Abstract

Podocyte depletion is sufficient for the development of numerous glomerular diseases and can be absolute (loss of podocytes) or relative (reduced number of podocytes per volume of glomerulus). Commonly used methods to quantify podocyte depletion introduce bias, whereas gold standard stereologic methodologies are time consuming and impractical. We developed a novel approach for assessing podocyte depletion in whole glomeruli that combines immunofluorescence, optical clearing, confocal microscopy, and three-dimensional analysis. We validated this method in a transgenic mouse model of selective podocyte depletion, in which we determined dose-dependent alterations in several quantitative indices of podocyte depletion. This new approach provides a quantitative tool for the comprehensive and time-efficient analysis of podocyte depletion in whole glomeruli.

Keywords: podocyte, renal morphology, glomerular disease

Podocytes are essential components of the glomerular filtration barrier.1 Despite fulfilling multiple key roles, podocytes are terminally differentiated and incapable of completing successful cell division under normal conditions.2 Multiple studies have shown that podocyte depletion, defined as a reduction in total podocyte number and/or podocyte density (number per volume of glomerulus), is sufficient for the development of progressive kidney disease.3,4 Thus, the podocyte depletion hypothesis has become a unifying principle of glomerular disease.5,6

The most commonly used method for the assessment of podocyte depletion is fast and simple, and it involves counting of podocyte nuclei per glomerular cross-section in standard histologic sections.7 Recent studies have highlighted the multiple limitations of this approach,8–11 including low levels of accuracy and precision. Furthermore, podocyte depletion indices have a high degree of biologic variability that is particularly relevant for studies conducted in mice. To illustrate this point, a comparison between podocyte depletion in humans and mice is warranted. Although adult human glomeruli contain approximately 600 podocytes each,12,13 adult mouse glomeruli contain only 70–75 podocytes.14,15 This difference highlights an important issue: 20% podocyte depletion in humans involves the loss of 120 podocytes but the loss of only 14–15 podocytes for mice. To detect such small differences in podocyte numbers in mouse models, a method with high accuracy and precision is required. Therefore, the methodology used to define podocyte depletion has a significant effect on the generation of data and interpretation of results.

A range of stereologic methods has been used to count podocytes. These can be classified as model-based methods and design-based (unbiased) methods.10 In both cases, estimates of podocyte number are obtained by making measurements on sampled sections and then, calculating the real number. Model-based methods require knowledge or assumptions of the geometry of the object being counted (in this case, podocyte nuclei), and to the extent that these assumptions are incorrect, the final data will be biased. Design-based methods do not require geometric assumptions, but they tend to be time consuming and therefore, have been used by relatively few laboratories.

An alternate approach for counting podocytes involves the counting of every podocyte in glomeruli. Lemley et al.10 refer to this as “exhaustive enumeration.” Traditionally, such approaches have been extremely tedious and time consuming, involving counting and identification of podocyte nuclei in serial histologic sections. However, with the advent of optical sectioning via confocal and multiphoton microscopy in combination with new tissue clearing techniques, exhaustive enumeration is potentially an attractive approach for counting podocytes. Here, we present a novel and time-efficient approach to study podocyte depletion using a combination of immunofluorescence, optical clearing, confocal microscopy, and three-dimensional (3D) analysis. We used this technique to quantify features of podocyte depletion in a transgenic mouse that expresses the human diphtheria toxin (DT) receptor constitutively in podocytes, which allows conditional and dose–dependent podocyte death. This novel approach provides a unique quantitative morphologic tool, significantly improves the assessment of podocyte depletion, and for the first time, allows the study of whole glomeruli across the renal cortex. Differences in podocyte depletion between glomeruli in individual kidneys can be detected, which is a significant advance in the study of focal glomerular diseases.

Results

Mouse Model of Podocyte Depletion

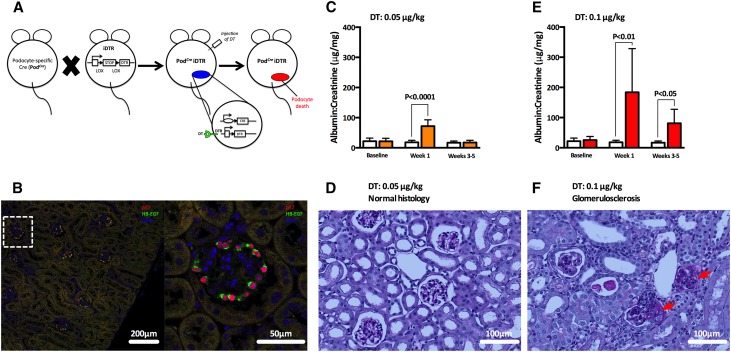

A transgenic mouse model expressing the human DT receptor under the podocin promoter (PodCreiDTR)16,17 was generated by crossbreeding homozygote iDTR males with heterozygote Podocin-Cre (PodCre) females (Figure 1A). The expression of human DT receptor, also known as heparin–binding EGF, was detected exclusively in podocytes by immunofluorescence (Figure 1B). The injection of 0.05 μg/kg DT induced reversible elevations in the albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) (Figure 1C), with no observable change in glomerular histology (Figure 1D). In contrast, a dose of 0.1 μg/kg DT induced persistent changes in ACR (Figure 1E) with the occasional presence of segmental glomerulosclerosis (Figure 1F), confirming a working model of podocyte deletion.

Figure 1.

Transgenic mouse model of conditional podocyte depletion. (A) Development of PodCreiDTR mice to induce conditional podocyte depletion after DT injection. (B) Immunofluorescence expression of the human DT receptor, also known as heparin-binding EGF (HB-EGF), exclusively in glomerular podocytes, which was confirmed by double labeling of the HB-EGF (green) and a podocyte-specific marker (p57; red). (C) Mild podocyte depletion was achieved by the injection of 0.05 μg/kg DT, (D) inducing reversible albuminuria but no histologic signs of glomerular disease. (E) Moderate podocyte depletion was achieved by the injection of 0.1 μg/kg DT, (F) inducing persistent albuminuria and in some cases, the development of glomerulosclerosis (red arrows). Bars (orange, mild depletion; red, moderate depletion; white, controls) represent means±SDs.

A Novel Method to Image and Quantify Podocyte Depletion

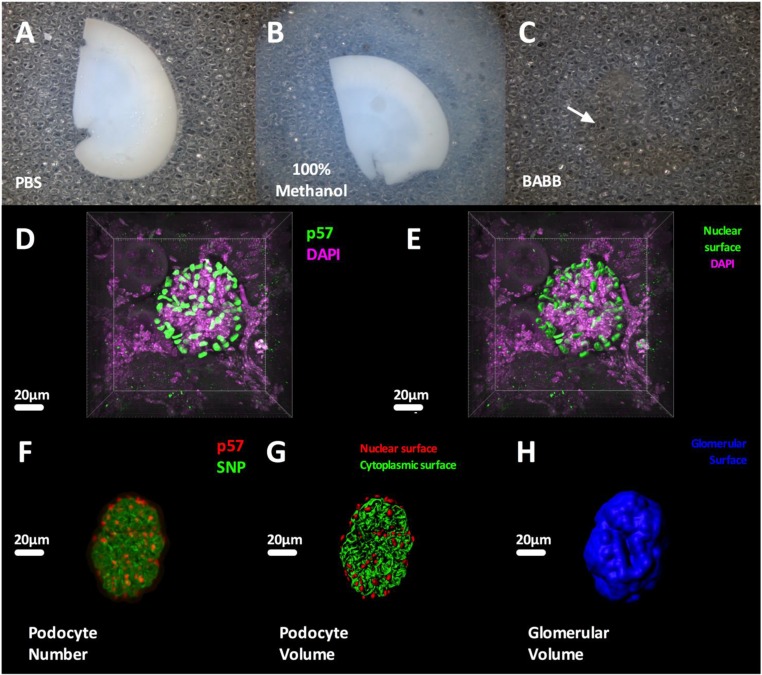

To image multiple whole glomeruli, 800-μm-thick formalin–fixed kidney slices were subjected to 1 hour of antigen retrieval and a modified immunofluorescence protocol (Concise Methods). Optical clearing of the fluorescently labeled tissue was performed by serial steps of agarose embedding (PBS) (Figure 2A), dehydration in 100% methanol (Figure 2B), and clearing in benzyl alcohol, benzyl benzoate (BABB), which renders the kidney slices translucent (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Optical clearing, confocal microscopy, and 3D rendering of whole glomeruli. Optical clearing is performed in sequential steps. (A) Agarose-embedded tissue is placed in (B) 100% methanol, which dehydrates both the tissue and the agarose, and (C) BABB allows efficient tissue clearing (white arrow shows the location of the tissue). (D) A 3D reconstruction of a whole-mouse glomerulus showing all nuclei (DAPI; magenta) and podocyte nuclei (p57; green), which are shown as surfaces in E, highlighting the potential for both manual and semiautomated quantification. (F) A 3D reconstruction of a whole-mouse glomerulus showing podocyte nuclei (p57; red) and cytoplasm (SNP; green). (G) Podocyte nuclear and cytoplasmic surfaces are shown, highlighting the capability for semiautomated quantification of podocyte nuclear and cytoplasmic volumes. (H) Glomerular volume obtained as a volumetric dilation on the basis of podocyte cytoplasmic surfaces. All analyses were performed using Imaris (Bitplane AG).

The first attempt to image cellular detail in whole glomeruli was performed on an inverted confocal microscope (Model SP5; Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL) fitted with a 40× oil objective lens (numerical aperture: 1.25) to match the refractive index of BABB (1.56) (Supplemental Video 1). Although this approach provided excellent resolution, this 40× objective lens had a limited working distance (100 μm). As a result, only the smallest glomeruli could be completely imaged and analyzed, providing a biased sample. Moreover, this objective lens did not allow high-throughput sampling of glomeruli.

To improve the imaging depth and obtain an unbiased sample of whole glomeruli, an upright confocal microscope (Model SP8; Leica Microsystems) fitted with a BABB objective lens (numerical aperture: 0.95; Leica Microsystems) with a much larger working distance (1950 μm) was used. Kidneys were stained with synaptopodin (SNP) (podocyte cytoplasmic marker in green in Supplemental Video 2) and p57 (podocyte nuclear marker in red in Supplemental Video 2). All analyzed glomeruli were systematically sampled across the renal cortex from superficial to juxtamedullary regions. In this manner, glomerular sampling was unbiased, such that both large and small glomeruli had equivalent chances of being imaged, regardless of cortical location.

As an example, p57, DAPI, and SNP markers were used to identify podocytes in full–thickness confocal 3D datasets of glomeruli at 1-μm intervals (Figure 2D). Podocyte nuclei could be individually quantified by generating surfaces for p57-stained nuclei (Figure 2E) using Imaris software (Bitplane AG, Geneva, Switzerland) (Supplemental Figure 1). This method was then used to analyze total podocyte number (Figure 2F) and volume (nuclei and cytoplasm) (Figure 2G). Individual glomerular volume (IGV) was estimated by morphologic dilation (additional details are in Concise Methods) on Imaris (Bitplane AG) using cytoplasmic podocyte volume as a mask and expanding this volume to obtain a 3D reconstruction of the whole glomerulus (Figure 2H). For each glomerulus, we also calculated podocyte density (total podocyte number divided by IGV), total podocyte volume (the sum of all podocyte cytoplasmic and nuclear volumes), and average podocyte volume (total podocyte volume divided by total podocyte number per glomerulus). We counted the total number of podocytes per glomerulus for 20 glomeruli per mouse (minimum), with an average manual counting time of 2 minutes per glomerulus. An additional 5 minutes were required to estimate podocyte volume and density metrics per glomerulus, which were determined after analyzing 10 glomeruli (minimum) per mouse. Although this last subset of glomeruli was randomly selected to avoid the introduction of methodological bias, we also compared total podocyte number per glomerulus in the subsampled glomeruli to determine if our selection had provided a representative glomerular population (Supplemental Figure 2).

Definition of Absolute Podocyte Depletion

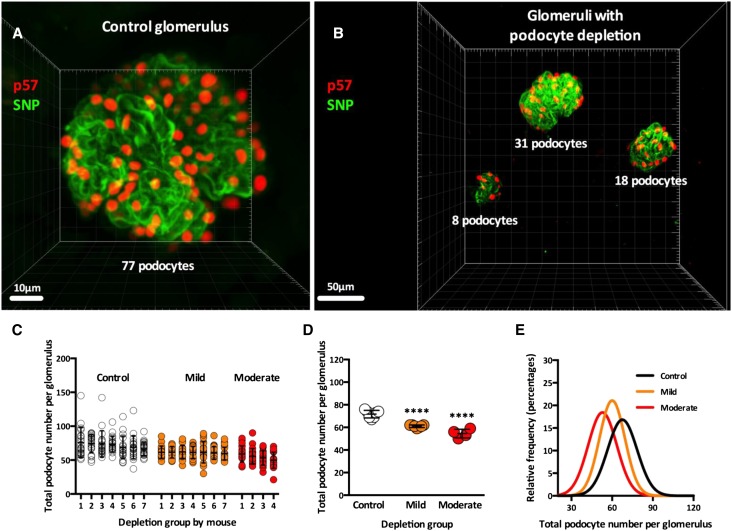

We observed no difference in total podocyte number per glomerulus between noninjected PodCreiDTR mice and DT–injected iDTR mice (Supplemental Figure 3), thereby confirming that DT injection in mice without Cre expression did not lead to podocyte depletion. For this reason, both noninjected PodCreiDTR mice and DT–injected iDTR mice were used as controls and compared with PodCreiDTR mice injected with either a mild or moderate dose of DT (0.05 and 0.1 μg/kg, respectively). Glomeruli from control kidneys (Figure 3A) visually contrasted with those from moderate DT–injected kidneys (Figure 3B). Total podocyte number per glomerulus in control mice ranged from 37 to 145 (mean =71.7±16.2) compared with 30–89 (mean =61.1±10.1) in PodCreiDTR mice administered 0.05 μg/kg DT and 21–90 (mean =54.3±11.7) in PodCreiDTR mice administered 0.1 μg/kg DT (Figure 3C). Additional details related to variation of podocyte depletion indices within mice (SDs, coefficients of variation, and variances) are shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Figure 3.

Absolute podocyte depletion in whole glomeruli. (A) A 3D reconstruction of one control glomerulus using p57 (red) and SNP (green). (B) A 3D reconstruction of three glomeruli with variable degrees of podocyte depletion using p57 (red) and SNP (green). (C) Total podocyte number per glomerulus by mouse and depletion group; each column represents one mouse with 20 analyzed glomeruli. (D) Total podocyte number per glomerulus by depletion group; each column represents one depletion group, and each circle represents the average of 20 glomeruli per mouse. White circles represent controls, orange circles represent mild depletion, and red circles represent moderate depletion. (E) Distributions of total podocyte number per glomerulus (relative frequencies) by depletion group. Error lines and bars represent means±SDs. ****P<0.001.

Total podocyte number per glomerulus was significantly reduced in mild (P<0.001) and moderate (P<0.001) depletion groups compared with controls (Figure 3D). The podocyte depletion effect in PodCreiDTR mice was dose dependent, with mice administered 0.1 μg/kg DT having a greater reduction in podocyte number than mice administered 0.05 μg/kg DT (P<0.01). This is supported by the left–shifted frequency distributions of the mild and moderately treated mice when analyzing total podocyte number per glomerulus (Figure 3E).

Numbers of Podocytes in the Context of Glomerular Volume

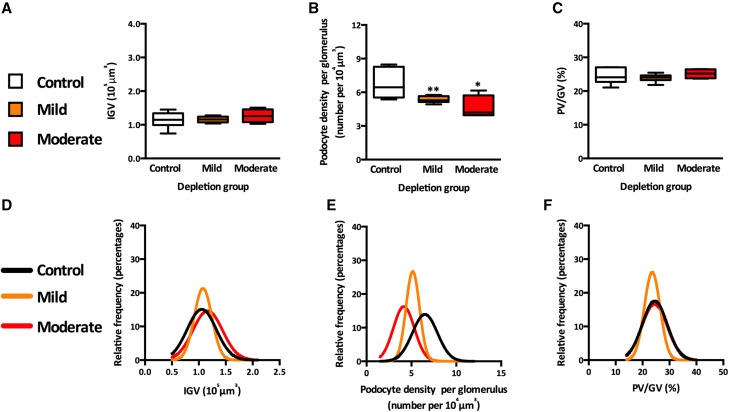

Glomerular volume was not altered by either mild or moderate podocyte depletion (Figure 4A). However, the reductions in total podocyte number per glomerulus lead to significant reductions in podocyte density (Figure 4B) in the two depletion groups compared with controls (P<0.01 for mild depletion and P<0.05 for moderate depletion). Podocyte densities in the mild and moderate depletion groups were similar (P=0.23). The ratio of podocyte volume to glomerular volume was remarkably similar in the three groups (Figure 4C). Although there was strong overlap in the distributions of IGV (Figure 4D) in the three groups, there was a marked left shift in the distributions of podocyte density (Figure 4E) (P<0.001 for each depletion group compared with controls and P<0.001 between depletion groups). There was also significant overlap in the distributions of podocyte volume to glomerular volume in the three groups (Figure 4F).

Figure 4.

Numbers of podocytes in the context of glomerular volume. (A) IGV by depletion group. (B) Podocyte density per glomerulus by depletion group. P values represent differences between depletion category and controls. *P<0.05; **P<0.01. (C) Percentage of podocyte volume-to-glomerular volume ratio (PV/GV) by depletion group. (D) Relative frequency of IGV by depletion group. (E) Relative frequency of podocyte density per glomerulus by depletion group. (F) Relative frequency of PV/GV by depletion group.

Quantitative Analyses of Podocyte Hypertrophy

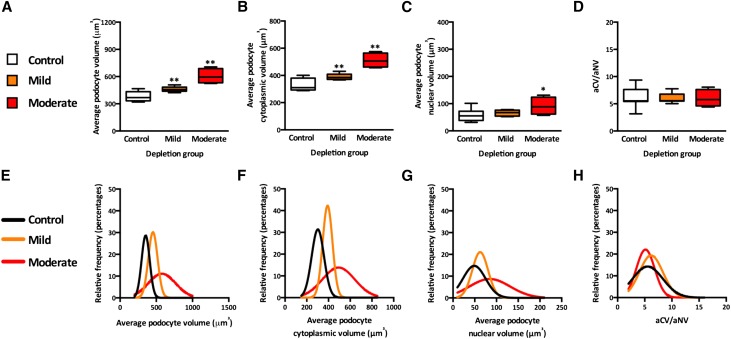

Average podocyte volume was significantly higher in the mild and moderate podocyte depletion groups (Figure 5A) (P<0.01 for both groups) than in controls, with a greater degree of podocyte hypertrophy observed in mice with moderate podocyte depletion than in mice with mild podocyte depletion (P<0.01). The same pattern was observed for the average podocyte cytoplasmic volume (Figure 5B) (P<0.01 for both depletion groups). Interestingly, the average podocyte nuclear volume was higher in the moderate depletion group (P<0.05) but not in the mild depletion group (Figure 5C). Furthermore, the podocyte cytoplasmic-to-nuclear ratio (podocyte cytoplasmic volume to nuclear volume) was similar in the three groups (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

Quantitative analysis of podocyte hypertrophy. (A) Average podocyte volume by depletion group. (B) Average podocyte cytoplasmic volume by depletion group. (C) Average podocyte nuclear volume by depletion group. P values represent differences between depletion category and controls. *P<0.05; **P<0.01. (D) Average cytoplasmic volume-to-average nuclear volume ratio (aCV/aNV) by depletion group. (E) Relative frequency of average podocyte volume by depletion group. (F) Relative frequency of average cytoplasmic volume by depletion group. (G) Relative frequency of average nuclear volume by depletion group. (H) Relative frequency of aCV/aNV by depletion group.

The analysis of frequency distributions confirmed the above findings. We observed a marked right shift in the distributions of average podocyte volume and average cytoplasmic volume (Figures 5, E and F) (P<0.001 for each depletion group compared with controls and P<0.001 between depletion groups). The distribution of average nuclear volume was shifted to the right only in the moderate depletion group (Figure 5G) compared with controls (P<0.001) and the mild depletion group (P<0.001). However, the distribution of average nuclear volume from the mild depletion group was similar to the one from controls (P=0.17). Furthermore, the distributions for the ratio of podocyte cytoplasmic to nuclear volumes were similar in the three groups (Figure 5H).

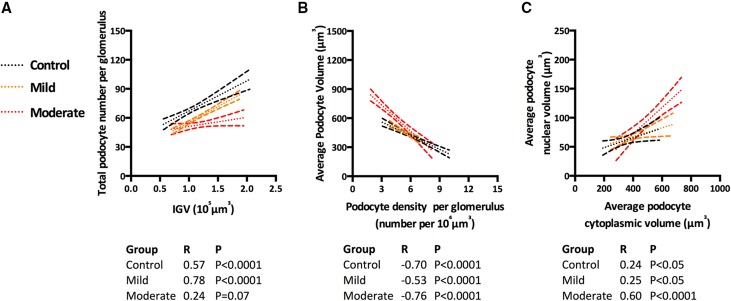

The Use of Associations for the Study of Podocyte Depletion

There was a strong association between total podocyte number per glomerulus and IGV in control mice (Figure 6A) (R=0.57; P<0.001). This association was stronger in mice with mild podocyte depletion (R=0.78; P<0.001) but lost in mice with moderate depletion (R=0.24; P=0.07). Furthermore, strong negative associations between podocyte density per glomerulus and average podocyte volume were observed in all three groups (Figure 6B) (controls [R=−0.70; P<0.001], mild depletion [R=−0.53; P<0.001], and moderate depletion [R=−0.76; P<0.001]). This finding shows that glomeruli with lower podocyte density have larger podocytes, whereas those glomeruli with densely packed podocytes have smaller podocytes. To further analyze podocyte size, the nuclear and cytoplasmic volumes of podocytes were assessed (Figure 6C). We determined that podocytes appear to scale evenly in size, with larger podocyte cytoplasmic volumes being matched with larger nuclear volumes in control (R=0.24; P<0.05), mild depletion (R=0.25; P<0.05), and moderate depletion groups (R=0.60; P<0.001).

Figure 6.

The use of associations for the assessment of podocyte depletion. (A) Associations between total podocyte number and IGV by depletion group. (B) Associations between average podocyte volume and podocyte density per glomerulus by depletion group. (C) Associations between average podocyte nuclear and cytoplasmic volumes by depletion group; lines of best fit with 95% confidence intervals are provided per depletion group.

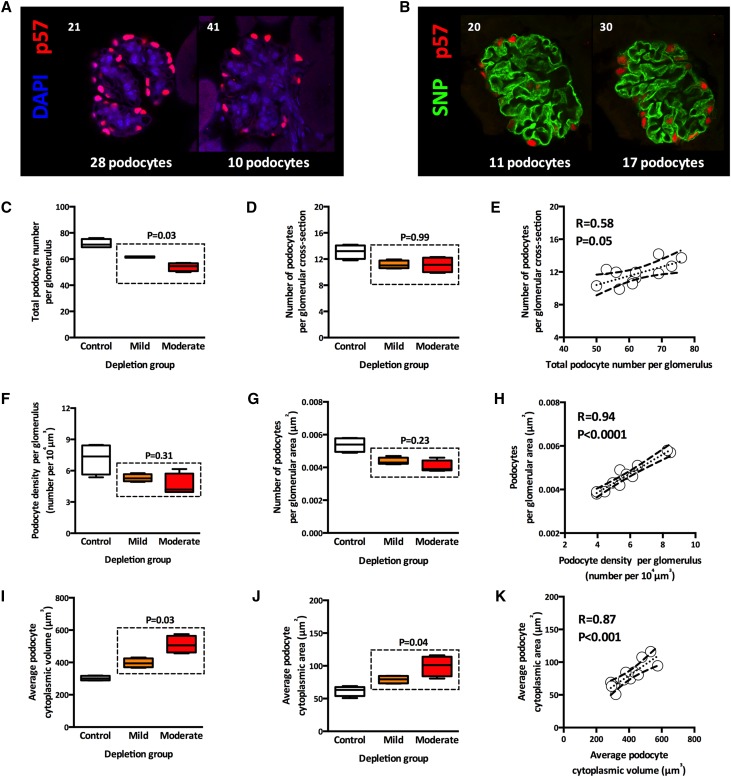

Comparing Two-Dimensional and 3D Estimates of Podocyte Depletion

To compare podocyte depletion indices obtained with traditional histologic (two-dimensional [2D]) methods with those obtained with this new 3D method, we first analyzed optical sections (rather than histologic sections) at various depth (Z) intervals in the kidney slices. When comparing two consecutive sections 20 μm apart (Figure 7A), 28 p57+ podocytes are observed in one section, whereas only 10 p57+ podocytes are present in the neighboring section. This difference is present even if the glomerular cross-sections have comparable areas. When comparing two consecutive sections at 10-μm Z intervals through the same glomerulus (Figure 7B), we find a difference of six p57+ podocytes between the two optical sections. These findings show that 2D counts of podocytes in glomerular cross-sections can provide highly variable numbers.

Figure 7.

From 3D to 2D: what have we learned? (A) Two optical sections from the same glomerulus at 20-μm intervals showing that cross-sections with a similar area from the same glomerulus provide very different numbers of podocytes using p57 (red) and DAPI (blue). (B) Two optical sections from the same glomerulus at 10-μm intervals showing that cross-sections with a similar area from the same glomerulus provide different numbers of podocytes using p57 (red) and SNP (green). (C) Total podocyte number per glomerulus by depletion group. The dotted box highlights the difference between mild and moderate depletion groups. (D) Podocytes per glomerular cross-section by depletion group. The dotted box highlights the similarity between mild and moderate depletion groups. (E) Association between total podocyte number per glomerulus and podocytes per glomerular cross-section. (F) Podocyte density per glomerulus by depletion group. (G) Podocytes per glomerular area by depletion group. (H) Association between podocyte density per glomerulus and podocytes per glomerular area. (I) Average podocyte cytoplasmic volume by depletion group. (J) Average podocyte cytoplasmic area by depletion group. (K) Association between average podocyte cytoplasmic volume and area. Distribution box plots show control (white), mild depletion (orange), and moderate depletion (red) groups; each box contains average values from ≥10 observations per mouse (n=4 mice per group).

We next assessed podocyte depletion using the 2D and 3D methodologies using four mice from each of the three groups. At least 10 glomeruli were analyzed per mouse using our 3D method to obtain total podocyte number per glomerulus, podocyte density per glomerulus, and average podocyte cytoplasmic volume. Each 3D-analyzed glomerulus contained, on average, 60 serial optical sections at 1-μm intervals, which provided an ideal dataset to analyze 2D parameters. We subsampled one optical equatorial section per glomerulus for a total of 15–25 glomerular optical cross–sections per mouse. These sections were used to estimate the number of podocyte nuclei per glomerular cross-section, the number of podocyte nuclei per glomerular area, and the average podocyte cytoplasmic area. Using 3D analysis, we found that glomeruli from mice with mild (P<0.01) and moderate (P<0.01) podocyte depletion contained fewer podocytes per glomerulus than age-matched controls and detected the dose effect between moderate and mild DT (Figure 7C) (P=0.03). Using the 2D approach, the differences in the number of podocytes per glomerular cross-section between control and depletion groups were detected (P<0.05 for both groups), but the dose-dependent effect between mild and moderate depletion groups was not identified (P=0.99) (Figure 7D). Accordingly, there was a weak association between total podocyte number per glomerulus and the number of podocytes per glomerular cross-section (Figure 7E) (R=0.58; P=0.05).

Podocyte density per glomerulus (3D method) (Figure 7F) and the number of podocytes per glomerular area (2D method) (Figure 7G) were significantly reduced in the two depletion groups compared with controls (P<0.05 in both cases). Values for both parameters were similar in the two depletion groups. In this case, there was a strong association between podocyte density per glomerulus and the number of podocytes per glomerular area (Figure 7H) (R=0.94; P<0.001).

Average podocyte cytoplasmic volume (3D method) (Figure 7I) and cytoplasmic area (2D method) (Figure 7J) were significantly increased in the two depletion groups compared with controls (P<0.01 in both cases). Both methods revealed that podocytes from the moderate depletion group were significantly larger than podocytes from the mild depletion group (P=0.03 for 3D analysis and P=0.04 for 2D analysis), and there was a strong association between values for the two parameters (Figure 7K) (R=0.87; P<0.001).

Discussion

This study introduces a novel method for assessing podocyte depletion. The approach provides high–throughput in–depth analysis of whole glomeruli with unprecedented efficiency. There were four main findings of this study. (1) This method provides a novel tool to quantify multiple morphologic parameters of podocyte depletion. (2) Values are obtained for individual whole glomeruli, allowing for the detection of heterogeneity in podocyte metrics between glomeruli, which is important in settings of focal glomerular pathology. (3) Unlike conventional methods, this new approach is able to detect small differences in total podocyte number per glomerulus that were otherwise imperceptible. (4) After image acquisition, all estimates for a single glomerulus can be obtained in approximately 7 minutes.

The last decade has witnessed the development of a range of new imaging modalities, including methods for whole-organ imaging. The major advancement in many of these imaging methods is the application of chemical agents that improve light penetration or transmission through the sample. These new modalities include methods that use BABB,18 Scale,19 3DISCO,20 Clarity,21 ClearT,22 SEEDB,23 PACT/PARS,24 CUBIC,25 and PACT-deCAL/ePACT.26 Our understanding of kidney developmental biology has improved significantly by the application of BABB clearing and OPT imaging27 for the temporal and spatial analysis of ureteric branching morphogenesis in 3D.28,29 Surprisingly, however, the analysis of normal and diseased adult kidneys has not received the same level of attention.

Unlike many other clearing methods,30 this new approach allows the use of optical clearing after tissue immunolabeling without destruction of tissue. In fact, Short et al.28 have reported that, after BABB clearing, the experimental tissue can be reused for additional analysis. An advantage of this method is that it permits the assessment of archival paraffin–embedded tissue samples. Although multiple studies have shown the capability to visualize renal structures,24,25 glomerular quantification at a cellular level has rarely been reported, especially in the context of targeted cell depletion. We postulate that the use of this novel method has the potential to revolutionize quantitative histopathologic analysis in not only the kidney but also, other tissues/organs, where accurate and precise data on cell numbers and density are required.

Our findings show that the glomeruli of healthy adult mice contain approximately 72 podocytes each, which confirms previous observations using design-based stereology.13,14 Importantly, in this study, 25% podocyte depletion in the moderate depletion model implies the loss of 18 podocytes, whereas 15% depletion implies the loss of only 11 podocytes per glomerulus. This means that the method used to define and study podocyte depletion in mice must be highly precise and accurate to obtain reliable results and thereby, draw appropriate conclusions.31 Unlike a 2D approach, our 3D method was able to successfully detect differences in total number of podocytes per glomerulus with a limited sample size of both mice (four mice) and glomeruli (10 per mice). This is a significant strength that is particularly relevant for studies in which podocyte number is a critical parameter.

Recent evidence suggests that progenitor cells residing in the juxtaglomerular apparatus32–34 and Bowman’s capsule35–39 may give rise to podocytes in adult kidneys. However, although state of the art transgenic reporter mouse models have been used to identify possible podocyte progenitors, the methodology used for counting podocytes and progenitor cells has produced conflicting outcomes. If podocyte regeneration is possible, this is likely an inefficient mechanism.40 Therefore, the number of regenerated cells may only be small, highlighting the need to count progenitor cells and new podocytes with accuracy and precision. Such techniques will also be valuable in evaluating new therapeutic interventions for protecting podocytes and driving podocyte regeneration.

Unlike estimates of podocyte number, 2D and 3D approaches provided similar data when assessing podocyte density and volume. Given that 2D approaches are simple to perform, it is tempting to conclude that they are suitable for the study of podocyte depletion.7 Remuzzi et al.41 showed that glomerulosclerosis develops in a segmental pattern, which means that, depending on the sampling region, the same glomerulus can be identified as normal or pathologic. A logical way to minimize this factor is to sample all glomeruli in a similar area: the equatorial region. However, this principle assumes that all glomeruli are of similar size, thereby having similar equatorial regions. Furthermore, it assumes that the distribution of podocytes is consistent within each glomerulus and that the pattern of depletion will evenly affect all regions of the glomerulus. Our study shows that none of these assumptions are true. (1) Glomerular size varies widely within mice, which means that equatorial regions will also have different areas, making them harder to identify. (2) The number of podocytes per glomerular cross-section varies up to 68%, even in cross-sections from the same glomerulus that appear to be of similar sizes. (3) Levels of podocyte depletion cannot be detected using numbers of podocytes per glomerular cross-section, which means that the degree of depletion is not consistent across different areas of the same glomerulus. Therefore, we propose that the use of 2D approaches be discouraged in studies that showcase podocyte depletion as a central component of the experimental design.

We have recently reported an association between glomerular size and total podocyte number in humans, whereby larger glomeruli contain more podocytes.12 Moreover, podocyte density has been proposed as a useful parameter in clinical samples,42–45 because it reflects both podocyte number and glomerular size with an inverse association with podocyte volume. Our study confirms these human observations and validates the use of these clinically relevant parameters in animal models of podocyte depletion. Furthermore, our data provide a detailed description of podocyte volume, including average nuclear and cytoplasmic volumes.

In summary, this is the first description of a method on the basis of whole-glomerular imaging and quantitation that is as methodologically robust as gold standard stereology but much more time efficient. This study introduces a novel method that provides a tool of parameters for assessing podocyte depletion in whole glomeruli.

Concise Methods

Animal Ethics

All animal experiments were conducted in strict accordance with guidelines provided by the Monash University Animal Research Platform (ethics approval no. MARP/2014/015). Male ROSA26iDTR/iDTR and PodCre;ROSA26iDTR/iDTR mice were used for all experiments. All mice were fed an ad libitum diet, and random spot urine collection was performed at selected time points.

Generation and Genotyping of Transgenic Mouse Line

The ROSA26iDTR mouse line was imported from JAX Laboratories. Susan Quaggin (Feinberg Cardiovascular Research Institute) provided the PodCre transgenic mouse line that was originally developed by Moeller et al.46 ROSA26iDTR/iDTR males were crossed with PodCre+/− or PodCre+/+ females. Genotyping in double-transgenic mice was performed by PCR using genomic DNA isolated from tail or ear punch biopsies. The presence of the Cre allele was tested by PCR using the following primer pairs: 5′-gcggtctggcagtaaaaactatc-3′ (Cre-F) and 5′-gtgaaacagcattgctgtcactt-3′ (Cre-R). The presence of an internal control (IL-2) was also examined within the same PCR using the primer pairs 5′-CTAGGCCACAGAATTGAAAGATCT-3′ (IL-2F) and 5′-GTAGGTGGAAATTCTAGCATCATCC-3′ (IL-2R).

DT Administration

The 0.05- and 0.1-μg/kg doses of DT were selected using previous publications as a guide.16,17 For mild depletion, the required concentration of DT was 0.05 μg/ml. A double dilution with low-lipid BSA (A8806; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was done (1:50/1:200 for mild depletion and 1:50/1:100 for moderate depletion). PodCreiDTR and iDTR mice received intraperitoneal injections with doses adjusted for body weight and depletion category. PodCreiDTR mice were euthanized 35 days after DT injection, and iDTR mice were age matched accordingly.

Perfusion Fixation and Tissue Collection

Mice were anesthetized with 100% isoflurane. A midline incision was made in the anterior abdominal wall, and then, an incision was made in the diaphragm and the rib cage, exposing the heart. Mice were then perfused via the heart with 1× PBS followed by 10% formalin. Both kidneys were then removed and immersion fixed in 10% formalin for ≤7 days before tissue processing. Right kidneys were sliced with a series of razor blades evenly spaced at 800 μm. One full–face midhilar tissue slice containing both cortex and medulla was randomly selected for thick-slice immunofluorescence, and the remaining slices were processed and embedded in paraffin for thin-section immunofluorescence.

Thin-Section Immunofluorescence

For immunofluorescence on 4-μm paraffin sections, antigen retrieval was performed using Dako Target Retrieval Solution (S1699; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) on a Dako PT Link Instrument (PT10126; Dako) for 30 minutes at 98°C. Sections were then allowed to cool. A standard immunofluorescence protocol was performed as previously reported.13,47 Briefly, sections were incubated in primary and secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature with five washes with Dako Wash Buffer (K8007; Dako) between each incubation step. After incubation with secondary antibodies, sections were washed five more times with Dako Wash Buffer, and DAPI (1:10,000; D1306; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) was added for 20 minutes. Five final washes were done before coverslipping each section with Prolong Gold (P36934; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Thick-Slice Immunofluorescence

Thick (800-μm) slices were washed extensively in distilled water overnight before the commencement of the immunofluorescence protocol. Antigen retrieval was performed using Dako Target Retrieval Solution (S1699; Dako) on a Dako PT Link Instrument (PT10126; Dako) for 1 hour at 98°C, and then, the slices were left to cool. Slices were then immersed in 400 μl primary antibody solution made up in Dako Antibody Diluent (S0809; Dako) using a polyclonal rabbit anti–mouse p57 antibody (1:200; SC8298; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and a goat anti–mouse SNP antibody (1:400; SC21537; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Then, slices were placed on an orbital shaker (OM8, Ratek, Australia) in this solution at 37°C for 6 days. Slices were then resubmerged in 4 ml Dako Wash Buffer (K8007; Dako) and incubated on an orbital shaker at 37°C for 24 hours. Next, slices were immersed in 400 μl secondary antibody solution made up in Dako Antibody Diluent (S0809; Dako) using a polyclonal donkey anti–rabbit Alexa Fluor 555 (1:200; A31572; Life Technologies) and a polyclonal chicken anti–goat Alexa Fluor 488 (1:400; A2467; Life Technologies) and DAPI (1:10,000; D1306; Life Technologies). Slices were incubated again on an orbital shaker at 37°C for 6 days. Then, slices were resubmerged in 4 ml Dako Wash Buffer and placed on an orbital shaker at 37°C for 24 hours.

Optical Clearing

Slices were placed in a glass petri dish and covered with 2% low–melting point agarose solution in water. Absolute methanol was added to the petri dish and left for a minimum of 2 hours with two to three changes to ensure complete dehydration. After dehydration was achieved, the agarose became opaque, and at this point, methanol was removed from the dish. Working quickly, cyanoacrylate super glue was applied to the borders of the agarose disk to adhere the agarose to the petri dish, indirectly fixing the tissue to the dish. BABB (at a ratio of 1:2 by volume) was then added. Within 2–3 hours, both agarose and tissue were optically cleared (with two to three changes to ensure removal of residual methanol) (Figure 2, A–C).

Confocal Microscopy

Optical images from 4-μm sections were obtained using an inverted Leica SP5 Laser Confocal Microscope (Leica Microsystems) fitted with a 40× objective lens (1.25 numerical aperture) with a variable zoom using sequential imaging for 405, 488, and 555 nm. Representative images were obtained with eight line averages and stored in a 1024×1024-pixel frame.

Several microscopes were used to image the 800-μm kidney slices. At first, we used an inverted Leica SP5 Laser Confocal Microscope (Leica Microsystems) fitted with a 40× objective lens (1.25 numerical aperture). Samples were placed on an in-house–made slide consisting of a 0.5-cm well with a coverslip at the base. This system allowed the use of BABB on the inverted microscope. However, the free working distance of this objective was only 100 μm. Next, Leica SP5/SP8 Multiphoton Microscopes (Leica Microsystems) fitted with 20× BABB objective lens (0.95 numerical aperture; 1950-μm working distance) were used. Serial optical images were obtained at 1-μm intervals and stored in 1024×1024-pixel frames.

3D Quantification of Podocyte Depletion

Fiji imaging software (Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics, Dresden, Germany) was used to move through the z axis of each stack of optical sections. Podocytes were defined as p57+SNP+ cells. The cell counter built–in feature (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/plugins/cell-counter.html) was used to keep track of podocyte nuclear counts while moving through the entire glomerulus (from top to bottom). Quantification of glomerular and podocyte volume was performed using 3D rendering and analysis software: Imaris, version 8 (Bitplane AG). Individual glomeruli were isolated by 3D cropping each stack and matching it to the manual counts. A 3D Gaussian filter was applied to all image stacks to reduce noise across samples. The 3D surfaces module for Imaris was used to segment both podocyte nuclei (p57+) and cytoplasm (SNP+). Automated background subtraction was applied to all stacks (4-μm radius). Segmentation was achieved by manual threshold definition to match the intensity of visualized fluorescent signal. Nuclear and cytoplasmic podocyte volumes were obtained separately and then summed to obtain total podocyte volume.

To define IGVs, podocyte cytoplasmic surfaces were expanded 4 μm by morphologic dilation, which dilates a selected surface by a defined distance in micrometers, using the Dilate Surface Xtension feature of Imaris (http://open.bitplane.com/tabid/235/Default.aspx?id=95) to encompass all peripheral podocyte nuclei in the urinary space. Total podocyte number per glomerulus was divided by glomerular volume to obtain podocyte density. The percentage (volume density) of total podocyte volume per IGV was also calculated.

2D Analyses of Podocyte Depletion

In total, 15–25 glomerular cross-sections were selected from all sampled glomeruli per mouse; these included the same glomeruli used for the 3D analysis. The 2-μm-thick optical sections were isolated from the middle of each glomerulus to homogenize as best as possible glomerular sampling. p57+ cell nuclei were counted using the cell counter built–in feature of Fiji imaging software to define podocyte number per glomerular cross-section per mouse. Glomerular area was estimated using a polygon region of interest around the glomerular tuft. Podocyte cytoplasmic area was obtained (SNP+ signal) after automated background subtraction (rolling ball radius: 40 pixels). Average podocyte area was calculated by dividing total podocyte area by the number of podocytes per glomerular cross-section.

ACR

Random spot urine samples were collected from mice in three stages: baseline (0–3 days), week 1 (days 5–9), and weeks 3–5 (≥15 days), and they were stored at −80°C. ACR was obtained by dividing urinary albumin concentration (Albuwell murine microalbuminuria ELISA; Exocell) by urinary creatinine concentration (Creatinine Companion; Exocell).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) and Stata 13 (StataCorp., College Station, TX). All datasets were subjected to an ROUT test for outlier detection and removal with a Q (false discovery rate) of 1%. A normality test was run on all datasets. If normality was achieved, a two–tailed unpaired t test was used to identify significant differences between two groups. For skewed distributions, Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare two groups. Data are represented as means±SDs unless otherwise stated. Measures of association were tested by Spearman rank coefficients. Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the facilities and the scientific and technical assistance of members of Monash Micro Imaging, including Dr. Alex Fulcher and Dr. Judy Callaghan, and members of the Monash Histology Platform.

This research was funded by National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia grant 606619.

Parts of this work were presented in poster format during the American Society of Nephrology Kidney Week on November 3–8, 2015 in San Diego, California.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2015121340/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Reiser J, Sever S: Podocyte biology and pathogenesis of kidney disease. Annu Rev Med 64: 357–366, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greka A, Mundel P: Cell biology and pathology of podocytes. Annu Rev Physiol 74: 299–323, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fukuda A, Chowdhury MA, Venkatareddy MP, Wang SQ, Nishizono R, Suzuki T, Wickman LT, Wiggins JE, Muchayi T, Fingar D, Shedden KA, Inoki K, Wiggins RC: Growth-dependent podocyte failure causes glomerulosclerosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1351–1363, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wharram BL, Goyal M, Wiggins JE, Sanden SK, Hussain S, Filipiak WE, Saunders TL, Dysko RC, Kohno K, Holzman LB, Wiggins RC: Podocyte depletion causes glomerulosclerosis: Diphtheria toxin-induced podocyte depletion in rats expressing human diphtheria toxin receptor transgene. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 2941–2952, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiggins RC: The spectrum of podocytopathies: A unifying view of glomerular diseases. Kidney Int 71: 1205–1214, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kriz W: Podocyte is the major culprit accounting for the progression of chronic renal disease. Microsc Res Tech 57: 189–195, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Puelles VG, Bertram JF: Counting glomeruli and podocytes: Rationale and methodologies. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 24: 224–230, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White KE, Bilous RW: Estimation of podocyte number: A comparison of methods. Kidney Int 66: 663–667, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basgen JM, Nicholas SB, Mauer M, Rozen S, Nyengaard JR: Comparison of methods for counting cells in the mouse glomerulus. Nephron, Exp Nephrol 103: e139–e148, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lemley KV, Bertram JF, Nicholas SB, White K: Estimation of glomerular podocyte number: A selection of valid methods. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 1193–1202, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White KE: Research into the structure of the kidney glomerulus---making it count. Micron 43: 1001–1009, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Puelles VG, Douglas-Denton RN, Cullen-McEwen LA, Li J, Hughson MD, Hoy WE, Kerr PG, Bertram JF: Podocyte number in children and adults: Associations with glomerular size and numbers of other glomerular resident cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 2277–2288, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Puelles VG, Cullen-McEwen LA, Taylor GE, Li J, Hughson MD, Kerr PG, Hoy WE, Bertram JF : Human podocyte depletion in association with older age and hypertension [Published online ahead of print January 20, 2016]. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol doi:10.1152/00497.2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Schwartzman M, Reginensi A, Wong JS, Basgen JM, Meliambro K, Nicholas SB, D’Agati V, McNeill H, Campbell KN: Podocyte-specific deletion of Yes-associated protein causes FSGS and progressive renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 216–226, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weins A, Wong JS, Basgen JM, Gupta R, Daehn I, Casagrande L, Lessman D, Schwartzman M, Meliambro K, Patrakka J, Shaw A, Tryggvason K, He JC, Nicholas SB, Mundel P, Campbell KN: Dendrin ablation prolongs life span by delaying kidney failure. Am J Pathol 185: 2143–2157, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo JK, Marlier A, Shi H, Shan A, Ardito TA, Du ZP, Kashgarian M, Krause DS, Biemesderfer D, Cantley LG: Increased tubular proliferation as an adaptive response to glomerular albuminuria. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 429–437, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wanner N, Hartleben B, Herbach N, Goedel M, Stickel N, Zeiser R, Walz G, Moeller MJ, Grahammer F, Huber TB: Unraveling the role of podocyte turnover in glomerular aging and injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 707–716, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dodt HU, Leischner U, Schierloh A, Jährling N, Mauch CP, Deininger K, Deussing JM, Eder M, Zieglgänsberger W, Becker K: Ultramicroscopy: Three-dimensional visualization of neuronal networks in the whole mouse brain. Nat Methods 4: 331–336, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hama H, Kurokawa H, Kawano H, Ando R, Shimogori T, Noda H, Fukami K, Sakaue-Sawano A, Miyawaki A: Scale: A chemical approach for fluorescence imaging and reconstruction of transparent mouse brain. Nat Neurosci 14: 1481–1488, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ertürk A, Becker K, Jährling N, Mauch CP, Hojer CD, Egen JG, Hellal F, Bradke F, Sheng M, Dodt HU: Three-dimensional imaging of solvent-cleared organs using 3DISCO. Nat Protoc 7: 1983–1995, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chung K, Deisseroth K: CLARITY for mapping the nervous system. Nat Methods 10: 508–513, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuwajima T, Sitko AA, Bhansali P, Jurgens C, Guido W, Mason C: ClearT: A detergent- and solvent-free clearing method for neuronal and non-neuronal tissue. Development 140: 1364–1368, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ke MT, Fujimoto S, Imai T: SeeDB: A simple and morphology-preserving optical clearing agent for neuronal circuit reconstruction. Nat Neurosci 16: 1154–1161, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang B, Treweek JB, Kulkarni RP, Deverman BE, Chen CK, Lubeck E, Shah S, Cai L, Gradinaru V: Single-cell phenotyping within transparent intact tissue through whole-body clearing. Cell 158: 945–958, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Susaki EA, Tainaka K, Perrin D, Yukinaga H, Kuno A, Ueda HR: Advanced CUBIC protocols for whole-brain and whole-body clearing and imaging. Nat Protoc 10: 1709–1727, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Treweek JB, Chan KY, Flytzanis NC, Yang B, Deverman BE, Greenbaum A, Lignell A, Xiao C, Cai L, Ladinsky MS, Bjorkman PJ, Fowlkes CC, Gradinaru V: Whole-body tissue stabilization and selective extractions via tissue-hydrogel hybrids for high-resolution intact circuit mapping and phenotyping. Nat Protoc 10: 1860–1896, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Short KM, Smyth IM: Analysis of native kidney structures in three dimensions. Methods Mol Biol 886: 95–107, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Short KM, Combes AN, Lefevre J, Ju AL, Georgas KM, Lamberton T, Cairncross O, Rumballe BA, McMahon AP, Hamilton NA, Smyth IM, Little MH: Global quantification of tissue dynamics in the developing mouse kidney. Dev Cell 29: 188–202, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Combes AN, Short KM, Lefevre J, Hamilton NA, Little MH, Smyth IM: An integrated pipeline for the multidimensional analysis of branching morphogenesis. Nat Protoc 9: 2859–2879, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richardson DS, Lichtman JW: Clarifying tissue clearing. Cell 162: 246–257, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nicholas SB, Basgen JM, Sinha S: Using stereologic techniques for podocyte counting in the mouse: Shifting the paradigm. Am J Nephrol 33[Suppl 1]: 1–7, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pippin JW, Kaverina NV, Eng DG, Krofft RD, Glenn ST, Duffield JS, Gross KW, Shankland SJ: Cells of renin lineage are adult pluripotent progenitors in experimental glomerular disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 309: F341–F358, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pippin JW, Glenn ST, Krofft RD, Rusiniak ME, Alpers CE, Hudkins K, Duffield JS, Gross KW, Shankland SJ: Cells of renin lineage take on a podocyte phenotype in aging nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 306: F1198–F1209, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pippin JW, Sparks MA, Glenn ST, Buitrago S, Coffman TM, Duffield JS, Gross KW, Shankland SJ: Cells of renin lineage are progenitors of podocytes and parietal epithelial cells in experimental glomerular disease. Am J Pathol 183: 542–557, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sagrinati C, Netti GS, Mazzinghi B, Lazzeri E, Liotta F, Frosali F, Ronconi E, Meini C, Gacci M, Squecco R, Carini M, Gesualdo L, Francini F, Maggi E, Annunziato F, Lasagni L, Serio M, Romagnani S, Romagnani P: Isolation and characterization of multipotent progenitor cells from the Bowman’s capsule of adult human kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2443–2456, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ronconi E, Sagrinati C, Angelotti ML, Lazzeri E, Mazzinghi B, Ballerini L, Parente E, Becherucci F, Gacci M, Carini M, Maggi E, Serio M, Vannelli GB, Lasagni L, Romagnani S, Romagnani P: Regeneration of glomerular podocytes by human renal progenitors. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 322–332, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lasagni L, Angelotti ML, Ronconi E, Lombardi D, Nardi S, Peired A, Becherucci F, Mazzinghi B, Sisti A, Romoli S, Burger A, Schaefer B, Buccoliero A, Lazzeri E, Romagnani P: Podocyte regeneration driven by renal progenitors determines glomerular disease remission and can be pharmacologically enhanced. Stem Cell Rep 5: 248–263, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peired A, Angelotti ML, Ronconi E, la Marca G, Mazzinghi B, Sisti A, Lombardi D, Giocaliere E, Della Bona M, Villanelli F, Parente E, Ballerini L, Sagrinati C, Wanner N, Huber TB, Liapis H, Lazzeri E, Lasagni L, Romagnani P: Proteinuria impairs podocyte regeneration by sequestering retinoic acid. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 1756–1768, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eng DG, Sunseri MW, Kaverina NV, Roeder SS, Pippin JW, Shankland SJ: Glomerular parietal epithelial cells contribute to adult podocyte regeneration in experimental focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int 88: 999–1012, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berger K, Moeller MJ: Podocytopenia, parietal epithelial cells and glomerulosclerosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 29: 948–950, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Remuzzi A, Pergolizzi R, Mauer MS, Bertani T: Three-dimensional morphometric analysis of segmental glomerulosclerosis in the rat. Kidney Int 38: 851–856, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hodgin JB, Bitzer M, Wickman L, Afshinnia F, Wang SQ, O’Connor C, Yang Y, Meadowbrooke C, Chowdhury M, Kikuchi M, Wiggins JE, Wiggins RC: Glomerular aging and focal global glomerulosclerosis: A podometric perspective. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 3162–3178, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.White KE, Bilous RW Diabiopsies Study Group : Structural alterations to the podocyte are related to proteinuria in type 2 diabetic patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 19: 1437–1440, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.White KE, Bilous RW, Marshall SM, El Nahas M, Remuzzi G, Piras G, De Cosmo S, Viberti G: Podocyte number in normotensive type 1 diabetic patients with albuminuria. Diabetes 51: 3083–3089, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steffes MW, Schmidt D, McCrery R, Basgen JM International Diabetic Nephropathy Study Group : Glomerular cell number in normal subjects and in type 1 diabetic patients. Kidney Int 59: 2104–2113, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moeller MJ, Sanden SK, Soofi A, Wiggins RC, Holzman LB: Podocyte-specific expression of cre recombinase in transgenic mice. Genesis 35: 39–42, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Puelles VG, Douglas-Denton RN, Cullen-McEwen L, McNamara BJ, Salih F, Li J, Hughson MD, Hoy WE, Nyengaard JR, Bertram JF: Design-based stereological methods for estimating numbers of glomerular podocytes. Ann Anat 196: 48–56, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.