Abstract

We conducted a comprehensive, multiphase laboratory evaluation of the Anthrax BioThreat Alert® test strip, a lateral flow immunoassay (LFA) for the rapid detection of Bacillus anthracis spores. The study, conducted at 2 sites, evaluated this assay for the detection of spores from the Ames and Sterne strains of B. anthracis, as well as those from an additional 22 strains. Phylogenetic near neighbors, environmental background organisms, white powders, and environmental samples were also tested. The Anthrax LFA demonstrated a limit of detection of about 106 spores/mL (ca. 1.5 × 105 spores/assay). In this study, overall sensitivity of the LFA was 99.3%, and the specificity was 98.6%. The results indicated that the specificity, sensitivity, limit of detection, dynamic range, and repeatability of the assay support its use in the field for the purpose of qualitatively evaluating suspicious white powders and environmental samples for the presumptive presence of B. anthracis spores.

The authors conducted a comprehensive, multiphase laboratory evaluation of the Anthrax BioThreat Alert® test strip, a lateral flow immunoassay (LFA) for the rapid detection of Bacillus anthracis spores. The study, conducted at 2 sites, evaluated this assay for the detection of spores from the Ames and Sterne strains of B. anthracis, as well as those from an additional 22 strains. The results indicated that the specificity, sensitivity, limit of detection, dynamic range, and repeatability of the assay support its use in the field for the purpose of qualitatively evaluating suspicious white powders and environmental samples for the presumptive presence of B. anthracis spores.

Bacillus anthracis is a rod-shaped, spore-forming, gram-positive, nonhemolytic, facultative anaerobic microorganism.1-5 In nutrient-scarce environments, such as alkaline soil with high calcium ion content, it is found as a stable, nonreplicating endospore that resists desiccation and can withstand extremes in temperature, pressure, ionizing radiation, chemical agents, and pH.4,6-8 Under favorable conditions, such as a mammalian host, the spores germinate and begin synthesizing capsule and toxins.9 In the laboratory, B. anthracis grows rapidly on sheep blood agar3,4,10 and is identified by colony morphology, capsule staining, lack of hemolysis, susceptibility to penicillin, and lysis by the species-specific gamma bacteriophage.1,3,4,6 B. anthracis belongs to the Bacillus cereus group, a group that also includes B. cereus, B. thuringiensis, B. mycoides, B. pseudomycoides, and B. weihenstephanensis. While these organisms share similar structures and physiologies, they differ in their plasmid-associated virulence factors. B. anthracis has 2 plasmids, designated pXO1 and pXO2.1,2,4,6,11-14 The 3 toxin components, lethal factor (LF), edema factor (EF), and protective antigen (PA), are all encoded by pXO1. The LF is a 90-kDa zinc metalloprotease that inactivates mitogen-activated protein kinase kinases (MAPKK) and interferes with signal transduction.2,3,6,12,15 It also impairs the function of B cells, T cells, and dendritic cells.12,16 EF is an 89-kDa adenylate cyclase that causes an elevation of intracellular cAMP and a release of chloride ions and water from the cell, leading to localized swelling in the surrounding tissue.2,3,6,12,15 LF and EF must bind to PA in order to enter a susceptible cell. PA binds to cell receptors.2,3,6,12,15 In mammals, these receptors are tumor endothelial marker 8 (TEM8) and capillary morphogenesis factor 2 (CMG2).6,12 Upon cleavage of an N-terminal fragment, PA forms a heptameric channel allowing EF and LF to flow into the cell. EF and LF specifically target host macrophages and neutrophils.6 pXO2 contains a 5-gene operon (capBCADE), which encodes for the synthesis of a negatively charged poly-D-glutamic acid capsule that inhibits phagocytosis of vegetative cells by host macrophages.2,4,6,12 While pXO1 and pXO2 are associated with B. anthracis, similar plasmids have been identified in B. cereus strains cultured from specimens collected from dead animals or humans who presented with anthrax-like symptoms.4,6 Strains lacking either pXO1 or pXO2, or both plasmids, are either avirulent or exhibit attenuated virulence.17

Anthrax, caused by B. anthracis, is primarily a disease of herbivores, although all mammals, including humans, are susceptible.18,19 The majority of human cases are cutaneous and result from occupational exposure.3,14,20 The name is derived from the Greek word anthracites, meaning coal-like, which refers to the discolored, necrotic tissue (ie, eschar) seen in the cutaneous form of the disease.1 While not generally life-threatening, left untreated, the mortality rate for cutaneous anthrax can approach 20%.12 In addition to usually painless eschars, patients may also experience fever, edema, and other systemic symptoms.12,21,22 In the 2001 anthrax attacks in the United States, there were 22 total cases, of which 11 were cases of cutaneous anthrax.22,23

Gastrointestinal (GI) anthrax results from the ingestion of spores in vehicles such as contaminated meat. GI anthrax falls into 2 categories: oropharyngeal and intestinal. In both forms, there is a 1- to 6-day incubation period following ingestion. Oropharyngeal anthrax patients present with elevated temperature (above 39°C), sore throat, dysphagia, neck swelling, and lymph node enlargement that can constrict the airway and make breathing difficult. Intestinal anthrax is caused by an infection of the stomach or bowel wall and can lead to ulceration of the ileum and cecum. It should not be mistaken for the nonulcerative hemorrhagic lesions that can occur during anthrax septicemia. Nausea, anorexia, elevated body temperature, severe abdominal pain, and bloody diarrhea are frequently observed symptoms and signs. In both cases, aggressive treatment with antibiotics such as penicillin or tetracycline is recommended.10 Mortality rates range from 25% to 60% in the absence of prompt intervention.12

The most severe form is biphasic respiratory or inhalation anthrax, also known as wool sorter's disease, which without treatment can result in death as early as 1 to 7 days postexposure.3,12,14,24-26 The diagnosis of inhalation anthrax presents a challenge because initial symptoms, including fever, malaise, and a dry cough, are nonspecific and resemble influenzalike symptoms, although chest X-rays typically show a widening of the mediastinum caused by hemorrhage and necrosis.3,12,14,21,22,24 A direct Gram stain of patient tissue or fluids can be performed, and suspicious results should immediately be reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).3 Spores, which typically measure between 1 and 2 microns in diameter, are of the ideal size to cause inhalation-associated infections.27 Following inhalation, spores impinge on the lower respiratory mucosa. In the lungs, alveolar macrophages phagocytize the spores and then carry them to the mediastinal and tracheobronchial lymph nodes. During transport, spores germinate with concomitant synthesis of the toxins and capsule.1,3,12,15,25 Following a 2- to 3-day period, during which patients sometimes experience transient improvement,14 there is a release of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin-1 (IL-1), precipitating a sudden onset of respiratory distress, orthopnea, stridor, tachypnea, high fever, chills, and diaphoresis.3,14,28 Recommended postexposure prophylaxis for inhalation anthrax is 60 days of treatment with ciprofloxacin or doxycycline, although other antibiotics, including levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, amoxicillin, or penicillin VK, may be used as well.3,14,22-24 Mechanical ventilation and other palliative care may also be necessary. In the 2001 US anthrax attacks, there were 11 confirmed cases of inhalation anthrax with 5 deaths and an average incubation period of 4 days.21-23,29,30

Both the United States and the former Soviet Union actively investigated the use of B. anthracis as an offensive biological weapon; Iraq has admitted to such work as well.27 The Federal Select Agent Program classifies B. anthracis as a Tier 1 agent due, in part, to its ease of dispersal and high mortality rate, although anthrax is not transmissible from person to person.14 The ID50 for humans is estimated to be between 8,000 and 20,000 spores.3,14 Peters and Hartley31 calculated that the LD1 could be as low as 1 to 3 spores, which would help explain rare and sporadic cases of anthrax among people who had only minimal contact with known contaminated environments; in a mass exposure event where large numbers of people may be affected, the LD1 is as important as ID50 in determining probability of infection.

A biological attack involving B. anthracis would most likely involve the aerosol dispersal of hydrophobic spores.7,14,20,30 During the 2001 anthrax attack, many public health laboratories and first responders were inundated with suspicious white powder samples for testing because of public fear and panic. The large number of samples overwhelmed the CDC Laboratory Response Network (LRN) laboratories and prevented them from functioning at their optimal level.32 When first responders encounter unknown white powders in the field, it is important to quickly evaluate them for the presence of biological threat agents to support the appropriate public safety actions, including evacuation, facility closure to prevent additional exposures, decontamination of potentially exposed individuals, sample collection for law enforcement and public health purposes, expedited sample transfer to CDC LRN laboratories for immediate testing, and containment of materials as appropriate to prevent secondary dissemination. In order to provide first responders with the appropriate tools to carry out their mission, there is a critical need to develop, evaluate, and validate rapid screening tools for testing suspicious white powders for the presence of biological threat agents.

The purpose of the present study was to determine the sensitivity, specificity, reproducibility, and limitations of a Lateral Flow Immunoassay (LFA) Anthrax BioThreat Alert® Test Strip (Tetracore®, Inc., Rockville, MD) that can be used in the field to screen for the presence of B. anthracis spores. The goal of this study was to evaluate assay performance, including the likelihood of false-negative results (assay is negative, but the analyte is present at a concentration above the limit of detection [LOD]), false-positive results (assay is positive, but the target analyte is not present in the sample), and robustness and reproducibility of this LFA so that appropriate and effective decisions can be made by first responders to support public safety actions while avoiding unnecessary fear, panic, and costly disruptions to society.

This study was designed and executed through an interagency collaboration with participation from subject matter experts from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Science and Technology Directorate (S&T), DHS Chief Readiness Support Officer (CRSO), the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response/Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (ASPR/BARDA), HHS Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Department of Justice (DOJ) Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), US Department of Agriculture (USDA), HHS Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN), FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH), DHS US Secret Service (USSS), and others.

Materials and Methods

Anthrax BioThreat Alert® Test Strips (catalog number TC-8004-025) and Rapid BioThreat Alert Reader MX (catalog number TC-3005-001) were obtained from Tetracore, Inc. (Rockville, MD). All testing with virulent B. anthracis spores was done at the Zoonoses and Select Agent Laboratory, Bacterial Special Pathogens Branch, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, CDC, Atlanta, GA. Spores of B. anthracis Ames and the inclusivity organisms were prepared and tested at CDC. Five replicates of each sample were tested. All testing using the avirulent Sterne vaccine strain of B. anthracis, near neighbors, environmental background organisms, and white powders were performed at Omni Array Biotechnology, Rockville, MD. Each sample was tested by 5 different operators at Omni Array Biotechnology.

Spores from near neighbors were prepared and stored at 4°C until use, then analyzed by members from DHS S&T and FDA CFSAN according to a standard protocol provided by the manufacturer. Anthrax LFA results were read both visually and with the BioThreat Alert Reader MX according to directions provided by the manufacturer—that is, between 15 and 30 minutes after adding the sample (150 μL) to the lateral flow strip. Samples with readings of <200 were considered negative, while test strips that did not develop a control line were noted, which required repeat testing of the sample. The BioThreat Alert Reader MX measures the ratio of absorbing light intensity and incident light on the surface of the lateral flow strip. As an example, if the incident light intensity was 100 cd/m2 and 0.25 cd/m2 is absorbed on the surface, the resulting ratio (ie, 0.0025), converted into a BioThreat Alert Reader MX value by the instrument, is expressed as the numerical value without units.

The study comprised multiple phases of testing. BioThreat Alert (BTA) buffer, the proprietary assay buffer supplied in the kit, was used as a negative control. Spores of the Sterne strain of B. anthracis at a concentration of 107/mL were used as positive controls at both test sites. Inclusivity strains of B. anthracis were typed using Multiple Locus Variable–number Tandem Repeat Analysis (MLVA) and subjected to strain characterization, plasmid profile analysis, and 16S typing.

Spore Preparation

Strains of B. anthracis were inoculated onto sheep blood agar (SBA) plates and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. Sporulation media (3 g Tryptone, 6 g Peptone, 3 g Yeast Extract, 0.1% 1.0 M Manganese (II) Chloride [0.1 g Manganese (II) Chloride 4-Hydrate, endotoxin-free (ETF) water to 100 mL], 15 g Agar, ETF water to 1 L) slants were prepared and inoculated with cells from the overnight cultures. Slants were incubated at 30°C for 5 to 7 days; then growth was harvested by washing with 5 mL sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and added to 35 mL sterile PBS in a 50 mL conical tube. The suspensions were heated in a 65°C water bath for 30 minutes to kill any remaining vegetative cells. Tubes were inverted frequently during the 30-minute incubation period. Spore suspensions were then cooled to room temperature and centrifuged at 3,400 RPM for 20 minutes to pellet spores and remove cellular debris. Pellets were resuspended in 30 mL sterile PBS and vortexed for 30 seconds. The spore suspensions were centrifuged at 3,400 RPM at 5°C for 20 minutes. Supernatant was decanted and pellet resuspended in 5 mL sterile PBS and transferred to a 15-mL tube for storage at 4°C. Spore concentrations were determined by serial dilution and plating on SBA plates after incubation for 12 to 18 hours at 37°C. Test dilutions of spore suspensions were based on plate counts. Presence of spores was confirmed by examination of wet mounts using phase contrast microscopy, and the preparation yielded predominantly homogenous spore suspension with little or no clumping.

Environmental Filters

Thirty filters that had been subjected to 24 hours of environmental aerosol collection were extracted by shaking with PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (PBST) and the extracts pooled. The protein concentration of the extract was adjusted to 6 μg protein/μL with PBST containing 1% BSA (PBSTB) and then shipped to the testing site.

Phase 1: Limit of Detection and Repeatability Study

The dynamic range of the Anthrax LFA was determined using spores of B. anthracis Ames strain and Sterne strain. Spores were prepared in PBS, then diluted 1:1 with BTA buffer (per manufacturer instructions) to achieve concentrations ranging from 103 cfu/mL to 109 cfu/mL. Following dilution, 150 μL of each spore concentration was added to lateral flow strips. Each concentration was tested 5 times by a single operator. The lowest concentration of Sterne strain spores that yielded positive results in 5 out of 5 lateral flow strips was further tested for repeatability with different operators. Each operator tested 24 replicates, and the 95% confidence level of detection at this concentration was calculated using the total test results from 120 replicate samples tested.

Phase 2: Inclusivity Panel

In order to determine whether this assay could detect spores from diverse strains, spores from 22 (18 fully virulent) B. anthracis strains (Table 1) were prepared as described above and diluted in BTA buffer to a final concentration of 109 to 1010 spores/mL (4 logs above LOD determined with Sterne strain spores) and vortexed. A 150-μL sample volume was added to each test strip. Each strain was tested 5 times by a single operator to understand the sensitivity, reproducibility, and robustness of the assay.

Table 1.

Inclusivity Strains of B. anthracis. Strains lacking a plasmid are not typeable using MLVA-8.

| S.No. | Strain ID | MLVA-8 Clade | Genotype | pXO1 | pXO2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | K8960; 2011756210 | A1.a | GT7 | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | K1256; 2000031657 | A1.a | GT10 | Yes | Yes |

| 3 | K9002; 2000031650 | A1.b | GT23 | Yes | Yes |

| 4 | K7948; A0264; 2000031659 | A1.b | GT28 | Yes | Yes |

| 5 | K5135; 2000031648 | A2 | GT29 | Yes | Yes |

| 6 | K1244; 2008724773 | A3 | Yes | No | |

| 7 | K2802; 2000031652 | A3 | GT68 | Yes | Yes |

| 8 | K4516; 2000031654 | A3.a | GT51 | Yes | Yes |

| 9 | AO467; 2002013028 | A3.a | GT91 | Yes | Yes |

| 10 | Ames; 2000031656 | A3.b | GT62 | Yes | Yes |

| 11 | Ames BclA-; 2004017841 | A3.b | GT62 | Yes | Yes |

| 12 | K7222; 2000031653 | A4 | GT69 | Yes | Yes |

| 13 | K4596; 2000031666 | A4 | GT77 | Yes | Yes |

| 14 | AO337; 2008724774 | A4 | GT74 | Yes | Yes |

| 15 | K2762; 2000031651 | B2 | GT80 | Yes | Yes |

| 16 | K8101; 2008724769 | B1 | GT82 | Yes | Yes |

| 17 | CDC 240; 2002013094 | C | 133 | Yes | Yes |

| 18 | Pasteur; 2000031242 | A1.a | No | Yes | |

| 19 | Sterne; K7816; 2000031075 | A3.b | Yes | No | |

| 20 | STI Vaccine; 2000031131 | Yes | No | ||

| 21 | Tsiankovskii-I; 2000031560 | Yes | Yes | ||

| 22 | Carbosap; 2008724809 | Yes | Yes |

Phase 3: Near Neighbor Panel

Spores were prepared from 34 phylogenetic near neighbors (Table 2) of B. anthracis. The spores were prepared in PBS, then diluted 1:1 in BTA buffer to a concentration of 108 to 109 spores/mL (≥3 logs above Sterne strain LOD) and vortexed, followed by addition of a 150-μL sample volume to each test strip. Each near neighbor was tested once by each of 5 different operators.

Table 2.

B. anthracis Near Neighbor Panel

| S.No. | Species | Strain IDs | Genome Homology to B. anthracis |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bacillus cereus | E33L/ZK; 2002734581 | 98% |

| 2 | Bacillus cereus | ATCC 4342; BACI083; NRS 731; 2000031470 | 98% |

| 3 | Bacillus cereus | FRI-48; FM1 | 98% |

| 4 | Bacillus cereus | 03BB102; 2002734580 | 98% |

| 5 | Bacillus cereus | 03BB108; 2002734374 | 98% |

| 6 | Bacillus cereus | G9241; BACI23; 2002734376 | 98% |

| 7 | Bacillus cereus | FRI-13; D17; 2000031475 | 98% |

| 8 | Bacillus cereus | FRI-42; S2-8; 2000031471 | 98% |

| 9 | Bacillus cereus | FRI-41; 3A; BACI228; 2000031473 | 98% |

| 10 | Bacillus coagulans | ATCC 7050; BACI020; NRS 609; NCIB 9365; NCTC 10334; CCUG 7417; DSM 1; LMG 6326; CIP 66.25 | NA |

| 11 | Bacillus megaterium | ATCC 14581; 7051; CCUG 1817, CIP 66.20, DSM 32, LMG 7127, NCIB 9376, NCTC 10342, NRRL B-14308 | |

| 12 | Bacillus mycoides | ATCC 6462; NRS 273; 155; CCUG 26678; CIP 103472; DSM 2048; HAMBI 1827; LMG 7128; NCTC 12974; NRRL B-14779; NRRL B-14811; 2000032765 | |

| 13 | Bacillus thuringiensis | HD 1011; DSM 6074 | 99% |

| 14 | Bacillus thuringiensis | 97-27; BACI230 | 99% |

| 15 | Bacillus thuringiensis | HD 682 | 99% |

| 16 | Bacillus thuringiensis | HD 571; DSM 6080; NRRL HD-571 | 99% |

| 17 | Bacillus thuringiensis subsp Israelensis | HD 1002 | 99% |

| 18 | Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. Kurstaki | HD 1; ATCC 39756; CMCC 1615; DSM 6102 | 99% |

| 19 | Bacillus thuringiensis subspecies Morrisoni | HD 600 | 99% |

| 20 | Bacillus thuringiensis | Al Hakam; BACI229 | 99% |

| 21 | Bacillus cohnii | ATCC 51227; DSM 6307; LMG 16678 | |

| 22 | Bacillus horikoshii | ATCC 700161; DSM 8719; JP277; PN-121; LMG 17946 | |

| 23 | Bacillus litoralis | CIP 108971; DSM 16303; SW-211; KCTC 3898 | |

| 24 | Bacillus macroides (aka Lineola longa; Bacillus sp.) | ATCC 12905; 1741-1b; DSM 54; NCIB 8796; NCIM 2596; NCIM 2812 | |

| 25 | Bacillus psychrosaccharolyticus | ATCC 23296; T25B; DSM 6, NRRL B-3394; CIP 106932; LMG 9580; NRRL NRS-1518 | |

| 26 | Bacillus amyloliquefaciens | ATCC 53495; H | 79% |

| 27 | Brevibacillus brevis | ATCC 8246; NRS 604; 27B; CCM 2050; CIP 52.86; DSM 30; IFO 15304; JCM 2503; NCIB 9372; NCTC 2611; CCUG 7413; CIP 52.86; LMG 7123ATCC 53495; H | 86% |

| 28 | Bacillus cirulans | ATCC 4516; 7; NRS 313; DSM 7257 | NA |

| 29 | Bacillus lentus | ATCC 10841; NRS 1262; 238; DSM 5221; LMG 12359 | NA |

| 30 | Bacillus licheniformis | ATCC 6634; NRS 304 | 79% |

| 31 | Bacillus pumulis | ATCC 700814; GB34 | 79% |

| 32 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. Subtilis | ATCC 6051; Marburg strain; CCUG 163B; CIP 52.65; DSM 10; LMG 7135; NCIB 3610; NRRL B-4219; NRS 1315; NRS 744ATCC 700814; GB34 | 80% |

| 33 | Bacillus subtilis | QST-713 (Bayer) |

Phase 4: Environmental Background Panel

Sixty-one diverse environmental background organisms (Table 3) were inoculated onto agar medium optimal for each organism and incubated under appropriate conditions for 24 to 48 hours. A single, isolated colony was selected and inoculated onto a second plate and incubated for 1 to 6 days, depending on the organism and its growth rate. Plates were then sealed with parafilm and stored at 4°C until use. For testing, several colonies were selected and resuspended in 4 mL BTA, and 150 μL was added to each Anthrax LFA. Each organism was tested once by each of 5 different operators to understand the variability of the assay by identifying any potential cross-reactivity or false-positive results.

Table 3.

Environmental Background Panel

| S.No. | Organism | Strain Name |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acinetobacter calcoaceticus | ATCC 14987; HO-1; NBRC 12552; NCIMB 9205; CIP 66.33; DSM 1139; LMG 1056 |

| 2 | Acinetobacter haemolyticus | ATCC 17906; NCTC 10305; 2446/60; DSM 6962; CIP 64.3; NCIMB 12458 |

| 3 | Acinetobacter radioresistens | ATCC 43998; DSM 6976; FO-1; CIP 103788; LMG 10613; NCIMB 12753 |

| 4 | Aeromonas veronii | ATCC 35622; CDC 140-84 |

| 5 | Bacillus cohnii | ATCC 51227; DSM 6307; LMG 16678 |

| 6 | Bacillus horikoshii | ATCC 700161; DSM 8719; JP277; PN-121; LMG 17946 |

| 7 | Bacillus macroides (aka Lineola longa; Bacillus sp.) | ATCC 12905; 1741-1b; DSM 54; NCIB 8796; NCIM 2596; NCIM 2812; LMG 18474 |

| 8 | Bacillus megaterium | ATCC 14581; 7051; CCUG 1817, CIP 66.20, DSM 32, LMG 7127, NCIB 9376, NCTC 10342, NRRL B-14308 |

| 9 | Bacteroides fragilis | ATCC 23745; ICPB 3498, NCTC l0581 |

| 10 | Brevundimonas diminuta | ATCC 11568; DSM 7234; CCUG 1427, CIP 63.27, LMG 2089, NCIB 9393, NCTC 8545, NRRL B-1496, USCC 1337 |

| 11 | Brevundimonas vesicularis | ATCC 11426; CCUG 2032, LMG 2350, NCTC 10900 |

| 12 | Burkholderia cepacia | ATCC BAA-245; KC1766; LMG 16656; J2315; CCUG 48434; NCTC 13227 |

| 13 | Burkholderia stabilis | 2008724195; LMG 14294; CCUG 34168, CIP 106845, NCTC 13011; ATCC BAA-67 |

| 14 | Chromobacterium violaceum | ATCC 12472; NCIMB 9131; NCTC 9757; CIP 103350; DSM 30191; LMG 1267 |

| 15 | Chryseobacterium gleum | ATCC 29896; CDC 3531; NCTC 10795; LMG 12451; CCUG 22176; CDC 3531 |

| 16 | Chryseobacterium indologenes | ATCC 29897; CDC 3716; NCTC 10796; CCUG 14483; CIP 101026; LMG 8337 |

| 17 | Citrobacter brakii | ATCC 10053 |

| 18 | Citrobacter farmeri | ATCC 31897; FERM-P 5539; AST 108-1 |

| 19 | Clostridium butyricum | CDC 11875; ATCC 19398; NCTC 7423; VPI 3266; CCUG 4217; CIP 103309; DSM 10702; LMG 1217; NCIMB 7423 |

| 20 | Clostridium perfringens | ATCC 12915; NCTC 8359; 3702/49; CIP 106516 |

| 21 | Clostridium sardiniense | ATCC 33455; VPI 2971; DSM 2632; BCRC 14530 |

| 22 | Comamonas testosteroni | ATCC 11996; 567201; FHP 1343; NCIMB 8955; CIP 59.24; NCTC 10698; NRRL B-2611; DSM 50244; LMG 1800; CCUG 1426 |

| 23 | Deinococcus radiodurans | ATCC 35073; NCIMB 13156; UWO 298 |

| 24 | Delftia acidovorans | ATCC 9355; LMG 1801; CCUG 1822; CIP 64.36; NCIMB 9153; NRRL B-783 |

| 25 | Dermabacter hominis | ATCC 49369; DSM 7083; NCIMB 13131; CIP 105144; CCUG 32998; S69 |

| 26 | Enterobacter aerogenes | ATCC 13048; CDC 819-56; NCTC 10006; DSM 30053; CIP 60.86; LMG 2094; NCIMB 10102 |

| 27 | Enterobacter cloacae | ATCC 10699; NCIMB 8151; CCM 1903 |

| 28 | Enterococcus faecalis | ATCC 10100; NCIMB 8644; P-60 |

| 29 | Escherichia coli O157:H7 | ATCC 43895; CDC EDL 933; CIP 106327; O157:H7 |

| 30 | Flavobacterium mizutaii | ATCC 33299; CIP 101122; CCUG 15907; LMG 8340; NCTC 12149; DSM 11724; NCIMB 13409 |

| 31 | Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp. nucleatum | ATCC 25586; CCUG 32989; CIP 101130; DSM 15643; LMG 13131 |

| 32 | Jonesia denitrificans | ATCC 14870; CIP 55.134; NCTC 10816; DSM 20603; CCUG 15532 |

| 33 | Klebsiella oxytoca | ATCC 12833; FDA PCI 114; NCDC 413-68; NCDC 4547-63 |

| 34 | Klebsiella pneumonia subsp. pneumonia | ATCC 10031; FDA PCI 602; CDC 401-68; CIP 53.153; DSM 681; NCIMB 9111; NCTC 7427; LMG 3164 |

| 35 | Kluyvera ascorbata | ATCC 14236; CDC 2567-61; CDC 0408-78; DSM 30109; CCUG 21164; CIP 79.53 |

| 36 | Kluyvera cryocrescens | ATCC 14237; CDC 2568-61; CCUG 544; NCIMB 9139; NCTC 10484 |

| 37 | Kocuria kristinae | ATCC 27570; DSM 20032; NRRL B-14835; CCUG 33026; CIP 81.69; LMG 14215; NCTC 11038 |

| 38 | Lactobacillus plantarum | ATCC BAA-793; LMG 9211; NCIMB 8826 |

| 39 | Listeria monocytogenes | ATCC 7302; BCRC 15329 |

| 40 | Microbacterium sp. | ATCC 15283; MC 100 |

| 41 | Micrococcus lylae | ATCC 27566; CCUG 33027; DSM 20315; NCTC 11037; CIP 81.70; LMG 14218 |

| 42 | Moraxella nonliquefaciens | ATCC 17953; NCDC KC 770; NCTC 7784; CCUG 4863; LMG 1010; BCRC 11071 |

| 43 | Moraxella osloensis | ATCC 10973; CDC Baumann D-10; LMG 987; CCUG 34420 |

| 44 | Myroides odoratus | ATCC 29979; NCTC 11179; LMG 4028; DSM 2802; CIP 105169 |

| 45 | Mycobacterium smegmatis | ATCC 20; NCCB 29027 |

| 46 | Neisseria lactamica | ATCC 23970; CDC A 7515; CCUG 5853; CIP 72.17; DSM 4691; NCTC 10617 |

| 47 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | ATCC 15442; NRRL B-3509; CCUG 2080; DSM 939; CIP 103467; NCIMB 10421 |

| 48 | Pseudomonas fluorescens | ATCC 13525; Migula biotype A; NCTC 10038; DSM 50090; NCIMB 9046; NRRL B-2641; LMG 1794; CIP 69.13; CCUG 1253 |

| 49 | Ralstonia pickettii | ATCC 27511; CCUG 3318; LMG 5942; CIP 73.23; NCTC 11149; DSM 6297; NCIMB 13142; UCLA K-288 |

| 50 | Rhodobacter sphaeroides | ATCC 17024; ATH 2.4.2 |

| 51 | Riemerella anatipestifer | ATCC 11845; CCUG 14215; LMG 11054; MCCM 00568; NCTC 11014; DSM 15868 |

| 52 | Shewanella haliotis (Pseudomonas putrefaciens) | ATCC 49138; AmMS 201; ACM 4733 |

| 53 | Shigella dysenteriae | ATCC 12039; CDC A-2050-52; NCTC 9351 |

| 54 | Sphingobacterium multivorum | ATCC 33613; CDC B5533; NCTC 11343; GIFU 1347 |

| 55 | Sphingobacterium spiritivorum | ATCC 33300; DSM 2582; LMG 8348 |

| 56 | Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus | ATCC 700699; CIP 106414; Mu 50, MRSA |

| 57 | Staphylococcus capitis | ATCC 146; NRRL B-2616; BCRC 15248 |

| 58 | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | ATCC 13637; NCIMB 9203; NCTC 10257; NRC 729; CIP 60.77; DSM 50170; LMG 958; NRRL B-2756 |

| 59 | Streptococcus equinus | ATCC 15351; 7H4; NBRC 12057; IFO 12057 |

| 60 | Streptomyces coelicolor | ATCC 10147; DSM 41007; NIHJ 147; NBRC 3176 |

| 61 | Vibrio cholerae | ATCC 14104; BG29 |

Phase 5a: White Powder Panel

The white powder panel shown in Table 4 is identical to the one that was used to evaluate ricin and abrin LFAs33,34 and a modification of one approved by the Stakeholder Panel on Agent Detection Assays (SPADA) in 2010.35 These materials were evaluated for their ability to affect the performance of the assay. Five milligrams of each of the 26 white powders (Table 4) were suspended (or dissolved) in 500 μL of BTA buffer (final concentration = 10 mg/mL). Each tube was vortexed for 10 seconds. The suspension was allowed to settle for at least 5 minutes, and then 150 μL of the supernatant was removed and added to the Anthrax LFA. Each powder was tested once by each of 5 different operators to understand the variations and robustness of the assay by identifying any inhibition of the internal positive control and potential false-positive reactions.

Table 4.

White Powder Panel

| S.No. | Material | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dipel (Bacillus thuringiensis) | Summerwinds Nursery, Palo Alto, VA |

| 2 | Powdered milk | Raley's Grocery Store, Pleasanton, CA |

| 3 | Powdered coffee creamer | Raley's Grocery Store, Pleasanton, CA |

| 4 | Powdered sugar | Raley's Grocery Store, Pleasanton, CA |

| 5 | Talcum powder | Raley's Grocery Store, Pleasanton, CA |

| 6 | Wheat flour | Van's, Livermore, CA |

| 7 | Soy flour | Van's, Livermore, CA |

| 8 | Rice flour | Ranch 99, Pleasanton, CA |

| 9 | Baking soda | Target Stores, Livermore, CA |

| 10 | Chalk dust | Target Stores, Livermore, CA |

| 11 | Brewer's yeast | GNC Stores, Livermore, CA |

| 12 | Drywall dust | Home Depot, Livermore, CA |

| 13 | Cornstarch | Raley's Grocery Store, Pleasanton, CA |

| 14 | Baking powder | Raley's Grocery Store, Pleasanton, CA |

| 15 | GABA (gamma-Aminobutyric acid) | Sigma-Aldrich Corp, St. Louis, MO |

| 16 | L-Glutamic acid | Sigma-Aldrich Corp, St. Louis, MO |

| 17 | Kaolin | Sigma-Aldrich Corp, St. Louis, MO |

| 18 | Chitin | Sigma-Aldrich Corp, St. Louis, MO |

| 19 | Chitosan | Sigma-Aldrich Corp, St. Louis, MO |

| 20 | Magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) | Sigma-Aldrich Corp, St. Louis, MO |

| 21 | Boric acid | Sigma-Aldrich Corp, St. Louis, MO |

| 22 | Powdered toothpaste | Walmart Pharmacy, Livermore, CA |

| 23 | Popcorn salt | Raley's Grocery Store, Pleasanton, CA |

| 24 | Baby powder | Target Stores, Livermore, CA |

| 25 | Powdered infant formula, iron fortified | Target Stores, Livermore, CA |

| 26 | Environmental Background Sample Extract | Prepared by LLNL, CA |

Phase 5b: White Powder Spiked with Spores of B. anthracis Sterne

The white powders tested in Phase 5a were spiked with spores of Sterne strain and further tested to understand the ability of the white powders to inhibit agent detection by the LFA. Five milligrams of each white powder were suspended in 450 μL of BTA buffer and 50 μL of a suspension of Sterne strain spores (final spore concentration = 5 × 107 spores/mL). Each tube was vortexed for 10 seconds. The suspension was allowed to settle for at least 5 minutes; then 150 μL of the supernatant was removed and added to the LFA. Two sets of each powder spiked with B. anthracis Sterne spores were prepared and tested once by each of 5 different operators to understand the degree, if any, to which each white powder inhibited detection of the spores.

Phase 6a: Environmental Filter Extract

Pooled environmental filter extract containing 6 μg extracted protein/μL were shipped to Omni Array Biotechnology, where operators added an equal volume of BTA buffer. After mixing for 10 seconds, 150 μL of supernatant was added to the Anthrax LFA. Each filter extract was tested 5 times to understand the specificity and robustness of the assay by identifying any potential inhibition of the internal control or false-positive reactions.

Phase 6b: Environmental Filter Extract Spiked with Spores of B. anthracis Ames

A 500-μL volume of filter extract was mixed with 400 μL of BTA buffer and 100 μL of B. anthracis Ames spores (final concentration of 5 × 107 spores/mL). After mixing for 10 seconds, a 150-μL volume of supernatant was added to the LFA. The spiked filter extract was tested in 5 replicates to understand whether the presence of filter extract inhibited detection of spores by this assay.

Biosafety Considerations

All of the virulent B. anthracis strains used in this study were handled with appropriate biosafety conditions at the CDC according to Institutional Bio-Safety Guidelines. All other organisms, including low-risk bacterial strains, were handled, processed, and tested under safety protocols in accordance with the 5th edition of Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL).36 To minimize the risk of aerosols, cultures were handled using BSL-2 practices that also required personal protective equipment and procedures such as gowning, use of gloves and protective eyewear, and working in a certified Class II biosafety cabinet (BSC). All work areas before and after the testing were cleansed with 10% bleach, while disposal of stock cultures or biomedical waste was done in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Statistical Analysis

The performance of the lateral flow assay was assessed by calculating the sensitivity and specificity of the assay using the results from all the testing done in this study. MedCalc Statistical Software version 16.1 (MedCalc Software bvba, Ostend, Belgium; https://www.medcalc.org; 2016) was used for calculation of sensitivity and specificity and also the positive and negative likelihood ratios from the visual results of the lateral flow assay. BioThreat Alert Reader MX values were used for generating the Receiver Operator Characteristic Curves, interactive dot plots of anthrax lateral flow assay and LFA sensitivity and specificity calculations, and assay performance evaluation using MedCalc software. Dot density plot and titration curves of BTA Reader values were made using GraphPad Prism version 6.07 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, California, USA, www.graphpad.com). Receiver Operator Characteristic Curve and interactive dot plot of anthrax lateral flow assay were made using MedCalc Software.

Results

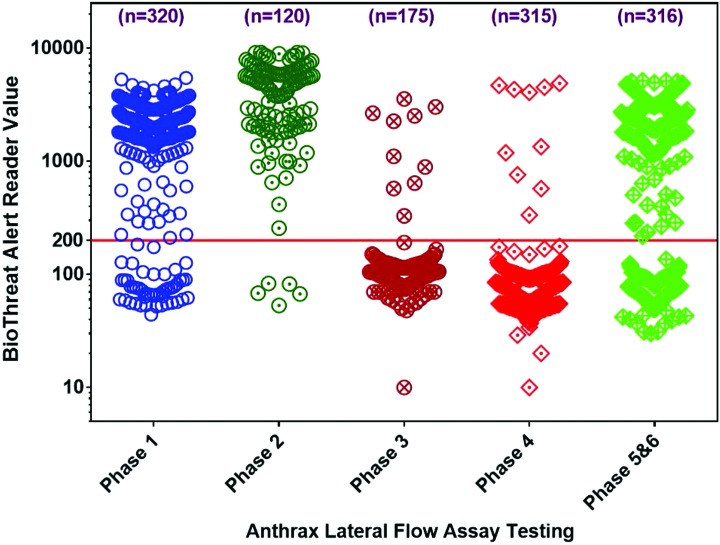

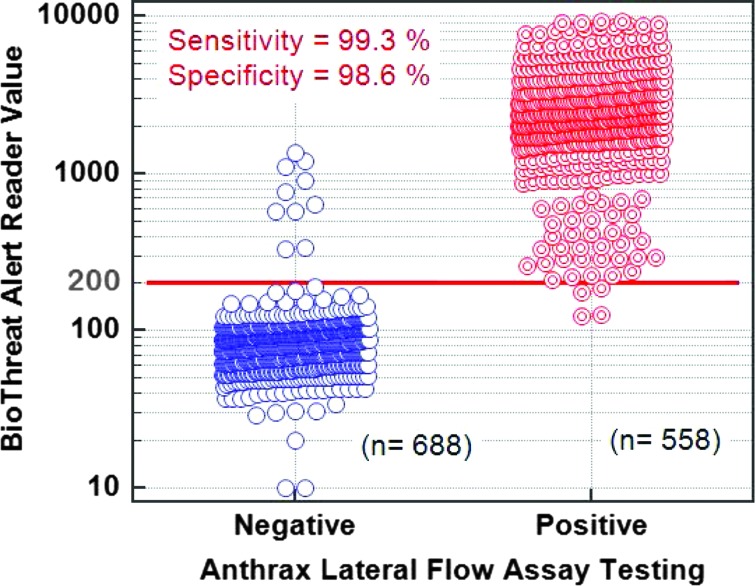

A 6-phase study was conducted to evaluate and assess the performance of the Anthrax BioThreat Alert lateral flow assay. A total of 1,246 tests were performed in this study, and the BTA reader values from these tests are shown in Figure 1. The dot density diagram summarizes all of the test results obtained in this validation study. It provides a visual representation of the distribution of BTA reader values in each phase of the study. The number of tests, including the positive and negative controls tested for each phase, is shown at the top. The BTA reader cut-off value of 200 is shown as the solid line. In Phase 1, a total of 320 LFAs were tested for the range finding and repeatability study, and all the tests gave correct results. In Phase 2, 22 B. anthracis strains in the inclusivity panel were evaluated, and all the samples gave correct test results for this phase while performing a total of 120 LFA tests. A total of 175 LFAs were tested in Phase 3 for the evaluation of 33 B. anthracis near neighbors, and 32 of 33 strains gave correct test results. Anthrax LFA testing performed in Phase 4 (n = 315) for the evaluation of 61 environmental background panel yielded 60 of 61 correct results. A total of 316 anthrax LFA cassettes were tested in the evaluation of 26 white powders and environmental aerosol collection filter extract with and without spiking of B. anthracis spores. All of the 26 white powders alone, aerosol filter extract, and 25 of 26 of B. anthracis spores spiked white powders showed correct LFA results.

Figure 1.

Dot density diagram that summarizes the testing performed in this validation. It provides a visual representation of the BTA value distribution in each phase. The number of tests, including positive and negative controls, for each phase is displayed at the top of each phase's cluster. The cut-off value of 200 is shown as a solid line. Color images available at www.liebertonline.com/hs

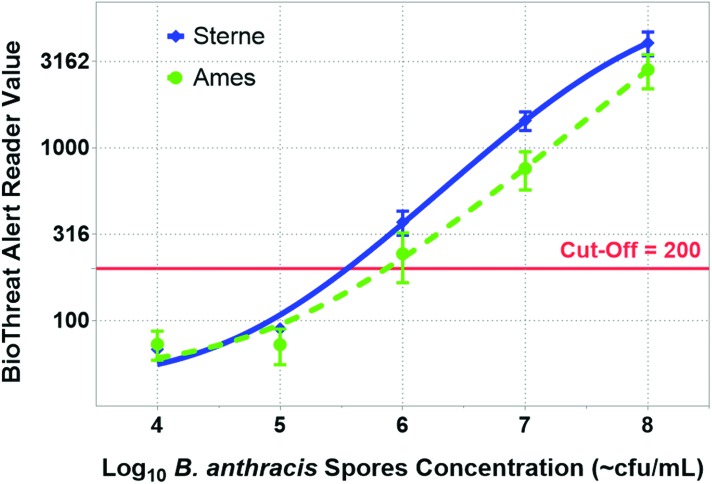

Anthrax LFA results obtained with different concentrations of Sterne and Ames spores are shown as titration curves in Figure 2. The curves were generated using the average of at least 5 tests with each spore concentration, and the error bars are the standard deviations. Titration curves for the Sterne and Ames strains were plotted using nonlinear variable slope (4 parameters) dose-response stimulation equations. The curves show a similar estimated limit of detection (LOD) at ∼106 cfu/mL for both strains since it was the lowest concentration tested that uniformly gave positive results above the cut-off of 200. Nonlinear dose-response curve fitting was performed using GraphPad Prism version 6.07 for Windows.

Figure 2.

The titration curves depict BTA reader value with respect to the log10 concentration of anthrax spores from the Ames strain as well as the Sterne strain. The curves were generated using the average of at least 5 tests, and the error bars are the standard deviations. The cut-off value of 200 is shown as a solid line. For both strains, the first test concentration that is above the cut-off value is 106 cfu/mL. Color images available at www.liebertonline.com/hs

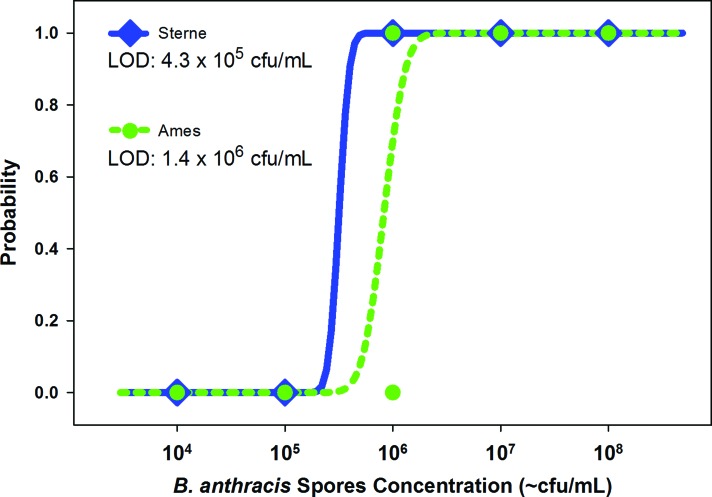

The results of these tests were used for calculating the probability of detecting Sterne and Ames strain spores. A Probit regression analysis was performed to determine the concentration of Sterne or Ames spores (Figure 3) that would correspond to a probability of 0.95, which is equivalent to the estimated limit of detection within 95% confidence intervals.37 The calculated LOD based on Probit analysis for Sterne strain spores was 4.3 × 105 cfu/mL (6.45 × 104 cfu/assay) and for Ames strain spores 1.5 × 106 cfu/mL (2.25 × 105 cfu/assay). This is a ∼3-fold difference in LOD between the 2 strains. Area Under the Curve (AUC) by Receiver Operator Characteristic (ROC) Curve analysis was calculated for both Sterne and Ames strains. No statistically significant difference in ROC AUC was found (P = 0.0671) between the detection of Ames and Sterne spores.

Figure 3.

Probit regressions for the B. anthracis Sterne and Ames strain spores. The curves are calculated probability of detection as a function of spore concentration. The estimated limit of detection is calculated by finding the spore concentration with a probability of detection at 0.95. For Sterne spores, the LOD is 4.3 × 105 cfu/mL (6.4 × 104 cfu/assay), and for Ames spores the LOD is 1.4 × 106 cfu/mL (2.1 × 105 cfu/assay). Color images available at www.liebertonline.com/hs

The LFA assay was further tested for repeatability by 5 operators, each of whom performed 24 tests with Sterne strain spores at a final concentration of ca. 106/mL (ca. 1.5 × 105 cfu/assay) for a total of 120 assays. All 120 tests yielded positive results both visually and by the BioThreat Alert Reader MX. Anthrax LFA assays for inclusivity testing with spores of 22 different B. anthracis strains were all positive. The results were the same when the LFA cassettes were read visually or using the BioThreat Alert Reader MX. The reader correctly called the cassettes positive or negative in all the cases based on the pre-set cut-off value of 200.

Sensitivity and specificity are basic measures of performance for a diagnostic/detection test. Together, they describe how well the test can determine whether the analyte (eg, B. anthracis spores) is present or absent in the tested sample. Since the visual results were the same as the BTA Reader call, the former were used to calculate the sensitivity and specificity of the LFA (Table 5). The data from the results of the LFA are displayed in a 2 × 2 contingency table. The test result falls in 1 of the 4 categories: true positive (TP, B. anthracis antigen present and test positive); false positive (FP, B. anthracis antigen not present but test positive); false negative (FN, B. anthracis antigen present but test negative), and true negative (B. anthracis antigen absent and test negative). A total of 1,246 tests were performed, of which 558 were positive samples and 688 were negative samples.

Table 5.

2 × 2 Contingency Table to Assess the Accuracy of a LFA for Spores of B. anthracis

| Spore Positive | Spore Negative | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Test Positive | 554 | 10 | 564 |

| Test Negative | 4 | 678 | 682 |

| Total | 558 | 688 | 1,246 |

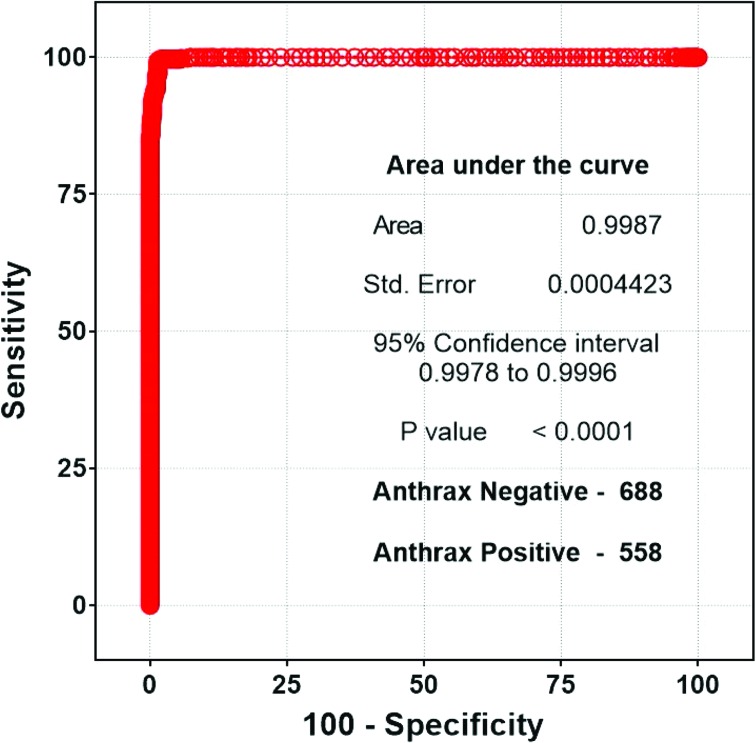

Sensitivity and specificity of the LFA was calculated, and the results are shown in Table 6. Sensitivity is defined as the proportion of true positives that are correctly identified by the test and is calculated as 100% × TP/(TP+FN). Specificity is defined as the proportion of true negatives that are correctly identified by the test and is calculated as 100% × TN/(FP+TN). From the results of this evaluation, the estimated sensitivity of the LFA was 99.3% and the estimated specificity was 98.6%. Additional calculations of the Area Under the Curve, positive and negative likelihood ratios, and positive and negative predictive value of this test were also performed, and the results shown in Table 6. In this study, 44.8% of all the samples tested were LFA positive.

Table 6.

Statistical Analysis of the Performance of a LFA for Spores of B. anthracisa

| Parameter | Percentage | Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 99.28% | 98.17% to 99.80% |

| Specificity | 98.55% | 97.34% to 99.30% |

| Area under the curve | 0.99 | 0.98 to 0.99 |

| Positive likelihood ratio | 68.31 | 36.92 to 126.39 |

| Negative likelihood ratio | 0.01 | 0.00 to 0.02 |

| Anthrax test prevalence | 44.78% | 42.00% to 47.59% |

| Positive predictive value | 98.23% | 96.76% to 99.15% |

| Negative predictive value | 99.41% | 98.51% to 99.84% |

Data used for calculations are presented in Table 5.

The positive reactivity of the assay was also measured using BioThreat Alert Reader MX. Even though the reader values are not quantitative, the values can be used to further evaluate the accuracy of a detection test to discriminate the test positive samples from those that are test negative using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis. The sensitivity and specificity are calculated for every possible cut-off point selected to discriminate between the positive and negative populations. In an ROC curve, the true-positive rate (sensitivity) is plotted as a function of the false-positive rate (100 specificity) for different cut-off points. Each point on the ROC plot represents a sensitivity/specificity pair corresponding to a particular decision threshold. Figure 4 shows the ROC curve of anthrax LFA based on the results obtained in this study. The area under the curve is 0.9987, indicating the test is very accurate and reliable. Sensitivity and specificity can also be calculated from the ROC curve.

Figure 4.

Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve provides a visual representation of the sensitivity and specificity of this assay. Each point on the curve is a possible cut-off value, and its place on the curve is determined by its specificity and sensitivity. The calculated assay sensitivity is 99.3%, and the specificity is 98.6%. Color images available at www.liebertonline.com/hs

The data used for ROC analysis can also be depicted as an interactive dot plot (Figure 5). In this plot, the BTA reader values are shown on the Y-axis, and different cut-off values can be used to estimate the sensitivity and specificity at that value. The Youden index J is the maximum vertical distance between the ROC curve and the line of equality. The cutoff value that responds to the Youden index J can give the optimal combination of sensitivity and specificity, if the disease prevalence is 50%. In this analysis, a threshold reader value of 177 gave a sensitivity of 99.5% and specificity of 98.4%. The BTA reader cut-off is set at 200 for a positive call. Hence, at this cut-off the anthrax LFA sensitivity is 98.3% and specificity is 99.6%.

Figure 5.

A dot density diagram that shows all 1,246 tests performed, grouped as designated positive and designated negative by the BTA reader. The cut-off value of 200 is shown as a solid line. The number of tests performed in each group is shown in parentheses. Any data points in the designated negative group that were above the cut-off value are false positive, while any data points in the designated positive group that were below the cut-off value are false negative. Color images available at www.liebertonline.com/hs

Discussion

A robust approach to public health preparedness for potential anthrax attacks consists of several facets, including the development of medical countermeasures (vaccines, antibiotics, etc) and diagnostics and surveillance for early identification of disease outbreaks. Defense of a city following a deliberate release of B. anthracis spores requires rapid identification that an attack has occurred so that medical countermeasures can be deployed and used within 48 hours of first exposure.38 Several technologies have been developed to detect and identify either spores of B. anthracis or one or more of its toxins. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used during the 2001 anthrax attacks, with primer and probe sets targeting each of the plasmids as well as the chromosome.39 Alam et al40 improved PCR sensitivity by using 2 signatures for the gene coding for edema factor; Christensen et al41 determined that real-time PCR could identify 50 fg, or 9 genome equivalents of B. anthracis Ames using either the RAPID or Smart Cycler platforms. However, PCR requires clean samples in a small volume and is not generally suitable for field use.42,43 Other methods of detection have included fluorescence-based sandwich immunoassays on glass slides,44,45 peptide functionalized surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS), piezo-electric based detection,43,46 PCR combined with fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET),47 and aptamers and bacteriophage.43 While each of these methods holds some promise for laboratory-based detection, none is currently appropriate for field use to rapidly screen unknown environmental samples (ie, white powders) for the presence of B. anthracis spores.

Lateral flow immunochromatographic assays were commercially introduced for pregnancy testing in 1988.48 Simple to use and requiring minimal training,49 LFAs are ideal for use by first responders and law enforcement officers to test suspicious materials in field settings. BioThreat Alert® Assays have previously been evaluated for the detection of other biothreat agents, including orthopoxviruses,50 ricin,33 abrin,34 and Yersinia pestis.51 Limited evaluations have also been conducted with LFAs for the detection of Francisella tularensis (unpublished data), botulinum neurotoxins,52 and staphylococcal enterotoxins.53 In an earlier study, King et al54 detected 105 spores/mL of B. anthracis Pasteur strain using the Tetracore BTA LFA.

The Anthrax BioThreat Alert Test Strip is a rapid qualitative test to detect the presence of B. anthracis spores in environmental samples. The test uses a combination of a monoclonal detector antibody and polyclonal capture antibody to selectively capture and detect the presence of B. anthracis spores in aqueous samples. The purpose of the current study was to evaluate the performance of this assay in order to understand its sensitivity, specificity, reproducibility, and limitations for use in the field and also to determine whether this assay could be used for screening samples in a laboratory.

Because of the widespread diversity of B. anthracis, we also determined whether this LFA would detect the presence of spores from 22 strains belonging to different clades. All strains yielded positive results both visually and with the BioThreat Alert Reader. However, one limitation with the present testing of the inclusivity panel organisms was the use of spore concentrations that were greater than the LOD for the Ames strain. In the future, it may be more informative if testing were to be done with spore concentrations closer to the LOD of the strain being tested.

In conclusion, the Anthrax BioThreat Alert Test Strip is a fast, reliable assay that can be used in the field to qualitatively assess an unknown sample for the presence of B. anthracis spores, the results of which may be used to inform public health actions. Samples yielding positive results should be forwarded to a Laboratory Response Network (LRN) laboratory for additional confirmatory testing.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the important contributions to this manuscript of Dr. Douglas L. Anders, Hazardous Materials Response Unit, Federal Bureau of Investigation Laboratory, Quantico, Virginia, and Dr. Sally Hojvat, Center for Devices and Radiological Health, Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, Maryland, for subject matter expert advice and consultation. We express our thanks and appreciation for their assistance in the preparation and execution of this project. This work was funded by Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Science and Technology Directorate (S&T) Homeland Security Research Projects Agency, Contract #HSHQDC-12-C-00071. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position of DHS.

References

- 1.Bouzianas DG. Medical countermeasures to protect humans from anthrax bioterrorism. Trends Microbiol 2009;17(11):522-528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brossier F, Mock M. Toxins of Bacillus anthracis. Toxicon 2001;39(11):1747-1755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jamie WE. Anthrax: diagnosis, treatment, prevention. Primary Care Update for OB/GYNS 2002;9:117-121 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koehler TM. Bacillus anthracis physiology and genetics. Mol Aspects Med 2009;30:386-396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Helgason E, Økstad OA, Caugant DA, et al. Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus, and Bacillus thuringiensis—one species on the basis of genetic evidence. Appl Environ Microbiol 2000;66(6):2627-2630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pilo P, Frey J. Bacillus anthracis: molecular taxonomy, population genetics, phylogeny and patho-evolution. Infect Genet Evol 2011;11(6):1218-1224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dragon DC, Rennie RP. The ecology of anthrax spores: tough but not invincible. Can Vet J 1995;36(5):295-301 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russell AD, Hugo WB, Ayliffe GAJ. Principles and Practice of Disinfection, Preservation and Sterilization. 3d ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell Science; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Driks A. The Bacillus anthracis spore. Mol Aspects Med 2009;30:368-373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beatty ME, Ashford DA, Griffin PM, Tauxe RV, Sobel J. Gastrointestinal anthrax. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:2527-2531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu X, Wang D, Ren J, et al. Identification of the immunogenic spore and vegetative proteins of Bacillus anthracis vaccine strain A16R. PLoS One 2013;8(3):e57959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cote CK, Welkos SL, Bozue J. Key aspects of the molecular and cellular basis of inhalational anthrax. Microbes Infect 2011;13(14-15):1146-1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fouet A. The surface of Bacillus anthracis. Mol Aspects Med 2009;30:374-385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balali-Mood M, Moshiri M, Etemad L. Medical aspects of bio-terrorism. Toxicon 2013;69:131-142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gutting BW, Gaske KS, Schilling AS, et al. Differential susceptibility of macrophage cell lines to Bacillus anthracis-Vollum 1B. Toxicol in Vitro 2005;19(2):221-229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ezzell JW, Jr, Welkos SL. The capsule of Bacillus anthracis, a review. J Appl Microbiol 1999;87:250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uchida L, Hashimoto K, Terakado N. Virulence and immunogenicity in experimental animals of Bacillus anthracis strains harbouring or lacking 110 Mda and 60Mda plasmids. J Gen Microbiol 1986;132:557-559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kohout E, Sehat A, Ashraf M. Anthrax: a continuous problem in southwest Iran. Am J Med Sci 1964;247:565-575 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mock M, Fouet A. Anthrax. Annu Rev Microbiol 2001;55:647-671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cavallo JD, Ramisse F, Girardet M, Vaissaire J, Mock M, Hernandez E. Antibiotic susceptibilities of 96 isolates of Bacillus anthracis isolated in France between 1994 and 2000. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002;46(7):2307-2309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: investigation of bioterrorism-related anthrax and interim guidelines for clinical evaluation of persons with possible anthrax. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001;50(43):941-948 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bell DM, Kozarsky PE, Stephens DS. Clinical issues in the prophylaxis, diagnosis, and treatment of anthrax. Emerg Infect Dis 2002;8:222-225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: investigation of bioterrorism-related anthrax, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001;50(45):1008-1010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedlander AM, Welkos SL, Pitt MLM, et al. Postexposure prophylaxis against experimental inhalation anthrax. J Infect Dis 1993;167(5):1239-1243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanna PC, Ireland JAW. Understanding Bacillus anthracis pathogenesis. Trends Microbiol 1999;7:180-182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holty JC, Bravata DM, Liu H, Olshen RA, McDonald KM, Owens DK. Systematic review: a century of inhalational anthrax cases from 1900 to 2005. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:270-280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cieslak TJ, Eitzen EM., Jr. 1999. Clinical and epidemiologic principles of anthrax. Emerg Infect Dis 1999;5:552-555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pickering AK, Osorio M, Lee GM, Grippe VK, Bray M, Merkel TJ. Cytokine response to infection with Bacillus anthracis spores. Infect Immun 2004;72:6382-6389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fennelly KP, Davidow AL, Miller SL, Connell N, Ellner JJ. Airborne infection with Bacillus anthracis—from mills to mail. Emerg Infect Dis 2004;10:996-1001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karginov VA, Robinson TM, Riemenschneider J, et al. Treatment of anthrax infection with combination of ciprofloxacin and antibodies to protective antigen of Bacillus anthracis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2004;40:71-74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peters CJ, Hartley DM. 2002. Anthrax inhalation and lethal human infection. Lancet 2002;359:710-711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morse SA, Kellogg RB, Perry S, et al. Detecting biothreat agents: the Laboratory Response Network. ASM News 2003;69:433-437 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hodge DR, Prentice KW, Ramage JG, et al. Comprehensive laboratory evaluation of a highly specific lateral flow assay for the presumptive identification of ricin in suspicious white powders and environmental samples. Biosecur Bioterror 2013;11:237-250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramage JG, Prentice KW, Morse SA, et al. Comprehensive laboratory evaluation of a specific lateral flow assay for the presumptive identification of abrin in suspicious white powders and environmental samples. Biosecur Bioterror 2014;12:49-62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.AOAC SMPR 2010.004. Standard method performance requirements for immunological-based handheld assays (HHAs) for the detection of Bacillus anthracis spores in visible powders. J AOAC Int 2011;94(4):1352-1355 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories. 5th ed. December 2009. http://www.cdc.gov/biosafety/publications/bmbl5/bmbl.pdf Accessed August5, 2016

- 37.CLSI. Evaluation of Detection Capability for Clinical Laboratory Measurement Procedures; Approved Guideline—Second Edition. CLSI document EP17-A2. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Franz DR. Preparedness for an anthrax attack. Mol Aspects Med 2009;30:503-510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoffmaster AR, Meyer RF, Bowen MP, et al. Evaluation and validation of a real-time polymerase chain reaction assay for rapid identification of Bacillus anthracis. Emerg Infect Dis 2002;8:1178-1182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alam SI, Agarwal GS, Kamboj DV, Rai GP, Singh L. Detection of spores of Bacillus anthracis from environment using polymerase chain reaction. Indian J Exp Biol 2003;41:177-180 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Christensen DR, Hartman LJ, Loveless BM, et al. Detection of biological threat agents by real-time PCR: comparison of assay performance on the R.A.P.I.D., the LightCycler, and the Smart Cycler platforms. Clin Chem 2006;52:141-145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morel N, Volland H, Dano J, et al. Fast and sensitive detection of Bacillus anthracis spores by immunoassay. Appl Environ Microbiol 2012;78:6491-6498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rao SS, Mohan KVK, Atreya CD. Detection technologies for Bacillus anthracis: prospects and challenges. J Microbiol Meth 2010;82:1-10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tims TB, Lim DV. Rapid detection of Bacillus anthracis spores directly from powders with an evanescent wave fiber-optic biosensor. J Microbiol Meth 2004;59:127-130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hang J, Sundaram AK, Zhu P, et al. Development of a rapid and sensitive immunoassay for detection and subsequent recovery of Bacillus anthracis spores in environmental samples. J Microbiol Meth 2008;73:242-246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Campbell GA, Mutharasan R. Method of measuring Bacillus anthracis spores in the presence of copious amounts of Bacillus thuringiensis and Bacillus cereus. Anal Chem 2007;79:1145-1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hadfield T, Ryan V. 2013. RAZOR™ EX anthrax air detection system for detection of Bacillus anthracis spores from aerosol collection samples: collaborative study. J AOAC Int 2013;96:392-398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gubala V, Harris LF, Ricco AJ, Tan MX, Williams DE. Point of care diagnostics: status and future. Anal Chem 2012;84:487-515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Andreotti PE, Ludwig GV, Peruski AH, Tuite JJ, Morse SA, Peruski F., Jr. Immunoassay of infectious agents. Biotechniques 2003;35:850-859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Townsend MB, MacNeil A, Reynolds MG, et al. Evaluation of the Tetracore Orthopox BioThreat® antigen detection assay using laboratory grown orthopoxviruses and rash illness clinical specimens. J Virol Meth 2013;187:37-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tomaso H, Thullier P, Seibold E, et al. Comparison of hand-held test kits, immunofluorescence microscopy, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and flow cytometric analysis for rapid presumptive identification of Yersinia pestis. J Clin Microbiol 2007;45(10):3404-3407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gessler F, Pagel-Wieder S, Avondet MA, Böhnel H. Evaluation of lateral flow assays for the detection of botulinum neurotoxin type A and their application in laboratory diagnosis of botulism. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2007;57:243-249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iura K, Tsuge K, Seto Y, Sato A. Detection of proteinous toxins using the BioThreat Alert system. Japanese Journal of Forensic Toxicology 2004;22:13-16 [Google Scholar]

- 54.King D, Luna V, Cannons A, Cattani J, Amuso P. Performance assessment of three commercial assays for direct detection of Bacillus anthracis spores. J Clin Microbiol 2003;41:3454-3455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]