Abstract

Objective

Vitamin D has pleiotropic effects including immunomodulatory, cardioprotective, and antifibrotic properties and is thus able to modulate the three main links in scleroderma pathogenesis. The aim of the study was to evaluate the level of vitamin D in patients with systemic sclerosis and to analyze the associations between the concentration of vitamin D and the features of systemic sclerosis.

Material and Methods

Fifty-one consecutive patients were evaluated for visceral involvement, immunological profile, activity, severity scores, and quality of life. The vitamin D status was evaluated by measuring the 25hydroxy-hydroxyvitamin D serum levels.

Results

The mean vitamin D level was 17.06±9.13 ng/dL. Only 9.8% of the patients had optimal vitamin D levels; 66.66% of them had insufficient 25(OH)D levels, while 23.52% had deficient levels. No correlation was found between vitamin D concentration and age, sex, autoantibody profile, extent of skin involvement, or vitamin D supplementation. Vitamin D levels were correlated with the diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (p=0.019, r=0.353), diastolic dysfunction (p=0.033, r=−0.318), digital contractures (p=0.036, r=−0.298), and muscle weakness (p=0.015, r=−0.377) and had a trend for negative correlation with pulmonary hypertension (p=0.053, r=−0.29).

Conclusion

Low levels of vitamin D are very common in systemic sclerosis. Poor vitamin status seems to be related with a more aggressive disease with multivisceral and severe organ involvement, especially pulmonary and cardiac involvement.

Keywords: Systemic scleroderma, vitamin D, visceral involvement

Introduction

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is an autoimmune disease in which vascular damage and immune activation leads to the excessive accumulation of extracellular matrix in the skin and internal organs (1).

In SSc patients, vitamin D deficiency was identified to be frequent and associated with disease activity or phenotype characteristics such as pulmonary hypertension, lung involvement, and extensive cutaneous forms (2–8).

Vitamin D has pleiotropic effects that go beyond its traditional role in calcium homeostasis, which is related to vitamin D receptor (VDR) ubiquitous distribution (9). In the last few years, a large number of studies have suggested that vitamin D deficiency is a risk factor for a wide spectrum of acute and chronic illnesses including autoimmune diseases (9–10).

It has been documented that VDRs are present on the surface of antigen-presenting cells, natural killer cells, and B and T lymphocytes (11, 12), explaining multiple immunomodulatory effects on both innate and adaptive immune responses. In particular, vitamin D inhibits T helper-1 (Th1) lymphocytes and the production of Th1 cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-2, interferon gamma, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (13). Moreover, vitamin D reduces the level of other proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-17 and up-regulates anti-inflammatory mediators such as IL-4 and IL-10; further, it interferes with the differentiation and survival of dendritic cells (14).

Vitamin D receptor is present in many cells throughout the body including cardiomyocytes, vascular smooth muscle, and endothelium (15). Recent evidence has shown that 25hydroxyvitamin(OH)D deficiency is associated with vascular endothelial dysfunction in middle-aged and older adults and with a higher risk of developing incident cardiovascular disease (15). The mechanism of how vitamin D may protect individuals from cardiovascular disease has not yet been fully elucidated. Several mechanisms have been proposed including negatively regulating renin to lower the blood pressure (15), improving vascular compliance (15), decreased production of endothelium-derived contracting factors (16), increased vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression (17), decreased parathyroid hormone levels (15), and improved glycemic control (15).

Several studies have also proved the antifibrotic properties of vitamin D. The addition of 1,25hydroxy(OH)D3 to mesenchymal multipotent cells promotes the decreased expression of transforming growth factor beta-1 (TGF-β1) and plasminogen activator inhibitor (SERPINE1), which are two well-known profibrotic factors, and of collagen I, III, and other collagen isoforms and the increased expression of several antifibrotic factors such as bone morphogenetic protein-7, a TGF-β1 antagonist; matrix metalloproteinase-8, a collagen breakdown inducer; and follistatin, an inhibitor of the profibrotic factor myostatin (18). 1,25(OH)2D3 can also inhibit the profibrotic phenotype of lung fibroblasts and epithelial cells (19) and can block, at least partially, myofibroblastic transformation from interstitial fibroblasts induced by TGF-β1 (20).

Taking into consideration its immunomodulatory, cardioprotective, and antifibrotic properties, vitamin D could influence the three main pathogenic links of SSc.

Based on the data presented, we evaluated a group of scleroderma patients for the pathological significance of vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency.

Material and Methods

Patients

Fifty-one patients were included in this cross-sectional study. The patients were selected according to The European League Against Rheumatism 2013 criteria for SSc. They were evaluated for disease pattern; Rodnan score; musculo-articular, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, pulmonary, and renal involvement; inflammatory markers; autoantibodies (antinuclear, anticentromere, antiscleroderma-70); and cholesterol and triglyceride levels; nailfold capillaroscopy was also performed. Several questionnaires were completed: European Disease Activity Score (21), Medsger severity score (21), and health assessment questionnaire (HAQ)-disability index (22). Patients’ written consent was obtained according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by a local ethics committee.

Measurement of serum 25(OH)D level

Peripheral blood was collected in anticoagulant-free tubes and centrifuged for 5 min at 2000 rotations per min. The 25(OH)D level was measured in the sera by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit [25-Hydroxyvitamin D Total ELISA assay; DIASource® ImmunoAssays, Nivelles, Belgium] according to the manufacturer’s protocol. 25(OH)D levels were considered optimal when ≥30 ng/mL, insufficient when between 10 and 30 ng/mL, and deficient when under 10 ng/mL.

Statistics

All calculations were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0 (SPSS Inc.; Armonk, NY, USA). All data are presented as mean±standard deviation or percentages. Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney test was used to evaluate differences for nominal variables. The chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. Pearson’s bivariate correlation or Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used to evaluate the association between evaluated variables. The values of r>0.5 and p<0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of SSc patients

The patients’ demographic and clinical data are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data of systemic sclerosis patients

| Population | n=51 | Diffuse subset n=27 | Limited subset n=24 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 55.65±12.45 | 53.07±13.75 | 58.54±10.33 | 0.11 |

| Disease duration (years), mean (SD) | 11.7 (6.9) | 11.17 (6.54) | 12.29 (7.3) | 0.57 |

| Rodnan score, mean (SD) | 9.59 (5.01) | 13.11 (5.98) | 5.63 (2.16) | <0.001 |

| Digital ulcers | 41.2% | 29.63% | 54.16% | 0.07 |

| Digital contractures | 45.1% | 62.96% | 25% | 0.006 |

| Acroosteolysis | 21.56% | 33.33% | 8.33% | 0.02 |

| Muscle atrophy | 23.5% | 37.04% | 8.33% | 0.01 |

| Gastrointestinal involvement | 84.3% | 77.77% | 91.66 | 0.18 |

| sPAP mmHg, mean (SD) | 33.4 (13.94) | 34.12 (12.65) | 32.42 (15.84) | 0.69 |

| Renal crisis | 1.96% | 7.4% | 0% | 0.18 |

| Pulmonary fibrosis | 41.17% | 59.25% | 20.83% | 0.002 |

| Elevated ESR/CRP | 45.1% | 62.96% | 45.83% | 0.22 |

| Autoantibodies | ||||

| SCL70+ | 60.78% | 85.18% | 33.33% | 0.000 |

| ACA+ | 17.64% | 7.4% | 41.66% | 0.05 |

| SCL70+ ACA+ | 11.78% | 7.4% | ||

| SCL70-ACA- | 9.8% | 12.5% | ||

| Nailfold capillaroscopy | ||||

| Early | 7.9% | 9.52% | 6.25% | |

| Active | 34.2% | 38.09% | 31.25% | |

| Late | 52.6% | 52.38% | 47.62% | |

| Osteoporosis | 39.28% | 26.67% | 53.84% | 0.13 |

| Activity score | 3.43±2.14 | 4.06 (2.41) | 2.73 (1.55) | 0.02 |

| Severity score | 6.84±3.15 | 8 (3.23) | 5.54 (2.53) | 0.004 |

| HAQ, mean (SD) | 0.83±0.67 | 0.94 (0.66) | 0.7 (0.66) | 0.023 |

| 25(OH)D level (ng/mL) | 17.06±9.13 | 15.92±9.1 | 22.05±10.8 | 0.35 |

SD: standard deviation; sPAP: systolic pulmonary arterial pressure; DLCO: diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; SCL 70: antiscleroderma-70 autoantibodies; ACA: anticentromere antibodies; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP: C-reactive protein; HAQ: health assessment questionnaire

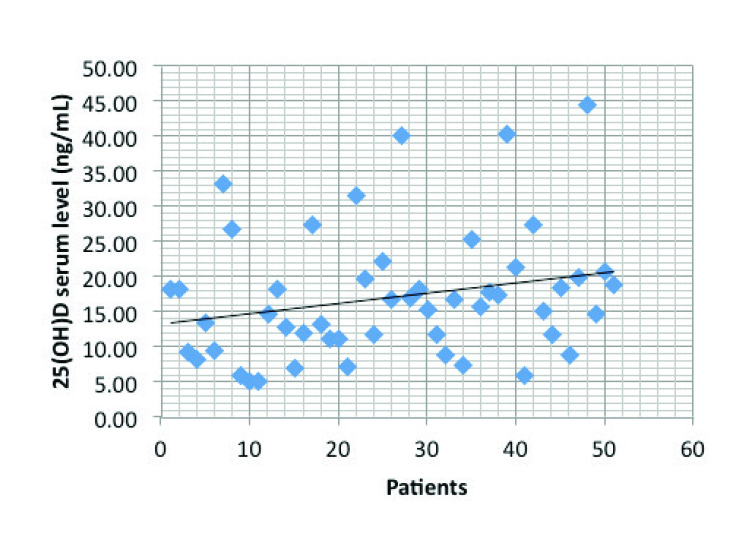

The mean vitamin D level was 17.06±9.13 ng/dL (Figure 1). Only 5 patients had optimal vitamin D levels (9.8%); 66.66% of the patients had insufficient 25(OH)D levels, while 23.52% had deficient levels.

Figure 1.

Distribution of 25(OH)D serum levels

The mean vitamin D level was 17.06±9.13 ng/dL. Most patients have insufficient 25(OH)D levels, and only 9.82% have optimal levels

Clinical differences between patients with normal and suboptimal vitamin D levels

Patients with low vitamin D levels had higher systolic pulmonary arterial pressure than those with normal 25(OH)D levels [25.25 (3.77) mmHg vs. 34.2 (14.33) mmHg, respectively; p=0.008)] and poor quality of life evaluated using HAQ (p=0.023). None of the patients with normal vitamin D levels developed cardiac involvement.

Clinical differences between patients with vitamin D insufficiency and deficiency

Patients with vitamin D deficiency developed more frequent systolic dysfunction (p=0.003), scleroderma renal crisis (p=0.001), muscle weakness (p=0.025), and muscle atrophy (p=0.002) and have poor quality of life (p=0.03) (Table 2).

Table 2.

The table reports the comparison of clinical data between patients with vitamin D insufficiency and those with vitamin D deficiency

| Parameters | Vitamin D insufficiency (n=34) | Vitamin D deficiency (12) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activity score, mean (SD) | 3.09 (2.07) | 3.43 (2.21) | 0.64 |

| Severity score, mean (SD) | 6.79 (3.26) | 7 (2.48) | 0.84 |

| Rodnan score, mean (SD) | 11.50 (6.77) | 8.76 (5.24) | 0.15 |

| Ulcers | 44.11% | 33.33% | 0.52 |

| Pulmonary fibrosis | 67.49% | 38.49% | 0.09 |

| Renal crisis | 2.94% | 8.33% | 0.001 |

| sPAP (mmHg), mean (SD) | 36.55 (19.98) | 33.34 (11.95) | 0.53 |

| Diastolic dysfunction | 30% | 45.45% | 0.36 |

| Systolic dysfunction | 5.88% | 25% | 0.03 |

| Muscle weakness | 55.88% | 91.66% | 0.025 |

| Muscle atrophy | 8.33% | 55.88% | 0.002 |

| Gastrointestinal involvement | 55.88% | 16.66% | 0.05 |

| HAQ, mean (SD) | 3.5 (3.2) | 4.9 (2.4) | 0.03 |

SD: standard deviation; sPAP: systolic pulmonary arterial pressure; HAQ: health assessment questionnaire

Clinical differences between patients with or without vitamin D supplementation

Thirteen patients (25.49%) received vitamin D supplementation. The mean 25(OH)D level was higher for patients with supplements, but the difference between groups failed to reach statistical significance (p=0.488). Patients with vitamin D supplementation developed less frequent digital ulcers compared with those without (30.76% vs 44.73%, respectively; p=0.04).

Vitamin D concentrations and clinical parameters

No correlation was found between vitamin D concentration and age, sex, autoantibody profile, SSc subset, skin involvement evaluated by the modified Rodnan skin score, articular involvement (synovitis or acroosteolysis), presence or previous history of ischemic digital ulcers, activity and severity scores, and inflammatory syndrome.

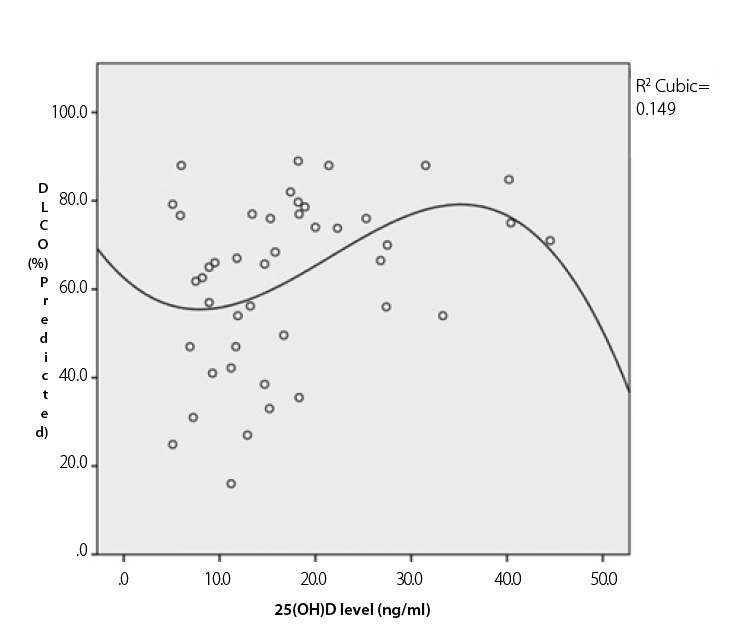

The mean vitamin D level correlated with pulmonary fibrosis (p=0.011, r=−0.355) and diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) (p=0.019, r=0.353) (Figure 2). The vitamin D status had a negative correlation with diastolic dysfunction (p=0.033, r=−0.318) and a trend for negative correlation with pulmonary hypertension (p=0.053, r=−0.29). Digital contractures and muscle weakness were also correlated with the 25(OH)D level (p=0.036, r=−0.298 vs. p=0.015, r=−0.377, respectively).

Figure 2.

Correlation between 25(OH)D levels and diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO)

The figure shows the correlation between vitamin D levels and DLCO (p=0.019, correlation coefficient=0.353) by Pearson’s bivariate correlation.

Discussion

Similar to previous reports (3–9), our study also showed a low vitamin D status in SSc (90.2%), with a mean 25(OH)D level of 17.06±9.3 ng/mL. Vitamin D deficiency in SSc may be linked to multiple risk factors: skin thickening and hyperpigmentation, insufficient sun exposure due to disability, or insufficient intake and malabsorption. In our study, patients with a normal vitamin D status had higher Rodnan scores than those with a suboptimal vitamin D status (p=0.23); further, patients with vitamin D insufficiency had higher Rodnan scores than those with vitamin D deficiency (p=0.15). No correlation was found between vitamin D serum levels (p=0.183) and Rodnan scores (p=0.124). Additionally, no difference was found when comparing 25(OH)D levels between diffuse and limited subsets; patients with Rodnan scores of >10 did not have significantly lower 25(OH)D levels than those with Rodnan scores of <10 (9.61±1.72 ng/mL vs. 8.11±1.81ng/mL, respectively; p=0.18). All these results suggest that cutaneous involvement is not the main cause for a poor vitamin D status in SSc.

Patients with vitamin D deficiency in the studied group had more severe disease than those with vitamin D insufficiency. Our results suggest that the vitamin D status could influence disease phenotype, especially lung and heart involvement.

A weak correlation between 25(OH)D level and systolic pulmonary arterial pressure was noticed (p=0.05, r=0.29) in the study group. Several studies reported that vitamin D deficiency is common among patients with pulmonary hypertension (23, 24). The mechanism through which vitamin D deficiency could induce pulmonary hypertension is not fully understood; it could be activation of the renin–angiotensin system (25), reduced expression of prostacyclin by vascular smooth muscle cells (25), or secondary hyperparathyroidism. The parathyroid hormone is known to increase mesenchymal stem cell proliferation and stimulates VEGF expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (26).

Important correlations were noticed between the vitamin D status and cardiovascular involvement. Patients in the group with optimal vitamin D levels neither had systolic or diastolic dysfunction nor rhythm and conduction disturbances, while those with vitamin D deficiency had the highest prevalence. Patients with vitamin D supplementation developed less digital ulcers (p=0.04). Primary myocardial involvement in SSc is related to repeated focal ischemic injury causing myocytes apoptosis, replacement with fibroblasts, and subsequent irreversible myocardial fibrosis (27). In mouse models, vitamin D deficiency is associated with energetic metabolic changes, cardiac inflammation, oxidative stress, fibrosis and apoptosis, cardiac hypertrophy, left chamber alterations, and systolic dysfunction. Furthermore, the restriction length influenced these cardiac changes (28). Vitamin D deficiency has been shown in observational and prospective studies to be associated with cardiovascular diseases including coronary artery disease, left ventricular hypertrophy, and systolic heart failure (29). On the other hand, in large population-based studies, 25(OH)D was not associated with better left ventricular systolic function when adjusted for other risk factors and for the season of vitamin D sampling (30).

Vitamin D also has some influence on musculo-articular involvement. Although results failed to reach statistical significance, patients with vitamin D deficiency developed more frequent synovitis than those with vitamin D insufficiency (25% vs. 20.58%, respectively; p=0.4). Patients with synovitis have lower 25(OH)D levels than those without synovitis (15.93±7.69 ng/mL vs. 20.36±12.21 ng/mL, respectively; p=0.061). These results may be closely related to the anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties of vitamin D. In the last few years, the possible role of vitamin D in the pathogenesis, activity, and treatment of inflammatory arthritis has been raised based on the results and observations of clinical and laboratory studies from laboratory models or patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The rationale for the relationship between vitamin D deficiency and rheumatoid arthritis is based on two facts: evidence indicate that patients with rheumatoid arthritis have vitamin D deficiency and the presence of 1.25(OH)2D and VDR in macrophages, chondrocytes, and synovial cells in the joints of these patients (31). There seems to be an inverse relationship between disease activity and vitamin D metabolite concentration in patients with inflammatory arthritis (31).

A negative correlation was also identified between the vitamin D status and muscle weakness (p=0.015, r=−0.37); patients with muscle weakness had lower 25(OH)D levels than those without (15.327±9.14 ng/mL vs. 20.24±8.45 ng/mL, respectively; p=0.06). Patients with vitamin D insufficiency developed significantly less muscle weakness (p=0.001) and muscle atrophy (p=0.002) compared to those with vitamin D deficiency. Vitamin D deficiency-associated myopathy has been known for more than 30 years; age-related sarcopenia is associated with VDR polymorphism. Vitamin D has genomic and non-genomic effects in skeletal muscle, impacting both calcium metabolism and protein transcription (32).

Several in vitro analyses have suggested key mechanistic pathways through which vitamin D decreases fibrosis in different tissue types (33). Recently, VDR expression was analyzed in SSc skin, experimental fibrosis, and human fibroblasts (34). VDR expression decreases in the fibroblasts of SSc patients and murine models of SSc in a TGF-β-dependent manner. The authors suggest that impaired VDR signaling with reduced VDR expression and decreased levels of its ligand may contribute to hyperactive TGF-β signaling and aberrant fibroblast activation in SSc (34). In our group, the vitamin D status was related to the clinical equivalent of fibrosis as digital contractures and pulmonary fibrosis.

The 25(OH)D level was negatively correlated with the presence of digital contractures (p=0.036, r=−0.029). Vitamin D serum levels were significantly lower in patients with digital contractures than in those without (19.40±10.22 ng/mL vs. 14.20±6.75ng/mL, respectively; p=0.042). Although results failed to reach statistical significance, patients with vitamin D deficiency have more digital contractures those with insufficient vitamin D level (58.33% vs. 44.11%, respectively; p=0.07), as did the patients with suboptimal levels compared to those with a normal vitamin D status (20% vs. 47.82%, respectively; p=0.235) and patients not receiving supplementation compared to those receiving supplementation (38.46% vs. 47.36%, respectively; p=0.36). There are no previous reports regarding this association.

Patients with a poor vitamin D status have more severe lung involvement. This finding confirms the results of other studies (2, 4, 8). The frequency of pulmonary fibrosis was 87.5% in the diffuse subset and 25% in patients with the limited form of SSc for patients with vitamin D deficiency (p=0.003) and 56.2% for the diffuse subset and 28.5% for the limited subset in patients with vitamin D insufficiency (p=0.04). Correlations were identified between 25(OH)D levels and lung involvement (p=0.011, r=−0.035) and DLCO (p=0.019, r=0.037). None of the patients with a normal vitamin D status had lung involvement. Multifactorial regression analysis concluded that compared to patients with an optimal vitamin D status, pulmonary fibrosis developed more often in patients vitamin D insufficiency, irrespective of the disease subset; when comparing the subsets of SSc, lung involvement developed more frequently in patients with diffuse form and vitamin D deficiency. To date, very few drugs are available to stabilize or improve lung function in randomized clinical trials, and their beneficial effect is quite small (34). Considering our findings, we may consider adding vitamin D as an adjuvant for immunosuppression.

As previously mentioned, studies on cells of murine origin incubation of mesenchymal multipotent cells with vitamin D decrease the expression of TGF-β1 and concomitantly reduce the expression of collagen I and III; moreover vitamin D is able to oppose the action of TGF-β1 on fibroblast proliferation and myofibroblast transdifferentiation, as demonstrated by the reduced expression of α-smooth muscle actin (18). Vitamin D also acts on the transdifferentiation of lung epithelial cells into myofibroblasts (19). These murine studies show a direct link between vitamin D and fibrosis pathways and may furnish a plausible explication of a more severe lung disease in SSc patients with hypovitaminosis D.

A study on 118 patients with interstitial lung disease, including 67 patients with connective tissue disorders, revealed significantly low vitamin D levels (35). In patients with connective tissue disorders, correlations between vitamin D level and forced vital capacity and DLCO were identified.

Although scleroderma renal crisis seems to be more frequent in patients with vitamin D deficiency in the group (p=0.001), the small number of patients raises doubts on the statistical significance of the results. Still, to our knowledge, this is the first study to report this association.

Taking into account the more severe musculo-articular, lung, and heart involvement in patients with suboptimal 25(OH)D levels, there is little doubt that the vitamin D status was related to the quality of life. Patients with a low vitamin D status had higher HAQs than those with normal 25(OH)D levels (p=0.03), as did the patients with vitamin D deficiency compared to those with vitamin D insufficiency (p=0.023).

We observed that a standard dose of vitamin D supplement does not correct the deficiency. This could have practical repercussions as our results strongly suggest the need for a higher supplement dosage, but this remains to be validated together with potential effects on the clinical phenotype of vitamin D normalization.

Our study has some limitations. One is the lack of a control group of healthy subjects. The design was cross-sectional; therefore, the direction of associations could not be conclusively determined. Moreover, the data could be confounded by the fact that patients with severe organ involvement had worse health status, and thus had a diet lacking in vitamin D or had less ultraviolet exposure. Another point is that we did not assess the dietary intake of vitamin D.

The role of vitamin D in the pathogenesis of autoimmune disease is still unclear. Well-designed trials to determine whether vitamin D could be a modifiable factor able to interfere with SSc evolution are required.

In conclusion, low levels of vitamin D are very common in patients with SSc; other causes except the extent of skin involvement are thought to be involved. Poor vitamin status seems to be related with a more aggressive disease with multivisceral and severe organ involvement, especially pulmonary and cardiac involvement. Usual vitamin D supplementation does not correct vitamin D deficiency in scleroderma patients. Well-designed trials to determine whether vitamin D could be a modifiable factor able to interfere with SSc evolution are required.

Footnotes

Ethics Committee Approval: Ethics committee approval was received for this study from the ethics committee of Sf Maria Clinica Hospital.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patients.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept - L.G., R.I.; Design - L.G., T.G.; Supervision - V.B., R.I.; Data Collection and/or Processing - L.G., T.G.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - T.G., L.G.; Writer - L.G.; Critical Review - V.B., R.I.; Other - I.S., D.P., A.B., F.B., D.O., A.B., C.C., M.N.

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

Financial Disclosure: The author declared that this study has received no financial support.

References

- 1.Chizzolini C, Brembilla NC, Montanari E, Truchetet ME. Fibrosis and immune dysregulation in systemic sclerosis. Autoimmunity Rev. 2011;10:276–81. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2010.09.016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vacca A, Cormier C, Piras M, Mathieu A, Kahan A, Allanore Y. Vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency in 2 independent cohorts of patients with systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:1924–9. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.081287. http://dx.doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.081287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belloli L, Ughi N, Marasini B. Vitamin D in systemic sclerosis. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:145–6. doi: 10.1007/s10067-010-1564-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10067-010-1564-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caramaschi P, Dalla Gassa A, Ruzzenente O, Volpe A, Ravagnani V, Tinazzi I. Very low levels of vitamin D in systemic sclerosis patients. Clin Rhematol. 2010;29:1419–25. doi: 10.1007/s10067-010-1478-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10067-010-1478-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braun-Moscovici Y, Furst DE, Markovits D, Rozin A, Clements PJ, Nahir AM, et al. Vitamin D, parathyroid hormone and acroosteolysis in SSc. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:2201–5. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.071171. http://dx.doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.071171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calzolari G, Data V, Carignola R, Angeli A. Hypovitaminosis D in sistemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:2844. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090439. http://dx.doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.090439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnson Y, Amital H, Agmon-Levin N, Alon D, Sánchez-Castañón M, López-Hoyos M, et al. Serum 25OH vitamin D concentrations are linked with various clinical aspects in patients with SSc: a retrospective cohort study & review of literature. Autoimmune Rev. 2011;10:490–4. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.02.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rios Fernandez R, Roldan CF, Callejas Rubio JL, Centeno N. Vitamin D deficiency in a cohort of patients with systemic scleroderma from S of Spain. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:1355. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.091143. http://dx.doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.091143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pludowski P, Holick MF, Pilz S, Wagner CL, Hollis BW, Grant WB, et al. Vitamin D effects on musculoskeletal health, immunity, autoimmunity, cardiovascular disease, cancer, fertility, pregnancy, dementia and mortality-a review of recent evidence. Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12:976–89. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.02.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang CY, Leung PS, Adamopoulos IE, Gershwin ME. The implication of vitamin D and autoimmunity: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2013;45:217–26. doi: 10.1007/s12016-013-8361-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12016-013-8361-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bikle D. Vitamin D: newly discovered actions require reconsideration of physiologic requirements. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21:375–84. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2010.01.003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aranow C. Vitamin D and the Immune System. J Investig Med. 2011;59:881–6. doi: 10.231/JIM.0b013e31821b8755. http://dx.doi.org/10.2310/JIM.0b013e31821b8755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prietl B, Treiber G, Pieber TR, Amrein K. Vitamin D and immune function. Nutrients. 2013;5:2502–21. doi: 10.3390/nu5072502. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/nu5072502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dickie LJ, Church LD, Coulthard LR, Mathews RJ, Emery P, McDermott MF. Vitamin D3 down-regulates intracellular Toll-like receptor 9 expression and Toll-like receptor 9-induced IL-6 production in human monocytes. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:1466–71. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq124. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keq124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jablonski KL, Chonchol M, Pierce GL, Walker AE, Seals 25-Hydroxyvitamin D deficiency is associated with inflammation-linked vascular endothelial dysfunction in middle-aged and older adults. Hypertension. 2011;57:63–9. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.160929. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.160929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong MS, Delansorne R, Man RY, Vanhoutte PM. Vitamin D derivatives acutely reduce endothelium-dependent contractions in the aorta of the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:289–96. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00116.2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00116.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al Mheid I, Patel R, Murrow J, Morris A, Rahman A, Fike L, et al. Vitamin D status is associated with arterial stiffness and vascular dysfunction in healthy humans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:186–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.051. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Artaza JN, Norris KC. Vitamin D reduces the expression of collagen and key profibrotic factors by inducing an antifibrotic phenotype in mesenchymal multipotent cells. J Endocrinol. 2009;200:207–21. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0241. http://dx.doi.org/10.1677/JOE-08-0241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramirez AM, Wongtrakool C, Welch T, Steinmeyer A, Zügel U, Roman J. Vitamin D inhibition of pro-fibrotic effects of transforming growthfactor β1 in lung fibroblasts and epithelial cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;118:142–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.11.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LI Y, Spataro BC, Yang J, Dai C, Liu Y. D3 inhibits renal interstitial myofibroblast activation by inducing hepatocyte growth factor expression. Kidney Int. 2005;68:1500–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00562.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hudson M, Steele R Canadian Scleroderma Research Group (CSRG) Baron M. Update on indices of disease activity in systemic sclerosis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2007;37:93–8. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2007.01.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson SR, Lee P. The HAQ disability index in scleroderma. Rheumatology. 2004;43:1200–1. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh288. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keh288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Demir M, Uyan U, Keçeoçlu S, Demir C. The relationship between vitamin D deficiency and pulmonary hypertension. Prague Med Rep. 2013;114:154–61. doi: 10.14712/23362936.2014.17. http://dx.doi.org/10.14712/23362936.2014.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bogaard HJ, Al Husseini A, Farkas L, Farkas D, Gomez-Arroyo J, Abbate A, et al. Severe pulmonary hypertension: The role of metabolic and endocrine disorders. Pulm Circ. 2012;2:148–54. doi: 10.4103/2045-8932.97592. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/2045-8932.97592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wakasugi M, Noguchi T, Inoue M, Kazama Y, Tawata M, Kanemaru Y, et al. Vitamin D3 stimulates the production of prostacyclin by vascular smooth muscle cells. Prostaglandins. 1991;42:127–36. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(91)90072-n. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0090-6980(91)90072-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rashid G, Bernheim J, Green J, Benchetrit S. Parathyroid hormone stimulates the endothelial expression of vascular endothelial growth factor. Eur J Clin Invest. 2008;38:798–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2008.02033.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2362.2008.02033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Desai CS, Bernheim J, Green J, Benchetrit S. Systemic sclerosis and the heart: current diagnosis and management. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23:545–54. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32834b8975. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/BOR.0b013e32834b8975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Assalin HB, Rafacho BP, dos Santos PP, Ardisson LP, Roscani MG, Chiuso-Minicucci F, et al. Impact of the length of vitamin D deficiency on cardiac remodeling. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:809–16. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.000298. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.000298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang L, Song Y, Manson JE, Pilz S, März W, Michaëlsson K, et al. Circulating 25-hydroxy-vitamin D and risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:819–29. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.967604. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.967604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamycheva E, Wilsgaard T, Schirmer H, Jorde R. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and left ventricular systolic function in a non-smoking population: the Tromsø Study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:490–5. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs210. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurjhf/hfs210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel S, Farragher T, Berry J, Bunn D, Silman A, Symmons D. Association between serum vitamin D metabolite levels and disease activity in patients with early inflammatory polyarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2143–9. doi: 10.1002/art.22722. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/art.22722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamilton B. Vitamin D and human skeletal muscle. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20:182–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01016.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zerr P, Vollath S, Palumbo-Zerr K, Tomcik M, Huang J, Distler A, et al. Vitamin D receptor regulates TGF-β signalling in systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:e20. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204378. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iudici M, Moroncini G, Cipriani P, Giacomelli R, Gabrielli A, Valentini G. Where are we going in the management of interstitial lung disease in patients with systemic sclerosis? Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14:575–8. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2015.02.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hagaman JT, Panos RJ, McCormack FX, Thakar CV, Wikenheiser-Brokamp KA, Shipley RT, et al. Vitamin D Deficiency and Reduced Lung Function in Connective Tissue-Associated Interstitial Lung Diseases. Chest. 2011;139:353–60. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0968. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.10-0968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]