Abstract

The aim of the present study was to investigate the possible damage-repair mechanisms of neural stem cells (NSCs) following hypoxic-ischemic brain damage (HIBD). NSCs obtained from Sprague Dawley rats were treated with tissue homogenate from normal or HIBD tissue, and β-catenin expression was silenced using siRNA. The differentiation of NSCs was observed by immunofluorescence, and semiquantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction and western blot analysis were applied to detect the mRNA and protein expression levels of Ngn1 and BMP4 in the NSCs. Compared with control NSCs, culture with brain tissue homogenate significantly increased the differentiation of NSCs into neurons and oligodendrocytes (P<0.05), whereas differentiation into astrocytes was significantly reduced (P<0.05). Compared with negative control-transfected cells, knockdown of β-catenin expression significantly decreased the differentiation of NSCs into neurons and oligodendrocytes (P<0.01), whereas the percentage of NSCs differentiated into astrocytes was significantly increased (P<0.01). Compared with control NSCs, the mRNA and protein expression levels of Ngn1 were significantly increased (P<0.01) and BMP4 levels were significantly reduced (P<0.01) by exposure of the cells to brain tissue homogenate. Compared with the negative control plasmid-transfected NSCs, the levels of Ngn1 mRNA and protein were significantly reduced by β-catenin siRNA (P<0.01), whereas BMP4 levels were significantly increased (P<0.01). In summary, the damaged brain tissues in HIBD may promote NSCs to differentiate into neurons for self-repair processes. β-Catenin, BMP4 and Ngn1 may be important for the coordination of NSC proliferation and differentiation following HIBD.

Keywords: β-catenin, RNA interference, hypoxic-ischemic brain damage, electroporation transfection

Introduction

Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) is a common cause of brain damage in neonates, and is the leading cause of severe neurological sequelae in children (1). Of the ~130 million births worldwide each year, four million infants will suffer from birth asphyxia, and of these, one million will result in mortality and a similar number will develop serious and long-term sequelae, including neurodevelopmental disorders (2). In China, the incidence rate of neonatal asphyxia is 1.14–11.7%, and the incidence of HIE in full-term live birth infants is 1–2/1000 affected newborns. Approximately 15–20% of affected newborns will succumb to the condition within the neonatal period, and an additional 25–30% will develop severe and permanent neurological handicaps (3), including cerebral palsy, seizures, visual defects, mental retardation, cognitive impairment and epilepsy (4). There is currently no specific treatment for HIE. Previous studies have demonstrated that endogenous neural stem cells (NSCs) exist in certain areas of the brain, and that brain damage may stimulate the proliferation, differentiation and self-repair mechanisms of these NSCs (5–7). However, endogenous stem cells are limited in number, and their survival may be affected by neurite growth inhibitory factors and deficiencies of neurotrophic factors. Thus, the potential for spontaneous brain repair is limited. When brain damage occurs, the mechanisms of NSC proliferation and differentiation may provide a method to enhance the autogenous repair functions of the brain, thus, providing novel insight and treatment strategies for hypoxic-ischemic brain damage (HIBD). β-Catenin is a crucial molecule in the Wnt signaling pathway. During ischemic brain injuries, β-catenin is important for the regulation of NSC proliferation and differentiation (8–10). Neurogenin 1 (Ngn1) is a downstream target gene of β-catenin, and previous studies have demonstrated that Ngn1 is important during the differentiation of NSCs into neurons (11,12). As a member of the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) family, the synergy between BMP4 and β-catenin is important in determining the differentiation pathway of NSCs (13,14). The regulatory role of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling system during HIBD remains unclear. Therefore, referring to the literature (15), the present study cultured NSCs in brain tissue homogenate from normal and HIBD brains to simulate the respective microenvironments. Additionally, NSCs were transfected with β-catenin small interfering RNA (siRNA) to investigate the effects of β-catenin on NSC differentiation, and the gene expression levels of Ngn1 and BMP4. The current study aimed to investigate the potential mechanisms of NSC differentiation in HIBD rats at the in vitro cell level.

Materials and methods

Isolation, sampling and culture of NSCs from cerebral cortex of neonatal Sprague Dawley (SD) rats

A mix of male and female SD rats (n=50; age, 1–3 days; weight, 10.5±1.1 g) were provided by The Experimental Animal Center of The First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University (Ürümqi, China). They were sacrificed by abdominal injection of 100 g/l chloral hydrate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), then disinfected by soaking in 750 ml/l ethanol for 5 min. The cerebral cortex tissues were isolated and digested in trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C for 15 min. Digested tissue was filtered through a 200-mesh filter (Fuzhou Maixin Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd., Fuzhou, China), then centrifuged at 157 × g for 5 min, the supernatant was discarded and cells were resuspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/F12 (Hyclone; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, UT, USA), containing 20 ml/l B27, 10 mg/l basic fibroblast growth factor and 20 mg/l epidermal growth factor, all purchased from Gibco (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Cells were seeded into culture flasks and cultured at 37°C and in an atmosphere of 50 ml/l CO2. Half the medium was changed every 3–4 days, and the cells were passaged once every 7 days. The present study was approved by the ethics committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University.

Cell transfection

Cells were harvested and centrifuged at 4°C, 640 × g for 5 min, then resuspended in DMEM/F12 at room temperature at a density of 2.5×109–2.5×1010 cells/l. Electroporation apparatus (Multiporator 4308 electroporation system) was purchased from Eppendorf (Hamburg, Germany). The cell suspension was transferred into electrotransformation cuvettes, and 20 plasmid (pGCPU6/GFP/Neo siRNA expression vector; Shanghai Ji Kai Gene Chemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was added, while an equal volume of electrotransformation solution was added to the blank control group. Electroporation was performed at 300 V for 60 μsec. The cells were transferred into culture flasks 5–10 min later and cultured at 37°C and in a 5 ml/l CO2 atmosphere.

Preparation of HIBD model and brain tissue homogenate

Healthy male and female, SD rats (n=50; age, 7 days; weight, 13.2±1.4 g) obtained from the Experimental Animal Center of The First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University were randomly divided into control and HIBD groups. The control group (n=50) received no treatment. In the HIBD group (n=100), the Rice-Vannucci method (16) was used to perform the HIBD model. The rats were anesthetized by ether inhalation (1.5 ml; Sigma-Aldrich) and the skin was disinfected with 750 ml/l alcohol. Incision to the neck separated the left common carotid artery and was ligatured with 7.0 sterilized silk wire (Shanghai Nation Medical Equipment Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), the vessel was cut at the middle of ligation. Following 2 h rest, the rat was placed into a plexiglass hypoxic chamber (30×40×50 cm) at normal atmospheric pressure. Nitrogen-oxygen mixture entered the chamber through a 1×1-cm hole on one side. A hole at the other side was connected to a CY-12C portable digital oxygen analyzer (Meicheng Electrochemical Analytical Instruments, Hangzhou, China). The bottom of the chamber was covered with soda lime to absorb CO2 and moisture. The oxygen concentration inside the cabin was controlled at ~8 ml/l, the temperature at 36±1°C, and humidity was 70±5 ml/l. The rats were under hypoxic conditions for a 2 h period. After 24 h, the HIBD rats and the control SD rats were sacrificed with 100 g/l chloral hydrate by abdominal injection, and the whole left brain tissues were removed and suspended in DMEM/F12 (9X volume of brain tissue). The tissues were homogenized on ice and centrifuged at 3,913 × g at 4°C for 15 min. The supernatant was collected, divided into 1.5 ml centrifuge tubes and stored at −80°C.

Co-culture of brain tissue supernatant and NSCs

NSCs were collected 24 h after transfection and centrifuged at 157 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was discarded and the precipitate was resuspended in DMEM/F12. The clusters of cells were pipetted into single cells by syringe needle, then seeded into 6-well plates. The brain tissue homogenate supernatants of normal and HIBD rats were added to the cells, according to the different experimental groupings, at an equal ratio of homogenate to medium.

Experimental grouping

The second and third generation NSCs were randomly divided into 5 groups as follows: i) Blank control group without plasmid transfection (CON group); ii) NSCs transfected with negative control (NC) plasmid for 24 h, co-cultured with normal brain tissue homogenate (NC+N group); iii) NSCs transfected with NC plasmid for 24 h, co-cultured with HIBD brain tissue homogenate (NC+HIBD group); iv) NSCs transfected with β-catenin siRNA (Shanghai Ji Kai Gene Chemical Technology Co., Ltd.) for 24 h, co-cultured with normal brain tissue homogenate (siNSCs+N group); and v) NSCs transfected with β-catenin siRNA for 24 h, co-cultured with HIBD brain tissue homogenate (siNSCs+HIBD group).

Detection of NSC differentiation by immunofluorescence

The immunofluorescence staining was performed 48 h after transfection according to the methods of a previous study (17). NSCs were fixed in ReadiUse™ 4% formaldehyde fixation solution (AAT Bioquest, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) for 15–20 min at room temperature, and then permeabilized with 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Hyclone; GE Healthcare Life Sciences) for 30 min, and incubated in blocking buffer which contained 10% goat serum (Biorbyt, Cambridge, UK) for 10 min. The cells were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C and secondary antibodies for 30 min at room temperature. The primary antibodies used were as follows: Mouse forkhead box O4 (O4) antibody (1:50; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA; cat. no. ab128908), rabbit enolase 2 (NSE) antibody (1:50; Abcam; cat. no. ab53025), and rabbit glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) antibody (1:50; Abcam; cat. no. ab7260). The secondary antibodies were fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:100; Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd., Wuhan, China; cat. no. SA1064) and CY3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:100; Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd.; cat. no. SA1074). Following removal of the secondary antibodies, 50 μ1 Hoechst 33258 (10 μg/ml; Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd.) was added and incubated in darkness at room temperature for 20 min. Coverslips were mounted with 50 ml/l buffered glycerol (Fuzhou Maixin Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd.), and cells were imaged under a BX61 fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation). The experiment was performed 6 times and 6 non-overlapping fields of vision were captured. The differentiation percentages of NSCs to neurons or glial cells were then calculated according to the following formulae: (NSE positively stained cells/Hoechst 33258-stained cells) × 100; (GFAP positively stained cells/Hoechst 33258-stained cells) × 100; and (O4 positively stained cells/Hoechst 33258-stained cells) × 100.

Nestin immunofluorescence assay

The neurospheres cloned from single cells were inoculated into each well of 24-well plates with pre-polylysine-coated coverslips, and 1 ml serum-free medium was then added to each well. The 24-well plates were then cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 2 h to allow cell adhesion prior to the Nestin immunofluorescence assay. The culture medium was removed and 1 ml of 0.01 mol/l PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.2) was added for 15 min at room temperature to fix cells. The cells were washed three times with 0.01 mol/l PBS (pH 7.2), and then 200 μ1 of 0.01 mol/l PBS containing 10% goat serum (pH 7.2) was added into each well, and the plates were gently shaken at room temperature for 30 min. Following removal of the blocking solution, 200 μ1 rabbit anti-Nestin polyclonal antibody (dilution, 1:150; Abcam; cat. no. ab92391) was added to each well, and incubated with gentle shaking at room temperature for 1 h, followed by overnight incubation at 4°C. Following washing three times with PBS, FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (dilution, 1:100) was added to each well, and gently shaken for 2 h in darkness at room temperature. Following further washing three times with PBS, glycerol phosphate buffer was used to mount the slices. The neurospheres with positive Nestin immunofluorescence were then observed using a fluorescence microscope with the excitation wavelength of 495 nm and an absorption wavelength of 520 nm.

mRNA expression of Ngnl and BMP4 in NSCs assessed by semiquantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

NSCs from the 5 experimental groups were collected 48 h after transfection and total RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription was performed to obtain cDNA for the PCR reaction using PrimeScript™ RT kits (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Dalian, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions at 37°C for 15 min, followed by 85°C for 5 sec. The reaction system (20 μ1 for each sample) was as follows: 4 μ1 5X PrimeScript Buffer; 1 μ1 PrimeScript RT Enzyme mix I; 1 μ1 50 μmol/l Oligo dT Primer; 1 μ1 100 μmol/l random hexamers; and 13 total RNA. The PCR system (15 μ1 for each sample) was as follows: 7.5 μ1 2X Premix Ex Taq; 0.25 μ1 forward primer (10 μmol/l); 0.25 μ1 reverse primer (10 μmol/L); 3 μ1 cDNA (5 ng/μL); and 4 μ1 distilled water. GAPDH was used as the reference gene. The following primers were used to amplify the indicated fragments: Ngn 1, F 5′-CGGCCAGCGATACAGAGTC-3′ and R 3′-TACGGGATGAAGCAGGGTG-5′, amplified fragment size 190 bp; BMP4, F 5′-AGAGCCAACACTGTGAGGA-3′ and R 3′-TGTCCAGGCACCATTTCT-5′, amplified fragment size 245 bp; and GAPDH, F 5′-ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC-3′ and R 5′-TCCACC ACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3′, amplified fragment size 450 bp. The reaction cycling parameters were as follows on a CFX96 Touch™ real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA): Initial step 95°C for 5 min; 35 cycles 94°C for 30 sec, 8°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 30 sec, and final step 72°C for 5 min. The PCR products were then electrophoretically separated on a 5% agarose gel. The optical density ratios of Ngn1 and BMP4 were normalized to GAPDH in each group to reflect the relative optical density. Ethidium bromide (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to visualize the DNA ladder.

Detection of Ngnl and BMP4 protein expression levels in NSCs by western blot

Total protein was extracted from NSCs of the 5 groups 48 h after transfection using radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA). Protein concentration was determined using the Coomassie brilliant blue method and protein concentration of the samples was adjusted to 50 μg/μl. The protein samples were loaded onto 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels for electrophoresis. The voltage used through the concentration gel was 60 V, and 100 V for the separating gel. Following electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. After washing three times for 15 min in PBS, the nitrocellulose membrane was then immersed into blocking solution of 1% bovine serum albumin (Fuzhou Maixin Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd.) at room temperature for 2 h. Following blocking, the membranes were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C, followed by washing with PBS. The horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody was added, followed by incubation at room temperature for 2 h. Visualization was conducted using the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL Plus Western Blotting Detection reagent; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Little Chalfont, UK). The intensity of bands was calculated with ImageJ 1.46 analysis software (imagej.nih.gov/ij/). The primary antibodies used were as follows: Polyclonal mouse Ngn1 (1:500; Abcam; cat. no. ab66498); monoclonal mouse BMP4 (1:500; Abcam; cat. no. ab39973) and monoclonal mouse β-actin (1:100; Abcam; cat. no. ab6276). The secondary antibody was horseradish peroxidase-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG (1:5,000; Abcam; cat. no. ab6808).

Statistical analysis

The experiments were repeated 5 times. The experimental data are expressed as χ±s. SPSS statistical analysis software version 16.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for analysis of variance tests to compare the intergroup difference. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Culture and identification of NSCs

NSCs were observed using an inverted phase contrast microscope (CKX41; Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The cultured cells appeared scattered with round-like shape, and small cell bodies, with good refraction. Following 3 days in culture, the cells grew gradually and formed cell balls composed of several cells. Following passage, single cells remained present in the medium, there were also small cell clumps, and some single cells undergoing cell division. Gradually, larger balls composed of more cells were formed. As observed by immunofluorescence staining, the primary and subcultured single cell balls were Nestin-positive. Fetal calf serum (10%) was added to the culture medium for 2 days, subsequently, the NSC balls quickly adhered to the walls of the culture flasks and differentiated. Several processes were observed to protrude from the edge of cell balls. After 7 days, the cell balls disappeared, and the cells exhibited larger nuclei. The refraction was improved and the axons partially intertwined with each other forming a network.

Differentiation of NSCs

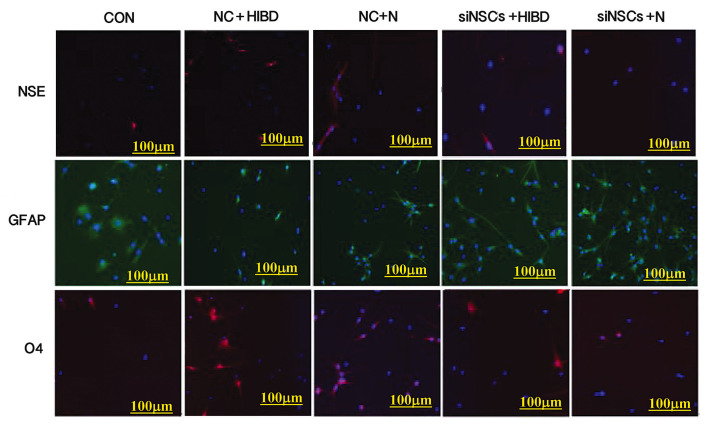

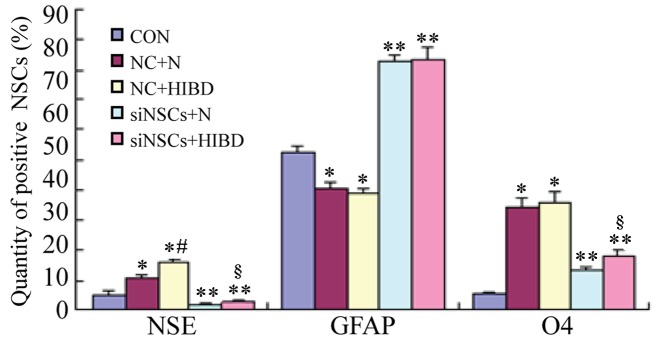

Simultaneous staining for NSE (neuronal marker), GFAP (astrocyte marker) and O4 (oligodendrocyte precursor marker) was performed (Fig. 1), and the percentages of NSCs that differentiated into NSE-positive cells, GFAP-positive cells and O4-positive cells were counted using the fluorescence microscope (Table I, Fig. 2). Compared with the CON group, the differentiation into neurons and oligodendrocytes was increased in the NC+N and the NC+HIBD groups (neuron differentiation, P=0.001 and P=0.001, respectively; oligodendrocyte differentiation, P=0.001 and P=0.002, respectively), while the differentiation into astrocytes was reduced (each P= 0.001). Compared with the NC+N group, the NC+HIBD group exhibited increased differentiation into neurons (P=0.001), however, there was no statistically significant difference in the number of astrocytes or oligodendrocytes between the 2 groups. Compared with the CON group, the 2 siNSC groups transfected with β-catenin siRNA exhibited reduced differentiation into neurons (siNSC+N vs. CON, P=0.001; siNSC+HIBD vs. CON, P=0.009) and increased differentiation into astrocytes (siNSC+N vs. CON, P=0.001; siNSC+HIBD vs. CON, P=0.001). Additionally, these siNSC groups exhibited increased differentiation into oligodendrocytes compared with the CON group (P=0.001), however, this was reduced compared with the NC group. Compared with the siNSCs+N group, the siNSCs+HIBD group exhibited increased differentiation into neurons and oligodendrocytes (neuron, P=0.006; oligodendrocyte, P=0.001), however, these 2 groups showed no significant difference in the levels of differentiation into astrocytes (Figs. 1 and 2, Table I).

Figure 1.

Expressions of NSE, O4 and GFAP in the experimental groups indicating NSC differentiation by fluorescence microscopy (×100). Immunofluorescence staining performed simultaneously on each group, red (CY3) represents the expression NSE or O4 in cytoplasm, green (FITC) represents the expression of GFAP in cytoplasm, blue (Hoechst 33258) represents the nucleus. NSC, neural stem cell; NSE, enolase 2; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; O4, oligodendrocyte cell surface antigen O4; CON, blank control group; NC, negative control plasmid-transfected cells; N, normal brain tissue; HIBD, hypoxic-ischemic brain damage tissue; siNSC, β-catenin small interfering RNA-transfected cells.

Table I.

Comparison of the positive ratios of NSC-expressed neural markers between the different groups.

| Group | NSE | GFAP | O4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| CON | 5.26±1.71 | 52.25±2.27 | 5.70±0.70 |

| NC+N | 10.81±0.90a | 40.48±1.97a | 34.42±2.77a |

| NC+HIBD | 15.88±1.05a,c | 38.83±1.63a | 35.62±3.91a |

| siNSCs+N | 1.48±0.53b | 82.77±2.43b | 13.25±1.08b |

| siNSCs+HIBD | 2.83±0.79b,d | 83.20±4.48b | 18.30±1.89b,d |

Data presented as χ±s (% positively-stained cells).

P<0.05 and

P<0.01 vs. CON group;

P<0.05 vs. NC+N group;

P<0.05 vs. siNSCs+N group. NSC, neural stem cell; NSE, enolase 2; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; O4, oligodendrocyte cell surface antigen O4; CON, blank control group; NC, negative control plasmid-transfected cells; N, normal brain tissue; HIBD, hypoxic-ischemic brain damage tissue; siNSC, β-catenin small interfering RNA-transfected cell.

Figure 2.

Positive ratios of NSCs-expressed neural markers in the different groups. The immunofluorescence staining was performed on the 5 groups simultaneously. The number of positive cells was measured (%), and expressed as χ±s. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. CON group; #P<0.05 vs. NC+N group; §P<0.05 vs. siNSCs+N group. NSC, neural stem cell; NSE, enolase 2; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; O4, oligodendrocyte cell surface antigen O4; CON, blank control group; NC, negative control plasmid-transfected cells; N, normal brain tissue; HIBD, hypoxic-ischemic brain damage tissue; siNSC, β-catenin small interfering RNA-transfected cell.

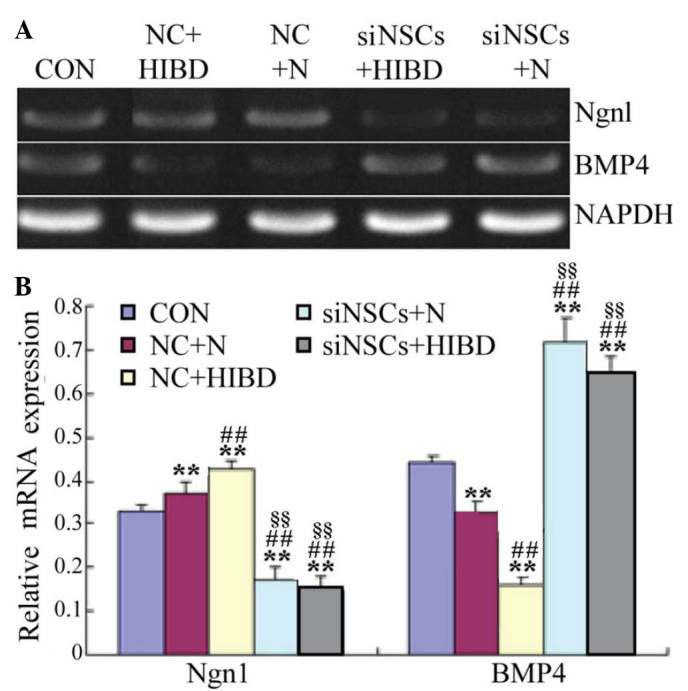

β-Catenin siRNA reduces Ngnl and increases BMP4 mRNA expression levels in NSCs

Semiquantitative RT-PCR results demonstrated that, compared with the CON group, the expression levels of Ngn1 mRNA were significantly increased in the NC+HIBD group (P=0.005; Fig. 3), however, the BMP4 mRNA expression levels were significantly reduced (P=0.001). Compared with the NC+N group, the expression levels of Ngn1 mRNA were significantly reduced in the NC+HIBD group (P=0.004), however, BMP4 mRNA levels were significantly increased (P=0.001). Compared with the CON and NC groups, the Ngn1 mRNA levels were significantly decreased in the siNSC groups (siNSC+N vs. CON, P=0.001; siNSC+N vs. NC+N, P=0.001; siNSC+N vs. NC+HIBD, P=0.001; siNSC+HIBD vs. CON, P=0.002; siNSC+HIBD vs. NC+N, P=0.001; siNSC+HIBD vs. NC+HIBD, P=0.001), whereas, the BMP4 mRNA levels were significantly increased (siNSC+N vs. CON, P=0.001; siNSC+N vs. NC+N, P=0.001; siNSC+NC+HIBD, P=0.001; siNSC+HIBD vs. CON, P=0.003; siNSC+HIBD vs. NC+N, P=0.002; siNSC+HIBD vs. NC+HIBD, P=0.001). No significant difference was observed in the mRNA levels of Ngn1 and BMP4 mRNA between the siNSCs+N and the siNSCs+HIBD groups (Fig. 3, Table II).

Figure 3.

Expression levels of Ngn1 and BMP4 mRNA in NSCs following transfection with recombinant plasmid for 48 h. (A) Detection of Ngn1 and BMP4 mRNA levels by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. GAPDH was used as the internal control. (B) Semi-quantification of Ngn1/GAPDH and BMP4/GAPDH mRNA optical density ratios was conducted for each group. **P<0.01 vs. CON group; ##P<0.01 vs. NC+N group; §§P<0.01 vs. NC+HIBD group. Ngn1, neurogenin 1; BMP4, bone morphogenetic protein 4; NSC, neural stem cell; CON, blank control group; NC, negative control plasmid-transfected cells; N, normal brain tissue; HIBD, hypoxic-ischemic brain damage tissue; siNSC, β-catenin small interfering RNA-transfected cell.

Table II.

Comparison of Ngn1 and BMP4 mRNA expression levels the different NSC groups.

| Group | Ngn1 | BMP4 |

|---|---|---|

| CON | 0.33±0.02 | 0.44±0.01 |

| NC+N | 0.37±0.03a | 0.32±0.02a |

| NC+HIBD | 0.44±0.03a,b | 0.17±0.03a,b |

| siNSCs+N | 0.19±0.02a–c | 0.72±0.04a–c |

| siNSCs+HIBD | 0.17±0.03a–c | 0.65±0.06a–c |

Data presented as relative optical density value (χ±s).

P<0.01 vs. CON group;

P<0.01 vs. NC+N group;

P<0.01 vs. NC+HIBD group. Ngn1, neurogenin 1; BMP4, bone morphogenetic protein 4; NSC, neural stem cell; CON, blank control group; NC, negative control plasmid-transfected cells; N, normal brain tissue; HIBD, hypoxic-ischemic brain damage tissue; siNSC, β-catenin small interfering RNA-transfected cell.

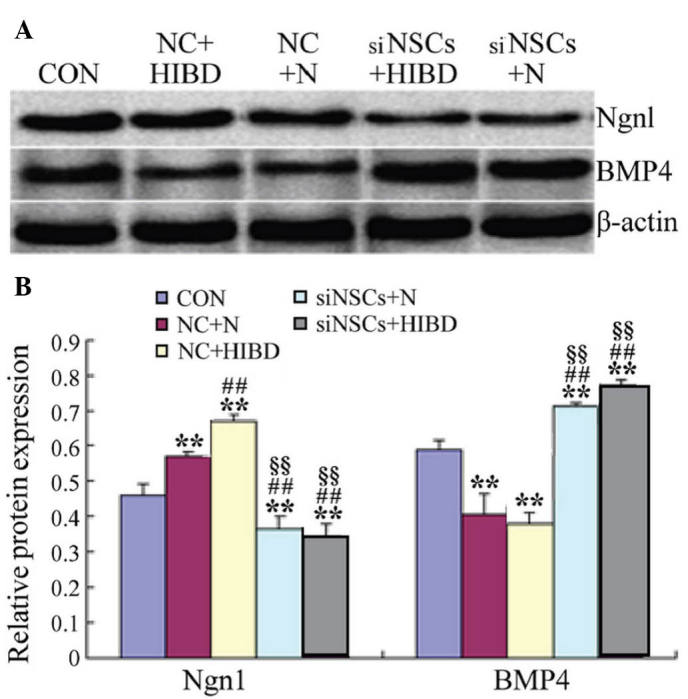

β-Catenin siRNA reduces Ngnl and increases BMP4 protein levels in NSCs

As presented in Fig. 4 and Table III, western blot analysis demonstrated that, compared with the CON group, the levels of Ngn1 protein were significantly increased in the NC groups (NC+N vs. CON, P=0.027; NC+HIBD vs. CON, P=0.001), however, BMP4 protein levels were significantly reduced (NC+N vs. CON, P=0.003; NC+HIBD vs. CON, P=0.008). Compared with the NC+N group, the expression levels of Ngn1 protein were significantly increased in the NC+HIBD group (P=0.002). The protein expression levels of Ngn1 protein were decreased in the siNSC groups compared with the CON and NC groups (siNSC+N vs. CON, P=0.048; siNSC+N vs. NC+N, P=0.001; siNSC+N vs. NC+HIBD, P=0.001; siNSC+HIBD vs. CON, P=0.023; siNSC+HIBD vs. NC+N, P=0.001; siNSC+HIBD vs. NC+HIBD, P=0.001; Fig. 4), whilst the levels of BMP4 protein were significantly increased (siNSC+N vs. CON, P=0.023; siNSC+N vs. NC+N, P=0.001; siNSC+N vs. NC+HIBD, P=0.002; siNSC+HIBD vs. CON, P=0.001; siNSC+HIBD vs. NC+N, P=0.001; siNSC+HIBD vs. NC+HIBD, P=0.001; Fig. 4). No significant difference was observed between the levels of Ngn1 and BMP4 protein in the siNSCs+N and the siNSCs+HIBD groups (Fig. 4, Table III).

Figure 4.

Expression levels of Ngn1 and BMP4 protein in NSCs following transfection with recombinant plasmid for 48 h. (A) Detection of Ngn1 and BMP4 protein levels by western blot analysis. β-actin was the internal standard. (B) Ngn1β-actin and BMP4β-actin protein optical density ratios were analyzed in each group. **P<0.01 vs. CON group; ##P<0.01 vs. NC+N group; §§P<0.01 vs. NC+HIBD group. Ngn1, neurogenin 1; BMP4, bone morpho-genetic protein 4; NSC, neural stem cell; CON, blank control group; NC, negative control plasmid-transfected cells; N, normal brain tissue; HIBD, hypoxic-ischemic brain damage tissue; siNSC, β-catenin small interfering RNA-transfected cell.

Table III.

Comparison of Ngn1 and BMP4 protein expression levels in the different NSC groups.

| Group | Ngn1 | BMP4 |

|---|---|---|

| CON | 0.46±0.03 | 0.59±0.03 |

| NC+N | 0.58±0.02a | 0.43±0.03a |

| NC+HIBD | 0.67±0.02a,b | 0.41±0.06a |

| siNSCs+N | 0.39±0.04a–c | 0.71±0.05a–c |

| siNSCs+HIBD | 0.37±0.03a–c | 0.77±0.01a–c |

Data presented as relative optical density value (χ±s).

P<0.01 vs. CON group;

P<0.01 vs. NC+N group;

P<0.01 vs. NC+HIBD group. NSC, neural stem cell; CON, blank control group; NC, negative control plasmid-transfected cells; N, normal brain tissue; HIBD, hypoxic-ischemic brain damage tissue; siNSC, β-catenin small interfering RNA-transfected cell.

Discussion

Previous experiments by Zhang et al (15) have successfully isolated and cultured NSCs from the cortex tissues of newborn SD rats. They confirmed that the cells were NSCs, and that they exhibited continuous potential for proliferation and differentiation. RNA interference is used to inhibit the expression of specific genes, resulting in targeted gene silencing (18,19). siRNAs are small non-coding RNA molecules of 21 to 25 nucleotides in length. They are widely used to reduce the expression of a gene to investigate its function. The siRNA vector used to target rat β-catenin in the present study has been previously demonstrated to specifically inhibit the expression of β-catenin (15,20).

In order to further explore the repair mechanisms that occur following HIBD, the current study divided NSCs into 5 treatment groups. Immunocytochemical staining revealed that normal and HIBD brain tissue homogenate promoted NSCs to differentiate into neurons and oligodendrocytes, however, differentiation to astrocytes was suppressed. Notably, the promotion and suppression effects in HIBD brain tissue homogenates were greater than those in normal brain tissue homogenates. β-catenin siRNA inhibited the differentiation of NSCs to neurons, whereas, differentiation to astrocytes was promoted. These results suggested that the local microenvironment has an important impact on the differentiation of NSCs, and that when damaged by hypoxia/ischemia, changes to the brain microenvironments may stimulate proliferation and differentiation of NSCs, thus, initiating autogenous healing processes. Additionally, the results of the current study suggest that β-catenin is important in facilitating the differentiation of NSCs to neurons.

The differentiation of NSCs is dependent on the microenvironment and the regulation of various genes (21–23). Previous studies have demonstrated that the development of NSCs is closely associated with the Wnt, BMP and sonic hedgehog signaling systems. They have investigated how the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway regulates the development and differentiation of NDCs (24,25). Following activation, ß-catenin is translocated into the nucleus, where the β-catenin/T-cell factor complex directly regulates the transcription of Ngnl, thus, regulating the differentiation of NSCs (26,27). BMP4 is an important regulator of neural development. During the development of the nervous system, there is 'crosstalk' between the BMP and Wnt signaling pathways (28–30). Therefore, the current study measured the expression levels of Ngn1 and BMP4 in NSCs exposed to HIBD brain tissue homogenate by semiquantitative RT-PCR and western blotting. The results of the present study suggested that the expression levels of Ngn1 protein and mRNA were increased with the increased differentiation of NSCs into neurons, and that the expression levels of BMP4 protein and mRNA were reduced with the reduced differentiation of NSCs into astrocytes. When ß-catenin expression was inhibited by siRNA, the expression of Ngn1 protein and mRNA were reduced, and the differentiation of NSCs into neurons was decreased. Additionally, the expression level of BMP4 protein and mRNA was increased by β-catenin siRNA, and differentiation of NSCs into astrocytes was also increased. The results of the present study further illustrated that β-catenin siRNA inhibited the differentiation of NSCs to neurons and promoted the differentiation into astrocytes. In HIBD, the damaged brain tissues repair themselves, which may be associated with the fact that β-catenin promotes the differentiation of NSCs to neurons, and this mechanism may be mediated by β-catenin-induced upregulation of Ngn1. BMP4 and Ngn1 are important in the differentiation of NSCs in HIBD, and BMP4 may inhibit the expression of Ngn1. The importance of Ngn1 in promoting the differentiation of NSCs suggests that it may be an important contributor for the repair of brain function following HIBD.

In conclusion, the damaged brain tissues in HIBD may promote NSCs to differentiate into neurons for self-repair processes. β-catenin, BMP4 and Ngn1 may be important in the coordination of NSC proliferation and differentiation following HIBD. The present study demonstrated that in HIBD, Ngn1 can promote the differentiation of endogenous neural stem cells to neurons, thus, repairing brain damage, and that this process is via the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. The current study also provides a foundation for future studies using genetically modified neural stem cells for the treatment of HIBD.

Acknowledgments

The current study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81460195).

References

- 1.Nanavati T, Seemaladinne N, Regier M, Yossuck P, Pergami P. Can we predict functional outcome in neonates with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy by the combination of neuroimaging and electroencephalography? Pediatr Neonatol. 2015;56:307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buonocore G, Perrone S, Longini M, Paffetti P, Vezzosi P, Gatti MG, Bracci R. Non protein bound iron as early predictive marker of neonatal brain damage. Brain. 2013;126:1224–1230. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cai Q, Xue XD, Fu JH. Research status and progress of neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Zhong Guo Shi Yong Er Ke Za Zhi. 2009;24:968–971. In Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vanucci RC, Perlman JM. Interventions for perinatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 1997;100:1004–1014. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.6.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun D. Endogenous neurogenic cell response in the mature mammalian brain following traumatic injury. Exp Neurol. 2016;275:405–410. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun D. The potential of endogenous neurogenesis for brain repair and regeneration following traumatic brain injury. Neural Regen Res. 2014;9:688–692. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.131567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edelmann K, Glashauser L, Sprungala S, Hesl B, Fritschle M, Ninkovic J, Godinho L, Chapouton P. Increased radial glia quiescence, decreased reactivation upon injury and unaltered neuroblast behavior underlie decreased neurogenesis in the aging zebrafish telencephalon. J Comp Neurol. 2013;521:3099–3115. doi: 10.1002/cne.23347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oliva CA, Inestrosa NC. A novel function for Wnt signaling modulating neuronal firing activity and the temporal structure of spontaneous oscillation in the entorhinal-hippocampal circuit. Exp Neurol. 2015;269:43–55. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oliva CA, Vargas JY, Inestrosa NC. Wnts in adult brain: From synaptic plasticity to cognitive deficiencies. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013;7:224. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inestrosa NC, Varela-Nallar L. Wnt signaling in the nervous system and in Alzheimer's disease. J Mol Cell Biol. 2014;6:64–74. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjt051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu W, Zhou H, Liu L, Zhao C, Deng Y, Chen L, Wu L, Mandrycky N, McNabb CT, Peng Y, et al. Disruption of neurogenesis and cortical development in transgenic mice misex-pressing Olig2, a gene in the Down syndrome critical region. Neurobiol Dis. 2015;77:106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu F, Xuan A, Chen Y, Zhang J, Xu L, Yan Q, Long D. Combined effect of nerve growth factor and brain derived neurotrophic factor on neuronal differentiation of neural stem cells and the potential molecular mechanisms. Mol Med Rep. 2014;10:173917–173945. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lei ZN, Liu F, Zhang LM, Huang YL, Sun FY. Bcl-2 increases stroke-induced striatal neurogenesis in adult brains by inhibiting BMP-4 function via activation of β-catenin signaling. Neurochem Int. 2012;61:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chuang CY, Lin KI, Hsiao M, Stone L, Chen HF, Huang YH, Lin SP, Ho HN, Kuo HC. Meiotic competent human germ cell-like cells derived from human embryonic stem cells induced by BMP4/WNT3A signaling and OCT4/EpCAM (epithelial cell adhesion molecule) selection. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:14389–14401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.338434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang XY, Yang YJ, Xu PR, Zheng XR, Wang QH, Chen CF, Yao Y. The role of β-catenin signaling pathway on proliferation of rats neural stem cells after hyperbaric oxygen therapy in vitro. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2011;31:101–109. doi: 10.1007/s10571-010-9559-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rice JE, III, Vannucci RC, Brierley JB. The influence of immaturity on hypoxic-ischemic brain damage in the rat. Ann Neurol. 1981;9:131–141. doi: 10.1002/ana.410090206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen CF, Yang YJ, Wang QH, Yao Y, Li M. Effect of hyperbaric oxygen administered at different pressures and diffrernt exposure time on differentiation of neural stem cells in vitro. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 2010;12:368–372. In Chinese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shyam R, Ren Y, Lee J, Braunstein KE, Mao HQ, Wong PC. Intraventricular delivery of siRNA nanoparticles to the central nervous system. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2015;4:e242. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2015.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li TS, Yawata T, Honke K. Efficient siRNA delivery and tumor accumulation mediated by ionically cross-linked folic acid-poly(ethylene glycol)-chitosan oligosaccharide lactate nanoparticles: For the potential targeted ovarian cancer gene therapy. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2014;52:48–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang XY, Yang YJ, Chen CF, Yao Y, Wang QH. Construction and screening of eukaryotic expression plasmids containing shRNA targeting β-catenin gene. J Med Mol Biol. 2010;7:136–142. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gigek CO, Chen ES, Ota VK, Maussion G, Peng H, Vaillancourt K, Diallo AB, Lopez JP, Crapper L, Vasuta C, et al. A molecular model for neurodevelopmental disorders. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:e565. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen ES, Gigek CO, Rosenfeld JA, Diallo AB, Maussion G, Chen GG, Vaillancourt K, Lopez JP, Crapper L, Poujol R, et al. Molecular convergence of neurodevelopmental disorders. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;95:490–508. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rak K, Völker J, Jürgens L, Völker C, Frenz S, Scherzad A, Schendzielorz P, Jablonka S, Mlynski R, Radeloff A, Hagen R. Cochlear nucleus whole mount explants promote the differentiation of neuronal stem cells from the cochlear nucleus in co-culture experiments. Brain Res. 2015;1616:58–70. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schafer ST, Han J, Pena M, von Bohlen Und Halbach O, Peters J, Gage FH. The Wnt adaptor protein ATP6AP2 regulates multiple stages of adult hippocampal neurogenesis. J Neurosci. 2015;35:4983–4998. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4130-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang L, Liu Y, Li S, Long ZY, Wu YM. Wnt signaling pathway participates in valproic acid-induced neuronal differentiation of neural stem cells. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:578–585. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma YX, Wu ZQ, Feng YJ, Xiao ZC, Qin XL, Ma QH. G protein coupled receptor 50 promotes self-renewal and neuronal differentiation of embryonic neural progenitor cells through regulation of notch and wnt/β-catenin signalings. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;458:836–842. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yuan L, Hassan BA. Neurogenins in brain development and disease: An overview. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2014;558:10–13. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2014.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Imayoshi I, Kageyama R. bHLH factors in self-renewal, multipotency, and fate choice of neural progenitor cells. Neuron. 2014;82:9–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Z, Shi Y, Zhao S, Li J, Li C, Mao B. Xenopus Nkx6.3 is a neural plate border specifier required for neural crest development. PLoS One. 2014;9:e115165. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.An SM, Ding Q, Zhang J, Xie J, Li L. Targeting stem cell signaling pathways for drug discovery: Advances in the Notch and Wnt pathways. Sci China Life Sci. 2014;57:575–580. doi: 10.1007/s11427-014-4665-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]