Abstract

Esophageal melanosis which is characterized by melanocytic proliferation in the squamous epithelium of the esophagus and melanin accumulatin of esophageal mucosa (EM) is a rare disease of the digestive system. Although esophageal melanosis is considered to be a benign disease, its etiology is not cleared and has been reported to be the precursor lesion of esophageal primary melanomas. In this report, we aimed to note esophageal melanosis in a 55-year-old female case who applied to our clinic with difficulty in swallowing, burning behind the breastbone in the stomach, heartburn, indigestion, and pain in the upper abdomen after endoscopic and pathologic evaluation. Complaints dropped with anti-acid therapy and case was followed by intermittent endoscopic procedures because of precursor melanocytic lesions.

Keywords: Esophageal melanosis, Reflux esophagitis, Esophageal malignant neoplasms

Introduction

Esophageal melanosis was described for the first time in 1963 by De la Pava and its prevelance was reported to be 4% in autopsy series [1]. Esophageal melanosis which is characterized by melanocytic proliferation in the squamous epithelium of the esophagus and melanin accumulatin of esophageal mucosa (EM) is a rare a disease of the digestive system. Normal EM does not contain melanocytes. However, aberrant melanocyte migration during embryogenesis or reflux esophagitis chronic inflammatory reasons differentiation of stem cells in the basal layer of melanocytes occur are thought to result [2, 3]. While generally considered to be benign, primary esophageal melanomas and the precursors can be found together with esophageal malignancies reported in several publications [1-3]. Typically, these lesions are detected by screening endoscopy and observed in 0.7-2.1% of the upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Autopsy series have been reported more frequently [2]. In this case report, a case of esophageal melanosis was evaluated in the literature.

Case Report

A 55-year-old female patient, with brackish water in the mouth intermittently for about 3 years, difficulty in swallowing, burning behind the breastbone, heartburn, heartburn, indigestion, and pain in the upper abdomen was admitted to our general surgery clinic. In 2011, the patient had a history of diagnosis of papillary thyroid carcinoma treated with total thyroidectomy and radioactive iodine and 100 μg/day of levothyroxine. There were no alcohol and smoking habits. Eating habits of animal foods such as meat and dairy products were weighted. The patient’s physical examination was unremarkable. Rh blood group B was (+). The patient’s biochemical values were normal. A chest radiograph was normal. Abdominal ultrasonography (US) was unremarkable.

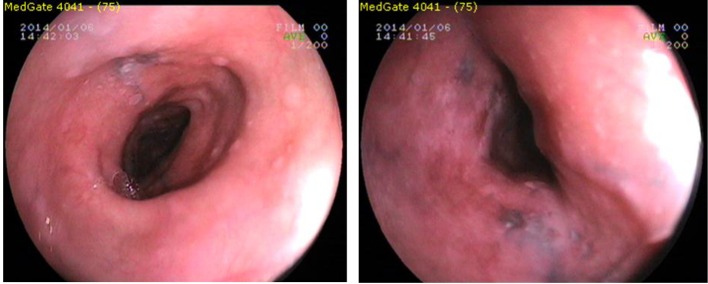

Using Fujinon EG-250WR5 endoscope (Fujinon Optical, Tokyo, Japan) with upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in the mid-EM, the front incisor teeth from 20 cm to the starting 30 cm, which continued until dark (brown, black) color, linear, punctuate, etc. in various forms, ranging in diameter from 2 to 10 mm, flat hyperpigmentation foci were seen. Los Angeles RO phase B was detected in the distal esophagus.

The lower esophageal sphincter (LES) has been passed in 42 cm. The stomach contained bile and gastric juice and alkaline reflux gastritis was observed (Fig. 1). Gastric and duodenal mucosal pigmentation were not detected. LES relaxation was seen in retroflexion. Forceps biopsy of the esophagus was seen in the hyperpigmented areas, distal esophagus, and stomach, multiple biopsies were taken from the antrum and corpus was sent for histopathologic examination. Helicobacter pylori (HP) urease test was two positive (++) respectively.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic view of esophageal melanosis.

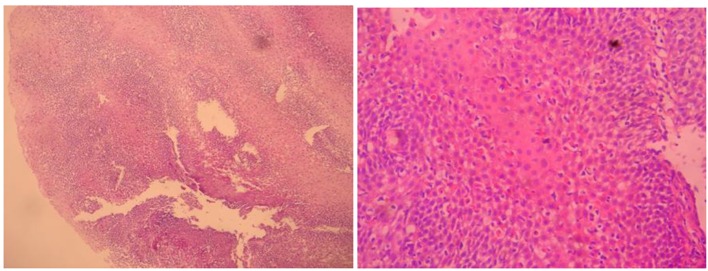

Histopathological examinations with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) stained sections of squamous character acanthosis and intercellular edema showing the covering epithelium located under the lamina propria of the support tissues dense lymphocytic infiltration, as well as numerous dense melanin laden histiocytes were detected. Melanocytes were viewed from place to place in the basal layer of the esophagus. In addition, chronic esophagitis compatible with Roand HP (+) chronic pangastritis was revealed. Esophageal melanosis, reflux esophagitis, and chronic pangastritis were diagnosed histopathologically (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Esophageal mucosal melanocytes, melanin laden histiocytes.

Physical examination was performed again to esophageal melanosis diagnosed case. Hyperpigmentation was not detected on skin, eyes, mouth, throat, genital and anal mucosa. For HP eradication and anti-reflection therapy, the 14-day amoxicillin, clarithromycin, lansoprazole triple therapy with a combination comprising 250 mg of ursodeoxycholic acid/night was given at a single dose. Diet therapy was given for reflux esophagitis. Symptomatic improvement was achieved. Maintenance therapy for 6 months to the patient in the proton pump inhibitor (pantoprazole 40 mg/day) was given.

For pre-malign esophageal melanocytic lesions, endoscopic surveillance was planned. Repeat endoscopy was performed after 1 year. Control endoscopy showed that esophageal EM lesions persisted in the same size and shape. Pigmentation was not seen in gastric and duodenal mucosa. Endoscopy showed that Los Angeles stage RO, esophageal (LES) relaxation, and still have alkaline reflux gastritis. By endoscopy of the esophagus seen in the area of hyperpigmentation, multiple biopsies from the distal esophagus and gastric antrum and corpus were taken. Histopathological examination showed esophageal melanosis, reflux esophagitis consistent with chronic esophagitis and HP (-) revealed mild chronic pangastritis. The patient recommended to continue to follow, still anti-reflux therapy, ursodeoxycholic acid, and dietary practices have been asked to continue. Patient follow-up endoscopy done once a year is planned.

Discussion

Esophageal melanosis, non-atypical melanocytic proliferation of cells in the basal mucous layer and mucous membranes of esophagus, characterized by the accumulation of melanin is a benign pathology.

Esophageal melanosis was described for the first time in 1963 by De la Pava and its prevelance was reported to be 4% in autopsy series [1].

Esophageal melanosis has been reported 0.1% in Japan, and 2.1% in India with endoscopic screening [4, 5]. Esophageal melanosis is found 0.07-2.1% of overall consecutive gastrointestinal endoscopy [2].

In autopsy, esophageal melanosis has been identified 4% in the US and 7.7% in Japan [1, 5]. In Japan, melenosis surgery esophageal carcinoma specimens were reported 27% EM detected [6]. Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus containing 25-30% of the surgical specimen was found in the esophageal melanosis [2, 3].

There are two opinions regarding the formation of esophageal melanosis. In embryogenic life, abnormal migration of melanocytes in EM is thought. According to another opinion, esophagus multipotential stem cells in the basal epithelial layer are thought to occur keratinocytic differentiation with the development of hyperplasia such as reflux, chronic effect being exposed to inappropriate eating [2, 6]. It is possible that combination of both conditions is likely to be stronger.

Melanogenesis process in normal skin prevents intracellular lipids, proteins and nucleotides damage by neutralizing reactive oxygen molecules. Likewise melanosis process, upper gastrointestinal antioxidant defense is thought to function as barriers [7].

Tobacco use leads to chronic damage to upper gastrointestinal mucosa. For example, in Western and Asian populations, in approximately 20% of the oral mucosa of smokers, “cigarettes melanose” has been reported to occur [8]. Esophageal melanosis develops in a case using oral opiates in Iran [9].

Upper gastrointestinal chronic epithelial proliferation stimulatory factors such as alcohol use increase melanogenesis. By endoscopic screening in men alcoholics in Japan, esophageal melanosis rate of 7% was observed [10]. Several factors stimulated by proliferating keratinocytes with epithelial proliferation through autocrine and paracrine effects play a role in enhancing melanogenesis [11].

Chronic alcohol use, cigarette smoking, diet and hereditary factors such as life style have contributed to the development of neoplasms, and this factor may be associated with development as melanosis [6, 10]. Likely, smoking, GERD, race, and type of citrus fruit are effective on high-calorie eating habits reported in several studies that play a role in the formation of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [12].

Also, some studies that mainly meat diet increases the risk of esophageal carcinoma have been reported [13]. In this case, there was no alcohol and tabocco history. However, case with a diet rich in meat and animal food had the habit. The effect of this condition is the formation of esophageal melanosis, which needs further research.

Esophageal melanosis is seen as often during the middle and lower endoscopy or at autopsy, macroscopic examination of the esophagus flat, irregularly shaped lesions. Multiple biopsies should be taken from the lesion area. Histopathological examination of the EM dense melanin laden macrophages in the lamina propriaya and melanocytes in the basal layer is observed.

With hematoxylin-eosin staining melanocytes are seen as pigment-loaded dendritic cells. Melanocyts are painted with melanocytic markers such as melanocytes S-100, melan A and HMB-45.

Fontana-Masson staining positive by the method and with periodic acid-Schiff method and Perls is negative. Generally, melanocytes exhibit no nuclear or cellular atypia [14].

Esophageal melanosis is often seen with chronic esophagitis, acanthosis and basal cell hyperplasia is associated with reactive epithelial changes [1-5]. In this case, endoscopic EM revealed focal hyperpigmentation ranging in diameter from 2 to 10 mm. Melanin laden macrophages dense in places with atypical melanocytes with non-chronic esophagitis and acanthosis were found in the mucosa detected in H&E staining in biopsies.

Scientific studies mainly have been reported to occur that chronic effects like bile and gastric fluid gastroesophageal reflux, cause esophageal melanosis [2, 5, 12]. Gastric acid, bile and trypsin reflux depending on the NF-kB, AP-1, IL-8, etc. inflammatory cytokines, leukocytes and oxidative stress mediators, such as pro-inflammatory factors, erosive and non-erosive GERD pathogenesis to be effective is shown [15]. GERD, esophageal cancer, particularly in the formation, has been found to be associated with the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma [16]. The endoscopic examination in this case found has a reflux esophagitis in phase with Los Angeles phase B and chronic esophagitis was found on pathologic examination. Proton pump inhibitors in the treatment of patients with long-term and proper diet were given.

In vitro, the conjugated bile salts have been shown to cause in esophageal epithelial cells a number of events like increased mRNA expression, inflammatory cytokines TNF-alpha, IL-1 beta and CDX1. Also by the action of bile salts in esophageal squamous cell CD95 mediated apoptosis has been shown to have increased sensitivity. Bile acids have been found to be effective, GERD esophagitis, Barrett’s metaplasia and in carcinogenesis development [17, 18]. This case was found in the alkaline reflux pangastritis. Enhancing effect of chronic bile reflux esophagitis shows and probably facilitates the formation of EM. For the treatment of case ursodeoxycholic acid 250 mg/day was used.

In several studies, particularly Cag A (+) HP infection esophageal epithelial cells, to cause DNA strand breaks, has been reported to contribute to the formation of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [19]. Between HP infection and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus, statistically significant correlation was found [20]. HP causes cellular destruction in the EM. These chronic effects can contribute to the formation of EM. In this case, HP infection has also been identified and eradication therapy was applied. Depending on GERD, acid and bile reflux in the esophagus may lead to intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and eventually to esophageal carcinoma. The lower esophageal sphincter laxity increases in the reflux esophagitis [21]. In this case, endoscopic observation showed also hiatal slack.

EM reported was seen in association with Laugier-Hunziker syndrome, Addison’s disease and esophageal with systemic diseases such as melanoma, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma was seen [2, 3, 22, 23]. Ishida et al have found that in their study of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in situ, 3.8% of patients with carcinoma in situ had the melanocytosis pigment around in non-neoplastic squamous epithelium. They also report that melanoctytosis cause of chronic esophagitis may have been reported [24].

Iwanuma et al reported that primary malignant melanomas usually present together with melanocytosis, melanoma in situ or intramural metastasis [25]. Sanchez et al have been reported to be important to separate primary esophagus melanomas from metastatic melanoma with the presence of in situ melanoma, radial growth phase, mixed epithelioid, spindle cell morphology and the presence of esophageal melanosis [26].

In the differential diagnosis of esophageal melanosis, that should be considered, the other pathologies have melanin deposition as malignant melanoma and melanocytic nevi. Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus, accounting for only 0.1-0.2% of malignant esophageal tumors, more mid and lower esophageal endoscopic pigmented or unpigmented is emerging as a polypoid mass [27]. Melanocytic nevus is a rare entity. Lam et al reported a single case [28].

EM is investigated in clinical and endoscopic diagnosis of pigmented lesions with other antracosis, hemosiderosis or accumulation of lipofuscin pigments, should be considered and necessarily should be questioned uptake of exogenous dye or paint. However, differential diagnosis of these entities with the aid of histological and histochemical stains may be made [2, 3]. Again in the diagnosis of esophageal melanosis, other lesions can be useful in the separation magnifying endoscopy [29]. Endoscopic differential diagnosis in mind to keep other underlying entity of ischemic causes (arteriosclerosis, atrial thrombosis, aortic dissection, etc.) and necrosis associated with “black” esophagus which pigmented lesions associated with separation from endoscopic and pathologic is easier [30].

Depending on chronic esophagitis, melanocytosis of the basal epithelial layer may play a role in the development of the primary malignant melanoma [2, 3, 5].

Walter et al have reported that melanoctytosis has emphasized the need to be taken into account in development of esophageal malignancy [31].

Also, Yokoyama et al reported that esophageal melanosis is precursor to esophageal dysplasia, esophageal melanoma and esophageal carcinoma [6]. A patient with 8 years of follow-up with a diagnosis of benign melanocytosis in esophagus was reported. Maroy et al reported the development of malignant melanoma poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma [32]. Unverdi et al reported esophageal melanosis may be the precursor lesion in the esophagus melanomas, suggesting clinical and endoscopic follow-up [33].

Conclusion

Esophageal melanosis is a rare disease of esophagus, is considered to be benign and shows hyperpigmented lesions. Recently, several studies reported esophageal melanosis may be a precursor to malignancy. Opportunities created by the recent technological advances in the medical field with the selected cases with localized disease, for the applicability of local therapy (endoscopic mucosectomy, superficial lesions, such as extraction) do not support the literature. Because of high mortality and morbidity rates of highly radical esophageal surgery may not be recommended for the benign nature of a disease. However, considering the reported cases as a potential cause premalignancy of EM patients is necessary following up in frequent intervals.

References

- 1.De La Pava S, Nigogosyan G, Pickren JW, Cabrera A. Melanosis of the esophagus. Cancer. 1963;16:48–50. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196301)16:1<48::AID-CNCR2820160107>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang F, Deere H. Esophageal melanocytosis morphologic features and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130(4):552–557. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-552-EMMFAR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamazaki K, Ohmori T, Kumagai Y, Makuuchi H, Eyden B. Ultrastructure of oesophageal melanocytosis. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1991;418(6):515–522. doi: 10.1007/BF01606502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohmori T, Makuuchi H, Kumagai Y, Yamazaki K. Esophageal melanosis (in Japanese) ShokakiNaishikyo (Endosc Dig) 1990;2:1158–1159. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma SS, Venkateswaran S, Chacko A, Mathan M. Melanosis of the esophagus. An endoscopic, histochemical, and ultrastructural study. Gastroenterology. 1991;100(1):13–16. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90576-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yokoyama A, Omori T, Yokoyama T, Tanaka Y, Mizukami T, Matsushita S, Higuchi S. et al. Esophageal melanosis, an endoscopic finding associated with squamous cell neoplasms of the upper aerodigestive tract, and inactive aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 in alcoholic Japanese men. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40(7):676–684. doi: 10.1007/s00535-005-1610-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wood JM, Jimbow K, Boissy RE, Slominski A, Plonka PM, Slawinski J, Wortsman J. et al. What's the use of generating melanin? Exp Dermatol. 1999;8(2):153–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.1999.tb00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hedin CA, Axell T. Oral melanin pigmentation in 467 Thai and Malaysian people with special emphasis on smoker's melanosis. J Oral Pathol Med. 1991;20(1):8–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1991.tb00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geramizadeh B, Asadian F, Taghavi A. Esophageal melanocytosis in oral opium consumption. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(1):e7820. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.7820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yokoyama A, Mizukami T, Omori T, Yokoyama T, Hirota T, Matsushita S, Higuchi S. et al. Melanosis and squamous cell neoplasms of the upper aerodigestive tract in Japanese alcoholic men. Cancer Sci. 2006;97(9):905–911. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00260.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon PR, Mansur CP, Gilchrest BA. Regulation of human melanocyte growth, dendricity, and melanization by keratinocyte derived factors. J Invest Dermatol. 1989;92(4):565–572. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12709595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Navarro Silvera SA, Mayne ST, Gammon MD, Vaughan TL, Chow WH, Dubin JA, Dubrow R. et al. Diet and lifestyle factors and risk of subtypes of esophageal and gastric cancers: classification tree analysis. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24(1):50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu HC, Yang X, Xu LP, Zhao LJ, Tao GZ, Zhang C, Qin Q. et al. Meat consumption is associated with esophageal cancer risk in a meat- and cancer-histological-type dependent manner. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59(3):664–673. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2928-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohashi K, Kato Y, Kanno J, Kasuga T. Melanocytes and melanosis of the oesophagus in Japanese subjects - analysis of factors effecting their increase. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1990;417(2):137–143. doi: 10.1007/BF02190531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshida N. [Cytokine expression in GERD] Nihon Rinsho. 2007;65(5):813–821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim JJ. Upper gastrointestinal cancer and reflux disease. J Gastric Cancer. 2013;13(2):79–85. doi: 10.5230/jgc.2013.13.2.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naran S, Abrams P, de Oliveira PQ, Hughes SJ. Bile salts differentially sensitize esophageal squamous cells to CD95 (Fas/Apo-1 receptor) mediated apoptosis. J Surg Res. 2011;171(2):504–509. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McQuaid KR, Laine L, Fennerty MB, Souza R, Spechler SJ. Systematic review: the role of bile acids in the pathogenesis of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and related neoplasia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(2):146–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li WS, Tian DP, Guan XY, Yun H, Wang HT, Xiao Y, Bi C. et al. Esophageal intraepithelial invasion of Helicobacter pylori correlates with atypical hyperplasia. Int J Cancer. 2014;134(11):2626–2632. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rokkas T, Pistiolas D, Sechopoulos P, Robotis I, Margantinis G. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and esophageal neoplasia: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(12):1413–1417. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.08.010. 1417 e1411-1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boeckxstaens GE. The lower oesophageal sphincter. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;17(Suppl 1):13–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2005.00661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamamoto O, Yoshinaga K, Asahi M, Murata I. A Laugier-Hunziker syndrome associated with esophageal melanocytosis. Dermatology. 1999;199(2):162–164. doi: 10.1159/000018227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones BH, Fleischer DE, De Petris G, Heigh RI, Shiff AD. Esophageal melanocytosis in the setting of Addison's disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61(3):485–487. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(04)02845-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishida M, Mochizuki Y, Iwai M, Yoshida K, Kagotani A, Okabe H. Pigmented squamous intraepithelial neoplasia of the esophagus. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6(9):1868–1873. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iwanuma Y, Tomita N, Amano T, Isayama F, Tsurumaru M, Hayashi T, Kajiyama Y. Current status of primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus: clinical features, pathology, management and prognosis. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47(1):21–28. doi: 10.1007/s00535-011-0490-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanchez AA, Wu TT, Prieto VG, Rashid A, Hamilton SR, Wang H. Comparison of primary and metastatic malignant melanoma of the esophagus: clinicopathologic review of 10 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132(10):1623–1629. doi: 10.5858/2008-132-1623-COPAMM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sabanathan S, Eng J, Pradhan GN. Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84(12):1475–1481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lam KY, Law S, Chan GS. Esophageal blue nevus: an isolated endoscopic finding. Head Neck. 2001;23(6):506–509. doi: 10.1002/hed.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mori A, Tanaka M, Terasawa K, Hayashi S, Shimada Y. A magnified endoscopic view of esophageal melanocytosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61(3):479–481. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(04)02638-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geller A, Aguilar H, Burgart L, Gostout CJ. The black esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90(12):2210–2212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walter A, van Rees BP, Heijnen BH, van Lanschot JJ, Offerhaus GJ. Atypical melanocytic proliferation associated with squamous cell carcinoma in situ of the esophagus. Virchows Arch. 2000;437(2):203–207. doi: 10.1007/s004280000220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maroy B, Baylac F. Primary malignant esophageal melanoma arising from localized benign melanocytosis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2013;37(2):e65–67. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Unverdi H, Savas B, Ensari A, Ozden A. [Melanocytosis of the oesophagus: case report] Turk Patoloji Derg. 2012;28(1):87–89. doi: 10.5146/tjpath.2012.011005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]