Abstract

Background: A limited number of school-based intervention studies have explored mediating mechanisms of theory-based psychosocial variables on obesity risk behavior changes. The current study investigated how theory-based psychosocial determinants mediated changes in energy balance-related behaviors (EBRBs) among urban youth.

Methods: A secondary analysis study was conducted using data from a cluster randomized controlled trial. Data from students at 10 middle schools in New York City (n = 1136) were used. The intervention, Choice, Control, and Change curriculum, was based on social cognitive and self-determination theories. Theory-based psychosocial determinants (goal intention, cognitive outcome expectations, affective outcome expectations, self-efficacy, perceived barriers, and autonomous motivation) and EBRBs were measured with self-report questionnaires. Mediation mechanisms were examined using structural equation modeling,

Results: Mediating mechanisms for daily sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) consumption and purposeful stair climbing were identified. Models with best fit indices (root mean square error of approximation = 0.039/0.045, normed fit index = 0.916/0.882; comparative fit index = 0.945/0.932; Tucker–Lewis index = 0.896/0.882, respectively) suggested that goal intention and reduced perceived barriers were significant proximal mediators for reducing SSB consumption among both boys and girls or increasing physical activity by stair climbing among boys. Cognitive outcome expectations, affective outcome expectations, self-efficacy, and autonomous motivation indirectly mediated behavioral changes through goal intention or perceived barriers (p < 0.05 to p < 0.001). The final models explained 25%–27% of behavioral outcome variances.

Conclusions: Theory-based psychosocial determinants targeted in Choice, Control, and Change in fact mediated behavior changes in middle school students. Strategies targeting these mediators might benefit future success of behavioral interventions. Further studies are needed to determine other potential mediators of EBRBs in youth.

Introduction

Given the high rates of overweight and obesity in youth,1 determining and utilizing the most effective behavioral change strategies in obesity prevention programs is critical. Energy-dense, palatable, low-cost easily available foods and large portion sizes, as well as sedentary behaviors and lack of physical activity, contribute to positive energy balance, which may increase risks of overweight and obesity in youth.2,3

Among nutrition intervention studies targeting energy balance-related behaviors (EBRBs) in school-aged children and adolescents,4–7 a limited number of studies have investigated mediation mechanisms of behavior changes.3,5,8–10

According to Baranowski's mediating variable framework,11,12 theory-based mediating variables are substantial components under the assumption that mediators cause the targeted behavior changes in behavioral change interventions. Statistically testing this assumption with mediation analysis allows researchers to determine whether the prevention program changed the mediator, which in turn changed the dependent variable, thereby providing tests of the theoretical basis of the intervention.12,13 Researchers can therefore build a theory of the causal process for behavioral change through mediation analysis and eliminate potential mediators unrelated to the target behavior and their corresponding intervention activities.5,14 Thus, mediating variables with higher predictability provide more effective levers to promote behavior changes, aiding researchers and program developers in the construction of more efficient and effective interventions.9,15–18

Reviews on mediating mechanisms of school-based EBRB interventions have indicated that effective mediators are behavior specific.3,10 For example, knowledge and attitude,19 outcome expectancies, and stages of change20 were significant mediators for fruit and vegetable intake changes in school children and adolescents; attitude and habit strength8 were significant mediators for soft drink intake changes in boys (aged 12–13 years), and self-efficacy,9,21,22 autonomy and intention,23 and enjoyment15 were reported as significant mediators for physical activity behavior change in adolescents. However, a large number of other variables thought to be potential mediators of behavior changes in intervention studies have shown no statistically significant mediation effect.3,10 Collective evidence on significant relationships between theoretical mediators and EBRB outcomes, from diverse studies, especially using longitudinal research designs would strengthen future intervention research.24

The purpose of this study was to determine mediation mechanisms of theory-based psychosocial variables on behavior changes in the Choice, Control, and Change trial. Choice, Control, and Change was a school-based nutrition education intervention to reduce obesity risks in urban minority youth, and it has been reported that it was effective in improving targeted psychosocial determinants based on social cognitive and self-determination theories, as well as EBRB outcomes.25 Objectives of the current study were to examine which psychosocial variables significantly mediate EBRB changes in Choice, Control, and Change and to determine the best mediation pathway of multiple psychosocial variables on each behavior outcome using structural equation modeling (SEM).

Methods

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

This study was a secondary data analysis of a cluster randomized controlled trial, Choice, Control, and Change.25 Participants were 6th or 7th grade students at 10 New York City public middle schools in underserved neighborhoods (n = 1136). Five intervention schools received the Choice, Control, and Change curriculum in the 2006–2007 school year and five control schools received the standard science curriculum. Students were predominantly African American and Hispanic (over 90%) and 78% were eligible for free and reduced price meals. Detailed information on study design, participants, and intervention has been reported elsewhere.25 The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Teachers College, Columbia University, and the New York City Department of Education.

Outcomes and Measures

Behavioral and theory-based psychosocial outcome data were used. EBRBs included fruit and vegetables, sweetened beverages, processed packaged snacks, and fast food intakes, and physical activity and recreational screen time (ST) behaviors, which were measured with an instrument, the EatWalk Survey.25 Walking and stair climbing were emphasized in the curriculum as means of increasing physical activity in students' daily lives. Recreational ST included TV and video games.

The questions included frequency (days/week) and serving sizes consumed each time for dietary outcomes and duration for physical activity outcomes. Psychosocial variables of cognitive outcome expectations, affective outcome expectations, perceived barriers, self-efficacy, goal intention, and autonomous motivation were measured with a self-report questionnaire, the Tell Me about You survey,25 with questions having 4- or 5-point Likert-type response options.

Both surveys were administered in the classroom setting over one regular science class period before and after curriculum implementation. Two or three trained research staff administered the surveys to students in each class with teachers assisting with class management issues during the surveys. Informed consent forms were sent to students' parents and caregivers, and students whose parents refused their participation were instructed to read books quietly in class.

Statistical Analysis

To see if mediation analyses were appropriate, the effects of the intervention on behavioral outcomes were examined in daily food/drink intake or activity level. To obtain estimates of daily food/drink intakes and activity levels for EBRBs, frequency and serving size/duration were multiplied.8 The main intervention effects on these outcomes are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Intervention Effects on Behavioral Outcomes in Daily Food or Beverage Consumptions and Physical Activities

| ICCs | Pooled adjusted mean (95% CI)* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behaviors | Pre | Post | Gender difference | Intervention | Control | Pooled F-statistic | Pooled p-value | Effect size |

| Fruita | 0.007 (−0.011, 0.025) | 0.014 (−0.010, 0.039) | NS | 3.17 (2.94, 3.39) | 3.38 (3.14, 3.61) | 1.613 | 0.204 | 0.08 |

| Vegetablesb | 0.014 (−0.011, 0.038) | 0.016 (−0.010, 0.042) | NS | 1.72 (1.56, 1.87) | 1.67 (1.50, 1.84) | 0.872 | 0.694 | 0.03 |

| Waterc | 0.007 (−0.011, 0.025) | 0.009 (−0.011, 0.030) | NS | 58.61 (54.72, 62.50) | 57.09 (53.01, 61.17) | 0.263 | 0.609 | 0.04 |

| Sugar-sweetened beveragesc | 0.025 (−0.010, 0.061) | 0.055 (−0.007, 0.116) | NS | 32.35 (29.24, 35.46) | 37.96 (35.32, 40.59) | −8.054 | 0.005 | 0.21 |

| Processed packaged snacksd | 0.018 (−0.010, 0.046) | 0.028 (−0.009, 0.041) | NS | 2.36 (2.19, 2.53) | 2.57 (2.38, 2.75) | −2.843 | 0.092 | 0.11 |

| Fast foode | 0.008 (−0.011, 0.026) | 0.015 (−0.011, 0.065) | NS | 2.07 (1.86, 2.28) | 2.16 (1.95, 2.37) | −0.342 | 0.559 | 0.04 |

| Purposeful walkingf | 0.007 (−0.010, 0.023) | 0.036 (−0.008, 0.08) | NS | 1.95 (1.83, 2.07) | 1.68 (1.55, 1.80) | 10.227 | 0.001 | 0.20 |

| Purposeful stair climbingg | 0.005 (−0.010, 0.020) | 0.029 (−0.009, 0.067) | Total | 1.76 (1.60, 1.93) | 1.33 (1.19, 1.48) | 13.682 | <0.001 | 0.24 |

| Boys | 2.14 (1.88, 2.40) | 1.34 (1.10, 1.58) | 19.378 | <0.001 | 0.45 | |||

| Girls | 1.40 (1.18, 1.63) | 1.25 (1.01, 1.50) | 0.745 | 0.389 | 0.09 | |||

| Screen timeh | 0.016 (−0.009, 0.041) | 0.045 (−0.007, 0.097) | NS | 3.75 (3.54, 3.96) | 4.35 (4.11, 4.58) | −13.749 | <0.001 | 0.27 |

Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with 10 multiple imputed datasets (n = 1136).

Unit of measures per day: a = pieces; b = cups; c = ounces; d = number of packages; e = number of fast food; f = times of walking; g = number of flights; h = hours

Significant test at p < 0.006 with the Bonferroni correction.

Bold represents significant outcomes.

ICCs, intraclass correlation coefficients; NS, not significant.

Because the unit of randomization of the study was school, the school level intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were estimated.26 ICCs ranged from 0.005 to 0.055 and 95% confidence intervals indicated that clustering was not significantly high. In addition, considering the fact that there were only five schools in each study condition, multilevel analyses were not performed.

No school dropped out during the study period. Therefore, data from all 10 schools were used.25 When missing data analyses were performed, the average percentage missing data was 26.2%. Little's missing completely at random test27 indicated that there is not enough evidence to suggest that the missing pattern was not completely at random (χ2 = 18,528.0, p = 0.990). Missing data were treated with multiple imputations and univariate analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed with 10 multiple imputed datasets, and then multiple tests were adjusted with the Bonferroni correction. The results of ANCOVA showed that sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) consumption, purposeful walking (WALK), purposeful stair climbing (STAIR), and ST behaviors were significantly different between intervention and control groups, controlling for gender and baseline data. There was a gender and intervention interaction for STAIR behavior, showing that only boys in the intervention group had a significantly different STAIR outcome compared with the control group. Based on these results, mediation mechanisms were investigated with psychosocial determinants and behavioral outcomes related to SSB consumption, WALK, and STAIR (boys). There were no psychosocial determinants measured specifically for ST25,28; therefore, mediation analysis related to ST could not be performed.

Psychometric structures and invariance analysis

Before conducting mediation analyses, confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were performed for both pre- and postintervention measurements to assure that the same constructs were being measured over time. Scales, questions, and response options are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Internal Consistency of Psychosocial Variables of Choice, Control, and Change Curriculum Implemented in New York City Middle Schools

| Scale | Prefactor loadingd | Postfactor loadingd | α at Pre | α at Post |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goal intentiona | ||||

| Will you drink less soda and other sweetened beverages? | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Will you walk or take stairs more? | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Cognitive outcome expectationsb | ||||

| I believe that drinking lots of sweetened beverages… | 0.76 | 0.822 | ||

| Contributes to our developing high blood pressure | 0.720 | 0.823 | 3 | |

| Contributes to our developing diabetes | 0.819 | 0.862 | ||

| Contributes to weight gain | 0.625 | 0.657 | ||

| I believe walking or stair climbing… | 0.77 | 0.790 | ||

| Contributes to weight gain | 0.801 | 0.781 | 5 | |

| Contributes to our developing high blood pressure | 0.789 | 0.834 | ||

| Affective outcome expectationsb | ||||

| I believe that drinking lots of sweetened beverages… | 0.69 | 0.729 | ||

| Is satisfying | 0.620 | 0.673 | 2 | |

| Is cool | 0.780 | 0.789 | ||

| Is important to me | 0.578 | 0.616 | ||

| I believe walking or stair climbing… | 0.76 | 0.776 | ||

| Is cool | 0.805 | 0.743 | 1 | |

| Is important to me | 0.764 | 0.855 | ||

| Self-efficacyc | ||||

| How sure are you that you could drink LESS soda or sweetened beverages… | 0.774 | 0.797 | ||

| When you are at home? | 0.806 | 0.797 | ||

| When you eat meals with your family? | 0.749 | 0.775 | ||

| When you are with your friends (i.e., after school, weekend)? | 0.637 | 0.687 | ||

| How sure are you that you could walk instead of taking the subway or bus… | 0.834 | 0.866 | ||

| When you are with your family? | 0.585 | 0.652 | ||

| When you are with your friends? | 0.544 | 0.654 | ||

| When you do not have enough energy? | 0.532 | 0.605 | ||

| To exercise? | 0.697 | 0.653 | ||

| How sure are you that you could take the stairs instead of taking an elevator or escalator… | ||||

| When you are with your family? | 0.650 | 0.693 | ||

| When you are with your friends? | 0.695 | 0.755 | ||

| When you do not have enough energy? | 0.589 | 0.669 | ||

| To exercise? | 0.687 | 0.666 | ||

| Perceived barriersb | ||||

| It is difficult to eat healthy because… | 0.810 | 0.831 | ||

| It is difficult to resist the soda/sweetened beverages that are available in vending machines and stores | 0.692 | 0.718 | ||

| It is difficult to resist the supersized food and beverages that are available | 0.785 | 0.806 | ||

| It is difficult to pass up the cheaper price of the larger sizes of foods and beverages | 0.752 | 0.812 | ||

| It is difficult to select healthy options that are available in school and stores in my neighborhood | 0.644 | 0.637 | ||

| It is difficult to be physically active because… | 0.78 | 0.777 | ||

| I think walking to places is too much trouble | 0.685 | 0.729 | 1 | |

| Walking is too much work when subways and buses are so convenient to places near by | 0.773 | 0.742 | ||

| It is too tiring to walk the stairs to get to my destination | 0.755 | 0.723 | ||

| Autonomous motivationc | ||||

| Related to eating | 0.92 | 0.922 | ||

| I can set a goal for healthy eating | 0.728 | 0.717 | 1 | |

| When I have a goal for healthy eating, I can follow it through pretty well | 0.748 | 0.747 | ||

| I know how to assess my food intake | 0.684 | 0.720 | ||

| I enjoy keeping track of my eating patterns | 0.672 | 0.611 | ||

| I enjoy making healthy food choices | 0.722 | 0.736 | ||

| I am very interested in having healthier eating patterns | 0.722 | 0.698 | ||

| I feel confident in my ability to make healthy food choices | 0.745 | 0.727 | ||

| I am capable of making changes in my eating habits to make them healthier | 0.724 | 0.755 | ||

| I am capable of maintaining healthy eating habits | 0.731 | 0.752 | ||

| I can take control of my food choices | 0.641 | 0.644 | ||

| I can make good decisions about what I eat | 0.641 | 0.667 | ||

| Related to physical activity | 0.760 | 0.780 | 0.94 | 0.939 |

| I can set a goal for being physically active | 0.818 | 0.821 | 1 | |

| When I have a goal for being physically active, I can follow it through pretty well | 0.771 | 0.784 | ||

| I know how to assess my physical activity | 0.722 | 0.723 | ||

| I enjoy keeping track of my own physical activity | 0.731 | 0.764 | ||

| I am currently doing exercise for pleasure | 0.699 | 0.709 | ||

| I feel confident in my ability to be physically active | 0.781 | 0.737 | ||

| I am capable of making changes in my physical activity habits to make them healthier | 0.753 | 0.718 | ||

| I am capable of maintaining an activity routine | 0.753 | 0.751 | ||

| I can take control of how much physical activity I get | 0.740 | 0.735 | ||

| I can make good decisions to be physically more active | 0.759 | 0.718 | ||

| Model fit | ||||

| RMSEA (90% confidence interval) | 0.041 (0.039, 0.043) | 0.043 (0.041, 0.045) | NA | NA |

| CFI | 0.909 | 0.910 | ||

| TLI | 0.901 | 0.903 | ||

Response options: (a) 1 = will not do it within the next 6 months, 2 = will try within the next 6 months, 3 = plan to do it in a month or so, 4 = currently doing it for past 1–6 months, and 5 = have been doing it for over past 6 months; (b) 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = uncertain, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree; (c) 1 = not sure, 2 = a little sure, 3 = somewhat sure, and 4 = very sure; and (d) standardized.

CFI, comparative fit index; NA, not applicable; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; TLI = Tucker–Lewis index.

Using AMOS software (IBM® SPSS® Amos™ v.23), CFA model fits were evaluated by multiple indices. The χ2 test statistic assessed the absolute fit of the model to the data, but it is sensitive to sample size; therefore, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) were used as model fit indices. Internal consistency reliability tests were performed, yielding Cronbach's alpha values using SPSS (IBM Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0.; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Cronbach's alpha values greater than 0.7 were used as a cutoff for acceptable internal consistency indicators.29

Mediation mechanism model specification

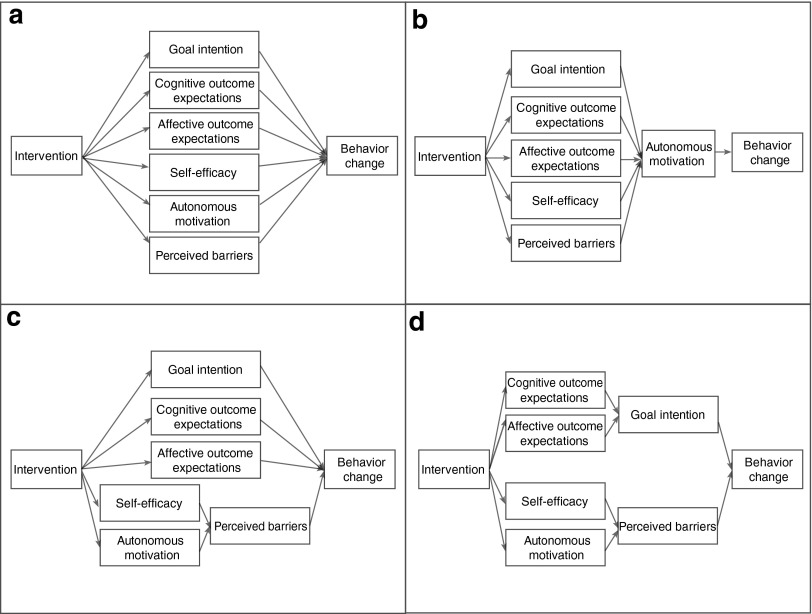

Several structural models were constructed to examine mediation effects (Fig. 1): (a) a basic multiple mediator model, placing all mediating variables in between intervention and behavioral outcomes at once, and (b) a model based on the theoretical framework of the Choice, Control, and Change curriculum.25 In this model, the intervention influences cognitive outcome expectations, affective outcome expectations, perceived barriers, self-efficacy, and goal intention, which together lead to positive autonomous motivation, mediating behavioral changes. In addition, with this specific intervention structure and by constantly examining covariance/variance matrix and regression estimates,30 two more models were hypothesized: (c) a model with plausible relationships among self-efficacy, autonomous motivation, and perceived barriers and (d) a model further considering relationships among cognitive outcome expectations, affective outcome expectations, and goal intention. The Model (c) was based on the Choice, Control, and Change curriculum lessons that emphasized social and environmental barriers for making healthier choices and how to gain confidence and self-regulation skills by overcoming those barriers, and the Model (d) considered the goal intention as a proxy construct that mediates effects of cognitive outcome expectations and affective outcome expectations on behaviors, which have been frequently hypothesized in studies using the Theory of Planned Behavior.31–33

Figure 1.

Mediation models between psychosocial variables and behavior change in the Choice, Control, and Change curriculum intervention implemented in New York City middle schools. Model (a) is a basic multiple mediator model; Model (b) is the theoretical framework of the Choice, Control, and Change; Model (c) is an alternative social cognitive theory (SCT) and self-determination theory (SDT) mediator model; and Model (d) is another alternative SCT, SDT, and goal intention model.

Model fit

Mediation analysis models were tested with Amos v.23. Analyses were performed using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation. FIML was selected because there were missing data. FIML is an optimal method for the treatment of missing data in SEM.30,33 Again, since the χ2 statistic is too sensitive to sample size,34 model fit was assessed using RMSEA, CFI, and TLI. Acceptable cutoffs for model fit were as follows: RMSEA ≤0.06, normed fit index >0.90, CFI >0.90, TLI >0.90.35

Results

Psychometric Structures and Invariance Analysis

Both pre- and postintervention measurement structures were examined. Constructs, items, factor loadings, model fit indices, and Chronbach's alpha values for the scales are presented in Table 2. Factor loadings for both pre- and postintervention tests showed that the construct structure in Choice, Control, and Change psychosocial measure was invariant over time. Model fit indices for both pre- and post-tests also indicated that the measurement structures were well fitted in the model (RMSEA = 0.041/0.043; CFI = 0.909/0.910; and TLI = 0.901/0.903). The Cronbach's alpha values at both pre- and post-tests indicated that all scales had acceptable internal consistency reliability (alpha values ranged from 0.692 to 0.941).

Mediation Mechanisms in Structural Models

Model fit indices are presented in Table 3. A basic multiple mediator model, placing all mediating variables in between intervention and behavioral outcomes at once (Model a in Fig. 1), had an acceptable fit to data for SSB consumption (with adequate RMSEA = 0.047 and CFI = 0.925 values and a marginal value of TLI = 0.841), but not for WALK or STAIR (boys).

Table 3.

Mediation Models in Choice, Control, and Change Curriculum Intervention Implemented in New York City Middle Schools

| Model | Target behavior | RMSEA (90% CI) | NFI | CFI | TLI | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Basic multiple mediators model | SSB | 0.047 (0.040, 0.054) | 0.901 | 0.925 | 0.841 | 0.28 |

| Purposeful walking | 0.075 (0.068, 0.081) | 0.832 | 0.848 | 0.696 | 0.21 | |

| Purposeful stair climbing—boys | 0.075 (0.064, 0.084) | 0.801 | 0.836 | 0.689 | 0.26 | |

| (b) Conceptual framework of the Choice, Control, and Change | SSB | 0.057 (0.051, 0.064) | 0.849 | 0.874 | 0.763 | 0.24 |

| Purposeful walking | 0.069 (0.063, 0.076) | 0.841 | 0.859 | 0.736 | 0.20 | |

| Purposeful stair climbing—boys | 0.069 (0.059, 0.079) | 0.811 | 0.851 | 0.729 | 0.22 | |

| (c) Alternative SCT and SDT model | SSB | 0.042 (0.035, 0.049) | 0.908 | 0.935 | 0.872 | 0.27 |

| Purposeful walking | 0.062 (0.056, 0.069) | 0.876 | 0.894 | 0.788 | 0.22 | |

| Purposeful stair climbing—boys | 0.065 (0.056, 0.075) | 0.827 | 0.867 | 0.755 | 0.26 | |

| (d) Alternative SCT/SDT and goal intention model | SSB | 0.044 (0.037, 0.051) | 0.905 | 0.932 | 0.869 | 0.27 |

| The final pathways (Fig. 2) | 0.039 (0.032, 0.046) | 0.916 | 0.945 | 0.896 | 0.27 | |

| Purposeful walking | 0.064 (0.057, 0.070) | 0.865 | 0.884 | 0.779 | 0.20 | |

| Purposeful stair climbing—boys | 0.064 (0.055, 0.074) | 0.823 | 0.866 | 0.763 | 0.25 | |

| The final pathways (Fig. 3) | 0.045 (0.035, 0.056) | 0.882 | 0.932 | 0.882 | 0.25 |

SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage consumption; RMSEA (acceptable cutoff: ≤0.06); CI, confidence interval; NFI, normed fit index (acceptable cutoff: >0.90); CFI (acceptable cutoff: >0.90); TLI (acceptable cutoff: >0.90).

Bold represents the best model fit indices.

A model based on the theoretical framework of the Choice, Control, and Change curriculum (Model b in Fig. 1) generated unacceptable fit indices for all three behaviors. Models (c) and (d) generated acceptable model fit indices for SSB consumption, but not for WALK or STAIR (boys). Using regression coefficients and covariance comparisons from Models (c) and (d), improved models were identified for SSB consumption and STAIR (boys), but not for WALK.

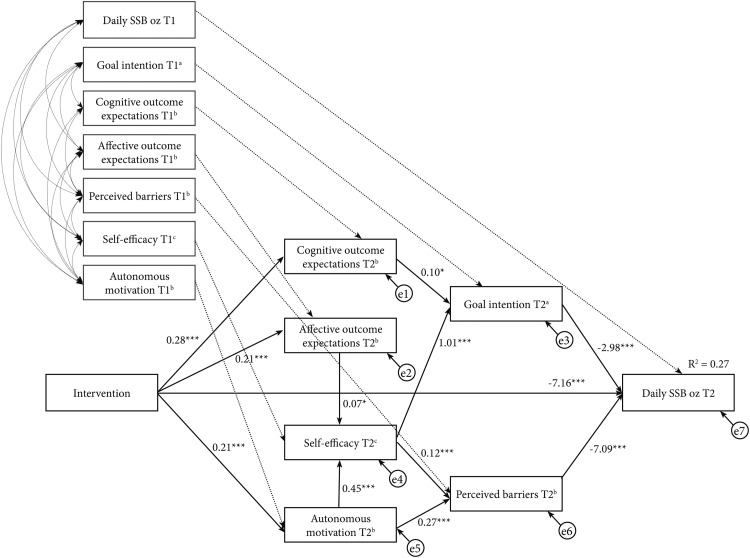

The final models with best fit indices for SSB consumption and STAIR (boys) are illustrated in Figures 2 and 3. Unstandardized regression coefficients are shown on the diagram. Related to SSB consumption (Fig. 2), the intervention positively affected cognitive outcome expectations, affective outcome expectations, and autonomous motivation (regression coefficients ranged from 0.21 to 0.28; p < 0.001), and then self-efficacy, goal intention, and perceived barriers mediated these intervention effects and in turn decreased daily SSB consumption. The intervention also had a direct effect on behavior by decreasing 7.16 ounces of daily SSB consumption (p < 0.001). This final model explained 27% of the variance in SSB consumption.

Figure 2.

The final mediator model for sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) consumption in the Choice, Control, and Change curriculum. T1 represents pretest and T2 represents post-test scores. Bold arrows and numbers represent significant regression coefficients. e1–e7 are error terms. The unit of daily SSB consumption is ounces (oz). Response options: (a) 1 = will not do it within the next 6 months, 2 = will try within the next 6 months, 3 = plan to do it in a month or so, 4 = currently doing it for past 1–6 months, and 5 = have been doing it for over past 6 months; (b) 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = uncertain, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree; and (c) 1 = not sure, 2 = a little sure, 3 = somewhat sure, and 4 = very sure. Scores were coded in a way that higher scores always indicate more desirable for all psychosocial determinants. To enhance clarity of the figure, covariance among T2 variables is not reported. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001.

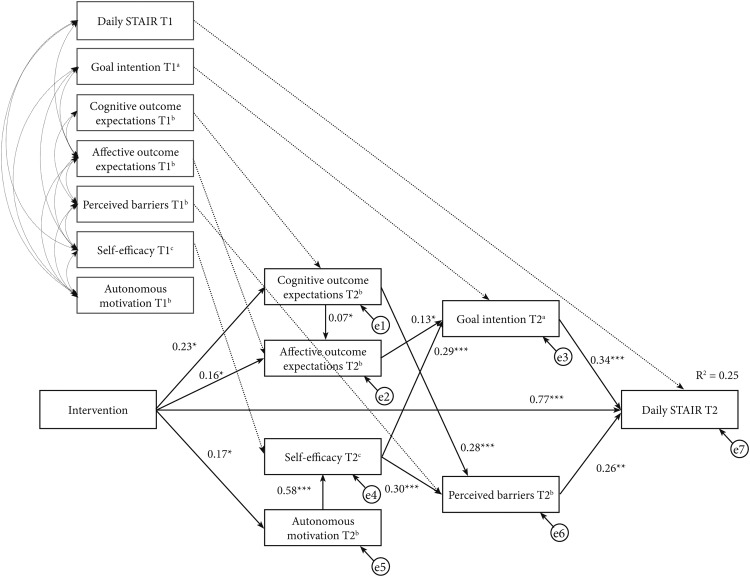

Figure 3.

The final mediator model for purposeful stair climbing activity (STAIR) among boys in the Choice, Control, and Change curriculum. T1 represents pretest and T2 represents post-test scores. Bold arrows and numbers represent significant regression coefficients. e1–e7 are error terms. The unit of daily STAIR is flights: a flight of stairs is going up one floor in a building, such as from the first to the second floor. Response options: (a) 1 = will not do it within the next 6 months, 2 = will try within the next 6 months, 3 = plan to do it in a month or so, 4 = currently doing it for past 1–6 months, and 5 = have been doing it for over past 6 months; (b) 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = uncertain, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree; and (c) 1 = not sure, 2 = a little sure, 3 = somewhat sure, and 4 = very sure. Scores were coded in a way that higher scores always indicate more desirable for all psychosocial determinants. To enhance clarity of the figure, covariance among T2 variables is not reported. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

For STAIR (boys; see Fig. 3), similar, but slightly different, pathways were found. The intervention positively influenced cognitive outcome expectations, affective outcome expectations, and autonomous motivation (regression coefficients ranged from 0.16 to 0.23; p < 0.05), and then self-efficacy, goal intention, and perceived barriers mediated these effects and increased daily purposeful stair climbing activity. The intervention also had a direct effect on boys' daily stair climbing by 0.77 flight per day (p < 0.001). This final model explained 25% of the variance in stair climbing activity among boys.

Discussion

Mediating mechanisms of psychosocial determinants in the Choice, Control, and Change on reducing SSB consumption and increasing purposeful stair climbing activity (STAIR) among boys were identified in urban middle schools.

The results indicated that the relationships among variables originally hypothesized in the conceptual framework of the Choice, Control, and Change25 (Fig. 1, Model b) did not fit well to the data, but a new alternative model was identified with significant mediating pathways. In this model (Fig. 1, Model d), goal intention and reduced perceived barriers were proximal psychosocial determinants of behavioral changes. Cognitive outcome expectations, affective outcome expectations, self-efficacy, and autonomous motivation indirectly influenced SSB consumption and STAIR (boys) behaviors, but through slightly different mechanisms.

Cognitive outcome expectations and self-efficacy directly influenced goal intention in changing the SSB consumption, while affective outcome expectations and self-efficacy were direct influencers for goal intention in increasing STAIR among boys in this study. Autonomous motivation helped students improve self-efficacy for both SSB consumption and STAIR behaviors and further reduce perceived barriers. As seen in Figures 2 and 3, reduced perceived barriers had a larger impact on reducing SSB consumption than the pathway through the goal intention, while for STAIR behaviors among boys, the goal intention had a larger impact on behavioral change than through the reduced perceived barriers.

SSB consumption has been recognized as a contributor to excessive calorie intakes among school-aged children and adolescents.8,36–40 Determining significant mediators and effective strategies to motivate school-aged children and adolescents to reduce SSB consumption would be a critical part of obesity prevention in these age groups. To date, only one intervention study has examined the mediation mechanisms of psychosocial determinants of SSB consumption.8 Attitude and habit strength were significant mediators of the intervention effect among boys on SSB behavior change in the Dutch Obesity Intervention in Teenagers (DOiT) study.8 The other psychosocial determinants, subjective norm and perceived behavioral control, did not mediate the SSB behavior change. Attitude in the DOiT study and affective outcome expectations in the current study were the significant mediators of SSB behavior change, and affective outcome expectations were further mediated by self-efficacy and goal intention in our study.

As seen in Table 2, questions capturing affective outcome expectations in our study included “I believe drinking lots of sweetened beverages is satisfying/is cool/is important to me.” One possible explanation is that beverage companies often use pop culture celebrities and graphic designs to appeal to teenagers, and our lesson on advertisement analysis might have influenced the participants to no longer think that drinking SSBs is cool or important to them. Similar to our study, to improve students' attitude/knowledge/awareness, the DOiT program used information on the health consequences of excessive SSB consumption and clandestine advertising.8 Similar strategies to influence students' affective outcome expectations are strongly encouraged for interventions.

The current study revealed that a combination of cognitive outcome expectations, affective outcome expectations, self-efficacy, and autonomous motivation increased goal intention, which in turn partially decreased students' daily SSB consumption. While the DOiT study showed a gender difference in its SSB findings, the current study did not find any interaction effect between the intervention and gender. Further studies are warranted to confirm these findings and to determine whether or not gender-specific strategies are needed.

Studies reviewing mediating mechanisms of intervention studies3,10 have indicated that to date, more mediators related to physical activity have been found to be significant in youth. Among the mediators, self-efficacy has been the most significant mediator of increasing physical activity among children and adolescents.9,15,22 Enjoyment,15 autonomous motivation,23 and intentions23 were also significant mediators. Findings of the current study were consistent with those reported by other studies. However, in the current study, purposeful walking or stair climbing was targeted as a means of increasing physical activity, while other studies have focused on physical education or school environment changes.9,15,23 Different strategies may apply for different intensities or types of physical activity promotions.

In the current study, the Choice, Control, and Change intervention did not directly impact students' perceived barriers, but when students felt that they have self-regulatory control over the barriers and felt confident overcoming the barriers, meaning that they had high autonomous motivation and self-efficacy, they reduced their perceived barriers and eventually reduced their SSB consumption or increased daily stair climbing activity. It should be noted that increasing self-efficacy or autonomous motivation alone did not directly impact behavioral change in the current study. Addressing specific barriers and how to overcome those barriers through self-regulation (or self-directed action) skills might have been the key factors to motivating behavioral changes in our participants. As shown in Table 2, self-efficacy measured students' confidence in specific situations, while autonomous motivation measured students' overall competence and feelings of ability to self-regulate their behaviors.

Our results indicate that the intervention helped students to gain autonomous motivation with goal-setting and self-regulation skills, which improved confidence of changing behaviors in specific situations, which in turn increased goal intention and reduced perceived barriers to achieving the goal. Strategies such as goal setting, self-regulation skills, and personal pledges are recommended to facilitate this process. In the Choice, Control, and Change curriculum, students also learned how to use pedometers and track their step counts every day. Even though students' step count data were probably unreliable, we strongly believe that it motivated students to increase their walking and stair climbing activities.

The mediators in the current study only explained 27% of the variance in SSB consumption and 25% of the variance in STAIR behavior. Other potential mediating variables should be further explored as the majority of the variance in behavioral change has not been determined. In addition, investigating socio-ecological factors such as environmental variables or parental behaviors that may explain variance in students' behavioral outcomes is warranted.

Limitations of the current study include self-reported measurement and the absence of weight status measurement. It would have been more valuable to see to what extent the intervention effects on mediators and behaviors contributed to weight change. Despite the self-report limitation, the instrument showed adequate internal consistency and invariance factor structures over time. Using path analysis with an SEM method was likely to reduce the effects of measurement errors compared with conventional regression mediation analysis steps. In addition, this study was conducted in an urban setting with a low-income predominantly minority population. Therefore, further research is needed to confirm whether or not significant mediators in this study are consistently associated with behavior change in different settings and populations. Finally, causality cannot be inferred from the mechanisms described in the current study since all psychosocial determinants and behaviors have been assessed at the same time.

In conclusion, particular psychosocial mediating mechanisms of reducing SSB consumption and increasing physical activity by purposefully climbing more stairs (only for boys) were determined. We recommend behavioral change strategies that were used in the Choice, Control, and Change curriculum. When food and physical activity environment modification is not feasible in an intervention design, encouraging self-efficacy and autonomous motivation to overcome perceived barriers is also recommended. The Choice, Control, and Change curricular components that likely influenced outcome expectations (both cognitive outcome expectations and affective outcome expectations) consisted of providing information on the current food and activity environment, analyzing advertisements for unhealthy food items on TV, learning health consequences of unhealthy eating behaviors, benefits of healthy eating and physical activity behaviors, and reading an engaging story with characters similar to our target population. The curricular components that likely influenced students' self-efficacy, autonomous motivation, and goal intentions were goal-setting and self-regulation skills, which included discussions on tracking progress on action goals and students helping each other develop strategies for successful change. Additionally, to address autonomous motivation, toward the end of the curriculum, students made pledges to continue healthful choices as part of their personal policies. Since constructs are likely influenced by different intervention strategies,33 reporting on specific strategies that address specific mediators and how they are incorporated into interventions will greatly improve both intervention development and outcome evaluation studies in the future.

Acknowledgment

This project was supported by R25 RR20412, Science Education Partnership Award, National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Flegal KM. Prevalence of Obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief 2015:1–8 [PubMed]

- 2.Kremers SP, Visscher TL, Seidell JC, et al. Cognitive determinants of energy balance-related behaviours: Measurement issues. Sports Med 2005;35:923–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cerin E, Barnett A, Baranowski T. Testing theories of dietary behavior change in youth using the mediating variable model with intervention programs. J Nutr Educ Behav 2009;41:309–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gortmaker S, Peterson K, Wiecha J, et al. Reducing obesity via a school-based interdisciplinary intervention among youth: Planet Health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1999;153:409–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haerens L, Cerin E, Deforche B, et al. Explaining the effects of a 1-year intervention promoting a low fat diet in adolescent girls: A mediation analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2007;4:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh A, Chin A Paw M, Brug J, Van Mechelen W. Short-term effects of school-based weight gain prevention among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2007;161:565–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma M. Dietary education in school-based childhood obesity prevention programs. Adv Nutr 2011;2:207S–216S [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chin A Paw M, Singh A, Brug J, van Mechelen W. Why did soft drink consumption decrease but screen time not? Mediating mechanisms in a school-based obesity prevention program. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2008;5:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dishman R, Motl R, Saunders R, et al. Self-efficacy partially mediates the effect of a school-based physical-activity intervention among adolescent girls. Prev Med 2004;38:628–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Stralen MM, Yildirim M, te Velde SJ, et al. What works in school-based energy balance behaviour interventions and what does not? A systematic review of mediating mechanisms. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011;35:1251–1265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baranowski T, Anderson C, Carmack C. Mediating variable framework in physical activity interventions. How are we doing? How might we do better? Am J Prev Med 1998;15:266–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baranowski T, Lin LS, Wetter DW, Resnicow K, Hearn MD. Theory as mediating variables: Why aren't community interventions working as desired? Ann Epidemiol 1997;7:S89–S95 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baranowski T, Cerin E, Baranowski J. Steps in the design, development and formative evaluation of obesity prevention-related behavior change trials. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2009;6:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reynolds KD, Yaroch AL, Franklin FA, Maloy J. Testing mediating variables in a school-based nutrition intervention program. Health Psychol 2002;21:51–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dishman R, Motl R, Saunders R, et al. Enjoyment mediates effects of a school-based physical-activity intervention. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2005;37:478–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baranowski T, Cullen KW, Baranowski J. Psychosocial correlates of dietary intake: Advancing dietary intervention. Annu Rev Nutr 1999;19:17–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacKinnon DP. Analysis of mediating variables in prevention and intervention research. NIDA Res Monogr 1994;139:127–153 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kremers SP. Theory and practice in the study of influences on energy balance-related behaviors. Patient Educ Couns 2010;79:291–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reynolds KD, Bishop DB, Chou CP, Xie B, Nebeling L, Perry CL. Contrasting mediating variables in two 5-a-day nutrition intervention programs. Prev Med 2004;39:882–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Noia J, Prochaska JO. Mediating variables in a transtheoretical model dietary intervention program. Health Educ Behav 2010;37:753–762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taymoori P, Lubans DR. Mediators of behavior change in two tailored physical activity interventions for adolescent girls. Psychol Sport Exerc 2008;9:605–619 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haerens L, Cerin E, Maes L, et al. Explaining the effect of a 1-year intervention promoting physical activity in middle schools: A mediation analysis. Public Health Nutr 2007;11:501–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chatzisarantis NL, Hagger MS. Effects of an intervention based on self-determination theory on self-reported leisure-time physical activity participation. Psychol Health 2009;24:29–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diep CS, Chen TA, Davies VF, et al. Influence of behavioral theory on fruit and vegetable intervention effectiveness among children: A meta-analysis. J Nutr Educ Behav 2014;46:506–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Contento IR, Koch PA, Lee H, Calabrese-Barton A. Adolescents demonstrate improvement in obesity risk behaviors after completion of choice, control & change, a curriculum addressing personal agency and autonomous motivation. J Am Diet Assoc 2010;110:1830–1839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gray HL, Burgermaster M, Tipton E, et al. Intraclass correlation coefficients for obesity indicators and energy balance-related behaviors among New York City Public Elementary Schools. Health Educ Behav 2016;43:172–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Little RJA. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J Am Stat Assoc 1988;83:1198–1202 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gray HL, Contento IR, Koch PA. Linking implementation process to intervention outcomes in a middle school obesity prevention curriculum, ‘Choice, Control and Change’. Health Educ Res 2015;30:248–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lance CE, Butts MM, Michels LC. The sources of four commonly reported cutoff criteria: What did they really say? Organ Res Methods 2006;9:202–220 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. The Guilford Press: New York, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zoellner J, Estabrooks PA, Davy BM, et al. Exploring the theory of planned behavior to explain sugar-sweetened beverage consumption. J Nutr Educ Behav 2012;44:172–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Young HM, Lierman L, Powell-Cope G, et al. Operationalizing the theory of planned behavior. Res Nurs Health 1991;14:137–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Motl RW, Dishman RK, Ward DS, et al. Examining social-cognitive determinants of intention and physical activity among black and white adolescent girls using structural equation modeling. Health Psychol 2002;21:459–467 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dishman RK, Saunders RP, Felton G, et al. Goals and intentions mediate efficacy beliefs and declining physical activity in high school girls. Am J Prev Med 2006;31:475–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu L-t, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling 1999;6:1–55 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grimm GC, Harnack L, Story M. Factors associated with soft drink consumption in school-aged children. J Am Diet Assoc 2004;104:1244–1249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harrington S. The role of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in adolescent obesity: A review of the literature. J Sch Nurs 2008;24:3–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mesirow MS, Welsh JA. Changing beverage consumption patterns have resulted in fewer liquid calories in the diets of US Children: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2010. J Acad Nutr Diet 2014;115:559–566.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pereira MA. The possible role of sugar-sweetened beverages in obesity etiology: A review of the evidence. Int J Obes 2006;30:S28–S36 [Google Scholar]

- 40.van de Gaar VM, Jansen W, van Grieken A, et al. Effects of an intervention aimed at reducing the intake of sugar-sweetened beverages in primary school children: A controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2014;11:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]