Abstract

The liver fibrosis index (LFI), based on real-time tissue elastography (RTE), is a method currently used to assess liver fibrosis. However, this method may not consistently distinguish between the different stages of fibrosis, which limits its accuracy. The aim of the present study was to develop novel models based on biochemical, RTE and ultrasound data for predicting significant liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. A total of 85 consecutive patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) were prospectively enrolled and underwent a liver biopsy and RTE. The parameters for predicting significant fibrosis and cirrhosis were determined by conducting multivariate analyses. The splenoportal index (SPI; P=0.002) and LFI (P=0.023) were confirmed as independent predictors of significant fibrosis. Using multivariate analyses for identifying parameters that predict cirrhosis, significant differences in γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT; P=0.049), SPI (P=0.002) and LFI (P=0.001) were observed. Based on these observations, the novel model LFI-SPI score (LSPS) was developed to predict the occurrence of significant liver fibrosis, with an area under receiver operating characteristic curves (AUROC) of 0.87. The diagnostic accuracy of the LSPS model was superior to that of the LFI (AUROC=0.76; P=0.0109), aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index (APRI; AUROC=0.64; P=0.0031), fibrosis-4 index (FIB-4; AUROC= 0.67; P= 0.0044) and FibroScan (AUROC=0.68; P=0.0021) models. In addition, the LFI-SPI-GGT score (LSPGS) was developed for the purposes of predicting liver cirrhosis, demonstrating an AUROC value of 0.93. The accuracy of LSPGS was similar to that of FibroScan (AUROC=0.85; P=0.134), but was superior to LFI (AUROC= 0.81; P= 0.0113), APRI (AUROC= 0.67; P<0.0001) and FIB-4 (AUROC=0.719; P=0.0005). In conclusion, the results of the present study suggest that the use of LSPS and LSPGS may complement current methods of diagnosing significant liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with CHB.

Keywords: real-time tissue elastography, liver fibrosis index, chronic hepatitis B, liver fibrosis, cirrhosis

Introduction

Chronic hepatitis B (CHB), with a prevalence of 7.18% in China, is the primary cause of liver-associated morbidity and mortality (1). Maintenance of viral suppression using antiviral treatment can reverse severe liver fibrosis or early cirrhosis, and reduce liver-associated complications in patients with CHB (2). The use of liver biopsy, which is considered to be the conventional reference standard for the staging of fibrosis, has been challenged over the past decade by the development of novel non-invasive methods (3). These novel techniques rely on two distinct but complementary approaches: A 'physical' approach based on the liver stiffness measurement (LSM), and a 'biological' approach based on the serum biomarkers of fibrosis (4).

Previous studies have demonstrated that assessing LSM with FibroScan may serve as a noninvasive alternative to liver biopsy in evaluating liver fibrosis (5–7). However, the limitations of FibroScan include the lack of a two-dimensional image guidance system and difficulties in evaluating patients with ascites or those with a dense layer of fat tissue under the skin (8,9). Real-time tissue elastography (RTE) is a free-hand technique that is used to visualize the elasticity of the target area by capturing echo signals derived secondary to repetitive compressions caused by the heartbeat (10). A quantitative analysis method based on RTE, known as the liver fibrosis index (LFI), has been developed for assessing liver fibrosis, with the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) values ranging between 0.81 and 0.87 for significant fibrosis (11–13). Numerous studies have demonstrated that RTE is an effective tool for diagnosing hepatic fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C (11,14). However, RTE is unable to accurately distinguish between fibrosis stages with cut-off values (11), which has hindered the universal application of RTE as an alternative to liver biopsy in clinical practice, particularly in regions with a high prevalence of CHB (15).

Therefore, the development of complementary approaches is necessary to achieve increased diagnostic accuracy over standard liver biopsy methods. Various biochemical scores and ultrasonographic (US) noninvasive indexes, including aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index (APRI), fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index and spleen size, have been shown to predict the severity of liver fibrosis (16). Furthermore, previous studies have demonstrated that LFI is highly accurate for diagnosing liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with CHB (15,17). In order to improve the current diagnostic methods, particularly in patients with CHB, the present study developed two prediction models that accurately reflected the progression of CHB into fibrosis or cirrhosis using LFI in combination with biochemical and ultrasound parameters.

Materials and methods

Patients

A total of 103 consecutive patients with CHB were prospectively recruited between January 2014 and September 2014 at the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University (Wenzhou, China). Patients were ≥18 years of age, presented with clinical indications for ultrasound-guided percutaneous liver biopsy and did not receive antiviral therapy. The inclusion criteria for the study were as follows: i) Positive CHB diagnosis; ii) achievement of a satisfactory RTE of the liver; and iii) indication for liver biopsy. The following exclusion criteria were applied to patients: i) Positive for infection with hepatitis A, C, D or E virus; ii) substantial alcohol intake (defined as 30 g of alcohol daily for men and 20 g for women) (18); iii) a previous liver transplantation; iv) malignancy or other terminal disease; and v) refusal to undergo a liver biopsy. CHB was diagnosed according to the practice guidelines of the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (19). Patients were determined to be positive for the hepatitis B surface antigen for >6 months and negative for anti-hepatitis C virus antibodies in the serum. Ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University approved the study and informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Clinical and laboratory information

Prior to obtaining liver biopsies and RTEs, the age, gender, liver disease etiology, height, body weight and body mass index (BMI) of patients were recorded. In addition, the following laboratory data were collected: Levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT), total bilirubin, albumin and fasting glucose, as well as the prothrombin time, white blood cell count and platelet count. Blood sample analyses were performed on-site (at The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University).

US evaluation and FibroScan

Laboratory tests, US examination of the upper abdomen and transient elastography (also known as FibroScan) were performed 1 day before liver biopsy. The portal vein diameter, portal vein velocity (PVV), hepatic artery diameter, hepatic artery velocity, hepatic artery resistive index, spleen size, splenic artery diameter, splenic artery velocity, splenic artery resistive index, splenic vein diameter and splenic vein velocity were measured. In addition, the splenic index (SI) was calculated using the following formula: SI (cm2) =a × b, where a is equivalent to the transverse diameter (in cm) and b is equivalent to the vertical diameter (in cm) of the maximal cross-sectional images of the spleen (20). The splenoportal index (SPI) was calculated by dividing the SI by the mean PVV (21). FibroScan was performed according to the instructions and training provided by the manufacturer (Echosens, Paris, France), and the values obtained were expressed in kilopascals (kPa). FibroScan examinations consisted of >10 validated measurements with a success rate of at least 60% and an interquartile range of ≤30% of the median ratio considered to be reliable (22).

RTE procedure

Subsequent to gray-scale US examination, we used ultrasonography (HI-VISION Ascendus; Hitachi Aloka Medical, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and the EUP-L52 linear probe (3–7 MHz; Hitachi Aloka Medical, Ltd.) to perform RTE, as previously described by Wu et al (17). Briefly, RTE was performed on the right lobe of the liver through the intercostal spaces while patients laid in supine position with their right arm elevated over their head to widen the intercostal space. While patients were holding their breath, strain images were induced by cardiac motion. In order to obtain accurate and reliable images, the region of interest (ROI) of the strain image was placed >1 cm below the surface of the liver and was 2.5×2.5 cm in size, which could represent the degree of stiffness of the liver. An average of 3–5 suitable RTE images for each patient were selected for the final analysis using software developed by Hitachi Aloka Medical, Ltd. If the number of suitable RTE images obtained was insufficient, the patient was excluded from the study. A histogram of strain elasticity values of the ROI in arbitrary units from 0 to 255 (256 stepwise grading) according to color mapping from red (0) to blue (255) was calculated.

As previously reported (17), a total of nine image features were used to quantify the variable patterns of the RTE images, as follows: Mean relative strain value (MEAN) in the ROI; standard deviation (SD) of the relative strain value; low-strain area complexity (COMP; calculated using perimeter2/area); low-strain area percentage (%AREA; calculated based on the percentage of blue area in ROI, indicating stiffness of the tissues); angular second moment (ASM); inverse difference moment (IDM); entropy (ENT); kurtosis (KURT); and skewness (SKEW). In RTE images, the %AREA was defined as the number of relative strain pixels that was lower than the threshold value over the total number of pixels in the ROI; COMP was defined according to the mean complexity of each low-strain region (boundary length2/area); SKEW was used as a scale of asymmetry and its statistical value indicated to what degree a symmetric object of the histogram was skewed; KURT was used as a measure of peak sharpness and its statistical value indicated whether the distribution of the data can be concentrated into an average value; COMP, ENT, IDM and ASM indicated the feature values of the textual variations, randomness, homogeneity and uniformity, respectively. In addition, the distribution of deformation data relative to the principal diagonal was described, which was defined as contrast (CONT). Higher resolution resulted in a greater CONT value. The LFI was calculated according to the following formula: LFI = −0.009MEAN − 0.005SD + 0.023%AREA + 0.025COMP + 0.775SKEW −0.281KURT + 2.083ENT + 3.042IDM + 39.979ASM −5.542 (23).

Liver biopsy

Liver biopsies were performed by senior operators (who conduct >300 biopsies each year) using a TRU-CORE II MCXS1616TX co-axial biopsy needle (Argon Medical Devices, Inc., Plano, TX, USA). Liver biopsy specimens measured >15 mm in length, and were fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin. Tissue sections (4 µm in thickness) were stained with hematoxylin-eosin-saffron, Masson's trichrome stain for collagen, Perl's Prussian blue stain for iron, and Gordon and Sweet's reticulin stain. Two experienced hepatopathologists analyzed biopsies independently and were unaware of the RTE, clinical and laboratory results. Liver biopsy specimens <1.5 cm in length and/or with <6 portal tracts were excluded. Liver fibrosis stages and necroinflammatory activity grades were evaluated according to the Ishak fibrosis scoring system (24). The Ishak system scores fibrosis into seven categories (0–6), with Ishak score of ≥3 defined as significant fibrosis and Ishak score of ≥5 defined as cirrhosis (25).

Statistical analysis

The association of the RTE image features with the clinical or morphological parameters was evaluated using Spearman's rank correlation coefficient and scatterplots. Box plots were used to assess the use of RTE for differentiating between each grade of fibrosis. The χ2 test was used to compare categorical variables, while an independent two-sample t-test was used to compare continuous variables. The primary aim of the present study was to stage fibrosis using an RTE-based prediction model consisting of clinically relevant and US variables. Univariate analysis was initially performed to identify candidate variables among various clinical US factors for the generation of a new formula. Variables with a P-value of <0.05 in the univariate analysis were then included in the subsequent multivariate analysis, where multiple logistic regression analyses was used to select variables for inclusion in the final model. Factors with a P-value of <0.05 were finally selected as components of the new formula. The analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 21.0; IBM SPSS, Armonk, NY, USA). A two-tailed P-value of <0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. The diagnostic performance of the novel RTE-based model, FibroScan and two biochemical scores [APRI = (AST/platelet count) × 100; FIB-4 = (age × AST) / (platelet count × ALT1/2)] were assessed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and histology as a reference. APRI and FIB-4 were selected for comparison since they are readily available noninvasive indexes that are commonly used for the evaluation of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis (16). AUROC values were compared using the DeLong method (26) and MedCalc software (version 12.2.1.0; MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium). The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and likelihood ratio (LR) were calculated using the ROC curves.

Results

Clinical and histological characteristics of the study population

A total of 103 patients with CHB fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Among these, 6 patients were excluded due to an invalid RTE examination, and 12 refused to undergo a liver biopsy. In total, 85 patients were included in the present study.

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table I. A total of 52 patients (61.2%) were male and the mean age of patients was 38.12±8.23 years. Mean liver stiffness as determined by FibroScan was 9.11±6.36 kPa, whereas mean LFI was 2.14±0.49. The RTE image parameters %AREA, SKEW and CONT were significantly associated with significant fibrosis; the %AREA, MEAN, SD, COMP, SKEW and CONT were significantly associated with cirhosis (Fig. 1). The mean Ishak fibrosis score was 3.58±1.60, and the prevalence of significant fibrosis (Ishak score ≥3) and cirrhosis (Ishak score ≥5) was 71.8 and 27.1%, respectively.

Table I.

Clinical, biological and histological characteristics of patients with chronic hepatitis B.

| Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Clinical data | |

| Male | 52 (61.2%) |

| Age (years) | 38.12±8.23 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.83±3.20 |

| Biological parameters | |

| AST (U/l) | 44.81±25.97 |

| ALT (U/l) | 64.26±27.18 |

| GGT (U/l) | 42.11±26.62 |

| Serum albumin (g/l) | 40.83±3.89 |

| Total bilirubin (µmol/l) | 14.80±1.05 |

| White blood cells (×1,000/mm3) | 5.88±1.59 |

| Platelet count (×1,000/mm3) | 184.64±61.89 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/l) | 5.43±1.41 |

| HBV-DNA (log10 IU/l) | 6.14±1.92 |

| HBeAg positive | 47 (55.3%) |

| Ultrasonographic parameters | |

| Portal vein diameter (mm) | 11.38±1.56 |

| Portal vein velocity (cm/s) | 21.79±6.59 |

| Hepatic artery diameter (mm) | 3.52±0.60 |

| Hepatic artery velocity (cm/s) | 77.70±22.82 |

| Hepatic artery resistive index | 0.74±0.07 |

| Spleen thickness (mm) | 32.89±5.14 |

| Spleen diameter (mm) | 92.79±9.68 |

| Splenic index | 34.73±9.48 |

| Splenoportal index | 1.79±0.83 |

| Splenic artery diameter (mm) | 4.34±0.83 |

| Splenic artery velocity (cm/s) | 73.68±21.45 |

| Splenic artery resistive index | 1.55±0.61 |

| Splenic vein diameter (mm) | 6.11±1.19 |

| Splenic vein velocity (cm/s) | 17.58±6.49 |

| Histological fibrosis stage (Ishak score) | |

| 0/1/2 | 24 (28.2%) |

| 3 | 14 (16.5%) |

| 4 | 24 (28.2%) |

| 5/6 | 23 (27.1%) |

| APRI | 27.43±27.42 |

| FIB-4 | 1.47±0.97 |

| Liver stiffness (FibroScan; kPa) | 9.11±6.36 |

| LFI | 2.14±0.49 |

Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation or number of patients (%). BMI, body mass index; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; GGT, γ-glutamyl transferase; APRI, aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index; FIB-4, fibrosis-4 index; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HBeAg, hepatitis B virus envelope antigen; LFI, liver fibrosis index.

Figure 1.

Association between fibrosis stage and the various parameters of the real-time tissue elastography images. %AREA, low-strain area percentage; COMP, low-strain area complexity; IDM, inverse difference moment; LFI, liver function index; MEAN, mean relative strain value; SD, standard deviation; SKEW, skewness; CONT, contrast. *P<0.05 vs. indicated Ishak fibrosis scores.

Comparison of variables according to significant fibrosis and cirrhosis

Patient characteristics stratified by the presence of significant liver fibrosis or cirrhosis are presented in Table II. The SI (P=0.005), SPI (P<0.001), FIB-4 (P=0.019), liver stiffness (P=0.039) and LFI (P<0.001) values in patients with significant fibrosis were significantly greater compared with the values in patients without significant fibrosis. In addition, significant differences between the GGT (P=0.002), serum albumin (P= 0.011), platelet count (P= 0.003), portal vein diameter (P=0.039), hepatic artery diameter (P=0.004), spleen thickness and diameter (P=0.0038 and 0.001, respectively), SI (P<0.001), SPI (P<0.001), splenic artery diameter (P=0.012), splenic vein velocity (P=0.031), FIB-4 (P=0.002), liver stiffness (P<0.001) and LFI (P<0.001) values were observed between patients with and without liver cirrhosis (Table II).

Table II.

Characteristics of patients with chronic hepatitis B stratified by the presence of significant fibrosis and cirrhosis.

| Variable | No significant fibrosis, F=0–2 (n=24) | Significant fibrosis, F=3–6 (n=61) | P-value | No cirrhosis, F=0–4 (n=62) | Cirrhosis, F=5–6 (n=23) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical data | ||||||

| Male | 11 (45.8%) | 41 (67.2) | 0.069 | 37 (59.7%) | 15 (65.2%) | 0.641 |

| Age (years) | 36.33±7.86 | 38.82±8.33 | 0.212 | 37.39±8.14 | 40.09±8.33 | 0.181 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.46±3.83 | 22.97±2.93 | 0.513 | 22.45±3.05 | 23.83±3.43 | 0.078 |

| Biological parameters | ||||||

| AST (U/l) | 38.08±26.36 | 47.46±51.64 | 0.401 | 44.44±50.97 | 45.83±29.41 | 0.902 |

| ALT (U/l) | 49.96±37.53 | 69.89±99.92 | 0.346 | 61.11±88.36 | 72.74±85.24 | 0.588 |

| GGT (U/l) | 28.50±29.11 | 47.46±63.72 | 0.166 | 30.89±41.39 | 72.35±58.61 | 0.002 |

| Serum albumin (g/l) | 41.87±3.87 | 40.42±3.85 | 0.123 | 41.48±3.71 | 39.08±3.92 | 0.011 |

| Total bilirubin (µmol/l) | 11.35±4.84 | 16.17±14.62 | 0.356 | 12.43±5.58 | 20.78±18.46 | 0.108 |

| WBC (×1,000/mm3) | 6.24±1.51 | 5.73±1.61 | 0.189 | 5.95±1.50 | 5.69±1.84 | 0.506 |

| Platelet count (×1,000/mm3) | 196.25±37.01 | 180.07±69.00 | 0.280 | 196.71±61.85 | 152.09±45.00 | 0.003 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/l) | 5.20±1.09 | 5.52±1.52 | 0.354 | 5.39±1.17 | 5.52±1.96 | 0.713 |

| HBV-DNA (log10 IU/l) | 6.34±2.19 | 6.07±1.81 | 0.560 | 6.16±1.99 | 6.11±1.74 | 0.917 |

| HBeAg positive | 13 (54.2%) | 34 (55.7%) | 0.102 | 36 (58.1%) | 12 (52.2%) | 0.627 |

| Ultrasonographic parameters | ||||||

| Portal vein diameter (mm) | 10.87±1.70 | 11.58±1.47 | 0.061 | 11.16±1.65 | 11.95±1.16 | 0.039 |

| Portal vein velocity (cm/s) | 22.80±5.36 | 21.40±7.02 | 0.380 | 22.32±6.29 | 20.37±7.29 | 0.227 |

| Hepatic artery diameter (mm) | 3.24±0.45 | 3.42±0.62 | 0.008 | 3.35±0.52 | 3.65±0.61 | 0.004 |

| Hepatic artery velocity (cm/s) | 67.81±25.41 | 73.22±67.81 | 0.328 | 70.76±24.11 | 74.21±19.17 | 0.539 |

| Hepatic artery resistive index | 0.73±0.052 | 0.75±0.082 | 0.519 | 0.75±0.053 | 0.72±0.11 | 0.125 |

| Spleen thickness (mm) | 31.27±4.80 | 33.52±6.17 | 0.069 | 32.19±4.96 | 34.57±5.25 | 0.038 |

| Spleen diameter (mm) | 89.50±6.80 | 93.98±10.38 | 0.054 | 90.57±7.68 | 98.50±12.09 | 0.001 |

| Splenic index | 30.15±7.03 | 36.53±9.76 | 0.005 | 31.51±7.25 | 43.39±9.49 | <0.001 |

| Splenoportal index | 1.21±0.27 | 2.02±0.87 | <0.001 | 1.51±0.66 | 2.54±0.80 | <0.001 |

| Splenic artery diameter (mm) | 4.10±0.71 | 4.43±0.86 | 0.092 | 4.20±0.76 | 4.71±0.92 | 0.012 |

| Splenic artery velocity (cm/s) | 73.48±19.37 | 73.75±22.37 | 0.958 | 73.36±21.31 | 74.55±22.30 | 0.822 |

| Splenic artery resistive index | 0.60±0.070 | 1.93±1.16 | 0.527 | 1.89±0.083 | 0.64±0.075 | 0.555 |

| Splenic vein diameter (mm) | 5.97±1.08 | 6.17±1.23 | 0.496 | 5.89±1.08 | 6.71±1.29 | 0.004 |

| Splenic vein velocity (cm/s) | 19.28±8.47 | 16.91±5.46 | 0.130 | 18.50±6.76 | 15.11±5.00 | 0.031 |

| APRI | 21.91±21.71 | 29.60±7.17 | 0.247 | 24.85±27.65 | 34.37±26.11 | 0.156 |

| FIB-4 | 1.08±0.67 | 1.62±1.03 | 0.019 | 1.27±0.85 | 2.00±1.09 | 0.002 |

| Liver stiffness (FibroScan, kPa) | 6.84±2.46 | 10.00±7.17 | 0.039 | 7.20±2.72 | 14.25±9.80 | <0.001 |

| LFI | 1.83±0.33 | 2.26±0.49 | <0.001 | 2.00±0.42 | 2.52±0.46 | <0.001 |

Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation or number of patients (%). ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; APRI, aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index; BMI, body mass index; FIB-4, fibrosis-4 index; GGT, γ-glutamyl transferase; HBV, hepatitis B virus; LFI, liver fibrosis index; WBC, white blood cell; HbeAg, hepatitis B virus envelope antigen.

Predictors of significant fibrosis and cirrhosis

Variables associated with the presence of significant fibrosis (Table III) or cirrhosis (Table IV) were assessed by univariate and multivariate analyses. Univariate predictors were entered into a stepwise logistic regression model. Out of all variables, SPI (P= 0.002) and LFI (P= 0.023) were confirmed as independent predictors of significant fibrosis (Table III), whereas GGT (P=0.049), SPI (P=0.002) and LFI (P=0.001) were determined to be independent predictors of cirrhosis (Table IV), based on the results of multivariate analysis.

Table III.

Analysis of variables associated with the presence of significant fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B.

| Variable | Univariate analysis

|

Multivariate analysis

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P-value | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Clinical data | ||||||

| Male (%) | 2.423 | 0.923–6.357 | 0.072 | |||

| Age (years) | 1.038 | 0.979–1.101 | 0.211 | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1.054 | 0.903–1.230 | 0.508 | |||

| Biological parameters | ||||||

| AST (U/l) | 1.008 | 0.989–1.026 | 0.418 | |||

| ALT (U/l) | 1.004 | 0.995–1.104 | 0.369 | |||

| GGT (U/l) | 1.011 | 0.995–1.027 | 0.191 | |||

| Serum albumin (g/l) | 0.901 | 0.789–1.029 | 0.126 | |||

| Total bilirubin (µmol/l) | 1.061 | 0.962–1.169 | 0.236 | |||

| WBC (×1,000/mm3) | 0.821 | 0.611–1.103 | 0.190 | |||

| Platelet count (×1,000/mm3) | 0.996 | 0.988–1.004 | 0.295 | |||

| Fasting glucose (mmol/l) | 1.213 | 0.807–1.823 | 0.354 | |||

| HBV-DNA (log10 IU/l) | 0.927 | 0.721–1.192 | 0.555 | |||

| HBeAg positive (%) | 1.066 | 0.413–2.751 | 0.896 | |||

| Ultrasonographic parameters | ||||||

| Portal vein diameter (mm) | 1.352 | 0.981–1.863 | 0.066 | |||

| Portal vein velocity (cm/s) | 0.968 | 0.901–1.040 | 0.376 | |||

| Hepatic artery diameter (mm) | 3.417 | 1.326–8.811 | 0.011 | 1.824 | 0.532–6.250 | 0.339 |

| Hepatic artery velocity (cm/s) | 1.011 | 0.989–1.033 | 0.325 | |||

| Hepatic artery resistive index | 7.335 | 0.017–3162.39 | 0.520 | |||

| Spleen thickness (mm) | 1.102 | 0.991–1.226 | 0.074 | |||

| Spleen diameter (mm) | 1.061 | 0.998–1.128 | 0.057 | |||

| Splenic index | 1.098 | 1.025–1.176 | 0.007 | 0.965 | 0.875–1.064 | 0.469 |

| Splenoportal index | 20.532 | 4.116–102.418 | <0.001 | 13.965 | 2.690–72.441 | 0.002 |

| Splenic artery diameter (mm) | 1.723 | 0.909–3.266 | 0.096 | |||

| Splenic artery velocity (cm/s) | 1.001 | 0.979–1.023 | 0.957 | |||

| Splenic artery resistive index | 57.857 | 0.079–2439. 6 | 0.288 | |||

| Splenic vein diameter (mm) | 1.153 | 0.769–1.727 | 0.491 | |||

| Splenic vein velocity (cm/s) | 0.947 | 0.881–1.018 | 0.141 | |||

| APRI | 1.105 | 0.989–1.403 | 0.259 | |||

| FIB-4 | 2.267 | 1.091–4.711 | 0.028 | |||

| Liver stiffness (FibroScan kPa) | 1.230 | 1.041–1.454 | 0.015 | |||

| LFI | 11.345 | 2.787–46.179 | 0.001 | 6.283 | 1.291–30.575 | 0.023 |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; APRI, aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index; BMI, body mass index; FIB-4, fibrosis-4 index; GGT, γ-glutamyl transferase; HBV, hepatitis B virus; LFI, liver fibrosis index; WBC, white blood cell; HbeAg, hepatitis B virus envelope antigen.

Table IV.

Analysis of variables associated with the presence of cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B.

| Variable | Univariate analysis

|

Multivariate analysis

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P-value | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Clinical data | ||||||

| Male (%) | 1.267 | 0.468–3.433 | 0.642 | |||

| Age (years) | 1.042 | 0.981–1.108 | 0.181 | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1.143 | 0.981–1.331 | 0.086 | |||

| Biological parameters | ||||||

| AST (U/l) | 1.001 | 0.991–1.011 | 0.901 | |||

| ALT (U/l) | 1.001 | 0.996–1.006 | 0.590 | |||

| GGT (U/l) | 1.014 | 1.002–1.026 | 0.018 | 1.012 | 1.000–1.024 | 0.049 |

| Serum albumin (g/l) | 0.849 | 0.744–0.969 | 0.015 | 1.306 | 0.986–1.729 | 0.063 |

| Total bilirubin (µmol/l) | 1.024 | 0.975–1.076 | 0.341 | |||

| WBC (×1,000/mm3) | 0.898 | 0.656–1.229 | 0.502 | |||

| Platelet count (×1,000/mm3) | 0.982 | 0.970–0.993 | 0.002 | 0.989 | 0.966–1.012 | 0.343 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/l) | 1.064 | 0.767–1.475 | 0.710 | |||

| HBV-DNA (log10 IU/l) | 0.987 | 0.768–1.268 | 0.916 | |||

| HBeAg positive (%) | 0.842 | 0.322–2.198 | 0.725 | |||

| Ultrasonographic parameters | ||||||

| Portal vein diameter (mm) | 1.418 | 1.010–1.992 | 0.044 | 0.835 | 0.447–1.559 | 0.571 |

| Portal vein velocity (cm/s) | 0.954 | 0.883–1.030 | 0.226 | |||

| Hepatic artery diameter (mm) | 2.133 | 1.539–4.589 | 0.002 | 4.467 | 0.621–32.149 | 0.137 |

| Hepatic artery velocity (cm/s) | 1.007 | 0.986–1.028 | 0.543 | |||

| Hepatic artery resistive index | 0.008 | 0.001–6.408 | 0.158 | |||

| Spleen thickness (mm) | 1.102 | 1.002–1.213 | 0.045 | 0.977 | 0.720–1.328 | 0.884 |

| Spleen diameter (mm) | 1.101 | 1.032–1.176 | 0.004 | 1.155 | 0.969–1.377 | 0.107 |

| Splenic index | 1.188 | 1.094–1.290 | <0.001 | 1.100 | 0.937–1.292 | 0.245 |

| Splenoportal index | 6.513 | 2.583–16.422 | <0.001 | 5.676 | 1.939–16.618 | 0.002 |

| Splenic artery diameter (mm) | 2.103 | 1.141–3.874 | 0.017 | 0.483 | 0.068–3.437 | 0.468 |

| Splenic artery velocity (cm/s) | 1.003 | 0.981–1.025 | 0.820 | |||

| Splenic artery resistive index | 0.950 | 0.699–1.291 | 0.744 | |||

| Splenic vein diameter (mm) | 1.890 | 1.199–2.980 | 0.006 | 2.729 | 0.701–10.622 | 0.148 |

| Splenic vein velocity (cm/s) | 0.896 | 0.809–0.992 | 0.034 | 1.039 | 0.974–1.323 | 0.103 |

| APRI | 1.011 | 0.995–1.029 | 0.186 | |||

| FIB-4 | 2.082 | 1.254–3.456 | 0.005 | |||

| Liver stiffness (FibroScan kPa) | 1.492 | 1.247–1.785 | <0.001 | |||

| LFI | 13.944 | 3.603–53.960 | <0.001 | 14.102 | 2.873–69.221 | 0.001 |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; APRI, aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index; BMI, body mass index; FIB-4, fibrosis-4 index; GGT, γ-glutamyl transferase; HBV, hepatitis B virus; LFI, liver-fibrosis index; WBC, white blood cell; HbeAg, hepatitis B virus envelope antigen.

Development of a novel model for the prediction of significant fibrosis and cirrhosis and determination of diagnostic accuracy

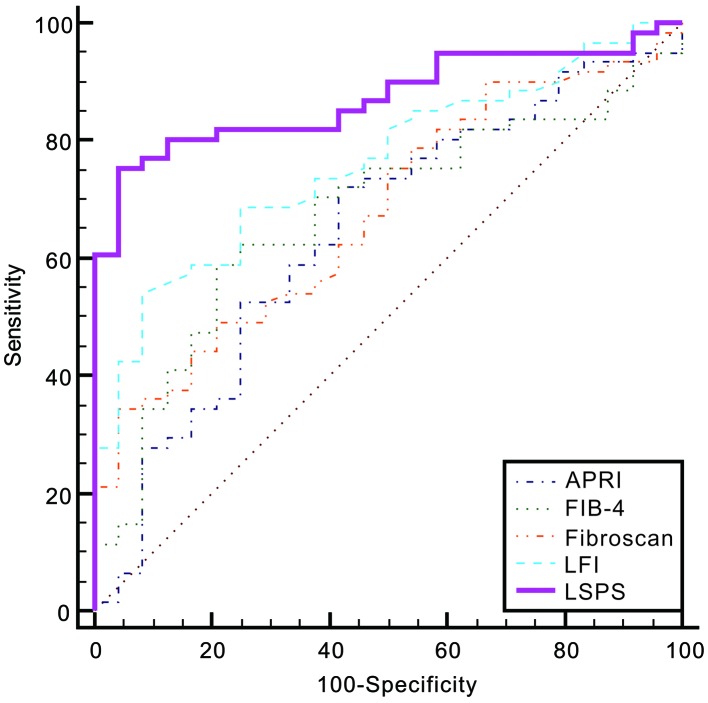

Considering the aforementioned multivariate analysis results, the multiple fractional equations for the prediction of significant fibrosis and cirrhosis that included LFI were respectively derived. The novel model for the prediction of significant fibrosis, termed the LFI-SPI score (LSPS), was derived using the following formula: LSPS = 1.838LFI + 2.6 36SPI − 6.728. A regression formula for predicting cirrhosis, termed the LFI-SPI-GGT score (LSPGS), was derived as follows: LSPGS = 2.646LFI + 1.736SPI + 0.011GGT − 10.967. The AUROC of LSPS was 0.87 [95% confidence interval (95% CI), 0.78–0.94], demonstrating the superior diagnostic accuracy of this novel formula for the prediction of significant fibrosis when compared with the LFI, APRI, FIB-4 and FibroScan models (AUROC=0.76, 0.64, 0.67 and 0.68, respectively; P=0.0109, 0.0031, 0.0044 and 0.0021, respectively; Fig. 2 and Table V). With a cut-off value of 0.7423, LSPS had an excellent sensitivity of 75.41%, a specificity of 95.83%, positive LR (PLR) of 18.10, negative LR (NLR) of 0.26, PPV of 97.9% and NPV of 60.5% (for 95% CI values, refer to Table V).

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for predicting the presence of significant fibrosis using the LSPS formula. APRI, aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index; FIB-4, fibrosis-4 index; LFI, liver fibrosis index; LSPS, LFI-SPI score; SPI, splenoportal index.

Table V.

Diagnostic values of models for predicting significant fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B.

| Models | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PLR | NLR | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | AUROC | Youden index | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LFI | 54.10 (40.8–66.9) | 91.7 (73.0–99.0) | 6.49 (1.7–25.0) | 0.50 (0.4–0.7) | 94.3 (80.8–99.3) | 44.0 (30.0–58.7) | 0.76 (0.66–0.85) | 0.4577 | 0.0109 |

| APRI | 37.7 (25.6–51.0) | 75.0 (53.3–90.2) | 1.51 (0.7–3.2) | 0.83 (0.6–1.1) | 79.3 (60.3–92.0) | 32.1 (20.3–46.0) | 0.64 (0.53–0.74) | 0.3046 | 0.0031 |

| FIB-4 | 59.02 (45.7–71.4) | 79.17 (57.8–92.9) | 2.83 (1.3–6.4) | 0.52 (0.4–0.7) | 87.8 (73.8–95.9) | 43.2 (28.3–59.0) | 0.67 (0.56–0.77) | 0.382 | 0.0044 |

| FibroScan | 34.43 (22.7–47.7) | 95.83 (78.9–99.9) | 8.26 (1.2–58.1) | 0.68 (0.6–0.8) | 95.5 (77.2–99.9) | 36.5 (24.7–49.6) | 0.68 (0.57–0.77) | 0.3026 | 0.0021 |

| LSPS | 75.41 (62.7–85.5) | 95.83 (78.9–99.9) | 18.10 (2.6–124.0) | 0.26 (0.2–0.4) | 97.9 (88.7–99.9) | 60.5 (43.4–76.0) | 0.87 (0.78–0.94) | 0.7124 | Reference |

Values are expressed along with the 95% confidence intervals (in parentheses). APRI, aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index; AUROC, area under receiver operating characteristic curves; FIB-4, fibrosis-4 index; LFI, liver fibrosis index; PLR, positive likelihood ratio; NLR, negative likelihood ratio; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; LSPS, liver fibrosis index-splenoportal index.

The performance of LSPGS in predicting cirrhosis was also high, with an AUROC of 0.93. Apart from liver stiffness (as determined by FibroScan; AUROC=0.85; P=0.134), the LFI, APRI and FIB-4 models (AUROC, 0.81, 0.67 and 0.71, respectively; P=0.0113, <0.0001 and 0.0005, respectively) showed significantly lower AUROC values compared with that of the LSPGS (Fig. 3 and Table VI). With a cut-off value of 0.1803, LSPGS had an excellent sensitivity of 95.65%, a specificity of 80.65%, PLR of 4.94, NLR of 0.054, PPV of 64.7% and NPV of 98.0% (for 95% CI values, refer to Table VI).

Figure 3.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for predicting the presence of cirrhosis using the LSPGS formula. APRI, aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index; FIB-4, fibrosis-4 index; LFI, liver function index; LSPGS, LFI-SPI-GGT score; SPI, splenoportal index; GGT, γ-glutamyl transferase.

Table VI.

Diagnostic values of models for predicting cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B.

| Models | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PLR | NLR | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | AUROC | Youden index | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LFI | 82.61 (61.2–95.0) | 75.81 (63.3–85.8) | 3.41 (2.1–5.5) | 0.23 (0.09–0.6) | 55.9 (37.9–72.8) | 92.2 (81.1–97.8) | 0.81 (0.71–0.89) | 0.5842 | 0.0113 |

| APRI | 100.0 (85.2–100.0) | 27.42 (16.9–40.2) | 1.38 (1.2–1.6) | 0 | 33.8 (22.8–46.3) | 100.0 (80.5–100.0) | 0.67 (0.56–0.77) | 0.2742 | <0.0001 |

| FIB-4 | 65.22 (42.7–83.6) | 87.10 (76.1–94.3) | 5.05 (2.5–10.3) | 0.40 (0.2–0.7) | 65.2 (42.7–83.6) | 87.1 (76.1–94.3) | 0.71 (0.60–0.80) | 0.5231 | 0.0005 |

| FibroScan | 69.57 (47.1–86.8) | 93.55 (84.3–98.2) | 10.78 (4.0–28.9) | 0.33 (0.2–0.6) | 80.0 (56.3–94.3) | 89.2 (79.1–95.6) | 0.85 (0.76–0.92) | 0.6311 | 0.1342 |

| LSPGS | 95.65 (78.1–99.9) | 80.65 (68.6–89.6) | 4.94 (3.0–8.3) | 0.054 (0.008–0.4) | 64.7 (46.5–80.3) | 98.0 (89.6–100.0) | 0.93 (0.85–0.97) | 0.7630 | Reference |

Values are expressed along with the 95% confidence intervals (shown in parentheses). APRI, aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index; AUROC, area under receiver operating characteristic curves; FIB-4, fibrosis-4 index; LFI, liver fibrosis index; PLR, positive likelihood ratio; NLR, negative likelihood ratio; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; LSPS, liver fibrosis index-splenoportal index.

Discussion

The use of liver biopsy to diagnose fibrosis and cirrhosis is limited by the occurrence of sampling errors, as well as intra and inter-observer variability (27,28). Therefore, a reliable non-invasive diagnostic model with ~90% accuracy is required, according to the AUROC value. Studies have shown that the performance of various serum test formulas is not satisfactory (29,30). Liver stiffness measured by US methods has demonstrated the most accurate diagnostic performance for advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis among all non-invasive assessments of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis (31). However, the diagnostic performance of these methods is particularly affected by hepatic inflammation, ascites and/or steatosis (32). In the present study, the RTE-based quantitative analysis method LFI was calculated using multiple regression analysis of nine image features, the majority of which were significantly associated with the hepatic fibrosis stage. However, LFI alone was observed to have a good diagnostic performance for liver fibrosis, particularly in patients with CHB. The diagnostic performance of LFI to confirm advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis may be improved further using an algorithm that combines LFI with serum markers and US parameters.

The aim of the present study was to develop a novel and accurate model using routinely available laboratory tests and US parameters of the liver and spleen, which can predict significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in a consecutive series of treatment-naive patients with CHB. SPI and LFI were found to be independent predictors of significant fibrosis, whereas GGT, SPI and LFI were independent predictors of cirrhosis. Numerous previous studies have demonstrated that platelet count, AST level, and AST/ALT ratio are important predictors of significant fibrosis or cirrhosis (33,34). However, in the present study, only the GGT laboratory parameter was independently associated with cirrhosis, which is in agreement with the results of previous studies (35,36). Furthermore, several assay panels are currently available for the assessment of fibrosis, which use a combination of markers, including GGT. GGT is associated with hepatocyte growth factor, which is a pleiotropic cytokine produced by hepatic stellate cells (37). Therefore, early cholestasis or an increase in epidermal growth factor expression may offer an explanation for the observed increase in GGT with increasing fibrosis severity.

A total of 14 US parameters, which are considered to be associated with the progression of chronic liver diseases, were measured in the present study. The SPI was the only ultrasound index to enter the discriminant function. Enlargement of the spleen may be caused by high portal vein pressure, and the degree of fibrosis is the most important factor affecting portal vein pressure (38). SPI incorporates spleen size and PVV characteristics, which may therefore provide a more reliable indication of chronic liver disease progression. There are two advantages to the use of SPI for predicting the presence of significant fibrosis and cirrhosis: Firstly, SPI can be measured concomitantly during routine biannual US screening for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with CHB and therefore, it does not incur additional costs; secondly, the techniques used to measure SI and mean PVV can be performed without difficulty.

By combining LFI and SPI, a novel formula for predicting significant fibrosis, defined as LSPS, was derived from the analysis conducted in the present study. LSPS had an excellent diagnostic accuracy in staging significant fibrosis, with an AUROC of 0.87, which was superior to noninvasive tests used in previous studies (39,40). By contrast, the LSM scores of patients were relatively low, which may have been due to the inclusion of patients with greatly elevated serum ALT or AST levels (abnormality rate, 38.8%) or other factors such as BMI (obesity rate, 25.9%). Furthermore, for predicting the stage of liver cirrhosis, the novel LSPGS formula was derived from the analysis by integrating LFI, SPI and GGT values. The diagnostic performance of LSPGS was similar to that of FibroScan, since these two models had excellent diagnostic accuracies to detect cirrhosis (AUROC=0.93 and 0.85, respectively) and were superior to other noninvasive tests. Notably, the predictive models consisted of objective and readily available laboratory variables and US parameters. SPI and GGT tests are performed routinely in clinical practice to diagnose patients with CHB.

APRI and FIB-4 can be readily calculated from simple blood tests, which are performed routinely in patients admitted for a liver biopsy. However, despite the fact that APRI and FIB-4 are useful for detecting significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in HBV-infected patients, these tests are not accurate for excluding the presence of fibrosis and cirrhosis (16,41). Thus, the reliability of APRI and FIB-4 values for the day-to-day management of patients in clinical hepatology practice is questionable.

The present study was limited by the fact that it was a single-center study, and thus independent external validation in other cohorts is necessary to validate the results. The distribution of the fibrosis stages of the enrolled subjects may not have been an accurate representation of the disease spectrum observed routinely during daily practice or in other medical centers, which may affect the interpretation of the derived indexes. In addition, the total number of patients with CHB included in the present study was small. Patients recruited to The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University were more likely to have presented with advanced disease. Therefore, AUROC values for the diagnosis of severe fibrosis and cirrhosis may be overestimated in the present study. In addition, patient numbers were not distributed equally between Ishak scores 0 and 6 fibrosis stages. Therefore, the possibility that this distribution improved the predictive value of models cannot be excluded. However, the cohort was not sufficiently large to conduct a stage-by-stage comparison. Furthermore, this was a cross-sectional study, and therefore the ability of LSPS and LSPGS to predict the subsequent development or progression of fibrosis requires further investigation in a longitudinal cohort.

In conclusion, two novel formulas (LSPS and LSPGS) for predicting significant liver fibrosis and cirrhosis were developed over the course of the current prospective study. The LSPS and LSPGS formulas were found to provide excellent diagnostic accuracies in predicting significant fibrosis and cirrhosis. These results led to a reduction in the number of unnecessary liver biopsies by 60.5 and 98.0% for significant fibrosis and cirrhosis, respectively.

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by the Scientific Research Foundation of Wenzhou (grant no. Y20100042).

References

- 1.Yu R, Fan R, Hou J. Chronic hepatitis B virus infection: Epidemiology, prevention, and treatment in China. Front Med. 2014;8:135–144. doi: 10.1007/s11684-014-0331-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liaw YF. Reversal of cirrhosis: An achievable goal of hepatitis B antiviral therapy. J Hepatol. 2013;59:880–881. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guido M, Mangia A, Faa G, Gruppo Italiano Patologi Apparato Digerente (GIPAD) Società Italiana di Anatomia Patologica e Citopatologia Diagnostica/International Academy of Pathology Italian division (SIAPEC/IAP) Chronic viral hepatitis: The histology report. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43(Suppl 4):S331–S343. doi: 10.1016/S1590-8658(11)60589-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castera L. Noninvasive methods to assess liver disease in patients with hepatitis B or C. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1293–1302.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaia S, Campion D, Evangelista A, Spandre M, Cosso L, Brunello F, Ciccone G, Bugianesi E, Rizzetto M. Non-invasive score system for fibrosis in chronic hepatitis: Proposal for a model based on biochemical, FibroScan and ultrasound data. Liver Int. 2015;35:2027–2035. doi: 10.1111/liv.12761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu X, Xu X, Zhang Q, Zhang H, Liu J, Qian L. Indirect prediction of liver fibrosis by quantitative measurement of spleen stiffness using the FibroScan system. J Ultrasound Med. 2014;33:73–81. doi: 10.7863/ultra.33.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim SU, Lee JH, Kim DY, Ahn SH, Jung KS, Choi EH, Park YN, Han KH, Chon CY, Park JY. Prediction of liver-related events using fibroscan in chronic hepatitis B patients showing advanced liver fibrosis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36676. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bamber J, Cosgrove D, Dietrich CF, Fromageau J, Bojunga J, Calliada F, Cantisani V, Correas JM, D'Onofrio M, Drakonaki EE, et al. EFSUMB guidelines and recommendations on the clinical use of ultrasound elastography. Part 1: Basic principles and technology. Ultraschall Med. 2013;34:169–184. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1335205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cosgrove D, Piscaglia F, Bamber J, Bojunga J, Correas JM, Gilja OH, Klauser AS, Sporea I, Calliada F, Cantisani V, et al. EFSUMB guidelines and recommendations on the clinical use of ultrasound elastography. Part 2: Clinical applications. Ultraschall Med. 2013;34:238–253. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1335375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu Q, Zhu SY, Kang LK, Wang XY, Lun HM, Xu CM. Non-invasive assessment of liver fibrosis using real-time tissue elastography in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Clin Radiol. 2014;69:194–199. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobayashi K, Nakao H, Nishiyama T, Lin Y, Kikuchi S, Kobayashi Y, Yamamoto T, Ishii N, Ohashi T, Satoh K, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of real-time tissue elastography for the staging of liver fibrosis: A meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. 2015;25:230–238. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3364-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yada N, Kudo M, Morikawa H, Fujimoto K, Kato M, Kawada N. Assessment of liver fibrosis with real-time tissue elastography in chronic viral hepatitis. Oncology. 2013;84(Suppl 1):S13–S20. doi: 10.1159/000345884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujimoto K, Kato M, Kudo M, Yada N, Shiina T, Ueshima K, Yamada Y, Ishida T, Azuma M, Yamasaki M, et al. Novel image analysis method using ultrasound elastography for noninvasive evaluation of hepatic fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Oncology. 2013;84(Suppl 1):S3–S12. doi: 10.1159/000345883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shiraishi A, Hiraoka A, Aibiki T, Okudaira T, Kawamura T, Imai Y, Tatsukawa H, Yamago H, Nakahara H, Shimizu Y, et al. Real-time tissue elastography: Non-invasive evaluation of liver fibrosis in chronic liver disease due to HCV. Hepatogastroenterology. 2014;61:2084–2090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yada N, Kudo M, Kawada N, Sato S, Osaki Y, Ishikawa A, Miyoshi H, Sakamoto M, Kage M, Nakashima O, Tonomura A. Noninvasive diagnosis of liver fibrosis: Utility of data mining of both ultrasound elastography and serological findings to construct a decision tree. Oncology. 2014;87(Suppl 1):S63–S72. doi: 10.1159/000368147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiao G, Yang J, Yan L. Comparison of diagnostic accuracy of aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index and fibrosis-4 index for detecting liver fibrosis in adult patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2015;61:292–302. doi: 10.1002/hep.27382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu T, Ren J, Cong SZ, Meng FK, Yang H, Luo Y, Lin HJ, Sun Y, Wang XY, Pei SF, et al. Accuracy of real-time tissue elastography for the evaluation of hepatic fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B: A prospective multicenter study. Dig Dis. 2014;32:791–799. doi: 10.1159/000368024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathurin P, Bataller R. Trends in the management and burden of alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2015;62(1 Suppl):S38–S46. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liaw YF, Leung N, Kao JH, Piratvisuth T, Gane E, Han KH, Guan R, Lau GK, Locarnini S, Chronic Hepatitis B Guideline Working Party of the Asian-Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: A 2008 update. Hepatol Int. 2008;2:263–283. doi: 10.1007/s12072-008-9080-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang ZL, Chen XP, Zhao QY, Zheng YB, Peng L, Gao ZL, Zhao ZX. An albumin, collagen IV, and longitudinal diameter of spleen scoring system superior to APRI for assessing liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B patients. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;31:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu CH, Hsu SJ, Liang CC, Tsai FC, Lin JW, Liu CJ, Yang PM, Lai MY, Chen PJ, Chen JH, et al. Esophageal varices: Noninvasive diagnosis with duplex Doppler US in patients with compensated cirrhosis. Radiology. 2008;248:132–139. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2481071257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott DR, Levy MT. Liver transient elastography (Fibroscan): A place in the management algorithms of chronic viral hepatitis. Antivir Ther. 2010;15:1–11. doi: 10.3851/IMP1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tatsumi C, Kudo M, Ueshima K, Kitai S, Ishikawa E, Yada N, Hagiwara S, Inoue T, Minami Y, Chung H, et al. Non-invasive evaluation of hepatic fibrosis for type C chronic hepatitis. Intervirology. 2010;53:76–81. doi: 10.1159/000252789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu S, Wang Y, Tai DC, Wang S, Cheng CL, Peng Q, Yan J, Chen Y, Sun J, Liang X, et al. qFibrosis: A fully-quantitative innovative method incorporating histological features to facilitate accurate fibrosis scoring in animal model and chronic hepatitis B patients. J Hepatol. 2014;61:260–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, Callea F, De Groote J, Gudat F, Denk H, Desmet V, Korb G, MacSween RN, et al. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1995;22:696–699. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80226-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parker CB, DeLong ER. ROC methodology within a monitoring framework. Stat Med. 2003;22:3473–3488. doi: 10.1002/sim.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bedossa P, Dargère D, Paradis V. Sampling variability of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:1449–1457. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.09022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldin RD, Goldin JG, Burt AD, Dhillon PA, Hubscher S, Wyatt J, Patel N. Intra-observer and inter-observer variation in the histopathological assessment of chronic viral hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1996;25:649–654. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(96)80234-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu XY, Kong H, Song RX, Zhai YH, Wu XF, Ai WS, Liu HB. The effectiveness of noninvasive biomarkers to predict hepatitis B-related significant fibrosis and cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100182. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ozel BD, Poyrazoğlu OK, Karaman A, Karaman H, Altinkaya E, Sevinç E, Zararsiz G. The PAPAS index: A novel index for the prediction of hepatitis C-related fibrosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;27:895–900. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chon YE, Choi EH, Song KJ, Park JY, Kim do Y, Han KH, Chon CY, Ahn SH, Kim SU. Performance of transient elastography for the staging of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44930. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim SU, Seo YS, Cheong JY, Kim MY, Kim JK, Um SH, Cho SW, Paik SK, Lee KS, Han KH, Ahn SH. Factors that affect the diagnostic accuracy of liver fibrosis measurement by Fibroscan in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:498–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheth SG, Flamm SL, Gordon FD, Chopra S. AST/ALT ratio predicts cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:44–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.044_c.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murali AR, Attar BM, Katz A, Kotwal V, Clarke PM. Utility of platelet count for predicting cirrhosis in alcoholic liver disease: Model for identifying cirrhosis in a US population. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:1112–1117. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3238-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Imbert-Bismut F, Ratziu V, Pieroni L, Charlotte F, Benhamou Y, Poynard T, MULTIVIRC Group Biochemical markers of liver fibrosis in patients with hepatitis C virus infection: A prospective study. Lancet. 2001;357:1069–1075. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04258-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lens S, Torres F, Puigvehi M, Mariño Z, Londoño MC, Martinez SM, García-Juárez I, García-Criado Á, Gilabert R, Bru C, et al. Predicting the development of liver cirrhosis by simple modelling in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:364–374. doi: 10.1111/apt.13472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marin-Serrano E, Rodriguez-Ramos C, Diaz-Garcia F, Martin-Herrera L, Fernández-Gutiérrez-Del-Alamo C, Girón-González JA. Hepatocyte growth factor and chronic hepatitis C. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2010;102:365–371. doi: 10.4321/S1130-01082010000600004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bolognesi M, Merkel C, Sacerdoti D, Nava V, Gatta A. Role of spleen enlargement in cirrhosis with portal hypertension. Dig Liver Dis. 2002;34:144–150. doi: 10.1016/S1590-8658(02)80246-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zeng X, Xu C, He D, Li M, Zhang H, Wu Q, Xiang D, Wang Y. Performance of several simple, noninvasive models for assessing significant liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Croat Med J. 2015;56:272–279. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2015.56.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ucar F, Sezer S, Ginis Z, Ozturk G, Albayrak A, Basar O, Ekiz F, Coban S, Yuksel O, Armutcu F, Akbal E. APRI, the FIB-4 score, and Forn's index have noninvasive diagnostic value for liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:1076–1081. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32835fd699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Y, Chen Y, Zhao Y. The diagnostic value of the FIB-4 index for staging hepatitis B-related fibrosis: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105728. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]