Abstract

Introduction:

Periodontitis is inflammation of supporting tooth structure. Most individuals get affected by this disease if oral hygiene is not maintained. There are various mechanical and chemical methods for oral hygiene maintenance. In recent past, interest has been diverted toward the herbal/traditional product in oral hygiene maintenance as they are free from untoward effect.

Aim:

To assess the efficacy of subgingival irrigation with herbal extract (HE) as compared with 0.2% chlorhexidine (CHX) on periodontal health in patients who have been treated for chronic periodontitis, and still have residual pocket of 3–5 mm.

Materials and Methods:

This was a controlled, single-blind, randomized study for 3 months. Patients were allocated in two groups (n = 15 each): (1) 0.2% CHX (control group); (2) HE consisting of Punica granatum Linn. (pomegranate), Piper nigrum Linn. (black pepper), and detoxified copper sulfate (test group). Solutions were used for the irrigation using pulsated irrigating device, WaterPik. Clinical outcomes evaluated were plaque index (PI), sulcus bleeding index (SBI), probing depth at baseline, 15th, 30th, 60th, and 90th day. Microbiologic evaluation was done at baseline and 90th day.

Results:

Significant reduction in PI was seen in the group of irrigation with HE. While comparing SBI, irrigation with CHX shows a better result. Other parameters such as probing pocket depth and microbiological counting were similar for both groups.

Conclusion:

Irrigation with HE is a simple, safe, and noninvasive technique with no serious adverse effects. It also reduces the percentage of microorganism in periodontal pocket.

Keywords: Chlorhexidine, herbal extract, periodontal disease, subgingival irrigation

Introduction

The periodontium is highly vulnerable to disease processes. Bacterial plaque and their biologically active products have been implicated as the primary etiologic agents of periodontal disease.[1,2] These microorganisms damage the tissues by releasing various toxins, enzymes, and metabolic products which are considered important in the causation of the gingivitis and periodontitis.[3]

Subgingival microbiota harbors more than 200 bacterial species.[4] Many of which have periodontal pocket as their main habitat. The appearance of subgingival pathogenic Gram-negative microbial flora is undoubtedly related to anaerobic environment inherent in pockets that facilitate proliferation of such microorganisms.[5]

Studies report that supragingival hygiene aids do not totally eliminate periodontal inflammation.[6,7] It has been shown to be virtually impossible to remove subgingival plaque by routine brushing and flossing. Similarly, direct irrigation with the mouthwash failed to reach in the pocket. To overcome these problems, root planning, surgery, and local and systemic antimicrobial agents have been employed to facilitate the elimination of pocket microflora.

In the recent past, attention has recently been focused on the methods of localized drug delivery. Pulsating irrigation device is very helpful in delivering the drug to the base of the pocket. Various studies have shown improved results when pulsating irrigation device is compared with mouth rinse in reducing gingival inflammation.[8,9,10] Chlorhexidine (CHX) is considered a “gold standard” antibacterial solution and is extensively used as a mouthwash and irrigating solution. However, it has certain side effects after prolonged uses such as loss of taste sensation, staining of the teeth, calculus formation, and in some cases, parotid swelling is observed.

Recently, various herbal extracts (HEs) have been tried as mouthwash and irrigating solution with the promising result. Being herbal products, they do not cause much side effects and thus can be used safely. The results of the previous study have suggested that the dental gel containing Azadirachta indica Linn. (Neem) extract has significantly reduced the plaque index (PI) and bacterial count than that of the control group (0.2% CHX).[11] A study suggested that the herbal preparation proved more effective than a conventional mouthwash at reducing gingival inflammation.[12]

Hence, in this study, an attempt is made to assess the efficacy of different antimicrobial agents (CHX vs. HE) on periodontal health in patients who have been treated for chronic periodontitis and still have residual pocket of around 3–5 mm after scaling and root planing (SRP).

Materials and Methods

A total of 30 systemically healthy patients with chronic periodontitis (after diagnosis and before full mouth prophylaxis) were recruited from the pool of patients who visited the Department of Periodontology and Implantology. Ethical clearance has been obtained from the Institutional Ethical Committee (M.G.V. Dental College and Hospital, Maharashtra University of Health Sciences) before the commencement of the research work. Informed written consent was obtained from the patients before starting the study.

Inclusion criteria

Patients with chronic periodontitis who had residual pocket of 3–5 mm 1 month after SRP were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with aggressive periodontitis, cigarette smokers, on antibiotic therapy within previous 6 months, history of rheumatic fever, or other conditions requiring prophylactic antibiotic therapy before the dental treatment, history of blood dyscrasias, diabetes, hepatic or renal disease, currently pregnant or lactating women, patient with the history of periodontal treatment within the last 6 months.

Grouping and posology

This was a controlled, single-blind, randomized study for 3 months. Patients (n = 30) were randomly assigned by simple randomization (coin test) in control group and test group.

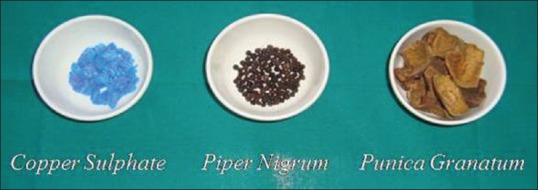

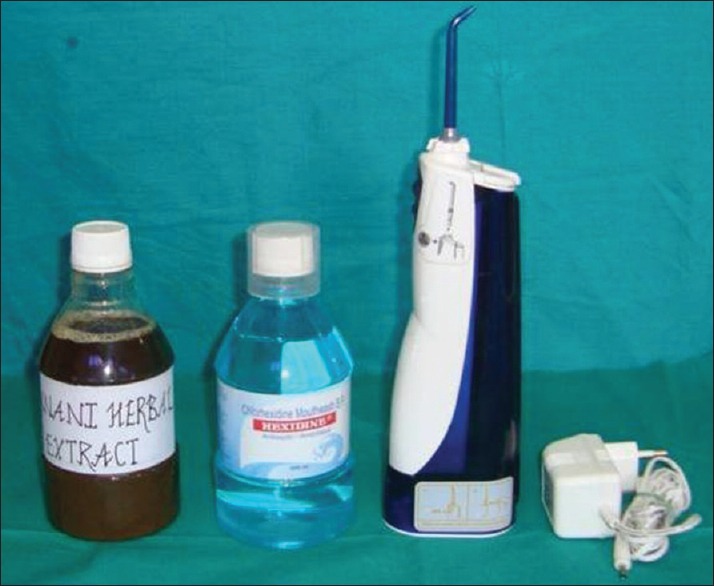

In control group, commercially available 0.2% CHX Hexidine® (ICPA Health Products Ltd., Maharashtra, India) was administered. Whereas in test group, HE consisting of Punica granatum Linn. (pomegranate - fruit rind), Piper nigrum Linn. (black pepper), and detoxified copper sulfate [Figure 1] was administered. Both fluids were used for the irrigation of residual pockets using pulsated irrigating device, WaterPik® (Dentos India Private Ltd., Mumbai, Maharashtra, India) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Raw herbal product collected from market

Patients were subjected to SRP. After 1 month, SRP patients who fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria were included into the study. The irrigation was performed in each individual as a demonstration. Irrigation device was dispensed to the patient with specific group with the verbal and written instruction. Patients in both the groups were asked to irrigate with the respective solution twice daily after tooth brushing [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Irrigation device while delivering irrigating solution at gingival margin

Test drug

Initially, raw materials were collected from the market; dried peel of P. granatum Linn., edible P. nigrum Linn., crystals of copper sulfate [Figure 3]. Before preparing fine powder, copper sulfate was detoxified by roasting it at 65–70°C for 15 min. Then, the amount to be used in the single irrigating mouthwash was calculated from the previous Unani paste and powder formulation and multiplied by the dosage. Formulation for a single dose of irrigation derived from the National Formulary of Unani Medicine.[13]

Figure 3.

Irrigating solutions (herbal extract, chlorhexidine) with irrigating device

P. granatum Linn.: 3000 mg (3 g)

P. nigrum Linn.: 1250 mg (1.25 g)

Copper sulfate: 60 mg (0.6 g).

After that, a machined fine powder was prepared from the entire components. Aqueous extract was prepared by dissolving each component separately in distilled water for about 1 h and then filtration was done to remove any solid particles from the solution. They were then mixed to from a single solution for irrigation. WaterPik model no. WP-360 E2 with a reservoir capacity of 150 ml was used with the tip for irrigation at a pressure of 60 psi.

Assessment criteria

Clinical parameters such as probing depth, PI,[14] Sulcus bleeding index (SBI),[15] and dark-field microscopy were recorded at baseline and microbiological sample was taken from the pocket for the dark-field microscopic analysis. All clinical parameters were recorded at 15 days, 30 days, 60 days, and 90 days. Dark-field microscopy was done at 90 days.

Statistical analysis

To study whether the test group and control group differ significantly from baseline to 90 days with each parameter and to know the mean change in values, paired t-test was used at 95% confidence level and 14 degree of freedom over various time intervals.

To analyze which pair actually shows a significant difference and over which parameter, unpaired t-test was carried out at 95% confidence level and 28 degree of freedom over various time intervals.

Observations and Results

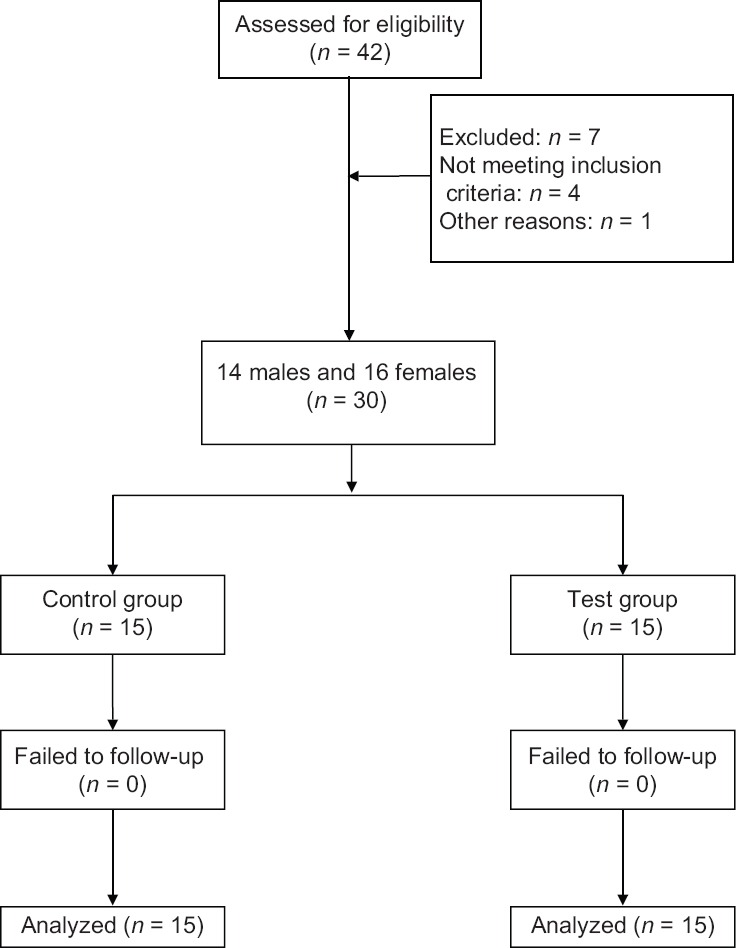

Consort flow chart exhibiting the numbers of subject finally analyzed and those dropped out have been described [Figure 4]. Thirty patients completed the study, out of which 14 were male and 16 were female.

Figure 4.

Study flow chart

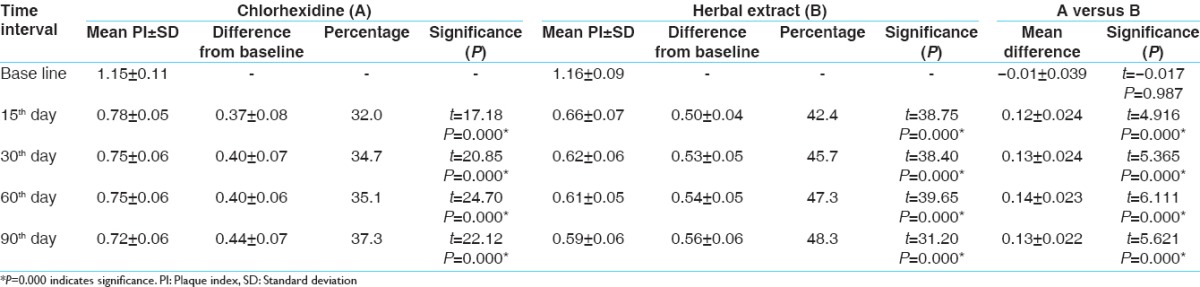

The results show that SRP and CHX + irrigation and SRP with HE + irrigation are effective for treating chronic periodontitis. Irrigation with HE shows more reduction of PI when compared to irrigation with the CHX group [Table 1]. While comparing SBI, irrigation with CHX shows a better result over irrigation with HE at an interval of 30, 60, and 90 days [Table 2]. Other parameters such as probing pocket depth (PPD) and microbiological counting were same for both the groups [Tables 3 and 4]. All the parameters in both the groups show a greater reduction at 15 days which remain stable up to 90 days.

Table 1.

Mean difference in plaque index

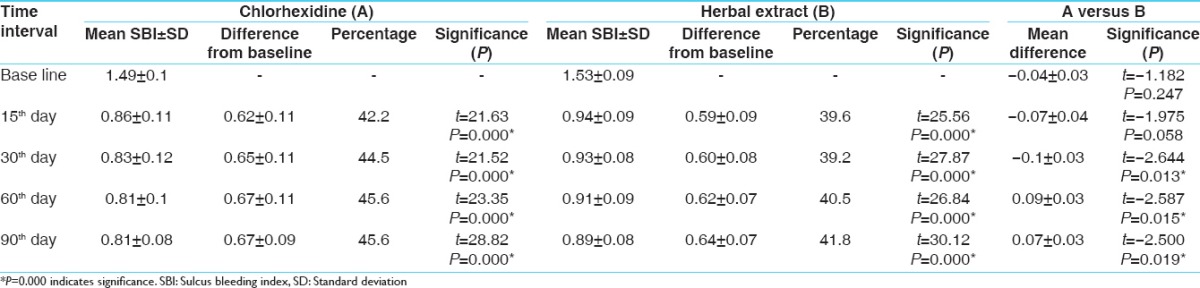

Table 2.

Mean difference in sulcus bleeding index

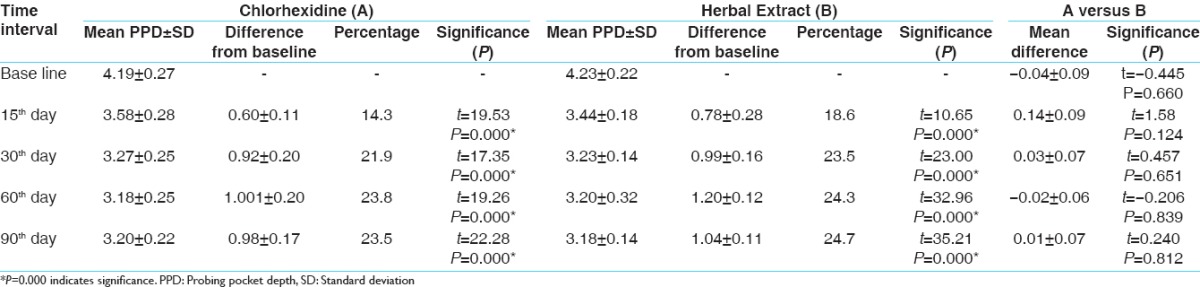

Table 3.

Mean difference in probing pocket depth

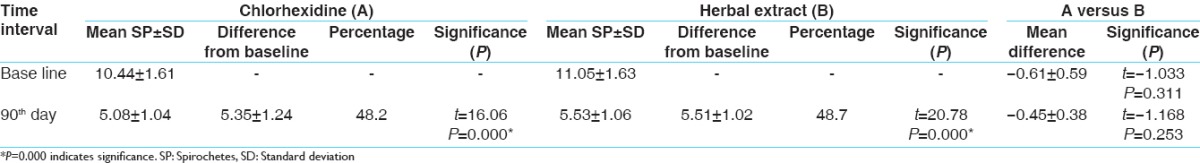

Table 4.

Mean difference in number of spirochetes

Discussion

Specific bacterial plaques and their biologically active products have been implicated as the primary etiologic agents of periodontal disease.[16] Periodontal therapy centers around the removal and control of plaque and the restoration of a normal bacterial flora in the gingival sulcus.[8] Treatment of periodontal disease is routinely based on oral hygiene procedures and root debridement, which reduces the periodontal bacteria.[17]

The successful long-term management of periodontitis requires a proper maintenance of the results obtained after treatment.[17] This can be successfully done with the adjunctive use of antimicrobials.[18] Subgingival irrigation with a chemotherapeutic agent, when delivered with an irrigation device, may be a beneficial adjunctive modalit[19]

In this study, we were able to manage moderate cases, which may have needed surgical treatment, by noninvasive procedure using local drug delivery. The primary objective of clinical trial was comparison between SRP and CHX irrigation (control group) and SRP and HE irrigation (test group).

CHX was selected as control group because of its antiplaque effect, which was proved by the study.[20] HE was used because P. granatum was evaluated for its antimicrobial activity against oral pathogens, and preliminary results have shown that it has the potential to be used to prevent periodontal diseases. Likewise, P. nigrum was evaluated for antibacterial activity in various studies and it has been shown that it has good antibacterial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative organisms.[21] Copper sulfate is not extensively studied for periodontal disease, but various Unani and Ayurvedic formulations have used it because of its astringent and antiseptic effect.[13,22]

In this study, both test and control groups showed a decrease in all the parameters when compared from baseline to 90 days. Intergroup comparison showed no significant change in all parameters except PI in which test group showed more reduction than control group when compared from baseline to 90 days.

Plaque index

In control group, the maximum reduction is at 15 days, after that results remain stable. These findings are comparable to the results of other previous studies.[23,24] In test group, the maximum reduction is at 15 days, after that results remain stable. These findings are also comparable to the results of other previous studies.[25] Intergroup comparison shows more reduction of PI in test group at all the points of time when compared with the control group.

Sulcus bleeding index

In control group, the maximum reduction is at 15 days, after that result remains stable. These findings are comparable to the results of other studies.[24,26] In test group, the maximum reduction is at 15 days, after that results remain stable. These findings are comparable to the results of other studies.[27] Intergroup comparison: Control group showed more reduction in SBI at 30, 60, and 90 days when compared with the test group. At 15 days, reduction in both the groups was almost same.

Probing pocket depth

In control group, the maximum reduction is at 15 days which followed gradual reduction over 90 days which was statistically significant. These findings are comparable to the results of other previous studies.[28,29] In test group, the maximum reduction is at 15 days which followed gradual reduction over 90 days which was statistically significant. These findings are comparable to the results of other previous studies.[12] In intergroup comparison, both the groups showed similar result in PPD reduction at all points of time.

Spirochetes count

In control group, the mean reduction in spirochetes (SP) count was statistically significant from baseline to 90 days. These findings are comparable to the results of other previous studies.[29] In test group, the mean SP count was statistically significant from baseline to 90 days. These findings are comparable to the results of other previous studies.[30,31] In intergroup comparison, there was no statistically significant reduction between the two groups.

Conclusion

Irrigation with HE is a simple, safe, and noninvasive technique and no serious adverse effects were recorded with the product. It reduces the percentage of microorganism in periodontal pocket. These short-term data reveal that the patients can be stabilized with the irrigation with both HE and CHX. Future research with large sample size and extended follow-up period should evaluate the long-term effect of regular application of HE.

In the future, mechanism of action of HE in plaque reduction and its substantivity needs to be evaluated and documented. The use of these products in oral hygiene maintenance needs to be encouraged.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Boyd RL, Leggott P, Quinn R, Buchanan S, Eakle W, Chambers D. Effect of self-administered daily irrigation with 0.02% SnF2 on periodontal disease activity. J Clin Periodontol. 1985;12:420–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1985.tb01378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Listgarten MA, Lindhe J, Hellden L. Effect of tetracycline and/or scaling on human periodontal disease. Clinical, microbiological, and histological observations. J Clin Periodontol. 1978;5:246–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1978.tb01918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slots J. Subgingival microflora and periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1979;6:351–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1979.tb01935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dalhen G, Wennstrom JL, Grondahl K, Heiji L. Microbiological observations at periodic subgingival antimicrobial irrigation of periodontal pockets. J Dent Res. 1989;68:1714–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cobb CM, Rodgers RL, Killoy WJ. Ultrastructural examination of human periodontal pockets following the use of an oral irrigation device in vivo. J Periodontol. 1988;59:155–63. doi: 10.1902/jop.1988.59.3.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenstein G. Effects of subgingival irrigation on periodontal status. J Periodontol. 1987;58:827–36. doi: 10.1902/jop.1987.58.12.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stanley A, Wilson M, Newman HN. The in vitro effects of chlorhexidine on subgingival plaque bacteria. J Clin Periodontol. 1989;16:259–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1989.tb01651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun RE, Ciancio SG. Subgingival delivery by an oral irrigation device. J Periodontol. 1992;63:469–72. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.5.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dentino A, Ciancio SG, Zambon JJ, Reynolds H, Bessinger M. Effect on subgingival irrigation and listerine rinsing on periodontal tissues. J Dent Res. 1993;72:335. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fine JB, Harper DS, Gordon JM, Hovliaras CA, Charles CH. Short-term microbiological and clinical effects of subgingival irrigation with an antimicrobial mouthrinse. J Periodontol. 1994;65:30–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pai MR, Acharya LD, Udupa N. Evaluation of antiplaque activity of Azadirachta indica leaf extract gel – A 6-week clinical study. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;90:99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2003.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pistorius A, Willershausen B, Steinmeier EM, Kreislert M. Efficacy of subgingival irrigation using herbal extracts on gingival inflammation. J Periodontol. 2003;74:616–22. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.5.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anonymous. National Formulary of Unani Medicine, Part 1, (English) New Delhi: Govt. of India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Dept of AYUSH; 2006. pp. 248–50. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silness J, Loe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. II. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condtion. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:121–35. doi: 10.3109/00016356408993968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mühlemann HR, Son S. Gingival sulcus bleeding – A leading symptom in initial gingivitis. Helv Odontol Acta. 1971;15:107–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nosal G, Scheidt MJ, O’Neal R, Van Dyke TE. The penetration of lavage solution into the periodontal pocket during ultrasonic instrumentation. J Periodontol. 1991;62:554–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.1991.62.9.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Academy of Periodontology. Treatment of gingivitis and periodontitis (Position Paper) J Periodontol. 1997;68:1246–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cobb CM. Non-surgical pocket therapy: Mechanical. Ann Periodontol. 1996;1:443–90. doi: 10.1902/annals.1996.1.1.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Killoy WJ, Polson AM. Controlled local delivery of antimicrobials in the treatment of periodontitis. Dent Clin North Am. 1998;42:263–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Löe H, Schiott CR. The effect of mouthrinses and topical application of chlorhexidine on the development of dental plaque and gingivitis in man. J Periodontal Res. 1970;5:79–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1970.tb00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dorman HJ, Deans SG. Antimicrobial agents from plants: Antibacterial activity of plant volatile oils. J Appl Microbiol. 2000;88:308–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amruthesh S. Dentistry and Ayurveda – IV: Classification and management of common oral diseases. Indian J Dent Res. 2008;19:52–61. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.38933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soh LL, Newman HN, Strahan JD. Effects of subgingival chlorhexidine irrigation of periodontal inflammation. J Clin Periodontol. 1982;9:66–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1982.tb01223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walsh TF, Glenwright HD, Hull PS. Clinical effects of pulsed oral irrigation with 0.2% chlorhexidine digluconate in patients with adult periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19:245–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1992.tb00461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sastravaha G, Gassmann G, Sangtherapitikul P, Wolf D. Herbal extracts as adjunct in supportive periodontal therapy. Int Poster J Dent Oral Med. 2006;8(1):305. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wennström JL, Heijl L, Dahlén G, Gröndahl K. Periodic subgingival antimicrobial irrigation of periodontal pockets (I).Clinical observations. J Clin Periodontol. 1987;14:541–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1987.tb00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sastravaha G, Yotnuengnit P, Booncong P, Sangtherapitikul P. Adjunctive periodontal treatment with Centella asiatica and Punica granatum extracts. A preliminary study. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2003;5:106–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braatz L, Garrett S, Claffey N, Egelberg J. Antimicrobial irrigation of deep pockets to supplement non-surgical periodontal therapy. II. Daily irrigation. J Clin Periodontol. 1985;12:630–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1985.tb00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reynolds MA, Lavigne CK, Minah GE, Suzuki JB. Clinical effects of simultaneous ultrasonic scaling and subgingival irrigation with chlorhexidine. Mediating influence of periodontal probing depth. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19:595–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1992.tb00689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Negi P, Jayaprakasha G. Antioxidant and antibacterial activities of Punica granatum peel extracts. J Food Sci. 2003;68:1473–7. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bele AA, Jadhav VM, Nikam SR, Kadam VJ. Antibacterial potential of herbal formulation. Res J Microbiol. 2009;4:164–7. [Google Scholar]