Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the safety and tolerability of alternate-day fasting (ADF) and to compare changes in weight, body composition, lipids, and insulin sensitivity index (Si) to those produced by a standard weight loss diet, moderate daily caloric restriction (CR).

Methods

Adults with obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2, age 18-55) were randomized to either zero-calorie ADF (n=14) or CR (-400 kcal/day, n=12) for 8 weeks. Outcomes were measured at the end of the 8-week intervention and after 24 weeks of unsupervised follow-up.

Results

No adverse effects were attributed to ADF and 93% completed the 8-week ADF protocol. At 8 weeks, ADF achieved a 376 kcal/day greater energy deficit, however there were no significant between-group differences in change in weight (mean±SE; ADF -8.2±0.9 kg, CR -7.1±1.0 kg), body composition, lipids, or Si. After 24 weeks of unsupervised follow-up, there were no significant differences in weight regain, however changes from baseline in % fat mass and lean mass were more favorable in ADF.

Conclusions

ADF is a safe and tolerable approach to weight loss. ADF produced similar changes in weight, body composition, lipids and Si at 8 weeks and did not appear to increase risk for weight regain 24 weeks after completing the intervention.

Keywords: intermittent fasting, obesity, weight regain, resting metabolic rate, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, energy intake

Introduction

Current guidelines for treatment of overweight and obesity recommend moderate caloric restriction (i.e. 20-30% energy deficit from daily weight maintenance requirements) along with a comprehensive lifestyle intervention [1]. This approach typically produces modest weight loss (5-10%) over a 6-month period [1, 2]. However, the recidivism rate is extremely high [3], and alternative therapeutic options for achieving and maintaining weight loss are needed.

Intermittent fasting (IMF) is an alternative method of reducing energy intake (EI) that is gaining attention as a strategy for weight loss and health benefits [4-9]. Alternate-day fasting (ADF) is a subclass of IMF, which consists of a “fast day” (0-25% of caloric needs) alternating with a “fed day” (ad libitum food consumption). Reviews suggest ADF may reduce diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk [10, 11] and may favorably impact hormones involved in regulation of hunger and satiety [9]. However, an important question that remains unresolved is whether ADF is an effective weight loss strategy.

Short-term studies suggest ADF produces 3-8% reductions in weight over 2-12 weeks in adults with overweight and obesity [12-18]. However, these studies either lacked a control group [12-17] or compared ADF to a no-intervention control [18]. While these studies lay foundation for ADF as a viable weight loss strategy, greater scientific rigor is needed from interventional trials than is found in the current literature [8]. In particular, randomized trials are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of ADF compared to moderate daily CR, the current standard for weight loss.

The primary aim of this pilot study was to evaluate the safety and tolerability of an 8-week zero-calorie ADF intervention. Secondary aims were to assess efficacy of ADF as compared to a standard dietary weight loss intervention (moderate daily caloric restriction, CR) in generating changes in weight, body composition, lipids, and Si as well as to compare risk for weight regain between groups after 24 weeks of unsupervised follow-up. We hypothesized ADF would be safe and tolerable, would produce greater weight loss and more favorable effects on body composition, lipids, and Si as compared to CR, and would not increase risk for weight regain. To explore potential mechanisms contributing to any observed differences, we also measured change in resting metabolic rate (RMR) and selected hormones implicated in the regulation of energy balance (leptin, ghrelin). Fasting has been suggested to improve cognitive function, possibly mediated by brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [19]; BDNF has also been implicated in the regulation of energy balance [20-22]. Thus, changes in BDNF were also assessed.

Methods

The study was conducted at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus (CU-AMC) and approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (COMIRB). Participants were studied between December 2006 and May 2010.

Participants

Volunteers were recruited from CU-AMC and the surrounding community. Respondents who met initial eligibility criteria (18-55 years, BMI ≥30 kg/m2, non-smoker, ≤4.5 kg weight change over past 6 months) were invited to a screening visit. After providing written informed consent, volunteers underwent a medical history and physical exam including blood pressure (BP), heart rate (HR), anthropometric measures (height, weight), 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG), basic metabolic panel (BMP), liver function tests, compete blood count (CBC), uric acid, thyroid stimulating hormone, and lipid panel. Volunteers were excluded if they had diabetes, CVD, uncontrolled hypertension, severe dyslipidemia (or were on lipid lowering therapy), cancer, thyroid disease, seizures, migraines, significant renal, hepatic or gastrointestinal disorders, binge eating disorder, current depression, history of bariatric surgery, or were taking medications known to affect appetite or energy metabolism. Women who were currently pregnant, planning pregnancy, or lactating were also excluded.

Volunteers who passed screening procedures completed a test fast day in the CU-AMC Clinical and Translational Research Center (CTRC). Participants were admitted in the evening and remained fasted with ad libitum access to water, bouillon/stock cube soup, and non-caloric beverages for ∼36 hours. Safety measures (BMP, CBC, ECG) were performed on admission and following the fast. All participants tolerated the fast and were then randomized to either ADF or CR, stratified by sex.

Experimental Design

The study design was an 8-week intervention, followed by 24-weeks of unsupervised follow-up to assess risk for weight regain after completion of the intervention. Participants in both groups were admitted to the CTRC during the first week of the intervention to monitor safety; the subsequent 7 weeks were performed as an outpatient intervention. Participants were asked to maintain their usual level of physical activity (PA) during the 8-week intervention. Upon completion of the 8-week intervention, participants received standardized weight maintenance advice (maintain a low-fat diet, increase PA) but were free to choose whether to continue their respective dietary intervention strategies (CR or ADF). Participants had no contact with study staff during the follow-up period and dietary adherence was not assessed.

Study diets were not designed to produce comparable energy deficits but rather to compare ADF to a standard-of-care weight loss diet (moderate daily CR). It would not have been possible to design the diets to produce an equivalent energy deficit as it was not known what degree of compensation would occur in ADF on fed days (when allowed ad libitum intake). All food during the 8-week intervention was provided by the CTRC metabolic kitchen; participants collected pre-prepared research meals twice weekly. Participants were instructed to return any uneaten food for weigh-back and to report any foods eaten in addition to the research meals. Free-living weight maintenance energy requirements were estimated using baseline fat free mass (FFM) using the formula [(372 + 23.9 × FFM) × 1.5] [23]. Total macronutrient content in the provided diets was the same for both groups (55% carbohydrate, 15% protein and 30% fat). CR participants were provided a diet designed to produce a 400 kcal/day deficit from estimated energy requirements (considered a standard-of-care weight loss diet at the time the study was designed). ADF participants were provided meals, but instructed to fast on alternate days. On fed days, ADF participants were provided a diet estimated to meet estimated energy requirements, which was supplemented with ad libitum access to 5-7 optional food modules (200 kcal each). ADF participants were permitted to eat as much as they wished on fed days, but were not encouraged to eat all food provided. The caloric distribution provided on fed days was the same as in CR (20% breakfast, 30% lunch, 40% dinner and 10% snack). On fast days, ADF participants were instructed to begin their fast after the evening meal the preceding day, and to consume only water, calorie-free beverages and bouillon/stock cube soup. Daily energy and macronutrient intakes were calculated based on food return using PROnutra software (Viocare Technologies Inc., Princeton NJ). Estimated energy deficits were calculated by subtracting estimated daily EI from estimated daily energy requirements.

Outcome Measures

Body weight was measured using a calibrated digital scale to the nearest 0.1 kg. Height was measured using a wall-mounted stadiometer to the nearest 0.1 cm. Body composition, including total and regional fat mass (FM) and lean mass (LM), were measured using dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA, Discovery–W version 12.6, Hologic Inc., Bedford, MA). RMR was measured between 0600 and 0630 hours, following an overnight stay at the CTRC with an overnight fast and 24 hour abstention from exercise, using standard indirect calorimetry with the ventilated hood technique (TrueOne® 2400, ParvoMedics, Sandy, UT) [24]. An insulin-augmented frequently-sampled intravenous glucose tolerance test (IVGTT) was administered as previously described [25], and insulin sensitivity (Si) was determined using the MINMOD program (R Bergman, University of Southern California). Fasting blood samples were obtained for assessment of lipids, glucose, insulin, leptin, ghrelin and BDNF. Serum cholesterol, triglycerides, and HDL were measured with enzymatic reaction (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA), and LDL was calculated by the Friedewald equation [26]. Serum glucose concentrations were measured by the glucose oxidase method (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA). Serum insulin levels were measured by standard, double-antibody, radioimmunoassay techniques. Serum leptin and ghrelin were assayed using radioimmunoassay (RIA) (Linco Research, St Charles, MO). Serum BDNF levels were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using a previously described protocol modified for the R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) BDNF ELISA [27].

Safety Assessments

BMP, CBC, HR, BP, ECG, Questionnaire on Eating and Weight Patterns Revised (QEWP-R, assesses binge eating behaviors) [28, 29], and Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [30] were measured before and after the 36-hour test fast, at baseline prior to starting intervention, and at week 8. An ECG was also obtained 1 week after starting the intervention.

Statistical Analyses

Based on pilot weight loss data (W.T. Donahoo, unpublished data) from an 8-week CR protocol (-6.0±2.8 kg, n=11) and an 8-week ADF protocol (-11.25±3.3 kg, n=2) this study was planned to enroll 15 participants per arm to ensure 80% power at 5% significance level to detect a 3.1 kg (SD 2.89) between-group difference in weight loss at 8 weeks. SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for all analyses. Randomized participants with at least one post-baseline efficacy observation were included in the analyses with the exception of one ADF participant who was intentionally non-compliant with the protocol (EI on fast days >500 kcals/day). Analyses of outcomes were repeated with and without this participant and there was no difference in statistical conclusions. The primary analysis used a linear mixed-effects model with unstructured covariance consisting of the baseline value and the post-intervention evaluations as outcome measures, as well as evaluation time (baseline, week 8, week 32), group (ADF or CR), and their interaction term as fixed effects. Estimate of the interaction was used to assess efficacy of ADF as compared to CR and to test for statistical significance. Data imputation was not utilized. To evaluate the feasibility and fidelity of the intervention, energy and macronutrient intake data were summarized using descriptive statistics. Independent-samples t-tests compared weekly and average (weeks 1-8) energy and macronutrient intake between groups. Among ADF participants, similar analyses were performed to compare average energy and macronutrient intake between fast and fed days. Sensitivity analyses were used in various ways to examine the strength of the conclusions. Considering the two groups were not balanced with respect to baseline body weight, results for changes in body weight and composition are reported in both absolute (kg) and relative (%) terms and analyses of energy intake data were repeated with the outcome variables normalized to weight. Unless otherwise stated, data are presented as mean±SE.

Results

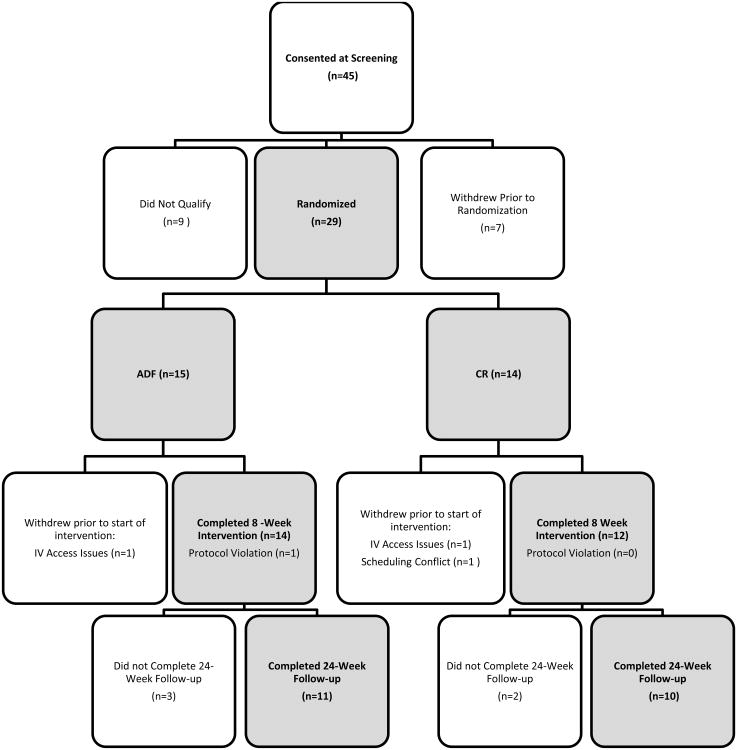

Study Enrollment and Attrition (Figure 1)

Figure 1. Study Flowchart.

Twenty–nine participants were randomized, however three withdrew post-randomization but prior to beginning the intervention. Twenty-six participants completed the 8-week intervention, and twenty-one completed the 24-week unsupervised follow-up.

Participant Characteristics (Table 1)

Table 1. Baseline Subject Characteristics by Treatment Group a-c.

| Characteristic | CR (n = 12) | ADF (n = 13) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 42.7 (7.9) | 39.6 (9.5) |

|

| ||

| Sex [n, (%)] | ||

| Female | 9 (75%) | 10 (77%) |

| Male | 3 (25%) | 3 (23%) |

|

| ||

| Ethnicity [n, (%)] | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 3 (25%) | 4 (31%) |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 8 (67%) | 8 (62%) |

| Unknown | 1 (8%) | 1 (8%) |

|

| ||

| Race [n, (%)] | ||

| White | 10 (83%) | 8 (62%) |

| Black/African American | 0 (0%) | 1 (8%) |

| Multiracial Origin | 0 (0%) | 2 (15%) |

| Unknown | 2 (17%) | 2 (15%) |

|

| ||

| Anthropometric Measures | ||

| Weight (kg) ** | 114.0 (20.0) | 94.7 (10.6) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 39.5 (6.0) | 35.8 (3.7) |

| Total Fat Mass (kg) ** | 48.8 (10.4) | 37.7 (8.1) |

| Trunk Fat Mass (kg) * | 26.0 (6.0) | 20.9 (6.2) |

| Total Lean Mass (kg) | 60.9 (11.5) | 53.2 (8.8) |

|

| ||

| Metabolic Measures | ||

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 171.3 (36.4) | 166.9 (33.2) |

| Total Direct HDL (mg/dL) | 38.9 (7.2) | 38.2 (8.1) |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 104.5 (28.8) | 100.0 (30.7) |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 139.6 (43.2) | 142.9 (56.2) |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 91.6 (7.8) | 88.4 (6.5) |

| Insulin (μU/mL) * | 19.3 (5.8) | 13.3 (6.0) |

| Si (× 104 μU/(mL min)) | 2.8 (4.6) | 1.9 (1.3) |

| Leptind (ng/mL) | 30.5 (11.8) | 29.8 (11.6) |

| Ghrelind (pg/mL) | 810.3 (229.6) | 767.5 (126.1) |

| BDNF(pg/mL) | 22552.1 (5695.5) | 20934.6 (7505.8) |

| RMR (kcal/day) * | 1892.5 (265.1) | 1640.1 (202.8) |

Fisher's exact test analyses completed for gender, ethnicity, and race. Number (%) all such values. Significance indicated by

p <0.05,

p<0.01.

Satterthwaite independent-samples t-test analyses completed for all continuous variables. Mean (SD) all such values.

Body Mass Index (BMI); High-density lipoprotein (HDL); Low-density lipoprotein (LDL); Insulin Sensitivity Index (SI); Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF); Resting Metabolic Rate (RMR).

n=12 in ADF group.

Participant BMI ranged from 30-52 kg/m2. CR and ADF were similar in age, sex, and ethnic/racial distributions. At baseline, mean±SD body weight (CR 114.0±20.0 kg, ADF 94.7±10.6 kg, p<0.01), FM, trunk FM, fasting insulin, and RMR were significantly greater in CR than ADF.

Safety Assessments

There were no significant changes in safety measures over the 8-week intervention. One participant in the ADF group developed gallbladder dyskinesia and underwent cholecystectomy 1 month after completing the 8-week intervention. This event was determined to be unrelated to the intervention.

Energy and Macronutrient Intake (Tables 2 and 3)

Table 2. Mean Daily Energy and Macronutrient Intake over 8 Weeks in CR and ADF a.

| Mean, Weeks 1-8 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Outcome Variable and Group | Unadjusted | p value | Adjusted b | p value |

| Energy Intake (kcal/day) | ||||

| CR | 2064.8 (120.6) | 18.6 (0.8) | ||

| ADF | 1373.9 (93.5) | 14.7 (0.8) | ||

| CR - ADF | 690.9 (150.1) | <.001 | 3.9 (1.2) | 0.004 |

| Protein (grams/day) | ||||

| CR | 83.1 (4.3) | 0.7 (0.1) | ||

| ADF | 55.2 (3.5) | 0.6 (0.1) | ||

| CR - ADF | 27.9 (5.4) | <.001 | 0.2 (0.0) | 0.001 |

| Fat (grams/day) | ||||

| CR | 71.2 (4.0) | 0.6 (0.1) | ||

| ADF | 49.4 (2.8) | 0.5 (0.1) | ||

| CR - ADF | 21.8 (4.8) | <.001 | 0.1 (0.0) | 0.008 |

| Carbs (grams/day) | ||||

| CR | 281.0 (18.4) | 2.5 (0.4) | ||

| ADF | 185.4 (14.3) | 2.0 (0.5) | ||

| CR - ADF | 95.6 (22.9) | <.001 | 0.6 (0.2) | 0.009 |

Independent-samples t-test analysis was used to assess food intake over 8 weeks. Results are mean (SE). Significant p values (p<0.05) are indicated in bold. For CR: n=10; For ADF: n=13.

Independent-samples t-test analysis is adjusted for body weight. Specifically, the amount of intake is normalized to per kg baseline body weight base.

Table 3. Mean Daily Energy and Macronutrient Intake on Fast and Fed Days Over 8 Weeks in ADF a.

| Mean, Weeks 1-8 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Outcome Variable and Group | Unadjusted | p value | Adjusted b | p value |

| Energy Intake (kcal/day) | ||||

| Fast | 44.4 (26.4) | 0.5 (0.3) | ||

| Fed | 2565.5 (147.8) | 28.2 (1.6) | ||

| Fast - Fed | -2521.0 (150.1) | <.001 | -27.7 (1.7) | <.001 |

| Protein (grams/day) | ||||

| Fast | 3.3 (2.8) | 0.0 (0.0) | ||

| Fed | 100.7 (5.5) | 1.1 (0.1) | ||

| Fast - Fed | -97.4 (6.2) | <.001 | -1.1 (0.1) | <.001 |

| Fat (grams/day) | ||||

| Fast | 2.7 (2.1) | 0.0 (0.0) | ||

| Fed | 90.5 (4.2) | 1.0 (0.1) | ||

| Fast - Fed | -87.8 (4.7) | <.001 | -1.0 (0.1) | <.001 |

| Carbs (grams/day) | ||||

| Fast | 5.7 (2.9) | 0.1 (0.0) | ||

| Fed | 345.0 (23.1) | 3.8 (0.3) | ||

| Fast - Fed | -339.3 (23.3) | <.001 | -3.8 (0.3) | <.001 |

Independent-samples t-test was used to assess food intake over 8 weeks. Results are mean (SE). Significant p values (p<0.05) are indicated in bold. For CR: n=10; For ADF: n=13.

Independent-samples t-test analysis is adjusted for body weight. Specifically, the amount of intake is normalized to per kg baseline body weight base.

Average daily energy and macronutrient intakes were significantly higher in CR compared to ADF over the 8-week intervention, even after adjusting for differences in baseline weight. EI on fed and fast days in ADF were 2565±148 kcal/day and 44±26 kcal/day, respectively. Estimated energy deficit from baseline weight maintenance energy requirements were -802±72 kcal/day in CR and -1178±51 kcal/day in ADF (p <0.001), which correspond to energy deficits of -28% and -47%, respectively.

Body Weight and Body Composition (Table 4)

Table 4. Changes in Anthropometric Measures at the end of the 8-Week Intervention and after 24 Weeks of Unsupervised Follow-up a, b.

| Assessment Period | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Outcome Variable and Group | Baseline | Week 8 | Week 32 | Week 8 - Baseline | p value | ES | Week 32 - Baseline | p value | ES | Week 32 – Week 8 | p value | ES | p value for overall interaction |

| Weight (kg) | |||||||||||||

| CR | 114.0 (4.6) | 106.9 (4.5) | 109.0 (4.7) | -7.1 (1.0) | <.001 | -5.0 (1.6) | 0.005 | 2.1 (1.0) | 0.047 | ||||

| ADF | 94.8 (4.4) | 86.5 (4.4) | 89.1 (4.5) | -8.2 (0.9) | <.001 | -5.7 (1.5) | 0.001 | 2.6 (1.0) | 0.013 | ||||

| CR - ADF | 19.3 (6.3) | 20.4 (6.3) | 19.9 (6.5) | 1.1 (1.3) | 0.409 | -0.35 | 0.7 (2.2) | 0.774 | -0.12 | -0.5 (1.4) | 0.739 | 0.14 | 0.559 |

| Weight (%) | |||||||||||||

| CR | -6.2 (0.9) | <.001 | -4.4 (1.6) | 0.011 | -1.8 (1.0) | 0.082 | |||||||

| ADF | -8.8 (0.9) | <.001 | -5.9 (1.5) | <.001 | -2.9 (1.0) | 0.006 | |||||||

| CR - ADF | 2.6 (1.3) | 0.056 | -0.84 | 1.5 (2.2) | 0.496 | -0.29 | 1.1 (1.4) | 0.456 | -0.32 | 0.456 | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||||||||||

| CR | 39.5 (1.4) | 37.1 (1.5) | 37.8 (1.6) | -2.4 (0.3) | <.001 | -1.7 (0.6) | 0.007 | 0.8 (0.4) | 0.045 | ||||

| ADF | 35.8 (1.4) | 32.6 (1.4) | 33.6 (1.5) | -3.2 (0.3) | <.001 | -2.2 (0.5) | <.001 | 1.0 (0.4) | 0.008 | ||||

| CR - ADF | 3.7 (2.0) | 4.5 (2.1) | 4.2 (2.2) | 0.7 (0.5) | 0.136 | -0.64 | 0.5 (0.8) | 0.548 | -0.25 | -0.2 (0.5) | 0.65 | 0.19 | 0.207 |

| Total Fat Mass (kg) | |||||||||||||

| CR | 48.8 (2.7) | 45.1 (2.6) | 46.3 (2.9) | -3.7 (0.5) | <.001 | -2.5 (1.1) | 0.028 | 1.2 (0.8) | 0.162 | ||||

| ADF | 37.7 (2.6) | 33.9 (2.5) | 33.5 (2.8) | -3.7 (0.5) | <.001 | -4.2 (1.0) | <.001 | -0.4 (0.8) | 0.605 | ||||

| CR - ADF | 11.1 (3.7) | 11.1 (3.6) | 12.8 (4.0) | 0.0 (0.8) | 0.995 | 0.00 | 1.6 (1.5) | 0.291 | -0.45 | 1.6 (1.2) | 0.173 | -0.59 | 0.371 |

| Total Fat Mass (%) | |||||||||||||

| CR | 43.4 (1.7) | 42.4 (1.7) | 42.7 (1.7) | -1.0 (0.3) | 0.007 | -0.7 (0.5) | 0.222 | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.530 | ||||

| ADF | 40.3 (1.6) | 39.2 (1.6) | 38.0 (1.7) | -1.1 (0.3) | 0.002 | -2.4 (0.5) | <.001 | -1.3 (0.5) | 0.015 | ||||

| CR - ADF | 3.1 (2.3) | 3.2 (2.4) | 4.7 (2.4) | 0.1 (0.5) | 0.826 | -0.09 | 1.7 (0.8) | 0.035 | -0.93 | 1.6 (0.7) | 0.032 | -0.95 | 0.078 |

| Trunk Fat Mass (kg) | |||||||||||||

| CR | 26.0 (1.8) | 23.9 (1.7) | 24.7 (1.8) | -2.1 (0.4) | <.001 | -1.3 (0.7) | 0.054 | 0.8 (0.4) | 0.093 | ||||

| ADF | 20.9 (1.7) | 18.5 (1.7) | 18.2 (1.7) | -2.4 (0.4) | <.001 | -2.7 (0.6) | <.001 | -0.3 (0.4) | 0.436 | ||||

| CR - ADF | 5.1 (2.5) | 5.4 (2.4) | 6.5 (2.5) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.637 | -0.20 | 1.4 (0.9) | 0.144 | -0.63 | 1.1 (0.6) | 0.083 | -0.76 | 0.215 |

| Trunk Fat Mass (%) | |||||||||||||

| CR | 23.1 (1.1) | 22.4 (1.2) | 22.7 (1.1) | -0.7 (0.3) | 0.017 | -0.3 (0.4) | 0.340 | 0.3 (0.3) | 0.274 | ||||

| ADF | 22.1 (1.1) | 21.2 (1.1) | 20.3 (1.1) | -0.9 (0.3) | 0.001 | -1.8 (0.3) | <.001 | -0.8 (0.3) | 0.005 | ||||

| CR - ADF | 1.0 (1.6) | 1.3 (1.7) | 2.4 (1.5) | 0.3 (0.4) | 0.484 | -0.30 | 1.4 (0.5) | 0.009 | -1.19 | 1.2 (0.4) | 0.007 | -1.24 | 0.016 |

| Lean Mass (kg) | |||||||||||||

| CR | 60.9 (3.0) | 58.2 (2.8) | 59.3 (2.8) | -2.6 (0.6) | <.001 | -1.6 (0.6) | 0.022 | 1.1 (0.5) | 0.051 | ||||

| ADF | 53.2 (2.8) | 50.0 (2.7) | 52.1 (2.7) | -3.2 (0.6) | <.001 | -1.2 (0.6) | 0.072 | 2.0 (0.5) | <.001 | ||||

| CR - ADF | 7.7 (4.1) | 8.2 (3.8) | 7.2 (3.9) | 0.5 (0.9) | 0.539 | -0.26 | -0.4 (0.9) | 0.640 | 0.20 | -1.0 (0.7) | 0.197 | 0.55 | 0.424 |

| Lean Mass (%) | |||||||||||||

| CR | 54.2 (1.6) | 55.1 (1.6) | 54.8 (1.7) | 0.9 (0.3) | 0.016 | 0.5 (0.5) | 0.309 | -0.3 (0.5) | 0.509 | ||||

| ADF | 57.1 (1.5) | 58.0 (1.6) | 59.3 (1.6) | 0.9 (0.3) | 0.009 | 2.2 (0.5) | <.001 | 1.3 (0.5) | 0.012 | ||||

| CR - ADF | -2.8 (2.2) | -2.9 (2.3) | -4.5 (2.3) | -0.1 (0.5) | 0.921 | 0.04 | -1.7 (0.7) | 0.026 | 0.99 | -1.6 (0.7) | 0.026 | 0.99 | 0.061 |

Linear Mixed Effects model analysis with unstructured covariance was used to assess the efficacy of intervention on each outcome variable. Test of time by group interaction used to test the efficacy of intervention (see p value for overall interaction). Results are mean (SE). Significant p values (p <0.05) are indicated in bold. Effect size (ES) is calculated as (2 × t value)/√DF, where degrees of freedom (DF). Hand calculations for between- and within-group differences may not be equal to data shown because all data were rounded to 0.1 decimal place. Weight changes from scale weight (kg) do not match weight changes from sum of DXA fat mass and lean mass due to the different methodologies used to measure these outcomes. For CR: n=12 for baseline and week 8; n=10 for week 32; For ADF: n=13 for baseline and week 8; n=11 for week 32; Non-missing observations: n = 71.

Body Mass Index (BMI).

At the end of the 8-week intervention, absolute weight change (CR -7.1±1.0 kg, ADF-8.2±0.9 kg) did not differ between groups. However, there was a marginally significant between-group difference in relative weight change (CR -6.2±0.9%, ADF -8.8±0.9%, p=0.056). There were no significant differences in change in absolute (kg) or relative (%) FM, trunk FM, and LM over the 8-week intervention. Between the end of the 8-week intervention and the end of the 24-week follow-up (week 8 to 32) there were no differences in weight regain, however, the composition of weight regain tended to differ between groups. CR gained 1.2±0.8 kg of FM and 1.1±0.5 kg of LM, conversely, ADF lost -0.4±0.8 kg of FM (p=0.173 vs. CR) and gained 2.0±0.5 kg of LM (p=0.197 vs. CR). Between baseline and the end of the 24-week follow-up (baseline to week 32) there were no differences in absolute or relative weight change (Table 4) and differences in change in absolute FM (CR -2.5±1.1 kg, ADF -4.2±1.0 kg), trunk FM (CR -1.3±0.7 kg, ADF -2.7±0.6 kg), or LM (CR -1.6±0.6 kg, ADF -1.2±0.6 kg) did not reach statistical significance. However, %FM (CR -0.7±0.5%, ADF -2.4±0.5%, p=0.035) and %trunk FM (CR -0.3±0.4%, ADF -1.8±0.3%, p=0.009) decreased more in ADF, and %LM (CR 0.5±0.5%, ADF 2.2±0.5%, p=0.026) increased more in ADF.

Resting Metabolic Rate (RMR) (Table 5)

Table 5. Changes in Resting Metabolic Rate at the end of the 8-Week Intervention and after 24 Weeks of Unsupervised Follow-up a, b.

| Assessment Period | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Outcome Variable and Group | Baseline | Week 8 | Week 32 | Week 8 - Baseline | p value | ES | Week 32 - Baseline | p value | ES | Week 32 – Week 8 | p value | ES | p value for overall interaction |

| Unadjusted RMR (kcal/day)c | |||||||||||||

| CR | 1892.5 (67.7) | 1719.3 (69.3) | 1807.3 (72.2) | -173.2 (35.2) | <.001 | -85.2 (39.0) | 0.039 | 88.0 (22.2) | <.001 | ||||

| ADF | 1640.1 (65.1) | 1539.7 (66.8) | 1567.2 (69.2) | -100.4 (34.1) | 0.007 | -72.9 (37.3) | 0.063 | 27.5 (22.0) | 0.223 | ||||

| CR - ADF | 252.4 (93.9) | 179.6 (96.2) | 240.1 (100.0) | -72.8 (49.0) | 0.151 | 0.62 | -12.3 (54.0) | 0.822 | 0.09 | 60.5 (31.3) | 0.065 | -0.81 | 0.096 |

| Adjusted RMR (kcal/day)c, d | |||||||||||||

| CR | 1757.6 (37.0) | 1646.0 (32.8) | 1681.53 (18.6) | -111.6 (36.9) | 0.006 | -76.1 (35.9) | 0.045 | 35.6 (22.4) | 0.126 | ||||

| ADF | 1689.0 (34.2) | 1672.8 (33.5) | 1659.8 (20.1) | -16.2 (36.6) | 0.662 | -29.2 (35.2) | 0.416 | -13.0 (22.5) | 0.569 | ||||

| CR - ADF | 68.6 (51.1) | -26.8 (48.1) | 21.7 (29.8) | -95.4 (51.4) | 0.076 | 0.77 | -46.9 (49.7) | 0.356 | 0.39 | 48.5 (31.8) | 0.140 | -0.64 | 0.140 |

Linear Mixed Effects model analysis with unstructured covariance was used to assess the efficacy of intervention on each outcome variable. Test of time by group interaction used to test the efficacy of intervention (see p value for overall interaction). Results are mean (SE). Significant p values (p <0.05) are indicated in bold. Effect size (ES) is calculated as (2 × t value)/√DF, where degrees of freedom (DF). Hand calculations for between- and within-group differences may not be equal to data shown because all data were rounded to 0.1 decimal place. For CR: n=12 for baseline and week 8; n=10 for week 32; For ADF: n=13 for baseline and week 8; n=11 for week 32; Non-missing observations: n = 71.

Resting Metabolic Rate (RMR).

RMR results exclude 1 observation at week 32 for 1 subject in ADF because the value was physiologically implausible.

RMR results adjusted for Fat Free Mass (FFM) and Fat Mass (FM).

At week 8, RMR decreased significantly from baseline in both CR and ADF with no significant difference between groups. After 24 weeks of follow-up, RMR decreased significantly from baseline in CR but not in ADF; however, differences between groups were not significant. When adjusted for FM and FFM, RMR decreased significantly from baseline to week 8 in CR (-111.6±36.9 kcal/day, p=0.006) but not in ADF (-16.2±36.6 kcal/day, p=0.662) with a trend (p=0.076) for a between-group difference. Adjusted RMR also decreased significantly from baseline to week 32 in CR (-76.1±35.9 kcal/day, p=0.045) but not in ADF (-29.2±35.2 kcal/day, p=0.416); the between-group difference was not significant.

Lipids and Insulin Sensitivity (Table 6)

Table 6. Changes in Metabolic Measures at the end of the 8-Week Intervention and after 24 Weeks of Unsupervised Follow-up a, b.

| Assessment Period | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Outcome Variable and Group |

Baseline | Week 8 | Week 32 | Week 8 – Baseline |

p value |

ES | Week 32 - Baseline |

p value |

ES | Week 32 – Week 8 |

p value |

ES | p value for overall interaction |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL)c | |||||||||||||

| CR | 171.3 (10.0) | 149.7 (10.6) | -21.7 (6.8) | 0.004 | |||||||||

| ADF | 166.9 (9.6) | 135.1 (10.1) | -31.8 (6.5) | <.001 | |||||||||

| CR - ADF | 4.5 (13.9) | 14.6 (14.6) | 10.1 (9.4) | 0.295 | -0.45 | ||||||||

| HDL (mg/dL)c | |||||||||||||

| CR | 38.9 (2.2) | 34.8 (2.0) | -4.2 (1.9) | 0.043 | |||||||||

| ADF | 38.2 (2.1) | 34.1 (1.9) | -4.2 (1.9) | 0.036 | |||||||||

| CR - ADF | 0.7 (3.1) | 0.7 (2.7) | 0.0 (2.7) | 0.996 | 0.00 | ||||||||

| LDL (mg/dL)c | |||||||||||||

| CR | 104.5 (8.6) | 87.6 (8.9) | -16.9 (4.9) | 0.002 | |||||||||

| ADF | 100.0 (8.3) | 77.4 (8.6) | -22.6 (4.7) | <.001 | |||||||||

| CR - ADF | 4.5 (11.9) | 10.2 (12.4) | 5.7 (6.8) | 0.412 | -0.35 | ||||||||

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | |||||||||||||

| CR | 139.6 (14.6) | 136.8 (11.5) | 151.6 (23.4) | -2.8 (11.3) | 0.804 | 12.0 (17.1) | 0.489 | 14.9 (18.2) | 0.422 | ||||

| ADF | 142.9 (14.0) | 117.9 (11.1) | 148.1 (24.2) | -25.0 (10.9) | 0.031 | 5.1 (18.8) | 0.787 | 30.1 (19.7) | 0.139 | ||||

| CR - ADF | -3.3 (20.2) | 18.8 (16.0) | 3.6 (33.6) | 22.2 (15.7) | 0.170 | -0.59 | 6.9 (25.4) | 0.789 | -0.11 | -15.3 (26.8) | 0.574 | 0.24 | 0.382 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | |||||||||||||

| CR | 91.6 (2.1) | 94.9 (1.8) | 93.3 (2.2) | 3.3 (2.3) | 0.166 | 1.7 (1.9) | 0.389 | -1.6 (2.1) | 0.472 | ||||

| ADF | 88.4 (2.0) | 94.4 (1.7) | 91.0 (2.3) | 6.0 (2.1) | 0.010 | 2.6 (2.1) | 0.228 | -3.4 (2.2) | 0.140 | ||||

| CR - ADF | 3.2 (2.9) | 0.5 (2.5) | 2.4 (3.2) | -2.7 (3.1) | 0.389 | 0.37 | -0.9 (2.8) | 0.76 | 0.13 | 1.9 (3.1) | 0.553 | -0.25 | 0.680 |

| Insulin (μU/mL) | |||||||||||||

| CR | 19.3 (1.7) | 19.1 (2.1) | 17.2 (2.1) | -0.2 (2.4) | 0.945 | -2.0 (2.2) | 0.359 | -1.9 (1.3) | 0.157 | ||||

| ADF | 13.3 (1.6) | 16.3 (2.0) | 13.7 (2.1) | 3.0 (2.3) | 0.207 | 0.4 (2.2) | 0.855 | -2.6 (1.4) | 0.075 | ||||

| CR - ADF | 5.9 (2.4) | 2.8 (2.9) | 3.5 (3.0) | -3.1 (3.3) | 0.352 | 0.40 | -2.4 (3.1) | 0.437 | 0.33 | 0.7 (1.9) | 0.703 | -0.16 | 0.642 |

| Si (× 104 μU/(mL min)) | |||||||||||||

| CR | 2.6 (0.9) | 2.6 (0.8) | 3.2 (1.7) | 0.0 (0.2) | 0.967 | 0.7 (0.8) | 0.421 | 0.7 (0.9) | 0.461 | ||||

| ADF | 1.9 (0.9) | 2.0 (0.8) | 3.0 (1.7) | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.676 | 1.1 (0.8) | 0.218 | 1.0 (0.9) | 0.295 | ||||

| CR - ADF | 0.6 (1.3) | 0.6 (1.2) | 0.3 (2.4) | -0.1 (0.3) | 0.799 | 0.11 | -0.4 (1.2) | 0.735 | 0.15 | -0.3 (1.2) | 0.803 | 0.11 | 0.898 |

| Leptin (ng/mL) | |||||||||||||

| CR | 30.5 (3.4) | 19.2 (2.9) | 31.4 (4.7) | -11.3 (2.3) | <.001 | 0.9 (3.0) | 0.761 | 12.2 (3.0) | <.001 | ||||

| ADF | 29.2 (3.3) | 15.2 (2.8) | 26.1 (4.8) | -13.9 (2.4) | <.001 | -3.1 (3.3) | 0.363 | 10.8 (3.3) | 0.003 | ||||

| CR - ADF | 1.3 (4.7) | 4.0 (4.0) | 5.3 (6.7) | 2.7 (3.3) | 0.432 | -0.33 | 4.0 (4.5) | 0.379 | -0.37 | 1.4 (4.5) | 0.761 | -0.13 | 0.599 |

| Ghrelin (pg/mL) | |||||||||||||

| CR | 810.3 (53.0) | 894.3 (79.4) | 881.6 (56.8) | 84.0 (45.6) | 0.079 | 71.4 (34.2) | 0.048 | -12.7 (48.1) | 0.795 | ||||

| ADF | 775.8 (51.4) | 900.2 (77.2) | 792.4 (57.5) | 124.4 (46.2) | 0.013 | 16.6 (38.7) | 0.673 | -107.8 (50.2) | 0.043 | ||||

| CR - ADF | 34.5 (73.8) | -5.9 (110.8) | 89.3 (80.8) | -40.4 (64.9) | 0.540 | 0.26 | 54.8 (51.6) | 0.300 | -0.44 | 95.2 (69.6) | 0.184 | -0.57 | 0.364 |

| BDNF (pg/mL) | |||||||||||||

| CR | 22552.1 (1934.4) | 18510.0 (2070.6) | 18317.8 (1849.0) | -4042.1 (2124.3) | 0.070 | 4234.3 (2453.1) | 0.098 | -192.2 (2380.7) | 0.936 | ||||

| ADF | 20934.6 (1858.5) | 20165.4 (1989.4) | 25738.0 (1936.9) | -769.2 (2041.0) | 0.710 | -4803.4 (2480.0) | 0.065 | 5572.6 (2414.0) | 0.030 | ||||

| CR - ADF | 1617.5 (2682.5) | -1655.4 (2871.5) | -7420.2 (2677.8) | -3272.9 (2945.9) | 0.278 | 0.46 | 9037.7 (3488.3) | 0.016 | 1.08 | -5764.8 (3390.5) | 0.103 | 0.71 | 0.053 |

Linear Mixed Effects model analysis with unstructured covariance was used to assess the efficacy of intervention on each outcome variable. Test of time by group interaction used to test the efficacy of intervention (see p value for overall interaction). Results are mean (SE). Significant p values (p <0.05) are indicated in bold. Effect size (ES) is calculated as (2 × t value)/√DF, where degrees of freedom (DF). Hand calculations for between- and within-group differences may not be equal to data shown because all data were rounded to 0.1 decimal place. For CR: n=12 for baseline and week 8; n=10 for week 32; For ADF: n=13 for baseline and week 8; n=11 for week 32; Non-missing observations: n = 71.

High-density lipoprotein (HDL); Low-density lipoprotein (LDL); Insulin Sensitivity Index (Si); Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF).

No available data for week 32.

At week 8, total cholesterol, HDL, and LDL decreased significantly in both groups and triglycerides decreased significantly in ADF; however there were no between-group differences in any lipid parameter changes. Fasting glucose decreased significantly at week 8 in ADF; however, there were no other within- or between-group differences in changes in fasting insulin, glucose, or Si at week 8 or week 32.

Leptin, Ghrelin, and BDNF (Table 6)

There were no between-group differences in change in leptin or ghrelin at week 8 or week 32. Change in BDNF from baseline to week 8 did not differ between groups. Between baseline and week 32, BDNF increased in ADF (4803±2480 pg/mL) but decreased in CR (-4234±2453 pg/mL), with a significant between-group difference in change in BDNF (p=0.016).

Discussion

This study is the first randomized trial comparing ADF to moderate daily CR. Results suggest zero-calorie ADF is safe and tolerable, and is equivalent to moderate CR in producing short-term weight loss and improving body composition and metabolic parameters. While relative (%) weight loss was greater in the ADF group at the end of the 8-week intervention, this difference was only marginally significant (p=0.056) and may be driven by the differences in baseline body weight between groups. The estimated energy deficit from weight maintenance needs over the 8-week intervention was significantly higher in ADF compared to CR (by ∼376 kcal/day). This would be expected to result in several kilograms greater weight loss in the ADF group; however, weight loss was only 1.1 kg greater in ADF. Possible explanations include: 1) the ADF group under-reported food intake on fast and/or fed days or 2) fasting led to a reduction in some component of non-resting energy expenditure in the ADF group (e.g. PA energy expenditure, thermic effect of food). This should be explored in future studies with more accurate assessments of EI and a more detailed assessment of components of EE.

Importantly, ADF was not associated with an increased risk for weight regain after 24 weeks of unsupervised follow-up. However, composition of weight regain tended to differ. During the 24-week follow-up, ADF lost FM (-0.4±0.8 kg) and gained LM (2.0±0.5 kg) while CR gained both FM (1.2±0.8 kg) and LM (1.1±0.5 kg). As a result, changes in body composition at the end of 24 weeks of follow-up tended to be more favorable in ADF than in CR. Because this was a pilot study, we did not formally assess EI or PA during the follow-up period. However, some participants in the ADF group reported that they continued to fast intermittently (once or twice a week) and this may have contributed to the beneficial changes in body composition observed during the follow-up period. Alternatively, the 8-week ADF intervention may have induced metabolic or hormonal adaptations that led to this differential pattern of weight regain. These findings should be interpreted with caution given the difference in baseline body weights and the fact that our study was not powered to detect differences in body composition. Nonetheless, determining whether ADF leads to more favorable changes in body composition, and the mechanisms via which this may occur, is an area worthy of future investigation.

Another factor that may have contributed to the more favorable changes in body composition in ADF is RMR. When adjusted for FM and FFM, RMR decreased significantly in CR but not in ADF over the 8-week intervention with a trend (p =0.076) for a between-group difference. Other studies have found a decrease in RMR greater than expected due to changes in body composition alone with weight loss induced by CR [31, 32] consistent with what was observed in the CR group over the 8-week intervention. The apparent impact of ADF on preserving RMR during weight loss could have clinical significance in preventing weight regain after weight loss and should be explored in larger studies.

There were no significant between-group differences in changes in leptin or ghrelin at week 8 or after 24 weeks of follow-up. Changes in serum BDNF levels were also not different between groups at week 8. Surprisingly, after 24 weeks of follow-up, BDNF increased in ADF, but decreased in CR (p=0.016). BDNF has been suggested to play a role in regulation of energy balance [20-22]. BDNF heterozygous knock-out mice are severely obese and exhibit hyperphagia, impaired thermogenesis, and reduced locomotor activity [22]. In humans, BDNF mutations are associated with hyperphagia and obesity [33], and a single nucleotide polymorphism is related to obesity in large-scale genome-wide association studies [34, 35]. Our results suggest ADF induces long-term changes in BDNF secretion, which may contribute to improved weight loss maintenance through effects on energy balance. This is supported by the more favorable changes in body composition at 24 weeks follow-up in the ADF group. However, this result should be interpreted with caution, as changes in BDNF did not correlate with changes in weight or body composition (data not shown).

Total cholesterol, HDL, and LDL decreased significantly in both groups and fasting glucose and triglycerides decreased significantly in ADF at 8 weeks; however there were no between-group differences in change in metabolic parameters, suggesting the diets had similar effects on these metabolic disease risk indicators. These results are similar to those of prior studies, which suggest ADF produces improvements in fasting lipids [13-18].

Strengths of the current study include the randomized design, measurement of EI using analysis of returned food, and metabolic measurements obtained during a controlled inpatient setting. However, this study has several limitations. This was a pilot study primarily aimed at assessing safety and tolerability, and the small sample size may explain the lack of statistical significance in some outcomes between groups. For example, effect sizes for between-group differences in changes in weight at weeks 8 and 32 are small (-0.35 and -0.12, respectively), confirming we would need a larger sample size to observe a significant between-group difference. Randomization was stratified by sex only and resulted in a significantly higher mean baseline body weight in CR. Because of the small number of males (n=3 per group), we could not determine if there were any sex effects. We did not obtain measurements of PA during the intervention or follow-up period, thus it is not possible to assess how changes in PA energy expenditure may impact weight loss in either group. We do not have measurements of EI or data on whether participants may have continued to employ ADF or CR during the follow-up period. Finally, generalizability of results is limited because participants were provided all food during the 8-week intervention. Food provision may have favored weight loss in CR as they were not burdened with the practical challenges of practicing daily CR (i.e. accurately counting calories, choosing appropriate portion sizes, making healthy food choices).

Conclusion

Our results suggest an 8-week zero-calorie ADF regimen was safe and tolerable. ADF appeared to produce a greater energy deficit from weight-maintenance requirements than moderate daily CR, though weight loss and changes in lipids and Si were similar at the end of the 8-week intervention. ADF was not associated with greater weight regain after 24 weeks of unsupervised follow-up. ADF may represent a reasonable alternative dietary strategy for treatment of obesity (especially for those that find daily CR difficult) and should be explored in larger efficacy studies with a longer intervention period and more detailed measures of components of energy balance.

Study Importance Questions.

What is Known About This Topic?

Short-term studies (2-12 weeks) suggest alternate-day fasting (ADF) may produce 3-8% reductions in body weight, however randomized controlled trials comparing ADF to the standard moderate calorie-restricted diets currently recommended for weight loss are lacking.

The safety and tolerability of a zero-calorie ADF regimen is not known.

The effects of ADF on body composition, lipids, and insulin sensitivity index (Si) have not been well-studied nor is it known whether risk for weight regain may be greater after ADF-induced weight loss.

What This Study Adds?

No adverse effects were associated with the zero-calorie ADF regimen, and most participants (93%) who started the intervention successfully completed the 8-week ADF protocol.

When compared to a standard moderate calorie-restricted diet (-400 kcal/day), an ADF regimen produced similar changes in weight, fat mass, lean mass, lipids, and insulin sensitivity index (Si) at 8 weeks in adults with obesity.

Weight regain after 24 weeks of unsupervised follow-up was not different between groups, thus the 8-week ADF intervention did not appear to increase risk for weight regain.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Archana Mande RD, Janine Higgins PhD, and Joni Donahoo DNP of the CU-AMC CTRC for protocol support.

Funding: NIH R21 AT002617-02, NIH UL1 TR001082, NIH DK 048520, the Colorado Obesity Research Institute (CORI), and the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Melanson is supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Denver VA Medical Center.

Footnotes

Disclosure: No authors have any potential conflicts of interest to disclose

References

- 1.Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, Ard JD, Comuzzie AG, Donato KA, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129(25 Suppl 2):S102–38. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults--The Evidence Report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res. 1998;6(2):51S–209S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson JW, Konz EC, Frederich RC, Wood CL. Long-term weight-loss maintenance: a meta-analysis of US studies. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2001;74(5):579–84. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.5.579. Epub 2001/10/31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collier R. Intermittent fasting: the science of going without. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2013;185(9):E363–4. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-4451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collier R. Intermittent fasting: the next big weight loss fad. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2013;185(8):E321–2. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-4437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnstone A. Fasting for weight loss: an effective strategy or latest dieting trend? Int J Obes (Lond) 2015;39(5):727–33. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2014.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patterson RE, Laughlin GA, LaCroix AZ, Hartman SJ, Natarajan L, Senger CM, et al. Intermittent Fasting and Human Metabolic Health. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2015;115(8):1203–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horne BD, Muhlestein JB, Anderson JL. Health effects of intermittent fasting: hormesis or harm? A systematic review. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2015;102(2):464–70. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.109553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mattson MP, Allison DB, Fontana L, Harvie M, Longo VD, Malaisse WJ, et al. Meal frequency and timing in health and disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(47):16647–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413965111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnosky AR, Hoddy KK, Unterman TG, Varady KA. Intermittent fasting vs daily calorie restriction for type 2 diabetes prevention: a review of human findings. Translational research : the journal of laboratory and clinical medicine. 2014;164(4):302–11. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2014.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varady KA, Hellerstein MK. Alternate-day fasting and chronic disease prevention: a review of human and animal trials. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2007;86(1):7–13. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson JB, Summer W, Cutler RG, Martin B, Hyun DH, Dixit VD, et al. Alternate day calorie restriction improves clinical findings and reduces markers of oxidative stress and inflammation in overweight adults with moderate asthma. Free radical biology & medicine. 2007;42(5):665–74. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Varady KA, Bhutani S, Church EC, Klempel MC. Short-term modified alternate-day fasting: a novel dietary strategy for weight loss and cardioprotection in obese adults. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2009;90(5):1138–43. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eshghinia S, Mohammadzadeh F. The effects of modified alternate-day fasting diet on weight loss and CAD risk factors in overweight and obese women. Journal of diabetes and metabolic disorders. 2013;12(1):4. doi: 10.1186/2251-6581-12-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhutani S, Klempel MC, Kroeger CM, Trepanowski JF, Varady KA. Alternate day fasting and endurance exercise combine to reduce body weight and favorably alter plasma lipids in obese humans. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md. 2013;21(7):1370–9. doi: 10.1002/oby.20353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoddy KK, Kroeger CM, Trepanowski JF, Barnosky A, Bhutani S, Varady KA. Meal timing during alternate day fasting: Impact on body weight and cardiovascular disease risk in obese adults. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) 2014;22(12):2524–31. doi: 10.1002/oby.20909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klempel MC, Kroeger CM, Varady KA. Alternate day fasting (ADF) with a high-fat diet produces similar weight loss and cardio-protection as ADF with a low-fat diet. Metabolism. 2013;62(1):137–43. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varady KA, Bhutani S, Klempel MC, Kroeger CM, Trepanowski JF, Haus JM, et al. Alternate day fasting for weight loss in normal weight and overweight subjects: a randomized controlled trial. Nutr J. 2013;12(1):146. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-12-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li L, Wang Z, Zuo Z. Chronic intermittent fasting improves cognitive functions and brain structures in mice. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66069. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bariohay B, Lebrun B, Moyse E, Jean A. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor plays a role as an anorexigenic factor in the dorsal vagal complex. Endocrinology. 2005;146(12):5612–20. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu B, Goulding EH, Zang K, Cepoi D, Cone RD, Jones KR, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor regulates energy balance downstream of melanocortin-4 receptor. Nature neuroscience. 2003;6(7):736–42. doi: 10.1038/nn1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.An JJ, Liao GY, Kinney CE, Sahibzada N, Xu B. Discrete BDNF Neurons in the Paraventricular Hypothalamus Control Feeding and Energy Expenditure. Cell Metab. 2015;22(1):175–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grunwald GK, Melanson EL, Forster JE, Seagle HM, Sharp TA, Hill JO. Comparison of methods for achieving 24-hour energy balance in a whole-room indirect calorimeter. Obes Res. 2003;11(6):752–9. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haugen HA, Melanson EL, Tran ZV, Kearney JT, Hill JO. Variability of measured resting metabolic rate. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2003;78(6):1141–5. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.6.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melby CL, Ho RC, Jeckel K, Beal L, Goran M, Donahoo WT. Comparison of risk factors for obesity in young, nonobese African-American and Caucasian women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24(11):1514–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clinical chemistry. 1972;18(6):499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carlson O, Martin B, Stote KS, Golden E, Maudsley S, Najjar SS, et al. Impact of reduced meal frequency without caloric restriction on glucose regulation in healthy, normal-weight middle-aged men and women. Metabolism. 2007;56(12):1729–34. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spitzer RL, Devlin M, Walsh BT, Hasin D, Wing R, Marcus M, et al. Binge eating disorder: A multi-site field trial of the diagnostic criteria. Int J Eat Disord. 1992;11:191–203. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spitzer RL, Yanovski S, Wadden T, Wing R, Marcus MD, Stunkard A, et al. Binge eating disorder: its further validation in a multisite study. Int J Eat Disord. 1993;13(2):137–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Astrup A, Gotzsche PC, van de Werken K, Ranneries C, Toubro S, Raben A, et al. Meta-analysis of resting metabolic rate in formerly obese subjects. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 1999;69(6):1117–22. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.6.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leibel RL, Rosenbaum M, Hirsch J. Changes in energy expenditure resulting from altered body weight. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(10):621–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503093321001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vanevski F, Xu B. Molecular and neural bases underlying roles of BDNF in the control of body weight. Frontiers in neuroscience. 2013;7:37. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hotta K, Nakamura M, Nakamura T, Matsuo T, Nakata Y, Kamohara S, et al. Association between obesity and polymorphisms in SEC16B, TMEM18, GNPDA2, BDNF, FAIM2 and MC4R in a Japanese population. Journal of human genetics. 2009;54(12):727–31. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2009.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thorleifsson G, Walters GB, Gudbjartsson DF, Steinthorsdottir V, Sulem P, Helgadottir A, et al. Genome-wide association yields new sequence variants at seven loci that associate with measures of obesity. Nat Genet. 2009;41(1):18–24. doi: 10.1038/ng.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]