Abstract

About 11% of all deaths include heart failure as a contributing cause. The annual cost of heart failure amounts to US $34,000,000,000 in the United States alone. With the exception of heart transplantation, there is no curative therapy available. Only occasionally there are new areas in science that develop into completely new research fields. The topic on non‐coding RNAs, including microRNAs, long non‐coding RNAs, and circular RNAs, is such a field. In this short review, we will discuss the latest developments about non‐coding RNAs in cardiovascular disease. MicroRNAs are short regulatory non‐coding endogenous RNA species that are involved in virtually all cellular processes. Long non‐coding RNAs also regulate gene and protein levels; however, by much more complicated and diverse mechanisms. In general, non‐coding RNAs have been shown to be of great value as therapeutic targets in adverse cardiac remodelling and also as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for heart failure. In the future, non‐coding RNA‐based therapeutics are likely to enter the clinical reality offering a new treatment approach of heart failure.

Keywords: miRNAs, lncRNAs, Cardiovascular disease, Heart failure, Cardiac remodelling

Introduction

The human being has only 1–2% of its genome that codes for mRNAs building the basis for protein synthesis. In contrast, there are many more non‐coding RNAs (ncRNAs) in the genome, most of them with unknown function. Based on their size, ncRNAs are subdivided into (i) small ncRNAs (<200 nucleotides long) including microRNAs (miRNA) and (ii) long ncRNAs (lncRNA), having a length between 0.2 and 2 Kb.1 Virtually all cellular functions are being linked to ncRNAs and they have been identified to be important players in human pathology, including that of the cardiovascular system.

MicroRNAs as therapeutics and diagnostic markers in heart failure

About 1,500–2,000 human miRNAs have been identified that regulate at least half of all mRNAs.2 As there are a number of reviews published on the mechanistic role of miRNAs and their potential use as therapeutic targets,3, 4, 5, 6, 7 I here focus on some fundamental studies and novel aspects of miRNAs in heart failure. A pioneering work about a first miRNA to play a role in cardiac hypertrophy stems from the Olson laboratory, showing miR‐208 to be crucially involved in hypertrophic signalling.8 Most miRNAs are more ubiquitously expressed and are not cell‐type specific. Thus, many miRNAs are expressed at relatively low levels under basal conditions but during pathological stress are strongly up‐regulated. An example is the neurologic‐enriched miRNA miR‐212/132 family, which becomes activated during heart failure (HF) in humans9 and animal models.10 These miRNAs have been shown to regulate cardiac hypertrophy in cardiomyocytes by targeting the anti‐hypertrophic transcription factor forkhead box O3 (FoxO3), leading to hyperactivation of the pro‐hypertrophic calcineurin/NFAT signalling pathway. Importantly, inhibition of miR‐132 rescued cardiac hypertrophy and HF in mice, suggesting a novel therapeutic approach for this pathology.10 Another hallmark of adverse cardiac remodelling is cardiac fibrosis.11 This is accompanied with increased secretion of extracellular matrix proteins and growth factors. An miRNA enriched in cardiac fibroblasts is miR‐21.12 This miRNA is an endogenous brake for the ERK–MAP kinase inhibitor sprouty‐1, which is mechanistically involved in fibrosis development.13 Both miR‐21 and miR‐29 have been shown to serve as potential therapeutic targets for cardiac fibrosis. Recently, circulating levels of miR‐29 were found to directly correlate with different forms of cardiac hypertrophy. 14 Thus, monitoring the level of this miRNA family may be useful for prognostic/therapeutic purposes in adverse cardiac remodelling disease entities. Next to cardiomyocytes and cardiac firbroblasts, the cardiac endothelium plays a major role in cardiac (patho)biology especially as recently suggested in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF).15 Our group recently identified an miRNA involved in the regulation of cardiac vascularization, that is, miR‐24.16 This miRNA is highly expressed in cardiac endothelial cells. Blockade of endothelial miR‐24 limits myocardial infarction (MI) size in mice, via an increase of vascularity leading to improved cardiac function and survival. 16 In terms of diagnostics, a recent publication showed also the use of circulating miRNA patterns in distinguishing Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction (HFrEF) and Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF). 17

Long non‐coding RNAs emerging in heart failure research

Long non‐coding RNAs are defined as transcripts more than 200 nucleotides long that do not code for proteins.18 Important to note is the fact that this definition may be preliminary as indeed some lncRNAs have been reported to encode short peptides in human tissues, which also may have functional effects.19 A classification of lncRNAs can be viewed in the work of Thum and Condorelli. 1 Mechanistically, there are numerous ways how lncRNAs may function in the regulation of the genome. For instance, lncRNAs can interact with all macromolecules within the cell, including other RNA species, proteins, and DNA. Long non‐coding RNAs also have the ability for conformational switching, which can either activate or silence interaction with other molecules.20 Long non‐coding RNAs can be found in the nucleus of a cell or in the cytoplasm or in both compartments. First, lncRNAs involved in cardiac development have been recently proposed—Bvht (Braveheart) and Fendrr (Foxf1 adjacent non‐coding developmental regulatory RNA).21, 22 Bvht seems to be a master gene required for cardiomyocyte differentiation. Unfortunately, Bvht seems to be specific to the mouse, making translations into humans difficult. The lncRNA Fendrr is higher conserved and regulates the expression of important cardiac transcription factors with knockout mice showing defects in cardiac development.22 Only few studies have started to identify potential roles of lncRNAs in the pathogenesis of cardiac diseases. Deep sequencing studies revealed the profile of myocardial lncRNAs to be altered in HF in humans.23 The lncRNA Chrf (cardiac hypertrophy‐related factor) was found to act as a sequence able to sequester miR‐489.24 Interestingly, there are several lncRNAS associated to the locus of the cardiac‐specific gene myosin heavy chain 7 (Myh7); inhibition of the lncRNA Mhrt was mechanistically shown to induce cardiomyopathy subsequent to pressure overload, whereas restoring Mhrt protected the heart from HF.25 Another lncRNA recently linked to cardiac pathology is Carl (cardiac apoptosis‐related lncRNA).26 Carl binds miR‐539, an miRNA found to target the mRNA of a subunit of Prohibitin, where it seems to have a role in mitochondrial homeostasis. By this, Carl serves as an endogenous sponge regulating mitochondrial morphology and cell death in cardiomyocytes.

Non‐coding RNAs as diagnostics and cardiac cell cell communicators

Cells are usually able to produce different forms of vesicles including apoptotic bodies, microvesicles, and exosomes. This also is true for cardiovascular cells. These vesicles contain proteins, miRNA, mRNA, and lncRNAs (unpublished results). Exosomes, for example, are particularity enriched in small RNAs, such as miRNAs.27 Of clinical interest, secreted exosomes can be isolated from biological fluids and their miRNA profile can be assessed, thus emerging as potential biomarkers for diseases.28 This has been suggested also for extracellular longer RNAs, which can be detected in the plasma of patients with MI.29 Recently, our group screened circulating miRNAs in no HF (no‐HF), HFrEF, and HFpEF patients using Taqman miRNA arrays (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). A selected miRNA panel (miR‐30c, miR‐146a, miR‐221, miR‐328, and miR‐375) was further verified and validated in an independent cohort consisting of 225 patients. Indeed, this approach improved the discriminative value of BNP as an HF diagnostic. Combinations of two or more miRNA candidates with BNP had the ability to improve significantly predictive models to distinguish HFpEF from HFrEF compared with BNP alone (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve >0.82).17 Whether these miRNAs are also mechanistically important for HFpEF or HFrEF, disease pathologies are interesting and require further investigations. However, miRNA biomarkers may support diagnostic strategies in subpopulations of patients with HF. Locally, cells might also communicate with each other by shuttling non‐coding RNAs back and forth; for instance, cardiac fibroblasts can secrete exosomes that are enriched with miRNAs that could be taken up by recipient cardiomyocytes, provoking hypertrophy.30 There is increasing evidence that cardiovascular cells are able to communicate via ncRNA transfer, and this also could lead into new strategies aiming at modulation of extracellular non‐coding RNA species.

Conclusion

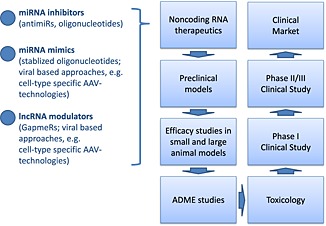

There has been a tremendous increase in knowledge about non‐coding RNAs in cardiovascular biology and disease within the last years. However, this represents only the tip of the iceberg that needs to be discovered to fully understand the importance of non‐coding RNAs. Likely, new non‐coding RNAs will help not only to understand better the mechanisms of heart failure but will develop into new concepts of theragnostic approaches. A variety of endeavours is currently undertaken by various groups worldwide to bring miRNA therapeutics into the clinics within the next 5–8 years. This includes target and drug candidate optimization, efficacy studies in small and large animals, toxicology and safety studies, and absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion studies leading to Phase I, Phase II, and Phase III studies until the market will be reached (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Clinical development plan for non‐coding RNA‐based therapeutics of which some are mentioned on the left. ADME; absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion.

Conflict of interest

The author has filed and licensed microRNA‐related and lncRNA‐related patents.

Acknowledgements

The support of the European Commission‐supported project FIBROTARGET, the Integrated Research and Treatment Center Transplantation (IFB‐Tx; grant number 01EO1302), the Excellence Cluster REBIRTH, the ERC Consolidator grant LONGHEART, and the Foundation Leducq (Project MIRVAD) to T.T. are kindly acknowledged.

Thum, T. (2015) Facts and updates about cardiovascular non‐coding RNAs in heart failure. ESC Heart Failure, 2: 108–111. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12054.

References

- 1. Thum T, Condorelli G. Long noncoding RNAs and microRNAs in cardiovascular pathophysiology. Circ Res 2015; 116: 751–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kozomara A, Griffiths‐Jones S. miRBase: integrating microRNA annotation and deep‐sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res 2011; 39: D152–D157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kumarswamy R, Thum T. Non‐coding RNAs in cardiac remodeling and heart failure. Circ Res 2013; 113: 676–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Condorelli G, Latronico MV, Cavarretta E. microRNAs in cardiovascular diseases: current knowledge and the road ahead. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63: 2177–2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dangwal S, Thum T. microRNA therapeutics in cardiovascular disease models. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2014; 54: 185–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thum T. MicroRNA therapeutics in cardiovascular medicine. EMBO Mol Med 2012; 4: 3–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Small EM, Olson EN. Pervasive roles of microRNAs in cardiovascular biology. Nature 2011; 469: 336–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van Rooij E, Sutherland LB, Qi X, Richardson JA, Hill J, Olson EN. Control of stress‐dependent cardiac growth and gene expression by a microRNA. Science 2007; 316: 575–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thum T, Galuppo P, Wolf C, Fiedler J, Kneitz S, van Laake LW, Doevendans PA, Mummery CL, Borlak J, Haverich A, Gross C, Engelhardt S, Ertl G, Bauersachs J. MicroRNAs in the human heart: a clue to fetal gene reprogramming in heart failure. Circulation 2007; 116: 258–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ucar A, Gupta SK, Fiedler J, Erikci E, Kardasinski M, Batkai S, Dangwal S, Kumarswamy R, Bang C, Holzmann A, Remke J, Caprio M, Jentzsch C, Engelhardt S, Geisendorf S, Glas C, Hofmann TG, Nessling M, Richter K, Schiffer M, Carrier L, Napp LC, Bauersachs J, Chowdhury K, Thum T. The miRNA‐212/132 family regulates both cardiac hypertrophy and cardiomyocyte autophagy. Nat Commun 2012; 3: 1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thum T. Noncoding RNAs and myocardial fibrosis. Nat Rev Cardiol 2014; 11: 655–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kumarswamy R, Volkmann I, Thum T. Regulation and function of miRNA‐21 in health and disease. RNA Biol 2011; 8: 706–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thum T, Gross C, Fiedler J, Fischer T, Kissler S, Bussen M, Galuppo P, Just S, Rottbauer W, Frantz S, Castoldi M, Soutschek J, Koteliansky V, Rosenwald A, Basson MA, Licht JD, Pena JT, Rouhanifard SH, Muckenthaler MU, Tuschl T, Martin GR, Bauersachs J, Engelhardt S. MicroRNA‐21 contributes to myocardial disease by stimulating MAP kinase signalling in fibroblasts. Nature 2008; 456: 980–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Derda AA, Thum S, Lorenzen JM, Bavendiek U, Heineke J, Keyser B, Stuhrmann M, Schulze CP, Widder J, Bauersachs J, Thum T. Blood‐based microRNA signatures differentiate various forms of cardiac hypertrophy. Int J Cardiol 2015; 196: 115–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Seferović PM, Paulus WJ. Clinical diabetic cardiomyopathy: a two‐faced disease with restrictive and dilated phenotypes. Eur Heart J 2015. pii: ehv134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fiedler J, Jazbutyte V, Kirchmaier BC, Gupta SK, Lorenzen J, Hartmann D, Galuppo P, Kneitz S, Pena JT, Sohn‐Lee C, Loyer X, Soutschek J, Brand T, Tuschl T, Heineke J, Martin U, Schulte‐Merker S, Ertl G, Engelhardt S, Bauersachs J, Thum T. MicroRNA‐24 regulates vascularity after myocardial infarction. Circulation 2011; 124: 720–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Watson CJ, Gupta SK, O'Connell E, Thum S, Glezeva N, Fendrich J, Gallagher J, Ledwidge M, Grote‐Levi L, McDonald K, Thum T. MicroRNA signatures differentiate preserved from reduced ejection fraction heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2015; 17: 405–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Batista PJ, Chang HY. Long noncoding RNAs: cellular address codes in development and disease. Cell 2013; 152: 1298–1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wilhelm M, Schlegl J, Hahne H, Gholami AM, Lieberenz M, Savitski MM, Ziegler E, Butzmann L, Gessulat S, Marx H, Mathieson T, Lemeer S, Schnatbaum K, Reimer U, Wenschuh H, Mollenhauer M, Slotta‐Huspenina J, Boese J‐H, Bantscheff M, Gerstmair A, Faerber F, Kuster B. Mass‐spectrometry‐based draft of the human proteome. Nature 2014; 509: 582–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liang JC, Bloom RJ, Smolke CD. Engineering biological systems with synthetic RNA molecules. Mol Cell 2011; 43: 915–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Klattenhoff CA, Scheuermann JC, Surface LE, Bradley RK, Fields PA, Steinhauser ML, Ding H, Butty VL, Torrey L, Haas S, Abo R, Tabebordbar M, Lee RT, Burge CB, Boyer LA. Braveheart, a long noncoding RNA required for cardiovascular lineage commitment. Cell 2013; 152: 570–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grote P, Wittler L, Hendrix D, Koch F, Wahrisch S, Beisaw A, Macura K, Blass G, Kellis M, Werber M, Herrmann BG. The tissue‐specific lncRNA Fendrr is an essential regulator of heart and body wall development in the mouse. Dev Cell 2013; 24: 206–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yang KC, Yamada KA, Patel AY, Topkara VK, George I, Cheema FH, Ewald GA, Mann DL, Nerbonne JM. Deep RNA sequencing reveals dynamic regulation of myocardial noncoding RNAs in failing human heart and remodeling with mechanical circulatory support. Circulation 2014; 129: 1009–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang K, Liu F, Zhou LY, Long B, Yuan SM, Wang Y, Liu CY, Sun T, Zhang XJ, Li PF. The long noncoding RNA CHRF regulates cardiac hypertrophy by targeting miR‐489. Circ Res 2014; 114: 1377–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Han P, Li W, Lin C‐H, Yang J, Shang C, Nurnberg ST, Jin KK, Xu W, Lin C‐Y, Lin C‐J, Xiong Y, Chien H‐C, Zhou B, Ashley E, Bernstein D, Chen P‐S, Chen H‐SV, Quertermous Y, Chang C‐P. A long noncoding RNA protects the heart from pathological hypertrophy. Nature 2014. doi: 10.1038/nature13596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang K, Long B, Zhou L‐Y, Liu F, Zhou Q‐Y, Liu C‐Y, Fan Y‐Y, Li P‐F. CARL lncRNA inhibits anoxia‐induced mitochondrial fission and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes by impairing miR‐539‐dependent PHB2 downregulation. Nat Commun 2014; 5: 3596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Viereck J, Bang C, Foinquinos A, Thum T. Regulatory RNAs and paracrine networks in the heart. Cardiovasc Res 2014; 102: 290–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gupta SK, Bang C, Thum T. Circulating microRNAs as biomarkers and potential paracrine mediators of cardiovascular disease. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2010; 3: 484–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kumarswamy R, Bauters C, Volkmann I, Maury F, Fetisch J, Holzmann A, Lemesle G, de Groote P, Pinet F, Thum T. Circulating long noncoding RNA, LIPCAR, predicts survival in patients with heart failure. Circ Res 2014; 114: 1569–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bang C, Batkai S, Dangwal S, Gupta SK, Foinquinos A, Holzmann A, Just A, Remke J, Zimmer K, Zeug A, Ponimaskin E, Schmiedl A, Yin X, Mayr M, Halder R, Fischer A, Engelhardt S, Wei Y, Schober A, Fiedler J, Thum T. Cardiac fibroblast‐derived microRNA passenger strand‐enriched exosomes mediate cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Clin Invest 2014; 124: 2136–2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]