Abstract

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified numerous genetic variants associated with complex diseases but mechanistic insights are impeded by the lack of understanding of how specific risk variants functionally contribute to the underlying pathogenesis1. It has been proposed that cis-acting effects of non-coding risk variants on gene expression are a major factor for phenotypic variation of complex traits and disease susceptibility. Recent genome-scale chromatin mapping studies have highlighted the enrichment of GWAS variants in regulatory DNA elements of disease-relevant cell types2–6. Furthermore, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-specific changes in transcription factor (TF) binding are correlated with heritable alterations in chromatin state and considered a major mediator of sequence-dependent regulation of gene expression7–10. Here we describe a novel strategy to functionally dissect the cis-acting effect of genetic risk variants in regulatory elements on gene expression by combining genome-wide epigenetic information with clustered regularly-interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/Cas9 genome editing in human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs). By generating a genetically precisely controlled experimental system we identify a common Parkinson’s disease (PD)-associated risk variant in a non-coding distal enhancer element that regulates the expression of alpha-synuclein (SNCA), a key gene implicated in the pathogenesis of PD. Our data suggest that the transcriptional deregulation of SNCA is associated with sequence-dependent binding of the brain-specific TFs EMX2 and NKX6-1. This work establishes an experimental paradigm to functionally connect genetic variation with disease relevant phenotypes.

PD is the second most common chronic progressive neurodegenerative disorder. The discovery of genes linked to rare Mendelian forms of PD has provided vital clues to the molecular and cellular pathogenesis of the disease11. However, over 90% of PD cases do not show Mendelian inheritance patterns suggesting that sporadic, late onset PD results from a complex interaction between genetic and environmental risk factors. While coding mutations and genomic multiplications of the SNCA gene cause familiar PD, GWAS have identified SNCA as one of the strongest risk loci associated with the sporadic form of the disease, suggesting a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of PD1,12. Genomic duplications of SNCA indicate that an increase by 50% in SNCA expression is sufficient to develop an autosomal-dominant form of the disease, suggesting that PD-associated risk variants might lead to a subtle increase in SNCA expression2–6,13–15. To analyze such slight changes in gene expression despite considerable technical and biological heterogeneity of in vitro hESC culture and differentiation systems, we conceived a novel experimental approach which allows to reliably quantify the consequence of targeted genetic modifications on transcription by analyzing the cis-acting effects on allele-specific expression. Figure 1a and b illustrate how the heterozygous deletion or exchange of a candidate regulatory element through cis-regulatory effects on expression is predicted to modulate allele-specific gene expression when measured as the ratio between the modified and the non-targeted allele.

Fig. 1. Strategy to analysis cis-regulatory effects of genetic variants on allele-specific expression of SNCA.

(a) Schematic illustration of the experimental strategy to study the function of PD-associated regulatory elements in hPSC-derived neurons by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated heterozygous deletion (ΔE) or exchange/insertion (ExE) of risk-associated enhancer sequences. (b) Expected effect on relative allele-specific gene expression in hPSC-derived neurons resulting from enhancer modifications described in (a). (c) Allele-specific SNCA expression analysis of allele-biased samples with indicated allele ratios. Allele-biased samples were generated by mixing hIPSC-derived neurons homozygous for either the A-(IPS-A) or G-allele (IPS-G) at rs356165. The relative expression of each allele was normalized to the total expression of SNCA (black bars) in the respective sample. (d) qRT-PCR analysis for relative expression of the A-(FAM)-allele (red bars) and the G-(VIC)-allele (blue bars) in allele-biased samples described in (c, calculated as proportion) compared with expected relative proportions (light and dark grey bars). (e) Analysis of total SNCA expression at different time points during in vitro differentiation of hESCs-derived neurons (BGO1 and WIBR3). (f) Allele-specific SNCA expression of hESC-derived neurons described in (e) normalized to differentiation day 10 cultures. Shown are mean values ± s.d. (n = 3). nd, not detected. Source data are provided as Source Data for Extended Data Figure 1.

To analyze precisely the expression of two individual alleles in a single multiplex reaction, we adapted TaqMan® SNP genotyping assays to quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR; Extended Data Fig. 1a). A common SNP (rs356165 A/G referred to as SNCA “reporter SNP”) was identified in the 3′-UTR of SNCA in two hESCs lines and a common primer pair and allele-specific TaqMan® probes conjugated with different fluorophores were used to distinguish between the two alleles (FAM to detect the A-allele and VIC to detect the G-allele). To validate this approach, we simulated allele-biased samples over a wide range of SNCA expression ratios by mixing c-DNAs from two types of hIPSC-derived neurons7–10,16 that are homozygous for either the A- or the G-allele at the reporter SNP. Multiplex allele-specific qRT-PCR analysis robustly quantified the expression of each individual allele in the mixed samples (Fig 1c, Extended Data Fig. 1b) with the relative allele-specific expression of the two alleles closely correlating with the expected ratio (Fig. 1d). Comparing neurons derived from isogenic cultures in parallel at different time points during terminal differentiation (Extended Data Fig. 2) revealed considerable differences in total SNCA expression (Fig. 1e). In contrast, allele-specific expression remained constant across all conditions (Fig. 1f). These data indicate that allele-specific TaqMan® qRT-PCR analysis robustly allows detection of small effects on allele-specific expression independent of cellular heterogeneity due to in vitro differentiation and maturation.

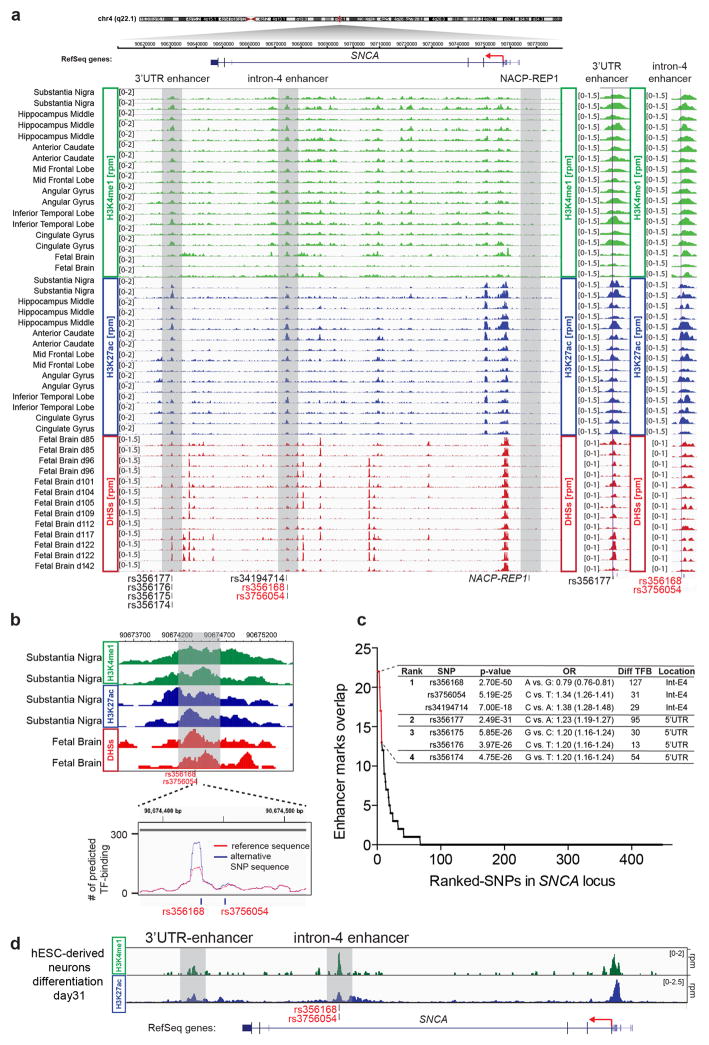

A recent analysis in adult brain identified significant enrichment of PD-associated SNPs within distal enhancers11,17, consistent with the notion that GWAS variants in regulatory elements can be used to prioritize functional disease-relevant risk alleles18,19. To identify candidate risk variants in enhancers, we intersected PD-associated SNPs in the SNCA locus (463 SNPs, p < 5 ×10−8 provided by PDgene database)12 with publicly available epigenetic data (NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium; http://www.roadmapepigenomics.org)20. Ranking of all PD-associated SNPs in the SNCA locus based on cumulative overlap with enhancer-associated marks3,21,22 such as H3K4me1, H3K27ac and DNase I hypersensitive sites (DHSs) revealed that the top 7 risk variants were localized to two distal enhancer elements (intron-4 enhancer and 3′UTR enhancer, Fig. 2a, Extended Data Fig. 3a–c and Supplementary Table 1) with both displaying an active epigenetic signature in the substantia nigra and in hESC-derived neurons (Extended Data Fig. 3b,d). Because SNP-specific changes are thought to modify enhancer activity by altering TF binding7–10, we analyzed predicted TF binding by scanning for known binding sequence motifs comparing both alternative genotypes for each PD-associated SNP. This analysis indicated that the risk variant rs356168 in intron-4-enhancer is a TF binding hotspot with the highest number of predicted genotype-dependent differential binding of all PD-associated SNPs in the SNCA locus (Extended Data Fig. 3b,c; Supplementary Table 1).

Fig. 2. Identification of a functional cis-acting PD-associated SNP in an intronic enhancer element of SNCA.

(a) Heatmap of H3K4me1 and H3K27ac ChIP-Seq and DHSs-enrichment tracks for several CNS regions in the SNCA locus (for details see Extended Data Fig. 3a; Data provided by NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium; http://www.roadmapepigenomics.org). Shown are the locations of NACP-Rep1 and PD-associated SNPs overlapping with two proximal enhancer elements (3′UTR-enhancer and intron-4-enhancer) highlighted by light gray boxes. (b) Schematic illustration of the CRISPR/Cas9-mediated strategy to delete and subsequently insert intron-4 enhancer elements with indicated PD-associated risk SNP genotype at rs356168 and rs3756054. Targeted clones carrying inserted risk alleles in cis with the A-(FAM)-reporter SNP (confirmed by genomic sequencing-based phase-reconstruction) were used for subsequent analysis described in (c,d). (c, d) Relative allele-specific SNCA expression in (c) neural precursors and (d) mixed neuronal cultures (differentiation day 25) derived from targeted cell lines with indicated intron-4 enhancer alleles compared to hESCs carrying homozygous enhancer deletions (ΔE4/ΔE4) (expression was normalized relative to ΔE/ΔE cell lines). Data are presented as dot plot; each dot represents mean of 3 technical replicates. Allele-specific expression for each clone was analyzed in 3 independent biological replicate experiments and combined according to genotypes. Black lines indicate mean expression for each genotype; n indicates number of independently targeted clones per genotype, † indicates an additional sub-clone derived from one of the two targeted clones for this genotype. Statistical differences between genotypes were calculated using one-way ANOVA (alpha = 0.05) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test based on allele-specific expression of all biological replicates. *P < 0.001; ** P<0.0001; source data and detailed statistical analysis are provided as Source Data for Extended Data Figure 2.

To analyze the function of the intron-4-enhancer element, we deleted 500 bps of the epigenetically marked enhancer region containing the PD-associated risk SNPs rs356168 and rs3756054 by CRISPR/Cas9 mediated genome editing (Fig. 2b, Extended Data Fig. 3b, 4a). We subsequently reinserted an allelic series of intron-4 enhancer elements harboring all possible genotype combinations for rs356168 and rs3756054 into the enhancer deleted cells (Fig. 2b, Extended Data Fig. 4a) to dissect sequence-specific effects of each risk variant. Southern blot analysis and genomic sequencing confirmed correct integration of the targeted enhancer element in cis with the A-(FAM)-allele reporter SNP (Fig. 2b; Extended Data Fig. 4). To analyze the effect of each enhancer genotype on SNCA expression, we differentiated between 2 and 4 individual clones targeted for each enhancer element into neural precursors or mixed neuronal cultures. Initial expression analysis for total SNCA and markers for neuronal and astrocytic differentiation showed no consistent differences between the genotypes (Extended Data Fig. 5 a–c). In contrast, allele-specific qRT-PCR analysis revealed that neural precursors and neurons carrying the G-allele at rs356168 showed a highly significant increase in expression of the A-(FAM)-reporter SNP compared with cells carrying the A-allele at rs356168 and the homozygous enhancer deleted controls (Fig 2c,d; Extended Data Fig 5d–g). Because the inserted enhancer elements are in cis with the A-(FAM) reporter SNP (Fig. 2b) we conclude that only insertion of enhancer sequences carrying the G-allele at rs356168 results in increased expression of SNCA whereas the A-allele at this SNP has no effect compared with enhancer deleted controls. This effect was independent of the adjacent risk variant rs3756054, which has almost no effect on allele-specific SNCA expression (Fig. 2c,d; Extended Data Fig. 5d–g). Genotyping of the parental cell line revealed that WIBR3 is heterozygous at SNP rs356168 with the A-allele in cis with the A-(FAM)-reporter SNP and the G-allele in cis with the G-(VIC) reporter SNP (Extended Data Fig. 5h). The homozygous deletion of the intron-4-enhancer resulted in decreased allele-specific expression of the G-(VIC)-allele (Extended Data Fig. 5i) consistent with the observation that only the G-allele at rs356168 significantly modifies the expression of the cis-regulated allele. Our results suggest that the intron-4-enhancer element regulates the transcription of SNCA in human neural precursor cells and neurons and that the common SNP at rs356168 represents a functional risk variant with the G-allele causing increased expression. This is consistent with the GWAS data, which identify the non-active A-allele at rs356168 as a protective allele with an odds ratio (OR) of 0.79 (0.76–0.81)12. In contrast, the PD-associated SNP rs3756054 has no effect on SNCA expression suggesting that this variant is in linkage disequilibrium (LD) with the risk modifying SNP.

To further support a functional effect of rs356168 we performed an expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) analysis of total SNCA mRNA levels measured by qRT-PCR in 127 postmortem frontal cortex samples (86 PD, 41 control). A significant increase in total SNCA levels (p=0.031; linear regression analysis) was observed in carriers of the rs356168 risk allele (Extended Data Fig. 6b). In comparison only a modest and not significant increase (p=0.33) in expression was observed for rs356229 (as proxy for top reported GWAS SNP12 rs356182; R2=0.62), indicating that rs356168 more precisely predicts SNCA expression levels.

To assesse the extent to which rs356168 could explain the associations observed in the SNCA region in PD GWAS12, we completed a baseline and conditional analysis in 5 publicly available PD GWAS cohorts totaling 6014 cases and 9119 controls. The effect of the top reported GWAS SNP rs356182 was reduced 28% from an OR of 1.32 to 1.23 and the statistical significance was attenuated from a genome wide significant p-value of 1.1 × 10−21 to 3.0 × 10−6 (Extended Data Fig. 6a). As expected, the independent 5′ region SNP rs7681154 which was revealed in the initial GWAS conditional analysis12 continued to show a significant independent effect when conditioning on rs356168.

Although this type of analysis cannot identify by itself functional risk variants, the results are consistent with the hypothesis that multiple functional variants with small size effects contribute to the overall association and heritability of the SNCA locus with sporadic PD (common disease-common variant hypothesis). The in vitro observed changes in allele-specific expression translate roughly to an increase of total SNCA expression of 1.06 times in neurons and 1.18 times in neural precursors. Given that a 1.5-fold increase in SNCA expression is sufficient to cause a familial autosomal-dominant form of PD, our data support the notion that a modest life-long increase of SNCA expression may represent the molecular basis of increased PD risk of G-allele carriers.

Sequence-specific changes in chromatin state associated with differential enhancer activities, have been proposed as a mechanism for SNP-dependent cis-regulatory effects on gene expression7–10. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) followed by qRT-PCR for H3K4me1 and H3K27ac and ChIP-seq analysis for H3K27ac in neurons carrying all distinct genotypes indicated, that all intron-4-enhancer elements display a chromatin signature for an active enhancer (Extended Data Fig. 7). Normalization of intron-4-enhancer ChIP-seq reads relative to the 3′-UTR enhancer of SNCA suggest a slight trend of increased H3K27ac read density in neurons carrying the G-allele at rs356168 (Extended Data Fig. 7e) consistent with sequence-dependent changes of chromatin state and enhancer activity. However, considering the small SNP-dependent effect on transcription, it is difficult to distinguish between sequence-specific changes and technical variations resulting from in vitro differentiation associated variability.

Differential TF binding is considered a major mediator of sequence-specific effects of distal enhancers on gene regulation7–10. We compiled a list of all TFs predicted to show SNP-specific binding at rs356168 by scanning the sequences of both alternative alleles for known binding motifs (Supplementary Table 2). We selected 10 candidate TFs (see material and methods) and performed ChIP-qRT-PCR to identify candidates that specifically bind to the intron-4 enhancer element in in vitro differentiated neurons. This analysis identified binding of the CNS-expressed TFs NKX6-1 and EMX2 (Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 8a). Immunostaining confirmed the expression of EMX2 and NKX6-1 in hESC-derived neurons and to a lower extent in interspersed astrocytes (Extended Data Fig 9f–j). Single molecule mRNA flouresence in situ hybridization (FISH) showed that more than 40% of the cultured cells were positive for one of the two TFs while only a smaller fraction (around 20%) expressed both factors simultaneously (Extended Data Fig 9a–e). Importantly, electrophoretic mobility shift assay analysis (EMSA) revealed a clear SNP-dependent binding of EMX2 and NKX6-1 with preference for the protective lower SNCA expressing A-allele at rs356168 (Fig. 3b–e and Extended Data Fig. 8b,c). These results suggest a model in which the sequence-specific binding of these TFs at a distal enhancer element represses enhancer activity and thus modulate SNCA expression (Fig. 4). These data further suggest that the same enhancer elements may be regulated in distinct neuronal population by different TFs since it seems not crucial that both proteins are expressed in the same cells. Indeed, the overexpression of EMX2 and NKX6-1 in terminally differentiated neurons, using a highly controlled doxycycline inducible system, resulted in significant down-regulation of SNCA expression (Fig. 3d) further supporting this hypothesis. Our results are consistent with mouse models demonstrating a similar mechanism as repressors of enhancer function23–25.

Fig. 3. Sequence-specific effect of PD-associated risk variants on binding of CNS expressed TFs EMX1 and NKX6-1 at SNCA intron-4 enhancer.

(a) ChIP-qRT-PCR analysis for binding of indicated TFs at the intron-4-enhancer element compared with a negative control region in the SNCA locus (calculated as fold enrichment compared with IgG Isotype control). Statistical significance was determined using t-test followed by the Holm-Šídák method to correct for multiple comparisons (alpha = 0.05). *P < 0.0001. (b, c) EMSA analysis for SNP-genotype-specific binding of (b) EMX2 or (c) NKX6-1 to oligonucleotides (oligo) harboring the indicated genotype at rs356168 (A/G-allele). Binding was analyzed in nuclear extracts (NEs) from wild-type (293) or EMX1 (b, EMX) or NKX6-1 (c, NKX) overexpressing HEK293 cells. Red arrows point to oligonucleotide-specific binding which is lost in the presence of unlabeled competitor oligonucleotides (indicated genotype at rs356168; 200X). (d) SNCA expression analysis following doxycycline (DOX)-induced overexpression of EGFP, EMX2 or NKX6-1 for 3 days in terminally differentiated neurons (differentiation day 21). Shown are mean values ± s.d. (n = 10) of relative SNCA expression in DOX-induced cells compared with the corresponding untreated controls (NoDOX). Results are representative of two different experiments. Statistical significance was calculated using t-test followed by the Holm-Šídák method to correct for multiple comparisons (alpha = 0.05). *P < 0.0001. Source data are provided as Source Data for Extended Data Figure 3.

Fig. 4. Proposed model describing the correlation between SNP-dependent TF binding, SNCA expression and PD risk.

Carriers of the A-allele at rs356168 (PD protective allele) show efficient binding of the brain-specific TFs EMX2 and NKX6-1 at the distal intron-4-enhancer, which results in a suppressed distal enhancer and consequently lower expression of SNCA associated with a reduced risk to develop PD. In contrast, carriers of the G-allele at rs356168 (PD-risk allele) show reduced TF binding, which results in an active distal enhancer leading to increased expression of SNCA and increased risk to develop PD.

Several GWAS identified a polymorphic microsatellite repeat region 10 kb upstream of the transcription start site (Fig. 2a) associated with PD risk. These studies suggest that individuals homozygous for a shorter repeat region (Rep1-257 or Rep1-259) have a significant lower risk of developing PD than individuals carrying the longer forms (Rep1-261 or Rep1-263)26. Functional studies suggested an enhancer-like function based on the cis-regulatory correlation between the NACP-Rep1 repeat length and SNCA expression27,28. To test whether NACP-Rep1 length influences SNCA expression in human neurons, we deleted the entire repeat region and subsequently inserted representative alleles for each of the 4 reported repeat length alleles26 (Extended Data Fig. 10a). Genomic sequencing, Southern blot analysis and fragment length analysis confirmed correct integration of the respective alleles (Extended Data Fig. 10b–d). Multiple sub-clones of each of the NACP-Rep1 alleles were differentiated into neurons and analyzed for allele-specific SNCA expression. Though individual clones varied considerably, no repeat length dependent effect of NACP-Rep1 on SNCA expression was detected in two hESC lines (Extended Data Fig. 10e,f). Moreover, the deletion of the entire repeat region thought to have the strongest effect an SNCA expression27 did not significantly alter the allele-specific expression compared with the parental hESC lines or any of the other NACP-Rep1 alleles. This result conflicts with the microsatellite repeat region exerting a cis-regulatory effect on of SNCA expression. It is possible that difficulties in controlling the experimental variables in neuroblastoma cells28 or transgenic mice27 affected the validity of the previous conclusions. Since in vitro differentiated cells allow only for the analysis of early events, we cannot completely exclude an effect of the NACP-Rep1 element at later time points or in combination with additional factors such as environmental stress.

The generation of patient-derived hiPSCs, which carry all pathogenic genetic alterations, is attractive for the study of diseases. However, significant biological heterogeneity due to differences in genetic background, variation in hiPSC isolation and in vitro differentiation present a serious limitation for identifying a disease-relevant phenotype in the culture dish29. This is particularly relevant for sporadic diseases likely displaying only subtle in vitro phenotypes. Here we describe an alternative experimental approach to identify functional risk variants based on three recent innovations in genetics and molecular biology: (i) the prioritization of GWAS-identified risk variants in regulatory elements such as distal enhancers annotated based on genome-scale epigenetic data; (ii) the generation of genetically-controlled isogenic pluripotent cell lines in which specific disease-associated genetic variants are the sole modified experimental variable using efficient gene editing technologies such as the CRISPR/Cas9 system30; and (iii) the analysis of cis-acting effects of candidate variants on allele-specific gene expression through deletion or exchange of disease-associated regulatory elements. This approach eliminates the effect of system inherent variability such as in vitro differentiation and results in an internally controlled experimental system, which allows robust and reproducible identification of cis-acting sequence-specific effects on gene regulation. Importantly, the experimental paradigm established here is not only relevant for PD, but is generally applicable for mechanistic study of the molecular consequences of risk alleles associated with other diseases.

METHODS

HESC and hiPSC culture

HESC and hiPSC culture conditions have been described previously30. HiPSCs16 and hESC lines WIBR3 (Whitehead Institute Center for Human Stem Cell Research, Cambridge, MA)31 and BGO1 (NIH Code: BG01; BresaGen, Inc., Athens, GA) were maintained on mitomycin C-inactivated mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) feeder layers in hESC medium [DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone), 5% KnockOut Serum Replacement (Invitrogen), 1 mM glutamine (Invitrogen), 1% nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen), 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma) and 4 ng/ml FGF2 (R&D systems)]. Cultures were passaged every 5 to 7 days either manually or enzymatically with collagenase type IV (Invitrogen; 1.5 mg/ml). All experiments in this study were performed in a sub-clone of WIBR3 and BGO1 with a targeted in-frame insertion of EGFP into the Nurr1 locus (data not shown), which should not influence the here reported results and will be described in detail in a separate publication. The identity of all parental hESC lines was confirmed by DNA-fingerprinting and all cell lines were regularly tested to exclude mycoplasma contaminations using a PCR based assay.

NPC culture and terminal differentiation

Differentiation into neural precursor cells (NPCs) and terminal differentiated neurons was performed according to previously described protocols with slight modifications16,30,32. All cell lines for each individual experiments were differentiated in parallel to further reduce experimental variability. Briefly, hESC colonies were harvested using 1.5 mg/ml collagenase type IV (Invitrogen), separated from the MEF feeder cells by gravity, gently triturated and cultured for 8 days in non-adherent suspension culture dishes (Corning) in EB medium [DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 20% KnockOut™ Serum Replacement (Invitrogen), 0.5 mM glutamine (Invitrogen), 1% nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen), 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma)] supplemented with 50 ng/mL human recombinant Noggin (Peprotech) and 1000 nM dorsomorphin (Stemgent). Subsequently human EBs were plated onto poly-L-ornithine (15 μg/ml, Sigma), laminin (1 μg/ml Sigma), fibronectin (2 μg/ml Sigma)-coated tissue culture dishes in N2 medium33 supplemented with 50 ng/mL human recombinant Noggin (Peprotech), 1000 nM dorsomorphin (Stemgent) and FGF2 (20 ng/ml, R&D systems). After 8 days, neural rosette-bearing EBs were cut out by microdissection, dissociated using 0.05% trypsin/EDTA solution (Invitrogen) and subsequently expanded on poly-L-ornithine, laminin and fibronectin coated cell culture dishes a density of 5 × 105 cells/cm2 in N2 medium supplemented with FGF2 (20 ng/ml, R&D systems). Proliferating NPCs were passaged 2 to 4 times before induction of terminal differentiation into neurons by growth factor withdrawal in N2 medium supplemented with ascorbic acid (Sigma). Differentiated neurons were used for analysis between day 25 and 31 day after differentiation. After 28 days of terminal differentiation, the cultures consist primarily of excitatory glutamatergic neurons and astrocytes with few other detectable cell types such as dopaminergic neurons (Extended Data Fig. 2). In addition neural precursor cells were also included in in gene expression analysis due to the robust expression of SNCA at this developmental stage.

CRISPR/Cas9 gRNA and donor vector design

To generate grand expression vectors, which express a fluorescent marker protein for FACS sorting in addition to Cas9 and the grand, we modified the pX330 grand expression vector34 by insertion of either a CMV-EGFP-pA (pX330-EGFP), CMV-YFP-pA (pX330-YFP), CMV-mCherry-pA (pX330-mCherry) or CMV-BFP-pA (pX330-BFP) into the Not1 and Sbf1 restriction sites. Annealed oligonucleotides for each targeting site (Supplementary Table 3a) were ligated in to the BbsI restriction site as described previously35. Donor plasmids were generated by inserting a genomic PCR-amplified fragment (Supplementary Table 3b, 1834 bp for intron-4-enhancer and 2333 bp for NACP-Rep1) into the pCR2.1-TOPO-TA cloning vector (Life technologies) according to the provider’s instructions. Donor plasmids for intron-4-enhancer targeting to insert the four genotypes (Supplementary Table 3b) were generated by replacing the wild-type sequence between the Mfe1 and Sty1 restriction sites with a synthetized gene fragment (gBlock, Integrated DNA technologies, Iowa). Donor plasmids for NACP-Rep1 targeting to insert the four NACP-Rep1 genotypes (Supplementary Table 3b) were generated by replacing the wild-type sequence between the Mfe1 and Stu1 restriction sites with corresponding NACP-Rep1 fragments selected from a sub-cloned haplotypes derived from a collection of human cell lines.

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing of hESCs

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing of hESCs was performed as described previously30,36. HESCs or the respective targeted sub-clones were cultured in Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK)-inhibitor (10 μM, Stemgent; Y-27632) 24 hours prior to electroporation. Cells were harvested using 0.05% trypsin/EDTA solution (Invitrogen) and resuspended in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). For genomic deletions, 1 × 107 cells were electroporated with 22.5 μg of each grand expression vector (Extended data Table 2). For insertion of NACP-Rep1 or intron-4-enhacer haplotypes, 1 × 107 cells were electroporated with 15 μg grand expression vector and 30 μg of the respective donor vector (Supplementary Table 3a,b). Cells were maintained on MEF feeder layers for 72 hours in the presence of ROCK inhibitor followed by FACS sorting (FACS-Aria; BD-Biosciences) of a single-cell suspension for cells expressing the respective fluorescent marker proteins (Supplementary Table 3a) and subsequently plated at a low density in hESC medium supplemented with ROCK inhibitor for the first 24 hours. Individual colonies were picked and expanded 10 to 14 days after electroporation. Correctly targeted clones were subsequently identified by genomic sequencing with primers outside of the targeting region (Supplementary Table 3c), Southern blot analysis and for the NACP-Rep1 targeting with fragment length analysis. All targeted and maintained cell lines used for subsequent experiments are summarized in Supplementary Table 3g.

Southern blotting

Genomic DNA was separated on a 0.7% agarose gel after restriction digests with the appropriate enzymes, transferred to a nylon membrane (Amersham) and hybridized with 32P random primer (Agilent)-labeled probes.

Fragment length analysis

Fragment length analysis for NACP-Rep1 was performed as described previously26 using the Type-it Microsatellite PCR Kit (Qiagen) according to providers instruction using a NACP-Rep1-forward and 5′-FAM (Flourescein) labeled NACP-Rep-1 reverse Primer (Supplementary Table 3c). Fragment length along with an appropriate standard was determined using a 3730×l DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems) and analyzed with Peak Scanner software 2 (Applied Biosystems).

Genomic sequencing-based phase-reconstruction

Genomic DNA from wild-type WIBR3 and targeted clones was amplified using Platinum®Taq DNA polymerase (Life Technologies) and primer pairs indicated in Supplementary Table 3d. PCR products were sub-cloned using TOPO® XL-PCR cloning kit (Life Technologies) according to providers’ instructions and between 6 and 10 individual clones were submitted for sequencing. The phase between intron-4-enhancer SNPs (rs356168 and rs3756045) and the reporter SNP (rs356165) was manually determined based on the genotype of linked heterozygous SNPs in the respective fragments (Supplementary Table 3d).

Allele-specific quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) including on-column DNase digest to remove genomic DNA. Reverse transcription was performed on 0.5–1μg of total RNA using oligo dT priming and SuperScript® III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix (Life technologies) at 50°C according to providers instructions. The SNP genotyping TaqMan® assays for allele-specific SNCA probes and TaqMan® gene expression analysis assay targeting the 3′UTR of SNCA and GAPDH were custom designed or provided by the manufacturer (Supplementary Table 3c; Applied Biosystems). All samples were performed in technical triplicates in a 384-well plate format on a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) using Taqman® Universal Master MIX II with UNG (Applied Biosystems) according to manufacturers’ instructions. Sequential dilution samples from neurons derived from hiPSCs that are homozygous for either the A-allele (IPSC-PDA derived from AG20443) or G-allele (IPSC-PDB derived from AG20442) at the reporter SNP (rs357165) were included to determine primer efficiency for each experiment separately. Relative quantification of allele-specific expression of SNCA was calculated using the Pfaffl method37 that incorporates primer efficiencies, using total SNCA expression (3′UTR-SNCA TaqMan® assay) as reference gene and dependent on experimental design the average of either wild-type or enhancer deleted cells (WIBR3 ΔE4/ΔE4) as calibrator. Allele-specific SNCA expression proportions were calculated relative to calibrator samples which were set to 0.5. All statistical analyses were calculated using GraphPad Prism 6 for Mac. Significant differences between genotypes were calculated using one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test based on allele-specific expression from 3 biological replicates (representing the mean of 3 technical replicates) for each of the individual subclones as indicated in the figure legends. For statistical analysis all biological replicates of individual clones were combined according to genotypes. Equal variances between genotypes were tested using Brown-Forsythe test. In addition the observed effects were confirmed using the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. The allele-specific expression data and the detailed statistical analysis corresponding to data displayed in Fig. 2c,d and Extended Data Fig. 5d–g are provided as Source Data for Figure 2 and Source Data for Extended Data Figure 5.

Reverse transcription of total RNA and real-time PCR

RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) including on-column DNase digest to remove genomic DNA. Reverse transcription was performed on 0.5–1μg of total RNA using oligo dT priming and SuperScript® III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix (Life technologies) at 50°C according to providers instructions. All PCR reactions were performed in a 384-well plate format on a 7A900HT Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) using either Taqman® Universal Master MIX II with UNG (Applied Biosystems) or Platinum SYBR green pPCR SuperMIX-UDG with ROX (Invitrogen) according to manufacturers’ instructions using primer as summarized in Supplementary Table 3c. Relative quantification of gene expression was calculated using the 2–[delta][delta]Ct method using GAPDH (Taqman®) or 60S acidic ribosomal protein P0 (RPLP0 for SYBR green) as reference and untreated control samples (as specified in the Figure legends) as calibrator.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP-qRT-PCR and ChIP-seq)

ChIP-qRT-PCR and Chip-seq was performed as described previously38. 107 cells per ChIP assay were cross-linked for 10 minutes at room temperature by the addition of one-tenth of the volume of 11% formaldehyde solution (11% formaldehyde, 50mM HEPES pH 7.3,100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 0.5 mM EGTA pH 8.0) to the growth media followed by quenching with 100 mM glycine. Cells were washed twice with PBS, then the supernatant was aspirated and the cell pellet was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. 20 ul of Dynal magnetic beads (Sigma) were blocked with 0.5% BSA (w/v) in PBS. Magnetic beads were bound with 2 ug of antibody indicated in Supplementary Table 3e. Cross-linked cells were lysed with lysis buffer 1 (50 mM HEPES pH 7.3, 140 mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.5% NP-40, and 0.25% Triton X-100) and resuspended and sonicated in sonication buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% Na-deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS). Cells were sonicated at 4°C with a Bioruptor (Diagenode) at high power for 25 cycles for 30s with 30s between cycles. Sonicated lysates were cleared and incubated overnight at 4°C with magnetic beads bound with antibody (Supplementary Table 3e) to enrich for DNA fragments bound by the indicated TF. Beads were washed two times with sonication buffer, one time with sonication buffer with 500 mM NaCl, one time with LiCl wash buffer (20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 250 mM LiCl, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5% Na-deoxycholate) and one time with TE with 50 mM NaCl. DNA was eluted in elution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCL pH 8.0, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS). Cross-links were reversed overnight. RNA and protein were digested using RNase A and Proteinase K, respectively and DNA was purified with phenol chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Target-specific binding was analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR on a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) using with Platinum SYBR green pPCR SuperMIX-UDG with ROX (Invitrogen) using primers targeting either the Intron-4-Enhancer or an adjacent negative control in the SNCA locus or a unrelated negative control region on Chromosom 8. Target-specific binding of the intron-4-enhancer or control region for each antibody was calculated as fold-enrichment over IgG-Isotype control ChIP. Similarly processed H3K27ac samples post-purification were used to prepare Illumina multiplex sequencing libraries. Libraries for Illumina sequencing were prepared following the Illumina TruSeq DNA Sample Preparation v2 kit protocol with the following exceptions. After end-repair and Atailing, Immunoprecipitated DNA (~10–50 ng) or Whole Cell Extract DNA (50 ng) was ligated to a 1:50 dilution of Illumina Adaptor Oligo Mix assigning one of 24 unique indexes in the kit to each sample. Following ligation, libraries were amplified by 18 cycles of PCR using the HiFi NGS Library Amplification kit from KAPA Biosystems. Amplified libraries were then size-selected using a 2% gel cassette in the Pippin Prep system from Sage Science set to capture fragments between 300 and 700 bp. Libraries were quantified by qPCR using the KAPA Biosystems Illumina Library Quantification kit according to kit protocols. Libraries with distinct TruSeq indexes were multiplexed by mixing at equimolar ratios and running together in a lane on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 for 40 bases in single read mode. Reads were de-multiplexed by their adaptor ID and aligned to the hg19 version of the human reference genome using bowtie 1.1.1 with parameters –wrapper basic-0 –p 4 –k 2 –m 2 –sam and –l 4039.

PD-associated SNP prioritization-based overlap with epigenetic enhancer marks

We prioritized PD-associated high-confidence enhancer elements as being broadly active throughout the CNS based on the observation PD-associated pathology is not exclusively localized to the substantia nigra but rather affects a wide variety of CNS cell types40–42. DHSs datasets were included because the comparison between fetal and adult DHSs harboring disease-associated GWAS variants suggests that the vast majority of these DHSs are already established in fetal tissues3. Mapped read files of H3K27ac ChIP-Seq, H3K4me1 ChIP-Seq, H3K4me3 ChIP-Seq, and DNase I-Seq created as part of the Human Epigenome Roadmap Project were downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), and the samples used are summarized in Supplementary Table 3f. These datasets were used to prioritize PD-associated SNPs by their presence in putative regulatory regions in human brain samples. (Supplementary Table 1). Regions of enrichment in H3K27ac signal, H3K4me1 signal, H3K4me3, or DNase hypersensitivity in human samples were calculated using MACS 1.4.243 using parameters -p 1e-9,–keep-dup = auto, and -g hs with no control library. For each SNP in the SNCA locus from hg19 chromosome 4 position 90453241 (rs67262058) to position 91220981 (rs17016715) (463 SNPs, p < 5 × 10–8 provided by PDgene database12,44), the number of datasets with a region enriched in H3K4me1, H3K27ac, or DNase hypersensitivity contacting or containing the SNP were summed. SNPs were ranked by this sum. SNPs in the promoter region of SNCA were excluded based the overlap of H3K4me3 peaks, a histone modification that is enriched at the transcription start site (TSS) of actively expressed genes identified in each ChIP-Seq sample.

Display of ChIP-Seq and DNase I-Seq signal

WIG files for display of read pileup for ChIP-Seq and DNase I-Seq performed by the Epigenome Roadmap Consortium were downloaded from GEO, and these samples are compiled in Supplementary Table 3f. For new datasets generated for this manuscript we created WIG files representing read counts in 50bp bins using macs 1.443 with parameters –w –S –space=50 –nomodel –shiftsize –p 1e-9 –keep-dup=1. Samples were normalized to reads in each bin per million mapped reads to enable cross-sample comparisons. This was achieved by dividing the value in each bin by the millions of mapped reads per sample and conversion to TDF files for display in IGV using igvtools.

Relative enhancer ChIP-seq signal calculation in CRISPR/Cas9 targeted cells

For Extended Data Fig. 7e, the signal of H3K27ac ChIP-Seq at the enhancer containing the variable allele was calculated in five cell lines with and without deletion or additional alteration of the underlying sequence. The SNP-containing enhancer was defined as chr4: 90673430–90675431, and the 3′ enhancer used for normalization was defined as chr4: 90629326–90631326. Aligned reads in these windows were counted using intersectBed45 Because visual inspection indicated that the 3′ enhancer was consistent in signal, and because no genetic perturbation to this region was performed, we used the read count in this region to normalize across samples for comparison. The ratio of number of reads in the variable SNP-containing enhancer divided by reads in the 3′ region is reported.

Conditional GWAS meta-analysis

Genomewide SNP data was obtained for 5 cohorts (GenePD/PROGENI, phs000126.v1.p1; NINDS, phs000089.v3.p2; NGRC, phs000196.v2.p1; APDGC, phs000394.v1.p1; WTCCC, EGAS00000000034;). Each cohort was imputed to the 1000G phase 3 reference genome using Minimac46,47. Baseline and conditional association of the GWAS hits reported by Nalls et al. to PD risk was performed using SAS for each of the 5 cohorts as describe previously12. Association results for each cohort were combined using fixed effects models with standard error weighting implemented in METAL48.

eQTL study in PD and control postmortem frontal cortex

The SNCA gene expression dataset and analysis methods used here have been described previously49. In brief, SNCA expression levels were assayed from 165 samples using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. The Relative Standard Curve Method was used to transform the Ct values into quantity units. The base 10 logarithm of the SNCA expression values was used for all analyses, to ensure the normal distribution of data required by the statistical tests performed. SNP genotyping was performed as part of the US PD-GWAS Consortium meta-analysis replication sample50. As described in the consortium study, the samples were genotyped at the Center for Inherited Disease Research (CIDR) using a custom Illumina genotyping array of 768 SNPs. Because the tested SNP dataset did not include the top reported PD-associated SNP rs356182 in the SNCA locus, we included rs356229 as proxy for this SNP (R2 = 0.62) in our analysis. After QC, genotyping and expression data was available for 86 cases and 41 controls for eQTL analysis. Expression models were analyzed including adjustment for disease status, sex, pH, age at death, as well as for the interaction between PMI and disease status and significance was assessed using a one sided test based on the a priori hypothesis of an association of the G-allele at rs356168 with increased SNCA expression.

TF binding site prediction

We extracted the nucleotide sequence for the region chr4:90450000–91221000, that includes the SNCA locus, using the hg19 genome release, and made a alternative ”minor allele” version of the sequence that contains all PD-associated SNP-derived minor alleles from position 90453241 (rs67262058) to position 91220981 (rs17016715). Any minor allele SNPs less than 50 nt apart were included in separate sequence files. This way we could evaluate the effect of the minor allele within the reference wt sequence context. We predicted all TF binding sites for the reference sequence and the sequences containing minor alleles using match, the matrix library “matrix.dat” from the TRANSFAC Release 2014.1, and the matrix profile minSUM_good.prf. We summarized the TFs predicted to bind the wt and minor allele sequences with the BEDTools suite and a custom perl script. To select candidate TFs, the list of differential binding matrices was filtered for TFs that (i) show high expression levels in the top 25th percentile of all transcripts based on RNA-sequencing data derived from in vitro differentiated neurons (data not shown), (ii) show robust expression in disease-relevant brain areas based on data from the Allen Brain Atlas51 and (iii) display gene ontology (GO) terms related to CNS function52,53.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

HEK-293 cells transiently transfect using X-tremeGene 9 (Roche) with plasmids expressing either EMX–Myc-DDK or NKX6-1-Myc-DDK (pCMV6-Entry, OriGene) or wild-type cells were used to prepare nuclear extracts according to standard protocols. Gel-shift assay was performed with the LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (Thermo scientific) according to manufactures instructions. For the competition experiments, 5′-biotin-labeled oligonucleotides carrying either the A-allele or G-allele at rs356168 spanning 60 bp around the SNP and corresponding unlabeled competitor oligonucleotides (all Integrated DNA technologies) were included in the binding reaction to determine the allele-specific binding of EMX2 or NKX6-1 respectively. Binding reactions were separated using precast 6% DNA-retardation gels or 4–20% TBE gels (Life Technologies) in 0.5XTBE, electrophoretically transferred to Biodyne B nylon membranes (Thermo Scientific) and detected by chemiluminescence.

DOX-inducible expression of EGFP, EMX2 and NKX6-1 in hESC-derived neurons

Myc-DDK-tagged human cDNAs for EMX2 and NKX6-1 (derived from pCMV6-Entry Clones, OriGene) were subcloned into FUW-Tet-O-EGFP vectors to generate the FUW-Tet-O-EMX2 and FUW-Tet-O-EMX2 doxycycline-responsive lentiviral vectors. VSVG-coated lentiviruses were generated in 293T cells as described previously54 Briefly, 293T cells were transfected with a mixture of viral plasmid and packaging constructs expressing the viral packaging functions and the VSV-G protein. Culture medium was changed 12 hours post- transfection and virus-containing supernatant was collected 60–72 hours post transfection. Viral supernatant was filtered through a 0.45μm filter. Virus-containing supernatants were concentrated by ultracentrifugation. All experiments were performed in 2 individual clones derived from WIBR3 cells, in which the constitutive active reverse tetracycline transactivator (AAVSI-neo-M2rtTA) was targeted into the AAVSI “safe habor” locus as described previously36,55. In vitro differentiated neural precursors derived from these cells lines were transduced with various amounts of concentrated virus for 24 hours. Only cultures that expressed the transgenes in more than 75% of the cells (as determined by GFP fluorescence and immunostaining for expression of the DDK-tag) were used for further experiments. Transduce cells were terminally differentiated for 21 days. Transgene expression was induced in 24 well plates by supplementing the medium with doxycycline (DOX) at a final concentration of 2 μg/ml. DOX-induced transgene expressing samples and untreated isogenic controls were lysed 72 hours after DOX and subsequently analyzed by qRT-PCR.

Single molecule mRNA flouresence in situ hybridization (FISH)

We performed RNA FISH as outlined previously56–58. The neuronal cultures (differentiation day21) were washed with HBSS, detached and dissociated into single cells with HBSS and subsequently fixed with Paraformaldehyde at a final concentration of 4%. The cells were incubated for 10 minutes while rotating to avoid clumping of cells. After 10 minutes the cells were spun down for 6 min at 1000rpm. To permeablize the cells, the cells were placed in 70% ethanol overnight. The next day the cells were attached to chambered cover slides (Nunc Lab-Tek) coated with poly-l-lysine. The 20nt probes for EMX2 and NKX6-1 were manually designed and ordered through Biosearch Technologies, coupled with either Cy5-flurophore or Alexa594-flurophore (Invitrogen) respectively and hybridized with standard Fish hybridization buffer containing 25% formamide. For hybridization conditions 75ng probes per ul of hybridization buffer were used. The probes were hybridized for 16 h at 30 °C followed by two wash steps with wash buffer containing 25% formamide and 2x SSC. The cells were counterstained with Hoechst 33342. During imaging the cells were kept in a solution containing PBS, Glucose, Catalase and Trolox to avoid bleaching of flurophores. All images were taken with a Nikon Ti-E inverted fluorescence microscope equipped with a 100X oil-immersion objective and a Photometrics Pixis 1024 CCD camera using MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices, Downington, PA). A total of 100 cells were counted for quantification. Cells that seemed fragmented or had an excessive amount of background were excluded. All cells with more than 2 transcripts for either NXK6-1 or EMX2 were counted as positive for the respective transcript.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells were fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20min at room temperature, and rinsed with PBS. Following membrane permeabilization with PBS containing 0.2 % Triton, cells were blocked with 5% normal donkey serum and stained with indicated primary antibodies (Supplementary Table 3e) overnight at 4°C. Immunostainings were visualized by appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa 488, 568, 594, 633 (Life Technologies), followed by counter-staining with DAPI.

Extended Data

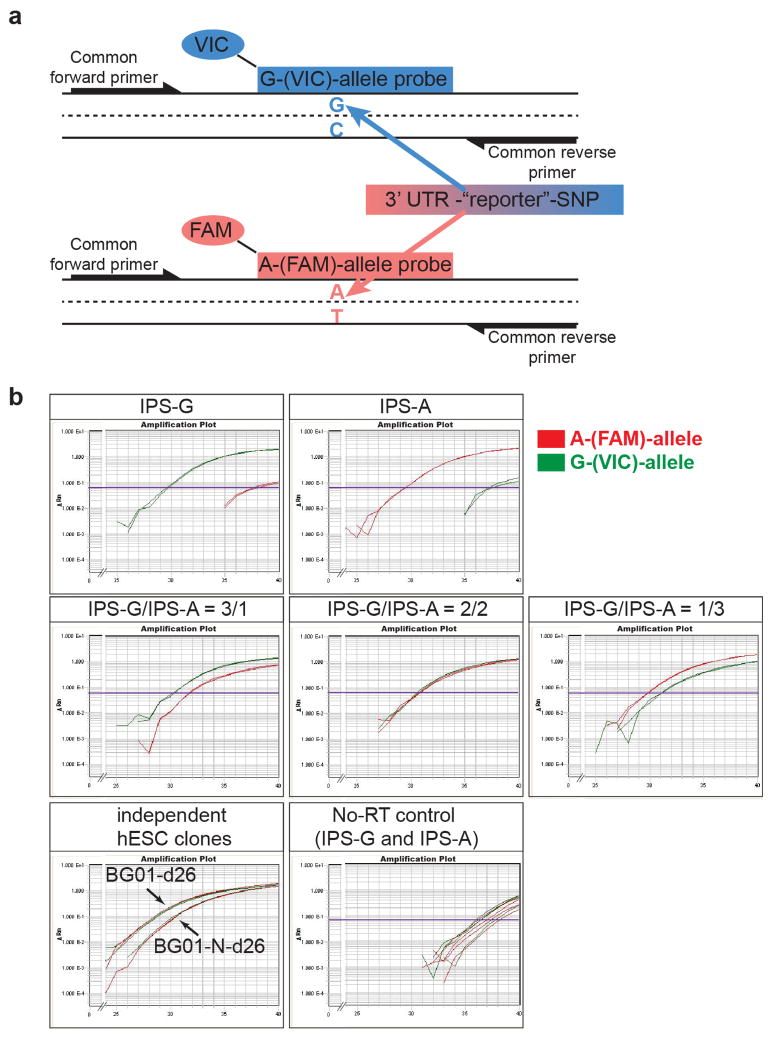

Extended data Fig. 1. Analysis of allele-specific expression of SNCA using quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR).

(a) Schematic illustration of the quantitative allele-specific SNCA expression analysis using a common primer pair and allele-specific Taqman® probes conjugated with different fluorophores to specifically detect a reporter-SNP (rs356165) in the 3′UTR of SNCA in a multiplex reaction. As indicated, 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM) and 4,7,2′-trichloro-7′-phenyl-6-carboxyfluorescein (VIC) were used to detect the A- and G-allele respectively. (b) Representative multiplex qRT-PCR reactions (in duplicates) measuring allele-specific SNCA expression of allele-biased samples described in Fig. 1c,d. Allele-biased samples were generated by mixing hIPSC-derived neurons homozygous for either the A-(IPS-A) or G-allele (IPS-G) at rs356165 at indicated ratios. Also included is a plot showing c-DNAs synthesized in the absence of SuperScript® reverse transcriptase (no-RT) to control for genomic DNA contaminations. Plots are displayed as reporter dye fluorescence signal (ΔRn) in log scale as a function of run cycle.

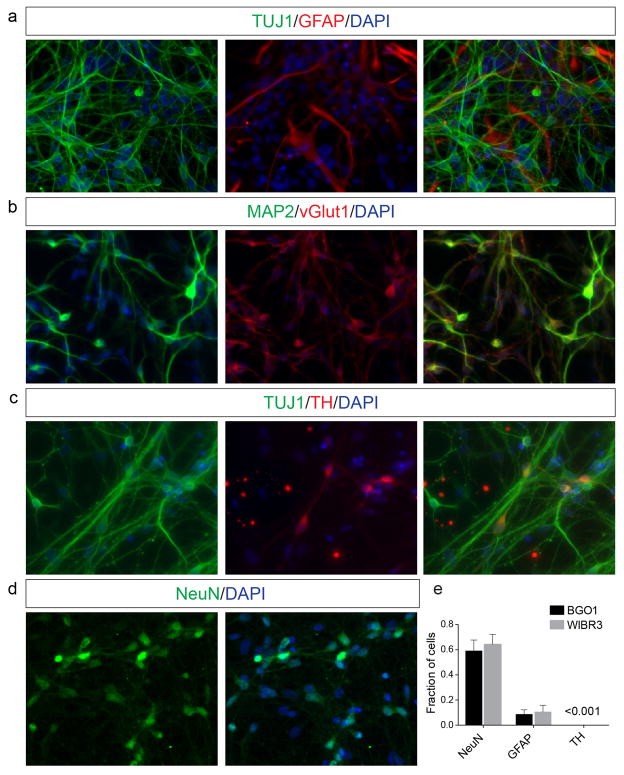

Extended data Fig. 2. Analysis of in vitro differentiated hESC-derived mixed neuronal cultures.

(a–d) Immunostainings of in vitro differentiated mixed neuronal cultures (differentiation day 28) for expression of neuron- and astrocyte-specific markers. Shown are representative images for staining of (a) neuron-specific beta-III-tubulin (TUJ1) and astrocyte specific glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), (b) neuron-specific microtubule associated protein 2 (MAP2) and glutamatergic neuron-specific glutamate vesicular transporter 1 (vGLUT1), (c) TUJ1 and dopaminergic neuron-specific tyrosine-hydroxylase (TH) and (d) the pan-neuronal marker NeuN, which was used for relative quantification. (e) Quantification of a representative in vitro differentiation experiment in hESC line WIBR3 and BGO1. The quantification of rare TH-positive cells was only estimated. Source data are provided as Source Data for Extended Data Figure 2.

Extended data Fig. 3. Identification of PD associated risk variants overlapping with distal enhancers in the SNCA locus.

(a) Detailed H3K4me1 and H3K27ac ChIP-Seq and DHSs-enrichment tracks for indicated CNS regions in the SNCA locus. Shown are the locations of NACP-Rep1 and PD-associated SNPs overlapping with two proximal enhancer elements (3′UTR enhancer and intron-4 enhancer) highlighted by light gray boxes. On the right, enlarged view of 3′UTR enhancer and intron-4 enhancer relative to top ranked PD-associated SNPs. (b) Enlarged view of intron-4-enhancer region showing H3K4me1 and H3K27ac Chip-seq enrichment tracks for substantia nigra and DHSs enrichment tracks for fetal brain relative to location of PD-associated SNPs. Shown below is number of predicted TF binding sites for reference (in red) and alternative SNP (minor allele) sequence (in blue) at each genomic position. Gray box indicates location of deletion described in Fig 2b and Extended Data Fig. 5a. (c) Summery of all PD-associated SNPs in the SNCA locus ranked by cumulative overlap with H3K4me1, H3K27ac and DHSs enhancer marks. Table summarizes the top 7 ranked SNPs with PD-association p-values, odd ratios (OR), number of predicted differential TF binding sites (Diff TFB) and location within enhancer elements as marked in (a). (d) Gene tracks showing H3K4me1 and H3K27ac enrichment in the SNCA locus for in vitro hESC-derived neurons (differentiation day 31).

Extended data Fig. 4. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing strategy for targeted insertion of PD–associated intron-4 enhancer elements in hESCs.

(a) Schematic illustration of the CRISPR/Cas9-mediated 2-step genome editing strategy to delete and subsequently insert indicated intro-4 enhancer sequences containing the PD-associated risk SNPs rs356168 and rs3756054. Shown are the genomic organization of the SNCA locus, an enlarged view of wild-type and deleted (ΔE4) alleles, grand targeting sequences (underlined, PAM sequence in red), restriction sites, Southern blot (SB) probes and design of targeting vectors (TV; risk SNPs are highlighted in red). (b) Representative Southern blot analysis of indicated targeted WIBR3 hESCs (ΔE4/TV-A-T) compared with wild-type cells or hESCs carrying homozygous deletions (ΔE4/ΔE4). (c) Table summarizing intron-4 enhancer deletions and insertions of indicated haplotypes in WIBR3 hESCs. Correct targeting was determined by Southern blot analysis and genomic sequencing. Cell lines with targeted enhancer elements confirmed to be in cis with A-(FAM)-reporter SNP (determined by genomic sequencing-based phase-reconstruction) were maintained for subsequent analysis (compare Fig. 2b).

Extended data Fig. 5. Effect of intron-4-enhancer modification on total and allele-specific expression of SNCA.

(a, b) Analysis of total SNCA expression in in vitro derived (a) neural precursors (same samples analyzed in Fig. 2c) and (b) mixed neuronal cultures (same samples analyzed in Fig. 2d) from targeted cell lines with indicated SNP genotypes at rs356168 and rs3756054 (compare Fig. 2b) compared to hESCs harbouring homozygous deletions of the intron-4 enhancer (ΔE/ΔE). qRT-PCR data are normalized to GAPDH and presented relative to the expression of ΔE/ΔE cells. (c) Expression analysis for the neuron-specific marker microtubule associated protein 2 (MAP2) and astrocyte specific glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) by qRT-PCR in in vitro differentiated neurons described in (b). Data are normalized to 60S acidic ribosomal protein P0 (RPLP0) and presented relative to the expression of ΔE/ΔE neurons. Data are shown as mean ± s.d. of 3 biological replicates (each representing 3 technical replicates) for independent targeted clones as described in Fig. 2c,d (n indicates number of independently targeted clones per genotype; ΔE/ΔE, n = 4; A–T/ΔE, n = 4; G–C/ΔE, n = 3; A–C/ΔE, n = 3; G–T/ΔE, n = 2/3). (d) Alternative presentation of data displayed in Fig. 2c as dot blot grouped according to SNPs rs356168 and rs3756054 (excluding data for cells carrying homozygous deletions (ΔE4/ΔE4) of the intron 4 enhancer). (e) Table summarizing the results of corresponding two-way ANOVA analysis for allele-specific SNCA expression in neural precursors (each dot represents mean of 3 technical replicates, black bars indicate mean for each genotype). (f) Alternative presentation of data displayed in Fig. 2d as dot blot grouped according to SNPs rs356168 and rs3756054 (excluding data for cells carrying homozygous deletions (ΔE4/ΔE4) of the intron 4 enhancer). (e) Table summarizing the results of corresponding two-way ANOVA analysis for allele-specific SNCA expression in mixed neuronal cultures (each dot represents mean of 3 technical replicates, black bars indicate mean for each genotype). Allele-specific expression for each clone was analyzed in 3 independent biological replicate experiments and combined according to genotypes, n indicates number of independently targeted clones per group, † indicates an additional sub-clone derived from one of the two targeted clones for this genotype. Two-way ANOVA analysis (alpha = 0.05) was calculated based on allele-specific expression of all biological replicates. *P < 0.0001. (h) Schematic illustration of the experimental strategy for CRISPR/Cas9-mediated deletion of the intron-4-enhancer element. Genomic sequencing-based phase-reconstruction, to analyze the phase of the heterozygous enhancer SNP rs356168 in wild-type WIBR3 cells indicates that the functional G-allele at rs356168 is in cis with the G-allele of the reporter SNP rs356165. (i) Relative allele-specific SNCA expression (Boxplots showing median, 25th and 75th percentiles with whiskers indicating min and max) in neural precursors comparing wild-type cells to ΔE4/ΔE4 cells harboring homozygous deletions (expression is calculated relative to ΔE4/ΔE4 neural precursors). Note that the expression of the A-(FAM)-allele (displayed on the left Y-axis) is reciprocal to the expression of the G-(VIC)-allele (displayed on the right Y-axis). Statistically significant differences between groups were calculated using unpaired two-tailed t-test. n indicates number of independent sub-clones for wild-type cells or independently deleted clones for ΔE4/ΔE4 cells; allele-specific expression for each clone was analyzed in 3 independent biological replicate experiments at passage 1 and 2 respectively, each measured as 3 technical replicates. **P<0.0001. (j) qRT-PCR expression analysis for total SNCA in same samples as described in (i). Data are normalized to GAPDH and displayed relative to the expression of ΔE4/ΔE4 neural precursors. Data are displayed as mean ± s.d.; Source data and detailed statistical analysis are provided as Source Data for Extended Data Figure 5.

Extended data Fig. 6. Conditional GWAS and eQTL analysis to assess the effect of PD risk SNP rs356168.

(a) Table showing baseline and conditional GWAS analysis in 5 publicly available PD GWAS cohorts (totaling 6014 cases and 9119 controls) to assess the extent to which rs356168 explains the observed associations in the SNCA locus of the top reported GWAS SNP rs356182 and the independent 5′ region SNP rs768115412 (b) qRT-PCR analysis for SNCA expression in postmortem frontal cortex tissue obtained from PD patients and controls stratified by risk genotype at rs356168 (number of brain samples from PD patients and controls are indicated for each genotype). Expression models were analyzed including adjustment for disease status, sex, pH, age at death, as well as for the interaction between PMI and disease status. Significance was assessed using a one sided test based on the a priori hypothesis of an association between the G-allele at rs356168 and increased expression of SNCA. P-values comparing each genotype are displayed in the graph. Alternatively analysis using linear regression shows a significant increase of total SNCA levels in carriers of G-allele at rs356168 (p = 0.031).

Extended data Fig. 7. PD-associated risk variants have little effect on enhancer-specific chromatin modifications at intron-4-enhancer.

(a) Overview of isogenic cell lines (derived from WIBR3 hESCs) carrying distinct genotypes of the intron-4-enhacer element used for chromatin-immunoprecipitation (ChIP-qRT-PCR and ChIP-seq). (b, c) ChIP-qRT-PCR analysis in neurons derived from isogenic cell lines with indicated genotypes for binding of the enhancer-specific chromatin marks H3K4me1 (b) and H3K27ac (c) at the intron-4 and 3′UTR enhancer sequences compared with indicated negative control regions (calculated as percent of input). (d) Gene tracks of ChIP-seq analysis for the active enhancer mark H3K27ac in in vitro differentiated neurons derived from isogenic cell lines with indicated genotypes. (e) Quantitative read density analysis of H3K27ac Chip-seq data (as shown in d) displaying relative read density of the intron-4 enhancer compared to the 3′UTR enhancer to control for variability between ChIP experiments. Source data are provided as Source Data for Extended Data Figure 7.

Extended data Fig. 8. Sequence-specific binding of CNS expressed TFs EMX2 and NKX6-1 at SNCA intron-4-enhancer.

(a) ChiP-qRT-PCR for binding of indicated TFs at the intron-4 enhancer element compared with negative control region in the SNCA locus (calculated as fold enrichment compared with IgG Isotype control) in hESC line BGO1 and hIPSC line IPS-PDC16 (derived from fibroblast AG20446). (b, d) Western blot analysis in nuclear extracts (NEs) (used for experiments displayed in Fig. 3 and Extended Data Fig 8c,e) from HEK293 cells overexpressing (b) Myc-DDK-tagged EMX2 or (d) NKX6-1 using indicated antibodies against DDK-(FLAG)-tag, EMX2 and NKX6-1 respectively. Lamin A was used to control for equal loading in NEs (c, e) EMSA analysis to determine TF concentration-dependent sequence-specific binding of (c) EMX2 and (e) NKX6-1 to oligonucleotides harboring the indicated genotype at rs356168 (A/G-allele). NEs from HEK293 cells overexpressing Myc-DDK(Flag)-tagged EMX2 (c) or NKX6-1 (e) were diluted with NEs from wild-type cells at indicated fractions to generate a TF concentration gradient. Relative EMX2 and NKX6-1 protein concentration in mixed samples were determined by Western blot analysis using an antibody against the DDK(Flag)-tag (panel below respective EMSA). Red arrows point to oligonucleotide-specific binding of overexpressed TFs. Source data are provided as Source Data for Extended Data Figure 8.

Extended data Fig. 9. Single molecular mRNA FISH analysis and immunostaining for TFs EMX2 and NKX6-1 in mixed neuronal cultures.

(a) Single molecule mRNA FISH for EMX2-(Cy5) and NKX6-1-(Alexa594) (displayed in false color) labeling EMX2 and NKX6-1 mRNA transcripts in WIBR3-derived in vitro differentiated neurons (differentiation day 21). Cultured neurons were dissociated before hybridization and attached to a glass slide before imaging. Representative images show multiple cells, which are either single-positive for EMX2 (green arrowhead) or double-positive for EMX2 and NKX6-1 (white arrowhead). (b–d) Representative images showing individual cells which are either double positive for the expression of EMX2 and NKX6-1 (b) or single positive for either NKX6-1 (c) or EMX2 (d). (e) Quantification of 100 individual cells for the presence of EMX2 and NKX6-1 transcripts. (f–k) Co-immunostaining for EMX2, NKX6-1,neuron specific beta-III-tubulin (TUJ1) and astrocyte specific glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in mixed neuronal cultures. Source data are provided as Source Data for Extended Data Figure 9.

Extended data Figure 10. NACP-Rep1 repeat length has no cis-acting effect on SNCA expression in hESC derived neurons.

(a) Schematic illustration of the CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing strategy to generate heterozygous deletions (ΔRep1/wild-type) in WIBR3 and BGO1 hESCs and subsequently insert indicated NACP-Rep1 length variants. Displayed are the genomic organization of the SNCA locus, an enlarged view of the wild-type and NACP-Rep1 deleted (ΔRep1) allele, targeting-targeting sequences (underlined, PAM sequence in red), restriction sites and Southern blot (SB) probe. Shown below is targeting vector (TV) design to insert the respective NACP-Rep1 elements (Rep1-257, Rep1-259, Rep1-261 and Rep1-263) with indicated repeat sequences. Only clones with heterozygous deletion of the repeat element on the same chromosome were identified based on the genotype of two heterozygous SNPs (rs58864428 and rs10030935) upstream and downstream of NACP-Rep1 and selected for subsequent experiments. (b) Representative Southern blot analysis of wild type and targeted WIBR3 hESCs with indicated NACP-Rep1 genotypes (modified alleles highlighted in red; no targeted wild-type allele represents NACP-Rep1-261 element). (c) Table summarizing NACP-Rep1 deletions and insertions in WIBR3 and BGO1 hESCs. (d) Representative fragment length analysis confirms expected NACP-Rep-1 repeat length in targeted cell lines. Red line indicates NACP-Rep1-261 peak at 269 bp. (e, f) Analysis of relative allele-specific SNCA expression in neurons (differentiation day 25) derived from targeted cells lines with indicated NACP-Rep1 alleles compared with untargeted controls in WIBR3 (e) and BGO1 (f) hESCs (expression was normalized relative to wild-type cells). Shown are mean values ± s.d. of three independent biological replicate experiments for each individual clone of the indicated genotype. Differences between individual clones or combined clones by genotypes were not significant based on one-way ANOVA testing for multiple comparisons between groups (alpha = 0.05) and did show a repeat length-dependent linear trend analyzed by linear regression. Source data are provided as Source Data for Extended Data Figure 10.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the investigators of the original PD GWAS meta-analysis and PDGene and Menno Creyghton at the Hubrecht Institute for sharing data used for this study. We would like to thank Batula Zaidi for helpful discussion in conceiving this work. We thank Raaji Alagappan, Dongdong Fu and Tenzin Lungjangwa for technical support and help hESC culture and molecular biology and Ana D’Alessio for helpful advice to perform ChiP-seq experiments. We would like to thank Patti Wisniewski, Michael Ly, Colin Zollo and Chad Araneo of the Whitehead Institute FACS facility for their help with cell sorting, Tom Volkert, Jennifer Love and Sumeet Gupta at the Whitehead Genome Technologies Core for Solexa sequencing, Wendy Salmon and Nicki Watson from the W.M. Keck Biological Imaging Facility and Tom DiCesare for help with the figure illustrations. We thank all the members of the Jaenisch lab for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript. R.J. was supported by NIH grants 1R01NS088538-01 and 2R01MH104610-15 and by Qatar National Research Fund grant number NPRP 5-531-1-094.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is available in the online version of the paper.

Authors Contributions F.S. and R.J. conceived the project, designed and supervised the experiments, interpreted results and wrote the paper with input from all authors. Y.S. assisted with ChIP experiments and contributed to preparation of manuscript. C.S.S. assisted with CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing. B.J.A. performed computational analysis of epigenetic datasets and prioritization of PD-associated SNPs. J.C.L performed conditional GWAS and eQTL analysis. M.I.B. performed computational analysis to predict TFB. J.G. performed sm-mRNA-FISH analysis. R.H.M and R.A.Y supervised data analysis, interpreted results and contributed to manuscript preparation. F.S. performed all other experiments.

Raw data from ChIP-seq analysis have been submitted to the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus under the accession number GSE71278.

Readers are welcome to comment on the online version of the paper.

References

- 1.McClellan J, King MC. Genetic Heterogeneity in Human Disease. Cell. 2010;141:210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ernst J, et al. Mapping and analysis of chromatin state dynamics in nine human cell types. Nature. 2011;473:43–49. doi: 10.1038/nature09906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maurano MT, et al. Systematic Localization of Common Disease-Associated Variation in Regulatory DNA. Science. 2012;337:1190–1195. doi: 10.1126/science.1222794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trynka G, et al. Chromatin marks identify critical cell types for fine mapping complex trait variants. Nat Genet. 2013;45:124–130. doi: 10.1038/ng.2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hnisz D, et al. Super-Enhancers in the Control of Cell Identity and Disease. Cell. 2013;155:934–947. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Degner JF, et al. DNase I sensitivity QTLs are a major determinant of human expression variation. Nature. 2012;482:390–394. doi: 10.1038/nature10808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kilpinen H, et al. Coordinated Effects of Sequence Variation on DNA Binding, Chromatin Structure, and Transcription. Science. 2013 doi: 10.1126/science.1242463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McVicker G, et al. Identification of Genetic Variants That Affect Histone Modifications in Human Cells. Science. 2013 doi: 10.1126/science.1242429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kasowski M, et al. Extensive Variation in Chromatin States Across Humans. Science. 2013 doi: 10.1126/science.1242510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leung D, et al. Integrative analysis of haplotype-resolved epigenomes across human tissues. Nature. 2015;518:350–354. doi: 10.1038/nature14217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singleton AB, Farrer MJ, Bonifati V. The genetics of Parkinson’s disease: Progress and therapeutic implications. Mov Disord. 2013;28:14–23. doi: 10.1002/mds.25249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nalls MA, et al. Large-scale meta-analysis of genome-wide association data identifies six new risk loci for Parkinson’s disease. Nat Genet. 2014:1–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devine MJ, Gwinn K, Singleton A, Hardy J. Parkinson’s disease and α-synuclein expression. Mov Disord. 2011;26:2160–2168. doi: 10.1002/mds.23948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller DW, Hague SM, Clarimon J, Baptista M. α-synuclein in blood and brain from familial Parkinson disease with SNCA locus triplication. Neurology. 2004 doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000127517.33208.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim HJ, Jeon BS, Yoon MY, Park SS. Increased expression of alpha-synuclein by SNCA duplication is associated with resistance to toxic stimuli. Journal of Molecular …. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s12031-012-9732-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soldner F, et al. Parkinson’s disease patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells free of viral reprogramming factors. Cell. 2009;136:964–977. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vermunt MW, et al. Large-Scale Identification of Coregulated Enhancer Networks in the Adult Human Brain. Cell Rep. 2014;9:767–779. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ward LD, Kellis M. Interpreting noncoding genetic variation in complex traits and human disease. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:1095–1106. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rivera CM, Ren B. Mapping Human Epigenomes. Cell. 2013;155:39–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium et al. Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature. 2015;518:317–330. doi: 10.1038/nature14248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Creyghton MP, et al. Histone H3K27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:21931–21936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016071107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rada-Iglesias A, et al. A unique chromatin signature uncovers early developmental enhancers in humans. Nature. 2011;470:279–283. doi: 10.1038/nature09692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mariani J, et al. Emx2 is a dose-dependent negative regulator of Sox2 telencephalic enhancers. Nucleic Acids Research. 2012;40:6461–6476. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ligon KL. Loss of Emx2 function leads to ectopic expression of Wnt1 in the developing telencephalon and cortical dysplasia. Development. 2003;130:2275–2287. doi: 10.1242/dev.00421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaffer AE, Freude KK, Nelson SB, Sander M. Nkx6 transcription factors and Ptf1a function as antagonistic lineage determinants in multipotent pancreatic progenitors. Dev Cell. 2010;18:1022–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farrer M, et al. alpha-Synuclein gene haplotypes are associated with Parkinson’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1847–1851. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.17.1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cronin KD, et al. Expansion of the Parkinson disease-associated SNCA-Rep1 allele upregulates human -synuclein in transgenic mouse brain. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3274–3285. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiba-Falek O, Kowalak JA, Smulson ME, Nussbaum RL. Regulation of alpha-synuclein expression by poly (ADP ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) binding to the NACP-Rep1 polymorphic site upstream of the SNCA gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:478–492. doi: 10.1086/428655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soldner F, Jaenisch R. Medicine. iPSC disease modeling. Science. 2012;338:1155–1156. doi: 10.1126/science.1227682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soldner F, et al. Generation of Isogenic Pluripotent Stem Cells Differing Exclusively at Two Early Onset Parkinson Point Mutations. Cell. 2011;146:318–331. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lengner CJ, et al. Derivation of Pre-X Inactivation Human Embryonic Stem Cells under Physiological Oxygen Concentrations. Cell. 2010;141:872–883. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim J, et al. Direct reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts to neural progenitors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103113108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim JH, Panchision D, Kittappa R, McKay R. Generating CNS neurons from embryonic, fetal, and adult stem cells. Meth Enzymol. 2003;365:303–327. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(03)65022-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cong L, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang H, et al. One-Step Generation of Mice Carrying Mutations in Multiple Genes by CRISPR/Cas-Mediated Genome Engineering. Cell. 2013;153:910–918. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hockemeyer D, et al. Efficient targeting of expressed and silent genes in human ESCs and iPSCs using zinc-finger nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:851–857. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Research. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee TI, Johnstone SE, Young RA. Chromatin immunoprecipitation and microarray-based analysis of protein location. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:729–748. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sulzer D, Surmeier DJ. Neuronal vulnerability, pathogenesis, and Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2013;28:41–50. doi: 10.1002/mds.25095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferrer I, Martinez A, Blanco R, Dalfó E, Carmona M. Neuropathology of sporadic Parkinson disease before the appearance of parkinsonism: preclinical Parkinson disease. J Neural Transm. 2010;118:821–839. doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0482-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Irwin DJ, et al. Neuropathologic substrates of Parkinson disease dementia. Ann Neurol. 2012;72:587–598. doi: 10.1002/ana.23659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y, et al. Model-based Analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS) Genome Biol. 2008;9:R137. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lill CM, et al. Comprehensive Research Synopsis and Systematic Meta-Analyses in Parkinson’s Disease Genetics: The PDGene Database. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002548. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Quinlan AR. BEDTools: The Swiss-Army Tool for Genome Feature Analysis. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2014;47:11.12.1–11.12.34. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1112s47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Howie B, Fuchsberger C, Stephens M, Marchini J, Abecasis GR. Fast and accurate genotype imputation in genome-wide association studies through pre-phasing. Nat Genet. 2012;44:955–959. doi: 10.1038/ng.2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fuchsberger C, Abecasis GR, Hinds DA. minimac2: faster genotype imputation. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:782–784. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2190–2191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dumitriu A, et al. Cyclin-G-associated kinase modifies α-synuclein expression levels and toxicity in Parkinson’s disease: results from the GenePD Study. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:1478–1487. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]