Abstract

Striking disparities in access to healthcare and in health outcomes are major characteristics of health across the globe. This inequitable state of global health and how it could be improved has become a highly popularized field of academic study. In a series of articles in this journal the roles of power and politics in global health have been addressed in considerable detail. Three points are added here to this debate. The first is consideration of how the use of definitions and common terms, for example ‘poverty eradication,’ can mask full exposure of the extent of rectification required, with consequent failure to understand what poverty eradication should mean, how this could be achieved and that a new definition is called for. Secondly, a criticism is offered of how the term ‘global health’ is used in a restricted manner to describe activities that focus on an anthropocentric and biomedical conception of health across the world. It is proposed that the discourse on ‘global health’ should be extended beyond conventional boundaries towards an ecocentric conception of global/planetary health in an increasingly interdependent planet characterised by a multitude of interlinked crises. Finally, it is noted that the paucity of workable strategies towards achieving greater equity in sustainable global health is not so much due to lack of understanding of, or insight into, the invisible dimensions of power, but is rather the outcome of seeking solutions from within belief systems and cognitive biases that cannot offer solutions. Hence the need for a new framing perspective for global health that could reshape our thinking and actions.

Keywords: Global/Planetary Health, Belief Systems, Values, Framing, Poverty, Power

Introduction

Striking disparities and inequities in access to healthcare and inequalities in health outcomes are major characteristics of health across the globe.1,2 How these disparities are described and could be narrowed has become a highly popularized field of academic and political attention in recent decades. In a series of articles in this journal many aspects of power and politics have been explicated in an attempt to better understand their roles in improving global health (Box 1).3-7

Box 1. Aspects of Power Debated

Modes of power: financial power, power of knowledge, normative power

Forms of power: structural and productive power, and the legitimacy and accountability of each of these

The many associated forms of power relations that underlie how institutions operate and influence what we believe to be the truth

Requirements for social scientists interested in the politics of global health to be aware that there is no ‘view from nowhere’ and therefore to be ‘reflexive’ about their own exercise of structural and productive power

The politics of challenging the powerful and the need to investigate the various forms of expertise that are conventionally thought of as being ‘outside’ global health

That global health research is essentially normative while lacking a widely accepted normative premise

The multi-disciplinary and inter-disciplinary nature of global health work that makes it more inclusive of social sciences than public health and international health

Recognizing that the unconscious and unacknowledged nature of the norms, politics and power that drive global health, are a direct product of the processes through which power operates and a primary mechanism by which power sustains and reinforces itself

Need to make more visible how power operates

Recommendations that in addition to broadening the disciplinary base of global health research to those social sciences with deep traditions of thought in the domains of power, politics and norms, individual and institutions should be encouraged to adopt commitments to be reflexive, humble and to address equitable practices within global health research’ with the goal of facilitating commitment to equity in global health outcomes as well as practice.

To extend this debate beyond conventional boundaries, several additional considerations are introduced here: a critical perspective on the definition of poverty with a more ambitious resolve for poverty eradication; improved clarity in ‘global health’ terminology; the role of belief systems, framing and metaphors that shape our thinking; and the need to shift the dominant belief system towards an ecological conception of global/planetary health.

Poverty Eradication

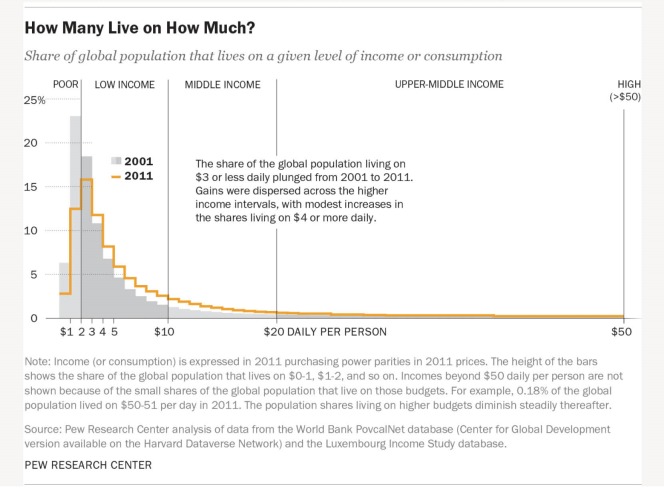

The Pew Research Center Report,8 and a Lancet paper on ‘convergence in health’9 shed light on how poverty and income levels are defined and provide insight into the shortcomings of such definitions. The World Bank’s range of income groups and the percentage of the world’s population in each, with changes from 2001 to 2011 are shown in Figure from the recent Pew Report. The extremely poor live on <$2 per day, in what has been defined as ‘a condition characterized by severe deprivation of basic human needs, including food, safe drinking water, sanitation facilities, health, shelter, education and information.’ This is the group at which ‘poverty eradication’ is aimed. Many in all the groups above this are clustered at the lower end of these higher ranges of income. I suggest it is appropriate that we should reflect more deeply on what the standard of living must be like for those living at these levels. What food can they afford and what does their diet comprise? What housing conditions do they live under? To what standard of healthcare do they have access? What level of education can they reach, and what work can they hope for or do, and how could these be improved with new definitions of poverty and more vigorous attempts to alleviate the associated problems?

Figure.

Distribution of Global Income or Consumption 2001-2011 (From Pew Research Centre Report8).

It can be seen from Figure that all the changes in distribution across income levels between 2001 and 2011 could have been achieved by daily per capita income increments of as less than US$1-3 at the upper end of each category. These increases do shift many into the lower part of the range in the next-highest category. However, such ‘economic advancement’ cannot be credibly labeled as ‘lifting out of poverty,’ other than in terms of the ludicrously low levels of income considered as poverty by the World Bank. While there have also been improvements in some lower common denominator measures of health, such as death rates, these improvements are not remotely sufficient to support optimism about ‘global convergence’ in wealth and health outcomes.9 Such optimistic but evasive thinking justifies ‘feel good’ attitudes, but prevents us from recognizing the gravity of the continuing wide disparities in health under these circumstances and from acknowledging the causal role of powerful, socially constructed forces.10,11

These forces, inter alia include the ideology that promotes neoliberal economic policies, and their progressive legal entrenchment in trade rules and other exploitative processes that (i) sustain pervasive poverty, (ii) prevent the development of healthcare systems capable of limiting emerging new infectious diseases and epidemics,12 and (iii) contribute to internecine conflict with massive displacement of people and large numbers of refugees. These, and other complex 21st-century global crises such as climate change, environmental degradation, the global economic crisis and crises in food, water and energy security will shape the future of all globally.1,13,14 It is arguable that new definitions of poverty are required to drive more intensive alleviation processes that have greater potential for ‘eradicating poverty in all its forms’ and improving global health.15

Global Health: Terminology

Global health is not the same as international health. The latter focuses on providing assistance with healthcare (often paternalistically) by health personnel or organizations from some (usually wealthy) nations to others (usually poor) across national or regional boundaries. International health work is thus an extension of a charitable, superior, ideologically inspired, individualistic, and biomedical conception of modern medical care of individuals and associated public health measures.16

The historical antecedents of ‘global health’ activities began with colonial medicine in the 18th and 19th centuries, when international travel made conquest possible and enabled the foreign expansion of industry and extractive processes to increase the wealth and power of colonising nations. Tropical disease medicine then followed in the early 20th century when advances in medicine and the development of the disciplines of bacteriology, parasitology, helminthology and drugs to treat these infestations/infections enhanced the security of foreign powers through improved control of infectious diseases. International health activities expanded and changed in the mid 20th century when infectious diseases were largely controlled in wealthy countries. A range of co-operative endeavours were then implemented to promote and improve health in low- and middle-income countries.17

This trajectory of interest in health around the world should also be viewed in the context of several hundred years of development. Economic, scientific and technological advances have changed human life more than ever in the past, benefiting some people greatly and many more very little,1 with some profoundly adverse implications for the future of us all. Over recent years slippage in terminology from international health to ‘global health,’ without defining any change in content of global health activities (other than new global funding mechanisms), has bred confusion.18,19 The recent leap from this inadequate conception of global health to use of the term ‘planetary health’20 disingenuously claimed to offer the new insight of a healthy planet as essential for human health, while others whose work was not acknowledged have repeatedly articulated this in the past.21-26

Global (Planetary) Health: Belief Systems, Frames and Metaphors

In the context of the health implications of climate change and environmental degradation,27 new ideas and action are required to ensure meaningful progress in the health of whole populations and the sustainability of life on our planet.28

How we view, think about and act on threats to global health critically depends on our belief system that influences how we view ourselves, the world in which we live, to what kind of future world we aspire, and what we consider to be the most appropriate research agenda for the pursuit of such goals.Whichever view is held, or what balance between them is achieved, will influence what action is considered to be necessary. All belief systems mobilize feelings and motivations through symbols that work most powerfully when subliminal. What is believed becomes an important aspect of ‘reality’ whether true or not and this applies both to religious and secular belief systems.29,30

Frames are mental structures with mostly subconscious reference points that determine automatically and repetitiously how knowledge is constructed and debated. They allow us to create what we take to be reality and to facilitate our most basic interactions with the world by structuring our ideas and concepts, shaping the way we reason and impacting on how we perceive and how we act. Cognitive bias refers to systematic patterns of deviation from norms of judgment, whereby inferences about other people and situations may be drawn through subjective perception of our own social reality. Metaphors are additional fundamental mechanisms of mind that through indirect comparisons subtly shape our perceptions and structure our most basic understandings of our experience and actions.31

The contemporary dominant belief system and its frames for global thinking are characterized by an emphasis on individualism, freedom, philanthropy and an economy dominated by market considerations, all of which give priority to monetary value and short-term interests in all aspects of life. This is the backdrop that explains the failure to prevent the recent devastating Ebola epidemic, despite ample warnings from previous smaller Ebola and other infectious disease outbreaks, and many think-tank commissions.32

In addition, a narrow version of Human Rights discourse, focused on civil and political rights, has become the favored moral compass in secular societies, with little reference to the full range of rights implicit in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and no use of other rich moral languages such as those of solidarity, virtue and character.33 It should also be noted that as the achievement of most of the Human Rights referred to in the UDHR is dependent on access to material resources, these Rights are increasingly difficult to achieve in the face of wide economic disparities. Moreover focusing on individual perpetrators and individual victims of ‘human rights abuses’ ignores the vastly greater contribution of flawed systems to the failure to achieve Human Rights more widely for whole populations of people.34

The best-known metaphor in healthcare is war against disease and this is framed within scientific innovation, competitiveness and the ‘right’ to health/healthcare. These combative and technological metaphors and frames are extrapolated to global health and buttressed by linking health to competitive economic growth as development, and to an adversarial notion of ethics (Human Rights). Such ways of thinking have been described as ‘the common sense’ of dominant practices that need to be critically re-evaluated and replaced with a new paradigm.35

Challenging the Dominant Belief System and Framing

The quality of life enjoyed by, and the ongoing expectations of, the 20% of people in the world who consume 80% of the world’s energy and resources, breed reluctance to admit that our current global ecological and health predicaments are to a considerable extent attributable to endless entitlements and wasteful consumption patterns. This reluctance is supported by the popular notion that more philanthropy and new technology should have the highest priority to overcome current crises.36 Such features of the lives of the privileged and powerful also generate neglect and denial of the need for the paradigmatic change needed to restructure power relations in ways that could achieve solutions potentially within our grasp.37,38

In challenging the dominant discourse and agenda for improving global health it is suggested that the major impetus to the ‘progress’ that has led to only about 20% of people in the world having desirable lifestyles arises not only from the invisibility of power structures but more especially from the invisibility of the belief system wherein power is embedded and that determines the way we think and how we frame our ideas, values, and actions [1] .30,39

The recent Lancet-University of Oslo Commission on governance for global health40 is a prominent example of an insightful but incomplete and largely technical diagnosis of global health problems. The Report’s failure to make appropriate recommendations for progress can be explained by its ignoring the underlying economic and political values and forces that shape the ideological, intellectual and research frameworks of global health and its governance, and that underpin the underlying causal processes of health disparities.38,41 Those who benefit from this belief system have the privilege and the power to drive or support political agendas that preserve their privilege. Indeed, the global health discourse agenda has been captured and held hostage by those with the most power.42,43

However, it has also been proposed that it is not so much our belief system and values that are at fault, but rather our distortions of many highly prized constituent values within our belief system,44,45 and our lack of moral imagination26 that contribute to failure to rectify some of the forces that promote and sustain major inequalities in the determinants of global health. The dominant and dominating mind-set of the most privileged people in the world tends to lock us into our particular utopian realms of thinking and action that must surely seem mysterious, untrustworthy and irremediable to those whose lives remain severely restricted by socially constructed causes of poverty and lack of opportunities to flourish.46

In their collaborative study on framing global health McInnes and colleagues have used a constructivist theoretical approach to examine both the ideational and the material bases behind contemporary debates and controversies in the discourses about global health.47 It is surprising that a social constructivist approach, based on a combination of ideational considerations and material conditions, yields such a restricted range of frames as they describe. This shortcoming can be attributed to the fact that such frames, like those proposed by others,48,49 have been developed only from the perspective of the dominant belief system within a social world where the privileged minority lives with high consumption patterns in what has been called a ‘market civilization’ ideology.42 Such a belief system, presumed to be universal, underplays the pathophysiology and effects of the exploitation and discrimination associated with the materially impoverished lives of billions of people, and ignores the varied alternative belief systems within which other ideational biases could arise.

It is legitimate to imagine that in other contexts very different notions of global health could be influenced by socially constructed systems, powerfully shaped by different beliefs. For example dystopic belief systems can arise from feelings of neglect, hopelessness, lack of empowerment, and social violence fueled by hypocrisy, arrogance, corruption, and exploitation.50-52 More optimistic traditional belief systems with their own powerful heuristic influences, as explored elsewhere, cannot be ignored.53,54 It is also possible that the methodology of an inter-philosophies dialogue55 could facilitate a constructive tension capable of modifying the dominant perspective that seems increasingly out of touch with the limits of economic growth and other dangers at a time when human activity threatens planetary sustainability.56

Global/Planetary Health as a Desirable Belief System and Frame

It is now widely accepted that human activity (population growth and consumption patterns) contributes to climate change, environmental degradation and loss of biological diversity, all of which are already posing profound risks to health and all life that disproportionately affect the poorest, as exemplified by the emergence and spread of new zoonotic disease. Such dangers cannot be corrected with outdated highly individualistic ways of thinking.57 Today’s challenge is to replace the current meaning of ‘global health’ with a concept of global/planetary health long perceived as a more complex notion.1,21

Global health, appropriately understood as an ecocentric concept, embraces the idea of healthy people on a healthy planet. This notion goes beyond anthropocentric considerations on health to include the importance of the interconnectedness of all life-forms and human well-being on an ecologically threatened planet.14,58,59 Prominent values and frames within this system would include a deep sense of physical, moral and spiritual interdependence with nature (animals, plants and the ecological system) that sustains all life, and a spirit of solidarity, co-operation, sharing and social responsibility that respects the public commons and future generations.60

These dimensions of global health have not yet been adequately acknowledged in an era of high technology medicine where progress is increasingly focused on genomics and personalized medicine. Short sighted and self-interested satisfaction with medical progress and with what is being done for the poor, together with glib statements about ‘convergence of health within one generation,’ obstruct achievement of a much needed 21st century paradigm shift to the more complex framing of an ecological and systems conception of global social justice and global health,45,61 pursued through governance under more effective democratic control.62 Addressing such issues lies at the heart of developing sustainability as a more apt metaphor than sustainable development for improving health in the 21st century.63 Some thoughtful and penetrating frameworks for policies to achieve new ambitious goals have been outlined.38,62,64 These should be the starting points for visionary research and ambitious collaboration in taking effective action to avert the tragedies visible on the horizon that are already becoming manifest.65

Conclusions

Contemplation of health and how it could be improved within the above, broadened perspective requires historical insight into the implications of perpetuating current upstream causal processes that are compromising global/planetary health and destroying the resilience of our natural environment on which all life is crucially dependent. Lessons need to be learned from the collapse of civilizations that have flourished and declined – not least because of a variety of human behavioral excesses.66,67 It is unlikely that sufficient progress can be made in the health of whole populations globally without some changes to how the global political economy operates, promotion of more sustainable consumption patterns, new resource distributive mechanisms and conceptions of power such as co-operative ‘power with,’ instead of coercive ‘power over’ that could enhance mutually beneficial endeavors.68 This will require a major global shift towards a more uniformly held ecocentric belief system - a prospect that seems unlikely given human nature but is arguably essential.At the very least such an agenda is deserving of the attention of scholars and concerned citizens of the world.

Acknowledgements

Helpful comments by anonymous reviewers are acknowledged with thanks.

Ethical issues

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Author declares that he has no competing interests.

Author’s contribution

SB is the single author of the paper.

Endnote

[1] I use the terms ‘we’ and ‘us’ to refer to those who use dominant and powerful ways of thinking.

Citation: Benatar S. Politics, Power, poverty and global health: systems and frames. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2016;5(10):599–604. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2016.101

References

- 1.Benatar SR. Global disparities in health and human rights: a critical commentary. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:295–300. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.2.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Global Burden of Diseases. World Health Organization website. http://www.who.int/topics/global_burden_of_disease/en/.

- 3.Shiffman J. Knowledge, moral claims and the exercise of power in global health. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3(6):297–299. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee K. Revealing power in truth: Comment on “Knowledge, moral claims and the exercise of power in global health. ” Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(4):257–259. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rushton S. The politics of researching global health politics: Comment on “Knowledge, moral claims and the exercise of power in global health. ” Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(5):311–314. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ooms G. Navigating between stealth advocacy and unconscious dogmatism: the challenge of researching the norms, politics and power of global health. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(10):641–644. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forman L. The ghost is the machine: how can we visibilize the unseen norms and power of global health? Comment on “Navigating between stealth advocacy and unconscious dogmatism: the challenge of researching the norms, politics and power of global health. ” Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;5(3):197–199. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kochhar R. A global middle class is more promise than reality: from 2001 to 2011, nearly 700 million step out of poverty, but most only barely. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2015. http://www.pewglobal.org/2015/07/08/a-global-middle-class-is-more-promise-than-reality. Accessed January 21, 2016.

- 9.Jamison DT, Summers LH, Alleyne G. et al. Global health 2035: a world converging within a generation. Lancet. 2013;382(9908):1898–1955. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Farmer P. Pathologies of Power: Health, Human Rights, and the New War on the Poor. California: University of California Press; 2003.

- 11. Gill S, Bakker I. The global crisis and global health. In: Benatar S, Brock G, eds. Global Health and Global Health Ethics. Cambridge: CUP; 2011:221-238.

- 12. Garret L. Ebola’s lessons: How the WHO Mishandled the Crisis. Foreign Affairs. 2015. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/west-africa/2015-08-18/ebolas-lessons. Accessed January 28, 2016.

- 13. Gill S, ed. The Global Crisis & the Crisis of Global Leadership. Cambridge: CUP; 2011.

- 14. Benatar S, Brock G. Global Health and Global Health Ethics. Cambridge: CUP; 2011.

- 15.Benatar SR. The poverty of the concept of poverty alleviation. S Afr Med J. 2016;106(1):16–17. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i1.10417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fidler D. After the revolution. Global Health Politics in a Time of Economic Crisis and Threatening Future Trends. Global Health Governance 2009;2(2). http://www.ghgj.org/fidler2.2afterrevoluton.htm.

- 17. Pinto AD, Upshur REG, eds. An Introduction to Global Health Ethics. London: Routledge; 2013.

- 18.Brown TM, Cueto M, Fee E. Public health then and now. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:62–72. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.050831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Macfarlane SB, Jacobs M, Kaaya EE. In the name of global health: trends in academic institutions. J Public Health Policy. 2008;19:383–401. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2008.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whitmee S, Haines A, Beyrer C. et al. Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch: report of The Rockefeller Foundation-Lancet Commission on planetary health. Lancet. 2015;386(10007):1973–2028. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60901-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Potter VR. Bioethics: Bridge to the Future. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1971.

- 22. Garrett L. The Coming Plague: Newly Emerging Diseases in a World out of Balance. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 1994.

- 23.Benatar SR. The coming catastrophe in international health: an analogy with lung cancer. Int J. 2001;56(4):611–631. doi: 10.2307/40203607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McMichael AJ. Planetary Overload: Global Environmental Change and the Health of the Species. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1993.

- 25.Benatar SR, Daar A, Singer PA. Global health ethics: the rationale for mutual caring. Int Aff. 2003;79:107–138. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benatar SR. Moral imagination: the missing component in global health. PLoS Med. 2005;2(12):e400. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Friel S, Butler C, McMichael A. Climate change and health: risks and inequities. In: Benatar S, Brock G, eds. Global Health and Global Health Ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2011: 198-209.

- 28. Birn AE. Addressing the societal determinants of health: the key global health ethics imperative of our times. In: Benatar S, Brock G, eds. Global Health and Global Health Ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2011:37-52.

- 29. Smart N. Worldviews: Cross-Cultural Explorations of Human Beliefs. 2nd ed. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall; 1995.

- 30. Lewontin RC. Science as Ideology: the Doctrine of DNA. Concord, Ontario: Massey Lectures Anansi Press; 1991.

- 31. Lakoff G, Johnson M. The metaphors We Live by. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1980.

- 32.Smith MJ, Upshur REG. Ebola and lessons learned from moral failures: Who cares about ethics? Public Health Ethics. 2015 doi: 10.1093/phe/phv028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Benatar SR. Annual Human Rights Lecture, University of Alberta. http://www.globaled.ualberta.ca/en/VisitingLectureshipinHumanRights/20102011SolomonBenatar.aspx. Accessed July 21, 2016.

- 34.Benatar SR, Doyal L. Human rights abuses: toward balancing two perspectives. Int J Health Serv. 2009;39(1):139–159. doi: 10.2190/HS.39.1.g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bakker I, Gill S. Towards a New Common Sense: the Need for New Paradigms of Global Health. In: Benatar S, Brock G, eds. Global Health and Global Health Ethics. Cambridge: CUP; 2011:329-332.

- 36. Daar AS, Singer PA. The grandest challenge: taking life-saving science from lab to village. Canada: Anchor; 2013.

- 37.Benatar SR. Explaining and responding to the Ebola epidemic. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2015;10:5. doi: 10.1186/s13010-015-0027-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gill S, Benatar SR. Global Health Governance and Global Power: A Critical Commentary on the Lancet-University of Oslo Commission Report. Int J Health Serv. 2016;462:346–365. doi: 10.1177/0020731416631734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Social constructivism. Encyclopedia website. http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Social_constructionism.aspx.

- 40.Ottersen OP, Dasgupta J, Blouin C. et al. The political origins of health inequity: prospects for change. Lancet. 2014;383(9917):630–667. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62407-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McCoy D. The Lancet-University of Oslo Commission on Global Governance for health commissioners should withdraw their recommendations and come up with better ones. MEDACT blog. http://www.medact.org/blog/david-mccoy-lancet-commission/. Published April 22, 2014.

- 42.Gill S. Globalisation, market civilisation and disciplinary neoliberalism. Millennium: Journal of International Studies. 1995;23(3):399–423. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crane JT. Unequal ‘partners’ AIDS, academia and the rise of global health. Behemoth: A Journal on Civilization. 2010;3(3):78–97. doi: 10.1524/behe.2010.0021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benatar SR. Global justice and health: re-examining our values. Bioethics. 2013;27(6):297–304. doi: 10.1111/bioe.12033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Benatar SR. Global leadership, ethics and global health: the search for new paradigms. In: Gill S, ed. The Global Crisis & the Crisis of Global Leadership. Cambridge: CUP; 2011.

- 46.Ooms G. Why the West is perceived as being unworthy of cooperation. J Law Med Ethics. 2010;38(3):594–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2010.00514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McInnes C, Kamradt-Scott A, Lee K. et al. Framing global health: the governance challenge. Glob Public Health. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S83–S94. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2012.733949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stuckler D, McKee M. Five metaphors for global health. Lancet. 2008;372(9633):95–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61013-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Labonte R, Gagnon M L. Framing health and foreign policy: lessons for global health diplomacy. Global Health. 2010;6:14. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-6-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Orwell G. Nineteen Eighty Four. London: Penguin; 1954.

- 51. Bradbury R. Fahrenheit 451. New York: Ballantyne Books; 1953.

- 52. Sicoe V. Utopia and Dystopia – The Many Faces of the Future. http://www.veronicasicoe.com/blog/2013/04/utopia-and-dystopia-the-many-faces-of-the-future/. Accessed July 21, 2016. Published April 15, 2013.

- 53.Escobar A. Beyond the third world: imperial globality, global coloniality and anti-globalization social movements. Third World Q. 2004;25(1):207–230. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Morito B. An Ethic of Mutual Respect: The Covenant Chain and Aboriginal-Crown Relations. Vancouver: UBC Press; 2012.

- 55. Benatar SR, Diabes I, Tomsons S. Inter-philosophies dialogue: creating a paradigm for global health ethics. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal 2016; forthcoming. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Steffen W, Richardson K, Rockström J. et al. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science. 2015;347(6223) doi: 10.1126/science.1259855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Benatar SR, Fox RC. Meeting threats to global health: a call for American leadership. Perspect Biol Med. 2005;48(3):344–361. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2005.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Benatar D. Animals the environment and global health. In: Benatar S, Brock G, eds. Global Health and Global Health Ethics. Cambridge: CUP; 2011:210-220.

- 59. Martens P. Climate Change and Health. Oxford: Earthscan Books; 1998.

- 60. Encyclical letter ‘Laudato Si’ of the Holy Father Francis: On care for our common home. https://laudatosi.com/watch.

- 61. Benatar S, Upshur R. What is global health? In: Benatar S, Brock G, Eds. Global Health and Global Health Ethics. Cambridge: CUP; 2011:13-23.

- 62. Baudet J, ed. Building a world community. Globalization and the common good. Copenhagen, Royal Danish Foreign Ministry for Foreign Affairs: Washington University Press; 2001.

- 63.Bensimon CA, Benatar SR. Developing sustainability: a new metaphor for progress. Theor Med Bioeth. 2006;27(1):59–79. doi: 10.1007/s11017-005-5754-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Atkinson A. Inequality: What Can Be Done? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2015.

- 65.Oreskes N, Conway EM. 2013 The collapse of western civilization: a view from the future. Daedalus. 2013;142(1):40–58. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Diamond J. Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. New York: Penguin; 2005.

- 67. Wright R. A Short History of Progress. Toronto: Anansi Press; 2004.

- 68.Gaventa J. Finding the spaces for change: a power analysis. IDS Bulletin. 2006;37(6):23–33. [Google Scholar]