Abstract

Background

Rice is the only crop that germinates and elongates the coleoptile under complete submergence. It has been shown that alcohol dehydrogenase 1 (ADH1)-deficient mutant of rice with reduced alcohol dehydrogenase activity (rad) and reduced ATP level, is viable with much reduced coleoptile elongation under such condition. To understand the altered transcriptional regulatory mechanism of this mutant, we aimed to establish possible relationships between gene expression and cis-regulatory information content.

Findings

We performed promoter analysis of the publicly available differentially expressed genes in ADH1 mutant. Our results revealed that a crosstalk between a number of key transcription factors (TFs) and different phytohormones altered transcriptional regulation leading to the survival of the mutant. Amongst the key TFs identified, we suggest potential involvement of MYB, bZIP, ARF and ERF as transcriptional activators and WRKY, ABI4 and MYC as transcriptional repressors of coleoptile elongation to maintain metabolite levels for the cell viability. Out of the repressors, WRKY TF is most likely playing a major role in the alteration of the physiological implications associated with the cell survival.

Conclusions

Overall, our analysis provides a possible transcriptional regulatory mechanism underlying the survival of the rad mutant under complete submergence in an energy crisis condition and develops hypotheses for further experimental validation.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12284-016-0124-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Rice, Coleoptile, Submergence, Alcohol dehydrogenase 1 (ADH1), Reduced alcohol dehydrogenase activity (rad), Promoters, Cis-elements, Transcription factors (TFs)

Findings

Transcriptome configuration of the rice alcohol dehydrogenase 1 (ADH1)-deficient mutant

Rice (Oryza sativa L.) has the exceptional ability to germinate and elongate the coleoptile under complete submergence. Germination under such condition mainly depends on carbohydrate metabolism and alcoholic fermentation for ATP synthesis by recycling NAD+ (ap Rees et al. 1987; Greenway and Gibbs 2003; Bailey-Serres and Voesenek 2008). Alcoholic fermentation is catalyzed by two cytoplasmic enzymes, pyruvate decarboxylase and alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) to ferment pyruvate to ethanol (Magneschi and Perata 2009). Rice possesses three ADH genes: ADH1, ADH2 and ADH3 (Xie and Wu 1989 and Terada et al. 2007). However, ADH1 mutant of rice with reduced adh activity (rad mutant) and much reduced ADH1 protein, is shown to be involved in the suppression of coleoptile elongation under submergence, whereas ADH2 mutant does not show any suppression in coleoptile elongation (Terada et al. 2007). Hence, the gene ADH1 is critical for the regeneration of NAD+ to sustain glycolysis during elongation of coleoptile under submergence. Matsumura et al. (1998) and Saika et al. (2006) have reported that there was tremendous reduction in ADH activity in rad mutant. This reduced functionality of ADH1 appears to be linked to impaired ATP production and less recycling of NAD+. Moreover, involvement of ADH1 for sugar metabolism via glycolysis to ethanol fermentation has been recently reported (Takahashi et al. 2014). These evidences clearly indicate that a normal level of ADH1 expression is crucial for coleoptile elongation under submergence.

In the rad mutant, the elongation of the coleoptile is slow due to reduced NAD+ regeneration and ATP to maintain protein synthesis, cell wall synthesis and membrane proliferation. However, to maintain the balance of metabolites, the rad mutant has perhaps evolved control mechanism which may slow down the synthesis of cell building blocks (Hsiao, 1973). Therefore, to elucidate the regulatory mechanism associated with the altered transcriptome of rad mutant of rice during germination under complete submergence, we performed an ab initio analysis of cis-regulatory information content using publicly available microarray data (Takahashi et al. 2011).

Distribution of putative cis-elements among the genes differentially expressed between rad mutant and WT rice

To achieve an overall view on the distribution of putative cis-elements in the promoters of the differentially expressed genes in rad mutant, the motif enrichment analysis was conducted (Additional file 1). The most highly enriched putative cis-elements associated with various TFs in the up/or downregulated genes and their total enrichment scores for each TF class are listed in Tables 1, 2 and 3.

Table 1.

Potential cis-elements identified in the promoters of upregulated genes in rad mutant

| Cis-elements | Motifs | Associated TFs | % (TIC), E-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| AT-hook/PE1-like | GAAAAAAAAA | MYB (PF1) | 71 (15.87), 9e-004 |

| TATTTTTTA | MYB (PF1) | 58 (14.35), 8e-004 | |

| TTTGTTTTT | MYB (PF1) | 52 (13.58), 6e-004 | |

| AAAAAAATG | MYB (PF1) | 51 (13.77), 6e-004 | |

| GT-element-like | GAAAAAAAAA | MYB (GT-1/GT-3b) | 71 (15.87), 9e-004 |

| GTGTGTTT | MYB (GT-1) | 54 (12.50), 7e-004 | |

| GARE-like | TTTGTTTTT | MYB (R1, R2R3) | 52 (13.58), 6e-004 |

| TTTACAAA | MYB (R1, R2R3) | 56 (12.25), 3e-004 | |

| MYB-box-like | AGGTGCACA | MYB (R1, R2R3) | 63 (11.06), 5e-004 |

| TCTCCCAC | MYB (R1, R2R3) | 59 (11.66), 3e-003 | |

| ABRE-like | AGGTGCACA | bZIP (Gr. A) | 63 (11.06), 5e-004 |

| TCCTCGCC | bZIP (Gr. A) | 59 (12.89), 5e-004 | |

| As-1-like | AGCATCAA | bZIP (Gr. D, I, S) | 71 (10.87), 3e-004 |

| AuxRe-like | TCTCCCAC | ARF | 59 (11.66), 3e-003 |

| TTTGTTTTT | ARF | 52 (13.58), 6e-004 | |

| MYC-box-like | CCTACTCC | MYC (bHLH) | 56 (11.01), 2e-004 |

| CACATCTC | MYC (bHLH) | 54 (11.14), 6e-004 | |

| GCC-box-like | CGCCGCCGG | ERF (I, IV, VII, X) | 53 (14.54), 4e-004 |

| GCGGCGGC | ERF (I, IV, VII, X) | 51 (14.24), 1e-004 | |

| W-box-like | GTGACCAAA | WRKY | 61 (10.68) 8e-004 |

| E2F binding site-like | CCCCCGCC | E2F | 59 (12.44), 3e-004 |

| PCF1 and PCF2 binding site-like | TCTCCCAC | PCF1 and PCF2 (bHLH) | 59 (11.66), 3e-003 |

| ABRE-like | CTCCTCCA | ABI4(AP2) | 58 (12.05), 6e-004 |

| Alfin1 binding site-like | GTGTGTTT | Alfin 1 (PHD finger protein) | 54 (12.50), 7e-004 |

* % = percent occurrence among all upregulated genes, TIC total information content of homology, E-value E-value of homology with promoter database entry

Table 2.

Potential cis-elements identified in the promoters of downregulated genes in rad mutant

| Cis-elements | Motifs | Associated TFs | % (TIC), E-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| AT-hook/PE1-like | ATATTTTTT | MYB (PF1) | 72 (14.31), 3e-004 |

| TCCAAAAA | MYB (PF1) | 71 (11.53), 6e-004 | |

| ATTTTTAAA | MYB (PF1) | 58 (13.45), 3e-004 | |

| TTTTTTTCTT | MYB (PF1) | 54 (14.95), 6e-004 | |

| MYB-box-like | TCCAAAAA | MYB (R2R3, MCB1/2) | 71 (11.53), 6e-004 |

| GATTAGTG | MYB (R2R3) | 68 (10.71), 6e-004 | |

| CAACCACA | MYB (R2R3) | 51 (11.98), 3e-004 | |

| CCACCCAGC | MYB (R2R3) | 51 (12.20), 3e-004 | |

| AAAATCCA | MYB (R2R3) | 50 (12.89), 2e-004 | |

| GT-element-like | GATTAGTG | MYB (GT-1/GT-3b) | 68 (10.71), 6e-004 |

| TTTTTTTCTT | MYB (GT-1) | 54 (14.95), 6e-004 | |

| GARE-like | AAAATCCA | MYB (R1, R2R3) | 50 (12.89), 2e-004 |

| Pyrimidine-box-like | TTTTTTTCTT | MYB (R1, R2R3) | 54 (14.95), 6e-004 |

| TCTTTTTT | MYB (R1, R2R3 | 54 (13.57), 3e-004 | |

| As-1/ocs/TGA-like | TCCGTCAC | bZIP (Gr. D, I, S) | 53 (11.81), 2e-004 |

| GAAGATGA | bZIP (Gr. D, I, S) | 54 (12.78), 2e-004 | |

| ABRE-like/G-box-like | CAACCACA | bZIP (Gr A) | 51 (11.98), 3e-004 |

| AuxRe-like | GATTAGTG | ARF | 68 (10.71), 6e-004 |

| Binding site of the HDZIPs-like | GATTAGTG | HDZIPs | 68 (10.71), 6e-004 |

| GCC-box-like | CGGCGGCG | ERF (I, IV, VII, X) | 60 (14.85), 6e-004 |

| AAAAG-element-like | TCTTTTT | DOF1/4/11/22 | 54 (13.57), 3e-004 |

| GAGA element-like | TCTCTCCC | GAGA-binding factor | 53(12.93), 8e-004 |

| TATA-box-like | TTTATTTT | TBP | 66 (13.19), 4e-004 |

| DBP1 binding site-like | ATTATAATA | DBP1 | 56 (12.79), 2e-004 |

* % percent occurrence among all upregulated genes, TIC total information content of homology, E-value E-value of homology with promoter database entry

Table 3.

List of transcription factor genes with total enrichment scores among the upregulated (UR) and downregulated (DR) target genes in the rad mutant

| TF Family | Locus_ID (Annotation)a | Fold increaseb | Total enrichment score of target motifsc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UR | DR | |||

| MYB | Os01g0187900 (Similar to Transcription factor MYBS2) | 2.80 | 587 | 826 |

| ERF | Os04g0547600 (Pathogenesis-related transcriptional factor and ERF domain containing protein) | 6.97 | 104 | 60 |

| Os04g0398000 (Pathogenesis-related transcriptional factor and ERF domain containing protein) | 3.86 | |||

| Os04g0550200 (Pathogenesis-related transcriptional factor and ERF domain containing protein) | 2.81 | |||

| Os01g0797600 (AP2/ERF family protein, ERF-associated EAR-motif-containing repressor, Abiotic stress response, Stress signaling, OsERF3) | 2.62 | |||

| WRKY | Os05g0571200 (Similar to WRKY transcription factor 19) | 14.59 | 61 | -- |

| Os01g0826400 (WRKY transcription facto 24) | 8.82 | |||

| Os01g0584900 (WRKY transcription factor 28-like (WRKY5) (WRKY transcription factor 77) | 5.43 | |||

| Os02g0181300 (Similar to WRKY transcription factor) | 4.60 | |||

| Os06g0649000 (Similar to WRKY transcription factor 28) | 3.84 | |||

| Os03g0758000 (Similar to WRKY transcription protein) | 3.83 | |||

| Os04g0605100 (WRKY transcription factor 68) | 3.11 | |||

| Os01g0246700 (Similar to WRKY transcription factor 1) | 2.58 | |||

| bHLH | Os06g0193400 (Similar to Helix-loop-helix protein homolog) | 2.57 | 59 | -- |

aInformation based on RAP-DB (http://rapdb.dna.affrc.go.jp/); bBased on microarray data of Takahashi et al. (2011); ctotal target motif enrichment score = sum of the % occurrences of all motif species belonging to the same TF family in the upregulated (UR) and downregulated (DR) groups of genes (refer to Tables 1 and 2)

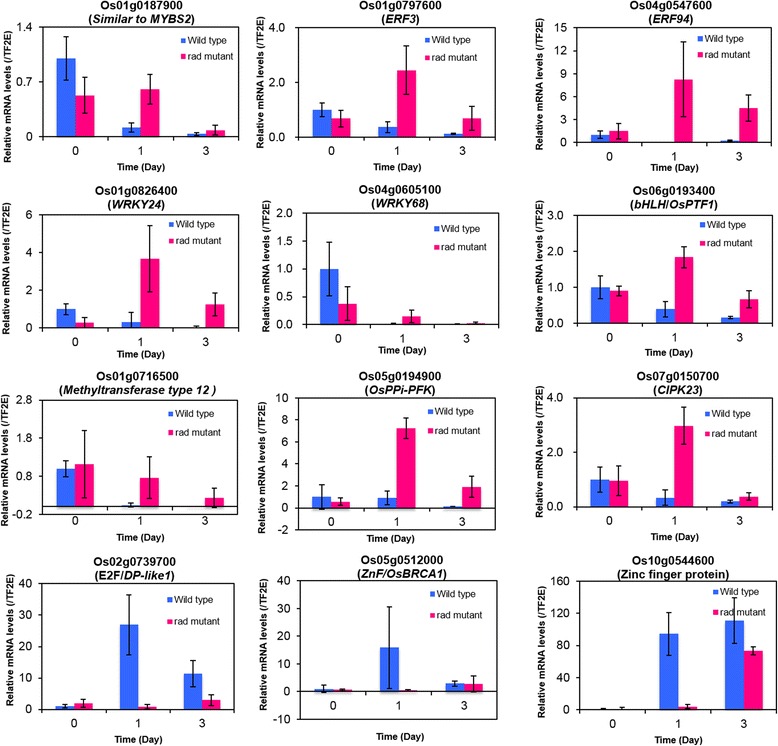

In the current analysis, the promoters of the up/downregulated genes in the rad mutant were significantly enriched with common putative cis-elements which are connected to several TFs such as MYB, bZIP, ERF and ARF. Interestingly, MYB and ERF TF genes are consistently upregulated (Table 3). To confirm their expression level, qRT-PCR analysis was performed for Os01g0187900 (MYBS2), Os01g0797600 (ERF3), and Os04g0547600 (ERF94) at 0, 1 and 3 days after germination under complete submergence for both rad mutant and WT (Additional file 1). MYBS2 and ERF showed high expression in rad mutant at 1 day and both 1 and 3 days, respectively, after germination (Fig. 1). Hence, these TFs appear to be conserved in both rad mutant and wild type and are most likely involved as transcriptional activators (Additional file 2). In contrast, we found significant percentage of putative cis-elements associated with WRKY, ABI4, and MYC (bHLH) and high expression level of TF genes (WRKY and bHLH) only in the rad mutant (Additional file 2; Table 1). The results suggest that these TFs are possibly involved in the suppression of coleoptile elongation to support cell survival. Among them, qRT-PCR analysis performed for Os01g0826400 (WRKY 24), Os04g0605100 (WRKY 68) and Os06g0193400 (bHLH) showed high expression in rad mutant at 1 and 3 days after germination compared to the wild type (Fig. 1). Corresponding with these expression data, we also identified putative w-box-like elements in the promoter regions of some of the key upregulated metabolic genes which might be linked to the reduced coleoptile elongation in rad mutant. Examples of such genes are as follows: i) UDP-glucuronosyl/UDP-glucosyltransferase family protein (Os06g0220500), which plays a major role in cell homeostasis (Vogt and Jones 2000) and potentially contributes to chemical stability and reduced chemical activity of the cell under stress conditions, ii) similar to cytochrome P450 family (Os12g0268000), induced by environmental stresses, which contains binding sites for MYB, MYC, and WRKY in their promoters and is involved in the catabolism of plant hormones (Ayyappan et al. 2015), and iii) methyltransferase type 12 domain containing protein (Os01g0716500), which may control the synthesis of cell building blocks by repressing their transcription. Taken together, our results demonstrate a possible link between WRKY TF and metabolic alteration that supports rad mutant for the cell survival. Moreover, among the glycolytic genes, pyrophosphate-dependent phosphofructo-1-kinase-like protein (PPi-PFK) (Os05g0194900) seems to play a major role in energy conservation by using PPi instead of ATP as an alternative energy source during ATP deficiency (Huang et al. 2008). All these genes, having supportive role in the cell survival, also possess common TF binding sites in their promoter regions (Additional file 3: Figure S1). High expression of methyltransferase type 12 domain containing protein and PPi-PFK performed by qRT-PCR analysis in rad mutant at both 1 and 3 days after germination compared to wild type supports their involvement in cell survival (Fig. 1). We also did qRT-PCR analysis for TF genes (downregulated in the mutant) such as Os02g0739700 (E2F), Os05g0512000 (Zinc finger), and Os10g054460 (Zinc finger protein) at 0, 1 and 3 days after germination under complete submergence for both rad mutant and WT (Additional file 1). The expression level of E2F (related to cell division) in rad mutant was clearly lower than WT at one and three days, and that of Zinc fingers (related to protein binding) was much lower at 1 day (Fig. 1). All together, we can hypothesize that the altered transcriptome in the rad mutant could be due to a group of candidate transcriptional activators and repressors that may play critical roles under such energy crisis conditions. This is supported by the fact that distinctive TFs act as key activators and repressors in response to various abiotic and biotic stress conditions (Nakashima et al. 2012).

Fig. 1.

Gene expression pattern of transcription factor, metabolic and signal transduction genes upregulated and downregulated in LM-isolated coleoptiles of rad mutant after 0, 1 and 3 days after complete submergence. Rice seeds (rad mutant and WT) were germinated under complete submergence for 0, 1 and 3 days after imbibition. Coleoptiles were isolated from rice embryo sections by using LM, and then total RNA was extracted from LM-isolated tissues. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed for selected genes with appropriate primers (Additional file 5: Table S1). Upregulated genes in the rad mutant: Os01g0187900 (Similar to Transcription factor MYBS2), Os01g0797600 (ERF3), Os04g0547600 (ERF94), Os01g0826400 (WRKY 24), Os04g0605100 (WRKY 68), Os06g0193400 (PTF/bHLH), Os01g0716500 (methyltransferase type 12 domain containing protein), Os05g0194900 (PPi-PFK) and Os07g0150700 (CIPK23). Downregulated genes: Os02g0739700 (E2F Family domain containing protein), Os05g0512000 (Zinc finger/OsBRCA1), and Os10g054460 (Zinc finger, RING/FYVE/PHD-type domain containing protein). Transcript level of each gene was normalized to the transcript level of rice TF2E (Os10g0397200) gene (used as a control gene). Each data point represents the means ± SD (n = 3)

To find the association relationship among genes based on expression data and the candidate TF genes, we developed a gene regulatory network using ARACNE (Margolin et al. 2006). The network clearly provides information regarding the extensive interaction between the regulators and the genes upregulated in the rad mutant (Additional file 4: Figure S2).

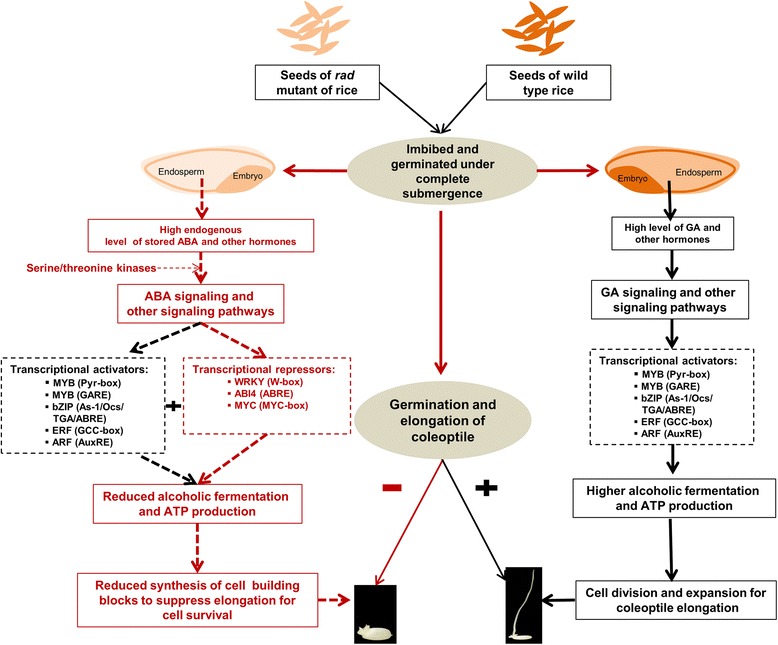

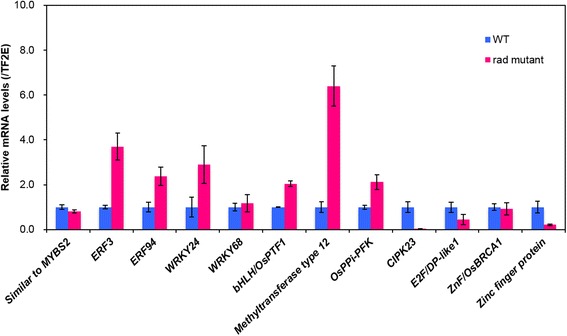

Overall analysis of the transcriptome of the rad mutant of rice

Our results evidently demonstrated that reduced ADH1 activity can affect the regulation of many genes involved in different pathways. A view of how such metabolic changes affected gene expression at the global scale has been established by the patterns of putative cis-element enrichment within the affected component of the transcriptome (Haberer et al. 2004). The hypothetical model in Fig. 2 illustrates the possible association of several classes of TFs acting as activators and/or repressors that determine upregulation and downregulation of genes due to the reduced function of ADH1. Although putative cis-elements associated with MYB TFs were significantly enriched in both rad mutant and WT, pyrimidine-box-like elements were absent among the upregulated genes (Tables 1 and 2). Moreover, the cis-elements associated with R2R3-MYB-type TFs were more abundant among the downregulated genes, which is similar to the WT where coleoptile elongates under complete submergence. Enrichment of ABRE-like motifs associated with ABI4 TF (Table 1) could be correlated to abscisic acid (ABA) -dependent repression of coleoptile elongation with higher endogenous ABA level as well as interaction of WRKY, ABI4 and MYC (bHLH) TFs as repressor of cell division and elongation. This hypothesis can be linked to the involvement of the upregulation of a number of ABA-dependent abiotic stress responsive serine/threonine kinases in rad mutant (Table 4) (Kulik et al. 2011) and higher expression of the serine/threonine protein kinase (CIPK23) (Os07g0150700) confirmed by qRT-PCR at 1 and 3 days after germination under complete submergence compared to wild type (Fig. 1). The high endogenous level of stored ABA (present in rice seeds) (Mapelli et al. 1995) seems to activate the altered transcriptome for the cell survival. Moreover, to confirm the involvement of genes belonging to different TF families, metabolic and signaling pathways, the qRT-PCR analysis performed for the genes at 0, 1 and 3 days after complete submergence (Fig. 1) was further extended to coleoptiles exposed to complete submergence for 7 days in both rad mutant and wild type. The high expression level of most of the genes (upregulated in rad mutant) and low expression of the TF genes (upregulated in rad mutant) clearly supports their crucial role in cell survival (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Hypothetical model showing altered transcriptional regulatory mechanisms leading to reduced coleoptile elongation of rad mutant. The presence of high endogenous level of ABA in the seeds of rad mutant could lead to ABA dependent signaling via serine/threonine kinases. It might lead to the activation of a number of TFs acting as repressors of metabolic genes that slow down the synthesis of cell building blocks for suppression of elongation to maintain metabolites for cell survival. The bigger filled squares with font color in black represent various positive transcriptional modules showing cis-elements and their cognate transcriptional regulators. The bigger filled squares with font color in red represent various transcriptional repressors with cis-elements and their cognate transcriptional regulators. The dash lines represent the hypothesis predicted from the gene expression data of the rad mutant

Table 4.

List of serine/threonine kinase genes upregulated in the rad mutant

| Locus ID (Annotation)a | Description | Function | Fold change (rad/WT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Os07g0150700 | Similar to Serine/threonine kinase | Phosphorylation | 6.72 |

| Os02g0590800 | Similar to Serine/threonine-protein kinase Nek6 | Phosphorylation | 4.47 |

| Os05g0414700 | Serine/threonine protein kinase domain containing protein | Phosphorylation | 3.93 |

| Os01g0689900 | Serine/threonine protein kinase-related domain containing protein | Phosphorylation | 3.47 |

| Os06g0602500 | Serine/threonine protein kinase-related domain containing protein | Phosphorylation | 3.15 |

| Os10g0431900 | Serine/threonine protein kinase-related domain containing protein | Phosphorylation | 2.79 |

aInformation based on RAP-DB (http://rapdb.dna.affrc.go.jp/)

Fig. 3.

Gene expression pattern of transcription factors, metabolic and signal transduction genes in coleoptiles of rad mutant after 7 days under complete submergence. Rice seeds (rad mutant and WT) were germinated under complete submergence for seven days after imbibition. Coleoptiles were dissected from rice seedlings, and total RNA was extracted. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed for the selected genes listed in Fig. 1. Transcript levels of each gene were normalized to the transcript levels of rice TF2E (Os10g0397200) gene (used as a control gene). Each data point represents the means ± SD (n = 3)

The bHLH TF family acts as either transcriptional activators or repressors and sometime forms complexes by interacting with MYB and other regulatory proteins that either activate or repress the expression of target genes (Feller et al. 2011). It has been shown that bHLH acts negatively to control seed germination and expansion of cotyledons (Groszmann et al. 2010). In rad mutant, it appears to be either directly acting as a repressor or interacting with MYB and other factors to repress the coleoptile elongation. Additionally, identification of w-box associated with WRKY, significant increase in the expression of WRKY 24 by qRT-PCR analysis, and upregulation of WRKY 1, 5, 19, 24, 28, 68 and 77 genes (Table 3) altogether support the involvement of WRKY in the reduced coleoptile elongation in the rad mutant. Gene regulation occurs mainly due to combinational interaction among different TFs (Istrail and Davidson 2005). Our identification of the cis-element distribution and enrichment analysis provides a potentially meaningful view of the combinational role of different TFs in balancing the metabolic status of the rad mutant for survival by reducing coleoptile elongation. It also highlights the absence of such regulatory control in the transcriptional network when ADH1 function is normal.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Synthetic Biology Initiative of the National University of Singapore (DPRT/943/09/14), Biomedical Research Council of A*STAR (Agency for Science, Technology and Research), Singapore and a grant from the Next-Generation BioGreen 21 Program (SSAC, No. PJ01109405), Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

Authors’ contributions

BM and DYL conceived and designed the study. BM analyzed and interpreted the data. BM and BDLR wrote the manuscript. HT performed the qRT-PCR analysis. EW developed the promoter database for rice, extracted the promoter sequences and developed the gene regulatory network. DYL and MN critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

- ABA

Abscisic acid

- ADH1

Alcohol dehydrogenase 1

- CIPK23

Serine/threonine protein kinase

- GA

Gibberellic acid

- nt

Nucleotide

- PPi-PFK

Ppyrophosphate-dependent phosphofructo-1-kinase-like protein

- rad

Reduced adh activity

- TFs

Transcription factors

- TSS

Transcription start site

- WT

Wild-type

Additional files

Materials and methods. (DOCX 22 kb)

Potential transcriptional activators and repressors that regulate reduced coleoptile elongation under complete submergence. (DOCX 39 kb)

Presence of common putative cis-elements in the promoters of key genes in the rad mutant. The presence of putative cis-elements for binding to potential transcription factors are shown in different strands of the promoter regions (-1000, +200 relative to TSS) of Os06g0220500 (UDP-glucuronosyl/UDP-glucosyltransferase family protein), Os12g0268000 (Similar to cytochrome P450 family), Os01g0716500 (Methyltransferase type 12 domain containing protein), and Os05g0194900 (pyrophosphate-dependent phosphofructo-1-kinase-like protein). TSS: Transcription starts site; T - TATA - box; A - ABI4; B - bZIP (Gr. A); b - bZIP (Gr. D, I, S); E - ERF; H - bHLH; M - MYB and W - WRKY. (TIF 49 kb)

Gene regulatory network of rad mutant having reduced ADH1 activity. A set of key potential TF genes such as, Os01g0826400 (WRKY transcription facto 24), Os05g0571200 (Similar to WRKY transcription factor 19), Os01g0187900 (Similar to Transcription factor MYBS2) and Os04g0547600 (Pathogenesis-related transcriptional factor and ERF domain containing protein) involved in the activation and repression of coleoptile elongation showing link to different processes involved in the rad mutant. (TIF 1006 kb)

Primer list for qRT-PCR. (DOCX 13 kb)

Contributor Information

Bijayalaxmi Mohanty, Email: chebijay@nus.edu.sg.

Hirokazu Takahashi, Email: hiro_t@agr.nagoya-u.ac.jp.

Benildo G. de los Reyes, Email: benildo.reyes@ttu.edu

Edward Wijaya, Email: ewijaya@ifrec.osaka-u.ac.jp.

Mikio Nakazono, Email: nakazono@agr.nagoya-u.ac.jp.

Dong-Yup Lee, Phone: +65-6516-6907, Email: cheld@nus.edu.sg.

References

- ap Rees T, Jenkin LET, Smith AM, Wilson PM. The metabolism of flood tolerance plants. In: Crawford RMM, editor. Plant life in aquatic and amphibious habitats. Oxford: Blackwell; 1987. pp. 227–238. [Google Scholar]

- Ayyappan V, Kalavacharla V, Thimmapuram J, Bhide KP, Sripathi VR, Smolinski TG, Manoharan M, Thurston Y, Todd A, Kingham B. Genome-Wide Profiling of Histone Modifications (H3K9me2 and H4K12ac) and Gene Expression in Rust (Uromyces appendiculatus) Inoculated Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0132176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey-Serres J, Voesenek LA. Flooding stress: acclimations and genetic diversity. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2008;59:313–339. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller A, Machemer K, Braun EL, Grotewold E. Evolutionary and comparative analysis of MYB and bHLH plant transcription factors. Plant J. 2011;66(1):94–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenway H, Gibbs J. Mechanism of anoxia tolerance in plants. I. Growth, survival and anaerobic catabolism. Funct Plant Biol. 2003;30:1–47. doi: 10.1071/PP98096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groszmann M, Bylstra Y, Lampugnani ER, Smyth DR. Regulation of tissue-specific expression of SPATULA, a bHLH gene involved in carpel development, seedling germination, and lateral organ growth in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2010;61:1495–1508. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberer G, Hindemitt T, Meyers BC, Mayer KF. Transcriptional similarities, Dissimilarities and conservation of cis-elements in duplicated genes of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2004;136:3009–3022. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.046466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao TC. Plant response to water stress. Ann Rev Plant Physiol. 1973;24:519–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.24.060173.002511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Colmer TD, Millar AH. Does anoxia tolerance involve altering the energy currency towards PPi? Trends Plant Sci. 2008;13:221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Istrail S, Davidson EH. Logic functions of the genomic cis-regulatory code. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:4954–4959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409624102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulik A, Wawer I, Krzywin E, Bucholc M, Dobrowolska G. SnRK2 protein kinases-key regulators of plant response to abiotic stresses. OMICS. 2011;15(12):859–872. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magneschi L, Perata P. Rice germination and seedling growth in the absence of oxygen. Ann Bot. 2009;103:181–196. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcn121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mapelli S, Locatelli F, Bertani A. Effect of anaerobic environment on germination and growth of rice and wheat: endogenous level of ABA and IAA. Bulg. J. Plant Physiol. 1995;21(2-3):33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Margolin AA, Wang K, Lim WK, Kustagi M, Nemenman I, Califano A. Reverse engineering cellular networks. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:662–671. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura H, Takano T, Takeda G, Uchimiya H. Adh1 is transcriptionally active but its translational product is reduced in a rad mutant of rice (Oryza sativa L.), which is vulnerable to submergence stress. Theor Appl Genet. 1998;97:1197–1203. doi: 10.1007/s001220051010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima K, Takasaki H, Mizoi J, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. NAC transcription factors in plant abiotic stress responses. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1819:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saika H, Matsumura H, Takano T, Tsutsumi N, Nakazono M. A point mutation of Adh1 gene is involved in the repression of coleoptile elongation under submergence in rice. Breeding Sci. 2006;56:69–74. doi: 10.1270/jsbbs.56.69. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Saika H, Matsumura H, Nagamura Y, Tsutsumi N, Nishizawa NK, Nakazono M. Cell division and cell elongation in the coleoptile of rice alcohol dehydrogenase 1-deficient mutant are reduced under complete submergence. Ann Bot. 2011;108(2):253–261. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcr137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Greenway H, Matsumura H, Tsutsumi N, Nakazono M. Rice alcohol dehydrogenase 1 promotes survival and has a major impact on carbohydrate metabolism in the embryo and endosperm when seeds are germinated in partially oxygenated water. Ann Bot. 2014;113:851–859. doi: 10.1093/aob/mct305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada R, Johzuka-Hisatomi Y, Saitoh M, Asao H, Iida S. Gene targeting by homologous recombination as a biotechnological tool for rice functional Genomics. Plant Physiol. 2007;144:846–856. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.095992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt T, Jones P. Glycosyltransferases in plant natural product synthesis: characterization of a supergene family. Trends Plant Sci. 2000;5:380–386. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01720-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Wu R. Rice alcohol-dehydrogenase genes: anaerobic induction, organ specific expression and characterization of cDNA clones. Plant Molecular Biol. 1989;13:53–68. doi: 10.1007/BF00027335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]