Abstract

Aims

To evaluate 0.75 mg of dulaglutide, a once‐weekly glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonist, compared with once‐daily insulin glargine for glycaemic control in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D).

Methods

In this phase III, randomized, open‐label, parallel‐group, 26‐week study, 361 patients with inadequately controlled T2D receiving sulphonylureas and/or biguanides, aged ≥20 years, with glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels 7.0–10.0% (53–86 mmol/mol), inclusive, were randomized (1 : 1) to receive dulaglutide or glargine. Participants and investigators were not masked to treatment allocation. The primary measure was change from baseline in HbA1c at 26 weeks, analysed using a mixed‐effects model for repeated measures, with a predefined non‐inferiority margin of 0.4%.

Results

At week 26, least‐squares (LS) mean (standard error) reductions in HbA1c were −1.44 (0.05)% [−15.74 (0.55) mmol/mol] in the dulaglutide group and −0.90 (0.05)% [−9.84 (0.55) mmol/mol] in the glargine group. The mean between‐group treatment difference in HbA1c was −0.54% (95% CI −0.67, −0.41) [−5.90 mmol/mol (95% CI −7.32, −4.48)]; p < 0.001. Dulaglutide significantly reduced body weight compared with glargine at week 26 (LS mean difference −1.42 kg, 95% CI −1.89, −0.94; p < 0.001). The most frequent adverse events with dulaglutide treatment were nasopharyngitis and gastrointestinal symptoms. The incidence of hypoglycaemia was significantly lower with dulaglutide [47/181 (26%)] compared with glargine [86/180 (48%)], p < 0.001.

Conclusion

In Japanese patients with T2D uncontrolled on sulphonylureas and/or biguanides, once‐weekly dulaglutide was superior to once‐daily glargine for reduction in HbA1c at 26 weeks. Although dulaglutide increased gastrointestinal symptoms, it was well tolerated, with an acceptable safety profile.

Keywords: dulaglutide, GLP‐1 receptor agonist, insulin glargine, type 2 diabetes

Introduction

Glucagon‐like peptide‐1 (GLP‐1) is an endogenous incretin hormone that is rapidly secreted by intestinal L‐cells in response to food ingestion. GLP‐1 stimulates postprandial insulin secretion, inhibits glucagon secretion and slows gastric emptying 1. The acute administration of GLP‐1 induces satiety and reduces food intake in subjects with and without diabetes 2, 3. Several GLP‐1 receptor agonists have been developed or are in development for the treatment of type 2 diabetes (T2D) 4, 5, 6. As of February 2015, four GLP‐1 receptor agonists (liraglutide 7, exenatide twice daily and once weekly 8, 9, and lixisenatide 10) have been launched in Japan.

Dulaglutide is a long‐acting GLP‐1 receptor agonist that mimics some of the effects of endogenous GLP‐1; it has been approved in the USA and the European Union at once‐weekly doses of 0.75 and 1.5 mg as a subcutaneous injection to improve glycaemic control in patients with T2D 11, 12. Dulaglutide 0.75 mg has been approved in Japan for the treatment of T2D. Dulaglutide has been modified to render the molecule more stable against dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inactivation, to increase the solubility of the peptide, to reduce immunogenic potential and to increase the duration of its pharmacological activity 13. In global clinical trials completed to date, dulaglutide 1.5 mg has shown superiority to metformin, sitagliptin, insulin glargine and exenatide twice daily and non‐inferiority to liraglutide in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) changes, and has been associated with reductions in body weight in patients with T2D 14, 15, 16, 17, 18. Also, in a phase II study in Japanese patients, dulaglutide showed dose‐dependent HbA1c reductions in doses up to 0.75 mg, with an acceptable safety profile 19.

Injectable antihyperglycaemic medications, such as insulin and GLP‐1 receptor agonists, are used for patients whose T2D is inadequately controlled with oral antihyperglycaemics; basal insulin is a treatment option for second‐ or third‐line therapy 20, 21; therefore, this study compared once‐weekly dulaglutide and once‐daily basal insulin therapy in Japanese patients who were inadequately controlled by sulphonylureas and/or biguanides.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Patients

This study was a 26‐week, randomized, open‐label, parallel‐group, multicentre, phase III, non‐inferiority study, comparing the efficacy and safety of once‐weekly dulaglutide 0.75 mg with once‐daily insulin glargine in Japanese patients with T2D inadequately controlled with monotherapy or dual therapy of oral antihyperglycaemic drugs (sulphonylureas and/or biguanides). The study had four periods: screening (2 weeks), lead‐in (2 weeks), randomization (at week 0), immediately followed by treatment (26 weeks), and safety follow‐up (30 days). Patients who discontinued the study before the end of the treatment period had an early termination visit. All patients were to return 30 days after the end of treatment for a final safety follow‐up visit. The study was conducted from June 2012 to July 2013 at 35 sites in Japan and was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01584232).

Japanese men and women with T2D, aged ≥20 years, with a body mass index (BMI) ≥18.5 and <35.0 kg/m2 and HbA1c at screening ≥7.0 and ≤10.0%, who were taking stable doses of sulphonylureas (2.5–5 mg of glibenclamide, 60–80 mg of gliclazide, or 2–3 mg of glimepiride) and/or biguanides (750–1500 mg of metformin or 100–150 mg of buformin) were randomized. Key exclusion criteria included: patients with type 1 diabetes; patients previously treated with any GLP‐1 receptor agonist; patients who had received therapy with an α‐glucosidase inhibitor, thiazolidinedione, glinide or dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitor, or insulin within 3 months before screening; patients undergoing chronic systemic glucocorticoid therapy; and patients who had a clinically significant gastric emptying abnormality, cardiovascular disease, liver disease, renal disease, active or untreated malignancy, poorly controlled hypertension, a history of chronic or acute pancreatitis, obvious clinical signs or symptoms of pancreatitis, or a self or family history of medullary C‐cell hyperplasia, focal hyperplasia or medullary thyroid carcinoma.

A common protocol was approved at each site by an institutional review board; the study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice. Before participation, all patients provided written informed consent 22.

Randomization and Study Treatments

Patients were randomized in a 1 : 1 ratio to receive subcutaneous injections of once‐weekly dulaglutide 0.75 mg or once‐daily glargine according to a computer‐generated random sequence with an interactive voice response system. Randomization was stratified by concomitant antihyperglycaemic regimen (sulphonylureas only, biguanides only, or sulphonylurea and biguanide), BMI group at baseline (<25 and ≥25 kg/m2) and screening HbA1c [≤8.5 and >8.5% (≤69 and >69 mmol/mol)]. An open‐label design was used, and patients, investigators and site staff were not masked to treatment allocation.

Dulaglutide was administered once weekly, and glargine was administered once daily at bedtime, both by subcutaneous injection. The dose of dulaglutide (0.75 mg/week) was selected based on a phase II study conducted in Japan 19. The guideline for initiation and titration of glargine doses was modified for Japanese patients based on the ATLAS study 23 (Table S1), with an initial dose of glargine between 4.0 and 8.0 IU and a fasting serum glucose (FSG) target of ≤6.1 mmol/l for investigator‐driven adjustments. Glargine doses were to be adjusted once a week based on the average of self‐monitored fasting blood glucose values over the previous 3 days. Dose adjustments were to be made as needed once weekly for up to 8 weeks; adjustments at later times were allowed if needed for further optimization of glycaemic control, based on the investigators' discretion. Patients continued their sulphonylureas and/or biguanides at the baseline dose throughout the study; the dose of sulphonylurea may have been reduced if daytime hypoglycaemia was observed. The use of other, additional antihyperglycaemic medications was prohibited during the study period while patients continued on study medication.

In certain instances, patients were allowed to continue in the study without study medication on an alternative antihyperglycaemic medication for collection of safety data (for example, patients who developed serious adverse events or sustained hyperglycaemia, as prespecified in the study protocol). Sustained hyperglycaemia was defined as self‐monitored fasting blood glucose >15.0 mmol/l (weeks 2–8) or >13.3 mmol/l (weeks 9–26). Patients who experienced sustained hyperglycaemia (≥3 times per week) for at least 2 weeks were to be discontinued from study treatment.

Study Endpoints and Assessments

The primary efficacy measure was change from baseline in HbA1c at 26 weeks. Additional measures included percentages of patients achieving HbA1c targets of <7.0% (53 mmol/mol) or ≤6.5% (48 mmol/mol) and changes in FSG (central laboratory measure), eight‐point self‐monitored blood glucose (SMBG) profiles, and body weight. The eight time points for the SMBG profiles were before and 2 h after each meal (breakfast, lunch and dinner), at bedtime and before breakfast the following morning (‘second pre‐breakfast’ value). Safety assessments included adverse events, vital signs (pulse rate and blood pressure, ECGs), laboratory variables and dulaglutide antidrug antibodies. Data on vital signs were collected at each visit using standardized equipment; triplicate measurements in the supine, sitting and standing positions were to be recorded, in that order. The data in sitting position, which are most commonly used in clinical practice, are shown in the results. ECG data were read by a central vendor for reporting purposes. Hypoglycaemia was defined as a blood glucose concentration of ≤3.9 mmol/l and/or symptoms and/or signs attributable to hypoglycaemia. Severe hypoglycaemia was defined as an episode requiring the assistance of another person to actively administer therapy 24.

An independent external committee adjudicated deaths and non‐fatal cardiovascular adverse events in a masked manner, with prespecified event criteria based on the preponderance of evidence and clinical knowledge and experience. An independent external committee also adjudicated adverse events of severe or serious abdominal pain, suspected or definite acute or chronic pancreatitis, and lipase or amylase concentrations of 3 × the upper limit of normal (ULN) or higher. Serum calcitonin was measured throughout the study.

Statistical Analyses

Assuming no difference in HbA1c between dulaglutide and glargine and an 11% drop‐out from baseline to week 26, it was estimated that a sample size of 360 randomized patients (180 per arm) would provide 90% power to show non‐inferiority (margin of 0.4%) of dulaglutide to glargine, with common standard deviation (s.d.) of 1.1% for change in baseline HbA1c and a one‐sided 0.025 significance level.

The primary objective was non‐inferiority of dulaglutide to glargine for HbA1c change from baseline at week 26. The primary efficacy analysis mixed‐model repeated measures included treatment, antihyperglycaemic regimen (sulphonylureas, biguanides or sulphonylureas and biguanides), baseline BMI group (<25 or ≥25 kg/m2), visit and treatment‐by‐visit interaction as fixed effects, baseline as a covariate and patient as a random effect. The 95% confidence interval (CI) for the treatment difference (dulaglutide − glargine) of the least‐squares (LS) means at week 26 based on this model was used to assess the primary objective. If the upper limit of the 95% CI was <0.4%, then non‐inferiority of dulaglutide to glargine was to be concluded. Superiority of dulaglutide to glargine was to be tested if and only if non‐inferiority was concluded. Type I error rate was controlled at 0.025 (one‐sided). A mixed‐model repeated measures was used for FSG and body weight. The percentage of patients achieving HbA1c targets was analysed with a repeated logistic regression model with fixed effects of treatment, antihyperglycaemic regimen, baseline BMI group, visit, treatment‐by‐visit interaction and baseline HbA1c as a covariate. Analysis of covariance with last observation carried forward (LOCF) was used for SMBG and vital signs. Hypoglycaemia rates were analysed with a generalized estimating equation model with negative binomial distribution. The percentage of patients with adverse events was analysed using Fisher's exact test. For laboratory data, an analysis of variance on ranks, with treatment as a fixed effect was conducted. The two‐sided significance level for treatment comparisons was 0.05.

Efficacy analyses were conducted on the full analysis set (all randomized patients who received at least one dose of study drug). Safety analyses were conducted on the as‐treated population, according to the patients' actual treatments (safety analysis set). For the assessment of efficacy and hypoglycaemia events, only data obtained before the initiation of other antihyperglycaemic medication were used. For the assessment of safety, only data obtained while the patient was on study treatment were used.

Results

Patients

Of 438 patients screened, 361 (dulaglutide, n = 181; glargine, n = 180) were randomized to treatment; 348 completed treatment with study medication and 13 discontinued study medication because of an adverse event (dulaglutide, n = 6; glargine, n = 2), patient decision (dulaglutide, n = 1; glargine, n = 1), investigator decision (dulaglutide, n = 1; glargine, n = 1) or protocol violation (dulaglutide, n = 1; Figure S1). Two patients who discontinued study medication later completed the study. Eleven patients discontinued the study as a result of: an adverse event (dulaglutide, n = 3; glargine, n = 1); patient decision (dulaglutide, n = 2; glargine, n = 1); loss to follow‐up (dulaglutide, n = 1); or investigator decision (dulaglutide, n = 2; glargine, n = 1).

Patient characteristics were similar between the groups (Table 1). The mean (s.d.) daily glargine dose was 5.0 IU (0.07 IU/kg) at time of first injection and 12.5 IU (0.17 IU/kg) at endpoint. The most frequent pre‐existing conditions at baseline overall were hypertension (54.8%), dyslipidaemia (43.2%), and hepatic steatosis (25.2%). In the dulaglutide and glargine groups, 13/117 (11.1%) and 11/114 (9.6%) patients, respectively, decreased their concomitant sulphonylurea dose from baseline as a result of hypoglycaemia. One patient in the dulaglutide group discontinued concomitant sulphonylurea as a result of hypoglycaemia. Dosing of concomitant sulphonylureas and biguanides at baseline and week 26 was shown in Table S2.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Dulaglutide 0.75 mg (N = 181) | Insulin glargine (N = 180) | Total (N = 361) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Men | 125 (69) | 133 (74) | 258 (71) |

| Women | 56 (31) | 47 (26) | 103 (29) |

| Age, years | 57.5 (10.5) | 56.1 (11.3) | 56.8 (10.9) |

| Age ≥65 years, n (%) | 45 (25) | 47 (26) | 92 (26) |

| Weight, kg | 70.9 (13.7) | 71.1 (13.8) | 71.0 (13.7) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.1 (3.6) | 25.9 (3.9) | 26.0 (3.7) |

| Diabetes duration, years | 8.9 (6.7) | 8.8 (6.1) | 8.8 (6.4) |

| HbA1c | |||

| % | 8.1 (0.8) | 8.0 (0.9) | 8.0 (0.9) |

| mmol/mol | 65 (9.1) | 64 (9.4) | 64 (9.3) |

| Fasting blood glucose concentration, mmol/l | 8.8 (2.0) | 8.6 (2.0) | 8.7 (2.0) |

| Seated vital signs | |||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 129 (14) | 129 (13) | 129 (14) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 81 (9) | 80 (9) | 80 (9) |

| Pulse rate, beats/min | 72 (11) | 71 (9) | 72 (10) |

| Previous oral antihyperglycaemic medication use, n (%) | |||

| Sulphonylureas only | 34 (19) | 33 (18) | 67 (19) |

| Biguanides only | 64 (35) | 66 (37) | 130 (36) |

| Sulphonylureas and biguanides | 83 (46) | 81 (45) | 164 (45) |

| Pre‐existing conditions, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 107 (59.1) | 91 (50.6) | 198 (54.8) |

| Dyslipidaemia | 75 (41.4) | 81 (45.0) | 156 (43.2) |

| Hepatic steatosis | 51 (28.2) | 40 (22.2) | 91 (25.2) |

Data are mean (standard deviation), unless indicated. BMI, body mass index; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; N, number of patients in full analysis set.

Efficacy

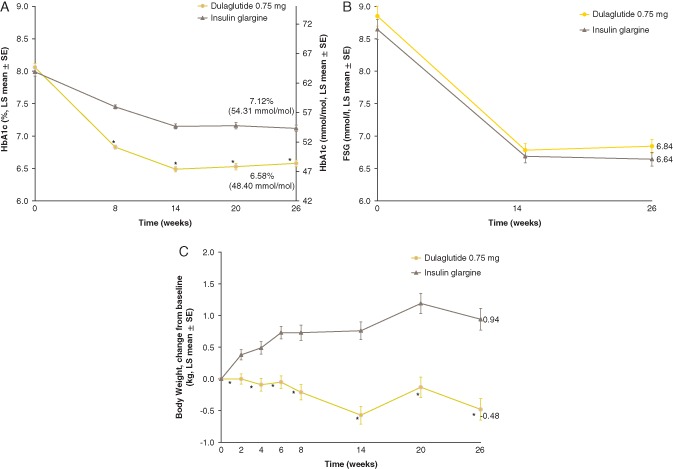

Both dulaglutide and glargine significantly reduced HbA1c from baseline (Table 2). The LS mean reduction in HbA1c with dulaglutide was non‐inferior and superior to that achieved by glargine, with a between‐group difference in HbA1c reduction from baseline of −0.54% (95% CI −0.67, −0.41) or −5.90 mmol/mol (95% CI −7.32, −4.48); p < 0.001. Dulaglutide significantly reduced HbA1c from baseline compared with glargine at weeks 8, 14, 20 and 26 (all p < 0.001; Figure 1A). At week 26 (LOCF), significantly greater percentages of patients on dulaglutide achieved HbA1c targets of <7.0% (53 mmol/mol) or ≤6.5% (48 mmol/mol) compared with glargine [127/178 (71%) versus 82/179 (46%); p < 0.001 and 91/178 (51%) versus 43/179 (24%); p < 0.001, respectively].

Table 2.

Efficacy assessments

| Dulaglutide 0.75 mg (N = 181) | Insulin glargine (N = 180) | Dulaglutide 0.75 mg versus insulin glargine | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Week 26 | Change from baseline to week 26 | Baseline | Week 26 | Change from baseline to week 26 | LS mean difference (95% CI) | p | |

| HbA1c | ||||||||

| % | 8.06 (0.82) | 6.58 (0.05) | −1.44 (0.05) | 7.99 (0.87) | 7.12 (0.05) | −0.90 (0.05) | −0.54 (−0.67, −0.41) | <0.001 |

| mmol/mol | 64.6 (9.0) | 48.4 (0.6) | −15.7 (0.6) | 63.8 (9.5) | 54.3 (0.6) | −9.8 (0.6) | −5.9 (−7.3, −4.5) | <0.001 |

| FSG concentration, mmol/l | 8.84 (2.03) | 6.84 (0.11) | −1.90 (0.11) | 8.64 (2.01) | 6.64 (0.11) | −2.10 (0.11) | 0.19 (−0.09, 0.48) | 0.18 |

| Body weight, kg | 71.00 (13.71) | 70.51 (0.17) | −0.48 (0.17) | 71.08 (13.75) | 71.93 (0.17) | 0.94 (0.17) | −1.42 (−1.89, −0.94) | <0.001 |

Data are least‐squares mean (s.e.) or least‐squares mean difference (95% CI) unless otherwise stated. Baseline data are mean (s.d.). Within‐group changes are from MMRM. Between‐group changes and p‐values are from pairwise comparisons (dulaglutide − glargine) using MMRM. CI, confidence interval; FSG, fasting serum glucose; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; LS, least‐squares; MMRM, mixed‐model repeated measures; N, number of patients in full analysis set; s.d., standard deviation; s.e., standard error.

Figure 1.

Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), fasting serum glucose (FSG) and body weight. (A) Mean [standard error (s.e.)] HbA1c values. (B) Mean (s.e.) FSG (mmol/l) values. (C) Mean (s.e.) change from baseline in body weight (kg). *p < 0.001 for dulaglutide versus glargine. LS, least‐squares.

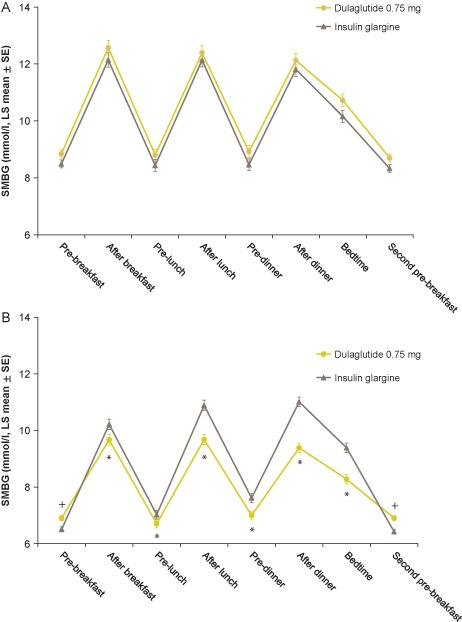

Reductions from baseline in FSG were similar in both treatment groups at weeks 14 and 26 (Figure 1B). The LS mean [standard error (s.e.)] changes from baseline in FSG at week 26 were −1.9 (0.11) and −2.1 (0.11) mmol/l for the dulaglutide and glargine groups, respectively (Table 2). Dulaglutide significantly reduced SMBG values from baseline compared with glargine for all time points (p < 0.05) except for pre‐breakfast and pre‐breakfast the following day (second pre‐breakfast), which were significantly reduced from baseline in the glargine group compared with dulaglutide (p < 0.05; Table S3). The mean eight‐point SMBG profiles by treatment at baseline and week 26 (LOCF) are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Eight‐point self‐monitored blood glucose (SMBG) profiles (mmol/l) by time of day (analysis of covariance). (A) At baseline. (B) At week 26 (LOCF). *SMBG statistically significantly lower in the dulaglutide group compared with insulin glargine (p < 0.05). +SMBG statistically significantly lower in the insulin glargine group compared with dulaglutide (p < 0.05). LS, least‐squares.

Body weight was decreased from baseline in the dulaglutide group and increased from baseline in the glargine group (Figure 1C). The LS mean difference in body weight change from baseline at week 26 was −1.42 kg (95% CI −1.89, −0.94; p < 0.001; Table 2).

Safety

No deaths occurred during the study (Table 3). A total of 12 (3%) patients [dulaglutide, n = 9 (5%); glargine, n = 3 (2%); p = 0.14] experienced at least one serious adverse event during the treatment period (Table S3). The four most frequently reported treatment‐emergent adverse events which occurred more frequently with dulaglutide than glargine were diarrhoea, nausea, constipation and lipase level increase (all p < 0.05; Table 3). Although 1 patient discontinued dulaglutide treatment because of an adverse event of vomiting, all gastrointestinal adverse events of diarrhoea, nausea, constipation and vomiting were mild in intensity. Besides the vomiting event mentioned previously, other adverse events resulting in discontinuation of study treatment were acute myocardial infarction, cerebral infarction, eczema, liver carcinoma ruptured and decrease in weight (in the dulaglutide group) and eczema and seventh nerve paralysis (in the glargine group).

Table 3.

Safety assessments

| Dulaglutide 0.75 mg (N = 181) | Insulin glargine (N = 180) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deaths | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| Serious adverse events* | 9 (5) | 3 (2) | 0.139 |

| Patients with at least one treatment‐emergent adverse event | 136 (75) | 111 (62) | 0.007 |

| Treatment‐emergent adverse events ≥5% in either treatment group | |||

| Nasopharyngitis | 49 (27) | 46 (26) | 0.811 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 62 (34) | 25 (14) | <0.001 |

| Diarrhoea | 22 (12) | 4 (2) | <0.001 |

| Nausea | 17 (9) | 2 (1) | <0.001 |

| Constipation | 16 (9) | 6 (3) | 0.045 |

| Vomiting | 9 (5) | 2 (1) | 0.061 |

| Lipase increased | 9 (5) | 1 (<1) | 0.020 |

| Patients who discontinued study because of adverse events | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 0.623 |

| Seated vital signs† (mean change from baseline; s.e.) | |||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 0.4 (0.8) | 2.7 (0.8) | 0.052 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.964 |

| Pulse rate, beats/min | 3.0 (0.5) | −1.0 (0.5) | <0.001 |

| ECG PR interval† (ms; mean change from baseline; s.e.) | 3.1 (0.7) | −0.7 (0.7) | <0.001 |

| Pancreatic enzymes‡ (median change; Q1, Q3) | |||

| Total amylase§, U/l | 7 (3, 16) | 3 (−2, 9) | <0.001 |

| Lipase§, U/l | 9 (2, 16) | −1 (−6, 3) | <0.001 |

| Patients with treatment‐emergent abnormal change in pancreatic enzymes¶ (>ULN) | |||

| Total amylase | 14/169 (8) | 9/168 (5) | 0.388 |

| Lipase | 41/156 (26) | 6/165 (4) | <0.001 |

| Patients with pancreatic enzyme concentration >3 × ULN | |||

| Total amylase | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| Lipase** | 6 (3) | 1 (<1) | 0.065 |

| Treatment‐emergent dulaglutide antidrug antibodies†† | |||

| Dulaglutide antidrug antibodies | 1 (<1) | 0 | N/A |

| Dulaglutide neutralizing antidrug antibodies | 1 (<1) | 0 | N/A |

| nsGLP‐1 neutralizing antibodies | 1 (<1) | 0 | N/A |

Data are n (%) unless otherwise specified. MedDRA version 16.1. LOCF, last observation carried forward; MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities; N, number of patients in safety analysis set; N/A, not applicable; nsGLP1, native sequence glucagon‐like peptide‐1; Q1, first quartile; Q3, third quartile; s.e., standard error; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Reported serious adverse events are listed in Table S4.

Data are least‐squares mean change (s.e.).

Data are LOCF.

p‐values for within‐group change from baseline at week 26 and endpoint (LOCF) were <0.01 for both treatment groups by Wilcoxon signed‐rank test.

Denominator is patients with a normal baseline and a postbaseline measurement; p‐value is from Fisher's exact test.

p‐value is from Fisher's exact test.

These values include all postbaseline observations including the safety follow‐up.

Hypoglycaemia occurred in 47 (26%) patients receiving dulaglutide and 86 (48%) patients receiving glargine (p < 0.001), with a mean (s.e.) event rate of 0.09 (0.02) events per patient per 30 days for dulaglutide, compared with 0.24 (0.04) for glargine (p < 0.001). Nocturnal hypoglycaemia occurred in 16 (9%) patients receiving dulaglutide and 48 (27%) patients receiving glargine (p < 0.001), with a mean (s.e.) event rate of 0.04 (0.01) events per patient per 30 days for dulaglutide, compared with 0.15 (0.04) for glargine (p = 0.002). No patient had severe hypoglycaemia during the study.

No patient received additional antidiabetes medication for sustained hyperglycaemia during the planned treatment period.

Seven cardiovascular adverse events [dulaglutide group, 5 (cerebral infarction, 2; acute myocardial infarction, 1; percutaneous coronary intervention, 1; and angina pectoris, 1); glargine group, 2 (spinal cord infarction and intracranial aneurysm)] were adjudicated by an independent committee. All cases were confirmed by adjudication. Dulaglutide significantly increased mean seated pulse rate and ECG PR interval from baseline at week 26 (LOCF) compared with glargine (Table 3).

At week 26, treatment with dulaglutide significantly increased total amylase and lipase compared with glargine (p < 0.001; Table 3). A significantly greater proportion of patients in the dulaglutide group had treatment‐emergent postbaseline lipase levels above the ULN compared with the glargine group (dulaglutide, 26%; glargine, 4%; p < 0.001). A total of 7 patients [dulaglutide, n = 6 (3.4%); glargine, n = 1 (0.6%)] had post‐baseline lipase levels 3 × ULN or higher. None of these patients experienced abdominal pain typical of acute pancreatitis, and the elevated value decreased below 3 × ULN while the patients continued on study medication. No cases of pancreatitis were confirmed by adjudication.

There were no treatment‐emergent reports of thyroid neoplasm, including C‐cell hyperplasia or medullary thyroid carcinoma. All patients had calcitonin values within normal limits. No other clinically significant changes were detected for any other laboratory safety assessment.

One patient (0.6%) in the dulaglutide group experienced treatment‐emergent dulaglutide antidrug antibodies (Table 3). Few patients [dulaglutide, n = 3 (1.7%); glargine, n = 1 (0.6%)] had injection‐site reactions.

Discussion

In the present study, once‐weekly dulaglutide was superior to once‐daily glargine as measured by HbA1c reduction at 26 weeks in Japanese patients with T2D. This finding is consistent with those reported in previous studies that compared efficacy and safety between GLP‐1 receptor agonists and glargine: non‐inferiority to once‐daily glargine with respect to change in HbA1c was shown in global phase III studies for exenatide twice daily 25, taspoglutide 26 and albiglutide 27. Also, greater HbA1c reduction compared with glargine was observed in the phase III studies for liraglutide (global) 28 and exenatide once weekly (Japan) 29. In addition to the finding of glycaemic superiority for dulaglutide compared with glargine in this study, treatment with dulaglutide resulted in weight loss and fewer hypoglycaemic events compared with glargine.

When evaluating the efficacy of insulin formulations, dosing algorithms are an important factor. In this study, glargine dosing was adjusted based on targeting FSG ≤6.1 mmol/l. Although the mean FSG at endpoint (week 26) in the glargine group (6.6 mmol/l) was higher than the target, this was similar to the average seen in treat‐to‐target glargine studies (6.7 mmol/l) 30. The mean HbA1c at endpoint in the glargine group (7.1%) was also similar to the average seen in treat‐to‐target glargine studies 30. The mean dose of glargine at endpoint in this study was 12.5 IU/day. This was lower than the average daily dose in Western populations, but similar to the average dose in the Japanese population (10–15 IU/day) reported in previous clinical studies and post‐marketing surveillance reports for glargine 29, 31, 32. As further evidence of active glargine titration, the incidence of hypoglycaemia (48%) in the glargine group in the present study was similar to the incidence (54%) reported in a review article for incidence of hypoglycaemia in a treat‐to‐target study of insulin glargine 33.

In patients on dulaglutide in the present study, the HbA1c reduction from baseline at 26 weeks was −1.44% (−15.74 mmol/mol), and the percentage of patients achieving the HbA1c target of <7.0% (53 mmol/mol) was 71%. These results were similar to those observed in the phase II monotherapy study in Japanese patients 19. At week 12 in that study, treatment with dulaglutide 0.75 mg resulted in an HbA1c change from baseline of −1.35% (−14.76 mmol/mol), and 77% of patients achieved the HbA1c target of <7.0% (53 mmol/mol). These consistent effects on glycaemic control were also observed in the dulaglutide global phase III AWARD programme (for dulaglutide doses of 0.75 and 1.5 mg) 14, 15, 16, 17, 18.

In terms of body weight change, reductions from baseline were observed with dulaglutide and increases were observed with glargine. The mean difference at week 26 was −1.4 kg, which was smaller than the mean differences (−2.6 to −4.1 kg) observed in other global phase III trials in which a GLP‐1 receptor agonist was directly compared with glargine 25, 26, 27, 28, 34; however, this may have been attributable to the leaner body mass (mean body weight at baseline: 71 kg) of the Japanese population in this study, and it is consistent with the mean difference (−2.0 kg) seen in the Japan phase III study for exenatide once‐ weekly 29.

Overall, once‐ weekly dulaglutide was safe and well tolerated, and safety results were consistent with other studies of dulaglutide 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19. The incidences of nausea and diarrhoea in the dulaglutide group in combination with sulphonylurea and/or biguanides were slightly higher (nausea, 9%; diarrhoea, 12%) than those observed in the Japan phase II study investigating dulaglutide as monotherapy (nausea, 6%; diarrhoea, 3% in the 0.75‐mg group) 19; however, all gastrointestinal adverse events of diarrhoea, nausea, constipation and vomiting were mild in intensity. Several clinical trials of GLP‐1 receptor agonists have been conducted in Japan, and the incidence of adverse events can be compared between this study and those studies. The incidence of nausea with dulaglutide 0.75 mg in this study (9%) was slightly higher than that seen with liraglutide 0.9 mg (5%) 35 and was similar to that seen with exenatide 2 mg once weekly (13%) 29, but was lower than that seen with exenatide 5 or 10 µg twice daily (25–36%) 36 or with lixisenatide 20 µg (25–40%) 37, 38. Also, the incidence of injection site reactions with dulaglutide 0.75 mg (2%) was similar to that seen with liraglutide 0.9 mg (6%) 39, exenatide 10 µg twice daily (3%) 40, and lixisenatide 20 µg (1%) 37, but was lower than that seen with exenatide 2 mg once weekly (41%) 29. Consistent with previous reports in the GLP‐1 receptor agonist class 18, 41, elevations in pancreatic enzymes were noted, with no confirmed cases of pancreatitis.

In the present study, dulaglutide increased pulse rate compared with glargine. These increases were similar to those observed in phase III studies of other long‐acting GLP‐1 receptor agonists, such as liraglutide and exenatide once weekly 40, 42, 43.

The limitations of the present study include its open‐label design, which could have affected physicians' and patients' behaviours; however, it would have been difficult to use a double‐blind design because glargine requires titration throughout the study period. The length of the study was fairly short in view of the chronic nature of T2D, but the duration was sufficient for each treatment to reach steady state and the treatment effect to be represented in the primary outcome of HbA1c.

In conclusion, in Japanese patients with T2D who were no longer achieving glycaemic control on sulphonylureas and/or biguanides, once‐weekly dulaglutide 0.75 mg was an effective alternative to once‐daily insulin glargine for glycaemic control, with weight loss and lower rates of hypoglycaemia.

Conflict of Interest

E. A., N. I. and Y. T. were trial investigators and participated in data collection. T. O., M. T. and T. I. prepared the first draft of the manuscript. T. O. was responsible for the statistical considerations in the analysis and trial design. M. T. and T. I. were responsible for medical oversight during the trial and trial design. All authors participated in reviewing and interpreting the data and providing comments and revisions to the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and take full responsibility for the content. E. A. has received a grant from Eli Lilly, lecture fees from Sanofi, Astellas, Ono, Takeda, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharmaceutical and Novo Nordisk, and a research endowment from AstraZeneca, Astellas and Takeda. N. I. has received grants from Eli Lilly, Roche Diagnostics, and Shiratori; research endowments from Novartis, Sanofi, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharmaceutical, Astellas, Daiichi Sankyo, Japan Tobacco, Ono, Taisho Toyama, and Takeda; grants and research endowments from Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharmaceutical and MSD; and other awards from Boehringer Ingelheim, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Japan Diabetes Foundation, and Novo Nordisk. Y. T. has received a grant and research endowments from Eli Lilly, research endowments from Boehringer Ingelheim, Kowa, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Sanofi, and Taisho Toyama; lecture fees from AstraZeneca, NovoNordisk, and Ono; and research endowments and lecture fees from Astellas, Daiichi Sankyo, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharmaceutical, MSD, Novartis, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharmaceutical, and Takeda. M. T., T. I., and T. O. are employees of Eli Lilly Japan K.K, and T. I. has the company stock option.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Disposition.

Table S1. Dosing adjustment schedule for once‐daily insulin glargine.

Table S2. Dosing of concomitant sulphonylureas and biguanides (mg) at baseline and week 26.

Table S3. Summary of least squares mean (standard error) changes from baseline in self‐monitored blood glucose (mmol/l) values (LOCF at week 26).

Table S4. Summary of serious adverse events by preferred term.

Acknowledgements

This trial was sponsored by Eli Lilly K.K. (Kobe, Japan). We thank the trial investigators, trial staff and trial participants for their contributions. We would also like to thank Miwa Sakaridani for clinical trial management of the study and Mary K. Re of inVentiv Health Clinical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) for assisting with medical writing and the preparation of tables and figures.

References

- 1. MacDonald PE, El‐Kholy W, Riedel MJ et al. The multiple actions of GLP‐1 on the process of glucose‐stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes 2002; 51(Suppl. 3): S434–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gutzwiller JP, Degen L, Heuss L, Beglinger C. Glucagon‐like peptide 1 (GLP‐1) and eating. Physiol Behav 2004; 82: 17–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mudaliar S, Henry RR. Incretin therapies: effects beyond glycemic control. Am J Med 2009; 122(Suppl. 6): S25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Madsbad S, Kielgast U, Asmar M, Deacon CF, Torekov SS, Holst JJ. An overview of once‐weekly glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists — available efficacy and safety data and perspectives for the future. Diabetes Obes Metab 2011; 13: 394–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lorenz M, Evers A, Wagner M. Recent progress and future options in the development of GLP‐1 receptor agonists for the treatment of diabesity. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2013; 23: 4011–4018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lund A, Knop FK, Vilsbøll T. Glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: differences and similarities. Eur J Intern Med 2014; 25: 407–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Novo Nordisk Pharma Ltd, Tokyo . Victoza [Japan package insert]. 2014. Available from URL: http://www.info.pmda.go.jp/downfiles/ph/PDF/620023_2499410G1021_1_08.pdf Accessed 21 May 2015 (in Japanese).

- 8. AstraZeneca K.K., Osaka . Byetta [Japan package insert]. 2015. Available from URL: http://www.info.pmda.go.jp/downfiles/ph/PDF/670227_2499411G1026_2_04.pdf Accessed 6 June 2015 (in Japanese).

- 9. AstraZeneca K.K., Osaka . Bydureon [Japan package insert]. 2015. Available from URL: http://www.info.pmda.go.jp/downfiles/ph/PDF/670227_2499411G3029_1_11.pdf Accessed 6 June 2015 (in Japanese).

- 10. Sanofi K.K., Tokyo . Lyxumia [Japan package insert]. 2014. Available from URL: http://www.info.pmda.go.jp/downfiles/ph/PDF/780069_2499415G1024_1_04.pdf Accessed 21 May 2015 (in Japanese).

- 11. Lilly USA, LLC, Indianapolis . Trulicity [Prescribing information]. 2014. Available from URL: http://pi.lilly.com/us/trulicity-uspi.pdf. Accessed 23 March 2015.

- 12. Eli Lilly and Company, Houten . Trulicity [Summary of product characteristics]. 2014. Available from URL: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/002825/human_med_001821.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124. Accessed 23 March 2015.

- 13. Glaesner W, Vick AM, Millican R et al. Engineering and characterization of the long‐acting glucagon‐like peptide‐1 analogue LY2189265, an FC fusion protein. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2010; 26: 287–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Umpierrez GE, Povedano ST, Manghi FP, Shurzinske L, Pechtner V. Efficacy and safety of dulaglutide monotherapy versus metformin in type 2 diabetes in a randomized controlled trial (AWARD‐3). Diabetes Care 2014; 37: 2168–2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nauck M, Weinstock R, Umpierrez GE, Guerci B, Skrivanek Z, Milicevic Z. Efficacy and safety of dulaglutide versus sitagliptin after 52 weeks in type 2 diabetes in a randomized controlled trial (AWARD‐5). Diabetes Care 2014; 37: 2149–2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Giorgino F, Benroubi M, Sun JH, Zimmermann AG, Pechtner V. Efficacy and safety of once‐weekly dulaglutide versus insulin glargine in combination with metformin and glimepiride in type 2 diabetes patients (AWARD‐2). Diabetes 2014; 63(Suppl. 1): A87 [330‐OR]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wysham C, Blevins T, Arakaki R et al. Efficacy and safety of dulaglutide added onto pioglitazone and metformin versus exenatide in type 2 diabetes in a randomized controlled trial (AWARD‐1). Diabetes Care 2014; 37: 2159–2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dungan KM, Povedano ST, Forst T et al. Once‐weekly dulaglutide versus once‐daily liraglutide in metformin‐treated patients with type 2 diabetes (AWARD‐6): a randomised, open‐label, phase 3, non‐inferiority trial. Lancet 2014; 384: 1349–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Terauchi Y, Satoi Y, Takeuchi M, Imaoka T. Monotherapy with the once weekly GLP‐1 receptor agonist dulaglutide for 12 weeks in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes: dose‐dependent effects on glycaemic control in a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. Endocr J 2014; 61: 949–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient‐centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2012; 35: 1364–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Japan Diabetes Society . Treatment guide for Diabetes 2012–2013. 2013. Available from URL: http://www.jds.or.jp/common/fckeditor/editor/filemanager/connectors/php/transfer.php?file=/uid000025_54726561746D656E745F47756964655F666F725F44696162657465735F323031322D323031332E706466. Accessed 23 March 2015.

- 22. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki . Recommendations guiding physicians in biomedical research involving human subjects. JAMA 1997; 277: 925–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Odawara M, Misra A, Shestakova M et al. Titration of insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Asia: physician‐ versus patient‐led? Rationale of the Asian Treat to Target Lantus Study (ATLAS). Diabetes Technol Ther 2011; 13: 67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Workgroup on Hypoglycemia, American Diabetes Association . Defining and reporting hypoglycemia in diabetes: a report from the American Diabetes Association Workgroup on Hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care 2005; 28: 1245–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Heine RJ, Van Gaal LF, Johns D et al. Exenatide versus insulin glargine in patients with suboptimally controlled type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2005; 143: 559–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nauck M, Horton E, Andjelkovic M et al. Taspoglutide, a once‐weekly glucagon‐like peptide 1 analogue, vs. insulin glargine titrated to target in patients with Type 2 diabetes: an open‐label randomized trial. Diabet Med 2013; 30: 109–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Weissman PN, Carr MC, Ye J et al. HARMONY 4: randomised clinical trial comparing once‐weekly albiglutide and insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin with or without sulfonylurea. Diabetologia 2014; 57: 2475–2484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Russell‐Jones D, Vaag A, Schmitz O et al. Liraglutide vs insulin glargine and placebo in combination with metformin and sulfonylurea therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus (LEAD‐5 met + SU): a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia 2009; 52: 2046–2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Inagaki N, Atsumi Y, Oura T, Saito H, Imaoka T. Efficacy and safety profile of exenatide once weekly compared with insulin once daily in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes treated with oral antidiabetes drug(s): results from a 26‐week, randomized, open‐label, parallel‐group, multicenter, noninferiority study. Clin Ther 2012; 34: 1892–1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bloomgarden Z, Handelsmann Y. Lessons from glargine trials: what is the goal fasting glucose with basal insulin? J Diabetes 2014; 6: 271–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kawamori R, Iwamoto Y, Kadowaki T, Iwasaki M. Efficacy and safety of insulin glargine in concurrent use with oral hypoglycemic agents for the treatment of type 2 diabetic patients. J Clin Therap Med 2003; 19: 445–464 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 32. Odawara M, Ohtani T, Kadowaki T. Dosing of insulin glargine to achieve the treatment target in Japanese type 2 diabetes on a basal supported oral therapy regimen in real life: ALOHA study subanalysis. Diabetes Technol Ther 2012; 14: 635–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rosenstock J, Dailey G, Massi‐Benedetti M, Fritsche A, Lin Z, Salzman A. Reduced hypoglycemia risk with insulin glargine: a meta‐analysis comparing insulin glargine with human NPH insulin in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2005; 28: 950–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Diamant M, Van Gaal L, Stranks S et al. Once weekly exenatide compared with insulin glargine titrated to target in patients with type 2 diabetes (DURATION‐3): an open‐label randomised trial. Lancet 2010; 375: 2234–2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kaku K, Rasmussen MF, Nishida T, Seino Y. Fifty‐two‐week, randomized, multicenter trial to compare the safety and efficacy of the novel glucagon‐like peptide‐1 analog liraglutide vs glibenclamide in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Investig 2011; 2: 441–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kadowaki T, Namba M, Imaoka T et al. Improved glycemic control and reduced bodyweight with exenatide: a double‐blind, randomized, phase 3 study in Japanese patients with suboptimally controlled type 2 diabetes over 24 weeks. J Diabetes Investig 2011; 2: 210–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Seino Y, Min KW, Niemoeller E, Takami A, EFC10887 GETGOAL‐L Asia Study Investigators . Randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial of the once‐daily GLP‐1 receptor agonist lixisenatide in Asian patients with type 2 diabetes insufficiently controlled on basal insulin with or without a sulfonylurea (GetGoal‐L‐Asia). Diabetes Obes Metab 2012; 14: 910–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Onishi Y, Niemoeller E, Ikeda Y, Takagi H, Yabe D, Seino Y. Efficacy and safety of lixisenatide in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus inadequately controlled by sulfonylurea with or without metformin: subanalysis of GetGoal‐S. J Diabetes Investig 2015; 6: 201–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare , Victoza review report in Japan. (pg 90) 2009. Available from URL: http://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000153180.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2015.

- 40. Ji L, Onishi Y, Ahn CW et al. Efficacy and safety of exenatide once‐weekly vs exenatide twice‐daily in Asian patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Investig 2013; 4: 53–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pratley RE, Nauck MA, Barnett AH et al. Once‐weekly albiglutide versus once‐daily liraglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on oral drugs (HARMONY 7): a randomised, open‐label, multicentre, non‐inferiority phase 3 study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014; 2: 289–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Seino Y, Rasmussen MF, Nishida T, Kaku K. Efficacy and safety of the once‐daily human GLP‐1 analogue, liraglutide, versus glibenclamide monotherapy in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin 2010; 26: 1013–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kaku K, Rasmussen MF, Clauson P, Seino Y. Improved glycaemic control with minimal hypoglycaemia and no weight change with the once‐daily human glucagon‐like peptide‐1 analogue liraglutide as add‐on to sulphonylurea in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2010; 12: 341–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Disposition.

Table S1. Dosing adjustment schedule for once‐daily insulin glargine.

Table S2. Dosing of concomitant sulphonylureas and biguanides (mg) at baseline and week 26.

Table S3. Summary of least squares mean (standard error) changes from baseline in self‐monitored blood glucose (mmol/l) values (LOCF at week 26).

Table S4. Summary of serious adverse events by preferred term.