Abstract

Importance

Several randomized trials have demonstrated the efficacy of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in preventing human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) acquisition. Little is known about adherence, sexual practices, and overall effectiveness when PrEP is implemented in sexual transmitted infection (STI) and community-based clinics.

Objective

To assess PrEP adherence, sexual behaviors, and incidence of STIs and HIV in a cohort of men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women initiating PrEP in the United States.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Demonstration project conducted from October 2012 to February 2015, among MSM and transgender women in 2 STI clinics in San Francisco, California and Miami, Florida, and a community health center in Washington, DC.

Intervention

Daily, oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine was provided free of charge for 48 weeks. All participants received HIV testing, brief client-centered counseling, and clinical monitoring.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Tenofovir diphosphate (TFV-DP) concentrations in dried blood spots (DBS); self-reported numbers of anal sex partners and episodes of condomless receptive anal sex; STI/HIV incidence.

Results

Overall, 557 participants initiated PrEP, with 78% retained through 48 weeks. Based on 294 participants with DBS testing, 80-86% had protective DBS levels (consistent with ≥4 doses/week) at follow-up visits. African-Americans (57%, p=0.003) and those from the Miami site (65%, p<0.001) were less likely to have protective levels, while those with stable housing (87%, p=0.02) and reporting ≥2 condomless anal sex partners in the past 3 months (89%, p=0.01) were more likely to have protective levels. Mean anal sex partners declined during follow-up, while the proportion engaging in condomless receptive anal sex remained stable. Overall STI incidence was high (90/100 person-years), but did not increase over time. Two individuals became HIV-infected during follow-up (HIV incidence 0.43%, 95% CI 0.05-1.54); both had TFV-DP levels consistent with <2 doses/week at seroconversion.

Conclusions and Relevance

HIV incidence was extremely low, despite a high incidence of STIs in a large US PrEP demonstration project. Adherence was higher among those with higher reported risk behavior. Interventions that address racial and geographic disparities and housing instability may increase PrEP impact.

Keywords: Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), HIV prevention, Men who have sex with men (MSM), sexually transmitted diseases (STD), implementation, adherence, retention, disparities

Introduction

In 2010, the iPrEx trial of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) using daily oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC) demonstrated an overall 44% reduction in HIV acquisition among men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women receiving PrEP, and >90% efficacy among those with detectable drug in blood.1 Following two additional randomized trials also demonstrating safety and efficacy,2,3 this PrEP formulation was approved in the US for the prevention of sexually acquired HIV infection in 2012. Two recent studies of daily or intermittent PrEP among MSM confirmed high PrEP efficacy.4,5

MSM account for over two-thirds of new HIV infections in the US, and are the only risk group in whom infection rates are rising.6 Sexually transmitted infection (STI) and community-based clinics serving MSM are promising clinical sites for PrEP delivery,7 yet little is known about PrEP use in these settings. Concerns have been raised regarding PrEP implementation, including risk compensation,8,9 poor adherence,10 drug resistance,11 and safety and toxicity.12 We report results of the Demo Project, a prospective, open-label demonstration project assessing PrEP adherence, sexual practices, safety, and HIV/STI incidence among MSM and transgender women in three US metropolitan areas heavily impacted by HIV.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

The Demo Project enrolled participants from municipal STI clinics in San Francisco and Miami and a community health center in Washington, DC from October 2012 to January 2014. These clinics have access to large populations of at-risk MSM, with annual HIV seroconversion rates of 2.3%-4%.13 Participants were eligible if they were male at birth and 18 years or older; fluent in English or Spanish; had a negative rapid HIV antibody test at screening and enrollment and a negative 4th generation antibody/antigen (Ag/Ab) test at screening; had creatinine clearance ≥60 ml/min and a urine dipstick with negative or trace protein; and reported any of the following in the last 12 months: condomless anal sex with ≥2 male or transgender female partners; ≥2 episodes of anal sex with ≥1 HIV-infected partner; or sex with a male/transgender female partner and having a diagnosis of syphilis or rectal gonorrhea or chlamydia. Individuals with serious active medical conditions, a history of pathologic fracture, hepatitis B surface antigen positivity, or taking nephrotoxic medications were excluded. Written informed consent was obtained at screening, and eligible individuals returned for enrollment and were dispensed one month of TDF/FTC. The sample size allowed us to estimate proportions within margins of sampling error of +/− 4.4%, and to detect adjusted odds ratios of 1.7-2.3, depending on predictor and outcome prevalence.

Participants returned for clinic visits at 4, 12, 24, 36, and 48 weeks for HIV/STI testing, clinical monitoring, and PrEP dispensing. Participants were encouraged to return 4 weeks after stopping PrEP for a final evaluation and HIV test. Brief, client-centered counseling was provided at all visits [eMethods1]. Retention procedures were limited, with up to 3 contact attempts after a missed visit. Participants received $25 for each scheduled visit. PrEP was discontinued in seroconverters, who received counseling, partner services, and linkage to HIV primary care. TDF/FTC PrEP (donated by Gilead Sciences) and HIV/STI testing and safety monitoring (supported by the clinic or study funds) were provided free to participants. Among the 3 study sites, only the DC site offered PrEP outside the Demo Project. The protocol was approved by local institutional review boards.

Measures

PrEP adherence and engagement

PrEP adherence was measured several ways. At each visit, a self-reported adherence rating scale14 was collected by interviewer-administered questionnaire, pill counts were performed, and the medication possession ratio (MPR), defined as the number of dispensed pills divided by the number of days between visits,15 was calculated. Dried blood spots (DBS) intended for measurement of tenofovir diphosphate (TFV-DP) concentrations [eMethods2] were collected at all scheduled follow-up visits, and at any visit where PrEP was stopped. TFV-DP concentrations were measured in approximately 100 randomly selected participants per site; in addition, a decision was made after completion of enrollment to perform DBS testing in all Black and transgender participants, who were under-represented in the overall sample.

Engagement with PrEP at each visit was assessed using a 5-level ordinal measure, where the lowest level of engagement was missing the visit, and increasing levels of engagement were identified for those attending the visit based on DBS concentration levels: below limits of quantitation (BLQ), <2 (<350 fmol/punch), 2-3 (350-699 fmol/punch), or ≥4 (≥700 fmol/punch) doses/week. This categorization of DBS concentrations was used in iPrEx OLE16 and derived from previous PK modeling studies.17

Sexual and drug-use behaviors

Sexual behaviors during the prior 3 months were assessed at screening and every 12 weeks by an interviewer-administered questionnaire, including total number of anal sex partners and number of episodes of insertive and receptive anal sex, with and without condoms. Participants were also asked about use of alcohol, marijuana, poppers, cocaine, amphetamines, heroin, sedatives, Ecstasy, and erectile dysfunction (ED) drugs in the past 3 months. Polysubstance use was defined as using ≥3 of the following: poppers, cocaine, amphetamines, sedatives, ecstasy, and ED drugs.18

HIV/STI testing

HIV testing was performed at all visits using a rapid HIV antibody test (Clearview Stat-Pak/Complete) and a fourth generation HIV Ag/Ab test (Architect; Abbott Diagnostics). Additionally, SF participants had pooled HIV RNA (10 samples/pool) conducted for acute HIV screening, as standard practice in that clinic.19 In Miami and DC, an individual HIV RNA (Aptima; GenProbe or Taq-man V.20; COBAS) was performed at enrollment to screen for acute HIV. HIV seroconverters had HIV RNA viral load and resistance testing performed by genotyping and minor variant assays20 [eMethods3]. Urine specimens and rectal and pharyngeal swabs were tested quarterly for Neisseria gonorrhoeae (GC) and Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) using the Aptima Combo-2 nucleic acid amplification test (Genprobe Diagnostics). Serologic testing for syphilis was performed quarterly with a VDRL or RPR and confirmed with a fluorescent treponemal antibody-absorption test.

Safety monitoring

A clinical assessment for adverse events was performed at all follow-up visits [eMethods4]. Serum creatinine was measured at screening and quarterly, and creatinine clearance was estimated using the Cockroft-Gault equation.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 13.1 (College Station, TX). Logistic models were used to assess baseline correlates of retention at 48 weeks. Our primary adherence outcome was having protective DBS levels consistent with ≥4 doses/week [eMethods5]. A generalized estimating equations (GEE) logistic model was used to evaluate baseline and time-dependent correlates of having protective DBS levels at each follow-up visit. Factors associated with the outcome (p<0.10) after adjustment for site and visit were retained in the final model. For analyses of adherence and PrEP engagement, participants with DBS results were weighted to be representative of all those attending each visit. The association of PrEP engagement at week 4 with engagement at week 48 was assessed using a proportional-odds model. Trends in sexual behavior and drug use were evaluated using GEE logistic and Poisson models. Follow-up for HIV/STI incidence started at enrollment and ended at the last visit with an HIV or STI test, respectively.

Results

PrEP uptake and baseline characteristics of Demo Project participants were previously described.21 Overall, 132 (24%) had an HIV-positive primary partner at baseline, including 122 (92%) who were on antiretroviral therapy and 107 (81%) who were virally suppressed. However, 67% of those with a virally suppressed primary partner reported >1 anal sex partner in the past 3 months. At baseline, any recreational drug use was reported by 74%, polysubstance use by 20%, amphetamines by 15%, and injection drugs by 1.6%. Testosterone or anabolic steroid use was rare (2.5%).

Among 557 enrolled participants, 25 (4.5%) had no follow-up visits, while 69% completed all five. Retention at week 48 was 78% overall, and 79% among the 294 selected for DBS testing; total follow-up was 481 person-years. Baseline correlates of retention at week 48 are shown in Table 1. After adjusting for site, prior PrEP knowledge and reporting condomless receptive anal sex (ncRAI) at baseline were associated with being retained.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of participants retained through the end of study.

| Characteristic | Retained N (%)† (n=437) |

Not retained N (%) (n=120) |

Unadj. p value |

Adj. p value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Site | ||||

| San Francisco | 253 (84.3) | 47 (15.7) | <0.001 | N/A |

| Miami | 98 (62.4) | 59 (37.6) | ||

| Washington DC | 86 (86.0) | 14 (14.0) | ||

|

| ||||

| Age, No. (%) | ||||

| 18-25 | 77 (68.8) | 35 (31.3) | 0.009 | 0.12 |

| 26-35 | 161 (77.0) | 48 (23.0) | ||

| 36-45 | 115 (85.8) | 19 (14.2) | ||

| >45 | 84 (82.4) | 18 (17.7) | ||

|

| ||||

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | ||||

| White | 226 (85.0) | 40 (15.0) | 0.002 | 0.53 |

| Latino | 139 (72.4) | 53 (27.6) | ||

| Black | 25 (62.5) | 15 (37.5) | ||

| Asian | 21 (80.8) | 5 (19.2) | ||

| Other | 26 (81.3) | 6 (18.8) | ||

|

| ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 430 (78.5) | 118 (21.5) | 0.65 | 0.49 |

| Transgender woman | 5 (71.4) | 2 (28.6) | ||

| Other | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | ||

|

| ||||

| Education level. No. (%) | ||||

| ≤ High School | 55 (67.1) | 27 (32.9) | 0.04 | 0.41 |

| Some college | 119 (78.8) | 32 (21.2) | ||

| College graduate | 156 (79.6) | 40 (20.4) | ||

| Any post graduate | 107 (83.6) | 21 (16.4) | ||

|

| ||||

| Income, No. (%) | ||||

| <$20,000 | 128 (69.6) | 56 (30.4) | <0.001 | 0.07 |

| $20,000-$59,999 | 158 (81.0) | 37 (19.0) | ||

| ≥$60,000 | 139 (87.4) | 20 (12.6) | ||

|

| ||||

| Health insurance, No. (%) | ||||

| No | 149 (71.6) | 59 (28.4) | 0.002 | 0.28 |

| Yes | 288 (82.8) | 60 (17.2) | ||

|

| ||||

| Living situation, No. (%) | ||||

| Rent or own housing | 362 (81.2) | 36 (32.4) | 0.002 | 0.07 |

| Other (live with friends/family, public housing, homeless) | 75 (67.6) | 84 (18.8) | ||

|

| ||||

| Referral status, No. (%) | ||||

| Self-referred | 252 (84.6) | 74 (28.6) | <0.001 | 0.08 |

| Clinic-referred | 185 (71.4) | 46 (15.4) | ||

|

| ||||

| Prior PrEP knowledge, No, (%) | ||||

| No | 91 (64.1) | 51 (35.9) | <0.001 | 0.01 |

| Yes | 346 (83.4) | 69 (16.6) | ||

|

| ||||

| ncRAI, past 3 mo, at baseline, No.(%) | ||||

| No | 125 (68.3) | 58 (31.7) | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| Yes | 312 (83.4) | 62 (16.6) | ||

|

| ||||

| Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) use at baseline visit, No. (%) | ||||

| No | 422 (78.4) | 116 (21.6) | 0.96 | 0.63 |

| Yes | 15 (79.0) | 4 (21.1) | ||

|

| ||||

| Alcohol: ≥5 drinks/day when drinking, past 3 mo | ||||

| No | 388 (79.2) | 102 (20.8) | 0.29 | 0.58 |

| Yes | 47 (73.4) | 17 (26.6) | ||

|

| ||||

| Any recreational drug use, past 3 mo | ||||

| No | 111 (77.6) | 32 (22.4) | 0.79 | 0.56 |

| Yes | 325 (78.7) | 88 (21.3) | ||

|

| ||||

| Amphetamine use, past 3 mo | ||||

| No | 365 (77.3) | 107 (22.7) | 0.10 | 0.36 |

| Yes | 71 (85.5) | 12 (14.5) | ||

|

| ||||

| Polysubstance use, past 3 mo‡ | ||||

| No | 342 (77.0) | 102 (23.0) | 0.11 | 0.36 |

| Yes | 94 (83.9) | 18 (16.1) | ||

|

| ||||

| Injection drug use, past 3 mo | ||||

| No | 429 (78.4) | 118 (21.6) | 0.96 | 0.55 |

| Yes | 7 (77.8) | 2 (22.2) | ||

|

| ||||

| Use of testosterone or anabolic steroids, past 3 mo | ||||

| No | 425 (78.3) | 118 (21.7) | 0.51 | 0.48 |

| Yes | 12 (85.7) | 2 (14.3) | ||

Retained participants include those who completed their 48 week visit, regardless of prior missed visits.

Adjusted for site; unadj = unadjusted; adj. = adjusted. No.= number. ncRAI = condomless receptive anal sex; N/A = not applicable

Polysubstance use defined as use of 3 or more of the following substances in the past 3 months: poppers, ecstasy, GHB, cocaine, methamphetamine, erectile dysfunction drugs.

PrEP adherence and engagement

Mean PrEP adherence across visits was 82% by pill counts and 86% by MPR. Self-rated adherence was very good or excellent at 87% of visits. Based on 1201 DBS samples provided by 294 participants who attended follow-up visits, DBS TFV-DP concentrations were in the protective range among an estimated 86%, 85%, 82%, 85%, and 80% of participants at weeks 4, 12, 24, 36, and 48 respectively. In multivariable analyses, African-American participants and those from Miami were less likely to have protective DBS levels, while those who had stable housing and reported ≥2 condomless anal sex partners in the past 3 months were more likely to have protective levels (Table 2). Trajectories of drug concentrations over time are shown graphically [eFigure]. Among participants with ≥2 DBS samples tested, 63% had DBS levels ≥4 doses/week at all visits tested and 2.9% always had DBS levels <2 doses/week.

Table 2. Correlates of DBS levels consistent with protective DBS levels (4 or more doses per week)¥ (N=294).

| Characteristic | # subjects tested† |

≥4 doses/ week (%)‡ |

OR (95% CI)* | P value | AOR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Site | ||||||

| San Francisco | 103 | 90 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Miami | 95 | 65 | 0.21 (0.12-0.37) | <0.001 | 0.32 (0.17-0.60) | <0.001 |

| Washington DC | 96 | 88 | 0.89 (0.47-1.70) | 0.73 | 1.08 (0.54-2.19) | 0.82 |

|

| ||||||

| Age, No. (%) | ||||||

| 18-25 | 62 | 78 | Reference | |||

| 26-35 | 109 | 85 | 1.41 (0.78-2.56) | 0.25 | ||

| 36-45 | 70 | 83 | 1.28 (0.64-2.55) | 0.49 | ||

| >45 | 53 | 87 | 1.97 (0.91-4.28) | 0.09 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | ||||||

| White | 130 | 91 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Latino | 98 | 77 | 0.68 (0.35-1.30) | 0.24 | 0.81 (0.41-1.61) | 0.55 |

| Black | 33 | 57 | 0.22 (0.10-0.47) | 0.0001 | 0.28 (0.12-0.64) | 0.003 |

| Asian | 16 | 84 | 0.48 (0.13-1.80) | 0.28 | 0.72 (0.17-3.03) | 0.65 |

| Other | 17 | 82 | 0.43 (0.13-1.35) | 0.15 | 0.42 (0.13-1.38) | 0.15 |

|

| ||||||

| Education level. No. (%) | ||||||

| ≤ High School | 37 | 72 | Reference | |||

| Some college | 79 | 80 | 1.08 (0.57-2.07) | 0.81 | ||

| College graduate | 178 | 88 | 1.76 (0.94-3.31) | 0.08 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Income, No. (%) | ||||||

| <$20,000 | 99 | 77 | Reference | |||

| $20,000-$59,999 | 96 | 87 | 1.72 (0.97-3.06) | 0.06 | ||

| ≥$60,000 | 88 | 87 | 1.12 (0.55-2.29) | 0.75 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Health insurance, No. (%) | ||||||

| No | 108 | 74 | Reference | |||

| Yes | 185 | 88 | 1.71 (1.03-2.85) | 0.04 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Living situation, No. (%) | ||||||

| Rent or own housing | 68 | 87 | 2.32 (1.39-3.88) | 0.001 | 2.02 (1.14-3.55) | 0.02 |

| Other | 226 | 70 | Reference | Reference | ||

|

| ||||||

| Referral status, No. (%) | ||||||

| Clinic-referred | 150 | 77 | Reference | |||

| Self-referred | 144 | 89 | 1.65 (0.97-2.83) | 0.07 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Prior PrEP knowledge, No, (%) | ||||||

| No | 88 | 76 | Reference | |||

| Yes | 206 | 86 | 0.98 (0.57-1.68) | .95 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Depression, No. (%) | ||||||

| PHQ-2 score <2 | 261 | 83 | Reference | |||

| PHQ-2 score ≥2 | 33 | 85 | 0.96 (0.57-1.63) | 0.89 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Condomless receptive anal sex, past 3 mo | ||||||

| No | 107 | 79 | Reference | |||

| Yes | 187 | 86 | 1.22 (0.79-1.89) | 0.37 | ||

|

| ||||||

| # condomless anal sex partners, past 3 mo | ||||||

| 0-1 | 105 | 75 | Reference | Reference | ||

| ≥2 | 189 | 89 | 1.95 (1.26-3.01) | 0.003 | 1.82 (1.14-2.89) | 0.01 |

|

| ||||||

| Alcohol: ≥5 drinks/day when drinking, past 3 mo | ||||||

| No | 265 | 84 | Reference | |||

| Yes | 29 | 82 | 1.02 (0.54-1.92) | 0.95 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Recreational drug use, past 3 mo | ||||||

| No | 89 | 79 | Reference | |||

| Yes | 205 | 86 | 1.29 (0.83-2.00) | 0.26 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Amphetamine use, past 3 mo | ||||||

| No | 253 | 83 | Reference | |||

| Yes | 41 | 91 | 1.88 (0.85-4.18) | 0.12 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Testosterone/anabolic steroid use, past 3 mo | ||||||

| No | 288 | 84 | Reference | |||

| Yes | 6 | 69 | 0.57 (0.10-3.37) | 0.53 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Injection drug use, past 3 mo | ||||||

| No | 289 | 84 | Reference | |||

| Yes | 5 | 76 | 0.40 (0.10-1.56) | 0.19 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Erectile Dysfunction drug use, past 3 mo | ||||||

| No | 204 | 80 | Reference | |||

| Yes | 90 | 90 | 1.77 (1.02-3.06) | 0.04 | ||

Analysis includes all participants who had DBS tested at a given visit.

For time dependent covariates, distribution of participants reflects the first visit where DBS was tested.

Unadjusted prevalence of having DBS levels consistent with ≥4 doses/week, weighted by site to reflect the full cohort and averaged across weeks.

ORs only adjusted for site; DBS=dried blood spots; No.=number; mo.= month; OR=odds ratio; AOR=adjusted odds ratio. Multivariable model included site, race/ethnicity, education, health insurance, housing status, referral status, number of condomless anal sex partners, and erectile dysfunction drug use.

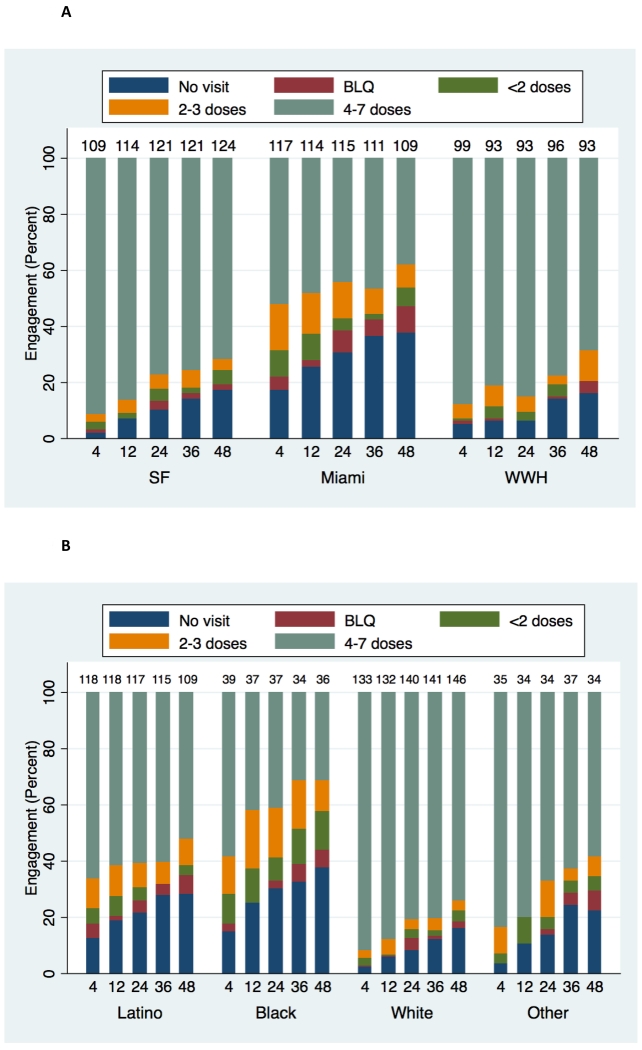

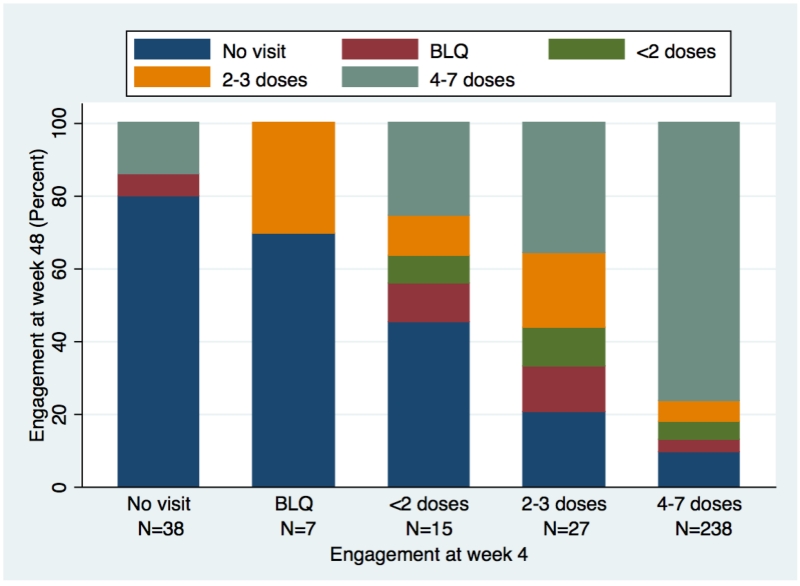

PrEP engagement (including visit attendance and adherence) varied by site and race/ethnicity (both p<0.0005) (Figure 1). Furthermore, engagement at week 4 strongly correlated with week 48 engagement (p<0.0005, Figure 2). PrEP was interrupted 86 times among 84 (15%) participants for reasons other than loss to follow-up, HIV seroconversion, or study completion, for a mean of 65 days, accounting for 24% of their follow-up; PrEP was restarted in 15 (18%). Interruptions were mostly due to participant preference, including experienced side effects (25 times), concern about long-term side effects (16 times), and low self-perceived HIV risk (21 times). Among participants who stopped PrEP due to low perceived risk, 63% reported ncRAI at that visit.

Figure 1. PrEP engagement, by visit week and site (Figure 1A) and race/ethnicity (Figure 1B).

A: Distribution of PrEP engagement (visit attendance and adherence by DBS concentrations) by visit week and study site. BLQ=below limit of quantitation. Numbers at top of each bar indicate number of participants contributing data at each time point.

B: Distribution of PrEP engagement (visit attendance and adherence by DBS concentrations) by visit week and race/ethnicity. BLQ=below limit of quantitation. Numbers at top of each bar indicate number of participants contributing data at each time point.

Figure 2. PrEP engagement at week 48, based on engagement at week 4.

Proportion of participants with no visit attendance or DBS concentrations in different adherence categories at week 48, stratified by visit attendance and DBS concentrations at week 4. BLQ=below limit of quantitation. This analysis includes 325 participants, 287 of whom had DBS tested at week 4, and 38 who missed the week 4 visit.

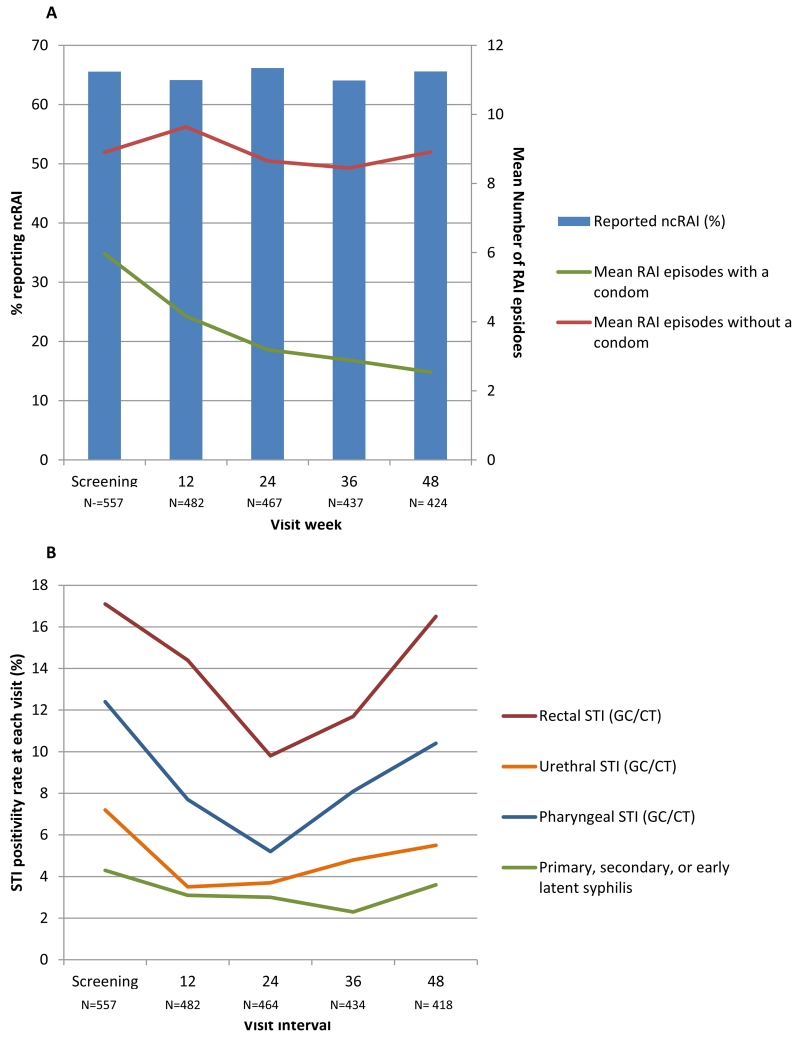

Sexual and drug use behaviors and STIs

Mean number of anal sex partners in the past 3 months declined from baseline to week 48 (10.9 to 9.3, p=0.04). Two-thirds (66%) reported ncRAI at baseline, which remained stable during follow-up (p=0.99, Figure 3A). Overall numbers of RAI episodes in the past 3 months decreased (p=0.007), driven by a decline in episodes with a condom (p<0.0001); episodes without a condom were stable (p=0.73). Site differences in sexual risk trajectories were observed, with increases in ncRAI (71% to 76%) and ncRAI episodes (8.4 to 11) seen only in San Francisco (p for interaction <0.05 for both). Use of any recreational drugs (p=0.42), amphetamines (p=0.41), heavy alcohol (≥5 drinks/day, p=0.81), and poppers (p=0.59) were stable, while use of powder cocaine (20% to 14%, p=0.006) and club drugs (23% to 18%, p=0.02) decreased.

Figure 3. Sexual Behaviors and STIs in the Demo Project.

A: Proportion of participants reporting condomless receptive anal sex (ncRAI) and mean number of receptive anal sex episodes with and without a condom.

B: Percent of STI tests that were positive during each visit interval, by anatomic site. The week 48 visit interval includes testing performed at the optional follow-up visit 4 weeks after week 48.

Overall, 26% of participants had early syphilis, GC, or CT at baseline, and 51% were diagnosed with ≥1 STI during follow-up. The proportion of participants who had early syphilis or a GC/CT infection at the urethra, rectum, or pharynx during each visit interval is shown in Figure 3B. Rectal and pharyngeal STI positivity decreased from baseline to week 24, then increased (p<0.05). STI incidence per 100 person-years was 48 (95% CI 42-55) for CT, 43 (37-49) for GC, 12 (9.4-16) for syphilis, and 90 (81-99) for any STI; in each case, incidence was stable across quarterly intervals (all p>0.10).

HIV seroconversions and incidence

Three participants had acute HIV infection at enrollment. All had negative rapid and Ag/Ab HIV tests at screening and enrollment and initiated PrEP. Two had a positive pooled HIV RNA at enrollment, and infection was subsequently confirmed by individual quantitative RNA testing. The third had a positive qualitative RNA test at enrollment, confirmed by quantitative HIV RNA. One participant had FTC resistance detected as a mixture with wild-type (M184MI) one week after enrollment, which was not present at enrollment, suggesting acquired resistance; this participant was switched to combination antiretroviral therapy (TDF/FTC/darunavir/ritonavir/raltegravir) and has remained virologically suppressed. Viral load was insufficient to perform resistance testing in a second participant (120 copies/mL), and he has remained suppressed on antiretroviral therapy. The third participant had no evidence of HIV resistance on standard or ultrasensitive minor variant testing, although testing was performed 6 weeks after PrEP discontinuation.

Two participants became HIV-infected during follow-up, yielding an HIV incidence of 0.43 infections/100 person-years (95% CI 0.05-1.5). The first infection was detected approximately 19 weeks after enrollment. This participant reported last taking PrEP 37 days prior to seroconversion and had DBS levels <2 doses/week at his seroconversion and all prior visits. The second seroconversion was detected approximately 4 weeks after the 48 week visit, when study drug was no longer dispensed. This participant had DBS levels consistent with daily dosing only at week 4, dropping to <2 doses/week or BLQ thereafter. Neither participant had evidence of TDF/FTC resistance on standard or ultrasensitive minor variant genotyping assays.

Safety

There were 19 serious adverse events reported, 8 of which were psychiatric (suicidal ideation/attempt, bipolar disorder, or anxiety); none were assessed as related to TDF/FTC. There were 23 creatinine elevations occurring in 13 (2.3%) individuals, including 22 grade 1 and one grade 2 events. Only 3 elevations among 3 participants were confirmed on repeat testing, and all resolved within 2-20 weeks without stopping PrEP. Medication was discontinued in 3 participants due to elevated creatinine, however these were not confirmed, and TDF/FTC was restarted in all cases. Two participants had grade 1 creatinine elevations continuing at the end of study. One was attributed to underlying mild renal disease and assessed as unrelated to TDF/FTC. The other was assessed as related, but the participant chose to continue PrEP with his care provider after study completion. Twelve bone fractures were reported during the study. All but one (tooth fracture) was explained by trauma, and none were related to TDF/FTC.

Discussion

Despite low adherence seen in some placebo-controlled PrEP trials,22,23 we observed high adherence among MSM taking PrEP in this open-label demonstration project. Drug was detected in nearly all participants tested, and over three-quarters achieved levels associated with high levels of protection.16,17 This higher adherence rate may be attributable to provision of open-label PrEP in a setting of known efficacy,24,25 as well as growing community acceptance.7 Higher adherence was observed among those reporting greater sexual risk, a finding that was also seen in iPrEx26 and Partners PrEP27 and is expected to increase the impact and cost-effectiveness of PrEP.28,29 PrEP adherence was not diminished among people using alcohol or other recreational drugs.

Despite most achieving protective PrEP levels, lower drug-levels were observed among African-American participants, those with unstable housing, and at the Miami site. These disparities were not explained by other demographic characteristics, depression, or substance use. Racial differences in pharmacokinetics have not been fully evaluated, but small studies have not identified such differences to date.30 Lower medication adherence has been reported among African-Americans including HIV infection,31-34 diabetes,35 hypertension,36 and heart failure.37 Other factors, including mistrust of providers,31 privacy concerns,38 lower health literacy,35 and unmet medical and social-structural needs,39 may explain these disparities, and warrant further exploration in future PrEP programs. Black MSM have high rates of HIV acquisition in the US, highlighting the importance of customizing support for PrEP uptake and adherence for this population. Addressing structural barriers, including lack of insurance and access to supportive healthcare, will also be critical. Several studies are underway evaluating novel PrEP delivery and support approaches in Black MSM, including a care-coordination model in HIV Prevention Trials Network 073 and a mobile-health adherence intervention in Enhancing PrEP in Communities.40

Reasons for lower retention and adherence in the Miami site are unclear. While Miami participants were younger, more likely to be Latino, and had lower education,21 these variables were not independently predictive in adjusted analyses; likewise, while PrEP awareness was lower in Miami, it did not predict retention there. Unmeasured factors including transportation, social support, health literacy, acculturation, and community acceptability of PrEP may help explain this disparity.

Early engagement, measured by clinic attendance and PrEP adherence at week 4, was highly predictive of engagement at the end of the study, highlighting the importance of early adherence assessment and support. Specifically, early monitoring, such as using drug-level testing could be useful in identifying those needing additional support.41 Reductions in the cost and turnaround time of DBS testing would facilitate implementation.

A substantial minority of participants reported one or more PrEP interruptions. Side effects were the most common reason, suggesting the need for additional education and support on the safety and tolerability of TDF/FTC. Creatinine elevations were uncommon, mostly unconfirmed, and managed with regular monitoring. While there were 21 discontinuations due to low self-perceived risk, the majority of these participants reported recent sexual risk. Strategies to improve risk perception, including online risk assessment tools42 and sexual diaries,43 may improve decisions about starting and stopping PrEP.

Despite high STI incidence and reported risk behaviors, we observed very low HIV incidence (0.43%), with only two incident infections. Both participants had low or undetectable TFV-DP in DBS, a pattern seen in the recent PROUD and IPERGAY PrEP trials.4,5 These studies, with similarly high reported risk and STI prevalence and high HIV incidence in the placebo arms (8.9 and 6.8/100 person-years), demonstrated high levels of PrEP efficacy (86%) and low number needed to treat (13 and 18, respectively). The low HIV incidence observed in the Demo Project likely reflects high overall adherence to PrEP and demonstrates that high levels of effectiveness can be achieved outside of controlled studies. Three acute HIV infections were detected by HIV RNA at enrollment. HIV RNA testing at PrEP initiation would help detect early infection and facilitate early initiation of antiretroviral therapy.

We observed high STI positivity rates at baseline and during follow-up, but STI incidence was stable over time. The initial decline of rectal and pharyngeal STIs followed by an increase may reflect clearance of prevalent infections at screening, regression to the mean, cohort and seasonal effects, and/or risk compensation. High STI rates were also observed among MSM in PROUD and IPERGAY.4,5 While current CDC PrEP guidelines recommend STI testing every 6 months,44 we recommend quarterly screening for MSM taking PrEP, including testing at extragenital sites.

This study had several limitations. First, African-American and transgender persons were under-represented in the sample, reflecting under-representation at the participating clinics. This highlights the need for additional strategies to engage these populations, and to deliver PrEP in settings where these individuals feel comfortable and safe receiving care. For example, integration of PrEP into transgender health care, including provision of cross-sex hormone treatments, may increase uptake in that population.45 Second, while we conducted this study in 3 diverse US clinics, these results may not generalize to the broader MSM population in these cities, other parts of the US, or international settings. Finally, while this project sought to assess PrEP use in clinical settings where medication and monitoring were provided free, cost and lack of insurance coverage may present significant barriers to PrEP access and adherence outside of a study, particularly in states with weak safety nets.46 Strategies to increase affordability are critical to ensuring PrEP access to all individuals at risk for HIV. Cost-effectiveness studies of different PrEP delivery models are also needed to inform PrEP implementation.

In conclusion, these results provide support for expanding PrEP implementation in MSM in similar clinical settings, and highlight the urgent need to increase PrEP awareness and engagement and to develop effective adherence support for highly impacted African-American and transgender populations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Funding/Support: This study was funded by the National Institute for Allergies and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) (UM1AI069496); National Institute for Mental Health (R01MH095628); and the Miami Center for AIDS Research (P30AI073961) and the Gladstone Institute of Virology and Immunology-University of California San Francisco Center for AIDS Research (P30AI027763) from the National Institutes of Health. Study drug and support for pharmacokinetic and resistance testing were provided by Gilead, but Gilead played no role in conception, design or conduct of the study, or analysis and interpretation of data.

Role of the Sponsors: NIAID participated as a partner in protocol development, interpretation of data and gave final approval to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

TRIAL REGISTRATION clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT# 01632995

Author Contributions: Drs. Liu and Cohen had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Liu, Cohen, Bacon, Doblecki-Lewis, Kolber, Chege

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Liu, Cohen, Vittinghoff, Doblecki-Lewis, Bacon, Anderson, Chege, Postle, Matheson, Amico, Liegler, Rawlings, Trainor, Blue, Estrada, Coleman, Cardenas, Feaster, Grant, Philip, Elion, Buchbinder, Kolber

Drafting of manuscript: Liu

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Liu, Cohen, Vittinghoff, Doblecki-Lewis, Bacon, Anderson, Chege, Postle, Matheson, Amico, Liegler, Rawlings, Trainor, Blue, Estrada, Coleman, Cardenas, Feaster, Grant, Philip, Elion, Buchbinder, Kolber

Statistical analysis: Vittinghoff

Obtained funding: Liu, Cohen, Buchbinder

Administrative, technical, or material support: Anderson, Postle, Trainor, Blue, Estrada, Coleman, Cardenas

Study supervision: Liu, Cohen, Matheson, Elion, Kolber

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Rawlings is employed by Gilead Sciences. Anderson received study drug and contract work from Gilead Sciences. Philip received research support from Cephelid, Inc., SeraCare Life Sciences, Melinta Therapuetics, Abbott Diagnostics, and Roche Diagnostics.

Disclaimer: The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the City and County of San Francisco; nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government.

Additional Contributions: We thank the study participants in the Demo Project and the following site coordinators, data managers, pharmacists, counselors and clinicians, and collaborators for their invaluable contributions:

From the San Francisco Department of Public Health: Amy Hilley, MPH (Study Coordinator); Aaron W. Hostetler, BA (Research Associate/Counselor); Amanda Jernstrom, BA (Research Associate/Counselor); Zoë Lehman, BA (Research Associate/Counselor); Amelia Herrera, BA (Research Associate/Counselor); Anthony Sayegh, MS, FNP-C (Study Clinician); Sally Grant, RN, FNP-C (Study Clinician); Tamara Ooms, FNP (Study Clinician); Debbie Vy Khanh Nguyen, BA (Research Associate); Crishyashi Thao (Research Assistant); Erin VW Andrew, MPhil (Study Coordinator). From the University of California, San Francisco: Scott Fields, PharmD (Study Pharmacist) and Mohamed Abdel-Mohsen PhD (assistance with HIV resistance testing). From University of Miami Miller School of Medicine: Jose G. Castro MD (Study Clinician); Henry L. Boza, BA (Outreach Supervisor); Gregory Tapia, MPH (Outreach Coordinator); Isabella Rosa-Cunha, MD (Study Clinician); Maria L. Alcaide, MD (Study Clinician); Faith Doyle, FNP (Study Clinician); Khemraj Hirani, PHD (Study Pharmacist). From Whitman Walker Health: Justin Schmandt, MPH (Research Manager); Tina Celenza, PA-C (Study Clinician); Anna Wimpelberg, BA (Research Associate/Counselor) ; Gwendolyn Ledford, BA (Research Associate/Counselor); JJ Locquiao, BA (Research Associate/Counselor); Adwoa Addai, PharmD (Study Pharmacist). Study personnel listed above were supported by study funds. From the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases: Cherlynn Mathias RN, BSN (Program Officer); David Burns, MD, MPH (Chief, NIH Clinical Prevention Research Branch). We would also like to thank Lisa Metsch, PhD (Columbia University) and Sarit Golub, PhD, MPH (Hunter College and the Graduate Center, City University of New York) for their guidance with protocol design and instrument development.

References

- 1.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–2599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):423–434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCormack S, Dunn D. Pragmatic Open-Label Randomised Trial of Preexposure Prophylaxis: The PROUD Study [Abstract 22LB]; Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI); Seattle, WA. February 23-26, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Molina JM, Capitant C, Spire B, et al. On Demand PrEP With Oral TDF-FTC in MSM: Results of the ANRS Ipergay Trial [Abstract 24LB]; Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI); Seattle, WA. February 23-26, 2015; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Accessed May 3, 2015];Diagnoses of HIV Infection in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2013. HIV Surveillance Report. 2015 25 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu A, Cohen S, Follansbee S, et al. Early experiences implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention in San Francisco. PLoS medicine. 2014;11(3):e1001613. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golub SA, Kowalczyk W, Weinberger CL, Parsons JT. Preexposure prophylaxis and predicted condom use among high-risk men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;54(5):548–555. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e19a54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blumenthal J, Haubrich RH. Will risk compensation accompany pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV? The virtual mentor : VM. 2014;16(11):909–915. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2014.16.11.stas1-1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Straten A, Van Damme L, Haberer JE, Bangsberg DR. Unraveling the divergent results of pre-exposure prophylaxis trials for HIV prevention. AIDS. 2012;26(7):F13–19. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283522272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hurt CB, Eron JJ, Jr., Cohen MS. Pre-exposure prophylaxis and antiretroviral resistance: HIV prevention at a cost? Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(12):1265–1270. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siemieniuk RA, Bogoch II. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(18):1767–1768. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1502749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernstein KT, Marcus JL, Nieri G, Philip SS, Klausner JD. Rectal gonorrhea and chlamydia reinfection is associated with increased risk of HIV seroconversion. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(4):537–543. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c3ef29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu M, Safren SA, Skolnik PR, et al. Optimal recall period and response task for self-reported HIV medication adherence. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(1):86–94. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9261-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amico KR, Marcus JL, McMahan V, et al. Study product adherence measurement in the iPrEx placebo-controlled trial: concordance with drug detection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66(5):530–537. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, et al. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. The Lancet infectious diseases. 2014;14(9):820–829. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70847-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castillo-Mancilla JR, Zheng JH, J.E. R, et al. Tenofovir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir diphosphate in dried blood spots for determining recent and cumulative drug exposure. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013;29(2):384–390. doi: 10.1089/aid.2012.0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, Vanderwarker R, et al. Polysubstance use and HIV/STD risk behavior among Massachusetts men who have sex with men accessing Department of Public Health mobile van services: implications for intervention development. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22(9):745–751. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pilcher CD, Fiscus SA, Nguyen TQ, et al. Detection of acute infections during HIV testing in North Carolina. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(18):1873–1883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liegler T, Abdel-Mohsen M, Bentley LG, et al. HIV-1 drug resistance in the iPrEx preexposure prophylaxis trial. J Infect Dis. 2014;210(8):1217–1227. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen SE, Vittinghoff E, Bacon O, et al. High Interest in Preexposure Prophylaxis Among Men Who Have Sex With Men at Risk for HIV Infection: Baseline Data From the US PrEP Demonstration Project. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68(4):439–448. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):411–422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, et al. Tenofovir-based preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(6):509–518. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amico KR, Stirratt MJ. Adherence to preexposure prophylaxis: current, emerging, and anticipated bases of evidence. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(Suppl 1):S55–60. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amico KR. Adherence to preexposure chemoprophylaxis: the behavioral bridge from efficacy to effectiveness. Current opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2012;7(6):542–548. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e3283582d4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu A, Glidden DV, Anderson PL, et al. Patterns and correlates of PrEP drug detection among MSM and transgender women in the Global iPrEx Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;67(5):528–537. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donnell D, Baeten JM, Bumpus NN, et al. HIV protective efficacy and correlates of tenofovir blood concentrations in a clinical trial of PrEP for HIV prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66(3):340–348. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juusola JL, Brandeau ML, Owens DK, Bendavid E. The cost-effectiveness of preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in the United States in men who have sex with men. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(8):541–550. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-156-8-201204170-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kessler J, Myers JE, Nucifora KA, et al. Evaluating the impact of prioritization of antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis in New York City. AIDS. 2014 doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castillo-Mancilla JR, Seifert S, Zheng J, et al. Population Pharmacokinetics of Tenofovir-diphosphate in Red Blood Cells in HIV-negative and HIV-infected Adults. Reviews in Antiviral Therapy and Infectious Diseases. 2014;4:24–25. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dale SK, Bogart LM, Wagner GJ, Galvan FH, Klein DJ. Medical mistrust is related to lower longitudinal medication adherence among African-American males with HIV. J Health Psychol. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1359105314551950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thames AD, Moizel J, Panos SE, et al. Differential predictors of medication adherence in HIV: findings from a sample of African American and Caucasian HIV-positive drug-using adults. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26(10):621–630. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blackstock OJ, Addison DN, Brennan JS, Alao OA. Trust in primary care providers and antiretroviral adherence in an urban HIV clinic. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved. 2012;23(1):88–98. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simoni JM, Huh D, Wilson IB, et al. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in ART adherence in the United States: findings from the MACH14 study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;15(60):466–472. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825db0bd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Osborn CY, Cavanaugh K, Wallston KA, et al. Health literacy explains racial disparities in diabetes medication adherence. J Health Commun. 2011;16(3):268–278. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.604388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lauffenburger JC, Robinson JG, Oramasionwu C, Fang G. Racial/Ethnic and gender gaps in the use of and adherence to evidence-based preventive therapies among elderly Medicare Part D beneficiaries after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2014;129(7):754–763. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dickson VV, Knafl GJ, Wald J, Riegel B. Racial differences in clinical treatment and self-care behaviors of adults with chronic heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(4) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rose LE, Kim MT, Dennison CR, Hill MN. The contexts of adherence for African Americans with high blood pressure. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(3):587–594. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shi L, Stevens GD. Vulnerability and unmet health care needs. The influence of multiple risk factors. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(2):148–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40136.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu A. Developing and Implementing a Mobile Health (mHealth) Adherence Support System for HIV-Uninfected Men who have Sex with Men (MSM) Taking Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP): The iText Study; 8th International Conference on HIV Treatment and Prevention Adherence; [AB 229]; Miami, FL. June 2-4, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Molina JM, Pintado C, Gatey C, et al. Challenges and opportunities for oral pre-exposure prophylaxis in the prevention of HIV infection: where are we in Europe? BMC medicine. 2013;11:186. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scott H, Vittinghoff E, Irvin R, et al. Sex Pro: A Personalized HIV Risk Assessment Tool for Men Who Have Sex With Men [Abstract 1017]; Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI); Seattle, WA. February 23-26, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vallabhaneni S, Hartogensis W, Sheon N, et al. Harnessing mobile health technology in HIV research: a pilot study utilizing a smartphone-based daily-diary app to collect event-level sexual activity data [Abstract TUPE358]; 7th IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention 2013; Kuala Lampur, Malaysia. [Google Scholar]

- 44.US Public Health Service [Accessed May 3 2015];Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States—2014: a clinical practice guideline. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sevelius J. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and trans people: What do we know now; what else do we need to understand in order to add this promising intervention into our prevention toolkit?; 2015 National Transgender Health Summit; Oakland, California. April 17-18, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cohen SE, Vittinghoff E, Doblecki-Lewis S, et al. Response to “Race and the public health impact potential of PrEP in the United States”. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.