Abstract

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are the best characterized adult stem cells and the only stem cell type in routine clinical use. The concept of stem cell transplantation laid the foundations for the development of novel cell therapies within, and even outside, the hematopoietic system. Here, we report on the history of hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) and of HSC isolation, we briefly summarize the capabilities of HSCs to reconstitute the entire hemato/lymphoid cell system, and we assess current indications for HCT. We aim to draw the lines between areas where HCT has been firmly established, areas where HCT can in the future be expected to be of clinical benefit using their regenerative functions, and areas where doubts persist. We further review clinical trials for diverse approaches that are based on HCT. Finally, we highlight the advent of genome editing in HSCs and critically view the use of HSCs in non-hematopoietic tissue regeneration.

Key Words: Hematopoietic stem cells, Autologous and allogeneic transplantation, Hematopoietic reconstitution, Hematopoietic cell transplantation in hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic conditions

Introduction

Stem cell transplantation in the context of regenerative medicine relies on the unique potential of stem cells to regenerate the entire stem cell system, including all progenitor and mature cell types, and thereby to reconstitute damaged tissues [1]. This was impressively demonstrated by hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) which, following transplantation, give rise to all hemato/lymphoid lineages, leading to a life-long reconstitution of the entire hematopoietic system. This exclusive potential makes HSCs a clinically relevant stem cell type. The developmental potential of HSCs is generally regarded as being limited in the sense that HSCs are committed exclusively to their tissue of origin, namely the hematopoietic system. However, some studies claimed that HSCs can also contribute to unrelated tissues and thus show a broad non-tissue-restricted differentiation potential [2]. Here we review basic biological and clinical aspects of HSCs, and we discuss myths, facts, and future directions of clinical HSC biology.

A Brief History of Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation

Fundamental work on the biology of radiation-induced tissue damage during the first decades following World War II constituted the stem cell research field and generated a series of seminal findings in animal models that paved the way for today's therapeutic use of HSCs. The era of hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) began with work done by Lorenz et al. [3] and Jacobson and colleagues [4] who showed that lead shielding of the spleen and bone marrow protected mice from the lethal effects of ionizing radiation and that transplantation of spleen or marrow cells into X-irradiated animals mediated the protection from hematopoietic death. The field of HCT began with these observations: In 1961, Till and McCulloch [2] reported in a landmark paper a method for the quantification of hematopoietic progenitor and stem cells by the spleen colony-forming unit (CFU-s) assay. This paper and subsequent work revealed that the normal hematopoietic compartment is structured as a hierarchy with HSCs at the top and that clonal cells in the marrow can differentiate into all blood cell lineages. In aggregate, the results showed that stem cells are rare cells with two functional attributes that distinguish them from all other cell types in the body: i) They have the capacity to replicate to form daughter cells with a similar developmental potential, that is to self-renew; ii) they have the capacity to differentiate via progenitor cells into a large number of mature cell types that carry out tissue-specific functions [5].

In parallel to the work done to characterize the biological properties of HSCs, there was a sense that before HCT could be used to treat hematological malignancies, the transplantation barrier imposed by differences in surface antigens between donor and recipient cells had to be overcome. In the 1950s and 1960s, a number of small and large animal models were established to elucidate the molecular components of histocompatibility relevant for allogeneic HCT. In 1959, Thomas et al. [6,7] reported that bone marrow from a healthy identical twin restored the blood system of a leukemic child. This and other observations revealed that a high degree of serological or genetic matching between donor and recipient is required and, of similar importance, that the graft mounted an immune reaction against the leukemia [8]. Building on observations from allogeneic bone marrow transplantations between dogs with matched and unmatched leukocyte antigens and refining the ablative regiment to destroy the tumor cells, Thomas and his team overcame one of the main hurdles of allogeneic cell transplantations by carefully selecting donor/patient matches for human leukocyte antigen (HLA) types before bone marrow transplantation [9,10] and thereby paved the way to the establishment of successful HCTs.

The Entire Hematopoietic System Can Be Reconstituted by a Minute Population of Stem Cells

In spite of the progress made in the development of autologous and allogeneic HCT between 1960 and 1980, it was not clear which cell type is responsible for the complete and long-term repopulation of the hematopoietic system in recipients and whether it can be phenotypically defined. An obstacle to studying HSCs however is that these exquisite cells are found at a very low frequency.

As the mouse is an indispensable model system for studying hematopoiesis, these studies were done on murine bone marrow cells. Early studies aiming to purify HSCs used a separation of cells by size and density [11]. Later, antibodies against mature and progenitor cells plus flow cytometric sorting (FACS) were deployed to prospectively isolate HSCs with the use of a variety of phenotypic surface markers. 30 of the sorted lineage maker negative (LIN-), Thy1low and Sca1+ cells were sufficient to save half of the lethally irradiated mice and to reconstitute all blood cell types [12]. Further research showed that injection of a single CD34low/-, c-Kit+, Sca-1+, Kit+, LIN- cell into irradiated mice resulted in long-term reconstitution of the lympho/hematopoietic system [13]. Also alternative surface markers such as the SLAM (signaling lymphocyte activation molecule) receptors (CD150, CD244, and CD48), DNA binding dyes or the aldehyde dehydrogenase activity were used to distinguish and separate mature and progenitor cells from HSCs [14]. The establishment of clonal assays and stringent functional read out systems greatly facilitated the identification of hematopoietic progenitor and stem cells [15].

The search for human HSCs used the murine HSC isolation strategy as a template, including cell separation based on the absence or presence of specific surface markers. Rapidly, the purification of human HSCs centered around the glycoprotein CD34 which is expressed in rare bone marrow cells [16]. CD34 expression ceases during hematopoietic development. The stem cell antigen CD34 enriches clonogenic hematopoietic progenitor cells and CD34+ cells engraft the hematopoietic system in baboons and in patients [17,18]. After establishing immune-deficient xenograft models for the efficient engraftment of the human hematopoietic system in mice, Bhatia et al. [19] showed that human HSCs have a LIN-, CD34+ and CD38- phenotype. Further multi-parametric flow cytometry and immune phenotyping showed that purified human HSCs express CD34, CD90 and CD49f but not CD38 or CD45RA [20].

The ability to highly purify HSCs facilitates molecular analyses that aim to better understand the growth and differentiation properties of this rare but potent cell type. Purification of HSCs can also be used to develop rational treatment options against leukemic cells. Currently, most clinical HSC transplants use mononuclear cell fractions from bone marrow, peripheral blood, or cord blood. However, techniques which enrich HSCs and deplete accessory cells have been developed and have in part been introduced into clinical practice, as outlined below. For further details on the isolation and molecular regulation of human HSCs see Weissman and Shizuru [21] and Doulatov et al. [20].

Establishment of Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation as a Revolutionary Treatment for Life-Threatening Hematopoietic Diseases

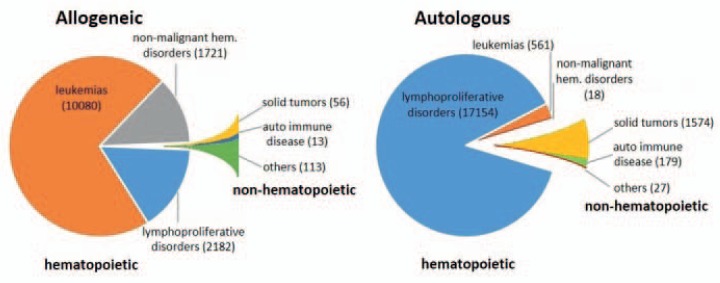

The success of allogeneic HCT in patients by Thomas and his team [9,10] created worldwide attention and spurred enormous activities to establish this complex treatment for more patients. In addition to acute myeloid leukemia and primary immune deficiencies, HCT was established as a therapy for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia, acute lymphatic leukemia, aplastic anemia, and hemoglobinopathies [22,23]. Following conditioning by chemo- or irradiation therapy and HCT, the regeneration of the hematopoietic system is almost universally achieved within 2-4 weeks. However, major mortality is caused by acute and/or chronic graft-versus-host disease, or relapse in the case of malignancy. If stable donor-type hematopoietic chimerism is reached, cure rates are between 30 and 70% for several malignant diseases and even higher in children [24]. Figure 1 gives an overview on the current diagnoses leading to allogeneic HCTs performed 2012 in Europe. In 2012, 37,818 HCTs were conducted in a total of 33,678 patients (14,165 allogeneic, 19,513 autologous) [25]. The diagnoses comprise leukemic and lymphoproliferative disorders as well as benign inherited hematopoietic diseases, and only a relatively minute fraction of other indications.

Fig. 1.

Numbers of HCTs performed in Europe in 2012 by donor type and indication. Shown are numbers of HCTs in patients with the indicated donor types and disease groups as reported by the Registry of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). Total numbers of HCTs are given in brackets. Data were extracted from [25].

Allogeneic and autologous HCTs represent fundamentally different transplantation strategies. In allogeneic HCT, in addition to a new hematopoietic system, also a complete foreign immune system is transplanted. This includes the potential generation of an anti-leukemia reactivity. Allogeneic HCT requires matched donors and elaborated pre-transplant diagnostics to select the best possible transplant as well as highly complex treatment schedules. In autologous HCT the patient's own HSCs are transplanted. Autologous HCT is the preferred treatment option for patients with tumors of the lymphatic system such as multiple myeloma or various forms of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) [26]. Autologous HCT has evolved as an alternative for patients who are physically less suitable and/or lack a suitable donor. Autologous HCT has also been extended to patients with some solid tumors, including pediatric and germ cell tumors [27]. In a more recent approach, autologous HCT has been established for the treatment of autoimmune diseases following rigorous depletion of autoreactive lymphocytes [28]. Whereas in solid tumors HSCs mediate primarily the reconstitution of the hematopoietic system, in autoimmune diseases they are mainly employed to replenish lymphopoiesis after dose-intensified eradication of lymphocytes. Current diagnoses for autologous HCT are also summarized in figure 1.

Prerequisites for the Clinical Use of Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation

The routine clinical use of HCT also required the overcoming of a number of other critical hurdles. Firstly, effective preparatory regimens which safeguard the thorough and permanent ablation of malignant cells and which at the same time suppress the host's immune system were developed [24,29]. Secondly, the selection of suitable donors by quality-assured HLA typing was established using standardized nomenclature for HLA types and worldwide cooperation of donor registries [30,31]. Thirdly, methodologies were developed intended to pharmacologically suppress immune reactions during the engraftment phase, specifically graft-versus-host disease and host-versus-graft reactions resulting in engraftment failure [23,31]. Also, substitution of platelets and erythrocytes by transfusions and refined antibiotic regimens to prevent infection during hematopoietic aplasia including antiviral and anti-fungal medications may become necessary [24]. Finally, protocols for a sensitive monitoring of the regeneration of the hematopoietic and immune cells and the early recognition of potential disease relapses were established [32]. For a more detailed review on the current status of both allogeneic and autologous HCT see Gyurkocza et al. [24].

What Is an Ideal Hematopoietic Cell Graft?

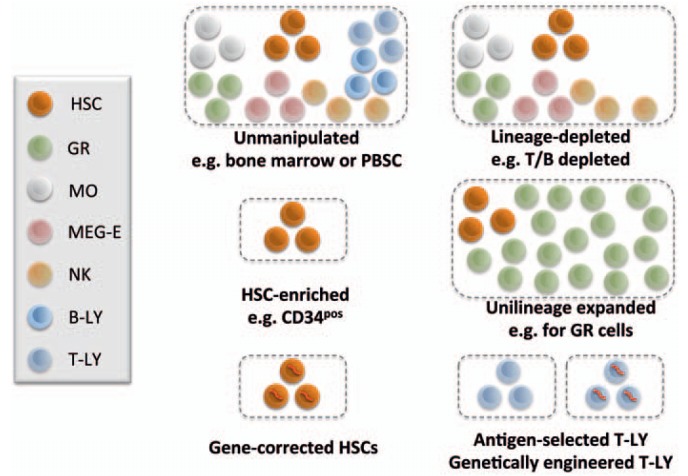

During the establishment period of HCT, bone marrow obtained under general anesthesia was used as a source of hematopoietic cells. The availability of hematopoietic colony stimulating factors (CSFs) and the observation that short-term granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) treatment mobilizes HSCs into the blood, led to the establishment of peripheral blood stem and progenitor cells (PBSC) as an efficient and easily obtainable HCT graft [33,34]. In a series of single patient trials in children for whom no donor was available, cord blood preserved from their younger siblings has been introduced as a third source of HSCs in the clinic. This transplant source has been originally established for patients in lack of a suitable donor using either family members or unrelated donors, and has since been established as a valuable transplant source for children [35,36]. Routinely, most current HCT grafts nowadays contain in addition to HSCs both accompanying progenitor cells and different mature cell types (fig. 2). Co-transplanted lymphocytes constitute effectors of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease and are potentially highly detrimental to the treatment outcome. This pushed the development of technologies that remove lymphocytes from the graft or, alternatively, allow enrichment of HSCs by positive selection [37,38,39]. The possibility to deplete T and B lymphocytes down to low numbers in HSC grafts or, alternatively, by in vivo depletion using post-transplant cyclophosphamide has widened the use of allogeneic HCT in children by using parents as donors in haploidentical stem cell transplantation [40]. Natural killer (NK) cells contained in the graft were found beneficial, since they can carry anti-leukemic potential and may be preserved or also enriched [41]. The CD34+ cell fraction has been found to contain virtually all cells required for long-term and multi-lineage hematopoietic engraftment, but no immune effector cells. This is of importance for HCT in patients with inherited immune deficiencies for whom no isogenic donors were available [42].

Fig. 2.

Graft types used for HCTs. Upon harvest, grafts for HCT can be: unfractionated bone marrow, mobilized peripheral blood (PBSC) or cord blood that contain progenitors with multi- or dual lineage differentiation potential together with mature cells of different lineages. Alternative grafts are lineage-depleted cell populations, cell populations that were selectively expanded in vitro, or HSCs transduced with a viral vector encoding an intact copy of a mutated gene. T-LYs cannot reconstitute hematopoiesis, but selected and/or genetically engineered T-LYs (e.g. CAR T cells) could erase leukemic cells. Here, HSCs include hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Cell lineages are symbolized using indicated colors as shown in the legend. GR = Granulocyte; MEG-E = megakaryocyte-erythrocyte; MO = monocyte, NK = natural killer; Ly = lymphocyte.

The possibility to ‘add back’ donor lymphocytes that were either separately frozen at the time of HSC harvest or collected from the donor later in critical clinical situations weeks to months after HCT has widened the therapeutic options of HCT and supports the concept of the still somewhat enigmatic ‘graft-versus-leukemia’ effector cells [43]. Thus, manipulated HCT grafts have been implemented into clinical practice mainly in allogeneic HCT to allow for a better control of immune rejection and graft-versus-host disease. More recently, approaches to deplete transplanted immune cells by application of cyclophosphamide immediately post transplantation yielded promising results. This could, at least in part, make some graft manipulations superfluous [44,45].

What Are Current Challenges in Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation?

Ethnical Issues

In most parts of the Western hemisphere, it is currently possible to find a donor with a suitable HLA match for the vast majority of patients. For members of many non-Caucasian population groups however, the chance to find a suitable donor is still much lower. Moreover, HCT has been established only slowly in less developed countries. This imposes great challenges on the stakeholders to transfer at least some of the benefits of HCT to more patients worldwide, supported by international programs such as the World Marrow Donor Association (WMDA) that aim to improve access to HCTs [46].

Understanding Better the Immunology Involved in Graft-versus-Host Disease and in Antitumor Activity

In a proportion of patients, immunological rejection or graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic HCT represents a major clinical problem. Studies are under way to evaluate how effective the current HLA matching and donor selections are performed and in which way improvements could be implemented, e.g. through the use of additional HLA or non-HLA determinants [46,47]. Moreover, haploidentical HCT harbors potential to make HCT accessible to more patient groups in the future [40,42]. In a different approach, the toxicity of the conditioning regimes was reduced [48,49]. The field of HCT application could potentially be widened, since allogeneic HCT induces immune tolerance to transplanted tissues and organs, e.g. the kidney [50]. This holds great promise to improve survival and function of transplanted organs, and possibly other issue transplants, but is still at a pre-clinical stage and does not necessarily need HSCs. In the area of leukemia therapy, a challenging question is the identification and characterization of the cell population(s) that cause the graft-versus-leukemia effect [51]. The identification of these cells serves as a means to analyze their presence and numbers in the donor and to isolate and infuse them in distinct clinical situations. The genetic modification to immune effector cells, e.g. T lymphocytes with recombinant chimeric antigen receptors as a tool to re-direct these cells to tumors, has been developed as a clinical tool in the last decade, leading to therapeutic successes already in children with acute lymphatic leukemia [52,53].

Insufficient HSC Numbers

The banking of cord blood HSCs has led to a further increase in the availability of HCT grafts with suitable HLA types for patients in need of allogeneic HCT [35]. However, small HSC numbers in these grafts correlate with delayed or even absent hematopoietic reconstitution. Both, double and triple cord blood transplantation protocols as well as ex vivo expansion protocols on stromal cell layers have demonstrated a potential to overcome engraftment deficits and to reduce graft failure rates [54]. Co-transplantation of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs), of ‘facilitating’ lymphocytes, or of ex vivo expanded neutrophil precursor cells may improve engraftment of transplants containing low HSC numbers, yet require further clinical development (fig. 2) [54,55,56,57]. Also, experimental work is needed to understand the molecular mechanisms that regulate the self-renewal and differentiation of HSCs. Recent pre-clinical studies indicated that strategies which specifically target both global and gene-specific histone modifications are effective for the robust ex vivo expansion of hematopoietic progenitor and stem cells [58,59,60]. The refinement and optimization of HSC expansion strategies using chromatin-modifying agents provides a potential new avenue for manufacturing increased numbers of HSCs.

New Stem Cell Sources

Potential sources for future HCT constitute embryonic stem cells, induced pluripotent stem cells and, lately, directly reprogrammed cells [61]. These strategies however are currently at a very early experimental stage, and their clinical use critically depends on the development of robust differentiation protocols that generate sufficient HCT for long-term and multi-lineage reconstitution in due time. Also, safety issues have to be clarified. It may prove difficult to carry these new strategies to transplantable progenitor and stem cells; however, they may generate mature cells such as erythrocytes for transplantation [62]. Rather than for transplantation therapy, these cell sources will become relevant for in vitro disease modeling, drug discovery, and toxicology studies.

Hematopoietic Cell Transplantations in Clinical Trials for Tissue Regeneration: Current Status

Clinical trials using HCT can be divided in two groups: one group are studies in which HCT aims at reconstituting the hematopoietic system (e.g. blood or bone marrow malignancies, non-malignant blood disease, solid tumors or autoimmune disease). In studies of the second group, the HCT is supposed to affect other tissues, such as liver, heart or neurologic tissues. As shown in table 1, approximately 92% of the clinical HCT trials aiming at reconstitution of the hematopoietic system are performed in the EU and North America. Notably, the relatively new emerging approaches aiming at regenerating non-hematopoietic tissues by HSC transplantation are mostly carried out in other countries than North America or the EU. Out of 136 studies concerning liver disease, heart disease, or neurologic disease, 47.1% are performed outside the EU and North America, most of them (38.9%) in Asia. This might be caused by a recent boom of the clinical trial sector in Asian countries and cultural issues as well. At this time, it seems difficult to draw conclusions regarding both the efficacy of these trials and the mechanisms by which they benefit non-hematopoietic tissues.

Table 1.

Clinical studies using HCT for hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic conditionsa

| Disease | Number of trails | North America | EU | Others | Phase 1 | Phase 1/2 | Phase 2 | Phase 2/3 | Phase 3 | Phase 4 | Recruiting and active | Terminated/withdrawn/suspended | Completed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leukemia/MDS/hematologic neoplasms | 1, 260 | 912 | 252 | 98 | 179 | 144 | 554 | 21 | 125 | 18 | 542 | 162 | 471 |

| Nonmalignant blood disease | 45 | 36 | 3 | 6 | 11 | 11 | 14 | 2 | 27 | 7 | 11 | ||

| Autoimmune disease | 24 | 25 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 5 | 1 | 13 | 8 | 2 | ||

| Solid tumors | 19 | 27 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 10 | ||||

| Metabolic disorders | 26 | 22 | 5 | 10 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 16 | 2 | 8 | ||

| Hepatic disease | 15 | 2 | 2 | 12* | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Neurologic disease | 54 | 27 | 5 | 32* | 19 | 15 | 11 | 1 | 34 | 4 | 15 | ||

| Cardiac disease | 67 | 14 | 33 | 20* | 9 | 12 | 23 | 9 | 7 | 32 | 8 | 27 |

Listed are studies concerning transplantation/infusion of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells or purified or non-purified cells derived from peripheral blood, bone marrow or cord blood. Numbers which do not add up to the total number of listed trials, are caused by missing information (e.g. phase or status) in the clinicaltrial.gov database. All categories of clinical trials were analyzed as described above. Except for the category ‘Leukemia/MDS/neoplasm', search results for each category were verified by manual analysis. Analyzed were clinical trials started from 1987 till 2016. (Date of analysis: 15.02.2016).

Mostly Asia (Liver 8/12; Heart 14/20; Neuro 31/32).

Myths, Facts, and Future Directions Using Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation to Regenerate Hematopoietic and Non-Hematopoietic Tissues

As indicated in the previous chapters, HSCs are the best characterized somatic stem cell type, and to date HSCs are the only stem cells in routine clinical use. Despite the extended knowledge on HSC biology, some time ago it came as a great surprise that several reports claimed that differentiating HSCs may cross germ layer boundaries and that they might be capable to differentiate into mature cells of unrelated stem cell systems. For example, pre-clinical studies suggested that HSCs from bone marrow and cord blood should have the ability to repair the infarcted heart, improving function and survival in a murine systems. Immediately, this observation triggered the launch not only of pre-clinical but, surprisingly, also of numerous clinical studies [63,64]. Based on these claims, a general debate emerged whether somatic stem cells including HSCs could have a wider, possibly even unlimited differentiation potential similar to pluripotent embryonic stem cells [65]. The hypothesis that adult stem cells can ‘transdifferentiate’ was based on the concept that the lineage commitment of differentiated cells may be not as fixed as previously believed, and that environmental cues can alter cell lineage identities [66]. However, further studies using state-of-the-art cell and stringent molecular tools that allowed the clonal tracking of cells failed to demonstrate reproducibility and seriously challenged the notion of adult stem cell plasticity. In contrast to the hypothesized ‘transdifferentiation’, these studies revealed that the majority of the transplanted HSCs either died or differentiated into hematopoietic cells and that some progeny of HSCs can, at low frequencies, fuse with unrelated cells such as cardiomyocytes [67,68]. Furthermore, a critical evaluation of clinical trials in patients with acute and chronic heart disease from diverse etiologies revealed that bone marrow cells neither engrafted over significant time periods nor differentiated into cardiomyocytes, and only modest short- und no long-term benefits of transplanted bone marrow cells were seen [69]. Similarly, proof is lacking in both pre-clinical and also clinical studies that HSCs confer regenerative functions for tissue systems other than lymphohematopoiesis. Thus, the developmental potential of HSCs, similar as that of other adult stem cell types, is restricted to their innate stem cell system and tissue. The benefit of ectopically transplanted HSCs therefore most likely is based on paracrine effects [70]. Considered with hindsight, this episode calls for great caution before pushing laboratory studies into the clinics and prematurely publishing paradigm shifts.

A dream that has come true for basic and applied researchers is the development of tools for the efficient and safe modification of specific genomic loci in HSCs and in other cell types. To date, gene delivery has generally relied on the use of viral vectors with random genome integration into the host DNA and their inherent difficult to influence and variable gene expression levels. In the past few years, specific gene ‘scissors’ including zinc-finger nucleases (ZFN), transcription-activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) and CRISPR/Cas9 (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/RNA-guided nuclease CAS9) were developed for the efficient modification of any genetic loci in any cell type [71]. The RNA-guided CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing tool has particularly revolutionized basic and applied science similar to the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technology, which opened new avenues of genetic testing and manipulation. In nature, CRISPR/Cas9 is part of a bacterial defense system. The CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing is a new development, and its applicability in a variety of cell types including early embryonic and adult stem cells such as murine and human HSCs was shown [72,73]. Furthermore, the genomes of monkey and human zygotes were efficiently modified by CRISPR/Cas9, although the genomes also contained unwanted off-target mutations [74,75]. The feasibility of human germ line gene modification sparked high-profile debates about the ethical implications of such work.

Clinical genome editing was first described in 2009 using ZFN-based gene editing of the HIV receptor CCR5 in autologous CD4+ T cells of HIV patients [76], and a ZFN-based gene editing trial to prove the feasibility of a genetic therapy in hemophilia patients is underway [77]. The potential of this technology for a genetic therapy of multiple disease-causing mutations such as β-thalassemia or primary immune deficiencies is currently being explored [78,79]. The newly engineered high-fidelity Cas9 variant with no detectable off-target effects provides a further advance for the potential therapeutic application of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing tools [80]. In conclusion, the possibility and first clinical application of precise genetic modification of HSCs is evidence that the age of clinical genome engineering has begun.

Outlook

As reviewed above, HCT developed from an experimental concept to a safe clinical cure for an ever-increasing number of indications related to hematopoietic regeneration. In contrast, the role of HSCs in the regeneration of unrelated tissues lacks proof. Despite the firm anchorage of HCT in everyday clinical practice, the HSC field still faces critical challenges, such as insufficiencies in donor repertoire for a number of ethnicities which is increasingly overcome by haplo-HCT, insufficient HSC numbers e.g. in cord blood samples, a lack of efficient HSC expansion protocols, innovative ways to fine-tune immune suppression as well as reagents and methods that allow to better detect, isolate and culture-expand tumor-targeting immune cells. Both basic and clinical research communities will have to intensify their joint efforts to further develop evidence-based cures in order to give more, and also more elderly, patients access to the benefits of HCT.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Martin Stoddart for his critical reading of the manuscript and Martin Hildebrandt for suggestions and discussion. This work was supported by a grant from the German Research Council (DFG, SPP1463) to AMM.

References

- 1.Trounson A, McDonald C. Stem cell therapies in clinical trials: progress and challenges. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Till JE, McCulloch EA. A direct measurement of the radiation sensitivity of normal mouse bone marrow cells. Radiat Res. 1961;14:213–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lorenz E, Uphoff D, Reid TR, Shelton E. Modification of irradiation injury in mice and guinea pigs by bone marrow injections. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1951;12:197–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobson LO, Marksk EK, Robsonk MJ, Gastonk EO, Zirklek RE. Effect of spleen protection on mortality following X-irradiation. J Lab Clin Med. 1949;34:1538–1543. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chao MP, Seita J, Weissman IL. Establishment of a normal hematopoietic and leukemia stem cell hierarchy. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2008;73:439–449. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2008.73.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas ED, Lochte HL, Jr, Lu WC, Ferrebee JW. Intravenous infusion of bone marrow in patients receiving radiation and chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 1957;257:491–496. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195709122571102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas ED, Lochte HL, Jr, Cannon JH, Sahler OD, Ferrebee JW. Supralethal whole body irradiation and isologous marrow transplantation in man. J Clin Invest. 1959;38:1709–1716. doi: 10.1172/JCI103949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnes DW, Corp MJ, Loutit JF, Neal FE. Treatment of murine leukaemia with X rays and homologous bone marrow; preliminary communication. Br Med J. 1956;2:626–627. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4993.626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas ED, LeBlond R, Graham T, Storb R. Marrow infusions in dogs given midlethal or lethal irradiation. Radiat Res. 1970;41:113–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas ED, Buckner CD, Rudolph RH, Fefer A, Storb R, Neiman PE, Bryant JI, Chard RL, Clift RA, Epstein RB, Fialkow PJ, Funk DD, Giblett ER, Lerner KG, Reynolds FA, Slichter S. Allogeneic marrow grafting for hematologic malignancy using HL-A matched donor-recipient sibling pairs. Blood. 1971;38:267–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iscove NN, Messner H, Till JE, McCulloch EA. Human marrow cells forming colonies in culture: analysis by velocity sedimentation and suspension culture. Ser Haematol. 1972;5:37–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spangrude GJ, Heimfeld S, Weissman IL. Purification and characterization of mouse hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 1988;241:58–62. doi: 10.1126/science.2898810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osawa M, Hanada K, Hamada H, Nakauchi H. Long-term lymphohematopoietic reconstitution by a single CD34-low/negative hematopoietic stem cell. Science. 1996;273:242–245. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiel MJ, Yilmaz OH, Iwashita T, Yilmaz OH, Terhorst C, Morrison SJ. Slam family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell. 2005;121:1109–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dykstra B, Olthof S, Schreuder J, Ritsema M, De Haan G. Clonal analysis reveals multiple functional defects of aged murine hematopoietic stem cells. J Exp Med. 2011;208:2691–2703. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Civin CI, Strauss LC, Brovall C, Fackler MJ, Schwartz JF, Shaper JH. Antigenic analysis of hematopoiesis. III. A hematopoietic progenitor cell surface antigen defined by a monoclonal antibody raised against kg-1a cells. J Immunol. 1984;133:157–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berenson RJ, Andrews RG, Bensinger WI, Kalamasz D, Knitter G, Buckner CD, Bernstein ID. Antigen CD34+ marrow cells engraft lethally irradiated baboons. J Clin Invest. 1988;81:951–955. doi: 10.1172/JCI113409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berenson RJ, Bensinger WI, Hill R, Andrews RG, Garcia-Lopez J, Kalamasz DF, Still BJ, Buckner CD, Bernstein ID, Thomas ED. Stem cell selection - clinical experience. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1990;333:403–410. discussion 411-413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhatia M, Wang JC, Kapp U, Bonnet D, Dick JE. Purification of primitive human hematopoietic cells capable of repopulating immune-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:5320–5325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doulatov S, Notta F, Laurenti E, Dick JE. Hematopoiesis: a human perspective. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:120–136. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weissman IL, Shizuru JA. The origins of the identification and isolation of hematopoietic stem cells, and their capability to induce donor-specific transplantation tolerance and treat autoimmune diseases. Blood. 2008;112:3543–3553. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-078220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Little MT, Storb R. History of haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:231–238. doi: 10.1038/nrc748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gratwohl A, Niederwieser D. History of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: evolution and perspectives. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2012;43:81–90. doi: 10.1159/000335266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gyurkocza B, Rezvani A, Storb RF. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: the state of the art. Expert Rev Hematol. 2010;3:285–299. doi: 10.1586/ehm.10.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Passweg JR, Baldomero H, Peters C, Gaspar HB, Cesaro S, Dreger P, Duarte RF, Falkenburg JH, Farge-Bancel D, Gennery A, Halter J, Kroger N, Lanza F, Marsh J, Mohty M, Sureda A, Velardi A, Madrigal A, European Society for Bone Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Hematopoietic SCT in Europe: data and trends in 2012 with special consideration of pediatric transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49:744–750. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Majhail NS, Farnia SH, Carpenter PA, Champlin RE, Crawford S, Marks DI, Omel JL, Orchard PJ, Palmer J, Saber W, Savani BN, Veys PA, Bredeson CN, Giralt SA, LeMaistre CF. Indications for autologous and allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: Guidelines from the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21:1863–1869. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Einhorn LH, Williams SD, Chamness A, Brames MJ, Perkins SM, Abonour R. High-dose chemotherapy and stem-cell rescue for metastatic germ-cell tumors. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:340–348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sullivan KM, Muraro P, Tyndall A. Hematopoietic cell transplantation for autoimmune disease: updates from Europe and the United States. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:S48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mathe G, Thomas ED, Ferrebee JW. The restoration of marrow function after lethal irradiation in man: a review. Transplant Bull. 1959;6:407–409. doi: 10.1097/00006534-195910000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Navarro WH, Switzer GE, Pulsipher M. National marrow donor program session: donor issues. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(1 suppl):S15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomas ED. A history of haemopoietic cell transplantation. Br J Haematol. 1999;105:330–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1999.01337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nierkens S, Lankester AC, Egeler RM, Bader P, Locatelli F, Pulsipher MA, Bollard CM, Boelens JJ, Westhafen Intercontinental Group Challenges in the harmonization of immune monitoring studies and trial design for cell-based therapies in the context of hematopoietic cell transplantation for pediatric cancer patients. Cytotherapy. 2015;17:1667–1674. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siena S, Bregni M, Gianni AM. Mobilization of peripheral blood progenitor cells for autografting: Chemotherapy and G-CSF or GM-CSF. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 1999;12:27–39. doi: 10.1053/beha.1999.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anasetti C, Logan BR, Lee SJ, Waller EK, Weisdorf DJ, Wingard JR, Cutler CS, Westervelt P, Woolfrey A, Couban S, Ehninger G, Johnston L, Maziarz RT, Pulsipher MA, Porter DL, Mineishi S, McCarty JM, Khan SP, Anderlini P, Bensinger WI, Leitman SF, Rowley SD, Bredeson C, Carter SL, Horowitz MM, Confer DL, Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network Peripheral-blood stem cells versus bone marrow from unrelated donors. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1487–1496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gluckman E, Ruggeri A, Rocha V, Baudoux E, Boo M, Kurtzberg J, Welte K, Navarrete C, Van Walraven SM, Eurocord World Marrow Donor Association and National Marrow Donor Program Family-directed umbilical cord blood banking. Haematologica. 2011;96:1700–1707. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.047050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Danby R, Rocha V. Improving engraftment and immune reconstitution in umbilical cord blood transplantation. Front Immunol. 2014;5:68. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shpall EJ, Jones RB, Bearman SI, Stemmer SM, Purdy MH, Heimfeld S, Berenson RJ. Positive selection of CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells for transplantation. Stem Cells. 1993;11((suppl 3)):48–49. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530110913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miltenyi S. Cd34+ selection: the basic component for graft engineering. Oncologist. 1997;2:410–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Locatelli F, Bauquet A, Palumbo G, Moretta F, Bertaina A. Negative depletion of alpha/beta+ T cells and of CD19+ B lymphocytes: a novel frontier to optimize the effect of innate immunity in HLA-mismatched hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Immunol Lett. 2013;155:21–23. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2013.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oevermann L, Lang P, Feuchtinger T, Schumm M, Teltschik HM, Schlegel P, Handgretinger R. Immune reconstitution and strategies for rebuilding the immune system after haploidentical stem cell transplantation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1266:161–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ruggeri L, Parisi S, Urbani E, Curti A. Alloreactive natural killer cells for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia: from stem cell transplantation to adoptive immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2015;6:479. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reisner Y, Aversa F, Martelli MF. Haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: state of art. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50(suppl 2):S1–5. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kolb HJ. Graft-versus-leukemia effects of transplantation and donor lymphocytes. Blood. 2008;112:4371–4383. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-077974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Al-Homsi AS, Roy TS, Cole K, Feng Y, Duffner U. Post-transplant high-dose cyclophosphamide for the prevention of graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21:604–611. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bashey A. Peripheral blood stem cells for T cell-replete nonmyeloablative hematopoietic transplants using post-transplant cyclophosphamide. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20:598–599. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bochtler W, Maiers M, Bakker JN, Oudshoorn M, Marsh SG, Baier D, Hurley CK, Muller CR. World marrow donor association framework for the implementation of HLA matching programs in hematopoietic stem cell donor registries and cord blood banks. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2011;46:338–343. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bacigalupo A. Matched and mismatched unrelated donor transplantation: is the outcome the same as for matched sibling donor transplantation? Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2012;2012:223–229. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2012.1.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Slavin S, Nagler A, Naparstek E, Kapelushnik Y, Aker M, Cividalli G, Varadi G, Kirschbaum M, Ackerstein A, Samuel S, Amar A, Brautbar C, Ben-Tal O, Eldor A, Or R. Nonmyeloablative stem cell transplantation and cell therapy as an alternative to conventional bone marrow transplantation with lethal cytoreduction for the treatment of malignant and nonmalignant hematologic diseases. Blood. 1998;91:756–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reshef R, Porter DL. Reduced-intensity conditioned allogeneic SCT in adults with AML. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50:759–769. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zakrzewski JL, Van den Brink MR, Hubbell JA. Overcoming immunological barriers in regenerative medicine. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:786–794. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ramos CA, Heslop HE, Brenner MK. CAR-T cell therapy for lymphoma. Annu Rev Med. 2016;67:165–183. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-051914-021702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stauss HJ, Morris EC, Abken H. Cancer gene therapy with T cell receptors and chimeric antigen receptors. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2015;24:113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weiden PL, Flournoy N, Thomas ED, Prentice R, Fefer A, Buckner CD, Storb R. Antileukemic effect of graft-versus-host disease in human recipients of allogeneic-marrow grafts. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:1068–1073. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197905103001902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mehta RS, Rezvani K, Olson A, Oran B, Hosing C, Shah N, Parmar S, Armitage S, Shpall EJ. Novel techniques for ex vivo expansion of cord blood: clinical trials. Front Med (Lausanne) 2015;2:89. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2015.00089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bernardo ME, Fibbe WE. Mesenchymal stromal cells and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Immunol Lett. 2015;168:215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kallekleiv M, Larun L, Bruserud O, Hatfield KJ. Co-transplantation of multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cytotherapy. 2016;18:172–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McNiece I, Jones R, Bearman SI, Cagnoni P, Nieto Y, Franklin W, Ryder J, Steele A, Stoltz J, Russell P, McDermitt J, Hogan C, Murphy J, Shpall EJ. Ex vivo expanded peripheral blood progenitor cells provide rapid neutrophil recovery after high-dose chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer. Blood. 2000;96:3001–3007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Obier N, Uhlemann CF, Muller AM. Inhibition of histone deacetylases by trichostatin a leads to a HOXB4-independent increase of hematopoietic progenitor/stem cell frequencies as a result of selective survival. Cytotherapy. 2010;12:899–908. doi: 10.3109/14653240903580254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Varagnolo L, Lin Q, Obier N, Plass C, Dietl J, Zenke M, Claus R, Muller AM. Prc2 inhibition counteracts the culture-associated loss of engraftment potential of human cord blood-derived hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12319. doi: 10.1038/srep12319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Milhem M, Mahmud N, Lavelle D, Araki H, DeSimone J, Saunthararajah Y, Hoffman R. Modification of hematopoietic stem cell fate by 5aza 2'deoxycytidine and trichostatin A. Blood. 2004;103:4102–4110. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vo LT, Daley GQ. De novo generation of HSCS from somatic and pluripotent stem cell sources. Blood. 2015;125:2641–2648. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-10-570234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ebihara Y, Ma F, Tsuji K. Generation of red blood cells from human embryonic/induced pluripotent stem cells for blood transfusion. Int J Hematol. 2012;95:610–616. doi: 10.1007/s12185-012-1107-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Orlic D, Kajstura J, Chimenti S, Jakoniuk I, Anderson SM, Li B, Pickel J, McKay R, Nadal-Ginard B, Bodine DM, Leri A, Anversa P. Bone marrow cells regenerate infarcted myocardium. Nature. 2001;410:701–705. doi: 10.1038/35070587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Porada CD, Atala AJ, Almeida-Porada G. The hematopoietic system in the context of regenerative medicine. Methods. 2016;99:44–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2015.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wagers AJ, Weissman IL. Plasticity of adult stem cells. Cell. 2004;116:639–648. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00208-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Blau HM, Brazelton TR, Weimann JM. The evolving concept of a stem cell: entity or function? Cell. 2001;105:829–841. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00409-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Balsam LB, Wagers AJ, Christensen JL, Kofidis T, Weissman IL, Robbins RC. Haematopoietic stem cells adopt mature haematopoietic fates in ischaemic myocardium. Nature. 2004;428:668–673. doi: 10.1038/nature02460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nygren JM, Jovinge S, Breitbach M, Sawen P, Roll W, Hescheler J, Taneera J, Fleischmann BK, Jacobsen SE. Bone marrow-derived hematopoietic cells generate cardiomyocytes at a low frequency through cell fusion, but not transdifferentiation. Nat Med. 2004;10:494–501. doi: 10.1038/nm1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Behbahan IS, Keating A, Gale RP. Bone marrow therapies for chronic heart disease. Stem Cells. 2015;33:3212–3227. doi: 10.1002/stem.2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Frantz S, Vallabhapurapu D, Tillmanns J, Brousos N, Wagner H, Henig K, Ertl G, Muller AM, Bauersachs J. Impact of different bone marrow cell preparations on left ventricular remodelling after experimental myocardial infarction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337:816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Genovese P, Schiroli G, Escobar G, Di Tomaso T, Firrito C, Calabria A, Moi D, Mazzieri R, Bonini C, Holmes MC, Gregory PD, Van der Burg M, Gentner B, Montini E, Lombardo A, Naldini L. Targeted genome editing in human repopulating haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2014;510:235–240. doi: 10.1038/nature13420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mandal PK, Ferreira LM, Collins R, Meissner TB, Boutwell CL, Friesen M, Vrbanac V, Garrison BS, Stortchevoi A, Bryder D, Musunuru K, Brand H, Tager AM, Allen TM, Talkowski ME, Rossi DJ, Cowan CA. Efficient ablation of genes in human hematopoietic stem and effector cells using CRISPR/Cas9. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:643–652. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Niu Y, Shen B, Cui Y, Chen Y, Wang J, Wang L, Kang Y, Zhao X, Si W, Li W, Xiang AP, Zhou J, Guo X, Bi Y, Si C, Hu B, Dong G, Wang H, Zhou Z, Li T, Tan T, Pu X, Wang F, Ji S, Zhou Q, Huang X, Ji W, Sha J. Generation of gene-modified cynomolgus monkey via Cas9/RNA-mediated gene targeting in one-cell embryos. Cell. 2014;156:836–843. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liang P, Xu Y, Zhang X, Ding C, Huang R, Zhang Z, Lv J, Xie X, Chen Y, Li Y, Sun Y, Bai Y, Songyang Z, Ma W, Zhou C, Huang J. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing in human tripronuclear zygotes. Protein Cell. 2015;6:363–372. doi: 10.1007/s13238-015-0153-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tebas P, Stein D, Tang WW, Frank I, Wang SQ, Lee G, Spratt SK, Surosky RT, Giedlin MA, Nichol G, Holmes MC, Gregory PD, Ando DG, Kalos M, Collman RG, Binder-Scholl G, Plesa G, Hwang WT, Levine BL, June CH. Gene editing of CCR5 in autologous CD4 T cells of persons infected with HIV. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:901–910. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1300662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sharma R, Anguela XM, Doyon Y, Wechsler T, DeKelver RC, Sproul S, Paschon DE, Miller JC, Davidson RJ, Shivak D, Zhou S, Rieders J, Gregory PD, Holmes MC, Rebar EJ, High KA. In vivo genome editing of the albumin locus as a platform for protein replacement therapy. Blood. 2015;126:1777–1784. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-12-615492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Glaser A, McColl B, Vadolas J. The therapeutic potential of genome editing for beta-thalassemia. F1000Res. 2015;4 doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7087.1. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7087.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ott de Bruin LM, Volpi S, Musunuru K. Novel genome-editing tools to model and correct primary immunodeficiencies. Front Immunol. 2015;6:250. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kleinstiver BP, Pattanayak V, Prew MS, Tsai SQ, Nguyen NT, Zheng Z, Joung JK. High-fidelity CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases with no detectable genome-wide off-target effects. Nature. 2016;529:490–495. doi: 10.1038/nature16526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]