Abstract

Latino/a youth are at risk for symptoms of depression and cigarette smoking but this risk varies by acculturation and gender. To understand why some youth are at greater risk than others, we identified profiles of diverse community experiences (perceived discrimination, bullying victimization, social support, perceived school safety) and examined associations between profiles of community experience and depressive symptoms, cigarette smoking, acculturation, and gender. Data came from Project Red (Reteniendo y Entendiendo Diversidad para Salud), a school-based longitudinal study of acculturation among 1919 Latino/a adolescents (52% female; 84% 14 years old; 87% U.S. born). Latent profile analysis (LPA) revealed four distinct profiles of community experience which varied by gender and acculturation. Boys were overrepresented in profile groups with high perceived discrimination, some bullying, and lack of positive experiences, while girls were overrepresented in groups with high bullying victimization in the absence and presence of other community experiences. Youth low on both U.S. and Latino/a cultural orientation described high perceived discrimination and lacked positive experiences, and were predominantly male. Profiles characterized by high perceived discrimination and/or high bullying victimization in the absence of positive experiences had higher levels of depressive symptoms and higher risk of smoking, relative to the other groups. Findings suggest that acculturation comes with diverse community experiences that vary by gender and relate to smoking and depression risk. Results from this research can inform the development of tailored intervention and prevention strategies to reduce depression and/or smoking for Latino/a youth at risk for depression and/or smoking.

Keywords: Latino/a youth, smoking, depression, gender, school environment, perceived discrimination

Depressive symptomatology is prevalent among U.S. adolescents. Recent national estimates suggest that about 30% of youth in the U.S. have experienced a past-month episode of sadness (CDC, 2014). Symptoms of depression are particularly common in youth who smoke cigarettes (Nezami et al., 2005), and cigarette smoking is one of the leading causes of preventable death in the United States (U.S.) (USDHHS, 2014). Reasons for why symptoms of depression and smoking co-occur are not fully understood. One line of research suggests that individuals use cigarettes to self-medicate their depressive symptoms (e.g., Breslau, Peterson, Schultz, Chilcoat, & Andreski, 1998), while other studies indicate the opposite, that nicotine leads to depressive symptoms by changing smokers’ brain chemistry (e.g., Quattrocki, Baird, & Yurgelun-Todd, 2000). Still others have negated a causal relationship between smoking and depression, proposing that depression and smoking are simply influenced by common factors such as stress (Kendler et al., 1993). Whatever the reason for the association between depression and smoking, it is important to understand factors that contribute to the depression and smoking risk of Latina/o youth. Latina/o youth belong to one of the largest, youngest, and fastest growing ethnic minority groups in the U.S. (Fry & Passel, 2009; Ennis, Ríos-Vargas, & Albert, 2011) and they are at high risk for depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking (CDC, 2014).

Although many U.S. adolescents smoke cigarettes and experience symptoms of depression, national surveys indicate higher rates of depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking among Latino/a youth compared to White and Black youth (CDC, 2014; Johnson et al., 2015). According to national estimates about 37% of Latina/o youth report a past-month episode of sadness and 45% report a lifetime history with cigarette smoking (CDC, 2014). While Latino boys report higher prevalence of cigarette smoking than girls, girls report more depressive symptoms than boys (CDC, 2014). Symptoms of depression and cigarette smoking among Latina/o youth also vary by acculturation (Lorenzo-Blanco, Unger, Ritt-Olson, Soto, & Baezconde-Garbanati, 2011), the process by which youth can experience cultural, social, behavioral, and psychological changes due to continuous contact with their new receiving U.S. culture (Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, & Szapocnik, 2010).

Symptoms of depression and cigarette smoking can also relate with experiences that unfold in the community such as perceived discrimination (Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2011), bullying victimization (Forster et al., 2013), social support (Gonzalez, Stein, Kiang, & Curpito, 2014), and perceived school climate (Maurizi, Ceballo, Epstein-Ngo, Cortina, 2013). These community experiences can further vary by gender (Foster et al., 2013; Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2011) and acculturation (Cupito, Stein, Gonzalez, 2014; Forster et al., 2013; Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2011). However, the majority of past studies have paid little attention to diverse profiles in community experiences among Latina/o youth. Understanding the diverse nature of community experiences among Latina/os is important because not all Latina/o youth experience perceived discrimination and bullying victimization to the same degree and not all Latino/a youth have access to social support and a positive school climate (Foster et al., 2013; Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2011). To better understand the diverse range of community experiences among Latina/o youth, the current study employed a person-centered research approach and examined how perceived discrimination, bullying victimization, social support and perceived school safety clustered together in the lives of Latina/o youth. It further investigated how diverse clusters of experiences varied by acculturation, gender, depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking.

Latino/a Youth Acculturation, Depressive Symptoms and Cigarette Smoking

Acculturation is a bidimensional process by which Latino/a youth acquire aspects of the dominant receiving U.S. culture while also selectively learning or maintaining aspects of their Latino/a heritage culture (Schwartz et al., 2010). Each of these dimensions (i.e., receiving culture and Latino/a heritage culture) consists of three interrelated but separate domains including cultural practices (e.g., speaking English/Spanish, enjoying English/Spanish language media), cultural values (e.g., individualistic and collectivistic values), and cultural identifications (e.g., identifying as U.S. American and/or Latino/a; Schwartz et al 2010). Thus, acculturation is a bidimensional (U.S. and Latino/a cultural elements) and multidomain (practices, values, identifications) process. Latino/a youth may follow some aspects of Latino/a and U.S. culture but not others, creating much diversity within this group. For example, some Latino/a youth may speak English and identify as American but also adhere strongly to Latino/a cultural values, while other youth may speak English and identify as Latino/a and strongly endorse individualistic values, while again other youth may speak English and Spanish, identify as both American and Latino but strongly identify with individualistic values.

Acquisition of and adherence to U.S. cultural elements (i.e., U.S. practices, values, identification) might relate with elevated risk for depression and smoking, whereas retention/acquisition of Latino/a cultural elements (i.e., Latino/a practices, values, and identification) might be associated with lower risk (De La Rosa, 2002). Evidence further indicates that the associations of acculturation with symptoms of depression and smoking are stronger for Latina/o girls than boys (e.g., Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2011).

Some scholars suggest that it is not U.S. or Latino/a culture acquisition/retention per se that leads to higher or lower depression and smoking risk but the experiences that can accompany acculturation (Schwartz et al., 2010) such as perceived discrimination (Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2011), bullying victimization (Foster et al., 2013), social support (Rivera, 2007), and perceptions of a positive school climate (Cupito et al., 2014). Similarly, scholars propose that it is not gender per se that leads to higher or lower depression and smoking risk but the experiences that come with being female (e.g., more bullying victimization compared to boys) or male (e.g., more perceived discrimination compared to girls) (Cole, 2009).

Community Experiences

Perceived Discrimination

One common experience that takes place in the community (e.g., schools, neighborhoods) is perceived discrimination, conceptualized as daily experiences of perceived unfair, differential treatment (Kam, Cleveland, & Hecht, 2010). Over time, perceived discrimination can influence mental health and substance use through stress proliferation (Ong, Fuller-Rowell, & Burrow, 2009). Studies have linked U.S. culture acquisition/retention with higher levels and Latino/a culture acquisition/retention with lower levels of perceived discrimination among Latino/a youth (Kam et al., 2010; Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2011). Moreover, perceived discrimination is associated with higher depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking among Latino/a youth and it is possible that perceived discrimination partly explains the associations of acculturation with symptoms of depression and cigarette smoking among Latino/a youth. Additionally, experiences of perceived discrimination vary by gender with Latino/a boys reporting higher perceived discrimination than girls (Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2011).

Bullying Victimization

Latino/a youth can also experience bullying victimization in school (CDC, 2014; Forster et al., 2013). Bullying victimization is aggression that is intentional, repeated, and characterized by an imbalance of power between the bullying perpetrator and the bullying target (e.g., Romero, Wiggs, Valencia, & Bauman, 2013). Bullying victimization can be direct and overt (i.e., physical aggression such as pushing, hitting, shoving) or more indirect and relational (e.g., spreading rumors or telling lies about other students to harm their reputation) (e.g., Romero et al., 2013). Among Latino/a youth, bullying has been associated with more depressive symptoms (Forster et al., 2013), suicide attempts (Romero et al., 2013), and cigarette use (Forster et al., 2013). Moreover, Forster and colleagues (2013) showed higher prevalence of bullying victimization among Latina girls than boys, indicating that bullying victimization might be an especially relevant risk factor for girls. Evidence also indicates a positive association between bullying victimization and with acculturative stress (Forster et al., 2013), highlighting the relevance of school-based peer bullying victimization in research on acculturation, depressive symptoms, and cigarette smoking.

Positive School Climate

Youth spend a great deal of time in their schools and researchers have documented the protective role of a positive school climate on the well-being of Latino/a youth (e.g., Maurizi et al., 2013). Although conceptualizations of school climate range from more affective (e.g. sense of school belonging and school connectedness) to more contextual (e.g., perceived safety and presence of gangs) to more interpersonal (e.g., teacher-student relationship and student-peer relationships) (Prado et al., 2009), scholars agree that a positive school environment promotes healthy development. Studies have linked positive school climate with better academic outcomes (Cupito et al., 2014), lower symptoms of anxiety and depression (Maurizi et al., 2013), and lower substance use (Prado et al., 2009). Moreover, acculturation (i.e., Latino/a cultural values) relate with higher school belonging (Cupito et al., 2014), indicating that students’ school climate experiences vary by acculturation.

Social Support

Supportive relationships with family, peers, and non-parental adults can also promote Latino/a youth well-being (Demaray & Malecki, 2002; Gonzalez et al., 2014; Lorenzo-Blanco, Unger, Baezconde-Garbanati, Ritt-Olson, & Soto, 2012). Social support can reduce the negative impact of stressful experiences on mental health problems (Aneshensel & Frerichs, 1982) and thereby protect Latino/a youth from the negative consequences of perceived discrimination and bullying victimization. Moreover, as Latino/as adopt U.S. cultural practices (e.g., speak English), they report lower social support (Rivera, 2007), possibly explaining the association of U.S. acculturation with smoking and depression risk.

Towards a Holistic Understanding of Community Experience

Studies have documented the significant roles played by perceived discrimination, bullying victimization, school climate, and social support on Latina/o youth depression and smoking risk. Although this knowledge is important, it is also fragmented because most studies have investigated the influence of one or possibly two community experiences on Latina/o youth depression and smoking risk, providing a limited understanding of the lived reality of Latina/o youth (Magnusson, 1998; Magnusson & Stattin, 1998). In real life, experiences of perceived discrimination, bullying victimization, perceived school safety, and social support can co-occur, interact, and combine to influence symptoms of depression and cigarette smoking (Magnusson & Stattin, 1998). Thus, an important next step is for research to take a holistic understanding of community experiences, and investigate how profiles of experience influence Latina/o youth smoking and depression risk.

Derived from holistic interactionism, which posits that individuals function within a structure of social, economic, and cultural factors (Magnusson & Stattin, 1998), person-centered approaches allow for the identification of diverse profiles of community experience and for investigating how profiles of community experience vary by gender, acculturation, symptoms of depression and cigarette smoking. Because in person-centered methods the unit of analysis is the individual’s lived experience as an organized whole (Magnusson, 1998), these approaches can better reflect the lived reality of Latina/o youth and provide a more multifaceted understanding of how community experiences come together in everyday life to create diverse risk profiles for depressive symptoms and smoking. Understanding diversity in profiles of community experience is important because Latino/a youth represent a diverse group of individuals with different life experiences, socio-political histories, and socio-cultural backgrounds (Aguilar-Gaxiola, Kramer, Resendez, & Magaña, 2008), possibly predisposing them to some but not all community experiences. Moreover, distinct profiles of community experiences may put some but not all youth at risk for depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking.

Although few studies have employed person-centered approaches to identify profiles of community experiences with Mexican American youth, Zeiders, Roosa, Knight, and Gonzalez (2013) used a person-centered approach and identified three distinct risk profiles based on Mexican American youth’s reports of risk factors, including maternal depression, economic hardship, parent-child conflict, peer conflict, discrimination, and language hassles. Risk profiles varied by socio-demographic variables and mental health disorder symptomatology. Similarly, in research with Latina/o adults, Lorenzo-Blanco and Cortina (2013) employed a person-centered approach and identified six distinct profiles of risk and protective acculturation-related experiences including everyday discrimination, family conflict, familismo, and family cohesion. Profiles of acculturation-related experiences varied by gender, acculturation, nativity, Latino/a ethnicity, major depressive disorder, and cigarette smoking. Similar to the study by Zeiders and colleagues (2013), Lorenzo-Blanco and Cortina (2013) reported that the majority of their sample were characterized by a low risk profile (low discrimination, low family conflict, high familismo, high family cohesion in Lorenzo-Blanco and Cortina, 2013; low maternal depression, low economic hardship, low parent-child conflict, low peer conflict, low discrimination, and low language hassles in Zeiders et al., 2013) but that various, smaller and distinct profile groups emerged that ranged from moderate to high risk. Both of these studies highlight the utility of person-centered approaches for identifying Latina/o youth at low and high risk for depression and smoking risk and for understanding diversity in community experiences among Latina/o youth.

The present study used longitudinal data with a sample of Latina/o youth to identify profiles of risk and protective experiences that often unfold in the community (i.e., perceived discrimination, bullying victimization, perceived school safety, and social support). We also compared profile groups on socio-cultural and demographic characteristics such as acculturation, gender, nativity, and age. Moreover, we investigated how profiles of community experience related with symptoms of depression and cigarette smoking, thereby providing insights into groups of adolescents at low or high risk for smoking and depressive symptoms.

Based on work with Mexican-American youth and Latina/o adults reviewed above, we expected to find groups with distinct constellations of community experiences and for these groups to vary by socio-demographic characteristics, symptoms of depression and cigarette smoking. Although we could not hypothesize about the number of profiles or specific patterns that would emerge, we expected to find distinct profile groups that differed regarding experiences of perceived discrimination, bullying victimization, social support, and perceived school safety. Moreover and based on prior work using person-centered approaches with Latina/os, we expected the largest profile group to be characterized by low levels of risk (perceived discrimination and bullying victimization) and high levels of protective (high perceived school safety and high social support) factors. Based on variable-centered research reviewed above, we expected profile groups characterized by high perceived discrimination (in the presence and absence of other experiences) to contain proportionately more Latino/a boys than girls. We further hypothesized that profile groups describing frequent bullying victimization (in the presence and absence of other experiences) to contain proportionately more girls than boys. In addition, we expected profile groups to differ on depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking. Specifically, we expected groups with high perceived discrimination and/or high bullying victimization to be at higher risk for depression and smoking compared to groups lacking these experiences. We also expected groups with high perceived school safety and/or high social support to endorse lower depressive symptoms and smoking compared to groups lacking these experiences.

Method

Participants

Participants included 1919 students who participated in Project RED (Retiendo y Entendiendo Diversidad para Salud) (Unger et al., 2009), a school-based longitudinal study of acculturation and substance use among Hispanic adolescents from Southern California. Fifty-two percent of the students were female, and 84% of the students were 14 years old. All students self-identified as Latino/a or Hispanic, and 87% of the students were born in the United States, with 86% of all students having either a foreign-born parent, grandparent or great-grandparent. Over half of the students (54.8%) reported speaking “English and another language equally” at home, 16.3% of the students reported “speaking mostly English” at home, 12.6% reported “speaking mostly another language ” at home, 11.7% reported speaking only English at home, and 4.6% reported speaking only Spanish at home. Similarly, 35% of the students reported speaking “mostly English” with their friends, 33.2% reported speaking “only English” with their friends, 29% reported speaking “English and another language equally” with their friends, 1.8% reported speaking mostly and 1% speaking only English with their friends.

Data Source and Procedure

Adolescents were enrolled in the study when they were in 9th-grade, attending seven high schools in the Los Angeles area. Schools were invited to participate if they contained at least 70% Hispanic students, as indicated by data from the California Board of Education. Sampling included an emphasis on schools with a wide range of socioeconomic characteristics. The median annual household incomes in the ZIP codes served by the schools ranged from $29,000 to $73,000, according to 2000 census data.

The 9th grade survey (Year 1) was administered in the Fall of 2005, the 10th grade survey (Year 2) in the Fall of 2006, and the and 11th grade survey (Year 3) in the Fall of 2007. In 2005, all 9th –graders (regardless of their race or ethnicity) in selected schools (n=3218) were invited to participate in the survey. Of those, 75% (n=2420) provided parental consent and student assent. Of the 2420 students who provided consent and assent, 2222 (92%) completed the survey in 9th grade. Of the 2222 students who completed the 9th grade survey, 1773 (80%) also completed surveys in 10th and 11th grade with 182 (8%) students completing a survey in 10th grade but not in 11th grade, 50 students (2%) completing a survey in 11th grade but not in 10th grade, and 217 (10%) students were lost to attrition before the 10th grade survey. For the current study, we used data from Years 1, 2, and 3 and excluded students who did not self-identify as either Hispanic, Latino or Latina, Mexican, Mexican-American, Chicano or Chicana, Central American, South American, Mestizo, La Raza, or Spanish.

On the day of the survey, data collectors read the survey aloud during one class period in order to help students with low literacy skills. Surveys were available in English and Spanish and 99.2% of the students completed the survey in English. A more detailed description of data collection can be found elsewhere (Unger, Ritt-Olson, Soto, & Baezconde-Garbanati, 2009).

Measures

Perceived Discrimination

Perceived discrimination was assessed with ten items (Guyll, Matthews, & Bromberger, 2001). A sample item included “You are treated with less respect than other people.” At baseline, adolescents indicated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (Never) to 4 (Often) their perceived experiences with ethnic discrimination. The Cronbach’s α was .87. Because this scale can apply to various types of discrimination (e.g., based on race/ethnicity, gender, age, sexual orientation, physical handicaps, etc.), the scale was preceded by the following text: “Sometimes people feel that they are treated differently because of their ethnic or cultural background. How do people treat you?”

Bullying Victimization

We assessed bullying victimizations in schools with five items taken from the California Healthy Kids Survey (California Department of Education, 2006). At time 1, students on verbal and physical bullying experiences. A sample item included “During the past 12 months, how many times have mean rumors or lies been spread about you?” Response options ranged from 1 (0 Times) to 4 (4 or more times). The Cronbach’s α was .65.

Perceived School Safety

We employed a measure of perceived school safety to assess student’s perception of positive school climate and used six items from the School Violence in Context study (Benbenishty & Astor, 2005). A sample item included “My school is a safe and protected place.” Adolescents indicated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 4 (Strongly Agree) how much they agreed with each statement (Cronbach’s α = .80).

Social Support

We assessed perceived social support with 12 items from the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, and Farleys, 1988). This measure asks youth to indicate the degree they feel support by friends, family, and other specials persons. Sample items included “I have a special person who is a real source of support,” “My friends really try to help me,” and “I can talk about my problems with my family.” At time 1, adolescents rated their agreement with each statement on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 4 (Strongly agree). The Cronbach’s α was .88.

Depressive Symptoms

Adolescents’ depressive symptoms were assessed with the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977), which consists of 20 items and has been validated with Latino/a youth (Crockett et al., 2005). At time points 1, 2, and 3, adolescents indicated the frequency with which they had experienced symptoms of depression in the past week. The Cronbach’s α were .88 across time points.

Lifetime Cigarette Smoking

We used a dichotomous measure to assess adolescent lifetime smoking. Adolescents responded to the following question; “Have you ever tried cigarette smoking, even one or two puffs?” Response choices included 0 (No) and 1 (Yes).

Past-30-Day-Smoking

One question assessed adolescents’ past-30-day cigarette use; “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke cigarettes?” Responses were rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (0 days) to 7 (All 30 days).” We dichotomized response options to 0 days versus all other days (0 = no past-30-day smoking, 1 = past-30-day smoking) due to skewed distributions.

Acculturation

We used the short form of the Revised Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans (ARSMA-II; Cuellar et al., 1995). Seven items tap into U.S. orientation and five assess Latino/a orientation. At time 1, adolescents indicated on a scale ranging from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Almost always/Extremely often), how much they engaged in or enjoyed certain activities. Cronbach’s α was .77 for the U.S. and .88 for the Latino/a Orientation scales.

Demographic Characteristics

Age, gender, and nativity were self-reported.

Data Analysis

Missing data were imputed with the SAS Proc MI (SAS Institute, 2013) which uses the estimation maximization algorithm to replace missing values with iterative maximum likelihood estimation (Schafer, 1997). We conducted descriptive analyses for all study variables with SPSS version 21.0 (SPSS IBM, 2012) and tested for gender differences in all study variables. T-tests were used for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. We used latent profile analysis (LPA) with the mixture module in Mplus Version 7.1 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2012) to identify profile groups based on community experiences. We used multinomial logistic regression in Mplus Version 7.1 to compare profile groups by socio-demographic characteristics and to examine the associations of group membership with our outcome variables.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 shows summary statistics for all study variables for the full sample (N = 1919) and by gender (male, female). As shown, boys reported higher levels of perceived discrimination, perceived school safety, and social support. Boys were also more likely to report lifetime and past-30 day smoking compared to girls. Girls, on the other hand, reported higher levels of bullying victimization and depressive symptomatology.

Table 1.

Summary Statistics by Gender for Independent and Dependent Variables

| Full Sample (N=1919) |

Female (n=1004) |

Male (n=915) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Range | N (%) or M (SD) | N (%) or M (SD) | N (%) or M (SD) | P |

| Perceived Discrimination (T1) | 9 – 54 | 16.36 (7.73) | 15.43 (7.06) | 17.22 (8.21) | ** |

| Bullying Victimization (T1) | 5 – 15 | 6.35 (1.19) | 6.58 (2.06) | 6.13 (1.71) | * |

| Perceived School Safety (T1) | 7 – 28 | 25.21 (3.66) | 24.92 (3.95) | 25.49 (3.33) | ** |

| Social Support (T1) | 3 – 12 | 10.88 (1.64) | 10.82 (1.75) | 10.93 (1.53) | ** |

| Depressive Symptoms | |||||

| Time 1 | 20 – 80 | 1.77 (.54) | 1.90 (.58) | 1.63 (.45) | ** |

| Time 2 | 20 – 80 | 1.78 (.54) | 1.92 (.56) | 1.64 (.49) | ** |

| Time 3 | 20 – 80 | 1.76 (.53) | 1.87 (.53) | 1.63 (.49) | ** |

| Lifetime Smoking | |||||

| Time 1 | – | 532 (27.7) | 265 (26.4) | 267 (29.2) | |

| Time 2 | – | 649 (33.8) | 290 (28.9) | 359 (39.2) | ** |

| Time 3 | – | 791 (41.2) | 361 (36.0) | 430 (47.0) | ** |

| Past-30 Day Smoking | |||||

| Time 1 | – | 149 (7.8) | 76 (7.6) | 73 (8.0) | |

| Time 2 | – | 214 (11.2) | 96 (9.6) | 118 (12.9) | * |

| Time 3 | – | 324 (16.9) | 149 (14.8) | 175 (19.1) | * |

Note.

p <.001;

p < .05

Latent Profiles of Community Experience: Latent Profile Analysis

We identified profile groups based on community experiences (i.e., perceived discrimination, bullying victimization, perceived school safety, and social support) by comparing models with one through six profile solutions. We employed six methods to identify the best fitting model: 1) the Akaiken Information Criterion (AIC); 2) Bayesian information criterion (BIC); 3) sample size-adjusted BIC (ssBIC); 4) entropy value; 4) Lo-Mendell-Rubin Likelihood Ratio test; 5) Bootstrapped Likelihood Ratio test (BLRT); 6) the sample size in each profile group for meaningful analyses; and 7) the meaningfulness of each profile solution based on extant scholarship.

As shown in Table 2 and based on above criteria, plausible solutions for the current study included the 2, 3 and 4 profile solutions. We decided against the 2 profile solution because the AIC, BIC, ssBIC, and entropy suggest that the 3 profile solutions was preferable. Although the LMR was only marginally significant, the BLRT (Table 2 under 3 profile solution) suggests that the 3 profile solution was preferable over the 2 profile solution. Moreover, when comparing individual profiles in terms of meaningful group differences between the 2 and 3 profile solutions, we observed that additional and meaningful group differences emerged in the 3 profile solution that were not captured in the 2 profile solution.

Table 2.

LPA Model Fit Indices and Sample Sizes for 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 Profile Solutions

| Variable | 1-Profile Solution | 2-Profile Solution | 3-Profile Solution | 4-Profile Solution | 5-Profile Solution | 6-Profile Solution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIC | 12045.47 | 11418.39 | 11145.422 | 10970.03 | 10870.637 | 10792.52 |

| BIC | 12089.94 | 11490.66 | 11245.494 | 11097.90 | 11026.304 | 10975.98 |

| Sample Size Ajusted BIC | 12064.53 | 11449.36 | 11188.308 | 11024.83 | 10937.348 | 10871.14 |

| Entropy | NA | 0.774 | 0.793 | 0.816 | 0.749 | 0.769 |

| Lo-Mendell Rubin LRT | NA | <.001 | 0.059 | 0.008 | 0.479 | 0.108 |

| Bootstrapped Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT) | NA | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Profile Group Sample Size | 1919 | 332/1587 | 93/340/1486 | 45/173/307/1394 | 41/97/300/344/1137 | 32/37/115/249/355/1131 |

Note. AIC Akaiken Information Criterion; BIC Bayesian Information Criterion; LRT Likelihood Ratio Test

We underwent the same evaluation process when comparing profile groups 3 and 4 and decided to maintain the 4 profile solution for the following reasons: 1) The AIC, BIC, ssBIC suggested the 4 profile solution to be preferred over the 3 profile solution; 2) Entropy was also higher for the 4 profile solution compared to the 3 profile solution, indicating that the 4 profile solution was preferable; and 3) LMR and BLRT also indicate that a 4 profile solution was preferable. Moreover, in comparing meaningful differences in profile groups, we observed that the 4 profile solution provided meaningful information about diverse community experiences that the 3 profile group solution did not capture.

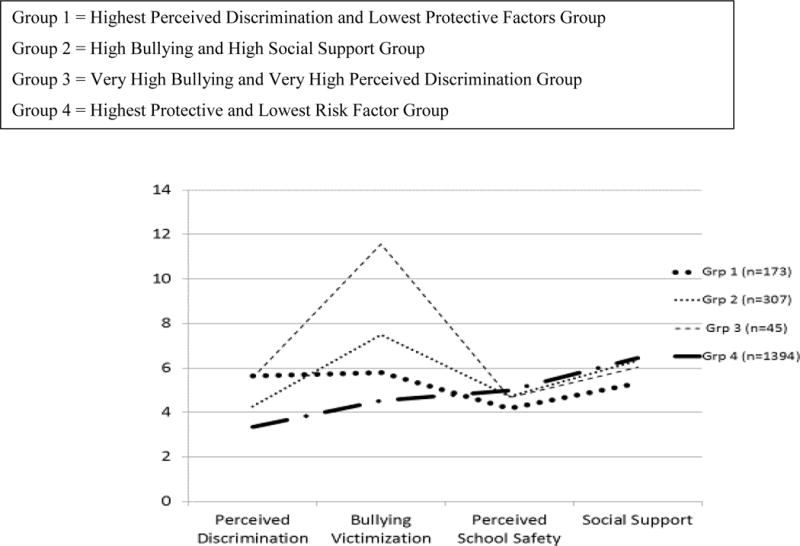

Figure 1 shows the standardized means on the scored community experiences and the sample size (in the legend) for each of the four profile groups. Group 1 (n = 173) reported the highest perceived discrimination, the lowest perceived school safety and social support, and some bullying victimization. As such, we named this group the Highest Perceived Discrimination and Lowest Protective Factors Group. Group 2 (n = 307) individuals, on the other hand, were characterized by high bullying victimization and high social support in the presence of moderate perceived discrimination and some perceived school safety. We named this group the High Bullying and High Social Support Group. Group 3 (n = 45), the smallest group, detailed both very high bullying victimization and very high perceived discrimination in the presence of some perceived school safety and some social support. We named this group the Very High Bullying and Very High Perceived Discrimination Group. Group 4 (n = 1394), the largest group, was characterized by the lowest levels of perceived discrimination, the lowest bullying victimization, and the highest levels of perceived school safety and social support. Thus, we named this group the Highest Protective and Lowest Risk Factor Group. Therefore, we expected Group 4 to have the lowest risk for symptoms of depression and cigarette smoking and as such, we used Group 4 as the reference category for the remainder of the analyses.

Fig 1.

Latent profiles of standardized mean community experiences for each profile group.

Demographics of Profile Groups: Multinomial Logistic Regression Analyses

With multinomial logistic regressions, we found significant associations between profile group membership and gender, χ2(3) = 170,44, p < .001; U.S. orientation, χ2(3) = 77.14, p < .001; and Latino/a orientation, χ2 (3) = 27.63, p < .001.

Table 3 presents demographic and socio-cultural statistics for each of the six profile groups and the full sample. A review of profiles allowed us to consider gender differences within and between profile groups, assessing differences in community experiences for boys and girls. Large gender differences emerged for all groups. The Highest Perceived Discrimination and Lowest Protective Factors Group stood out as the group with proportionately more males (87%) and fewer females (13%) compared to any of the other groups. The other three groups contained disproportionately more females than males.

Table 3.

Sample and Profile Group Demographic Characteristics at Baseline

| Full Sample (N = 1919) |

Group 1 (N = 173) |

Group 2 (N = 307) |

Group 3 (N = 45) |

Group 4 (N = 1394) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | N (%) or M (SD) | N (%) or M (SE) | N (%) or M (SE) | N (%) or M (SE) | N (%) or M (SE) | |

|

| ||||||

| Age | 3.01 (0.41) | 3.04 (0.03) | 3.01 (0.02) | 2.99 (0.06) | 3.00 (0.011) | χ2(3) = 1.57, ns |

| Gender | χ2(3) = 170.44, p<.001 | |||||

| Female | 1004 (52.3) | 22 (12.7) | 176 (57.3) | 27 (60.2) | 896 (64.3) | |

| Male | 915 (47.7) | 151 (87.3) | 131 (42.7) | 18 (39.8) | 498 (35.7) | |

| Nativity | χ2(3) = 1.37, ns | |||||

| Foreign born | 241 (12.6) | 18 (10.2) | 37 (12.1) | 7 (16.4) | 180 (12.9) | |

| U.S. born | 1678 (87.4) | 155 (89.8) | 270 (87.9) | 38 (83.6) | 1214 (87.1) | |

| U.S. Orientation | .64 (.15) | 0.55 (0.01) | 0.67 (0.01) | 0.65 (0.02) | 0.65 (0.00) | χ2(3) = 77.14, p<.001 |

| Latino/a Orientation | .43 (.21) | 0.36 (0.01) | 0.43 (0.01) | 0.45 (0.03) | 0.44 (0.01) | χ2(3) = 27.63, p<.001 |

In regard to U.S. and Latino/a orientation, all groups except the Highest Perceived Discrimination and Lowest Protective Factors Group reflected the full sample. However, individuals in the Highest Perceived Discrimination and Lowest Protective Factors Group scored lower on both U.S. and Latino/a orientation compared to any of the other groups. Therefore, according to Berry’s (2003) model of acculturation, adolescents in the Highest Perceived Discrimination and Lowest Protective Factors Group were more likely to be marginalized – reporting weak connections to both U.S. and Latino/a culture.

In sum, we identified four profile groups, each characterized by a unique combination of community experiences (i.e., perceived discrimination, bullying victimization, social support, and perceived school safety). We observed that profile groups differed as a function of gender, U.S. orientation, and Latina/o orientation. Youth facing the highest perceived discrimination and the lowest protective factors (the Highest Perceived Discrimination and Lowest Protective Factors Group) were disproportionately male and least oriented to both U.S. and Latino/a culture. Groups characterized by high or very high bullying victimization (in the presence of other experiences) were disproportionately female but did not differ by acculturation.

Depressive Symptoms and Cigarette Smoking by Profile Group: Multinomial Logistic Regression Analyses

Lastly, we used multinomial logistic regression analyses to examine the associations of profile groups with depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking by treating depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking as distal outcomes. Table 4 illustrates outcome data by profile group and the results of the overall regression analyses.

Table 4.

Symptoms of depression and cigarette smoking by profile group.

| Outcome | Group 1 (n = 173) | Group 2 (n=307) | Group 3 (n=45) | Group 4 (n = 1394) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Depressive Symptoms | M (SE) | M (SE) | M (SE) | M (SE) | χ2(3) | P | ||||

| Time 1 | 1.97 (.03) | 2.2 (.03) | 2.38 (.09) | 1.57 (.01) | 476.99 | <.001 | ||||

| Time 2 | 2.01 (.04) | 2.00 (.03) | 2.21 (.09) | 1.68 (.01) | 153.629 | <.001 | ||||

| Time 3 | 1.97 (.04) | 1.95 (.03) | 1.90 (.08) | 1.67 (.01) | 108.765 | <.001 | ||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Lifetime Smoking | N (%) | OR [95% CI] | N (%) | OR [95% CI] | N (%) | 95% CI | N (%) | 95% CI | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Time 1 | 87 (50) | 3.61 [2.24, 4.99] | 103 (33.5) | 1.18 [1.14, 2.50] | 22 (48.1) | 3.34 [1.22, 5.47] | 302 (21.7) | 1 [1,1] | 57.13 | <.001 |

| Time 2 | 98 (56.6) | 3.32 [1.99, 4.64] | 121 (39.4) | 1.65 [1.11, 2.19] | 20 (44.3) | 2.03 [0.74, 3.31] | 393 (28.2) | 1 [1,1] | 44.93 | <.001 |

| Time 3 | 102 (59.2) | 2.45 [1.53, 3.38] | 133 (43.3) | 1.29 [0.86, 1.72] | 24 (54.2) | 2.00 [0.73, 3.28] | 519 (37.2) | 1 [1,1] | 28.35 | <.001 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Past-30-Day Smoking | N (%) | OR [95% CI] | N (%) | OR [95% CI] | N (%) | 95% CI | N (%) | 95% CI | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Time 1 | 35 (20.3) | 4.57 [2.27, 6.87] | 21 (6.7) | 1.29 [0.33, 2.26] | 11 (25.1) | 6.00 [1.53,10.48] | 74 (5.3) | 1 [1,1] | 27.44 | <.001 |

| Time 2 | 44 (25.6) | 3.68 [1.99, 5.37] | 36 (11.8) | 1.44 [0.69, 2.18] | 6 (12.8) | 1.57 [0.09, 3.04] | 118 (8.5) | 1 [1,1] | 21.14 | <.001 |

| Time 3 | 56 (32.1) | 2.63 [1.59, 3.66] | 27 (8.9) | 0.54 [0.15, 0.94] | 14 (30.1) | 2.39 [0.72, 4.07] | 213 (15.3) | 1 [1,1] | 25.09 | <.001 |

Note. Group 4 served as reference group.

Symptoms of Depression

As shown in Table 4, we observed significant differences across profile group in reports of depressive symptoms across all three time points (Times 1 – 3). Specifically, at times 1 and 2, youth in the Highest Protective and Lowest Risk Factor Group reported the lowest levels of depressive symptoms, and youth in the Very High Bullying and Very High Perceived Discrimination Group reported the highest levels of symptoms of depression. At time 3, individuals in the Highest Protective and Lowest Risk Factor Group continued to report the lowest levels of depressive symptoms and no large differences emerged in depressive symptomatology between the remaining groups. These findings suggest that Latino/a youth’s depressive symptomatology may relate with their combined experiences of perceived discrimination, bullying victimization, social support, and perceived school safety. Specifically, youth who endorsed the least experiences with perceived discrimination and bullying and the greatest access to social support and a safe school environment, reported the lowest symptoms of depression, while youth who experienced high levels of bullying victimization and high levels of perceived discrimination in the presence of some positive experiences, reported the highest levels of depressive symptoms.

Lifetime and Past-30-Day Cigarette Smoking

Profile groups also differed on lifetime and past-30-day smoking (Table 4). Across time points (Times 1 – 3), youth in the Highest Perceived Discrimination and Lowest Protective Factor Group, youth in the High Bullying and High Social Support Group, and youth in the Very High Bullying and Very High Perceived Discrimination Group were more likely to have smoked cigarettes at some point in their lives compared to youth in the Highest Protective and Lowest Risk Factor Group. Moreover, across time points, youth in the Highest Perceived Discrimination and Lowest Protective Factors Group and youth in the Very High Bullying and Very High Perceived Discrimination Group were much more likely to report a lifetime history with smoking than youth in the High Bullying and High Social Support and Highest Protective and Lowest Risk Factor Groups.

A similar pattern of results emerged for past-30-day smoking. At times 1, 2, and 3, youth in the Highest Perceived Discrimination and Lowest Protective Factors Group and youth in the Very High Bullying and Very High Perceived Discrimination Group were much more likely to report past-30-day smoking than youth in the High Bullying and High Social Support Group and youth in the Highest Protective and Lowest Risk Factor Group. Moreover, compared to youth in the Highest Protective and Lowest Risk Factor Group, youth in the remaining groups (i.e., the Highest Perceived Discrimination and Lowest Protective Factors Group, the High Bullying and High Social Support Group, and the Very High Bullying and Very High Perceived Discrimination Group) were more likely to have smoked cigarettes at times 1 and 2. These results suggest that youth’s lifetime and past-30-day smoking relate with their combined experiences with perceived discrimination, bullying victimization, social support and a safe school environment. Generally, youth in the two groups with the highest or very high perceived discrimination and/or bullying in the absence of high protective factors (i.e., the Highest Perceived Discrimination and Lowest Protective Factors Group and the Very High Bullying and Very High Perceived Discrimination Group) were at higher risk for lifetime and past-30-day smoking than youth in groups with access to high social support and/or high perceived school safety in the presence or absence of perceived discrimination and/or bullying (i.e., High Bullying and High Social Support Group and Highest Protective and Lowest Risk Factor Group).

Discussion

The current longitudinal study took a holistic, person-centered approach to investigate how multiple community experiences (i.e., perceived discrimination, bullying, perceived school safety, and social support) converged in the everyday lives of Latina/o youth. It further examined how resultant latent profiles varied by gender and acculturation and related with depressive symptoms and smoking. In everyday life, Latino/a youth can face a range of community experiences that can accompany acculturation, vary by gender, and impact youth depression and smoking risk. We build on previous variable-centered work (Cupito et al., 2014; Foster et al., 2013; Gonzalez et al., 2014; Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2011) and document how experiences of perceived discrimination, bullying victimization, perceived school safety, and social support combine and covary, resulting in distinct profiles of community experience. These profiles related with depressive symptoms and smoking, and varied by gender and acculturation.

Key Findings and Their Implications

Profiles of community experience

Latent profile analysis demonstrated diversity of community experiences among Latino/a youth. Our analyses revealed four distinct profiles of community experiences, which ranged from highest perceived discrimination and lowest positive factors, to high bullying and high social support, to very high bullying and high perceived discrimination, to very low risk factors and very high positive factors. These profile groups demonstrated that not all Latino/a youth experience perceived discrimination and bullying and not all Latino/a youth have access to social support and/or a perceived school safety.

As expected, the majority of youth belonged to the profile group characterized by low levels of risk and high levels of protective factors (i.e., Highest Protective and Lowest Risk Factor Group). This is consistent with prior person-centered research with Latina/o youth and adults in which researchers found that the majority of their youth and adult samples belonged to profile groups characterized by low risk and high protective factors (Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2013; Zeiders et al; 2013). However, subgroups of youth reported lacking a sense of school safety and/or social support while at the same time experiencing high perceived discrimination and/or high bullying victimization. Overall, latent profile analysis allowed for the identification of diverse lived community experiences among Latino/a youth and provided insights regarding profiles with higher or lower smoking and depression risk.

We also examined profile groups on their socio-cultural composition and observed that profile groups differed by gender and acculturation. As hypothesized and consistent with research that shows that Latino boys report more perceived discrimination than girls (Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2011), Latino boys were proportionately more likely to be in the group characterized by the highest perceived discrimination and lack of perceived school safety and social support (i.e., the Highest Perceived Discrimination and Lowest Protective Factors Group). This suggests that discrimination and lack of positive community experiences may be salient community experiences for some (but not all) Latino boys, and in particular, boys who endorse low engagement with both U.S. and Latina/o culture.

Individuals in the Highest Perceived Discrimination and Lowest Protective Factors Group appeared to be the least oriented to both U.S. and Latino/a culture, suggesting that individuals in this group may have disengaged or feel disconnected from their receiving U.S. and their Latino/a heritage culture. This is possibly due to their frequent experiences of discrimination and their lack of social support (Sam & Berry, 2003). In other words, youth in the Highest Perceived Discrimination and Lowest Protective Factors Group may have adopted the marginalization pattern of acculturation (Sam & Berry, 2003) in which youth do not participate in either their U.S. receiving or their Latino/a heritage culture, and as a result, they may feel disconnected and lack social support (Sam & Berry, 2003). Scholars propose that Latino/a youth may disengage from their U.S. receiving culture for reason of exclusion and discrimination (Sam & Berry, 2003) and our results supports this notion.

We also found that proportionately more girls than boys were in groups characterized by high or very high bullying victimization (i.e. the High Bullying and High Social Support Group and the Very High Bullying and Very High Perceived Discrimination Group), supporting research that indicates higher prevalence of bullying victimization among Latina girls than boys (Forster et al., 2013). This indicates that bullying victimization may be an especially salient risk factor for Latina girls (but some boys are subject to bullying victimization as well). Girls were also overrepresented in the groups characterized by high bullying, high social support, some positive experiences (i.e. High Bullying and High Social Support Group) and the lowest risk and highest protective factors (i.e., Highest Protective and Lowest Risk Factor Group), suggesting more diversity in community experiences among girls than boys. Reasons for more diverse community experiences among girls than boys are not clear but it is possible that gender socialization among Latina/o youth provides girls with a more diverse constellation of experiences (Hurtado, 2010; Romero, Edwards, Bauman, & Rittner, 2014). However, our findings raise interesting questions about why boys and girls may have different experiences and how these influence their well-being. Findings also highlight the need to incorporate a gendered lens when investigating profiles of experiences and youth well-being (Romero et al., 2014).

Interestingly, we did not observe systematic differences in acculturation between the three groups that contained proportionately more girls than boys (i.e., the High Bullying and High Social Support Group, the Very High Bullying and Very High Perceived Discrimination Group, and the Highest Protective and Lowest Risk Factor Group), indicating that diversity in profiles of community experiences between these three groups may not depend on Latina girls’ acculturation strategies but other socio-cultural characteristics and experiences such as SES, sexual orientation, body shape, and gender discrimination (e.g., Romero et al., 2014). Alternatively, it is possible that Latino boys have a more difficult time than Latina girls to fit into either U.S. or Latino culture, resulting in a profile of community experience characterized by high discrimination, lack of social support, lack of perceived school safety, and some bullying victimization. In the overall sample, boys reported lower levels of both U.S. cultural orientation compared to girls. Both of these reasons could be valid and could be explored further in future research. Overall and consistent with theories of intersectionality, these results highlight the need to consider how community experiences can differ for Latina/o youth who live at the intersection of different social categories and experiences such as gender and acculturation (Hurtado, 2010).

Depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking

About 41% of youth reported a lifetime history with cigarette smoking by the time they entered eleventh grade, and about 17% of eleventh graders had smoked cigarettes in the past 30 days. Consistent with prior work (CDC, 2014), Latino boys reported higher rates of lifetime and past-30 day smoking in tenth and eleventh grade, while girls endorsed higher levels of depressive symptoms than boys across grade levels. To better understand how profiles of community experience influence the smoking and depression risk of Latino/a youth, we examined how profile groups were associated with depressive symptoms and smoking.

Two profile groups stood out as having the highest or very high perceived discrimination and/or very high bullying while also lacking adequate social support and a perceived school safety (the Highest Perceived Discrimination and Lowest Protective Factors Group and the Very High Bullying and Very High Perceived Discrimination Group), and these profiles were associated with elevated smoking and depression risk. Specifically, youth in the Highest Perceived Discrimination and Lowest Protective Factors Group reported the highest prevalence of smoking, and youth in the Very High Bullying and Very High Perceived Discrimination Group showed the highest vulnerability for depressive symptoms. While the Highest Perceived Discrimination and Lowest Protective Factors Group contained disproportionately more boys than girls, the Very High Bullying and Very High Perceived Discrimination Group (group 3) contained disproportionately more girls than boys, and these patterns of results suggests that boys may be more likely than girls to use cigarettes when faced with difficult life situations while girls may be more likely than boys to experience depressive symptoms when surrounded by life situations with very high bullying and perceived discrimination in the absence of adequate social support/perceived school safety. These findings suggest that helping Latino/a boys and girls identify effective ways to cope with perceived discrimination and bullying could help protect them from depressive symptoms and smoking. Specifically, youth may benefit from learning primary control engagement strategies which involve direct coping with stressors and include problems solving, emotional expression, and emotional emulation (Edwards & Romero, 2008). Research with Latina/o youth indicates that control engagements strategies buffered the negative effects of perceived discrimination on Latina/o youth self-esteem (Edwards & Romero, 2008), suggesting that these coping strategies could also help youth cope with discrimination and bullying victimization in ways that it does not affect their depressive symptoms and smoking.

Helping Latino/a youth to identify and establish sources of social support could also benefit their smoking and depression risk. The High Bullying and High Social Support Group reported lower cigarette smoking and depressive symptoms than youth in the groups characterized by high perceived discrimination and/or bullying in the absence of high social support (i.e., Highest Perceived Discrimination and Lowest Protective Factors Group and Very High Bullying and Very High Perceived Discrimination Group). These results are consistent with the notion that social support can buffer against the negative impact of stressful life situations on mental health (Aneshensel and Frerichs, 1982).

Scholars propose that Latino/a youth who endorse both U.S. and Latino/a culture have better health than youth who endorse one culture over the other (Sam & Berry, 2013; Schwartz et al., 2010; Smokowski & Baccalao, 2009). The current study does not fully support this notion. Youth in groups who equally endorsed U.S. and Latino/a culture differed in regards to smoking and depressive symptoms. The Highest Protective and Lowest Risk Factor Group had significantly lower smoking and depression risk than the High Bullying and High Social Support Group and the Very High Bullying and the Very High Perceived Discrimination Group, suggesting that experiences other than endorsement of U.S. and Latino/a culture (i.e., perceived discrimination, bullying victimization, social support, and perceived school safety in the current study) influence Latino/a youth smoking and depression risk. These findings provide insights into potential and important areas for school- or community-based preventions and interventions that could target community experiences such as perceived discrimination, bullying victimization, social support, and perceived school safety.

Limitations

The present results should be interpreted in light of several important limitations. First, youth in the current study resided in Los Angeles which is a relatively large and well-established receiving community for Latino/a youth with many ethnic enclave neighborhoods. This may influence opportunities for experiencing discrimination, bullying victimization, social support and a sense of safety at school. As such, findings from this investigation may not reflect the lived reality of youth who live in and attend schools in new settlement communities (e.g., the Midwest and Deep South) that have less experience interacting with newcomers (Barrington, Messias, & Weber, 2012). Therefore, future studies should aim at replicating the current study with Latino/a youth in less established but growing settlement communities (Rodriguez, 2012) to investigate if similar profiles of community experiences emerge. Similarly, the majority of youth (84%) were U.S. born and findings from the current study may not reflect the experiences of foreign-born youth. Thus, future studies should collect data with foreign-born youth and investigate profiles of community experience with these youth. Moreover, youth in the current study were predominantly Mexican American and findings from the current study may not generalize to other Latino/a subgroups. Thus, future studies should replicate this study with Latino/a youth from Cuba, Puerto Rico, and other Latino/a subgroups.

Another limitation of the current study includes the measurement of bullying victimization which has an adequate but relatively low Cronbach’s alpha (0.65). Although we used items from previously established scales, we did not include the full scale in our study, possibly contributing to the low Cronbach’s alpha value (Field, 2012, page 709). Therefore, future studies should replicate the current study by using a complete measure of bullying victimization. Additionally, in the current study we were not able to distinguish between youth with high and low smoking frequency. Similarly, we were not able to distinguish between youth who smoke large versus small quantities of cigarettes. As such future studies should ask questions about the frequency of youth smoking as well as questions about the quantity of cigarettes smoked per day or month.

Moreover, in the current study we assessed positive school climate with six items that tapped into students’ perceived safety at school. Given that conceptualizations of school climate can taking many forms that range from more affective (e.g. sense of school belonging and school connectedness) to more contextual (e.g., perceived safety and presence of gangs) to more interpersonal (e.g., teacher-student relationship and student-peer relationships) (Prado et al., 2009), we recommend that future studies with Latina/o youth include more comprehensive measures of school climate and investigate if profiles of community experience similar to those in the current study emerge.

Lastly and given that data came from a school-based survey (that may or may not have included youth who suffer from severe depressive symptoms) and given that we did not include a measure of depressive symptom severity or a diagnostic tool for depression, we cannot speak to whether our results generalizes to youth with clinically significant symptom severity. Thus, future studies should aim at replicating our study with Latina/o youth who endorse severe depressive symptomatology and investigate if our results generalize to more clinical populations.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the present study advances our understanding of how community experiences come together to influence youth smoking and depression risk. With latent profile analysis we investigated the diverse ways in which experiences of discrimination, bullying, social support, and perceived school safety combined to create diversity among Latino/a youth. We also compared profile groups by smoking and depressive symptoms which illustrated diverse pathways to youth smoking and depressive symptoms. This knowledge can inform school- and community-based prevention and intervention. These efforts could target discrimination and bullying victimization reduction while creating safe school environment and opportunities for youth to obtain social support from others (e.g., peers, teachers). Additionally, these efforts could help Latino/a youth identify ways to cope with discrimination and bullying in schools.

Contributor Information

Elma I. Lorenzo-Blanco, Email: lorenzob@mailbox.sc.edu, Department of Psychology, University of South Carolina, 1512 Pendleton, Columbia, SC 29208, Phone: 803.777.808.

Jennifer B. Unger, Email: unger@usc.edu, Institute for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Research, USC, Keck School of Medicine, 2001 N Soto Street, MC 9239, Los Angeles, CA 90089-9239, Phone: 323.442.8234.

Assaf Oshri, Email: oshri@uga.edu, Department of Human Development & Family Science, The University of Georgia, 208 Family Science Center (House A), 403 Sanford Drive, Athens, GA 30602-2622, Phone: 706.542.4882.

Lourdes Baezconde-Garbanati, Email: baezcond@hsc.usc.edu, Preventive Medicine, Keck School of Medicine, USC, 2001 Soto St, Los Angeles, CA, 90033, Phone: 323. 442.7801.

Daniel Soto, Email: danielws@usc.edu, Institute for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Research, USC Keck School of Medicine, 2001 N Soto Street, MC 9239, Los Angeles CA 90089-9239, Phone: 323.442.8211.

References

- Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Kramer EJ, Resendez C, Magaña CG. The context of depression in latinos in the united states. In: Gullotta TP, editor. Depression in US Latinos: Assessment, treatment, and prevention. New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media; 2008. pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS, Frerichs RR. Stress, support, and depression: A longitudinal causal model. Journal of Community Psychology. 1982;10:363–376. [Google Scholar]

- Barrington C, Messias DKH, Weber L. Implications of racial and ethnic relations for health and well-being in new Latino communities: A case study of West Columbia, South Carolina. Latino Studies. 2012;10:155–178. doi: 10.1057/lst.2012.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benbenishty R, Astor RA. School violence in context: Culture, Neighborhood, Family, School, and Gender. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 167–168. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Peterson EL, Schultz LR, Chilcoat HD, Andreski P. Major depression and stages of smoking: A longitudinal investigation. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55(2):161–166. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.2.161. doi: 10-1001/pubs.Arch Gen Psychiatry-ISSN-0003-990x-55-2-yoa6330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Department of Education. The California Healthy Kids Survey (CHKS) West Ed Survey; 2006. http://www.chks.wested.org. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance – United States, 2014. MMWR. 2013;63(SS 4) [Google Scholar]

- Cole ER. Intersectionality and research in psychology. American Psychologist. 2009;64(3):170–180. doi: 10.1037/a0014564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuéllar I, Arnold B, Maldonado R. Acculturation rating scale for Mexican Americans-II: A revisiion of the original ARSMA scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1995;17(3):275–304. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cupito AM, Stein GL, Gonzalez LM. Familial Cultural Values, Depressive Symptoms, School Belonging and Grades in Latino Adolescents: Does Gender Matter? Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2014:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10826/-014-9967-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De la Rosa MR. Acculturation and Latino adolescents’ substance use: A research agenda for the future. Substance Use and Misuse. 2002;37:429–456. doi: 10.1081/ja-120002804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demaray MK, Malecki CK. The relationship between perceived social support and maladjustment for students at risk. Psychology in the Schools. 2002;39(3):305–316. doi: 10.1037/lat0000014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards LM, Romero AJ. Coping with discrimination among Mexican descent adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2008;30(1):24–39. doi: 10.1177/0739986307311431. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis SR, Rios-Vargas M, Albert NG. The Hispanic population: 2010. Washington: U.S. Census Bureau; 2011. (Census Brief C2010BR-04). [Google Scholar]

- Forster M, Dyal SR, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Chou CP, Soto DW, Unger JB. Bullying victimization as a mediator of associations between cultural/familial variables, substance use, and depressive symptoms among Hispanic youth. Ethnicity & health. 2013;18(4):415–432. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2012.754407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry R, Passel J. Latino children: A majority are US born-born offspring of immigrants. Washington, D.C: Pew Hispanic Center; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez LM, Stein GL, Kiang L, Cupito AM. The impact of discrimination and support on developmental competencies in latino adolescents. Journal of Latina/o Psychology. 2014;2(2):79. doi: 10.1037/lat0000014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guyll M, Matthews KA, Bromberger JT. Discrimination and unfair treatment: Relationship to cardiovascular reactivity among african american and european american women. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2001;20(5):315–325. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.20.5.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado A. Multiple lenses: Multicultral feminist theory. In: Landrine H, Felipe Russo N, editors. Handbook of diversity in feminist psychology. New York: Springer; 2010. pp. 29–54. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. Released 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM; [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, O’Malley, Miech, Bachman, Schulenberg . Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2014. Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kam JA, Cleveland MJ, Hecht ML. Applying general strain theory to examine perceived discrimination’s indirect relation to mexican-heritage youth’s alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use. Prevention Science: The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research. 2010;11(4):397–410. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0180-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Neale MC, MacLean CJ, Heath AC, Eaves LJ, Kessler RC. Smoking and major depression. A causal analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50(1):36–43. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820130038007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Cortina LM. Latino/a depression and smoking: An analysis through the lenses of culture, gender, and ethnicity. American journal of community psychology. 2013;51(3–4):332–346. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9553-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Bares C, Delva J. Correlates of Chilean adolescents’ negative attitudes toward cigarettes: The role of gender, peer, parental, and environmental factors. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2012;14(2):142–152. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Soto D, Baezconde-Garbanati L. Acculturation, gender, depression, and cigarette smoking among U.S. Hispanic youth: The mediating role of perceived discrimination. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40:1519–1533. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9633-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Unger JB, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Ritt-Olson A, Soto D. Acculturation, enculturation, and symptoms of depression in Hispanic youth: the roles of gender, Hispanic cultural values, and family functioning. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2012;41:1350–1365. doi: 10.07/s10964-012-9774-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson D. The logic and implications of a person-centered approach. In: Cairns RB, editor. Methods and models for studying the individual. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 33–64. [Google Scholar]

- Magnussion D, Stattin H. Person-context interaction theories. In: Lerner RM, Damon W, editors. Hanbook of child psychology. Vol. 1. New York: Wiley; 1998. pp. 685–759. (Theoretical Models of Human Development). [Google Scholar]

- Maurizi LK, Ceballo R, Epstein-Ngo Q, Cortina KS. Does neighborhood belonging matter? Examining school and neighborhood belonging as protective factors for Latino adolescents. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2013;83(2–3):323. doi: 10.1111/ajop.12017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Seventh. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén Copyright; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nezami E, Unger J, Tan S, Mahaffey C, Ritt-Olson A, Sussman S, Nguyen-Michel S, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Azen S, Johnson CA. The influence of depressive symptoms on experimental smoking and intention to smoke in a diverse youth sample. Nicotine & tobacco research. 2005;7(2):243–248. doi: 10.1080/14622200500055483. doi: 10.10801114622200500055483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Fuller-Rowell T, Burrow AL. Racial discrimination and the stress process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;96:1259–1271. doi: 10.1037/a0015335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Huang S, Schwartz SJ, Maldonado-Molina MM, Bandiera FC, de la Rosa M, Pantin H. What accounts for differences in substance use among US-born and immigrant Hispanic adolescents?: Results from a longitudinal prospective cohort study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;45(2):118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quattrocki E, Baird A, Yurgelun-Todd D. Biological aspects of the link between smoking and depression. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2000;8(3):99–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez N. New Southern Neighbors: Latino immigration and prospects for intergroup relations between African-Americans and Latinos in the South. Latino Studies. 2012;10:18–40. doi: 10.1057/lst.2012.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, Wiggs CB, Valencia C, Bauman S. Latina teen suicide and bullying. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2013;35(2):159–173. doi: 10.1177/0739986312474237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, Edwards LM, Bauman S, Ritter MK. Preventing adolescent depression and suicide among Latinas: Relience research and theory. New York: Springer; 2014. Latina adolescent resilience rooted within cultural strengths; pp. 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Sam DL, Berry JW. Acculturation when individuals and groups of different cultural backgrounds meet. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2010;5(4):472–481. doi: 10.1177/1745691610373075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT® 13.1 User’s Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL. Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. London: Chapman & Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Szapocznik J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. American Psychologist. 2010;65:237–251. doi: 10.1037/a0019330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smokowski PR, Bacallao M. Entre Dos Mundos/Between Two Worlds Youth Violence Prevention Comparing Psychodramatic and Support Group Delivery Formats. Small Group Research. 2009;40(1):3–27. doi: 10.1177/1046496408326771. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Wagner KD, Soto DW, Baezconde-Garbanati L. Parent-child acculturation patterns and substance use among Hispanic adolescents: A longitudinal analysis. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2009;30(3–4):293–313. doi: 10.1007/s10935-009-0178-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health. Let’s make the next generation tobacco-free: Your guide to the 50th anniversary Surgeon General’s report on smoking and Health 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Zeiders KH, Roosa MW, Knight GP, Gonzales NA. Mexican American adolescents’ profiles of risk and mental health: A person-centered longitudinal approach. Journal of adolescence. 2013;36(3):603–612. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of personality assessment. 1988;52(1):30–41. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]