Abstract

Despite a large body of literature covering sexual identity development milestones, we know little about differences or similarities in patterns of identity development among subgroups of the lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) population. For this study, we assessed identity milestones for 396 LGB New Yorkers, ages 18–59. Sexual identity and disclosure milestones, were measured across gender, sexual identity, race/ethnicity, and age cohort subgroups of the LGB sample. Men experienced most sexual identity milestones earlier than women, but they tended to take more time between milestones. LGBs in younger age cohorts experienced sexual identity milestones and disclosure milestones earlier than the older cohorts. Bisexual people experienced sexual identity and disclosure milestones later than gay and lesbian people. Timing of coming out milestones did not differ by race/ethnicity. By comparing differences within subpopulations, the results of this study help build understanding of the varied identity development experiences of people who are often referred to collectively as “the LGB community.” LGB people face unique health and social challenges; a more complete understanding of variations among LGB people allows health professionals and social service providers to provide services that better fit the needs of LGB communities.

Keywords: Sexual Minorities, Developmental Models, Gay/Lesbian/Bisexual, Ethnic/Minority Issues, Gender Differences

Healthy People 2020 identified “exploration of sexual/gender identity among youth” as an issue that “will need to continue to be evaluated and addressed over the coming decade” (HHS, 2013). It is important to understand the identity exploration process, including coming out, because of its implications for health interventions and because concepts of sexual identity continue to evolve. Coming out milestones are key moments in the development of lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) identities. The timing and order of milestones throughout the lifespan has been associated differences in self-esteem (Rosario, Schrimshaw & Hunter, 2011), internalized homophobia (Dube & Savin-Williams, 1999), and verbal and physical victimization (D’Augelli & Grossman, 2001). However, due to the intersectional, layered nature of LGB persons’ identities, these milestones are not experienced by all sexual minorities in the same way. For example, a program that aims to improve the health of LGB people may be received very differently by, say, a Latina lesbian woman than a Black bisexual man. Taking account of variation in the LGB population, we explore coming out milestones as they are experienced by different age, gender, and racial LGB subpopulations.

Coming out is not a single event, but a series of realizations and disclosures. The age at which sexual minorities first recognize their identity, tell others about their identity, and have same-sex relationships varies, and people may take different amounts of time between one milestone and the next. Scholars have proposed and tested models of sexual identity development for over 30 years. Cass (1979) developed an influential model, which outlined a six-stage linear psychological path of sexual identity development. Troiden (1989) built upon Cass’s model and reframed it within four stages: (a) sensitization, which may include a person’s first same-sex attraction and their first questioning of their heterosexual socialization; (b) identity confusion, a period during early to mid-adolescence that is marked by inner turmoil and often the initiation of same-sex sexual activity; (c) identity assumption, when a youth self-identifies as LGB and begins to reveal their “true self” to select people and seeks community among other LGBs; and (d) commitment, which is marked by the initiation of a same-sex romantic relationship and disclosure to a wide variety of heterosexual people (Floyd & Stein, 2002). These models suggest that healthy and stable sexual identity development necessitates the full permeation of sexual identity into all aspects of a person’s life.

However, the notion that identity development must lead to integration left out many lesbians and gay men who were content not “synthesizing” their sexual orientation into all aspects of their lives (Cox & Gallois, 1996) and it ignored the experience of intersectionality, where individuals manage their sexual identity in addition to race, class, gender, and other significant identities (Purdie-Vaughns, & Eibach, 2008). As such, scholarship from the mid-1990s forward has forgone a linear model in favor of examining different patterns of LGB experiences by looking at milestones, many focusing on three distinct aspects of sexual identity development: sexual identity milestones, disclosure milestones, and the time between milestones (Floyd & Stein, 2002; Grov, Bimbi, Nanin & Parsons, 2006; Parks & Hughes, 2007; Savin-Williams & Diamond, 2000). It is important to continue to study sexual identity development because sexual identities and the social environment in which sexual minorities come out continue to evolve. This study contributes to the literature by examining the milestone experiences of gender, age and racial/ethnic subpopulations within the LGB population.

Sexual Identity Milestones

Sexual identity milestones are used to identify life events that mark when an individual first recognizes, explores, or accepts their same-sex sexual attraction or identity (Floyd & Stein, 2002; Grov, Bimbi, Nanin & Parsons, 2006; Parks & Hughes, 2007; Savin-Williams & Diamond, 2000). Sexual identity milestones are measured by: the age a person first becomes aware of their same-sex attraction, the age of their first same-sex intimate relationship, and the age of first self-identification as a sexual minority (e.g., gay). Studies have found that cisgender gay and bisexual men experience sexual identity milestones at an earlier age than cisgender lesbian and bisexual women (Savin-Williams & Diamond, 2000; D’Augelli & Grossman, 2001; D’Augelli, Grossman & Starks, 2008).

There is limited consensus on differences in sexual identity milestones among racial/ethnic groups. One study found no significant differences among White, Black, and Latino LGBs in age of first awareness, first intimate relationship, or first realization of identity (Rosario, Schrimshaw & Hunter, 2004). In another study, Latino youth reported first awareness significantly earlier than Black or White youth (Dube & Savin-Williams, 1999). In a study of White, Black, Latino, and Asian participants, White female respondents were found to be out to their parents more often than female respondents of color, but no differences were found in the ages of first same-sex sexual activity (Grov, Bimbi, Nanin, & Parsons, 2006). As the authors noted, “A person of color may prioritize the development of a racial/ethnic identity over a sexual identity in response to many psychosocial and environmental barriers associated with race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status” (Grov, Bimbi, Nanin, & Parsons, 2006, p. 119).

The timing of sexual identity milestones has been correlated with sexual identity (gay or lesbian vs. bisexual) and age cohort. Studies have found that bisexuals report first being aware of their same-sex attraction several years later than both gay men and lesbians (Maguen, Floyd, Bakeman & Armistead, 2002; Gates, 2010; Floyd & Stein, 2002). When considering age cohort, younger cohorts of lesbians experienced sexual identity milestones at an earlier age than older cohorts (Grov, Bimbi, Nanin, & Parsons, 2006; Parks & Hughes, 2007). This acceleration may be explained by growing social acceptance of LGB people (Baunach, 2012).

Disclosure Milestones

Disclosure milestones refer to the ages sexual minorities tell others about their non-heterosexual identity. Disclosure milestones are often measured by the age a person discloses to: a member of their family of origin, an LGB friend, a heterosexual friend, or their co-workers.

Studies have found that younger cohorts of sexual minorities report significantly younger age of first disclosure than older cohorts, possibly reflecting the increased visibility and acceptance of LGB people over time (Dube & Savin-Williams, 1999; Grov, Bimbi, Nanin & Parsons 2006; Maguen, Floyd, Bakeman & Armistead, 2002; Parks & Hughes, 2007; Savin-Williams & Diamond, 2000). These studies did not find differences in age of first disclosure by gender, sexual identity, or race/ethnicity. While racial/ethnic identity is not associated with the age of first disclosure, it has been found to influence to whom sexual minorities disclose their identity. Findings suggest that White LGBs disclose their sexual identity to more types of individuals (i.e. family members, LGB or heterosexual friends, coworkers) than their racial/ethnic minority counterparts (Grov, Bimbi, Nanin, & Parsons 2006; Rosario, Schrimshaw & Hunter, 2004; Rosario, Schrimshaw & Hunter, 2006).

Time between Milestones

As mentioned earlier, the literature has moved away from a linear process of sexual identity development. However, scholars continue to examine the amount of time between various individual sexual identity and disclosure milestones to gain insight into the factors that affect individuals’ navigation of the development of their sexual minority status. For example, it has been suggested that experiences of stress, such as internal conflict about living as a sexual minority or living in an anti-LGB environment, could contribute to a greater time between when a person becomes aware of their sexual minority identity and when they first disclose that identity (D’Augelli, Hershberger, & Pilkington, 1998; Parks, 1999). The time between these same milestones also has been found to be shorter for younger cohorts than older cohorts, as has the time between first wondering about one’s non-heterosexual identity and first coming to accept it (Parks & Hughes, 2007). Women have reported a shorter time between first realization and first disclosure of their sexual identity (D’Augelli & Grossman, 2001, Savin-Williams & Diamond, 2000).

The Current Study

In the current study we explore sexual identity milestones in a sample that is diverse in regard to gender, age, race/ethnicity, and sexual identity. By considering various subpopulations together, the results of this study help us to understand better the varied identity development experiences of people who fall under the category of “the LGB community.” Grov, Bimbi, Nanin, and Parsons (2006) conducted a similar study that found differences by gender and age cohort, but not by race/ethnicity. Our study shows that these subpopulation differences hold true across different study populations.

In this study, we assess differences in coming out milestones among LGB individuals across gender, age cohort, racial/ethnic, and sexual orientation groups. Based on existing studies of patterns of sexual identity milestones, disclosure milestones, and/or the time between milestones we hypothesize that:

Lesbian and bisexual women experienced sexual identity milestones and disclosure milestones at a later age than gay and bisexual men;

Older cohorts of sexual minorities experienced sexual identity and disclosure milestones at a later age and have a longer time between milestones than younger cohorts.

There are no racial/ethnic group differences in sexual identity and disclosure milestones, or the time between milestones.

Bisexual men and women experienced sexual identity and disclosure milestones later than gay men and lesbian women.

Methods

Sample

Data for the present study were drawn from [REMOVED FOR BLIND REVIEW], a large epidemiological study of the relationship between stress, identity, and mental health among LGB and heterosexual populations in New York City. A case-quota sampling strategy designed to fill 16 cells defined by gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and age was employed to be representative of the diversity among LGBs in New York City. Equal numbers of cisgender men and women, and White, Black, and Latino individuals were recruited from venues such as coffee shops, social groups, and parks, as well as using snowball sampling. Excluded were venues that could potentially bias the sample due to over-representation of life events or disease, such as 12-step programs or support groups for individuals who had experienced antigay violence.

Potential respondents who were approached were asked to fill out a brief screening form that included questions about age, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender, sex at birth, zip code of residence, years of residence in New York City, and contact information. Those who wished to be screened at another time were provided with brochures and invitation cards so that they could call in and be screened over the phone. Eligible were individuals: ages 18 – 59 (consistent with major U.S. psychological and epidemiological studies); residents of New York City for at least two years (to prevent biases related to recent migration to New York City); self-identified as male or female (and their sex of birth matched their gender identity); gay, lesbian, or bisexual (but they could use other terms to refer to their sexuality, such as queer. Heterosexuals were also eligible but they are not included in this report); Black, Latino, or White (but they could use other terms to refer to these race/ethnicities, such as African American, African, Hispanic, etc.); and who spoke English.

Eligible individuals were contacted according to the preferred mode of communication identified during the recruitment screening process (most often by phone) and asked to participate in the study. Of all eligible individuals, the response rate was 79%, calculated using the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) formula as the proportion of interviewed respondents out of all the individuals who were interviewed and those who refused. The cooperation rate was 60%, calculated as the proportion of interviewed respondents out of all the eligible individuals who were interviewed, those who refused, and the eligible individuals whom interviewers were unable to contact (AAPOR, 2005; formulas RR2, and COOP2, respectively). Response and cooperation rates did not vary significantly by sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, or gender.

Study Procedures

Data were gathered using computer-assisted personal interviewing during in-person interviews lasting on average 3.8 hours. More information about the study and the methods is available at [REMOVED FOR BLIND REVIEW]. Procedures were approved by the [REMOVED FOR BLIND REVIEW] Institutional Review Board and the Institutional Review Board of [REMOVED FOR BLIND REVIEW]. The sample for the present study consisted of 396 men and women who self-identified as lesbian, gay, or bisexual (mean age = 32.43 years; SD = 9.24 years).

Participants were compensated $80 for baseline interviews (mean time 3.82 hours). Interviews took place at research offices in the Washington Heights and Chelsea neighborhoods of New York City; on some occasions, as needed, interviews occurred at another location that allowed for both privacy and convenience, such as the respondent’s home or office.

Measures

Dependent Variables

The dependent variables utilized in this study fell under one of three categories: sexual identity milestones, disclosure milestones, and the time between milestones. The sexual identity and disclosure measures were drawn from Martin and Dean (1987), and the time between milestones variable was created post-data collection. Measures included in this study are consistent with those most commonly used by sexual identity development researchers at the time the interviews were constructed. Each of the groups of variables is described in more detail below.

Sexual Identity Milestones

Participants were asked to report the age they experienced each of the following sexual identity milestones: age of first same-sex attraction (“At what age were you first sexually attracted to someone of the same sex as you?”), age of first same-sex intimate relationship (“At what age did you have your first intimate relationship with someone of the same sex, where you both felt like you were in love or romantically involved?”), and age of first self-identification (“At what age did you first realize that you were [Preferred Sexual Identity Label]”). Participants who answered “Don’t Know” or “Refuse to Answer” were coded as missing. To distinguish the age of first awareness of same-sex attraction (i.e. “age of first awareness”) from the age respondents first realized their identity as a sexual minority (i.e. “age of realization”), we refer to the latter milestone as the “age of first self-identification”.

Disclosure Milestones

Participants were asked to report the age of first disclosure to their family of origin, an LGB friend, and a heterosexual friend. For example, the age of first disclosure to a heterosexual friend was determined by asking, “At what age did you first tell a straight friend that you were [Preferred Sexual Identity Label]?” Those who answered “Don’t Know” or “Refuse to Answer” were coded as missing. Those who never disclosed to their family of origin, an LGB friend, or a straight friend (47, 11, and 21 participants, respectively) were excluded from the analysis for the relevant disclosure milestone.

Time between Milestones

“Time between” variables were generated for milestones that were expected to follow a linear chronological order. These include the time between age of first same-sex attraction and first same-sex intimate relationship, the time between age of first same-sex attraction and first self-identification, and the time between age of first self-identification and the first disclosures to a family member, an LGB individual, and a heterosexual friend. A time between variable was not calculated for those milestones which could not be theorized to follow a clear chronological order, such as the age of first same-sex intimate relationship and age of first self-identification. Negative values were included rather than dropped in the cases of those who did not follow our theorized chronological order so as to not over-represent sample means.

Demographic Characteristics

Participants self-reported their age, gender, race/ethnicity, and sexual identity. Descriptive statistics for these variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Race/ethnicity, gender, age cohort, and sexual identity of New York City LGB participants (N = 396)

| Variable | White | Black | Latino | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Age Cohort | ||||||||

| 18–29 | 176 (100) | 28 (42) | 32 (48) | 31 (46) | 30 (47) | 27 (42) | 28 (41) | |

| 30–44 | 174 (100) | 28 (42) | 25 (37) | 32 (48) | 27 (42) | 34 (53) | 28 (42) | |

| 45–50 | 46 (100) | 11 (16) | 10 (15) | 4 (6) | 7 (11) | 3 (5) | 11 (16) | |

| Sexual Identity | ||||||||

| Bisexual | 71 (100) | 4 (6) | 10 (15) | 12 (18) | 18 (28) | 12 (19) | 15 (22) | |

| Gay/Lesbian | 325 (100) | 63 (94) | 57 (85) | 55 (82) | 46 (72) | 52 (81) | 52 (78) | |

Respondents were classified into one of three age cohorts according to their date-of-birth: 18–29 years of age, 30–44, and 45–59 (born between 1975 – 1986, 1960 – 1974, and 1945 – 1959, respectively). These age groups were selected in order to be consistent with previous analyses using this same data set and participants (Kertzner, Meyer, Frost & Stirratt, 2009), and are in line with the sociologically relevant birth generations considered in Calzo, Antonucci, Mays, and Cochran (2011). Each of these categories represent a broad range of life experiences and developmental trajectories influenced by LGB history timelines (Cook-Daniels, 2008). Additionally, at the time of the study the categories approximated periods of: postadolescent entry into and exploration of the LGB community (18–29); the greater assumption of social roles related to partnership, child-care responsibilities, work, or community activities in adulthood (ages 30–44); and the deepening or broadening commitment of these roles in midlife, particularly as they relate to the wellbeing of future generations (45–59).

Respondents were asked to select which of three race/ethnicity options (“White, “ “Black/African American,” or “Latino, Hispanic, or Spanish Origin”) best described their racial or ethnic background. Participants could identify their race/ethnicity using other terms, which were recoded into these three categories for the purpose of aggregating analysis (e.g. “Dominican” was coded as Latino). People of other or mixed racial/ethnic backgrounds were not eligible.

Respondents were asked to state the sexual identity label they used to describe themselves. For the purposes of this study, we examined those who identified as “gay,” “lesbian,” or “bisexual.” A small number of participants (n=36) who used a different label to refer to same-sex-oriented identity (e.g. “homosexual,” or “queer”) were coded as “gay” or “lesbian” according to their gender. Only those who identified as “bisexual” were included in the bisexual group. When comparing sexual identities, our primary interest was to understand how bisexual identity is distinguishable from same-sex identity. We thus compared gay men/lesbians as one group with bisexuals as the comparison group. Gender, which was compared in separate analyses, was not a factor in our comparisons of same-sex and bisexual identities.

We did not include demographic variables about income, education level, relationship status, or religion because these variables reflected participants’ experiences at the time of the interview, not at the time of their coming out. Future research would benefit from asking about these characteristics at the time of respondents’ coming out process.

Analysis

T-tests were performed to describe differences in the mean ages of sexual identity milestones, disclosure milestones, and the time between milestones by gender and sexual orientation. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to describe the same differences by age cohort and race/ethnicity, as well as to identify potential interactions between variables. Chi-Squared tests were performed to determine differences in the proportion of disclosure by group. A multivariate analysis was conducted using dummy variables for each sub-population identity to control for potential confounding. For all analyses, disclosure to family, other LGB individuals, and heterosexual friends were dichotomized to groups of “No disclosure” versus “Any disclosure.” In order to determine if the disclosure milestones are biased by a lack of participant disclosure, we provide a disclosure percent for all subgroups, indicating what proportion of the subgroup has disclosed to at least one family member, straight friend, or other LGB individual. Statistical analyses were completed using STATA 12.0 (College Station, TX).

Results

Results for the t-tests and ANOVAs of gender, age cohort, race/ethnicity, and sexual identity on development milestones are presented in Table 2. All of the figures highlighted below are statistically significant at the .05 level (statistics are reported in Table 2).

Table 2.

Age of sexual identity milestones, disclosure milestones, and the time between milestones by race/ethnicity, gender, age cohort, and sexual identity (N=396)

| Total | Male | Female | Gay/Lesbian | Bisexual | Age 18–29 |

Age 30–44 |

Age 45–59 |

White | Black | Latino | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 396 (100%) |

n = 198 (50%) |

n = 198 (50%) |

n = 325 (82%) |

n = 71 (18%) |

n = 176 (44%) |

n = 174 (44%) |

n = 46 (12%) |

n = 134 (34%) |

n = 131 (33%) |

n = 131 (33%) |

||

| Age of first same-sex… (mean age [SD]) | ||||||||||||

| Attraction | 11.32 (4.83) |

10.86 (4.71) |

11.79 (4.90) |

10.86 (4.48) |

13.49 (5.72)* |

11.44 (4.09) |

11.51 (5.58) |

10.17 (4.19) |

11.29 (4.28) |

11.74 (5.16) |

10.95 (5.01) |

|

| Self-identification | 16.17 (6.23) |

14.77 (6.12) |

17.58 (6.04)* |

15.34 (5.94) |

19.96 (6.16)* |

15.28 (4.58) |

17.11 (7.18) |

16.02 (7.34)* |

15.94 (4.74) |

16.82 (6.25) |

15.76 (7.43) |

|

| Intimate relationship |

18.37 (6.35) |

17.65 (6.37) |

19.09 (6.26)* |

18.25 (5.48) |

18.94 (9.42) |

16.55 (5.26) |

19.48 (6.34) |

21.17 (8.13)* |

18.81 (5.71) |

18.48 (6.09) |

17.81 (7.18) |

|

| Disclosure (%) | ||||||||||||

| Family | 90 | 89 | 90 | 93 | 76* | 89 | 91 | 91 | 94 | 88 | 88 | |

| Other LGB individuals |

100 | 99 | 100 | 100 | 99* | 100 | 99 | 100 | 100 | 99 | 100 | |

| Straight friend | 94 | 92 | 96 | 96 | 86* | 94 | 93 | 98 | 99 | 93 | 91* | |

| Age of first disclosure to… (mean age [SD]) | ||||||||||||

| Family | 21.16 (6.08) |

20.71 (5.74) |

21.60 (6.38) |

20.98 (6.11) |

22.20 (5.87) |

18.41 (3.36) |

22.92 (5.81) |

25.18 (9.80)* |

20.99 (5.51) |

21.09 (5.88) |

21.42 (6.91) |

|

| Other LGB individuals |

19.68 (5.21) |

19.15 (4.57) |

20.21 (5.74)* |

19.21 (4.91) |

21.84 (6.01)* |

17.52 (3.10) |

21.05 (5.19) |

23 (7.80)* |

19.20 (4.03) |

20.06 (5.30) |

19.8 (6.13) |

|

| Straight friend | 20.45 (5.76) |

20.22 (5.77) |

20.68 (5.76) |

20.08 (5.66) |

22.33 (5.96)* |

18.04 (3.29) |

21.74 (5.47) |

24.98 (9.08)* |

19.68 (4.94) |

21.02 (6.05) |

20.73 (6.25) |

|

| Time between… (mean age [SD]) | ||||||||||||

| Attraction and self-identification |

4.85 (6.09) |

3.89 (6.17) |

5.81 (6.09)* |

4.49 (5.57) |

6.53 (7.88)* |

3.83 (4.40) |

5.60 (6.91) |

5.85 (7.63)* |

4.65 (4.92) |

5.09 (5.87) |

4.82 (7.29) |

|

| Attraction and intimate relationship |

7.06 (7.39) |

6.83 (7.70) |

7.29 (7.09) |

7.42 (6.27) |

5.38 (11.16)* |

5.08 (6.74) |

8.01 (7.20) |

11 (8.31)* |

7.51 (6.45) |

6.81 (7.66) |

6.84 (8.05) |

|

| Self-identification and family disclosure |

5.12 (6.28) |

5.97 (5.84) |

4.27 (6.60)* |

5.52 (6.37) |

2.78 (1.33)* |

3.08 (3.72) |

5.88 (5.93) |

10.15 (10.79)* |

4.90 (6.05) |

4.51 (6.14) |

5.99 (6.64) |

|

| Self-identification and LGB disclosure |

3.45 (5.21) |

4.38 (5.11) |

2.53 (5.16)* |

3.78 (5.36) |

1.94 (4.16)* |

2.23 (3.65) |

3.78 (4.98) |

6.96 (8.48)* |

3.26 (4.95) |

3.29 (4.92) |

3.82 (5.76) |

|

| Self-identification and straight disclosure |

4.53 (6.19) |

5.74 (6.37) |

3.31 (5.77)* |

4.83 (6.40) |

3.02 (4.73)* |

2.80 (4.30) |

5.12 (5.95) |

8.91 (9.68)* |

3.71 (5.58) |

4.71 (6.56) |

5.27 (6.40) |

|

Subgroup differences significant at p < 0.05

Sexual Identity Milestones

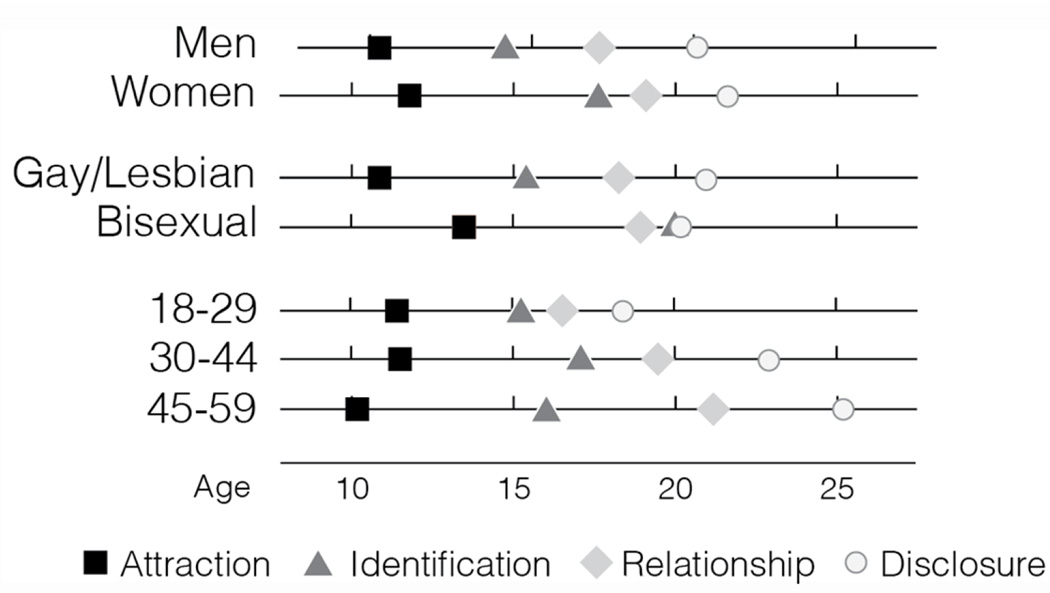

Sexual identity milestones differed by gender, sexual identity, and age cohort (Table 2 and Figure 1). Women self-identified as non-heterosexual when they were almost 3 years older than the men (age 17.6 vs. 14.8) and reported their first same-sex relationship when they were 1.4 years older than men (19.1 vs. 17.7). Bisexual identity was the most influential characteristic on age of first same-sex attraction. Bisexuals self-identified as non-heterosexual at an older age than gay men and lesbians (20 vs. 15.3). Additionally, they reported their first same-sex attraction when they were nearly 3 years older than the gay men/lesbians (13.5 vs. 10.9)—more than twice the difference in the average age of first same-sex attraction between men and women, age cohorts or racial/ethnic groups.

Figure 1.

Coming out milestones among LGB respondents by gender, identity, and age cohort

Note: Attraction = mean age of first same-sex attraction; Identification = mean age of first self-identification as LGB (or similar identity label); Relationship = mean age of first same-sex intimate relationship; Disclosure = mean age of first disclosure to of their family of origin.

Differences among age cohorts were also prominent. LGBs in the youngest cohort (ages 18 – 29) experienced their first same-sex intimate relationship 4.6 years younger than members of the middle age cohort, and 1.7 years younger than LGBs in the middle cohort (16.6 vs. 19.5, vs. 21.2, respectively). Members of the youngest cohort also self-identified as non-heterosexual at the youngest age (15.3, vs. 17.1 and 16.0, respectively) but the difference between the younger and older cohort did not reach statistical significance. There were no significant differences in sexual identity milestones by race/ethnicity.

Disclosure Milestones

The proportion of individuals who disclosed their sexual identity differed among subgroups both by the age at which they were experienced, and whether they were experienced at all (that is, if the person has ever disclosed their sexual identity to a family member, LGB, or heterosexual friend). Although overall rates of sexual identity disclosure were high, fewer Black and Latino respondents disclosed to heterosexual friends than White respondents (93%, 91%, 99%, respectively). Compared with gay and lesbian respondents, 17% fewer bisexuals disclosed to a family member and 10% fewer disclosed to a heterosexual friend.

Differences in timing of disclosure were found among gender, age cohort, race/ethnicity, and sexual identity subgroups. Women came out to LGB friends at a later average age than men (20.2 vs. 19.2). Respondents in the youngest cohort disclosed their sexual minority status, on average, to a family member at age 18.4, to LGB friends at age 17.5, and to straight fiends at age 18.0—almost 7 years, 5 years, and 7 years, respectively, earlier than members of the oldest age cohort. Also, bisexuals first disclosed their sexual identity to other LGB and heterosexual friends at a later age than did lesbian and gay respondents (21.8 vs. 19.2 and 22.3 vs. 20.1, respectively).

Time between Milestones

The time between age of first same-sex attraction and first self-identification differed among gender and sexual identity subgroups. Women reported more time between the age of first same-sex attraction and self-identification than men (6 years vs. 4 years). Similarly, bisexuals experienced more time than gays/lesbians between the age of first same-sex attraction and self-identification (6.5 years vs. 4.5).

The time between first same-sex attraction and first same-sex intimate relationship was significantly different for age cohort and sexual identity subgroups. LGBs in the youngest age cohort waited fewer years between recognizing their same-sex attraction and being in their first same-sex intimate relationship compared with the middle and oldest cohorts (mean lengths of wait were approximately 5, 8, and 11 years, respectively). Gay men and lesbians became aware of their attraction to members of the same sex earlier than bisexuals but they took over two years longer than bisexuals between the age of their first same-sex attraction and their first same-sex intimate relationship (5 years vs. 7 years). There were no differences among the other subgroups of the population in the time between these milestones.

The time between first self-identification as a sexual minority and first disclosure to a family member, varied by gender and sexual identity. Although, as mentioned above, women took more time to self-identify after their first same-sex attraction, men took longer to disclose their sexual identity after self-identification, across all disclosure groups (6 vs. 4 years for family disclosure, 4.4 vs. 2.5 years for LGB disclosure, and 5.7 vs. 3.3 years for heterosexual disclosure). Looking at sexual identity, although bisexuals experienced more time between their first same-sex attraction and their first self-identification, gays and lesbians took longer between first identifying as a sexual minority and disclosing that identity to any of the disclosure groups (5.5 vs. 2.8 years for family disclosure, 3.8 vs. 1.9 years for LGB disclosure, and 4.8 vs. 3 years for heterosexual disclosure).

Including all sub-population groups into a single multivariate regression did little to alter the findings. After controlling for the other identity variables there was no longer a statistically significant difference between men and women in the age of first disclosure to another LGB individual. No other significant changes were observed in the other gender comparisons or across all other identity categories (data not shown).

Discussion

Consistent with our first hypothesis, there were pronounced gender differences in sexual identity and disclosure milestones. Men, whether gay or bisexual, experienced most sexual identity milestones earlier than women, but they tended to take more time between milestones. Lytoon & Romney’s (1991) meta-analysis of the parental socialization of boys and girls offers one explanation why men may experience sexual identity milestones earlier than women. Findings suggest that parents view and respond to gender atypicality more negatively for boys than for girls, which could lead boys to process feelings of difference at an earlier age. Our data similarly suggests that although men may be aware of their sexuality at younger ages, women tend to be able to process through sexual identity milestones more quickly. It is also possible that becoming aware of one’s sexuality at an older age, when a person has achieved greater maturity and independence, accelerates the coming out processes. Additionally, it is plausible that women perceive less risk associated with a sexual minority identity or a broader range of socially acceptable gender and sexual expressions than men (D’Augelli, Grossman, & Starks, 2008).

Findings supported our second hypothesis that younger cohorts of sexual minorities had a shorter time between milestones than older cohorts, and partially supported our hypothesis that sexual identity and disclosure milestones occurred at a younger age among younger cohort LGBs. LGBs in the youngest cohort became aware of their same-sex attraction at about the same age as the older cohorts (around 11 years of age). Despite this shared starting point, LGBs in younger age cohorts experienced other sexual identity milestones (first intimate relationship and first self-identification) and all disclosure milestones earlier than the older cohorts. It is notable that LGBs in older cohorts disclosed their sexual identity when they were in their early-to-mid 20s, when they were more likely to live independently from their families and to be out of high school, whereas LGBs in the youngest cohort disclosed their sexual identity to others when they were around 17 and 18, when they were less likely to be independent of parents and out of high school (D’Augelli, Hershberger, Pilkington, 1998; Kertzner, Meyer, Frost, & Stirratt, 2009; Morgan, 2013).

In addition to experiencing milestones earlier, LGBs in younger cohorts took less time than LGBs in older cohorts between milestones. This is consistent with previous findings by Parks and Hughes (2007). One explanation for this is that the increasing social acceptability of LGB individuals has led to LGB youth to experience these milestones at ages on par with the age that their heterosexual counterparts begin exploring their sexuality rather than delay them for fear of rejection, discrimination, and violence (Baunach, 2012; Graber & Archibald, 2001).

The third hypothesis, that there would be no differences among racial/ethnic groups, was also supported. Whites, Blacks, and Latinos were similar in sexual identity milestones, disclosure milestones, and time between milestones. The only difference noted was that fewer Black and Latino than White respondents disclosed their sexual identity to heterosexual friends—something that was also found by Dube and Savin-Williams (1999). These findings are consistent with studies showing limited differences in sexual identity development between racial/ethnic groups (Grov, Bimbi, Nanin, & Parsons, 2006; Rosario, Schrimshaw, & Hunter, 2004).

Our fourth hypothesis, that bisexual people experience sexual identity and disclosure milestones later than gay and lesbian people, was supported. Bisexuals became aware of their same-sex attraction at a much later age than gay men and lesbians—the difference in age of first same-sex of attraction between bisexuals and gays/lesbians was more than twice the difference between men and women, age cohorts or racial/ethnic groups in the same measure. However, although they began the coming out process at a later age, the mean time between self-identification and disclosure was consistently shorter for bisexuals when compared with gay men and lesbians. It is possible that their opposite-sex attraction delays the recognition and significance of bisexuals’ same-sex attractions and allowed them to explore their sexuality with less fear of rejection or discrimination (Maguen, Floyd, Bakeman & Armistead, 2002).

Interestingly, while disclosure to LGB and heterosexual friends differed by gender, age cohort, race/ethnicity, and sexual identity, disclosure to a family member was only significantly different for the oldest cohort, suggesting that this is a coming out milestone not strongly affected by subgroup identity characteristics.

Study Limitations

Limitations of this study should be noted. The data used in this study were collected in 2005 from people who were then between the ages of 18–59. The youngest cohort reported experiencing all coming out milestones consistently earlier than the middle and oldest cohorts. If this trend has continued, as research suggests that it has (Floyd & Bakeman, 2006; Grov, Bimbi, Nanin & Parsons, 2010; Rosario, Schrimshaw, Hunter & Braun, 2006), young adults today may already experience different trajectories of coming out milestones than those found in this study. Also, because this study took place in New York City, the results may not be representative of the experience of sexual minority people across the United States. Sexual identity development is an individual process influenced by sociocultural factors (Shapiro, Rios, & Stewart, 2010). The large variability in social and political climate by geographic location may be an important factor in sexual identity development. That said, many New York City residents have come of age outside the city and migrated there (Egan et al., 2011), thus, the sample may represent more varied experiences than that of New York City natives. As we indicated above, the study is limited by the retrospective data in that we do not have information on a range of socio-cultural and socio-economic factors at the time that our respondents have gone through these coming out milestones.

Lastly, though the purpose of our analyses was to demonstrate the variability that exists within the LGB population, we nonetheless aggregated several subgroups using umbrella categories that are themselves quite diverse. For example, by treating White, Black, and Latino participants as three distinct categories these analyses are unable to recognize the overlap between the groups (such as Latinos who could identify as racially White or Black) in addition to the nuanced differences within subpopulations of the same group (such as comparisons between Latinos with different national origins). Similarly, the categorization of participants as lesbian, gay, or bisexual neglects the fluidity of sexuality. As a cross-sectional analysis this study was unable to address how this fluidity influences sexual identity development.

Implications for Future Research

Given the evidence that younger cohorts are experiencing sexual identity milestones at progressively younger ages, it is important for scholars to continue to study the identity development trajectories of sexual minority youth. It will be especially important to observe how coming out during adolescence, versus coming out in emerging adulthood—where youth are under less influence from parents, and schools, and have more legal rights—will affect the physical and mental health outcomes of LGB people.

These findings should be used to strengthen research on LGBT health disparities by encouraging researchers to consider the impact of coming out milestones among sexual minority subgroups. For example, bisexual people have been found to have higher odds of suicidal ideation and attempts than gay men and lesbians (Saewyc et al. 2008). In our study, we found that bisexual experienced a greater time between the age of first awareness of same-sex attraction and the age of first self-identification than gay and lesbian respondents. Studies are needed to characterize the processes through which individuals move among the coming out milestones. For example, if a greater time between milestones is indicative of internal conflict, researchers may benefit from examining sexual identity milestones by identity subgroup to partially explain the increased odds of suicidal ideation and attempts.

Health interventions should consider how sexual identity milestones, especially those associated with the early onset of psychosocial health problems, may influence health outcomes among different subgroups. For example, Parks and Hughes (2007) show that higher rates of alcohol use among lesbian and bisexual women are associated with time between realization and disclosure milestones, and the degree of disclosure to family members, which could inform prevention and treatment programs. Studies have also found dramatically higher smoking rates among sexual minority teen girls, and slightly higher rates among sexual minority teen boys, when compared to heterosexual teens (ALA, 2008). Understanding the ages at which teens process their sexual identity development could offer alcohol and smoking prevention campaigns a series of points to incorporate relevant and affirming messages for LGB youth.

As researchers continue to study the “exploration of sexual/gender identity among youth” (HHS, 2013), it is important for them to consider how differences by gender, age, and race/ethnicity can impact the health of sexual minorities. By understanding how subgroups of the LGB population vary in their sexual identity development, health professions can design and implement more effective interventions for sexual minority youth.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Laura Durso, PhD for comments on an early version of this manuscript. This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health grant R01-MH066058 to Dr. Ilan H. Meyer.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) Standard definitions: Final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys. Deerfield, IL: 2005. Retrieved from: http://www.aapor.org/pdfs/standarddefs_3.1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Smoking out a deadly threat: Tobacco use in the LGBT community. Washington DC: 2008. American Lung Association (ALA) Retrieved from: http://www.lung.org/assets/documents/publications/lung-disease-data/lgbt-report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Baunach M. Changing same-sex marriage attitudes in America from 1988 through 2010. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2012;76(2):364–378. [Google Scholar]

- Calzo JP, Antonucci TC, Mays VM, Cochran SD. Retrospective recall of sexual orientation identity development among gay, lesbian, and bisexual adults. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47(6):1658–1673. doi: 10.1037/a0025508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cass VC. Homosexual identity formation: A theoretical model. Journal of Homosexuality. 1979;4(3):219–235. doi: 10.1300/J082v04n03_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2007–2010. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2012;17(4) Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/#supplemental. [Google Scholar]

- Cook-Daniels L. Living memory GLBT history timeline: current elders would have been this old when these events happened…. Journal of GLBT Family Studies. 2008;4(4):485–497. [Google Scholar]

- Cox S, Gallois C. Gay and lesbian identity development. Journal of Homosexuality. 1996;30(4):1–30. doi: 10.1300/J082v30n04_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Grossman AH. Disclosure of sexual orientation, victimization, and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16(10):1008–1027. [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Grossman AH, Starks MT. Gender atypicality and sexual orientation development among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: Prevalence, sex differences, and parental responses. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Psychotherapy. 2008;12(1–2):121–143. [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Hershberger SL, Pilkington NW. Lesbian, gay and bisexual youth and their families: Disclosure of sexual orientation and its consequences. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68(3):361–371. doi: 10.1037/h0080345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube EM, Savin-Williams RC. Sexual identity development among ethnic sexual-minority male youths. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35(6):1389–1398. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.6.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan JE, Frye V, Kurtz SP, Latkin C, Chen M, Tobin K, Koblin BA. Migration, neighborhoods, and networks: Approaches to understanding how urban environmental conditions affect syndemic adverse health outcomes among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15(1):35–50. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9902-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd FJ, Bakeman R. Coming-out across the life course: Implications of age and historical context. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2006;35(3):287–296. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd FJ, Stein TS. Sexual orientation identity formation among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: Multiple patterns of milestone experiences. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2002;12(2):167–191. [Google Scholar]

- Galambos NL, Almeida DM, Petersen AC. Masculinity, femininity, and sex role attitudes in early adolescence: Exploring gender intensification. Child Development. 1990;61(6):1905–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates GJ. Sexual minorities in the 2008 General Social Survey: Coming out and demographic characteristics. Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Graber JA, Archibald AB. Psychosocial change at puberty and beyond: Understanding adolescent sexuality and sexual orientation. In: D’Augelli AR, Patterson CJ, editors. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual identities and youth—Psychological perspectives. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Grov C, Bimbi DS, Nanín JE, Parsons JT. Race, ethnicity, gender, and generational factors associated with the coming out process among gay, lesbian, and bisexual individuals. Journal of Sex Research. 2006;43(2):115–121. doi: 10.1080/00224490609552306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertzner RM, Meyer IH, Frost DM, Stirratt MJ. Social and psychological well-being in lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals: The effects of race, gender, age, and sexual identity. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79(4):500–510. doi: 10.1037/a0016848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytton H, Romney DM. Parents’ differential socialization of boys and girls: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;109(2):267–296. [Google Scholar]

- Maguen S, Floyd FJ, Bakeman R, Armistead L. Developmental milestones and disclosure of sexual orientation among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths. Applied Developmental Psychology. 2002;23(2):219–233. [Google Scholar]

- Martin JL, Dean L. Summary of measures: Mental health effects of AIDS on at-risk homosexual men. Reference type: Unpublished work. 1987 [Google Scholar]

- Morgan EM. Contemporary issues in sexual orientation and identity development in emerging adulthood. Emerging Adulthood. 2013;1(1):52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Parks CA. Bicultural competence: A mediating factor affecting alcohol use practices and problems among lesbian social drinkers. Journal of Drug Issues. 1999;29(1):135–154. [Google Scholar]

- Parks CA, Hughes TL. Age differences in lesbian identity development and drinking. Substance Use & Misuse. 2007;42(2–3):361–380. doi: 10.1080/10826080601142097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdie-Vaughns V, Eibach RP. Intersectional Invisibility: The Distinctive Advantages and Disadvantages of Multiple Subordinate-Group Identities. Sex Roles. 2008;59(5–6):377–391. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson R, Plan I. HIV / AIDS inequality: Structural barriers to prevention, treatment, and care in communities of color. Washington, D.C: Center for American Progress; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Ethnic/racial differences in the coming-out process of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: A comparison of sexual identity development over time. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2004;10(3):215–228. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. A model of sexual risk behaviors among young gay and bisexual men: Longitudinal associations of mental health, substance abuse, sexual abuse, and the coming-out process. AIDS Education and Prevention: Official Publication of the International Society for AIDS Education. 2006;18(5):444–460. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.5.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Different patterns of sexual identity development over time: Implications for the psychological adjustment of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. Journal of Sex Research. 2011;48(1):3–15. doi: 10.1080/00224490903331067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saewyc EM, Skay CL, Hyndes P, Pettingel S, Bearinger LH, Resnick MD, Reis E. Suicidal ideation and attempts in North American school-based surveys: Are bisexual youth at increased risk? Journal of LGBT Health Research. 2008;3(2):25–36. doi: 10.1300/J463v03n02_04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC, Diamond LM. Sexual identity trajectories among sexual minority youths: Gender comparisons. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2000;29(6):607–627. doi: 10.1023/a:1002058505138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro DN, Rios D, Stewart AJ. Conceptualizing lesbian sexual identity development: Narrative accounts of socializing structures and individual decisions and actions. Feminism & Psychology. 2010;20(4):491–510. [Google Scholar]

- Troiden DRR. The formation of homosexual identities. Journal of Homosexuality. 1989;17(1–2):43–74. doi: 10.1300/J082v17n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health. 2013 Retrieved from: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=25.