Abstract

Apoptosis and inflammatory processes may be at the basis of reducing graft survival. Erythropoietin is a tissue-protective hormone with pleiotropic potential, and it interferes with the activities of pro-inflammatory cytokines and stimulates healing following injury, preventing destruction of tissue surrounding the injury site. It may represent a useful tool to increase the autograft integration. Through the use of multipanel kit cytokine analysis we have detected the cytokines secreted by human tissue adipose mass seeded in culture following withdrawal by Coleman’s modified technique in three groups: control, after lipopolysaccharides stimulation and after erythropoietin stimulation. In the control group, we have observed expression of factors that may have a role in protecting the tissue homeostatic mechanism. But the same factors were secreted following stimulation with lipopolysaccharides combined with others factors that delineated the inflammatory state. Instead through erythropoietin stimulation, the factors known to exert tissue-protective action were secreted. Therefore, the use of a trophic factors such as erythropoietin may help to inhibit the potential inflammatory process development and stimulate the activation of reparative/regenerative process in the tissue graft.

Keywords: Autograft, inflammation, leptin, chemokines

Introduction

Several studies evidenced the important role of vascularization in supporting the survival of free fat graft.1,2 However recently, the significance of inflammatory cytokines was observed as mediators of free fat cells’ survival and integration.3,4 In particular, the interaction between vascularization and inflammatory cytokines may be fundamental for free fat cells’ survival and functionality. The latter is of particular importance when autologous fat grafting is performed for regenerative purpose.

An interesting finding described by Hamed et al.5 is that a trophic stimulation for free fat cells’ functional activation should have origin inside the free fat cells due to the fact that factors administered externally failed to reach their effects. These findings lead us to hypothesize that free fat cells are a complex milieu in which cytokine balance is essential for the therapeutic results of autograft.

The use of adipose tissue mass to support regenerative medicine imply the release of cytokine that can initiate the restoring tissue functionality, known that in several tissue districts the alteration of signalling factors is at the basis of an impaired organ healing.6,7

Following these findings, a lot of studies have focussed their attention on the properties of adipose-derived stem cells (ASC) to secrete several cytokines as important event to promote tissue healing.8 Indeed, also other adipose tissue-resident cells such as macrophages and lymphocytic cells are able to produce cytokines.9 These findings suggest that free fat cells may represent a trophic milieu in which the different cell types of the adipose depots participate by cytokine secretion to perform trophic/regenerative effects.

In a previous work, we have observed that free fat cells used for refilling is sensible to erythropoietin (EPO) administration.10 EPO is a glycoprotein hormone that was first characterized by its ability to stimulate erythropoiesis. EPO has also the ability to affect immunological mechanisms.11 Dendritic cells, which initiate the immune response, are targets of the immunomodulatory function of EPO,12 macrophages are also influenced by EPO.13 Katz et al.14 have also reported that EPO has anti-inflammatory effects in different animal models, decreasing apoptosis and reducing the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

The paper of Hamed et al.5 is the first article reporting the effect of EPO on human free fat grafting. This article well describes the effect of EPO on inflammation after fat grafting as one of the mechanisms by EPO to enhance graft attachment in the receiving site.

In conclusion, EPO can be considered as a tissue-protective hormone with pleiotropic potential, it interferes with the activities of pro-inflammatory cytokines and stimulates healing following injury, preventing the tissue destruction surrounding the injury site.11

The aim of this work is to identify the potentiality of the human free fat grafts to react as trophic/reparative support. For this purpose, the cytokine profile expressed following inflammatory stimulus such as the bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS) have been analysed and compared with the cytokine profile expressed following EPO administration.

Materials and methods

Isolation and preparation of human fat tissue

Fat graft was harvested using manual suction lipectomy through a 14-gauge blunt cannula, under general anaesthesia, from abdomen areas of 8 women during procedures of reconstructive surgery. The over-exceeding free fat cells, not used for refilling and destined to disposal, were used in our study. Therefore, no ethical committee was required to authorize the study. All participants gave their written informed consent. The patients were 42 ± 4 years old. In order to decrease bleeding during fat aspiration and to relieve pain after the procedure, the aspiration areas were injected with a local anaesthesia solution containing lidocaine (0.5%) and adrenaline (1:1,000,000) before the fat graft aspiration. From each of the eight patients, more than 100 mL of adipose mass was aspirated and centrifuged for 2 min at 1500 r/min according to Coleman’s modified procedure.10 The upper fraction representing oil and cellular fragments together with the lower fraction representing the plasma and local anaesthetic were separated from the central fraction consisting of adipose mass; the latter was used in the study. Lipoaspirate-Coleman (1 mL) corresponding to 1.00 ± 0.04 g of tissue was cultured in 2 mL of X-VIVO 15 medium (Lonza) in a CO2 incubator at 5% CO2, 37°C for 48 h. From each sample three experimental groups were prepared: EPO-treated group, 48 h of treatment in culture media with 0.60 µg/mL of EPO (EPREX, Janssen-Cilag, Milan, Italy); LPS-treated group, 48 h of treatment in culture media with LPS 100 ng/mL (Sigma), used as positive inflammatory control; control group, without any treatment used as negative control.

Cytokine release

The cytokines release was assessed using a sandwich ELISA kit that enables perceiving and semi-quantifying the proteins released (Mouse Cytokine Antibody Array-Panomics; Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Briefly, the media of lipoaspirate-Coleman cultured with or without EPO and LPS were incubated on array membranes containing linked antibodies. In this way, specific cytokine proteins are being immobilized. Then a detection biotin-conjugated antibody binds to a second epitope on the protein, creating an antibody ‘sandwich’ around the cytokine. After streptavidin-HRP incubation, membranes were analysed using a VersaDoc Imaging System Model 3000 (BioRad). A semi-quantitative analysis was performed detecting positive spot as fold increase compared to negative control by VersaDoc. Then, instrumental data were normalized for the optical fundus, converted and reported as % of optical density (%OD).

Data analysis

The Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistical test was used for the assessment of data normal distribution. Statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance, the Newman–Keuls post hoc comparison tests were used to test significance between experimental groups. The significance level was set at p < 0.05. All statistical tests were performed by the statistical software program Prism 2.01 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

The several cytokines analysed were classified according to their activities in five groups as shown in Table 1: ‘pro-inflammatory’, ‘anti-inflammatory’, ‘chemokines’, ‘growth factors’ and ‘other’.

Table 1.

Grouped list of several factor detected in supernatants of fat mass cultures.

| Pro-inflammatory | Anti-inflammatory | Chemokines | Growth factors | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTLA | IL-4 | Eotaxin | EGF | Apo/Fas |

| IFN-γ | IL-5 | IL-8 | GM-CSF | Leptin |

| IL-1α | IL-6 | IP-10 | IL-3 | MMP-3 |

| IL-1β | IL-10 | MIP-1α | IL-7 | |

| IL-2 | IL-6R | MIP-1β | VEGF | |

| IL-12(p40) | TGF-β | MIP-4 | ||

| IL-15 | IL-1Ra | MIP-5 | ||

| IL-17 | RANTES | |||

| ICAM-1 | ||||

| VCAM-1 | ||||

| TNF-α | ||||

| TNFRI | ||||

| TNFRII |

Apo/Fas: apoptosis antigen-1/Fas; CTLA: cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen; IL: interleukin; EGF: epidermal growth factor; IFN-γ: interferon-γ; GM-CSF: granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; IP-10: induced protein-10; MMP: matrix metalloproteinase; MIP: macrophage inflammatory protein; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; TGF-β: transforming growth factor-β; RANTES: regulated on activation normal T cells expressed and secreted; ICAM-1: intracellular adhesion molecule-1; VCAM-1: vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; TNF-α: tumour necrosis factor-α; TNFRI: tumour necrosis factor receptor 1; TNFRII: tumour necrosis factor receptor II.

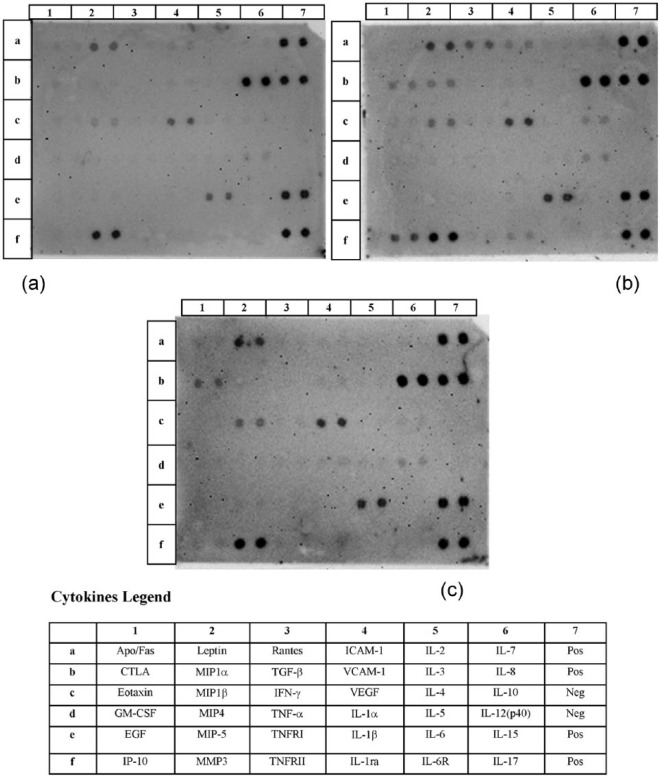

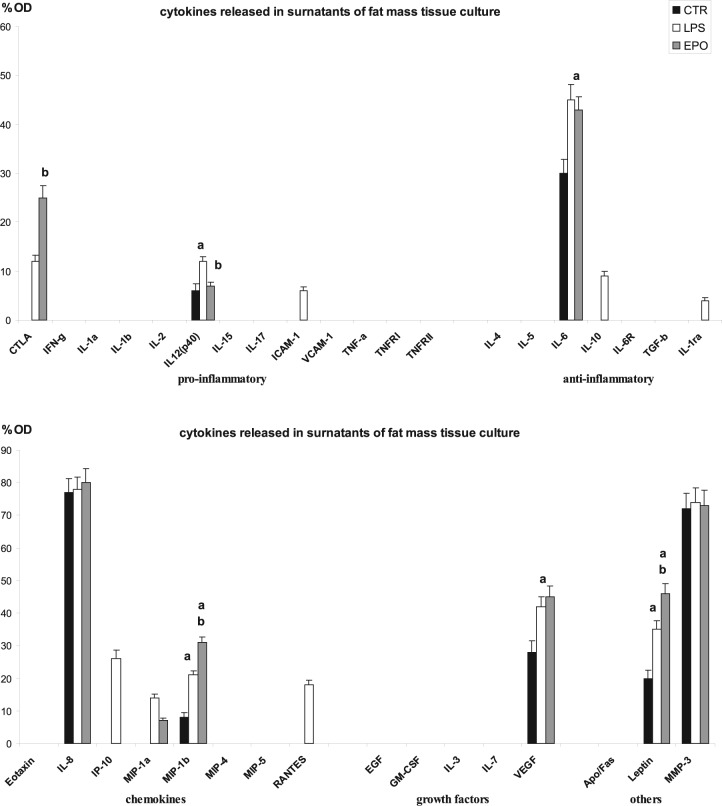

In the adipose mass of the control untreated group, we have observed that the pro-inflammatory factors were not expressed, with the only exception of limited levels of interleukin (IL)-12(p40), while anti-inflammatory factors and chemokines were represented, respectively, by IL-6, IL-8 and macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1β. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) was the only growth factor detected in control free fat cells. In particular, in the control group, we have detected high levels of leptin, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-3, VEGF, IL-6 and IL-8. IL-8 was the highest expressed IL instead of MIP-1β and IL-12(p40) that were detected in lower levels (Figures 1(a) and 2).

Figure 1.

Image showing the multitest to detecting cytokines released on surnatant of free fat cells culture following 48 h. (a) control group, (b) LPS-treated group and (c) EPO-treated group. The table shows the legend of paired dot spot visible or not visible on membranes.

Figure 2.

Bar graphs showing the results of semi-quantitative analysis of visible dot spot.

CTR: control group; LPS: LPS-treated group; EPO: EPO-treated group. ap < 0.05 versus CTR-group, bp < 0.05 versus LPS-group.

Cultured lipoaspirate resulted to be vital and active, in fact it demonstrates to modify the pattern of cytokines released when stimulated with LPS, used as pro-inflammatory factor (Figure 1(b)). When the cytokine pattern was compared to the control untreated one, considered the basal secretor activity, we have detected a significant increase of IL-12(p40), IL-6, MIP-1β, VEGF and leptin, while IL-8 and MMP-3 did not rise. The analysis of the group of the pro-inflammatory factors revealed that an increase in IL-12(p40) along with cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen (CTLA) and intracellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 was detected; in the group of the anti-inflammatory factors, the same factors observed in the control group were present with the occurrence of further factors such as IL-10 and IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra). The same chemokines observed in the control group were detected after LPS stimulation, with the presence of further chemokines such as interferon gamma-induced protein (IP)-10, MIP-1α and regulated on activation normal T cells expressed and secreted (RANTES). Even in LPS-group, VEGF represented the only growth factors detected, among those tested, whereas leptin and MMP-3 were the ‘other’ factors detected (Figures 1(b) and 2).

The EPO stimulated lipoaspirate (Figure 1(c)), similarly to the control group, released in culture media CTLA, and IL-12(p40) as pro-inflammatory factors; IL-6 as anti-inflammatory factor; whereas chemokines were represented by IL-8, MIP-1α and MIP-1β. Furthermore, in the EPO-group, VEGF represented the only growth factors detected among those tested, whereas leptin and MMP-3 were the factors detected in the group ‘other’ (Figures 1(c) and 2). In particular, EPO stimulation increased the expression of CTLA more than LPS dose without increasing the release of IL-12(p40), which maintains a level similar to control untreated lipoaspirate. The anti-inflammatory interleukin IL-6 and the growth factor VEGF were detected similar to LPS-group and therefore increased, in comparison to levels detected in the control group. Among chemokines, IL-8 resulted unmodified in comparison to control and LPS- group, whereas MIP-1β and leptin were further increased with respect to LPS-group. No variation in the quantity of MMP-3 was observed comparing EPO, control and LPS-group (Figures 1 and 2).

Discussion

The most recent acquisition of the inflammatory processes and the discovery of the occurrence of numerous factors involved in cell recruitment and/or activation signalling have gained new functions. Therefore, the same factors previously considered as strictly pro-inflammatory are also been considered protective and reparative factors.15 Therefore, the occurrence of factors secreted in a remodelling tissue need to be analysed inside the pool of factors with which they operate.

We have observed that the free fat cells, following withdrawal, released several factors involved in immunomodulatory processes such as IL-6, IL-8, IL-12(p40) and MIP-1β, but it also releases factors active in reparative/regenerative pathways such as MMP-3, VEGF and Leptin. Even if factors such as IL-6, IL-8, IL-12(p40) and MIP-1β are recognized as pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, for some of these factors, such as IL-6, IL-8 and MIP-1β an exclusive pro-inflammatory role has been recently questioned.15–18 Trujillo et al.19 have observed that cultures of human adipose tissue with IL-6 increased Leptin and lipolysis together with a decrease in lipoprotein lipase activity, suggesting a direct metabolic and physiologic effect performed by this cytokine into adipose tissue.

Otherwise, IL-8 and MIP-1β are cell-attracting chemokines important in recruiting immune cells such as macrophages (in particular MIP-1β) and lymphocytes. Indeed nevertheless the undoubted inflammatory role of these cells, recently their role in reconstructive/reparative pathways has been hypothesized. In fact it has been observed that IL-8 and MIP-1β act also as recruiting neutrophils and natural killer (NK) cells, which represent an important cellular types in performing protective and reparative functions in healing tissues.16,18,20,21 Nevertheless the specific role of MMP-3, VEGF and Leptin, these factors also have shown to be secreted by cells in response to tissue damage.

MMP-3 is an important factor directly secreted by monocytes/macrophages that participate in matrix repairing and remodelling, while the scavenger and protective functions of macrophages are performed.22 VEGF is a well-known factor responsible to ameliorate the perfusion of tissue, secreted by endothelia cells, it is important in organ regeneration and homeostasis, and its secretion increases following tissue stress or injury.23 Leptin is a peptide hormone produced by adipocytes, it has pleiotropic effects exerting its influence on energetic metabolism and psychological behaviour, but it has also been suggested to have a role as paracrine factors inside adipose tissue recovering and sustaining physiological function of adipose tissue.24

Collecting these findings, we hypothesize that human adipose tissue, in form of lipoaspirate, produces specific cytokines in vitro. Implanted lipoaspirate might protect the tissue homeostatic mechanism, probably activating macrophage, fibroblast and lymphocytes that might be resident or could be recruited into the regenerating tissue. Considering that these factors are also active during inflammatory process, they could be responsible of the development inflammatory events or respond modifying their release factors during inflammatory events.

To test this hypothesis, we have administered LPS to cultured lipoaspirate, a well-known inflammation inductor factor. The cultured free fat cells showed the secretion of new factors or the increased release of some observed in the control group. In particular, we have observed the secretion of new cytokines such as CTLA, RANTES, IP-10, MIP-1α, IL-10 and IL-1Ra.

CTLA is a factor responsible for regulating inhibitory signal-activated lymphocytes; it is generally found during the first phase of inflammatory process where it acts as regulatory and homeostatic factor of inflammatory process. RANTES is a known pro-inflammatory cytokine belonging to the group of chemokines that acts by promoting the recruitment and activation of inflammatory cells such as monocytes, lymphocytes, mast cells and eosinophils,25 whereas IP-10 is a chemoattractant for NK cells and T cells and is believed to be an important regulator of the Th1, IL-12-driven, inflammatory response as an inducer of cellular infiltration.15

MIP-1α and MIP-1β are major factors produced by fibroblasts and macrophages after the stimulation with bacterial endotoxin. They are crucial factors for immune responses towards infection and inflammation.26 However, differently from MIP-1β, for MIP-1α a role in reparative functions has not been proven. Therefore, MIP-1α seems to deserve specifically the identity of pro-inflammatory cytokine.

Being LPS an inflammatory stimulus, we demonstrated that lipoaspirate modifies its cytokines pattern during inflammation and some factors such as IL-6, IL-8, IL-12(p40), MIP-1β, MMP-3 and VEGF could have both inflammatory and regenerative effect. In this term, the presence of other factors became determinant to address the action of this group of ambivalent factors. The low expression of well-known anti-inflammatory cytokines such as Il-10 and IL-1Ra can be interpreted as a confirmation of the molecular pathways focussed to perform a balanced inflammatory reaction.

Of interest, the increase in Leptin production following LPS adipose tissue stimulation may be the reflex of the immunomodulatory function on leukocytes observed for this hormone,27 giving Leptin also an identity of an LPS-inducible inflammatory cytokine.

Following the EPO administration, the presence of factors such as CTLA, the high level of MIP-1β and the absence of RANTES induce to hypothesize the occurrence of factors having a role in recovering leukocytes involved in regenerative/reparative functions rather than inflammation. Whereas the presence in this experimental group of MMP-3, VEGF, IL-6 and IL-8 induces to consider this group of factors in term of reparative signals rather than inflammatory signals as previously discussed. Following this hypothesis, we also suggest that the high levels detected for Leptin should indicate its action in terms of regenerative/reparative signals.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the free fat cells’ withdrawal from its natural place (lipoaspirate) and its injection into the receiving site during reconstructive surgery is the basis of a potential development of inflammatory response. This kind of reaction at the receiving site has been considered the main cause for free fat cells’ transplantation failure or unpredictability in volume keeping.3,4 Otherwise, the occurrence of a trophic factors such as EPO may help to inhibit the potential inflammatory process development and stimulate the activation of reparative/regenerative process starting from the same ambivalent factors occurring during the first period of stress.

Perspective for in vivo application of EPO for autologous fat grafting

The paper of Hamed et al.5 is the first article reporting the effect of EPO on human free fat grafting performed on nude mice. In his work, Hamed has observed that treatment of the fat grafts with EPO, in a dose-dependent manner, increased the expression levels of various angiogenic factors, such as VEGF, basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), platelet derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB), MMP-2 and insulin growth factors-1 (IGF-1). The increased expression of these factors was accompanied with an increase in microvascular density. Induction of cell survival factor expression such as protein kinase B (PKB) and the reduction in the fat cell apoptosis extent were also observed. Contemporary, the authors have also observed reduction in the inflammatory response detected by CD68-positive cells. These findings highlighted the importance of EPO treatment in performing angiogenesis in free fat grafting and in increasing the survival of grafted fat cells.

In our work, we confirm and extend this last observation in an in vitro culture of free fat cells, highlighting that EPO administration is able to decrease inflammatory factors and induce the expression of reparative factors. In particular, we have observed the susceptibility of fat cells to inflammatory stimuli and the consequent expression of inflammatory factors that may represent the signals inducing cell apoptosis, microvascular alteration and failure of the fat graft.

Indeed the inflammatory stimulus performed in our in vitro model represents a strong direct stimulus that may be not similar to that happened in vivo system. However, the involved cytokines are the same known to mediate the inflammatory stimulus in tissue. Furthermore, the use of the same materials used during the lipofilling procedure leads us to hypothesize that the observed response could be the same to the one we may obtain in vivo experimental model.

In summary, we hypothesize that the LPS-induced inflammatory factors and the EPO-induced regenerative/reparative factors observed in vitro in our experimental conditions may well reflect what may occur in vivo. Otherwise, the perfusion of the free fat cells in vitro and in vivo is widely different and the EPO administration performed in vitro should be recalibrated to be adapted to in vivo condition to determine the effect of EPO and its application in clinical practice.

Final consideration

Autologous fat grafting is an important procedure in clinical practice, but the problems related to the long-term graft survival and its unpredictability are the most important limit of this technique in the clinical practice. Numerous studies have been carried out to establish a protocol that induces a fat cell selection with the aim of receiving a better response of fat graft28 or to perform technical solution to have a more compliance free fat cells to use in grafting procedure.28,29 Recently, attention was dedicated to drugs or biological factors that could help the surviving and integration of free fat cells. EPO has been shown to be one of the most promising agents.

EPO is a well-known agent that has recently received numerous evidence on its trophic effects on vasculature, cell surviving and, following our evidence, anti-inflammatory protective agent.

EPO is an approved drug, the use of which contemplates subcutaneous injections that can also be done at the receiving site of fat grafting. This occurrence has made easy the repurposing of EPO for the use in autologous fat grafting enhancement. Following the emerging findings on the safety and properties of EPO, it may be of interest to study clinical setting in EPO administration to improve the free fat grafting integration.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jenssen-Cilag for kindly gift of erythropoietin EPREX.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Nishimura T, Hashimoto H, Nakanishi I, et al. Microvascular angiogenesis and apoptosis in the survival of free fat grafts. Laryngoscope 2000; 110: 1333–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eto H, Kato H, Suga H, et al. The fate of adipocytes after nonvascularized fat grafting: evidence of early death and replacement of adipocytes. Plast Reconstr Surg 2012; 129: 1081–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Juge-Aubry CE, Henrichot E, Meier CA. Adipose tissue: a regulator of inflammation. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005; 19: 547–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goldstain DR. Inflammation and transplantation tolerance. Semin Immunopathol 2011; 33: 111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hamed S, Egozi D, Kruchevsky D, et al. Erythropoietin improves the survival of fat tissue after its transplantation in nude mice. PLOS One 2010; 5: e13986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Karin M, Clevers H. Reparative inflammation takes charge of tissue regeneration. Nature 2016; 529: 307–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thieblemont N, Wright HL, Edwards SW, et al. Human neutrophils in auto-immunity. Semin Immunol 2016; 28: 159–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hassan WU, Greiser U, Wang W. Role of adipose-derived stem cells in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen 2014; 22: 313–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chung S, La Point K, Martinez K, et al. Preadipocytes mediate lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation and insulin resistance in primary cultures of newly differentiated human adipocytes. Endocrinology 2006; 147: 5340–5351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sabbatini M, Moalem L, Bosetti M, et al. Effects of erythropoietin on adipose tissue: a possible strategy in refilling. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2015; 3: e338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lombardero M, Kovacs K, Scheithauer BW. Erythropoietin: a hormone with multiple functions. Pathobiology 2011; 78: 41–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lifshitz L, Prutchi-Sagiv S, Avneon M, et al. Non-erythroid activities of erythropoietin: functional effects on murine dendritic cells. Mol Immunol 2009; 46: 713–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lifshitz L, Tabak G, Mittelman M, et al. Macrophages as novel targets for erythropoietin. Haematologica 2010; 95: 1823–1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Katz O, Gil L, Lifshitz L, et al. Erythropoietin enhances immune responses in mice. Eur J Immunol 2007; 37: 1584–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Koniaris LG, Zimmers-Koniaris T, Edward C, et al. Tissue regeneration liver and bile duct injury suggests a role in protein-10 expression in multiple models of cytokine-responsive gene-2/IFN-inducible. J Immunol 2001; 167: 399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sloniecka M, Le Roux S, Zhou Q, et al. Substance P enhances keratocyte migration and neutrophil recruitment through interleukin-8. Mol Pharmacol 2016; 89: 215–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sasaki S, Baba T, Nishimura T, et al. Essential roles of the interaction between cancer cell-derived chemokine, CCL4, and intra-bone CCR5-expressing fibroblasts in breast cancer bone metastasis. Cancer Lett 2016; 378: 23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kitaya K, Nakayama T, Okubo T, et al. Expression of macrophage inflammatory protein-1β in human endometrium: its role in endometrial recruitment of natural killer cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003; 88: 1809–1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Trujillo ME, Sullivan S, Harten I, et al. Interleukin-6 regulates human adipose tissue lipid metabolism and leptin production in vitro. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004; 89: 5577–5582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eckes B, Nischt R, Krieg T. Cell-matrix interactions in dermal repair and scarring. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 2010; 3: 4–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Witte MB, Barbul A. Role of nitric oxide in wound repair. Am J Surg 2002; 183: 406–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maquoi E, Demeulemeester D, Voros G, et al. Enhanced nutritionally induced adipose tissue development in mice with stromelysin-1 gene inactivation. Thromb Haemost 2003; 89: 696–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Elçin YM, Dixit V, Gitnick G. Extensive in vivo angiogenesis following controlled release of human vascular endothelial cell growth factor: implications for tissue engineering and wound healing. Artif Organs 2001; 25: 558–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stern JH, Rutkowski JM, Scherer PE. Adiponectin, leptin and fatty acids in the maintenance of metabolic homeostasis through adipose tissue crosstalk. Cell Metab 2016; 23: 770–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ajuebor MN, Hogaboam CM, Kunkel SL, et al. The chemokine RANTES is a crucial mediator of the progression from acute to chronic colitis in the rat. J Immunol 2001; 166: 552–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Maurer M, Von Stebut E. Macrophages inflammatory protein-1. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2004; 36: 1882–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Naylor C, Petri WA. Leptin regulation of immune responses. Trends Mol Med 2016; 22: 88–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tremolada C, Colombo V, Ventura C. Adipose tissue and mesenchymal stem cells: state of art and Lipogems® technology development. Curr Stem Cell Rep 2016; 2: 304–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nguyen A, Pasyk KA, Bouvier TN, et al. Comparative study of survival of autologous adipose tissue taken and transplanted by different techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg 1990; 85: 378–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]