoglobin, and red blood cell transfusions (Table 2). After adjusting for differences in baseline and clinical characteristics, postoperative thrombocytopenia showed a strong association with postoperative AKI (Table 2). The multivariable logistic regression model for postoperative AKI showed good discriminative ability (c-index = 0.705). The degree of overoptimism was minimal (0.005), and the adjusted c-index became 0.703. The overall goodness-of-fit Hosmer-Lemeshow test showed a good fit (chi-square test = 8.34; P = 0.401). Multivariable analysis that incorporated postoperative platelet count as a continuous variable showed that, for every 30 × 109/L decrease in platelet count, the risk for postoperative AKI increased by 14% (multivariable OR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.09–1.20; P < 0.0001).

Table 2.

Univariable and multivariable predictors of postoperative acute kidney injury

| Predictors | Univariable

|

Multivariable*

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P value | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P value | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age at surgery, per 5-year increase | 1.17 (1.13–1.20) | < 0.0001 | 1.15 (1.11–1.19) | < 0.0001 |

| Race | < 0.0001 | 0.0003 | ||

| White | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| African American | 1.72 (1.46–2.02) | 1.43 (1.19–1.72) | ||

| Other | 0.98 (0.74–1.30) | 0.91 (0.67–1.24) | ||

| Female sex | 1.22 (1.07–1.40) | 0.004 | 0.84 (0.71–0.99) | 0.039 |

| Clinical risk factors | ||||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1.21 (1.02–1.44) | 0.030 | ||

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.63 (1.38–1.93) | < 0.0001 | ||

| Cerebrovascular accident | 1.38 (1.12–1.71) | 0.002 | ||

| Previous cardiac surgery | 1.32 (0.69–2.53) | 0.409 | ||

| Preoperative serum creatinine > 2 mg/dL | 22.85 (11.70–44.36) | < 0.0001 | 13.35 (7.15–28.43) | < 0.0001 |

| Critical preoperative state | 0.83 (0.51–1.34) | 0.444 | ||

| Unstable angina pectoris | 1.12 (0.92–1.36) | 0.257 | ||

| Left ventricular function | < 0.0001 | 0.018 | ||

| Normal | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Moderate dysfunction | 1.37 (1.21–1.60) | 1.21 (1.15–1.52) | ||

| Severe dysfunction | 1.32 (1.07–1.63) | 0.98 (0.79–1.25) | ||

| Recent myocardial infarction | 1.06 (0.92–1.22) | 0.431 | ||

| Pulmonary hypertension | 2.26 (0.99–5.11) | 0.051 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.52 (1.34–1.73) | < 0.0001 | 1.32 (1.15–1.52) | < 0.0001 |

| Laboratory tests | ||||

| Preoperative hemoglobin, per 1 g/dL increase | 0.79 (0.77–0.82) | < 0.0001 | 0.88 (0.85–0.92) | < 0.0001 |

| Preoperative platelet count, per 30 × 109/L increase | 0.82 (0.79–0.85) | < 0.0001 | 0.96 (0.93–0.99) | 0.017 |

| Postoperative Thrombocytopenia, platelet count ≤ 74 × 109/L | 2.33 (1.87–2.90) | < 0.0001 | 1.57 (1.23–2.01) | 0.0003 |

| Postoperative nadir hemoglobin, per 1 g/dL increase | 0.84 (0.80–0.89) | < 0.0001 | 0.85 (0.80–0.90) | < 0.0001 |

| Preoperative medications | ||||

| Acetylsalicylic acid | 0.93 (0.82–1.06) | 0.309 | ||

| Alpha-receptor blockers | 1.55 (1.18–2.02) | 0.001 | ||

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors | 1.01 (0.89–1.14) | 0.868 | ||

| Angiotensin II receptor antagonist | 1.44 (1.16–1.79) | 0.0009 | ||

| Beta-receptor blockers | 1.13 (1.0–1.28) | 0.044 | ||

| Calcium-channel blockers | 1.67 (1.42–1.96) | < 0.0001 | 1.32 (1.11–1.57) | 0.002 |

| Clopidogrel | 1.18 (0.99–1.41) | 0.07 | ||

| Diuretics | 1.31 (1.15–1.50) | < 0.0001 | ||

| Nitrates | 1.17 (1.03–1.34) | 0.021 | ||

| Statins | 0.97 (0.86–1.09) | 0.594 | ||

| Warfarin | 1.55 (1.12–2.13) | 0.0008 | ||

| Intraoperative characteristics | ||||

| Year of surgery, per year increase | 0.99 (0.96–1.01) | 0.260 | ||

| Duration of cardiopulmonary bypass, per 30-minute increase | 1.16 (1.11–1.22) | < 0.0001 | 1.10 (1.05–1.16) | 0.0001 |

| Duration of aortic cross clamp, per 30-minute increase | 1.15 (1.08–1.23) | < 0.0001 | ||

| Intraoperative insertion of intra-aortic balloon pump | 1.16 (0.93–1.44) | 0.190 | ||

| Intraoperative medications | ||||

| Aminocaproic acid | 0.57 (0.49–0.67) | < 0.0001 | ||

| Aprotinin | 2.10 (1.78–2.49) | < 0.0001 | 1.71 (1.43–2.06) | < 0.0001 |

| Epinephrine | 1.36 (1.20–1.53) | < 0.0001 | ||

| Norepinephrine | 1.17 (0.89–1.54) | 0.263 | ||

| Vasopressin | 1.29 (1.07–1.56) | 0.009 | ||

| Nitroprusside | 1.18 (1.04–1.33) | 0.009 | ||

| Nitroglycerin | 1.08 (0.94–1.23) | 0.296 | ||

| Esmolol | 1.27 (0.88–1.83) | 0.207 | ||

| Metoprolol | 0.84 (0.73–0.95) | 0.008 | ||

| Perioperative blood product use within 2 days | ||||

| Red blood cells | 2.11 (1.84–2.42) | < 0.0001 | 1.30 (1.11–1.53) | 0.001 |

| Fresh Frozen Plasma | 1.52 (1.32–1.74) | < 0.0001 | ||

| Platelets | 1.43 (1.26–1.63) | < 0.0001 | ||

| Cryoprecipitate | 1.41 (1.04–1.93) | 0.03 | ||

The final multivariable logistic regression analysis was based on n = 4,143 due to missing information (n = 66) on preoperative medication use. In addition, given the definition we used for acute kidney injury, which had to occur within 10 days after surgery, 8 patients who died within 10 days before developing acute kidney injury were also excluded from the multivariable analysis.

Finally, a proportional odds model was analyzed in the 2,267 patients with postoperative AKI. The final multivariate model satisfied the score test of the proportionality assumption (P = 0.457) and had a fair c-index of 0.644. After adjusting for other clinical variables, patients with postoperative thrombocytopenia were more likely to progress to more severe postoperative AKI (OR, 3.04; 95% CI, 2.26–4.07; P < 0.0001; Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable predictors of severity of postoperative acute kidney injury*

| Predictors | Proportional Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Thrombocytopenia, platelet count ≤ 74 × 109/L | 3.04 (2.26–4.07) | < 0.0001 |

| Duration of cardiopulmonary bypass, per 30-minute increase | 1.19 (1.11–1.28) | < 0.0001 |

| Postoperative nadir hemoglobin, per 1 g/dL increase | 0.83 (0.74–0.93) | 0.001 |

Multivariable proportional odds model based on n = 2,267 patients who have postoperative acute kidney injury stage I, II or III. Clinical variables with P < 0.05 from the final multivariable regression model for predicting postoperative acute kidney injury as a binary outcome variable were selected and tested in this model using a stepwise selection method. This model excluded cases without postoperative acute kidney injury because the score test (see Methods) indicated that testing for these patients violated the proportional odds assumption. This model gives odds ratios for increase in risk for worsening stages of postoperative acute kidney injury, ie, from stage I to II, or from stage II to III, as defined by the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Clinical Practice Guidelines.21

Long-term Mortality

Patients were followed until November 9, 2011, the median duration of follow-up was 5.11 years [25th and 75th interquartile, 2.61 and 8.02]. The incidence of overall all-cause mortality was 26% (1,107/4,217), and 30-day mortality was 1.5% (65/4,217).

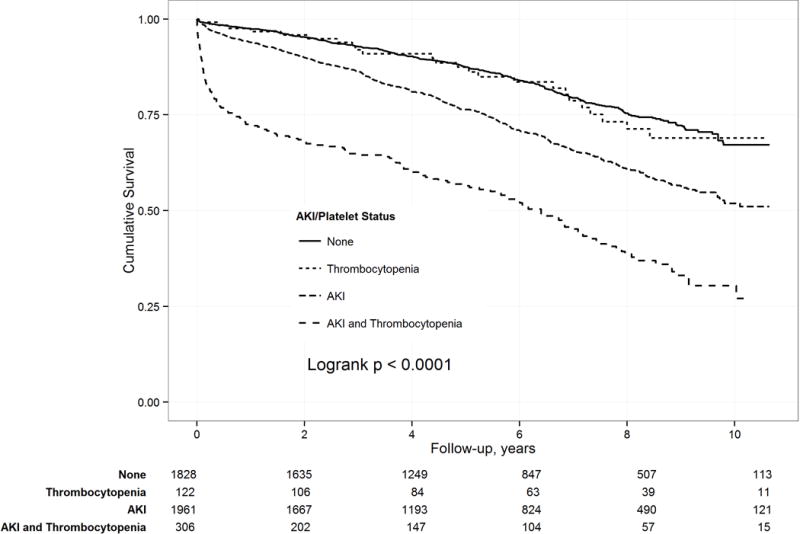

Figure 1 compares the incidence of postoperative AKI and thrombocytopenia, with event-free survival over the follow-up period. Patients experiencing combined AKI and thrombocytopenia had the lowest event-free survival, compared to patients who had either AKI or thrombocytopenia, or who had neither AKI nor thrombocytopenia.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of long-term mortality in relation to postoperative thrombocytopenia and acute kidney injury (AKI).

Our evaluation of proportionality indicated that the thrombocytopenia defined as postoperative nadir platelet counts ≤ 74 × 109/L, and postoperative AKI variables were the only covariates demonstrating significant non-proportional hazards and time-varying effects. For thrombocytopenia, the residual plot and model likelihood analysis indicated a linearly declining log HR until 14 months (1.18 years), and then a constant log HR for the remainder of follow-up (see Figure 3, Supplemental Digital Content). There was a similar pattern observed for postoperative AKI with a linearly declining log HR until 18 months (1.51 years), and then a constant log HR for the remainder of follow-up (see Figure 4, Supplemental Digital Content). Our evaluation of linearity found that it was necessary to use a reciprocal transformation of the continuous measure of postoperative nadir platelet counts, and the individual risk factors of EuroSCORE since no transformation of the EuroSCORE variable attained linearity. Univariable predictors of long-term mortality are shown in Table 4. Again, many preoperative and intraoperative characteristics were associated with an increased risk for long-term mortality. The univariable analysis showed a significant association between postoperative thrombocytopenia and long-term mortality (Table 4). After adjusting for differences in baseline and clinical characteristics, thrombocytopenia was associated with increased risk for mortality immediately after surgery (adjusted HR, 5.46; 95% CI, 3.79–7.89; P < 0.0001), which then decreased linearly by 50% every 6 months until 14 months (1.18 years). Thereafter, the risk remained constant but was no longer significant (adjusted HR, 1.06, 95% CI, 0.85–1.32; P = 0.618). Further, postoperative AKI was associated with an increased risk for mortality immediately after surgery (adjusted HR, 2.96; 95% CI, 1.88–4.67; P = 0.0006), which then decreased linearly by 25% every 6 months until 18 months (1.51 years). Thereafter, the risk remained constant and significantly elevated (adjusted HR, 1.27, 95% CI, 1.09–1.48; P = 0.002; Table 4). The multivariable analysis of postoperative nadir platelet counts as a transformed continuous variable demonstrated that while the value of the hazard ratio varied across platelet counts, lower nadir platelet counts were associated with a significantly increased short-term risk for mortality (P < 0.0001), which decreased until 14 months (1.18 years). Thereafter, the risk remained constant, but was no longer significant (P = 0.332).

Table 4.

Univariable and multivariable predictors of long-term mortality

| Predictors | Univariable

|

Multivariable*

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P value | Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P value | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age at surgery, per 5-year increase | 1.24 (1.21–1.28) | < 0.0001 | 1.21 (1.17–1.25) | <0.0001 |

| Race | 0.0021 | 0.7199 | ||

| White | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| African American | 1.29 (1.12–1.49) | 1.02 (0.87–1.20) | ||

| Other | 1.15 (0.88–1.51) | 1.12 (0.85–1.48) | ||

| Female sex | 1.22 (1.07–1.38) | 0.003 | 0.86 (0.74–1.0) | 0.048 |

| Clinical risk factors | ||||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1.94 (1.67–2.26) | < 0.0001 | 1.49 (1.27–1.75) | <0.0001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.94 (1.70–2.22) | < 0.0001 | 1.38 (1.19–1.60) | <0.0001 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 1.72 (1.45–2.02) | < 0.0001 | 1.24 (1.04–1.47) | 0.0191 |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 1.43 (0.84–2.42) | 0.186 | 1.21 (0.69–2.13) | 0.5115 |

| Preoperative serum creatinine > 2 mg/dL | 3.99 (3.34–4.77) | < 0.0001 | 2.38 (1.92–2.93) | <0.0001 |

| Critical preoperative state | 1.14 (0.72–1.79) | 0.580 | 0.95 (0.59–1.51) | 0.8123 |

| Unstable angina pectoris | 0.97 (0.82–1.14) | 0.681 | 0.94 (0.78–1.14) | 0.5357 |

| Left ventricular function | < 0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| Normal | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Moderate dysfunction | 1.52 (1.34–1.73) | 1.24 (1.08–1.42) | ||

| Severe dysfunction | 2.49 (2.08–2.98) | 1.70 (1.38–2.09) | ||

| Recent myocardial infarction | 1.25 (1.10–1.43) | 0.001 | 1.02 (0.88–1.18) | 0.7832 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 1.70 (0.94–3.08) | 0.0806 | 0.93 (0.49–1.77) | 0.8223 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.43 (1.27–1.61) | < 0.0001 | 1.23 (1.08–1.40) | 0.0015 |

| Laboratory tests | ||||

| Preoperative hemoglobin, per 1 g/dL increase | 0.78 (0.76–0.80) | < 0.0001 | 0.87 (0.83–0.91) | <0.0001 |

| Preoperative platelet count, per 30 × 109/L increase | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) | 0.9255 | 1.02 (1.0–1.05) | 0.1102 |

| Postoperative Thrombocytopenia, platelet count ≤ 74 × 109/L: | ||||

| Immediately Post Surgery | 8.13 (5.83–11.34) | <0.0001 | 5.46 (3.79–7.89) | <0.0001 |

| 14 months (1.18 years) and After | 1.40 (1.14–1.71) | 0.0012 | 1.06 (0.85–1.32) | 0.6175 |

| Postoperative nadir hemoglobin, per 1 g/dL increase | 1.01 (0.96–1.06) | 0.746 | 1.01 (0.95–1.07) | 0.7762 |

| Preoperative medications | ||||

| Acetylsalicylic acid | 0.75 (067–0.85) | <0.0001 | 0.79 (0.69–0.90) | 0.0005 |

| Alpha-receptor blockers | 1.24 (0.98–1.57) | 0.077 | 0.87 (0.68–1.12) | 0.2762 |

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors | 1.06 (0.94–1.20) | 0.343 | 1.02 (0.89–1.17) | 0.8083 |

| Angiotensin II receptor antagonist | 0.97 (0.78–1.21) | 0.799 | 0.86 (0.68–1.09) | 0.2019 |

| Beta-receptor blockers | 0.94 (0.84–1.06) | 0.333 | 0.94 (0.82–1.08) | 0.3939 |

| Calcium-channel blockers | 1.26 (1.09–1.46) | 0.002 | 0.98 (0.84–1.14) | 0.7544 |

| Clopidogrel | 1.10 (0.93–1.31) | 0.261 | 1.07 (0.89–1.28) | 0.4936 |

| Diuretics | 1.43 (1.26–1.62) | < 0.0001 | 1.04 (0.91–1.19) | 0.5473 |

| Nitrates | 1.17 (1.03–1.32) | 0.017 | 1.19 (1.04–1.37) | 0.0105 |

| Statins | 0.85 (0.75–0.96) | 0.007 | 0.90 (0.79–1.02) | 0.1059 |

| Warfarin | 1.69 (1.31–2.17) | < 0.0001 | 1.23 (0.95–1.60) | 0.1183 |

| Intraoperative characteristics | ||||

| Year of surgery, per year increase | 1.00 (0.97–1.03) | 0.986 | 0.97 (0.93–1.01) | 0.0921 |

| Duration of cardiopulmonary bypass, per 30-minute increase | 1.07 (1.03–1.12) | 0.0008 | 1.02 (0.96–1.09) | 0.5491 |

| Duration of aortic cross clamp, per 30-minute increase | 0.96 (0.90–1.02) | 0.1694 | 0.93 (0.85–1.01) | 0.0686 |

| Intraoperative insertion of intra-aortic balloon pump | 1.38 (1.13–1.70) | 0.002 | 0.98 (0.77–1.24) | 0.8409 |

| Intraoperative medications | ||||

| Aminocaproic acid | 0.68 (0.60–0.77) | < 0.0001 | 1.15 (0.86–1.54) | 0.3535 |

| Aprotinin | 1.64 (1.43–1.88) | < 0.0001 | 1.26 (0.92–1.71) | 0.145 |

| Epinephrine | 1.86 (1.65–2.10) | < 0.0001 | 1.36 (1.18–1.57) | <0.0001 |

| Norepinephrine | 1.38 (1.10–1.74) | 0.005 | 1.01 (0.79–1.29) | 0.9287 |

| Vasopressin | 1.76 (1.44–2.15) | < 0.0001 | 1.32 (1.05–1.66) | 0.0171 |

| Nitroprusside | 1.13 (1.01–1.28) | 0.038 | 1.05 (0.93–1.20) | 0.4272 |

| Nitroglycerin | 1.04 (0.91–1.19) | 0.599 | 1.00 (0.87–1.16) | 0.9904 |

| Esmolol | 1.10 (0.79–1.54) | 0.560 | 1.29 (0.92–1.82) | 0.136 |

| Metoprolol | 0.83 (0.73–0.94) | 0.003 | 0.88 (0.77–1.01) | 0.0673 |

| Perioperative blood product use within 2 days | ||||

| Red blood cells | 2.10 (1.79–2.46) | < 0.0001 | 0.97 (0.80–1.18) | 0.7514 |

| Fresh Frozen Plasma | 1.58 (1.40–1.78) | < 0.0001 | 1.09 (0.93–1.28) | 0.284 |

| Platelets | 1.54 (1.37–1.73) | < 0.0001 | 1.00 (0.85–1.18) | 0.9773 |

| Cryoprecipitate | 6.08 (3.93–9.42) | 0.0172 | 1.09 (0.82–1.45) | 0.5382 |

| Postoperative acute kidney injury | ||||

| Immediately Post Surgery | 6.08 (3.30–9.42) | <0.0001 | 2.96 (1.88–4.67) | 0.0006 |

| 18 months (1.51 years) and After | 1.77 (1.53–2.03) | <0.0001 | 1.27 (1.09–1.48) | 0.0021 |

The multivariable Cox regression analysis was based on n = 4,143 due to missing information (n = 66) on preoperative medication use. In addition, given the definition we used for acute kidney injury, which had to occur within 10 days after surgery, 8 patients who died within 10 days before developing acute kidney injury were also excluded from the multivariable analysis.

Sensitivity Analysis

In the present study, our decision to use the lowest 10% of postoperative nadir platelet counts was driven by our objective to characterize patients with the most profound postoperative thrombocytopenia. However, given the inherent bias associated with choosing our binary cut-off for postoperative thrombocytopenia, we also performed a sensitivity analysis with postoperative thrombocytopenia defined as nadir values < 100 × 109/L. Using this definition, 28% (n = 1,192) of the study cohort had postoperative thrombocytopenia. Our results indicated that postoperative thrombocytopenia defined as nadir values < 100 × 109/L remained a significant predictor of AKI (adjusted OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.12–1.57; P = 0.0011) and short-term mortality immediately after surgery (adjusted HR, 3.30; 95% CI, 2.30–4.73; P < 0.0001), which then decreased linearly by 37% every 6 months until 14 months (1.18 years), but not for long-term mortality (P = 0.20).

The significant differences in preoperative platelet counts and preoperative serum creatinine values observed between patients with and without postoperative thrombocytopenia had the potential of creating a spurious association between postoperative thrombocytopenia and AKI. After excluding patients (5.7%; n = 241) with a preoperative platelet count ≤ 74 × 109/L or serum creatinine > 2 mg/dL, we repeated our analysis within a sample of patients with normal preoperative platelet count and preoperative serum creatinine values. The results of the repeated analysis indicated that the association between postoperative thrombocytopenia and AKI (OR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.24–2.05; P = 0.0003), and mortality immediately after surgery (adjusted HR, 5.48; 95% CI, 3.66–8.21; P < 0.0001) remained statistically significant, but not for long-term mortality (P = 0.84). The risk for short-term mortality decreased linearly by 52% every 6 months until 14 months after surgery (1.18 years).

Of the 4,217 subjects studied, 0.31% (n = 13) underwent treatment for postoperative HIT. To determine whether the association between postoperative thrombocytopenia and our study outcomes persisted, we repeated the analyses excluding patients with HIT. The association between postoperative thrombocytopenia and postoperative AKI (adjusted OR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.20–1.98; P = 0.0007), and mortality immediately after surgery (adjusted HR, 5.27; 95% CI, 3.62–7.66; P < 0.0001) remained significant, but not for long-term mortality (P = 0.72). The risk for short-term mortality decreased linearly by 50% every 6 months until 14 months (1.18 years).

DISCUSSION

We found a significant association between postoperative nadir platelet counts and postoperative AKI. Importantly, the magnitude of the decreased platelet count correlated significantly with the severity of kidney injury, as well as short-term mortality.

Platelet activation is a key player in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases including thrombotic events such as stroke and myocardial infarction, which can be mitigated by antiplatelet therapies.28,29 Nevertheless, in cardiac surgery, the primary concern related to platelet derangement continues to be focused on bleeding and not thrombosis. Previously, we reported a reduction in both stroke and myocardial infarction with use of aspirin early after CABG surgery.30 Moreover, aspirin therapy was associated with a substantive reduction in AKI.30

During and after CPB, complex pathophysiologic processes in both humoral and cellular processes occur that involve coagulation factors, platelets, fibrinogen, vascular endothelium, and leukocytes, which may promote a shift in risks from bleeding toward microthrombosis.31–33 Available standard laboratory testing for platelet function and potential clinical detection of hemostatic derangements are relatively insensitive for monitoring platelet function in most postoperative settings. Further, “in vitro” laboratory testing may not accurately mimic the complex “in-vivo” hemostatic milieu with vascular and flow interactions. In certain perioperative conditions, a transition zone between bleeding-related and thrombosis-promoting coagulopathy is likely present; while in other settings, bleeding and microthrombosis can occur concurrently, as observed in disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Platelets and Acute Kidney Injury

Current perioperative views on thromboembolism and its definition generally apply to “macroembolism” such as pulmonary embolism and deep venous thrombosis. In cardiac surgery with CPB, the clinical importance of “microthrombosis” remains largely unappreciated, although such pathophysiologic construct for ischemic injury is present, driven primarily by contact activation during and after CPB that can lead to formation of circulating microaggregates (adhesions among white blood cells, activated platelets, and endothelial cells). Along with persistent thrombin generation, microaggregates may produce ongoing microvascular plugging that manifests clinically as AKI, stroke, myocardial infarction, and gastrointestinal complications.29,34,35 Several cellular and extracellular signaling processes involving adhesion molecules may be involved in such ischemic injuries. Among these, the glycoprotein P- selectin is expressed in α–granules of resting platelets, and is extruded to the surface when platelets become activated.36–39 Moreover, it is similarly expressed on activated leukocytes and on endothelial cells, facilitating microaggregate formation.34,40

Thrombocytopenia has often been cited as an indicator of critical illness severity,41 and its association with HIT has been well described in the literature as immune-mediated.42,43 The incidence of “clinical” HIT in our study was very low with only 13 patients (0.31%) receiving treatment for thrombosis-related complications. After excluding these patients from analysis, our findings were unaltered.

The mechanism of postoperative AKI has not yet been characterized, particularly in the context of platelet and leukocyte interactions. While we have reported a novel association between thrombocytopenia and postoperative AKI, we acknowledge that the causality remains uncertain. On the other hand, this recent finding, along with our previous report that end-organ complications are significantly reduced with aspirin therapy early after CABG surgery, could suggest a potential role for platelet-associated injury.30 Whether preoperative antiplatelet therapy can reduce renal and other end-organ injury is an important question to address. In patients with known renal dysfunction (creatinine > 1.5 mg/dL), and who have urgent/emergent CABG surgery, Gerrah et al44 reported that continuing preoperative aspirin until the day of surgery was associated with lower serum creatinine and higher creatinine clearance on postoperative days 1 and 2, compared to patients who had aspirin withheld at least one week before surgery. Similarly, Cao et al45 recently reported that preoperative use of aspirin was associated with a 62% and a 56% reduction in odds of postoperative renal failure and dialysis, respectively. Mangano et al30 noted a 34% reduction in combined cerebral and renal outcomes. In our current study, use of preoperative aspirin was also associated with a 22% reduction in postoperative AKI. In contrast, a recent publication on aspirin therapy in noncardiac surgery patients concluded that administration of aspirin preoperatively and early postoperatively had no significant effect on the rate of a composite of death or nonfatal myocardial infarction, but increased the risk for major bleeding.46 However, comparing this finding in noncardiac surgery to cardiac surgery with CPB is problematic given the marked differences in hemostatic derangement, inflammatory response, and ischemia-reperfusion injury that occur.

Thrombocytopenia and Survival After Surgery

A limited number of studies have investigated the association between postoperative decreases in platelet counts and mortality after cardiac surgery. Williamson et al,17 as well as other investigators, found that, in medical and non-cardiac surgery patients, thrombocytopenia as a time-dependent covariate was independently associated with mortality. Similarly, Glance et al47 recently reported that both preoperative thrombocytopenia and thrombocytosis were associated with reduced survival after surgery. According to our findings, postoperative thrombocytopenia was associated with short-term mortality, but the risk decreased linearly over the first 14 months (1.18 years) following surgery, but not after. Our study cannot establish a causal relationship between postoperative thrombocytopenia and mortality. However, our findings indicate that the effect of thrombocytopenia on end-organ injury such as AKI manifests early after cardiac surgery, and patients who survive the initial postoperative insult will have a better chance for long-term survival. However, some patients succumb to the consequences of the progression of the acute end-organ injury to chronic end-organ dysfunction. In support of the latter, our findings indicated that postoperative AKI was associated with an increased risk for early mortality, which then decreased linearly but remained constantly elevated in the long term, suggesting that prolonged and incomplete recovery after AKI is a potentially significant contributor to the long-term risk for mortality, and further, that postoperative AKI is likely a surrogate for end-organ injuries.48

Limitations

Due to its retrospective design, our study has several limitations. First, information on some important clinical risk factors of postoperative AKI and mortality were not prospectively collected. In our study, electronic medical records and physician documentation were used as sources for additional data on the clinical risk factors, medication use and laboratory data. Thus, the effect of some risk factors, medication use, and laboratory data may have been biased. Nevertheless, their predictive values were similar to those reported in current guidelines.49

Second, this study was performed in a single tertiary center, which may limit the generalizability of our observations to other centers. However, the frequency of patients with postoperative thrombocytopenia,50 AKI,3 and mortality51 observed in our study were similar to those reported from recent large-scale studies.

Third, similarly to previous studies,52,53 our study showed that a lower preoperative hemoglobin concentration was an independent predictor of postoperative AKI and mortality. Indeed, the kidneys, especially in patients with a history of preexisting dysfunction, are more sensitive than other organs to the effects of lower hemoglobin concentrations, and thus, they act as a particularly sensitive and early indicator of ischemic injury,52 which could indicate that the association between postoperative thrombocytopenia and AKI may be influenced by a subset of patients who present for cardiac surgery at a higher risk for developing AKI because of their preexisting anemia. Nevertheless, in our study, the interaction between preoperative hemoglobin concentration and postoperative nadir platelet counts was not significant (P = 0.507), indicating that a lower preoperative hemoglobin concentration did not influence the independent association between postoperative thrombocytopenia and AKI. Factors identified that could have also influenced the course of postoperative platelet counts in our study include postoperative bleeding, systemic inflammatory response related to capillary leak, and compensatory fluid resuscitation. However, given the retrospective nature of our study, we were not able to investigate the influence of these factors on postoperative platelet counts.

Fourth, protocols were not used to guide transfusions or anticoagulation therapies perioperatively. Also, testing for HIT was left to the discretion of the intensive care unit team.43,54,55 While anti platelet factor 4 antibodies are common after CPB, ~3% of patients develop true HIT based on thrombotic sequel or serotonin release assay.56 As noted by Selleng et al,57 early-onset and persisting thrombocytopenia in cardiac surgery patients is seldom caused by HIT. The temporal pattern of HIT, an immune-mediated thrombocytopenia, generally begins 5–10 days after heparin exposure.58

Finally, due to the nature of this study, assumptions about the cause of postoperative thrombocytopenia cannot be made. However, in critically ill patients, a similar association between thrombocytopenia and outcome has been observed, and the drop in platelet count has been attributed to increased destruction, hemodilution, sequestration, or decreased production.17,18 We have previously shown a significant association between leukocyte and platelet activation and ischemic complications after cardiac surgery,34 indicating the relevance of platelet activation and the resultant platelet consumption as a possible cause of the observed thrombocytopenia. But, as we did not measure markers of inflammation and microthrombosis in this current study, future studies that are prospective in design and of sufficient size are needed to define the context of platelet activation, thrombocytopenia, and inflammation-related ischemic complications in CABG surgery.

In summary, our findings suggest an independent association between postoperative nadir platelet counts and AKI and short-term mortality following CABG surgery, suggesting platelet-related ischemic complications.

Supplementary Material

Final Box Summary Statement.

What we already know about this topic

Postoperative acute kidney injury (AKI) after cardiac surgery remains a common and potentially serious postoperative complication.

Platelets play important roles in acute myocardial infarction and stroke however the potential role of platelets in postoperative AKI and mortality after cardiac surgery is largely unexplored.

What this article tells us that is new

The authors performed a retrospective observational study of the association between postoperative nadir platelet counts, AKI and mortality in CABG surgery.

The authors found a significant independent association between postoperative nadir platelet counts, AKI and mortality after CABG surgery.

The work suggests potential platelet related ischemic events during CABG surgery warrant further investigation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Betsy W. Hale, B.Sc., (Data Analyst, Department of Anesthesiology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina) for help with data retrieval and database building. They also thank Igor Akushevich, Ph.D., (Senior Research Fellow, Population Research Institute at the Social Science Research Institute, and Department of Anesthesiology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina) and Yuliya V. Lokhnygina, Ph.D. (Assistant Professor of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Department of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina), for their help with statistical analysis. Finally, we thank Kathy Gage, B.Sc. (Research Development Associate, Department of Anesthesiology, Duke University Medical Center) for her editorial contributions to the manuscript.

We would like to thank the Clinical Anesthesiology Research Endeavors (CARE) Group (members are listed in the Appendix) for facilitating the present study.

Support was provided solely from institutional and/or departmental sources. The authors declare the following financial relationships:

Jörn A. Karhausen: American Heart Association grant (15SDG25080046)

Joseph P. Mathew: National Institutes of Health (HL096978, HL108280, HL109971)

Sources of financial support: none

Appendix: Members of the CARE Group

Department of Anesthesiology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA:

Solomon Aronson, MD; Brandi A. Bottiger, MD; Brian J. Colin, MD; Sean M. Daley, MD; J. Mauricio del Rio, MD; Manuel L. Fontes, MD; Katherine P. Grichnik, MD; Nicole R. Guinn, MD; Jörn A. Karhausen, MD; Miklos D. Kertai, MD; F. Willem Lombard, MD; Michael W. Manning, MD; Joseph P. Mathew, MD; Grace C. McCarthy, MD; Mark F. Newman, MD; Alina Nicoara, MD; Mihai V. Podgoreanu, MD; Mark Stafford-Smith, MD; Madhav Swaminathan, MD; and Ian J. Welsby, MD.

Department of Anesthesiology Clinical Research Services, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA:

Narai Balajonda, MD; Tiffany Bisanar, RN; Bonita L. Funk, RN; Roger L. Hall, AAS; Kathleen Lane, RN, BSN; Yi-Ju Li, PhD; Greg Pecora, BA; Barbara Phillips-Bute, PhD; Prometheus T. Solon, MD; Yanne Toulgoat-Dubois, BA; Peter Waweru, CCRP; and William D. White, MPH.

Perfusion Services, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA:

Kevin Collins, BS, CCP; Ian Shearer, BS, CCP; Greg Smigla, BS, CCP.

Division of Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery, Department of Surgery, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA:

Mark F. Berry, MD; Thomas A. D’Amico, MD; Mani A. Daneshmand, MD; R. Duane Davis, MD; Jeffrey G. Gaca, MD; Donald D. Glower, MD; R. David Harpole, MD; Matthew G. Hartwig, MD; G. Chad Hughes, MD; Robert D.B. Jaquiss, MD; Shu S. Lin, MD; Andrew J. Lodge, MD; Carmelo A. Milano, MD; Charles E. Murphy, MD; Mark W. Onaitis, MD; Jacob N. Schroeder, MD; Peter K. Smith, MD; and Betty C. Tong, MD.

Footnotes

Department to which the work is attributed: Department of Anesthesiology, Duke University Medical Center

References

- 1.Mangano CM, Diamondstone LS, Ramsay JG, Aggarwal A, Herskowitz A, Mangano DT. Renal dysfunction after myocardial revascularization: risk factors, adverse outcomes, and hospital resource utilization. The Multicenter Study of Perioperative Ischemia Research Group. Annals of internal medicine. 1998;128:194–203. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-3-199802010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronson S, Fontes ML, Miao Y, Mangano DT. Risk index for perioperative renal dysfunction/failure: critical dependence on pulse pressure hypertension. Circulation. 2007;115:733–42. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.623538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luo X, Jiang L, Du B, Wen Y, Wang M, Xi X. A comparison of different diagnostic criteria of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients. Critical care. 2014;18:R144. doi: 10.1186/cc13977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loutzenhiser R, Griffin K, Williamson G, Bidani A. Renal autoregulation: new perspectives regarding the protective and regulatory roles of the underlying mechanisms. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R1153–67. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00402.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fontes ML, Aronson S, Mathew JP, Miao Y, Drenger B, Barash PG, Mangano DT. Pulse pressure and risk of adverse outcome in coronary bypass surgery. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2008;107:1122–9. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31816ba404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellomo R, Auriemma S, Fabbri A, D’Onofrio A, Katz N, McCullough PA, Ricci Z, Shaw A, Ronco C. The pathophysiology of cardiac surgery-associated acute kidney injury (CSA-AKI) Int J Artif Organs. 2008;31:166–78. doi: 10.1177/039139880803100210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lema G, Meneses G, Urzua J, Jalil R, Canessa R, Moran S, Irarrazaval MJ, Zalaquett R, Orellana P. Effects of extracorporeal circulation on renal function in coronary surgical patients. Anesthesia and analgesia. 1995;81:446–51. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199509000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersson LG, Bratteby LE, Ekroth R, Hallhagen S, Joachimsson PO, van der Linden J, Wesslen O. Renal function during cardiopulmonary bypass: influence of pump flow and systemic blood pressure. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1994;8:597–602. doi: 10.1016/1010-7940(94)90043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Metnitz PG, Krenn CG, Steltzer H, Lang T, Ploder J, Lenz K, Le Gall JR, Druml W. Effect of acute renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy on outcome in critically ill patients. Critical care medicine. 2002;30:2051–8. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200209000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rewa O, Bagshaw SM. Acute kidney injury-epidemiology, outcomes and economics. Nature reviews Nephrology. 2014;10:193–207. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2013.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ranucci M. Hemostatic and thrombotic issues in cardiac surgery. Seminars in thrombosis and hemostasis. 2015;41:84–90. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1398383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devarajan P. Update on mechanisms of ischemic acute kidney injury. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. 2006;17:1503–20. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Z, Yang F, Dunn S, Gross AK, Smyth SS. Platelets as immune mediators: their role in host defense responses and sepsis. Thrombosis research. 2011;127:184–8. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kornerup KN, Salmon GP, Pitchford SC, Liu WL, Page CP. Circulating platelet-neutrophil complexes are important for subsequent neutrophil activation and migration. Journal of applied physiology. 2010;109:758–67. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01086.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lapchak PH, Kannan L, Ioannou A, Rani P, Karian P, Dalle Lucca JJ, Tsokos GC. Platelets orchestrate remote tissue damage after mesenteric ischemia-reperfusion. American journal of physiology Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2012;302:G888–97. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00499.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singbartl K, Forlow SB, Ley K. Platelet, but not endothelial, P-selectin is critical for neutrophil-mediated acute postischemic renal failure. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2001;15:2337–44. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0199com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williamson DR, Albert M, Heels-Ansdell D, Arnold DM, Lauzier F, Zarychanski R, Crowther M, Warkentin TE, Dodek P, Cade J, Lesur O, Lim W, Fowler R, Lamontagne F, Langevin S, Freitag A, Muscedere J, Friedrich JO, Geerts W, Burry L, Alhashemi J, Cook D. Thrombocytopenia in critically ill patients receiving thromboprophylaxis: frequency, risk factors, and outcomes. Chest. 2013;144:1207–15. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shehata N, Fontes ML. Thrombocytopenia in the critically ill. Canadian journal of anaesthesia = Journal canadien d’anesthesie. 2013;60:621–4. doi: 10.1007/s12630-013-9944-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nashef SA, Roques F, Michel P, Gauducheau E, Lemeshow S, Salamon R. European system for cardiac operative risk evaluation (EuroSCORE) European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery: official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 1999;16:9–13. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(99)00134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sickeler R, Phillips-Bute B, Kertai MD, Schroder J, Mathew JP, Swaminathan M, Stafford-Smith M. The risk of acute kidney injury with co-occurrence of anemia and hypotension during cardiopulmonary bypass relative to anemia alone. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2014;97:865–71. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.09.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Inter Suppl. 2012;2:1–138. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lobato RL, White WD, Mathew JP, Newman MF, Smith PK, McCants CB, Alexander JH, Podgoreanu MV. Thrombomodulin gene variants are associated with increased mortality after coronary artery bypass surgery in replicated analyses. Circulation. 2011;124:S143–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.008334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143:29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kertai MD, Palanca BJ, Pal N, Burnside BA, Zhang L, Sadiq F, Finkel KJ, Avidan MS. Bispectral index monitoring, duration of bispectral index below 45, patient risk factors, and intermediate-term mortality after noncardiac surgery in the B-Unaware Trial. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:545–56. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31820c2b57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Babyak MA. What you see may not be what you get: a brief, nontechnical introduction to overfitting in regression-type models. Psychosomatic medicine. 2004;66:411–21. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000127692.23278.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. Modelling Survival Data: Extended the Cox model. 1. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stasi R. How to approach thrombocytopenia. Hematology/the Education Program of the American Society of Hematology American Society of Hematology. Education Program. 2012;2012:191–7. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2012.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ. 2002;324:71–86. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7329.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rinder CS, Mathew JP, Rinder HM, Greg Howe J, Fontes M, Crouch J, Pfau S, Patel P, Smith BR. Platelet PlA2 polymorphism and platelet activation are associated with increased troponin I release after cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:1118–22. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200211000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mangano DT. Aspirin and mortality from coronary bypass surgery. The New England journal of medicine. 2002;347:1309–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou S, Fang Z, Xiong H, Hu S, Xu B, Chen L, Wang W. Effect of one-stop hybrid coronary revascularization on postoperative renal function and bleeding: A comparison study with off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;147:1511–1516.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doty JR, Wilentz RE, Salazar JD, Hruban RH, Cameron DE. Atheroembolism in cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:1221–6. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04712-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sreeram GM, Grocott HP, White WD, Newman MF, Stafford-Smith M. Transcranial Doppler emboli count predicts rise in creatinine after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Journal of cardiothoracic and vascular anesthesia. 2004;18:548–51. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rinder CS, Fontes M, Mathew JP, Rinder HM, Smith BR. Neutrophil CD11b upregulation during cardiopulmonary bypass is associated with postoperative renal injury. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:899–905. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04490-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mathew JP, Rinder CS, Howe JG, Fontes M, Crouch J, Newman MF, Phillips-Bute B, Smith BR. Platelet PlA2 polymorphism enhances risk of neurocognitive decline after cardiopulmonary bypass. Multicenter Study of Perioperative Ischemia (McSPI) Research Group. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:663–6. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)02335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rabb H, Postler G. Leucocyte adhesion molecules in ischaemic renal injury: kidney specific paradigms? Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1998;25:286–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1998.t01-1-.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rabb H, Ramirez G, Saba SR, Reynolds D, Xu J, Flavell R, Antonia S. Renal ischemic-reperfusion injury in L-selectin-deficient mice. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:F408–13. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.271.2.F408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kelly KJ, Williams WW, Jr, Colvin RB, Bonventre JV. Antibody to intercellular adhesion molecule 1 protects the kidney against ischemic injury. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91:812–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singbartl K, Green SA, Ley K. Blocking P-selectin protects from ischemia/reperfusion-induced acute renal failure. Faseb j. 2000;14:48–54. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Linas SL, Whittenburg D, Parsons PE, Repine JE. Ischemia increases neutrophil retention and worsens acute renal failure: role of oxygen metabolites and ICAM 1. Kidney international. 1995;48:1584–91. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strauss R, Wehler M, Mehler K, Kreutzer D, Koebnick C, Hahn EG. Thrombocytopenia in patients in the medical intensive care unit: bleeding prevalence, transfusion requirements, and outcome. Critical care medicine. 2002;30:1765–71. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200208000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shehata N, Fontes ML. Thrombocytopenia in the critically ill. Can J Anaesth. 2013;60:621–4. doi: 10.1007/s12630-013-9944-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kerendi F, Thourani VH, Puskas JD, Kilgo PD, Osgood M, Guyton RA, Lattouf OM. Impact of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia on postoperative outcomes after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:1548–53. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.05.080. discussion 1554–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gerrah R, Ehrlich S, Tshori S, Sahar G. Beneficial effect of aspirin on renal function in patients with renal insufficiency postcardiac surgery. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2004;45:545–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cao L, Young N, Liu H, Silvestry S, Sun W, Zhao N, Diehl J, Sun J. Preoperative aspirin use and outcomes in cardiac surgery patients. Annals of surgery. 2012;255:399–404. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318234313b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Devereaux PJ, Mrkobrada M, Sessler DI, Leslie K, Alonso-Coello P, Kurz A, Villar JC, Sigamani A, Biccard BM, Meyhoff CS, Parlow JL, Guyatt G, Robinson A, Garg AX, Rodseth RN, Botto F, Lurati Buse G, Xavier D, Chan MT, Tiboni M, Cook D, Kumar PA, Forget P, Malaga G, Fleischmann E, Amir M, Eikelboom J, Mizera R, Torres D, Wang CY, VanHelder T, Paniagua P, Berwanger O, Srinathan S, Graham M, Pasin L, Le Manach Y, Gao P, Pogue J, Whitlock R, Lamy A, Kearon C, Baigent C, Chow C, Pettit S, Chrolavicius S, Yusuf S, Investigators P Aspirin in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1494–503. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Glance LG, Blumberg N, Eaton MP, Lustik SJ, Osler TM, Wissler R, Zollo R, Karcz M, Feng C, Dick AW. Preoperative thrombocytopenia and postoperative outcomes after noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2014;120:62–75. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182a4441f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown JR, Kramer RS, Coca SG, Parikh CR. Duration of acute kidney injury impacts long-term survival after cardiac surgery. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2010;90:1142–8. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.04.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hillis LD, Smith PK, Anderson JL, Bittl JA, Bridges CR, Byrne JG, Cigarroa JE, Disesa VJ, Hiratzka LF, Hutter AM, Jr, Jessen ME, Keeley EC, Lahey SJ, Lange RA, London MJ, Mack MJ, Patel MR, Puskas JD, Sabik JF, Selnes O, Shahian DM, Trost JC, Winniford MD. 2011 ACCF/AHA Guideline for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines Developed in collaboration with the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2011;58:e123–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Selleng S, Malowsky B, Strobel U, Wessel A, Ittermann T, Wollert HG, Warkentin TE, Greinacher A. Early-onset and persisting thrombocytopenia in post-cardiac surgery patients is rarely due to heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, even when antibody tests are positive. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis: JTH. 2010;8:30–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shahian DM, O’Brien SM, Sheng S, Grover FL, Mayer JE, Jacobs JP, Weiss JM, Delong ER, Peterson ED, Weintraub WS, Grau-Sepulveda MV, Klein LW, Shaw RE, Garratt KN, Moussa ID, Shewan CM, Dangas GD, Edwards FH. Predictors of long-term survival after coronary artery bypass grafting surgery: results from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database (the ASCERT study) Circulation. 2012;125:1491–500. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.066902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kulier A, Levin J, Moser R, Rumpold-Seitlinger G, Tudor IC, Snyder-Ramos SA, Moehnle P, Mangano DT. Impact of preoperative anemia on outcome in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Circulation. 2007;116:471–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.653501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Straten AH, Hamad MA, van Zundert AJ, Martens EJ, Schonberger JP, de Wolf AM. Preoperative hemoglobin level as a predictor of survival after coronary artery bypass grafting: a comparison with the matched general population. Circulation. 2009;120:118–25. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.854216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Warkentin TE, Sheppard JA, Horsewood P, Simpson PJ, Moore JC, Kelton JG. Impact of the patient population on the risk for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2000;96:1703–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zwicker JI, Uhl L, Huang WY, Shaz BH, Bauer KA. Thrombosis and ELISA optical density values in hospitalized patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:2133–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.01039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Martel N, Lee J, Wells PS. Risk for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia with unfractionated and low-molecular-weight heparin thromboprophylaxis: a meta-analysis. Blood. 2005;106:2710–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Selleng S, Malowsky B, Strobel U, Wessel A, Ittermann T, Wollert HG, Warkentin TE, Greinacher A. Early-onset and persisting thrombocytopenia in post-cardiac surgery patients is rarely due to heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, even when antibody tests are positive. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:30–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hui P, Cook DJ, Lim W, Fraser GA, Arnold DM. The frequency and clinical significance of thrombocytopenia complicating critical illness: a systematic review. Chest. 2011;139:271–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.